Over the years, cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) have expanded their usefulness beyond the initial use of pacing in bradycardia to encompass a range of cardiac conditions, including heart failure and the prevention of sudden cardiac death; More than 730,000 permanent pacemakers (PPMs) and 330,000 implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) are implanted annually worldwide1. In Europe, more than 3.8 PPMs per million inhabitants, 2.2 ICD and 1.8 cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) devices are implanted yearly2. These numbers are likely to increase as the population continues to grow older and cardiovascular comorbidities become more prevalent.

Cardiac implantable electronic devices can be divided into three main groups. Permanent pacemakers (PPM) are the only effective treatment for bradyarrhythmia’s consisting of a subcutaneous pulse generator and at least one lead which usually passes into the right ventricle. Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) help prevent life threatening and require thicker leads to be able to deliver higher intensity shocks. At last, cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) coupled with a defibrillator (CRT-D) or pacing (CRT-P) function have been shown to improve outcomes in heart failure patients by reestablishing interventricular synchrony. To be able to achieve this it includes three leads in the right atrium, right ventricle and coronary sinus (for left ventricle pacing).

Tricuspid regurgitation (TR) following the implantation of CIEDs is becoming an increasingly recognized clinical concern. It can develop in a significant proportion of patients after CIED implantation, with studies showing incidence rates as high as 44%3. Additionally, TR associated with CIEDs is being gradually recognized as an important clinical condition related to an elevated risk of heart failure and mortality4.

This narrative review aims to bridge the gap between the clear, unquestionable benefit of CIEDS and the long-term risk associated with tricuspid regurgitation focusing on pathophysiology, prognosis and prevention. To achieve this, a broad and thorough search was conducted on PubMed, Scopus, and Embase from inception to July 2024, by 2 authors. Hand searching for relevant articles was done on reference lists from textbooks, articles, and scientific proceedings. A combination of keywords and medical subject headings (MeSH) were used in the search, such as “tricuspid regurgitation after CIED,” “pacing,” “cardiac implantable devices,” or “defibrillator” AND “tricuspid regurgitation after CIED/prognosis” “tricuspid regurgitation after CIED/mortality” OR “tricuspid regurgitation after CIED/epidemiology” OR “tricuspid regurgitation after CIED/risk factors” OR “tricuspid regurgitation after CIEDs AND “chronic kidney disease” OR “atrial fibrillation” OR “diabetes”. Data extraction was done independently by 2 authors using standardized data extraction forms. When more than one publication of a study was found, only the publication with the most complete data was included. Extracted data included identifiable information, study outcomes, details of the study protocol, and demographic data.

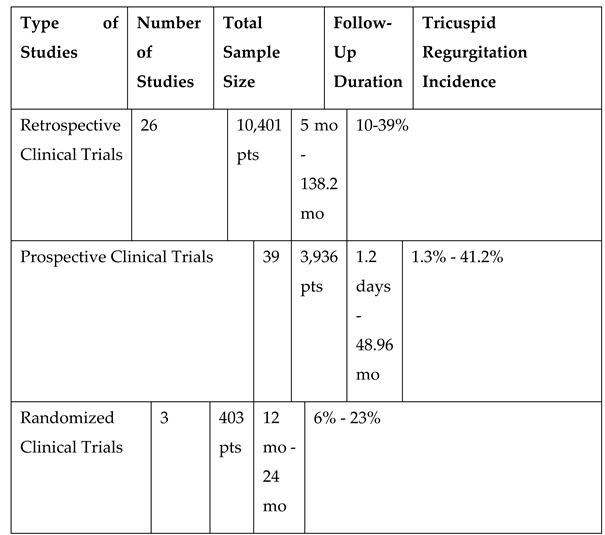

This review included all eligible studies such as reviews, commentaries, editorials, and retrospective clinical studies, prospective or randomized controlled trials that are published in English. On the other hand, unpublished studies, and topics unrelated to the criteria were excluded. The included studies focused on adult patients aged 18 years or older with cardiac implantable electronic devices who developed tricuspid regurgitation, with at least one measure of epidemiology, prognosis and/or its association with heart failure and mortality (

Table 1).

Mechanisms

Tricuspid regurgitation following CIED implantation is mainly derived from several main underlying mechanism: implantation related, pacing related or device related.

The main cause of acute valve dysfunction is leaflet impingement, described as mechanical interference with leaflet mobility determined by the ventricular lead 5. In a case series which included patients who required surgical valvular repair for severe TR caused by CIED, 39% had leaflet impingement, with the second most common finding being lead adherence to the valve, present in 34% of patients. Leaflet perforation occurred in 17% of cases, while lead entanglement in the subvalvular apparatus occurred in only 10% of the patients6.

Right ventricular stimulation opposes the normal depolarization of the ventricles and causing the left bundle branch block pattern on the electrocardiogram. These electrical changes also translate into mechanical abnormalities defined as ventricular dyssynchrony. In time, the abnormal depolarization and subsequent contraction is responsible for right ventricle dilatation which results in inadequate valve coaptation.

At last, the presence of the lead can lead to fibrosis and exposes the patient to a higher risk of endocarditis; additionally, repeated embolization of thrombi from cardiac leads can cause pulmonary hypertension and tricuspid regurgitation due to right ventricular enlargement. Finally, when necessary, transvenous lead extraction poses a high-risk complication such as valve avulsion2.

