Submitted:

09 September 2024

Posted:

10 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Pathogenesis of Osteomyelitis

3. Microorganisms Associated with Osteomyelitis in Pigs

4. Risk Factors for Osteomyelitis in Pigs

5. Osteomyelitis as a Cause of Carcass Condemnation and Sanitary Decision Criteria

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Markets, R.a. (2020). Global pork market forecast (2018 to 2026) - by production, consumption, import, export & company. from https://www.globenewswire.com/n.

- Tao, F., & Peng, YA method for nondestructive prediction of pork meat quality and safety attributes by hyperspectral imaging technique. J. Food Eng. 2014, 126, 98-106. [CrossRef]

- Riess, L. E., & Hoelzer, K. Implementation of visual-only swine inspection in the European Union: Challenges, opportunities, and lessons learned. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83(11), 1918-1928. [CrossRef]

- Li, T. T., Langforth, S., Isbrandt, R., Langkabel, N., Sotiraki, S., Anastasiadou, S., ... & Meemken, D. Food chain information for pigs in Europe: A study on the status quo, the applicability and suggestions for improvements. Food Control 2024, 157, 110174. [CrossRef]

- Vecerek, V.; Voslarova, E.; Semerad, Z.; Passantino, A. The health and welfare of pigs from the perspective of post mortem findings in slaughterhouses. Animals 2020, 10, 825. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Diez, J.; Coelho, A.C. Causes and factors related to pig carcass condemnation. Vet. Med. 2014, 59, 194–201. https://doi.org./10.17221/7480-VETMED.

