Introduction

Indigenous populations in what is now called Canada consist of not only the three distinct groups known as First Nations, Inuit and Métis, but encompasses over 70 languages, unique origin stories, more than 600 Nations, over 3400 reserved land locations, and over 1.8 million people, constituting 5% of the population in Canada [

1]. Indigenous Peoples are not only the fastest growing population segment at over 9% growth, but also the youngest population in Canada where over a quarter are younger than 25 [

1]. This description gives the impression of a vibrant sovereign Peoples thriving within one of the largest and healthiest countries of the world, but the lived reality retains shadows of history routinely experienced in systemic and structural barriers shaping significantly disparate life expectancy rates and blatant access hurdles to equitable healthcare.

The disparate experience of HCV by First Nations provides a clear health problem calling for reflective collaboration and analysis of published literature in connection to current data to inform healthcare solutions. The nuances of maneuvering aspects of culture, science, quantitative data, qualitative perspectives, community-based participatory action research and gaps in available literature necessitated a non-systematic informative review approach combining diverse strategies and a transdisciplinary team of practitioner authors for this article. Through this collaborative synthesis approach the authors seek to increase awareness of the value of context and history in shaping impactful infectious disease strategies.

Methodology

The authors comprise a multidisciplinary group with long experience and expertise in communicable disease epidemiology, public health, infectious diseases, nursing, hepatology and network databases, especially pertaining to Indigenous People. This is not a systematic review. Although Indigenous Peoples are disproportionately impacted by HCV there is a gap in the literature showing inclusion of Indigenous perspectives in HCV initiatives, funding, and programming. A Google Scholar search using the terms ‘Indigenous hepatitis C Canada’ produced approximately 33,200 publications, and a review of the first 200 highlights this gap. Most articles briefly mention Indigenous Peoples as a priority population, many mention data supporting the increased prevalence of HCV in Indigenous Peoples without actually showing the detailed data, several link the current experience of high HCV rates as a colonial legacy, while a few illustrate models of care, connection to culture, or wellness-based initiatives seeking healing or redirection of the current disparaging storylines. We attempted to select those papers on First Nations HCV epidemiology and care pathways that were directly relevant to the themes of this review, or showed original data. We made no attempt at a systematic or comprehensive review given the vast number of incompletely-documented or incompletely-collected papers in this field, especially in the so-called ‘grey literature’ of non-peer-reviewed abstracts and conference proceedings. A PubMed search using the terms ‘First Nation’, ‘hepatitis C’, ‘Canada’ yielded 138 papers. These were reviewed by the authors and included if they contained relevant data or observations.

This review focuses on First Nations populations in the three Prairie provinces, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba (supplementary

Figure 1), because HCV epidemiologic data in Métis and Inuit, especially in other regions of Canada is incompletely or poorly collected/collated.

Original epidemiologic data provided by Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) are reported herein with the permission of the ISC Public Health program.

Colonial Context of Hepatitis C

In the colonizing and settling phase of Canada’s history over 3,400 reserved land locations were set aside to contain First Nations on what are now called reserves, where just over 37% of registered status First Nations people currently live [

1]. Many of these reserves are located in remote areas thus limiting work opportunities, education supports and healthcare access. These gaps in equitable access in reserve communities may influence relocation by many First Nations People to urban centres. First Nations, as co-signatories of the historical and modern treaties reside close to areas of natural resource extraction and are disproportionally affected by environmental degradation and social disruption resulting from the “boom and bust” business cycle, especially after companies maximize profits and move out of the area, often abandoning their responsibilities to support land rehabilitation and creation of sustainable regional development.

These disruptions to land are especially impactful for First Nations who are intimately connected to the land and rely on this connection for physical, mental, social and spiritual wellness. Patterns of subsistence lifestyle, family gatherings, ceremony and spiritual practice are intricately connected to the land and the seasonal cycles of gathering. Reciprocal relationship with natural resources, plant medicines and food sources of specific regions, along with trading routes and meeting points are shaped over generations of reading the land and living in respectful relationship to the land as to a close relative. These relationships and patterns were disrupted, First Nations were removed from traditional lands and the visible and invisible relationship to land-based self-determination and wellness begun in the early colonization era continues today.

Between 1960 and 2023, Canada’s population has more than doubled, while the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) increased more than 50-folds from about 40 billion to 2.1 trillion dollars [

2]. Although this may be seen as growth, it comes at extensive cost to the continuance of the land and violation of the sovereignty of First Nations, the original stewards of the land. The economic development of such a magnitude has required mobilization of large segments of Canadian society and the country’s resources. While this has increased an overall economic participation, it has exacerbated pre-existing socio-economic and income inequality and has come at an unsustainable and tremendous cost to the natural environment and the wellbeing of Indigenous populations.

This ongoing exploitation and colonization of land and its resources builds on the continued experience of colonial and assimilation-based legislation and policies. Starting with broken Treaties between First Nations and the Dominion of Canada, continuing with the Indian Act of 1876, evolving into forced attendance at residential schools and abusive control and abductions of First Nations children through the child welfare system, these actions have shaped the current lived experience for First Nations populations. This daily experience also includes discrimination, marginalization, disruption and transgenerational trauma while creating significant barriers in accessing education, employment, housing, food, security, healthcare services, clean water and sanitation.

These economic, legislative and population dynamics have inflicted a lasting disruption to the use of traditional languages, ways of learning, land-based diet and lifestyle, generational knowledge transfer, spirituality practices, coping strategies and the relational community circle previously experienced. This results in a loss of First Nations Ways of Being of a magnitude nearly impossible to quantify. While the vast and lasting harms of failed assimilation policies are becoming more broadly acknowledged in Canada, the nation-to-nation reconciliation process is still in its infancy.

Institutional Racism in Canadian Healthcare

Institutional or systemic racism can be defined as institutions-driven inequalities that are based on policies or practices that inherently discriminate – either deliberately or not - against one or more population groups [

3]. In practice, systemic racism may be seen as a tendency by one social group to marginalize another social group in a form of exclusion from the application of the federal law [

4] underfunding basic childcare services [

5], creating obstacles to access health services [

4] and otherwise subjecting it to a different standard of service [

4]. Selective application of the law and law enforcement has been implicated in the excessive use of traffic stops of Indigenous Peoples in 2014-2017 [

6] and disproportionate incarceration rates of Indigenous Peoples [

7,

8]. To the latter point, while Indigenous Peoples made up about 5% of the total Canadian Population in 2022, they comprised approximately 32% of the total inmate population in Canada with even higher proportion of Indigenous women in-custody, at approximately 50% of all female inmates in the federal penitentiaries [

7,

8].

Canadian history presents examples of more subtle, but comparably harmful institutional racism policies and practices. One is how First Nations health data has been explicitly misused and appropriated throughout Canadian history to inform colonization processes and to sustain racist policies of subjugation [

9]. By using the Indian Act and the limited representativeness and damaging depictions of First Nations in the health and social data they collected, government agencies and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police “pathologized and took action against [Indigenous communities] in a form of forceful removal of more than 150,000 Indigenous children from their families in the residential school system and the ‘60s scoop’”[

10]. In examining how information about First Nations has been collected and used in the past, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples in Canada concluded that First Nations “have not been consulted about what information should be collected, who should gather that information, who should maintain it and who should have access to it” [

11]. According to a recent report by the First Nations Information Governance Centre in Alberta, Canada, both “the context & purposes of data have historically been determined outside First Nations communities and the misuse of data has led to situations of misappropriation and broken trust” [

9].

Some progress has been made but much more is needed. The publication of the 1996 Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples and the release in 2015 of the Calls to Action by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission [

11,

12], were established to document and inform Canadians about the experiences of First Nations who attended residential schools. The impact of racist colonial policies on the availability, accessibility, timeliness, accuracy and comprehensiveness of health outcome data in First Nations as some of the populations bearing the brunt of the disease burden continues today.

National and jurisdictional (i.e., provincial or territorial) level health reports rarely provide an insight into the burden of disease or treatment outcomes by ethnicity or Indigenous status and not being able to see themselves in the national or provincial/territorial data has been an on-going concern of First Nation organizations in Canada (FNIGC, First Nations Information Governance Centre, 2020,

https://fnigc.ca). Furthermore, lack of disaggregated population-specific disease burden data continues to hamper community-led and community-specific efforts to achieve a meaningful reduction in the burden of nationally notifiable HCV infections. This continued gap calls for action to “redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation” [

12].

