– T.S. Eliot

I. Introduction

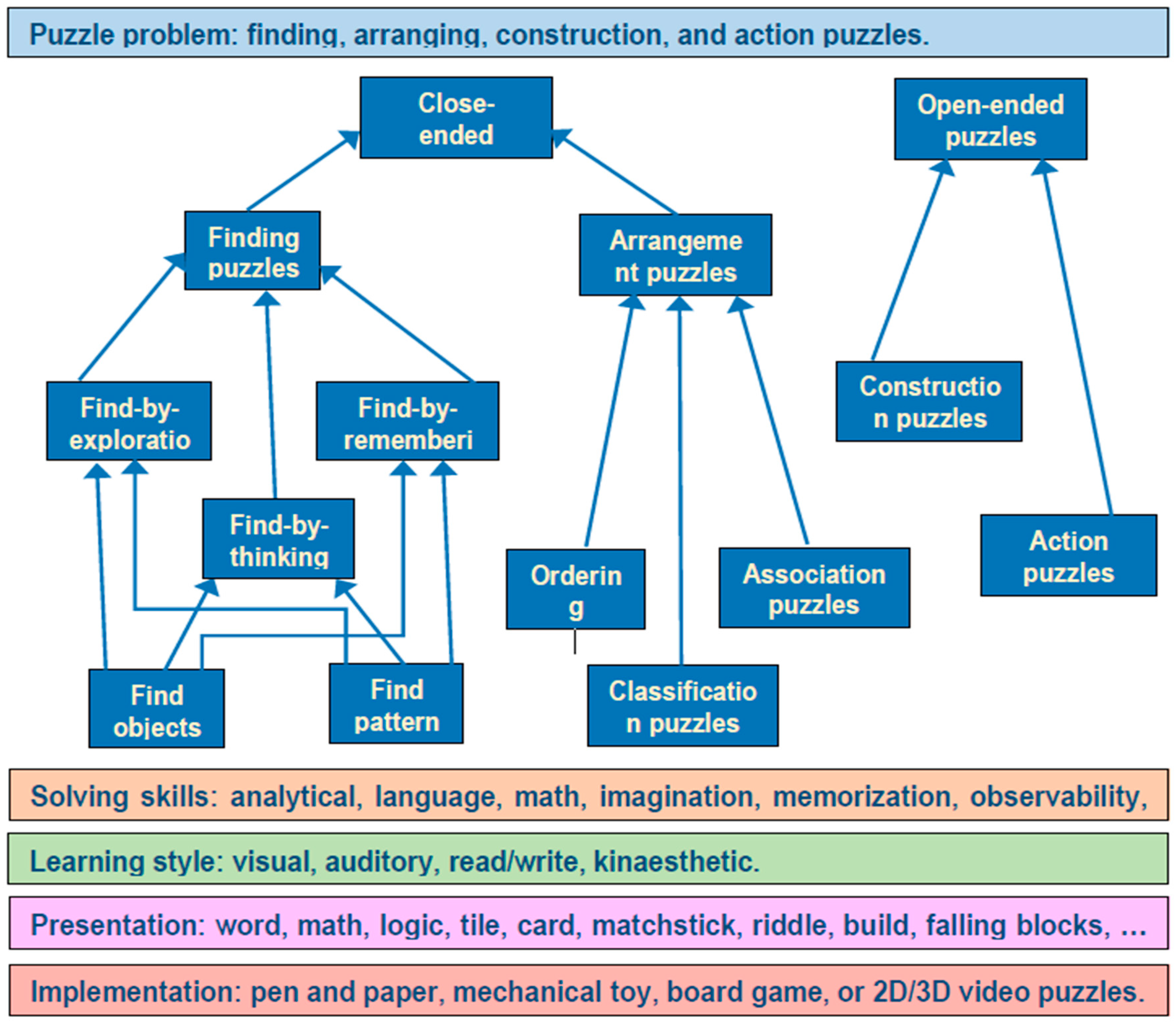

It is a real breathtaking task to understand how nature presents various types of puzzles similar to those created for entertainment [

1], such as jigsaw puzzles and logical puzzles, as a solid emphasis the importance of recognizing the type of puzzle one is dealing with in research, as solutions may require making connections to different fields or thinking outside the box. Understanding the hierarchical problem structure and adapting perspectives based on the nature of the puzzle can enhance scientific creativity and expedite the discovery process in fields like mathematics, physics, and engineering.

Undoubtedly, this consolidates the importance of creative problem-solving in scientific research [

1], contrasting it with learning about science, satifying the need for innovative thinking when deciding on experiments or analyses, highlighting the essence of “night science” as a term for problem-solving in research.

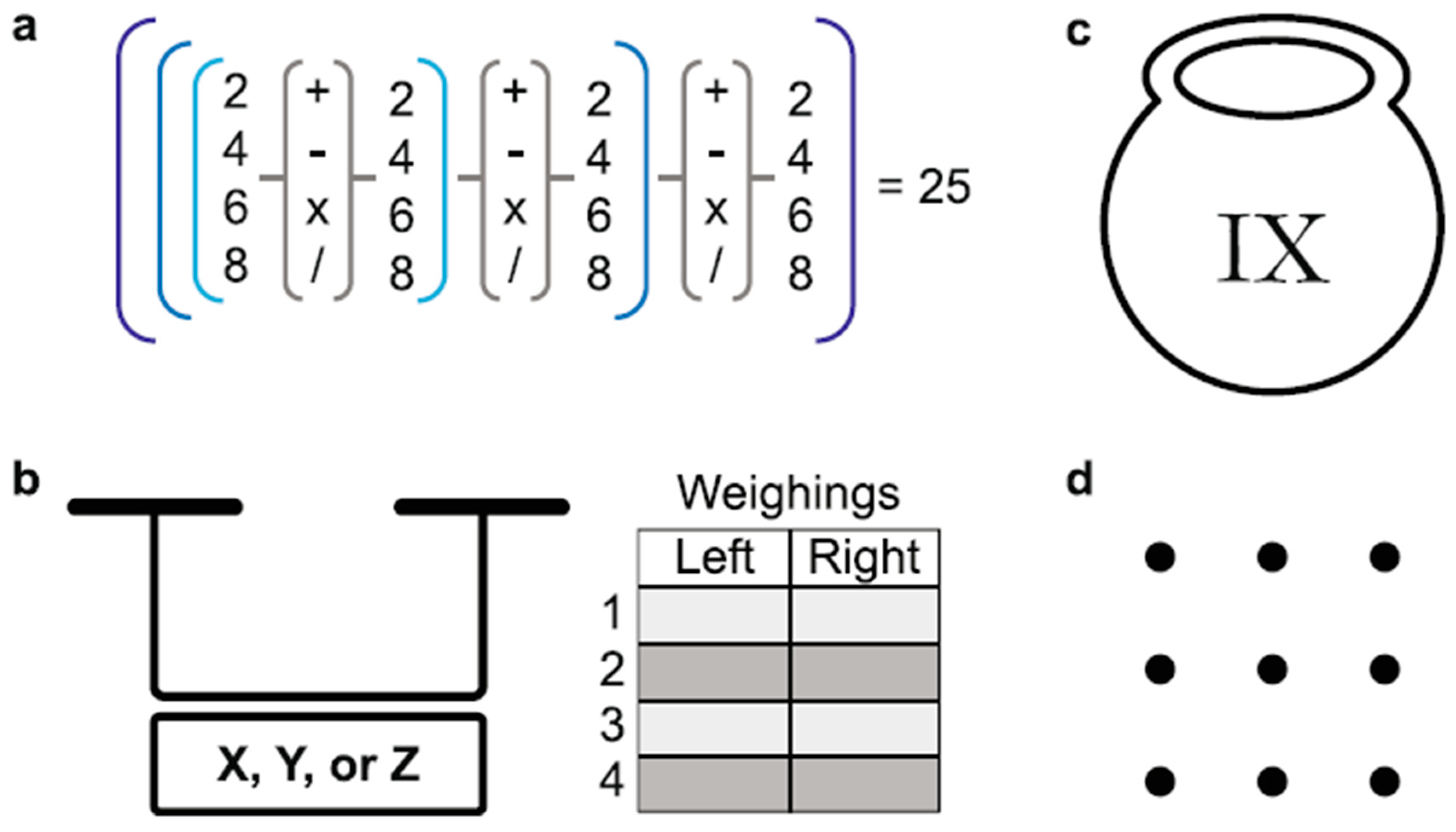

Figure 1 (c.f., [

1]) visualizes how solving puzzles, like brain teasers or jigsaw puzzles, can be compared to analyzing observations and data in a scientific context, showcasings the process of problem-solving, where challenges may seem difficult until the solution is found, leading to a sense of clarity and understanding. Different types of puzzles, such as jigsaw puzzles or logical puzzles, provide varying levels of complexity and require different approaches to arrive at solutions.

To obtain the number 25 by combining the numbers 2, 4, 6, and 8 with three different operations out of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, you need to strategically use these operations to manipulate the numbers [

1]. This mathematical jigsaw puzzle challenges you to find a sequence of operations that [

1], when applied to the given numbers, results in the target number 25. It requires logical thinking and experimentation with different combinations to arrive at the correct solution.

Some puzzles can be solved through brute force by trying out all possible combinations [

1], which becomes more challenging as the scale of the puzzle increases. In the second class of puzzles, known as logical puzzles or brain-teasers, the solution requires a logical leap and often involves the use of mathematical tricks to arrive at the correct answer. An example provided is a logical riddle involving finding a unique coin with a different weight using a digital balance scale in only four weighings, as depicted by

Figure 1b.

