1. Introduction

Tebuthiuron is a widely used herbicide in sugarcane cultivation,[

1] and has raised significant environmental concerns due to its high water-solubility (2.5 g L

-1 at 25°C),[

2] long-lasting soil persistence (log KOW = 1.8),[

2] and potential contamination of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.[

3] As the detrimental impacts of tebuthiuron on the environment become increasingly evident, urgent attention is directed towards innovative and sustainable remediation strategies to address its persistent presence. Among these, phytoremediation has emerged as a highly promising approach, harnessing the natural power of photosynthetic plant systems to detoxify environments contaminated by pesticides.[

4] This innovative technique not only cleanses the affected areas but also enhances their suitability for sustainable food production.[

4]

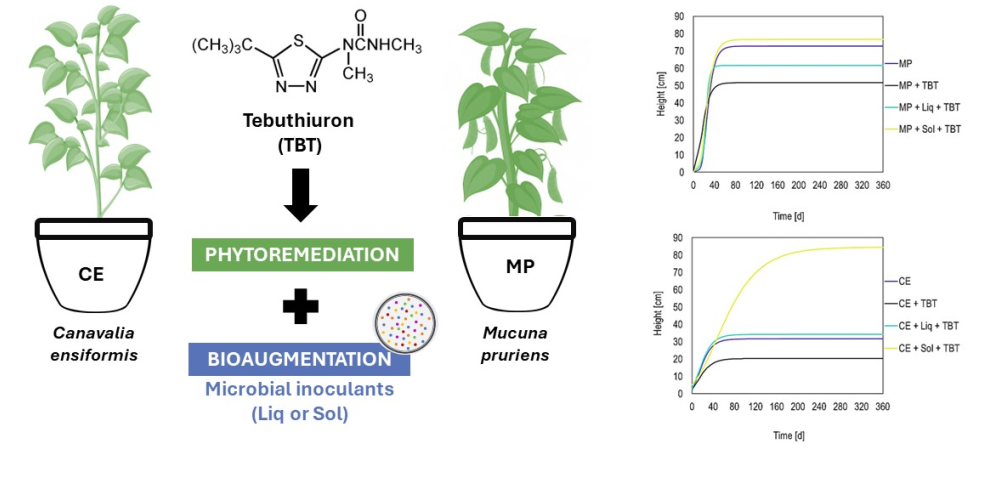

In the pursuit of effective tebuthiuron remediation, our study investigates the tolerance and phytoremediation potential of remarkable legumes, namely velvet bean (

Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC. var.

pruriens) and jack bean (

Canavalia ensiformis L.) in combination with microbial inoculants in soil. These species are leguminous plants with the ability to degrade tebuthiuron and biologically capture atmospheric nitrogen, subsequently making it available in the soil. This process enhances the soil's physical, chemical, and biological characteristics. According to diverse studies, these species have demonstrated remarkable resilience to tebuthiuron making them promising candidates for tackling tebuthiuron-contaminated environments. [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]

Phytoremediation, though a promising technology, is not without challenges.[

11] The success of this approach is contingent on various factors such as soil characteristics, climate, and the presence of co-contaminants.[

12] By gaining a comprehensive understanding of the complex interactions between the selected plant species and tebuthiuron, we seek to optimize the application of phytoremediation and propel its effectiveness in addressing herbicide contamination. Additionally, to enhance the efficiency of tebuthiuron remediation, we incorporate bioaugmentation as a pivotal strategy.[

13] Through the introduction of selected microbial strains with remarkable pesticide degradation capabilities, resilience, and adaptability to environmental conditions,[

14] we forge a symbiotic alliance that expedites the pesticide degradation in soil. The integration of phytoremediation and bioaugmentation offers a powerful synergy [

12] with significant improvements in tebuthiuron degradation efficiency and global remediation outcomes. Our approach places a strong emphasis on safety and efficacy by conducting comprehensive evaluations of tebuthiuron's environmental toxicity levels during the remediation process. Tests are designed to provide a realistic prediction of the behavior of substances in the environment. To achieve this, we utilize some bioindicator plants and ecotoxicology bioassays, such as

Crotalaria Juncea and

Lactuca sativa, to confirm the presence of tebuthiuron in the soil.[

3,

8,

10,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]

Therefore, this research aims to contribute to the current knowledge by investigating the tolerance and phytoremediation potential of M. pruriens and C. ensiformis, in conjunction with microbial inoculants, for tebuthiuron-contaminated agricultural soil remediation. The findings will advance our understanding of the viability and effectiveness of these techniques in addressing tebuthiuron contamination, addressing ecological and environmental concerns associated with this persistent herbicide. Innovative and sustainable approaches are crucial for the successful remediation of tebuthiuron-contaminated agricultural soil.

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Soil, Tebuthiuron, and Microbial Inoculant

The soil employed in this study was a Dystrophic Red Yellow Oxisol, a prevalent soil type in tropical regions. Dystrophic Oxisols are characterized by low natural fertility, acidic pH, and high iron and aluminum oxide content, affecting nutrient and contaminant retention. [

20] To represent real-world scenarios in pesticide-contaminated agricultural settings, it was crucial to select a soil type with these characteristics. Soil samples were collected before and after the experiment to determine their chemical composition (

Table 1). The samples were dried, sieved through 2.0 mm, and stored in sealed plastic containers for further analysis.

The tebuthiuron (TBT) is an herbicide commonly used in sugarcane cultivation, and it raised concerns about soil and water contamination. For this study, we used Dow AgroSciences Industrial Ltd.'s Combine® 500SC (Batch: 041-14-2000), a commercially available formulation. The soil had no recorded evidence of recent pesticide use, ensuring a pristine environment for studying tebuthiuron contamination and phytoremediation interventions.

To enhance phytoremediation, microbial inoculants were used to augment the native microbial community. We sourced the inoculants from MICROGREEN® Ltd., a company specializing in soil microbial reclamation. We utilized two types of inoculants: a liquid inoculant (Liq), rich in bacterial species, and a solid inoculant (Sol), rich in fungal species. This selection was based on thoughtful consideration to optimize microbial contributions to the remediation process.

2.2. Plant Species

We selected

Mucuna pruriens (MP) and

Canavalia ensiformis (CE) based on their well-documented phytoremediation capabilities, particularly in tebuthiuron-contaminated soils.[

5,

6,

7,

8,

10] These leguminous species establish symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria, enhancing nutrient availability and soil fertility.

As a bioindicator for residual pesticide, we chose sunn hemp (

Crotalaria juncea) due to its sensitivity to tebuthiuron.[

10,

21] Sunn hemp acts as a sentinel plant, indicating soil contamination levels and aiding in the evaluation of phytoremediation efficacy. BR SEEDS

® provided the seeds of

C. juncea,

C. ensiformis and

M. pruriens, ensuring uniformity and reliability of the experimental material.

Additionally, we obtained commercially available seeds of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) from Feltrin Sementes® (Brazil) for ecotoxicological bioassays, whose application is generally present in recent studies with soil decontamination with pesticides. Bioassays offer an indirect approach to confirm the presence of tebuthiuron in soil samples.

2.3. Experimental Design

Experiments were conducted using a completely randomized design, coupled with a 2 × 3 × 3 factorial scheme, with seven replicates. The factors included tebuthiuron concentration (presence or absence), microbial inoculant type (liquid, solid, or absence), and plant species (C. ensiformis, M. pruriens, or absence).

This comprehensive approach allowed for a thorough investigation of the independent and combined effects of these variables on the study parameters. Randomization minimized bias and ensured equal representation of treatment groups across experimental units.

Experimental Units

Before conducting the experiment, the soil underwent a preparatory phase to adjust its acidity and fertility, following the procedures outlined in [

8] and [

10]. For every 504 kg of soil, the following amendments were meticulously applied: 454 g of limestone to regulate pH, 10 g of urea as a nitrogen source, 56 g of single superphosphate for phosphorus supplementation, and 13 g of potassium chloride to ensure sufficient potassium levels for optimal plant growth. These amendments were introduced to guarantee the soil's nutrient content reached ideal levels. After their addition, the soil was thoroughly mixed, and then it was used to fill pots, each with a capacity of approximately 4.0 L.

Both liquid (Liq) and solid (Sol) microbial inoculants were incorporated into the soil. The solid inoculant was introduced at a rate of 0.36 g per pot, while the liquid counterpart was applied at a volume of 50 mL per pot. These inoculants were directly administered to the pots according to their respective treatment groups. Three days after integrating the inoculants into the soil, we applied the herbicide Combine® 500 SC at a rate of 2 L per hectare (equivalent to 1000 g of active ingredient per hectare). This application rate is recommended for sandy textured soils in sugarcane crops. We carried out the spraying using a medium-sized laboratory sprayer. Throughout the application process, we diligently monitored environmental conditions, and the recorded temperature and moisture levels were 27.2 ºC and 63%, respectively.

Seven days after applying the herbicide, we sowed three seeds each of C. ensiformis (CE) and M. pruriens (MP) in every pot. These species are renowned for their phytoremediation potential, and we continued their cultivation for a period of 70 days after sowing (referred to as DAS). Three days after harvesting these plants, we sowed three sunn hemp seeds in each pot. Sunn hemp was also cultivated for 70 days. To ensure optimal growth and development conditions for all cultivated plants, we water daily. By adhering to this comprehensive methodology, our experimental setup created an ideal environment for investigating the tolerance and phytoremediation capabilities of C. ensiformis and M. pruriens, in addition to assessing the influence of microbial inoculants, all in the presence of tebuthiuron-contaminated soil.

2.4. Plant Growth and Development Evaluation

Throughout the duration of the experiment, we closely monitored the growth of all plants on a weekly basis, meticulously recording their height measurements in centimeters. Upon reaching the 70-day mark (referred to as 70 DAS), we carefully extracted the plants from each treatment group in our experimental units. These plants underwent a thorough cleaning process to eliminate any soil clinging to their roots and were subsequently placed in an oven equipped with forced air circulation, maintained at a temperature of 65 ºC, for a duration of 72 hours. This meticulous drying procedure ensured the complete elimination of moisture from the plant material.

Following the drying process, we weighed the plants and collected data on their dry biomass in grams. This information on dry biomass serves as a dataset, offering profound insights into the growth and productivity of the plants under various treatment conditions. It allows for a comprehensive analysis of their phytoremediation potential and their response to tebuthiuron contamination, thus contributing significantly to the overall understanding of their performance.

Ecotoxicological Bioassays

In the study, the ecotoxicological potential of the treatments was assessed at specific time points: 0 (at the start of

M. pruriens and

C. ensiformis cultivation), 20, 40, 60, 70 (at the end of

M. pruriens and

C. ensiformis cultivation), and 140 DAS (at the end of

C. juncea cultivation). The bioassays were conducted following the methodologies described in NBR 10006 [

22] and [

23].

L. sativa seeds were used as the test organism. During the bioassays, data were collected on seed germination, hypocotyl (shoot) elongation, and root elongation. These parameters were used to calculate the total germination index of the lettuce seeds, as described in Equation 1 by. [

24]

In this equation:

GI represents the germination index,

G% denotes the percentage of seed germination, and

R% indicates the percentage of root elongation.

The germination index provides a comprehensive measure of seed germination and root elongation, considering both parameters. By calculating the germination index using the percentages of seed germination and root elongation, a combined indicator of overall seedling performance can be obtained. This approach allows for a holistic assessment of the ecotoxicological effects of the treatments on L. sativa, considering both germination and root development as indicators of plant health and response to potential contaminants.

