Submitted:

06 September 2024

Posted:

06 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

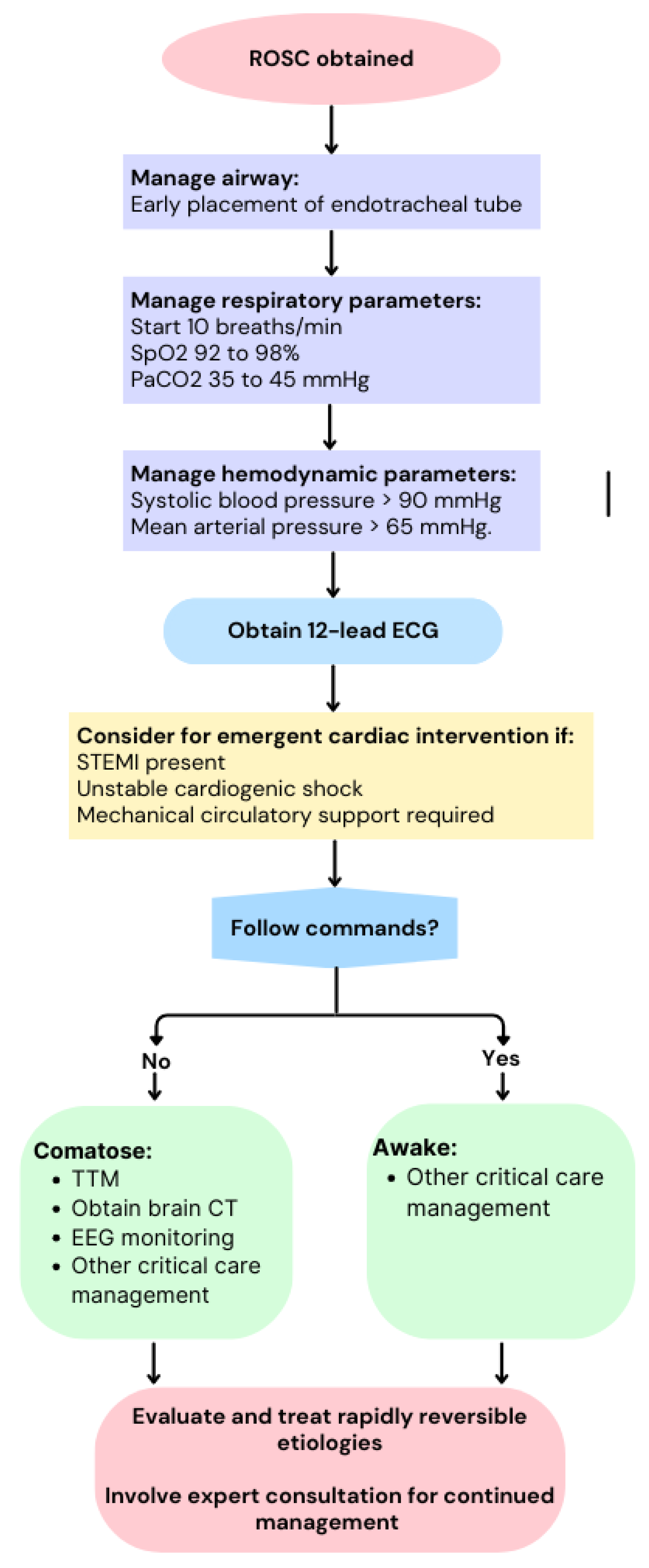

1. Introduction

2. Role of Ultrasonography in Cardiac Arrest

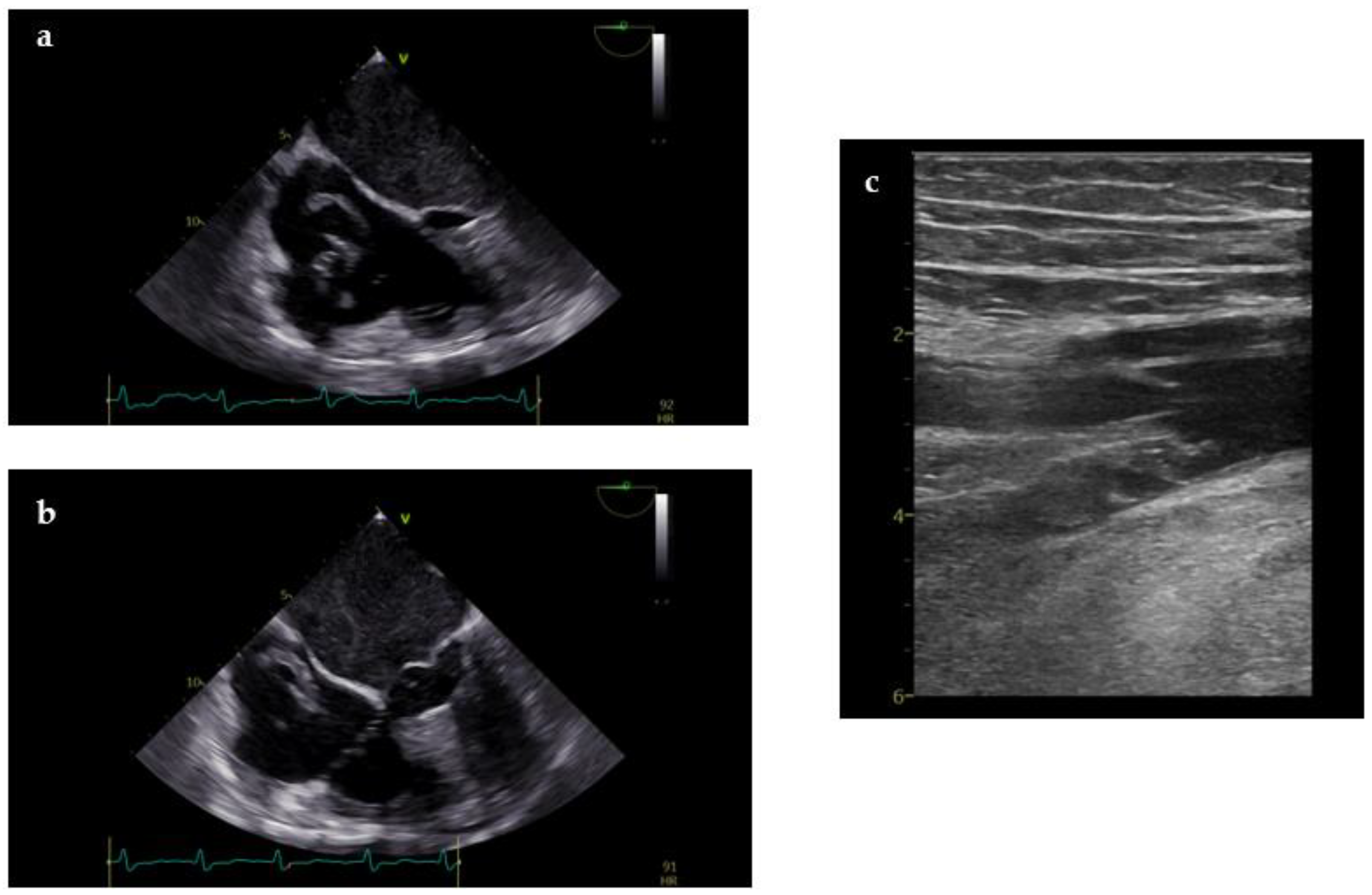

2.1. Role of Ultrasonography during Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

2.2. Role of Ultrasonography in Post-Resuscitation Care

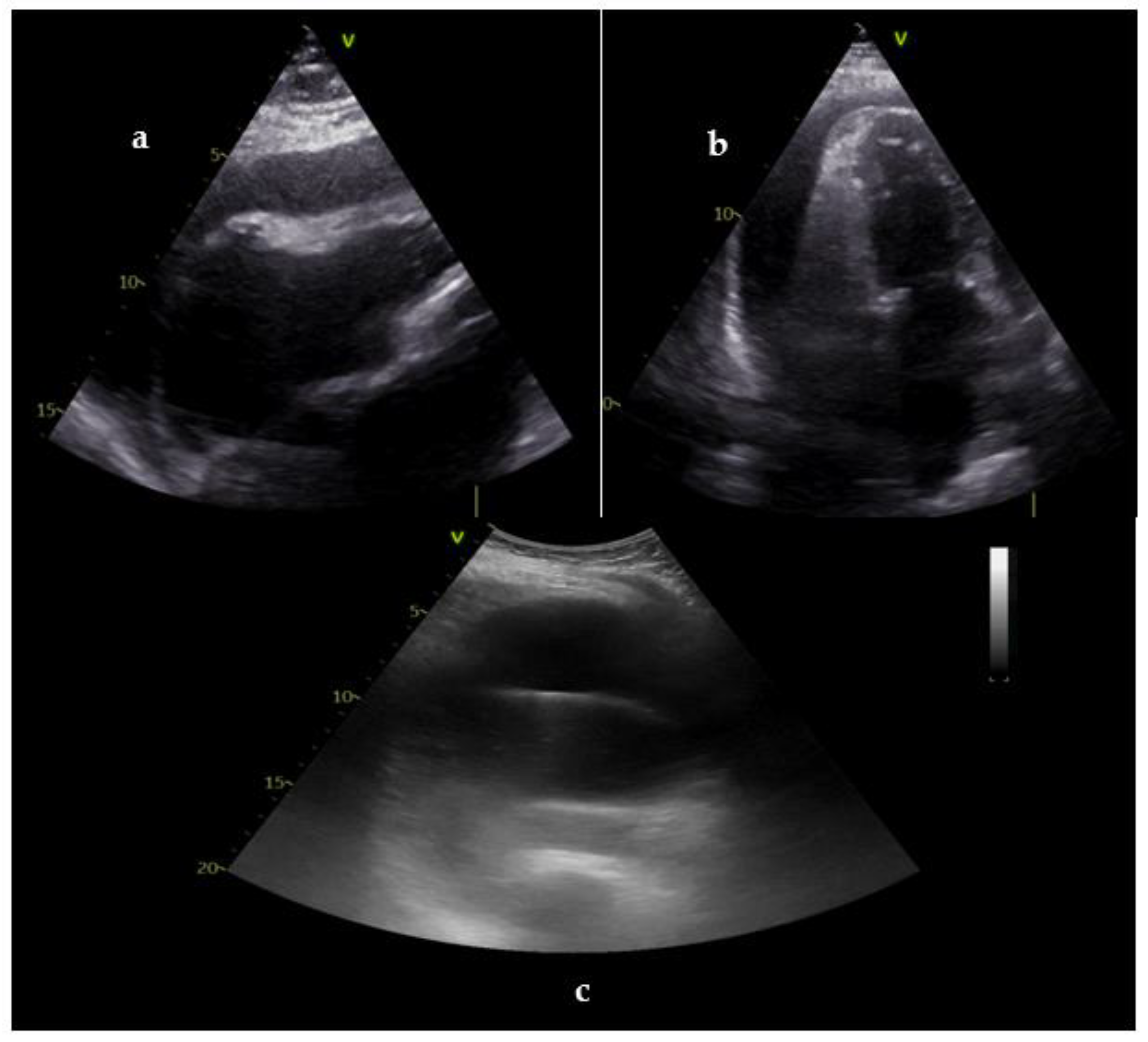

2.2.1. Diagnosis of Underlying Cause of Cardiac Arrest

2.2.2. Hemodynamic Monitoring and Optimization

| Parameter | Utility | How to calculate |

Normal values and interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Perfusion parameters |

