1. Introduction

The role of software has already reached a critical point where a widespread issue could have serious consequences for society [

1]. This emphasizes the need for a robust system for error handling. The consequences of software defects can range from trivial to life-threatening, as the applications of software range from entertainment to medical purposes. The Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence (AI) massively contribute to this software dependency [

2], as more devices are running software and more devices are running more complex software. The responsibility of developers increases as some use cases like autonomous vehicles and medicine require much more extensive testing [

3]. Even though a software defect can be a mere inconvenience in some cases, even those cases would benefit from software defect prediction (SDP) [

4]. The key contribution of SDP in the software development is in the testing phase. The goal is to prioritize modules that are prone to errors. Such insights into the state of the project can allow developers to discover errors sooner or even prepare for them in certain environments.

The process of producing software is called the software development life-cycle (SDLC) during which SDP should be applied to minimize the number of errors. Software is almost never perfect and it has become common practice for developers to release unfinished projects and work on them iteratively through updates. With the use of code writing conventions and other principles, errors can be minimized, but never fully rooted out. Therefore, a robust system that would assist developers in finding errors is required. With a system like such, the errors could be found earlier which could prevent substantial financial losses. To measure the quality of the code defect density is calculated. The most common form of such measurement is the number of defects per thousand lines of code (KLOC).

The advancements in AI technologies, specifically machine learning (ML) show great potential for various NLP applications [

5]. Considering that the code is a language as well, this potential should be explored for predictions regarding programming languages as well. When natural and programming languages are compared various similarities can be observed, but the programming languages are more strict in terms of writing rules which aids pattern recognition. The quality control process can be improved through AI use which can simplify the error detection process and ensure better test coverage. To detect the errors in text it is necessary to understand what techniques are applied through NLP to achieve this. Tokenization is one of the key concepts and its role is to segment text into smaller units for processing. Stemming reduces words to their basic forms, while lemmatization identifies the root of the word through dictionaries and morphological analysis. Different parts of sentences such as nouns, verbs, and adjectives are identified through the parsing process. The potential of NLP for the SDP problem is unexplored and a literature gap is observed.

However, the use of these techniques does not come without a cost. Most sophisticated ML algorithms have extensive parameters that directly affect their performance. The process of finding the best subset of these parameters is called hyperparameter optimization. The perfect solution in most cases cannot be achieved in a realistic amount of time, which is why the goal of the optimization is to find a sub-optimal solution that is very close to the best solution. However, a model with hyperparameters optimized for one use case does not yield the same performance for other use cases. This is the problem that is described by the no free lunch (NFL) theorem [

6] that states that no solution provides equally high performance across all use cases. This work builds upon preceding research [

7] to provide a more in depth comparison between optimizers, as well as explore the potential of NLP to boost error detection in software source code.

A proposal for a two layer framework that combines CNN and ML classifiers for software defect detection.

An introduction of a NLP based approach in combination with ML classifiers for software defect detection.

A introduction of a modified optimization algorithm that builds upon the admirable performance of the original PSO.

The application of explainable AI techniques to the best performing model in order to determine the features importance on model decisions

The described research is presented in the following manner:

Section 2 gives fundamentals of the applied techniques,

Section 3 describes the main method used in this research,

Section 4 provides the settings of the performed experiments along necessary information for experiment reproduction,

Section 5 follows with the results of experiments, and

Section 6 provides the final thoughts on performed experiments along possibilities for future research.

2. Related works

Software defects, otherwise known as bugs, are software errors that result in incorrect and unexpected behavior. Various scenarios produce errors but most come from design flaws, unexpected component interaction, and coding. Such errors affect performance, but in some cases, the security of the system can be compromised as well. Through the use of statistical methods, historical data analysis, and ML such cases can be predicted and reduced.

The use of ensemble learning for SDP was explored by Ali et al. [

8]. The authors presented a framework that trains random forest, support vector machine (SVM), and naive Bayes individually, which are later combined into an ensemble technique through the soft voting method. The proposed method obtained one of the highest results while maintaining solid stability. On the other hand, Khleel et al. [

9] explore the potential of a bidirectional long short-term model for the same problem. The technique was tested with random and synthetic minority oversampling techniques. While high performance was exhibited in both experiments, the authors conclude that the random oversampling was better due to the class imbalances for the SDP problem. Lastly, Zhang et al. [

10] propose a framework based on a deep Q-learning network (DQN) with the goal of removing irrelevant features. The authors performed thorough testing of several techniques with and without DQN, and the research utilized a total of 22 SDP datasets.

The application of NLP techniques in ML is broad and Jim et al. [

5] provide a detailed overview of ML techniques that are suitable for such use cases. The use cases reported include fields from healthcare to entertainment. The paper also provides depth into the nature of computational techniques used in NLP. Different approaches include image-text, audio-visual, audio-image-text, labeling, document level, sentence level, phrase level, and word level approaches to sentiment analysis. Furthermore, the authors surveyed a list of datasets for this use case. Briciu et al. [

11] propose a model based on bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) NLP technique for SDP. The authors compared RoBERTa and CodeBERT-MLM language models for the capture of semantics and context while a neural network was used as a classifier. Finally, Dash et al. [

12] performed an NLP-based review for sustainable marketing. The authors performed text-mining through keywords and string selection, while the semantic analysis was performed through the use of term frequency-inverse document frequency.

The use of metaheuristics as optimizers has proven to yield substantial performance increases when combined with various AI techniques [

13]. Jain et al. [

14] proposed a hybrid ensemble learning technique optimized by an algorithm from the swarm intelligence subgroup of ML algorithms. Some notable examples of metaheuristic optimizers include the well established variable neighborhood search (VNS) [

15], artificial bee colony (ABC) [

16] and bat algorithm (BA) [

17]. Some recent additions also include COLSHADE [

18] and the recently introduced sinh cosh optimizer (SCHO) [

19]. Optimizers have shown promising outcomes applied in several field including timeseries forecasting [

20], healthcare [

21] and anomaly detection in medical timeseries data [

22]. Applying hybrid optimizers to parameter tuning has demonstrated decent outcomes in preceding works as well [

23,

24,

25].

The SDP problem is considered to have nondeterministic polynomial time hardness (NP-hard), as the problem cannot be solved by manual search in a realistic amount of time. Hence the optimizers are to be applied such as swarm intelligence algorithms. However, the process is not as simple since for every use case a custom set of AI techniques has to be applied due to the NFL theorem [

6]. Furthermore, the problem of hyperparameter optimization which is required to yield the most out of the performance of AI techniques is considered NP-hard as well. The application of NLP techniques for SDP is limited in literature, indicating a research gap that this work aims to bridge.

2.1. Text Mining Techniques

Introduced in 2018 [

26], the BERT technique is based on the mechanism of attention which is used to determine the meaning of a text or sentence. The technique was developed by a Google research team and since it has been applied for diverse NLP purposes [

27]. The BERT method can be modified for special use cases like text summarization and meaning inference. The attention mechanism allows for the transformers, which are the basis of BERT, to shift focus between the segments of the input. With the use of this technique, the understanding of the sentence is improved, due to the meaning of words it provides. This process can be applied in parallel over multiple parts of sentences increasing the speed of data processing and overall efficiency. Furthermore, the natural language is processed bidirectionally as stated in the name of the technique. The benefit of such a mechanism is the context of the word, as it analyzes the words that come before the analyzed word, as well as those that come after it.

The masked language model (MLM) is used for the training of BERT. The goal of such training is to determine a hidden word only from its context. This results in the model learning the structure of the language and its patterns. Training with large datasets can prepare BERT models for specialized tasks due to their transfer learning functionality. The application of BERT in software detection is not explored. The BERT has proven a reliable and efficient technique across many different NLP use cases where there are many more factors to account for than with programming languages. The latter are more strict in their rules of writing and are more prone to repeating patterns which reduces the complexity of the text analysis. A promising text mining technique with roots in statistical text analysis is term frequency inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) . As the name implies it is comprised of two components. Term frequency is determined as the ration between a term occurring in a document versus the total number of terms in said document. Mathematically it can be determined as Eq

1:

The second term in TF-IDF defines the inverse document frequency. The role of this factor is to emphasize important works, while decreasing the importance of filler and stop words that comprise the grammatical structure of a language. It can be determined as per Eq

2:

Combining TF and IDF (TF-IDF) calculates the importance of terms within a document in relation to the entire corpus as per Eq.

3.

2.2. CNN

The CNNs are recognized in the deep learning field for their high performance and versatility [

28,

29]. The multi-layered visual cortex of the animal brain served as the main inspiration for this technique. The information is moved between the layers where the input of the next layer is the output of the previous layer. The information gets filtered and processed in this manner. The complexity of the data is decreased through each layer while the ability of the model to detect finer details increases. The architecture of the CNN model consists of the convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers. Filters that are most commonly used are 3×3, 5×5, and 7×7.

To achieve the highest performance CNNs require hyperparameter optimization. The most commonly tuned parameters based on their impact on performance are the number of kernels and kernel size, learning rate, batch size, the amount of each type of layer used, weight regularization, activation function, and dropout rate. s, the activation function, the dropout rate, and so on are some examples of hyperparameters. This process is considered NP-hard, however, the metaheuristic methods have proven to yield results when applied as optimizers for CNN hyperparameter tuning [

14].

The convolutional function provides the input vector described in Equation (

4).

where the output of the

k-th feature at position

and layer

l is given as

, the input at

is

x, the display filters are given as

w, and the bias is shown as

b.

The activation function follows the convolution function shown in Equation (

5).

where non-linear function exploiting the output is given as

.

After the activation function, the pooling layers process the input toward resolution reduction. Different pooling functions can be used, and some of the most popular ones are average and max pooling. This behavior is described in Equation (

6).

where the

y represents the result of pooling.

Finally, the classification is performed by the fully connected layers. The most common applications of these layers include the softmax layers for multi-class datasets, and the sigmoid function is applied for binary classification along gradient descent methods.

The weights and biases are adjusted in each iteration which is in the case of the CNN called epochs during which the goal is to minimize the loss function provided by Equation (

7).

where the discrete variable

x has two distributions defined over it,

p and

q.

2.3. AdaBoost

During the previous decade, ML has constantly grown as a field. As a result, a large number of algorithms have been produced due to their disproportionate contributions based on the area of application. Adaptive boosting (AdaBoost) aims to overcome this through the application of weaker algorithms as a group. The algorithm was developed by Freund and Schapire in 1995 [

30]. Algorithms that are considered weak perform classification slightly better than random guessing. The AdaBoost technique applies more weak classifiers through each iteration and balances the classifier’s weight which is derived from accuracy. For errors in classification, the weights are decreased, while increases in weights are performed for good classifications.

The error of a weak classifier is calculated according to Equation

8.

where the error weight in the

t-th iteration is given as

, the number of training samples is given as

N, and the weight of

i-th training sample during the

t-th iteration

. The

represents the predicted label, and

shows the true label. The function

provides 0 for false cases, and 1 for true cases.

After the weights have been established, the modification process for weights begins for new classifiers. To achieve accurate classification large groups of classifiers should be used. The combination of sub-models and their results represents a linear model. The weight are calculated in the ensemble as per Equation (

9).

where the

changes for each weak learner and represents its weight in the final model. The weights are updated according to the Equation (

10).

where

marks the true mark of the

i-th instance,

represents the prediction result of the weak student

i-th instance in the

t-th round, and

denotes the weight,

i-th instance in the

t-th round.

The advantages of AdaBoost are that it reduces bias through learning from previous iterations, while the ensemble technique reduces variance and prevents overfitting. Therefore, the AdaBoost can provide robust prediction models. However, AdaBoost is sensitive to noisy data and exceptions.

2.4. XGBoost

The XGBoost method is recognized as a high-performing algorithm [

31]. However, the highest performance is achieved only through hyperparameter tuning. The foundation of the algorithm is ensemble learning which exploits many weaker models. Optimization with regularization along gradient boosting significantly boosts performance. The motivation behind the technique is to manage complex input-target relationships through previously observed patterns.

The objective function of the XGBoost that combines the loss function and the regularization term is provided in Equation (

11.

where the

shows the hyperparameter set,

provides loss function, while the

shows the regularization term used for model complexity management.

Mean square error (MSE) is used for utilization of the loss function given in Equation (

12).

where the

provides the value predicted for the target for each iteration

i, and the

provides the predicted value.

The process of differentiating actual and predicted values is given in Equation (

13).

4. Experimental Setup

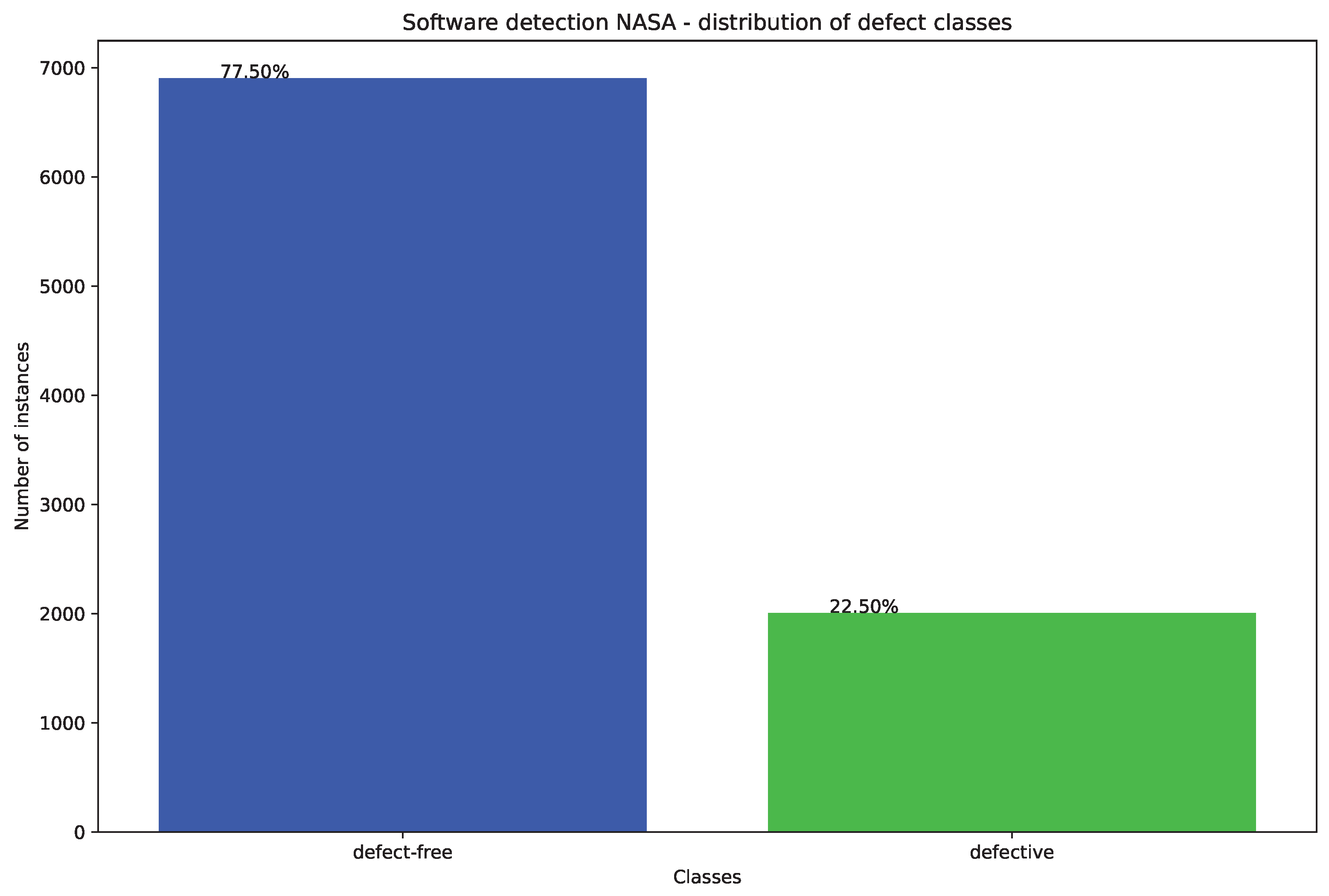

In this work two separate simulations are carried out. The first set of simulations is conducted using the a group of 5 datasets which are KC1, JM1, CM1, KC2, and PC1. These datasets are part of NASA’s promise repository aimed at SDP. The instances in datasets represent various software models and the features depict the quality of that code. McCabe [

36] and Halstead [

37] metrics were applied through 22 features. The McCabe approach was applied to its methodology that emphasizes less complex code through the reduction of pathways, while Halstead uses counting techniques as the logic behind it was that the larger the code the more it is error-prone. A tow layer approach is applied to these simulations. The class balance in the utilized dataset is provided in

Figure 3. The first utilized dataset is dis balanced with 22.5% of samples representing software with errors and 77.5% without.

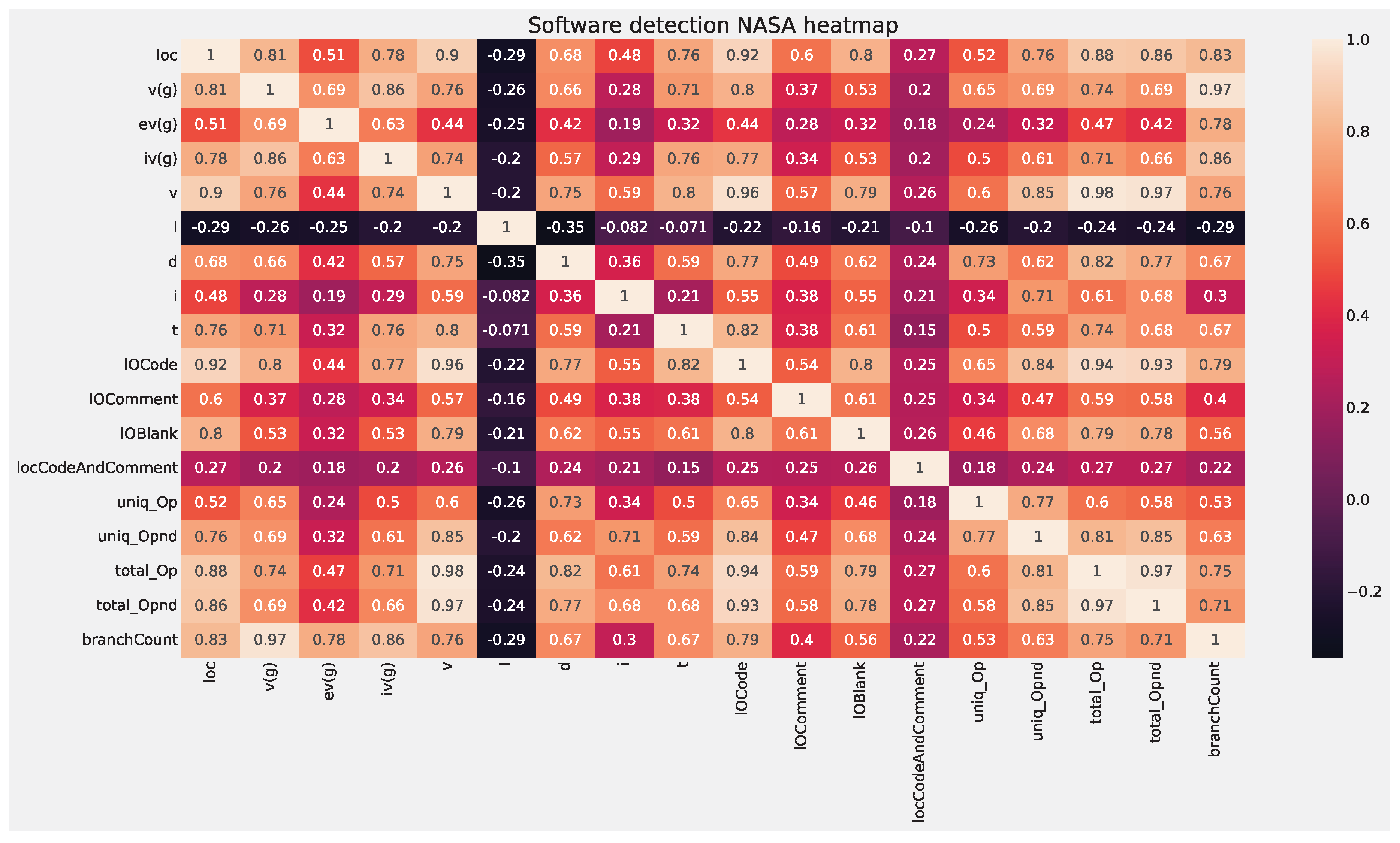

A correlational heat map of the features is provided in

Figure 4.

The second set of simulation utilized a dataset comprised of around 1000 crowd-sourced Python programming problems. The dataset is publicly available

1, and last accessed on the 01.08.2024. The problems are on the beginner level and consist of a description of the task, the solution, and 3 automated test cases. A generative model based on GPT-2 is used to generate solutions to these problems based off descriptive problems. Generated solutions that pass as well as fail at least one test case are collected and combined in to a unified dataset. The resulting dataset combines ground truth solutions with generated code that has some errors. The final combined dataset is comprised of 10000 samples and is balanced.

Both datasets are separated in to training and testing portions for simulations. An initial 70% of data is used for training and a later 30% for evaluation. Evaluations are carried out using a standard set of classification evaluation metrics including accuracy, recall, f1-score and precision. The Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) metric is used as the objective function that can be determined as per

22. An indicator function is also tracked. The indicator function is the Cohen’s kappa which is determined as per Eq.

23. Metaheuristics are tasked with selecting optimal parameters, maximizing the MCC score.

here true positives (TP) denotes samples correctly classified as positive, true negatives (TN) denotes instances correctly classified as negative. Similarly false positives (FP) and false negatives (FN) denote samples incorrectly classified as positive and negative respectively.

In the first layer CNN parameters are optimized. The respective parameters and their constraints are provided in

Table 1.

In the second optimization layer, intermediate outputs of the CNN are used. The final dense layer is recorded during classifications of all the samples available in the dataset. This is once again separated in to 70% for training and 30% for testing. These are then utilized to training and optimize AdaBoost and XGBoost models. Parameter ranges for AdaBoost and XGBoost are provided in

Table 2 and

Table 3 respectively.

Several optimizers are included in a comparative analysis against the proposed modified algorithm. These include the original PSO [

32], as well as several other established optimizers such as the GA [

34] and VNS [

15]. Additional optimizers included in the comparison are the ABC [

16], BA [

17] and COLSHADE [

18] optimizers. A recently proposed SCHO [

19] optimizer is also explored. Each optimizer is implemented using original parameter settings suggested in the works that introduced said algorithm. Optimizes are allocated a population size of 10 agents and allowed a total of 8 iterations to locate promising outcomes within the given search range. Simulations are carried out through 30 independent executions to facilitate further analysis.

For NLP simulations, only a the second layer of the framework is utilized. Input text is encoded using TF-IDF encoding to a maximum of 1000 tokens. These are used as inputs for model training and evaluation. Optimization is carried out using the second layer of the introduced framework and a comparative analyses is conducted under identical conditions as previous simulations to demonstrate the flexibility of the proposed approach.

