Submitted:

09 September 2024

Posted:

10 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

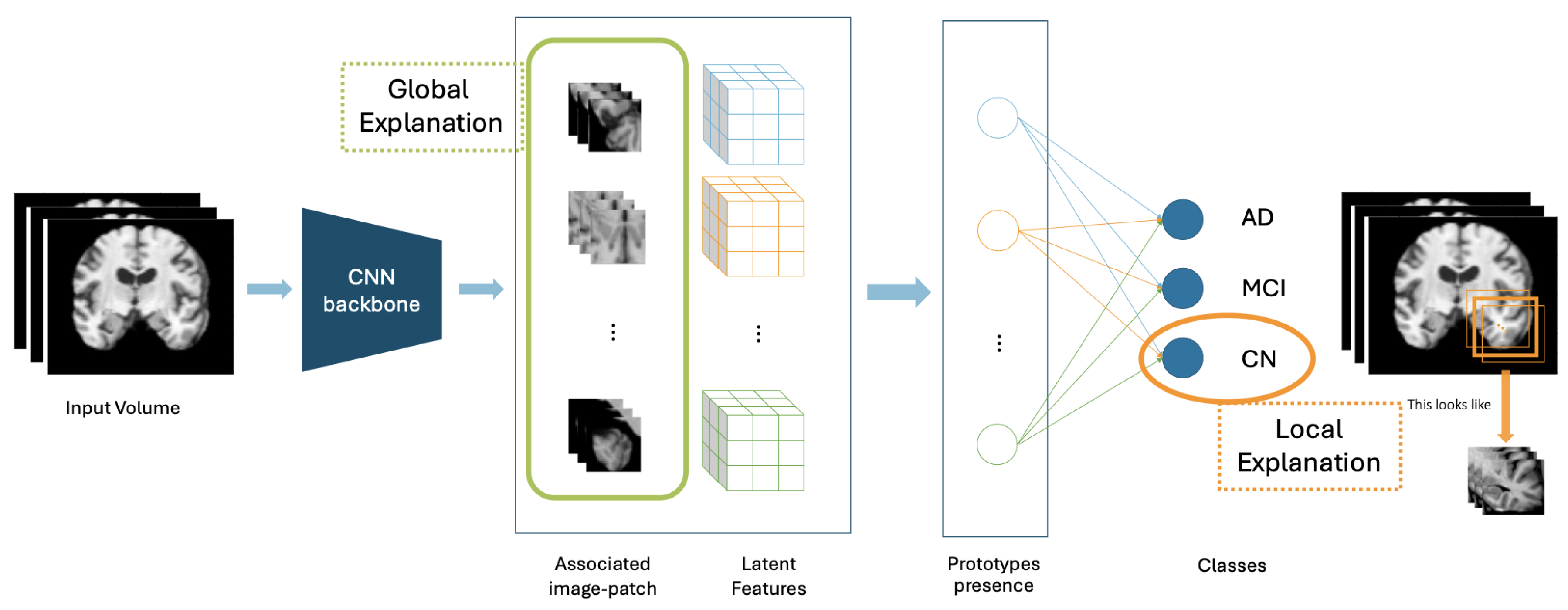

2. Baseline Prototypical-Part Models

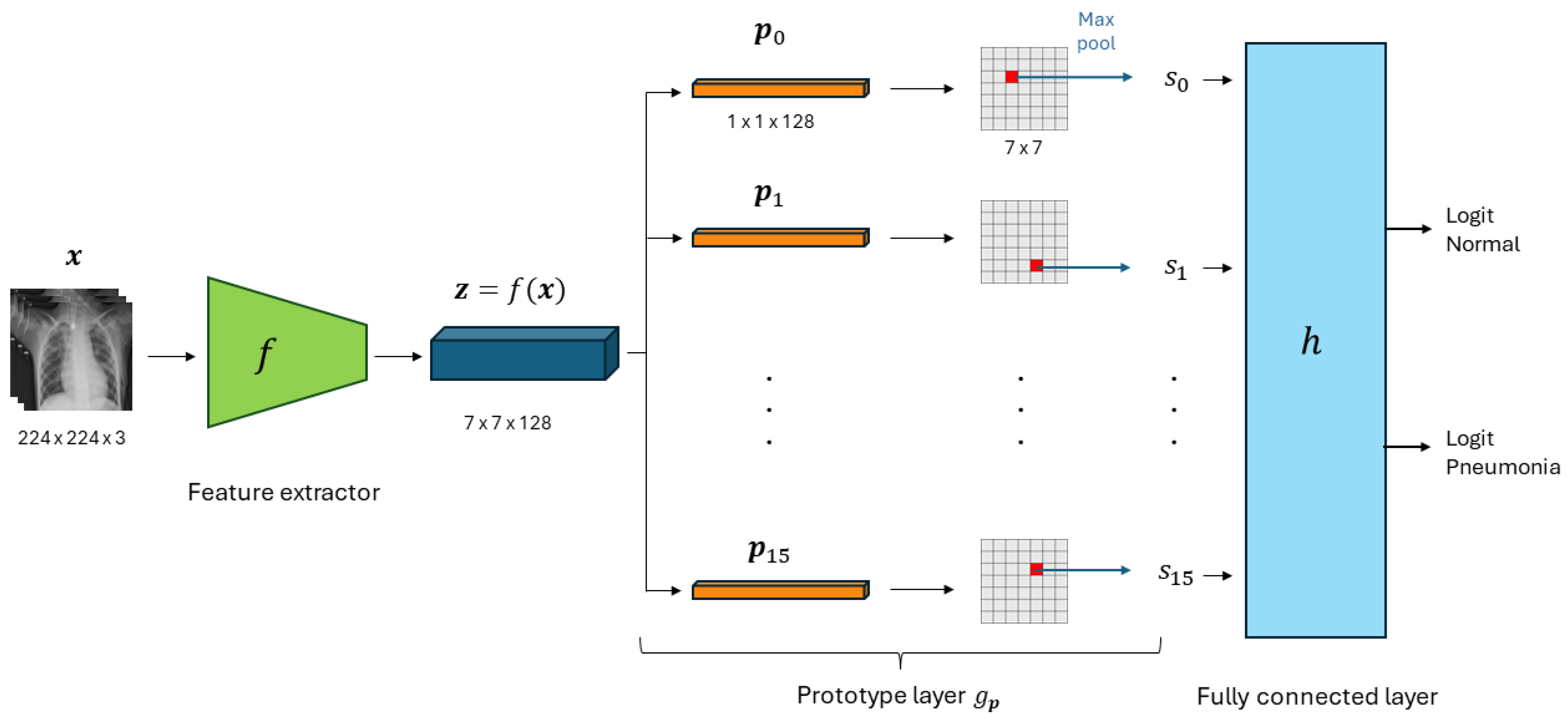

2.1. Prototypical Part Network (ProtoPNet)

2.1.1. Architecture

2.1.2. Training

- Cross entropy loss, penalizes misclassification on the training data.

- Cluster cost, promotes every training image to have some latent patch that is close to at least one prototype of its own class.

- Separation cost, promotes every latent patch of a training image to stay away from the prototypes not of its class.