LVOT VTI | Distance that blood travels across the LVOT during cardiac cycle | Tracing the PWD spectral display of the LVOT | LVOT-VTI > 18 cm |

| SV | Volume of blood pumped during each systolic cardiac contraction | SV= LVOT area* x LVOT-VTI SVi= SV/BSA |

SV > 70 ml SVi >35 ml/mq |

|

| CO and CI | Amount of blood pumped by the heart in a minute; | CO = SV x HR CI= CO/BSA |

CO > 4 l/min CI < 2.5 l/min/mq |

|

| Preload parameters (fluid responsiveness and fluid tolerance) | IVC diameter and collapsibility | Used to estimate RA pressure, and volemic status | Diameters of IVC at end expiration and inspiration in subcostal view | IVC < 21 mm that collapses > 50% (RAP 0-5 mmHg); IVC > 21 mm that collapses > 50% or IVC < 21 mm that collapses < 50% (RAP 5-10 mmHg); IVC > 21 mm that collapses < 50% (RAP 10-20 mmHg) |

| JVD ratio | Used to estimate RA pressure, and volemic status | JVD during Valsalva/JVD at rest | JVD ratio < 3 suggest elevated RAP and fluid overload | |

| LVOT-VTI variability | Dynamic parameters that suggest fluid responsiveness | Evaluation of LVOT-VTI in different respiratory phases during MV, after PLR or fluid challenge | Change in LVOT-VTI < 10-15% indicates fluid responsiveness | |

