1. Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) constitute a rare and heterogeneous group of neoplastic lesions that may originate from neuroendocrine cells distributed throughout the body. The gastroenteropancreatic region represents the most common site of origin. [

1,

2] The site of origin and the classification of these tumors result in distinctive behavioral and outcome characteristics. In addition to their histological features and anatomical location, tumors can be functional, triggering corresponding clinical symptoms through the secretion of a variety of biologically active compounds. Despite their relative rarity, NETs have seen a significant increase in prevalence over the past three decades. This is due to improvements in awareness and diagnostic techniques. It appears that the majority of NETs are comparatively inert in comparison to other epithelial malignant neoplasms. It is noteworthy that these tumors can be aggressive and difficult to treat. [

3,

4,

5,

6]

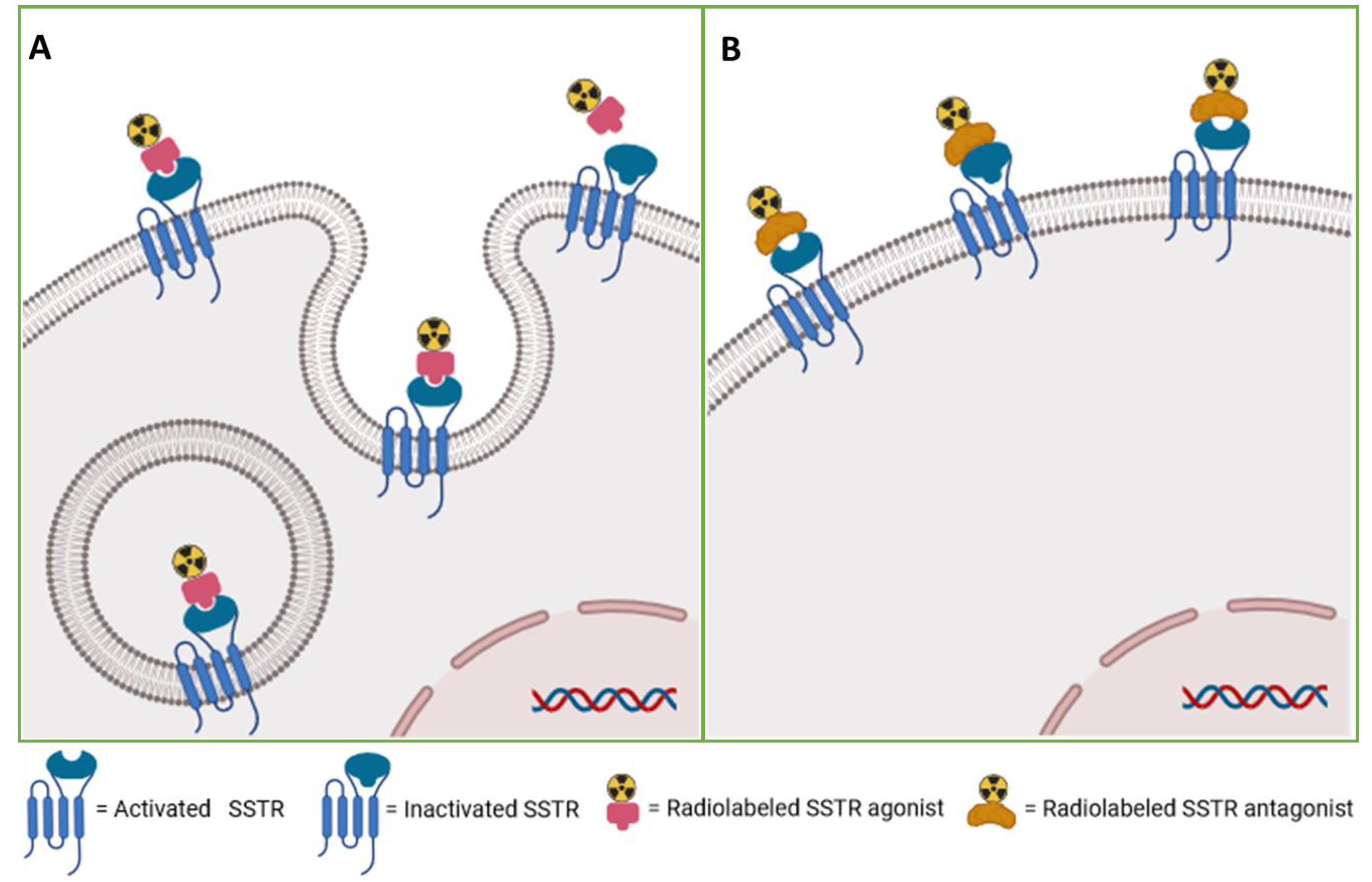

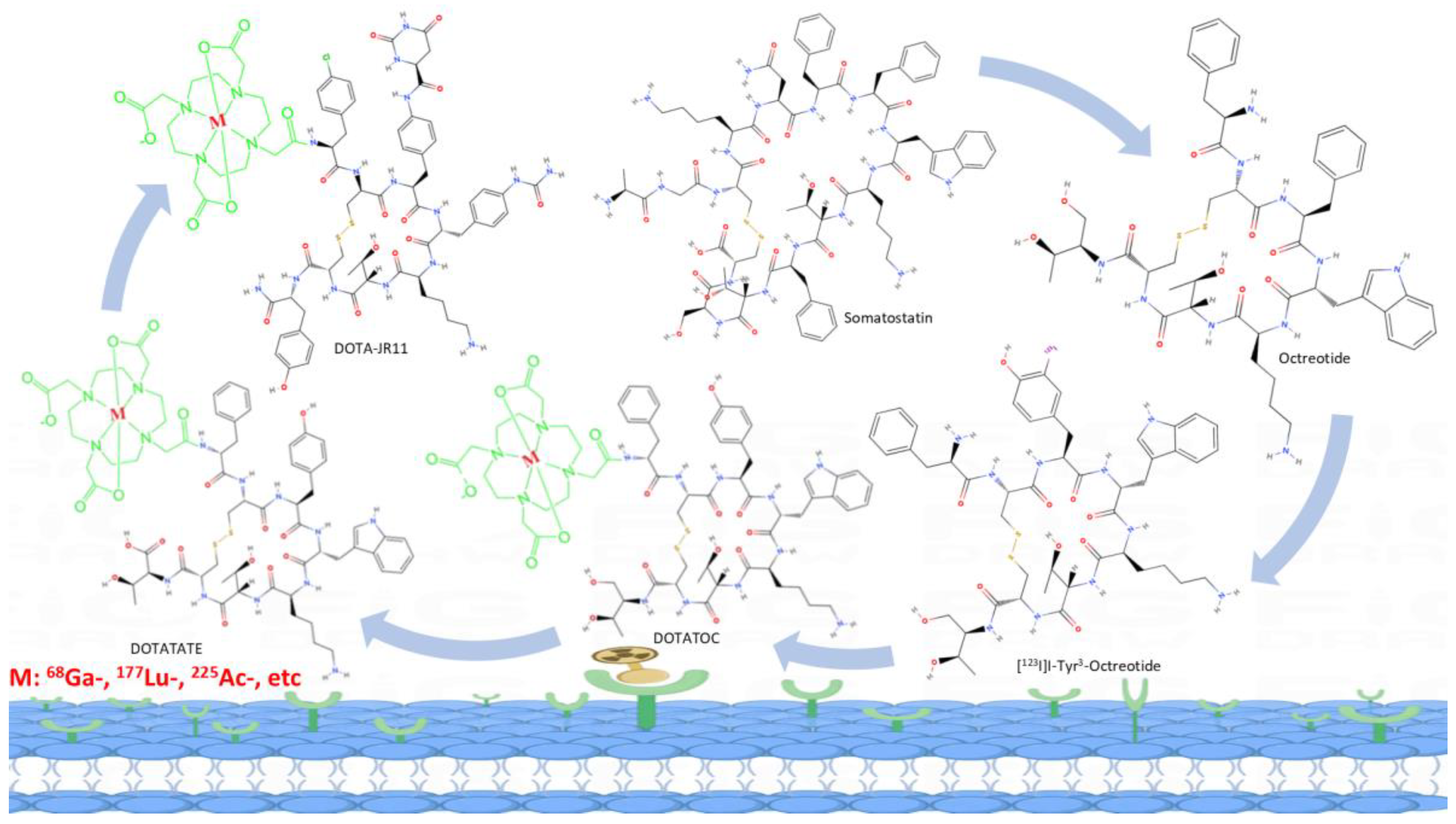

The somatostatin receptors have high expression in tumors, whereas it is not significantly expressed in the majority of physiological tissues. Some human tumors derived from neuroendocrine and gastroenteropancreatic sources have been observed to express a range of SST mRNAs. Among these, SSTR2 has been identified as the most prominently expressed, providing feasibility for the utilization of radiolabeled somatostatin receptors in therapy and diagnosis. [

7,

8] The use of somatostatin receptors agonist-based theranostic radiopharmaceuticals, such as [

90Y]Y- or [

177Lu]Lu-DOTATOC, [

177Lu]Lu-DOTATATE, as well as [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATOC and [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE, in the diagnosis and management of patients with neuroendocrine tumors have previously been extensively promoted in clinical practice and play a pivotal role in both patient outcomes and quality of life. [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] An important factor of the utilization of agonists for theranostics of neuroendocrine tumors is their excellent capacity for internalization within tumor cells. Following high-affinity binding to the receptor, agonists commonly induce the internalization of the ligand-receptor complex and facilitate the accumulation of radioactivity. [

8,

17,

18] The recent introduction of SSTR antagonists, such as [

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-JR11 [

19], has resulted in notable advancements in the field of SSTR targeting. Unlike agonists, antagonists typically do not induce internalization. Rather, they bind to both activated and inactivated conformations of SSTRs, exhibiting a slower dissociation rate than agonists. As a result, the radioactivity accumulates on the surface of tumor cells, but with greater intensity than the agonists. In addition, SSTR antagonists benefit from a longer duration of action and stability in hydrophobic environments due to their greater chemical stability and hydrophobicity. Therefore, the SSTR antagonists show superior pharmacokinetic properties and improved tumor visualization (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). [

20,

21,

22,

23]

A bibliometric study could provide researchers with a comprehensive overview of published literature. Through bibliometric analysis, we can understand the research trends and areas of interest within this field, as well as predict further development. This will be of significant value in advancing the discipline and clinical practice. [

24,

25] We used the Web of Science database to analyze the latest research on radiolabeled Somatostatin receptor agonists and antagonists in the theranostics of neuroendocrine tumors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

A comprehensive search of the Web of Science database was conducted. The following subject terms were employed in the search: (1) neuroendocrine tumors; (2) diagnosis or therapeutics or theranostics; (3) somatostatin receptor; (4) antagonists or inhibitors or agonists. The search was concluded on 30 July 2024.

The inclusion of published articles on radiolabeled somatostatin receptor agonists or antagonists for NETs was determined by two authors, who removed irrelevant literature by reading the title and abstract. In cases of doubt, a third author was invited to make a joint judgment on whether to include the article in the study. As this study did not involve human subjects, approval of the institutional review board statement was not required.

2.2. Bibliometric Analysis

The included literature has been subjected to data collection and cleaning, with information recorded including publication and citation counts, year of publication, H-index, country/region, affiliation, author, journal, reference, and author keywords. Before data analysis, a thesaurus file combined certain duplicates into a single term, fixed misspelled sections, and eliminated unnecessary words. VOSviewer 1.6.20.0 (Leiden University, The Netherlands) was used to analyze keywords and national contributions and to generate visualizations of these collaborative networks. Python 3.9.19 was used to draw line graphs and polar bar charts. VOSviewer uses the size of nodes to represent frequency and the lines between nodes to represent the total link strength. The color represents the average time of appearance in all included publications, with blue nodes corresponding to earlier appearances and yellow nodes corresponding to more recent appearances. A comprehensive examination of the clinical-type articles that compared antagonists and agonists was also conducted.

3. Results

A total of 555 articles were identified through the search strategy, and 123 documents were ultimately selected for bibliometric analysis and VOSviewer visualization based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