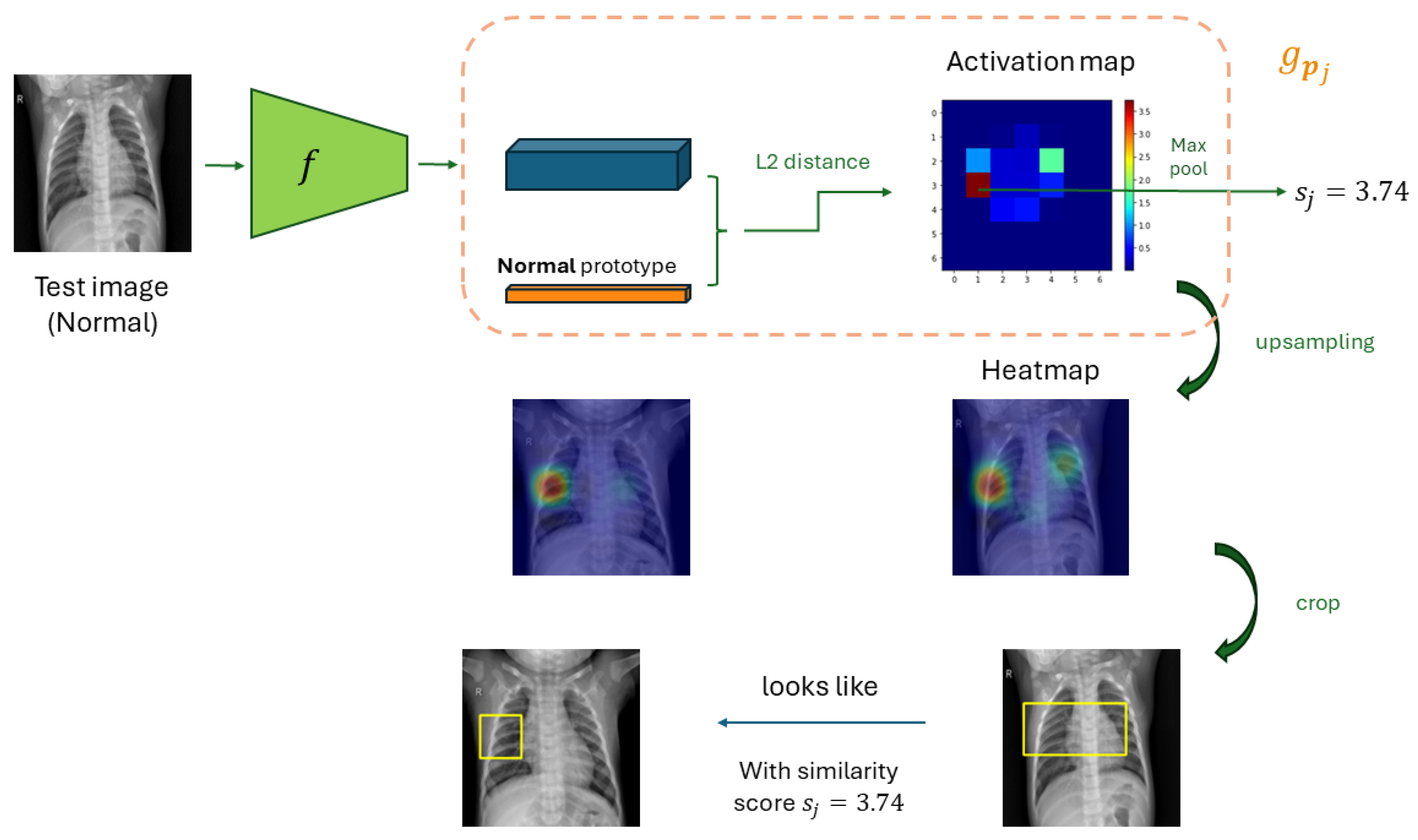

2.1.3. Prototypes’ visualization

- Forwarding through a ProtoPNet to produce the activation map associated with the prototypes

- Upsampling the activation map to the dimension of the input image

- Localizing the smallest rectangular patch whose corresponding activation is at least as large as the 95th-percentile of all activation values in that same map

2.2. XProtoNet

2.2.1. Architecture

2.2.2. Training

-

Classification weighted loss, to address the imbalance in the dataset:Where is the prediction score of the th sample , is a parameter for class balance, and the number of negative and positive labels on disease c, and the target label of on disease c.

- Regularization for Interpretability which, similarly to [10], includes two different terms and to respectively maximize similarity between x and for positive samples and minimize it for negative samples:

-

Regularization for the occurrence map:Where:

- –

- The term considers that an affine transformation of an image does not change the relative location, so it shouldn’t affect the occurrence map, either

- –

- The term regularize to have an occurrence area as small as possible to not include unnecessary regions

2.2.3. Protypes’ Visualization

- Upsampling the occurrence maps to the input image size

- Normalizing with the maximum value of the upsampled mask

- Marking with contour the occurrence values are greater than a factor of 0.3 of the maximum intensity

2.3. Neural Prototype Tree (ProtoTree)

2.3.1. Architecture

2.3.2. Training

2.3.3. Prototypes’ Visualization:

- Forwarding through

-

Create a 2-dim similarity map:Where denotes the location of patch in patches of z

- Upsampling with bicubic interpolation to the shape of

- Visualize as a rectangular patch at the same location nearest to the latent patch

2.4. Protypical Part Shared Network (ProtoPShare)

2.4.1. Architecture

2.4.2. Training

- Computing the data-dependent similarity for pair of prototypes , given by the compliance on the similarity scores for all the training input image . This considers two prototypes similar if they activate alike on the training images, even if far in the latent space:

- Select a percentage of the most similar pairs of prototypes to merge per step