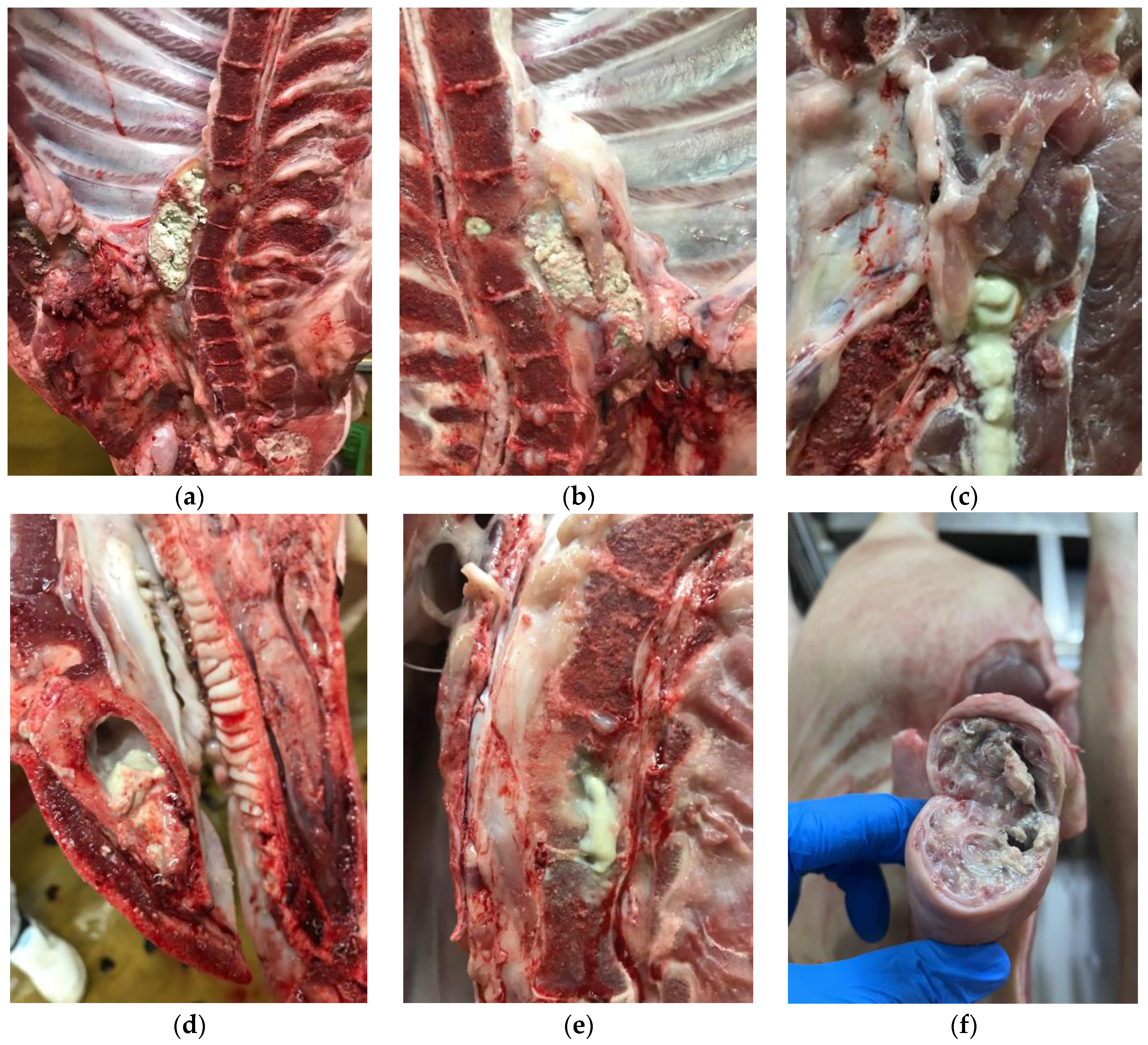

- Teiga-Teixeira, P., Alves Rodrigues, M., Moura, D., Teiga-Teixeira, E., & Esteves, A. Osteomyelitis in Pig Carcasses at a Portuguese Slaughterhouse: Association with Tail-Biting and Teeth Resection. Animals 2024, 14(12), 1794. [CrossRef]

- Baekbo, A.K.; Petersen, J.V.; Larsen, M.H.; Alban, L. The food safety value of de-boning finishing pig carcasses with lesions indicative of prior septicemia. Food Control 2016, 69, 177–184. [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Rojavin, Y.; Jamali, A.A.; Wasielewski, S.J.; Salgado, C.J. Animal models for the study of osteomyelitis. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2009, 23, 148–154. [CrossRef]

- Vieira-Pinto, M., Azevedo, J., Poeta, P., Pires, I., Ellebroek, L., Lopes, R., ... & Alban, L. Classification of vertebral osteomyelitis and associated judgment applied during post-mortem inspection of swine carcasses in Portugal. Foods 2020, 9(10), 1502. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L. K., Johansen, A. S., & Jensen, H. E. Porcine models of biofilm infections with focus on pathomorphology. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1961. [CrossRef]

- Madson, D. M., Arruda, P. H., & Arruda, B. L. Nervous and locomotor system. In Diseases of swine, 11th ed. Jeffrey, J.Z., Lock, A.K., Ramirez, A., Kent, J.S., Gregory, W.S., Zhang, J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 339–372. [CrossRef]

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/627 of 15 March 2019, laying down uniform practical arrangements for the performance of official controls on products of animal origin intended for human consumption in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2017/625 of the European Parliament and of the Council and amending Commission Regulation (EC) No 2074/2005 as regards official controls. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, 131, 51–100.

- Clegg, P. D. Osteomyelitis in the veterinary species. In Biofilms and veterinary medicine. Percival, S., Knottenbelt, D., Cochrane, C. Berlin, Eds; Springer Series on Biofilms, vol 6. Springer, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 175-190. [CrossRef]

- Roy, M., Somerson, J. S., Kerr, K. G., & Conroy, J. L. Pathophysiology and pathogenesis of osteomyelitis. INTECH Open Access Publisher 2012, 1-26.

- González-Martín, M., Silva, V., Poeta, P., Corbera, J. A., & Tejedor-Junco, M. T. Microbiological aspects of osteomyelitis in veterinary medicine: drawing parallels to the infection in human medicine. Vet. Q. 2022, 42(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Craig, L.E.; Dittmer, K.E.; Thompson, K.G. Bones and Joints. In Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 6th ed.; Maxie, G., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 16–163.

