Submitted:

05 September 2024

Posted:

06 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Macular Pigment Optical Density (MPOD) Measurement

2.2. QuantifEye MPS II

2.3. Zx Pro - A new handheld heterochromatic flicker photometer

2.4. Differences between the MPOD measuring instruments.

2.5. Sample Size Estimation

3. Results

| Mean MPOD1 measurements |

Practice attempt | Study Attempt-1 |

Study Attempt- 2 |

Repeated measures ANOVA p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QuantifEye | 0.441 (0.16) | 0.452 (0.16) | 0.430 (0.14) | 0.015 |

| Zx Pro | 0.459 (0.15) | 0.447 (0.15) | 0.444 (0.15) | 0.325 |

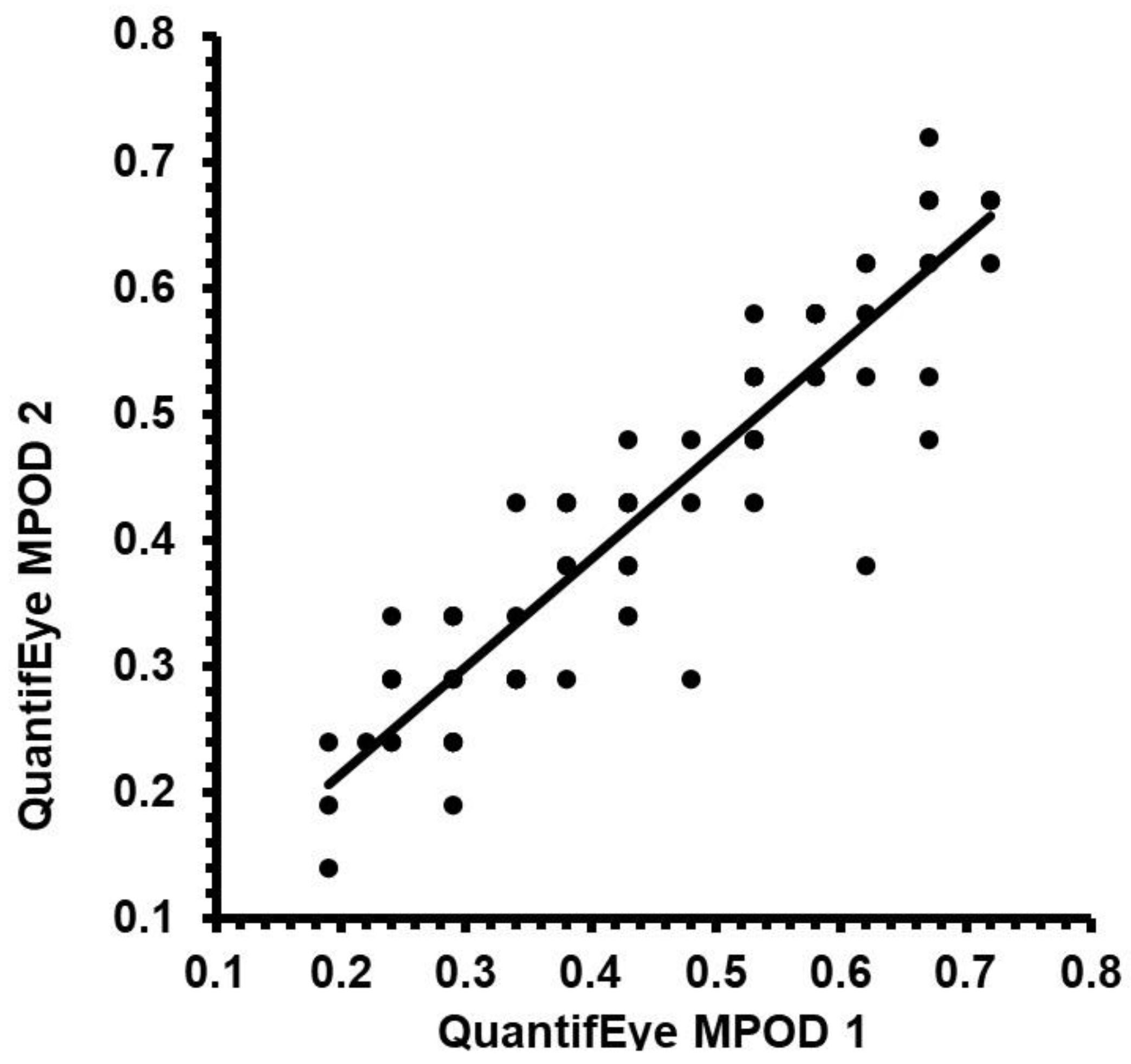

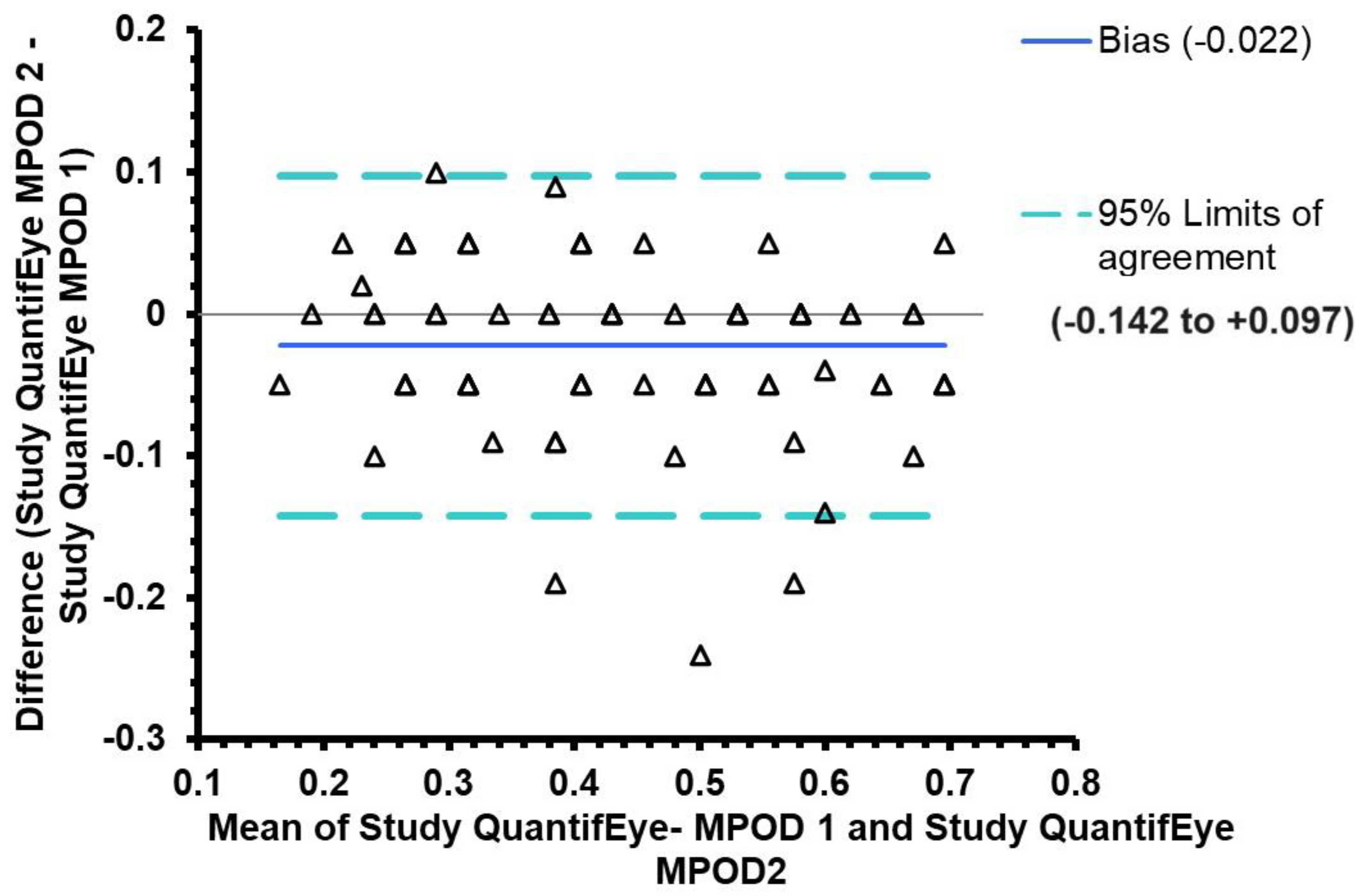

3.1. Repeatability of MPOD measures QuantifEye MPS II

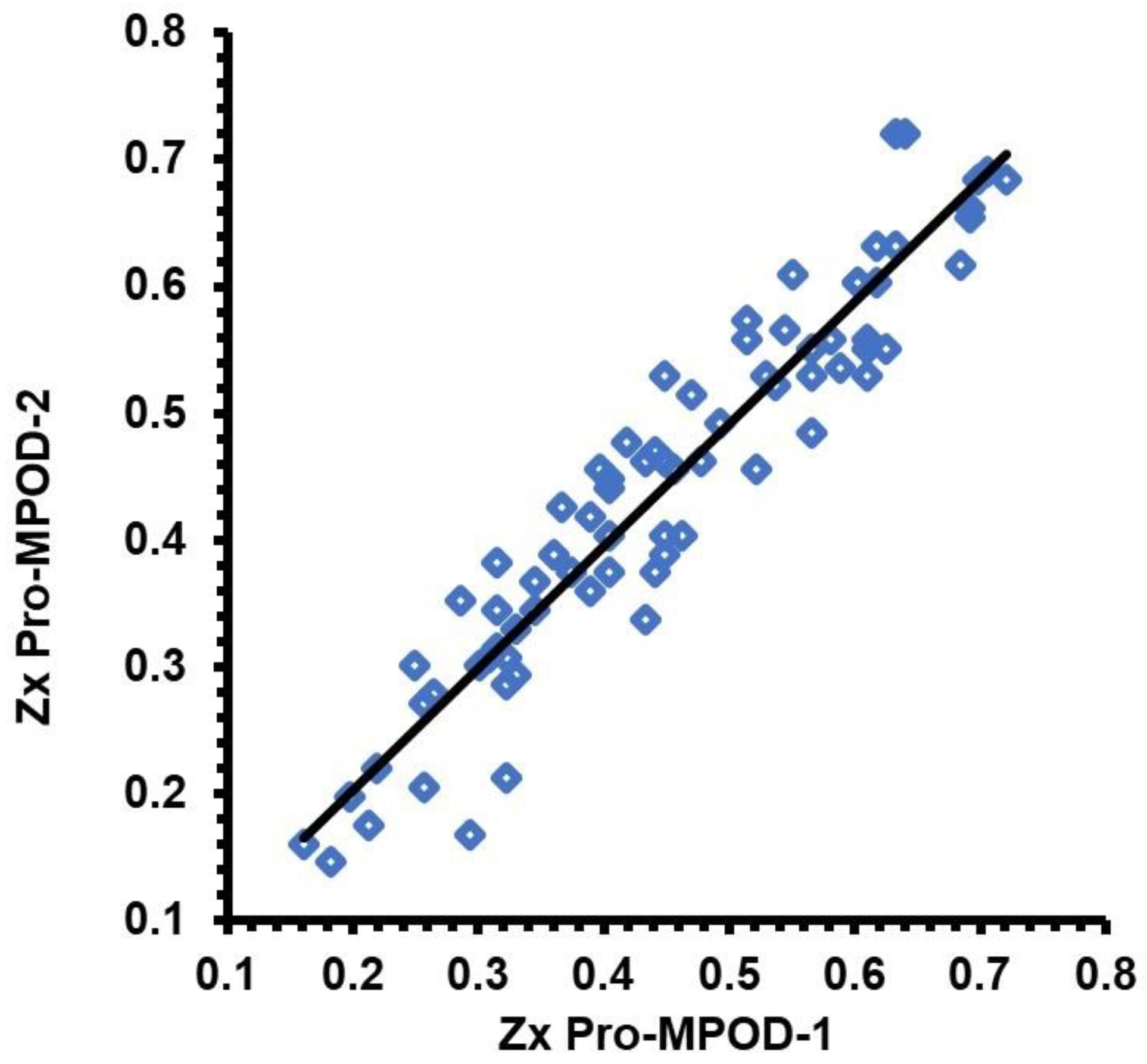

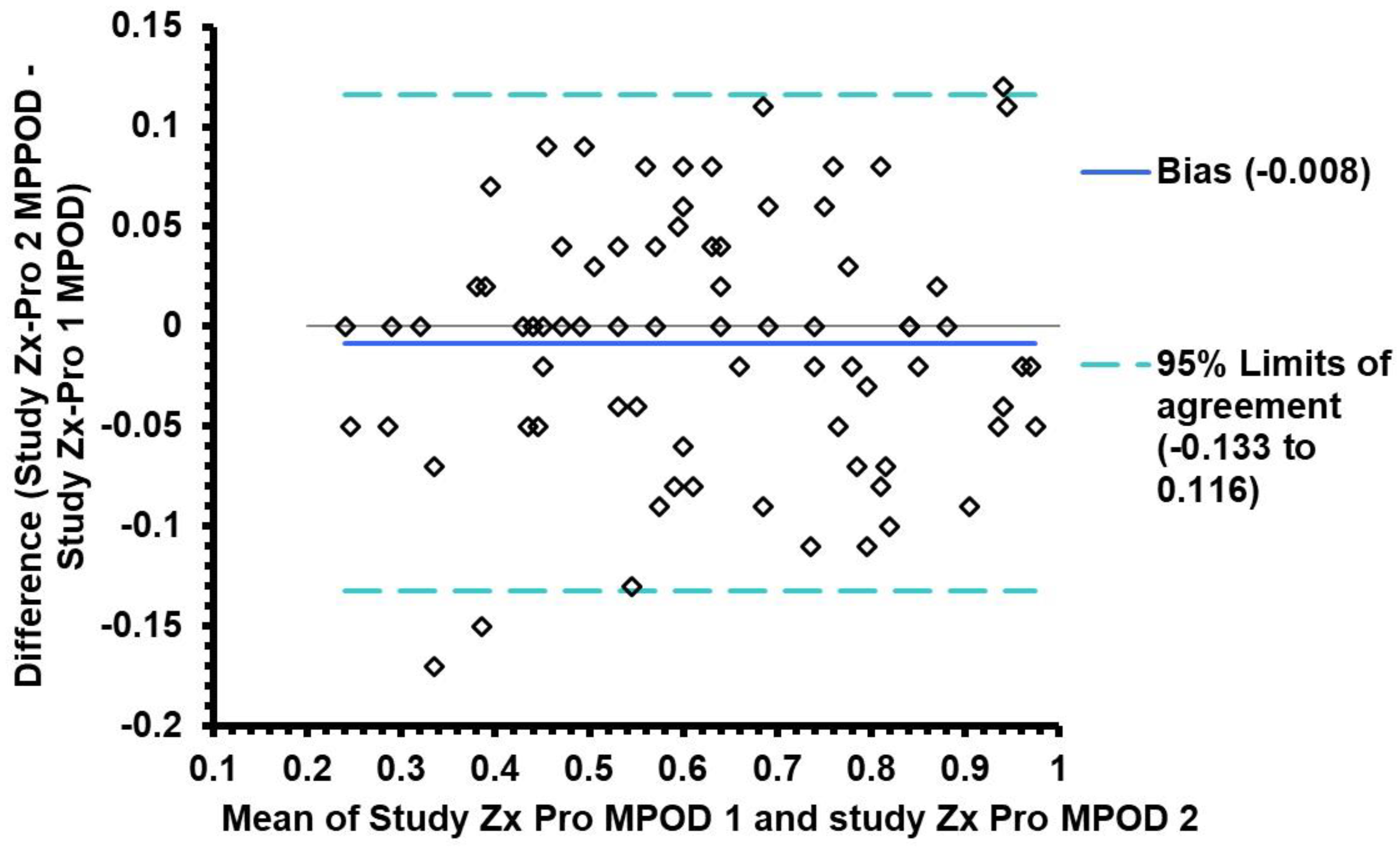

3.2. Repeatability of MPOD measures using Zx Pro

3.3. Comparison of repeatability between the QuantifEye and Zx Pro

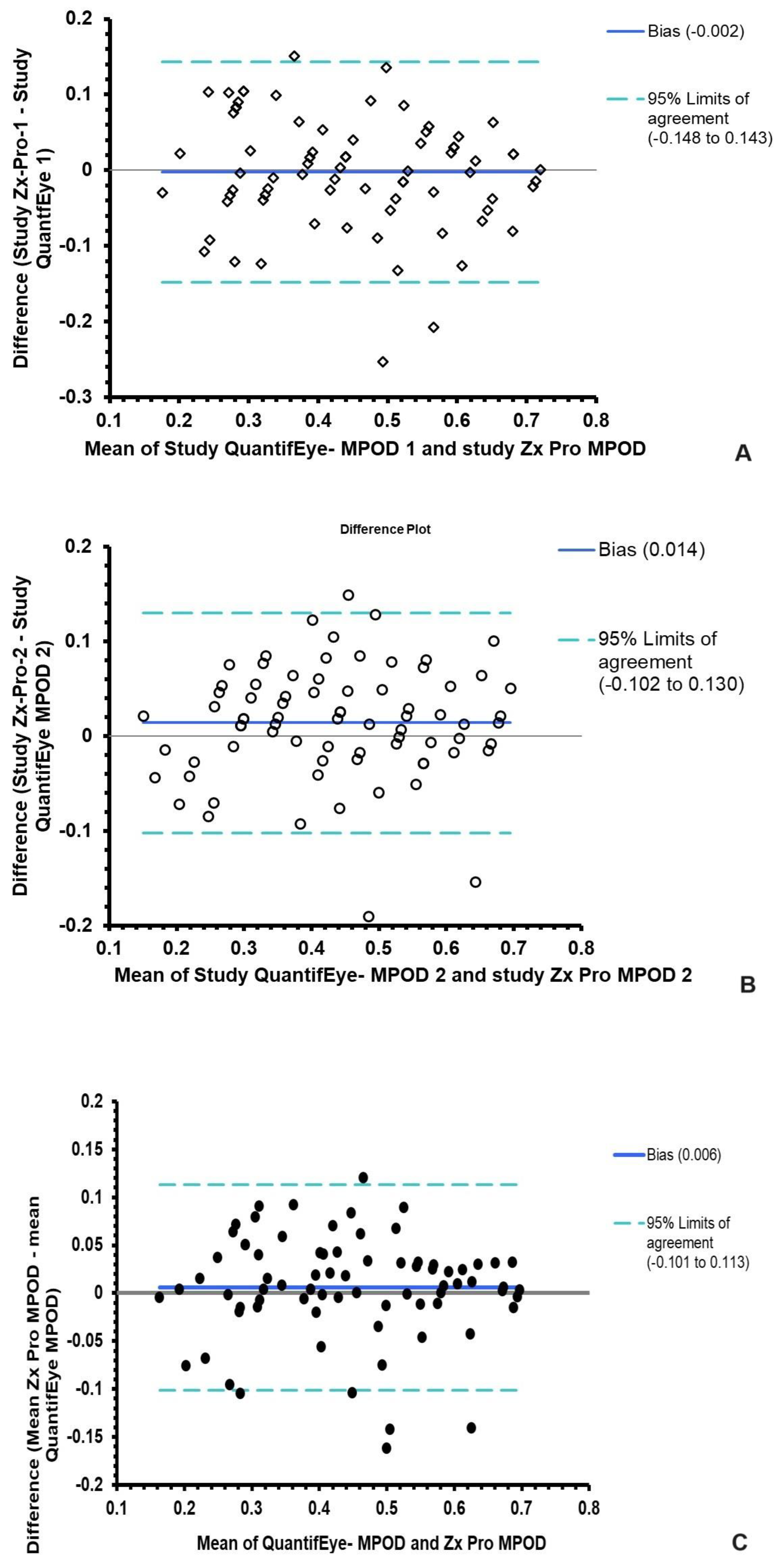

3.4. Agreement between QuantifEye and Zx Pro MPOD measures

| Altman and Bland analysis |

The mean difference between QuantifEye and Zx Pro |

95% limits of agreement |

|---|---|---|

| Study attempt-1 | -0.006 | -0.14 to + 0.14 |

|

Study attempt-2 Mean of Attempts 1 &2 |

+0.013 +0.006 |

-0.10 to + 0.13 -0.101 to + 0.113 |

3.5. Predicting Zx Pro MPOD measures from QuantifEye data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

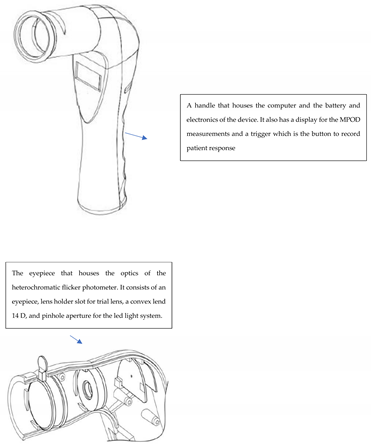

Appendix 1: Schematic of the handheld heterochromatic flicker photometer Zx Pro

References

- Bernstein, P.S.; Delori, F.C.; Richer, S.; van Kuijk, F.J.; Wenzel, A.J. The value of measurement of macular carotenoid pigment optical densities and distributions in age-related macular degeneration and other retinal disorders. Vision Res 2010, 50, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, R.A.; Landrum, J.T.; Hime, G.W.; Cains, A.; Zamor, J. Stereochemistry of the human macular carotenoids. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1993, 34, 2033–2040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, P.S.; Li, B.; Vachali, P.P.; Gorusupudi, A.; Shyam, R.; Henriksen, B.S.; Nolan, J.M. Lutein, zeaxanthin, and meso-zeaxanthin: The basic and clinical science underlying carotenoid-based nutritional interventions against ocular disease. Prog Retin Eye Res 2016, 50, 34–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, R.A.; Landrum, J.T.; Mayne, S.T.; Gomez, C.M.; Tibor, S.E.; Twaroska, E.E. Macular pigment in donor eyes with and without AMD: a case-control study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001, 42, 235–240. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S.E.; Johnson, E.J. Xanthophylls. Adv Nutr 2018, 9, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendschot, T.T.; van Norren, D. Objective determination of the macular pigment optical density using fundus reflectance spectroscopy. Arch Biochem Biophys 2004, 430, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, P.G.; Rosen, R.B.; Gierhart, D.L. Macular Pigment Reflectometry: Developing Clinical Protocols, Comparison with Heterochromatic Flicker Photometry and Individual Carotenoid Levels. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akuffo, K.O.; Beatty, S.; Peto, T.; Stack, J.; Stringham, J.; Kelly, D.; Leung, I.; Corcoran, L.; Nolan, J.M. The Impact of Supplemental Antioxidants on Visual Function in Nonadvanced Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Head-to-Head Randomized Clinical Trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017, 58, 5347–5360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akuffo, K.O.; Beatty, S.; Stack, J.; Dennison, J.; O’Regan, S.; Meagher, K.A.; Peto, T.; Nolan, J. Central Retinal Enrichment Supplementation Trials (CREST): design and methodology of the CREST randomized controlled trials. