1. Introduction

Artificial sweetener (AS), also referred to as non-nutritive sweeteners, was developed as substitutes for sugar. In comparison to conventional sweeteners such as sucrose and fructose, AS are characterized by their high sweetness, low energy content, and good stability. Their ability to reduce sugar intake is believed to help prevent dental caries and obesity, making them a potential dietary option for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). However, their effects on T2DM remains uncertain, with several studies indicating that AS intake was associated with increased risk of T2DM [

1,

2]. Currently, several common AS, including aspartame, acesulfame K, sucralose, and saccharin, have received approval from various organizations, including the European Union and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These sweeteners are widely utilized in the production of everyday foods such as soda, bread, and pastries.

The safety of AS consumption during pregnancy has long been a subject of public health interest, with previous observational studies providing mixed results on its association with adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs) such as preterm delivery, low birth weight, and gestational diabetes[

3,

4,

5,

6]. The inherent limitations of observational studies, including confounding factors and reverse causation, necessitate a more robust methodological approach to clarify these associations.

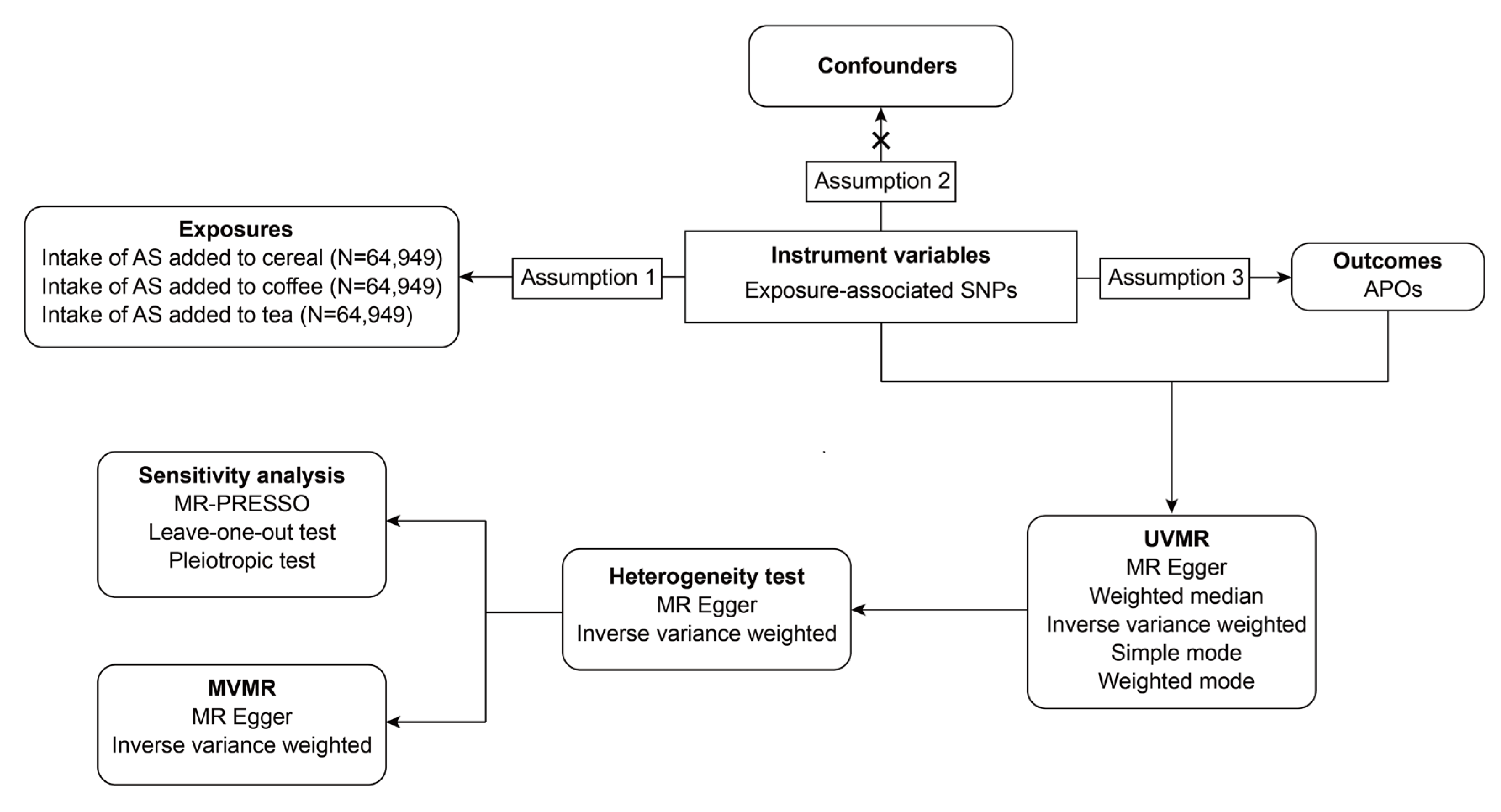

Mendelian randomization (MR) offers an alternative by using genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) under three core assumptions to assess causality in the relationship between exposures and outcomes. Our study aims to dissect these relationships further, providing evidence that may inform dietary recommendations for pregnant women and contribute to better pregnancy outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

A two-sample MR analysis was conducted to evaluate the causal relationship between the intake of AS from various sources and APOs. This study adhered strictly to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Using Mendelian Randomization (STROBE-MR) statement and followed the corresponding checklist. Participant consent and ethical approval were obtained in the original studies. An overview of the flowchart is presented in

Figure 1.

Data source

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) summary data for exposure were obtained from the IEU Open GWAS Project[

7] (v8.5.2,

https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/). Data on the intake of AS added to cereal, coffee, and tea were based on a GWAS involving 64,949 European participants. Answers to the questions including "How much sweetener (e.g., Canderel) did you add to your cereal or porridge (per bowl)?", "How many teaspoons/tablets of sweetener (e.g., Canderel) did you add to your coffee (per drink)?", and "How many teaspoons/tablets of sweetener (e.g., Canderel) did you add to your tea/infusion (per drink)?" were collected from the participants. Their responses included options of half, 1, 2, 3+, or varied. Data on BMI and T2DM, derived from self-reports, encompassed 336,107 and 462,933 European individuals, respectively. Data on fasting glucose were obtained from the Meta-Analysis of Glucose and Insulin-related Traits Consortium (MAGIC), which included 133,010 European individuals[

8]. Measures of fasting glucose taken from whole blood were adjusted to plasma levels using a correction factor of 1.13[

9]. GWAS summary data for APOs were sourced from the FinnGen and GWAS Catalog consortium[

10,

11]. The outcome traits included ectopic pregnancy, excessive vomiting in pregnancy, gestational diabetes mellitus, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, medical abortion, preeclampsia, pregnancy hypertension, premature rupture of membranes (PROM), preterm birth, spontaneous abortion, placental disorders, placenta previa, abruptio placenta pre-eclampsia or eclampsia, disorders related to short gestation and low birth weight, and disorders related to long gestation and high birth weight. The diagnostic criteria for these APOs were based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10). All participants were of European descent, and the maximum sample overlap rate was 1.18%, with a type 1 error probability of less than 0.05[

12]. Detailed information for each dataset is presented in

Table 1.

