1. Introduction

Standard macular hole surgery involves pars plana vitrectomy with peeling of the internal limiting membrane (ILM) and gas tamponade with very good anatomic outcomes and satisfactory functional outcomes.[

1,

2] Postoperative outcomes have been shown to be size-dependent and are worse in larger size macular holes.[

3] To improve closure rate, different types of flaps and different materials for flap creation have been implemented.[

4,

5] ILM flaps have the advantage of using a readily available tissue with minimal additional steps compared to standard macular hole surgery and can be used either to cover the macular hole or to fill the hole. Other types of flaps proposed include epiretinal membrane, retinal autografts or amniotic membrane. [

5,

6,

7]

Epiretinal proliferation (EP) is observed as a mound of homogenous, medium reflectivity at the retinal surface.[

8] It has been identified in over 10% of macular holes and its presence has been associated with hole chronicity, size and the presence of an epiretinal membrane. [

9] EP may also be associated with lower closure rate and worse postoperative functional and structural outcomes.[

10,

11]

We have previously reported the use of combined EP with ILM in a case of a very large macular hole that resulted in hole closure and visual acuity improvement.[

12] We describe this technique and the results in a larger series of patients to assess the safety of the technique and related outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was a prospective interventional case series and it was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. We included all patients with primary, idiopathic macular holes and a minimum linear diameter > 400 μm operated under a single surgeon firm for the period between September 2021 and January 2023. We excluded patients with recurrent or persistent macular holes, secondary macular holes (e.g. traumatic, myopic), diagnosis of other retinal disease except from macular hole and previous history of any intraocular surgery expect from cataract surgery.

Preoperatively, all patients underwent complete ophthalmic examination including best corrected visual acuity measurement (BCVA) using the ETDRS charts, intraocular pressure measurement and slit lamp biomicroscopy including dilated fundus examination. Imaging with spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed and the minimum linear diameter was calculated using the OCT software. The macular holes were graded as large (>400μm) according to the International Vitreomacular Study Group Classification.[

13] Preoperative macular OCTs were reviewed and graded for the presence of epiretinal proliferation.

Follow up visits were performed 1 day, 2 weeks, 6 weeks and 3 months postoperatively and during each visit the full set of ophthalmic examinations was performed as recorded above.

Primary study outcome was macular hole closure confirmed by OCT and secondary outcomes were BCVA improvement at the end of follow up period.

Surgical Technique

Surgeries were performed with 23g pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) setup under subtenon’s anesthesia. Combined phacoemulsification could be performed at the same time if significant lens opacity was identified preoperatively. Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) was induced using the vitreous cutter on suction mode. The central and peripheral vitreous was removed and dual blue dye (DORC International, The Netherlands) was used to stain the ILM. Negative stain confirmed the presence of epiretinal proliferation around the macular hole. ILM and EP were peeled centripetally towards the centre of the macular hole, in a petaloid fashion, leaving the petaloid flaps attached on a small hinge at the edge of the macular hole. ILM peel could be extended more peripherally in the macular area up to the arcades. Indented retinal periphery search was performed to identify any breaks and balanced salt solution was exchanged for air initially and then gas on an isovolumetric concentration. The flap could be repositioned to cover and fill the macular hole under air if needed. After surgery all patients were asked to maintain face down position during the day for 5 days and avoid supine position when sleeping.

3. Results

A total of 16 eyes of 16 patients, 2 male and 14 female, were included in our study. 14 eyes (87.5%) were phakic whereas 2 (12.5%) were pseudophakic. Mean preoperative BCVA was 1.11±0.52 logMAR and mean minimum linear diameter (MLD) of the macular holes included was 707.63±164.02μm (range 548-950μm). Mean follow-up period was 6.75±4.40 months.

Table 1 summarizes baseline patient characteristics.

Combined phacoemulsification was performed in 12 eyes (75%), whereas 4 (25%) underwent standalone PPV and peel. Posterior vitreous detachment was present in half of the eyes (50%). In the rest of the patients, it was induced intraoperatively. 10 eyes (62.5%) had C2F6 gas tamponade and 6 eyes (37.5%) had C3F8 (

Table 2).

