Submitted:

26 August 2024

Posted:

28 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

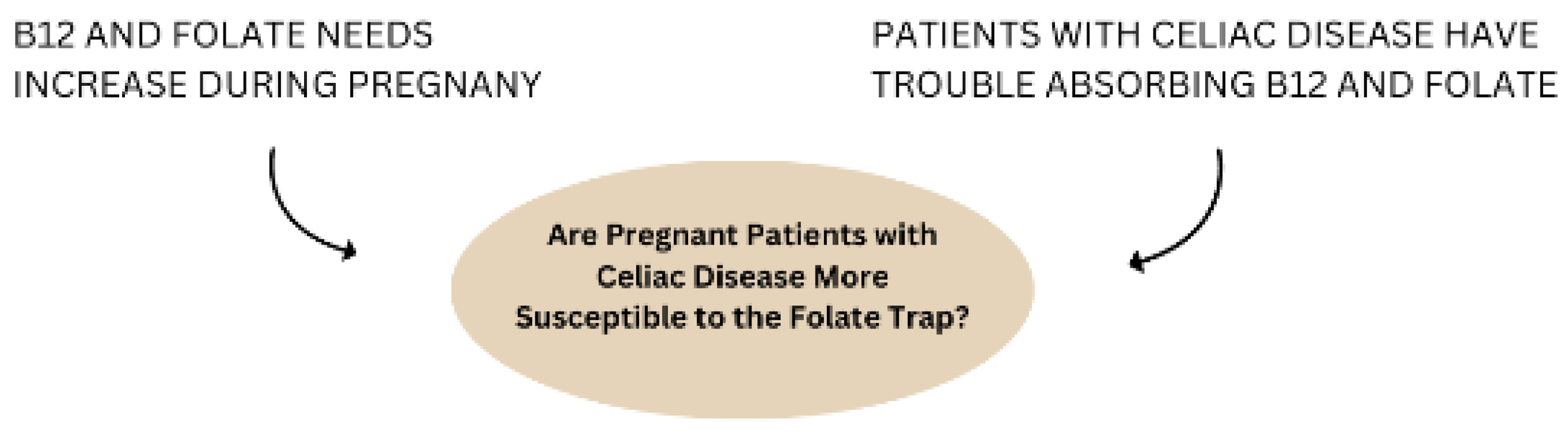

1. Introduction

2. Folate and Vitamin B12 Requirements and Prevalence of Deficiency

3. Diagnosis of Folate and Vitamin B12 Deficiency

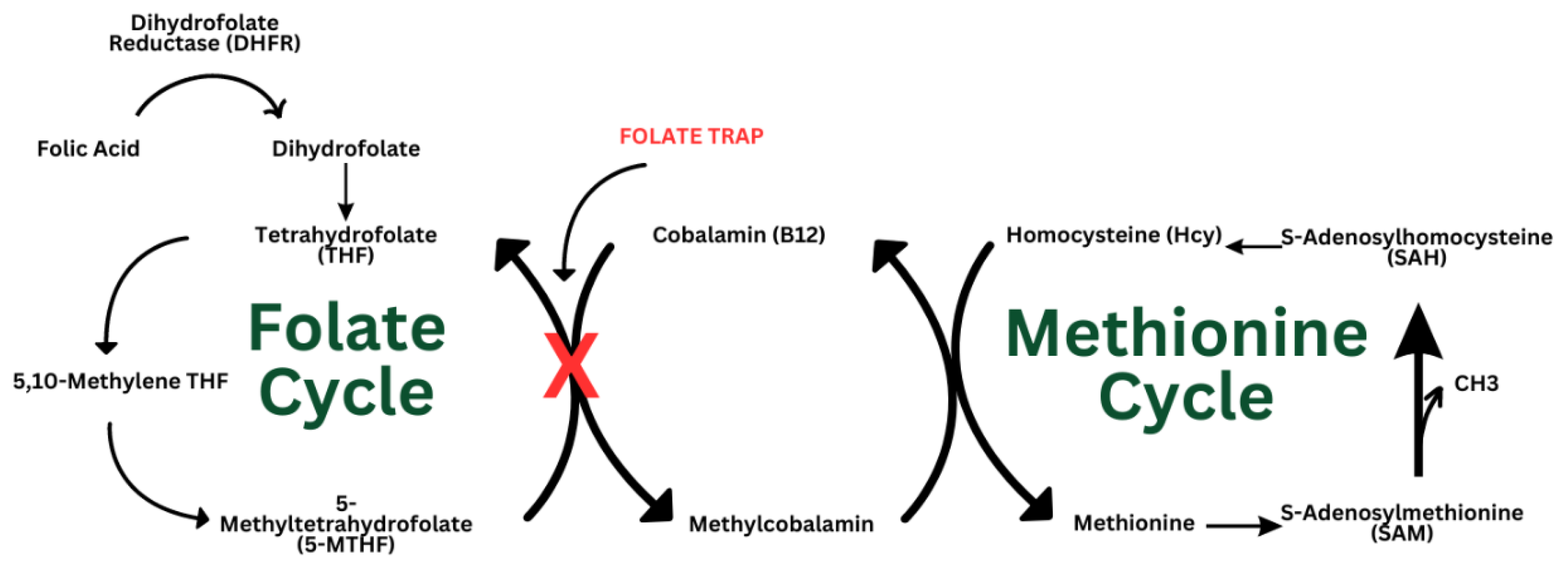

4. Folate Trap

5. Folic Acid Fortification in the US and Exacerbation of Vitamin B12 Deficiency

5.1. Implementation of Folic Acid Fortification Programs

5.2. Elevated Folate Levels May Exacerbate Vitamin B12 Deficiency

6. Folic Acid and Vitamin B12 Needs in Pregnancy

7. Folic Acid and Vitamin B12 Absorption in Celiac Disease

8. Celiac Disease and Pregnancy

9. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y., Wang, A., Yeung, L. F., Qi, Y. P., Pfeiffer, C. M., & Crider, K. S. (2023). Folate and vitamin B12 usual intake and biomarker status by intake source in United States adults aged ≥19 y: NHANES 2007-2018. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 118(1), 241–254. [CrossRef]

- Watson, J., Lee, M., & Garcia-Casal, M. N. (2018). Consequences of Inadequate Intakes of Vitamin A, Vitamin B12, Vitamin D, Calcium, Iron, and Folate in Older Persons. Current geriatrics reports, 7(2), 103–113. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. Y., Chan, L., Hu, C. J., Hong, C. T., & Chen, J. H. (2024). Role of vitamin B12 and folic acid in treatment of Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Aging, 16(9), 7856–7869. [CrossRef]