The immense loss and disruption experienced by First Nations through acts of colonization and assimilation, when dissociated from culture and relational support strategies, instead becomes a catalyst for coping behaviours which may be deemed harmful and or illegal. This cycle of loss, trauma and ongoing exposure to racism and further harms may exhibit as intergenerational or transgenerational trauma. Harm reduction is often used in reference to supply of clean needles, condoms, legally produced psychoactive substances and structures of medical supervision within a substance use context. But these medical approaches represent only a small part of many evolving distinctions-based culturally-grounded and community-led wholistic wellness activities and initiatives supporting healing for First Nations [

13,

14,

15].

Unfortunately, harm reduction services in several Canadian jurisdictions have been curtailed despite evidence demonstrating positive impact and cost-effectiveness, as well as connecting persons who use substances to health supports, social services and treatment networks [

16]. This approach will exacerbate the toxic drug crises and heighten inequities already experienced by First Nations in obtaining essential services [

16]. Studies in Australia report harm reduction services specifically supporting needle and syringe programming prevented an estimated 96,000 HCV infections and over 32,000 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, thus saving four dollars in direct health care costs for every dollar invested in harm reducing needle syringe programs [

17].

Harm reduction and wellness support activities may assist people in regaining their sense of self-worth, self-determination, and opportunities to re-engage in community. Pursuing individual and community wellness may include revitalization of First Nations languages, countering and preventing institutional and community racism, connecting to the land, traditional harm reduction practices and supporting awareness or prevention strategies. While HIV is still seen as the face of life-altering health outcomes with the potential to impact interactions between family and community, there is a growing appreciation of the similar life-altering impacts of HCV at the personal, family, community, and population levels. These impacts include stigma and self-stigma related to infection with a blood-borne, and / or sexually transmitted infectious disease often associated with substance use and multiple sexual partners, often generating fear and influencing ostracism from family and community. Although HIV may impact various body organs, chronic HCV infection can also impact other organs in addition to cirrhosis, liver cancer, liver failure and death.

Hepatitis C Virus infections in First Nations: A Historical Perspective on the data Systems and Reported Outcomes

HCV is a blood-borne virus whose chronic infection wreaks havoc on liver function, results in more life years lost than any other infectious disease in Canada and creates considerable risk for further liver disease and hepatocellular cancer [

18]. Canadian National Health Surveys are generally not inclusive of the First Nations populations residing on-reserve, Indigenous people within prison populations and under-representative of Indigenous people residing in northern, remote and isolated communities [

19]. This results in national health and social data collection instruments (e.g., Census, national health surveys, etc.) continuously missing the mark with both enumeration of (“the denominator problem”) and collecting outcome data from (“the numerator problem”) First Nations, Metis and Inuit.

There is a paucity of HCV surveillance and clinical outcomes data in Indigenous populations in Canada, especially in Metis and Inuit populations [

20]. In First Nations, HCV surveillance data availability is relatively “better”, though not as comprehensive or timely as it is in the general Canadian population.

A recent comprehensive environmental scan of grey literature and peer-reviewed projects, programs and initiatives in the province of Saskatchewan published between 1995 and 2019 yielded only three HCV-specific academic research results, inclusive of both original research and reviews [

21].

Available surveillance data and peer-reviewed publications describing regional perspectives suggest HCV burden in First Nations communities in Canada has increased over the past 30 years. Between 1993 and 2002, the cumulative positive antibody or anti-HCV incidence rate in First Nations in Manitoba was 91.1 per 100,000 or 2.5 times the respective rate in the non-First Nations individuals in Manitoba at 36.6 per 100,000 [

22,

23]. Between 2010 and 2015, Gordon and colleagues reported anti-HCV incidence rate in First Nations individuals residing in First Nations communities in Northern Ontario between 56.6 per 100,000 in 2010 to 324.2 per 100,000 in 2015 [

24]. In 2015, anti-HCV incidence rate in First Nations in Northern Ontario was 11 times the rate within the general Ontario population for that year [

24]. Younger adults aged 20-29 y.o. made up 45%, while women made up 52% of the HCV antibody-positive population during the study period [

24]. In 2019, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) estimated anti-HCV prevalence in First Nations in Canada at 7.4% with plausibility range of 3.5% to 11.2% of the total First Nations population [

19]. Approximately 3.5% with plausibility range of 2.0% to 5.0% of the total First Nations population in Canada were estimated to live with chronic hepatitis C infection and require treatment. These rates were more than seven times the estimated anti-HCV prevalence and HCV RNA rates in the general Canadian population [

19]. It is of note that the upper bound of this estimate was produced by PHAC in partnership with First Nations Health Services Organizations in Alberta and Saskatchewan and Indigenous Services Canada and released as a part of results of a bio-behavioural survey among First Nations populations in 2018-2020 in the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan [

25].

HCV Surveillance in First Nations in Canadian Prairies

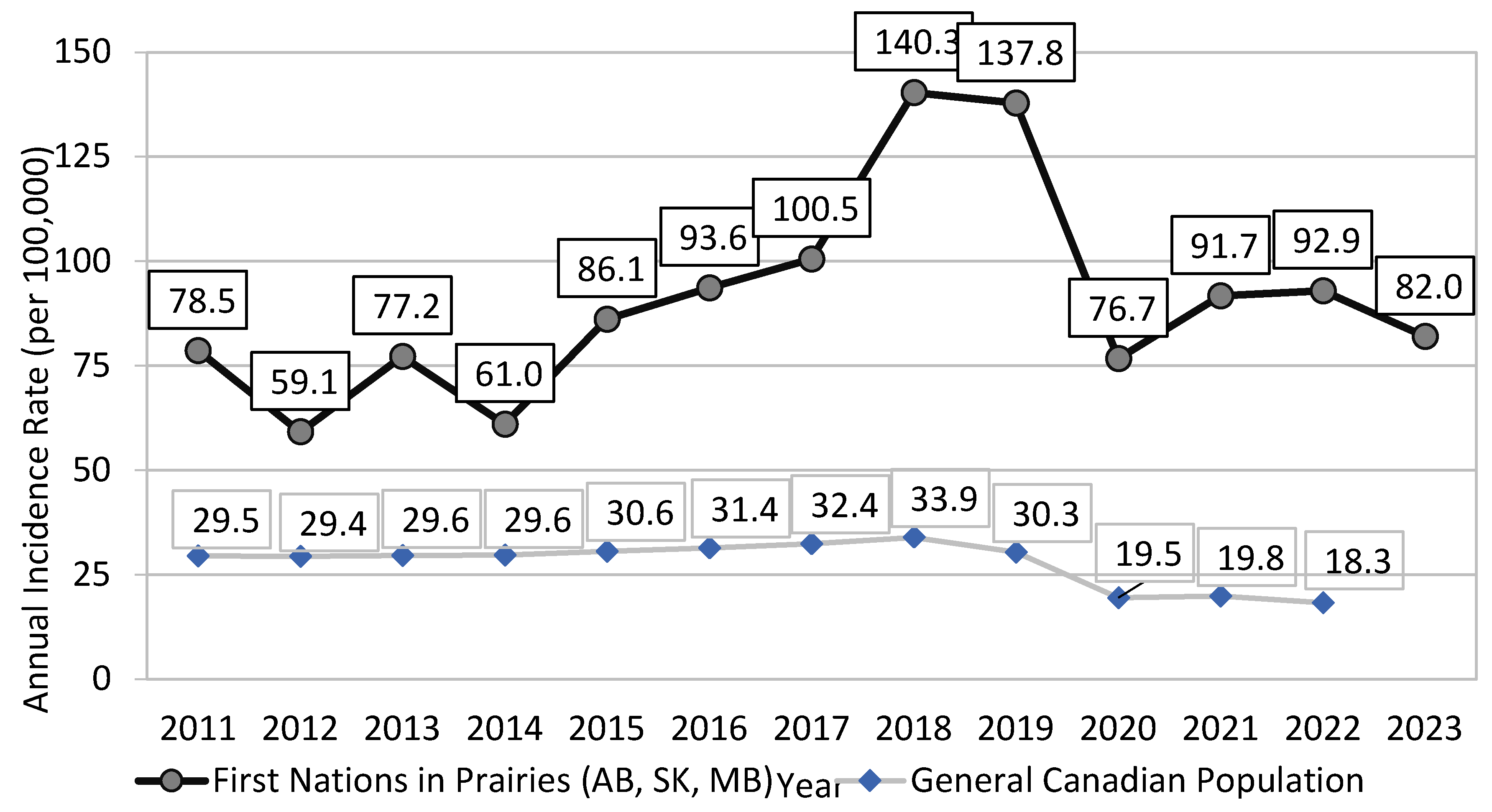

Between 2011 and 2023, the (crude) reported rate of newly diagnosed cases of HCV infection in First Nations communities in the Prairies provinces of Alberta (AB), Saskatchewan (SK) and Manitoba (MB) has almost doubled from 78.5 per 100,000 in 2012 to peaking at 140.3 per 100,000 in 2018 (

Figure 1). By 2023, the reported rate (82.0 per 100,000) was 42% lower than that in 2018 (Indigenous Services Canada, unpublished data, 2024) (

Figure 1).

