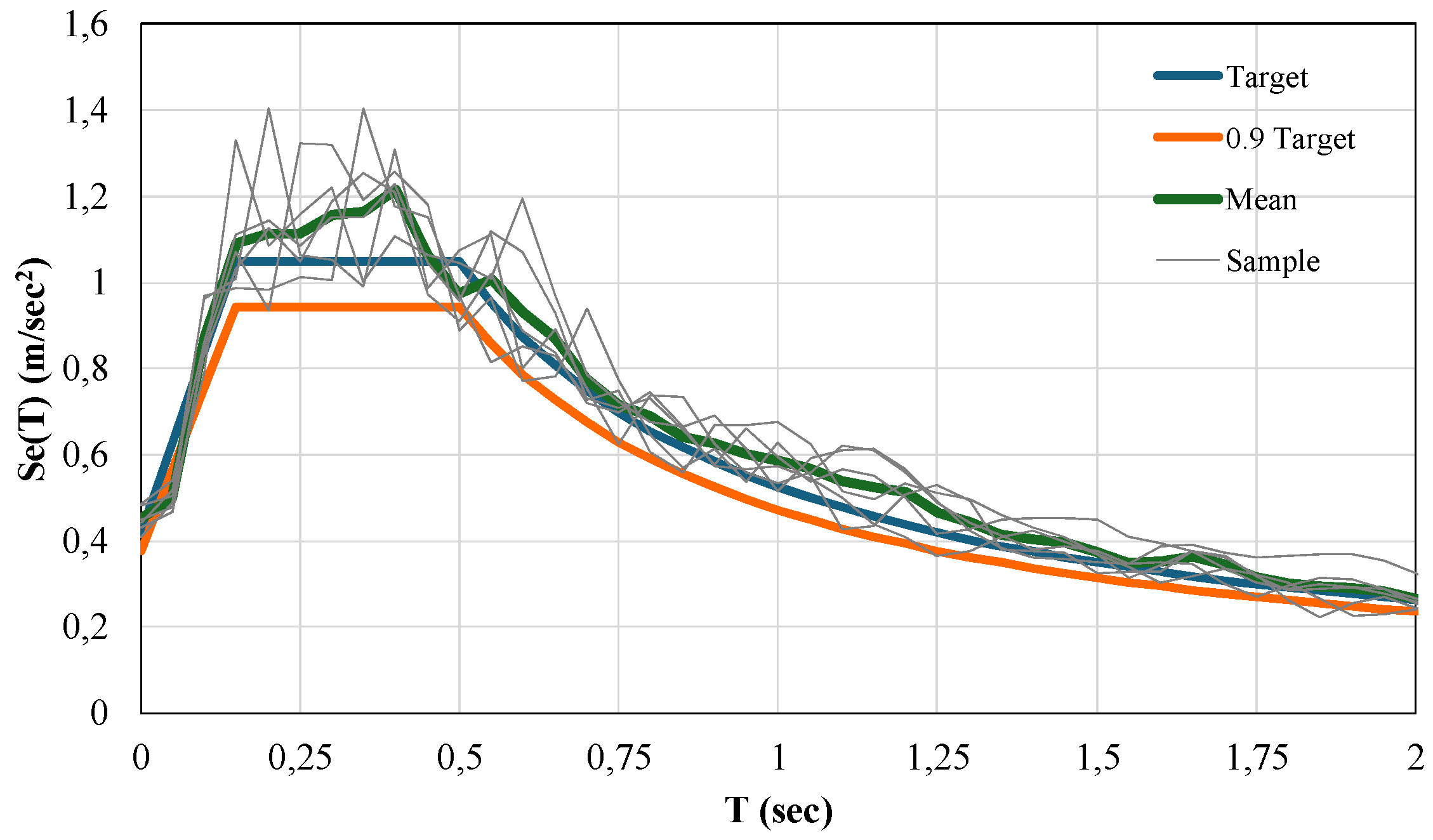

Most of the design method for retrofitting frames by inserting dissipative bracings integrates the pushover analysis of the multi-degree-of-freedom (MDOF) model of the bare frame (F) with the response spectrum analysis of equivalent single-degree-of-freedom (SDOF) systems, initially to estimate the global nonlinear displacement response of the frame to be strengthened. Then the strengthening dissipative braces are designed by setting a required performance goal, usually identified with a maximum total or interstory displacement. Then the global parameters of the SDOF braced frame are converted into thoseof the corresponding MDOF, and the stiffness and the strength of the bracing are distributed in plan and in elevation according to different criteria. Among the main issues that characterize the design phase, here attention is focused on two that distinguish the procedures in the literature: - the method for evaluation of the characteristics and the displacement demand of the SDOF equivalent system; - the criteria and the methods used to distribute stiffness and strength of the bracing in elevation. In the following, the two aforementioned methods in literature that exemplify the main strategies applied are compared with a very simple and straightforward method, in which some details that assume a paramount relevance in determining the response of the system are clarified and discussed.