- Son, P., & Lewis, L. (2022). Hyperhomocysteinemia. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Hannibal, L., Lysne, V., Bjørke-Monsen, A. L., Behringer, S., Grünert, S. C., Spiekerkoetter, U., Jacobsen, D. W., & Blom, H. J. (2016). Biomarkers and Algorithms for the Diagnosis of Vitamin B12 Deficiency. Frontiers in molecular biosciences, 3, 27. [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, J. L., Layden, A. J., & Stover, P. J. (2015). Vitamin B-12 and Perinatal Health. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 6(5), 552–563. [CrossRef]

- Bjørke Monsen, A. L., Ueland, P. M., Vollset, S. E., Guttormsen, A. B., Markestad, T., Solheim, E., & Refsum, H. (2001). Determinants of cobalamin status in newborns. Pediatrics, 108(3), 624–630. [CrossRef]

- Theethira, T. G., Dennis, M., & Leffler, D. A. (2014). Nutritional consequences of celiac disease and the gluten-free diet. Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology, 8(2), 123–129. [CrossRef]

- Torrez, M., Chabot-Richards, D., Babu, D., Lockhart, E., & Foucar, K. (2022). How I investigate acquired megaloblastic anemia. International journal of laboratory hematology, 44(2), 236–247. [CrossRef]

- Porter, K., Hoey, L., Hughes, C. F., Ward, M., & McNulty, H. (2016). Causes, Consequences and Public Health Implications of Low B-Vitamin Status in Ageing. Nutrients, 8(11), 725. [CrossRef]

- Werder. (2010). Cobalamin deficiency, hyperhomocysteinemia, and dementia. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 159. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R. (2008). B-vitamins and prevention of dementia. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 67(1), 75–81. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Office of dietary supplements - vitamin B12. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/vitaminb12-healthprofessional/#:~:text=However%2C%20vitamin%20B12%20insufficiency%20(assessed,60%20and%20older%20%5B34%5D.