Selection of Instrument Variants

The analysis of MR is based on three core assumptions: (1) The IV is strongly associated with the exposure; (2) The IV is not associated with any other potential confounders; and (3) The IV is not directly associated with the outcome, influencing it sorely through the exposure. Consequently, the IVs selected from single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) must satisfy the following criteria: (1) A statistically significant threshold of P < 5×10

−8 was utilized for genome-wide significance to fulfill assumption 1. If no IVs remained, the P-value threshold was relaxed to 5×10

−6. (2) SNPs exhibiting linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r² > 0.001) were excluded using the clumping algorithm within a 10,000 kb window. (3) We computed F-statistic values for each IV, with the relevant equations presented below.

SNPs with a Cragg-Donald F-statistic of less than 10 were excluded to mitigate weak instrumental variable bias[

13]. (4) Palindromic SNPs were excluded. (5) SNPs associated with confounding factors and APOs were also excluded based on the LDtrait database (LDlink: An Interactive Web Tool for Exploring Linkage Disequilibrium in Population Groups). The confounding factors related to the exposures and outcomes included BMI, fasting glucose and T2DM.

In univariable MR (UVMR), we employed several methods, including inverse variance weighted (IVW), MR-Egger, weighted median, simple mode, and weighted mode, to evaluate the causal relationship between exposure and outcomes. IVW was utilized as the primary method for the statistical assessment of IVs and was regarded as the most powerful statistical analysis available[

14]. MR-Egger was specifically used to identify causal relationships based on weak assumptions, particularly the Instrument Strength Independent of Direct Effect (InSIDE) assumption[

15]. The weighted median method requires that genetic variables contribute at least 50% of the total weight, thereby effectively integrating data from multiple genetic variables into a unified causal estimation. This approach ensures consistency in estimation, even when up to 50% of the information originates from invalid IVs, and demonstrates a superior finite-sample type-I error rate compared to IVW[

16]. The simple mode and weighted mode methods are limited to evaluating causal validity based solely on the cluster with the largest number of SNPs, without the ability to estimate the bandwidth parameter[

15]. A P-value threshold of 0.05 was established, with exposure considered a risk factor when the odds ratio (OR) exceeded 1 and a protective factor when the OR was less than 1. The heterogeneity of SNPs selected in UVMR was assessed using the Cochran Q-statistic, applied through both MR-Egger and IVW methods, with a P-value <0.05 deemed statistically significant for the heterogeneity test. In cases where heterogeneity was detected among the IVs, a multiplicative random effects model of IVW (IVW-MRE) was implemented, and we further validated the results using the weighted median method to mitigate bias. Effect sizes for each MR method were visualized using scatter plots, while forest plots estimated the effect sizes for each SNP, and funnel plots illustrated the distributions of individual SNP effects.

To further validate the consistency and robustness of the UVMR results, we conducted both multivariable MR (MVMR) and sensitivity analyses. MVMR is an extension of MR that utilizes genetic variants to assess the causal relationships between multiple related exposures and outcomes within the same model, thereby further mitigating potential confounding factors[

17]. We performed MVMR to evaluate the impact of AS intake from various sources on APOs, while adjusting for BMI and T2DM. Considering all T2DM pregnant patient meet the diagnostic criteria of gestational diabetes, we changed the confounding factors as BMI and fasting glucose for adjustment when the outcome was gestational diabetes. The SNPs employed in the MVMR were combinations of IVs for each exposure, with selection criteria consistent with those described previously except for (5). We applied IVW, MR-Egger, and weighted median methods.

For UVMR, sensitivity analyses included the 'leave-one-out' method, pleiotropy test, and horizontal pleiotropy test. The 'leave-one-out' method was employed to assess the impact of each individual SNP on the outcome by removing that SNP and calculating the combined effect of the remaining SNPs separately. Pleiotropy, defined as one locus influencing multiple phenotypes, can undermine the reliability of MR results. The MR-Egger intercept was utilized to estimate the pleiotropic effect of a genetic variable[

18]. Horizontal pleiotropy was evaluated using the Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier (MR-PRESSO) global test. The MR-PRESSO outlier test specifically identified outliers for each IV, and outlier IVs were excluded if horizontal pleiotropy was detected. Subsequently, the MR analysis was conducted again. This approach ensured that MR-PRESSO provided corrected causal results free from the confounding effects of pleiotropy and outliers. For MVMR, pleiotropy was assessed based on the MR-Egger intercept results.

All statistical analyses were performed using the TwoSampleMR (version 0.5.8), MVMR (version 0.4), and ggpubr packages (version 0.6.0) implemented in R (version 4.3.1).

3. Results

3.1. Selection of IVs

A rigorous screening process resulted in the selection of 41, 18, and 18 SNPs associated with the intake of AS added to cereal, coffee, and tea, respectively, as IVs. Detailed information regarding each IV is available in

Table S1.