Given that tricuspid regurgitation is a relatively common echocardiographic finding, the distinction between CIED associated TR and CIED related TR is of outmost importance. In the first case, the presence of a CIED lead across the tricuspid valve can coexist with TR without a clear cause-effect relationship between the two, and the evolution of the valve disease is dependent on the usual risk factors. However, when TR appears or worsens after implantation (CIED related tricuspid regurgitation) a causal effect could be assumed. Still, to establish causality in CIED related TR, there must be proof of valve-lead interaction 2.

Epidemiological Data

The incidence of TR after CIEDs implantation is not exactly established and varies from 7.2% to 44.7% 3. Reported incidences ranged from 30.6%, or even 38% reported by Höke et al. to 21.2% found by Kim et al. or 13% found by Seo et al. The different definitions of significant TR and TR progression are the main reasons for discrepancies in various studies. Some studies evaluate all grades of tricuspid regurgitation, while others consider worsening TR as progression to moderate or severe levels following CIED implantation.

The largest review to date, conducted in 2023, included more than 66,000 subjects and showed that patients who received device implantation (n=1,008) were significantly more predisposed to worsening tricuspid regurgitation compared to controls (OR 3.18; P < .01)7. Among 7,777 patients, the pooled incidence of at least a 1-grade worsening of tricuspid regurgitation following device implantation was 24%. A recent meta-analysis and meta-regression of 52 studies (3 RCTs, 18 prospective studies, and 31 retrospective studies) with a combined total of 37,350 patients, founded a 24% incidence of a ≥1-grade intensification in CIED-associated tricuspid regurgitation 8. The total estimated incidence for a ≥2 grade increase was 11% (95% CI 6% to 15%, p <0.001). Strikingly, patients with a CIED had a higher risk of developing new or worsening TR in comparison to those without CIEDs (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.58 to 3.77, p <0.001). The risk of CIED-associated TR did not significantly differ between patients with PPMs and those with ICDs (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.11, p = 0.175)3

Device Type and Lead Features

Studies have found varying relationships between lead type and the risk of TR. In a meta-analysis by Zhang et al., the global incidence of TR was greater with ICDs than PPMs (29.18% vs. 22.68%), presumably because of thicker and stiffer ICD leads, but the difference was not statistically significant9. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Alnaimat et al. also found no statistically significant difference between lead type and risk of TR (OR 1.12; 95% CI 0.57–2.18; P = .71)7. Interestingly, two studies which were included in this analysis, conducted by Leibowitz et al10 and Wiechecka et al11 examined patients during the second- and seventh-day post-implantation and found worsening tricuspid regurgitation rates of 11.4% and 15.4% respectively. The rates reported in these two studies are lower than the ones outlined by studies with longer follow-up periods. These findings might suggest that worsening TR post-implantation could take several months to manifest.

Theoretically, leadless pacemakers (LPs) may decrease the frequency of TR by avoiding lead–leaflet interaction and impingement. However, currently reported data are conflicting. After conducting echocardiographic evaluations on patients both before and after LP implantation, Beurskens et al compared the results with those from age- and sex-matched controls who had dual-chamber (DDD) transvenous pacemakers. The findings revealed that 43% (N=23) of patients experienced more severe TR at follow-up (12±1 months) than at baseline12. Furthermore, increased MV regurgitation was observed in 38% of LP patients (P=0.006). LP therapy unexpectedly resulted in an increase in TV dysfunction, similar to the changes observed in patients with DDD transvenous pacemakers, and negatively affected MV and biventricular function.

The mechanism is not completely understood, but may involve valve impairment during implantation, mechanical stress of the device on the TV or its subvalvular apparatus, or pacing-induced RV dyssynchrony. By contrast, Vaidya et al reported data derived from ninety patients who underwent LP implantation, after a median follow-up duration of 62 days; 19% of patients with transvenous pacemakers had worsening TR by 2 or more grades while none of the patients who received LPs experienced significant changes in TR (P = 0.017)13.

While historically, CIED-related TR has been considered a primary tricuspid regurgitation, pathophysiological particularities call for it to be reclassified as a distinct category14 . Lead interaction with the valvular leaflets poses common mechanisms with primary causes of regurgitation, whereas chronic desynchrony with subsequent right ventricle remodeling is similar to secondary TR.