2.1. Di Cesare and Ponzo Method (DCP) [17]

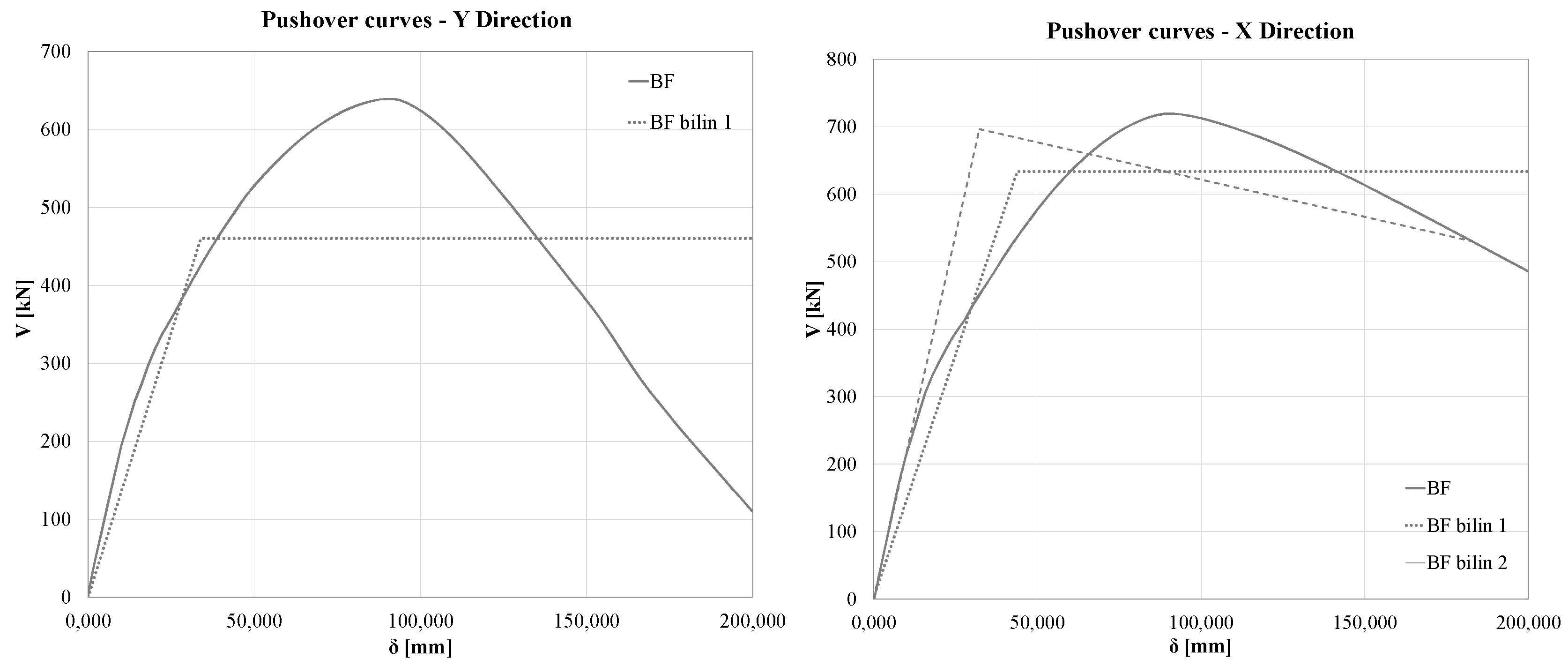

This method, according the prescription of EC8 [

38,

39], is characterized by the modeling of the equivalent SDOF by an elastic-perfectly plastic system (post-yielding stiffness

kH=0), with elastic stiffness

k corresponding to the secant stiffness at60% of the maximum base shear of the actual MDOF, and strength evaluated by imposing that the area under the actual pushover curve is equal to the area under the equivalent elastic-perfectly plastic curve, as prescribed in [

40]. Aiming at determining the displacement demand of the nonlinear system, initially an elastic equivalent SDOF is defined, which represents the dynamic characteristics of the first vibrating mode of the actual multi degree of freedom system; then the Equal Displacement Rule (

Figure 1b), i.e., displacement demand of nonlinear SDOF

d*max equals to the displacement demand of elastic SDOF

d*el is used having for SDOF having period of vibration

T* >Tc (

Tb and

Tc being the starting and the ending abscissa of the flat branch of the pseudo-acceleration response spectrum that characterized the input), while the conservative equal energy rule [

50,

51] is assumed for

T* <Tc; according to the latter assumption, the displacement demand is amplified by a coefficient

α,

.

=

del*α , being

α=(q*2+1

)/(2

q*) derived by the equal energy criteria between the static representation of the response of elastic and elastic-perfectly plastic system (

α=1 for

T* >Tc). Regarding the distribution of the stiffness and strength of the dissipative bracing along the height of the structure, the initial tentative distribution is proportional to the elastic stiffness of the bare frame. Correction are imposed if the ratio of total stiffness of two consecutive floor

Ki,DBF/

Ki+1,DBF exceeds 0.3 or is less than -0.1, and the ratio

Δρi=ρi/ρi-1 is not in the range 0.8≤

Δρi ≤1.2,

ρi= Vi,DBF/Vi,design being the ratio between the i-th story total strength of the dissipative braced frame and the design story shear

Thus, the procedure ensures that the stiffness and strength are distributed along the height of the braced building according to seismic code regularity criteria [

40], consistent with the criteria in [

38]. This aims at resulting in a uniform distribution of displacements and controls the maximum interstory drifts to stay within target limits.