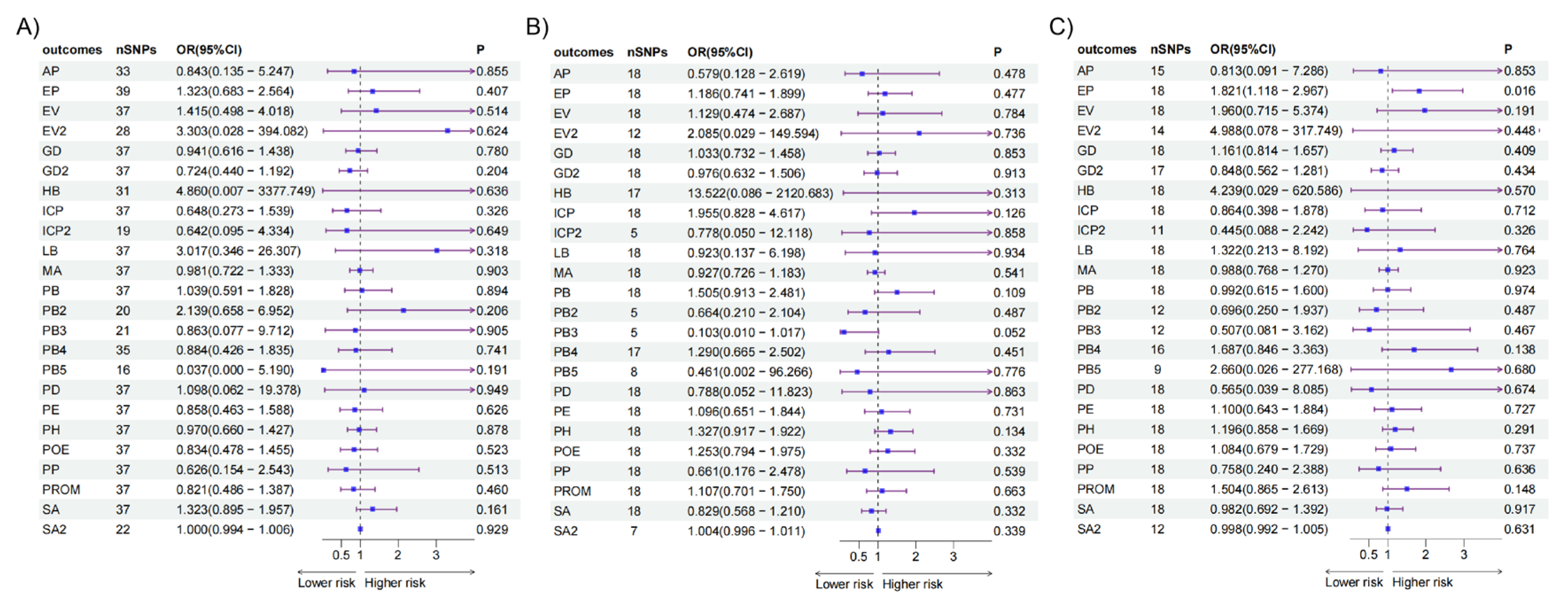

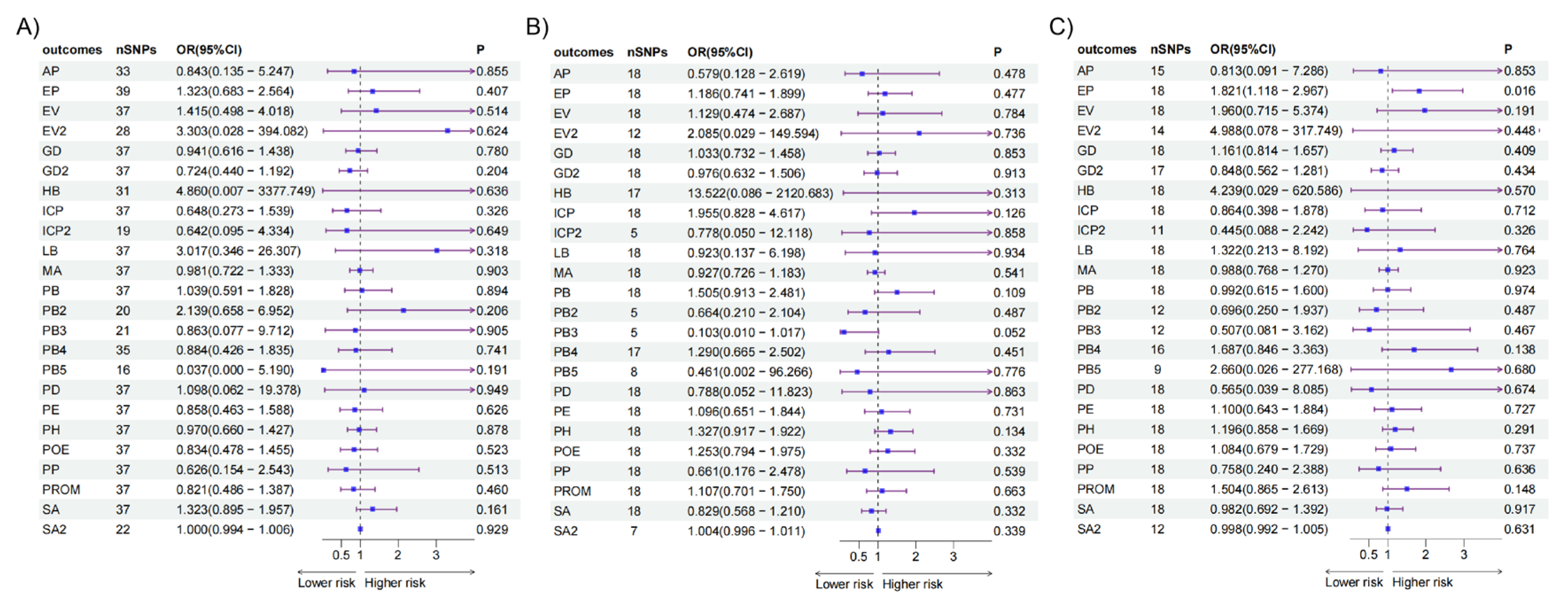

3.2. UVMR

A causal effect of the intake of AS added to tea on ectopic pregnancy was observed [OR=1.821(1.118 - 2.967), p=0.016]. No causal relationships were identified between the intake of AS from various sources and the other APOs (

Figure 2,

Figure S1-3). The IVW-MRE method was employed, and the weighted median results were verified when heterogeneity was detected, yielding consistent outcomes (

Table S2-3). The robustness of our findings was further confirmed by the forest plot, funnel plot, and results from the 'Leave-one-out' method (

Figure S4-12). Pleiotropy was observed when the exposure was the intake of AS added from tea and the outcomes were placenta previa and spontaneous abortion, as indicated by the MR Egger intercept or the MR-PRESSO global test (

Table S4). However, outlier analysis did not identify any outlier instrumental variables.