- For each pair, remove prototype and its weights and reuses prototype aggregating weights and

2.4.3. Prototypes’ Visualization

2.5. ProtoPool

2.5.1. Architecture

2.5.2. Training

2.5.3. Prototypes’ Visualization

2.6. Patch-based Intuitive Prototypes Network (PIPNet)

2.6.1. Architecture

2.6.2. Training

-

Alignment Loss, optimizes for near-binary encodings where an image patch corresponds to exactly one prototypeWhere the dot product assess the similarity between the latent patches of two views of an image patch, if

- Tanh-Loss, prevents the trivial solution that one prototype node is activated on all image patches in each image in the dataset forcing that every prototype should be at least once present in a mini-batch

2.6.3. Prototypes’ Visualization

3. Application and Advances in Medical Imaging

- Kim et al. [16] implemented X-ProtoPNet, which introduces the prediction of occurrence maps, which indicate the area where a sign of the disease (i.e., a prototype) is likely to appear, so compares the features in the predicted area with the prototypes. This novelty can help to identify whether the model is focusing on the correct parts of the image or if it is being misled by irrelevant features. They used the NIH chest X-ray dataset [25] for a multilabel classification task (Atelectasis, Cardiomegaly, Effusion, Infiltration, Mass, Nodule, Pneumonia, Pneumathorax Consolidation, Edema, Emphysema, Fibrosis, Pleural Thickening, and Hernia), achieving a mean area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) of 0.822.

- Mohammadjafari et al. [26] applied ProtoPNet to brain MRI scans to detect Alzheimer’s disease, achieving an accuracy of 87.17% in the OASIS dataset [27] and of 91.02% in the ADNI dataset. They used different CNN architectures as feature extractors, and ProtoPNet’s performances were demonstrated to be comparable to or slightly less than their black-box counterparts.

- Barnett et al. [28] designed a novel PP net modifying the training process of ProtoPNet with a loss function including fine-grade expert image annotation and using a top-k average pooling instead max-pooling. They trained their model on an internal dataset of digital mammograms for mass-margin classification and mass-margin malignancy prediction and reported equal or higher accuracy compared to PrototPNet and a black-box model.