Prognostic Impact of Tricuspid Regurgitation

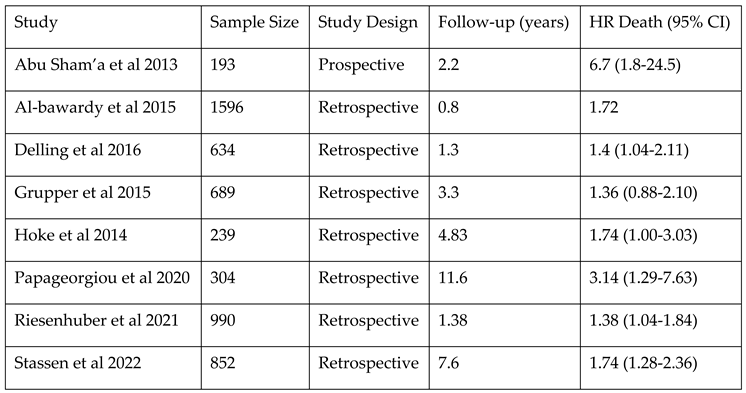

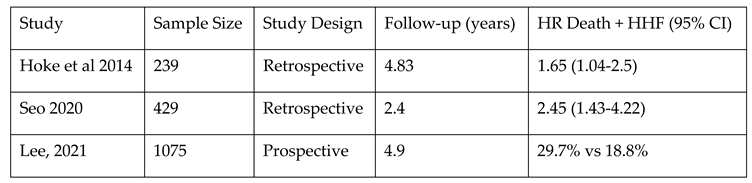

The main studies that

estimate the mortality risk associated with TR after CIED are presented in

Table 2. The study performed by Delling et al. underlined that the risk of developing TR is twice as high after PPM implantation, even after accounting for factors like age, cardiac co-morbidities and common factors of secondary TR. PPM-related TR was associated with increased mortality over a median follow-up period of 1.6 years compared with patients with PPM who did not develop TR

15 Offen et al. analyzed data from the National Echocardiography Database Australia (NEDA), consisting of 18,797 adults with a CIED and 439,558 without, who underwent echocardiographic evaluations over a period of 20 years. The study highlights the following key findings: 1) at least moderate CIED-associated TR is highly prevalent (23.8%), occurring twice as often than in patients without devices; 2) it is linked to a 1.6 to 2.5-fold higher risk of all-cause mortality compared to those without TR even after adjusting for factors such as age, sex, left-heart disease or atrial fibrillation, with a particularly significant impact on younger individuals and 3) the grade of TR is more decisive than the cause of TR in determining outcomes; the observed mortality was similar among patients with TR, regardless of whether a device lead was present or not.

16. There is an association between even mild CIED-associated TR and higher mortality rates, with aHR of 1.11 [1.06 to 1.17] for mild TR, 1.62 [1.53 to 1.72] for moderate TR, and 2.42 [2.25 to 2.61] for severe TR.

In a recent meta-analysis including 8 studies with a median follow-up period of 53 months, pooled adjusted HR for all-cause mortality associated with significant TR post-CIED was 1.64 (1.40–1.90) (P < 0.001, I2 30.28%, and Egger’s test P-value = 0.088)17. In the first meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis and thereby, the largest study to date evaluating the true incidence and prognostic implications of CIED-associated TR, similar data were found8. The study revealed that CIED-associated TR was linked to a 52% increased risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted HR [aHR] 1.52, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.69, p ≤0.001). The risk was even higher (69%) for patients who had at least moderate CIED-associated TR (aHR 1.69, 95% CI 1.40 to 2.04, p ≤0.001)8.

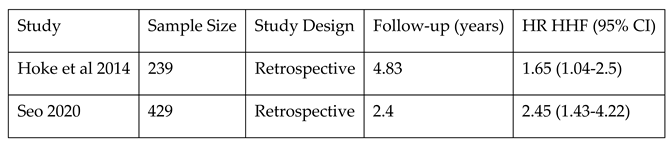

Additionally, CIED-related TR might determine remodeling of the right heart and worsened RV function and with more frequent hospitalization for heart failure (see

Table 3). In a single-center observational study with a relatively small sample size (N=165), Kanawati et al. reported that patients who developed CIED-related TR presented a higher rate of heart failure hospitalizations (63,6%), compared to those that did not develop CIED-related TR (34.7% (p=0.001), the results being confirmed over long-term follow-up

18. Their secondary analysis highlighted that the risk of hospitalization for heart failure increases only after 12 months post-CIED implantation (HR 1.99, p=0.034).

In 2014, Hoke et al. reported a significantly higher rate of a composite outcome of survival and/or heart failure related events (HR=1.641, p=0.019) in patients with CIED-Related TR

19. T

he previously mentioned meta-regression analysis revealed similar results, indicating that CIED-associated TR was independently linked to an increased risk of both heart failure hospitalizations and a composite outcome of all-cause mortality and heart failure hospitalizations (aHR 1.82, 95% CI 1.19 to 2.78, p = 0.006 and aHR 1.96, 95% CI 1.33 to 2.87, p = 0.001, respectively)

8 – see

Table 4.

Comorbidities, Tricuspid Regurgitation after CIED and Their Prognostic Impact

Recognizing the influence of comorbidities on TR after CIED implantation is crucial for assessing risk and managing patient outcomes. In this section, we explore how the presence of certain comorbidities can influence the development and progression of TR, and evaluate their prognostic impact regarding mortality and heart failure hospitalization (HHF). Most of studies that we analyzed focused on coronary artery disease, heart failure, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease.

In the analyzed studies the incidence of coronary artery disease (CAD) varies between 3% to 70%. Delling et al showed that permanent pacemaker recipients are more likely to have CAD (41% vs 21%)15 , while Al-Bawardy noticed a higher mortality risk associated with a history CAD20. The number of heart failure patients also varies widely between studies from 20% up to 100% in studies focused on CRTs. Chodor et al included 40.6% patients with heart failure, however they noticed that left ventricular ejection fraction did not influence the survival rate in the TR-progression group3. In contrast, Abu Sham’a noticed that there is no difference in mortality based on NYHA class or ejection fraction21.

Similarly, hypertension is another comorbidity frequently taken into consideration. Although Delling et al showed that hypertensive patients are more likely to be needing cardiac pacing, it was not significantly correlated with tricuspid regurgitation15. Moreover, it doesn’t seem to influence either heart failure hospitalization nor mortality18.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease seems to be less prevalent in the studied groups (4.7%-15%). Kanawati et al included 48 patients with lung disease. Their results show that it was associated with heart failure hospitalization only after 12 months of follow-up (HR 2.93; 1.51-5.69; p=0.002)18.