During the same time, the rate of newly reported cases of HCV infection in the general Canadian population increased only by 15% from 29.5 per 100,000 in 2011 to peaking at 33.9 per 100,000 in 2018 (

Figure 1). By 2022 (the most recent year with available national statistics), the reported Canadian rate of 18.3 per 100,000 was 46% lower than that in 2018 [

26]. The ratio of the reported rates for newly diagnosed HCV infection between First Nations living on-reserve and the general Canadian population has widened from 2.7 in 2011 to 5.1 in 2022 (

Figure 1).

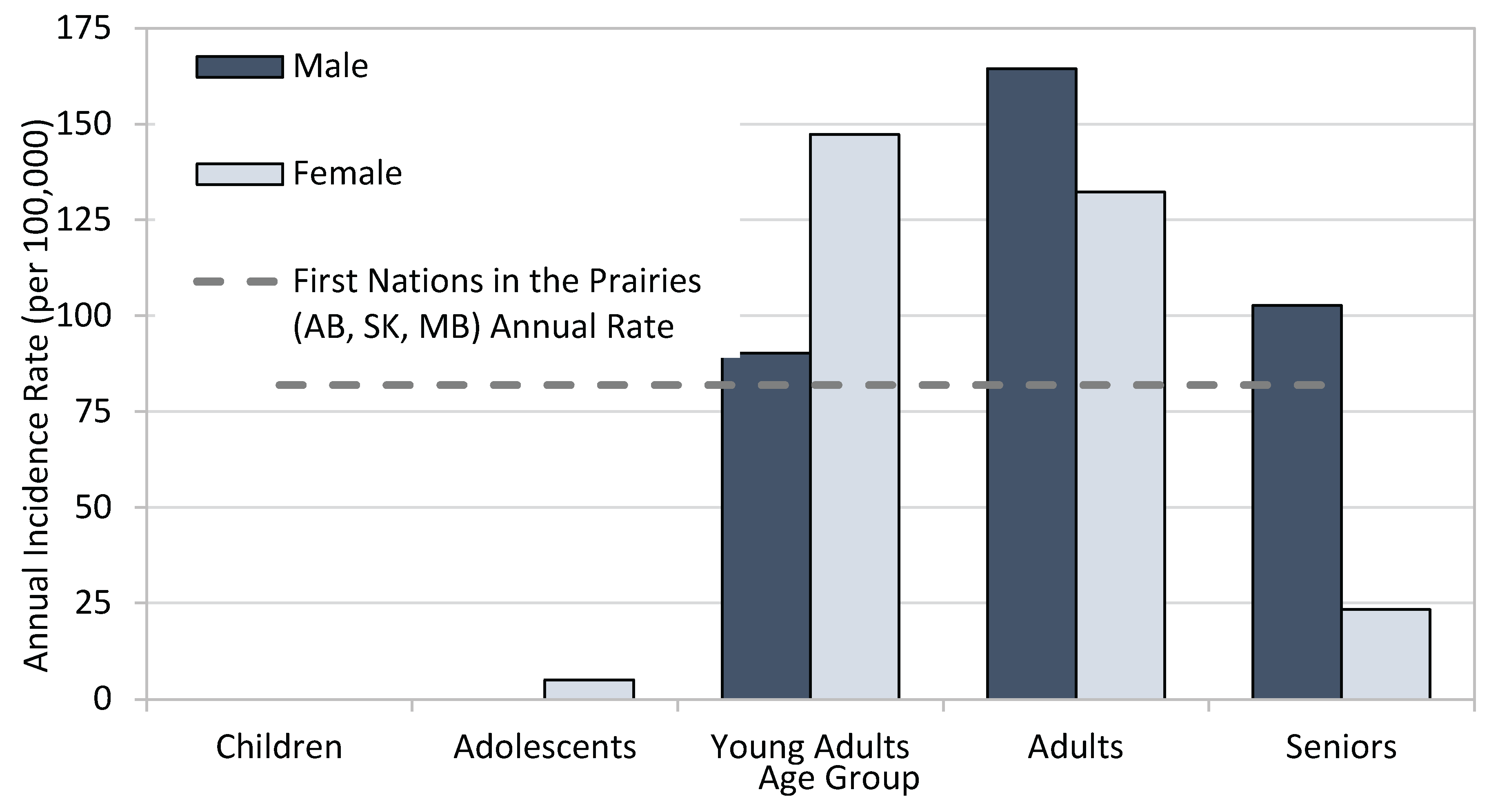

While rates of HCV diagnoses in First Nations males (81.2 per 100,000) and First Nations females (82.8 per 100,000) residing in AB, SK and MB communities were similar in 2023, when stratified by age group and sex, the highest age-specific rate was in younger females and older males, illustrating the need for tailored age- and sex-specific public health interventions (

Figure 2), and highlighting the interconnected issues around power dynamics, partner violence and economic dependence.

For comparison, the reported incidence rate of HCV among males in the general population in Canada for 2020 was 22.9 per 100,000 and the rate among females was 13.7 per 100,000 [

27].

Anti-HCV Status Awareness and Linkage to Care Among First Nations

While estimates of awareness of HCV status in First Nations populations are lacking, a recent national analysis suggested 24% of Canadians with evidence of past or current HCV infection were

not aware of their infection status [

19], while earlier analyses put it between 44% [

28] and 60% [

29]. In 2022, the reported linkage to HCV care among HCV RNA-positive First Nations population in Alberta and Saskatchewan, was approximately 60% [

24].

Sources of HCV Surveillance Data and Data Limitations

As a notifiable disease, all newly diagnosed HCV infections among reporting First Nations communities between 2011 and 2023 were reported to the public health departments. Infections reported between 2020-2022 should be interpreted with caution due to the impact of reallocation of health resources in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in reduced testing for other communicable diseases, including HCV. Aggregate incidence rates are calculated using both case and population counts provided by ISC regional surveillance teams. Data for all three Canadian regions (MB, SK, AB) are included for all reporting years (2011-23).

Regional HCV definitions of HCV infection used were as follows:

- ○

Laboratory-confirmed case–acute: Detection of HCV RNA or detection of HCV antigen (HCV Ag) AND clinical hepatitis (jaundice or peak elevated total bilirubin levels in serum ≥50 µmol/L or peak elevated serum alanine aminotransferase [ALT] >200 IU/L) within six months preceding the first positive HCV test AND negative Hepatitis A IgM antibody (anti-HAV IgM) and negative Hepatitis B core IgM antibody (anti-HBc IgM) AND No other known cause for clinical hepatitis; OR New detection of HCV antibodies (anti-HCV) or HCV RNA or HCV Ag in a patient with previously documented negative anti-HCV or negative HCV RNA within the preceding 12 months.

- ○

Note: Individuals who have achieved complete eradication of the virus, termed sustained virologic response (SVR) after treatment through documented undetectable HCV RNA at least 12 weeks post end-of-treatment (SVR-12), then have a subsequent detectable HCV RNA result within 12 months of SVR-12 date should be considered as having a new acute or recent infection for surveillance purposes, even though these cases may rarely represent late post-treatment relapses.