| VExUS score | Evaluation of systemic congestion in four grades | Combined evaluation of IVC diameter and venous flow pattern using PWD in HV, PV and IRV | VExUS score 0 = no congestion; VExUS score 3 = severe congestion | |

| LUS B-lines | Evaluation of pulmonary congestion | Evaluation of B-lines in 8 to 12 zones | B-lines < 3 for scanning zone = normal; Multiple and diffuse B-lines = severe congestion |

|

| E/e’ | Marker of LV filling pressure that correlates with PCWP [ PCWP≈1.24×(E/e)+1.9] | Ratio between mitral inflow E velocity using PWD and e’ lateral and medial velocity using TDI | E/e’ < 7 = normal filling pressure; E/e’ > 15= elevated filling pressure |

|

| Afterloadparameters | SVR | Determinant of LV afterload and reflect the tone of systemic blood vessels | MAP-CVP/CO** | SVR 800-1200 dynes·sec/cm^5 = 10-15 WU |

| PASP | Estimation of pulmonary artery systolic pressure | PASP=4×(TRV2)+RAP | PASP < 35 mmHg | |

| PAMP | Estimation of pulmonary artery mean pressure | PAPM=0.61×PASP+2 or PAPM=4×(PRV2 )+RAP | PAMP < 20 mmHg | |

| PVR | Determinant of RV afterload and reflect the tone of pulmonary blood vessels | PVR= (PAMP-PCWP)/CO | PVR < 2 WU | |

| TRV/RVOT-VTI ratio | Parameter to estimate PVR and PAP | Ratio between TRV and RVOT-VTI calculated tracing the PWD spectral display of the RVOT | TRV/RVOT-VTI ratio < 0.45 |

2.2.3. Role of Transesophageal Echocardiography

2.2.4. Role of Non-Cardiac Ultrasounds

3. Post-Cardiac Arrest Syndrome: Pathophysiology and Echocardiographic Feature

Role of Echocardiography in Post-Arrest Management of Suspected ACS/CAD

4. Prognostic Role of Echocardiography in Resuscitated CA Patients: Future Perspective

| Parameters | TTE | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Systolic Function |

Serial LVEF assessment RV function |

LVEF evaluated through Biplane method RV FAC and 3D RV ejection fraction* |

Dynamic changes in systolic function are associated with outcomes after OHCA more than single static measurements Reduced RV systolic function (RV FAC < 35% or 3D RV ejection fraction < 45%) associated with worse outcome |

| Diastolic function | LV diastolic function and filling pressures | Ratio of early mitral Doppler filling and mitral annular excursion (E/e’)* | LV diastolic dysfunction (E/e’ > 14) associated with increased mortality after OHCA |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- A. G. Yow, V. Rajasurya, I. Ahmed, and S. Sharma, “Sudden Cardiac Death,” StatPearls, Mar. 2024, Accessed: May 28, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507854/.

- C. Mehta and W. Brady, “Pulseless electrical activity in cardiac arrest: electrocardiographic presentations and management considerations based on the electrocardiogram,” Am J Emerg Med, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 236–239, Jan. 2012, doi: 10.1016/J.AJEM.2010.08.017. [CrossRef]

- J. Rabjohns, T. Quan, K. Boniface, and A. Pourmand, “Pseudo-pulseless electrical activity in the emergency department, an evidence based approach,” Am J Emerg Med, vol. 38, no. 2, pp. 371–375, Feb. 2020, doi: 10.1016/J.AJEM.2019.158503. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Nolan et al., “European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Guidelines 2021: Post-resuscitation care,” Resuscitation, vol. 161, pp. 220–269, Apr. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.012. [CrossRef]

- K. G. Hirsch et al., “Critical Care Management of Patients After Cardiac Arrest: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and Neurocritical Care Society,” Circulation, vol. 149, no. 2, Jan. 2024, doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001163. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Panchal et al., “Part 3: Adult Basic and Advanced Life Support: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care,” Circulation, vol. 142, no. 16_suppl_2, Oct. 2020, doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000916. [CrossRef]

- A. Wong, P. Vignon, and C. Robba, “How I use ultrasound in cardiac arrest,” Intensive Care Med, vol. 49, no. 12, pp. 1531–1534, Dec. 2023, doi: 10.1007/s00134-023-07249-8. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Jensen, E. Sloth, K. M. Larsen, and M. B. Schmidt, “Transthoracic echocardiography for cardiopulmonary monitoring in intensive care,” Eur J Anaesthesiol, vol. 21, no. 9, pp. 700–707, Sep. 2004, doi: 10.1017/S0265021504009068. [CrossRef]