The available data regarding the influence of atrial fibrillation (AF) on tricuspid regurgitation is conflicting. While some studies recommend AF as an independent predictor of TR, with amplified incidence detected in patients with persistent AF, others describe no significant association. A retrospective analysis of 2533 patients who underwent PPM implantation showed that only AF (HR: 2.07, 95% CI: 1.27-4.09) and a history of open-heart surgery (HR: 3.34, 95% CI: 1.68-6.68) were predictors of lead related TR22. Cho et al studied predictors of moderate to severe TR in a population of 530 patients with CIEDs and with or without structural heart disease. Persistent AF was recognized as an independent predictor of tricuspid regurgitation, with the main incidence detected in both patient groups: 21.8% in those with structural heart disease and 18.6% in those without23. Similarly, in their prospective study, Van De Heyning et al found that only AF is associated with tricuspid regurgitation after cardiac device implantation after adjusting for baseline TR grade24. However, a retrospective study on 1670 patients failed to show a significant association between AF and progressive tricuspid regurgitation or heart failure hospitalisation25. A meta-analysis of 37 studies adding up to 8144 patients found that there was no significant statistical association between tricuspid regurgitation after PPM implantation and baseline AF, age, LVEF or baseline mild TR 9. However, the authors did notice that all-cause mortality after one year of follow-up was higher in the group that experienced progression of TR9. In their univariate analysis, Riesenhuber et al failed to show an association between atrial fibrillation and mortality26.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) seems to also be an important prognostic factor. In the retrospective study of Lee et al, DM was associated with hospitalization for heart failure in univariable analysis. However, in multivariable analysis, only age, renal impairment (>stage 3) and larger LVEDV were independently linked to HF hospitalization25. In another study developed by Riesenhuber et al, they noticed lower survival at 10 years in women with diabetes compared to women without (43.7% vs 55.2%, p<0.001)27.

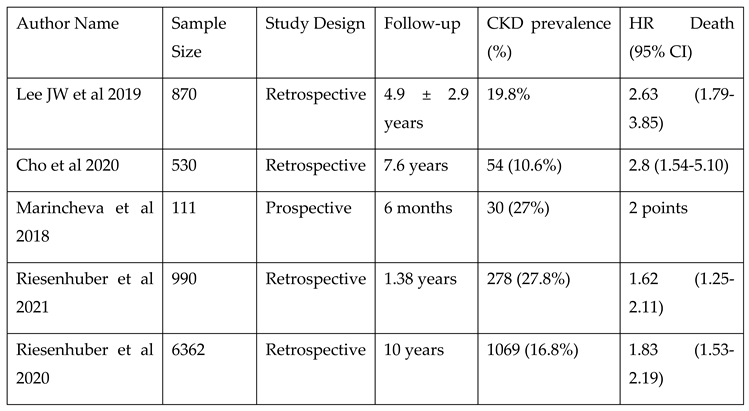

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) could be a notable comorbidity in patients with TR after CIEDs. Patients with CKD are at a higher risk of developing TR after CIED implantation. Moreover, CKD is associated with a higher mortality rate in these patients (see

Table 5). In a retrospective cohort study, the progression of TR in 990 patients with and without pre-existing right ventricular dilatation undergoing pacemaker implantation were analyzed. CKD was an independent survival predictor in patients with TR after CIEDs (HR 1.62; 95% CI 1.25–2.11;

P < 0.001); other predictors included lead-associated TR, mitral regurgitation, heart failure, and age ≥ 80 years

26.

Comparable results were observed in a retrospective, single-center cohort study involving 6,362 patients with PPM. The study shows that the rates of device and lead replacements were higher in patients with cardiovascular comorbidities, including coronary artery disease, heart failure, hypertension, valvular heart disease, prior stroke/TIA, atrial arrhythmias, or CKD27. In a multivariate COX regression, CKD was independently associated with a decreased 10-year survival: HR 1.83, 95% CI 1.53–2.19. Additionally, in large cohort of 1670 patients (27.8 % with CKD), Wei-Chieh Lee et al. reported that moderate to severe CKD (stages 3-5) was an independent predictor of HF hospitalization in multivariate analysis (HR: 1.865; 95% CI: 1.008–3.450; p = .047)

25.

Strategies to Minimize the Risk of Tricuspid Regurgitation

As the prime mechanism of lead related tricuspid regurgitation is the presence of a lead across the valve, the first measures to prevent this issue are related to the procedure. There are three main ways to place an RV lead: “direct crossing technique” where the tip is advanced directly towards the apex, “drop-down technique” where the tip is advanced through the TV, but curved towards the right ventricular outflow tract, and “prolapsing technique” where the lead is curved so that at first only the body is inserted into the ventricle and is then followed by the tip. Of all three techniques, only the third may reduce damage to the tricuspid leaflets5. Furthermore, lead placement in the ventricle impacts TR in two ways. Firstly, non-apical pacing (leads fixed on the septum or on the RV outflow tract) results in a more physiological pacing and decreases dyssynchrony which may counteract the secondary nature of lead related TR. Second, non-apical placed leads affect the way in which the body of the wire interacts with the valvular leaflets5.

