1. Introduction

A key driver for sustainable development is a future in which every African can enjoy a life of better health and well-being. Africa is currently the world’s second- largest and second- most populous continent, with the fastest-growing population globally. Its population of 1.4 billion has an average age of 18.8 years, making it the youngest of any continent [

1]. Sub-Saharan Africa faces considerable educational and financial challenges, with the highest illiteracy rate in the world [

1] and a large proportion of people living in extreme poverty. These social determinants of health, combined with the diverse environmental and political conditions, as well as the great diversity of ethnicities, cultures, languages and historical developments, present both richness and challenges for each African country including for the health status and health systems. Moreover, African countries face a double burden of persistently high infectious diseases and increasingly prevalent chronic diseases [

2]. Nonetheless, African nations have also made remarkable strides in enhancing the health outcomes of their populations in recent decades [

3]. The Africa health landscape is rapidly evolving, with better control of communicable diseases and rising prevalences of non-communicable diseases, specifically diabetes and cancer.

It is crucial to continue concerted action in Africa to curb the spread of infectious diseases, while also facilitating appropriate management of chronic conditions and general disease prevention and health promotion to support healthier populations [

4]. According to the Nairobi Declaration on Health Promotion [

5] investment in health literacy is key in this process.

1.1. Health Literacy

The concept of health literacy has received considerable attention in the past decades [

6]. As the knowledge and competencies necessary to use health information and services [

7], promoting health literacy has become an incremental component of many global and national health plans e.g. the Shanghai Declaration on promoting health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

8] or the national health literacy action plans of China [

9], Germany [

10], Scotland[

11], and United States[

12] as an enabler of sustainable development, vital for good health and well-being, disease prevention and achieving universal health coverage [

7,

13]. Health literacy is considered a relational, modifiable determinant of health that focuses on the skills of individuals and communities and the health literacy responsiveness of service providers and systems to maintain and promote health and well-being [

14]. It can be defined as multidimensional concept that includes the knowledge, motivation, and competencies for people to access, understand, appraise, and apply information to form judgments and make decisions concerning health care, disease prevention, and health promotion in everyday life to maintain and improve quality of life throughout the life course [

6]. Importantly, it also emphasizes how health providers, organizations, and settings enable people to cope with health challenges [

15].

1.2. Health Literacy in Africa

Although, several reports have sketched the international progress of health literacy as a growing global movement [

16,

17,

18] they only included few references from African countries and did not provide a comprehensive overview of health literacy endeavors across the African continent. Thus, to date, there are limited insights about how health literacy is being researched, developed and implemented in the diverse African societies. Nonetheless, to improve health literacy in Africa, it is crucial to understand and address the advancements based on the distinctive African contexts [

19,

20].

1.3. Study Aim

Therefore, to bridge the gap, this study aimed to shed light on the scope and scale of health literacy development in Africa by providing a first overview of the state of the art. The study included a scoping review of health literacy research focusing on 1) research approaches, 2) historical trends, 3) geographical origins, 4) target groups and settings, and 5) thematic analysis of specified health literacy aspects. The insights gained may help to inform further progress and prioritize future actions for capacity building, policy development, and informing practices on health literacy for all in Africa.

2. Materials and Methods

The study design followed Arksey and O’Malley steps for scoping reviews [

21] and adhered to the PRISMA Guidelines for Scoping Reviews, which allow for the systematic and transparent data identification, selection, synthesis, and appraisal of research-related literature [

21]. The search strategy employed a comprehensive and systematic approach to identify scientific evidence from publications that could potentially inform trends in health literacy in Africa. Thus, the systematic literature search was conducted in six online scientific databases: PubMed, PsycInfo, Cochrane Library, ERIC, African Journals Online and African Index Medicus. The search string used the PCC approach covering participants, content and context as suggested by the Johanna Briggs Institute [

22]. Thus, the search terms entailed the concept “health literacy” OR “littératie en santé” OR “compétence en matière de santé”, combined with the Boolean operator AND with the search terms for context and population “Afric*” OR “Afriq*” OR all of the names of the 54 African countries of the African Union and their associated adjectives, but NOT “African American*”. The truncation symbol was used to increase the search’s sensitivity and include additional terms, such as African countries or the African continent. Please refer to

Appendix A for the search strategy.

The search was not restricted to a specific time period. Articles were included which were published in English or French language and utilized the term ‘health literacy’ in the title or abstract and had full-text available online (either through open access or university access). The exclusion criteria comprised studies conducted in African regions with only limited or no international recognition, such as Somaliland and Western Sahara. Additionally, studies conducted outside of Africa, including those focusing on African Americans in the United States of America or African migrants in Europe, were excluded.