2.5. Statistical Data Analysis

Before conducting the statistical analysis, data were tested for homoscedasticity (equality of variances) and normality. The Bartlett test was used to assess variance equality, while the Shapiro-Wilk test determined data normality. Once these assumptions were met, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied at a significance level of 5% to determine significant differences between treatment groups. Post-hoc tests (Tukey test, p<0,05) were employed for pairwise comparisons. Plant height and germination index data were analyzed using the Gompertz sigmoid function (

Eq. 2) to estimate growth dynamics and inflection points over time. A mixed linear model (

Eq. 3) was used to account for individual variability within the experiment. Statistical software (R, GraphPad Prism, and Microsoft Excel

® 2019) facilitated data analysis, model estimation, hypothesis testing, and generation of statistical summaries for interpretation.

In this equation:

fx represents the plant height in centimeters or the germination index,

x denotes the time in days after sowing (DAS),

α represents the upper asymptote or the maximum height development and germination index that the plants can reach,

β indicates the inflection point, which corresponds to the time when the growth rate starts to decrease,

k represents the exponential decay of the specific growth rate, indicating how quickly the growth rate decreases over time, and

e represents Euler's constant, a mathematical constant approximately equal to 2.71828.

In this equation:

γ represents the dependent variable (e.g., plant height or germination index),

α denotes the global intercept of the model,

β represents the random effect (tebuthiuron),

ti indicates the time in days after sowing (DAS),

fi1 represents the fixed effect 1 (green manure),

fi2 represents the fixed effect 2 (inoculant), and

ε represents the residual term.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Soil’s Properties: Enhancing Fertility through Green Manure

Significant improvements in the soil's chemical attributes due to soil chemical correction and the cultivation of

M. pruriens and

C. ensiformis were demonstrated in

Table 1. Various nutritional parameters exhibited numerical increases, indicating enhanced soil fertility. Importantly, the concentration of Al

3+ did not increase, which is advantageous as high levels of this element can inhibit root growth.[

25]

Implementing appropriate agricultural practices, such as soil chemical correction and green manure planting, can have multiple positive effects. One of these effects is the promotion of microorganism populations capable of atmospheric nitrogen fixation.[

26] Biological nitrogen fixation contributes to increased soil fertility and plant nutrition.[

4] Additionally, the presence of plants and soil microorganisms in agrosystems can lead to the release of organic acids. These organic acids aid in the solubilization of essential nutrients such as phosphorus and potassium, rendering them more available for plant uptake. Moreover, they contribute to an increase in the soil's cation exchange capacity, which helps reduce toxic levels of aluminum, benefiting plant growth and development.[

27]

3.2. Production of Green Manure with Microbial Inoculation: Unveiling the Biocatalytic Phytoremediation

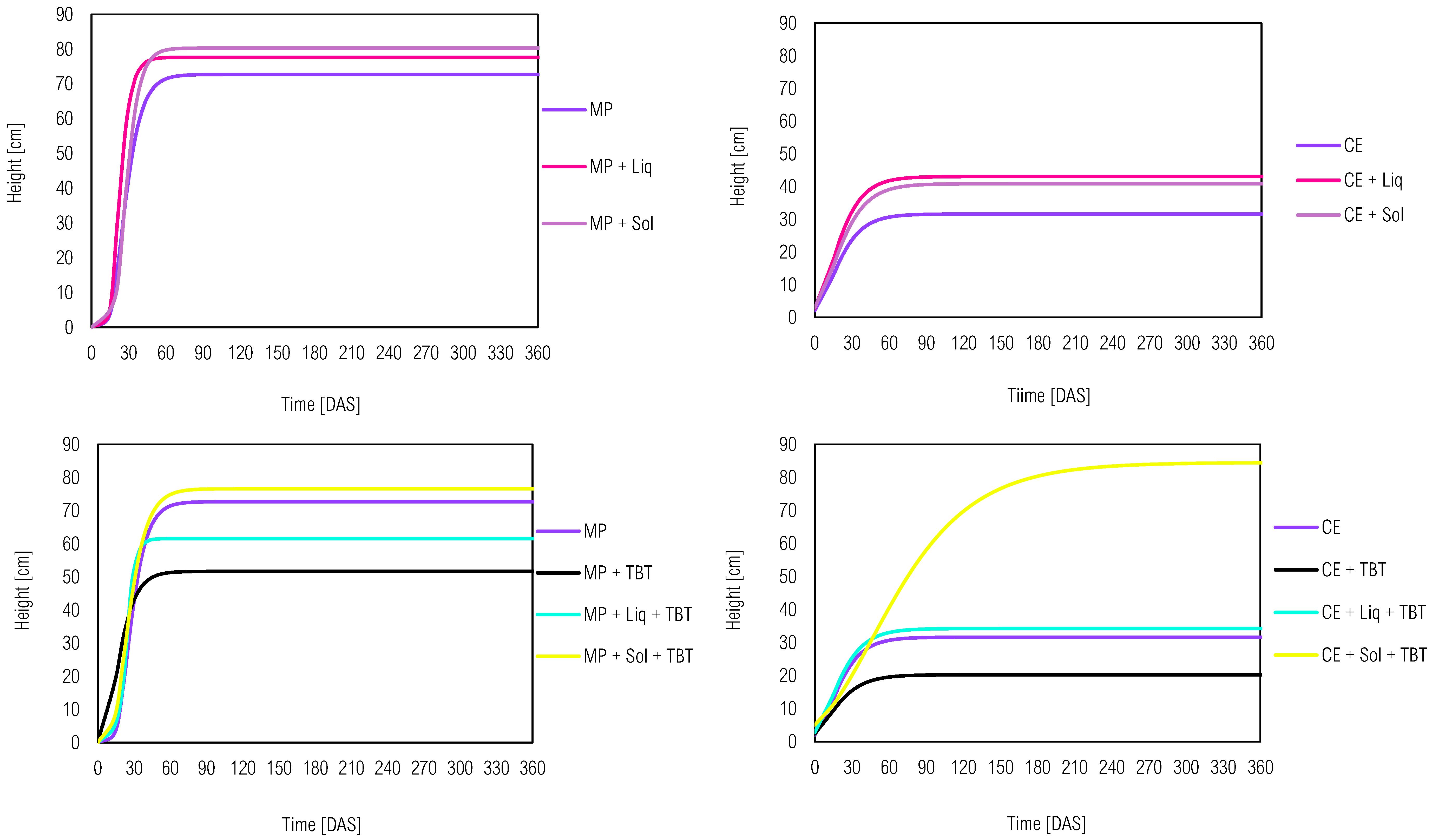

3.2.1. Growth Dynamics

Canavalia ensiformis e

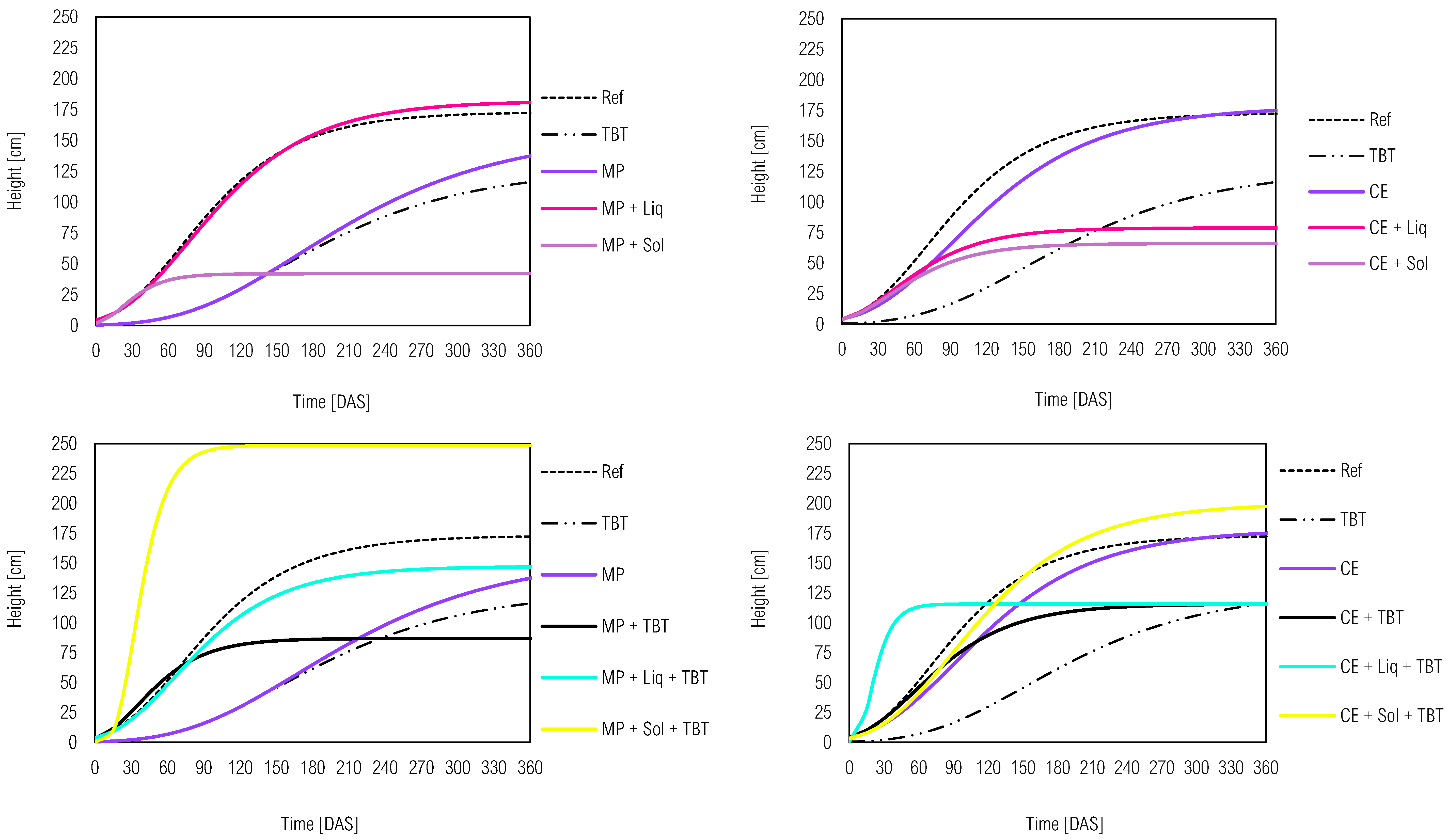

Mucuna pruriens growth dynamics revealed distinct patterns (

Figure 1), with MP exhibiting a faster growth rate as evidenced by its steeper growth curve compared to CE.

Table 2 shows all the parameters of the growth curve for each plant, such as the apex of growth (α), the inflection point of the curve (β) and, the specific growth rate (k). A higher specific growth rate value, closer to 1, indicates faster plant growth, which was observed in both MP (k = 0.113) and CE (k = 0.075). Notably, the presence of microbial inoculants did not significantly alter the curve behavior, as MP treatments consistently outperformed CE in growth rate. However, within the MP group, the solid inoculant application (MP + Sol) demonstrated even faster growth than the liquid inoculant (MP + Liq) and MP alone. Similarly, to CE, the addition of liquid inoculant (CE + Liq) exhibited faster growth compared to the solid inoculant treatment (CE + Sol) and CE alone.