Yu et al showed the way that the placement of the lead influences tricuspid regurgitation. They found that leads passing through the middle of the valve were less likely to increase TR, followed by leads that had a commissural position, while leads impending on one of the leaflets were associated with the highest proportion of TR increase. What is more, apical leads are more likely to impede on a leaflet compared to non-apical leads, which were more likely to be positioned in the middle of the valv28. Current implantation techniques using fluoroscopy do not allow for an accurate visualization of the tricuspid valve and its interaction with the pacing lead. It was proposed that transesophageal echocardiography could be used to aid lead implantation. The PLACE Pilot study recruited 21 patients who underwent TEE-assisted lead implantation (in addition to fluoroscopy) and compared the results to a historical control group of 103 patients. Lead placement in a commissure was possible in 20 patients. At discharge, none of the active-arm patients showed an increase in TR severity, while in the control group TR worsened by one grade in 13,6% of patients and by more than two grades in 6,8%29.

With regards to tricuspid regurgitation, His bundle pacing has two main advantages. Firstly, depending on the site of the block, it may not be necessary to insert a lead across the TV and second, pacing the conduction system directly minimizes interventricular dyssynchrony. The risk of developing new TR seems to be low, and more importantly, there might even be an improvement in pre-existing TR30.

Currently, there is no established strategy to prevent or reduce the incidence of CIED-induced TR. Since the positioning of the lead contributes to the leak, it is advisable to place the lead at the center of the valve or in the commissural areas and ensure that it does not obstruct leaflet movement. Although echocardiographic guidance during CIED implantation has been suggested, its implementation is challenging, and lead positions can change over time. Performing a transthoracic echocardiogram immediately after implantation and regularly during follow-up may help detect CIED-induced TR early, before fibrosis develops. Exploring alternatives such as leadless pacemakers, coronary sinus leads, epicardial stimulation, or subcutaneous ICDs could also be beneficial options.

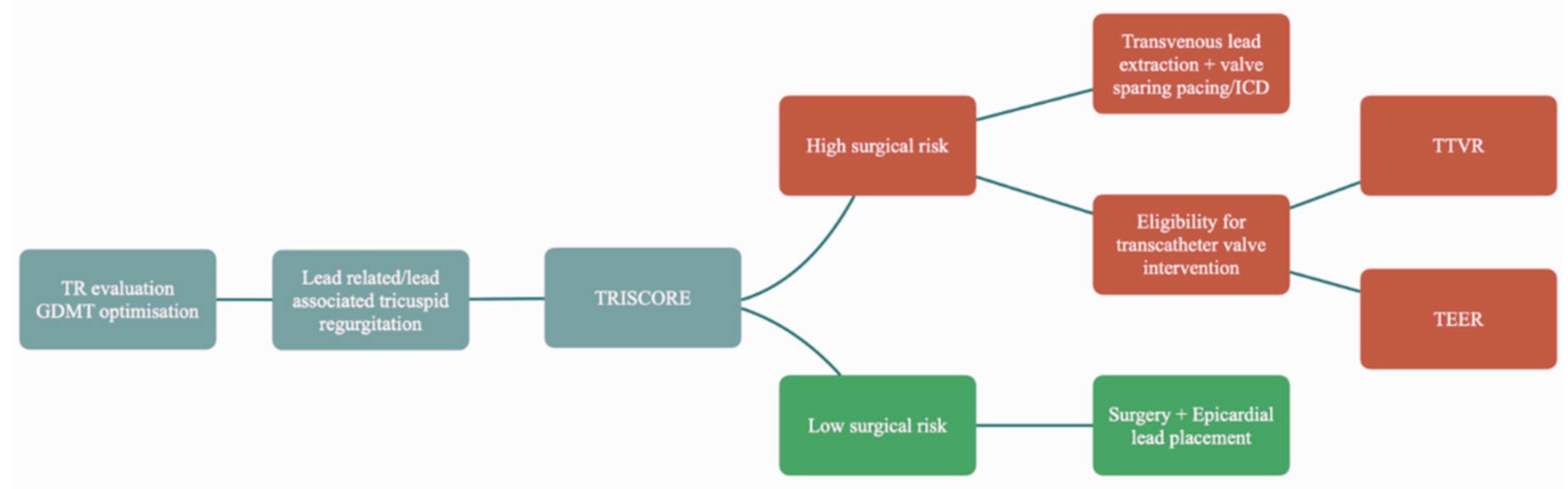

Another unanswered question is how to address patients with TR induced by a CIED (

Figure 1). The first steps are evaluation of the severity of the tricuspid regurgitation and optimizing guideline directed medical therapy. If the patient remains symptomatic next steps should be considered

31 .The most obvious answer would be to remove the lead. However, in reality the problem is much more complex. Lead’s involvement in the mechanism of the regurgitation should be clearly demonstrated before transvenous lead extraction (TLE)

2. Otherwise, this would deliver an already invasive procedure unsuccessful. An observational study on four cases showed little to no benefit of TLE in three of the patients. Furthermore, the authors showed that annular dilatation is linked to a worse response

32. In a cohort of 119 patients with lead related tricuspid dysfunction followed for approximately 5 years after lead extraction, Polewczyk showed a decrease of TR in only 35.29% of patients. These patients were shown to have better survival rates compared to the group with no significant change

33. Additionally, this procedure carries risks such as damaging the subvalvular apparatus or the valve itself, which could worsen the leak especially after a longer lead dwell time

2.