- D. F. Niendorff, A. J. Rassias, R. Palac, M. L. Beach, S. Costa, and M. Greenberg, “Rapid cardiac ultrasound of inpatients suffering PEA arrest performed by nonexpert sonographers,” Resuscitation, vol. 67, no. 1, pp. 81–87, Oct. 2005, doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.04.007. [CrossRef]

- R. Breitkreutz, F. Walcher, and F. H. Seeger, “Focused echocardiographic evaluation in resuscitation management: Concept of an advanced life support–conformed algorithm,” Crit Care Med, vol. 35, no. Suppl, pp. S150–S161, May 2007, doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000260626.23848.FC. [CrossRef]

- C. Hernandez, K. Shuler, H. Hannan, C. Sonyika, A. Likourezos, and J. Marshall, “C.A.U.S.E.: Cardiac arrest ultra-sound exam—A better approach to managing patients in primary non-arrhythmogenic cardiac arrest,” Resuscitation, vol. 76, no. 2, pp. 198–206, Feb. 2008, doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.06.033. [CrossRef]

- G. Prosen, M. Križmarić, J. Završnik, and Š. Grmec, “Impact of Modified Treatment in Echocardiographically Confirmed Pseudo-Pulseless Electrical Activity in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Patients with Constant End-Tidal Carbon Dioxide Pressure during Compression Pauses,” Journal of International Medical Research, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 1458–1467, Aug. 2010, doi: 10.1177/147323001003800428. [CrossRef]

- A. Testa et al., “The proposal of an integrated ultrasonographic approach into the ALS algorithm for cardiac arrest: the PEA protocol.,” Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 77–88, Feb. 2010.

- D. Lichtenstein and M. L. N. G. Malbrain, “Critical care ultrasound in cardiac arrest. Technological requirements for performing the SESAME-protocol — a holistic approach,” Anestezjol Intens Ter, vol. 47, no. 5, pp. 471–481, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.5603/AIT.a2015.0072. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Atkinson, N. Beckett, J. French, A. Banerjee, J. Fraser, and D. Lewis, “Does Point-of-care Ultrasound Use Impact Resuscitation Length, Rates of Intervention, and Clinical Outcomes During Cardiac Arrest? A Study from the Sonography in Hypotension and Cardiac Arrest in the Emergency Department (SHoC-ED) Investigators,” Cureus, Apr. 2019, doi: 10.7759/cureus.4456. [CrossRef]

- P. Atkinson et al., “International Federation for Emergency Medicine Consensus Statement: Sonography in hypotension and cardiac arrest (SHoC): An international consensus on the use of point of care ultrasound for undifferentiated hypotension and during cardiac arrest,” CJEM, vol. 19, no. 06, pp. 459–470, Nov. 2017, doi: 10.1017/cem.2016.394. [CrossRef]

- D. Ávila-Reyes, A. O. Acevedo-Cardona, J. F. Gómez-González, D. R. Echeverry-Piedrahita, M. Aguirre-Flórez, and A. Giraldo-Diaconeasa, “Point-of-care ultrasound in cardiorespiratory arrest (POCUS-CA): narrative review article,” Ultrasound J, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 46, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.1186/s13089-021-00248-0. [CrossRef]

- P. Blanco and C. Martínez Buendía, “Point-of-care ultrasound in cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a concise review,” J Ultrasound, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 193–198, Sep. 2017, doi: 10.1007/s40477-017-0256-3. [CrossRef]

- J. White, “The Value of Focused Echocardiography During Cardiac Arrest,” Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography, vol. 35, no. 6, pp. 484–490, Nov. 2019, doi: 10.1177/8756479319870171. [CrossRef]

- A. Osman and K. M. Sum, “Role of upper airway ultrasound in airway management,” J Intensive Care, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 52, Dec. 2016, doi: 10.1186/s40560-016-0174-z. [CrossRef]

- P. H. Mayo et al., “Thoracic ultrasonography: a narrative review,” Intensive Care Med, vol. 45, no. 9, pp. 1200–1211, Sep. 2019, doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05725-8. [CrossRef]

- F. Teran et al., “Focused Transesophageal Echocardiography During Cardiac Arrest Resuscitation,” J Am Coll Cardiol, vol. 76, no. 6, pp. 745–754, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.074. [CrossRef]