Regarding the tebuthiuron’s impact, it is evident that its introduction led to a reduction in the plant’s height compared to the reference plants (MP e CE). It can be seen in

Table 2 that the MP + TBT soil sample showed a greater reduction compared to CE + TBT in several height-related parameters, including rapid establishment, growth apex (α) and specific growth rate (k) (51.69 > 20.27; 0.109 > 0.069). Previous studies by [

8] and [

28] have also reported

C. ensiformis’ sensitivity to tebuthiuron, suggesting that this plant may not be well-suited for phytoremediation of soil contaminated with this herbicide. However, it is worth noting that other studies by [

5] and, [

7] have highlighted

C. ensiformis’ capability to tolerate and even degrade tebuthiuron due to specific microorganisms present in its rhizosphere. This underscores the significance of considering specific plant-microbe interactions when selecting phytoremediators for contaminated soil.

About

M. pruriens, [

10] demonstrated a 15% decrease in height when exposed to tebuthiuron. However, the phytotoxicity of tebuthiuron was mitigated by the addition of an industrial by-product (vinasse 150 m

3 ha

−1), allowing the development of its architectural structures even in the presence of a high tebuthiuron concentration (2 L ha

−1). Our research outcomes may vary from previous studies due to diverse factors, including experimental location, soil type, moisture levels, environmental temperature, and luminosity frequency. These variables can directly influence the efficiency of phytoremediation of contaminants and should be carefully considered when selecting potential phytoremediators for pesticide-contaminated soil. Understanding the complex interactions between pesticides, plants, and environmental factors is critical to make informed decisions in this context.[

29]

A noteworthy finding was the mitig”ting’effect of inoculants on sensitivity in plant species in tebuthiuron-contaminating soil, which resulted in rapid growth and increased height. This phenomenon was particularly pronounced in C. ensiformis, where the CE + TBT treatment exhibited lower results compared to the others involving this species. It is essential to mention that inoculants effects varied among plants. MP + Sol + TBT interaction showed a higher curving slope than MP + Liq + TBT, but the latter association displayed a higher growth rate (k = 0.227) compared to the former (k = 0.100). However, MP + Sol + TBT achieved a higher maximum height (α = 76.63). Conversely for C. ensiformis, the association CE + Liq + TBT exhibited a higher specific growth rate (k = 0.071), but only CE + Sol + TBT achieved the maximum height (α = 84.52).

To summarize, these results highlight the promising outcomes of combining plants and microorganisms for remediation purposes. Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of such combinations. [

30] demonstrated the remediation of soils contaminated with the fungicide pentachloronitrobenzene with solid bacterial inoculum

Cupriavidus sp. YNS-85 in association with

Panax notoginseng. Similarly, [

31] observed a substantial removal of atrazine from soil within 40 days with the combination of

Trichoderma sp. and

Phaseolus vulgaris.

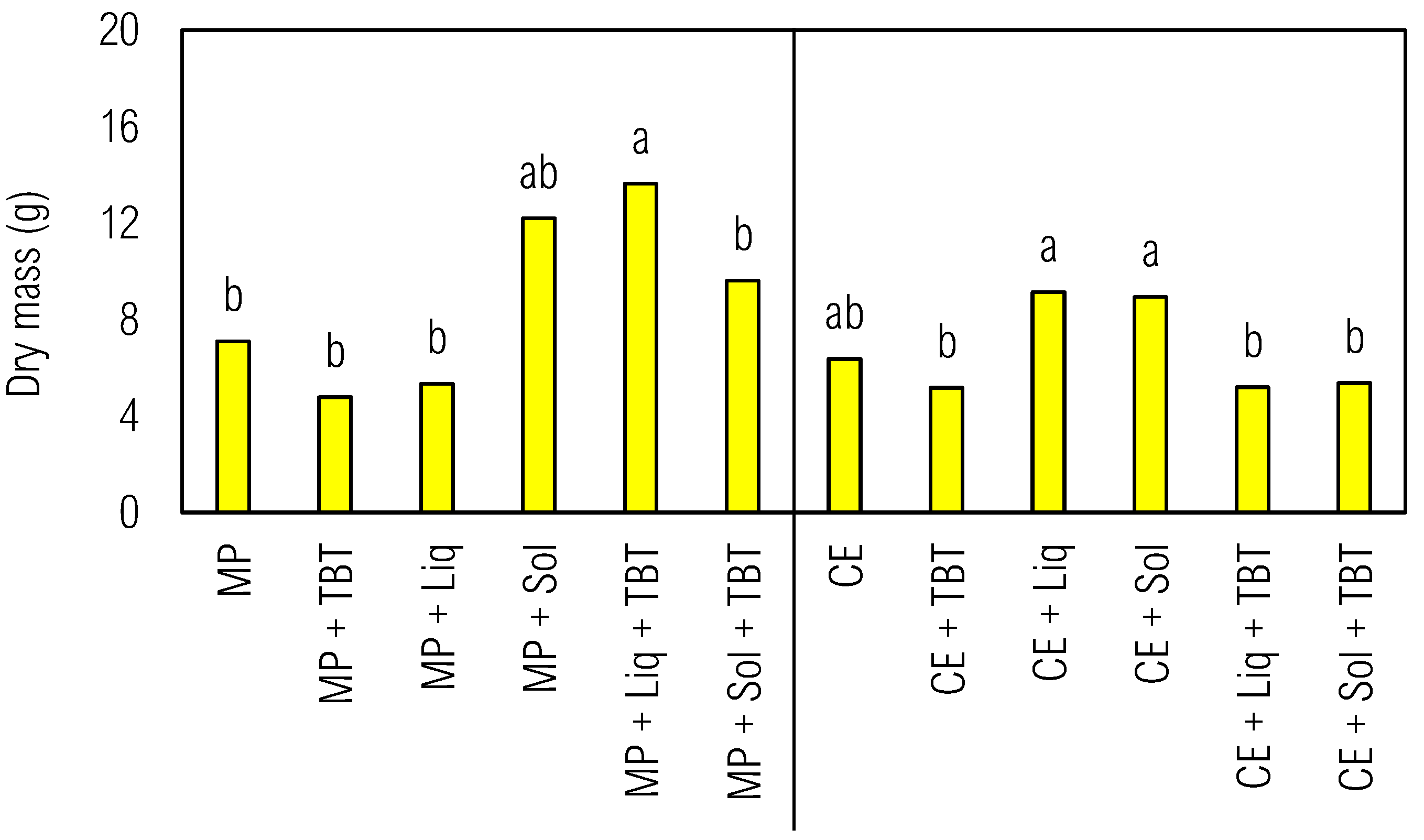

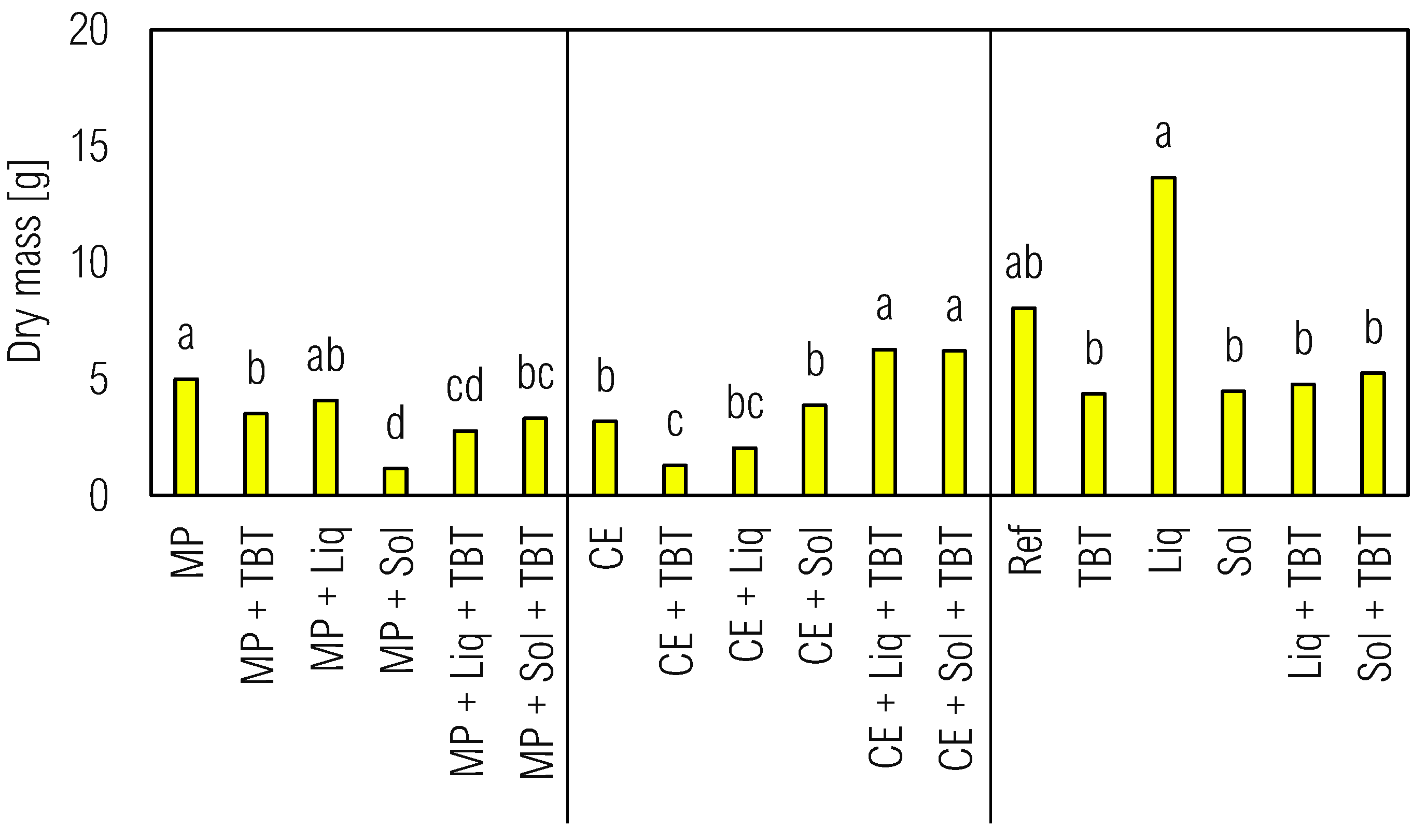

3.2.2. Phytomass Accumulation

Soil samples with microbial inoculants without tebuthiuron led to a significant increase in biomass compared to the control (

Figure 2). This positive impact underscored the efficacy of microbial inoculants in promoting plant growth and enhancing phytomass production. Such result is pivotal for the plants’ capacity to tolerate and effectively remediate contaminated soils. In contrast, the introduction of the herbicide had an adverse effect on the system and reduced phytomass production in both species, with MP + TBT displaying the most pronounced reduction. TBT negative influence on photosynthesis during plant development can impair biomass production and compromise the overall efficiency of phytoremediation processes,[

32] although the evaluated species (CE and MP) are not listed as target-plants of the commercial product used in agroecosystems. It is well-established that efficient biomass production is crucial for facilitating the transformation of pollutants into less toxic substances, a process that thrives when plants grow without facing intense stresses.[

33]

A closer examination of inoculants effect on MP biomass accumulation revealed that the liquid inoculant contributed more significantly to TBT presence, offering better support to the plant compared to the solid inoculant, which was adversely affected by this herbicide. However, concerning

C. ensiformis, microbial inoculation did not yield a substantial increase in phytomass when tebuthiuron was presented, despite contributing to the plants' increased height. These observations emphasized the limitations of relying solely on variables such as height and biomass accumulation for evaluating phytoremediation efficiency. Multiple uncontrolled factors can influence the bioavailability and environmental behavior of the herbicide.[

34] As such, the further cultivation of bioindicator plants and the implementation of ecotoxicological bioassays are complementary and indispensable approaches in comprehensively assessing environmental reclamation.[

35]

Therefore, we shed light on the critical aspect of biomass accumulation in the context of our potential phytoremediators, highlighting the favorable impact of microbial inoculants in TBT absence and conversely the detrimental herbicide effect on phytomass production. We underscore the significance of considering multiple parameters and complementary approaches in assessing the efficiency of phytoremediation, which allow sustainable and effective soil remediation practices.