- Allen L. H. (2004). Folate and vitamin B12 status in the Americas. Nutrition reviews, 62(6 Pt 2), S29–S34. [CrossRef]

- Carboni L. (2022). Active Folate Versus Folic Acid: The Role of 5-MTHF (Methylfolate) in Human Health. Integrative medicine (Encinitas, Calif.), 21(3), 36–41.

- Miraglia, N., & Dehay, E. (2022). Folate Supplementation in Fertility and Pregnancy: The Advantages of (6S)5-Methyltetrahydrofolate. Alternative therapies in health and medicine, 28(4), 12–17.

- Milman N. (2012). Intestinal absorption of folic acid - new physiologic & molecular aspects. The Indian journal of medical research, 136(5), 725–728.

- Khan, K. M., & Jialal, I. (2023). Folic Acid Deficiency. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Reynolds E. H. (2014). The neurology of folic acid deficiency. Handbook of clinical neurology, 120, 927–943. [CrossRef]

- Kaye, A. D., Jeha, G. M., Pham, A. D., Fuller, M. C., Lerner, Z. I., Sibley, G. T., Cornett, E. M., Urits, I., Viswanath, O., & Kevil, C. G. (2020). Folic Acid Supplementation in Patients with Elevated Homocysteine Levels. Advances in therapy, 37(10), 4149–4164. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, L. M., Cordero, A. M., Pfeiffer, C. M., Hausman, D. B., Tsang, B. L., De-Regil, L. M., Rosenthal, J., Razzaghi, H., Wong, E. C., Weakland, A. P., & Bailey, L. B. (2018). Global folate status in women of reproductive age: a systematic review with emphasis on methodological issues. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1431(1), 35–57. [CrossRef]

- Fardous, A. M., & Heydari, A. R. (2023). Uncovering the Hidden Dangers and Molecular Mechanisms of Excess Folate: A Narrative Review. Nutrients, 15(21), 4699. [CrossRef]

- Nexo, E., & Hoffmann-Lücke, E. (2011). Holotranscobalamin, a marker of vitamin B-12 status: analytical aspects and clinical utility. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 94(1), 359S–365S. [CrossRef]

- Clare, C. E., Brassington, A. H., Kwong, W. Y., & Sinclair, K. D. (2019). One-Carbon Metabolism: Linking Nutritional Biochemistry to Epigenetic Programming of Long-Term Development. Annual review of animal biosciences, 7, 263–287. [CrossRef]

- Ferrazzi, E., Tiso, G., & Di Martino, D. (2020). Folic acid versus 5- methyl tetrahydrofolate supplementation in pregnancy. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology, 253, 312–319. [CrossRef]

- Nelen, W. L., Blom, H. J., Steegers, E. A., den Heijer, M., & Eskes, T. K. (2000). Hyperhomocysteinemia and recurrent early pregnancy loss: a meta-analysis. Fertility and sterility, 74(6), 1196–1199. [CrossRef]

- Refsum, H., Ueland, P. M., Nygård, O., & Vollset, S. E. (1998). Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease. Annual review of medicine, 49, 31–62. [CrossRef]

- Pinzon RT, Wijaya VO, Veronica V. The role of homocysteine levels as a risk factor of ischemic stroke events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2023 May 12;14:1144584.

- Murphy, M. E., & Westmark, C. J. (2020). Folic Acid Fortification and Neural Tube Defect Risk: Analysis of the Food Fortification Initiative Dataset. Nutrients, 12(1), 247. [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, C. M., Johnson, C. L., Jain, R. B., Yetley, E. A., Picciano, M. F., Rader, J. I., Fisher, K. D., Mulinare, J., & Osterloh, J. D. (2007). Trends in blood folate and vitamin B-12 concentrations in the United States, 1988 2004. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 86(3), 718–727. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. H., Yates, Z., Veysey, M., Heo, Y. R., & Lucock, M. (2014). Contemporary issues surrounding folic Acid fortification initiatives. Preventive nutrition and food science, 19(4), 247–260. [CrossRef]

- Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. MRC Vitamin Study Research Group. (1991). Lancet (London, England), 338(8760), 131–137.