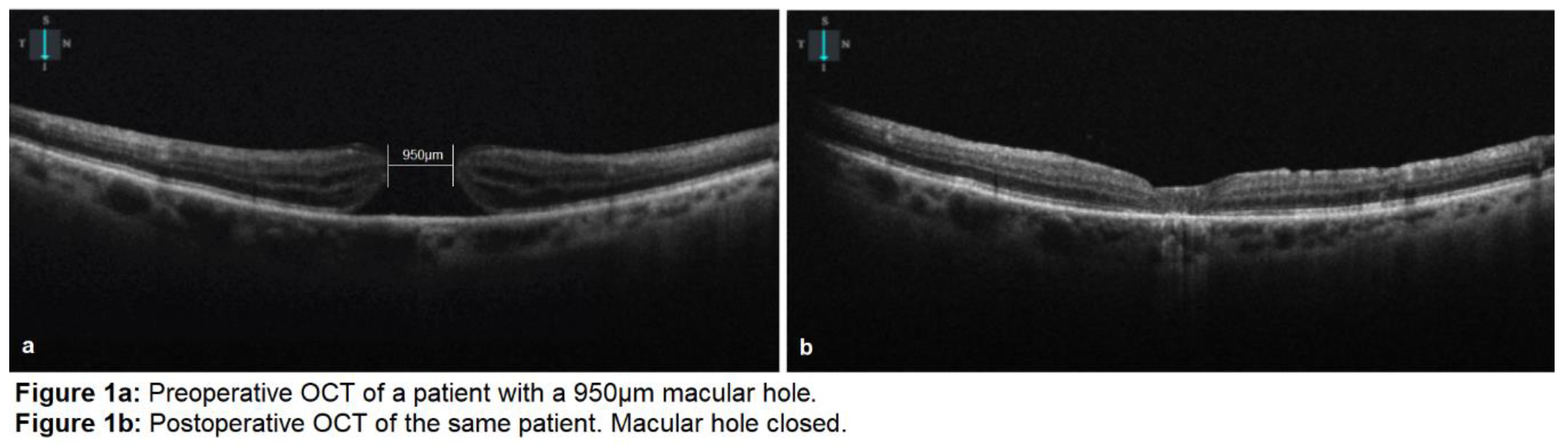

All the macular holes closed postoperatively (

Figure 1). Visual acuity improved to 0.51±0.20 logMAR (p=0.01<0.05) at 6 weeks and to 0.45±0.25 (p=0.008<0.05) at the final follow-up visit. External limiting membrane (ELM) was continuous in 6 eyes (37.5%) at 6 weeks postoperatively. At the final follow-up visit, ellipsoid zone was disrupted in all of the eyes.

Table 3 summarizes the surgical outcomes.

4. Discussion

Our study suggests that EP can be safely used as a flap material in combination with ILM to facilitate macular hole closure. There are several advantages of our technique compared to alternative flap techniques which are increasingly used for larger macular holes. Compared to traditional single ILM flap, combination with EP can provide additional tissue volume which can be used to cover and simultaneously fill the macular hole to facilitate its closure. Moreover, epiretinal proliferation material is considered to be originating from within the macular defect, its composition may be more suitable to be used as a flap and its preservation during surgery is recommended.[

14] Compared with techniques using tissue outside the macula either autologous (such as retinal autografts, posterior capsule) or allogenic (such as amniotic membrane) our technique provides with tissue that, when available, can be easily used to facilitate hole closure with minimal modification to the traditional ILM peeling technique and a short learning curve. There is no need to perform additional traumatic procedures (such as retinectomy to harvest retinal autograft) and there is no need to use material that may not be available (such as posterior capsule) or there might limitations for its intraocular use (such as amniotic membrane). Even more, considering that EP presence has been associated with macular hole duration, EP is expected to be present in a large percentage of idiopathic macular holes of a larger size as macular hole duration and size are closely related.[

3]

It can be considered that combined ILM and EP flap acts in a similar way to single ILM flap: prevents trans-hole fluid flow from the vitreous cavity and forms a scaffold for glial cell migration. However, it needs to be considered that combined, petaloid EP and ILM flap shows increased thickness compared to single ILM flap and this may facilitate hole filling with flap material and subsequent closure.