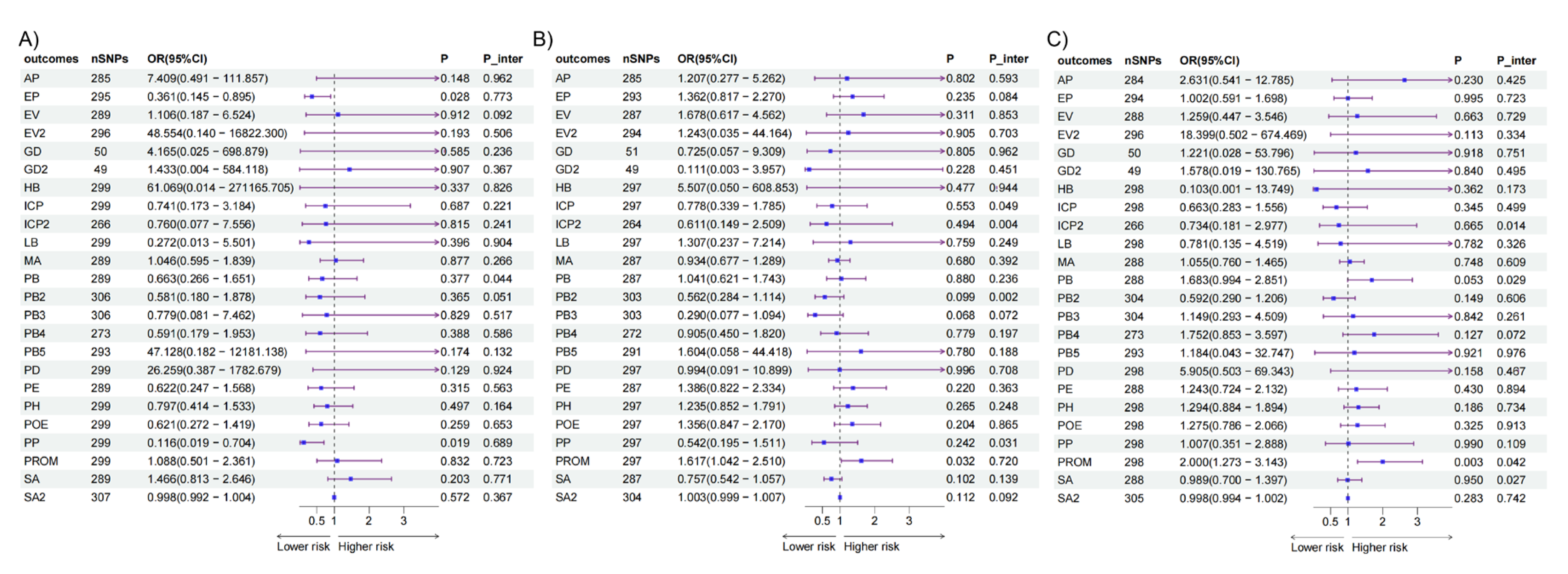

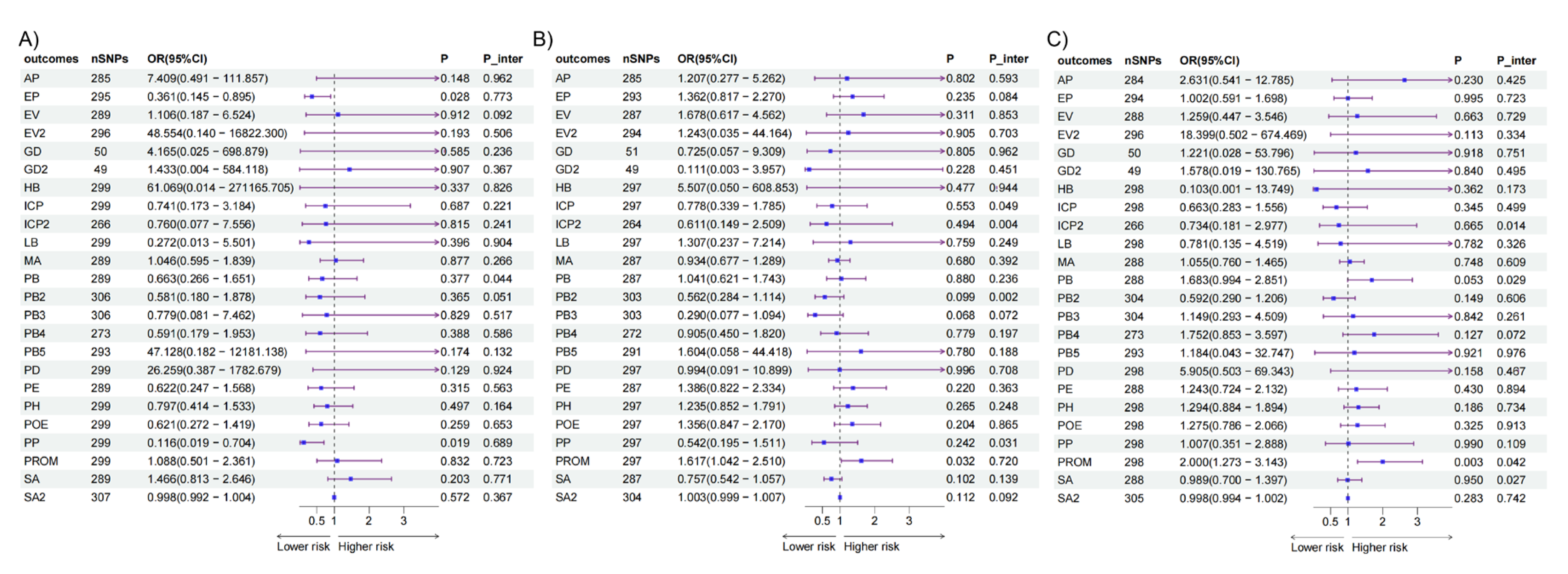

3.3. MVMR

After adjusting for BMI and T2DM, causal effects were detected in the intake of AS added to cereal on ectopic pregnancy [OR=0.361(0.145 - 0.895), p=0.028] and placenta previa [OR=0.116(0.019 - 0.704), p=0.019] (

Figure 3, Table 5-6). Additionally, significant effects were noted for the intake of AS added to coffee on PROM [OR=1.617 (1.042 - 2.510), p=0.032]. Results from the MR Egger intercept indicated pleiotropy in some analyses (

Figure 3).

