Introduction

Character education is very important and fundamental for students in the age of technology (Kim, 2023; Yulia et al., 2022). In fact, this has become a major topic in various scientific discussions (Brestovanský, 2024). Character education in the United Kingdom and the United States of America fuelled political activity, as governments and educators saw that character education could be used to address social problems (Jerome & Kisby, 2019; Hastasari et al., 2022). However, there are also societies in various countries that are experiencing a crisis of morality and virtue (Kayange, 2023). These groups are students who live and stay in rural, underdeveloped, and remote areas. They experience poverty and economic constraints. They also do not receive proper formal education, especially character education (Stone, 2023). They have limited access to education (Prasetio et al., 2021) and information technology.

Students living in rural areas always experience political instability (Viartasiwi, 2013), social conflicts (Roberts & Green, 2013), riots, tribal wars (Yampap & Haryanto, 2023; Putra et al., 2024) marginalisation and oppression (Kebede et al., 2021). They experience hygiene and health issues (Chambers et al., 2024; Bourke et al., 2012), difficulties in socialising with others, increased school dropout rates (F. Liu, 2004), even 50% of rural students lose their right to learn (UNICEF, 2016; Ravet & Mtika, 2024), lack of qualified teachers (Ravet & Mtika, 2024), lack of education funding (Wallin, & Reimer 2008). Students also lose access to role models or mentors who can provide strong character guidance and limited services. Parents are unable to accompany their children; due to the low levels of education and economic status (Li et al., 2024; Hermino & Arifin, 2020; du Plessis, 2014; Guo & Chen, 2023)

The problems described above are also experienced by students in the inland and outermost regions of Papua Indonesia (Yampap & Haryanto, 2023). These issues, if left unaddressed, can affect children's psychology. Limited physical and social access to the outside community makes students feel isolated and lonely. Children tend to feel inferior when they are with friends who are outside their environment and culture. This leads to lack of confidence, fear, reluctance to open and lack of motivation to learn (Yao, 2022). Therefore, one of the efforts to overcome this problem is to improve the quality of dormitory-based character education. Dormitory-based character education is an educational approach that brings students from inland and outermost areas to live and learn with teachers in a dormitory environment for a period. This assertion is relevant to Liu & Villa’s (2020) research findings on children in rural China who live and study in dormitories. They found that boarding schools can improve cognitive outcomes, create better learning, and help children from disadvantaged family backgrounds.

Taruna Papua Indonesia Boarding School is a formal primary and secondary school that integrates local cultural values with school learning and boarding life. The school is managed by the Lokon Education Foundation. There are approximately 1,356 students who are taught and cared for at this boarding school. They come from two indigenous tribes: the Amungme who live in the mountains, the Kamoro who live on the coast, and five other related tribes: the Moni, Dani, Nduga, Damal and Lanny. This assertion is supported by Katanski's (2005) statement that boarding schools are deliberately created to unite children from different countries with different ethnicities, languages, and to preserve local cultures in schools. As an attempt to overcome the situation that divides the tribes.

Although this is not the first research on dormitory-based character education, the novelty of this research focuses on an in-depth analysis of a Papuan contextual culture-based character education model for students from the mountainous interior and coastal suburbs. These students not only come from different ethnicities, cultures, and languages, but also have differences in character, attitudes, and relationship patterns.

Therefore, the purpose of this research is to analyse a dormitory-based character education model by implementing Papuan cultural contextual education in all education and childcare. This research is expected to be a new character education model in integrating local Papuan cultural values into school learning and children's daily life in dormitories. The character and personality education of children will be carried out through an integrated system between school and out-of-school influences.

Literature Review

Character education is a national movement to create schools that develop ethical, responsible; and caring young people by modelling and teaching good character through emphasis on universal values that we all share (Pala, 2011; Frye et all, 2002; (Singh, 2019). Good character education is one of the keys to education in schools (Faizin, 2019). Character education has been implemented from pre-school to higher education (Hoge, 2002; Althof & Berkowitz*, 2006). Character education differs from moral education. Moral education tends to be theory-based, constructivist and cognitively structured. (Althof & Berkowitz*, 2006; Chan, 2020). In contrast, character education is ‘atheoretical’ compared to moral education. Character education is more concerned with achieving desirable behavioural outcomes (Chan, 2020). Lickona et al., (2002) emphasises that character education has three main elements: knowing the good, wanting the good and doing the good.

Based on these three elements someone is considered to have a good character if they know the good (moral knowledge), have interest in the good (moral feeling) and do good (Rokhman et al., 2014). Therefore, character education aims to develop students' ability to make good and bad choices to understand, interpret, and uphold what is good, and to recognise this goodness in everyday life. In this regard, Lickona (2015) mentions seven essential and primary character elements that need to be instilled in students, namely sincerity or honesty, compassion, courage, kindness, self-control, cooperation, and diligence or hard work. These seven core character traits are the most important and primary to develop in students at school, in addition to many other character values. The same opinion is expressed by Singh (2019), namely character education is the intentional, proactive effort by schools, districts, and states to instil in their student’s important core, ethical values such as caring, honesty, fairness, responsibility, and respect for self and others.