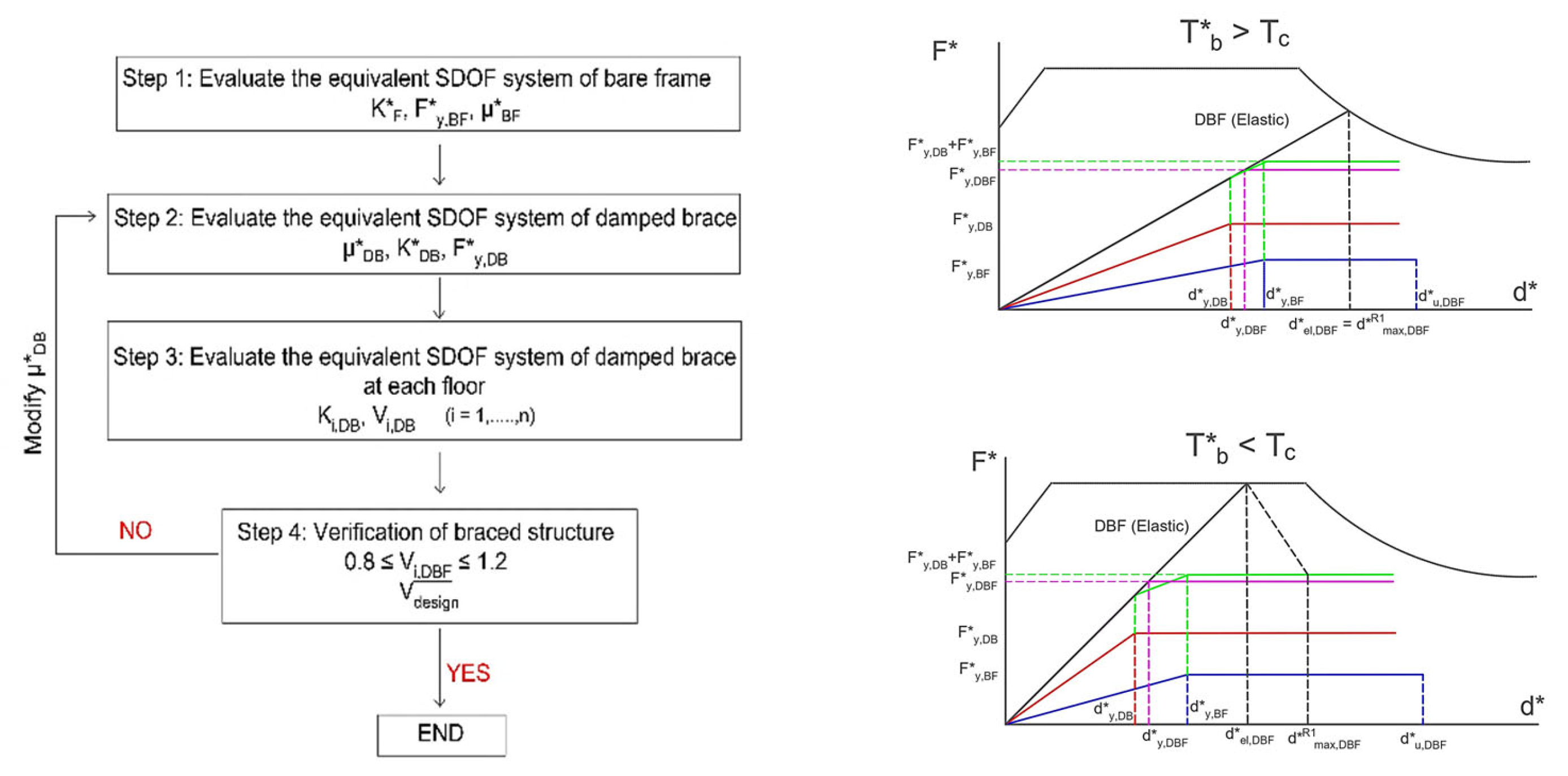

Thus, according to the flow chart in

Figure 1a, the first step in this procedure is to determine the mechanical characteristics of the equivalent SDOF system for the bare structure. Capacity curves for both main directions of the building are obtained using pushover analysis. The structure's idealized elastoplastic force-displacement relationship is defined using the following parameters

SDOF equivalent mass

m*

being

mi= the story mass, and

the eigenvector of the first mode in the relevant direction, normalized with respect to top story component, the

Γ1,BF ). Thus, equivalent SDOF force

F* and displacement

d* parameters are obtained from the attendant values of the actual MDOF parameters by division

first mode transformation factor

Γ1,BF. yield force (

Fy*

= Vby /Γ1),

yield displacement (

dy,BF* =

dy,BF /

Γ1) and ultimate displacement

du,BF* =

du,BF /

Γ1, as detailed in Annex-B of [

37], while the elastic stiffness (

kBF* = Fy,BF* / dy,BF*) or maximum ductility (

μBF* = du,BF* / dy,BF*) are the same of equivalent SDOF and actual MDOF.