Beyond transvenous lead extraction, further management should be according to the patient’s individual characteristics. Surgical risk should be calculated using validated scores (TRISCORE34). In patients with a low surgical risk and especially in cases in which there is a mixed etiology of the leak, surgery is advisable as it seems that lead related tricuspid regurgitation has better outcomes compared to the other etiologies35. Furthermore, the mere presence of the lead adds complexity to the procedure as separation is needed sometimes by blunt dissection. This might lead to damage of the leaflet requiring reconstruction2.

In cases where there is a high surgical risk TLE should be considered alongside with minimally invasive interventions. Transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER), can only be performed in selected patients, and while transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement (TTVR) holds promise, there is currently limited clinical experience with this approach36.

Conclusions

While lead related tricuspid regurgitation and its pathophysiological cascade cast a grim shadow on prognosis, the benefits of cardiac implantable electronic devices are non-disputable. Pacemakers remain the only effective treatment tool for bradyarrhythmias, while CRTs and ICDs significantly improve mortality rates. When there is a correct clinical indication and an accurate patient selection for CIEDs and after all measures to minimize the impact have been taken, tricuspid regurgitation could be considered a necessary evil.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.I., L. V., A.C. (Adrian Covic); methodology, S.I., L. V., A.C. (Adrian Covic); investigation, S.I., L. V., A.C. (Adrian Covic); resources, S.I., L. V., A.C. (Adrian Covic); writing—original draft preparation, S.I., L. V., A.C., A.M. C (Alexandra Covic); writing—review and editing, L.V., A.C. (Adrian Covic), C.S.; supervision, A.C. (Adrian Covic); project administration, A.C. (Adrian Covic). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant of the Ministry of Research and Innovation, CNCS-UEFISCDI, project number PN-III-P4-ID-PCE-2020-2393, within PNCDI III.

Scientific research funded by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy "Grigore. T. Popa" Iasi, project number. 10841/20.05.2022