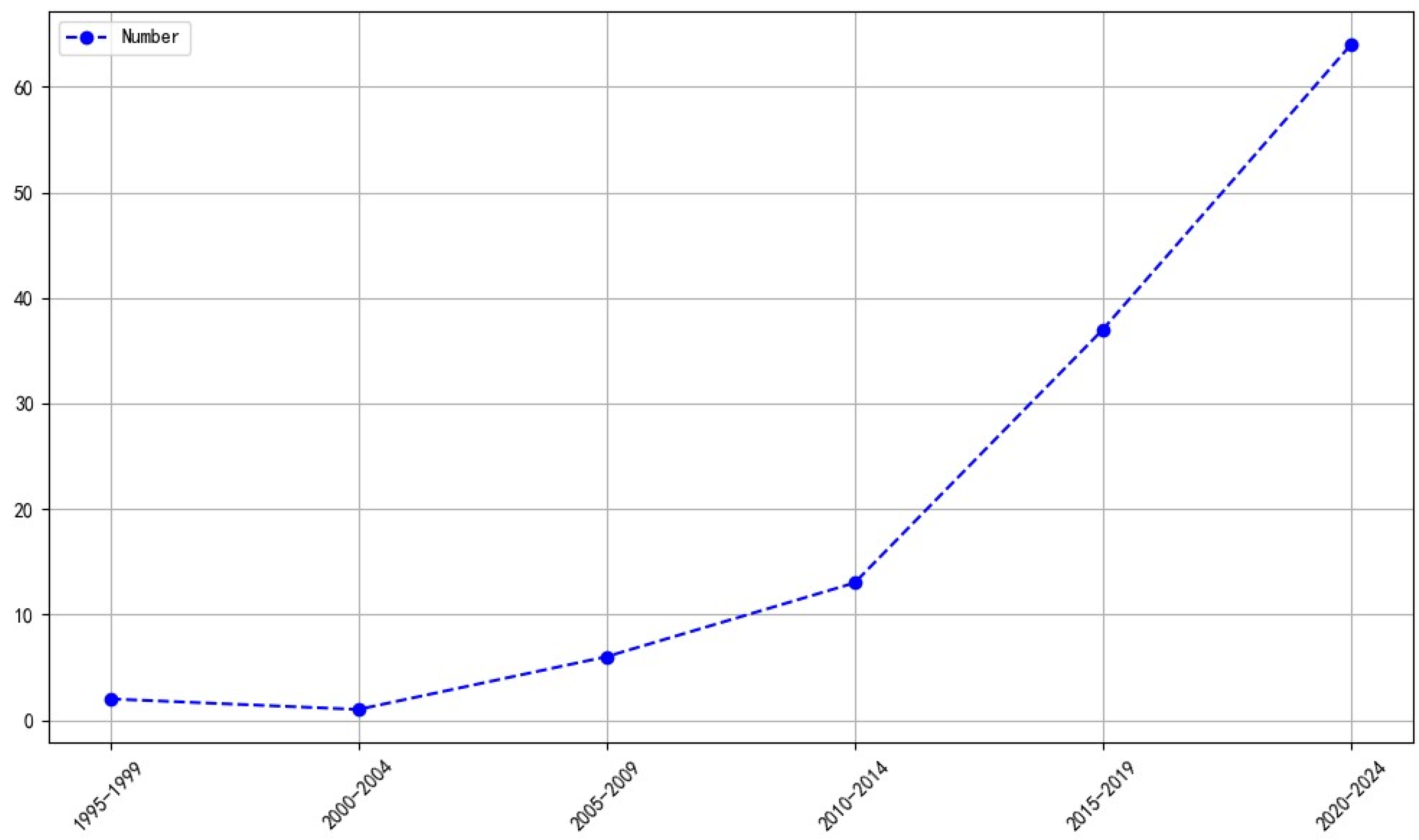

3.1. Global Trends in Publications

The number of publications on radiolabeled somatostatin receptor agonists and antagonists using a theranostic approach for neuroendocrine tumors has increased steadily and significantly since 2014 (

Figure 3).