- Gieling, F., Peters, S., Erichsen, C., Richards, R. G., Zeiter, S., & Moriarty, T. F. Bacterial osteomyelitis in veterinary orthopedics: pathophysiology, clinical presentation and advances in treatment across multiple species. Vet. J. 2019, 250, 44-54. [CrossRef]

- Giebels, F., Geissbühler, U., Oevermann, A., Grahofer, A., Olias, P., Kuhnert, P., ... & Stein, V. M. Vertebral fracture due to Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae osteomyelitis in a weaner. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- García-Díez, J., Saraiva, S., Moura, D., Grispoldi, L., Cenci-Goga, B. T., & Saraiva, C. The importance of the slaughterhouse in surveilling animal and public health: a systematic review. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10(2), 167. [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.R.; Friendship, R.M. Digestive system. In Disease of Swine, 11th ed.; Zimmerman, J.J., Karriker, L.A., Ramirez, A., Schwartz, K.J., Stevenson, G.W., Zhang, J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 234–263. [CrossRef]

- Serbessa, T. A., Geleta, Y. G., & Terfa, I. O. Review on diseases and health management of poultry and swine. Int. j. avian wildl. biol. 2023, 7(1), 27-38. [CrossRef]

- Kawanishi, M., Matsuda, M., Abo, H., Ozawa, M., Hosoi, Y., Hiraoka, Y., ... & Sekiguchi, H. Prevalence and Genetic Characterization of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Pigs in Japan. Antibiotics 2024, 13(2), 155. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. P., Sharma, M., Gilson, D., Anjum, M., & Teale, C. J. Livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in slaughtered pigs in England. Epidemiol. Infect. 2021, 149, e236. [CrossRef]

- EFSA - Monitoring of foodborne diseases. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/microstrategy/FBO-dashboard (accessed on 1st august 2024).

- Pal, M., Shuramo, M. Y., Tewari, A., Srivastava, J. P., & HD, C. Staphylococcus aureus from a Commensal to Zoonotic Pathogen: A Critical Appraisal. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. Res 2023, 7, 220-228. [CrossRef]

- Gungor, C., Onmaz, N. E., Gundog, D. A., Yavas, G. T., Koskeroglu, K., & Gungor, G. Four novel bacteriophages from slaughterhouse: Their potency on control of biofilm-forming MDR S. aureus in beef model. Food Control 2024, 156, 110146. [CrossRef]

- Bouchami, O., Fraqueza, M. J., Faria, N. A., Alves, V., Lawal, O. U., de Lencastre, H., & Miragaia, M. Evidence for the dis-semination to humans of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 through the pork production chain: a study in a Portuguese slaughterhouse. Microorganisms 2020, 8(12), 1892. [CrossRef]

- Santos, V., Gomes, A., Ruiz-Ripa, L., Mama, O. M., Sabença, C., Sousa, M., ... & Poeta, P. A. C. Q. D. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus CC398 in purulent lesions of piglets and fattening pigs in Portugal. Microb. Drug Resist. 2020, 26(7), 850-856. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Liang, Y., Yu, L., Chen, M., Guo, Y., Kang, Z., ... & Liu, M. TatD DNases contribute to biofilm formation and virulence in Trueperella pyogenes. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 758465. [CrossRef]

- Costinar, L., Badea, C., Marcu, A., Pascu, C., & Herman, V. Multiple Drug Resistant Streptococcus Strains—An Actual Problem in Pig Farms in Western Romania. Antibiotics 2024, 13(3), 277. [CrossRef]

- Tamai, I. A., Mohammadzadeh, A., Mahmoodi, P., Pakbin, B., & Salehi, T. Z. Antimicrobial susceptibility, virulence genes and genomic characterization of Trueperella pyogenes isolated from abscesses in dairy cattle. Res. Vet. Sci. 2023, 154, 29-36. [CrossRef]