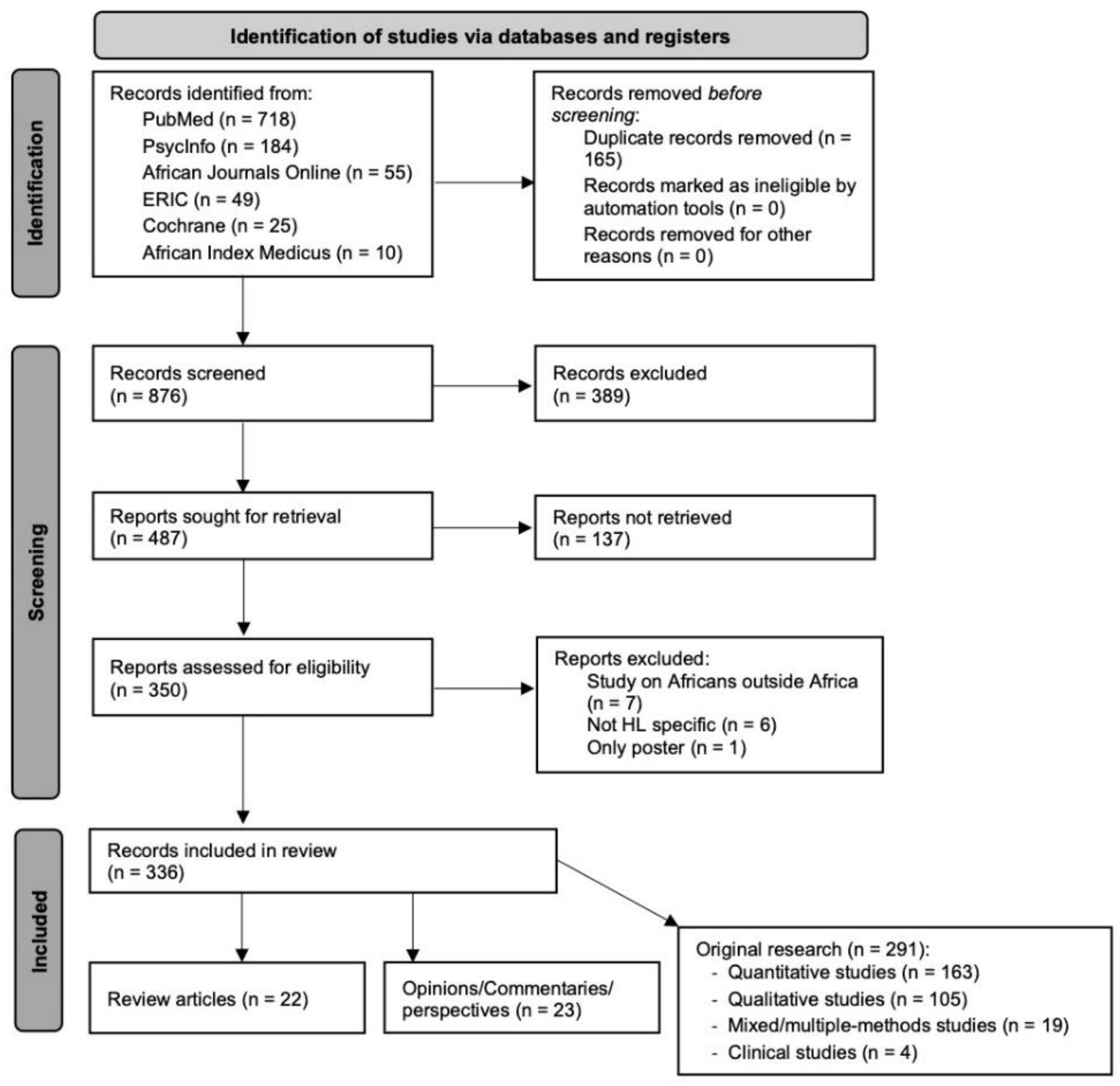

The literature search and data collection took place in July 2022 and resulted in 876 publications. The titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility. The screening process, outlined in the PRISMA flowchart (

Figure 1), resulted in 487 publications, of which 137 were excluded due to inaccessibility of the full text and 13 due to unavailability of official results or inappropriateness for the purpose of the study. Finally, 336 articles were included in the review of health literacy development in Africa. The complete list of articles can be found in

Appendix B.

The lead authors KS, SH, and VK reviewed the research literature based on the pre-defined inclusion criteria. They coded the data in Excel using a jointly developed coding scheme that reflected the research objectives. Collaboratively, they analyzed and synthesized the findings corresponding to the study objectives. Key informants from the African Health Literacy Network, provided thorough feedback on the research design, process and findings and contributed as co-authors to the discussion of the findings, and recommendations.