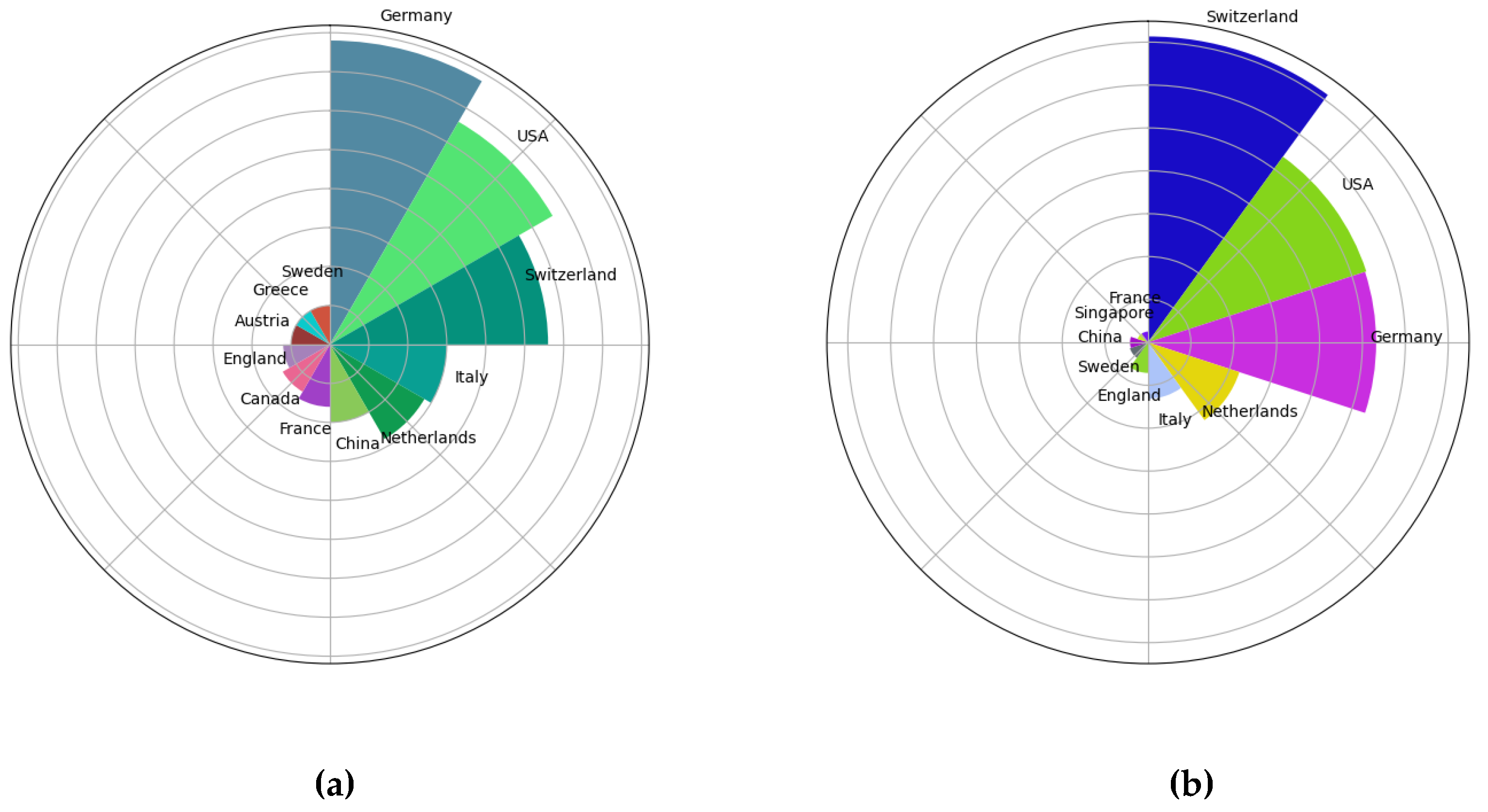

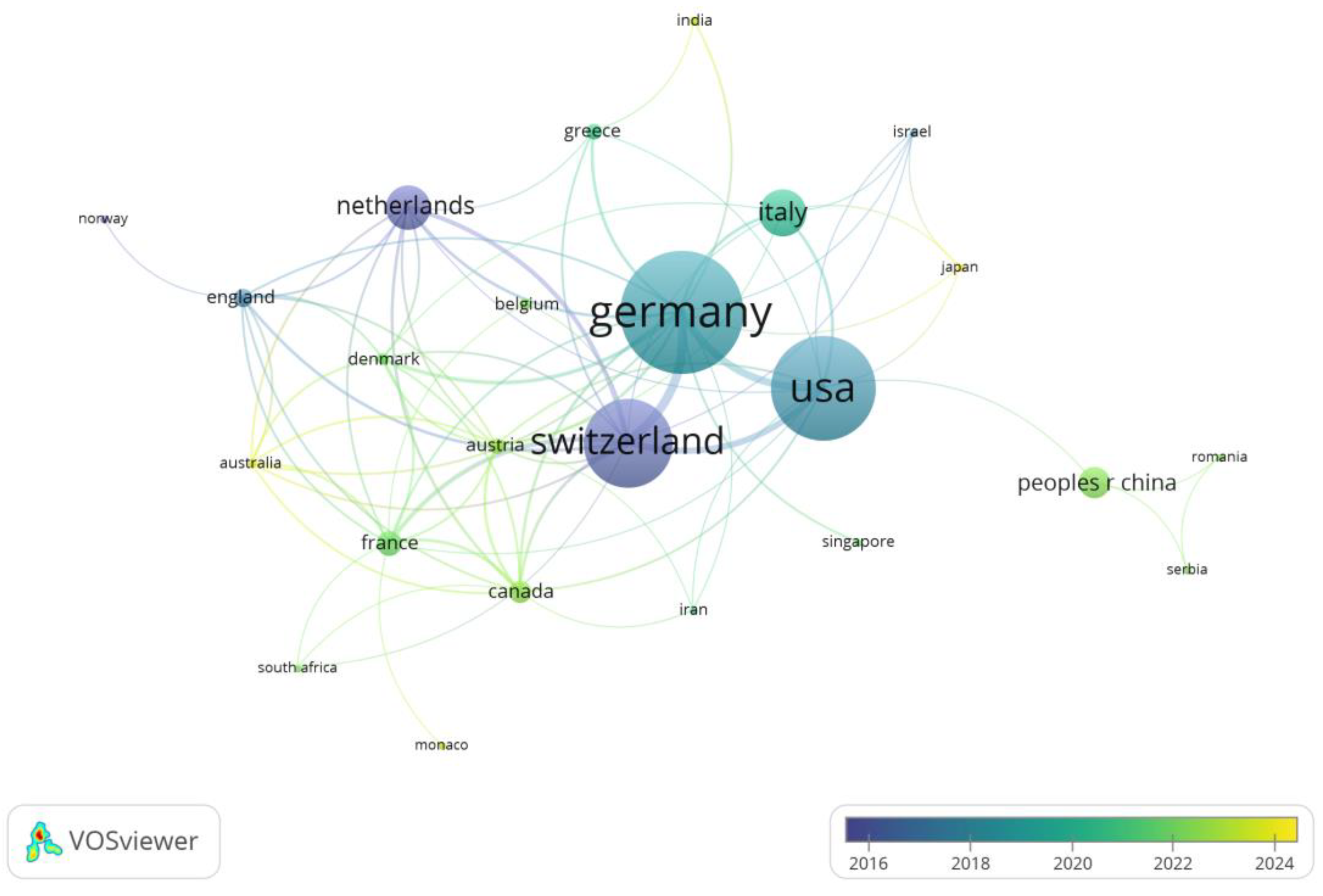

3.2. Analysis of Country Contributions

We analyzed the top 10 countries in terms of the number of publications and the top 10 countries in terms of the number of citations (

Figure 4). Germany published the most articles (39), followed by the United States (33) and Switzerland (28). Switzerland’s publications were cited 1783 times, which ranked first, followed by the United States (1338) and Germany (1330). Europe and the USA have the earliest research in this area and the highest number of publications (

Figure 5).

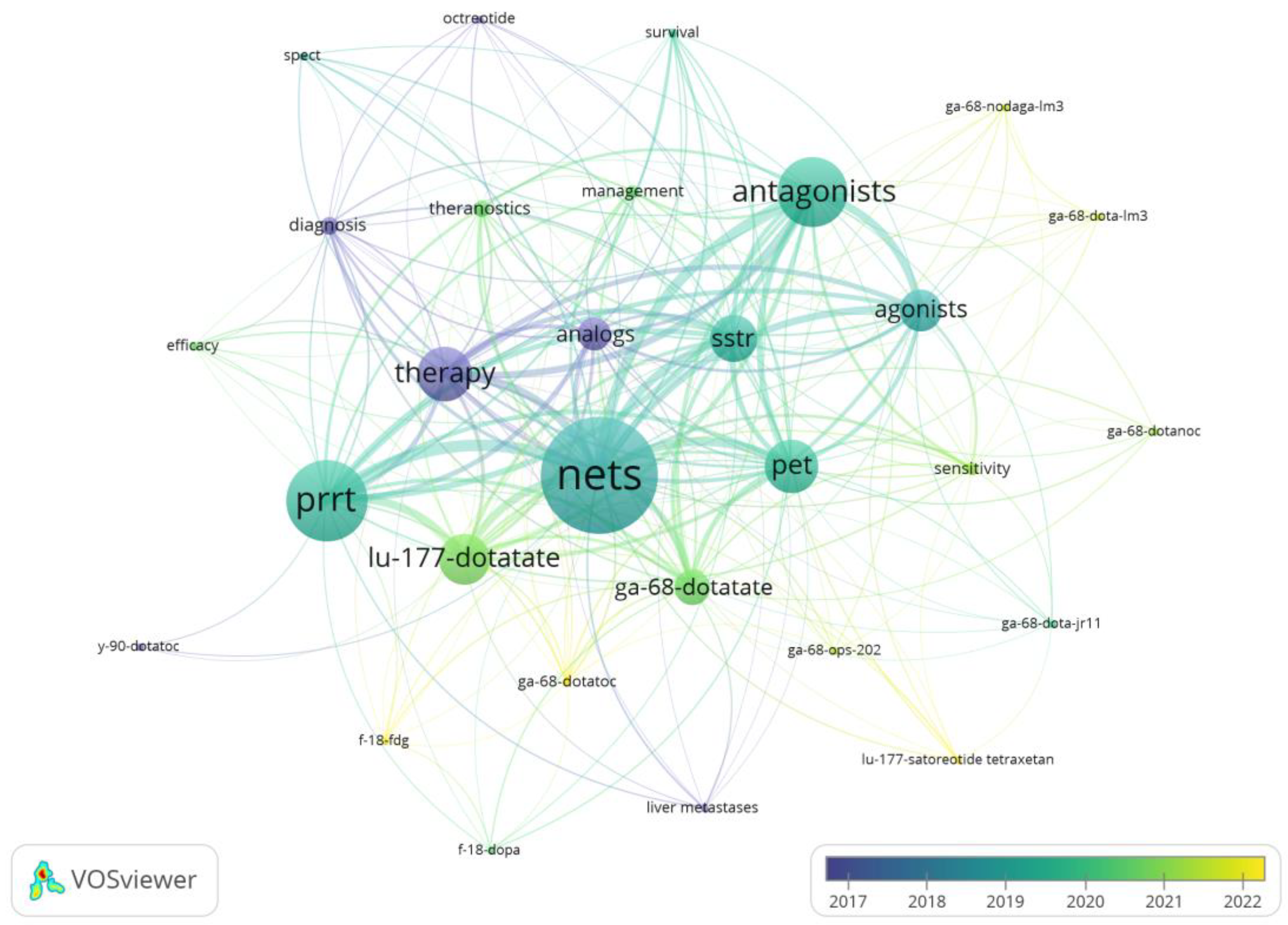

3.3. Analysis of Keywords

The distribution of keywords was analyzed using the VOSviewer. Synonym merging was conducted prior to the analysis, and the minimum number of keyword occurrences was set to two. The keyword with the highest frequency was NETs (occurrences = 89), followed by PRRT (occurrences = 62) and Antagonists (occurrences = 53). [

177Lu]Lu-DOTATATE and [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE are relatively more numerous studies, and somatostatin receptor antagonists are more recent (e.g., [

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-JR11, [

177Lu]Lu-satoreotide tetraxetan) (

Figure 6).