6. Conclusion

Software has become increasingly integral to societal infrastructure, governing critical systems. Ensuring the reliability of software is therefore paramount across various industries. As the demand for accelerated development intensifies, the manual review of code presents growing challenges, with testing frequently consuming more time than development. A promising method for detecting defects at the source code level involves the integration of AI with NLP. Given that software is composed of human-readable code, which directs machine operations, the validation of the highly diverse machine code on a case-by-case basis is inherently complex. Consequently, source code analysis offers a potentially effective approach to improving defect detection and preventing errors.

This work explores the advantages and challenges of utilizing AI for error detection in software code. Both classical and NLP methods are explored on two publicly available dataset with 5 experiments total conducted. A two layer optimization framework is introduced in order to manage the complex demands of error detection. A CNN architecture is utilized in the first layer to help process the large amounts of data in a more computational efficient manner, with the second layer handling intermediate results using AdaBoost and XGBoost classifiers. An additional set of simulations using only the second layer of the framework in combination with TF-IDF encoding is also carried out in order to provide a comparison between emerging NLP and classical techniques. As optimizer performance is highly dependant on adequate parameter selection, a modified version of the well established PSO is introduced, designed specifically for the needs of this research and with an aim to overcome some of the known drawback of the original algorithm. A comparative analysis is carried out with several state of the art optimizes with the introduced approach demonstrative promising outcomes in several simulations.

Twin layer simulations improve upon the baseline outcomes demonstrated by CNN boost accuracy form 0.768799 to 0.772166 for the AdaBoost models and 0.771044 for the XGBoost best performing classifier. This suggests that a two layer approach can yield favorable outcomes while maintaining favorable computational demands in comparison to more complex network solutions. Optimization carried out using NLP demonstrate an impressive accuracy of 0.979781 for the best performing AdaBoost model and a 0.983893 for the best performing XGBoost model. Simulations are further validated using statistical evaluation to confirm the significance of the observations. The best preforming models are also subjected to SHAP analysis to determine feature importance and help locate any potential hidden biases within the best performing models.

It is worth noting that the extensive computational demands of the optimizations carried out in this work limit the extend of optimizers that can be tested. Further limitations are associated with population sized and allocated numbers of iterations for each optimization due to hardware memory limitations. Future works hope to address these concerns as additional resources become available. Additional implementations of the proposed MPPSO hope to be explored for other implementations. Emerging transformer based architectures based on custom BERT encoding also hope to be explored for software defect detection in future works.

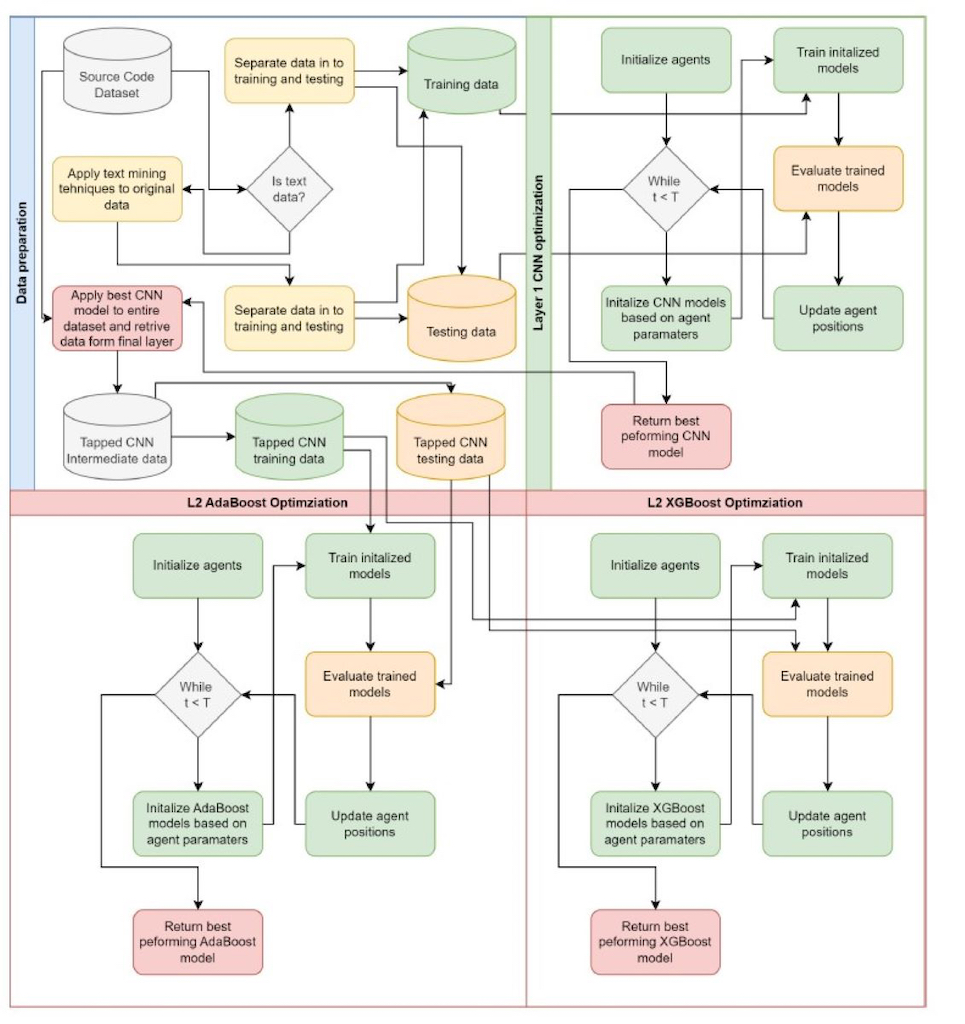

Figure 1.

Crossover and mutation mechanisms.

Figure 1.

Crossover and mutation mechanisms.

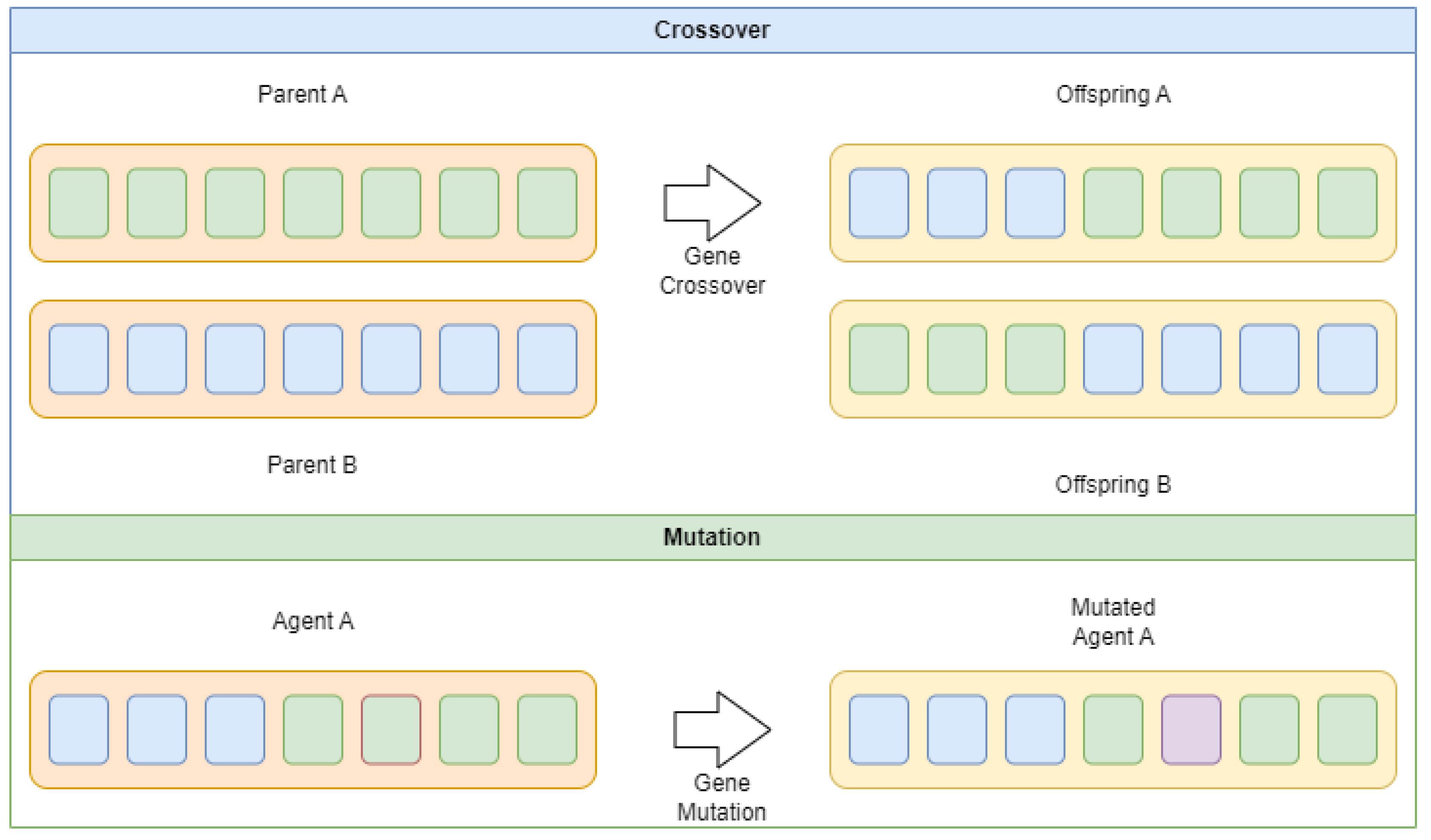

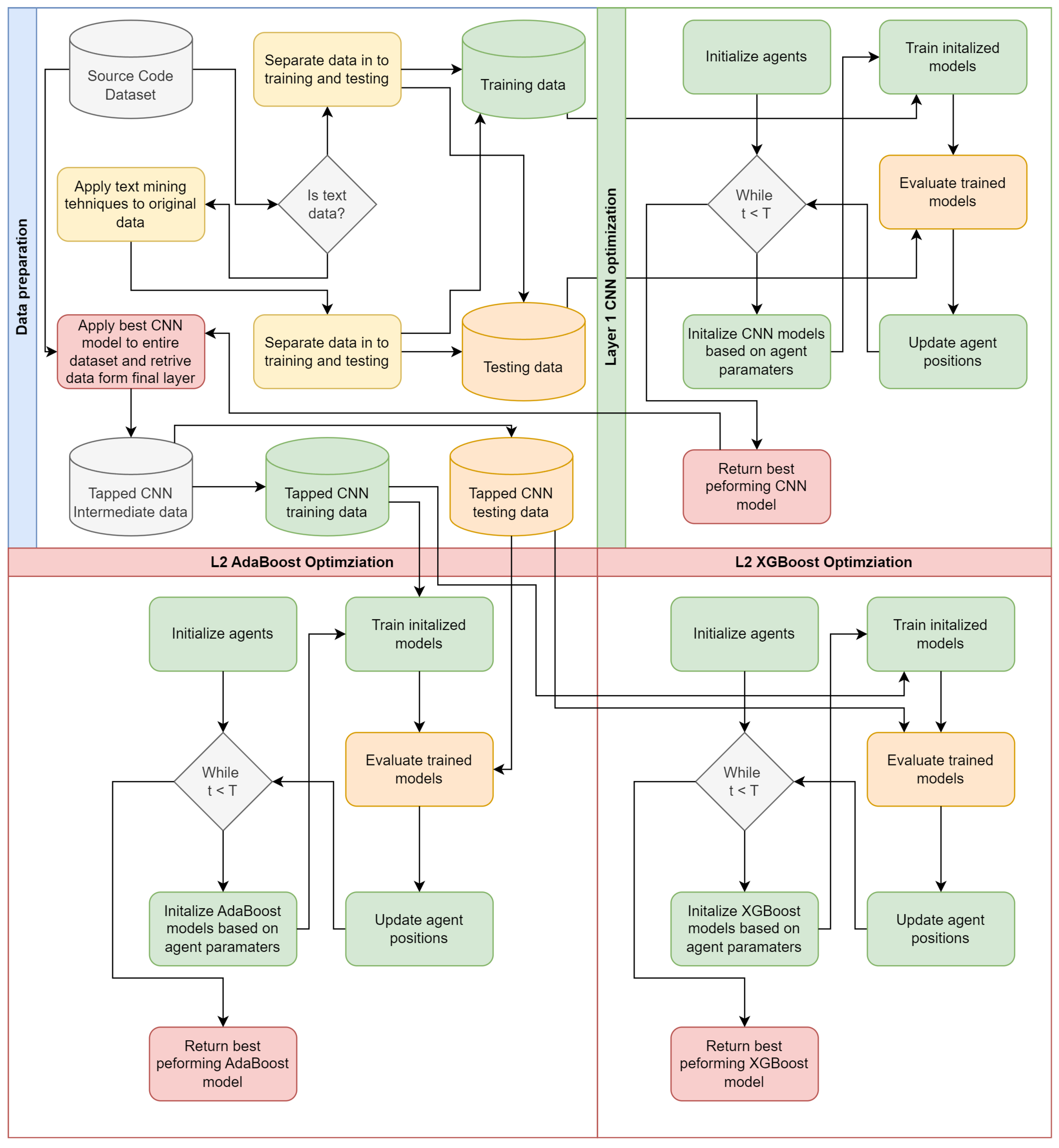

Figure 2.

Proposed optimization framework flowchart

Figure 2.

Proposed optimization framework flowchart

Figure 3.

Class distribution in NASA dataset.

Figure 3.

Class distribution in NASA dataset.

Figure 4.

NASA feature correlation heat-map.

Figure 4.

NASA feature correlation heat-map.

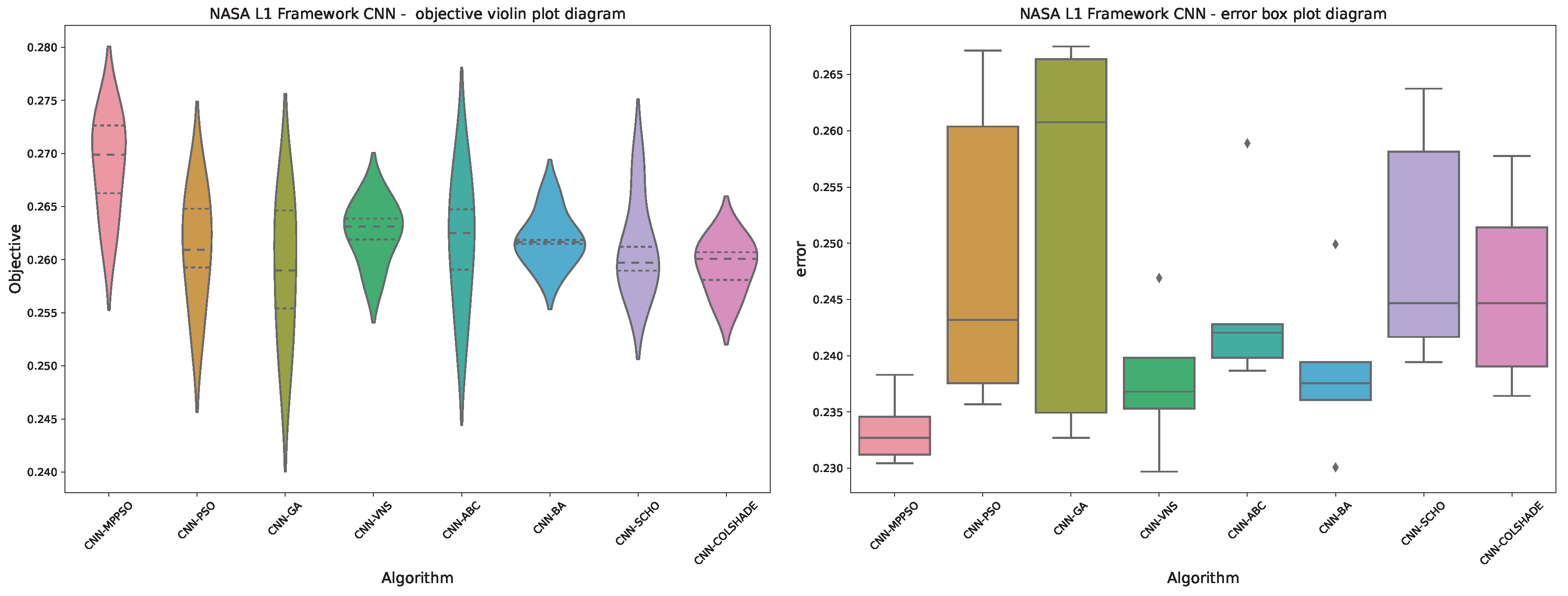

Figure 5.

Layer 1 (CNN) objective and indicator outcome distributions.

Figure 5.

Layer 1 (CNN) objective and indicator outcome distributions.

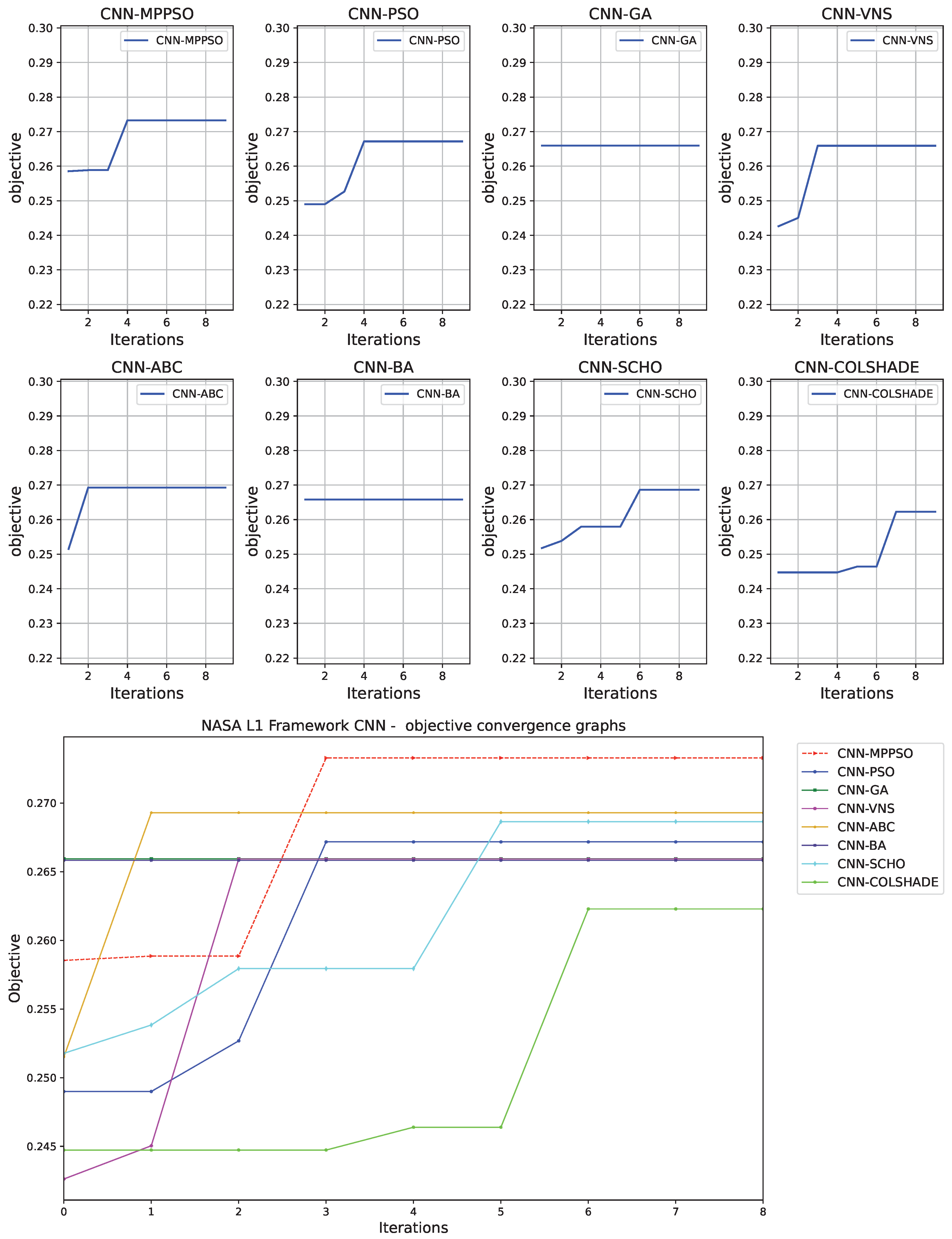

Figure 6.

Layer 1 (CNN) objective function convergence.

Figure 6.

Layer 1 (CNN) objective function convergence.

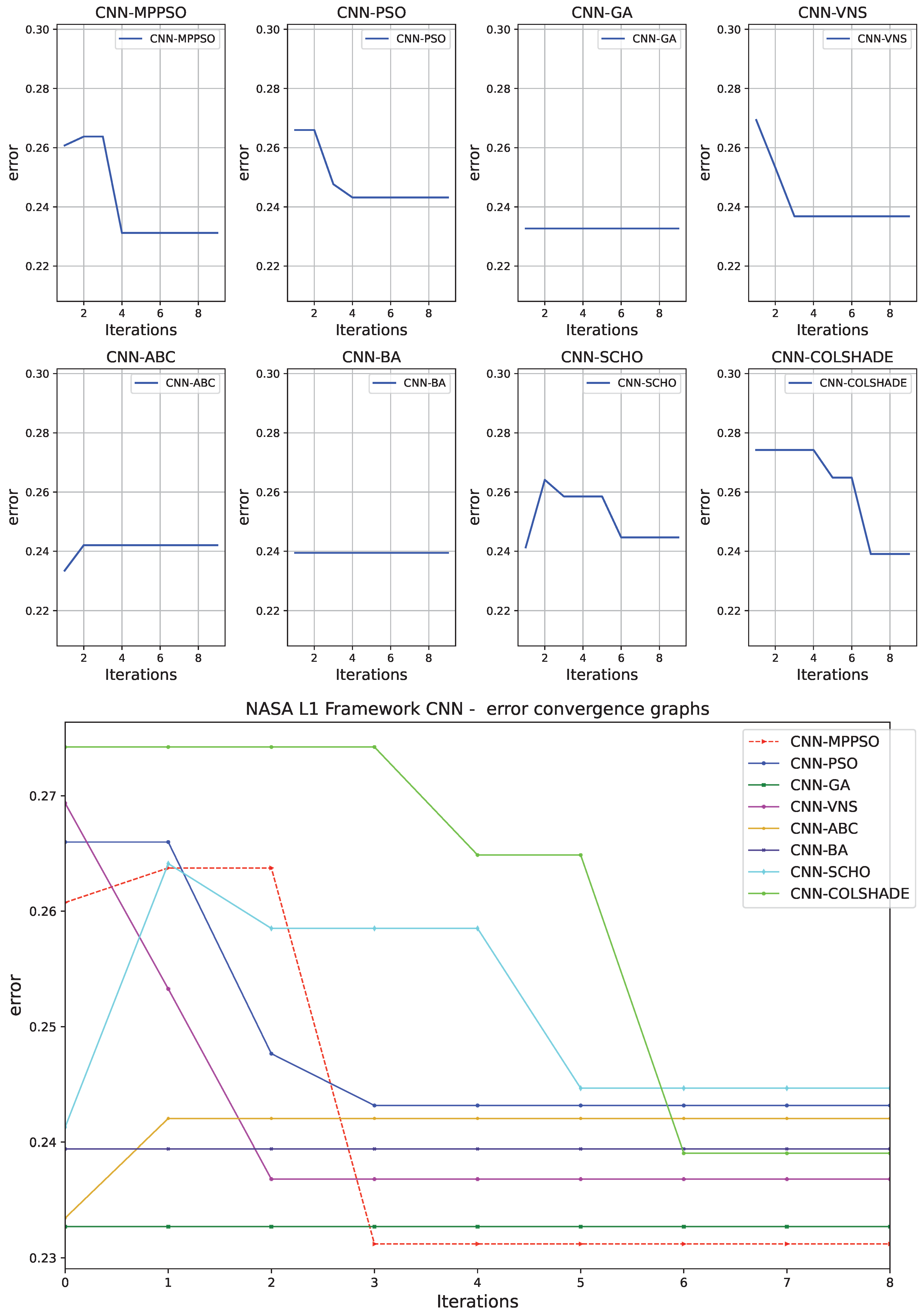

Figure 7.