3. Results

The scoping review and synthesis according to research methods, countries, populations, settings and health literacy factors revealed new insights on the scope and scale of health literacy development in Africa.

3.1. Research Approaches Applied

Out of the 336 articles, 22 were scoping literature reviews, 291 were original research articles, and 23 were opinions, perspectives, commentaries published in scientific journals or academic books. Among the original research articles, 163 publications presented quantitative methods, mostly using cross-sectional designs to assess health literacy or disease-related health literacy in patients. Other articles assessed, for example, the effectiveness of controlled trials and interventions. One hundred and five articles used qualitative approaches, with the majority using semi-structured interviews or focus group discussions to investigate barriers to health care or appropriate health behaviors. Finally, 19 publications presented mixed or multi-method approaches, such as developing or translating health literacy measures or assessing perceptions and health behaviors related to a specific health concern, and four described clinical trials.

3.2. Publication History of African Health Literacy Research

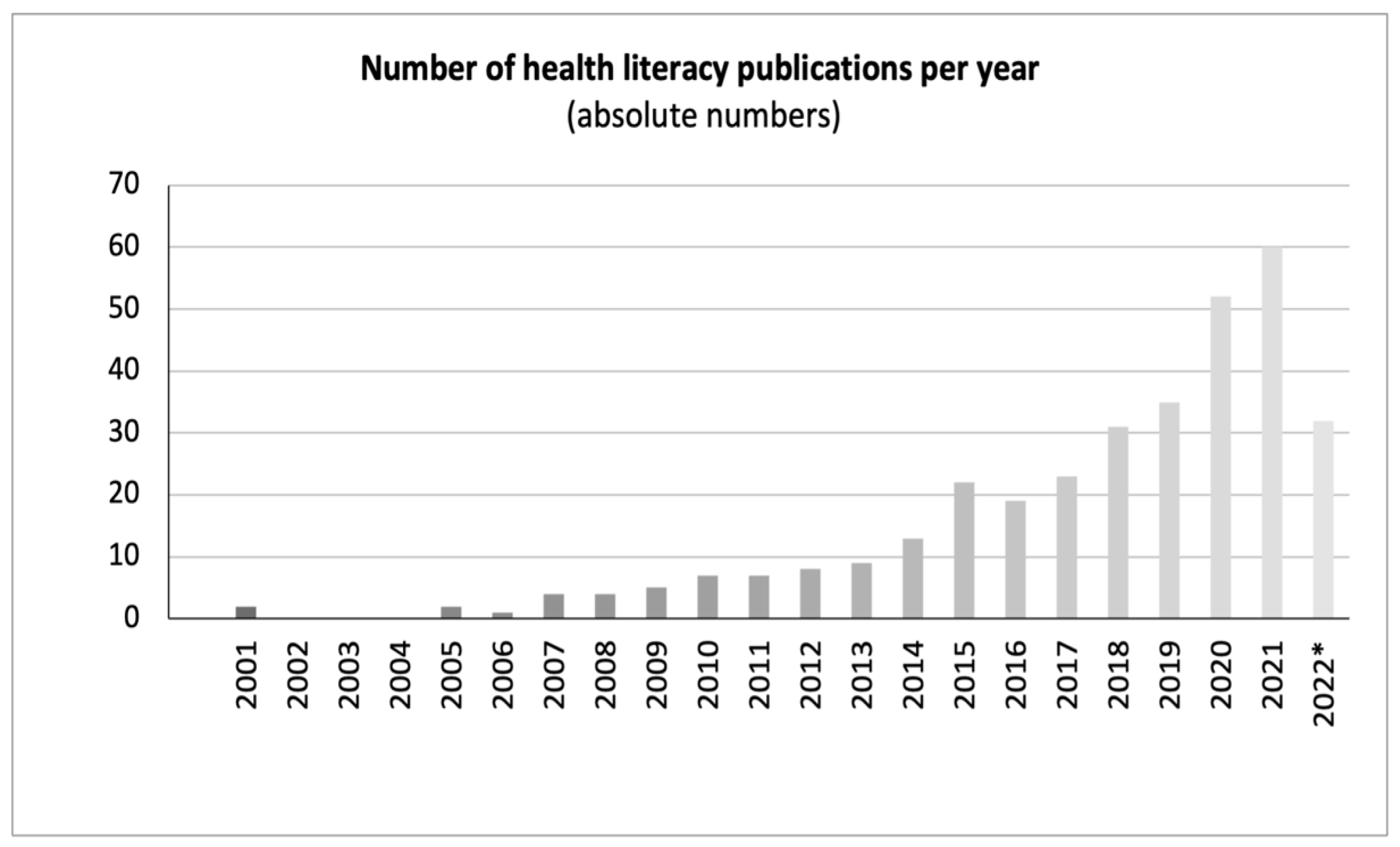

Scientific publications on health literacy in Africa have increased exponentially since the beginning of the twenty-first century, as shown in

Figure 2. The first mention of health literacy in Africa was in Kickbusch's seminal paper "Addressing the health and education divide" [

23], which provided several examples. The first specific study on health literacy was published in 2005, focusing on HIV-related health literacy in Zambia. Since then, the number of annual publications steadily increased, reaching 60 publications in 2021 and likely more in the pipeline the following years.