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2014, 21, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akuffo, K.O.; Nolan, J.M.; Howard, A.N.; Moran, R.; Stack, J.; Klein, R.; Klein, B.E.; Meuer, S.M.; Sabour-Pickett, S.; Thurnham, D.I.; et al. Sustained supplementation and monitored response with differing carotenoid formulations in early age-related macular degeneration. Eye (Lond) 2015, 29, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, H.; Howells, O.; Eperjesi, F. The role of macular pigment assessment in clinical practice: a review. Clin Exp Optom 2010, 93, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatty, S.; Boulton, M.; Henson, D.; Koh, H.H.; Murray, I.J. Macular pigment and age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol 1999, 83, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatty, S.; Murray, I.J.; Henson, D.B.; Carden, D.; Koh, H.; Boulton, M.E. Macular pigment and risk for age-related macular degeneration in subjects from a Northern European population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001, 42, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davey, P.G.; Henderson, T.; Lem, D.W.; Weis, R.; Amonoo-Monney, S.; Evans, D.W. Visual Function and Macular Carotenoid Changes in Eyes with Retinal Drusen-An Open Label Randomized Controlled Trial to Compare a Micronized Lipid-Based Carotenoid Liquid Supplementation and AREDS-2 Formula. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landrum, J.T.; Bone, R.A. Mechanistic Evidence for eye disease and carotenoids; Krinsky, N.I., Mayne, S.T., Sies, H., Eds.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lem, D.W.; Davey, P.G.; Gierhart, D.L.; Rosen, R.B. A Systematic Review of Carotenoids in the Management of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Dou, H.L.; Huang, Y.M.; Lu, X.R.; Xu, X.R.; Qian, F.; Zou, Z.Y.; Pang, H.L.; Dong, P.C.; Xiao, X.; et al. Improvement of retinal function in early age-related macular degeneration after lutein and zeaxanthin supplementation: a randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Ophthalmol 2012, 154, 625–634 e621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Dou, H.L.; Wu, Y.Q.; Huang, Y.M.; Huang, Y.B.; Xu, X.R.; Zou, Z.Y.; Lin, X.M. Lutein and zeaxanthin intake and the risk of age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr 2012, 107, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, R.; Du, J.H.; Liu, T.; Wu, S.S.; Liu, X.H. Lutein, Zeaxanthin and Meso-zeaxanthin Supplementation Associated with Macular Pigment Optical Density. Nutrients 2016, 8, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yan, S.F.; Huang, Y.M.; Lu, X.R.; Qian, F.; Pang, H.L.; Xu, X.R.; Zou, Z.Y.; Dong, P.C.; Xiao, X.; et al. Effect of lutein and zeaxanthin on macular pigment and visual function in patients with early age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 2290–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richer, S.; Stiles, W.; Statkute, L.; Pulido, J.; Frankowski, J.; Rudy, D.; Pei, K.; Tsipursky, M.; Nyland, J. Double-masked, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of lutein and antioxidant supplementation in the intervention of atrophic age-related macular degeneration: the Veterans LAST study (Lutein Antioxidant Supplementation Trial). Optometry 2004, 75, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richer, S.P.; Stiles, W.; Graham-Hoffman, K.; Levin, M.; Ruskin, D.; Wrobel, J.; Park, D.W.; Thomas, C. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of zeaxanthin and visual function in patients with atrophic age-related macular degeneration: the Zeaxanthin and Visual Function Study (ZVF) FDA IND #78, 973. Optometry 2011, 82, 667–680 e666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, C.; Jentsch, S.; Dawczynski, J.; Bohm, V. Age-related macular degeneration: Effects of a short-term intervention with an oleaginous kale extract--a pilot study. Nutrition 2013, 29, 1412–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lem, D.W.; Gierhart, D.L.; Davey, P.G. Management of Diabetic Eye Disease using Carotenoids and Nutrients. In Antioxidants; IntechOpen, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lem, D.W.; Gierhart, D.L.; Davey, P.G. Carotenoids in the Management of Glaucoma: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lem, D.W.; Gierhart, D.L.; Davey, P.G. A Systematic Review of Carotenoids in the Management of Diabetic Retinopathy. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lem, D.W.; Gierhart, D.L.; Davey, P.G. Can Nutrition Play a Role in Ameliorating Digital Eye Strain? Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chous, A.P.; Richer, S.P.; Gerson, J.D.; Kowluru, R.A. The Diabetes Visual Function Supplement Study (DiVFuSS). Br J Ophthalmol 2016, 100, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igras, E.; Loughman, J.; Ratzlaff, M.; O’Caoimh, R.; O’Brien, C. Evidence of lower macular pigment optical density in chronic open angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2013, 97, 994–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Zuo, C.; Lin, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Mi, L.; Liu, B.; Wen, F. Macular Pigment Optical Density in Chinese Primary Open Angle Glaucoma Using the One-Wavelength Reflectometry Method. J Ophthalmol 2016, 2016, 2792103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siah, W.F.; Loughman, J.; O’Brien, C. Lower Macular Pigment Optical Density in Foveal-Involved Glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 2029–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siah, W.F.; O’Brien, C.; Loughman, J.J. Macular pigment is associated with glare-affected visual function and central visual field loss in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2018, 102, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, S.; Chakravarthy, U.; Nolan, J.M.; Muldrew, K.A.; Woodside, J.V.; Denny, F.; Stevenson, M.R. Secondary outcomes in a clinical trial of carotenoids with coantioxidants versus placebo in early age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, R.A.; Davey, P.G.; Roman, B.O.; Evans, D.W. Efficacy of Commercially Available Nutritional Supplements: Analysis of Serum Uptake, Macular Pigment Optical Density and Visual Functional Response. Nutrients 2020, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvi, F.; Souied, E.H.; Falfoul, Y.; Georges, A.; Jung, C.; Querques, L.; Querques, G. Pilot evaluation of short-term changes in macular pigment and retinal sensitivity in different phenotypes of early age-related macular degeneration after carotenoid supplementation. Br J Ophthalmol 2017, 101, 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, B.R., Jr.; Fletcher, L.M.; Elliott, J.G. Glare disability, photostress recovery, and chromatic contrast: relation to macular pigment and serum lutein and zeaxanthin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013, 54, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, B.R.; Fletcher, L.M.; Roos, F.; Wittwer, J.; Schalch, W. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the effects of lutein and zeaxanthin on photostress recovery, glare disability, and chromatic contrast. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014, 55, 8583–8589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.M.; Dou, H.L.; Huang, F.F.; Xu, X.R.; Zou, Z.Y.; Lu, X.R.; Lin, X.M. Changes following supplementation with lutein and zeaxanthin in retinal function in eyes with early age-related macular degeneration: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Ophthalmol 2015, 99, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loughman, J.; Akkali, M.C.; Beatty, S.; Scanlon, G.; Davison, P.A.; O’Dwyer, V.; Cantwell, T.; Major, P.; Stack, J.; Nolan, J.M. The relationship between macular pigment and visual performance. Vision Res 2010, 50, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.M.; Loughman, J.; Akkali, M.C.; Stack, J.; Scanlon, G.; Davison, P.; Beatty, S. The impact of macular pigment augmentation on visual performance in normal subjects: COMPASS. Vision Res 2011, 51, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richer, S.; Devenport, J.; Lang, J.C. LAST II: Differential temporal responses of macular pigment optical density in patients with atrophic age-related macular degeneration to dietary supplementation with xanthophylls. Optometry 2007, 78, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richer, S.; Novil, S.; Gullett, T.; Dervishi, A.; Nassiri, S.; Duong, C.; Davis, R.; Davey, P.G. Night Vision and Carotenoids (NVC): A Randomized Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial on Effects of Carotenoid Supplementation on Night Vision in Older Adults. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akuffo, K.O.; Wooten, B.R.; Ofori-Asare, W.; Osei Duah Junior, I.; Kumah, D.B.; Awuni, M.; Obiri-Yeboah, S.R.; Horthman, S.E.; Addo, E.K.; Acquah, E.A.; et al. Macular Pigment, Cognition, and Visual Function in Younger Healthy Adults in Ghana. J Alzheimers Dis 2023, 94, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannavale, C.N.; Keye, S.A.; Rosok, L.; Martell, S.; Holthaus, T.A.; Reeser, G.; Raine, L.B.; Mullen, S.P.; Cohen, N.J.; Hillman, C.H.; et al. Enhancing children’s cognitive function and achievement through carotenoid consumption: The Integrated Childhood Ocular Nutrition Study (iCONS) protocol. Contemp Clin Trials 2022, 122, 106964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerna, J.; Edwards, C.G.; Martell, S.; Athari Anaraki, N.S.; Walk, A.D.M.; Robbs, C.M.; Adamson, B.C.; Flemming, I.R.; Labriola, L.; Motl, R.W.; et al. Neuroprotective influence of macular xanthophylls and retinal integrity on cognitive function among persons with multiple sclerosis. Int J Psychophysiol 2023, 188, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadam, I.; Nebie, C.; Dalloul, M.; Hittelman, J.; Fordjour, L.; Hoepner, L.; Futterman, I.D.; Minkoff, H.; Jiang, X. Maternal Lutein Intake during Pregnancies with or without Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Cognitive Development of Children at 2 Years of Age: A Prospective Observational Study. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, T.D.L.; Agron, E.; Chew, E.Y.; Areds; Groups, A.R. Dietary nutrient intake and cognitive function in the Age-Related Eye Disease Studies 1 and 2. Alzheimers Dement 2023, 19, 4311–4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmassani, H.A.; Switkowski, K.M.; Johnson, E.J.; Scott, T.M.