Submitted:

12 August 2024

Posted:

13 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Definitions

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Infections

3.3. Bacteria and Sites of Infection

3.4. Infections upon Admission

3.5. Infections during Follow-Up

3.6. Liver Related Decompensations and ACLF in Infected Patients Compared with Non-Infected Patients

| INFECTED PATIENTS N=37 |

NO INFECTED PATIENTS N=78 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male), n(%) | 25 (67.5%) | 63 (81%) | 0.12 |

| Age, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 50 (43- 57) | 51 (44–58) | 0.87 |

| Race, n(%) | Caucasian, 30 (87%) | Caucasian, 68 (87%) | 0.91 |

| BASELINE | |||

| Maddrey score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 45 (31.5–61.5) | 37 (18–51) | 0.020 |

| MELD score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 21 (18-25) | 18 (15-21) | 0.002 |

| Child-Pugh score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 11 (10–12) | 10 (9-11) | 0.001 |

| Bilirubin serum (mg/dL), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 10.4 (5.4-17.5) | 6.5 (4.4-10.5) | 0.010 |

| INR, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 1.63 (1.4-1.84) | 1.48 (1.14-1.80) | 0.047 |

| Albumin (g/dl), median (IQR) P25–P75 | 2.5 (2.3-2.75) | 2.8 (2.5-3.4) | 0.002 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 0.7 (0.6-1.0) | 0.65 (0.53-0.86) | 0.45 |

| COMPLICATIONS | |||

| HD, n(%) | 23 (62%) | 22 (28%) | 0.001 |

| Ascites, n(%) | 16 (43%) | 18 (23%) | 0.046 |

| HE, n (%) | 15 (41%) | 10 (13%) | 0.001 |

| GIB, n (%) | 4 (11%) | 5(6.4%) | 0.41 |

| AKI, n(%) | 6 (16%) | 5 (6.4%) | 0.095 |

| Vasoactive support | 6 (16%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0.002 |

| ICU, n (%) | 10 (27%) | 2 (2.5%) | 0.001 |

| ACLF, n(%) | 12 (32.4%) | 5 (6.4%) | 0.001 |

| Death, n (%) | 6 (16%) | 3 (4%) | 0.021 |

| IQR: interquartile range, HD: hepatic decompensations, HE: hepatic encephalopathy, GIB: gastrointestinal bleeding, AKI: acute kidney injury, ICU: intensive care unit, ACLF: acute-on-chronic liver failure, During hospitalization, the assessment focused solely on infections and complications, as not all patients recorded complete analytical values, nor was sufficient clinical information available after discharge. | |||

| ID-Episode | CE | Infection | Bacteria | SIRS | ACLF | Resolution infection | Cause of death | Antibiotic | MRB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2- 1 | Yes | CRBSI | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Yes | Yes | Yes | ACLF | Meropenem | |

| P4- 2 | Yes | UTI | Klebsiella aerogenes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cefazolin | ||

| Cellulitis | Staphylococcus aureus | Cloxacillin | |||||||

| CRBSI | Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus haemolyticus | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | |||||||

| P5- 3 | Yes | UTI | Escherichia coli | No | No | Yes | Ceftriaxone | ||

| P6- 4 | Yes | Aspiration Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Meropenem | ||

| P20- 5 | No | UTI | Escherichia coli | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | ||

| P21- 6 | Yes | Aspiration Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | Yes | Yes | Yes | ACLF | Ceftazidime | |

| P28- 7 | Yes | Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | ||

| P38- 8 | No | Cellulitis | Staphylococcus aureus | No | No | Yes | Linezolid | Yes | |

| P44- 9 | No | Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | ||

| P50- 10 | Yes | Bacteremia | Klebsiella oxytoca | Yes | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | ||

| P51- 11 | Yes | Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | ||

| P25- 12 | No | SBP | Staphylococcus aureus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Ceftriaxone | ||

| Bacteremia | Staphylococcus aureus | Cefazolin | |||||||

| Aspiration Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | |||||||

| P61- 13 | Yes | Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | Yes | Yes | Yes | ACLF | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | |

| P63- 14 | No | SBP | Escherichia coli | No | No | Yes | Ceftriaxone | ||

| Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | ||||||||

| P68- 15 | Yes | Bacteriemia | Escherichia coli | Yes | No | Yes | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | ||

| P73- 16 | No | Aspiration Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | ||

| P78- 17 | Yes | SBP | Enterobacter cloacae | Yes | Yes | No | SBP, ACLF | Ceftriaxone | |

| Aspiration Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | |||||||

| SBP | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Meropenem + Daptomycin | Yes | ||||||

| P82- 18 | No | Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | Yes | Yes | No | ACLF | Meropenem | |

| CRBSI | Staphylococcus hemolyticus, Staphylococcus epidermidis. *Candida albicans | Meropenem + Daptomycin, *Anidulafungin | Yes | ||||||