Local culture is all the ideas, activities, and results of human activities in a community group in a particular place. Thus, local cultural sources are the values, activities, and outcomes of traditional activities (Pangalila et al., 2021b). Local wisdom can function as advice, beliefs, literature, taboos for conservation and protection of natural resources, human resource development, culture, and science, social, political, ethical, and moral (Berkowitz & Ben-Artzi, 2024) (Pangalila et al., 2021a). Character education is a deliberate effort to develop good character based on core values that are good for the individual and good for society (Faizin, 2019; Singh, 2019).

Schools become agents for cultivating character values through learning and internalising of local cultural values (Berges Puyo, 2020). Local culture-based education is a strategy for creating and designing a learning experience that incorporates culture as part of the learning process. The main elements of local culture-based character education are the integration of local cultural values in the learning curriculum, teaching materials that reflect the local culture, teachers and trainers who involve local communities, and respect for diversity. (Yampap & Haryanto, 2023). The aim of culturally responsive character education is for students to quickly understand knowledge, identity, and moral values in the context of their daily lives. Other research by Yampap & Haryanto (2023) shows that tradition of burning stones, practised by indigenous Papuan Indonesians can promote students' sense of nationalism, mutual respect, solidarity, togetherness, concern for others, and gratitude to the Almighty.

Boarding education is an educational approach in which students live and learn in a community. The school provides different types of accommodation for students during their education. Teachers and students live together in a community. Lomawaima & Whitt (2023) assert that boarding schools are an effective means of separating the younger generation from 'tribal' influences and instilling discipline. For this reason, boarding school education is holistic. Students not only academic learning, but also extracurricular activities (Dvali, 2024a) such as arts, health, sports, literacy, and other social activities (Lomawaima & Whitt, 2023). Children are taught life values such as discipline, respect, cleanliness, health, independence (Zhang, 2020), self-confidence and responsibility. These values are instilled in students through school rules, daily routines, and interactions with staff and fellow students. Boarding school education is an immersive, valuable experience and helps students develop in all aspects of morality, intelligence, physical fitness, beauty, hard work, and discipline (Yaxuan, 2023).

Students living in boarding schools have a strong sense of community (Gangloff, 2023). Students participate together in all activities such as prayer, study, and sport. Trafzer et al. (2006) found that students must adapt to a regulated daily schedule: waking up, resting, queuing for meals, going to class, study times set by bells. Boarding schools also reduce undesirable student behaviour, such as absenteeism (Martin et al., 2014). A survey conducted by the American Association of Boarding Schools (2013) found that 68% of boarding school students believe that boarding school helped them improve self-discipline, maturity, independence, cooperative learning, and critical thinking. The aim is to form a positive spirit of solidarity, eliminate negative feelings, interpersonal communication and get along harmoniously with housemates (Zhang & Tan, 2023).

The dormitory not only has the basic functions of life support, but also has the special function of educational functions. It is a bridge for teachers and students to communicate feelings and ideas, a platform for students to cultivate their mental health and independence, and a cradle of civilized behavior and high moral feelings. Therefore, dormitories are called the "first society", "second family" and "third classroom" for students (Zhao & Liu, 2022).

Method

This research uses a qualitative method with a grounded theory approach. Grounded theory is a qualitative method that inductively uses a set of systematic procedures to provide a theory about the phenomenon under study (Corbin & Strauss, 2014). The aim of this method is to build a theory that provides an abstract understanding of one or more of the core issues under study (Charmaz & Thornberg, 2021). There were 14 respondents in this study, consisting of the school principal, dormitory head, character development coordinator, dormitory supervisor, and students.

Table 1 shows the basic information about the respondents. The data collection techniques were semi-structured interviews with respondents and documentation in the form of boarding schoolwork programmes and character development programmes for students. To validate the data collection methods, the researcher used data triangulation from different informants and finally conducted discussions with peers in the form of focus group discussions (Creswell & David, 2018). The Atlas.ti application was used for data analysis. Data analysis starts with the coding stage, which is divided into three stages, namely open coding, axial coding, and selective coding (J. Li, 2022; Hamedinasab et al., 2023).

Results

Open coding is the process of coding sentence by sentence from the original data. There were 14 respondents who provided responses on the topic of the dormitory-based character education model at Taruna School in Papua Indonesia. After several rounds of careful analysis, the researcher obtained 27 categories of initial concepts that appeared frequently. The results of processing the initial categories from the initial coding are presented in

Figure 1 in the form of word clouds.