3.3. Geographical Distribution

The geographical analysis revealed that health literacy publications were available from 38 of the 54 African Union countries (

Figure 3). Most studies were conducted in South Africa (n=84), followed by Nigeria (n=49), Ghana (n=30), Ethiopia (n=28), and Uganda (n=27). Many countries had only one or a few studies on health literacy, such as Burundi (n=1) or Sudan (n=1). Additionally, 31 publications concentrated on various regions such as West Africa (n=2), North Africa (n=1), Southern Africa (n=2), and East Africa (n=1). Ten publications specifically targeted sub-Saharan Africa, while one study focused on rural Africa. Thirteen publications discussed Africa in general without specifying a country or distinct region. The publications based on general and regional accounts are not displayed in

Figure 3, which only presents the country-specific studies.

For a detailed summary of the health literacy content available in each country, see

Appendix C.

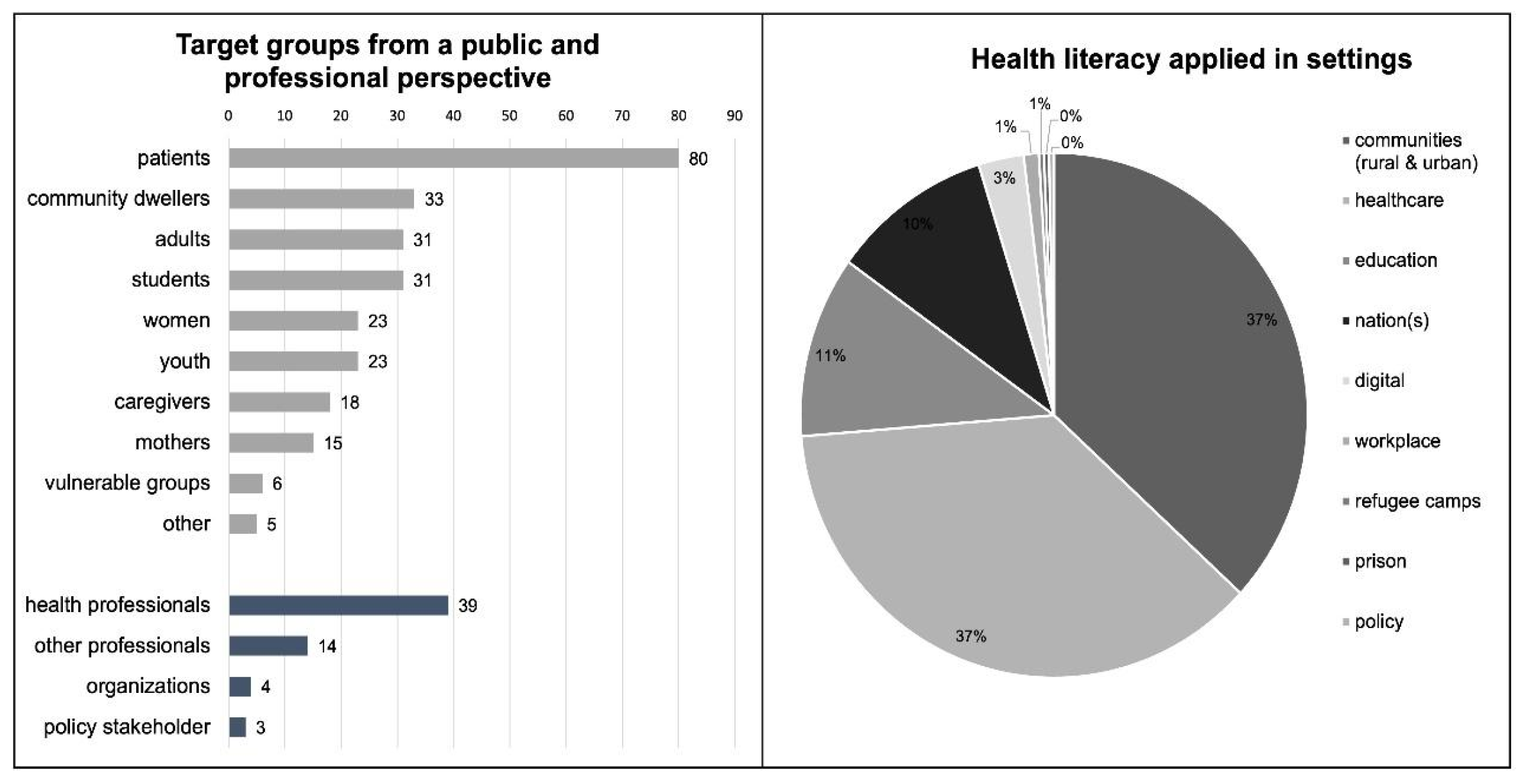

3.4. Analysis of Target Groups and Settings

The analysis of target groups distinguished between population-based and professional stakeholder-related studies (