In the given scenario [

1], you have 12 coins where 11 are of equal weight, and one coin is either heavier or lighter. Using a digital balance scale that provides three symbols for comparison results [

1], you can identify the odd coin with only 4 weighings. By strategically dividing the coins into groups and comparing their weights [

1], you can deduce the unique coin based on the outcomes of the weighings, allowing you to solve the puzzle efficiently.

In closed-world puzzles [

1], the solution components and their connections are known beforehand, requiring assembly in a meaningful way. In contrast [

1], open-world puzzles lack crucial information for the solution within the given context, necessitating connections to external realms for resolution. The third class of puzzles involves making connections beyond the problem’s initial framework to find a solution, as portrayed by

Figure 1c.

In the given scenario [

1], the girl can add an “O” to the Roman numerals “IX” on the pot, changing it to “X,” which represents the number ten. This way [

1], the altered label will still be correct even after three meatballs are eaten, ensuring that her grandfather does not suspect any discrepancy. The solution involves creatively modifying the existing label to maintain accuracy despite the change in the number of meatballs, as illustrated by

Figure 1d.

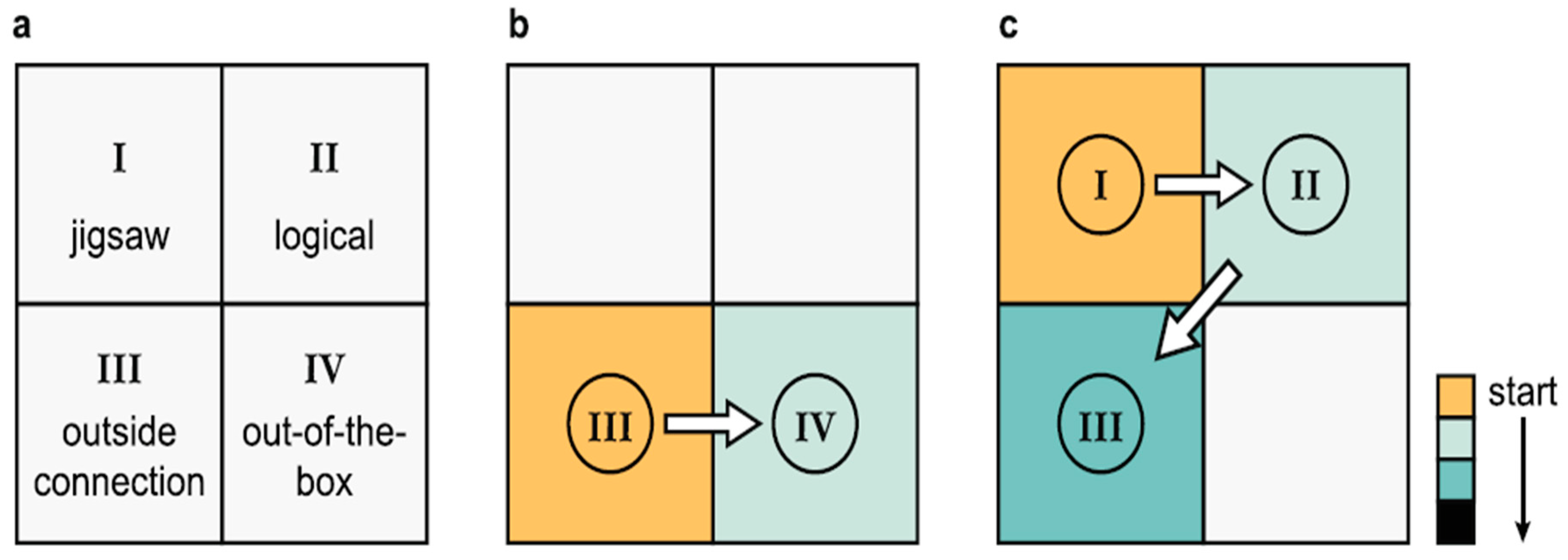

Henceforth [

1], it can be showcased how scientific problems can be categorized into four puzzle archetypes based on two dimensions: closed-world (Classes I and II) versus open-world (Classes III and IV), and finding connections (Classes I and III) versus reframing the problem (Classes II and IV). Understanding where a problem falls on this grid helps identify the type of puzzle being tackled in scientific research, whether it involves following established protocols (Class I), logical reasoning (Class II), making connections (Class III), or thinking creatively (Class IV).

In a humble attempt to discuss different classes of scientific puzzles based on the nature of the problem-solving process [

1], we arrive at this justified counter argument. Class I puzzles involve following established protocols to solve tasks like determining protein structures or assembling genomes. Class II puzzles, exemplified by Crick’s work on the genetic code, involve logical reasoning within defined constraints. Class III puzzles, like Gödel’s work in mathematics, focus on making connections between different areas of knowledge to solve complex problems.

Based on the provided argument [

1], problem-solving is a crucial aspect of scientific training, presenting challenges akin to puzzles for students, highlighting the fact that science is a meta-puzzle, justifying the distinction between closed-world educational puzzles, based on known facts, and the dynamic nature of real-time scientific problem-solving where the puzzle class may not be immediately clear. Scientists [

1] must not only solve the specific puzzle at hand but also navigate the meta-puzzle of determining the type of problem they are dealing with, akin to an outer loop in algorithmic terms.

In the given context [

1], there comes an elegant debate on the shift of focus from gene duplication and alternative splicing processes to other gene properties to gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between them, leading to a reclassification of the research problem from a Class III to a Class IV puzzle, as shown by

Figure 2 (c.f., [

1]).

Having explored that [

1], there are two research projects where shifts between different types of puzzles occurred during the investigation. In one project [

1], the authors explored the relationship between gene duplication and alternative splicing, initially considering it a Class III puzzle but later realizing it was a Class IV puzzle due to insights gained from gene properties. In another project [

1],using deep learning to predict enzyme substrate scope, the authors encountered challenges with accuracy, leading them to modify the problem into a Class III puzzle and incorporate methods from natural language processing to improve predictions.

Talking more mathematics [

2], pure Mathematics encompasses propositions of the form “

,” where

and

are statements involving variables and logical constants. These propositions do not contain any constants except logical ones. Mathematical reasoning involves concepts like implication [

2], relations, and truth, aiming to provide precise analysis and justification for mathematical ideas and theories.

The definition and justification of pure mathematics [

2], aims to provide a precise analysis of the ideas implied in the term, emphasizing the transition from complex to simple concepts and the reliance on mathematical certainty to address fundamental questions about number, infinity, space, time, and mathematical reasoning. The approach [

2] involves reducing these questions to problems in pure logic, highlighting the intersection between mathematics and philosophy in seeking clarity and exact knowledge.

Discussing the historical controversy surrounding the philosophy of mathematics [

2], where philosophers debated the true meaning of mathematical propositions, would unarguably demostrate the shift towards using fundamental logical notions to formalize mathematical reasoning, aiming to provide certainty and exact knowledge in mathematics. This approach seeks to address philosophical questions about the meaning and foundations of mathematics by grounding it in logic and formal deduction.

In pursuit of the historical challenges in applying deductive reasoning to mathematics due to the limitations of traditional logical systems like Aristotelian syllogistic theory and Symbolic Logic [

2], it can be showcased that the evolution of Symbolic Logic, particularly through the work of Professor Peano, which has enabled a more formal and comprehensive deduction of mathematical principles. This advancement refutes the Kantian philosophy that mathematical reasoning relies on intuition, emphasizing that all mathematics can be deduced from logical principles, leading to the understanding that mathematics is essentially Symbolic Logic.

In view of how all mathematics is deduced from logical principles [

2], as advocated by Leibniz, emphasizing the need to prove axioms and define fundamental notions, we can reason the distinction between pure mathematics, which deals with logical implications, and applied mathematics, which involves assigning constant values to variables to assert both hypothesis and consequent. This underscores that pure mathematics focuses on logical implications [

2], such as the relationship between Euclidean axioms and propositions, while questions about the physical world fall under empirical science and applied mathematics.

In mathematics [

2], propositions involve variables that can represent different entities or values. Even in seemingly simple arithmetic statements like

, variables are present, implying conditions like “If x is one and y is one, then x and y are two.” The use of variables and formal implications is fundamental in mathematical propositions [

2], where the words “any” or “some” indicate the presence of variables and the assertion of implications based on different values assigned to these variables.

In mathematics [

2], variables are typically associated with specific classes, like numbers in Arithmetic. However, the concept of variables extends beyond these classes. Even if variables are not numbers [

2], the implications of mathematical propositions remain valid when different entities are substituted for them, showcasing the flexibility and generality of mathematical reasoning.

Coming to explain the concept of generalization in mathematics [

2], where constants in propositions are transformed into variables to capture the essence of a statement, we arrive to a stage where to decide that, by turning constants into variables, mathematics focuses on types of propositions rather than specific instances, ensuring the validity of statements across different scenarios. This process [

2] allows for the formulation of pure mathematical propositions based on logical constants and variables, enhancing the generality and applicability of mathematical reasoning.

The connection between mathematics and logic is very close [

2], as all mathematical constants are also logical constants. This relationship implies that once the principles of logic are accepted [

2], all of mathematics logically follows. While the distinction between mathematics and logic can be somewhat arbitrary, mathematics involves the consequences of premisses that assert formal implications with variables [

2], while logic includes premisses related exclusively to logical constants and variables.

The current paper contributes to:

Showcasing the great impact of employing puzzles to influentially tecah mathematics.

The provision of emerging open problems to widen the scope of the existing knowledge into both theoretical and practical frameworks to develop the practice a higher up level.

The paper is portrayed by the following schematic:

II. Crafting of Puzzle-Led Approach to Teaching Mathematics

The authors [

3] aimed to enhance mathematics learning outcomes for third-grade students by implementing the STAD cooperative learning model with puzzle media on measuring angles. Through classroom action research conducted in multiple cycles, improvements in student activity, responses, and learning outcomes were observed, with significant increases in student engagement and success rates demonstrated through data analysis methods such as percentage of classical completeness and observations. The results [

3] indicated a positive impact on student activity, responses, and academic performance, highlighting the effectiveness of the applied teaching approach in enhancing mathematical understanding among the students.