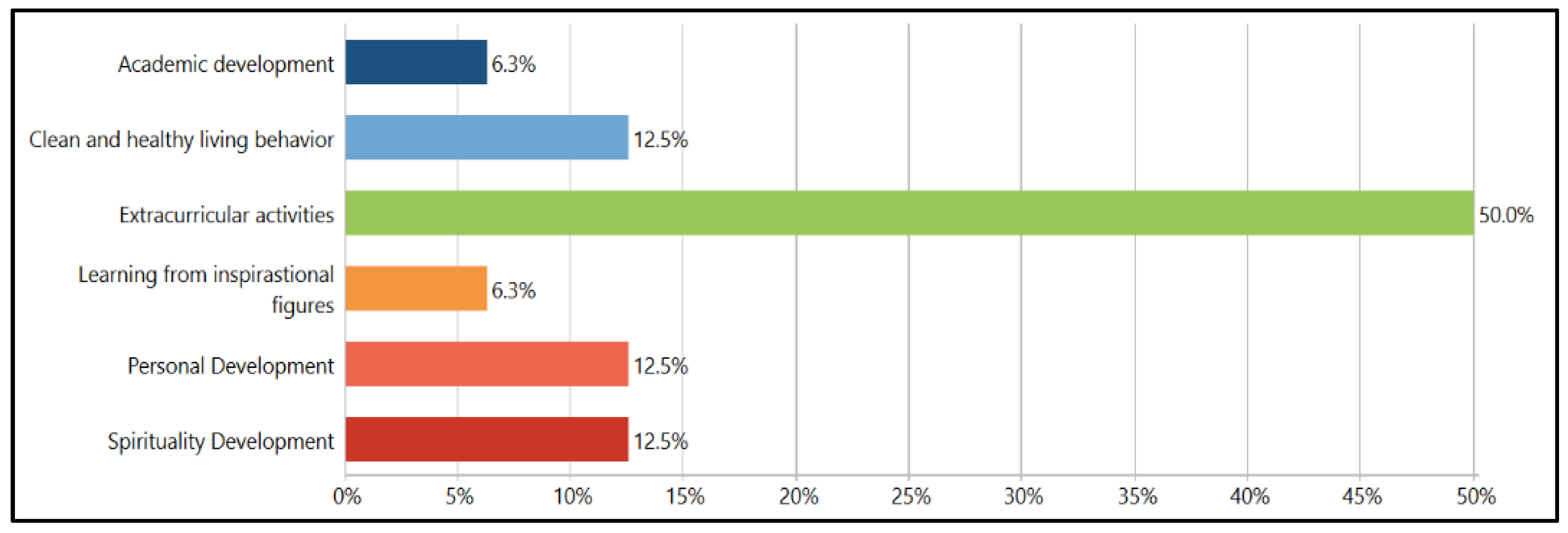

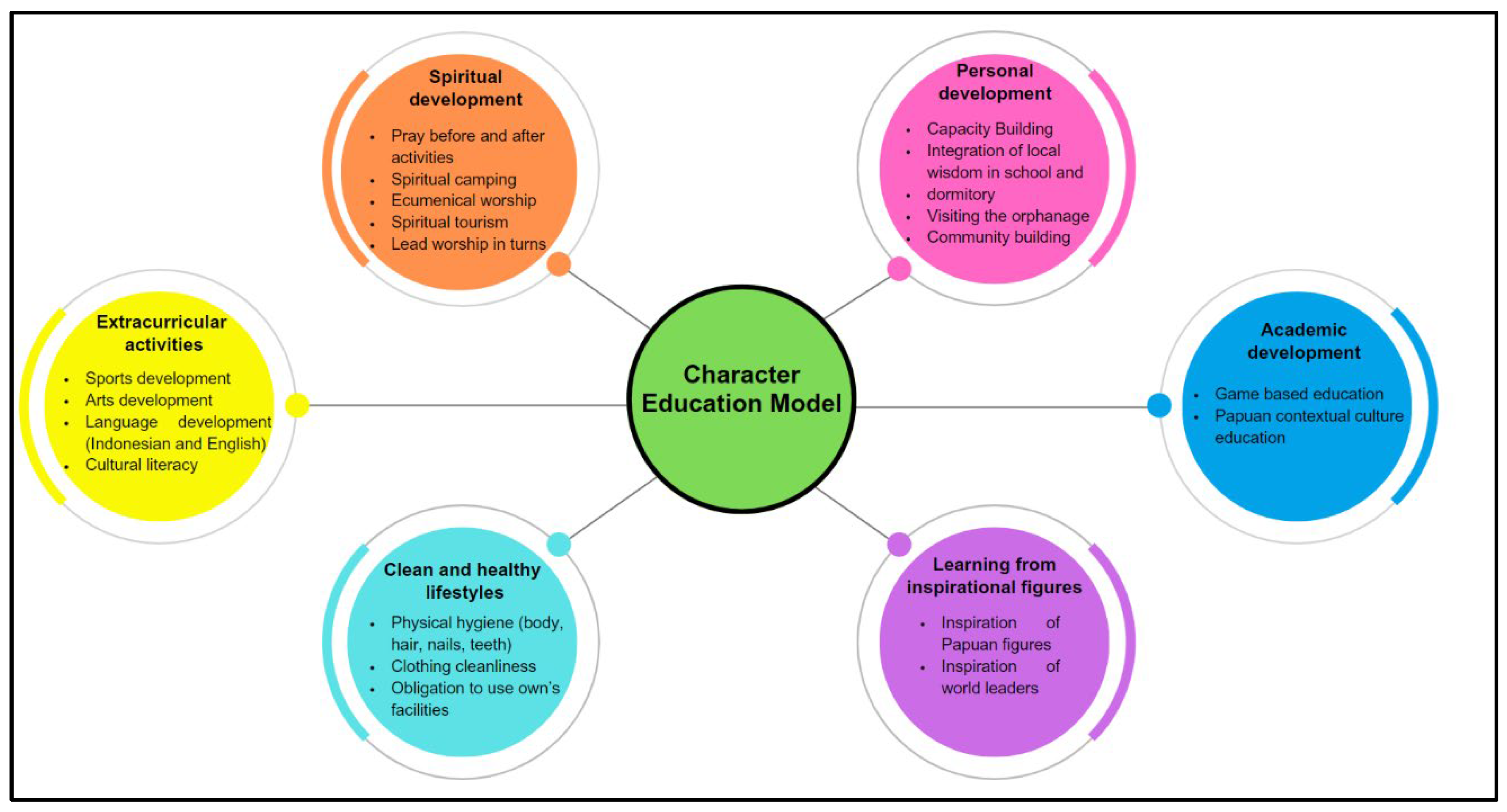

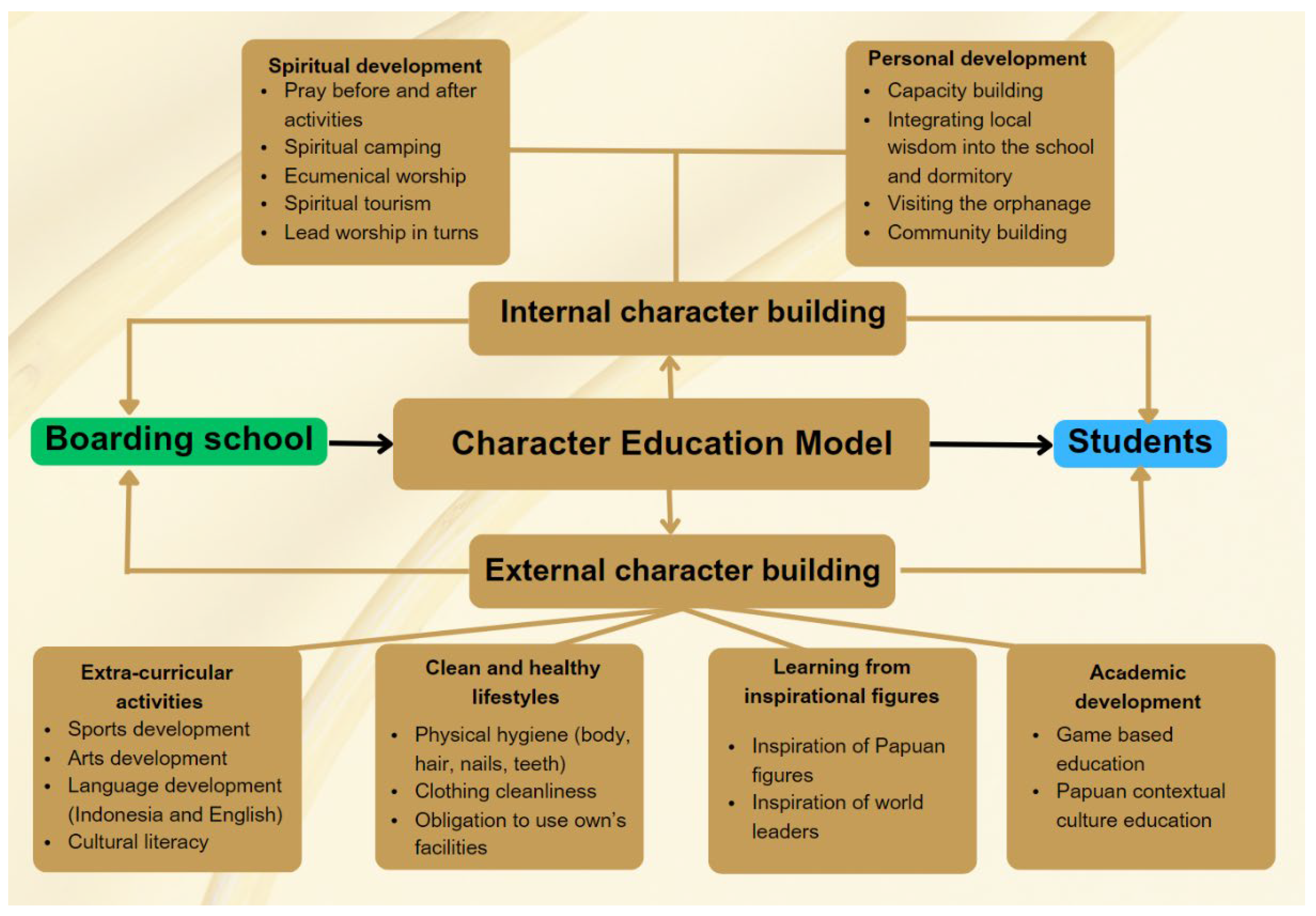

In the next stage, the researcher conducted axial coding using cluster analysis of the open coding data. In this way, the researcher combined similar codes to construct a more general macro concept. Based on the 27 frequently occurring categories, the researcher found six theoretical concepts as a form of dormitory-based character education model at Taruna Papua School, namely personal development, spiritual development, extracurricular activities, clean and healthy lifestyles, learning from inspirational figures, and academic development (Figure 3). Furthermore, the researcher made logical connections between these concepts and finally the theoretical structure is shown in

Table 2. In addition, the concepts of personal development and spiritual development were grouped into internal character building. External character building includes the concept of extracurricular activities, clean and healthy lifestyles, learning from inspirational figures and academic development.