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Oken, E.; Jacques, P.F. Early Childhood Lutein and Zeaxanthin Intake Is Positively Associated with Early Childhood Receptive Vocabulary and Mid-Childhood Executive Function But No Other Cognitive or Behavioral Outcomes in Project Viva. J Nutr 2022, 152, 2555–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martell, S.G.; Kim, J.; Cannavale, C.N.; Mehta, T.D.; Erdman, J.W., Jr.; Adamson, B.; Motl, R.W.; Khan, N.A. Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Single-Blind Study of Lutein Supplementation on Carotenoid Status and Cognition in Persons with Multiple Sclerosis. J Nutr 2023, 153, 2298–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, R.; Hammond, B.R., Jr.; Chandradhara, D. Lutein and Zeaxanthin Supplementation Improves Dynamic Visual and Cognitive Performance in Children: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Parallel, Placebo-Controlled Study. Adv Ther 2024, 41, 1496–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, J.; Li, A.; Zou, H.; Chen, L.; Du, J. A Machine Learning Based Dose Prediction of Lutein Supplements for Individuals With Eye Fatigue. Front Nutr 2020, 7, 577923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, A.M.; Alblowi, M.; Aldosari, A.M.; Khandekar, R.; Al-Swailem, S.A. Population perceived eye strain due to digital devices usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Int Ophthalmol 2023, 43, 1935–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almudhaiyan, T.M.; Aldebasi, T.; Alakel, R.; Marghlani, L.; Aljebreen, A.; Moazin, O.M. The Prevalence and Knowledge of Digital Eye Strain Among the Undergraduates in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023, 15, e37081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlQarni, A.M.; AlAbdulKader, A.M.; Alghamdi, A.N.; Altayeb, J.; Jabaan, R.; Assaf, L.; Alanazi, R.A. Prevalence of Digital Eye Strain Among University Students and Its Association with Virtual Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clin Ophthalmol 2023, 17, 1755–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, K.R.; Dixit, S.G.; Pandey, L.; Prakash, S.; Shiromani, S.; Singh, K. Digital eye strain among medical students associated with shifting to e-learning during COVID-19 pandemic: An online survey. Indian J Ophthalmol 2024, 72, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, G.C.H.; Chan, L.Y.L.; Do, C.W.; Tse, A.C.Y.; Cheung, T.; Szeto, G.P.Y.; So, B.C.L.; Lee, R.L.T.; Lee, P.H. Association between time spent on smartphones and digital eye strain: A 1-year prospective observational study among Hong Kong children and adolescents. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2023, 30, 58428–58435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyhua-Gutierrez, S.C.; Zeladita-Huaman, J.A.; Diaz-Manchay, R.J.; Dominguez-Palacios, A.B.; Zegarra-Chaponan, R.; Rivas-Souza, M.A.; Tejada-Munoz, S. Digital Eye Strain among Peruvian Nursing Students: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Das, O.; Roy, A.; Das, A. Knowledge, attitude, and practice on digital eye strain during coronavirus disease-2019 lockdown: A comparative study. Oman J Ophthalmol 2022, 15, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mataftsi, A.; Seliniotaki, A.K.; Moutzouri, S.; Prousali, E.; Darusman, K.R.; Adio, A.O.; Haidich, A.B.; Nischal, K.K. Digital eye strain in young screen users: A systematic review. Prev Med 2023, 170, 107493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, P.A.; Wolffsohn, J.S.; Sheppard, A.L. Digital eye strain and its impact on working adults in the UK and Ireland. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2024, 102176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylona, I.; Glynatsis, M.N.; Floros, G.D.; Kandarakis, S. Spotlight on Digital Eye Strain. Clin Optom (Auckl) 2023, 15, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.; Gupta, P.C.; Grover, S.; Furr, A.; Bhargava, N. Prevalence and Association of Digital Eye Strain with the Quality of Sleep and Feeling of Loneliness among Female College Students in Northern India. Indian J Public Health 2023, 67, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Satija, J.; Antil, P.; Dahiya, R.; Shekhawat, S. Determinants of digital eye strain among university students in a district of India: a cross-sectional study. Z Gesundh Wiss 2023, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, P.; Singh Pradhan, P.M. Digital Eye Strain in Medical Undergraduate Students during COVID-19 Pandemic. J Nepal Health Res Counc 2023, 20, 726–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanathan, R.; Neuringer, M.; Snodderly, D.M.; Schalch, W.; Johnson, E.J. Macular lutein and zeaxanthin are related to brain lutein and zeaxanthin in primates. Nutr Neurosci 2013, 16, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorey, C.K.; Gierhart, D.; Fitch, K.A.; Crandell, I.; Craft, N.E. Low Xanthophylls, Retinol, Lycopene, and Tocopherols in Grey and White Matter of Brains with Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2023, 94, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Schneider, J.A.; Willett, W.C.; Morris, M.C. Dietary carotenoids related to risk of incident Alzheimer dementia (AD) and brain AD neuropathology: a community-based cohort of older adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2021, 113, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, R.A.; Mukherjee, A. Innovative Troxler-free measurement of macular pigment and lens density with correction of the former for the aging lens. J Biomed Opt 2013, 18, 107003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Veen, R.L.; Berendschot, T.T.; Hendrikse, F.; Carden, D.; Makridaki, M.; Murray, I.J. A new desktop instrument for measuring macular pigment optical density based on a novel technique for setting flicker thresholds. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2009, 29, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Veen, R.L.; Berendschot, T.T.; Makridaki, M.; Hendrikse, F.; Carden, D.; Murray, I.J. Correspondence between retinal reflectometry and a flicker-based technique in the measurement of macular pigment spatial profiles. J Biomed Opt 2009, 14, 064046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, S.; Koh, H.H.; Carden, D.; Murray, I.J. Macular pigment optical density measurement: a novel compact instrument. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2000, 20, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, P.G.; Alvarez, S.D.; Lee, J.Y. Macular pigment optical density: repeatability, intereye correlation, and effect of ocular dominance. Clin Ophthalmol 2016, 10, 1671–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, P.G.; Ngo, A.; Cross, J.; Gierhart, D.L. Macular Pigment Reflectometry: Development and evaluation of a novel clinical device for rapid objective assessment of the macular carotenoids. In Ophthalmic Technologies Xxix; Manns, F., Soderberg, P.G., Ho, A., Eds.; Proceedings of SPIE; Spie-Int Soc Optical Engineering: Bellingham, 2019; Volume 10858. [Google Scholar]