| P87- 19 | No | Aspiration Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | ||

| P102- 20 | No | Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Ceftriaxone | ||

| P103- 21 | Yes | Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | Yes | Yes | Yes | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | ||

| P106- 22 | No | Aspiration Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Piperacillin-Tazobactam |

| Corticosteroids n= 49 | No Corticosteroids n= 66 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Male, n (%) | 36 (73.5%) | 51 (77%) | 0.63 |

| Age median (IQR) P 25-75 | 51 (44-58) | 48 (43-56) | 0.16 |

| Maddrey score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 34 (18-50) | 41 (28-58) | 0.27 |

| MELD score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 19 (15-22) | 19 (16-22) | 0.88 |

| Child-Pugh score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 10 (9-11) | 10 (9-11) | 0.44 |

| Complications during hospitalization | |||

| Infections, n (%) | 9 (18%) | 13 (20%) | 0.76 |

| HD, n(%) | 18 (36%) | 27 (40%) | 0.65 |

| Ascites, n(%) | 14 (28%) | 20 (30%) | 0.89 |

| HE, n (%) | 10 (20%) | 15 (22%) | 0.73 |

| GIB, n (%) | 2 (4%) | 7 (10%) | 0.19 |

| AKI, n(%) | 7 (14%) | 4 (6%) | 0.14 |

| Vasoactive support, n (%) | 3 (6%) | 4 (6%) | 0.98 |

| ICU, n (%) | 5 (10%) | 7 (11%) | 0.94 |

| ACLF, n(%) | 4 (8%) | 13 (20%) | 0.08 |

| Death, n (%) | 4 (8%) | 5 (7.5%) | 0.92 |

| Follow up 90 days | |||

| Infections, n (%) | 3 de 45 (6%) | 11 de 61 (18%) | 0.08 |

| Number of infections, n (%) | 3 de 45 (6%) | 16 de 61 (26%) | 0.09 |

| Death, n (%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (1.5%) | 0.82 |

| ID-Episode | CE | Infection | Bacteria | SIRS | ACLF | Resolution infection | Cause of death | Antibiotic | MRB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P5- 1 | Yes | Bacteremia | Staphylococcus epidermidis | No | No | Yes | Ceftriaxone | ||

| P19- 2 | Yes | Cellulitis | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Ceftriaxone, Teicoplanin | ||

| P28- 3 | Yes | Pneumonia | Staphylococcus aureus | Yes | Yes | No | Septic Shock | Meropenem + Linezolid | |

| Intra-abdominal | Non-isolated bacteria | ||||||||

| P33- 4 | Yes | SBP | Enterococcus faecium | Yes | No | Yes | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | ||

| P39- 5 | Yes | Cellulitis | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | ||

| P45- 6 | Yes | Bacteriemia | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Yes | Yes | Yes | Meropenem, Teicoplanin | ||

| Bacteremia | Enterococcus faecium | Yes | |||||||

| P47- 7 | Yes | SBP | Serratia marcescens | No | No | Yes | Ceftriaxone | ||

| P26- 8 | No | Bacteremia | Staphylococcus aureus | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | ||

| P74- 9 | Yes | UTI | Escherichia coli | No | No | Yes | Ceftriaxone | ||

| P76- 10 | No | Cellulitis | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Cefadroxil | ||

| P83- 11 | No | Cellulitis | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | ||

| P92- 12 | Yes | SBP | Klebsiella pneumoniae | No | No | Yes | Ceftriaxone | ||

| UTI | Klebsiella pneumoniae | No | No | Yes | Ciprofloxacin | ||||

| UTI | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Yes | Yes | yes | Cefotaxime + Clindamycin | Yes | |||

| Cellulitis | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | ||||

| P105- 13 | Yes | Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | ||

| P108- 14 | Yes | SBP | Acinetobacter pitti | Yes | Yes | Yes | ACLF | Meropenem |