- ○

Laboratory-confirmed case–chronic: Does not meet criteria for acute or recent infection AND detection of HCV RNA; OR Detection of HCV Ag.

- ○

Confirmed Case: Acute or Recent Infection: Detection of hepatitis C virus antibodies (anti-HCV) or hepatitis C virus RNA (HCV RNA) in a person with discrete onset of any symptom or sign of acute viral hepatitis within 6 months preceding the first positive HCV test AND negative anti-HAV IgM, and negative anti-HBc IgM or HBsAg tests AND serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) greater than 2.5 times the upper normal limit; OR Detection of hepatitis C virus antibodies (anti-HCV) in a person with a documented anti-HCV negative test within the preceding 12 months; OR Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA (HCV RNA) in a person with a documented HCV RNA negative test within the preceding 12 months.

- ○

Confirmed Case: Unspecified (including chronic and resolved infections): Detection of hepatitis C virus antibodies (anti-HCV); OR Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA (HCV RNA).

- ○

Note from region:

the majority of cases are unspecified.

- ○

Confirmed Case: Acute or Recent Infection: Confirmed detection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies (anti-HCV) or hepatitis C virus RNA (HCV RNA) in a person with discrete onset of any symptom or sign of acute viral hepatitis within the previous 6 months of current positive test AND negative anti-HAV IgM and negative anti-HBc IgM or HBsAg test AND serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) greater than 2.5 times the upper normal limit; OR Confirmed detection of hepatitis C virus antibodies (anti-HCV) or HCV RNA in a person with a documented anti-HCV negative test within the preceding 12 months; OR Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA (HCV RNA) in a person with a documented HCV RNA negative test within the preceding 12 months, excluding those undergoing HCV treatment or therapy; OR Individuals who have had a sustained virologic response (SVR) for six months post-treatment and become HCV RNA positive within 12 months of SVR should be considered as having an acute or recent infection for surveillance purposes, even though some of these cases may be post-treatment relapses.

- ○

Confirmed Case: Chronic: Detection of anti-hepatitis C antibodies (anti-HCV) and should be confirmed by a second manufacturer’s EIA, immunoblot or nucleic acid (e.g., PCR) for HCV-RNA; OR Detection of hepatitis C virus RNA (HCV-RNA).

- ○

With AB Chief Medical Officer of Health approval: Died Blood Spot confirmatory testing from the National Micrbiology Laboratory (HCV antibody positive & HCV RNA positive)

Region-specific Data Limitations:

In MB: Case data are sourced from Indigenous Services Canada Regional database and only include newly diagnosed cases of HCV. Population counts are sourced from Status Verification System (SVS). Although the SVS should be a complete list, there are often inaccuracies. For example, if births are not reported in a timely manner, the system will exclude a certain proportion of young children (0-4 years) who are entitled to Status but are currently covered by their parents or remain unregistered for other reasons. Similarly, if deaths are not reported in a timely way, the system will include a certain proportion of deceased individuals. Residency is typically only updated when a life event is reported; therefore the on- and off-reserve designation may not be current. The community population counts for on-reserve will often be an under-estimation of the actual population being served. The on-reserve population count does not include any non-Status community members (i.e., First Nations who are not registered with Indigenous Services Canada and other members of the community who may not be full-time residents (ex. Royal Canadian Mounted Police, nursing staff, educators etc.) for whom the community provides health care services, nor any young children (0-4 years) living in the community who have not yet been registered with ISC.

In SK: Case data are sourced from the provincial database.

In AB: Case data are sourced from Indigenous Canada Regional Database and include only First Nations living in community.

The Colonial Legacy Link and Transmission of HCV

A devastating effect of the colonial legacy in Canada is the disproportionately high prevalence of HCV among First Nations. The simplistic explanation is that First Nations are significantly and disproportionately overrepresented in all the significant behavioral and social determinants or factors that lead to HCV acquisition, including substance use, incarceration, homelessness or crowded housing, non-sterile tattoo or piercing, and other determinants of risk activity for HCV acquisition and transmission. Of these factors the most extensive dataset can be obtained by examining rates of federal and provincial incarceration where Indigenous (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) Peoples are seven-fold more likely than non-Indigenous people to be incarcerated in a federal institution [

30,

31]. In the provincial prisons included in ten provinces, the range varies from approximately two-fold greater incarceration rate in Nova Scotia all the way to a shocking twenty-two-fold in the province of Saskatchewan ([

31], Over-representation of Indigenous persons in adult provincial custody, 2019/2020 and 2020/2021,

Table 1). Beyond the simplistic explanations, examining the root causes of these high incarceration rates shows a disturbing picture of disenfranchisement, discrimination, racism in the justice system, and rupture of traditional social and family supports. Muir et al. [

32] studied a cohort of Indigenous (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) adults in three Ontario cities ranging from smaller, medium-sized and large (Thunder Bay, London, Toronto, respectively). They found that three factors contributed to high rates of incarceration: experiences of racism, removal from and/ or disturbance of family support, and victimization [

32]. Compounding the overrepresentation in determinants of HCV acquisition noted above, other factors sharply exacerbate ongoing HCV transmission: high rates of food insecurity and resulting malnutrition, inadequate access to basic healthcare, lack of HCV awareness and testing, reduced access to curative therapy coexistent with ongoing vectors for continuing horizontal transmission. In their comprehensive review, Fayed and colleagues (2018) exposed colonialism as a “direct determinant of the inequity in HCV burden among Indigenous people…” and provided a pathway for decolonization of HCV care in Canada [

33]. Both the existence of the gaps in HCV burden in First Nations and in availability of health outcomes data on HCV in Indigenous populations in Canada were attributed to the colonial mindset that has been guiding both HCV research and the response to HCV epidemic in Canada to date [

33].

Access to Hepatitis C Testing and Treatment

Direct acting antiviral (DAA) treatment options are available at no cost to eligible Canadians, including First Nations, providing an improved treatment experience for HCV. Although sustained virologic response (SVR) rates after treatment completion in First Nations match those of non-First Nations populations, the rates of engaging in and completing treatment are markedly lower [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Because access to prevention, harm reduction, testing and care varies widely among jurisdictions, the prevalence of HCV varies as well and is reported to be from four to eleven times that of the general population. Variability is evident between First Nations members living off reserve in Ontario, Canada with longer median time from a positive HCV-antibody test result to HCV-RNA testing than individuals living on-reserve (288 days off reserve versus 68 days on reserve) [

39]. It is notable that 17% with a positive HCV antibody do not follow up with the next step to complete the HCV-RNA testing, and of those who do, 60% do not initiate treatment [

39].