- Carloni et al. [29] used ProtoPNet to classify benign/malignant breast masses from mammogram images from a publicly available dataset (CBIS-DDSM [30]), achieving an accuracy of 68.5%. While this performance may not yet be ideal for clinical practice, the authors suggest three tasks for a qualitative evaluation of the explanations by a radiologist.

- Amorim et al. [31] implemented ProtoPNet to classify histologic patches from the PatchCamelyon dataset [32] into benign and malignant using a top-k average pooling instead a max-pooling to extract similarity scores from the activation maps. The authors achieved an accuracy of 98.14% by using Densenet-121 as a feature extractor. This performance was comparable with the one obtained with the black-box CNN.

- Flores-Araiza et al. [33] used ProtoPNet to identify the type of kidney stones (Whewellite, Weddellite, Uric Acid anhydrous, Struvite, Brushite and Cystine) using a simulated in-vivo dataset of endoscopic images. They achieved an accuracy of 88.21% and further evaluated the explanations by perturbing global visual characteristics of images (hue, texture, contrast, shape, brightness, and saturation) to describe their relevance to the prototypes and the sensitivity of the model.

- Kong et al. [34] designed a dual-path PP network, DP-ProtoNet, to increase the generalization performances of single networks. They applied their model to the public ISIC - HAM10000 skin disease dermatoscopic dataset [35]. Compared to ProtoPNet, DP-ProtoNet achieved higher performances while maintaining the model’s interpretability.

- Santiago et al. [36] integrated ProtoPNet with content-based image-retrieval to provide explanations in terms of image-level prototypes and patch-level prototypes. They applied their approach to the skin lesions diagnosis in the public ISIC dermoscopic images [35], outperforming both black-box models and SOTA explainable approaches.

- Cui et al. [37] proposed MBC-ProtoTree, an interpretable fine-grained image classification network based on ProtoTree. They improved ProtoTree by designing a multi-grained feature extraction network, a new background-prototypes removing mechanism, and a novel loss function. The improved model achieved higher classification accuracy on the Chest X-ray dataset.

- Nauta et al. [11] applied their PIP-Net to two open benchmark datasets, respectively for skin cancer diagnosis (ISIC), bone X-ray abnormality detection (MURA), and two real-world datasets respectively for hip and ankle fracture detection. From this study, authors obtained prototypes generally in line with medical knowledge and demonstrated the possibility of correcting the undesired model’s reasoning process with a human-in-the-loop configuration.

- Santos et al. [38] integrated ProtoPNet into a Deep Active Learning framework to predict diabetic retinopathy on the Messidor dataset [39]. The framework allows to train the ProtoPNet on a training set of instances selected using a search strategy, and this may offer benefits in scenarios where the datasets are expensive to be labelled. Performances reported demonstrated the success of applying interpretable models with reduced training data.

- Wang et al. [40] proposed InterNRL integrating ProtoPNet into a student-teacher framework, together with an accurate global image classifier. They applied their model for breast cancer and retinal disease diagnosis and obtained SOTA performances demonstrating the success of the reciprocal learning training paradigm in the medical imaging domain.

- Xu et al. [41] proposed a prototype-based vision transformer applied to COVID-19 classification. They replaced the last two layers of a transformer encoder with a prototype block similar to ProtoPNet and obtained good performances on three different public datasets.

- Sinhamahapatra et al. [42] proposed ProtoVerse, a PP model with a novel objective function applied to the vertebral compression fractures classification. The model interpretability was evaluated by expert radiologists, and predictive performances outperformed ProtoPNet and other SOTA PP architectures.

- Pathak et al. [15] further applied PIP-Net to three different public datasets for breast cancer classification obtaining competitive performances w.r.t. other SOTA black-box and prototype-based models and assessed the coherence of the model with quantitative metrics.

- Gallée et al. [43] applied the Proto-Caps PP-net, in lung chest CT nodules malignancy prediction and performed a human evaluation of the model with a user study.

| Paper | Modality | Dataset | Classes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D image models | ||||

| Singh et al. [20] | X-ray | Chest X-ray, COVID-19 Image |

Normal, Pneumonia, Covid-19 | Acc = 88.99% |

| Singh et al. [21] | X-ray | Chest X-ray, COVID-19 Image |

Normal, Pneumonia, Covid-19 | Acc = 87.27% |

| Singh et al. [22] | CT | COVIDx CT-2 | Normal, Pneumonia, Covid-19 | Acc = 99.24% |

| Kim et al. [16] | X-ray | NIH chest x-ray | Atelectasis, Cardiomegaly, Effusion, Infiltration, Mass, Nodule, Pneumonia, Pneumathorax, Consolidation, Edema, Emphysema, Fibrosis, Pleural Thickening, Hernia |

Mean AUC = 0.822 |

| Mohammadjafari et al. [26] | MRI | OASIS, ADNI | Normal vs. Alzheimer’s disease | Acc: 87.17% (OASIS), 91.02% (ADNI) |

| Barnett et al. [28] | Mammography | Internal dataset | Mass-margin classification Malignancy prediction |