- Ray, J. G., Vermeulen, M. J., Langman, L. J., Boss, S. C., & Cole, D. E. (2003). Persistence of vitamin B12 insufficiency among elderly women after folic acid food fortification. Clinical biochemistry, 36(5), 387–391. [CrossRef]

- Morris, M. S., Jacques, P. F., Rosenberg, I. H., & Selhub, J. (2010). Circulating unmetabolized folic acid and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate in relation to anemia, macrocytosis, and cognitive test performance in American seniors. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(6), 1733–1744. [CrossRef]

- Selhub, J., & Paul, L. (2011). Folic acid fortification: why not vitamin B12 also?. BioFactors (Oxford, England), 37(4), 269–271. [CrossRef]

- Morris, M. S., Jacques, P. F., Rosenberg, I. H., & Selhub, J. (2007). Folate and vitamin B-12 status in relation to anemia, macrocytosis, and cognitive impairment in older Americans in the age of folic acid fortification. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 85(1), 193–200. [CrossRef]

- Kalmbach, R. D., Choumenkovitch, S. F., Troen, A. M., D'Agostino, R., Jacques, P. F., & Selhub, J. (2008). Circulating folic acid in plasma: relation to folic acid fortification. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 88(3), 763–768. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M. R., McPartlin, J., & Scott, J. (2007). Folic acid fortification and public health: report on threshold doses above which unmetabolised folic acid appear in serum. BMC public health, 7, 41. [CrossRef]

- Obeid, R., Kasoha, M., Kirsch, S. H., Munz, W., & Herrmann, W. (2010). Concentrations of unmetabolized folic acid and primary folate forms in pregnant women at delivery and in umbilical cord blood. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 92(6), 1416–1422. [CrossRef]

- Tam, C., O'Connor, D., & Koren, G. (2012). Circulating unmetabolized folic Acid: relationship to folate status and effect of supplementation. Obstetrics and gynecology international, 2012, 485179. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M. R., McPartlin, J., Weir, D. G., Daly, S., Pentieva, K., Daly, L., & Scott, J. M. (2005). Evidence of unmetabolised folic acid in cord blood of newborn and serum of 4-day-old infants. The British journal of nutrition, 94(5), 727–730. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, N. N., Mahajan, K. N., Soni, R. N., & Gaikwad, N. L. (2007). Justifying the "Folate trap" in folic acid fortification programs. Journal of perinatal medicine, 35(3), 241–242. [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Rodríguez, J., Díaz-López, A., Canals-Sans, J., & Arija, V. (2023). Maternal Vitamin B12 Status during Pregnancy and Early Infant Neurodevelopment: The ECLIPSES Study. Nutrients, 15(6), 1529. [CrossRef]

- Shields, R. C., Caric, V., Hair, M., Jones, O., Wark, L., McColl, M. D., & Ramsay, J. E. (2011). Pregnancy-specific reference ranges for haematological variables in a Scottish population. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology : the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 31(4), 286–289. [CrossRef]

- Heppe, D. H., Medina-Gomez, C., Hofman, A., Franco, O. H., Rivadeneira, F., & Jaddoe, V. W. (2013). Maternal first-trimester diet and childhood bone mass: the Generation R Study. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 98(1), 224–232. [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, P., Sukumar, N., Adaikalakoteswari, A., Goljan, I., Venkataraman, H., Gopinath, A., Bagias, C., Yajnik, C. S., Stallard, N., Ghebremichael-Weldeselassie, Y., & Fall, C. H. D. (2021). Association of maternal vitamin B12 and folate levels in early pregnancy with gestational diabetes: a prospective UK cohort study (PRiDE study). Diabetologia, 64(10), 2170–2182. [CrossRef]

- Reznikoff-Etiévant, M. F., Zittoun, J., Vaylet, C., Pernet, P., & Milliez, J. (2002). Low Vitamin B(12) level as a risk factor for very early recurrent abortion. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology, 104(2), 156–159. [CrossRef]

- Hübner, U., Alwan, A., Jouma, M., Tabbaa, M., Schorr, H., & Herrmann, W. (2008). Low serum vitamin B12 is associated with recurrent pregnancy loss in Syrian women. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine, 46(9), 1265–1269. [CrossRef]

- Bondevik, G. T., Schneede, J., Refsum, H., Lie, R. T., Ulstein, M., & Kvåle, G. (2001). Homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels in pregnant Nepali women. Should cobalamin supplementation be considered?. European journal.