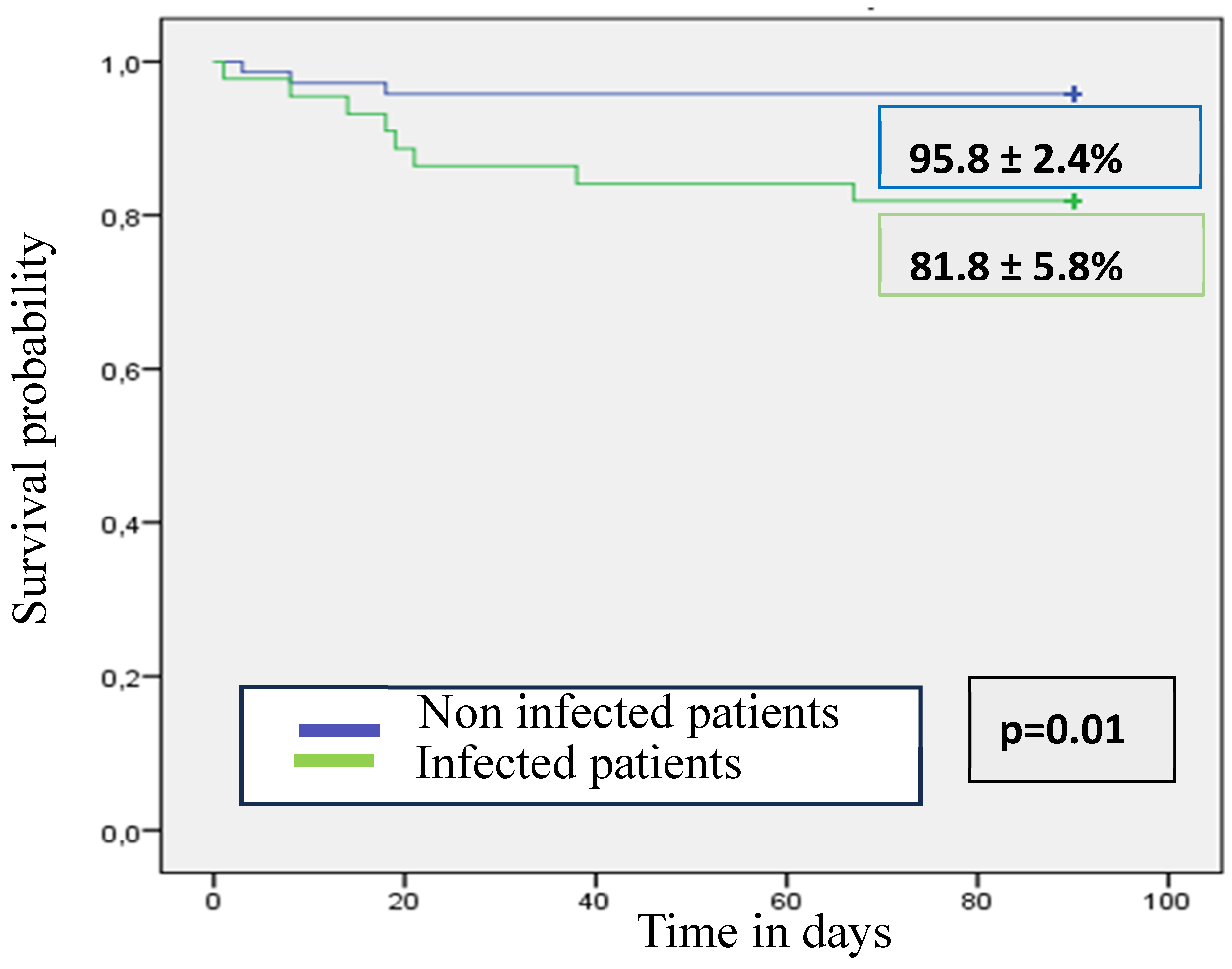

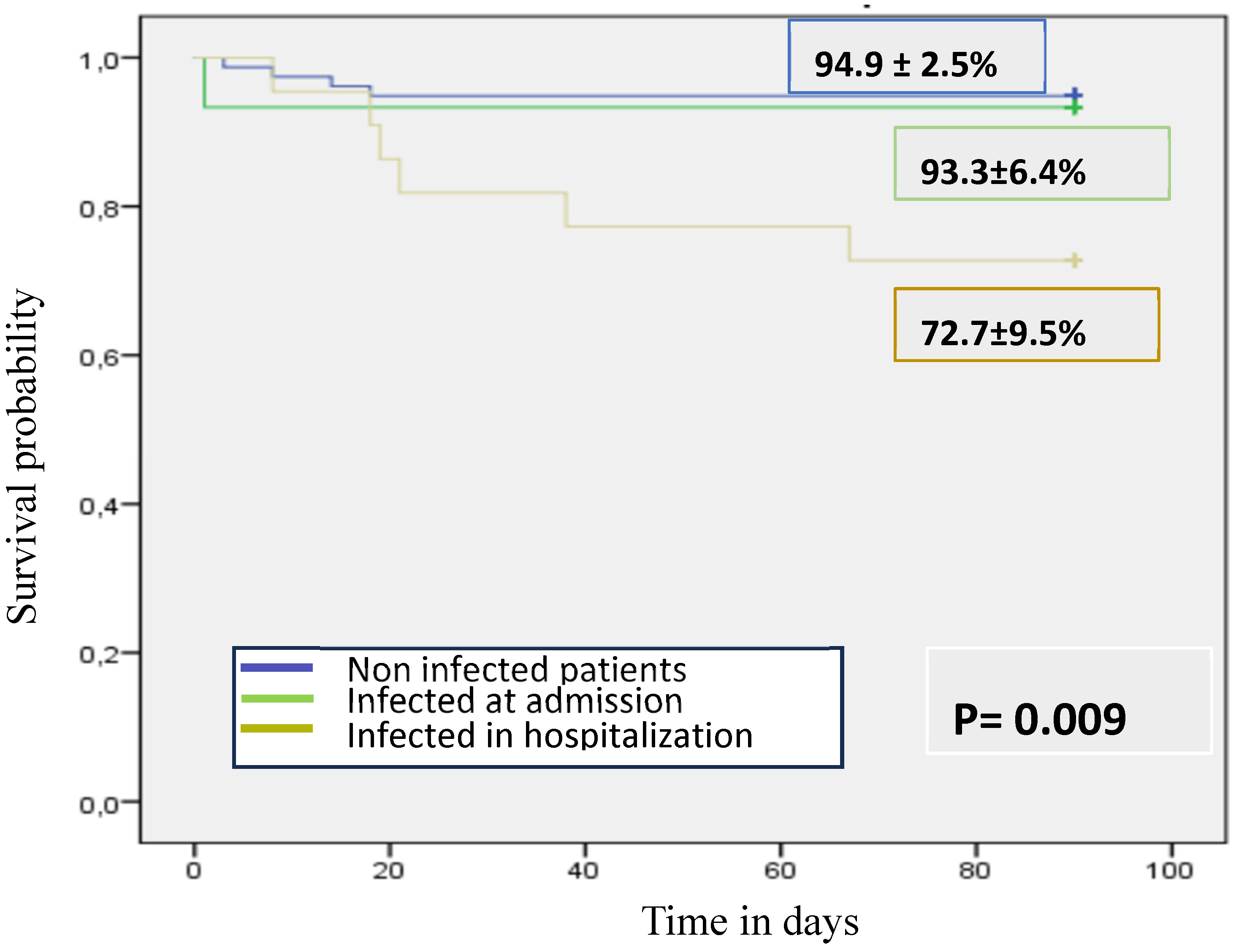

3.7. Mortality and Predictors of Mortality in Infected Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jepsen, P.; Younossi, Z.M. The global burden of cirrhosis: A review of disability adjusted life-years lost and unmet needs. J Hepatol 2021, 75, S3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasper, P.; Lang, S.; Steffen, H.M.; Demir, M. Management of alcoholic hepatitis: A clinical perspective. Liver Int 2023, 43, 2078–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, V.; Caballería, J.; Vargas, V.; Bataller, R.; Altamirano, J. Alcoholic hepatitis: How far are we and where are we going? Ann Hepatol 2016, 15, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vergis, N.; Atkinson, S.R.; Thursz, M.R. Assessment and management of infection in alcoholic hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis 2020, 40, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albillos, A.; Martin-Mateos, R.; Van der Merwe, S.; Wiest, R.; Jalan, R.; Álvarez-Mon, M. Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 19, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, R.; Im, G.; Jones, F.; Hernández, O.P.; Nahas, J.; Kumar, A.; Wheatley, D.; Sinha, A.; Gonzalez-Reimers, E.; Sanchez-Pérez, M.; et al. Clinical and microbiological features of infection in alcoholic hepatitis: An international cohort study. J Gastroenterol 2017, 52, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bataller, R.; Arab, J.P.; Shah, V.H. Alcohol-associated hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 