3.4. Analyses of Clinically Comparative Articles

3.4.1. Diagnosis of Neuroendocrine Tumors

We have summarized and analyzed clinical studies comparing antagonists and agonists to diagnose neuroendocrine tumors. Zhu, W. et al. [

26], Liu, M. et al. [

27], and Viswanathan, R. et al. [

28] have shown that antagonist uptake is less than agonist uptake in normal tissues (e.g., spleen, renal cortex/kidney, adrenal glands, pituitary gland, stomach, liver, small intestine, pancreas, etc.) (

Table 1).

In certain comparative studies of antagonist and agonist uptake in tumor tissue, antagonists have been found to be as prominent as, if not more so than, agonists. For example, Nicolas, G. P. et al. [

29] conducted a comparison between [

68Ga]Ga-OPS202([

68Ga]Ga-NODAGA-JR11, 15 μg peptide) with [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATOC (15 μg peptide), and [

68Ga]Ga-OPS202 (50 μg peptide) with [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATOC (15 μg peptide), there was no significant difference in all lesion uptake parameters (p > 0.05). However, the antagonists demonstrated superior performance compared to the agonists in terms of tumor-to-background ratio. The liver ratio, [

68Ga]Ga-OPS202 (15 μg peptide) and [

68Ga]Ga-OPS202 (50 μg peptide) were superior to [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATOC (15 μg peptide) with p-values of 0.004 and 0.008, respectively. Zhu, W. et al. [

26] presented that antagonists were significantly superior to agonists for uptake in liver lesions (p < 0.001) and antagonists were also significantly superior in tumor-to-liver ratio (p < 0.001). Also Liu, M. et al. [

30] compared four

68Ga-labelled antagonists with [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE. The comparison of the antagonists revealed no notable differences in lesion uptake parameters when compared to [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE (p = 0.772). When each of the four

68Ga-labelled antagonists was compared with [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE, [

68Ga]Ga-NODAGA-LM3 demonstrated superior performance compared to [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE (p < 0.001). However, [

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-JR11 was inferior to [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE (p = 0.001 ), [

68Ga]Ga-NODAGA-JR11 and [

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-LM3 did not exhibit a significant difference in comparison with [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE. Therefore, both the four

68Ga-labelled antagonists, when considered collectively and individually in comparison with [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE showed a notable superiority of antagonists over agonists in terms of tumor-to-liver ratio (p < 0.001).

In addition, Liu, M. et al. [

27] conducted another study demonstrating a significant advantage of [

18F]AlF-NOTA-LM3 over [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE in terms of tumor-to-liver ratio (p < 0.001). The study by Viswanathan, R. et al. [

28] comparing [

68Ga]Ga DATA

5m-LM4 with [

68Ga]Ga-DOTANOC similarly demonstrated a significant advantage of both antagonists over agonists in terms of tumor-to-liver ratio (p = 0.008) (

Table 2).

The study by Wild D. et al. [

21] compared the diagnostic efficacy of [

90In]In-DOTA-BASS and [

111In]In-DTPA-octreotide based on the total lesion level, with 25/28 lesions detected by [

111In]In-DOTA-BASS and 17/28 by [

111In]In-DTPA-octreotide. All lesions visible on [

111In]In-DTPA-octreotide scans were also seen on [

111In]In-DTPA-BASS, whereas 8 lesions on [

111In]In-DTPA-BASS were not seen on [

111In]In-DTPA-octreotide. Bone lesions were undetectable in both [

111In]In-DOTA-BASS and [

111In]In-DTPA-octreotide scans. Nicolas, G. P. et al. [

29] compared [

68Ga]Ga-OPS202 with [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATOC based on overall lesion levels and showed that both [

68Ga]Ga-OPS202 (15 μg peptide) and [

68Ga]Ga-OPS202 (50 μg peptide) had significantly better sensitivity than [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATOC (50 μg peptide). Zhu, W. et al. [

26] showed that [

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-JR11 was superior to [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE in the detection of liver lesions and [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE was superior to [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATOC in the detection of bone lesions in both patient-based and lesion-based studies. Liu, M. et al.[

30] reported that patient-level comparisons between antagonist imaging (all tracer combinations including [

68Ga]Ga-NODAGA-LM3, [

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-LM3, [

68Ga]Ga-NODAGA-JR11, and [

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-JR11) and [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE were comparable in patient-level sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy, with no statistically significant differences observed. Patient-level sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were significantly higher for [

68Ga]Ga-NODAGA-LM3 compared to [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE. The sensitivity of [

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-JR11 was poor compared to [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE. Liu, M. et al.[

27] also reported that [

18F]AlF-NOTA-LM3 was superior to [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE in the detection of liver and lymph node metastases, both on a per-patient level and on a per-lesion level. [

18F]AlF-NOTA-LM3 was the first SSTR analog to show an advantage in detecting lymph node lesions compared to [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE. Research by Viswanathan, R. et al.[

28] dedicated a significant advantage of [

68Ga]Ga-DATA

5m-LM4 over [

68Ga]Ga-DOTANOC in both liver metastases and bone metastases based on a lesion-level comparison.

3.4.2. Radiotherapeutics for Neuroendocrine Tumors

Wild, D. et al. found that [

22], [

177Lu]Lu-DOTA-JR11 and [

177Lu]Lu-DOTATATE had similar blood clearance: alpha half-life (distribution phase) 8 ± 6 minutes versus 10 ± 6 minutes and beta half-life (elimination phase) 8.8 ± 1.4 hours versus 7.8 ± 2.5 hours. The α-phase half-life shows how long it takes for the two radiopharmaceuticals to reach organs or tissues. The β-phase half-life shows how long they stay in the body. [

177Lu]Lu-DOTA-JR11 showed a longer intra-tumor residence time and a higher tumor uptake rate (residence time 1.3 to 2.8 times longer, tumor uptake rate 1.1 to 2.6 times higher) than [

177Lu]Lu-DOTATATE, resulting in a 1.7 to 10.6 times higher tumor dose. The study by Baum, R. P. et al. [

31] also found a higher uptake and longer effective half-life of [

177Lu]Lu-DOTA-LM3 in systemic, renal, splenic, and metastatic tumors compared to the agonist [

177Lu]Lu-DOTATOC. The dose of radiopharmaceuticals absorbed by organs and tumors was also compared in both studies (

Table 3).

There were no serious adverse effects in either study, but in the study by Wild, D. et al. [

22] one patient experienced transient flushing after injection of [

177Lu]Lu-DOTA-JR11, and a patient experienced grade 3 thrombocytopenia, which recovered completely within 8 weeks. In the study by Baum, R. P. et al. [

31], mild nausea without vomiting was observed in five patients, and three patients also developed grade 3 thrombocytopenia but did not show unusual and did not require platelet transfusions.