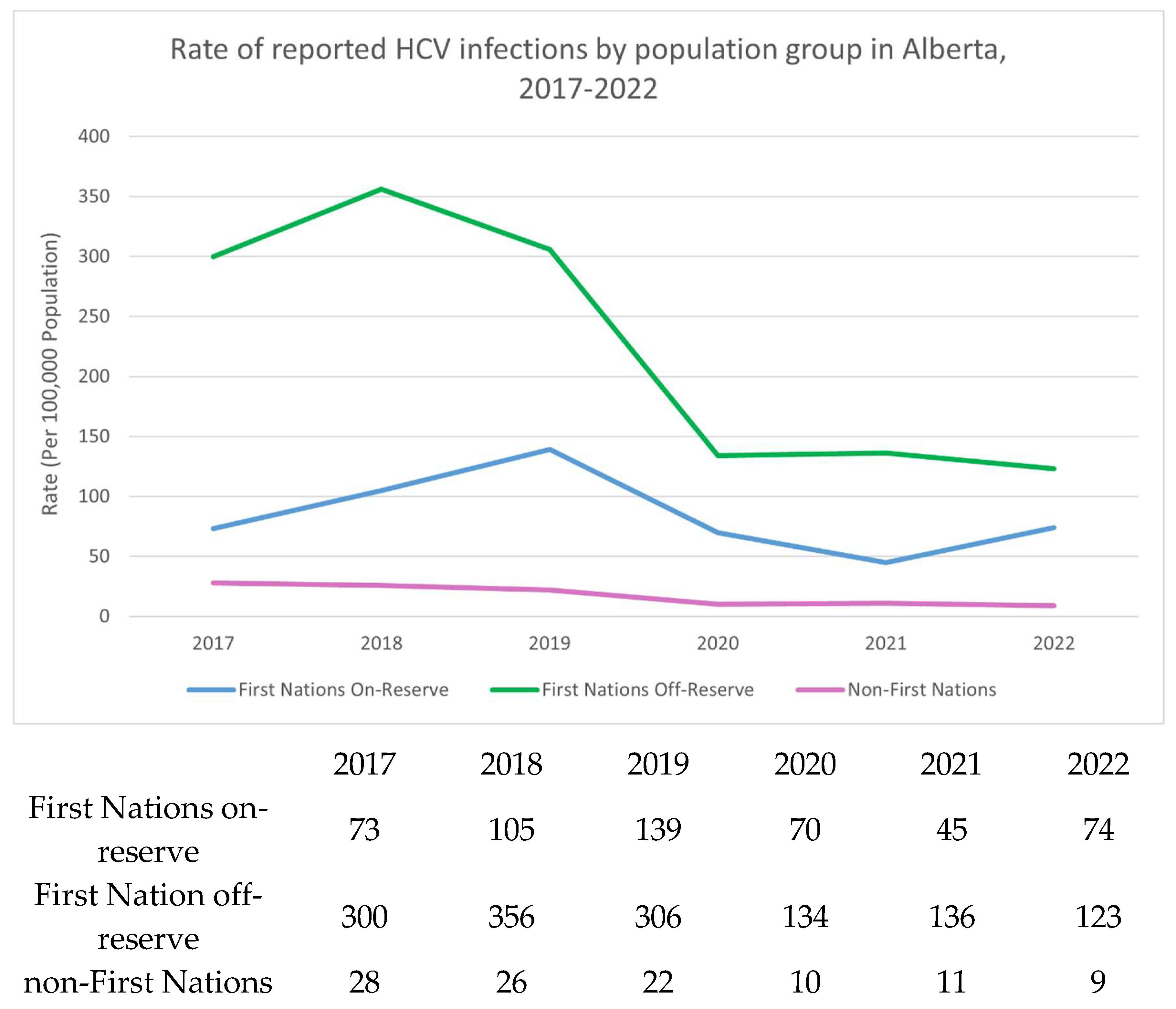

The Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan have limited on-reserve First Nations data. In Alberta, the highest rates of HCV occur in off reserve First Nations People (

Figure 3). The COVID-19 pandemic may have decreased testing, and access to testing in recent years which could explain the recent decrease in HCV incidence. Efforts are underway to increase awareness and access to testing using standard serological testing as well as Dried Blood Spot (finger prick blood droplets placed on card and mailed for laboratory HCV-antibody and RNA processing) and Point of Care Rapid testing.

Figure 3.

Rate of reported HCV infections by population group in Alberta, 2017-2022. Sources: FNIHB AB CDC Database; Government of Alberta, Alberta Health; ISC, Indian Registry.

Figure 3.

Rate of reported HCV infections by population group in Alberta, 2017-2022. Sources: FNIHB AB CDC Database; Government of Alberta, Alberta Health; ISC, Indian Registry.

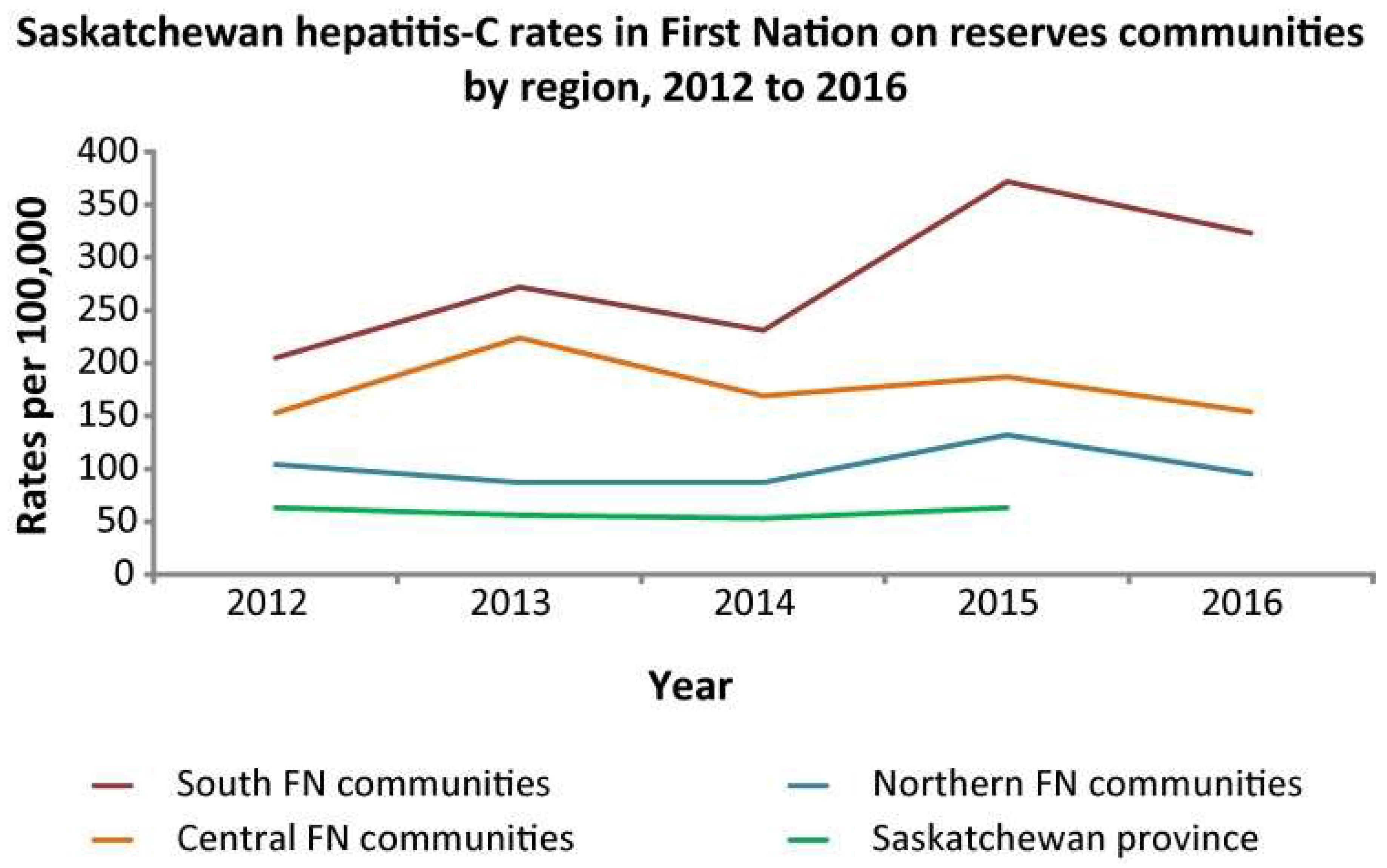

Figure 4.

HCV diagnosis rates in Saskatchewan province per 100,000 population, 2012-2016. Reproduced from Skinner et al. [

40].

Figure 4.

HCV diagnosis rates in Saskatchewan province per 100,000 population, 2012-2016. Reproduced from Skinner et al. [

40].

Geographical factors also contribute significantly to the access to care barrier in First Nations in the Prairie provinces. Most First Nations are small, isolated and remote communities far from large urban centres, and their healthcare clinics suffer from poor infrastructure, facilities and staffing. Thus First Nations persons must often travel significant distances to access laboratory, testing, pharmacies or prescribing physicians or nurse-practitioners. Supplementary

Figure 1 shows all the small First Nations reserves in the three Prairie provinces which have a large land area about the same size as France, Spain, Germany and Italy combined. In Alberta for example, only 18% of the 53 First Nation communities have on-site access to labs, while 36% must drive <30min to a lab, and 46% must drive between 30 min to 3 hr to access lab testing (Dunn KP, unpublished observations, 2022).