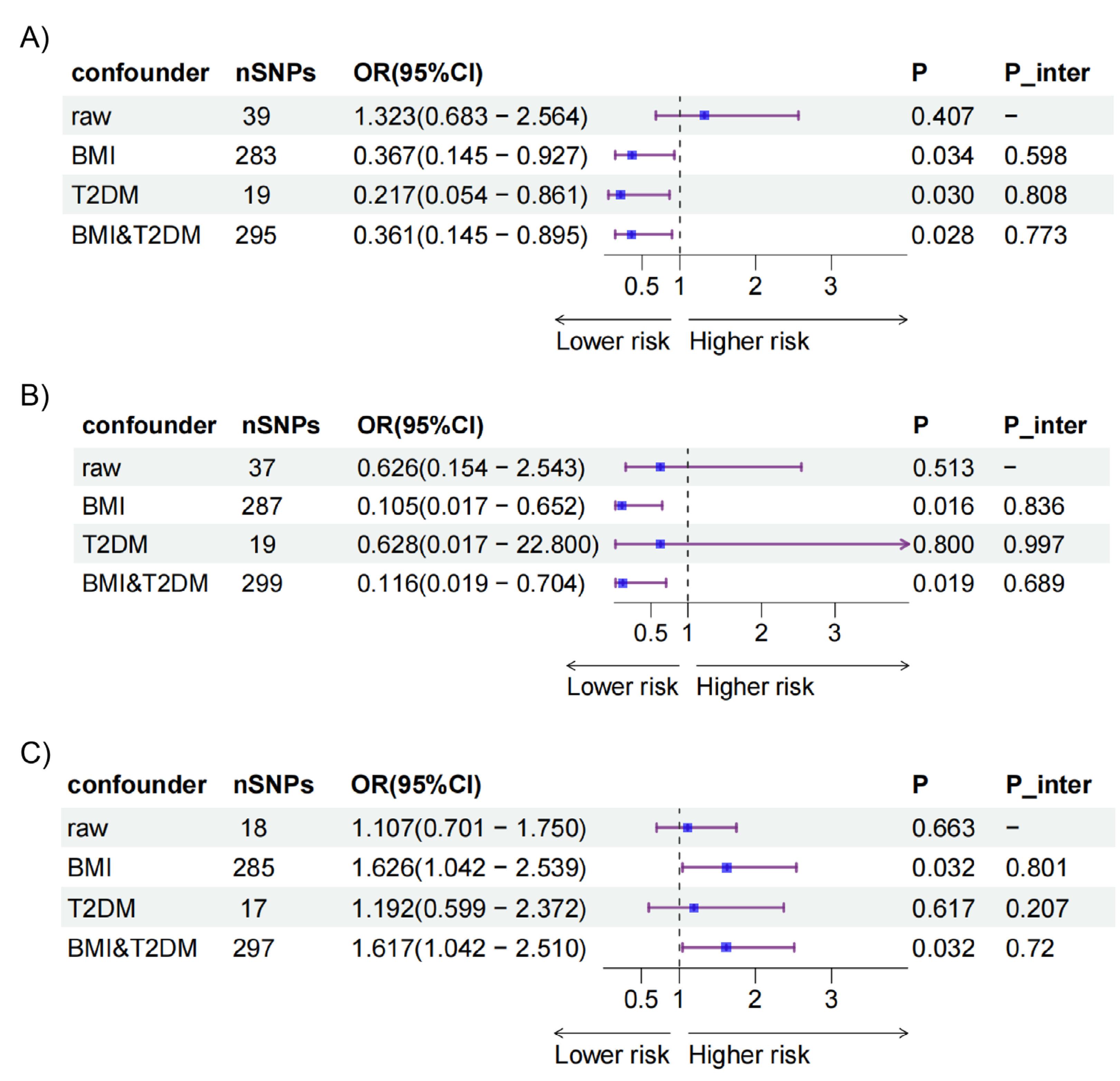

Then we further conducted MVMR by adjusting for BMI and T2DM respectively in the other exposures and outcomes where the causal effects were significant (

Figure 4,

Table S7). The adjustments for BMI yielded results consistent with the aforementioned findings. Causal effect of the intake of AS added to cereal on ectopic pregnancy remained consistent when adjusting for T2DM.

4. Discussion

Our study is the first to systematically analyze the causal relationship between the intake of AS from various sources and APOs at the genetic variation level. The results of UVMR suggest that the intake of AS added to tea may increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy. MVMR results indicate that the intake of AS added to cereal may also reduce the risk of ectopic pregnancy and placenta previa. Furthermore, the intake of AS added to coffee may elevate the risk of PROM.

In the Randomised Control Trial of Low Glycaemic Index Diet in Pregnancy to Prevent Recurrence of Macrosomia (ROLO), one-third of pregnant women reported consuming AS during each trimester[

19]. This proportion increased to 51.4% after receiving advice on a low glycemic index diet, suggesting that AS intake is quite prevalent during pregnancy. Studies from various regions have shown that the AS intake among pregnant women is consistent with, or even exceeds, that of the general population[

6,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Therefore, the potential impact of AS intake on APOs represents a significant research question.

Current research on the relationship between AS and APOs in pregnant women is limited and inconsistent. Studies conducted in animal models have demonstrated that aspartame consumption during pregnancy may lead to impaired glucose tolerance, weight gain, and cognitive impairments[

24,

25]. However, a meta-analysis encompassing 24 studies found that most did not identify any significant impact of AS.[

26]. In human studies, the consumption of diet drinks during pregnancy has been linked to increased risks of gestational weight gain, gestational diabetes, and preeclampsia[

3,

27,

28]. The relationship between AS and preterm birth remains controversial[

4,

29]. Most of these studies are observational, making it challenging to establish causality. Prospective cohort studies frequently rely on Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQ) instead of more rigorous 24-hour dietary recalls or dietary provisions, which can introduce recall bias. The limitations inherent in study design hinder the establishment of causality and the exclusion of confounding factors, resulting in inconsistent findings. To address these issues, we conducted a two-sample MR analysis utilizing GWAS data to minimize confounding and reverse causation. Recognizing that AS intake and APOs may be related to BMI and glucose metabolism, we also performed MVMR to elucidate their independent causal effects. Furthermore, our study included sensitivity analyses to enhance the stability and reliability of the results. Ultimately, our findings do not support the causal effects of AS intake on the aforementioned outcomes.

Ectopic pregnancy and placenta previa are associated with maternal morbidity. Currently, there are no epidemiological studies examining the relationship between AS intake and these outcomes. In UVMR analysis, the intake of AS added to tea was found to increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy; however, this association lacked consistency in MVMR results. When adjusting for BMI and T2DM, the intake of AS added to cereal significantly reduced the incidence of both ectopic pregnancy and placenta previa. The results remained stable when adjusting for BMI and the causal effects remained consistent in ectopic pregnancy when adjusting for T2DM. Nevertheless, no significant effects on these outcomes were observed in the UVMR analysis, potentially due to a preference for AS intake added to cereal among individuals with higher BMI or T2DM. Pregnant women with higher BMI or T2DM may utilize AS to decrease overall sugar intake during pregnancy, which could aid in controlling blood sugar levels and weight. This mechanism may contribute to a reduced risk of ectopic pregnancy and placenta previa.

PROM is one of the most common causes of preterm birth. Our study found that, after adjusting for BMI and T2DM, the intake of AS added to coffee is a risk factor for PROM. Currently, there are no epidemiological studies investigating the relationship between AS intake and PROM. Previous cross-sectional studies have indicated that coffee consumption during pregnancy is associated with PROM. Pregnant women who consumed three or more cups of coffee daily during the first trimester had more than double the risk of PROM compared to those who consumed fewer than three cups.[

30]. Therefore, the impact of AS added to coffee on PROM may be attributed to an increase in overall coffee consumption among pregnant women.

Our study has several limitations. (1) Our research exclusively included individuals of European ancestry, which may result in disease incidence and dietary preferences that are specific to this group. This limitation affects the generalizability of our conclusions to other populations. Nonetheless, we incorporated as much outcome data as possible to enhance the reliability of our findings and their applicability to various European populations. (2) Due to the constraints of GWAS summary-level data, we were unable to conduct subgroup analyses to investigate potential stratified effects of factors such as age, health status, glucose levels, and insulin resistance. (3) We focused solely on BMI, fasting glucose and T2DM as confounding factors; however, other potential confounders that may affect the relationship between AS intake and APOs warrant further exploration. Future studies should aim to expand the study population to validate the potential impact of AS intake on placenta previa and PROM. Additionally, further research is necessary to investigate the underlying mechanisms, which will provide guidance on AS intake for women of reproductive age.