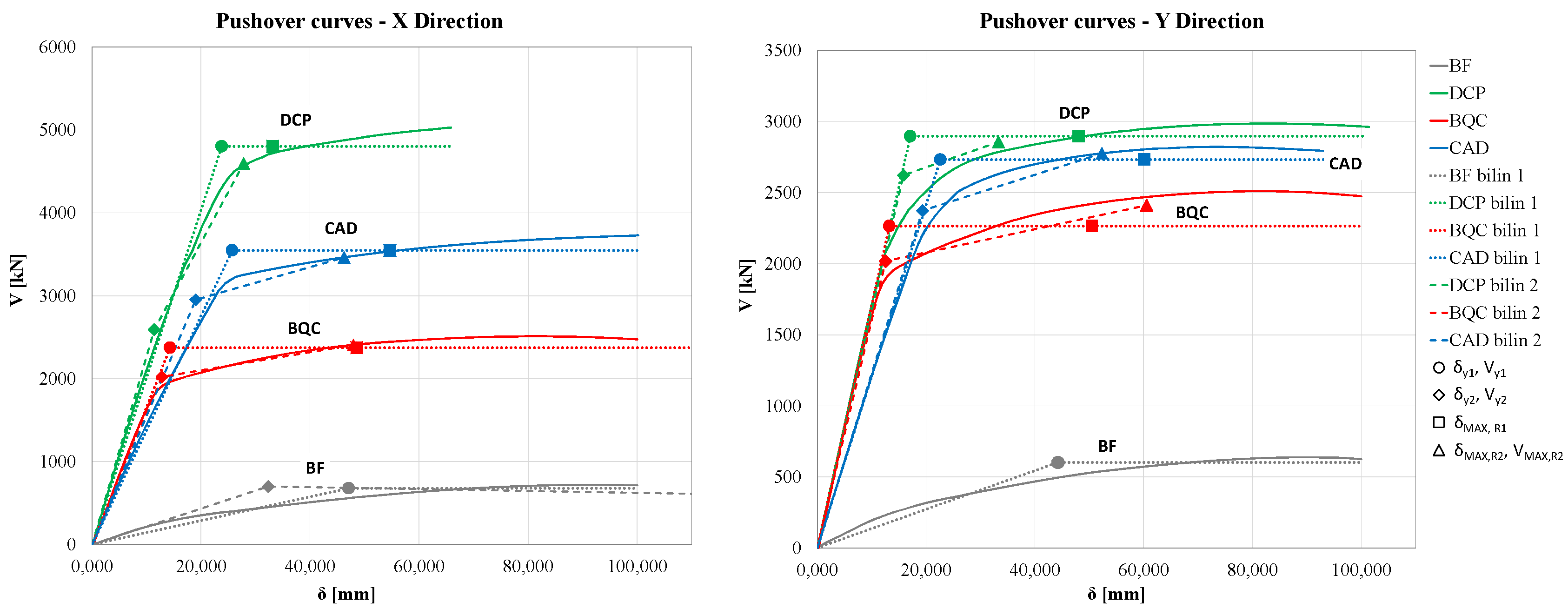

Step 2 involves evaluating the properties of the equivalent SDOF system of the dissipative braced frame. An iterative procedure should be performed separately for each main direction. The damped bracing (DB) system is idealized as an elastoplastic system defined by the yield force (FDB), elastic stiffness (kDB), and design ductility (μDB).

Given a maximum displacement dmax,DBF* for the equivalent SDOF system

of the braced frame DBF under the Basic Design Earthquake (BDE), the target ductility

μ*T,BF of the existing bare frame (BF) is defined by:

If the design goal is for the structure to remain elastic (μT,BF∗ = 1), then dmax,DBF* must be less than or equal to dy,BF*. Otherwise, if a limited inelastic capacity is allowed, target ductility (μ*) can range from 1.5 to 3, depending on whether the mechanism is brittle or ductile, respectively. In this case, dy,BF* <dmax,DBF* ≤ du,BF*.

Assuming a design ductility

μDB for the equivalent SDOF bracing system (DB), optimal ductility values range from 4 to 12, depending on the properties of the hysteretic device and the Serviceability Design Earthquake (SDE). Consequently, the yield displacement of the equivalent SDOF bracing system

dy,DB* is calculated by:

At the j

th step of an iterative procedure, the equivalent period

TDBF*j , the total elastic stiffness

kDBF*j of the DBF structure, are determined by means of the idealized elastoplastic behavior of the braced structure using Eqs (3a) and (3b).

where

α=1 is initially retained. The stiffness of the equivalent SDOF dissipative bracing system is obtained as the difference between the total stiffness and the frame stiffness

, and the yield force of the dissipative bracing as

.

If in Equation (3a), TDBF*j<Tc is found, a new idealized bilinear curve have to be evaluated on the basis of the force displacement curve obtained by the sum of the contribute of the actual bare frame and the properties of the dissipative bracing at the jth iteration, thus evaluating and the attendant value of the behavior factor

at the jth iteration evaluated as

and the iterative procedure starting from equation (3a) with the updated value of α should be performed.

Once the characteristic parameters of the equivalent dissipative bracing are evaluated, the actual dimensions and yielding force of the dissipative bracing can be evaluated as previously described. It has to be remarked that the authors suggest applying an amplification factor γx=1.2 on the yielding force of each dissipative bracing to avoid either buckling or premature yielding under the MCE (maximum considered earthquake).

The proposed procedure suffers from a) the conservative estimate of the displacements for systems with

T*<Tc based on the equal energy criterion already reported by the authors; b) the assumption of a further 20% increase in the resistance of the device

(γx=1.2 not taken into account in this work); b) the initial assumption of a distribution of the stiffness and resistance characteristics of the dissipative braces proportional to that of the frame, providing for a correction only if the elevation regularity requirements of the Italian code [

40] are not satisfied. Such correction, desired to correct the elevation irregularities of structures not designed for seismic actions, should be provided for already in the design phase of the bracing system; c) an approximate evaluation of the resistance of the frame at each floor obtained on the basis of the secant stiffness obtained in correspondence with an unspecified level of the external seismic action