Access to specialist physicians who can prescribe curative direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy is also hindered by geographical distance. Although in Alberta, all doctors, nurse-practitioners and even pharmacists can prescribe DAAs, it is the only province in Canada that permits this and in the other provinces and territories, only specialist physicians licenced in gastroenterology, hepatology, infectious disease or addiction medicine can prescribe DAAs. Thus in the other regions of Canada, the Canadian healthcare model of so-called “specialist-driven” medicine where management of conditions such as HCV is done by specialists who only see patients after referral from a generalist physician or nurse-practitioner, leaves many Indigenous patients unable to access curative therapy because their local reserve clinic often has inadequate or only sporadic staffing/visits by physicians and NPs.

Colonial Influence on Experience of Hepatitis

The etiology of the current disparate experience of hepatitis by First Nations populations in Canada cannot be discussed without clear linkage to colonial disruptions that continue to the present time. The Indian Act of 1876, although enacted in the last century with the intent to terminate Indigenous culture and the social, political and economic relationships shaping distinct Indigenous Peoples, continues to dictate the funding and governance structure for health, education, lands, and leadership. Indigenous People living through, or having family members who experienced the colonizing disruptions and confines of forced attendance in residential school, being removed from their family by the child welfare system, or experiencing the injustices of the judicial system where we see a disparate number of Indigenous Peoples incarcerated, continues to impact not only current physical, mental, emotional and spiritual wellbeing but also disruption of interpersonal relationships in the next generations, increased rates of numerous infectious and chronic diseases, and the draw to addictions as coping mechanism as seen through multiple generations [

33,

41].

Research with Indigenous young people conducted in British Columbia showed a significant association between childhood maltreatment (residential school, child welfare system, foster care, sexual abuse) and HCV infection [

14]. Many of the socio-economic systems in Canada conceived at the time of the Indian Act still influence healthcare services development, and access to it as evidenced by the reticence of Indigenous communities and community members to engage in HCV treatment [

37,

38,

42].

Progress Toward HCV Elimination by 2030 in First Nations

Efforts toward the World Health Organization (WHO) goal of hepatitis elimination as a public health threat by 2030 outlined in the

Blueprint to Inform Hepatitis Elimination Efforts identify priority populations as: People who are incarcerated (PWI); People who inject drugs (PWID); Indigenous Peoples (First Nations, Inuit & Métis); Gay, Bisexual and other men who have sex with men; Newcomer and Immigrants from countries with high prevalence rates; and people born between 1945-1975 [

42]. Over-representation of Indigenous Peoples (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) is evident in several of these priority populations, skewing not only the data but also the stigma [

43,

44]. By identifying Indigenous populations as a priority group are we actually supporting health equity or further stigmatizing an already heavily stigmatized population group? Among PWUD we must consider the socio-demographics within 28% of that group who also identify as Indigenous [

44]. The dual or intersectional stigma of racism, and HCV status, or identification with more than one of the priority population groups not only complicates the personal experience of interactions with healthcare systems but often compounds self-stigma, which may be seen in non-commitment to testing, treatment or as loss to follow-up [

40,

43,

45]

These problems of stigmatization combined with lack of community awareness, the asymptomatic nature of chronic HCV infection, poor healthcare facilities and staffing, lack of funding and geographical remoteness have combined to severely curtail any real prospect of HCV elimination by 2030 in First Nations.

Recent modelling analysis [

46] indicates that most Canadian provinces except Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec are on track to meet the WHO 2030 target, but the specific subpopulations of First Nations persons in these provinces was not addressed because data were lacking, although those authors commented that Indigenous populations across Canada represent a subgroup that is very unlikely to achieve the elimination target by 2030 [

46]. In part this is because the above factors dramatically reduce HCV testing and thus an unknown percentage, but likely large percentage if not the majority, of Indigenous HCV-infected persons are unaware of their infection. As with all other populations, the COVID pandemic severely reduced the number of cases tested and detected [

46].

Strategies for Change Through Promising Practice

Within the context of HCV, there continues to be gaps in equity, access, supports, and culturally competent care. However, especially over the past decade or so, significant changes and improvements have started, or are in progress. In many respects this is part of a greater societal change spurred by a very belated recognition of the harms, injustices and inequities suffered by Indigenous people over the past five centuries. In particular the Truth and Reconciliation Commission [

12] has shed light on many of these issues and made a number of recommendations to address them. Canada has passed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act that received Royal Assent in 2021, which sets out that “the minimum standards for the survival, dignity and well-being of Indigenous Peoples of the world” must be implemented in Canada [

47]. Priority populations require unique priorities which include recognition, respect, relationships, and reconciliation efforts alongside concerted focus supporting cultural perspectives on wellness [

47,

48].

In terms of healthcare and with specific reference to HCV diagnosis and management, a number of important initiatives are underway. Increasing the representation of First Nations, Inuit and Métis in the Canadian health workforce in response to the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Calls to Action [

12] will help foster trust and therapeutic alliance to improve health outcomes through the cascade of HCV prevention, treatment and care. First Nations patients may be more comfortable accessing care with First Nations health providers raising the priority need to increase First Nations health initiatives at medical and nursing schools, while supporting cultural safety training and First Nations health workforce development alongside Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada, Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association, Office of Indigenous Health at the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, the Indigenous Health Committee at the College of Family Physicians of Canada and Indigenous Services Canada.

Addressing social determinants of health while expanding First Nations health workforce alongside continued development and mobilizing of: telehealth options, supporting remote access to HCV diagnosis and therapy, mobile outreach services, Dried Blood Spot testing, rapid Point of Care testing for antibody and viral load, as well as innovations such as at-home testing, and assessing current bureaucratic hurdles to lab diagnosis and treatment payment/reimbursement. Funding, training, and capacity supports must be provided to support increased awareness of HCV and confidence to treat among primary care providers and community health infrastructure supporting First Nations populations. Specialists in urban centres can build treatment pathways supporting virtual access to culturally aware and low barrier testing and treatment. Increasing access to HCV prevention and management through primary care supports, substance use prevention, harm reduction programming, addiction treatment and recovery supports, supporting distinctions-based self-determined solutions led by and with First Nations are collective contributions to HCV elimination efforts.

Creating a supportive environment for Substance Use Disorders recovery, or a Recovery Capital approach, can be a useful model, which by definition includes internal and external resources that can be drawn upon to initiate and sustain recovery. Such approaches go beyond clinical approaches, and include family and community capital in shaping a healing environment to support long-term success [

42,

49].

Culturally connected resources to increase awareness and support prevention are integral to improving access. It is imperative to co-create multidisciplinary care supports focusing on competing psychosocial needs and social issues faced daily by equity-denied populations while allocating priority funding explicitly supporting cultural inclusion, wellness-based approaches and community-wide initiatives designed and led by Indigenous People [

50,

51,

52].

There are several examples across Canada where efforts are underway to provide connected care models. The Alberta ECHO program supports virtual access to a prescribing hepatologist for liver disease consults and HCV treatment in remote First Nations and Métis communities [

50,

52]. Through care conversations with Indigenous health care providers in Alberta the need for relevant HCV awareness resources was raised and First Nations Knowledge Keepers collaborated to co-create and produce a DocuStory film showcasing HCV awareness through a liver wellness narrative approach [

53].

Feedback from First Nations and Métis communities in Alberta requesting increased access to HCV testing, prioritized policy change facilitating Dried Blood Spot testing as an option offering destigmatizing and low-barrier testing for multiple health concerns including HCV-antibody and HCV RNA through a finger prick that can be performed without extensive medical training [

54]. This creates testing options for home use, health fairs, mass screening, anywhere a lab is not readily accessible, or to create an option for those who do not access mainstream healthcare facilities while providing an opportunity to build relationship, reconnect for results, and support wellness. Nurse-led programs across Canada provide exemplary opportunities for engagement and patient engagement relationship that support high levels of HCV testing and treatment success [

55]. Saskatchewan has co-created multi-disciplinary community-led models focusing on de-stigmatization and increasing access to the HCV treatment path utilizing a mentored connection [

56]. British Columbia co-created a ‘seek and treat’ model for micro-elimination working through nurses who visited people and their friend- or family-connections in their supportive housing sites to provide HCV treatment path services such as testing and treatment [

57].