AUC: 0.951 (Mass-margin) 0.84 (Malignancy) |

| Carloni et al. [29] | Mammography | CBIS-DDSM | Benign, malignant | Acc = 68.5% |

| Amorim et al. [31] | Histology | PatchCamelyon | Benign, malignant | Acc = 98.14% |

| Flores-Araiza et al. [33] | Endoscopy | Simulated in-vivo dataset |

Whewellite, Weddellite, Uric Acid anhydrous, Struvite, Brushite, Cystine |

Acc = 88.21% |

| Kong et al. [34] | Dermatoscopic images | ISIC - HAM10000 | Actinic keratosis intraepithelial carcinoma, Nevi, Basal cell carcinoma, Benign Keratosis-like Lesions, Dermatofibroma, Melanoma, Vascular lesions |

F1 = 74.6 |

| Santiago et al. [36] | Dermatoscopic images | ISIC - HAM10000 | Actinic keratosis intraepithelial carcinoma, Nevi, Basal cell carcinoma, Benign Keratosis-like Lesions, Dermatofibroma, Melanoma, Vascular lesions |

Bal Acc = 75.0% (Highest, achieved with DenseNet) |

| Cui et al. [37] | X-ray | Chest X-ray | Normal, Pneumonia | Acc = 91.4% |

| Nauta et al. [11] | Dermoscopic images, X-Ray |

ISIC, MURA, Hip and ankle fraction internal dataset |

Benignant, malignant, Normal, abnormal, Fracture, no fracture |

Acc: 94.1% (ISIC) 82.1% (MURA) 94.0% (Hip) 77.3% (Ankle) |

| Santos et al. [38] | Retinograph | Messidor | Healthy vs. Diseased retinopathy | AUC = 0.79 |

| Wang et al. [40] | Mammography, Retinal OCT |

Mammography internal dataset, CMMD, NEH OCT |

Cancer vs. Non-cancer Benignant vs. Malignant Normal, Drusen, and Choroidal neovascularization |

AUC = 91.49 (Internal) AUC = 89.02 (CMMD) Acc = 91.9 (NEH OCT) |

| Xu et al. [41] | X-ray Lung CT |

COVIDx CXR-3 COVID-QU-Ex Lung CT scan |

COVID-10 Normal Pneumonia |

F1: 99.2 96.8 98.5 |

| Sinhamahapatra et al. [42] | CT | VerSe’19 dataset | Fracture vs. Healthy | F1 = 75.97 |

| Pathak et al. [15] | Mammography | CBIS, VinDir, CMMD | Benignant vs. Malignant | F1 (PIP-Net model): 63±3% (CBIS) 63±3% (VinDir) 70±1% (CMMD) |

| Gallée et al. [43] | Thorax CT | LIDC-IDRI | Benignant vs. Malignant | Acc = 93.0% |

| 3D image models | ||||

| Wei et al. [44] | 3D mpMRI: T1, T1CE, T2, FLAIR | BraTS 2020 | High-grade vs. Low-grade glioma | Bal Acc = 85.8% |

| Vaseli et al. [46] | Echocardiography | Private dataset TMED-2 |

Normal vs. Mild vs. Severe Aortic Stenosis |

Acc: 80.0% (Private) 79.7 (TMED-2)% |

| De Santi et al. [48] | 3D MRI | ADNI | Normal vs. Alzheimer’s disease | Bal Acc = 82.02% |

| Multimodal models | ||||

| Wolf et al. [51] | 3D 18F-FDG PET and Tabular data | ADNI | Normal vs. Alzheimer’s disease | Bal Acc = 60.7% |

| Wang et al. [52] | Chest X-ray and reports | MIMIC-CXR | Atelectasis, Cardiomegaly, Consolidation, Edema, Enlarged Cardiomediastinum, Fracture, Lung Lesion, Lung Opacity, Pleural Effusion, Pleural Other, Pneumonia, Pneumothorax, Support Device |

Mean AUC = 0.828 |

| De Santi et al. [53] | 3D MRI and Ages | ADNI | Normal vs. Alzheimer’s disease | Bal Acc = 83.04% |

4. Evaluation of Prototypes

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AP | activation precision |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CT | Computed Thomography |

| CV | Computer Vision |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| IDS | incremental deletion score |

| MI | Medical Imaging |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MR | Magnetic Resonance |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| OoD | Out-of-Distribution |