- Hay, G., Clausen, T., Whitelaw, A., Trygg, K., Johnston, C., Henriksen, T., & Refsum, H. (2010). Maternal folate and cobalamin status predicts vitamin status in newborns and 6-month-old infants. The Journal of nutrition, 140(3), 557–564. [CrossRef]

- Ronnenberg, A. G., Goldman, M. B., Chen, D., Aitken, I. W., Willett, W. C., Selhub, J., & Xu, X. (2002). Preconception homocysteine and B vitamin status and birth outcomes in Chinese women. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 76(6), 1385–1391. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M. S., Kahn, S. R., Rozen, R., Evans, R., Platt, R. W., Chen, M. F., Goulet, L., Séguin, L., Dassa, C., Lydon, J., McNamara, H., Dahhou, M., & Genest, J. (2009). Vasculopathic and thrombophilic risk factors for spontaneous preterm birth. International journal of epidemiology, 38(3), 715–723. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler S. Assessment and interpretation of micronutrient status during pregnancy: Symposium on ‘Translation of research in nutrition II: the bed.’ Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2008;67(4):437-450. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X., Gao, F., Qiu, Y., Bao, J., Gu, X., Long, Y., Liu, F., Cai, M., & Liu, H. (2018). Association of maternal serum homocysteine concentration levels in late stage of pregnancy with preterm births: a nested case-control study. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians, 31(20), 2673–2677. [CrossRef]

- Muthayya, S., Kurpad, A. V., Duggan, C. P., Bosch, R. J., Dwarkanath, P., Mhaskar, A., Mhaskar, R., Thomas, A., Vaz, M., Bhat, S., & Fawzi, W. W. (2006). Low maternal vitamin B12 status is associated with intrauterine growth retardation in urban South Indians. European journal of clinical nutrition, 60(6), 791–801. [CrossRef]

- Relton, C. L., Pearce, M. S., & Parker, L. (2005). The influence of erythrocyte folate and serum vitamin B12 status on birth weight. The British journal of nutrition, 93(5), 593–599. [CrossRef]

- Dwarkanath, P., Barzilay, J. R., Thomas, T., Thomas, A., Bhat, S., & Kurpad, A. V. (2013). High folate and low vitamin B-12 intakes during pregnancy are associated with small-for-gestational age infants in South Indian women: a prospective observational cohort study. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 98(6), 1450–1458. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H. L., Cao, L. Q., & Chen, H. Y. (2016). Blood folic acid, vitamin B12, and homocysteine levels in pregnant women with fetal growth restriction. Genetics and molecular research : GMR, 15(4), 10.4238/gmr15048890. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Xin, R., Gu, X., Wang, F., Pei, L., Lin, L., Chen, G., Wu, J., & Zheng, X. (2009). Maternal serum vitamin B12, folate and homocysteine and the risk of neural tube defects in the offspring in a high-risk area of China. Public health nutrition, 12(5), 680–686. [CrossRef]

- Czeizel, A. E., & Dudás, I. (1992). Prevention of the first occurrence of neural-tube defects by periconceptional vitamin supplementation. The New England journal of medicine, 327(26), 1832–1835. [CrossRef]

- Obeid, R., Eussen, S. J. P. M., Mommers, M., Smits, L., & Thijs, C. (2022). Imbalanced Folate and Vitamin B12 in the Third Trimester of Pregnancy and its Association with Birthweight and Child Growth up to 2 Years. Molecular nutrition & food research, 66(2), e2100662. [CrossRef]

- Rogne, T., Tielemans, M. J., Chong, M. F., Yajnik, C. S., Krishnaveni, G. V., Poston, L., Jaddoe, V. W., Steegers, E. A., Joshi, S., Chong, Y. S., Godfrey, K. M., Yap, F., Yahyaoui, R., Thomas, T., Hay, G., Hogeveen, M., Demir, A., Saravanan, P., Skovlund, E., Martinussen, M. P., … Risnes, K. R. (2017). Associations of Maternal Vitamin B12 Concentration in Pregnancy With the Risks of Preterm Birth and Low Birth Weight: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data. American journal of epidemiology, 185(3), 212–223. [CrossRef]

- Clément, A., Clément, P., Viot, G., & Menezo, Y. J. (2023). Correction to: The importance of preconception Hcy Testing: Identification of a folate trap syndrome in a woman attending an assisted reproduction program. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 41(1), 233–233. [CrossRef]