Layer 1 (CNN) indicator function convergence.

Figure 7.

Layer 1 (CNN) indicator function convergence.

Figure 8.

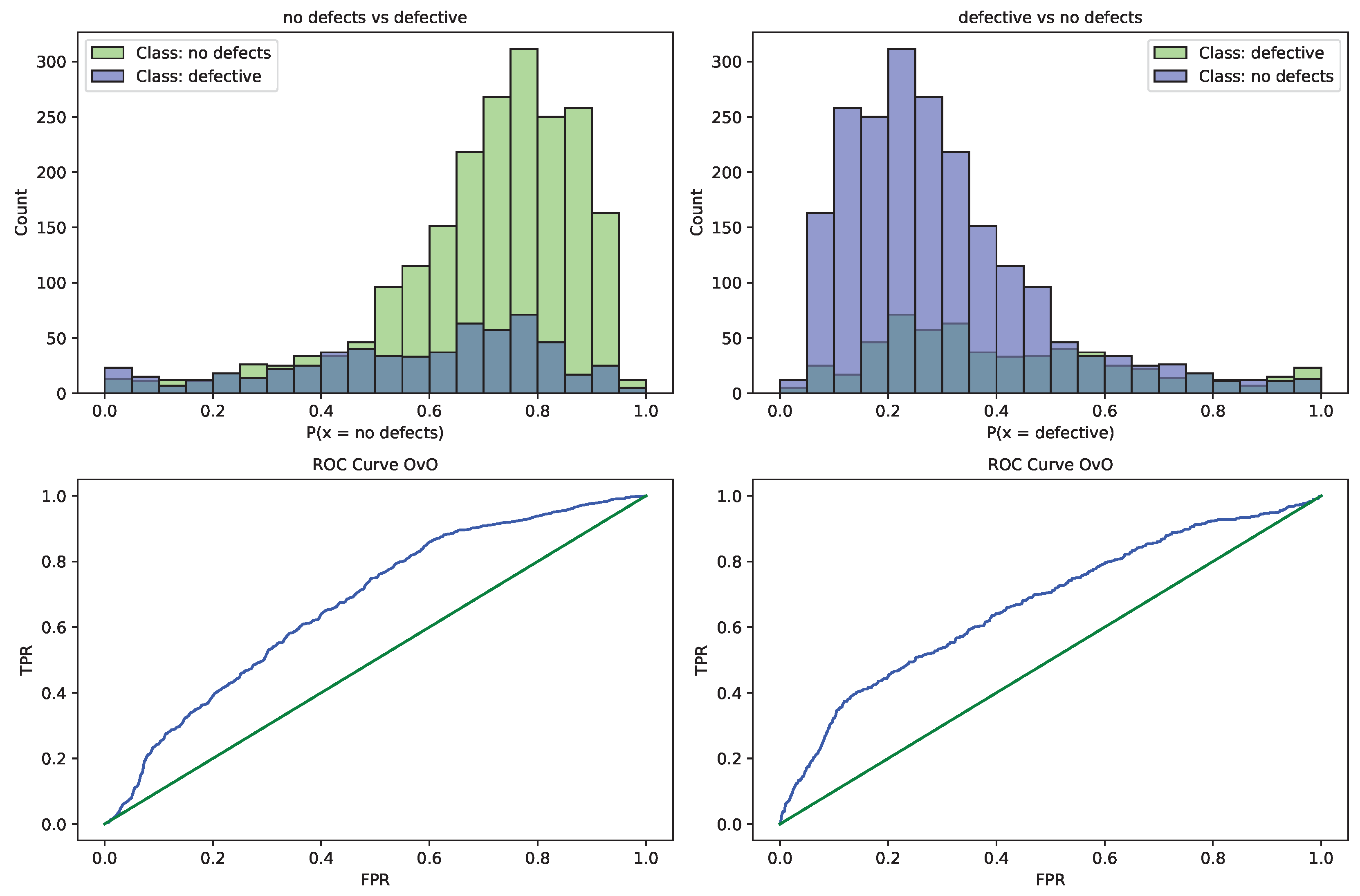

CNN-MPPSO optimized L1 model ROC curve.

Figure 8.

CNN-MPPSO optimized L1 model ROC curve.

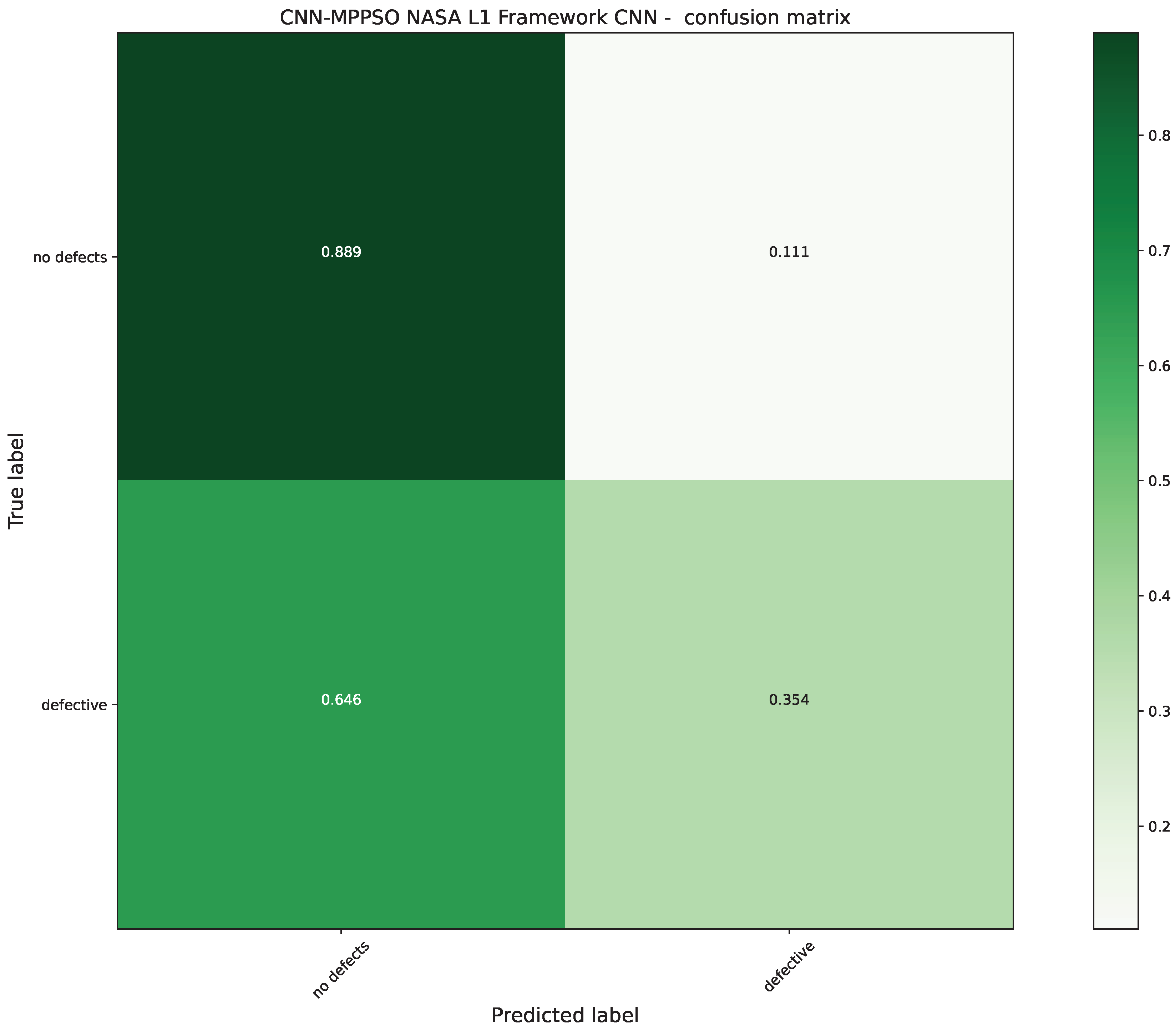

Figure 9.

CNN-MPPSO optimized L1 model confusion matrix.

Figure 9.

CNN-MPPSO optimized L1 model confusion matrix.

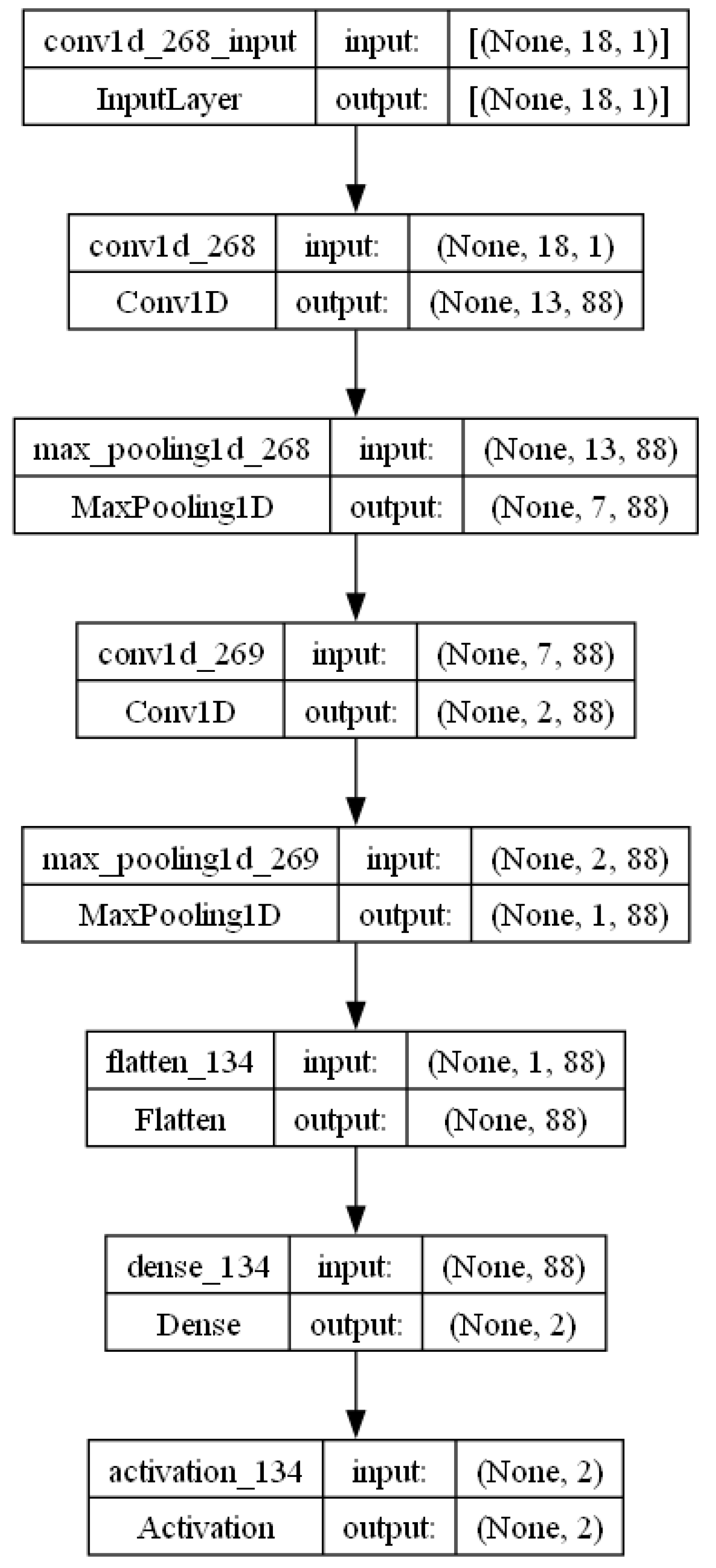

Figure 10.

Best CNN-MPPSO optimized L1 model visualization.

Figure 10.

Best CNN-MPPSO optimized L1 model visualization.

Figure 11.

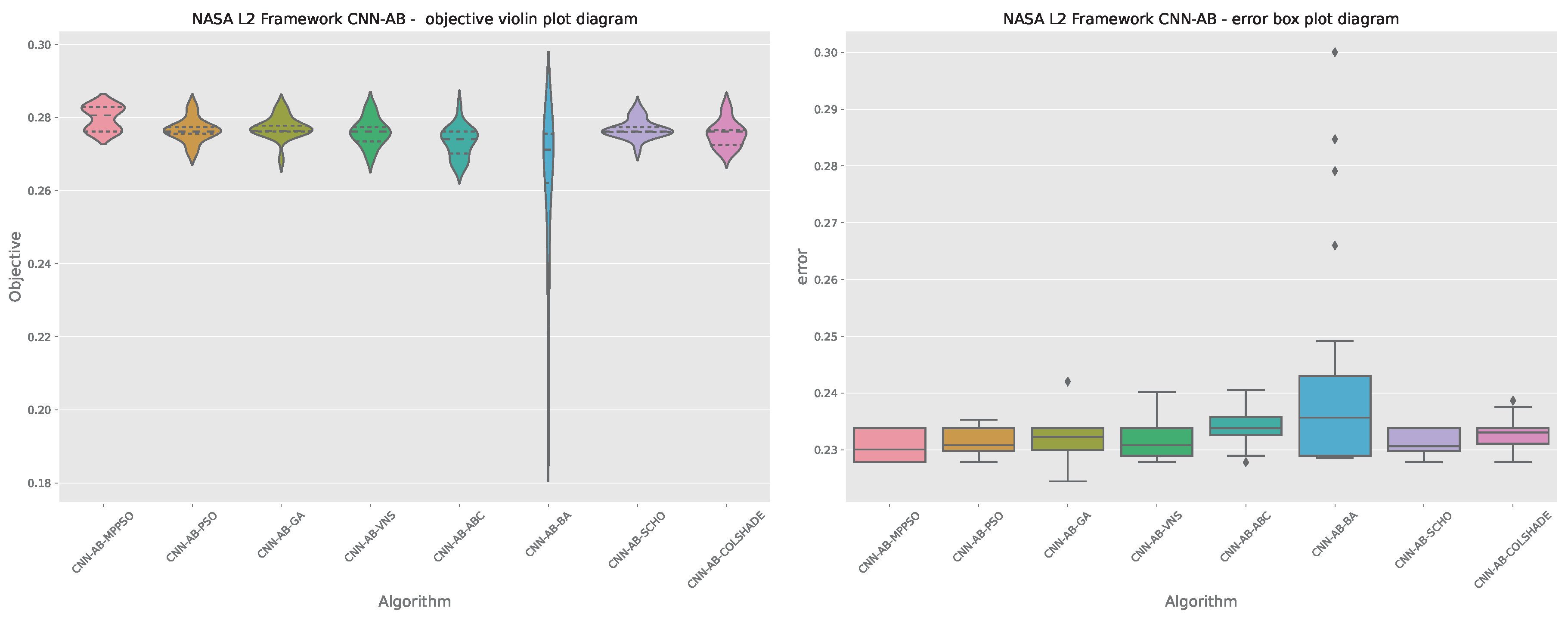

Layer 2 AdaBoost objective and indicator outcome distributions.

Figure 11.

Layer 2 AdaBoost objective and indicator outcome distributions.

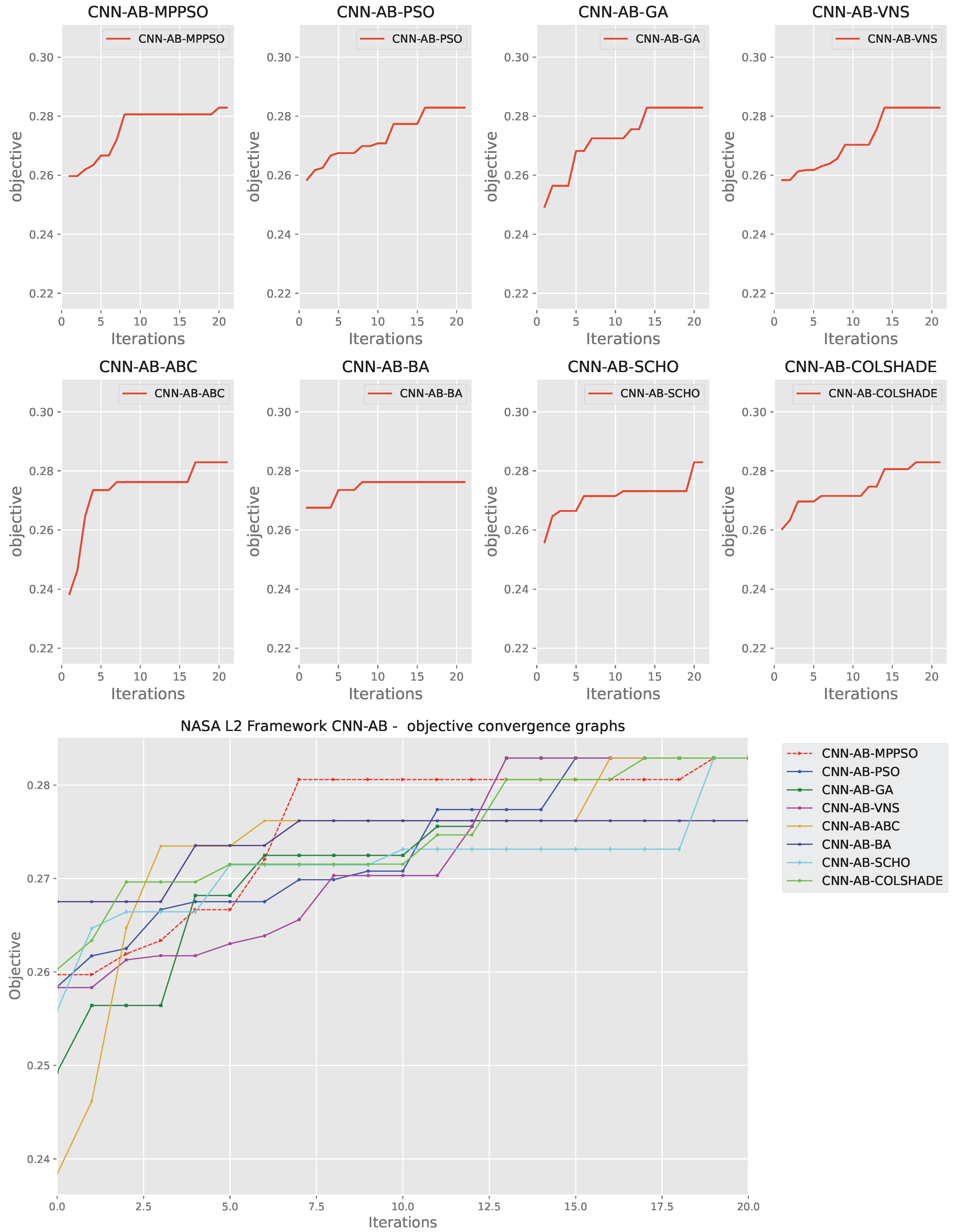

Figure 12.

Layer 2 AdaBoost objective function convergence.

Figure 12.

Layer 2 AdaBoost objective function convergence.

Figure 13.

Layer 2 AdaBoost indicator function convergence.

Figure 13.

Layer 2 AdaBoost indicator function convergence.