| PIPNet | Patch-based Intuitive Prototypes Network |

| PP | Part-Prototype |

| RX | Radiografy |

| SGD | Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| SOTA | State-of-the-Art |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Salahuddin, Z.; Woodruff, H.C.; Chatterjee, A.; Lambin, P. Transparency of deep neural networks for medical image analysis: A review of interpretability methods. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borys, K.; Schmitt, Y.A.; Nauta, M.; Seifert, C.; Krämer, N.; Friedrich, C.M.; Nensa, F. Explainable AI in medical imaging: An overview for clinical practitioners – Saliency-based XAI approaches. European Journal of Radiology 2023, 162, 110787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borys, K.; Schmitt, Y.A.; Nauta, M.; Seifert, C.; Krämer, N.; Friedrich, C.M.; Nensa, F. Explainable AI in medical imaging: An overview for clinical practitioners – Beyond saliency-based XAI approaches. European Journal of Radiology 2023, 162, 110786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgaier, J.; Mulansky, L.; Draelos, R.L.; Pryss, R. How does the model make predictions? A systematic literature review on the explainability power of machine learning in healthcare. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2023, 143, 102616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, L.; Brcic, M.; Cabitza, F.; Choi, J.; Confalonieri, R.; Ser, J.D.; Guidotti, R.; Hayashi, Y.; Herrera, F.; Holzinger, A.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) 2.0: A manifesto of open challenges and interdisciplinary research directions. Information Fusion 2024, 106, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, O.; Liu, H.; Chen, C.; Rudin, C. Deep Learning for Case-Based Reasoning through Prototypes: A Neural Network that Explains Its Predictions 2017.

- Cynthia, R. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nature Machine Intelligence 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauta, M.; Schlötterer, J.; van Keulen, M.; Seifert, C. PIP-Net: Patch-Based Intuitive Prototypes for Interpretable Image Classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2023, pp. 2744–2753.

- Biederman, I. Recognition-by-Components: A Theory of Human Image Understanding. Psychological Review 1917, M, 115–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, O.; Tao, C.; Barnett, A.J.; Su, J.; Rudin, C. This Looks Like That: Deep Learning for Interpretable Image Recognition 2018.

- Nauta, M.; Hegeman, J.H.; Geerdink, J.; Schlötterer, J.; Keulen, M.v.; Seifert, C. Interpreting and Correcting Medical Image Classification with PIP-Net. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence. ECAI 2023 International Workshops, Cham, 2024; pp. 198–215.

- Nauta, M.; Seifert, C. The Co-12 Recipe for Evaluating Interpretable Part-Prototype Image Classifiers. In Proceedings of the Explainable Artificial Intelligence; Longo, L., Ed., Cham, 2023; pp. 397–420.

- Doshi-Velez, F.; Kim, B. Towards A Rigorous Science of Interpretable Machine Learning. arXiv: Machine Learning 2017.

- Jin, W.; Li, X.; Fatehi, M.; Hamarneh, G. Guidelines and evaluation of clinical explainable AI in medical image analysis. Medical Image Analysis 2023, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.; Schlötterer, J.; Veltman, J.; Geerdink, J.; Keulen, M.V.; Seifert, C.; Pathak, S. Prototype-Based Interpretable Breast Cancer Prediction Models: Analysis and Challenges. In Proceedings of the Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Springer, Cham, 2024, pp. 21–42. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Kim, S.; Seo, M.; Yoon, S. XProtoNet: diagnosis in chest radiography with global and local explanations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 15719–15728.

- Nauta, M.; van Bree, R.; Seifert, C. Neural Prototype Trees for Interpretable Fine-Grained Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2021, pp. 14933–14943.

- Rymarczyk, D.; Łukasz Struski.; Tabor, J.; Zieliński, B. ProtoPShare: Prototypical Parts Sharing for Similarity Discovery in In-terpretable Image Classification. 11. 11. [CrossRef]

- Rymarczyk, D.; Łukasz Struski.; Górszczak, M.; Lewandowska, K.; Tabor, J.; Zieliński, B. Interpretable Image Classification with Differentiable Prototypes Assignment. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 2022, 13672 LNCS, 351–368. [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Yow, K.C. These do not look like those: An interpretable deep learning model for image recognition. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 41482–41493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Yow, K.C. An Interpretable Deep Learning Model for Covid-19 Detection with Chest X-Ray Images. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 85198–85208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Yow, K.C. Object or background: An interpretable deep learning model for COVID-19 detection from CT-scan images. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kermany, D.; Zhang, K.; Goldbaum, M. Large dataset of labeled optical coherence tomography (oct) and chest x-ray images. Mendeley Data 2018, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.P.; Morrison, P.; Dao, L. COVID-19 image data collection. arXiv preprint 2020, arXiv:2003.11597. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Peng, Y.; Lu, L.; Lu, Z.; Bagheri, M.; Summers, R.M. Chestx-ray8: Hospital-scale chest x-ray database and benchmarks on weakly-supervised classification and localization of common thorax diseases. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 2097–2106.

- Mohammadjafari, S.; Cevik, M.; Thanabalasingam, M.; Basar, A.; Initiative, A.D.N. Using ProtoPNet for Interpretable Alzheimer’s Disease Classification. In Proceedings of the Canadian AI 2021. Canadian Artificial Intelligence Association (CAIAC), 8 2021. https://caiac.pubpub.org/pub/klwhoig4. [CrossRef]

- Marcus, D.S.; Wang, T.H.; Parker, J.; Csernansky, J.G.; Morris, J.C.; Buckner, R.L. Open Access Series of Imaging Studies (OASIS): cross-sectional MRI data in young, middle aged, nondemented, and demented older adults. Journal of cognitive neuroscience 2007, 19, 1498–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, A.J.; Schwartz, F.R.; Tao, C.; Chen, C.; Ren, Y.; Lo, J.Y.; Rudin, C. A case-based interpretable deep learning model for classification of mass lesions in digital mammography. Nature Machine Intelligence 2021 3:12 2021, 3, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carloni, G.; Berti, A.; Iacconi, C.; Pascali, M.A.; Colantonio, S. On the applicability of prototypical part learning in medical images: breast masses classification using ProtoPNet. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition. Springer, 2022, pp. 539–557.