- G. Riendeau Beaulac et al., “Transesophageal Echocardiography in Patients in Cardiac Arrest: The Heart and Beyond,” Canadian Journal of Cardiology, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 458–473, Apr. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2022.12.027. [CrossRef]

- L. Hussein et al., “Transoesophageal echocardiography in cardiac arrest: A systematic review,” Resuscitation, vol. 168, pp. 167–175, Nov. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.08.001. [CrossRef]

- D. Borde et al., “Use of a Video Laryngoscope to Reduce Complications of Transesophageal Echocardiography Probe Insertion: A Multicenter Randomized Study,” J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth, vol. 36, no. 12, pp. 4289–4295, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2022.07.017. [CrossRef]

- C. T. Buschmann and M. Tsokos, “Frequent and rare complications of resuscitation attempts,” Intensive Care Med, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 397–404, Mar. 2009, doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1255-9. [CrossRef]

- L. Liu et al., “Scoping review of echocardiographic parameters associated with diagnosis and prognosis after resuscitated sudden cardiac arrest,” Resuscitation, vol. 184, p. 109719, Mar. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2023.109719. [CrossRef]

- L. Elfwén et al., “Focused cardiac ultrasound after return of spontaneous circulation in cardiac-arrest patients,” Resuscitation, vol. 142, pp. 16–22, Sep. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.06.282. [CrossRef]

- C. Lott et al., “European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Cardiac arrest in special circumstances,” Resuscitation, vol. 161, pp. 152–219, Apr. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.011. [CrossRef]

- S. V Konstantinides et al., “2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS),” Eur Heart J, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 543–603, Jan. 2020, doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Nasser et al., “Echocardiographic Evaluation of Pulmonary Embolism: A Review,” Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography, vol. 36, no. 9, pp. 906–912, Sep. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2023.05.006. [CrossRef]

- M. D’Alto et al., “Echocardiographic probability of pulmonary hypertension: a validation study,” European Respiratory Journal, vol. 60, no. 2, p. 2102548, Aug. 2022, doi: 10.1183/13993003.02548-2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Arbelo et al., “2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies,” Eur Heart J, vol. 44, no. 37, pp. 3503–3626, Oct. 2023, doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad194. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Jentzer et al., “Changes in left ventricular systolic and diastolic function on serial echocardiography after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,” Resuscitation, vol. 126, pp. 1–6, May 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.01.050. [CrossRef]

- N. Flint and R. J. Siegel, “Echo-Guided Pericardiocentesis: When and How Should It Be Performed?,” Curr Cardiol Rep, vol. 22, no. 8, p. 71, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1007/s11886-020-01320-2. [CrossRef]

- C. T. Buschmann and M. Tsokos, “Frequent and rare complications of resuscitation attempts,” Intensive Care Med, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 397–404, Mar. 2009, doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1255-9. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Pastore et al., “Bedside Ultrasound for Hemodynamic Monitoring in Cardiac Intensive Care Unit,” J Clin Med, vol. 11, no. 24, p. 7538, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.3390/jcm11247538. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Boyd, D. Sirounis, J. Maizel, and M. Slama, “Echocardiography as a guide for fluid management,” Crit Care, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 274, Dec. 2016, doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1407-1. [CrossRef]

- P. Pellicori, D. Hunter, H. H. Ei Khin, and J. G. F. Cleland, “How to diagnose and treat venous congestion in heart failure,” Eur Heart J, vol. 45, no. 15, pp. 1295–1297, Apr. 2024, doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad883. [CrossRef]

- W. Beaubien-Souligny et al., “Quantifying systemic congestion with Point-Of-Care ultrasound: development of the venous excess ultrasound grading system,” Ultrasound J, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 16, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1186/s13089-020-00163-w. [CrossRef]

- G. Tavazzi, R. Spiegel, P. Rola, S. Price, F. Corradi, and M. Hockstein, “Multiorgan evaluation of perfusion and congestion using ultrasound in patients with shock,” Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 344–352, May 2023, doi: 10.1093/ehjacc/zuad025. [CrossRef]

- M. Gaubert et al., “Doppler echocardiography for assessment of systemic vascular resistances in cardiogenic shock patients,” Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 102–107, Mar. 2020, doi: 10.1177/2048872618795514. [CrossRef]