In the provided line enquiry [

3], the importance of effective mathematics education in Grade 3 is emphasized, highlighting the transition from basic number comprehension to more abstract concepts like angle measurement. Innovative teaching strategies, such as integrating puzzles and collaborative learning models like STAD [

3], are suggested to enhance student engagement and understanding of geometric concepts, addressing the challenges students face in visualizing angles and grasping abstract mathematical ideas at a young age. These approaches aim to cultivate a strong mathematical foundation and foster a positive attitude towards mathematics among elementary school students.

Thinking deeply of an action research study that aims to assess the impact of integrating puzzle-based learning activities and the STAD model in teaching angle measurement to third-grade students., the authors seek [

3] to evaluate how these innovative teaching methods influence academic performance, engagement levels, problem-solving skills, and student attitudes towards mathematics, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. By combining hands-on puzzle activities with collaborative learning approaches, the research aims to enhance elementary mathematics education outcomes and provide valuable insights into effective teaching strategies.

The action research study [

3] has integrated puzzles and the STAD model to teach angle measurement to third-grade students, showing a significant improvement in student understanding and engagement. The results indicated a substantial increase in completeness percentage from 57.1% to 82.8% across two cycles, supporting the hypothesis that this combined approach enhances academic performance in mathematics education. The study’s findings [

3] suggested that integrating puzzle-based learning with cooperative models like STAD can positively impact student learning outcomes and engagement in elementary mathematics education.

On another different note, [

4] has explored the challenges Artificial Intelligence (AI) faces in solving mathematical puzzles with diagrams, highlighting the need for reasoning techniques like logic programming. The study [

4] has interestingly used Prolog reasoning to analyze puzzle diagrams and integrate spatial reasoning into the solving process, aiming to develop a library that can autonomously solve problems presented in a textual-graphical format, potentially enhancing human-machine interactions.

In the context of the study [

4] on teaching angle measurement to elementary school third graders, an example of a math puzzle with a diagram could involve a geometric problem where students need to determine angles within a shape or between intersecting lines. This type of puzzle-based activity aims to engage students in creative problem-solving [

4], deepen their understanding of geometric concepts, and enhance their academic performance and engagement in mathematics. By integrating such puzzles with collaborative learning methods like the STAD model [

4], educators can create interactive and student-centered approaches to improve learning outcomes in elementary mathematics education, as depicted in

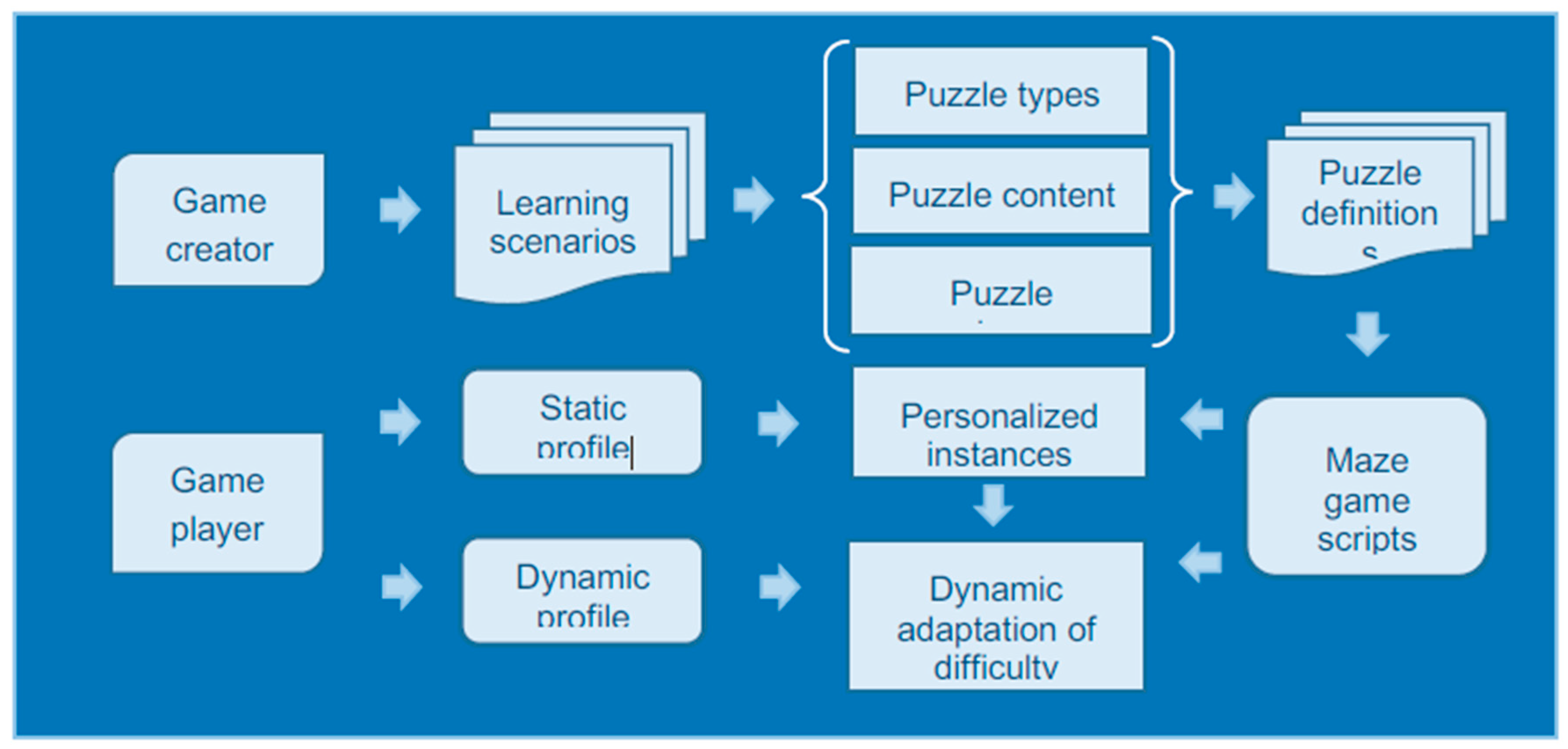

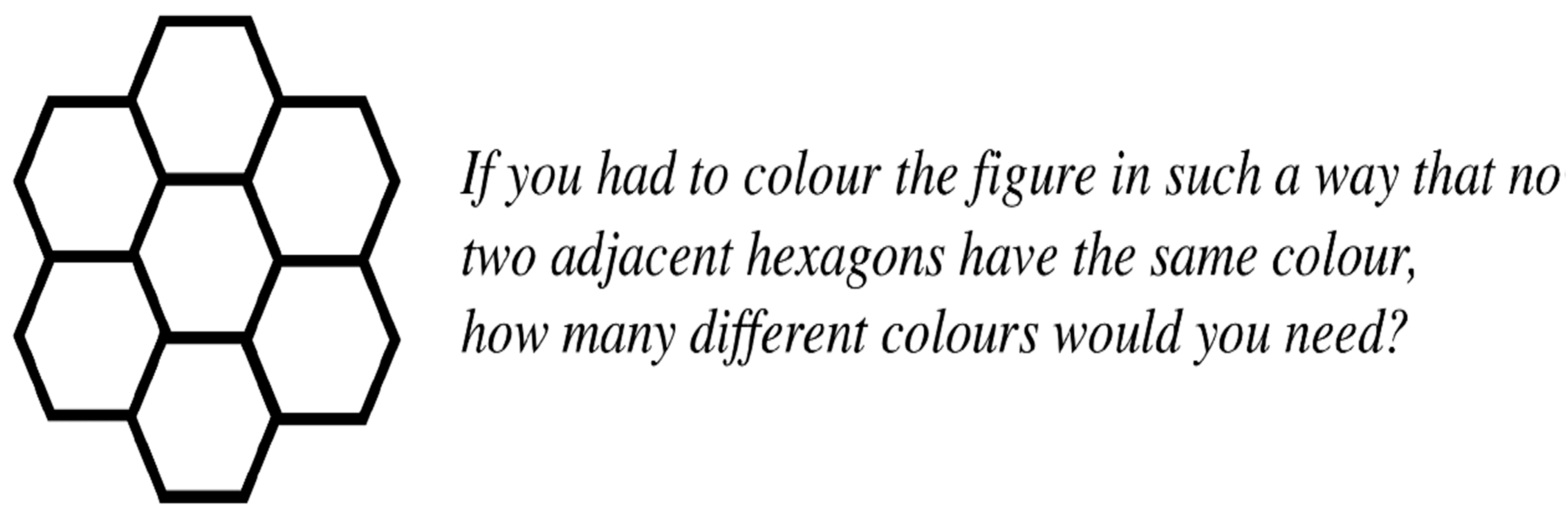

Figure 3 (c.f., [

4]).

Based on that, [

4], the use of AI in solving puzzles, particularly focusing on logical and mathematical puzzles presented in natural language or graphical form, would introduceVarious approaches, such as declarative logic-based languages like Prolog and Probabilistic Inductive Logic Programming (PILP), are explored to tackle different types of puzzles. These methods aim [

4] to enhance AI’s ability to autonomously solve complex puzzles by combining logical inference with statistical reasoning, highlighting the importance of spatial reasoning and logic in puzzle-solving tasks.

On the other side of the argument [

4], various research works related to using analogy reasoning, spatiotemporal reasoning, and neural networks in solving physics questions with texts and diagrams, were successfully explored. These works aim to improve systems’ abilities to reason, answer questions, and interpret information from different modalities like text and images, showcasing advancements in the field of Visual Question Answering (VQA) and multimodal approaches for educational purposes, particularly in primary school settings. The research highlights the importance of combining different methodologies to enhance learning outcomes and address challenges in reasoning and answering complex questions in educational contexts.