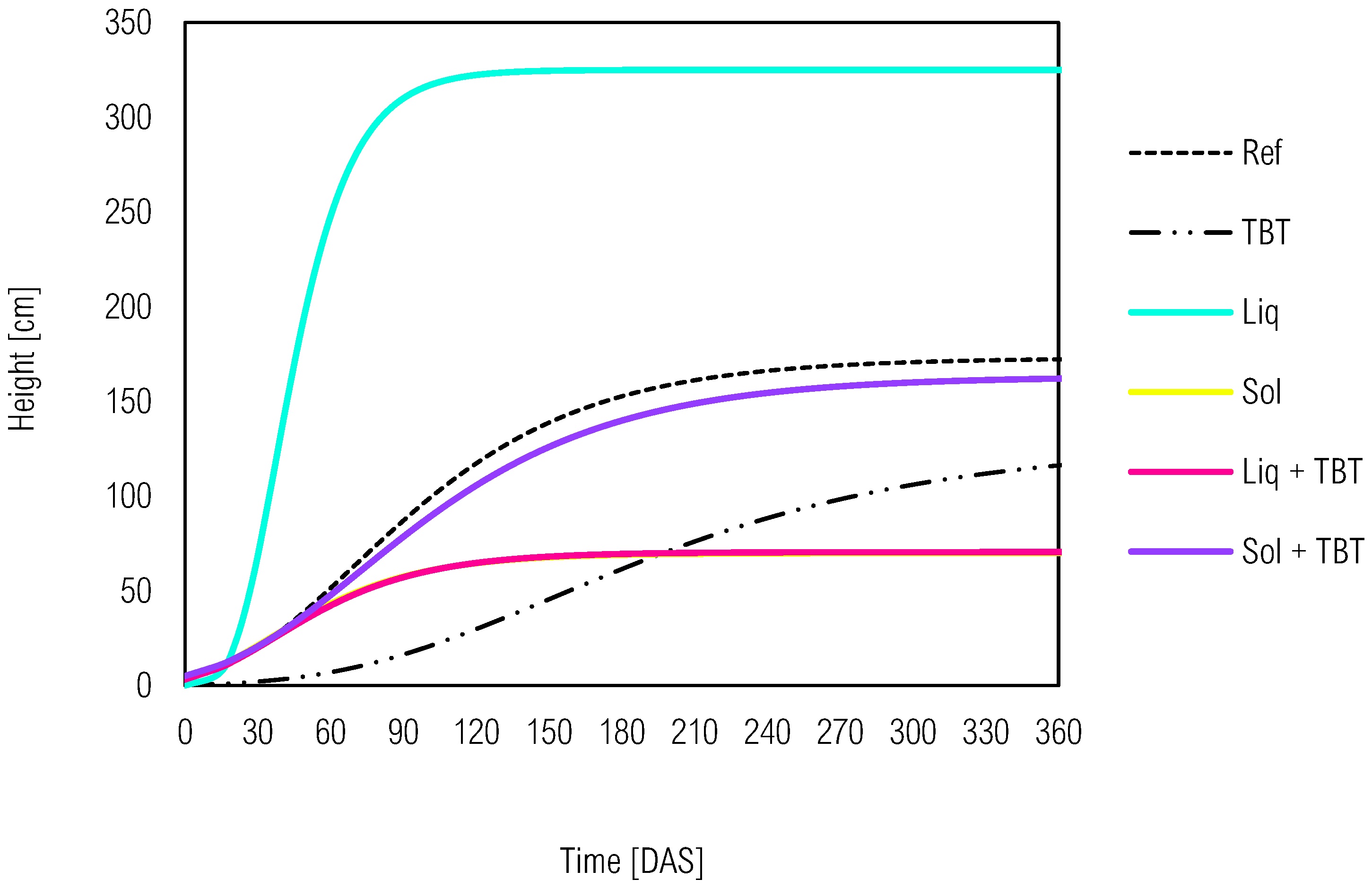

3.3. Production of C. juncea: Evaluating Ecotoxicity and Phytoremediation Efficiency

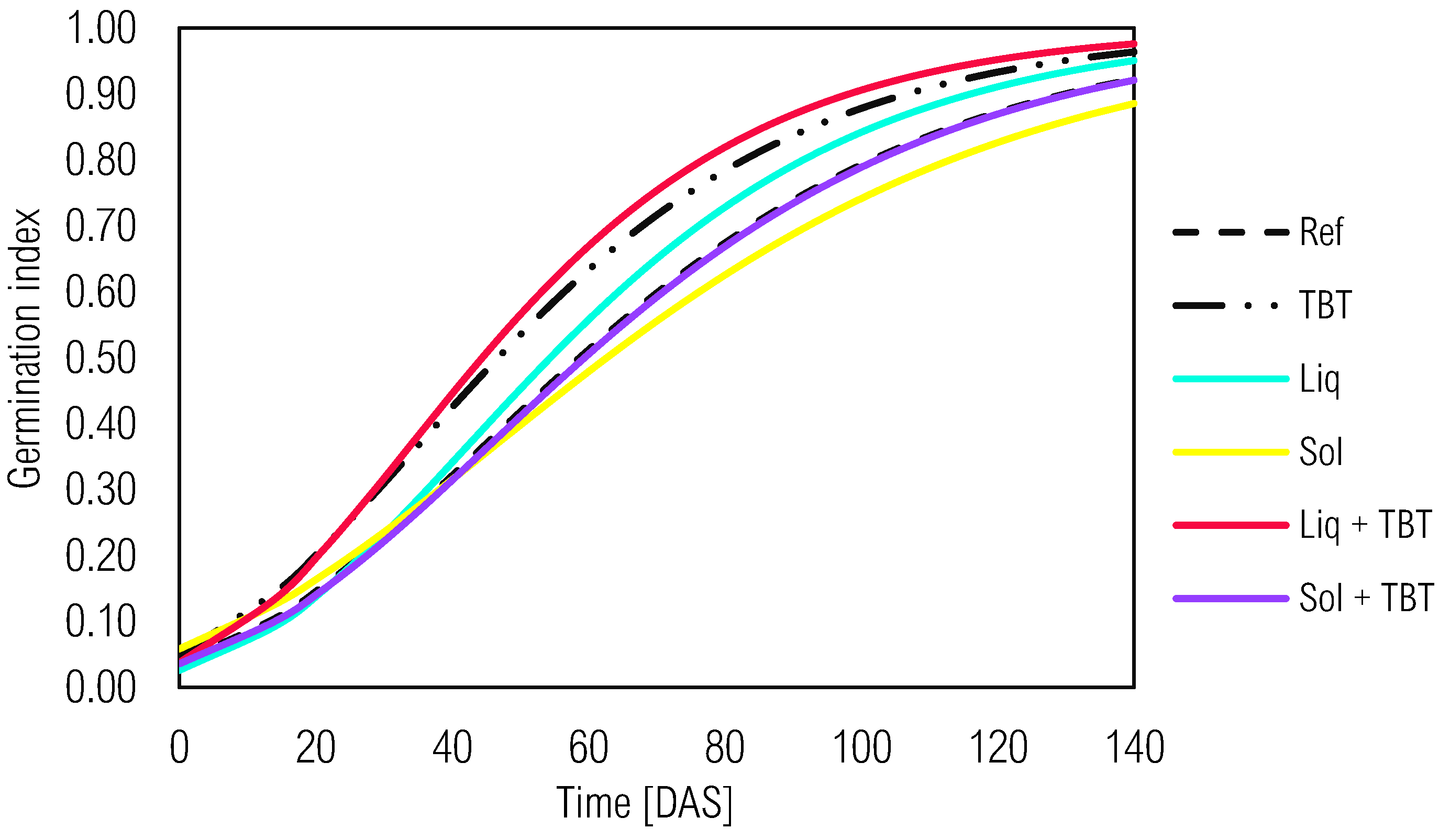

3.3.1. Growth Dynamics

The reference treatment (Ref) without prior plant cultivation (CE or MP), inoculants (Liq or Sol) and herbicide (TBT) exhibited slow development for the bioindicator species (

Figure 3). However, the soil with Liq showed faster growth (k=0.0582) and greater height (α=324.99) at around 60 DAS in

Table 3. In contrast, Sol had minimal contribution to

C. juncea's development as indicated by the prolonged growth period (k=0.0302) and lower maximum height (α=69.95).

Thereby, TBT presence promoted a lower specific growth rate (k=0.0115) to the bioindicator. However, despite slow growth,

C. juncea in soil with TBT alone reached a maximum height exceeding 100 cm, higher than Sol and Liq + TBT, which exhibited similar growth curves. Additionally, the phytotoxic effect of tebuthiuron was mitigated solid inoculant and suggested the involvement of microorganisms in bioremediation. While specific microorganisms responsible for tebuthiuron degradation were not identified, previous studies have associated

Methylobacterium,

Microbacterium,

Paenibacillus, and

Streptomyces with tebuthiuron degradation. [

36,

37]