- Lee, R.S.; Gimenez, F.; Hoogi, A.; Miyake, K.K.; Gorovoy, M.; Rubin, D.L. A curated mammography data set for use in computer-aided detection and diagnosis research. Scientific data 2017, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, J.P.; Abreu, P.H.; Santos, J.; Müller, H. Evaluating Post-hoc Interpretability with Intrinsic Interpretability. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.03002 2023.

- Bejnordi, B.E.; Veta, M.; Van Diest, P.J.; Van Ginneken, B.; Karssemeijer, N.; Litjens, G.; Van Der Laak, J.A.; Hermsen, M.; Manson, Q.F.; Balkenhol, M.; et al. Diagnostic assessment of deep learning algorithms for detection of lymph node metastases in women with breast cancer. Jama 2017, 318, 2199–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Araiza, D.; Lopez-Tiro, F.; El-Beze, J.; Hubert, J.; Gonzalez-Mendoza, M.; Ochoa-Ruiz, G.; Daul, C. Deep prototypical-parts ease morphological kidney stone identification and are competitively robust to photometric perturbations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp. 295–304.

- Kong, L.; Gong, L.; Wang, G.; Liu, S. An interpretable dual path prototype network for medical image diagnosis. Proceedings - 2023 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications, TrustCom/BigDataSE/CSE/EUC/iSCI 2023 2023, pp. 2797–2804. [CrossRef]

- Tschandl, P.; Rosendahl, C.; Kittler, H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Scientific Data 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, C.; Correia, M.; Verdelho, M.R.; Bissoto, A.; Barata, C. Global and Local Explanations for Skin Cancer Diagnosis Using Prototypes. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 2023, 14393, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Gong, J.; Wang, G.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, S. An Novel Interpretable Fine-grained Image Classification Model Based on Improved Neural Prototype Tree. Proceedings - IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems 2023, 2023-May. [CrossRef]

- de A. Santos, I.B.; de Carvalho, A.C.P.L.F. ProtoAL: Interpretable Deep Active Learning with prototypes for medical imaging, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CV/2404.04736].

- Gu, Z.; Cheng, J.; Fu, H.; Zhou, K.; Hao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Gao, S.; Liu, J. CE-Net: Context Encoder Network for 2D Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2019, 38, 2281–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, F.; Elliott, M.; Kwok, C.F.; Pena-Solorzano, C.; Frazer, H.; Mccarthy, D.J.; Carneiro, G. An Interpretable and Accurate Deep-Learning Diagnosis Framework Modeled With Fully and Semi-Supervised Reciprocal Learning. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2024, 43, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Meng, Z. Interpretable vision transformer based on prototype parts for COVID-19 detection. IET Image Processing 2024, 18, 1927–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinhamahapatra, P.; Shit, S.; Sekuboyina, A.; Husseini, M.; Schinz, D.; Lenhart, N.; Menze, J.; Kirschke, J.; Roscher, K.; Guennemann, S. Enhancing Interpretability of Vertebrae Fracture Grading using Human-interpretable Prototypes. Journal of Machine Learning for Biomedical Imaging 2024, 2024, 977–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallée, L.; Lisson, C.S.; Lisson, C.G.; Drees, D.; Weig, F.; Vogele, D.; Beer, M.; Götz, M. Evaluating the Explainability of Attributes and Prototypes for a Medical Classification Model. In Proceedings of the Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Springer, Cham, 2024, pp. 43–56. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Tam, R.; Tang, X. MProtoNet: A Case-Based Interpretable Model for Brain Tumor Classification with 3D Multi-parametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging with Deep Learning, 2023.

- Nauta, M.; Trienes, J.; Pathak, S.; Nguyen, E.; Peters, M.; Schmitt, Y.; Schlötterer, J.; van Keulen, M.; Seifert, C. From Anecdotal Evidence to Quantitative Evaluation Methods: A Systematic Review on Evaluating Explainable AI. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseli, H.; Gu, A.N.; Amiri, S.N.A.; Tsang, M.Y.; Fung, A.; Kondori, N.; Saadat, A.; Abolmaesumi, P.; Tsang, T.S. ProtoASNet: Dynamic Prototypes for Inherently Interpretable and Uncertainty-Aware Aortic Stenosis Classification in Echocardiography. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 2023, 14225 LNCS, 368–378. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Long, G.; Wessler, B.; Hughes, M. TMED 2: a dataset for semi-supervised classification of echocardiograms, 2022.

- De Santi, L.A.; Schlötterer, J.; Scheschenja, M.; Wessendorf, J.; Nauta, M.; Positano, V.; Seifert, C. PIPNet3D: Interpretable Detection of Alzheimer in MRI Scans, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CV/2403.18328].