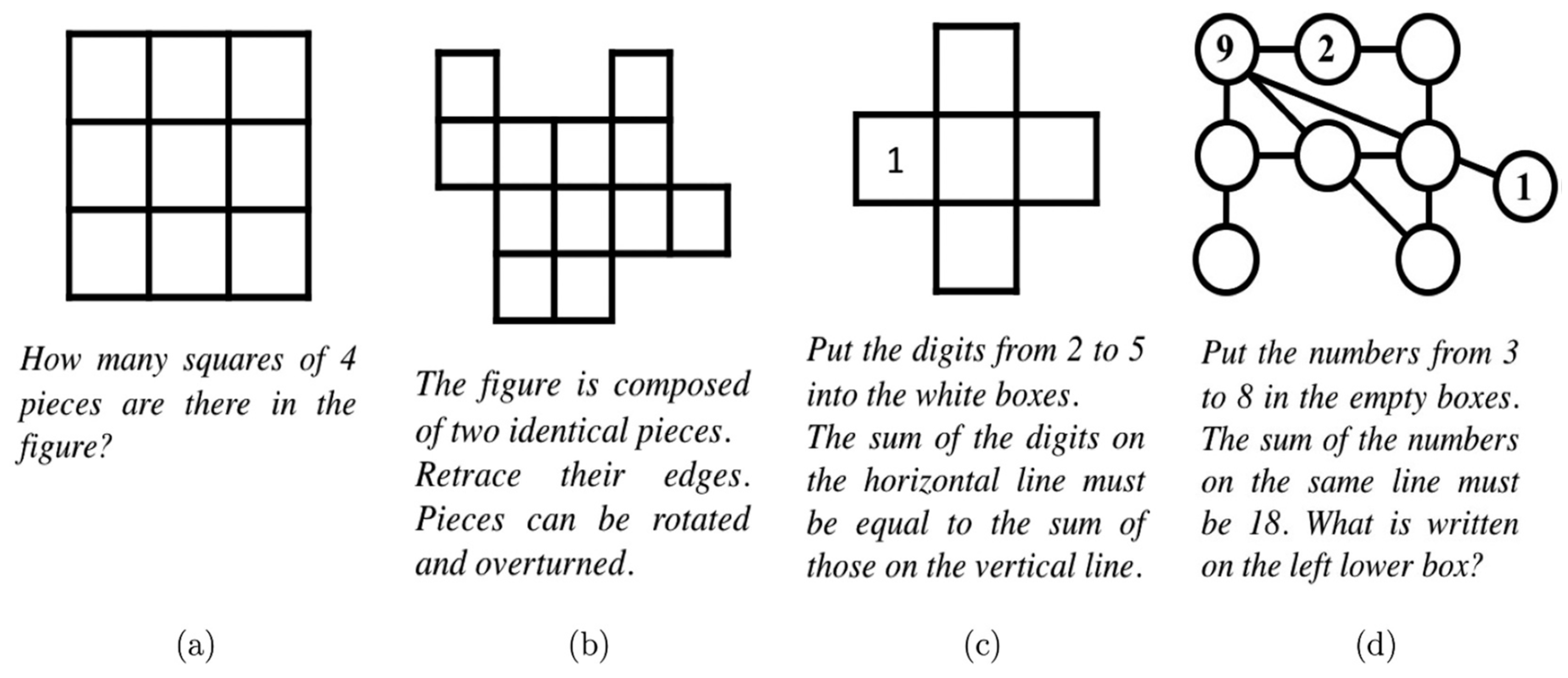

Figure 4 (c.f., [

4]) refers to various math puzzles categorized into numbers in a diagram, geometrical figures, and spatial logic [

4], as represented in the PRISTEM Research Centre catalogue. These puzzles are visual representations that can aid in teaching mathematical concepts effectively, especially when integrated with interactive teaching methods like the STAD model [

4], as discussed in the context of the study. Such visual puzzles can enhance student engagement and learning outcomes in mathematics education.

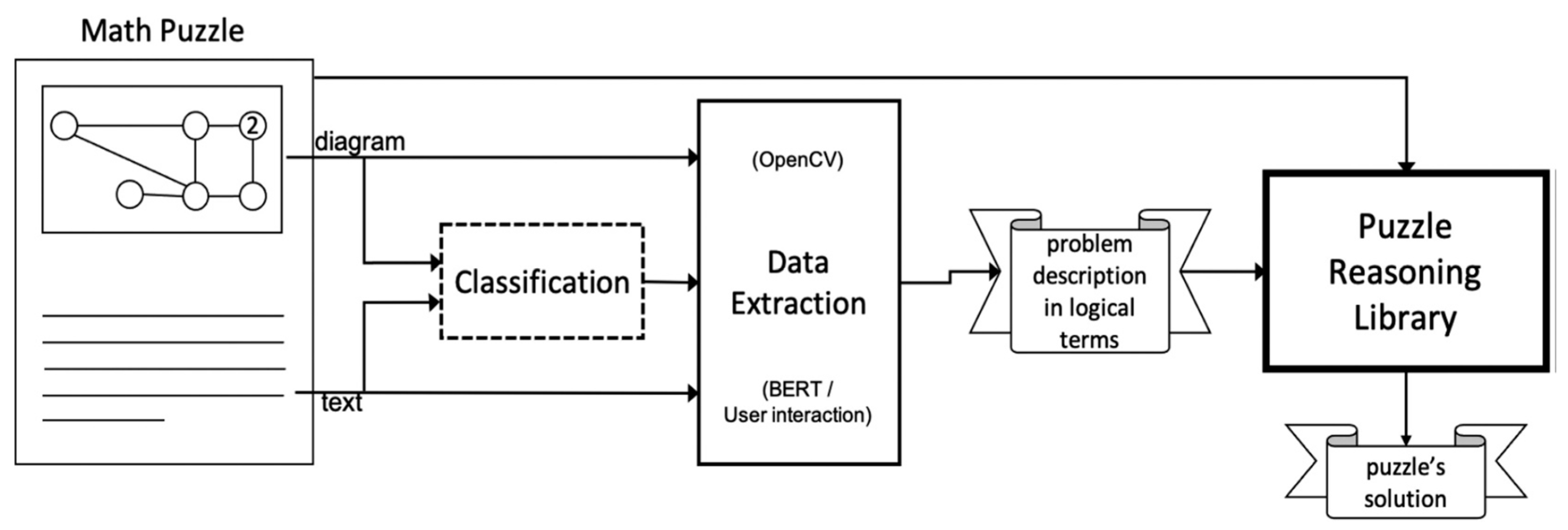

In reference to a system that is designed to process both textual and graphical information describing a puzzle, the framework of this system is illustrated in

Figure 5 (c.f., [

4]), indicating a visual representation of how the system operates. This approach [

4] likely aims to enhance understanding and problem-solving capabilities related to puzzles by integrating both textual and visual elements.

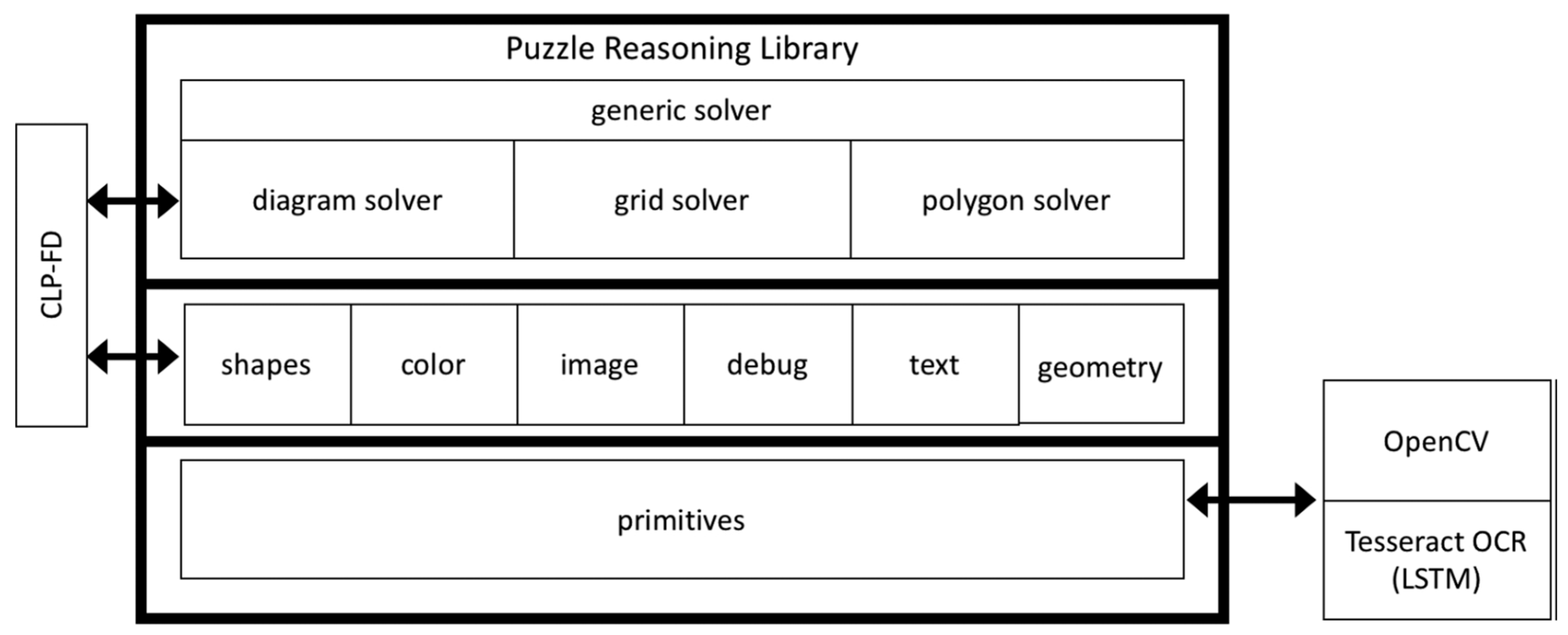

The Puzzle Reasoning Library [

4] utilizes image analysis and logical reasoning to interpret diagrams based on problem descriptions provided by the Data Extraction module. It employs a low-level layer [

4], called the primitives module, which uses functions written in C++ and OpenCV library to identify key elements like points [

4], segments, shapes, and text/numbers within the diagrams. OpenCV is chosen for its reputation as a widely-used open-source computer vision library with a broad range of applications and efficient performance capabilities, as visualized by

Figure 6 (c.f., [

4]).