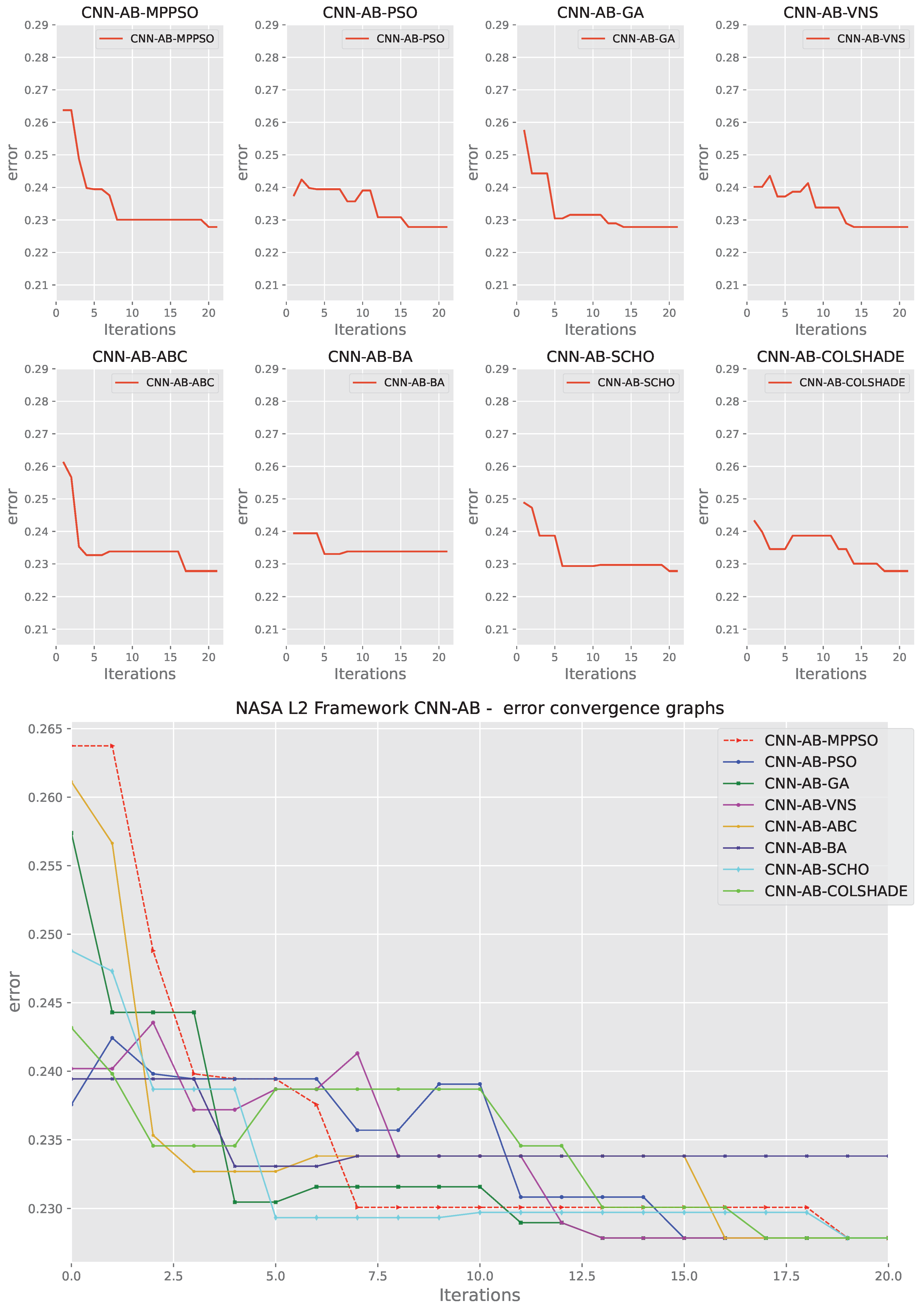

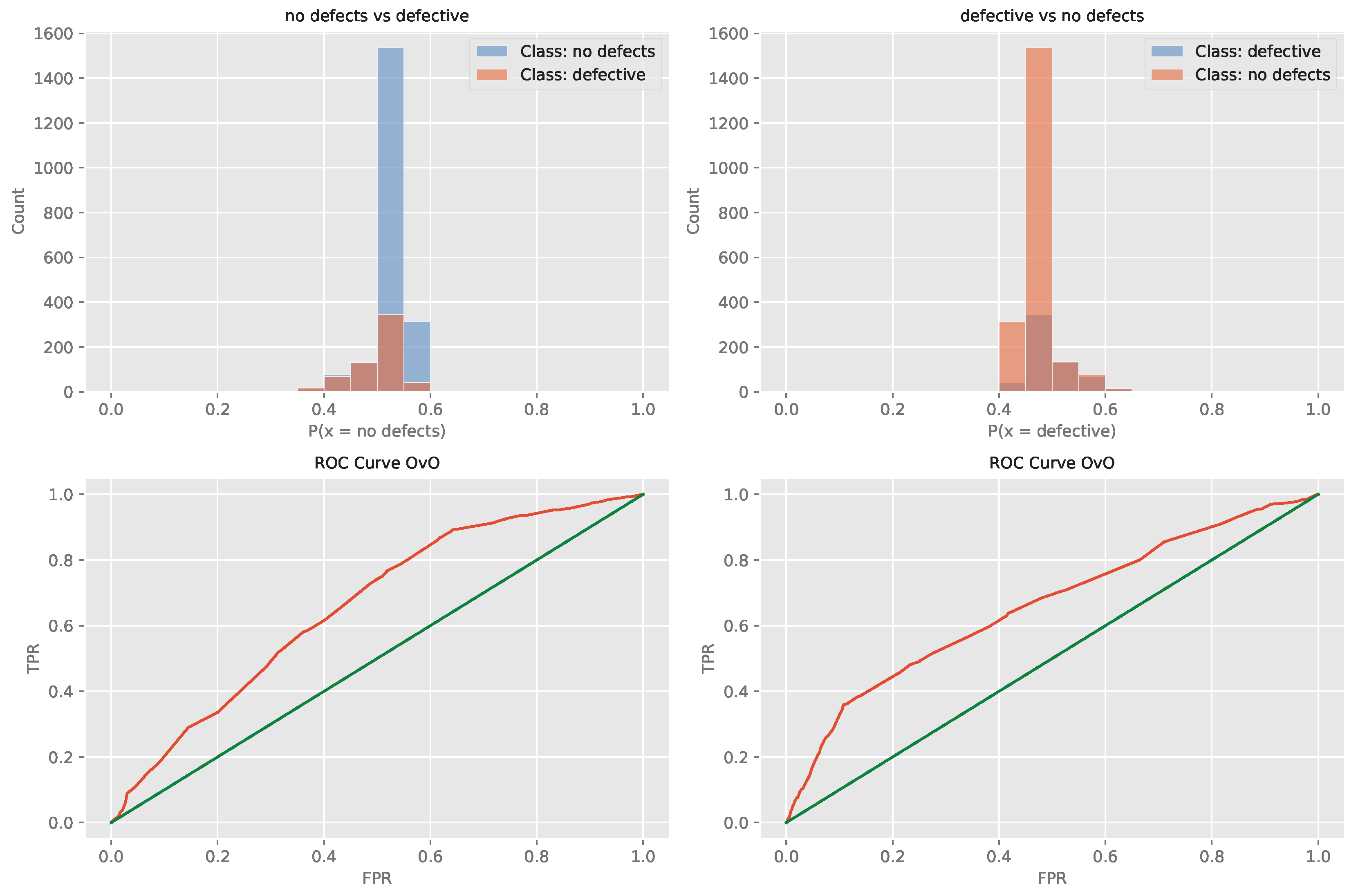

Figure 14.

Layer 2 AdaBoost optimized L1 model ROC curve.

Figure 14.

Layer 2 AdaBoost optimized L1 model ROC curve.

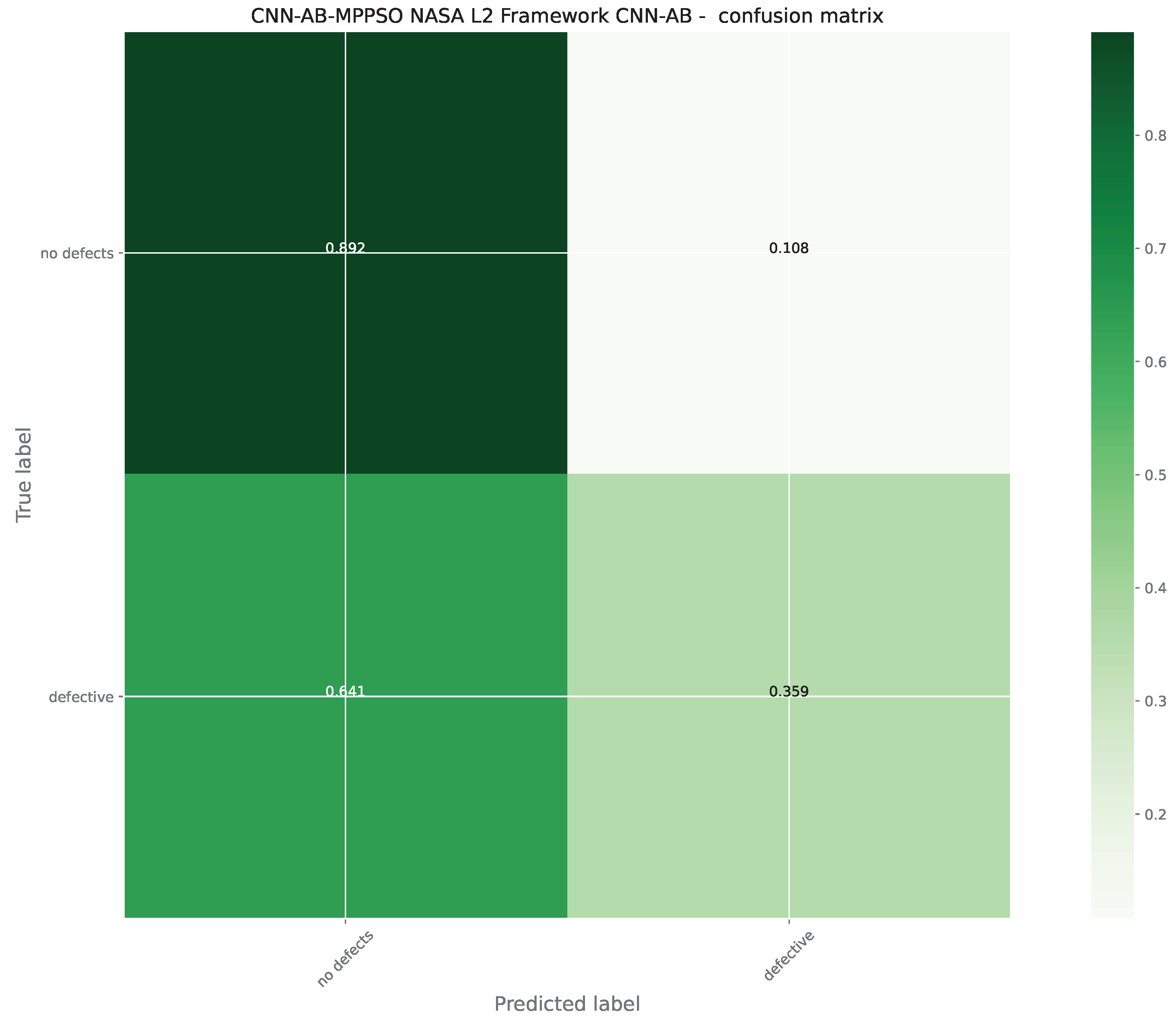

Figure 15.

Layer 2 AdaBoost optimized L1 model confusion matrix.

Figure 15.

Layer 2 AdaBoost optimized L1 model confusion matrix.

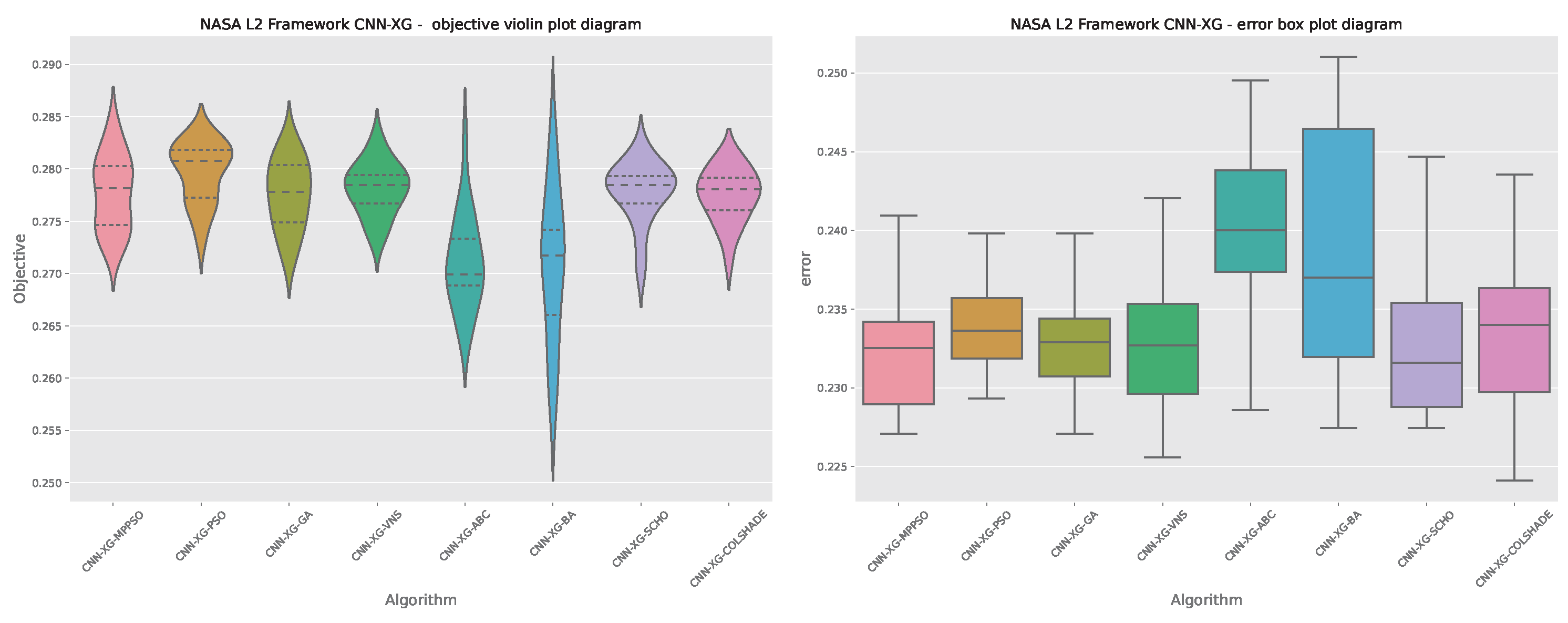

Figure 16.

Layer 2 XGBoost objective and indicator outcome distributions.

Figure 16.

Layer 2 XGBoost objective and indicator outcome distributions.

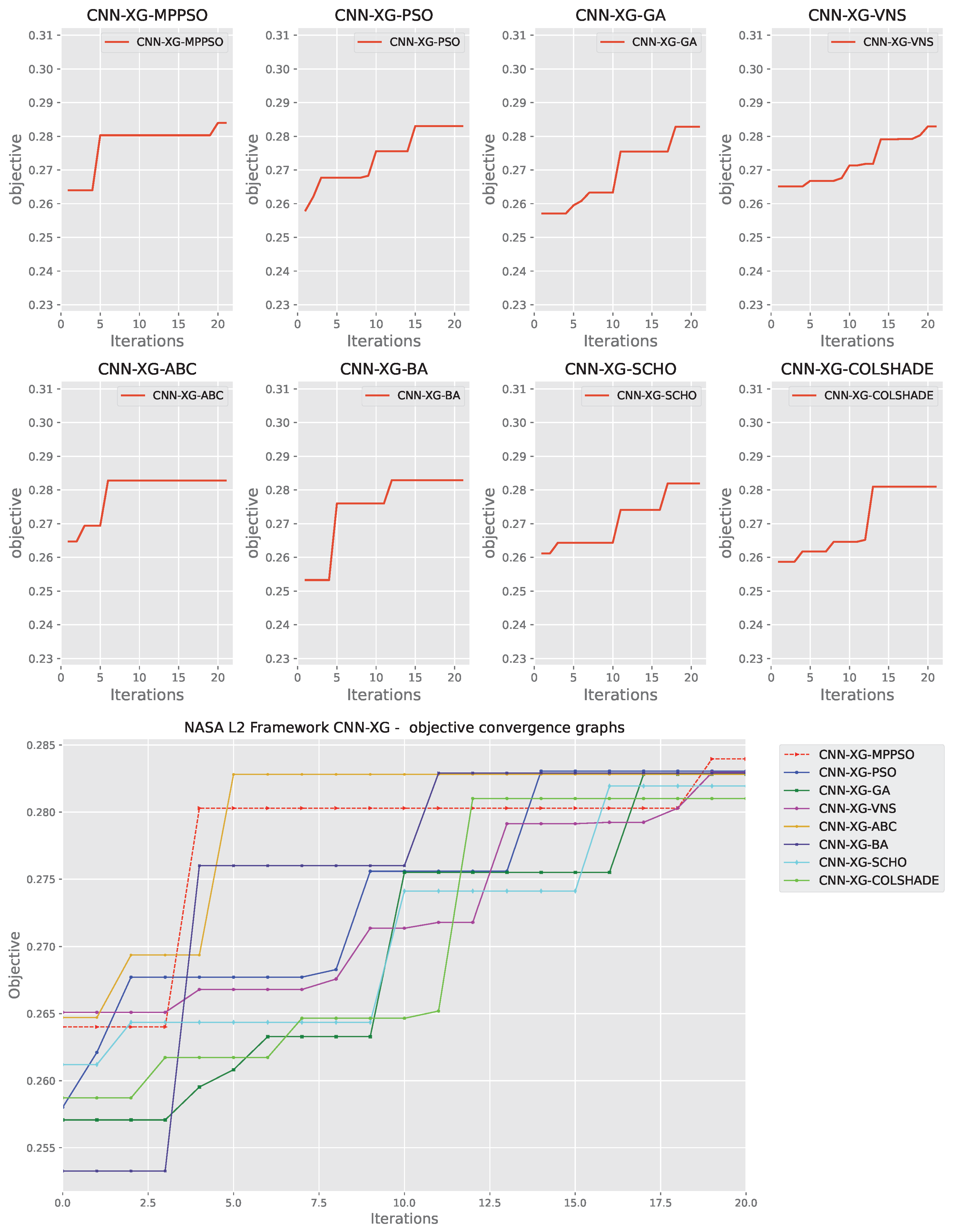

Figure 17.

Layer 2 XGBoost objective function convergence.

Figure 17.

Layer 2 XGBoost objective function convergence.

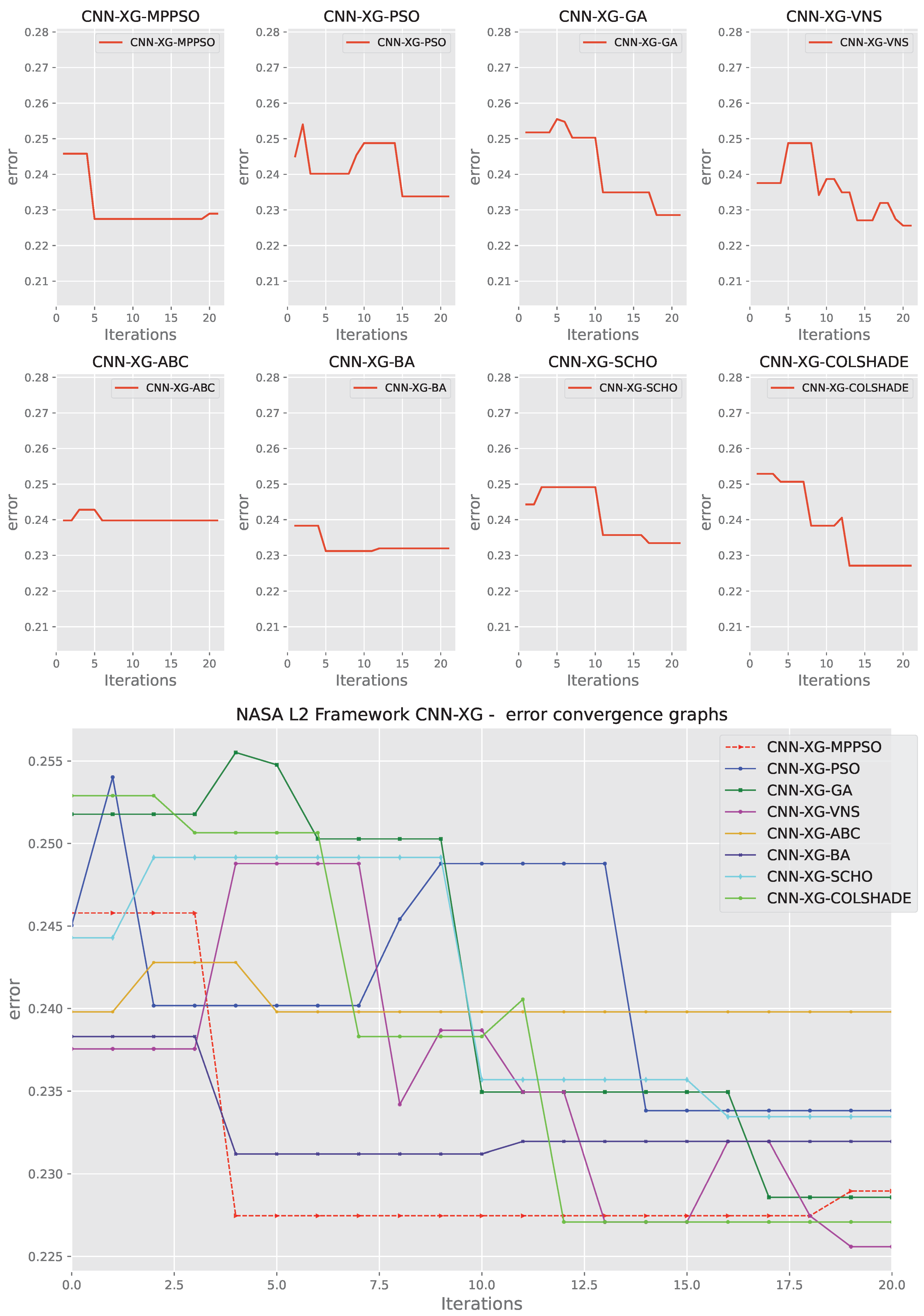

Figure 18.

Layer 2 XGBoost indicator function convergence.

Figure 18.

Layer 2 XGBoost indicator function convergence.

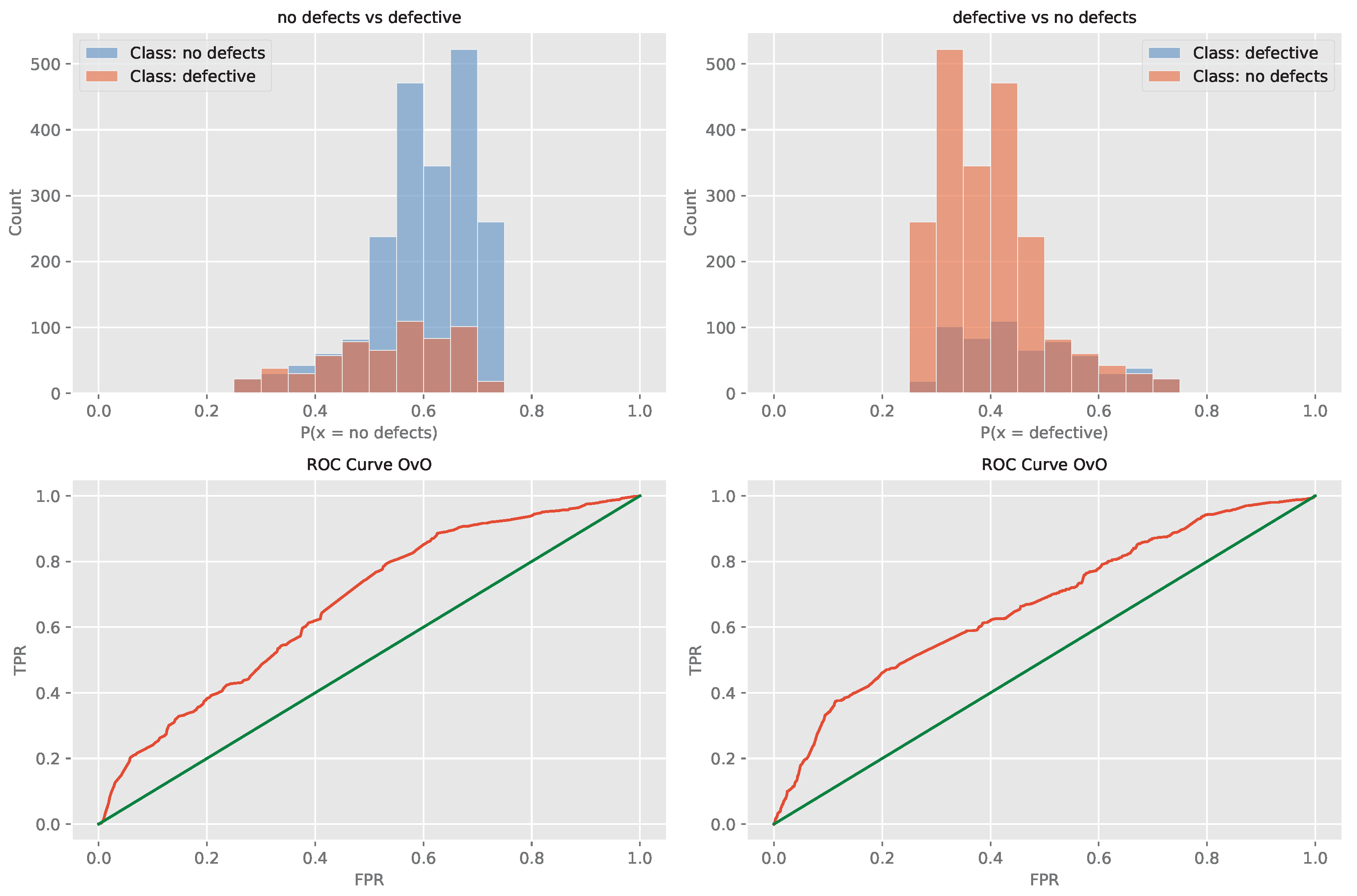

Figure 19.