Based on the results of the open coding (

Figure 2), the concept of extracurricular activities is a character development model that is very popular among students. 50% of respondents recognised the specificity of this programme. This means that most students like the character education model in the form of extra-curricular activities such as sports, arts, language, and cultural development. Pupils prefer and are interested in interest and talent development activities.

Based on the six core concepts and the results of clustering character education through the first two levels of coding, the researchers used selective coding to build a theoretical model of character education. We call this ‘dormitory-based character education theory’ (Figure 4). The axial coding results (

Figure 3) show that each core concept has subcategories. Self-development has for subcategories, namely capacity building, integrating local wisdom in schools and dormitories, visiting orphanages, and building communities. The concept of spiritual development has five subcategories, namely praying before and after activities, spiritual camping, ecumenical workship, spiritual tourism, and leading worship in turn.

The concept of extra-curricular activities has four subcategories namely sports development, arts development, language development (Indonesian and English) and cultural literacy. The concept of clean and healthy lifestyles has three subcategories, namely body hygiene (body, hair, nails, teeth), clothing hygiene, and the obligation to use own’s facilities. The concept of learning from inspirational figures has two subcategories, namely inspiration from Papuan figures and inspiration from world figures. The concept of academic development has two subcategories, namely game-based education, and Papuan contextual cultural education.

Figure 4 shows that the character education model can be divided into two parts: first, internal character building, which includes spiritual development and personal development; second, external character development which includes extracurricular activities, clean and healthy lifestyles, learning from inspirational figures and academic development. Effective character education combines these two aspects in a balanced way. Holistic character education in boarding schools helps everyone to develop positive moral values and attitudes internally, while strengthening environmental influences and external role models to support the development of good character.

Discussion

The general findings are to identify and explain the concept of character education of students in boarding schools. One of the uniqueness of character education is the integration of local cultural values in the whole process of children's character education, both in the school environment and in the boarding house. This finding is relevant to Guo & Chen’s (2023) statement that boarding schools should pay attention to character education that incorporates local language, community cultural values and family culture. Although students live and stay in dormitories away from their families, local language, cultural and family values are still preserved in boarding school life. Boarding education does not remove children from local cultural values such as local language and family culture. Integrating local culture into the character education of boarding students further strengthens and enriches the value of local wisdom in education. Birquier et al., (1998) assert that the traditional culture inheritance function of the family is irreplaceable in protecting the transmission of moral values from generation to generation. Katanski (2005) asserts that representations of the boarding school experience in late 20th century Native American literature express a complex combination of tribal nationalism and solidarity.

The results showed that one form of character development is a clean and healthy lifestyle. Dormitory supervisors help students to live a healthy and clean lifestyle, both in terms of personal hygiene (body, hair, nails, teeth) and clothing hygiene. Students are required to use their own facilities. They are not allowed to use other people's bathing facilities or clothing. Students are given nutritious food every day. Similarly, Trafzer et al., (2006) states that the boarding school experience has changed the lives of thousands of Native American children. The boarding school pattern of education transformed students from 'savages' to 'civilised' people. Boarding school officials bathed children and cut their hair to kill lice (L. Li et al., 2024). Marasinghe et al., (2024) found that the boarding school environment had an impact on students' health. Every day, housemasters regularly open the windows to increase the flow of air in the dormitories. The design of the dormitories and a healthy environment provide comfort and health for the children.

The form of dormitory-based character education model at Taruna Papua School, namely play-based education, and Papuan contextual cultural education, can improve students' learning outcomes and motivation. Through language development, students can already write and speak English fluently. Their motivation to learn is increased through game-based learning and Papuan contextual cultural education. Boarding schools help students receive multicultural education, increase students' socialisation (White, 2004), and improve students' academic performance (Zhou & Xu, 2021). Boarding schools improve and standardise students' learning time by providing a good learning environment (Zhong et al., 2024; Yao & Gao, 2018), which in turn improves students' academic achievement (Foliano et al., 2019;Curto & Fryer, 2014). Similarly, (Martin et al., 2014) found that boarding students had more continuous access to professional educator education than non-boarding students. Kahane (1988) believes that boarding schools provide opportunities for students to experience roles and rules, thereby promoting the all-round development of students.