Figure 4). The population-based studies focused on the public or subgroups of the public, while the studies focusing on the professional perspective encompassed actors in the workforce (health professionals and other relevant stakeholders), organizations, systems, or the policy arena.

Figure 4 does not include the 24 publications where it was not possible to specify a target group in their research which was the case in some commentaries or policy papers.

The largest proportion of stakeholders among all studies were patients (n=80). Other subgroups included community dwellers (n=33), adults (n=31), students (n=31), women (n=23), adolescents (n=23), followed by caregivers (n=18), and mothers (n=15). Finally, high-risk groups, such as migrants, prisoners, the elderly, and indigenous populations, represented only 2% (n=6), and several single studies focused on men (n=1), consumers (n=1), employees (n=1), or several target groups (n=2), which were grouped under “other” (n=5).

Target groups associated with the healthcare workforce form the largest proportion (n=39). Other professionals include professions outside the health sector (n=14). A limited number of publications focused on organizations (n=4) and NGOs or policy stakeholders (n=3).

According to WHO [

24], a setting for health refers to a place or social context where individuals engage in daily activities, and where environmental, organizational, and personal factors interact to influence health and well-being. The findings revealed that the most common settings studies were the community and the health care settings, followed by educational settings such as secondary school or high school. As shown in

Figure 4, fewer studies were designated in digital/online settings, workplaces, or rural/urban settings.