5. Conclusions

Our study identified causal effects of AS intake on placenta previa and PROM. Further randomized clinical trials are needed to confirm this potential causality.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1. The scatter plots of univariable mendelian randomization when exposure is the intake of artificial sweetener added to cereal. Figure S2. The scatter plots of univariable mendelian randomization when exposure is intake of artificial sweetener added to coffee. Figure S3. The scatter plots of univariable mendelian randomization when exposure is intake of artificial sweetener added to tea. Figure S4. The forest plots for each single nucleotide polymorphism of univariable mendelian randomization when exposure is intake of artificial sweetener added to cereal. Figure S5. The forest plots for each single nucleotide polymorphism of univariable mendelian randomization when exposure is intake of artificial sweetener added to coffee. Figure S6. The forest plots for each single nucleotide polymorphism of univariable mendelian randomization when exposure is intake of artificial sweetener added to cereal. Figure S7. The funnel plots for of univariable mendelian randomization when exposure is intake of artificial sweetener added to cereal. Figure S8. The funnel plots for of univariable mendelian randomization when exposure is intake of artificial sweetener added to coffee. Figure S9. The funnel plots for of univariable mendelian randomization when exposure is intake of artificial sweetener added to tea. Figure S10. The results of ‘leave-one-out’ of univariable mendelian randomization when exposure is intake of artificial sweetener added to cereal. Figure S11. The results of ‘leave-one-out’ of univariable mendelian randomization when exposure is intake of artificial sweetener added to coffee. Figure S12. The results of ‘leave-one-out’ of univariable mendelian randomization when exposure is intake of artificial sweetener added to tea. Table S1. Information on instrumental variables selected in univariable mendelian randomization. Table S2. Results of univariable mendelian randomization in various methods. Table S3. Results of pleiority analysis in univariable mendelian randomization. Table S4. Results of sensitivity analysis in univariable mendelian randomization. Table S5. Information on instrumental variables selected in body mass index, fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Table S6. Results of multivariable mendelian randomization in various methods. Table S7. Results of multivariable mendelian randomization adjusting for body mass index or type 2 diabetes mellitus in various methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M. and K.H.; methodology, D.M and M. L.; formal analysis, D.M. and M.L.; data curation, D.M. and Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M. and M.L; writing—review and editing, K.H. and R.L.; visualization, D.M. and Z.Z.; supervision, K.H. and R.L.; funding acquisition, K.H. and R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Project funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, grant number 2022M720295.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted using published studies and datasets that provide publicly available summary statistics. All original studies received approval from the relevant ethical review boards, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Furthermore, since no individual-level data were utilized in this study, no additional ethical review board.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all the participants and investigators of the original studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Debras, C.; Deschasaux-Tanguy, M.; Chazelas, E.; Sellem, L.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; Szabo de Edelenyi, F.; Agaësse, C.; De Sa, A.; Lutchia, R. , et al. Artificial Sweeteners and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in the Prospective NutriNet-Santé Cohort. Diabetes care 2023, 46, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Li, L. Associations between artificial sweetener intake from cereals, coffee, and tea and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A genetic correlation, mediation, and mendelian randomization analysis. PloS one 2024, 19, e0287496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hu, F.B.; Yeung, E.; Willett, W.; Zhang, C. Prospective study of pre-gravid sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes care 2009, 32, 2236–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Englund-Ögge, L.; Brantsæter, A.L.; Haugen, M.; Sengpiel, V.; Khatibi, A.; Myhre, R.; Myking, S.; Meltzer, H.M.; Kacerovsky, M.; Nilsen, R.M. , et al. Association between intake of artificially sweetened and sugar-sweetened beverages and preterm delivery: a large prospective cohort study. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2012, 96, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halldorsson, T.I.; Strøm, M.; Petersen, S.B.; Olsen, S.F. Intake of artificially sweetened soft drinks and risk of preterm delivery: a prospective cohort study in 59,334 Danish pregnant women. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2010, 92, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, M.B.; Sharma, A.K.; de Souza, R.J.; Dolinsky, V.W.; Becker, A.B.; Mandhane, P.J.; Turvey, S.E.; Subbarao, P.; Lefebvre, D.L.; Sears, M.R. Association Between Artificially Sweetened Beverage Consumption During Pregnancy and Infant Body Mass Index. JAMA pediatrics 2016, 170, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, M.S.; Andrews, S.J.; Elsworth, B.; Gaunt, T.R.; Hemani, G.; Marcora, E. The variant call format provides efficient and robust storage of GWAS summary statistics. Genome biology 2021, 22, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.A.; Lagou, V.; Welch, R.P.; Wheeler, E.; Montasser, M.E.; Luan, J.; Mägi, R.; Strawbridge, R.J.; Rehnberg, E.; Gustafsson, S. , et al. Large-scale association analyses identify new loci influencing glycemic traits and provide insight into the underlying biological pathways. Nature genetics 2012, 44, 991–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Orazio, P.; Burnett, R.W.; Fogh-Andersen, N.; Jacobs, E.; Kuwa, K.; Külpmann, W.R.; Larsson, L.; Lewenstam, A.; Maas, A.H.; Mager, G. , et al. Approved IFCC recommendation on reporting results for blood glucose (abbreviated). Clinical chemistry 2005, 51, 1573–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurki, M.I.; Karjalainen, J.; Palta, P.; Sipilä, T.P.; Kristiansson, K.; Donner, K.M.; Reeve, M.P.; Laivuori, H.; Aavikko, M.; Kaunisto, M.A. , et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature 2023, 613, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollis, E.; Mosaku, A.; Abid, A.; Buniello, A.; Cerezo, M.; Gil, L.; Groza, T.; Güneş, O.; Hall, P.; Hayhurst, J. , et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog: knowledgebase and deposition resource. Nucleic acids research 2023, 51, D977–d985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, S.; Davies, N.M.; Thompson, S.G. Bias due to participant overlap in two-sample Mendelian randomization. Genetic epidemiology 2016, 40, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S.; Thompson, S.G. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. International journal of epidemiology 2011, 40, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S.; Butterworth, A.; Thompson, S.G. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genetic epidemiology 2013, 37, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slob, E.A.W.; Burgess, S. A comparison of robust Mendelian randomization methods using summary data. Genetic epidemiology 2020, 44, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J.; Davey Smith, G.; Haycock, P.C.; Burgess, S. Consistent Estimation in Mendelian Randomization with Some Invalid Instruments Using a Weighted Median Estimator. Genetic epidemiology 2016, 40, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, E. Multivariable Mendelian Randomization and Mediation. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J.; Davey Smith, G.; Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. International journal of epidemiology 2015, 44, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, M.C.; Cawley, S.; Geraghty, A.A.; Walsh, N.M.; O'Brien, E.C.; McAuliffe, F.M. The consumption of low-calorie sweetener containing foods during pregnancy: results from the ROLO study. European journal of clinical nutrition 2022, 76, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentealba Arévalo, F.; Espinoza Espinoza, J.; Salazar Ibacahe, C.; Durán Agüero, S. Consumption of non-caloric sweeteners among pregnant Chileans: a cross-sectional study. Nutricion hospitalaria 2019, 36, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Olsen, S.F.; Mendola, P.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Rawal, S.; Hinkle, S.N.; Yeung, E.H.; Chavarro, J.E.; Grunnet, L.G.; Granström, C. , et al. Maternal consumption of artificially sweetened beverages during pregnancy, and offspring growth through 7 years of age: a prospective cohort study. International journal of epidemiology 2017, 46, 1499–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sylvetsky, A.C.; Figueroa, J.; Rother, K.I.; Goran, M.I.; Welsh, J.A. Trends in Low-Calorie Sweetener Consumption Among Pregnant Women in the United States. Current developments in nutrition 2019, 3, nzz004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillman, M.W.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Fernandez-Barres, S.; Kleinman, K.; Taveras, E.M.; Oken, E. Beverage Intake During Pregnancy and Childhood Adiposity. Pediatrics 2017, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, J.W.; Jacobsen, D.J.; Donnelly, J.E. Beverage consumption patterns in elementary school aged children across a two-year period. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2005, 24, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suez, J.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Thaiss, C.A.; Maza, O.; Israeli, D.; Zmora, N.; Gilad, S.; Weinberger, A. , et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature 2014, 514, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morahan, H.L.; Leenaars, C.H.C.; Boakes, R.A.; Rooney, K.B. Metabolic and behavioural effects of prenatal exposure to non-nutritive sweeteners: A systematic review and meta-analysis of rodent models. Physiology & behavior 2020, 213, 112696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault, K.M.; Carlsen, E.M.; Nørgaard, K.; Nilas, L.; Pryds, O.; Secher, N.J.; Olsen, S.F.; Halldorsson, T.I. Intake of Sweets, Snacks and Soft Drinks Predicts Weight Gain in Obese Pregnant Women: Detailed Analysis of the Results of a Randomised Controlled Trial. PloS one 2015, 10, e0133041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Lee, K.W.; Song, W.O. Dietary Patterns during Pregnancy Are Associated with Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9369–9382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petherick, E.S.; Goran, M.I.; Wright, J. Relationship between artificially sweetened and sugar-sweetened cola beverage consumption during pregnancy and preterm delivery in a multi-ethnic cohort: analysis of the Born in Bradford cohort study. European journal of clinical nutrition 2014, 68, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.A.; Mittendorf, R.; Stubblefield, P.G.; Lieberman, E.; Schoenbaum, S.C.; Monson, R.R. Cigarettes, coffee, and preterm premature rupture of the membranes. American journal of epidemiology 1992, 135, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The overall flowchart of the two-sample mendelian randomization study. BMI, body mass index; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 1.