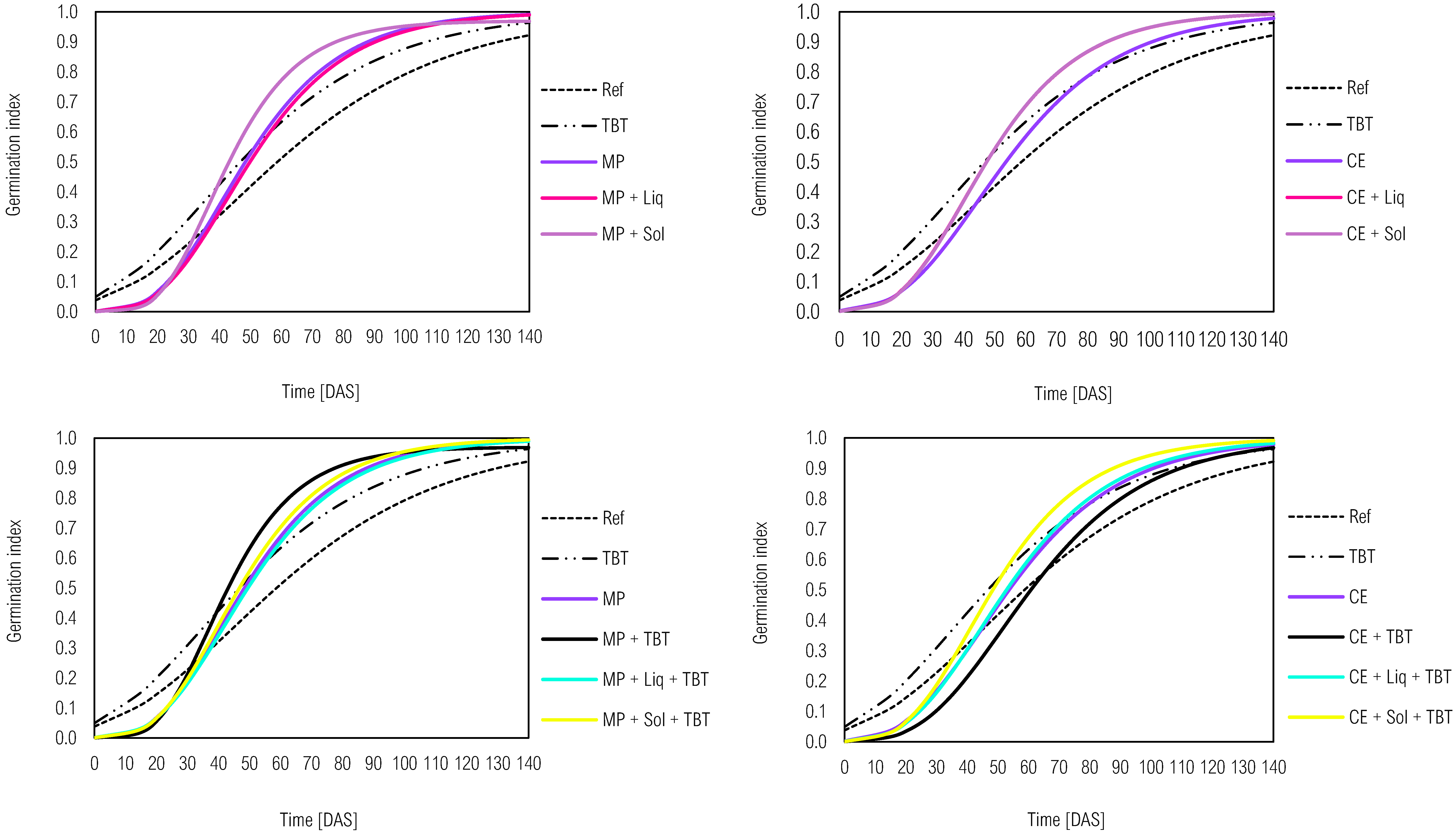

The previous cultivation of

M. pruriens and

C. ensiformis (

Figure 4) significantly influenced the development of the bioindicator plant. CE had a more positive effect on

C. juncea's growth compared to MP, where the parameters α and k for CE were greater than for MP (78.13>156.35; 0.0149>0.0106) in

Table 3.

M. pruriens, while beneficial for soil health due to nitrogen fixation and nutrient cycling, also exhibited allelopathic effects that can inhibit nearby plant growth through the production of various chemicals.[

38] Interactions between green manure species and microbial inoculants yielded distinct results in

C. juncea's development. The negative effect of

M. pruriens was absent when associated with the liquid inoculant (MP + Liq), with a higher specific growth rate (k=0.0174) and maximum height (181.96 cm) compared to MP alone. However, the association of

C. ensiformis with the liquid inoculant (CE + Liq) had an antagonistic effect on the bioindicator plant's development with a smaller growth curve compared to the soil with CE alone. Similarly, the association of solid inoculants with any of the phytoremediation species was detrimental to

C. juncea, particularly in MP + Sol, whose the maximum height value (42.01 cm) was the lowest, although the growth rate showed a higher value (k=0.0529).

Analyzing

Figure 4 and

Table 3, soil samples with TBT and CE or MP exhibited high phytotoxicity and severe growth limitation to

C. juncea compared to the control treatment with these plants. Nevertheless, the growth rate along the curve after the prior cultivation with herbicide remained higher than that of the control tests, ranging from 0.0330 for MP + TBT to 0.0214 for CE + TBT. The high concentration of phytoharmful compounds in soil and the natural senescence of potential phytoremediators and sentinel species contribute to these adversities.[

8]

Remarkably, the presence of the solid inoculant reduced the phytotoxic effect of tebuthiuron, which was evident in MP + Sol + TBT, where C. juncea exhibited rapid growth (k=0.0659), a nearly vertical growth curve, and an impressive height (α=248.45). This indicated the Sol potential in mitigating the tebuthiuron toxicity. Similar results were observed in CE + Sol + TBT treatment, where the height value was higher (α=199.88) compared to the other treatments with the same species. Therefore, the long-term presence of the solid inoculant could contribute to tebuthiuron dissipation. Furthermore, the liquid inoculant also exhibited a mitigating effect, but lower than Sol. C. juncea's growth rate was higher only in CE + Liq + TBT (k=0.0930), and the height variable exhibited medium-high values for MP + Liq + TBT (α=147.18) compared to the other treatments with the same species, which indicated that Liq can aid in tebuthiuron remediation in soil, albeit with some limitations (Melo et al., 2019).

To summarize, these findings offer a detailed assessment of plant height and the cultivation of the bioindicator C. juncea. The results elucidate the impact of microbial inoculants and the herbicide tebuthiuron on the growth and development of the bioindicator plant, underscoring the potential of certain inoculants in mitigating the herbicide's phytotoxic effects. These findings contribute pertinent toa the realm of phytoremediation and its efficiency in addressing pesticide-contaminated soils.

3.3.2. Phytomass Accumulation

The microbial inoculation in uncultivated soil showed that liquid inoculant promoted highest dry biomass accumulation in

C. juncea (

Figure 5). However, tebuthiuron introduction significantly reduced the biomass, which indicated the high sensitivity of

C. juncea to residual TBT concentrations even after a 70-day period in soil. The herbicide persistence could be attributed to the substantial organic matter content in the agrosystems (

Table 1) and enhanced TBT sorption. Bioaugmentation, although yielding limited results in reducing herbicide phytotoxicity across different inoculants, exhibited similar efficiencies among the tested inoculants. Absence of tebuthiuron in treatments where

M. pruriens and

C. ensiformis were pre-cultivated, with or without microbial inoculation, did not significantly impact the dry biomass accumulation in

C. juncea plants (

Figure 5).

Importantly, pre-cultivation with

C. ensiformis did not lead to substantial biomass accumulation in the sentinel plant, aligning with previous observations that

C. ensiformis has limited ability to reduce tebuthiuron and its metabolite concentrations in the soil (Ferreira et al., 2021). Contrasting results have been reported in studies by [

35] and [

39], where

C. ensiformis pre-cultivation reduced the phytotoxic effect of the herbicide sulfentrazone on the bioindicator plant. Interestingly, in the absence of tebuthiuron, natural attenuation (TBT) resulted in significantly positive biomass accumulation in the sentinel plant, likely due to environmental biostimulation. Prior fertilization of the soil enriched the system with nutrients available in the soil solution, potentially enhancing the ability of the native microbiota to dissipate the herbicide.

Furthermore, bioaugmentation contributed to the reduction of herbicide sensitivity in

C. juncea plants. Treatments without plant pre-cultivation, such as Sol + TBT (5.25 g) and Liq + TBT (4.78 g), exhibited higher dry biomass values compared to TBT alone (4.36 g). Similar results were observed in a study by [

39], where a bacterial consortium pre-cultivated in sulfentrazone-contaminated soil resulted in increased sorghum dry matter. The association between plants and inoculants in tebuthiuron-contaminated soil was more effective in treatments involving

C. ensiformis, indicating a greater contribution and dependence of

C. ensiformis on the association with microbial inoculants. However, the effectiveness of bioaugmentation in pre-cultured treatments with

M. pruriens was not significant. M. pruriens alone successfully mitigated the phytotoxic effects of tebuthiuron on the sentinel plant, as supported by

Figure 5, where the MP + TBT treatment (3.52 g) displayed a higher dry biomass value compared to MP + Sol + TBT (3.31 g) and MP + Liq + TBT (2.77 g).

Several factors may account for the limited impact of bioaugmentation in

M. pruriens treatments, such as the presence of residual pesticides and their interactions with plants and soil microbiota, which can vary depending on the experimental conditions, soil properties, environmental factors, and specific plant-microbe interactions.[

40] These factors can influence the phytoremediation efficiency and the ability of plants to tolerate and degrade pesticides.[

41]

To summarize, these findings purvey a comprehensive perspective of biomass accumulation in the bioindicator plant C. juncea under various treatments. The results shed light on the efficacy of different inoculants and the herbicide tebuthiuron in phytoremediation processes. Understanding the complex interactions between plants, microorganisms, and pesticides is essential for enhancing the efficiency of phytoremediation and ensuring successful environmental reclamation.

3.4. Bioassays with L. sativa: Validating Ecotoxicity and Phytoremediation Efficiency

Ecotoxicity testing with lettuce seeds emerges as a pivotal tool for evaluating soil quality, particularly in environments potentially affected by herbicides like tebuthiuron. This indirect method not only underscores the herbicide's presence but also verifies a reduction in soil toxicity. Additionally, ecotoxicity tests using

L. sativa were conducted by multiple researchers following biological pesticide remediation experiments [

3,

8,

10,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

The germination index (GI) of

L. sativa seeds is commonly used in ecotoxicological bioassays to assess the effectiveness of soil bioremediation due to the test-organism's sensitivity to disturbed environments. In uncultivated soil samples (

Figure 6), the reference treatment (Ref) initially showed significantly higher GI compared to others without tebuthiuron (0 to 40 DAS). However, bioaugmentation with the liquid inoculant (Liq) resulted in a higher final GI than Ref and the solid inoculant (Sol) (0.95 > 0.92 > 0.89). The growth rate (k value) was also higher for Liq and indicated its action as a growth promoter for lettuce seeds. Over time, soil samples containing only TBT demonstrated a higher final germination index (0.96) and growth velocity (k = 0.0314) compared to Ref. Such informations can be shows in

Figure 6 and

Table 4. These findings suggested the possible action of natural attenuation in reducing the toxicity of lettuce seeds.

Recent studies support that natural attenuation efficiency in TBT-contaminated soil is time-dependent.[

3,

10,

19,

42,

43] The native microbiota can gradually dissipate the herbicide and reduce environmental toxicity for

L. sativa. Moreover, the impact of microbial inoculants in soil with TBT was found to be divergent. The germination index and growth rate were higher in soil with Liq compared to Sol (α = 0.98 > 0.92; k = 0.0350 > 0.0264) in

Table 4. Furthermore, in soil samples with tebuthiuron, the initial GI was low but increased over time, particularly with Sol that suggested its contribution to ecotoxicity decrease.

The previous cultivation of

M. pruriens followed by the subsequent cultivation of crotalaria positively influenced the development of lettuce (

Figure 7). GI was initially lower than Ref between 0 and 40 DAS but gradually increased until reaching 0.99 in

Table 4. The growth rate (k) of the

M. pruriens treatment was also higher compared to Ref (0.0477 > 0.0264) in

Table 4. Thus, the previous cultivation of

M. pruriens and

C. ensiformis may have improved the soil's chemical, physical, and biological attributes, which benefited the development of

L. sativa seedlings. Furthermore, the association between microbial inoculants and

M. pruriens resulted in a higher growth rate (k = 0.0632) in soil samples without tebuthiuron compared to

M. pruriens alone (k = 0.0477). However, GI showed the opposite pattern (ME = 0.99 > ME + TBT = 0.97), suggesting that microbial inoculation may reduce the negative ecotoxicological impact of tebuthiuron.