Addictions medicine and urban supportive care centres are also including HCV awareness, prevention, testing and treatment alongside social supports and harm reduction approaches to provide wrap-around supports in many settings including Calgary, Alberta [

58] Toronto, Ontario [

55] and Vancouver, British Columbia [

57]. Building relational and wellness supports for people impacted by the correctional system in Canada is also the focus of initiatives to provide testing, treatment or linkage to care [

59]. Although these programs may not be Indigenous-led they are seeking connected models of care that provide wellness supports that engage Indigenous Peoples within urban populations. There are also Indigenous-led efforts supporting destigmatization and wholistic perspectives across Canada. An example is the work of Kimamow Atoskanow Foundation in Alberta, Canada [

60] shaping rural and land-based supports around wellness and cultural teachings on sexual health. Communities, Alliances and Networks (CAAN) is an Indigenous-led organization partnering with funders and national stakeholders to support HCV and HIV community readiness resources, education, funding, and programming [

61].

Momentum for change includes creation of several Indigenous-led community organizations, initiatives, and collaborative co-developed community engagement and education resources. The initiatives mentioned here are by no means a comprehensive list, instead these examples are mentioned as a means to inspire consideration of potential for Indigenous-led advocacy in impacting current policy, inadequate data availability, and initiating or supporting community-based programming.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this review. First, as acknowledged in the Methodology section, data in the Inuit and Métis populations is significantly lacking or incompletely collected, thus our original intent to review the entire Indigenous HCV epidemiology was not feasible. Accordingly, this review only focuses on First Nations. But this underscores the pressing need to collect accurate data on the epidemiology and management of HCV in Inuit and Métis in Canada. Moreover there are significant gaps even in First Nations data. Specifically as detailed in the sections above of the epidemiology of HCV in each Prairie province, a number of knowledge gaps remain. A persistent knowledge gap is the exact geographical distribution of First Nations People with HCV, specifically whether they live on reserve or off reserve. Many papers in the literature are also perhaps slightly inaccurate because First Nations status was not verified through the Indian Registration system due to privacy concerns, but was instead through self-identification. Again, as mentioned previously, First Nations data in other regions of Canada are less completely collected and thus we have limited this review to the three Prairie provinces. These provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba contain the largest proportions of self-reported Indigenous People, at 7%, 17% and 18% of the total populations of each province, according to the 2021 Canadian census [

1]. Overall in Canada, 5% of the population self-identifies as Indigenous [

1]. Thus our review in these regions where Indigenous People comprise a relatively larger segment of the population may not be directly applicable to provinces such as Ontario where they comprise only 2.5% of the population [

1].

Finally, the literature shows a significant gap in that much of it is written by non-Indigenous authors. There is a significant paucity of HCV studies led by Indigenous authors representing the First Nations perspectives on issues such as epidemiology, care pathways, destigmatization, barriers to treatment, culturally relevant engagement practices, etc. Moreover, few studies include the perspectives of First Nations persons with lived experience of HCV. We hope that future studies will take note of these gaps and attempt to address them.

Conclusions

The high rates of HCV prevalence and annual incidence in First Nations in Canada are a legacy of the colonial trauma of the past that continues in many respects to the present day. First Nations are overrepresented in most of the behavioral determinants that lead to HCV acquisition. These include substance use, incarceration, homelessness, and substantial barriers to culturally safe prevention, high quality testing, curative DAA therapy and care. As the data indicates, there are regional variations so focused strategies are needed. Furthermore, there are specific needs to provide interventions for young Indigenous females, who appear to be disproportionately impacted. Many opportunities exist for improving the relationship between the justice system, police services, corrections infrastructure and First Nations to address the racism, inequity and abuses both in judiciary policy as well as improving healthcare access and HCV treatment access within these structures.

In recent years, there has been widespread acknowledgment by non-Indigenous people and levels of government that Indigenous Peoples have suffered and continue to suffer from racism, discrimination and disenfranchisement. Along with this, there are now many proclamations, projects and plans to start addressing these inequities in a meaningful manner.

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that Indigenous communities can implement focused in-community testing for infectious diseases, and localized approaches are effective at educating community members on health topics as well as conducting screening and providing personal and supportive wholistic care. It is also striking how the factors affecting initial engagement in care and retention in supportive care, are the pivotal piece in contributing to achieving SVR. We are hopeful that these important measures will eventually result in elimination of HCV in First Nations in Canada.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: KPRD, SSL. Literature review: KPRD, DW, MT, CS, TW. Data acquisition: DW, MT, CS. Data analysis: all authors. Writing first draft: all authors. Intellectual input and revision of draft: all authors. Final approval for submission: all authors.

Funding Information

This work was not funded by any outside agency.

Ethics Statements

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

We gratefully and respectfully acknowledge that we live and work on traditional lands of Indigenous People across what is now Canada. We are grateful for opportunities to learn from Indigenous Ways of Knowing, Being, Doing and Connecting as Indigenous Science and respectfully seek to build capacity within healthcare toward inclusion of these perspectives.

Conflict of Interest

KPRD: speaking or consulting fees from Abbvie, Gilead, SRx Pharmacy, CATIE, Canadian Liver Foundation, International conference on Hepatitis and health in Substance Users (INHSU); DW: nil to declare; MT: employee of Government of Canada (Indigenous Services Canada); CS: employee of Government of Canada (Indigenous Services Canada); TW: employee of Government of Canada (Indigenous Services Canada); HL: nil to declare; SSL: Speaking or consulting fees from: Abbvie, Gilead, Grifols, Jazz, Mallinckrodt, Oncoustics, and Justice Canada (HCV ‘Tainted Blood’ file)

Abbreviations:

DAA: direct-acting antiviral

ECHO: Extension for community health outcomes

HCV: hepatitis C virus

FN: First Nations

ISC: Indigenous Services Canada

PHAC: Public Health Agency of Canada

PWUD: persons who use drugs

SVR: sustained virological response

WHO: World Health Organization |

References

- Government of Canada. Statistics on Indigenous peoples [Internet]. www.statcan.gc.ca. 2019. Available from: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/subjects-start/indigenous_peoples.

- World Economics. Canada | GDP | 2021 | Economic Data [Internet]. World Economics. 2023. Available from: https://www.worldeconomics.com/Country-Size/canada.aspx.

- Souissi, T. Systemic Racism in Canada | The Canadian Encyclopedia [Internet]. www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. 2022. Available from: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/systemic-racism.

- Daniels, v. Canada (Indian Affairs and Northern Development), 2016 SCC 12 (CanLII) [Internet]. Canlii.org. CanLII; 2016. Available from: https://www.canlii.org/en/ca/scc/doc/2016/2016scc12/2016scc12.html.

-

https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/2698184/Jugement.pdf.

-

https://rapportspvm2019.ca/rapport/SPVM%20Stats_2019_ANG_FINAL.pdf.

- Government of Canada O of the AG of C. Report 4—Systemic Barriers—Correctional Service Canada [Internet]. www.oag-bvg.gc.ca. 2022. Available from: https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_oag_202205_04_e_44036.html.

- Over-representation of Indigenous persons in adult provincial custody, 2019/2020 and 2020/2021.

- Mcbride, K. Data Resources and Challenges for First Nations Communities Document Review and Position Paper Prepared for the Alberta First Nations Information Governance Centre [Internet]. Available from: https://afnigc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Data_Resources_Report.pdf.

-

https://oci-bec.gc.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/Annual%20Report%20EN%20%C3%94%C3%87%C3%B4%20Web.pdf.

- The Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (PRB 99-24E) [Internet]. publications.gc.ca. Available from: https://publications.gc.ca/Collection-R/LoPBdP/EB/prb9924-e.htm.

- Government of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action [Internet]. publications.gc.ca. 2015. Available from: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-8-2015-eng.pdf.

- Pearce ME, Jongbloed K, Demerais L, et al. “Another thing to live for”: supporting HCV treatment and cure among Indigenous people impacted by substance use in Canadian cities. International Journal of Drug Policy 2019, 74, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce ME, Jongbloed K, Pooyak S, et al. The Cedar Project: exploring the role of colonial harms and childhood maltreatment on HIV and hepatitis C infection in a cohort study involving young Indigenous people who use drugs in two Canadian cities. BMJ open 2021, 11, e042545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granfield R, Cloud W. Coming clean : overcoming addiction without treatment; New York University Press: New York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, P. Canadian provinces scaling back harm-reduction services. Lancet 2024, 404, 1509–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research Return on investment 2: Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of needle and syringe programs in Australia [Internet]. 2009. Available from: https://www.acon.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Evaluating-the-cost-effectiveness-of-NSP-in-Australia-2009.pdf.