- Jensen TK, Boye M, Hagedorn-Olsen T, Riising HJ, Angen O. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae osteomyelitis in pigs demonstrated by fluorescent in situ hybridization. Vet Pathol. 1999 36:258–61. [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Pauka, I., Hartmann, M., Merkel, J., & Kreienbrock, L. Coinfections and Phenotypic Antimicrobial Resistance in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae Strains Isolated From Diseased Swine in North Western Germany—Temporal Patterns in Samples From Routine Laboratory Practice From 2006 to 2020. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 8, 802570. [CrossRef]

- Maes, D., Sibila, M., Pieters, M., Haesebrouck, F., Segalés, J., & de Oliveira, L. G. Review on the methodology to assess respiratory tract lesions in pigs and their production impact. Vet. Res. 2023, 54(1), 8. [CrossRef]

- Seakamela, E. M., Henton, M. M., Jonker, A., Kayoka-Kabongo, P. N., & Matle, I. Temporal and Serotypic Dynamics of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae in South African Porcine Populations: A Retrospective Study from 1985 to 2023. Pathogens 2024, 13(7), 599. [CrossRef]

- Tenk, M., Tóth, G., Márton, Z., Sárközi, R., Szórádi, A., Makrai, L., ... & Fodor, L. Examination of the Virulence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae Serovar 16 in Pigs. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11(2), 62. [CrossRef]

- Meyns, T., Van Steelant, J., Rolly, E., Dewulf, J., Haesebrouck, F., & Maes, D. A cross-sectional study of risk factors as-sociated with pulmonary lesions in pigs at slaughter. Vet. J. 2011, 187(3), 388-392. [CrossRef]

- Vom Brocke, A.L.; Karnholz, C.; Madey-Rindermann, D.; Gauly, M.; Leeb, C.; Winckler, C.; Schrader, L.; Dippel, S. Tail Lesions in Fattening Pigs: Relationships with Post-mortem Meat Inspection and Influence of a Tail biting Management Tool. Animal 2019, 13, 835–844. [CrossRef]

- Schrøder-Petersen, D.L.; Simonsen, H.B. Tail biting in pigs. Vet. J. 2001, 162, 196–210. [CrossRef]

- Kritas, S.K.; Morrison, R.B. Relationships between tail biting in pigs and disease lesions and condemnations at slaughter. Vet. Rec. 2007, 160, 149–152. [CrossRef]

- Valros, A., & Heinonen, M. Save the pig tail. Porc. Health Manag. 2015, 1, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J., Jaro, P. J., Aduriz, G., Gómez, E. A., Peris, B., & Corpa, J. M. Carcass condemnation causes of growth retarded pigs at slaughter. Vet. J. 2007, 174(1), 160-164. [CrossRef]

- Lindén, J.; Pohjola, L.; Rossow, L.; Tognetti, D. Meat Inspection Lesions. In Meat Inspection and Control in the Slaughterhouse, 1st ed.; Ninios, T., Lundén, J., Korkeala, H., Fredriksson-Ahomaa, M., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: West Sussex, UK, 2014; Chapter 8; pp. 163–199. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, H.E.; Leifsson, P.S.; Nielsen, O.L.; Agerholm, J.S.; Iburg, T. Meat Inspection: The Pathoanatomic Basis; Bifolia: Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2017; pp. 661–663.

- Alban, L., Petersen, J. V., & Busch, M. E. A comparison between lesions found during meat inspection of finishing pigs raised under organic/free-range conditions and conventional, indoor conditions. Porc. Health Manag. 2015, 1, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Harley, S., More, S., Boyle, L., Connell, N. O., & Hanlon, A. Good animal welfare makes economic sense: potential of pig abattoir meat inspection as a welfare surveillance tool. Ir. Vet. J. 2012, 65, 1-12.

- Nannoni, E., Valsami, T., Sardi, L., & Martelli, GTail docking in pigs: a review on its short-and long-term consequences and effectiveness in preventing tail biting. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 13(1), 3095.