To summarize, the germination index of L. sativa furnished significant information on the soil ecotoxicity and the efficiency of phytoremediation processes. Herbicides like tebuthiuron can hinder seed germination and seedling growth, but natural attenuation and microbial inoculation (bioaugmentation) can mitigate these effects over time. The association of legume species, such as M. pruriens and C. ensiformis, with microbial inoculants demonstrated positive effects in reducing ecotoxicity in soil samples, which indicated the potential for effective phytoremediation strategies. However, the complexity of interactions between plant species, microorganisms, and pesticides warrants careful consideration in designing successful phytoremediation approaches for contaminated soils.

3.5. Limitations and Directions to Improve the Credibility and Practicality of Phytoremediation

According to our results, it is essential to strengthen the credibility and practicality of phytoremediation as a sustainable soil management technique. Therefore, future research should consider the following aspects to develop new perspectives and supply a more comprehensive understanding,

According to our results, it is essential to strengthen the credibility and practicality of phytoremediation as a sustainable soil management technique. Therefore, future research should consider the following aspects to develop new perspectives and provide a more comprehensive understanding.

Firstly, field trials are essential to evaluate the effectiveness of these methods under real conditions, considering soil variability and environmental factors. Long-term monitoring is crucial to assess the sustainability and persistence of contaminants. Several plant species must be examined to identify those that are best suited to specific pollutants and soil conditions, considering their physiological characteristics and potential allelopathic effects. Furthermore, investigations into multiple contaminants and realistic soil heterogeneity are needed to develop tailored remediation approaches. Economic analyzes are vital to assess the cost-effectiveness of phytoremediation compared to traditional methods. Lastly, a comprehensive microbial analysis is essential to understand microbial community dynamics and identify the key taxa that drive contaminant degradation, aiding in the design of efficient bioremediation strategies.

In this way, we can advance our understanding of the potential of phytoremediation as a more practical and effective tool for the remediation of agricultural soils. Ultimately, this knowledge will contribute to sustainable land management practices, minimize environmental impacts, and promote healthier agricultural ecosystems.

Accordingly, we can advance our understanding of phytoremediation's potential as a more practical and effective tool for remediating agricultural soils. Ultimately, this knowledge will contribute to sustainable soil management practices, minimize environmental impacts, and promote healthier agricultural ecosystems.

3.6. Future Perspectives

Advancements in research are expected to uncover new plant-microbe interactions that enhance phytoremediation efficiency, offering possibilities for tailoring remediation approaches to specific contaminants and environments. Genetic engineering shows potential for creating transgenic plants with enhanced capabilities, though ecological risks and regulatory considerations must be carefully evaluated. As global environmental concerns escalate, the practical application of phytoremediation on a larger scale gains significance, necessitating consideration of regional variations and integration with other remediation techniques. Urban and aquatic environments also stand to benefit from phytoremediation, albeit with unique challenges and opportunities. Effective implementation will require clear policies, collaborative efforts, public engagement, and trust-building initiatives to ensure safe and successful adoption of this eco-friendly remediation method.

4. Conclusions

The study on biocatalytic phytoremediation of tebuthiuron-contaminated agricultural soil highlighted promising findings regarding the potential of Mucuna pruriens and Canavalia ensiformis for remediation. M. pruriens exhibited faster growth than C. ensiformis, indicating differences in their phytoremediation capabilities. However, both plants were hindered in development by the presence of the herbicide Tebuthiuron, although this phytotoxicity was mitigated and plant growth enhanced by microbial inoculants. Interestingly, solid inoculants proved more effective than liquid ones in reducing phytotoxic effects and improving plant performance. Moreover, C. ensiformis showed a greater reliance on bioaugmentation compared to M. pruriens, suggesting differing responses to biodegradation enhancement strategies. Bioassays confirmed the adverse effects of tebuthiuron, but these were alleviated through natural attenuation and bioaugmentation methods. Combining green manure planting with microbial inoculants synergistically improved the decrease in ecotoxicity, emphasizing the importance of comprehensive strategies for effective phytoremediation of pesticide-contaminated soils. These findings underscore the significance of understanding plant-microbe interactions and developing holistic approaches for successful remediation efforts, though further research and field trials are warranted for practical application in real-world scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: VHC, VLS, PRML; Methodology: VHC, EBM, LGV; Investigation: VHC, TSV, YAF; Data curation: BRAM, PRML; Formal analysis: VHC, BRAM; Writing Original draft: VHC, BRAM, YAF, PRML; Review and editing: VHC, EBM, LGV, LT, EPP, PRML; Funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision and validation: PRML.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP-Brazil, 2021/01884-6); the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq-Brazil, 313530/2021-1), the Fundação Agrisus – Brazil (PA 3740/24), the Coordination for Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES-Brazil, financing code n.001); and Pro-Rectory of Graduate Studies (Pró-Reitoria de Pós-Graduação) of São Paulo State University (Unesp-Brazil).

References

- Qian, Y., Matsumoto, H., Liu, X., Li, S., Liang, X., Liu, Y., Zhu, G., & Wang, M. (2017). Dissipation, occurrence and risk assessment of a phenylurea herbicide tebuthiuron in sugarcane and aquatic ecosystems in South China. Environmental Pollution, 227, 389–396. [CrossRef]

-

PPDB - Pesticide Properties DataBase: Tebuthiuron (Ref: EL 103) (2023). Available in: http://sitem.herts.ac.uk/aeru/iupac/Reports/614.htm.

- Lima, E.W., Brunaldi, B.P., Frias, Y.A., Moreira, B.R.A, Alves, L.S., & Lopes, P.R.M. (2022). A synergistic bacterial pool decomposes tebuthiuron in soil. Scientific Reports, 12, 9225. [CrossRef]

- Barroso, G.M., Santos, E.A., Pires, F.R., Galon, L., Cabral, C.M., & Santos, J.B. (2023). Phytoremediation: A green and low-cost technology to remediate herbicides in the environment. Chemosphere, 334, 138943. [CrossRef]

- Pires, F.R., Souza, C.M., Cecon, P.R., Santos, J.B., Tótola, M.R., Procópio, S.O., Silva, A.A., & Silva, C.S.W. (2005). Inferências sobre atividade rizosférica de espécies com potencial para fitorremediação do herbicida tebuthiuron. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, 29, 627–634. [CrossRef]

- Pires, F.R., Procópio, S.O., & Souza, C.M. (2006). Adubos verdes na fitorremediação de solos contaminados com o herbicida tebuthiuron. Revista Caatinga., 19, 1, 92-97.

- Mendes, K.F., Maset, B.A., Mielke, K.C., Sousa, R.N., Martins, B.A.B., & Tornisielo, V.L. (2021). Phytoremediation of quinclorac and tebuthiuron-polluted soil by green manure plants. International Journal of Phytoremediation 23, 474–481. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.C., Moreira, B.R. A., Montagnolli, R.N., Prado, E.P., Viana, R. S., Tomaz, R.S., Cruz, J.M., Bidoia, E.D., Frias, Y.A., & Lopes, P.R.M. (2021). Green Manure Species for Phytoremediation of Soil With Tebuthiuron and Vinasse. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 8. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.C.& Lopes, P.R.M., 2021. New Approaches on Phytoremediation of Soil Cultivated with Sugarcane with Herbicide Residues and Fertigation. In Bidoia, E.D., & Montagnolli, R.N. (Eds.), Biodegradation, Pollutants and Bioremediation Principles, CRC Press, 272-282.

- Frias, Y.A., Lima, E.W., Aragão, M.B., Nantes, L.S., Moreira, B.R.A., Cruz, V.H., Tomaz, R.S., & Lopes, P.R.M. (2023). Mucuna pruriens cannot develop phytoremediation of tebuthiuron in agricultural soil with vinasse: a morphometrical and ecotoxicological analysis. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 11, 1156751. [CrossRef]

- Andreolli, M., Lampis, S., Brignoli, P., & Vallini, G. (2015). Bioaugmentation and biostimulation as strategies for the bioremediation of a burned woodland soil contaminated by toxic hydrocarbons: A comparative study. Journal of Environmental Management, 153, 121–131. [CrossRef]

- Sarapirom, P., Wiriyaampaiwong, P., Rueangsan, K., Plangklang, P., & Teerakun, M. (2022). The combination technique of bioaugmentation and phytoremediation on the degradation of paraquat in contaminated soil. Asia-Pacific Journal of Science and Technology, 27, 27–03. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, P.R.M., Cruz, V.H., Menezes, A.B., Gadanhoto, B.P., Moreira, B.R.A., Mendes, C.R., Mazzeo, D.E.C., Dilarri, G. & Montagnolli, R.N. (2022). Microbial bioremediation of pesticides in agricultural soils: an integrative review on natural attenuation, bioaugmentation and biostimulation. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., Afzal, M., Iqbal, S., & Khan, Q.M. (2013). Plant–bacteria partnerships for the remediation of hydrocarbon contaminated soils. Chemosphere, 90, 1317–1332. [CrossRef]

- Aparício, J.D., Garcia-Velasco, N., Urionabarrenetxea, E., Soto, M., Álvarez, A., & Polti, M.A. (2019). Evaluation of the effectiveness of a bioremediation process in experimental soils polluted with chromium and lindane. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 181, 255–263. [CrossRef]

- Baumann, A.J., Sadañoski, M.A., Marino, D.J.G., Alvarenga, A.E., Silva, C.G., Argüello, B. del V., & Zapata, P. D. (2024). Carbendazim mycoremediation: a combined approach to restoring soil. Mycological Progress, 23, 1, 7. [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, E.E., Saez, J.M., Aparicio, J.D., Fuentes, M.S., & Benimeli, C.S. (2020). Bioremediation of lindane-contaminated soils by combining of bioaugmentation and biostimulation: Effective scaling-up from microcosms to mesocosms. Journal of Environmental Management, 276, 111309. [CrossRef]

- Nantes, L.S., Aragão, M.B., Moreira, B.R. de A., Frias, Y.A., Valério, T.S., de Lima, E.W., Silva Viana, R., & Lopes, P.R.M. (2022). Synergism and antagonism in environmental behavior of tebuthiuron and thiamethoxam in soil with vinasse by natural attenuation. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology . [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.B.R., Cruz, V.H., Moreira, B.R. de A., Viana, R. da S. & Lopes, P.R.M. (2021). Viabilidade da atenuação natural em solo de manejo orgânico contaminado com tebuthiuron. Energia na agricultura, 36, 261–272. [CrossRef]

- Santos, H.G., Jacomine, P.K.T, Anjos, L.H.C., Oliveira, V.Á., Lumbreras, J.F., Coelho, M.R., Almeida, J.A., Araújo Filho, J.C., Oliveira, J.B., & Cunha, T.J.F. (2018). Sistema brasileiro de classificação de solos, 5a̲ Edition. ed. Embrapa, Brasília, DF. 355 p.

- Pires, F.R., Procópio, S.O., Santos, J.B. dos, Souza, C.M., & Dias, R.R. (2008). Avaliação da fitorremediação de tebuthiuron utilizando Crotalaria juncea como planta indicadora. Revista Ciência Agronômica, 39, 245–250.

- Associação Brasileira De Normas Técnicas (ABNT) (2004). Procedimento para obtenção de extrato solubilizado de resíduos sólidos. NBR 10006. Rio de Janeiro, 20 p.