3.4.3. Paired Theranostic

Paired imaging/therapy with radiolabeled somatostatin receptor antagonists is a novel approach to neuroendocrine tumors. In a portion of a prospective clinical trial reported by Krebs, S. et al. [

32], 20 patients suffering from progressive, histologically-confirmed, unresectable NET underwent PET/CT imaging using [

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-JR11 and SPECT/CT with [

177Lu]Lu-DOTA-JR11 imaging. The results of this study on the correlation between

68Ga- and

177Lu- labeled antagonist (the same precursor DOTA-JR11), respectively, showed that both imaging revealed positive lesions in all 20 patients with metastatic NETs. The correlation between SUV and tumor-to-normal tissue ratios on PET and SPECT also demonstrated that [

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-JR11 PET/CT could be used as a tool for patient selection and then PRRT with [

177Lu]Lu-DOTA-JR11 ([

177Lu]Lu-satoreotide tetraxetan). Similar good biodistribution on [

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-JR11 PET/CT and [

177Lu]Lu-satoreotide tetraxetan SPECT/CT images with minimal or mild uptake in uninvolved livers aid in the detection of lesions. The tumor lesion SUVpeak uptake ratio of [

177Lu]Lu-satoreotide tetraxetan to [

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-JR11 was high in all patients, especially as even patients with tumor lesions with low SSTR expression may benefit from [

177Lu]Lu-satoretin tetracycline treatment.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic investigation into the utilization of somatostatin receptor agonists and antagonists in the theranostics of neuroendocrine tumors.

The results of this study demonstrated that there has been a rapid increase in the number of publications in this area, particularly following 2014, when the growth rate accelerated obviously (

Figure 3). The analysis included published articles by researchers in 29 countries. However, it should be noted that the majority of these publications originate from Europe and the United States. In terms of quantity, visibility and impact, publications from Germany, the US, and Switzerland have the greatest global impact (

Figure 4, 5). This may be attributed to two factors: Primarily, the economic base of these countries is capable of sustaining their output in research, [

33] and secondly, the development of novel radiopharmaceuticals for theranostic purposes, requires state-of-the-art facilities and an interdisciplinary team. [

34,

35] For example, Professor Helmut Maecke [

36,

37,

38] and his research group are pioneering experts in the field of radiolabeled SSTR analogs. They are renowned for their contributions to this area of research. His notable contributions to the development of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) have significantly advanced the field of PRRT. In particular, DOTATOC (DOTA-[Tyr3]-Octreotide) [

39] represents a significant innovation in neuroendocrine tumor therapy, as it has been instrumental in improving both targeting and therapeutic efficacy in tumors that express the growth inhibitory receptor. It provides a more efficacious treatment option for patients with inoperable or metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. In recent years, a number of Asian countries, including China, Singapore, Iran, Japan, and India, have become engaged in research activities within this field. Of these countries, China has made the most significant contributions (

Figure 5).

Keywords reflect the core of scientific research. Commonly used keywords focus on neuroendocrine tumors, diagnosis and treatment, and radiopharmaceuticals. Radiopharmaceuticals used for diagnosis are mainly [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE, and those used for treatment are mainly [

177Lu]Lu-DOTATATE, both of which belong to somatostatin receptor agonists (

Figure 6). Although [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATOC is the first FDA-approved

68Ga radiopharmaceutical for PET imaging, it appeared earlier than [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE. [

40] However, this study is different. The keyword VOSviewer of [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATOC has a smaller weight and appears later than [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE. This may be because the concept of somatostatin receptor antagonists for imaging/treating neuroendocrine tumors emerged later than agonists, and in the past researchers have not used agonists as keywords when discussing PRRT or diagnosis but rather analogs. Another reason is that [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE has a better affinity for human SSTR2 than [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATOC, and researchers preferred to compare it with [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATATE when interpreting antagonists. [

41,

42]. The same phenomenon was confirmed in our analysis of clinical research articles, where only one study chose [

68Ga]Ga-DOTATOC as a control group when comparing antagonists and agonists [

29]. The gradual emergence of some somatostatin receptor antagonists in recent years, such as [

68Ga]Ga-OPS202, [

68Ga]Ga-NODAGA-LM3, [

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-JR11, [

177Lu]Lu-DOTA-JR11, [

177Lu]Lu-DOTA-LM3, etc. (

Figure 6), and these radiopharmaceuticals respond to the fact that research in this field has now made some progress and has a better outlook.

Since its emergence, somatostatin receptor radioligands have received sustained attention from a wide range of scientific researchers, greatly contributing to the development of peptide radiopharmaceuticals. [

43,

44] The application of somatostatin receptor radiopharmaceuticals in clinical practice has undoubtedly improved the diagnostic and therapeutic efficacy of patients with neuroendocrine tumors, as well as the quality of life and survival rate of patients. [

45,

46] Since antagonists can bind to more tumor targets than agonists, a paradigm shift in binding from internalizing SSTR2 agonists to antagonists is feasible. [

20,

47,

48] Therefore, antagonists have a wider clinical indication. Our investigation has continued that the majority of current antagonists have good clinical performance, especially in normal tissues where uptake is significantly lower than that of agonists (

Table 1). The tumor-to-liver ratio of antagonists has an obvious advantage over agonists, which would help in the detection of liver metastases from NETs (

Table 2). In addition, the

177Lu labeled somatostatin receptor antagonists used for treatment were also superior to agonists in terms of dose absorbed by tumors, especially in liver metastases compared to agonists (

Table 3). Clinical studies of paired imaging/therapy of neuroendocrine tumors with radiolabeled somatostatin receptor antagonists are also currently underway, with a study by Krebs, S. et al. [

30] demonstrating the feasibility and efficacy of sequential imaging with radiolabeled same precursor DOTA-JR11 ([

68Ga]Ga-DOTA-JR11 and [

177Lu]Lu-DOTA-JR11) for neuroendocrine tumors.

There are several limitations to this study. First, although WoS is a very powerful and authoritative database for bibliometric analyses, there may be unavoidable omissions when retrieving relevant articles. Secondly, therapeutic diagnostics is an emerging field in medicine and as we focused only on somatostatin receptor agonists and antagonists in neuroendocrine tumors, the number of publications retrieved and ultimately included in the analysis was relatively small. However, we believe that 123 articles are sufficient to identify the current status and trends in the field. The adoption rate of keywords may vary considerably between fields, as the limitations of the search strategy may affect the time of these keywords appear in the literature, resulting in a discrepancy between public perception and academic use. Alternatively, this may reflect the fact that changes in the focus of researchers may also lead to changes in keywords, resulting in differences between public perception and academic use. Taken together, these factors explain why the frequency and time of keywords in our dataset may not be entirely consistent with those commonly expected.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed the literature in the WoS core database on the use of somatostatin receptor agonists and antagonists in the theranostics of neuroendocrine tumors. The number of relevant publications in this area is increasing, with countries such as Europe and the US contributing significantly both in terms of quantity and quality of literature. It is anticipated that somatostatin receptor antagonists will remain a prominent area of investigation in the field of neuroendocrine tumor theranostics in the future. A small number of clinical trials comparing antagonists and agonists have already appeared, and antagonists have shown exciting results in both diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. When employed for diagnostic purposes, antagonists demonstrate a lower uptake than agonists in normal (non-target) tissues and exhibit a higher tumor-to-liver ratio than agonists. This would be advantageous for neuroendocrine diagnosis, particularly the detection of liver metastases.