One of the character education concepts found in this research is that students learn from inspirational figures. Students are given the opportunity to watch, listen and learn from the lives and inspirations of indigenous Papuan figures and famous world leaders. Similarly, Trafzer et al., (2006) found that Indian children living in boarding schools are increasingly enjoying and learning about moral values through public programmes, meaningful films, and publications. They use the lessons they learn at boarding school to contribute to the well-being of their families, communities, and tribes. The boarding school experience has changed the lives of thousands of Native American children. Boarding school life has a positive impact on the emotional development of students (Vicinus, 1984).

Character education based on local cultural values implemented by the Taruna School in Papua, Indonesia, is the best solution for values and character education for students from inland tribes. Boarding schools train students to be competitive in the future and provide happiness to children from disadvantaged and poor families (Martin et al., 2021; Behaghel et al., 2017;Guo & Chen, 2023). Sekolah Taruna Papua provides good learning services not only with learning facilities, art, prayer, health, and sports services, but all students are given equal access rights in the whole educational process, both in schools and dormitories. This finding is relevant to Tomaševski (2001), who criticised the government for focusing only on the facility needs of boarding schools, but two aspects of rights-based education are often overlooked, namely the acceptability of education and its adaptability to the perspectives of local stakeholders. This concept of character education criticises many boarding schools for prioritising business and economic interests; without paying attention to the value and character education needs of the students. This reality often leads to parents no longer sending their children to boarding schools (Guo & Chen, 2023).

The results of this study also show that the extra-curricular programme is an interesting model of character education and is very popular with students (

Figure 2). Extracurricular activities help to develop students' character in the areas of art, music, sport, and language skills. Sismanto (2023) states that one of the models of character development of students in schools is to integrate character values through extracurricular activities. The same is also emphasised by Dvali (2024b) that the formation of students' personality and character is carried out through a holistic system unity between school learning activities and extracurricular activity programmes (Faizin, 2019).

The results also show that Taruna Papua School provides character education for students through spiritual development. All students are required to pray together before and after activities. The boarding school provides counselling for students with personal problems. Each student takes turns leading worship, scripture reading and deep reflection in both ecumenical work and other spiritual activities. During the holidays, students engage in spiritual camping and tourism and share spiritual experiences among themselves. Some of these activities aim to develop students' character through spiritual development activities. Spirituality is an inherent aspect at every stage of human development and is an integral part of human life. Spiritual life is an essential part and defining character of human beings (Sagala, 2018). Hilmi et al., (2020) asserts that in boarding school life an adolescent can experience spiritual development through his or her increased interest in studying religion. Many boarders study religion as a source of emotional and intellectual stimulation.

One of the advantages of boarding schools is that students' learning outcomes and academic skills improve. Students have regular and scheduled study time. Dormitory assistants supervise and guide them while they study in the study room. In fact, the study found that some indigenous Papuan children can quickly become fluent in English and participate in English speaking competitions at the district and national levels. The findings of this study are emphasized by Martin et al. (2014) that boarding students can receive more continuous professional education than students who do not live in dormitories.

Conclusion

Based on the interviews and textual analysis using the grounded theory approach, six theoretical core concepts of dormitory-based character education for rural and outermost students were identified. The six concepts are personal development, spiritual development, extracurricular activities, clean and healthy lifestyles, learning from inspirational figures, and academic development. The researcher also analysed the relationship between the six-character education models and divided them into two groups, namely internal and external character building. The results of the study provide insights for educators, schools, government, and other stakeholders on different forms of character education models in both schools and boarding settings.

Due to time and cost constraints, external parties such as government, academics, cultural and ethical experts; and other stakeholders were not included in the sampling and respondents. However, the results of this study can be further developed in the form of quantitative research by testing the relationship between the variables found. There are also many studies which show that boarding schools have negative effects on the development of pupils, such as bullying, child sexual abuse, depression, anxiety, truancy and dropping out of school, and some children are still attached to their parents. Some of these problems in boarding schools can be used as topics for future research.

Funding

This article is part of a doctoral dissertation of the first author. The authors would like to thank to the Higher Education Funding Center (BPPT) and The Education Fund Management Institution (LPDP) for sponsoring and funding the research, writing and publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor of this journal and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. The usual disclaimers apply.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this study was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationship that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Althof, W.; Berkowitz, M.W. Moral education and character education: their relationship and roles in citizenship education. J. Moral Educ. 2006, 35, 495–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behaghel, L.; de Chaisemartin, C.; Gurgand, M. Ready for Boarding? The Effects of a Boarding School for Disadvantaged Students. Am. Econ. Journal: Appl. Econ. 2017, 9, 140–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puyo, J.G.B. A Value and Character Educational Model: Repercussions for Students, Teachers, and Families. J. Cult. Values Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, R.; Ben-Artzi, E. The contribution of school climate, socioeconomic status, ethnocultural affiliation, and school level to language arts scores: A multilevel moderated mediation model. J. Sch. Psychol. 2024, 104, 101281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birquier, A. , Krabi, š, -Juber., C., Shegalan, M., and Bond, F. Z. (1998a). Family History: The Impact of Modernization. Yuan, S. R., Shao, J. Y., Zhao, K. F., and Dong, F. B. (eds). Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company. p. 664–665.