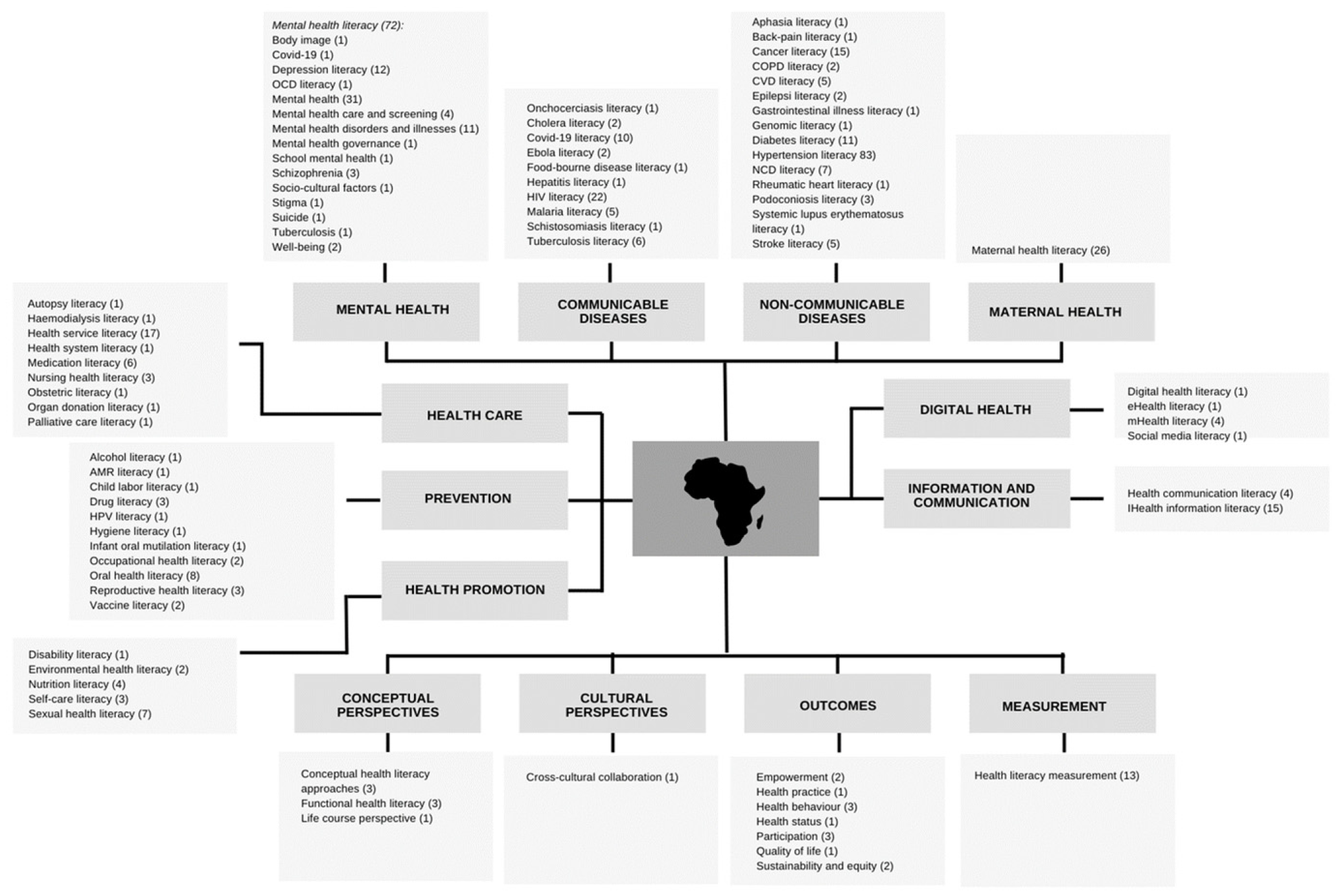

3.5. Thematic Analysis of Health Literacy in Africa

The thematic analysis identified four general trends covering 14 themes based on the types of health literacy categorized in the data, as illustrated in

Figure 5. The trends and themes are summarized in

Figure 5 and briefly described in the text with keywords and number of papers identified for each theme. It is beyond the scope of this article to provide a more detailed description based on all of the references. Instead, for the sake of transparency, the general data set is provided in

Appendix B.

Firstly, there was a

disease-oriented focus concentrating on mental health, communicable diseases and non-communicable diseases. Moreover, maternal health was a priority focus, given the high levels of child morbidity and mortality in many African countries [

25].

Mental health literacy included 72 references related to a wide variety of themes including body image, covid-19 and tuberculosis, suicide and depression literacy, OCD literacy, mental health literacy in general, mental health care and screening, mental disorders and illnesses, for instance schizophrenia, mental health governance, school mental health, socio-cultural factors, stigma, and promotion of well-being. The publications presented and discussed facets such as knowledge and capacity building, explanatory models, attitudes, impact of media, prevention and treatment, management and policy.

Communicable diseases included 55 references describing health literacy in a wide range of diseases such as HIV/AIDS, Covid-19, tuberculosis, malaria, Ebola, onchocerciasis, cholera, hepatitis, schistosomiasis, as well as food-borne diseases.

Noncommunicable diseases entailed 59 references describing NCD literacy in general and in relation to specific conditions such as aphasia, back pain, cancer, COPD, CVD, epilepsy, gastrointestinal diseases, diabetes, hypertension, rheumatic heart disease, podoconiosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and stroke.

Maternal health literacy covered 26 references related to family planning, reproductive health, healthy pregnancy, antenatal and postnatal care, neonatal jaundice, infant survival practices, and childcare by parents and other caregivers.

Secondly, a trend focused on organizational and systemic aspects of health literacy in the domains of health systems, health care, prevention, and health promotion.

- 5.

Health system entailed 21 references regarding health service literacy, health system literacy and nursing literacy.

- 6.

Healthcare included 11 references to health system issues such as treatment and medication literacy. Some specific features were identified, such as autopsy literacy, hemodialysis literacy, obstetric literacy, organ donation literacy, palliative care literacy, and genomic literacy.

- 7.

Prevention covered 24 references associated with reproductive health literacy, HIV/AIDS literacy and sexual health, and vaccine literacy related to COVID-19 and HPV. The theme also included alcohol and drug literacy as well as oral health literacy, hygiene, and antimicrobial resistance literacy. In addition, occupational health literacy and health literacy in relation to child labor were included.

- 8.

Health promotion included 17 references focusing broadly on health literacy-related health promotion strategies such as sexual health literacy, nutrition literacy, disability literacy, and self-care literacy, as well as environmental health literacy.

Thirdly, there was a clear focus on communication and information, particularly in relation to digital health.

- 9.

Information and communication health literacy was based on 19 references and focused on awareness, seeking and accessing information, and improving communication between, e.g., patients and healthcare providers.

- 10.

Digital health literacy concerned seven studies and discussions on the use of eHealth literacy, mHealth literacy, social media, and other forms of technology and innovation.

Lastly, there was a conceptual focus on concepts and cultural perspectives as well as outcomes and general measurement in relation to health literacy.

- 11.

Conceptual perspectives referred to seven reflections on concepts and approaches related to health literacy, for instance, functional health literacy and the life course perspective.

- 12.

Cultural perspectives included one study that highlighted the importance of cross-cultural understanding and collaboration.

- 13.