Layer 2 XGBoost optimized L1 model ROC curve.

Figure 19.

Layer 2 XGBoost optimized L1 model ROC curve.

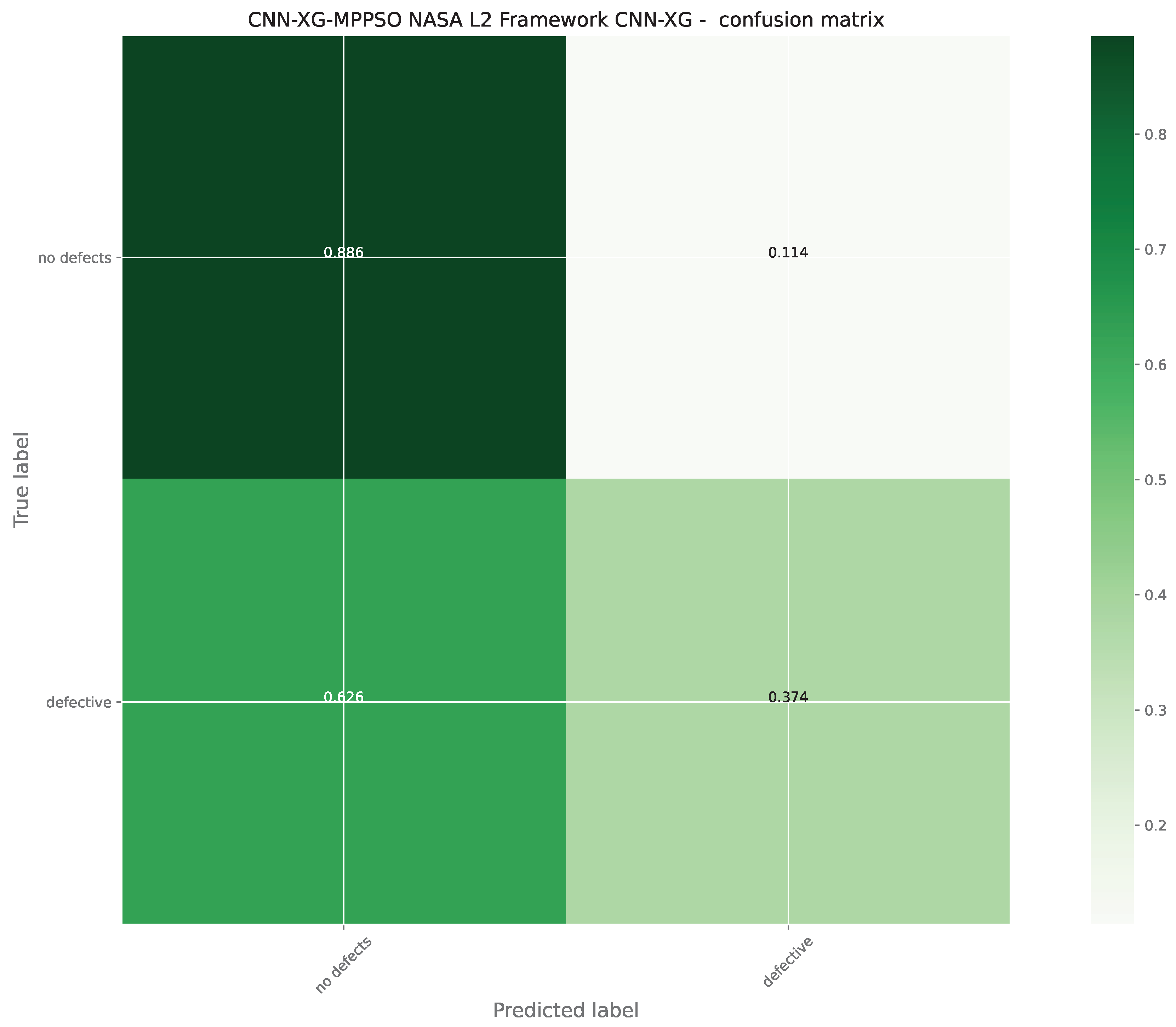

Figure 20.

Layer 2 XGBoost optimized L1 model confusion matrix.

Figure 20.

Layer 2 XGBoost optimized L1 model confusion matrix.

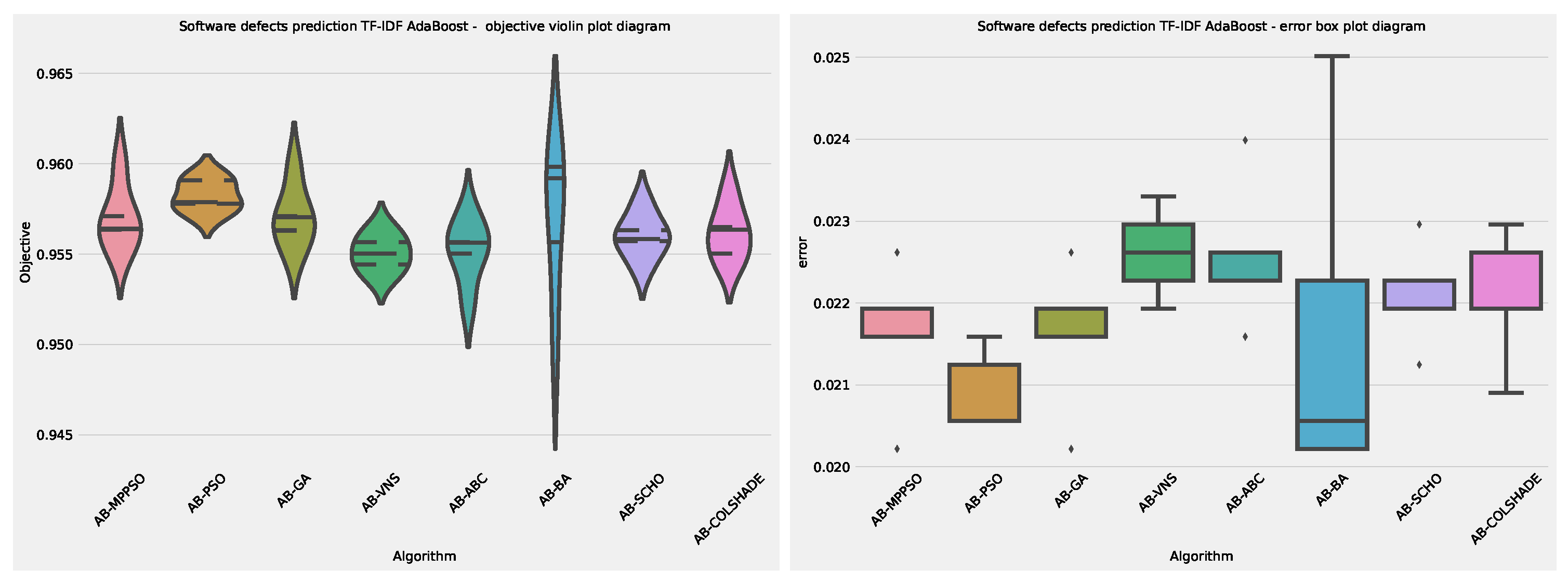

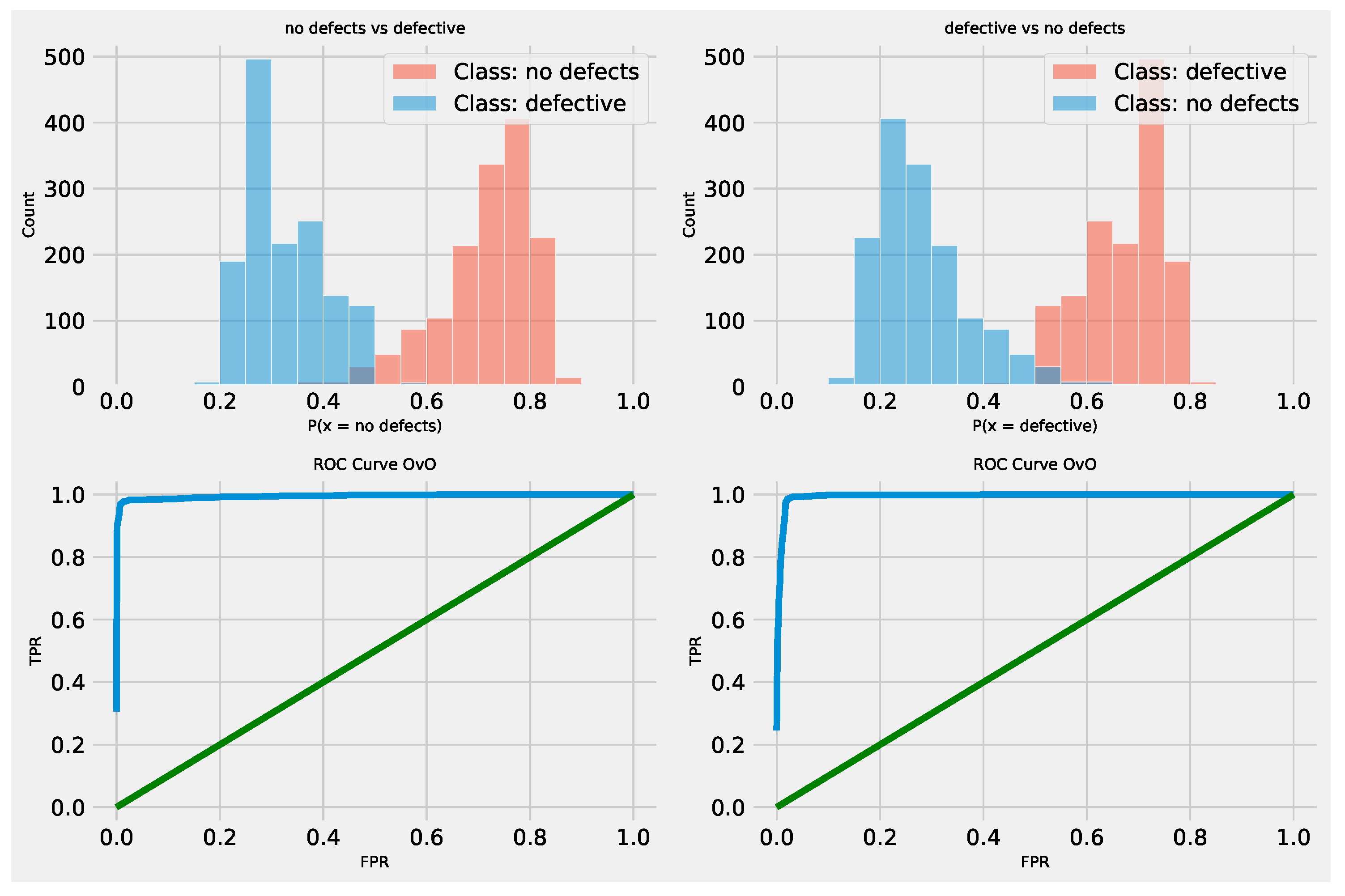

Figure 21.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost and indicator outcome distributions.

Figure 21.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost and indicator outcome distributions.

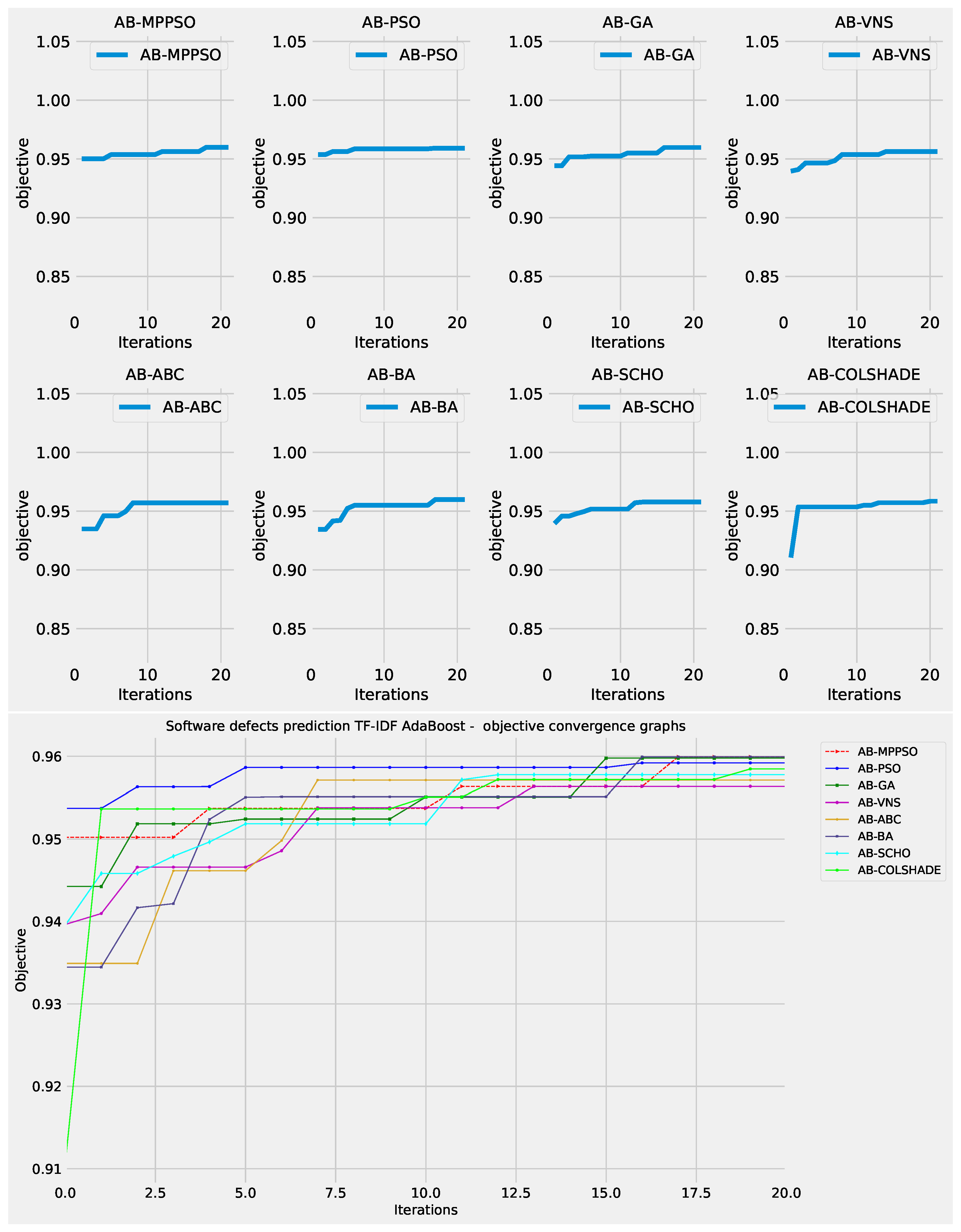

Figure 22.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost objective function convergence.

Figure 22.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost objective function convergence.

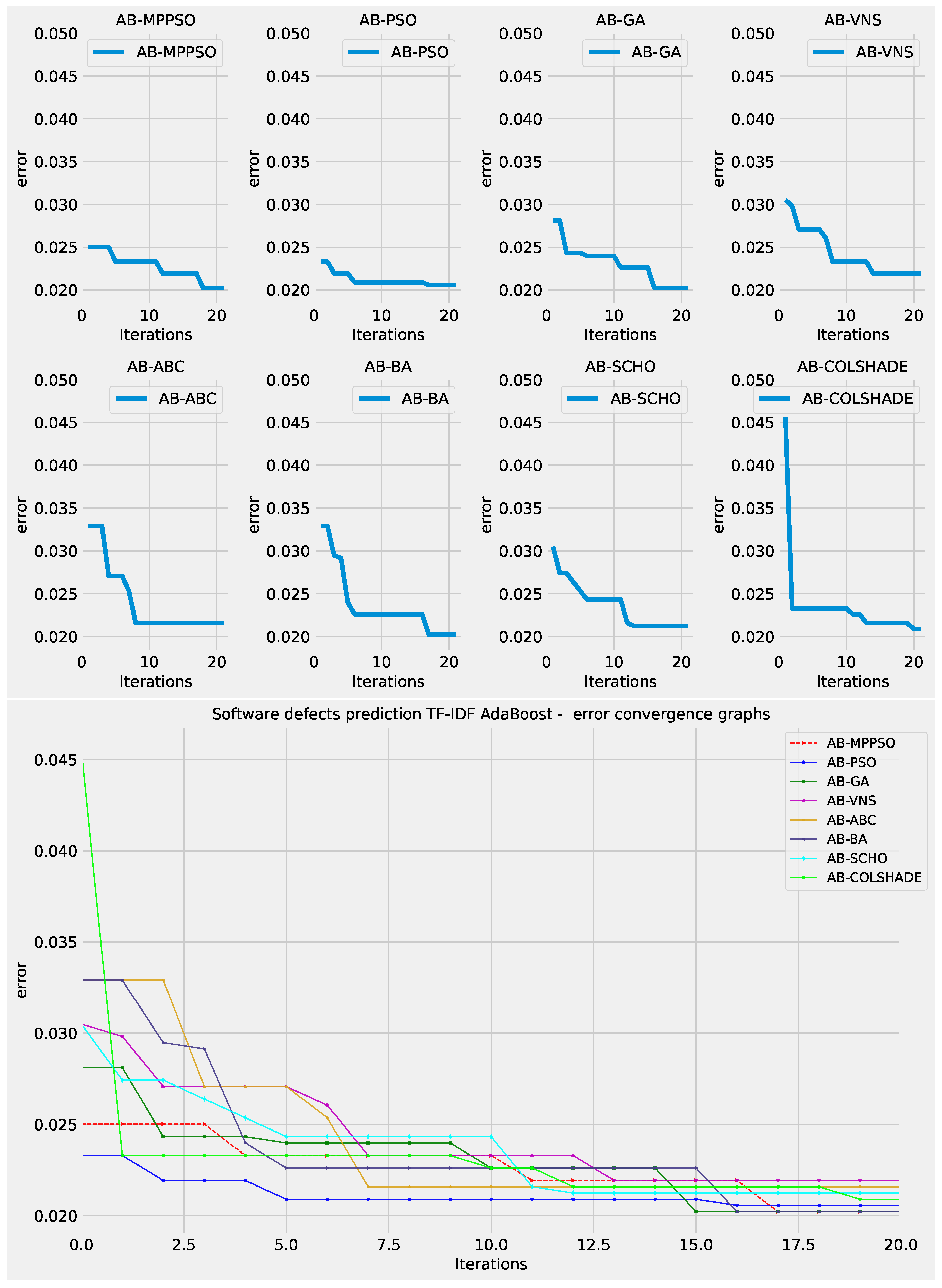

Figure 23.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost indicator function convergence.

Figure 23.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost indicator function convergence.

Figure 24.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost optimized model ROC curve.

Figure 24.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost optimized model ROC curve.

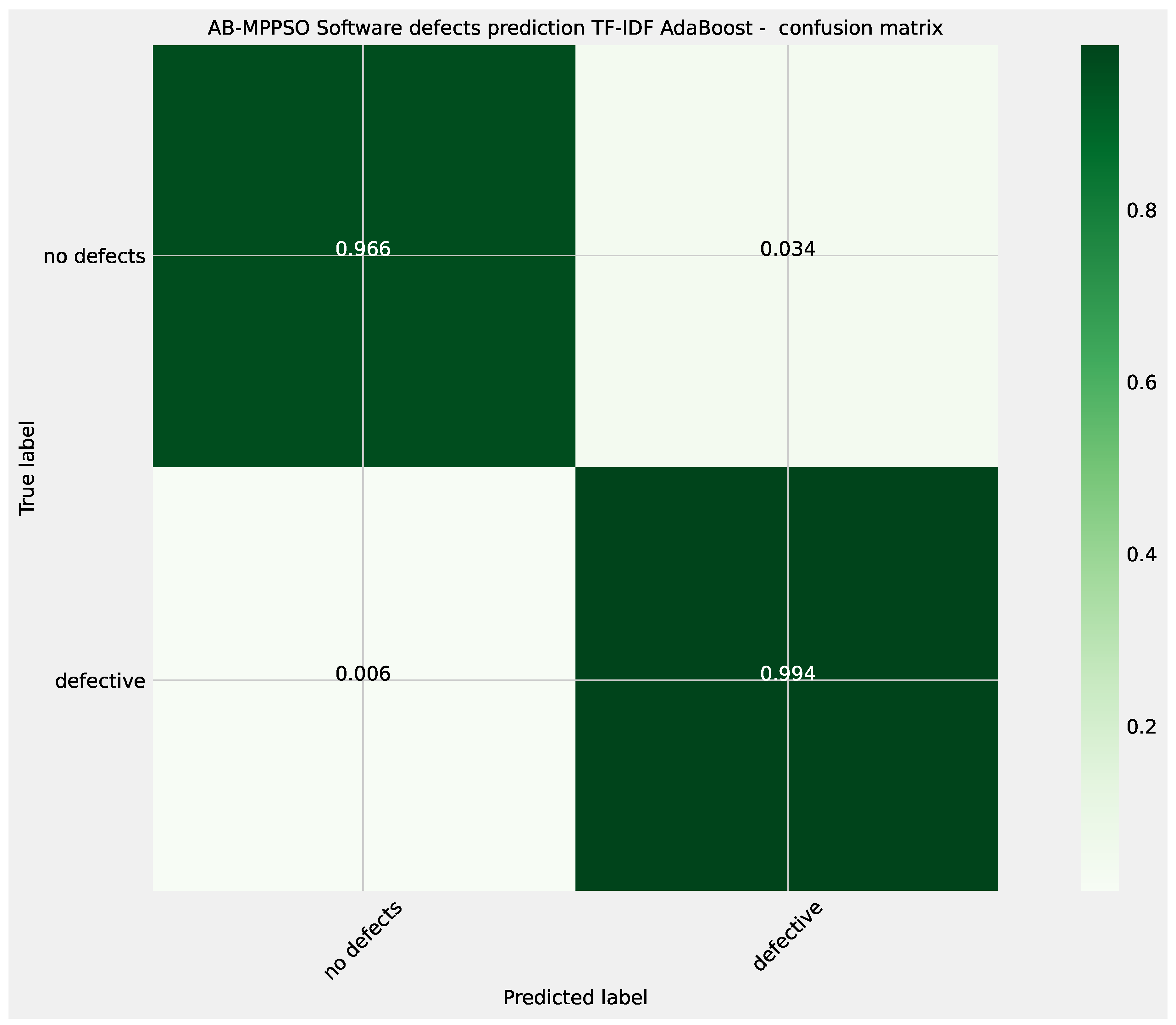

Figure 25.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost optimized model confusion matrix.