- P. Lindqvist, S. Soderberg, M. C. Gonzalez, E. Tossavainen, and M. Y. Henein, “Echocardiography based estimation of pulmonary vascular resistance in patients with pulmonary hypertension: a simultaneous Doppler echocardiography and cardiac catheterization study,” European Journal of Echocardiography, vol. 12, no. 12, pp. 961–966, Dec. 2011, doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jer222. [CrossRef]

- A. Gamarra, P. Díez-Villanueva, J. Salamanca, R. Aguilar, P. Mahía, and F. Alfonso, “Development and Clinical Application of Left Ventricular–Arterial Coupling Non-Invasive Assessment Methods,” J Cardiovasc Dev Dis, vol. 11, no. 5, p. 141, Apr. 2024, doi: 10.3390/jcdd11050141. [CrossRef]

- R. Kazimierczyk et al., “Echocardiographic Assessment of Right Ventricular–Arterial Coupling in Predicting Prognosis of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Patients,” J Clin Med, vol. 10, no. 13, p. 2995, Jul. 2021, doi: 10.3390/jcm10132995. [CrossRef]

- R. Arntfield, J. Pace, S. McLeod, J. Granton, A. Hegazy, and L. Lingard, “Focused transesophageal echocardiography for emergency physicians—description and results from simulation training of a structured four-view examination,” Crit Ultrasound J, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 10, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1186/s13089-015-0027-3. [CrossRef]

- R. Arntfield, J. Pace, M. Hewak, and D. Thompson, “Focused Transesophageal Echocardiography by Emergency Physicians is Feasible and Clinically Influential: Observational Results from a Novel Ultrasound Program,” J Emerg Med, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 286–294, Feb. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.09.018. [CrossRef]

- R. Arntfield, V. Lau, Y. Landry, F. Priestap, and I. Ball, “Impact of Critical Care Transesophageal Echocardiography in Medical–Surgical ICU Patients: Characteristics and Results From 274 Consecutive Examinations,” J Intensive Care Med, vol. 35, no. 9, pp. 896–902, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.1177/0885066618797271. [CrossRef]

- F. Teran et al., “Resuscitative transesophageal echocardiography in emergency departments in the United States and Canada: A cross-sectional survey,” Am J Emerg Med, vol. 76, pp. 164–172, Feb. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2023.11.041. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Cavayas, M. Girard, G. Desjardins, and A. Y. Denault, “Transesophageal lung ultrasonography: a novel technique for investigating hypoxemia,” Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie, vol. 63, no. 11, pp. 1266–1276, Nov. 2016, doi: 10.1007/s12630-016-0702-2. [CrossRef]

- A. Y. Denault et al., “Transgastric Abdominal Ultrasonography in Anesthesia and Critical Care: Review and Proposed Approach,” Anesth Analg, vol. 133, no. 3, pp. 630–647, Sep. 2021, doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005537. [CrossRef]

- A. D’Andrea et al., “Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography: From methodology to major clinical applications,” World J Cardiol, vol. 8, no. 7, p. 383, 2016, doi: 10.4330/wjc.v8.i7.383. [CrossRef]

- T. Lazzarin et al., “Post-Cardiac Arrest: Mechanisms, Management, and Future Perspectives,” J Clin Med, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 259, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.3390/jcm12010259. [CrossRef]

- L. Elfwén et al., “Post-resuscitation myocardial dysfunction in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients randomized to immediate coronary angiography versus standard of care,” IJC Heart & Vasculature, vol. 27, p. 100483, Apr. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100483. [CrossRef]

- S. Rodríguez-Villar et al., “Systemic acidemia impairs cardiac function in critically Ill patients,” EClinicalMedicine, vol. 37, p. 100956, Jul. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100956. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Frasch and D. A. Giussani, “Heart during acidosis: Etiology and early detection of cardiac dysfunction,” EClinicalMedicine, vol. 37, p. 100994, Jul. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100994. [CrossRef]

- K.-C. Cha et al., “Echocardiographic patterns of postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction,” Resuscitation, vol. 124, pp. 90–95, Mar. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.01.019. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Jentzer, M. D. Chonde, and C. Dezfulian, “Myocardial Dysfunction and Shock after Cardiac Arrest,” Biomed Res Int, vol. 2015, pp. 1–14, 2015, doi: 10.1155/2015/314796. [CrossRef]

- M. Ruiz-Bailén et al., “Reversible myocardial dysfunction after cardiopulmonary resuscitation,” Resuscitation, vol. 66, no. 2, pp. 175–181, Aug. 2005, doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.01.012. [CrossRef]