- van de Beld, J.J.; Pathak, S.; Geerdink, J.; Hegeman, J.H.; Seifert, C. Feature Importance to Explain Multimodal Prediction Models. a Clinical Use Case. Springer, Cham, 2024, pp. 84–101. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; King, I. Multimodality in meta-learning: A comprehensive survey. Know.-Based Syst. 2022, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.N.; Pölsterl, S.; Wachinger, C. Don’t PANIC: Prototypical Additive Neural Network for Interpretable Classification of Alzheimer’s Disease. In Proceedings of the Information Processing in Medical Imaging: 28th International Conference, IPMI 2023, San Carlos de Bariloche, Argentina, June 18–23, 2023, Proceedings, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2023; p. 82–94. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, J.; Tian, C.; Ma, X.; Liu, S. A Novel Multimodal Prototype Network for Interpretable Medical Image Classification. Conference Proceedings - IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics 2023, pp. 2577–2583. [CrossRef]

- De Santi, L.A.; Schlötterer, J.; Nauta, M.; Positano, V.; Seifert, C. Patch-based Intuitive Multimodal Prototypes Network (PIMPNet) for Alzheimer’s Disease classification, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CV/2407.14277].

- Johnson, A.E.W.; Pollard, T.J.; Greenbaum, N.R.; Lungren, M.P.; ying Deng, C.; Peng, Y.; Lu, Z.; Mark, R.G.; Berkowitz, S.J.; Horng, S. MIMIC-CXR-JPG, a large publicly available database of labeled chest radiographs, 2019, [arXiv:cs.CV/1901.07042].

- van der Velden, B.H.; Kuijf, H.J.; Gilhuijs, K.G.; Viergever, M.A. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in deep learning-based medical image analysis. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 79, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabitza, F.; Campagner, A.; Ronzio, L.; Cameli, M.; Mandoli, G.E.; Pastore, M.C.; Sconfienza, L.M.; Folgado, D.; Barandas, M.; Gamboa, H. Rams, hounds and white boxes: Investigating human–AI collaboration protocols in medical diagnosis. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2023, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Höhne, M.M.C.; Hansen, S.; Jenssen, R.; Kampffmeyer, M. This looks More Like that: Enhancing Self-Explaining Models by Prototypical Relevance Propagation. Pattern Recogn. 2023, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opłatek, S.; Rymarczyk, D.; Zieliński, B. Revisiting FunnyBirds Evaluation Framework for Prototypical Parts Networks. In Proceedings of the Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Springer, Cham, 2024, pp. 57–68. Cham. [CrossRef]

- Xu-Darme, R.; Quénot, G.; Chihani, Z.; Rousset, M.C. Sanity checks for patch visualisation in prototype-based image classification. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), 2023, pp. 3691–3696. [CrossRef]

| Co-12 Property | Description |

|---|---|

| Content | |

| Correctness: | Since PP models are interpretable by design, the generation of the explanations is made together with the prediction and the reasoning process is correctly represented by design. By the way, the faithfulness of the prototype visualization (from the latent representation to the input image patches), originally performed by performing a bicubic upsampling, is not guaranteed by design and should be evaluated. |

| Completeness: | The relation between prototypes and classes is transparently shown, so the output-completeness is fulfilled by design, but the computation performed by the CNN backbone is not taken into consideration. |

| Consistency: | PP models should not have random components in their designs, but nondeterminism may occur from the backbones’ initialisation and random seeds. It might be assessed by comparing explanations from models trained with different initializations or with a different shuffling of the training data. |

| Continuity: | Evaluate whether slightly perturbed inputs lead to the same explanation, given that the model makes the same classification. |

| Contrastivity: | The incorporated interpretability of PP models results in a contrastivity incorporated by design, such a different classification corresponds to a different reasoning and hence to a different explanation. This evaluation might also include a target sensitivity analysis, by inspecting where prototypes are detected in the test image. |

| Covariate complexity: | Assess the complexity of the features present in the prototypes with ground truth, such as predefined concepts provided by human judgements (perceived homogeneity) or with object part annotations. |

| Presentation | |

| Compactness: | Evaluate the number of prototypes which constitute the full classification model (global explanation size), in every input image (local explanation sizes), and the redundancy in the information content presented in different prototypes. The size of the explanation should be appropriate to not overwhelm the user. |

| Composition: | Asses how PP can be best presented to the user, and how these prototypes can be best structured and included in the reasoning process by comparing different explanation formats or by asking users about their preferences regarding the presentation and structure of the explanation. |

| Confidence: | Estimate the confidence of the explanation generation method, including measurements such as the prototype similarity scores. |

| User | |

| Context: | Evaluate PP models with application-grounded user studies, similar to evaluation with heatmaps, to understand their needs. |

| Coherence: | Prototypes are often evaluated based on anecdotal evidence, with automated evaluation with an annotated dataset, or with manual evaluation. User studies might include the assessment of satisfaction, preference and trust for part-prototypes. |

| Controllability: | Ability to directly manipulate the explanation and the model’s reasoning e.g., enable users to suppress or modify learned prototypes, eventually with the aid of a graphical user interface. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).