2.2. Bruschi, Quaglini, and Calvi Method (BQC) [19]

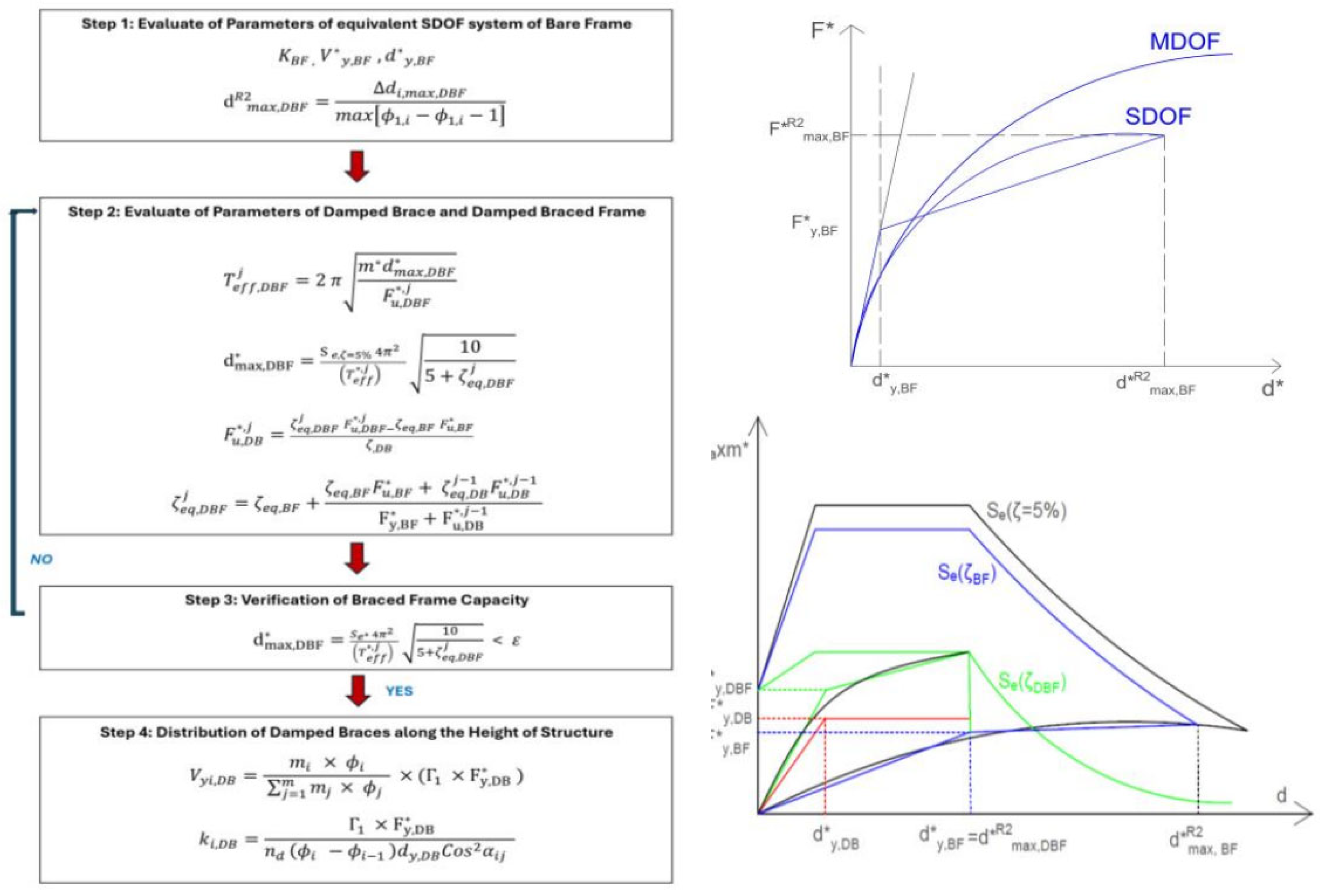

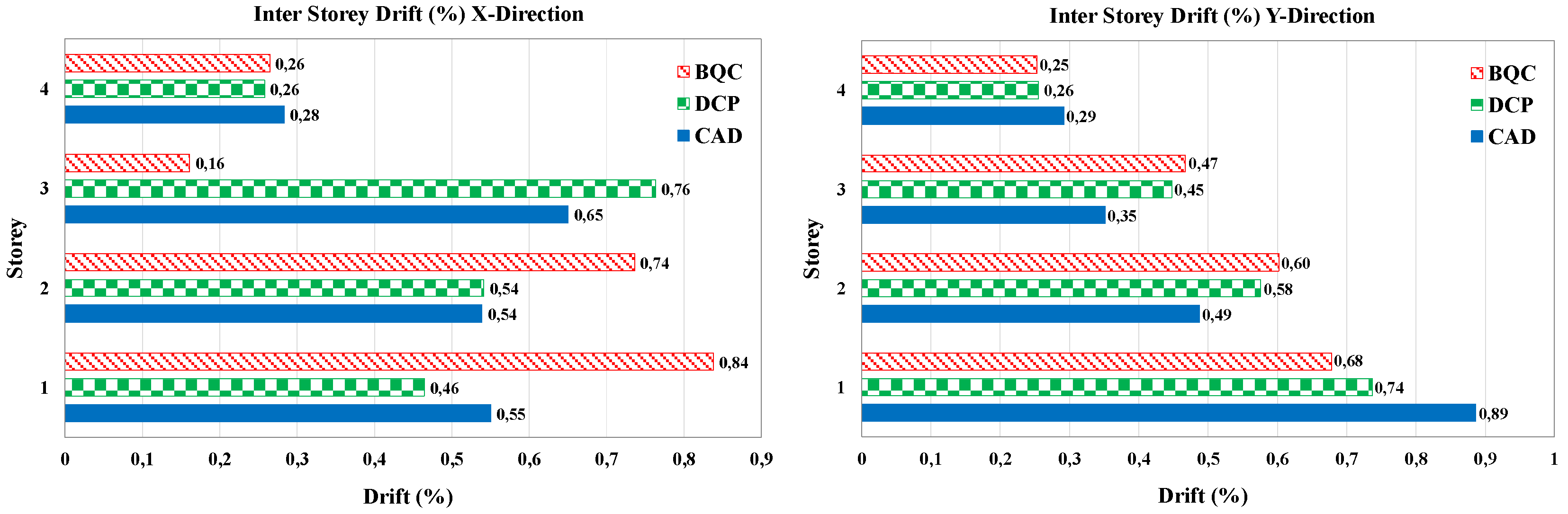

The main differences of the previous procedure with that proposed in [

19] depend 1) on the method for evaluation of the displacement demand based on the equivalent damping. The equivalent damping is evaluated on the basis of the hysteretic behavior of dissipative bracing and existing bare frame, as defined in procedure 2 of the Italian Building Code [

40], according to a concept widely acknowledged in the literature proposed by Shibata and Sozen [

41]; 2) the modal properties of the bare frame are used to evaluate the target displacement demand of the DBF, by assuming a design pattern of the DBF displacements along the height of the frame that is proportional to the first modal shape of the bare frame, and a target value of the maximum inter-story drift; 3) according to item 2), the distribution of the stiffness and resistance characteristics of the dissipative braces are proportional to those of the frame.

Regarding the 1st issue, the equivalent bilinearized SDOF system differs from the one described in the previous procedure by the stiffness of the elastic branch, which here is settled as the initial elastic one rather than the secant value at 0.6

Vbmax as done in the previous procedure, and the shape of the second branch, which is characterized by a post-elastic stiffness

KH>0, evaluated together with the displacement demand

d*max and the yielding force

F*y on the basis of the following relations:

being

the effective period evaluated on the basis of the effective stifness, i.e., secant stiffness

keff=F*u/d*max, E*H the energy absorbed (the area under the force-displacement curve) by the actual SDOF system up to the demand displacement, and

a coefficient that reflects the energy dissipation capacity of the system, that is settled

=1, 0.66, 0.33 for structures with high, medium, or low damping capability respectively, the latter depending on the stability of the hysteresis cycles. Equation 5c is obtained by imposing that the area under the equivalent bilinear curve is equal to

E*H. An iterative procedure is used to find the equivalent damping value and the period of vibration

T* which are consistent with the displacement demand.