Figure 25.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost optimized model confusion matrix.

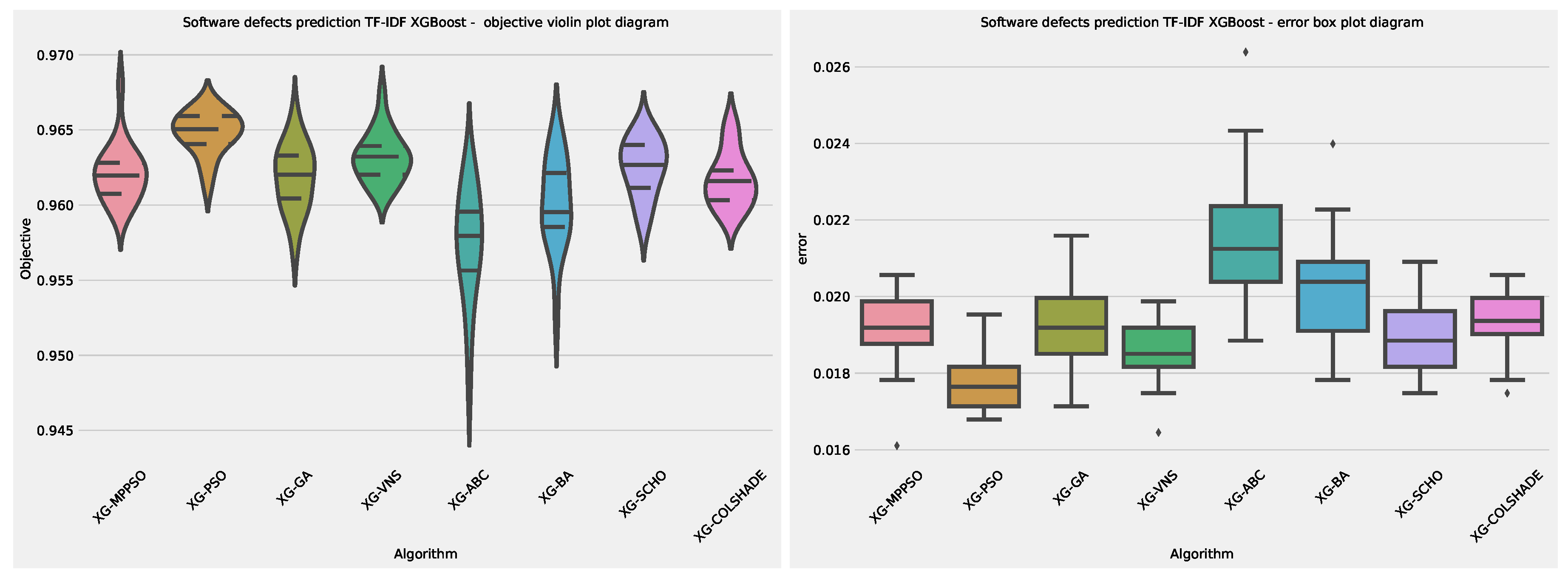

Figure 26.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost and indicator outcome distributions.

Figure 26.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost and indicator outcome distributions.

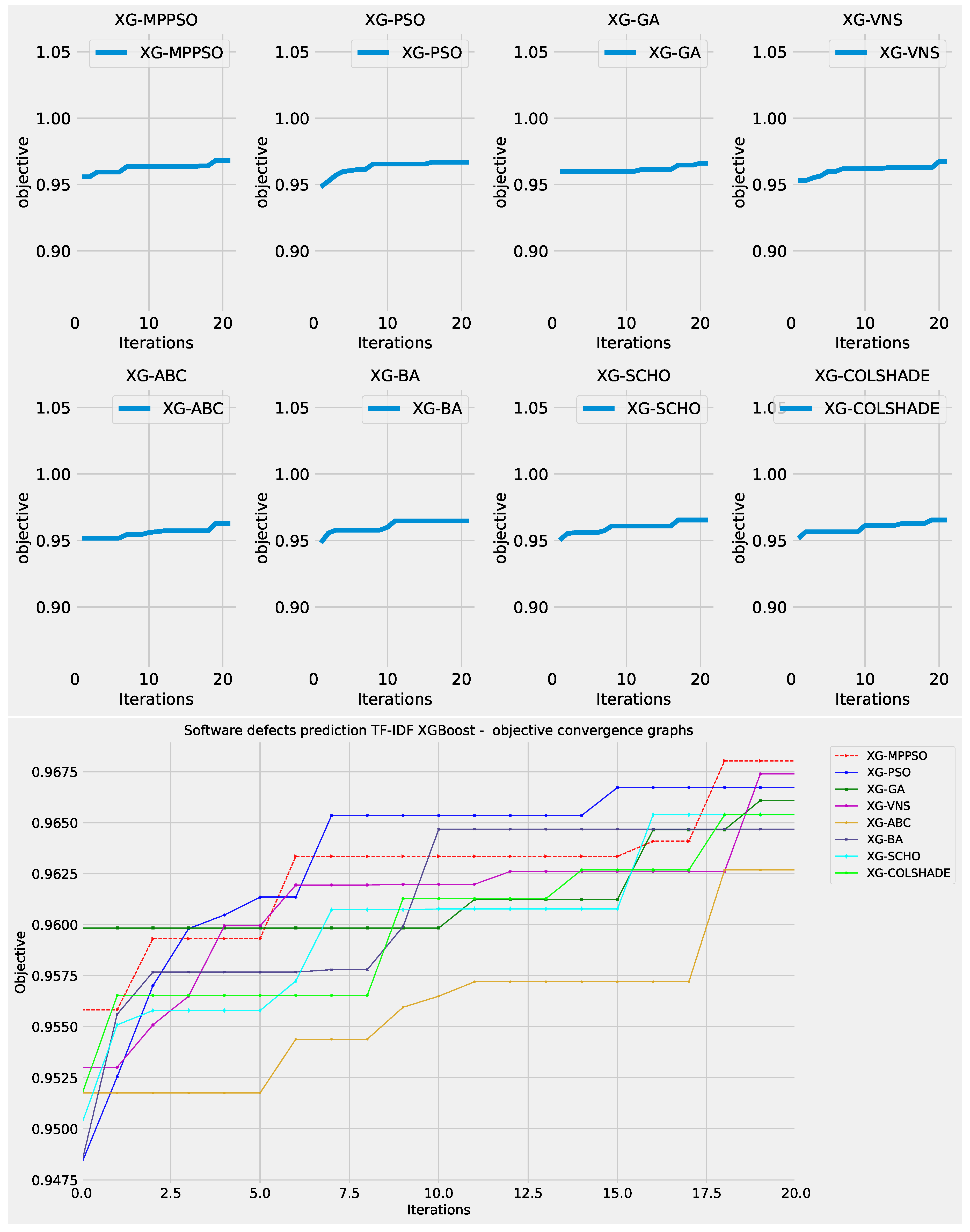

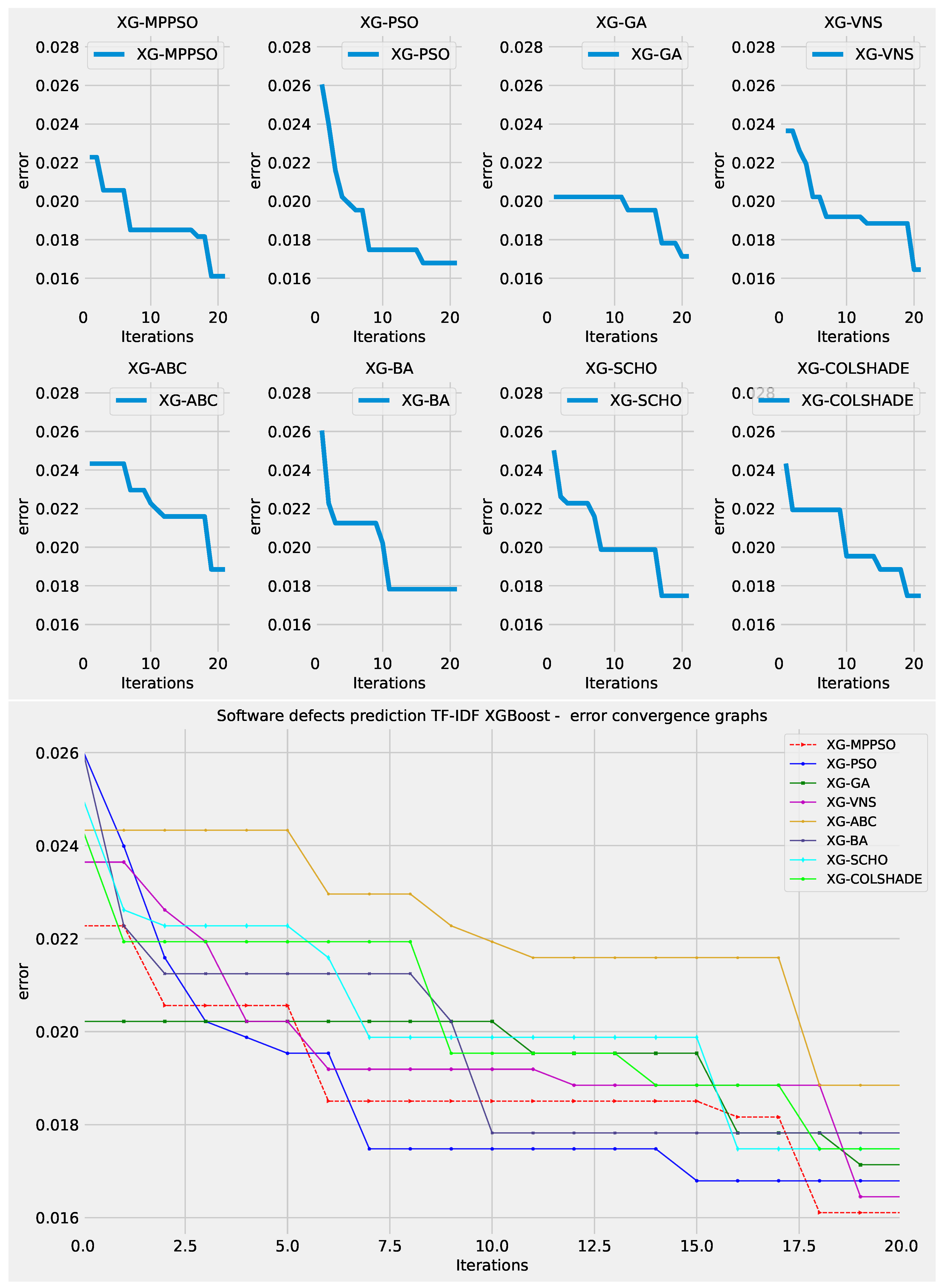

Figure 27.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost objective function convergence.

Figure 27.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost objective function convergence.

Figure 28.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost indicator function convergence.

Figure 28.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost indicator function convergence.

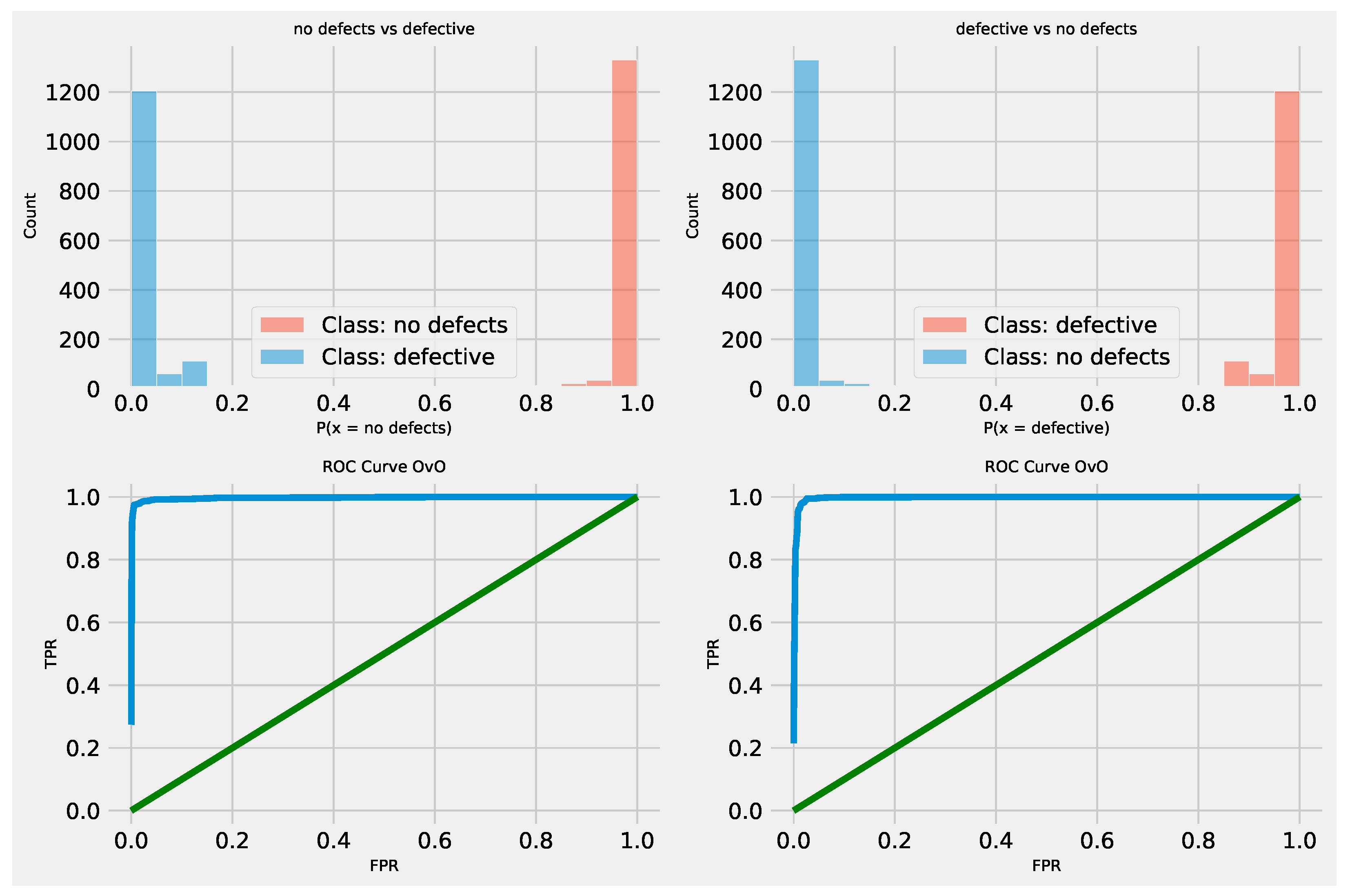

Figure 29.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost optimized model ROC curve.

Figure 29.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost optimized model ROC curve.

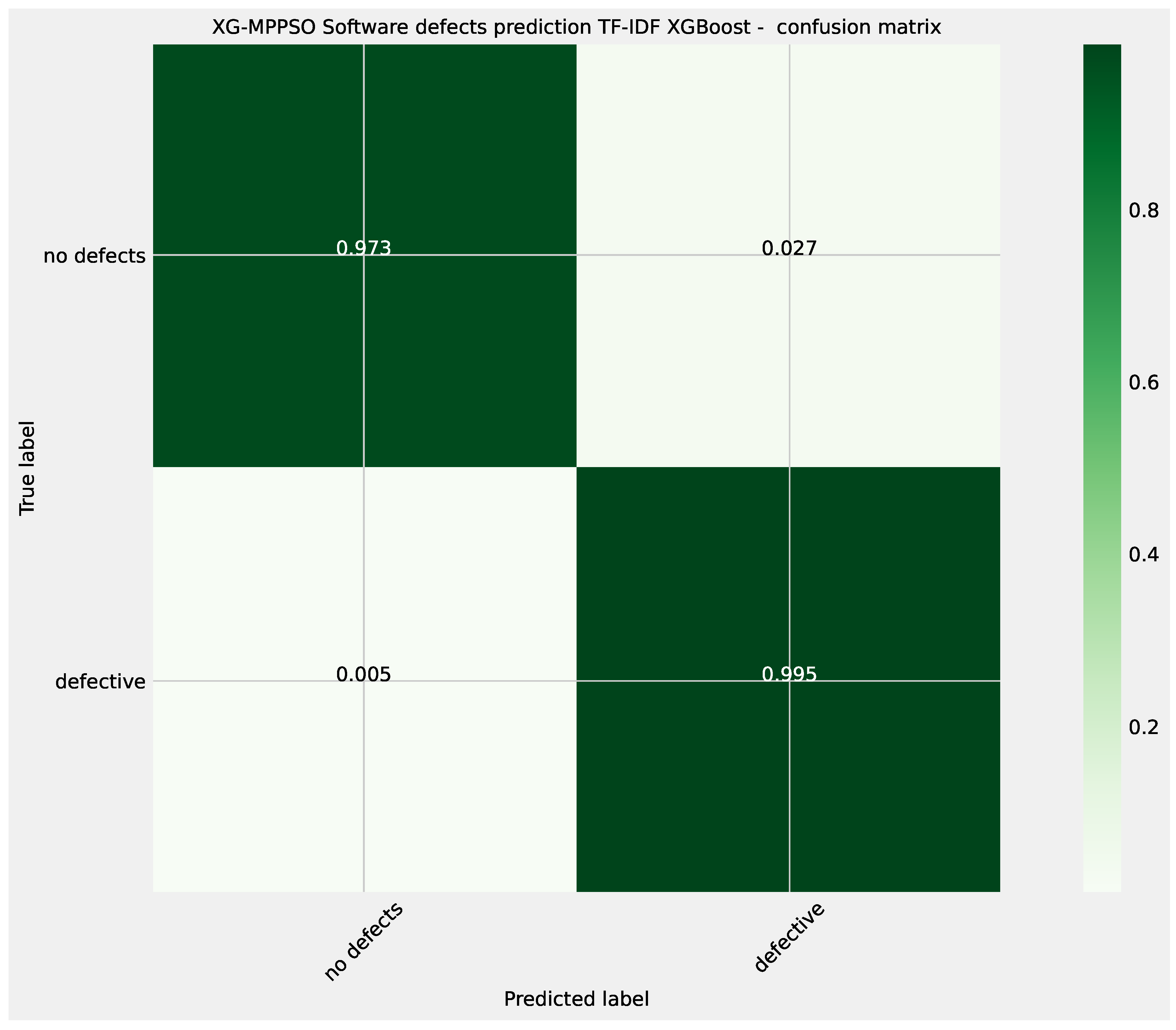

Figure 30.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost optimized model confusion matrix.

Figure 30.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost optimized model confusion matrix.

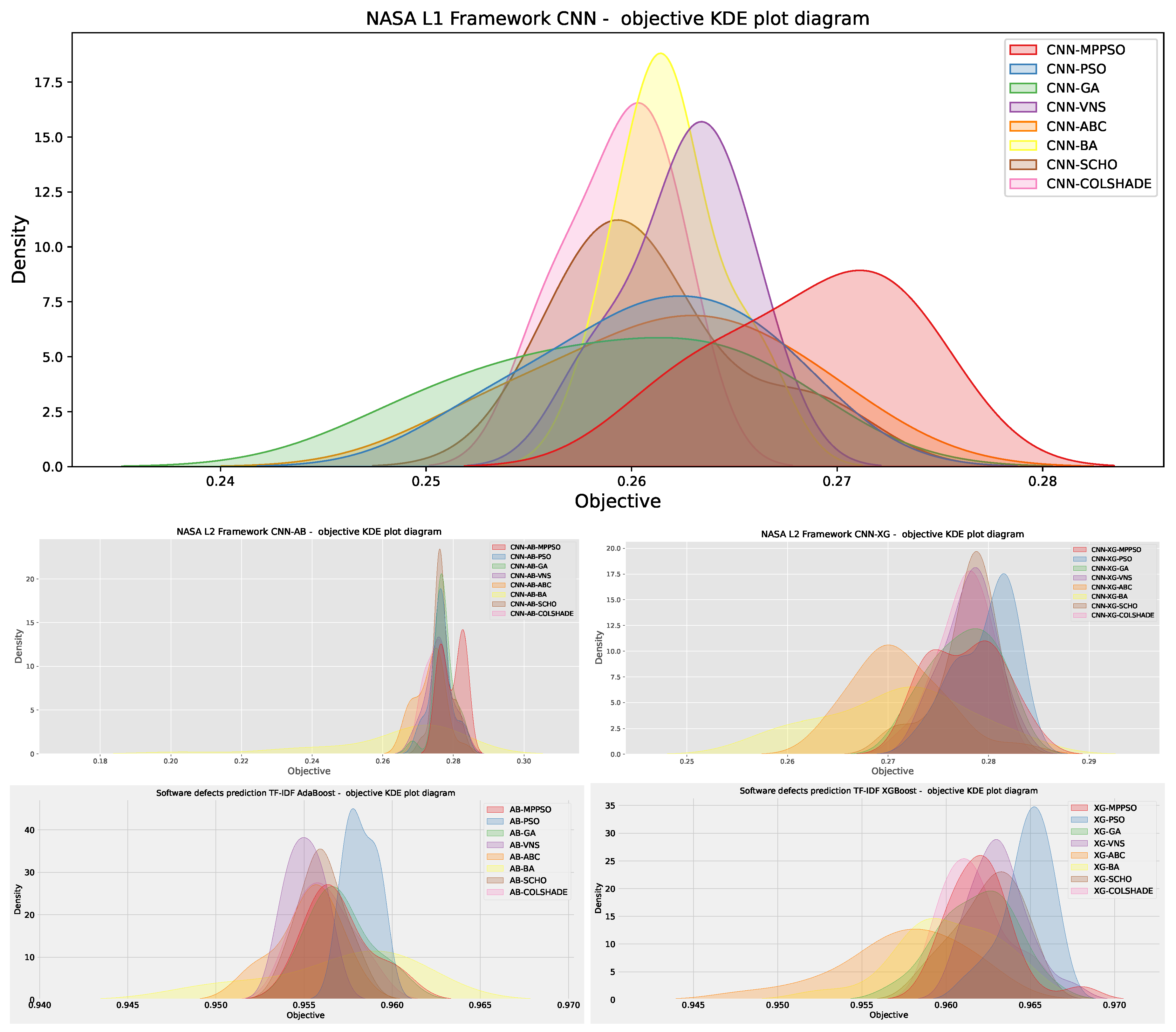

Figure 31.