- Sobrero, M.C., & Ronco, A (2004). Ensayo de toxicidad aguda con semillas de lechuga (Lactuca sativa L.). In Morales, G.C. (Ed)., Ensayos toxicológicos y métodos de evaluación de calidad de aguas: standerización, intercalibración, resultados y aplicaciones. Mexico: IMTA, p. 71-79.

- Labouriau, l.G., & Agudo, M. (1987). On the physiology of seed germination in Salvia hispanica L. I. Temperature effects. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 59, 37-56.

- Echart, C.L., & Cavalli-Molina, S. (2001). Fitotoxicidade do alumínio: efeitos, mecanismo de tolerância e seu controle genético. Ciência. Rural, 31, 531–541. [CrossRef]

- Sagrilo, E., Leite, L.F.C., Galvão, S.R.S., & Lima, E.F. (2009). Manejo Agroecológico do Solo: os Benefícios da Adubação Verde (Documentos 193). Embrapa: Teresina, PI, 22 p.

- Calegari, A. (2006). Plantas de cobertura. In Casão Junior, R., Siqueira, R., Mehta, Y.R., & Passini, J.J. (Eds.). Sistema Plantio Direto com qualidade. Londrina: IAPAR, p. 55-73.

- Belo, A.F., Santos, E.A., Santos, J.B., Ferreira, L.R., Silva, A.A., Cecon, P.R., & Silva, L.L. (2007). Efeito da umidade do solo sobre a capacidade de Canavalia ensiformis e Stizolobium aterrimum em remediar solos contaminados com herbicidas. Planta daninha, 25, 239–249. [CrossRef]

- Madalão, J.C., Souza, M.F., Silva, A.A., Silva, D.V., Jakelaitis, A. & Pereira, G.A.M. (2017). Action of Canavalia ensiformis in remediation of contaminated soil with sulfentrazone. Bragantia, 76, 292–299. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N., Guo, D., Zhu, Y., Wang, X., Zhu, L., Liu, F., Teng, Y., Christie, P., Li, Z., & Luo, Y. (2020). Microbial remediation of a pentachloronitrobenzene-contaminated soil under Panax notoginseng: A field experiment. Pedosphere, 30, 563–569. [CrossRef]

- Madariaga-Navarrete, A., Rodríguez-Pastrana, B.R., Villagómez-Ibarra, J.R., Acevedo-Sandoval, O.A., Perry, G. & Islas-Pelcastre, M. (2017). Bioremediation model for atrazine contaminated agricultural soils using phytoremediation (using Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and a locally adapted microbial consortium. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B, 52, 367–375. [CrossRef]

- Camargo, D., Bispo, K.L., & Sene, L. (2011). Associação de Rhizobium sp. a duas leguminosas na tolerância à atrazina. Revista Ceres, 58, 425–431. [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, A.A., & Oladele, F.A. (2017). Leaf size and transpiration rates in Agave americana and Aloe vera. Phytologia Balcanica, Sofia, 23, 1, 95–100.

- Christoffoleti, P.J., López-Ovejero, R.F., Damin, V., Carvalho, S.J.P., Nicolai, M., 2009. Comportamento dos herbicidas aplicados ao solo na cultura da cana-de-açúcar, Piracicaba: CP, 1ª edição, 72 p.

- Dietz, A.C., Schnoor, J.L., 2001. Advances in Phytoremediation. Environmental Health Perspectives, 109, 163–168. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.A., Pires, F.R., Ferraço, M., & Belo, A.F. (2014). The Validation of an Analytical Method for Sulfentrazone Residue Determination in Soil Using Liquid Chromatography and a Comparison of Chromatographic Sensitivity to Millet as a Bioindicator Species. Molecules, 19, 10982–10997. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, F.I.Y., & Helling, C.S. (2003). Isolation and 16S DNA Characterization of Soil Microorganisms from Tropical Soils Capable of Utilizing the Herbicides Hexazinone and Tebuthiuron. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B, 38, 783–797. [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, P.J., Johnson D.J., August, P.R., Liu, H.W., & Sherman, D.H. (1999). Characterization of a Mitomycin-binding drug resistance Mechanism from the producing organism. Bacteriology, 179, 5, 1796-1804.

- Erasmo, E. a. L., Azevedo, W.R., Sarmento, R.A., Cunha, A.M., & Garcia, S.L.R. (2004). Potencial de espécies utilizadas como adubo verde no manejo integrado de plantas daninhas. Planta daninha, 22, 337–342. [CrossRef]

- Melo, C.A.D., Passos, A.B.R. de J., Madalão, J.C., Silva, D.V., Massenssini, A.M., da Silva, A.A., Costa, M.D., & Souza, M.F. (2019). Bioaugmentation as an associated technology for bioremediation of soil contaminated with sulfentrazone. Ecological Indicators, 99, 343–348. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Chi, X.-Q., Zhang, J.-J., Sun, D.-L., & Zhou, N.-Y. (2014). Bioaugmentation of a methyl parathion contaminated soil with Pseudomonas sp. strain WBC-3. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 87, 116–121. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., He, Z., Liu, Xinxing, Liu, Xueduan, Van Nostrand, J.D., Deng, Y., Wu, L., Zhou, J., & Qiu, G. (2011). GeoChip-Based Analysis of the Functional Gene Diversity and Metabolic Potential of Microbial Communities in Acid Mine Drainage. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 77, 991–999. [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.A., Lopes, P.R.M., Bidoia, E.D., Ferreira, L.C., Montagnolli, R.N., Prado, E.P., & Ferrari, S. (2019). Influence of tebuthiuron and vinasse under soil microbiota activity in sugarcane crop. International Journal of Development Research, 09, 7, 28861-28865.

- Faria, M.A., Lopes, P.R.M., Bidoia, E.D., Ferreira, L.C., Viana, R.S., Prado, E.P., Bonini, C.S.B.B.; & Tomaz, R.S. (2019). Vinasse and tebuthiuron application to sugarcane soil and its effects on bacterial community and ecotoxicity after natural attenuation. International Journal of Development Research, 09, 08, 28898-28904.

Figure 1.

Kinetic development of M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE) as potential phytoremediators of the herbicide tebuthiuron (TBT) in soil with solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants from the Gompertz model. The western and eastern hemispheres represent the different plants, respectively, MP and CE. The northern and southern hemispheres demonstrated the effect of adding inoculants and/or the herbicide tebuthiuron, respectively.

Figure 1.

Kinetic development of M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE) as potential phytoremediators of the herbicide tebuthiuron (TBT) in soil with solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants from the Gompertz model. The western and eastern hemispheres represent the different plants, respectively, MP and CE. The northern and southern hemispheres demonstrated the effect of adding inoculants and/or the herbicide tebuthiuron, respectively.

Figure 2.

Production of dry biomass of M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE) in soil associated or not with tebuthiuron (TBT) and/or solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants after 70 DAS.. Legend: different lowercase letters indicate statistical difference by Tukey test at 5% compared among the same plant species.

Figure 2.

Production of dry biomass of M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE) in soil associated or not with tebuthiuron (TBT) and/or solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants after 70 DAS.. Legend: different lowercase letters indicate statistical difference by Tukey test at 5% compared among the same plant species.

Figure 3.

Kinetic development of C. juncea height as bioindicator species in soil with tebuthiuron (TBT) and solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants from the Gompertz model. Ref - reference control soil without green manure and inoculants.

Figure 3.

Kinetic development of C. juncea height as bioindicator species in soil with tebuthiuron (TBT) and solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants from the Gompertz model. Ref - reference control soil without green manure and inoculants.

Figure 4.

Kinetic development of C. juncea as bioindicator species in soil with tebuthiuron (TBT) and solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants from the Gompertz model.. Legend: The western and eastern hemispheres represent the different plants, respectively M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE). Ref - reference control soil without green manure and inoculants.

Figure 4.

Kinetic development of C. juncea as bioindicator species in soil with tebuthiuron (TBT) and solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants from the Gompertz model.. Legend: The western and eastern hemispheres represent the different plants, respectively M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE). Ref - reference control soil without green manure and inoculants.

Figure 5.

Production of fresh and dry biomass of C. juncea in soil associated or not with tebuthiuron (TBT), solid (Sol), or liquid (Liq) inoculants and/or the different plants M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE) after 70 DAS. Ref - reference control soil without green manure and inoculants.. Legend: different lowercase letters indicate statistical difference by Tukey test at 5% compared among the same plant species.

Figure 5.

Production of fresh and dry biomass of C. juncea in soil associated or not with tebuthiuron (TBT), solid (Sol), or liquid (Liq) inoculants and/or the different plants M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE) after 70 DAS. Ref - reference control soil without green manure and inoculants.. Legend: different lowercase letters indicate statistical difference by Tukey test at 5% compared among the same plant species.

Figure 6.

Kinetic development of the germination index of L. sativa in ecotoxicity bioassays in soil samples with tebuthiuron (TBT) and solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants from the Gompertz model. Ref - reference control soil without green manure and inoculants.

Figure 6.

Kinetic development of the germination index of L. sativa in ecotoxicity bioassays in soil samples with tebuthiuron (TBT) and solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants from the Gompertz model. Ref - reference control soil without green manure and inoculants.

Figure 7.

Kinetic development of the germination index of L. sativa in ecotoxicity bioassays in soil samples with tebuthiuron (TBT) and solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants associated or not with different plants, for both M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis. (CE) from the Gompertz model.. Legend: The western and eastern hemispheres represent the different plants, respectively, M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE). Ref - reference control soil without green manure and inoculants.

Figure 7.

Kinetic development of the germination index of L. sativa in ecotoxicity bioassays in soil samples with tebuthiuron (TBT) and solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants associated or not with different plants, for both M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis. (CE) from the Gompertz model.. Legend: The western and eastern hemispheres represent the different plants, respectively, M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE). Ref - reference control soil without green manure and inoculants.