- Reese, D.; Straw, B.E. Teeth Clipping—Have You Tried to Quit? Neb. Swine Rep. 2005, 33, 12–13. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/coopext_swine/33 (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Fertner, M., Denwood, M., Birkegård, A. C., Stege, H., & Boklund, A. Associations between antibacterial Treatment and the Prevalence of Tail-Biting-related sequelae in Danish Finishers at slaughter. Front. vet. sci. 2017, 4, 182. [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Neves, E., Müller, A., Correia, A., Capas-Peneda, S., Carvalho, M., Vieira, S., & Cardoso, M. F. Food chain information: Data quality and usefulness in meat inspection in Portugal. J. Food Prot. 2018, 81(11), 1890-1896. [CrossRef]

- DGAV. Análise Exploratória dos Dados de Abate de Ungulados Para Consumo Humano em Portugal Entre Janeiro de 2011 e Dezembro de 2019. 2020. Available online: https://www.dropbox.com/s/26p3sukb6vx6koc/Dados%20de%20abates%20e%20reprova%C3%A7%C3%B5es%20Ungulados%202011%20a%202019.pdf?dl=0 (accessed on 6th july 2024).

- Franco, R., Gonçalves, S., Cardoso, M. F., & Gomes-Neves, E. Tail-docking and tail biting in pigs: Findings at the slaughterhouse in Portugal. Livest. Sci. 2021, 254, 104756. [CrossRef]

- Bueno, L. S., Caldara, F. R., Nääs, I. A., Salgado, D. D., García, R. G., & Almeida Paz, I. C. Swine carcass condemnation in commercial slaughterhouses. Rev. MVZ Cordoba 2013, 18(3), 3836-3842.

- Ceccarelli, M., Leprini, E., Sechi, P., Iulietto, M. F., Grispoldi, L., Goretti, E., & Cenci-Goga, B. T. Analysis of the causes of the seizure and destruction of carcasses and organs in a slaughterhouse in central Italy in the 2010-2016 period. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2018, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Guardone, L., Vitali, A., Fratini, F., Pardini, S., Cenci Goga, B. T., Nucera, D., & Armani, A. A retrospective study after 10 years (2010–2019) of meat inspection activity in a domestic swine abattoir in tuscany: The slaughterhouse as an epidemiological observatory. Animals 2020, 10(10), 1907. [CrossRef]

- Akkina, J., Burkom, H., Estberg, L., Carpenter, L., Hennessey, M., & Meidenbauer, K. Feral Swine Commercial Slaughter and Condemnation at Federally Inspected Slaughter Establishments in the United States 2017–2019. Front. vet. sci. 2021, 8, 690346. [CrossRef]

- Rosamilia, A., Galletti, G., Benedetti, S., Guarnieri, C., Luppi, A., Capezzuto, S., ... & Marruchella, G. Condemnation of Porcine Carcasses: A Two-Year Long Survey in an Italian High-Throughput Slaughterhouse. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10(7), 482. [CrossRef]

- Alban, L., Vieira-Pinto, M., Meemken, D., Maurer, P., Ghidini, S., Santos, S., ... & Langkabel, N. Differences in code terminology and frequency of findings in meat inspection of finishing pigs in seven European countries. Food Control 2022, 132, 108394. [CrossRef]

- Vieira-Pinto, M., Langkabel, N., Santos, S., Alban, L., Laguna, J. G., Blagojevic, B., ... & Laukkanen-Ninios, R. A European survey on post-mortem inspection of finishing pigs: Total condemnation criteria to declare meat unfit for human consumption. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 152, 72-82. [CrossRef]

- Ninios, T. Judgment of meat. In Meat Inspection and Control in the Slaughterhouse, 1st ed.; Ninios, T., Lundén, J., Korkeala, H., Fredriksson-Ahomaa, M., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: West Sussex, UK, 2014; Chapter 10; pp. 219–224.

- Laukkanen-Ninios, R., Ghidini, S., Gomez Laguna, J., Langkabel, N., Santos, S., Maurer, P., ... & Vieira-Pinto, M. Additional post-mortem inspection procedures and laboratory methods as supplements for visual meat inspection of finishing pigs in Europe—Use and variability. J. Consum. Prot. Food S. 2022, 17(4), 363-375. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).