The overall flowchart of the two-sample mendelian randomization study. BMI, body mass index; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 2.

Casual relationships between the intake of AS and APOs in UVMR. (A) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to cereal and APOs. (B) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to coffee and APOs. (C) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to tea and APOs. AS, artificial sweetener; APOs, adverse pregnancy outcomes; UVMR, univariable mendelian randomization; IVW, inverse variance weighted; AP, abruption placenta (O15_PLAC_PREMAT_SEPAR); EP, ectopic pregnancy (GCST90272883); EV, excessive vomiting in pregnancy (O15_EXCESS_VOMIT_PREG); EV2, excessive vomiting in pregnancy (GCST90044480); GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus (GEST_DIABETES); GDM2, gestational diabetes mellitus (GCST90296696); HB, disorders associated with long gestation and high birth weight (R10_P16_DISORD_RELATED_LONG_GESTATION_HIGH_BIRTHWGHTT);ICP2, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (O15_ICP_WIDE); ICP2, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (GCST90095084); LB, disorders related to short gestation and low birth weight (R10_P16_DISORD_RELATED_GESTATION_LOW_BIRTHWGHTT_NECIFIED); MD, medical abortion (O15_ABORT_MEDICAL); PB, preterm birth (O15_PRETERM); PB2, preterm birth (GCST008754); PB3, preterm birth (GCST008753); PB4, preterm birth (GCST90271753); PB5, preterm birth (GCST90271755); PD, placental disorders (O15_PLAC_DISORD); PE, preeclampsia (O15_PREECLAMPS);PH, pregnancy hypertension (O15_HYPTENSPREG); POE, pre-eclampsia or eclampsia (O15_PRE_OR_ECLAMPSIA); PP, placenta previa (O15_PLAC_PRAEVIA); PROM, premature rupture of membranes (O15_MEMBR_PREMAT_RUPT); SA, spontaneous abortion (O15_ABORT_SPONTAN); SA2, spontaneous abortion (ukb-d-O03).

Figure 2.

Casual relationships between the intake of AS and APOs in UVMR. (A) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to cereal and APOs. (B) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to coffee and APOs. (C) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to tea and APOs. AS, artificial sweetener; APOs, adverse pregnancy outcomes; UVMR, univariable mendelian randomization; IVW, inverse variance weighted; AP, abruption placenta (O15_PLAC_PREMAT_SEPAR); EP, ectopic pregnancy (GCST90272883); EV, excessive vomiting in pregnancy (O15_EXCESS_VOMIT_PREG); EV2, excessive vomiting in pregnancy (GCST90044480); GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus (GEST_DIABETES); GDM2, gestational diabetes mellitus (GCST90296696); HB, disorders associated with long gestation and high birth weight (R10_P16_DISORD_RELATED_LONG_GESTATION_HIGH_BIRTHWGHTT);ICP2, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (O15_ICP_WIDE); ICP2, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (GCST90095084); LB, disorders related to short gestation and low birth weight (R10_P16_DISORD_RELATED_GESTATION_LOW_BIRTHWGHTT_NECIFIED); MD, medical abortion (O15_ABORT_MEDICAL); PB, preterm birth (O15_PRETERM); PB2, preterm birth (GCST008754); PB3, preterm birth (GCST008753); PB4, preterm birth (GCST90271753); PB5, preterm birth (GCST90271755); PD, placental disorders (O15_PLAC_DISORD); PE, preeclampsia (O15_PREECLAMPS);PH, pregnancy hypertension (O15_HYPTENSPREG); POE, pre-eclampsia or eclampsia (O15_PRE_OR_ECLAMPSIA); PP, placenta previa (O15_PLAC_PRAEVIA); PROM, premature rupture of membranes (O15_MEMBR_PREMAT_RUPT); SA, spontaneous abortion (O15_ABORT_SPONTAN); SA2, spontaneous abortion (ukb-d-O03).

Figure 3.

Causal relationships between the intake of AS adjusting for confounders and APOs in MVMR. (A) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to cereal and APOs. (B) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to coffee and APOs. (C) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to tea and APOs. AS, artificial sweetener; APOs, adverse pregnancy outcomes; MVMR, multivariable mendelian randomization; IVW, inverse variance weighted; AP, abruption placenta (O15_PLAC_PREMAT_SEPAR); EP, ectopic pregnancy (GCST90272883); EV, excessive vomiting in pregnancy (O15_EXCESS_VOMIT_PREG); EV2, excessive vomiting in pregnancy (GCST90044480); GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus (GEST_DIABETES); GDM2, gestational diabetes mellitus (GCST90296696); HB, disorders associated with long gestation and high birth weight (R10_P16_DISORD_RELATED_LONG_GESTATION_HIGH_BIRTHWGHTT);ICP2, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (O15_ICP_WIDE); ICP2, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (GCST90095084); LB, disorders related to short gestation and low birth weight (R10_P16_DISORD_RELATED_GESTATION_LOW_BIRTHWGHTT_NECIFIED); MD, medical abortion (O15_ABORT_MEDICAL); PB, preterm birth (O15_PRETERM); PB2, preterm birth (GCST008754); PB3, preterm birth (GCST008753); PB4, preterm birth (GCST90271753); PB5, preterm birth (GCST90271755); PD, placental disorders (O15_PLAC_DISORD); PE, preeclampsia (O15_PREECLAMPS);PH, pregnancy hypertension (O15_HYPTENSPREG); POE, pre-eclampsia or eclampsia (O15_PRE_OR_ECLAMPSIA); PP, placenta previa (O15_PLAC_PRAEVIA); PROM, premature rupture of membranes (O15_MEMBR_PREMAT_RUPT); SA, spontaneous abortion (O15_ABORT_SPONTAN); SA2, spontaneous abortion (ukb-d-O03).