- Bourke, L.; Humphreys, J.S.; Wakerman, J.; Taylor, J. Understanding rural and remote health: A framework for analysis in Australia. Heal. Place 2012, 18, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brestovanský, M. Key annual conferences focused on character education in 2023. Dialog- Educ. 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, C.R.; Ihuka, V.C.; Crumb, L. Rural Cultural Wealth in African Education. Int. Educ. Res. 2024, 7, p1–p1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.W. Moral education in Hong Kong kindergartens: An analysis of the preschool curriculum guides. Glob. Stud. Child. 2020, 10, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K.; Thornberg, R. The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, E. Trafzer, Jean A. Keller, and Lorene Sisquo. (2006). Boarding School Blues: Revisiting American Indian Educational Experiences. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basic of Qualitative Research, (): Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; Available online: http://methods.sagepub.com/book/basics-of-qualitative-research (accessed on 25 September 2018)ISBN 978-1-4129-0643-2.

- Creswell, W. John & David J. Creswell. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, Fifth Edition. United Kingdom: SAGE Publications India Pvt. Ltd.

- Curto, V.E.; Fryer, R.G., Jr. The Potential of Urban Boarding Schools for the Poor: Evidence from SEED. J. Labor Econ. 2014, 32, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, P. Problems and Complexities in Rural Schools: Challenges of Education and Social Development. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvali, N. Education of will and character in elementary school. enadakultura 2024, 9, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvali, N. Education of will and character in elementary school. enadakultura 2024, 9, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizin, A. Internalization of Character Values in Pesantren School: Efforts of Quality Enhancement. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Education Innovation (ICEI 2019.

- Foliano, F.; Green, F.; Sartarelli, M. Away from home, better at school. The case of a British boarding school. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2019, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, Mike, at. all. (Ed.) (2002). Character Education: Informational Handbook and Guidefor Supportand Implementation of the Student Citizent Act of 2001. North Garolina: Public Schools of North Garolina.

- Gangloff, Darryl. (2023-April 2024). Seven Benefits of Boarding School https://www.hotchkiss.org/benefits-of-boarding-school.

- Guo, G.; Chen, Y. Lack of family education in boarding primary schools in China's minority areas: A case study of Stone Moon Primary School, Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 985777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamedinasab, S.; Ayati, M.; Rostaminejad, M. Teacher professional development pattern in virtual social networks: A grounded theory approach. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastasari, C.; Setiawan, B.; Aw, S. Students’ communication patterns of islamic boarding schools: the case of Students in Muallimin Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermino, A.; Arifin, I. Contextual Character Education for Students in the Senior High School. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2020, ume-9-2020, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmi, I.; Nugraha, A.; Imaddudin, A.; Kartadinata, S.; Ln, S.Y.; Muqodas, I. Spiritual Well-Being Among Student in Muhammadiyah Islamic Boarding School in Tasikmalaya. ICLIQE 2020: The 4th International Conference on Learning Innovation and Quality Education. pp.1-5.

- Hoge, J.D. Character Education, Citizenship Education, and the Social Studies. Soc. Stud. 2002, 93, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander MP, C. Kartick, J. Gangadhar, P. Vijayachari, Ethno medicine and healthcare practices among Nicobarese of Car Nicobar - an indigenous tribe of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, J. Ethnopharmacol. 158 (2014) 18–24. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.

- Kahane, R. Multicode Organizations: A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of Boarding Schools. Sociol. Educ. 1988, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katanski, Amelia V. (2005). Learning to write “Indian”: the boarding-school experience and American Indian literature. University of Oklahoma Press: Norman.

- Kayange, Grivas Muchineripi. (2023). Character Education Crisis in Modern Africa. Ubuntu Virtue Theory and Moral Character Formation, 1st Edition, Routledge. ISBN. 9781003395683. Character Education Crisis in Modern Africa | 7 | Ubuntu Virtue Theory (taylorfrancis.com).

- Kebede, M.; Maselli, A.; Taylor, K.; Frankenberg, E. Ethnoracial Diversity and Segregation in U.S. Rural School Districts*. Rural. Sociol. 2021, 86, 494–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-G. ; 경상국립대학교윤리교육과교수 The basis of character education programs in future education. J. Ethic- Educ. Stud. 2023, 70, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lickona T, Schaps E and Lewis C. (2002). Eleven Principles of Effective Character Education. Washington, DC: Character Education Partnership.

- Li, J. Grounded theory-based model of the influence of digital communication on handicraft intangible cultural heritage. Heritage Sci. 2022, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, H.; Kang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, Z. The influence of parental involvement on students’ non-cognitive abilities in rural ethnic regions of northwest China. Stud. Educ. Evaluation 2024, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F. Basic education in China’s rural areas: a legal obligation or an individual choice? Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2004, 24, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Villa, K.M. Solution or isolation: Is boarding school a good solution for left-behind children in rural China? China Econ. Rev. 2020, 61, 101456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomawaima, K. T. , & Whitt, S. (2023). Indigenous Boarding School Experiences. In Anthropology. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Marasinghe, S.A.; Sun, Y.; Norbäck, D.; Adikari, A.P.; Mlambo, J. Indoor environment in Sri Lankan university dormitories: Associations with ocular, nasal, throat and dermal symptoms, headache, and fatigue among students. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Burns, E.C.; Kennett, R.; Pearson, J.; Munro-Smith, V. Boarding and Day School Students: A Large-Scale Multilevel Investigation of Academic Outcomes Among Students and Classrooms. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Papworth, B.; Ginns, P.; Liem, G.A.D. Boarding School, Academic Motivation and Engagement, and Psychological Well-Being. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 51, 1007–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, Aynur. ( No. 2, 2011.