In the context of therapeutic applications, it was observed that the radiation dose of antagonists to tumor tissue was higher than that of agonists, particularly in cases of liver metastases. Furthermore, the feasibility of an antagonists-paired PET/SPECT imaging has been demonstrated, which may aid patient selection and therapy management.

These results demonstrate considerable potential for antagonists in the domain of neuroendocrine theranostics. However, the current number of studies is relatively limited, though it is increasing. Further research will be required to more comprehensively compare the effects of antagonists with those of agonists in the diagnosis and treatment of neuroendocrine tumors, as well as to conduct additional imaging therapy-matching studies with antagonists.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, QW, DL, and BHY; methodology, QW, DL; software, QW, AHS, DL; validation, QW, DL, and BHY; formal analysis, QW; investigation, QW, SB, AE; AHS resources, QW, ML, FE, DL, and BHY; data curation, QW, DL, and BHY; writing original draft preparation, QW; writing review and editing, QW, FE, ML, DL, and BHY; visualization, QW, DL, and BHY; supervision, DL, and BHY; project administration, QW, DL, and BHY; funding acquisition, QW, ML, DL, and BHY. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Qi Wang has received a scholarship from China Scholarship Council (CSC No.202208140021). The research is supported by the Department of Nuclear Medicine, School of Medicine, Philipps University Marburg.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fortunati, E.; Bonazzi, N.; Zanoni, L.; Fanti, S.; Ambrosini, V. Molecular imaging Theranostics of Neuroendocrine Tumors. Seminars in nuclear medicine 2023, 53, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; Barnett, E.; Rodger, E.J.; Chatterjee, A. Subramaniam RM: Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Genetics and Epigenetics. PET clinics 2023, 18, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.C.; Hassan, M.; Phan, A.; Dagohoy, C.; Leary, C.; Mares, J.E.; Abdalla, E.K.; Fleming, J.B.; Vauthey, J.N.; Rashid, A.; et al. One hundred years after "carcinoid": epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2008, 26, 3063–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modlin, I.M.; Oberg, K.; Chung, D.C.; Jensen, R.T.; de Herder, W.W.; Thakker, R.V.; Caplin, M.; Delle Fave, G.; Kaltsas, G.A.; Krenning, E.P.; et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. The Lancet Oncology 2008, 9, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope, T.A.; Pavel, M.; Bergsland, E.K. Neuroendocrine Tumors and Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy: When Is the Right Time? Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2022, 40, 2818–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosini, V.; Kunikowska, J.; Baudin, E.; Bodei, L.; Bouvier, C.; Capdevila, J.; Cremonesi, M.; de Herder, W.W.; Dromain, C.; Falconi, M.; et al. Consensus on molecular imaging and theranostics in neuroendocrine neoplasms. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2021, 146, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benali, N.; Ferjoux, G.; Puente, E.; Buscail, L.; Susini, C. Somatostatin receptors. Digestion 2000, 62 Suppl 1, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reubi, J.C. Peptide receptors as molecular targets for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Endocrine reviews 2003, 24, 389–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, M.H.; Tameez Ud Din, A.; Khan, A.H. Neuroendocrine Tumor Therapy with Lutetium-177: A Literature Review. Cureus 2019, 11, e3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccauro, M.; Follacchio, G.A.; Spreafico, C.; Coppa, J.; Seregni, E. Safety and Efficacy of Combined Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy and Liver Selective Internal Radiation Therapy in a Patient With Metastatic Neuroendocrine Tumor. Clinical nuclear medicine 2019, 44, e286–e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, M.; Mücke, M.; Fischer, F.; Essler, M.; Cuhls, H.; Radbruch, L.; Ghaei, S.; Conrad, R.; Ahmadzadehfar, H. Quality of life in patients with midgut NET following peptide receptor radionuclide therapy. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging 2019, 46, 2252–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, C.; Buxbaum, S.; Rodrigues, M.; Nilica, B.; Scarpa, L.; Holzner, B.; Virgolini, I.; Gamper, E.M. Quality of Life in Patients with Metastatic Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors Receiving Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy: Information from a Monitoring Program in Clinical Routine. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2018, 59, 1566–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maecke, H.R.; Hofmann, M.; Haberkorn, U. (68)Ga-labeled peptides in tumor imaging. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2005, 46 Suppl 1, 172s–178s. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ambrosini, V.; Fani, M.; Fanti, S.; Forrer, F.; Maecke, H.R. Radiopeptide imaging and therapy in Europe. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2011, 52 Suppl 2, 42s–55s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellis, C.; Jacene, H.A. Neuroendocrine Tumors: Diagnostics. PET clinics 2024, 19, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marincek, N.; Jörg, A.C.; Brunner, P.; Schindler, C.; Koller, M.T.; Rochlitz, C.; Müller-Brand, J.; Maecke, H.R.; Briel, M.; Walter, M.A. Somatostatin-based radiotherapy with [90Y-DOTA]-TOC in neuroendocrine tumors: long-term outcome of a phase I dose escalation study. Journal of translational medicine 2013, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cescato, R.; Schulz, S.; Waser, B.; Eltschinger, V.; Rivier, J.E.; Wester, H.J.; Culler, M.; Ginj, M.; Liu, Q.; Schonbrunn, A.; et al. Internalization of sst2, sst3, and sst5 receptors: effects of somatostatin agonists and antagonists. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2006, 47, 502–511. [Google Scholar]