Outcomes of health literacy were based on 13 references highlighting outcomes such as health behavior and practices, health status, participation and empowerment, quality of life, sustainability, and equity.

- 14.

Measurement included 13 references emphasizing the wide range of tools, methods, and approaches used to assess the prevalence of health literacy or as an outcome of interventions. Tools included, for example, REALM-R, HLS-EU, HLQ, and the Mental Health Literacy Survey.

4. Discussion

This comprehensive scientific review provides a novel overview of the scope and scale of health literacy developments in Africa. By incorporating global and African-specific scientific databases, the literature search was rigorously conducted and provided ample evidence that health literacy is an emerging feature of interest on the African continent. The large number of 876 publications covering health literacy, of which 336 publications were included, demonstrates its importance for research, policy, and practice in Africa.

According to the study, the global community vested in health literacy, health promotion and global health has a unique opportunity to learn successful approaches, particularly in adapting questionnaires and interventions to linguistic and cultural contexts from the African community. Over half of the research made use of quantitative approaches illustrating validation and measurement studies are common in Africa like in other parts of the world [

26,

27]. While no in-depth analysis of definitions was conducted, the general review of literature revealed that the use of health literacy definitions referred to the most widely used in research [

6].

Although health literacy in Africa was briefly explored since 2001, a major shift in research development can be detected since 2017 where the research publications significantly increased. This trend is similar to the global trend, albeit on a smaller scale [

18].

Across the African Union, South Africa, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Uganda lead the research development on health literacy. It is worth noting that these countries consist of comparatively large populations and with established university collaborations with other nations outside Africa. Interestingly, most publications originated from English-speaking countries, with limited contributions from French- or Portuguese-speaking countries. The research and publication opportunities within and between countries may be affected by a lack of funding or language barriers for non-native English speakers in relation to publishing [

28].

The analysis of target groups indicated a greater emphasis on individual health literacy rather than on the organizational health literacy perspectives. This finding is consistent with global developments. This might be grounded in the historical evolvement of the concept which primarily focused on individual health literacy before embracing organizational health literacy responsiveness [

6,

29].

In contrast to health literacy research in other world regions, the settings analysis highlighted the interesting feature that health literacy is promoted more extensively in communities and settings outside the health sector. Studies in Europe and North America often focus on clinical settings [

30,

31]. The findings can be partly explained by the health challenges prevalent in certain areas of Africa, where access to health services is limited, universal health care is scarce, and health system literacy is often low [

32]. Consequently, interventions located in the community might be more appropriate and many African countries are more familiar with it, as they resemble the many interventions aimed at preventing infectious diseases such as malaria or HIV [

33,

34]..

The thematic analysis emphasized the specific health challenges facing Africa. Firstly, with regard to communicable diseases, health literacy was widely associated with communicable diseases, predominantly in the African region, such as Ebola, HIV/AIDS, and malaria [

35]. Moreover, the emphasis on maternal health is due to the heightened risk of morbidity and mortality within childhood (under 5 mortality) [

25]. The study suggests that mental health literacy remains a challenge due to insufficient knowledge and awareness, stigma, and prejudice, which is consistent with other research [

36]. The widespread focus on non-communicable diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases reflects the projected increase in global burden [

37]. Secondly, health information and communication remain an important avenue for raising awareness, especially through digital health literacy such as mHealth literacy, which appears to be a promising strategy given the increased access to mobile coverage [

38]. These findings align with global trends and policies [

39]. Thirdly, a cross-cutting topic was sexual and reproductive health literacy related to family planning, which remains a challenge in the world’s youngest population [

40]. Fourthly, the topical analysis highlighted efforts to bend the curves of limited health literacy regarding health systems and organizations, health care, disease prevention, and health promotion to improve outcomes. This is a universal challenge that is prevalent around the globe [

16]. Finally, the discussion of conceptual approaches, measurements, and ways to address cultural change was dominated by the academic perspectives, in line with international research developments [

15].

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

Despite the rigorous study design, some limitations remained. Data search and collection focused on countries officially recognized as members of the African Union, which excluded countries and territories such as Somaliland and Western Sahara. This study used official national borders to categorize different regions, acknowledging that these borders do not always reflect the reality of ethnic groups that are found on both sides of national borders. Given the vast diversity of ethnic groups across the African continent, including their linguistic, cultural, geographical, and often socio-economic particularities, it is crucial to account for these factors when designing future studies.