Figure 7 (c.f., [

4]) describes a web-based application where users can interact with a spatial reasoning framework by solving puzzles. Users can select from fifteen puzzles [

4], view their descriptions, and see the Prolog translation of the problem. By pressing the ‘Solve’ button [

4], the application processes the selected puzzle and Prolog query using a Prolog interpreter on the server, displaying the output in the SWIPL Console area and showing solutions on the Output image area.

The quality of the system outcomes is influenced by various factors [

4], such as image quality affecting the OpenCV library’s edge detection, where artifacts or low resolution can lead to false conclusions. Additionally, variability in puzzle descriptions impacts data extraction, especially when dealing with translations and the limitations of Natural Language Processing tools for different languages like Italian and English. Despite the potential of Deep Learning, the small dataset of mathematical puzzles poses challenges for training algorithms and fine-tuning neural networks effectively.

Following the discussion of the use of logic programming [

4], specifically Prolog and the CLP(FD) library, to manage the complexity of solving puzzles that require a multimodal approach, would equally spotlights the development of a decision tree to aid in data extraction and problem-solving, emphasizing the potential of AI tools to support human problem-solving processes, especially in educational settings. Additionally [

4], it addresses the need for further advancements in image recognition techniques to enhance the library’s capability to handle a broader range of puzzle types, such as crypto-arithmetic games.

Unarguably [

5], the importance of fostering students’ creative thinking skills in mathematics by providing opportunities for them to develop new ideas and think creatively, would predominantly steer a study on seventh-grade students’ mathematical creative thinking abilities, emphasizing the need for educators to focus on nurturing creative problem-solving skills rather than solely assessing learning outcomes. The research findings [

5] suggested that there is room for improvement in enhancing students’ creative thinking abilities in mathematics education.

Figure 8 (c.f., [

5]) describes a study where students were given math puzzles involving shapes, with only 10% successfully solving them by creating different shapes with the same area. The remaining 90% struggled and could not create alternative shapes [

5], indicating low creative thinking ability possibly due to the teacher’s focus on assessing learning outcomes rather than nurturing mathematical creative thinking skills.

Figure 9 (c.f., [

5]) offers a descriptor for a puzzle game called “Hatching the Egg” that aims to enhance students’ creative thinking skills in mathematics learning. By arranging egg pieces to form bird shapes, students are challenged to concentrate, imagine shapes, and enhance their understanding of geometry. This game [

5] serves as a fun and engaging method to stimulate students’ thinking skills and promote mathematical creativity. The objective [

5] is to create bird shapes from the egg pieces and identify as many bird shapes as possible. This puzzle game serves as a hands-on activity to engage students in spatial reasoning and problem-solving within a mathematical context.

The findings of the research [

5] involve developing a geometry puzzle game to enhance junior high school students’ mathematical creative thinking ability. The research followed a 4-D model for research and development, focusing on the Development stage [

5], which included stages such as defining needs, conducting front-end analysis, learner analysis, and concept analysis to tailor the learning media to meet student needs and improve learning outcomes in geometry.

During the design stage [

5], a researcher creates a Criterion-Referenced Test to assess students’ mathematical creative thinking ability using five questions. This test is developed based on core competencies and syllabus indicators, aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of the learning media being designed. The test is crucial for measuring student understanding and ensuring the quality of the educational materials.

Field trials [

5] were conducted to assess the effectiveness of a geometry puzzle game in teaching mathematics. The post-test results showed a high level of classical completeness at 75.86%, indicating that the game effectively enhances students’ creative thinking skills in mathematics. This aligns with previous research demonstrating that puzzle-based learning media can be valuable tools for improving student learning outcomes in mathematics classrooms.

The community service activity [

6] described aims to address challenges faced by teachers at Pesisir Elementary School in cultivating students’ interest in mathematics through the use of Puzzle Straw teaching aids. These aids involve arranging straws to create puzzles [

6], enhancing students’ engagement and understanding of geometric concepts. The results show increased student enthusiasm [

6], improved teacher engagement, and enhanced knowledge of elementary mathematics concepts, particularly in spatial geometry, highlighting the effectiveness of this interactive teaching approach.

The lack of facilities and extracurricular activities [

6] can impact children’s learning and academic performance. To address this issue [

6], the principal of Pesisir Elementary School requested training and mentoring for teachers to develop mathematical teaching aids. This initiative involved implementing the Puzzle Straw method in mathematics learning to enhance students’ understanding of concepts and support teachers in improving their teaching practices.

In the provided

Figure 10 (c.f., [

6]), “Servant makes observations” refers to the role of the service provider or facilitator who conducts observations during a community service activity aimed at enhancing teachers’ understanding of using Puzzle Straw mathematics teaching aids. The observations are made to monitor and assess [

6] the participants’ engagement and the effectiveness of the teaching aids in improving mathematics learning at Pesisir Elementary School. The data collected through these observations is then processed quantitatively and presented descriptively to evaluate the impact of the program.

Using mathematical teaching aids like Puzzle Straw in teaching geometric shapes at the elementary school level offers several benefits [

6], can attract students’ attention and motivation by providing a creative and interactive learning experience, make spatial geometric concepts clearer and easier to understand, allow for varied teaching strategies to prevent boredom, support various learning activities, and engage students’ five senses in exploring geometric concepts, aligning with the concrete thinking stage of elementary school students.

As illustrated by

Figure 11(c.f., [

6]), the Puzzle Straw props for geometric shapes are mathematical teaching aids that offer several benefits in elementary school education. These props attract attention and motivation, clarify spatial geometric concepts, provide variations in learning strategies, support various learning activities, and engage students’ five senses in exploring geometric shapes, enhancing their understanding through hands-on experiences.

In the given

Figure 12 (c.f.,[

6]), the “The teacher applies the Straw Puzzle props in class” indicates that the teacher is using Straw Puzzle teaching aids during lessons on geometric shapes. This approach has been found effective in enhancing students’ interest in learning mathematics [

6], improving teacher engagement, and deepening teachers’ understanding of spatial geometry concepts in elementary school education. The use of these props allows for hands-on exploration of geometric concepts [

6], fostering active learning and better comprehension among students and teachers alike.

The application of Puzzle Straw teaching aids in learning geometric shapes in elementary school classrooms has been successful [

6], leading to increased student interest, teacher enthusiasm, and improved understanding of spatial geometry concepts. Feedback from principals [

6], teachers, and students indicates the effectiveness of these teaching aids in enhancing the learning experience and knowledge of elementary school mathematics concepts, particularly spatial geometry. The interactive nature [

6] of the Puzzle Straw aids allows students to explore geometric shapes directly, fostering a deeper understanding of the subject.

The study [

7] aims to explain how project-based learning was implemented and assess the enhancement of students’ creativity in learning media. By observing the implementation of project-based learning over a semester and evaluating students’ work [

7], the study found improvements in students’ creativity, particularly in terms of flexibility and novelty, although originality showed moderate progress. The research [

7] used a descriptive-qualitative method involving students from a learning media course to analyze the impact of project-based learning on creativity.

Project-Based Learning (PjBL) is a suitable model for creating learning media in mathematics education, encouraging collaboration, application of prior knowledge [

7], and skill development among students. PjBL benefits include enhancing students’ abilities, improving achievement, fostering problem-solving skills, promoting collaboration, motivating students, and catering to diverse learning styles. By engaging in PjBL [

7], students can showcase their creativity through various projects, enhancing their knowledge and skills in mathematics education.

The the use of project planning activities involving storyboarding to enhance students’ ability to design learning media [

7], was conducted. By following a structured format including key elements like main material, competencies, and learning indicators, students can develop their ideas and improve their designs based on literature and additional insights gained during the process. This approach fosters creativity [

7], critical thinking, and adaptability in students’ learning experiences.