- Shoukry NH, Feld JJ, Grebely J. Hepatitis C: A Canadian perspective. Canadian Liver Journal 2018, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic N, Williams A, Perinet S, et al. National Hepatitis C estimates: Incidence, prevalence, undiagnosed proportion and treatment, Canada, 2019. Can Commun Dis Rep 2022, 48, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rempel JD, Uhanova J. Hepatitis C virus in American Indian/Alaskan Native and Aboriginal peoples of North America. Viruses 2012, 4, 3912–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Canto, S. & Ali F. HIV and Hepatitis C Programs, Projects, and Initiatives in Saskatchewan: Environmental Scan. Technical Report, Saskatchewan HIV Research Endeavour (SHARE). Available at: https://sidcn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Tech-Report-FINAL.pdf.

- Uhanova J, Tate RB, Tataryn DJ, et al. The epidemiology of hepatitis C in a Canadian Indigenous population. Can J Gastroenterol 2013, 27, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadler MD, Lee SS. Hepatitis C virus infection in Canada’s First Nations people: a growing problem. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013, 27, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon J, Bocking N, Pouteau K, et al. First Nations hepatitis C virus infections: Six-year retrospective study of on-reserve rates of newly reported infections in northwestern Ontario. Canadian Family Physician. 2017, 63, e488–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lydon-Hassen K, Jonah L, Mayotte L, et al. Summary findings from Tracks surveys implemented by First Nations in Saskatchewan and Alberta, Canada, 2018–2020. Can Commun Dis Rep 2022, 48, 146–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/report-hepatitis-b-c-canada-2018.html.

-

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/hepatitis-c-canada-2020-surveillance-data-update.html.

- Trubnikov M, Yan P, Archibald C. Hepatitis C: estimated prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in Canada, 2011. Canada Communicable Disease Report 2014, 40, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotermann M, Langlois K, Andonov A, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections: Results from the 2007 to 2009 and 2009 to 2011 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Health Rep. 2013, 24, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Singh D, Prowse S, Anderson M. Overincarceration of Indigenous people: a health crisis. CMAJ 2019, 191, E487–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Bempah A, Kanters S, Druyts E, et al. Years of life lost to incarceration: inequities between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians. BMC public health 2014, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Muir NM, Rotondi M, Brar R, et al. Our Health Counts: Examining associations between colonialism and ever being incarcerated among First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people in London, Thunder Bay, and Toronto, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2013, 1–4.

- Fayed ST, King A, King M, et al. In the eyes of Indigenous people in Canada: exposing the underlying colonial etiology of hepatitis C and the imperative for trauma-informed care. Canadian Liver Journal 2018, 115-29.

- Robinson P et al., Statistics Canada, released July 12, 2023.

- Nitulescu R, Young J, Saeed S, et al. Variation in hepatitis C virus treatment uptake between Canadian centres in the era of direct-acting antivirals. International Journal of Drug Policy 2019, 65, 41–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil CR, Buss E, Plitt S, et al. Achievement of hepatitis C cascade of care milestones: a population-level analysis in Alberta, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2019, 110, 714–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Paredes D, Amoako A, Ekmekjian T, et al. Interventions to improve uptake of direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus in priority populations: a systematic review. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022, 24, 10–877585. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar P, Corsi DJ, Cooper C. Distribution of hepatitis C risk factors and HCV treatment outcomes among Central Canadian Aboriginal. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2016, 2016, 8987976. [Google Scholar]

- Mendlowitz AB, Bremner KE, Krahn M, et al. Characterizing the cascade of care for hepatitis C virus infection among Status First Nations peoples in Ontario: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2023, 195, E499–E512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner S, Cote G, Khan I. Hepatitis C virus infection in Saskatchewan First Nations communities: Challenges and innovations. Can Commun Dis Rep 2018, 44, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe-Markman C, Lea KD, McCabe C, et al. Social values for health technology assessment in Canada: a scoping review of hepatitis C screening, diagnosis and treatment. BMC Public Health. 2020, 20, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Blueprint to inform hepatitis c elimination efforts in canada [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 28]. Available from: https://www.canhepc.ca/sites/default/files/media/documents/blueprint_hcv_2019_05.pdf.

- Krajden M, Cook D, Janjua NZ. Contextualizing Canada’s hepatitis C virus epidemic. Canadian Liver Journal. 2018, 1, 218–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zietara F, Crotty P, Houghton M, et al. Sociodemographic risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection in a prospective cohort study of 257 persons in Canada who inject drugs. Canadian Liver Journal. 2020, 3, 276–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako A, Ortiz-Paredes D, Engler K, et al. Patient and provider perceived barriers and facilitators to direct acting antiviral hepatitis C treatment among priority populations in high income countries: A knowledge synthesis. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2021, 96, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld JJ, Klein MB, Rahal Y et al. Timing of elimination of hepatitis C virus in Canada’s provinces. Can Liver J. 2022, 5, 493–506. [Google Scholar]

- Branch, LS. Consolidated federal laws of Canada, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act [Internet]. laws-lois.justice.gc.ca. 2021. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/u-2.2/FullText.html.

- Joseph RPC, Joseph CF. Indigenous relations: insights, tips & suggestions to make reconciliation a reality. Indigenous Relations Press: Port Coquitlam, BC, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço L, Kelly M, Tarasuk J, et al. The hepatitis C epidemic in Canada: an overview of recent trends in surveillance, injection drug use, harm reduction and treatment. Canada Communicable Disease Report 2021, 47, 505–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn KP, Williams KP, Egan CE, et al. ECHO+: Improving access to hepatitis C care within Indigenous communities in Alberta, Canada. Canadian Liver Journal 2022, 5, 113–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granfield R, Cloud W. Coming clean : overcoming addiction without treatment. New York: New York University Press, 1999.

- Dunn KP, Oster RT, Williams KP, et al. Addressing inequities in access to care among Indigenous peoples with chronic hepatitis C in Alberta, Canada. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2022, 7, 590–2. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KP, Hayes GW. ©NandaGikendan. Wholistic Conversations on Liver Wellness [Internet]. Vimeo. 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 19]. Available from: https://vimeo.com/838428539.

- Young J, Ablona A, Klassen BJ, et al. Implementing community-based Dried Blood Spot (DBS) testing for HIV and hepatitis C: a qualitative analysis of key facilitators and ongoing challenges. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1085. [Google Scholar]

- Lettner B, Mason K, Greenwald ZR, et al. Rapid hepatitis C virus point-of-care RNA testing and treatment at an integrated supervised consumption service in Toronto, Canada: a prospective, observational cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health–Americas 2023, 22.

- Pandey M, Konrad S, Reed N, et al. Liver health events: an indigenous community-led model to enhance HCV screening and linkage to care. Health promotion international 202, 37, daab074.

- Bartlett SR, Wong S, Yu A, et al. The impact of current opioid agonist therapy on hepatitis C virus treatment initiation among people who use drugs from the direct-acting antiviral (DAA) era: a population-based study. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2022, 74, 575–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe K, Gale N. Shelter-based hepatitis C treatment at the Calgary Drop-in Centre [Internet]. CATIE - Canada’s source for HIV and hepatitis C information. 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.catie.ca/programming-connection/shelter-based-hepatitis-c-treatment-at-the-calgary-drop-in-centre.

- Kronfli N, Dussault C, Bartlett S, et al. Disparities in hepatitis C care across Canadian provincial prisons: Implications for hepatitis C micro-elimination. Canadian Liver Journal 2021, 4, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimamow Atoskanow Foundation – We All Work Together [Internet]. Treeofcreation.ca. 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 19]. Available from: https://treeofcreation.ca/.

- Home - CAAN: Empowering Indigenous Communities | HIV/AIDS Support, Education, and Advocacy in Canada [Internet]. CAAN: Empowering Indigenous Communities | HIV/AIDS Support, Education, and Advocacy in Canada. 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.caan.ca/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).