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

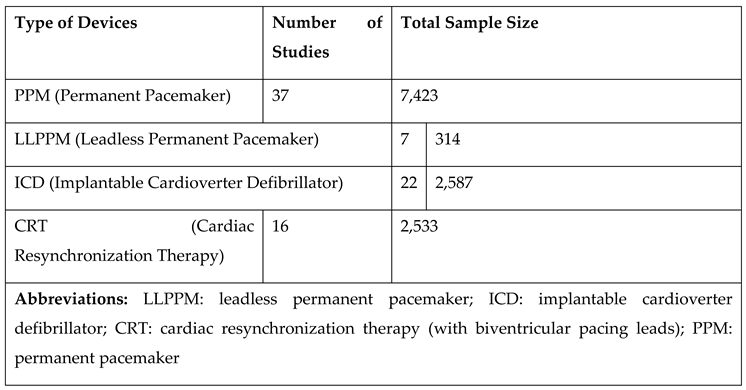

Device Types Used in the Studies

References

- Mond, H.G.; Proclemer, A. The 11th World Survey of Cardiac Pacing and Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators: Calendar Year 2009–A World Society of Arrhythmia’s Project. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 2011, 34, 1013–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreas, M.; Burri, H.; Praz, F.; et al. Tricuspid valve disease and cardiac implantable electronic devices. Eur Heart J. 2024, 45, 346–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chodór-Rozwadowska, K.; Sawicka, M.; Morawski, S.; Kalarus, Z.; Kukulski, T. Tricuspid regurgitation (TR) after implantation of a cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED)-one-year observation of patients with or without left ventricular dysfunction. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieitez, J.M.; Monteagudo, J.M.; Mahia, P.; et al. New insights of tricuspid regurgitation: A large-scale prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021, 22, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelves-Meza, J.; Lang, R.M.; Valderrama-Achury, M.D.; et al. Tricuspid regurgitation related to cardiac implantable electronic devices: An integrative review. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2022, 35, 1107–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, G.; Nishimura, R.A.; Connolly, H.M.; Dearani, J.A.; Sundt 3rd, T.M.; Hayes, D.L. Severe symptomatic tricuspid valve regurgitation due to permanent pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator leads. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005, 45, 1672–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaimat, S.; Doyle, M.; Krishnan, K.; Biederman, R.W.W. Worsening tricuspid regurgitation associated with permanent pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of more than 66,000 subjects. Heart Rhythm. 2023, 20, 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiriyu, I.; Mehta, A.; Adefuye, M.; et al. Incidence and prognostic implications of cardiac-implantable device-associated tricuspid regurgitation: A meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis. Am J Cardiol 2023, 209, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Wei, M.; Xiang, R.; et al. Incidence, risk factors, and prognosis of tricuspid regurgitation after cardiac implantable electronic device implantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2022, 36, 1741–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibowitz, D.W.; Rosenheck, S.; Pollak, A.; Geist, M.; Gilon, D. Transvenous pacemaker leads do not worsen tricuspid regurgitation: A prospective echocardiographic study. Cardiology 2000, 93, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiechecka, K.; Wiechecki, B.; Kapłon-Cieślicka, A.; et al. Echocardiographic assessment of tricuspid regurgitation and pericardial effusion after cardiac device implantation. Cardiol J. 2020, 27, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beurskens, N.E.G.; Tjong, F.V.Y.; de Bruin-Bon, R.H.A.; et al. Impact of leadless pacemaker therapy on cardiac and atrioventricular valve function through 12 months of follow-up. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2019, 12, e007124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidya, V.R.; Dai, M.; Asirvatham, S.J.; et al. Real-world experience with leadless cardiac pacing. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2019, 42, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.T.; Badano, L.P.; Bartko, P.E.; et al. Tricuspid regurgitation: Recent advances in understanding pathophysiology, severity grading and outcome. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022, 23, 913–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delling, F.N.; Hassan, Z.K.; Piatkowski, G.; et al. Tricuspid regurgitation and mortality in patients with transvenous permanent pacemaker leads. Am J Cardiol. 2016, 117, 988–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offen, S.; Strange, G.; Playford, D.; Celermajer, D.S.; Stewart, S. Prevalence and prognostic impact of tricuspid regurgitation in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices: From the national echocardiography database of Australia. Int J Cardiol 2023, 370, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuyun, M.F.; Joseph, J.; Erqou, S.A.; et al. Evolution and prognosis of tricuspid and mitral regurgitation following cardiac implantable electronic devices: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanawati, J.; Ng, A.C.C.; Khan, H.; et al. Long-term follow-up of mortality and heart failure hospitalisation in patients with intracardiac device-related tricuspid regurgitation. Heart Lung Circ. 2021, 30, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höke, U.; Auger, D.; Thijssen, J.; et al. Significant lead-induced tricuspid regurgitation is associated with poor prognosis at long-term follow-up. Heart. 2014, 100, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bawardy, R.; Krishnaswamy, A.; Rajeswaran, J.; et al. Tricuspid regurgitation and implantable devices. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2015, 38, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Sham’a, R.; Buber, J.; Grupper, A.; et al. Effects of tricuspid valve regurgitation on clinical and echocardiographic outcome in patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace. 2013, 15, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo J, Kim DY, Cho I, Hong Geu-Ru and Ha JW, Shim CY. Prevalence, predictors, and prognosis of tricuspid regurgitation following permanent pacemaker implantation. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0235230. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7319337/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.S.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.B.; Nam Gi-Byoung Choi, K.J.; Kim, Y.H. Incidence and predictors of moderate to severe tricuspid regurgitation after dual-chamber pacemaker implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2019, 42, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Heyning, C.M.; Elbarasi, E.; Masiero, S.; et al. Prospective study of tricuspid regurgitation associated with permanent leads after cardiac rhythm device implantation. Can J Cardiol. 2019, 35, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.C.; Fang, H.Y.; Chen, H.C.; et al. Progressive tricuspid regurgitation and elevated pressure gradient after transvenous permanent pacemaker implantation. Clin Cardiol. 2021, 44, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesenhuber, M.; Spannbauer, A.; Gwechenberger, M.; et al. Pacemaker lead-associated tricuspid regurgitation in patients with or without pre-existing right ventricular dilatation. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021, 110, 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesenhuber, M.; Spannbauer, A.; Rauscha, F.; et al. Sex differences and long-term outcome in patients with pacemakers. Front Cardiovasc Med 2020, 7, 569060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.J.; Chen, Y.; Lau, C.P.; et al. Nonapical right ventricular pacing is associated with less tricuspid valve interference and long-term progress of tricuspid regurgitation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2020, 33, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gmeiner, J.; Sadoni, S.; Orban, M.; et al. Prevention of pacemaker lead-induced tricuspid regurgitation by transesophageal echocardiography guided implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021, 14, 2636–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.M.J.; Sohail, H.; Satti, D.I.; et al. Tricuspid regurgitation in His bundle pacing: A systematic review. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2022, 27, e12986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.T.; Wilkoff, B.L.; Kodali, S.; et al. Managing Implanted Cardiac Electronic Devices in Patients With Severe Tricuspid Regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024, 83, 2002–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazmul, M.N.; Cha, Y.M.; Lin, G.; Asirvatham, S.J.; Powell, B.D. Percutaneous pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator lead removal in an attempt to improve symptomatic tricuspid regurgitation. EP Europace. 2013, 15, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polewczyk A, Jacheć W, Nowosielecka D, et al. Lead dependent tricuspid valve dysfunction-risk factors, improvement after transvenous lead extraction and long-term prognosis. J Clin Med. 2021;11(1):89. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8745716/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyfus, J.; Audureau, E.; Bohbot, Y.; et al. TRI-SCORE: A new risk score for in-hospital mortality prediction after isolated tricuspid valve surgery. Eur Heart J. 2022, 43, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saran N, Said SM, Schaff H V..; et al. Outcome of tricuspid valve surgery in the presence of permanent pacemaker. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018, 155, 1498–1508.e3. [CrossRef]

- Sorajja, P.; Whisenant, B.; Hamid, N.; et al. Transcatheter Repair for Patients with Tricuspid Regurgitation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023, 388, 1833–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vij, A.; Kavinsky, C.J. The Clinical Impact of Device Lead–Associated Tricuspid Regurgitation: Need for a Multidisciplinary Approach. Circulation. 2022, 145, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Lu, W.; Chen, K.; et al. Long-term follow-up results of patients with left bundle branch pacing and exploration for potential factors affecting cardiac function. Front Physiol. 2022, 13:996640. [CrossRef]