The data collection was based on six international and Africa-focused databases. While this may not be an exhaustive list of all health literacy publications, the Africa-specific databases clearly yielded studies that would not have been found elsewhere. Scanning the gray literature was beyond the scope of the study but all types of resources identified in the databases were included based on the inclusion criteria, not just the research publications. The study was based on publications in English and French, which may have neglected publications in other major languages spoken in Africa, such as Portuguese, Swahili, or Afrikaans. The aim of this review was to analysis publications using the term ‘health literacy’, so other studies that indirectly address ‘health literacy’ without mentioning the concept were not included. This review presents the general results of a broad trend analysis of health literacy publications in Africa. However, an in-depth meta-analysis of research articles or policy recommendations was beyond the scope of this review, although the data were available. Further research and publications are warranted to fill these gaps.

4.2. Implications for the Future

Reviewing the developments of health literacy in Africa sparks food for thought. Improving health literacy in Africa requires a multifaceted approach involving policy integration, education system enhancement, community engagement, technological innovation, health system improvements, research, and partnerships. It is paramount to create more visibility regarding the need for health literacy and good practice interventions and their importance in improving health outcomes and the quality of health services. By addressing these areas, African countries can empower their populations to make informed health decisions, ultimately improving health outcomes and reducing health disparities across the continent.

The study highlighted the importance of contextualizing health literacy with respect to African society, culture and traditions. As was highlighted by a co-author, health literacy is often portrayed in the scientific discourse and when searching Google is mostly related to Western societies, e.g., with an image of a person sitting in front of a computer navigating for health information or discussing and negotiating treatment options with a physician. These situations may not be appropriate in many African settings, where large portions of the population are rural dwellers, have limited access to digitalization, and often low functional literacy. Thus, the strategies, tools, and approaches for health literacy should be tailored to local opportunities and needs, for example, by translating and validating tools for health literacy assessments, using social mobilization, community dialogue, and engaging local religious and community leaders to provide information about health and available health services. Drawing on local wisdom and strategies of co-design and participation is recommended to define and conceptualize health literacy for each unique African context [

41]. This can be done in collaboration with health literacy practitioners in the specific community, district, region or country with the aim of making it a priority agenda for professionals and policymakers through advocacy using multiple platforms. Health literacy initiatives can tackle social norms through proven interventions, including stakeholder engagement and community dialogue. Harmful practices adversely affect the groups most at risk. Given the degree of vulnerability among the general population, efforts to engage the most vulnerable are often deprioritized to maximize scarce resources.

In Africa, where health challenges are significant and resources are often limited, enhancing health literacy can play a transformative role. Similarly to trends in other world regions, health literacy should be a core component of national health policies and strategies. Governments should recognize it as a critical determinant of health and integrate it into treatment pathways, health promotion and disease prevention programs. This includes developing resources and providing ongoing professional development opportunities for health professionals, teachers and community workers and leaders alike. As the study shows, it is important to collaborate with community leaders, religious figures, and traditional healers to promote health literacy. These trusted figures can help disseminate health information and encourage positive health behaviors. Use of health literacy champions may pave the way for better implementation of health literacy [

42].

Local and international investment and networking are needed for further research, better interventions, and policy development to advance health literacy in Africa. For example, health literacy strategies can be included in the health sector development plans of each African country. Investments in more health literacy interventions can benefit both populations and systems specifically if cultural sensitivity is considered when developing and implementing the interventions. The African Health Literacy Network is a crucial player in strengthening collaboration and further dissemination of the health literacy agenda to build the capacity of people, professionals, and societies in the African region. It was launched in 2017 and has grown to cover membership from 25 countries. It hosted its first pan-African conference in August 2023.

Establish mechanisms to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of health literacy programs in Africa. This includes conducting research to identify best practices and areas for improvement. The lessons learned from this study revealed that measurement and evaluation of health literacy takes place and can be amplified more progressively. Collecting data on health literacy levels across different regions and demographic groups to inform policy decisions and tailor interventions accordingly will improve the quality of implementation.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this review of health literacy trends in Africa underscores the call for action to develop the field of health literacy in ways that are responsive to the needs and concerns of African countries and contexts, rather than copying what has already been done elsewhere without much adaptation. As public health services are currently being strengthened and expanded in many African countries [

40], the valuable lessons learned from this study can be incorporated from the outset, particularly with regard to building systemic health literacy capacity [

43] and incorporating health literacy practices as part of community development.

Building on the widespread legacy of health education and community development in the African region, new approaches applied through a health literacy lens can help to target populations in vulnerable situations and make services more fit for purpose. Proposed solutions include co-designed, targeted programs and interventions for specific populations, as well as capacity building of the workforce and investment in education policies. Particular attention should be paid to ensure cultural appropriateness and adaptation to the needs and perceptions of the populations, especially women and high-risk groups, to leave no one behind.

Strengthening health literacy in Africa is essential to building a future where every African can enjoy a life of better health and well-being. Importantly, this trend analysis highlights that and how health literacy development is on the rise and is promisingly being recognized as a positive key driver of change across the African continent.