- Weckbecker, G.; Lewis, I.; Albert, R.; Schmid, H.A.; Hoyer, D.; Bruns, C. Opportunities in somatostatin research: biological, chemical and therapeutic aspects. Nature reviews Drug discovery 2003, 2, 999–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K. (68)Ga-1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid-Cpa-cyclo(d-Cys-amino-Phe-hydroorotic acid-D-4-amino-Phe(carbamoyl)-Lys-Thr-Cys)-D-Tyr-NH(2) (JR11). In Molecular Imaging and Contrast Agent Database (MICAD); edn.; National Center for Biotechnology Information (US): Bethesda (MD), 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ginj, M.; Zhang, H.; Waser, B.; Cescato, R.; Wild, D.; Wang, X.; Erchegyi, J.; Rivier, J.; Mäcke, H.R.; Reubi, J.C. Radiolabeled somatostatin receptor antagonists are preferable to agonists for in vivo peptide receptor targeting of tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2006, 103, 16436–16441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.; Fani, M.; Behe, M.; Brink, I.; Rivier, J.E.; Reubi, J.C.; Maecke, H.R.; Weber, W.A. First clinical evidence that imaging with somatostatin receptor antagonists is feasible. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2011, 52, 1412–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, D.; Fani, M.; Fischer, R.; Del Pozzo, L.; Kaul, F.; Krebs, S.; Fischer, R.; Rivier, J.E.; Reubi, J.C.; Maecke, H.R.; et al. Comparison of somatostatin receptor agonist and antagonist for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy: a pilot study. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2014, 55, 1248–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imperiale, A.; Jha, A.; Meuter, L.; Nicolas, G.P.; Taïeb, D.; Pacak, K. The Emergence of Somatostatin Antagonist-Based Theranostics: Paving the Road Toward Another Success? Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2023, 64, 682–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninkov, A.; Frank, J.R.; Maggio, L.A. Bibliometrics: Methods for studying academic publishing. Perspectives on medical education 2022, 11, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foy, J.P.; Serresse, L.; Decavèle, M.; Allaire, M.; Nathan, N.; Renaud, M.C.; Sabourdin, N.; Souala-Chalet, Y.; Tamzali, Y.; Taytard, J.; et al. Clues for improvement of research in objective structured clinical examination. Medical education online 2024, 29, 2370617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Yao, S.; Bai, C.; Zhao, H.; Jia, R.; Xu, J.; Huo, L. Head-to-Head Comparison of (68)Ga-DOTA-JR11 and (68)Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT in Patients with Metastatic, Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Prospective Study. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2020, 61, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Ren, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Jia, R.; Cheng, Y.; Bai, C.; Xu, Q.; Zhu, W.; et al. Evaluation of the safety, biodistribution, dosimetry of [(18)F]AlF-NOTA-LM3 and head-to-head comparison with [(68)Ga]Ga-DOTATATE in patients with well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors: an interim analysis of a prospective trial. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan, R.; Ballal, S.; Yadav, M.P.; Roesch, F.; Sheokand, P.; Satapathy, S.; Tripathi, M.; Agarwal, S.; Moon, E.S.; Bal, C. Head-to-Head Comparison of SSTR Antagonist [(68)Ga]Ga-DATA(5m)-LM4 with SSTR Agonist [(68)Ga]Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT in Patients with Well Differentiated Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Prospective Imaging Study. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas, G.P.; Schreiter, N.; Kaul, F.; Uiters, J.; Bouterfa, H.; Kaufmann, J.; Erlanger, T.E.; Cathomas, R.; Christ, E.; Fani, M.; et al. Sensitivity Comparison of (68)Ga-OPS202 and (68)Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT in Patients with Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Prospective Phase II Imaging Study. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2018, 59, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Cheng, Y.; Bai, C.; Zhao, H.; Jia, R.; Chen, J.; Zhu, W.; Huo, L. Gallium-68 labeled somatostatin receptor antagonist PET/CT in over 500 patients with neuroendocrine neoplasms: experience from a single center in China. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging 2024, 51, 2002–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, R.P.; Zhang, J.; Schuchardt, C.; Müller, D.; Mäcke, H. First-in-Humans Study of the SSTR Antagonist (177)Lu-DOTA-LM3 for Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy in Patients with Metastatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Dosimetry, Safety, and Efficacy. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2021, 62, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, S.; O'Donoghue, J.A.; Biegel, E.; Beattie, B.J.; Reidy, D.; Lyashchenko, S.K.; Lewis, J.S.; Bodei, L.; Weber, W.A.; Pandit-Taskar, N. Comparison of (68)Ga-DOTA-JR11 PET/CT with dosimetric (177)Lu-satoreotide tetraxetan ((177)Lu-DOTA-JR11) SPECT/CT in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors undergoing peptide receptor radionuclide therapy. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging 2020, 47, 3047–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, J.J.H. Impact of scientific, economic, geopolitical, and cultural factors on international research collaboration. Journal of Informetrics 2021, 15, 101194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, H.H.; Nicklas, B.J.; Nader, M.A.; Trost, L.M.; Miller, D.P. Creating effective academic research teams: Two tools borrowed from business practice. Journal of clinical and translational science 2020, 5, e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, L.M.; Gadlin, H. Collaboration and team science: from theory to practice. Journal of investigative medicine : the official publication of the American Federation for Clinical Research 2012, 60, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, A.; Herrmann, R.; Heppeler, A.; Behe, M.; Jermann, E.; Powell, P.; Maecke, H.R.; Muller, J. Yttrium-90 DOTATOC: first clinical results. European journal of nuclear medicine 1999, 26, 1439–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrer, F.; Uusijärvi, H.; Waldherr, C.; Cremonesi, M.; Bernhardt, P.; Mueller-Brand, J.; Maecke, H.R. A comparison of (111)In-DOTATOC and (111)In-DOTATATE: biodistribution and dosimetry in the same patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumours. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging 2004, 31, 1257–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrer, F.; Uusijärvi, H.; Storch, D.; Maecke, H.R.; Mueller-Brand, J. Treatment with 177Lu-DOTATOC of patients with relapse of neuroendocrine tumors after treatment with 90Y-DOTATOC. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2005, 46, 1310–1316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Otte, A.; Jermann, E.; Behe, M.; Goetze, M.; Bucher, H.C.; Roser, H.W.; Heppeler, A.; Mueller-Brand, J.; Maecke, H.R. DOTATOC: a powerful new tool for receptor-mediated radionuclide therapy. European journal of nuclear medicine 1997, 24, 792–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennrich, U.; Benešová, M. [(68)Ga]Ga-DOTA-TOC: The First FDA-Approved (68)Ga-Radiopharmaceutical for PET Imaging. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Öberg, K.; Sundin, A. Imaging of Neuroendocrine Tumors. Frontiers of hormone research 2016, 45, 142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Pouget, J.P.; Navarro-Teulon, I.; Bardiès, M.; Chouin, N.; Cartron, G.; Pèlegrin, A.; Azria, D. Clinical radioimmunotherapy--the role of radiobiology. Nature reviews Clinical oncology 2011, 8, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulou, M.; Stalla, G.K. Somatostatin receptors: from signaling to clinical practice. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology 2013, 34, 228–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Parihar, A.S.; Bodei, L.; Hope, T.A.; Mallak, N.; Millo, C.; Prasad, K.; Wilson, D.; Zukotynski, K.; Mittra, E. Somatostatin Receptor Imaging and Theranostics: Current Practice and Future Prospects. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2021, 62, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikhbahaei, S.; Sadaghiani, M.S.; Rowe, S.P.; Solnes, L.B. Neuroendocrine Tumor Theranostics: An Update and Emerging Applications in Clinical Practice. AJR American journal of roentgenology 2021, 217, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salih, S.; Alkatheeri, A.; Alomaim, W.; Elliyanti, A. Radiopharmaceutical Treatments for Cancer Therapy, Radionuclides Characteristics, Applications, and Challenges. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodei, L.; Weber, W.A. Somatostatin Receptor Imaging of Neuroendocrine Tumors: From Agonists to Antagonists. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2018, 59, 907–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fani, M.; Braun, F.; Waser, B.; Beetschen, K.; Cescato, R.; Erchegyi, J.; Rivier, J.E.; Weber, W.A.; Maecke, H.R.; Reubi, J.C. Unexpected sensitivity of sst2 antagonists to N-terminal radiometal modifications. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2012, 53, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).