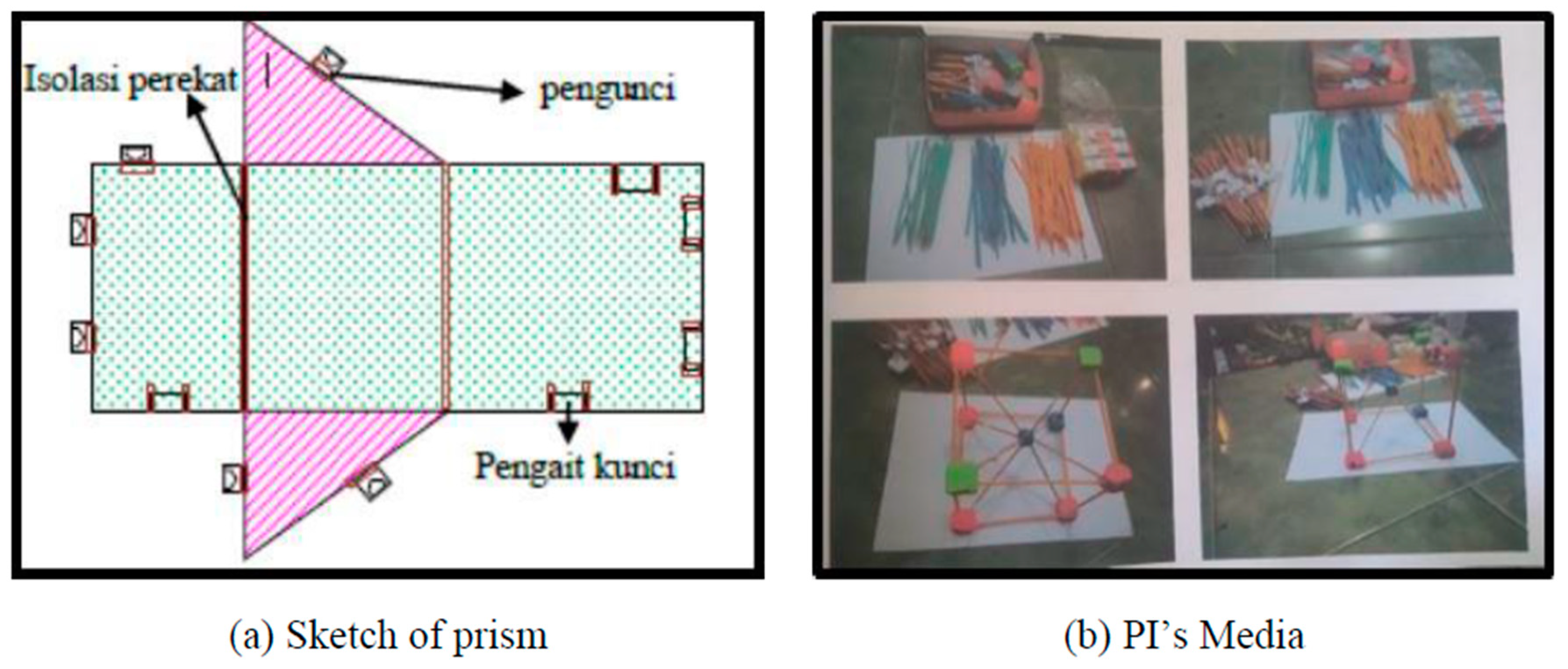

In the given context [

7], the text describes how students transformed their initial idea of creating learning media for space geometry into trigonometric puzzles during the design process. This shift in media design showcases the students’ creative thinking and adaptability in incorporating trigonometry concepts into their educational materials, as depicted in the storyboard drawings and early sketches presented in

Figure 13 (c.f., [

7]).

Figure 14 (c.f., [

7]) describes the use of different materials, such as paper beams and pipes, to create bar charts as learning aids in mathematics. While paper beams are more interactive but less durable, the use of such manipulatives enhances students’ engagement and understanding of mathematical concepts, encouraging creativity and flexibility in learning approaches. The results show that students’ ability to create interactive learning media has significantly improved, allowing for a more dynamic and engaging learning environment in mathematics education.

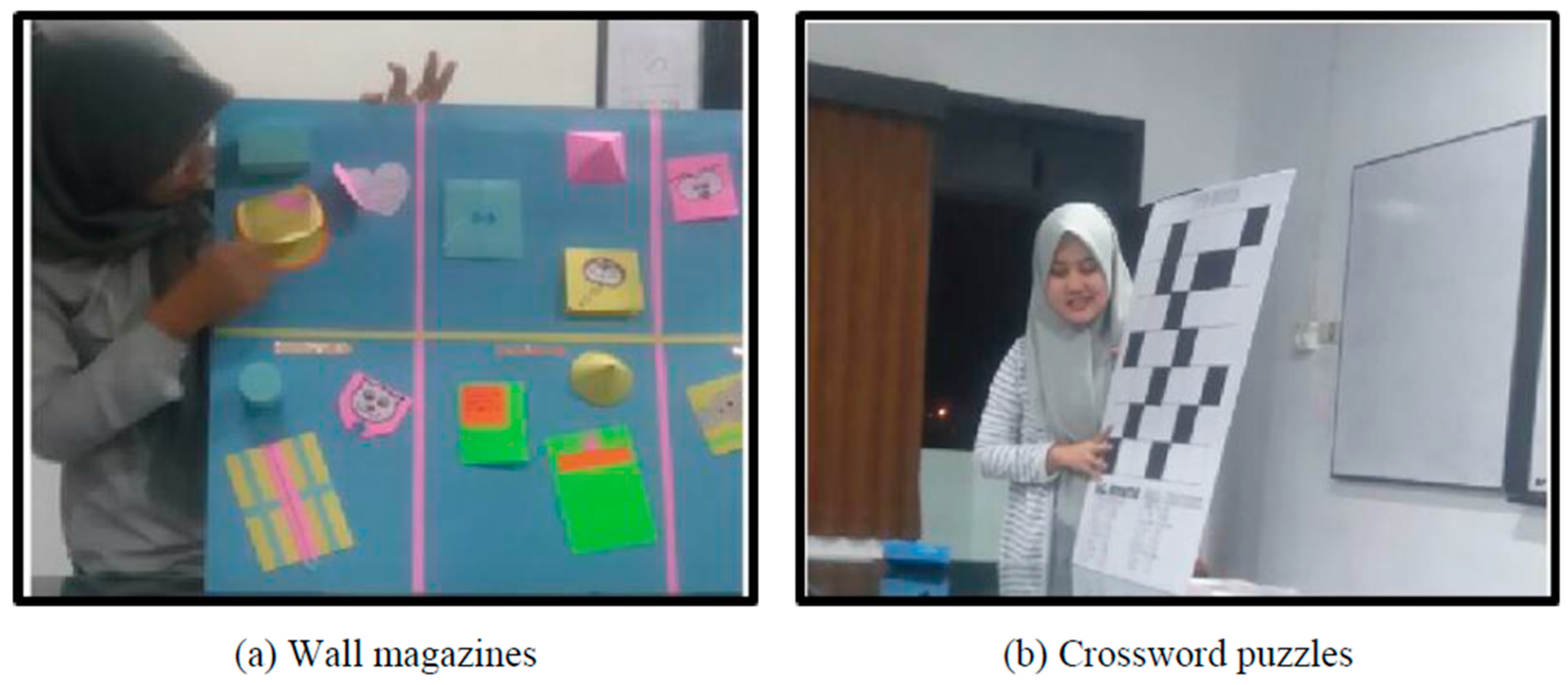

The positive impact of using innovative teaching aids [

7], such as Straw Puzzle props, in mathematics education to enhance students’ engagement and understanding of concepts, was successfully highlighted. By incorporating creative learning materials like wall magazines or crossword puzzles [

7], teachers can foster a dynamic and enjoyable learning environment, ultimately improving students’ motivation, comprehension, and critical thinking skills. This emphasis on original and interactive teaching methods underscores the importance of continuous guidance and support for educators to enhance their instructional practices.

The distinction between the design and actual implementation of educational media, is depicted in

Figure 15 (c.f., [

7]). This suggests that there may be variations or discrepancies between the planned design of teaching materials and how they are actually used in practice, highlighting the importance of aligning instructional design with real-world application for effective educational outcomes.

The adaptation of wall magazines and crossword puzzles to teach spatial geometry concepts in elementary school mathematics is described by

Figure 16 (c.f., [

7]). By modifying the rules of crossword puzzles to focus on spatial geometry issues, teachers can engage students in exploring geometric concepts interactively. This approach enhances student enthusiasm for learning mathematics and helps teachers improve their knowledge and understanding of spatial geometry concepts through interactive teaching aids.

The results of implementing project-based learning [

7] to enhance students’ creativity in creating mathematics learning media showed significant improvements in originality and flexibility aspects. Students demonstrated increased creativity by developing diverse learning materials [

7], although some still relied on existing formats. Overall, the project led to positive outcomes in fostering students’ creativity in designing mathematics learning media.

The goal of the project [

8] is to apply puzzle learning models to help fourth grade students at Gebang Elementary School 1 Sidoarjo, Indonesia, surpass their learning objectives in mathematics courses involving polygons. Planning, action, observation, and reflection are the four primary steps in each cycle of the study, which uses the Class Room Action research technique and Kurt Lewin learning problems as a model. Observations and tests are used to collect data. The findings demonstrated that using the puzzle learning model in mathematics classes using polygon material can raise students’ achievement criteria for the learning process between students and teachers to be classified as “very effective,” with scores in the fourth grade at Gebang Elementary School 1 Sidoarjo, Indonesia, improving by up to 86%.

It is quite important to enhance students’ logical thinking through subjects like Discrete Mathematics and Discrete Methods and Optimization [

10], which involve graph theory and combinatorial optimization. These mathematical disciplines help teachers develop students’ logical thinking [

10], increase their problem-solving skills, and enable them to apply their knowledge to practical situations by using graphs to represent and solve problems effectively. Engaging students with practical tasks and puzzles related to these subjects can further enhance their understanding and application of logical thinking concepts.

Coming to the historical connection between graph theory and puzzles [

10], would consolidate how seemingly trivial puzzles led to the development of graph theory as a rich subject with diverse theoretical results. The book “Graph Theory 1736 – 1936” by Biggs, Lloyd, and Wilson introduces important problems in graph theory from 1736 to 1936, showcasing the significance of puzzles in inspiring mathematical exploration and innovation. This historical perspective [

10] underscores the practical relevance and intellectual appeal of graph theory through engaging puzzles and challenges.