- Bergen, N. E., Jaddoe, V. W., Timmermans, S., Hofman, A., Lindemans, J., Russcher, H., Raat, H., Steegers-Theunissen, R. P., & Steegers, E. A. (2012). Homocysteine and folate concentrations in early pregnancy and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: the Generation R Study. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, 119(6), 739–751. [CrossRef]

- Krishnaveni, G. V., Hill, J. C., Veena, S. R., Bhat, D. S., Wills, A. K., Karat, C. L., Yajnik, C. S., & Fall, C. H. (2009). Low plasma vitamin B12 in pregnancy is associated with gestational 'diabesity' and later diabetes. Diabetologia, 52(11), 2350–2358. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Hou, Y., Yan, X., Wang, Y., Shi, C., Wu, X., Liu, H., Zhang, L., Zhang, X., Liu, J., Zhang, M., Zhang, Q., & Tang, N. (2019). Joint effects of folate and vitamin B12 imbalance with maternal characteristics on gestational diabetes mellitus. Journal of diabetes, 11(9), 744–751. [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J. F., Leffler, D. A., Bai, J. C., Biagi, F., Fasano, A., Green, P. H., Hadjivassiliou, M., Kaukinen, K., Kelly, C. P., Leonard, J. N., Lundin, K. E., Murray, J. A., Sanders, D. S., Walker, M. M., Zingone, F., & Ciacci, C. (2013). The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut, 62(1), 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Tapia, A., Hill, I. D., Kelly, C. P., Calderwood, A. H., Murray, J. A., & American College of Gastroenterology (2013). ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. The American journal of gastroenterology, 108(5), 656–677. [CrossRef]

- Lebwohl, B., Sanders, D. S., & Green, P. H. R. (2018). Coeliac disease. Lancet (London, England), 391(10115), 70–81. [CrossRef]

- Choung, R. S., Unalp-Arida, A., Ruhl, C. E., Brantner, T. L., Everhart, J. E., & Murray, J. A. (2016). Less Hidden Celiac Disease But Increased Gluten Avoidance Without a Diagnosis in the United States: Findings From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys From 2009 to 2014. Mayo Clinic proceedings, S0025-6196(16)30634-6. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S., & Leffler, D. (2010). Celiac disease: An underappreciated issue in women’s health. Women’s Health, 6(5), 753–766. [CrossRef]

- Fish, E. M., Shumway, K. R., & Burns, B. (2024). Physiology, Small Bowel. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Wierdsma, N. J., van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren, M. A., Berkenpas, M., Mulder, C. J., & van Bodegraven, A. A. (2013). Vitamin and mineral deficiencies are highly prevalent in newly diagnosed celiac disease patients. Nutrients, 5(10), 3975–3992. [CrossRef]

- Dahele, A., & Ghosh, S. (2001). Vitamin B12 deficiency in untreated celiac disease. The American journal of gastroenterology, 96(3), 745–750. [CrossRef]

- Bledsoe, A. C., King, K. S., Larson, J. J., Snyder, M., Absah, I., Choung, R. S., & Murray, J. A. (2019). Micronutrient deficiencies are common in contemporary celiac disease despite lack of overt malabsorption symptoms. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 94(7), 1253–1260. [CrossRef]

- Kemppainen, T. A., Kosma, V. M., Janatuinen, E. K., Julkunen, R. J., Pikkarainen, P. H., & Uusitupa, M. I. (1998). Nutritional status of newly diagnosed celiac disease patients before and after the institution of a celiac disease diet--association with the grade of mucosal villous atrophy. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 67(3), 482–487. [CrossRef]

- Caruso, R., Pallone, F., Stasi, E., Romeo, S., & Monteleone, G. (2013). Appropriate nutrient supplementation in celiac disease. Annals of Medicine, 45(8), 522–531. [CrossRef]

- Cardo, A., Churruca, I., Lasa, A., Navarro, V., Vázquez-Polo, M., Perez-Junkera, G., & Larretxi, I. (2021). Nutritional Imbalances in Adult Celiac Patients Following a Gluten-Free Diet. Nutrients, 13(8), 2877. [CrossRef]

- Hallert, C., Grant, C., Grehn, S., Grännö, C., Hultén, S., Midhagen, G., Ström, M., Svensson, H., & Valdimarsson, T. (2002). Evidence of poor vitamin status in coeliac patients on a gluten-free diet for 10 years. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 16(7), 1333–1339. [CrossRef]