- de Kinkelder, R.; van der Veen, R.L.; Verbaak, F.D.; Faber, D.J.; van Leeuwen, T.G.; Berendschot, T.T. Macular pigment optical density measurements: evaluation of a device using heterochromatic flicker photometry. Eye (Lond) 2011, 25, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howells, O.; Eperjesi, F.; Bartlett, H. Improving the repeatability of heterochromatic flicker photometry for measurement of macular pigment optical density. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013, 251, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Guan, C.; Ng, D.S.; Liu, X.; Chen, H. Macular Pigment Optical Density Measured by a Single Wavelength Reflection Photometry with and without Mydriasis. Curr Eye Res 2019, 44, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, I.J.; Carden, D.; Makridaki, M. The repeatability of the MPS 9000 macular pigment screener. Br J Ophthalmol 2011, 95, 431–432; author reply 432–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, I.J.; Hassanali, B.; Carden, D. Macular pigment in ophthalmic practice; a survey. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013, 251, 2355–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, I.J.; Makridaki, M.; van der Veen, R.L.; Carden, D.; Parry, N.R.; Berendschot, T.T. Lutein supplementation over a one-year period in early AMD might have a mild beneficial effect on visual acuity: the CLEAR study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013, 54, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Berumen, K.; Davey, P.G. Macular Pigments Optical Density: A Review of Techniques of Measurements and Factors Influencing their Levels. JSM Ophthalmol 2014, 3, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Stringham, J.M.; O’Brien, K.J.; Stringham, N.T. Macular carotenoid supplementation improves disability glare performance and dynamics of photostress recovery. Eye Vis (Lond) 2016, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringham, J.M.; O’Brien, K.J.; Stringham, N.T. Contrast Sensitivity and Lateral Inhibition Are Enhanced With Macular Carotenoid Supplementation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017, 58, 2291–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringham, J.M.; Stringham, N.T.; O’Brien, K.J. Macular Carotenoid Supplementation Improves Visual Performance, Sleep Quality, and Adverse Physical Symptoms in Those with High Screen Time Exposure. Foods 2017, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; George, E.W.; Rognon, G.T.; Gorusupudi, A.; Ranganathan, A.; Chang, F.Y.; Shi, L.; Frederick, J.M.; Bernstein, P.S. Imaging lutein and zeaxanthin in the human retina with confocal resonance Raman microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 12352–12358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, H.; Eperjesi, F. Use of fundus imaging in quantification of age-related macular change. Surv Ophthalmol 2007, 52, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, R.A.; Landrum, J.T. Dose-dependent response of serum lutein and macular pigment optical density to supplementation with lutein esters. Arch Biochem Biophys 2010, 504, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, R.A.; Landrum, J.T.; Cao, Y.; Howard, A.N.; Alvarez-Calderon, F. Macular pigment response to a supplement containing meso-zeaxanthin, lutein and zeaxanthin. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2007, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.M.; Yan, S.F.; Ma, L.; Zou, Z.Y.; Xu, X.R.; Dou, H.L.; Lin, X.M. Serum and macular responses to multiple xanthophyll supplements in patients with early age-related macular degeneration. Nutrition 2013, 29, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landrum, J.T.; Bone, R.A.; Joa, H.; Kilburn, M.D.; Moore, L.L.; Sprague, K.E. A one year study of the macular pigment: the effect of 140 days of a lutein supplement. Exp Eye Res 1997, 65, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obana, A.; Hiramitsu, T.; Gohto, Y.; Ohira, A.; Mizuno, S.; Hirano, T.; Bernstein, P.S.; Fujii, H.; Iseki, K.; Tanito, M.; et al. Macular carotenoid levels of normal subjects and age-related maculopathy patients in a Japanese population. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendschot, T.T.; Goldbohm, R.A.; Klopping, W.A.; van de Kraats, J.; van Norel, J.; van Norren, D. Influence of lutein supplementation on macular pigment, assessed with two objective techniques. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000, 41, 3322–3326. [Google Scholar]