- Pangalila, T.; Sumilat, J.M.; Sobon, K. Analysis of Civic Education Learning in The Effort to Internalize The Local Wisdom of North Sulawesi. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 26, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangalila, T.; Sumilat, J.M.; Sobon, K. Learning Civic Education Based on Local Culture of North Sulawesi Society. J. Int. Conf. Proc. 2021, 4, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetio, A. , Anggadwita, G., & Pasaribu, R. D. (2021). Digital Learning Challenge in Indonesia (pp. 56–71). [CrossRef]

- Putra, I.E.; Putera, V.S.; Rumkabu, E.; Jayanti, R.; Fathoni, A.R.; Caroline, D.J. “I am Indonesian, am I?”: Papuans’ psychological and identity dynamics about Indonesia. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 2024, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravet, J.; Mtika, P. Educational inclusion in resource-constrained contexts: a study of rural primary schools in Cambodia. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2024, 28, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.; Green, B. Researching Rural Places. Qual. Inq. 2013, 19, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhman, F.; Hum, M.; Syaifudin, A. ; Yuliati Character Education for Golden Generation 2045 (National Character Building for Indonesian Golden Years). Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 141, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B. Character education in the 21st century. J. Soc. Stud. (JSS) 2019, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagala, Rumadani. (2018). Pendidikan Spiritual Keagamaan: dalam Teori dan Praktik. Yogyakarta: SUKA-Press.

- Sismanto. (2023). Digital transformation of character education model and its implementation for diverse students in Education Technology in the new normal: Now and Beyond, edition1st edition. London: Routledge.

- Stone, A. (2023). Rural student experiences in higher education. In Research Handbook on the Student Experience in Higher Education (pp. 494–505). Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Thomas Lickona. (2015). Educating for character; mendidik untuk membentuk karakter. PT Bumi Aksara: Jakarta.

- Tomaševski, K. (2001). “Human Rights Obligations: Making Education Available, Accessible, Acceptable and Adaptable,” in SIDA (Swedish International Development Agency). Gothenburg: Novum Grafiska AB. p. 1–47.

- Trafzer E, Clifford., Jean A. Keller, and Lorene Sisquo. (2006). Boarding School Blues: Revisiting American Indian Educational Experiences. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.

- UNICEF. (2016). Annual Report Cambodia. Accessed November 2019. https://www.unicef.org/ about/annualreport/files/Cambodia_2016_COAR.pdf.

- Viartasiwi, N. Holding on a Thin Rope: Muslim Papuan Communities as the Agent of Peace in Papua Conflict. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2013, 17, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicinus, M. Distance and Desire: English Boarding-School Friendships. Signs: J. Women Cult. Soc. 1984, 9, 600–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, D.C. & Reimer, L. (2008) Educational priorities and capacity: a rural perspective. Canadian Journal of Education, 31(3), pp. 591- 613. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20466717.

- Yampap, U. The Value of Local Wisdom in the Burning Stone Tradition Through Learning for Character Building of Elementary School Students. KnE Soc. Sci. 2023; 239–254–239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoughts on Aesthetic Character in Music Education. 2023, 5. [CrossRef]

- Yulia, R.; Henita, N.; Gustiawan, R.; Erita, Y. Efforts to Strengthen Character Education for Elementary School Students by Utilizing Digital Literacy in Era 4.0. J. Digit. Learn. Distance Educ. 2022, 1, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S. , and Gao, L. Y. (2018). Can large scale construction of boarding schools promote the development of students in rural area better? J. Educ. Econ. 34, 53–60.

- Yao, Jingyuan. (2022). Discussion on the psychological characteristics and psychological education strategies of higher vocational students. Shanxi Youth, (17), 196-198.

- Zhang, X. , & Tan, X. (2023). Research on the Influencing Factors and Countermeasures of the Formation of “Clique” in College Students’ Dormitory Based on Binary Logistic Analysis (pp. 1015–1021). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Solution or Isolation: Is International Boarding School a Good Solution for Chinese Elites Who Aim to Study Abroad? J. Int. Educ. Dev. 2020, 4, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Feng, Y.; Xu, Y. The impact of boarding school on student development in primary and secondary schools: a meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1359626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J. Y. , and Xu, L. N. (2021). The effect of boarding on Students' academic achievement, cognitive ability, and non-cognitive ability in junior high school. Educ. Sci. Res. 1, 53–59. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Min & Liu Guoshuai. (2022). Research on the practical path of cultural education in university dormitories from the perspective of "Three Complete Education". University Logistics Research, (09), 48-50.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).