- Hallert, C., Svensson, M., Tholstrup, J., & Hultberg, B. (2009). Clinical trial: B vitamins improve health in patients with coeliac disease living on a gluten-free diet. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 29(8), 811–816. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, H., Reeves, S., & Jeanes, Y. M. (2019). Identifying and improving adherence to the gluten-free diet in people with coeliac disease. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 78(3), 418–425. [CrossRef]

- Mehtab, W., Agarwal, A., Chauhan, A. et al. Barriers at various levels of human ecosystem for maintaining adherence to gluten free diet in adult patients with celiac disease. Eur J Clin Nutr 78, 320–327 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Abu-Janb, N., & Jaana, M. (2020). Facilitators and barriers to adherence to gluten-free diet among adults with celiac disease: a systematic review. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics : the official journal of the British Dietetic Association, 33(6), 786–810. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. R., Wolf, R. L., Lebwohl, B., Ciaccio, E. J., & Green, P. H. R. (2019). Persistent Economic Burden of the Gluten Free Diet. Nutrients, 11(2), 399. [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, D., Fortunato, F., Tafuri, S., Germinario, C. A., & Prato, R. (2010). Reproductive life disorders in Italian celiac women. A case-control study. BMC gastroenterology, 10, 89. [CrossRef]

- Arvanitakis, K., Siargkas, A., Germanidis, G., Dagklis, T., & Tsakiridis, I. (2023). Adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with celiac disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of gastroenterology, 36(1), 12–24. [CrossRef]

- Sher, K. S., & Mayberry, J. F. (1996). Female fertility, obstetric and gynaecological history in coeliac disease: a case control study. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). Supplement, 412, 76–77. [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J. F., Montgomery, S. M., & Ekbom, A. (2005). Celiac disease and risk of adverse fetal outcome: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology, 129(2), 454–463. [CrossRef]

- Castaño, M., Gómez-Gordo, R., Cuevas, D., & Núñez, C. (2019). Systematic Review and meta-analysis of prevalence of coeliac disease in women with infertility. Nutrients, 11(8), 1950. [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, P., Troncone, R., Paparo, F., Torre, P., Trapanese, E., Fasano, C., Lamberti, A., Budillon, G., Nardone, G., & Greco, L. (2000). Coeliac disease and unfavourable outcome of pregnancy. Gut, 46(3), 332–335. [CrossRef]

- Nørgård, B., Fonager, K., Sørensen, H. T., & Olsen, J. (1999). Birth outcomes of women with celiac disease: a nationwide historical cohort study. The American journal of gastroenterology, 94(9), 2435–2440. [CrossRef]

- Oxentenko, A. S., & Rubio-Tapia, A. (2019). Celiac disease. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 94(12), 2556–2571. [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, F., Martinelli, D., Prato, R., & Pedalino, B. (2014). Results fromad hocand routinely collected data among celiac women with infertility or pregnancy related disorders: Italy, 2001–2011. The Scientific World Journal, 2014, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Nellikkal, S. S., Hafed, Y., Larson, J. J., Murray, J. A., & Absah, I. (2019). High Prevalence of Celiac Disease Among Screened First-Degree Relatives. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 94(9), 1807–1813. [CrossRef]

- Boers, K., Vlasveld, T., & van der Waart, R. (2019). Pregnancy and coeliac disease. BMJ case reports, 12(12), e233226. [CrossRef]

| Symptoms | Signs | Lab Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | Beefy red tongue | Megaloblastic anemia |

| Cognitive decline | Ataxia | Anisocytosis |

| Upper or lower extremity paresthesia | Diminished proprioception | Poikilocytosis |

| Loss of balance | Diminished vibratory sense | Hyper segmented neutrophils |

| Falls | Romberg’s sign | Hyperhomocysteinemia |

| Symptoms | Signs | Lab Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | Pale skin | Megaloblastic anemia |

| Cognitive decline | Mouth sores | Anisocytosis |

| Irritability | Diminished proprioception | Poikilocytosis |

| Decreased Appetite | Diminished vibratory sense | Hyper segmented neutrophils |

| Diarrhea | Smooth and tender tongue | Hyperhomocysteinemia |

| Vitamin B12 | Folate | |

|---|---|---|

| Adults | 2.4 μg/day | 400 μg/day |

| Pregnant Women | 2.6 μg/day | 600 μg/day |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).