Figure 3.

Causal relationships between the intake of AS adjusting for confounders and APOs in MVMR. (A) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to cereal and APOs. (B) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to coffee and APOs. (C) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to tea and APOs. AS, artificial sweetener; APOs, adverse pregnancy outcomes; MVMR, multivariable mendelian randomization; IVW, inverse variance weighted; AP, abruption placenta (O15_PLAC_PREMAT_SEPAR); EP, ectopic pregnancy (GCST90272883); EV, excessive vomiting in pregnancy (O15_EXCESS_VOMIT_PREG); EV2, excessive vomiting in pregnancy (GCST90044480); GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus (GEST_DIABETES); GDM2, gestational diabetes mellitus (GCST90296696); HB, disorders associated with long gestation and high birth weight (R10_P16_DISORD_RELATED_LONG_GESTATION_HIGH_BIRTHWGHTT);ICP2, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (O15_ICP_WIDE); ICP2, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (GCST90095084); LB, disorders related to short gestation and low birth weight (R10_P16_DISORD_RELATED_GESTATION_LOW_BIRTHWGHTT_NECIFIED); MD, medical abortion (O15_ABORT_MEDICAL); PB, preterm birth (O15_PRETERM); PB2, preterm birth (GCST008754); PB3, preterm birth (GCST008753); PB4, preterm birth (GCST90271753); PB5, preterm birth (GCST90271755); PD, placental disorders (O15_PLAC_DISORD); PE, preeclampsia (O15_PREECLAMPS);PH, pregnancy hypertension (O15_HYPTENSPREG); POE, pre-eclampsia or eclampsia (O15_PRE_OR_ECLAMPSIA); PP, placenta previa (O15_PLAC_PRAEVIA); PROM, premature rupture of membranes (O15_MEMBR_PREMAT_RUPT); SA, spontaneous abortion (O15_ABORT_SPONTAN); SA2, spontaneous abortion (ukb-d-O03).

Figure 4.

Causal relationships between the intake of AS and APOs in UVMR and MVMR. (A) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to cereal and ectopic pregnancy adjusting for different confounders. (B) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to cereal and placenta previa adjusting for different confounders. (C) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to coffee and PROM adjusting for different confounders. AS, artificial sweetener; APOs, adverse pregnancy outcomes; UVMR, univariable mendelian randomization; MVMR, multivariable mendelian randomization; IVW, inverse variance weighted; PROM, premature rupture of membranes.

Figure 4.

Causal relationships between the intake of AS and APOs in UVMR and MVMR. (A) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to cereal and ectopic pregnancy adjusting for different confounders. (B) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to cereal and placenta previa adjusting for different confounders. (C) Results of IVW between the intake of AS added to coffee and PROM adjusting for different confounders. AS, artificial sweetener; APOs, adverse pregnancy outcomes; UVMR, univariable mendelian randomization; MVMR, multivariable mendelian randomization; IVW, inverse variance weighted; PROM, premature rupture of membranes.

Table 1.

The list of genome wide association study included in the mendelian randomization study.

Table 1.

The list of genome wide association study included in the mendelian randomization study.

| Traits |

Consortium |

Author and year |

Sample size(cases/controls) |

Population |

GWAS ID |

| Exposure |

|

|

|

|

|

| Intake of artificial sweetener added to cereal |

MRC-IEU |

Ben E et al. (2018) |

64,949 |

European |

ukb-b-3143 |

| Intake of artificial sweetener added to coffee |

MRC-IEU |

Ben E et al. (2018) |

64,949 |

ukb-b-1338 |

| Intake of artificial sweetener added to tea |

MRC-IEU |

Ben E et al. (2018) |

64,949 |

ukb-b-5867 |

| Body mass index |

Neale Lab |

Neale B et al.(2017) |

336,107 |

ukb-a-248 |

| Type 2 diabetes |

MRC-IEU |

Ben E et al. (2018) |

462,933 |

ukb-b-13806 |

| Fasting glucose |

MAGIC |

Scott A et al. (2012) |

133,010 |

ieu-b-114 |

| Outcome |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ectopic pregnancy |

GWAS Catalog |

Pujol G et al. (2023) |

7,070/248,810 |

European |

GCST90272883 |

| Excessive vomiting in pregnancy |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

2,092/163,702 |

O15_EXCESS_VOMIT_PREG |

| GWAS Catalog |

Jiang L et al. (2021) |

146/247,394 |

GCST90044480 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

11,279/179,600 |

GEST_DIABETES |

| GWAS Catalog |

Elliott A et al. (2024) |

12,332/131,109 |

GCST90296696 |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

2,196/188,683 |

O15_ICP_WIDE |

| GWAS Catalog |

Dixon P et al. (2022) |

1,138/153,642 |

GCST90095084 |

| Medical abortion |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

32,550/135,962 |

O15_ABORT_MEDICAL |

| Preeclampsia |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

5,922/176,113 |

O15_PREECLAMPS |

| Pregnancy hypertension |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

13,071/177,808 |

O15_HYPTENSPREG |

| Premature rupture of membranes |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

6,129/154,102 |

O15_MEMBR_PREMAT_RUPT |

| Preterm birth |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

7,678/148,153 |

O15_PRETERM |

| GWAS Catalog |

Liu X et al.(2019) |

4,775/60,148 |

GCST008754 |

| GWAS Catalog |

Liu X et al.(2019) |

1,139/60,148 |

GCST008753 |

| GWAS Catalog |

Pasanen A et al.(2023) |

4,925/49,105 |

GCST90271753 |

| GWAS Catalog |

Pasanen A et al.(2023) |

286/488 |

GCST90271755 |

| Spontaneous abortion |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

15,073/135,962 |

O15_ABORT_SPONTAN |

| Neale Lab |

Neale B et al.(2017) |

1,150/360,044 |

ukb-d-O03 |

| Placental disorders |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

253/182,824 |

O15_PLAC_DISORD |

| Placenta previa |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

1,400/182,824 |

O15_PLAC_PRAEVIA |

| Abruptio placenta |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

691/182,824 |

O15_PLAC_PREMAT_SEPAR |

| Pre-eclampsia or eclampsia |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

7,965/211,852 |

O15_PRE_OR_ECLAMPSIA |

| Disorders related to short gestation and low birth weight |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

573/411,504 |

R10_P16_DISORD_RELATED_GESTATION_LOW_BIRTHWGHTT_NECIFIED |

| Disorders related to long gestation and high birth weight |

FinnGen |

NA. (2021) |

65/411,504 |

R10_P16_DISORD_RELATED_LONG_GESTATION_HIGH_BIRTHWGHTT |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).