KDE diagrams for all five conducted simulations.

Figure 31.

KDE diagrams for all five conducted simulations.

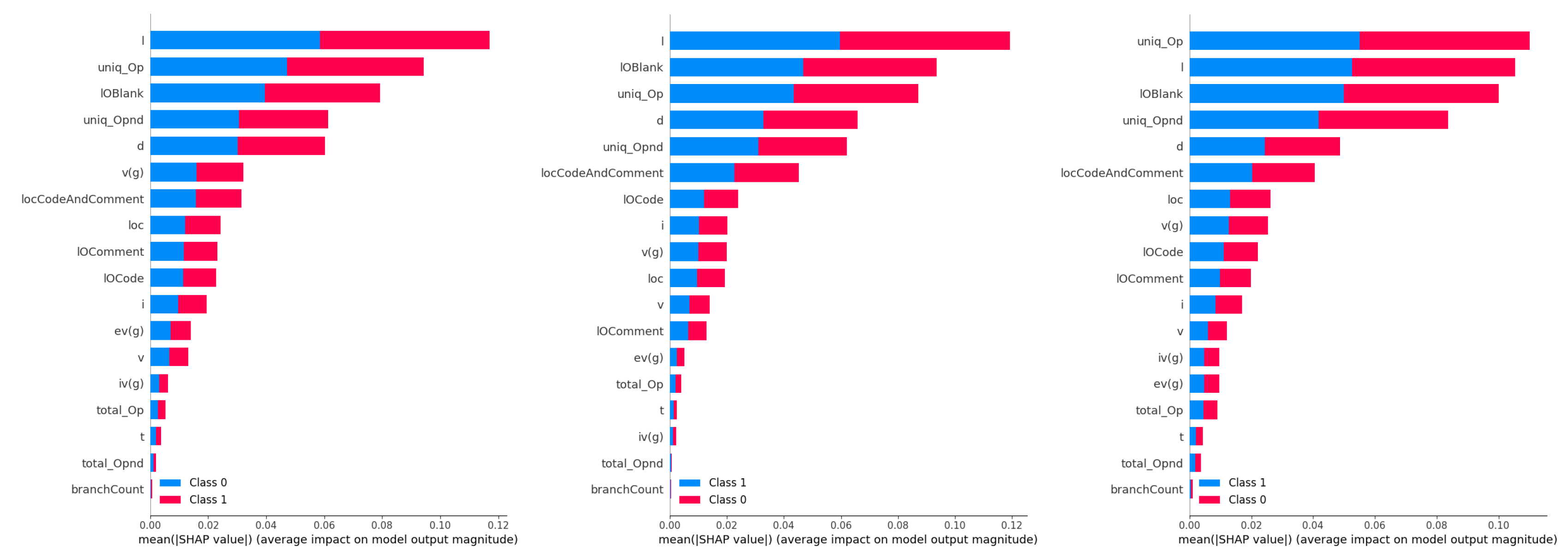

Figure 32.

Best CNN, XGBoost and AdaBoost model feature importances on NASA dataset.

Figure 32.

Best CNN, XGBoost and AdaBoost model feature importances on NASA dataset.

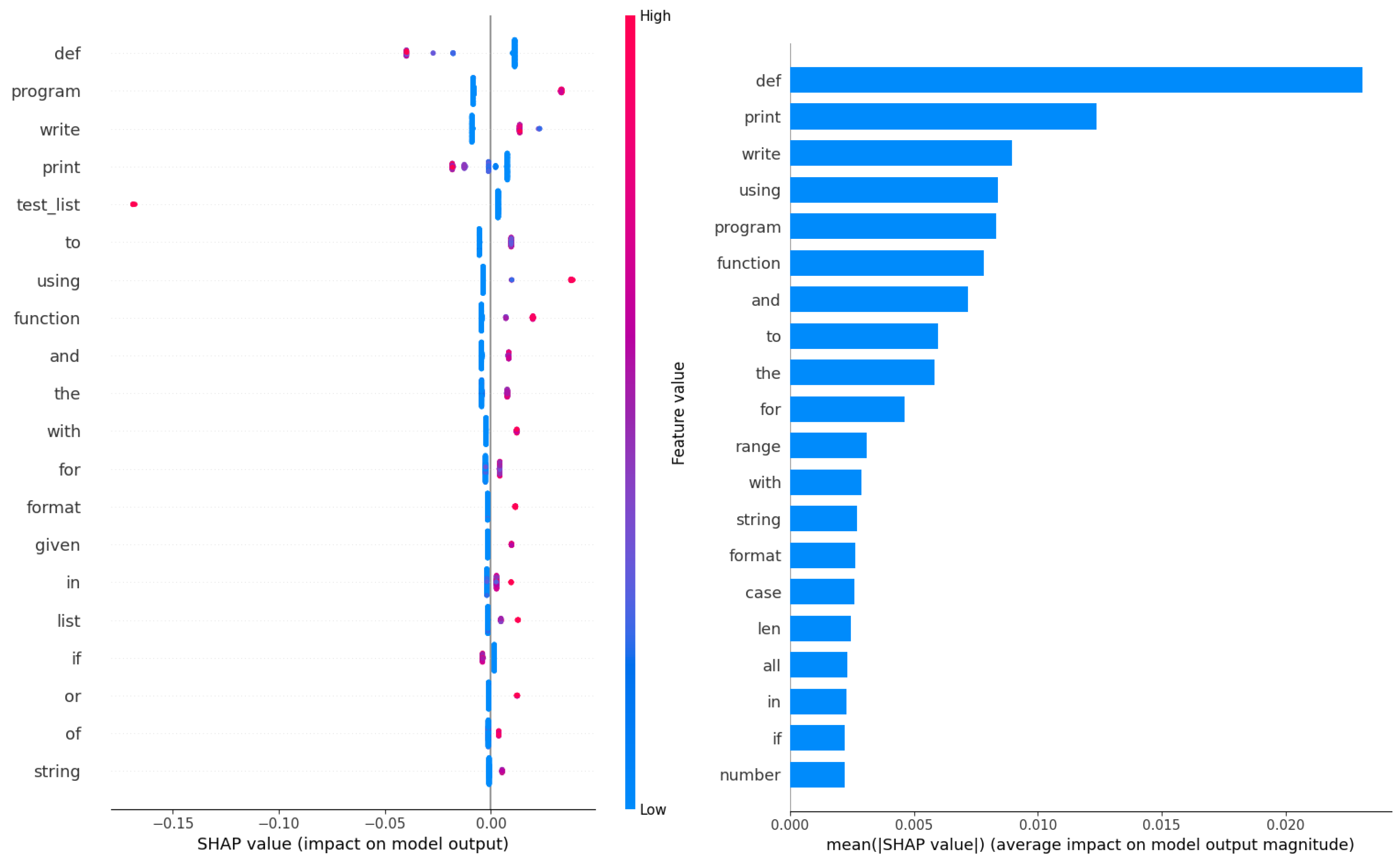

Figure 33.

Best AdaBoost model feature importances on NLP dataset.

Figure 33.

Best AdaBoost model feature importances on NLP dataset.

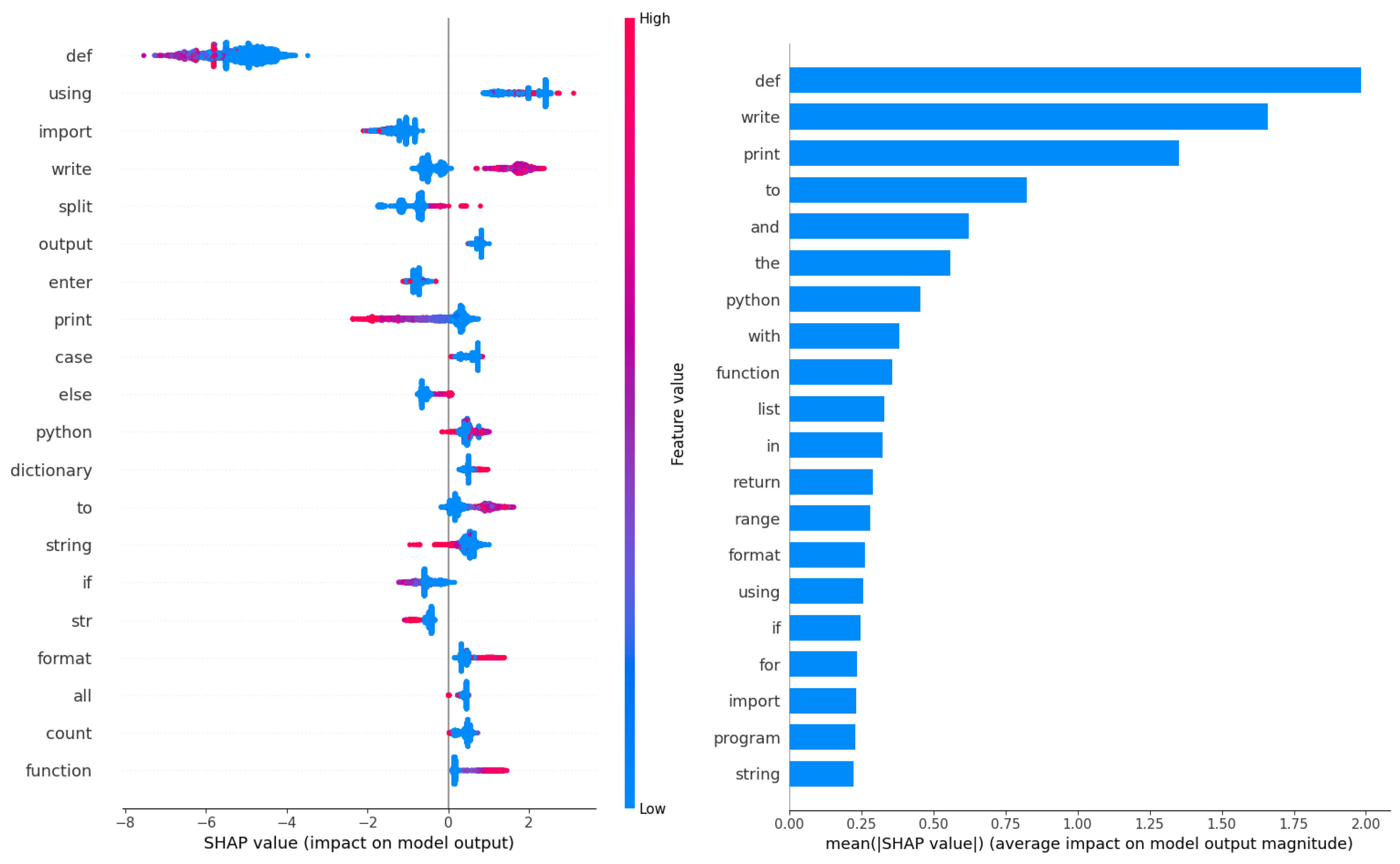

Figure 34.

Best XGBoost model feature importance’s on NLP dataset.

Figure 34.

Best XGBoost model feature importance’s on NLP dataset.

Table 1.

CNN parameter ranges subjected to optimization.

Table 1.

CNN parameter ranges subjected to optimization.

| Parameter |

Range |

| Learning Rate |

0.0001 - 0.0030 |

| Dropout |

0.05 - 0.5 |

| Epochs |

10 - 20 |

| Number of CNN Layers |

1 - 3 |

| Number of Dense Layers |

1 - 3 |

| Number of Neurons in layer |

32 - 128 |

Table 2.

AdaBoost parameter ranges subjected to optimization.

Table 2.

AdaBoost parameter ranges subjected to optimization.

| Parameter |

Range |

| Count of estimators |

|

| Depth |

|

| Learning rate |

|

Table 3.

XGBoost parameter ranges subjected to optimization.

Table 3.

XGBoost parameter ranges subjected to optimization.

| Parameter |

Range |

| Learning Rate |

0.1 - 0.9 |

| Minimum child weight |

1 - 10 |

| Subsample |

0.01 - 1.00 |

| Col sample by tree |

0.01 - 1.00 |

| Max depth |

3 - 10 |

| Gamma |

0.00 - 0.80 |

Table 4.

Layer 1 (CNN) objective function outcomes.

Table 4.

Layer 1 (CNN) objective function outcomes.

| Method |

Best |

Worst |

Mean |

Median |

Std |

Var |

| CNN-MPPSO |

0.273280 |

0.262061 |

0.268824 |

0.269873 |

0.004194 |

1.76E-05 |

| CNN-PSO |

0.267168 |

0.253372 |

0.261106 |

0.260917 |

0.004766 |

2.27E-05 |

| CNN-GA |

0.265933 |

0.249726 |

0.258941 |

0.258989 |

0.005977 |

3.57E-05 |

| CNN-VNS |

0.265920 |

0.258217 |

0.262605 |

0.263118 |

0.002553 |

6.52E-06 |

| CNN-ABC |

0.269294 |

0.253197 |

0.261761 |

0.262521 |

0.005419 |

2.94E-05 |

| CNN-BA |

0.265823 |

0.258906 |

0.261940 |

0.261646 |

0.002218 |

4.92E-06 |

| CNN-SCHO |

0.268643 |

0.257094 |

0.261124 |

0.259722 |

0.003986 |

1.59E-05 |

| CNN-COLSHADE |

0.262284 |

0.255697 |

0.259373 |

0.260087 |

0.002277 |

5.18E-06 |

Table 5.

Layer 1 (CNN) indicator function outcomes.

Table 5.

Layer 1 (CNN) indicator function outcomes.

| Method |

Best |

Worst |

Mean |

Median |

Std |

Var |

| CNN-MPPSO |

0.231201 |

0.238309 |

0.233446 |

0.232697 |

0.002810 |

7.89E-06 |

| CNN-PSO |

0.243172 |

0.267116 |

0.248784 |

0.243172 |

0.012645 |

1.60E-04 |

| CNN-GA |

0.232697 |

0.260756 |

0.252450 |

0.260756 |

0.015398 |

2.37E-04 |

| CNN-VNS |

0.236813 |

0.239805 |

0.237710 |

0.236813 |

0.005652 |

3.19E-05 |

| CNN-ABC |

0.242050 |

0.242798 |

0.244444 |

0.242050 |

0.007371 |

5.43E-05 |

| CNN-BA |

0.239431 |

0.230079 |

0.238608 |

0.237561 |

0.006460 |

4.17E-05 |

| CNN-SCHO |

0.244669 |

0.263749 |

0.249532 |

0.244669 |

0.009629 |

9.27E-05 |

| CNN-COLSHADE |

0.239057 |

0.244669 |

0.245866 |

0.244669 |

0.007860 |

6.18E-05 |

Table 6.

Best performing optimized CNN-MPPSO L1 model detailed metric comparisons.

Table 6.

Best performing optimized CNN-MPPSO L1 model detailed metric comparisons.

| Method |

metric |

no error |

error |

accuracy |

macro avg |

weighted avg |

| CNN- |

precision |

0.826009 |

0.480813 |

0.768799 |

0.653411 |

0.748395 |

| MPPSO |

recall |

0.888996 |

0.354409 |

0.768799 |

0.621703 |

0.768799 |

| |

f1-score |

0.856346 |

0.408046 |

0.768799 |

0.632196 |

0.755550 |

| CNN- |

precision |

0.829777 |

0.452611 |

0.756828 |

0.641194 |

0.744975 |

| PSO |

recall |

0.863417 |

0.389351 |

0.756828 |

0.626384 |

0.756828 |

| |

f1-score |

0.846263 |

0.418605 |

0.756828 |

0.632434 |

0.750108 |

| CNN- |

precision |

0.768653 |

0.188725 |

0.680135 |

0.478689 |

0.638262 |

| GA |

recall |

0.840251 |

0.128120 |

0.680135 |

0.484185 |

0.680135 |

| |

f1-score |

0.802859 |

0.152626 |

0.680135 |

0.477743 |

0.656660 |

| CNN- |

precision |

0.826304 |

0.465812 |

0.763187 |

0.646058 |

0.745250 |

| VNS |

recall |

0.879344 |

0.362729 |

0.763187 |

0.621036 |

0.763187 |

| |

f1-score |

0.851999 |

0.407858 |

0.763187 |

0.629928 |

0.752138 |

| CNN- |

precision |

0.830014 |

0.455253 |

0.757950 |

0.642633 |

0.745752 |

| ABC |

recall |

0.864865 |

0.389351 |

0.757950 |

0.627108 |

0.757950 |

| |

f1-score |

0.847081 |

0.419731 |

0.757950 |

0.633406 |

0.750995 |

| CNN- |

precision |

0.827539 |

0.459959 |

0.760569 |

0.643749 |

0.744892 |

| BA |

recall |

0.873069 |

0.372712 |

0.760569 |

0.622891 |

0.760569 |

| |

f1-score |

0.849695 |

0.411765 |

0.760569 |

0.630730 |

0.751230 |

| CNN- |

precision |

0.830999 |

0.450094 |

0.755331 |

0.640547 |

0.745356 |

| SCHO |

recall |

0.859073 |

0.397671 |

0.755331 |

0.628372 |

0.755331 |

| |

f1-score |

0.844803 |

0.422261 |

0.755331 |

0.633532 |

0.749798 |

| CNN- |

precision |

0.826127 |

0.460084 |

0.760943 |

0.643105 |

0.743825 |

| COLSHADE |

recall |

0.875965 |

0.364393 |

0.760943 |

0.620179 |

0.760943 |

| |

f1-score |

0.850316 |

0.406685 |

0.760943 |

0.628501 |

0.750570 |

| |

support |

2072 |

601 |

|

|

|

Table 7.

Optimized CNN model parameter selections.

Table 7.

Optimized CNN model parameter selections.

| Method |

Learning |

Dropout |

Epochs |

Layers |

Layers |

Neurons |

Neurons |

| |

Rate |

|

|

CNN |

Dense |

CNN |

Dense |

| CNN-MPPSO |

2.44E-03 |

0.500000 |

84 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

88 |

88 |

| CNN-PSO |

2.80E-03 |

0.165591 |

56 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

97 |

83 |

| CNN-GA |

1.66E-03 |

0.475371 |

65 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

94 |

86 |

| CNN-VNS |

2.38E-03 |

0.500000 |

42 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

128 |

93 |

| CNN-ABC |

2.61E-03 |

0.370234 |

93 |

2.0 |

1.0 |

124 |

96 |

| CNN-BA |

3.00E-03 |

0.500000 |

70 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

108 |

103 |

| CNN-SCHO |

1.25E-03 |

0.197273 |

100 |

1.0 |

2.0 |

46 |

105 |

| CNN-COLSHADE |

1.88E-03 |

0.230465 |

86 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

73 |

99 |

Table 8.

Layer 2 AdaBoost objective function outcomes.

Table 8.

Layer 2 AdaBoost objective function outcomes.

| Method |

Best |

Worst |

Mean |

Median |

Std |

Var |

| CNN-AB-MPPSO |

0.282906 |

0.276185 |

0.279771 |

0.280600 |

0.003092 |

9.56E-06 |

| CNN-AB-PSO |

0.282906 |

0.270598 |

0.276496 |

0.276185 |

0.003085 |

9.51E-06 |

| CNN-AB-GA |

0.282906 |

0.268442 |

0.277295 |

0.276351 |

0.002980 |

8.88E-06 |

| CNN-AB-VNS |

0.282906 |

0.269109 |

0.276079 |

0.276185 |

0.003662 |

1.34E-05 |

| CNN-AB-ABC |

0.282906 |

0.266412 |

0.273352 |

0.274076 |

0.004034 |

1.63E-05 |

| CNN-AB-BA |

0.276185 |

0.202141 |

0.262977 |

0.271189 |

0.019258 |

3.71E-04 |

| CNN-AB-SCHO |

0.282906 |

0.271101 |

0.276876 |

0.276185 |

0.002530 |

6.40E-06 |

| CNN-AB-COLSHADE |

0.282906 |

0.270156 |

0.275568 |

0.276185 |

0.003515 |

1.24E-05 |

Table 9.

Layer 2 AdaBoost objective function outcomes.

Table 9.

Layer 2 AdaBoost objective function outcomes.

| Method |

Best |

Worst |

Mean |

Median |

Std |

Var |

| CNN-AB-MPPSO |

0.227834 |

0.233820 |

0.230453 |

0.230079 |

0.002661 |

7.08E-06 |

| CNN-AB-PSO |

0.227834 |

0.228208 |

0.231481 |

0.230827 |

0.002380 |

5.67E-06 |

| CNN-AB-GA |

0.227834 |

0.242050 |

0.231874 |

0.232323 |

0.003529 |

1.25E-05 |

| CNN-AB-VNS |

0.227834 |

0.239057 |

0.232080 |

0.230827 |

0.003587 |

1.29E-05 |

| CNN-AB-ABC |

0.227834 |

0.235316 |

0.234287 |

0.233820 |

0.003431 |

1.18E-05 |

| CNN-AB-BA |

0.233820 |

0.249158 |

0.244239 |

0.235690 |

0.020533 |

4.22E-04 |

| CNN-AB-SCHO |

0.227834 |

0.233446 |

0.231257 |

0.230640 |

0.002208 |

4.87E-06 |

| CNN-AB-COLSHADE |

0.227834 |

0.236813 |

0.232641 |

0.233071 |

0.002865 |

8.21E-06 |

Table 10.

Best performing optimized Layer 2 AdaBoost model detailed metric comparisons.

Table 10.

Best performing optimized Layer 2 AdaBoost model detailed metric comparisons.

| Method |

metric |

no error |

error |

accuracy |

macro avg |

weighted avg |

| CNN-AB- |

precision |

0.827586 |

0.490909 |

0.772166 |

0.659248 |

0.751887 |

| MPPSO |

recall |

0.891892 |

0.359401 |

0.772166 |

0.625646 |

0.772166 |

| |

f1-score |

0.858537 |

0.414986 |

0.772166 |

0.636761 |

0.758808 |

| CNN-AB- |

precision |

0.827586 |

0.490909 |

0.772166 |

0.659248 |

0.751887 |

| PSO |

recall |

0.891892 |

0.359401 |

0.772166 |

0.625646 |

0.772166 |

| |

f1-score |

0.858537 |

0.414986 |

0.772166 |

0.636761 |

0.758808 |

| CNN-AB- |

precision |

0.827586 |

0.490909 |

0.772166 |

0.659248 |

0.751887 |

| GA |

recall |

0.891892 |

0.359401 |

0.772166 |

0.625646 |

0.772166 |

| |

f1-score |

0.858537 |

0.414986 |

0.772166 |

0.636761 |

0.758808 |

| CNN-AB- |

precision |

0.827586 |

0.490909 |

0.772166 |

0.659248 |

0.751887 |

| VNS |

recall |

0.891892 |

0.359401 |

0.772166 |

0.625646 |

0.772166 |

| |

f1-score |

0.858537 |

0.414986 |

0.772166 |

0.636761 |

0.758808 |

| CNN-AB- |

precision |

0.827586 |

0.490909 |

0.772166 |

0.659248 |

0.751887 |

| ABC |

recall |

0.891892 |

0.359401 |

0.772166 |

0.625646 |

0.772166 |

| |

f1-score |

0.858537 |

0.414986 |

0.772166 |

0.636761 |

0.758808 |

| CNN-AB- |

precision |

0.828416 |

0.474468 |

0.766180 |

0.651442 |

0.748834 |

| BA |

recall |

0.880792 |

0.371048 |

0.766180 |

0.625920 |

0.766180 |

| |

f1-score |

0.853801 |

0.416433 |

0.766180 |

0.635117 |

0.755463 |

| CNN-AB- |

precision |

0.827586 |

0.490909 |

0.772166 |

0.659248 |

0.751887 |

| SCHO |

recall |

0.891892 |

0.359401 |

0.772166 |

0.625646 |

0.772166 |

| |

f1-score |

0.858537 |

0.414986 |

0.772166 |

0.636761 |

0.758808 |

| CNN-AB- |

precision |

0.827586 |

0.490909 |

0.772166 |

0.659248 |

0.751887 |

| COLSHADE |

recall |

0.891892 |

0.359401 |

0.772166 |

0.625646 |

0.772166 |

| |

f1-score |

0.858537 |

0.414986 |

0.772166 |

0.636761 |

0.758808 |

| |

support |

2072 |

601 |

|

|

|

Table 11.