There are several limitations of our study such as the small study size and the short follow up period. Moreover, further prospective studies can analyze and compare additional parameters which might be of interest (such as BCVA, microperimetry, OCT morphology) between the combined flap technique and alternative flap techniques. EP may not be present in all large macular holes and alternative surgical approaches should be considered in these cases. Further prospective studies are needed to determine the percentage of patients this technique might be applicable to and any potential benefits for macular hole patients.

5. Conclusions

Epiretinal proliferation can be safely combined with internal limiting membrane for the creation of an inverted, petaloid flap to cover and facilitate the closure of large macular holes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org; Video S1: Surgical video showing the technique of combined epiretinal proliferation and internal limiting membrane flap during macular hole surgery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.D.; methodology N.D., I.V., E.P.P.; formal analysis P.D.; data curation N.D., P.D.; writing—original draft preparation, N.D, I.V., E.P.P.; writing—review and editing, P.D, T.S; visualization, P.D.; supervision, T.S.; project administration, N.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the proposed treatment was the standard of care for this subgroup of patients.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived for this study because the proposed treatment was the standard of care for this subgroup of patients.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Kelly NE, Wendel RT. Vitreous surgery for idiopathic macular holes: results of a pilot study. Archives of ophthalmology 1991;109:654-659. [CrossRef]

- Eckardt C, Eckardt U, Groos S, et al. Entfernung der Membrana limitans interna bei Makulalöchern Klinische und morphologische Befunde* Klinische und morphologische Befunde. Der Ophthalmologe 1997;94:545-551. [CrossRef]

- Steel D, Donachie P, Aylward G, et al. Factors affecting anatomical and visual outcome after macular hole surgery: findings from a large prospective UK cohort. Eye 2021;35:316-325. [CrossRef]

- Michalewska Z, Michalewski J, Adelman RA, Nawrocki J. Inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for large macular holes. Ophthalmology 2010;117:2018-2025. [CrossRef]

- Caporossi T, Tartaro R, Giansanti F, Rizzo S. The amniotic membrane for retinal pathologies. Insights on the surgical techniques. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 2020;258:1347-1349. [CrossRef]

- Marlow ED, Bakhsh SR, Reddy DN, et al. Combined epiretinal and internal limiting membrane retracting door flaps for large macular holes associated with epiretinal membranes. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 2022:1-4. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Dogra M, Singh SR, et al. Microscope-Integrated optical coherence Tomography–Guided autologous full-thickness neurosensory retinal autograft for large macular Hole–Related total retinal detachment. Retina 2022;42:2419-2424. [CrossRef]

- Pang CE, Spaide RF, Freund KB. Epiretinal proliferation seen in association with lamellar macular holes: a distinct clinical entity. Retina 2014;34:1513-1523. [CrossRef]

- Qi B, Yu Y, Yang X, et al. Clinical characteristics and surgical prognosis of idiopathic macular holes with epiretinal proliferation. Retina 2022:10.1097. [CrossRef]

- Bae K, Lee SM, Kang SW, et al. Atypical epiretinal tissue in full-thickness macular holes: pathogenic and prognostic significance. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2019;103:251-256. [CrossRef]

- Ubukata Y, Imai H, Otsuka K, et al. The Comparison of the surgical outcome for the full-thickness macular hole with/without lamellar hole-associated epiretinal proliferation. J Ophthalmol. 2017; 2017: 9640756. [CrossRef]

- Dervenis N, Dervenis P. Letter to the editor relating to Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2022 260: 2433–2436:“Combined epiretinal and internal limiting membrane retracting door flaps for large macular holes associated with epiretinal membranes”. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 2023;261:589-591. [CrossRef]

- Duker JS, Kaiser PK, Binder S, et al. The International Vitreomacular Traction Study Group classification of vitreomacular adhesion, traction, and macular hole. Ophthalmology 2013;120:2611-2619. [CrossRef]

- Lai T-T, Chen S-N, Yang C-M. Epiretinal proliferation in lamellar macular holes and full-thickness macular holes: clinical and surgical findings. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 2016;254:629-638. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).