- Davey, P.G.; Lievens, C.; Ammono-Monney, S. Differences in macular pigment optical density across four ethnicities: a comparative study. Ther Adv Ophthalmol 2020, 12, 2515841420924167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanabria, J.C.; Bass, J.; Spors, F.; Gierhart, D.L.; Davey, P.G. Measurement of Carotenoids in Perifovea using the Macular Pigment Reflectometer. J Vis Exp 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obana, A.; Tanito, M.; Gohto, Y.; Gellermann, W.; Okazaki, S.; Ohira, A. Macular pigment changes in pseudophakic eyes quantified with resonance Raman spectroscopy. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 1852–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Kraats, J.; van Norren, D. Directional and nondirectional spectral reflection from the human fovea. J Biomed Opt 2008, 13, 024010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringham, J.M.; Hammond, B.R. Macular pigment and visual performance under glare conditions. Optom Vis Sci 2008, 85, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringham, J.M.; Hammond, B.R.; Nolan, J.M.; Wooten, B.R.; Mammen, A.; Smollon, W.; Snodderly, D.M. The utility of using customized heterochromatic flicker photometry (cHFP) to measure macular pigment in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res 2008, 87, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooten, B.R.; Hammond, B.R., Jr.; Land, R.I.; Snodderly, D.M. A practical method for measuring macular pigment optical density. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999, 40, 2481–2489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arunkumar, R.; Calvo, C.M.; Conrady, C.D.; Bernstein, P.S. What do we know about the macular pigment in AMD: the past, the present, and the future. Eye (Lond) 2018, 32, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccarelli, L.M.; Scherr, R.E.; Dharmar, M.; Ermakov, I.V.; Gellermann, W.; Jahns, L.; Linnell, J.D.; Keen, C.L.; Steinberg, F.M.; Young, H.M.; et al. Using Skin Carotenoids to Assess Dietary Changes in Students After 1 Academic Year of Participating in the Shaping Healthy Choices Program. J Nutr Educ Behav 2017, 49, 73–78 e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ermakov, I.V.; Gellermann, W. Optical detection methods for carotenoids in human skin. Arch Biochem Biophys 2015, 572, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahns, L.; Johnson, L.K.; Mayne, S.T.; Cartmel, B.; Picklo, M.J., Sr.; Ermakov, I.V.; Gellermann, W.; Whigham, L.D. Skin and plasma carotenoid response to a provided intervention diet high in vegetables and fruit: uptake and depletion kinetics. Am J Clin Nutr 2014, 100, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahns, L.; Johnson, L.K.; Conrad, Z.; Bukowski, M.; Raatz, S.K.; Jilcott Pitts, S.; Wang, Y.; Ermakov, I.V.; Gellermann, W. Concurrent validity of skin carotenoid status as a concentration biomarker of vegetable and fruit intake compared to multiple 24-h recalls and plasma carotenoid concentrations across one year: a cohort study. Nutr J 2019, 18, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obana, A.; Gohto, Y.; Gellermann, W.; Ermakov, I.V.; Sasano, H.; Seto, T.; Bernstein, P.S. Skin Carotenoid Index in a large Japanese population sample. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 9318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayanagi, Y.; Obana, A.; Muto, S.; Asaoka, R.; Tanito, M.; Ermakov, I.V.; Bernstein, P.S.; Gellermann, W. Relationships between Skin Carotenoid Levels and Metabolic Syndrome. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvin, M.E.; Lademann, J.; von Hagen, J.; Lohan, S.B.; Kolmar, H.; Meinke, M.C.; Jung, S. Carotenoids in Human SkinIn Vivo: Antioxidant and Photo-Protectant Role against External and Internal Stressors. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarmo, S.; Cartmel, B.; Lin, H.; Leffell, D.J.; Welch, E.; Bhosale, P.; Bernstein, P.S.; Mayne, S.T. Significant correlations of dermal total carotenoids and dermal lycopene with their respective plasma levels in healthy adults. Arch Biochem Biophys 2010, 504, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosok, L.M.; Cannavale, C.N.; Keye, S.A.; Holscher, H.D.; Renzi-Hammond, L.; Khan, N.A. Skin and macular carotenoids and relations to academic achievement among school-aged children. Nutr Neurosci 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, H.E.; Eperjesi, F. Effect of lutein and antioxidant dietary supplementation on contrast sensitivity in age-related macular disease: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr 2007, 61, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, B.R., Jr.; Ciulla, T.A.; Snodderly, D.M. Macular pigment density is reduced in obese subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002, 43, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, B.R., Jr.; Curran-Celentano, J.; Judd, S.; Fuld, K.; Krinsky, N.I.; Wooten, B.R.; Snodderly, D.M. Sex differences in macular pigment optical density: relation to plasma carotenoid concentrations and dietary patterns. Vision Res 1996, 36, 2001–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, B.R., Jr.; Fuld, K.; Snodderly, D.M. Iris color and macular pigment optical density. Exp Eye Res 1996, 62, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, O.; Eperjesi, F.; Bartlett, H. Measuring macular pigment optical density in vivo: a review of techniques. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011, 249, 315–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.M.; Power, R.; Stringham, J.; Dennison, J.; Stack, J.; Kelly, D.; Moran, R.; Akuffo, K.O.; Corcoran, L.; Beatty, S. Enrichment of Macular Pigment Enhances Contrast Sensitivity in Subjects Free of Retinal Disease: Central Retinal Enrichment Supplementation Trials - Report 1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016, 57, 3429–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trieschmann, M.; Beatty, S.; Nolan, J.M.; Hense, H.W.; Heimes, B.; Austermann, U.; Fobker, M.; Pauleikhoff, D. Changes in macular pigment optical density and serum concentrations of its constituent carotenoids following supplemental lutein and zeaxanthin: the LUNA study. Exp Eye Res 2007, 84, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, P.S.; Zhao, D.Y.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Ermakov, I.V.; Gellermann, W. Resonance Raman measurement of macular carotenoids in the living human eye. Arch Biochem Biophys 2004, 430, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, P.S.; Zhao, D.Y.; Wintch, S.W.; Ermakov, I.V.; McClane, R.W.; Gellermann, W. Resonance Raman measurement of macular carotenoids in normal subjects and in age-related macular degeneration patients. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 1780–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obana, A.; Gohto, Y.; Asaoka, R. Macular pigment changes after cataract surgery with yellow-tinted intraocular lens implantation. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0248506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obana, A.; Ote, K.; Gohto, Y.; Yamada, H.; Hashimoto, F.; Okazaki, S.; Asaoka, R. Deep learning-based correction of cataract-induced influence on macular pigment optical density measurement by autofluorescence spectroscopy. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0298132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obana, A.; Ote, K.; Hashimoto, F.; Asaoka, R.; Gohto, Y.; Okazaki, S.; Yamada, H. Correction for the Influence of Cataract on Macular Pigment Measurement by Autofluorescence Technique Using Deep Learning. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2021, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Difference in first and second measurements | Mean | 95% confidence intervals | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QuantifEye | 0.022 | 0.01 to 0.04 | 0.00 | -0.10 | 0.24 |

| Zx Pro | 0.006 | 0.00 to 0.02 | 0.00 | -0.08 | 0.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).