Layer 2 AdaBoost model parameter selections.

Table 11.

Layer 2 AdaBoost model parameter selections.

| Methods |

Number of estimators |

Depth |

Learning rate |

| CNN-AB-MPPSO |

17 |

1 |

0.388263 |

| CNN-AB-PSO |

17 |

1 |

0.395194 |

| CNN-AB-GA |

18 |

1 |

0.385504 |

| CNN-AB-VNS |

16 |

1 |

0.393270 |

| CNN-AB-ABC |

17 |

1 |

0.386973 |

| CNN-AB-BA |

37 |

2 |

0.100000 |

| CNN-AB-SCHO |

17 |

1 |

0.397827 |

| CNN-AB-COLSHADE |

16 |

1 |

0.389986 |

Table 12.

Layer 2 XGBoost objective function outcomes.

Table 12.

Layer 2 XGBoost objective function outcomes.

| Method |

Best |

Worst |

Mean |

Median |

Std |

Var |

| CNN-XG-MPPSO |

0.283956 |

0.272256 |

0.277731 |

0.278157 |

0.003454 |

1.19E-05 |

| CNN-XG-PSO |

0.283057 |

0.273192 |

0.279641 |

0.280789 |

0.002805 |

7.87E-06 |

| CNN-XG-GA |

0.282818 |

0.271330 |

0.277524 |

0.277793 |

0.003237 |

1.05E-05 |

| CNN-XG-VNS |

0.282944 |

0.272961 |

0.278091 |

0.278468 |

0.002479 |

6.14E-06 |

| CNN-XG-ABC |

0.282813 |

0.264134 |

0.271095 |

0.269931 |

0.004398 |

1.93E-05 |

| CNN-XG-BA |

0.282907 |

0.258011 |

0.270776 |

0.271714 |

0.006936 |

4.81E-05 |

| CNN-XG-SCHO |

0.281937 |

0.270017 |

0.277780 |

0.278442 |

0.002853 |

8.14E-06 |

| CNN-XG-COLSHADE |

0.281011 |

0.271270 |

0.277472 |

0.278075 |

0.002513 |

6.32E-06 |

Table 13.

Layer 2 XGBoost objective function outcomes.

Table 13.

Layer 2 XGBoost objective function outcomes.

| Method |

Best |

Worst |

Mean |

Median |

Std |

Var |

| CNN-XG-MPPSO |

0.228956 |

0.232697 |

0.232043 |

0.232510 |

0.003383 |

1.14E-05 |

| CNN-XG-PSO |

0.233820 |

0.234194 |

0.233876 |

0.233633 |

0.002654 |

7.04E-06 |

| CNN-XG-GA |

0.228582 |

0.234194 |

0.232772 |

0.232884 |

0.003501 |

1.23E-05 |

| CNN-XG-VNS |

0.225589 |

0.235316 |

0.232866 |

0.232697 |

0.004007 |

1.61E-05 |

| CNN-XG-ABC |

0.239805 |

0.243172 |

0.240591 |

0.239993 |

0.004909 |

2.41E-05 |

| CNN-XG-BA |

0.231949 |

0.245043 |

0.239263 |

0.237000 |

0.007681 |

5.90E-05 |

| CNN-XG-SCHO |

0.233446 |

0.240928 |

0.232941 |

0.231575 |

0.005156 |

2.66E-05 |

| CNN-XG-COLSHADE |

0.227086 |

0.226712 |

0.233651 |

0.234007 |

0.004904 |

2.41E-05 |

Table 14.

Best performing optimized Layer 2 XGBoost model detailed metric comparisons.

Table 14.

Best performing optimized Layer 2 XGBoost model detailed metric comparisons.

| Method |

metric |

no error |

error |

accuracy |

macro avg |

weighted avg |

| CNN-XG- |

precision |

0.830018 |

0.488069 |

0.771044 |

0.659044 |

0.753134 |

| MPPSO |

recall |

0.886100 |

0.374376 |

0.771044 |

0.630238 |

0.771044 |

| |

f1-score |

0.857143 |

0.423729 |

0.771044 |

0.640436 |

0.759694 |

| CNN-XG- |

precision |

0.831729 |

0.475610 |

0.766180 |

0.653669 |

0.751658 |

| PSO |

recall |

0.875483 |

0.389351 |

0.766180 |

0.632417 |

0.766180 |

| |

f1-score |

0.853045 |

0.428179 |

0.766180 |

0.640612 |

0.757518 |

| CNN-XG- |

precision |

0.829499 |

0.489035 |

0.771418 |

0.659267 |

0.752949 |

| GA |

recall |

0.887548 |

0.371048 |

0.771418 |

0.629298 |

0.771418 |

| |

f1-score |

0.857543 |

0.421949 |

0.771418 |

0.639746 |

0.759603 |

| CNN-XG- |

precision |

0.828342 |

0.497706 |

0.774411 |

0.663024 |

0.754001 |

| VNS |

recall |

0.894305 |

0.361065 |

0.774411 |

0.627685 |

0.774411 |

| |

f1-score |

0.860060 |

0.418515 |

0.774411 |

0.639288 |

0.760783 |

| CNN-XG- |

precision |

0.772056 |

0.209091 |

0.679386 |

0.490573 |

0.645478 |

| ABC |

recall |

0.832046 |

0.153078 |

0.679386 |

0.492562 |

0.679386 |

| |

f1-score |

0.800929 |

0.176753 |

0.679386 |

0.488841 |

0.660589 |

| CNN-XG- |

precision |

0.830902 |

0.480167 |

0.768051 |

0.655535 |

0.752043 |

| BA |

recall |

0.879826 |

0.382696 |

0.768051 |

0.631261 |

0.768051 |

| |

f1-score |

0.854665 |

0.425926 |

0.768051 |

0.640295 |

0.758267 |

| CNN-XG- |

precision |

0.831199 |

0.476386 |

0.766554 |

0.653792 |

0.751422 |

| SCHO |

recall |

0.876931 |

0.386023 |

0.766554 |

0.631477 |

0.766554 |

| |

f1-score |

0.853452 |

0.426471 |

0.766554 |

0.639961 |

0.757449 |

| CNN-XG- |

precision |

0.828328 |

0.493213 |

0.772914 |

0.660770 |

0.752980 |

| COLSHADE |

recall |

0.891892 |

0.362729 |

0.772914 |

0.627310 |

0.772914 |

| |

f1-score |

0.858936 |

0.418025 |

0.772914 |

0.638480 |

0.759801 |

| |

support |

2072 |

601 |

|

|

|

Table 15.

Layer 2 XGBoost model parameter selections.

Table 15.

Layer 2 XGBoost model parameter selections.

| Method |

Learning Rate |

max_child_weight |

subsample |

collsample_bytree |

max_depth |

gamma |

| CNN-XG-MPPSO |

0.100000 |

10.000000 |

0.983197 |

0.293945 |

3 |

0.713646 |

| CNN-XG-PSO |

0.100000 |

2.357106 |

0.968264 |

0.363649 |

5 |

0.015409 |

| CNN-XG-GA |

0.107403 |

1.691592 |

0.950345 |

0.319984 |

3 |

0.000000 |

| CNN-XG-VNS |

0.175166 |

4.645308 |

1.000000 |

0.284932 |

4 |

0.757203 |

| CNN-XG-ABC |

0.285948 |

6.211737 |

0.744753 |

0.678273 |

6 |

0.779172 |

| CNN-XG-BA |

0.206396 |

3.716090 |

1.000000 |

0.322232 |

4 |

0.528585 |

| CNN-XG-SCHO |

0.100000 |

3.353770 |

1.000000 |

0.269461 |

3 |

0.000000 |

| CNN-XG-COLSHADE |

0.100000 |

2.409330 |

0.989736 |

0.306208 |

3 |

0.050836 |

Table 16.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost objective function outcomes.

Table 16.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost objective function outcomes.

| Method |

Best |

Worst |

Mean |

Median |

Std |

Var |

| AB-MPPSO |

0.959947 |

0.955168 |

0.956996 |

0.956397 |

0.001601 |

2.56E-06 |

| AB-PSO |

0.959207 |

0.957205 |

0.958233 |

0.957872 |

0.000780 |

6.08E-07 |

| AB-GA |

0.959780 |

0.955059 |

0.957057 |

0.957037 |

0.001547 |

2.39E-06 |

| AB-VNS |

0.956367 |

0.953758 |

0.955049 |

0.955026 |

0.000913 |

8.34E-07 |

| AB-ABC |

0.957133 |

0.952387 |

0.955170 |

0.955638 |

0.001554 |

2.42E-06 |

| AB-BA |

0.959947 |

0.950244 |

0.956981 |

0.959207 |

0.003716 |

1.38E-05 |

| AB-SCHO |

0.957769 |

0.954325 |

0.955999 |

0.955834 |

0.001109 |

1.23E-06 |

| AB-COLSHADE |

0.958470 |

0.954542 |

0.956181 |

0.956367 |

0.001371 |

1.88E-06 |

Table 17.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost indicator function outcomes.

Table 17.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost indicator function outcomes.

| Method |

Best |

Worst |

Mean |

Median |

Std |

Var |

| AB-MPPSO |

0.020219 |

0.022618 |

0.021659 |

0.021933 |

0.000793 |

6.29E-07 |

| AB-PSO |

0.020562 |

0.021590 |

0.021042 |

0.021247 |

0.000411 |

1.69E-07 |

| AB-GA |

0.020219 |

0.022618 |

0.021590 |

0.021590 |

0.000781 |

6.11E-07 |

| AB-VNS |

0.021933 |

0.023304 |

0.022618 |

0.022618 |

0.000485 |

2.35E-07 |

| AB-ABC |

0.021590 |

0.023989 |

0.022550 |

0.022276 |

0.000793 |

6.29E-07 |

| AB-BA |

0.020219 |

0.025017 |

0.021659 |

0.020562 |

0.001844 |

3.40E-06 |

| AB-SCHO |

0.021247 |

0.022961 |

0.022138 |

0.022276 |

0.000557 |

3.10E-07 |

| AB-COLSHADE |

0.020905 |

0.022961 |

0.022070 |

0.021933 |

0.000706 |

4.98E-07 |

Table 18.

Best performing optimized NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost model detailed metric comparisons.

Table 18.

Best performing optimized NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost model detailed metric comparisons.

| Method |

metric |

no error |

error |

accuracy |

macro avg |

weighted avg |

| AB-MPPSO |

precision |

0.993776 |

0.966033 |

0.979781 |

0.979904 |

0.980170 |

| |

recall |

0.966375 |

0.993711 |

0.979781 |

0.980043 |

0.979781 |

| |

f1-score |

0.979884 |

0.979676 |

0.979781 |

0.979780 |

0.979782 |

| AB-PSO |

precision |

0.992409 |

0.966644 |

0.979438 |

0.979526 |

0.979773 |

| |

recall |

0.967048 |

0.992313 |

0.979438 |

0.979680 |

0.979438 |

| |

f1-score |

0.979564 |

0.979310 |

0.979438 |

0.979437 |

0.979440 |

| AB-GA |

precision |

0.990385 |

0.969220 |

0.979781 |

0.979802 |

0.980006 |

| |

recall |

0.969738 |

0.990217 |

0.979781 |

0.979977 |

0.979781 |

| |

f1-score |

0.979952 |

0.979606 |

0.979781 |

0.979779 |

0.979783 |

| AB-VNS |

precision |

0.989003 |

0.967191 |

0.978067 |

0.978097 |

0.978306 |

| |

recall |

0.967720 |

0.988819 |

0.978067 |

0.978270 |

0.978067 |

| |

f1-score |

0.978246 |

0.977885 |

0.978067 |

0.978066 |

0.978069 |

| AB-ABC |

precision |

0.991034 |

0.965940 |

0.978410 |

0.978487 |

0.978728 |

| |

recall |

0.966375 |

0.990915 |

0.978410 |

0.978645 |

0.978410 |

| |

f1-score |

0.978550 |

0.978268 |

0.978410 |

0.978409 |

0.978412 |

| AB-BA |

precision |

0.993776 |

0.966033 |

0.979781 |

0.979904 |

0.980170 |

| |

recall |

0.966375 |

0.993711 |

0.979781 |

0.980043 |

0.979781 |

| |

f1-score |

0.979884 |

0.979676 |

0.979781 |

0.979780 |

0.979782 |

| AB-SCHO |

precision |

0.990365 |

0.967235 |

0.978753 |

0.978800 |

0.979022 |

| |

recall |

0.967720 |

0.990217 |

0.978753 |

0.978968 |

0.978753 |

| |

f1-score |

0.978912 |

0.978591 |

0.978753 |

0.978751 |

0.978754 |

| AB-COLSHADE |

precision |

0.991047 |

0.967258 |

0.979095 |

0.979152 |

0.979381 |

| |

recall |

0.967720 |

0.990915 |

0.979095 |

0.979318 |

0.979095 |

| |

f1-score |

0.979245 |

0.978944 |

0.979095 |

0.979094 |

0.979097 |

| |

support |

1487 |

1431 |

|

|

|

Table 19.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost model parameter selections.

Table 19.

NLP Layer 2 AdaBoost model parameter selections.

| Methods |

Number of estimators |

Depth |

Learning rate |

| AB-MPPSO |

15 |

5 |

1.425870 |

| AB-PSO |

15 |

6 |

1.806671 |

| AB-GA |

14 |

6 |

1.657350 |

| AB-VNS |

15 |

6 |

1.357072 |

| AB-ABC |

14 |

6 |

1.761995 |

| AB-BA |

15 |

6 |

1.808268 |

| AB-SCHO |

14 |

6 |

1.669562 |

| AB-COLSHADE |

13 |

6 |

1.464666 |

Table 20.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost objective function outcomes.

Table 20.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost objective function outcomes.

| Method |

Best |

Worst |

Mean |

Median |

Std |

Var |

| XG-MPPSO |

0.968036 |

0.959172 |

0.962128 |

0.961967 |

0.001908 |

3.64E-06 |

| XG-PSO |

0.966730 |

0.961151 |

0.964797 |

0.965050 |

0.001395 |

1.95E-06 |

| XG-GA |

0.966098 |

0.957067 |

0.961848 |

0.962024 |

0.002147 |

4.61E-06 |

| XG-VNS |

0.967399 |

0.960652 |

0.963171 |

0.963222 |

0.001609 |

2.59E-06 |

| XG-ABC |

0.962689 |

0.948075 |

0.957429 |

0.957948 |

0.003626 |

1.31E-05 |

| XG-BA |

0.964691 |

0.952595 |

0.960146 |

0.959524 |

0.002959 |

8.76E-06 |

| XG-SCHO |

0.965394 |

0.958438 |

0.962483 |

0.962671 |

0.001889 |

3.57E-06 |

| XG-COLSHADE |

0.965394 |

0.959140 |

0.961709 |

0.961590 |

0.001811 |

3.28E-06 |

Table 21.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost indicator function outcomes.

Table 21.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost indicator function outcomes.

| Method |

Best |

Worst |

Mean |

Median |

Std |

Var |

| XG-MPPSO |

0.016107 |

0.020562 |

0.019106 |

0.019191 |

0.000969 |

| XG-PSO |

0.016792 |

0.019534 |

0.017752 |

0.017649 |

0.000699 |

| XG-GA |

0.017135 |

0.021590 |

0.019243 |

0.019191 |

0.001074 |

| XG-VNS |

0.016450 |

0.019877 |

0.018574 |

0.018506 |

0.000815 |

| XG-ABC |

0.018849 |

0.026388 |

0.021470

|

0.021247 |

0.001856 |

| XG-BA |

0.017820 |

0.023989 |

0.020099 |

0.020391 |

0.001503 |

| XG-SCHO |

0.017478 |

0.020905 |

0.018934 |

0.018849 |

0.000950 |

| XG-COLSHADE |

0.017478 |

0.020562 |

0.019311 |

0.019363 |

0.000921 |

Table 22.

Best performing optimized NLP Layer 2 XGBoost model detailed metric comparisons.

Table 22.

Best performing optimized NLP Layer 2 XGBoost model detailed metric comparisons.

| Method |

metric |

no error |

error |

accuracy |

macro avg |

weighted avg |

| XG-MPPSO |

precision |

0.995186 |

0.972678 |

0.983893 |

0.983932 |

0.984148 |

| |

recall |

0.973100 |

0.995108 |

0.983893 |

0.984104 |

0.983893 |

| |

f1-score |

0.984019 |

0.983765 |

0.983893 |

0.983892 |

0.983895 |

| XG-PSO |

precision |

0.995862 |

0.970708 |

0.983208 |

0.983285 |

0.983527 |

| |

recall |

0.971083 |

0.995807 |

0.983208 |

0.983445 |

0.983208 |

| |

f1-score |

0.983316 |

0.983098 |

0.983208 |

0.983207 |

0.983209 |

| XG-GA |

precision |

0.996545 |

0.969409 |

0.982865 |

0.982977 |

0.983237 |

| |

recall |

0.969738 |

0.996506 |

0.982865 |

0.983122 |

0.982865 |

| |

f1-score |

0.982958 |

0.982771 |

0.982865 |

0.982864 |

0.982866 |

| XG-VNS |

precision |

0.995865 |

0.971370 |

0.983550 |

0.983618 |

0.983853 |

| |

recall |

0.971755 |

0.995807 |

0.983550 |

0.983781 |

0.983550 |

| |

f1-score |

0.983662 |

0.983437 |

0.983550 |

0.983550 |

0.983552 |

| XG-ABC |

precision |

0.995159 |

0.967391 |

0.981151 |

0.981275 |

0.981542 |

| |

recall |

0.967720 |

0.995108 |

0.981151 |

0.981414 |

0.981151 |

| |

f1-score |

0.981248 |

0.981054 |

0.981151 |

0.981151 |

0.981153 |

| XG-BA |

precision |

0.995169 |

0.969367 |

0.982180 |

0.982268 |

0.982516 |

| |

recall |

0.969738 |

0.995108 |

0.982180 |

0.982423 |

0.982180 |

| |

f1-score |

0.982289 |

0.982069 |

0.982180 |

0.982179 |

0.982181 |

| XG-SCHO |

precision |

0.995856 |

0.969388 |

0.982522 |

0.982622 |

0.982876 |

| |

recall |

0.969738 |

0.995807 |

0.982522 |

0.982772 |

0.982522 |

| |

f1-score |

0.982624 |

0.982420 |

0.982522 |

0.982522 |

0.982524 |

| XG-COLSHADE |

precision |

0.995856 |

0.969388 |

0.982522 |

0.982622 |

0.982876 |

| |

recall |

0.969738 |

0.995807 |

0.982522 |

0.982772 |

0.982522 |

| |

f1-score |

0.982624 |

0.982420 |

0.982522 |

0.982522 |

0.982524 |

| |

support |

1487 |

1431 |

|

|

|

Table 23.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost model parameter selections.

Table 23.

NLP Layer 2 XGBoost model parameter selections.

| Method |

Learning Rate |

max_child_weight |

subsample |

collsample_bytree |

max_depth |

gamma |

| XG-MPPSO |

0.878864 |

1.000000 |

0.886550 |

0.447144 |

10 |

0.001162 |

| XG-PSO |

0.900000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.418138 |

10 |

0.137715 |

| XG-GA |

0.900000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.380366 |

10 |

0.000000 |

| XG-VNS |

0.874556 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.389317 |

10 |

0.800000 |

| XG-ABC |

0.900000 |

1.000000 |

0.920135 |

0.412610 |

7 |

0.512952 |

| XG-BA |

0.900000 |

1.191561 |

1.000000 |

0.451404 |

10 |

0.800000 |

| XG-SCHO |

0.900000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.425699 |

10 |

0.161777 |

| XG-COLSHADE |

0.900000 |

1.000000 |

1.000000 |

0.369307 |

10 |

0.262928 |

Table 24.

Shapiro-Wilk outcomes of the five conducted simulations for verification of the normality condition for safe utilization of parametric tests.

Table 24.

Shapiro-Wilk outcomes of the five conducted simulations for verification of the normality condition for safe utilization of parametric tests.

| Model |

MPPSO |

PSO |

GA |

VNS |

ABC |

BA |

SCHO |

COLSHADE |

| CNN Optimization |

0.033 |

0.029 |

0.023 |

0.017 |

0.035 |

0.044 |

0.041 |

0.037 |

| AdaBoost Optimization |

0.019 |

0.027 |

0.038 |

0.021 |

0.034 |

0.043 |

0.025 |

0.049 |

| XGBoost Optimization |

0.022 |

0.026 |

0.032 |

0.018 |

0.029 |

0.040 |

0.038 |

0.042 |

| AdaBoost NLP Optimization |

0.031 |

0.022 |

0.037 |

0.026 |

0.033 |

0.046 |

0.030 |

0.045 |

| XGBoost NLP Optimization |

0.028 |

0.024 |

0.034 |

0.019 |

0.031 |

0.041 |

0.036 |

0.043 |

Table 25.

Wilcoxon signed-rank test scores of the five conducted simulations.

Table 25.

Wilcoxon signed-rank test scores of the five conducted simulations.

| MPPSO vs. others |

PSO |

GA |

VNS |

ABC |

BA |

SCHO |

COLSHADE |

| CNN Optimization |

0.027 |

0.024 |

0.034 |

0.018 |

0.032 |

0.040 |

0.045 |

| AdaBoost Optimization |

0.020 |

0.028 |

0.031 |

0.022 |

0.030 |

0.038 |

0.042 |

| XGBoost Optimization |

0.033 |

0.023 |

0.037 |

0.019 |

0.031 |

0.043 |

0.046 |

| AdaBoost NLP Optimization |

0.029 |

0.026 |

0.035 |

0.021 |

0.029 |

0.041 |

0.044 |

| XGBoost NLP Optimization |

0.024 |

0.027 |

0.032 |

0.020 |

0.034 |

0.039 |

0.047 |