- S. Desch et al., “Angiography after Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest without ST-Segment Elevation,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 385, no. 27, pp. 2544–2553, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101909. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Lemkes et al., “Coronary Angiography after Cardiac Arrest without ST-Segment Elevation,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 380, no. 15, pp. 1397–1407, Apr. 2019, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816897. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Jentzer et al., “Echocardiographic left ventricular systolic dysfunction early after resuscitation from cardiac arrest does not predict mortality or vasopressor requirements,” Resuscitation, vol. 106, pp. 58–64, Sep. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.06.028. [CrossRef]

- V. Ramjee et al., “Right ventricular dysfunction after resuscitation predicts poor outcomes in cardiac arrest patients independent of left ventricular function,” Resuscitation, vol. 96, pp. 186–191, Nov. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.08.008. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Jentzer et al., “Echocardiographic left ventricular diastolic dysfunction predicts hospital mortality after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,” J Crit Care, vol. 47, pp. 114–120, Oct. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.06.016. [CrossRef]

- W.-T. Chang et al., “Postresuscitation myocardial dysfunction: correlated factors and prognostic implications,” Intensive Care Med, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 88–95, Jan. 2007, doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0442-9. [CrossRef]

| Goals of US during CPR | Goals of US in post-resuscitation care |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis of reversible causes | Diagnosis of underlying cause of CA |

| Confirm effectiveness of chest compressions | Hemodynamic monitoring and optimization |

| Determine presence of cardiac contractions or ‘standstill’ | Assist ventilatory support |

| Confirm bilateral ventilation after intubation | Assessment of CPR complication |

| Assist invasive procedures (pericardiocentesis, vascular cannulation, extracorporeal CPR) | Assessment multiorgan function (prognosis) |

| Assist invasive procedures |

| Potential cause | US views | Suggestive findings | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Profound hypovolemia |

Subcostal Abdomen |

Small LV and RV cavity size Near end-systolic obliteration (‘kissing ventricle’) Collapsed IVC (< 10 mm) Massive bleeding in abdomen |

Fluid administration; assess response |

|

Cardiac tamponade |

Subcostal | Pericardial effusion Collapsed cardiac chambers Congested IVC |

Pericardiocentesis; guide the procedure and assess response |

| Massive pulmonary embolism | Subcostal Lower limbs |

Markedly dilated RV Pressure overload of RV Thrombus-in-transit Congested IVC Presence of DVT (positive CUS) |

Consideration of thrombolysis |

|

Tension pneumothorax |

Lung | Absence of lung sliding during ventilation | Needle decompression, assess response |

| View | Goals and diagnosis |

|---|---|

| 1. ME 4C (0-10°) | Tamponade Evaluation of LV/RV contractility Signs of PE Signs of profound hypovolemia Signs of compression due to pneumothorax |

| 2. ME LAX (120°-140°) | Determine AMC Optimization of chest compression avoiding LVOT obstruction Evaluation of AscAo |

| 3. TG SAX (0-20°) | Tamponade Evaluation of LV/RVcontractility Signs of PE Signs of profound hypovolemia; |

| 4. ME bicaval (90°) | Evaluation of intravascular volume (SCV) Thrombus in transit Assist venous procedures |

| 5. TG and ME DescAO SAX (0-10°) | Evaluation of DescAo Assist arterial procedures |

| Echocardiographic findings | Parameters |

|---|---|

| RV dilatation | RV/LV ratio > 1 RV basal diameter > 41 mm RV mid diameter > 35 mm |

| RV systolic disfunction | TAPSE < 17 mm S’ wave (TDI) < 10 cm/sec RV-FAC < 35% RV Tei index (PW) > 0.43 RV Tei index (TDI) > 0.54 RV free wall strain > -20% |

| McConnell Sign | RV basal and mid free wall akinesia and normal motion of the RV apex |

| RV pressure overload | TR Vmax > 2.9 m/sec Pulmonary flow AcT < 60 msec Pulmonary flow mid-systolic notch Paradoxical IVS motion Flattened IVS with D-shaped LV Dilated PA (> 25 mm) TAPSE: PASP ratio < 0.4 Dilated IVC (>21 mm) and/or diminished collapsibility |

| 60/60 Sign | TR jet gradient < 60 mmHg and Pulmonary AcT < 60 ms |

| Thrombus in transit | Thrombus in RV, RA or PA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).