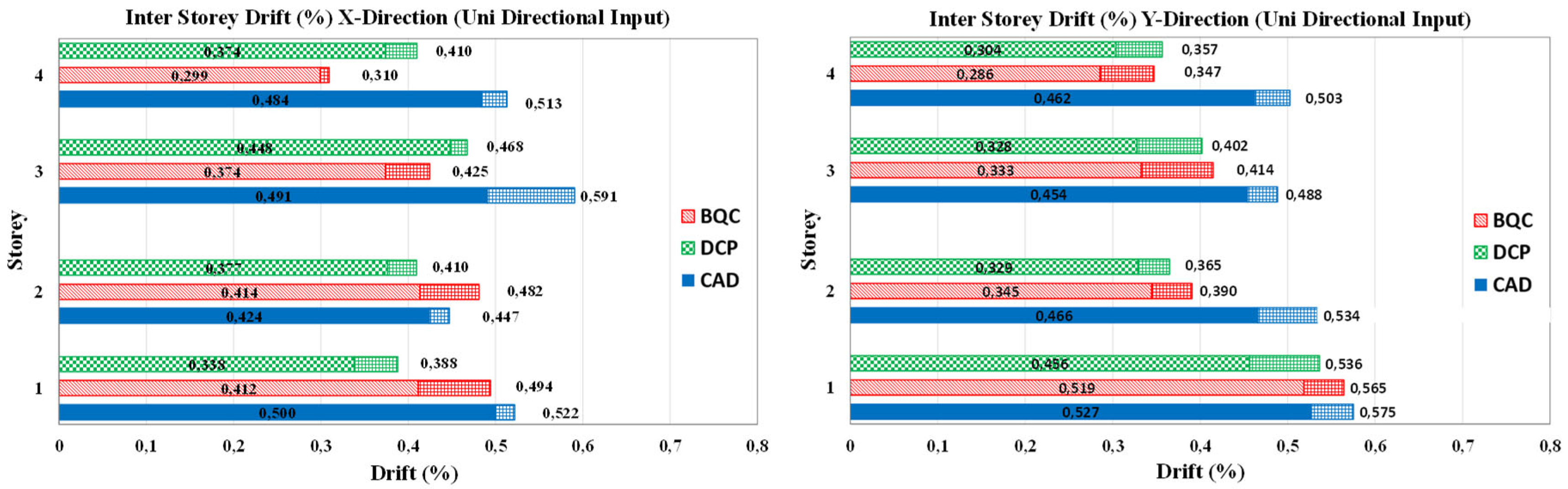

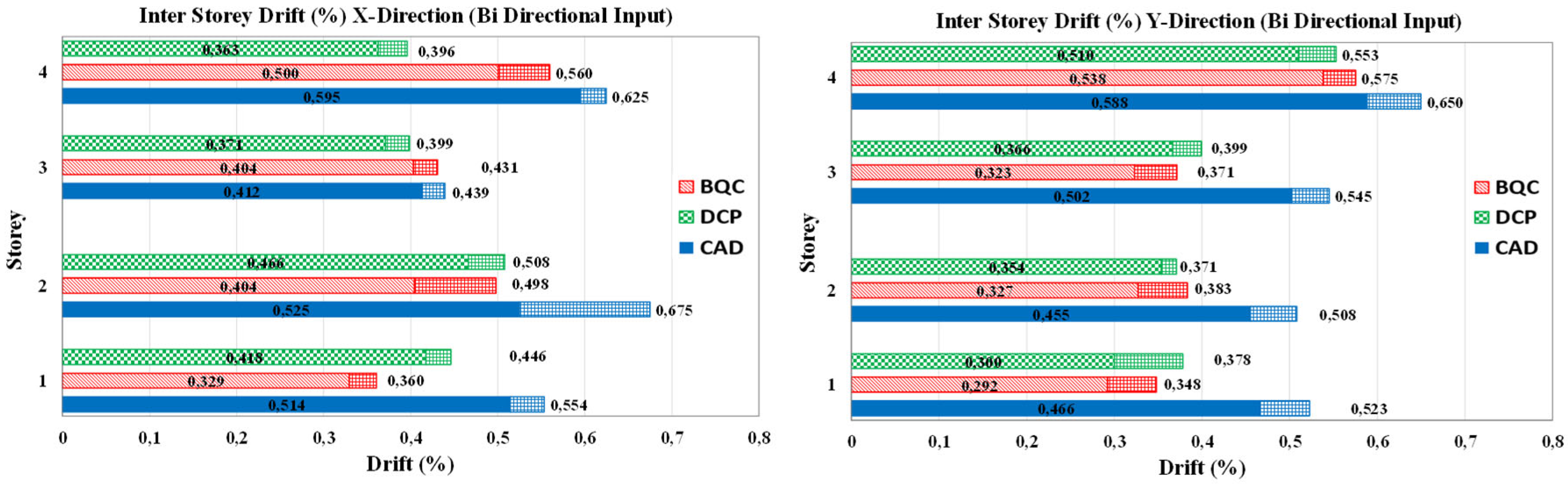

The main steps of this procedure can be summarized, as shown in the flowchart in

Figure 2a and ADRS in

Figure 2b,c, as follows:- the main capacity curve of the bare frame is evaluated using static nonlinear analysis, and the MDOF converted into equivalent SDOF system as described in the previous method; the target displacement of the system

dmax is chosen according to the design performance that is required to the dissipative bracing. The authors suggested to choose the target displacement in order to protect both structural and non-structural elements, corresponding to a maximum inter-story drift of the dissipative braced frame

Δdi,max,DBF/hi in the range 0.5% ÷ 0.75%, being

hi the inter-story height of the ith story; thus, the target value of the top story displacement of the DBF is evaluated as

The target top story displacement of the DBF is converted in the target displacement

of the DBF equivalent SDOF, and the capacity curve of SDOF system is converted into equivalent bilinear curve with hardening. Then, the characteristic parameters of the equivalent DB system are designed depending on the design value of the dissipative bracing ductility

μDB=

, and the equivalent damping of the damped brace

*

eq,DB=63.7 (

μDB -1)/

μDB. The latter can be chosen in the range 4≤

μDB ≤10, according to the dissipative device technology. Then, the equivalent viscous damping

*

eq,BDF, yielding displacement

, and ultimate strength

of the DBF SDOF equivalent system, i.e., the strength at the maximum displacement

=

(xx=BF,DB,DBF) are determined by the iterative procedure based on equations 5,6, 7a-d, as follows:

When the suitable damping and yield strength of the braced frame has been determined, the strength of the SDOF dissipative bracing

is obtained as

. Thus, for each brace, the strength

(equation (8)) and stiffness

(equation (9)) has been determined as follows:

being

nd the number of the bracing at each story, and α

ij the inclination of the j

th bracing of the i

th story.

The BQC procedure is particularly efficient for regular bare frame, as it is able to take into account the high hysteretic capacities of the bracing systems equipped with dissipative devices through the evaluation of the equivalent damping. However, it leads to an oversizing of the bracing due to the choice of designing the strengthened structure with the same modal shape as the bare frame, assuming a highly precautionary design displacement of the braced structure in the presence of a marked irregularity in the structure to be strengthened (see eq.6), characterized by a value of much larger than 1/np (np being the number of story), a value that would characterize the behavior of a structure designed to exhibit a constant interstory drift.