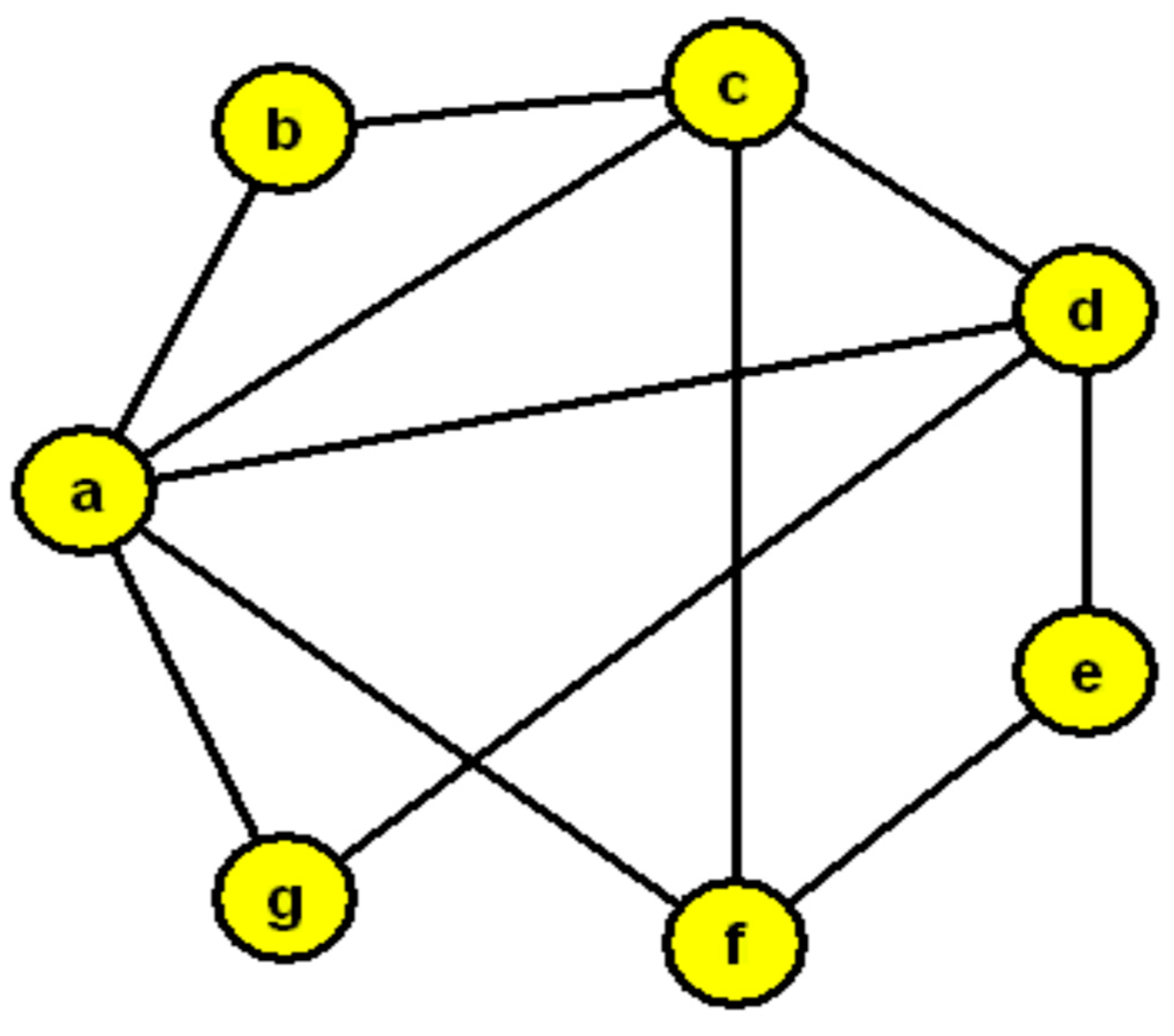

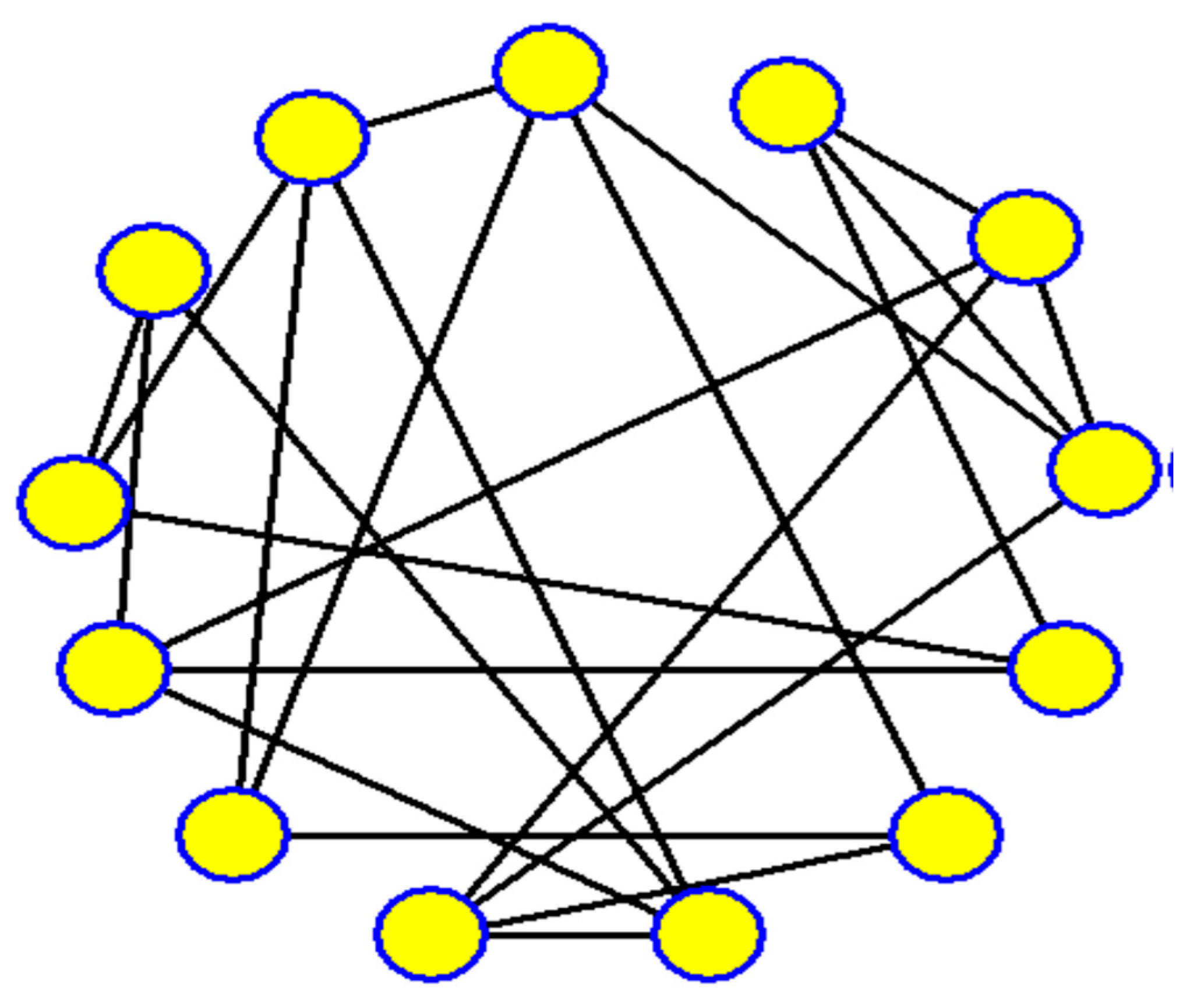

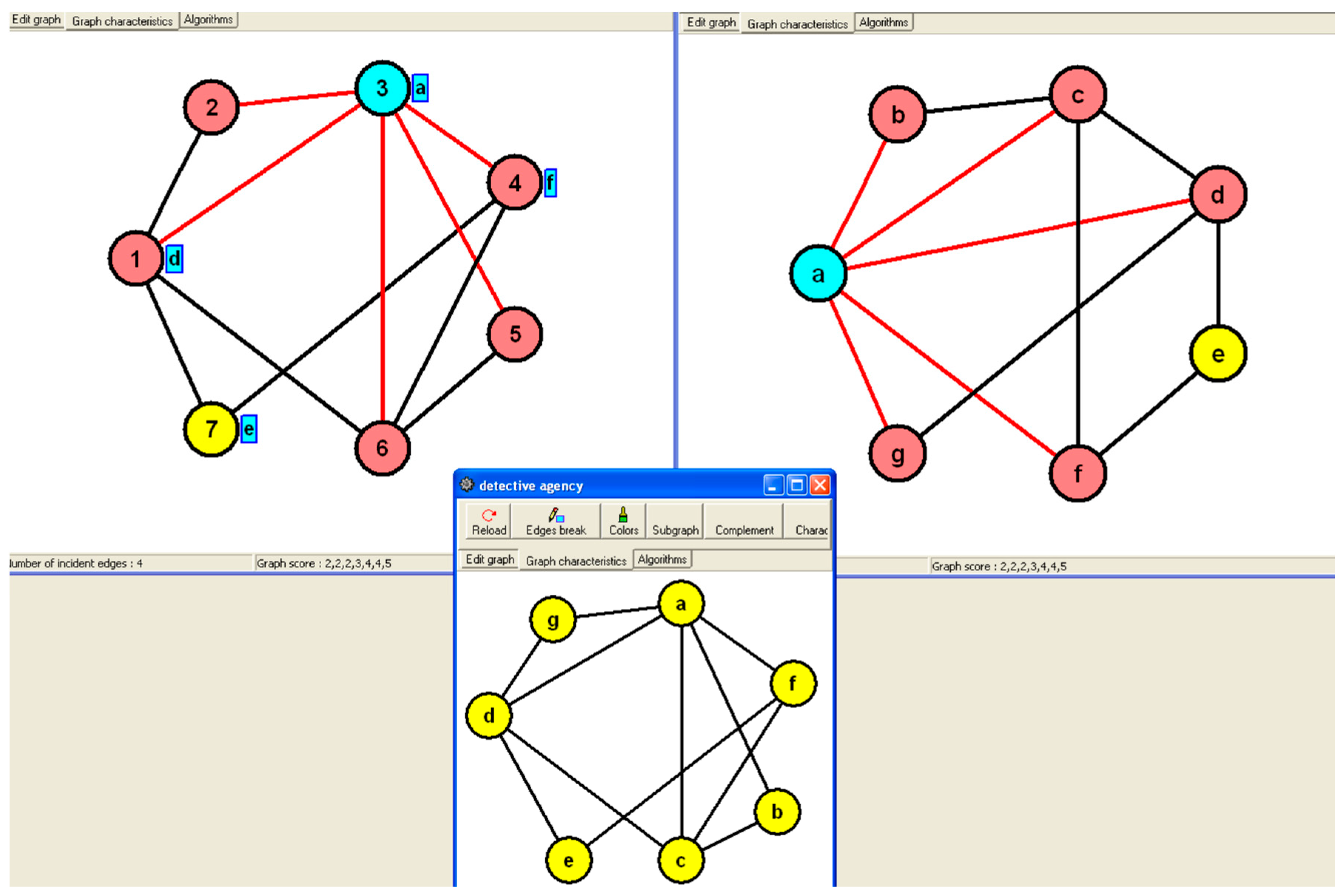

In the given scenario, two detectives used graph representations to depict relationships among individuals they were investigating, with one detective using letters and the other using numbers to represent people. The task is to determine the connection between the graph representations created by the two detectives, which involves finding the isomorphism between the graphs shown in

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 (c.f., [

10]). Isomorphism is a fundamental concept in graph theory that involves establishing a correspondence between the vertices and edges of two graphs while preserving their structural properties.

Figure 17 in the context refers to a visual representation of the relationships between individuals using letters to denote people and connecting lines to show who knows each other. This graph serves as a puzzle to be solved by finding the isomorphism, which is a fundamental concept in graph theory that involves determining if two graphs are structurally equivalent despite differences in labeling or representation methods. The task involves identifying the connection between the first detective’s graph-representation and the second detective’s graph-representation using isomorphism.

The second detective's graph-representation in the context refers to a visual representation of the relationships between individuals in a group, where each person is denoted by a number. The task involves finding the connection or isomorphism between the graphs created by the first and second detectives, which essentially means identifying if the structures of the two graphs are the same despite using different labels (letters and numbers) for the individuals. This puzzle serves as an example to motivate the concept of isomorphism in graph theory, which is a fundamental concept explained in textbooks on the subject.

In the context provided [

10], the text refers to a puzzle involving 13 pins connected by strings whose positions have been altered. The task is to determine the original arrangement of the pins based on the new configuration shown in

Figure 19 (c.f., [

10]). This puzzle challenges individuals to use logical reasoning and spatial visualization skills to deduce the initial order of the pins from the given rearrangement.

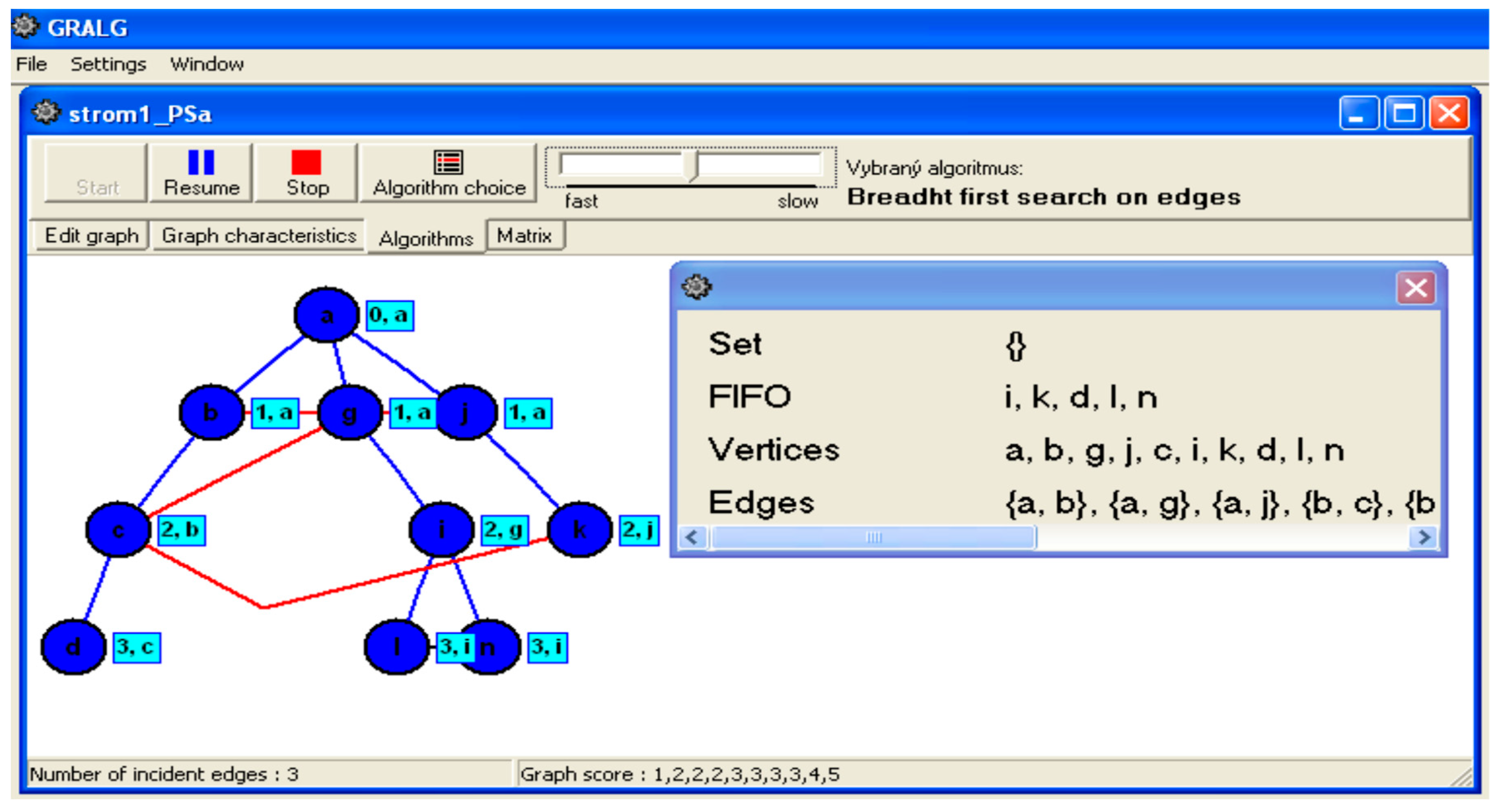

The Program GrAlg provides a visualization of the Breadth-First Search algorithm [

10], allowing users to see the process and data structures clearly. It enables students to compare multiple objects or algorithms simultaneously, facilitating a deeper understanding of the subject matter through interactive exploration of graphs and algorithm properties. This tool not only supports self-study for students but also aids teachers in explaining concepts and algorithms effectively during lectures and seminars, as depicted by

Figure 20 (c.f., [

10]).

Figure 21 (c.f., [

10]) refers to the GrAlg program, which allows students to open multiple windows to compare and solve puzzles related to a detective office scenario. By using this program, students can deepen their understanding of the subject matter by exploring graphs, properties, and running algorithms on them. The ability to save created graphs in bmp format facilitates easy integration into presentations, aiding both student self-study and teacher explanations during lectures and seminars.