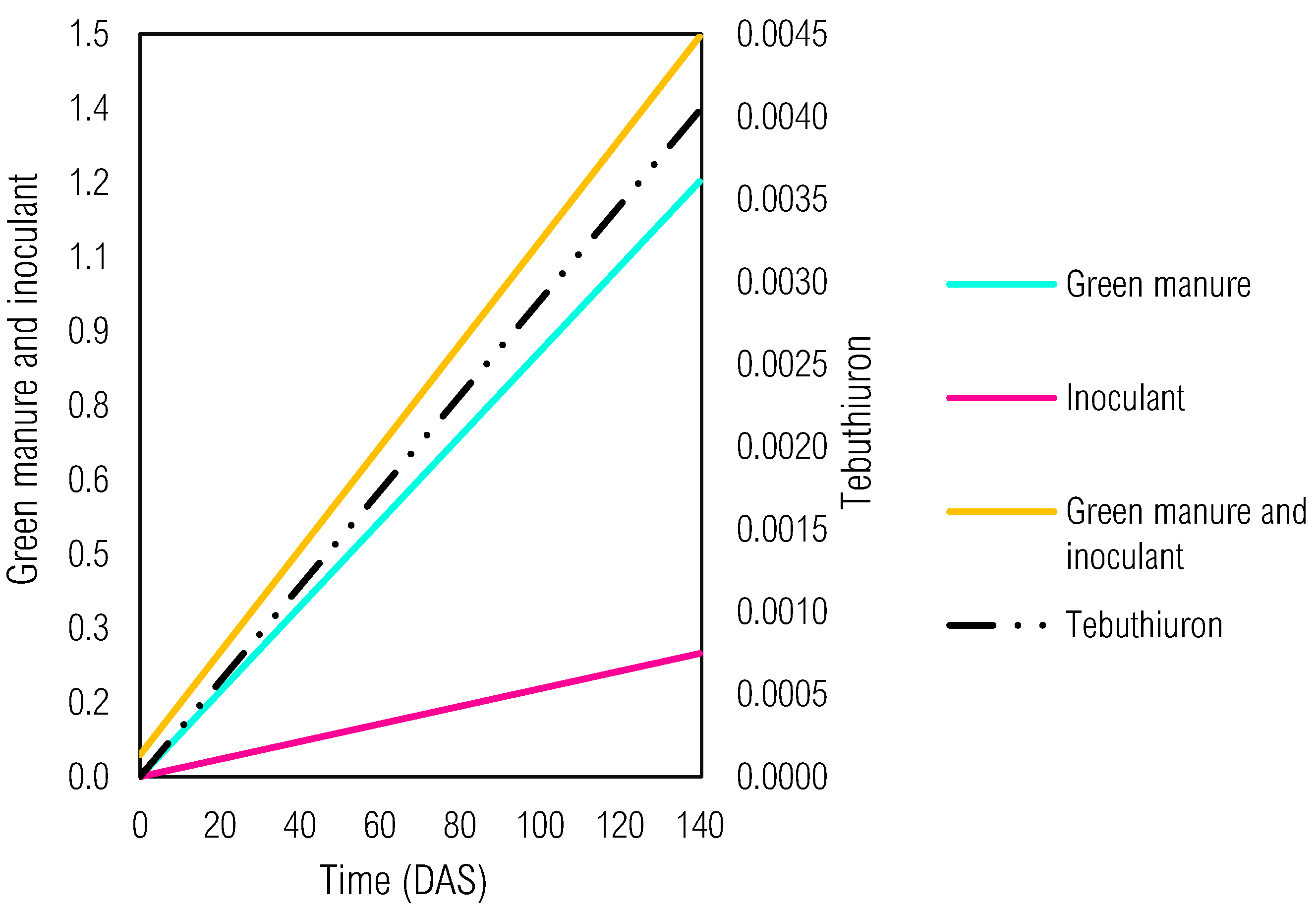

Figure 8.

Dynamics of random (tebuthiuron) and fixed (green manures - M. pruriens and C. ensiformis; and microbial inoculants - liquid and solid) effects on the specific rate of germination index (GI) of L. sativa in ecotoxicity bioassays on soil samples.

Figure 8.

Dynamics of random (tebuthiuron) and fixed (green manures - M. pruriens and C. ensiformis; and microbial inoculants - liquid and solid) effects on the specific rate of germination index (GI) of L. sativa in ecotoxicity bioassays on soil samples.

Table 1.

Soil chemical analysis before and after pre-cultivation of C. ensiformis and M. pruriens.

Table 1.

Soil chemical analysis before and after pre-cultivation of C. ensiformis and M. pruriens.

| Attributes |

Unit |

Before |

After |

Indication |

| pH |

- |

4,0 |

7,5 |

Increased |

| Organic matter |

g dm-3

|

4,0 |

10 |

Increased |

| Potassium |

mmol dm-3

|

0,3 |

1,6 |

Increased |

| Calcium |

6 |

51 |

Increased |

| Magnesium |

2 |

23 |

Increased |

| Hydrogen + Aluminum |

33 |

8 |

Decreased |

| Aluminum3+

|

13 |

0 |

Decreased |

| Phosphor |

mg dm-3

|

1 |

6 |

Increased |

| Sulfur |

7 |

- |

Not detected |

| Boron |

0,10 |

0,02 |

Decreased |

| Copper |

0,1 |

0,2 |

Increased |

| Iron |

4 |

2 |

Decreased |

| Manganese |

1,8 |

1,2 |

Increased |

| Zinc |

0,1 |

0,3 |

Increased |

| Sum-of-bases |

8 |

75,6 |

Increased |

| Cation Exchange Capacity |

41 |

83,6 |

Increased |

| Base saturation |

% |

20 |

90 |

Increased |

| Aluminum saturation |

61 |

0 |

Decreased |

Table 2.

Parameters of Gompertz kinetic models for the height of M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE) as potential phytoremediators of tebuthiuron (TBT) in soil with solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants.

Table 2.

Parameters of Gompertz kinetic models for the height of M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE) as potential phytoremediators of tebuthiuron (TBT) in soil with solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants.

| Treatments |

Complexity |

Adequacy |

| α |

β |

k |

r² |

AIC |

BIC |

| MP |

72,72 |

15,49 |

0,113 |

0,72ns

|

63,96 |

65,17 |

| MP + TBT |

51,69 |

4,76 |

0,109 |

0,94*

|

63,96 |

65,17 |

| MP + Liq |

77,66 |

32,71 |

0,170 |

0,97*

|

69,10 |

70,31 |

| MP + Sol |

80,31 |

38,14 |

0,143 |

0,99**

|

56,33 |

57,54 |

| MP + Liq +TBT |

61,58 |

144,19 |

0,227 |

0,89*

|

78,80 |

80,01 |

| MP + Sol + TBT |

76,63 |

9,15 |

0,100 |

0,93*

|

75,82 |

77,04 |

| CE |

31,64 |

2,72 |

0,075 |

0,97*

|

46,29 |

47,50 |

| CE + TBT |

20,27 |

2,13 |

0,069 |

0,93*

|

44,71 |

45,92 |

| CE + Liq |

43,10 |

2,73 |

0,075 |

0,97*

|

53,67 |

54,88 |

| CE + Sol |

40,90 |

2,62 |

0,068 |

0,97*

|

50,41 |

51,62 |

| CE + Liq + TBT |

34,26 |

2,51 |

0,071 |

0,96*

|

49,03 |

50,24 |

| CE + Sol + TBT |

84,52 |

2,81 |

0,022 |

0,94*

|

60,08 |

61,29 |

Table 3.

Parameters of the Gompertz kinematic models for the height of C. juncea as bioindicator species in tebuthiuron (TBT) soil with M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE) and liquid (Liq) or solid (Sol) inoculants.

Table 3.

Parameters of the Gompertz kinematic models for the height of C. juncea as bioindicator species in tebuthiuron (TBT) soil with M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE) and liquid (Liq) or solid (Sol) inoculants.

| Treatments |

Complexity |

Adequacy |

| α |

β |

k |

r² |

AIC |

BIC |

| MP |

156,35 |

5,94 |

0,0106 |

0,98** |

49,51 |

50,30 |

| MP + TBT |

86,91 |

3,29 |

0,0330 |

0,98** |

45,17 |

45,96 |

| MP + Liq |

181,96 |

3,76 |

0,0174 |

0,98** |

45,39 |

46,18 |

| MP + Sol |

42,01 |

3,23 |

0,0529 |

0,98** |

41,15 |

41,94 |

| MP + Liq +TBT |

147,18 |

3,75 |

0,0202 |

0,99** |

41,67 |

42,46 |

| MP + Sol + TBT |

248,45 |

8,52 |

0,0659 |

0,98** |

54,98 |

55,77 |

| CE |

178,13 |

3,82 |

0,0149 |

0,96* |

47,42 |

48,20 |

| CE + TBT |

115,67 |

3,34 |

0,0214 |

0,98** |

46,18 |

45,39 |

| CE + Liq |

78,74 |

3,00 |

0,0250 |

0,97* |

45,81 |

45,02 |

| CE + Sol |

66,01 |

2,91 |

0,0267 |

0,96* |

47,20 |

47,98 |

| CE + Liq + TBT |

115,76 |

5,60 |

0,0930 |

0,97* |

47,70 |

48,49 |

| CE + Sol + TBT |

199,88 |

4,11 |

0,0160 |

0,98** |

43,88 |

44,67 |

| Ref |

172,93 |

3,78 |

0,0190 |

0,98** |

44,72 |

45,51 |

| Liq |

324,99 |

8,91 |

0,0582 |

0,98** |

51,98 |

52,77 |

| Sol |

69,95 |

2,95 |

0,0302 |

0,97* |

48,00 |

47,21 |

| TBT |

127,47 |

5,76 |

0,0115 |

0,99** |

44,82 |

45,61 |

| Liq + TBT |

70,50 |

3,08 |

0,0299 |

0,98** |

42,20 |

42,99 |

| Sol + TBT |

163,15 |

3,47 |

0,0173 |

0,97* |

50,26 |

51,05 |

Table 4.

Parameters of the Gompertz kinetic models for the germination index of L. sativa in ecotoxicity bioassays in soil samples with tebuthiuron (TBT) and solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants associated or not with different plants for both M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE).

Table 4.

Parameters of the Gompertz kinetic models for the germination index of L. sativa in ecotoxicity bioassays in soil samples with tebuthiuron (TBT) and solid (Sol) or liquid (Liq) inoculants associated or not with different plants for both M. pruriens (MP) and C. ensiformis (CE).

| Treatments |

Complexity |

Adequacy |

| α |

β |

k |

r² |

AIC |

BIC |

| MP |

0,99 |

6,98 |

0,0477 |

0,98** |

-11,64 |

-12,47 |

| MP + TBT |

0,97 |

10,09 |

0,0632 |

0,98** |

-13,20 |

-14,04 |

| MP + Liq |

0,99 |

7,06 |

0,0466 |

0,98** |

-13,15 |

-13,99 |

| MP + Sol |

0,97 |

10,09 |

0,0632 |

0,98** |

-13,20 |

-14,04 |

| MP + Liq +TBT |

0,99 |

6,81 |

0,0462 |

0,98** |

-11,94 |

-12,77 |

| MP + Sol + TBT |

0,99 |

7,49 |

0,0509 |

0,98** |

-11,67 |

-12,51 |

| CE |

0,98 |

5,94 |

0,0400 |

0,98** |

-11,13 |

-11,97 |

| CE + TBT |

0,97 |

7,25 |

0,0386 |

0,99** |

-21,18 |

-22,02 |

| CE + Liq |

0,99 |

6,96 |

0,0486 |

0,98** |

-10,72 |

-11,56 |

| CE + Sol |

0,99 |

7,03 |

0,0488 |

0,98** |

-10,94 |

-11,77 |

| CE + Liq + TBT |

0,98 |

6,46 |

0,0422 |

0,98** |

-12,94 |

-13,77 |

| CE + Sol + TBT |

0,99 |

7,06 |

0,0480 |

0,98** |

-11,94 |

-12,77 |

| Ref |

0,92 |

3,27 |

0,0264 |

0,99** |

-19,10 |

-19,93 |

| Liq |

0,95 |

3,65 |

0,0305 |

0,99** |

-24,09 |

-24,92 |

| Sol |

0,89 |

2,84 |

0,0225 |

0,96* |

-8,90 |

-9,73 |

| TBT |

0,96 |

3,01 |

0,0314 |

0,99** |

-15,20 |

-16,03 |

| Liq + TBT |

0,98 |

3,28 |

0,0350 |

0,99** |

-18,46 |

-19,29 |

| Sol + TBT |

0,92 |

3,33 |

0,0264 |

0,99** |

-19,68 |

-20,51 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).