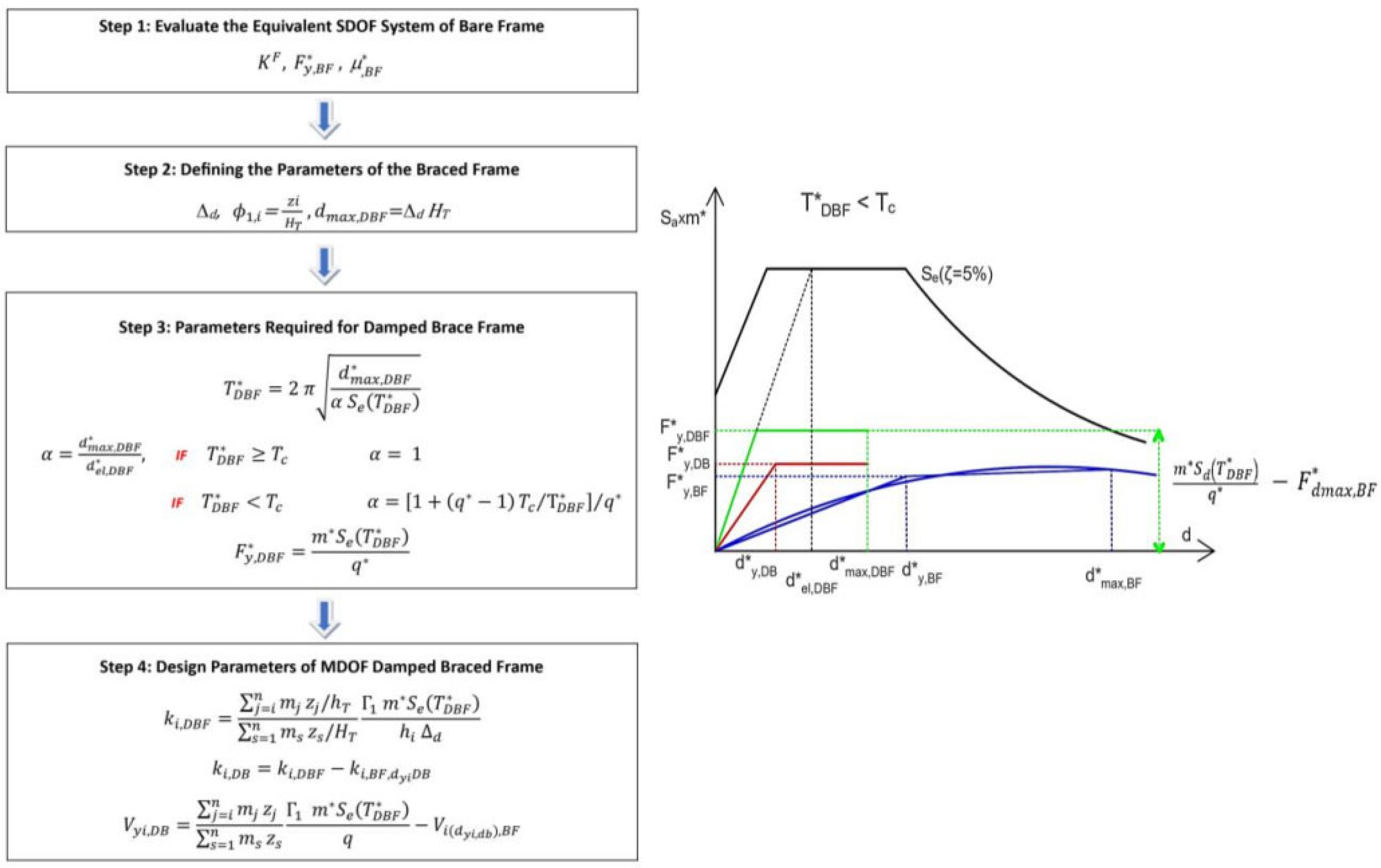

2.3. Simplified Method (CAD)

A simplified method is derived in order to investigate the efficiency of procedures that aim to mitigate the effect of possible irregularity along the height of the bare frame. The main difference with the previous method, besides using elementary relations that are easy to understand by the common practitioner, lies in the desire to obtain for the braced structure a displacement profile characterized by constant inter-story drift along the height. The procedure aims at obtaining uniform damage in the presence of earthquakes of unexpected intensity, and to reduce the amount of material used for the braces.

According to the simplified procedure, characterized by a flowchart and a representation in the ADRS shown in

Figure 3a and 3b respectively, once the design drift

Δd is chosen, the target eigenvector of the BDF structure is settled as

=

zi/HT , being

zi the height of i

th story above the level of application of the seismic action, and

HT the total height of the frame. The target displacement is evaluated as

= Δd * HT, the mass of the equivalent SDOF as

m* =

, and the first mode transformation factor Γ

1,DBF=

. In order to evaluate the behavior of the bare frame, as it will be exhibited in the BDF, a pushover curve is evaluated by using a pattern of the seismic force “triangular”, i.e., proportional to the product of

mi * zi. Then, the design of the stiffness of SDOF bracing system DB is performed on the basis of the modified Equal Displacement Rule (EDR1) suggested by the [

38] and Italian seismic codes [

40]

= for

, or the amplified value

being

, for

. The value of behavior factor

should be chosen in order to optimize the dynamic behavior and limit the variation of the axial force induced by the braces in the columns of the frame. To optimize the dynamic behavior,

should be chosen in the range 3≤

≤10 for

(as suggested by [

22], where recommended values are in the narrowest range 4 ≤

≤6), while in order to mitigate the expected increment of the displacement demand for

(according to [

22] a limit recommended value is

=3). Thus, the design values of the period of vibration and the yielding strength of the SDOF DBF can be evaluated as follows:

Once the global parameters of the SDOF DBF have been evaluated, the stiffness

and the strength

of the actual MDOF DB system can be easily evaluated on the basis of the lateral force method, taking into account that the stiffness and the strength of the DBF at each story are the sum of those of the DB and BF. The latter

kiBF, dyiDB should be evaluated in correspondence of the design value of the inter-story drift at the yielding of the brace d

yi,DB. Thus, the following expressions are obtained:

One iteration to evaluate Vyi,DB can be required.