- Javed, N.; Iqbal, R.; Malik, J.; Rana, G.; Akhtar, W.; Zaidi, S.M.J. Tricuspid insufficiency after cardiac-implantable electronic device placement. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2021, 11, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvardeen, K.; Rao, R.; Hazra, S.; et al. Lead-specific features predisposing to the development of tricuspid regurgitation after endocardial lead implantation. CJC Open. 2019, 1, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupper, A.; Killu, A.M.; Friedman, P.A.; et al. Effects of tricuspid valve regurgitation on outcome in patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2015, 115, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Iannaccone, A.; Kaye, G.; et al. Effect of right ventricular pacing on right ventricular mechanics and tricuspid regurgitation in patients with high-grade atrioventricular block and sinus rhythm (from the Protection of left ventricular function during right ventricular pacing study). Am J Cardiol. 2015, 116, 1875–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleifer, J.W.; Pislaru, S.V.; Lin, G.; et al. Effect of ventricular pacing lead position on tricuspid regurgitation: A randomized prospective trial. Heart Rhythm. 2018, 15, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, A.; Sanati, H.R.; Haji-Karimi Majid Yazdi, A.H.; Rad, M.A.; Haghjoo, M.; Emkanjoo, Z. Induction and aggravation of atrioventricular valve regurgitation in the course of chronic right ventricular apical pacing. Europace. 2011, 13, 1587–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salaun, E.; Tovmassian, L.; Simonnet, B.; et al. Right ventricular and tricuspid valve function in patients chronically implanted with leadless pacemakers. Europace. 2018, 20, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothschild, D.P.; Goldstein, J.A.; Kerner Nathan Abbas, A.E.; Patel, M.; Wong, W.S. Pacemaker-induced tricuspid regurgitation is uncommon immediately post-implantation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2017, 49, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukarslan, N.; Kirilmaz, A.; Ulusoy, E.; Yokusoglu, M.; Gramatnikovski, N.; Ozal Ertugrul Tatar, H. Tricuspid insufficiency does not increase early after permanent implantation of pacemaker leads. J Card Surg. 2006, 21, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabi, P.; Özer, N.; Ateş, A.H.; Yorgun, H.; Oto, A.; Aytemir, K. Effects of pacemaker and implantable cardioverter defibrillator electrodes on tricuspid regurgitation and right sided heart functions. Cardiol J. 2015, 22, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemayat, S.; Shafiee, A.; Oraii, S.; Roshanali, F.; Alaedini, F.; Aldoboni, A.S. Development of mitral and tricuspid regurgitation in right ventricular apex versus right ventricular outflow tract pacing. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2014, 40, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marincheva, G.; Levi, T.; Brezinov, O.; et al. Echocardiography-guided Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Implantation to Reduce Device Related Tricuspid Regurgitation: A Prospective Controlled Study. Isr Med Assoc J 2022, 24, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Poorzand, H.; Tayyebi, M.; Hosseini, S.; Bakavoli, A.H.; Keihanian, F.; Jarahi Lida Hamadanchi, A. Predictors of worsening TR severity after right ventricular lead placement: Any added value by post-procedural fluoroscopy versus three -dimensional echocardiography? Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2021, 19, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, G.Z.K.; Masood, A.; Ahmed, N.; et al. Permanent pacemaker implantation associated tricuspid regurgitation. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2021, 29, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; You, H.; Chen, K.; et al. Distance between the lead-implanted site and tricuspid valve annulus in patients with left bundle branch pacing: Effects on postoperative tricuspid regurgitation deterioration. Heart Rhythm. 2023, 20, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, J.J.; Mao, Y.; Zhen, Z.; et al. Close proximity of leadless pacemaker to tricuspid annulus predicts worse tricuspid regurgitation following septal implantation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2021, 14, e009530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, N.; Falconer, D.; Wyeth Nikolas Lloyd, G.; et al. Effect of tricuspid regurgitation and right ventricular dysfunction on long-term mortality in patients undergoing cardiac devices implantation: >10-year follow-up study. Int J Cardiol. 2020, 319:52-56. [CrossRef]

- Stassen J, Galloo X, Hirasawa K, et al. Tricuspid regurgitation after cardiac resynchronization therapy: evolution and prognostic significance. Europace. 2022;24(8):1291-1299. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://academic.oup.com/europace/article/24/8/1291/6555064?login=false. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.W.; Song, J.M.; Park, J.P.; Lee, J.W.; Kang, D.H.; Song, J.K. Long-term prognosis of isolated significant tricuspid regurgitation. Circ J. 2010, 74, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadreddini, M.; Haroun, M.J.; Buikema Lisanne Morillo, C.; et al. Tricuspid valve regurgitation following temporary or permanent endocardial lead insertion, and the impact of cardiac resynchronization therapy. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2014, 8, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nona, P.; Coriasso, N.; Khan, A.; et al. Pacemaker following transcatheter aortic valve replacement and tricuspid regurgitation: A single-center experience. J Card Surg. 2022, 37, 2937–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haeberlin, A.; Bartkowiak, J.; Brugger Nicolas Tanner, H.; et al. Evolution of tricuspid valve regurgitation after implantation of a leadless pacemaker: A single center experience, systematic review, and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2022, 33, 1617–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theis, C.; Huber, C.; Kaesemann, P.; et al. Implantation of leadless pacing systems in patients early after tricuspid valve surgery: A feasible option. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2020, 43, 1486–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).