To sum uo, the work of [

10] have provided a method to enhance students’ logical thinking and creativity in graph theory and combinatorial optimization through practical tasks and puzzles. By engaging students intensively in their education and encouraging them to apply what they learn in various contexts [

10], their understanding and imagination can be enhanced. The use of multimedia applications and visualization techniques further aids in deepening students’ knowledge and appreciation for the subject matter.

Puzzle categorization involves classifying puzzles based on their characteristics [

10], such as difficulty level, type of problem-solving required, or thematic elements. This process helps organize puzzles for educational purposes and can aid in selecting appropriate challenges for different skill levels or learning objectives. In the context provided, puzzle categorization is used to introduce logical tasks and challenges into educational curricula, enhancing problem-solving skills and engaging students in graph theory concepts through interactive problem-solving activities, as portrayed by

Figure 22 (c.f., [

10]).

The process of puzzle design [

10], personalization, and adaptation involves creating puzzles with specific rules and constraints, such as moving from one point to another while following certain guidelines. In this context, it may include designing puzzles like the one described in the text, where solving involves finding the shortest path using algorithms like Breadth-First Search to navigate through different cells with varying speeds and restrictions. This process requires careful consideration of the puzzle’s structure, rules, and the use of algorithms to optimize the solving strategy.

Figure 23.

The creation, customisation, and adjustment of puzzles.

Figure 23.

The creation, customisation, and adjustment of puzzles.

Based on the study’s findings [

11], it was concluded that games and puzzles used as teaching strategies in Mathematics in Secondary Public Schools in Bauang District can be both effective and ineffective. These strategies were found to make learning enjoyable and interesting, with encountered problems not being severe. The study [

11]recommended implementing intervention measures to enhance Mathematics teaching using games and puzzles, suggesting sustained use and addressing serious issues for improvement.

Based on the research findings [

12], it is recommended that teachers utilize various methods of delivering learning, especially in asynchronous online settings, to enhance students’ math learning competencies. The use of micro-lectures through platforms like ED Puzzle has shown effectiveness in improving students’ understanding, as indicated by a notable improvement in differentiation rules comprehension. By prioritizing student needs and integrating technology thoughtfully, educators can positively impact teaching and learning experiences during the ongoing pandemic, aiding students in achieving their math learning goals.