2436–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.K.; Bataller, R.; Ahn, J.; Kamath, P.S.; Shah, V.H. ACG Clinical Guideline: Alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2018, 113, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louvet, A.; Wartel, F.; Castel, H.; Dharancy, S.; Hollebecque, A.; Canva-Delcambre, V.; Deltenre, P.; Mathurin, P. Infection in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids: Early response to therapy is the key factor. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelena, J.; Altamirano, J.; Abraldes, J.G.; Affò, S.; Morales-Ibanez, O.; Sancho-Bru, P.; Dominguez, M.; García-Pagán, J.C.; Fernández, J.; Arroyo, V.; et al. Systemic inflammatory response and serum lipopolysaccharide levels predict multiple organ failure and death in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2015, 62, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thursz, M.R.; Richardson, P.; Allison, M.; Austin, A.; Bowers, M.; Day, C.P.; Downs, N.; Gleeson, D.; MacGilchrist, A.; Grant, A.; et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2015, 372, 1619–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergis, N.; Atkinson, S.R.; Knapp, S.; Maurice, J.; Allison, M.; Austin, A.; Forrest, E.H.; Masson, S.; McCune, A.; Patch, D.; et al. In patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, prednisolone increases susceptibility to infection and infection-related mortality, and is associated with high circulating levels of bacterial DNA. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hmoud, B.S.; Patel, K.; Bataller, R.; Singal, A.K. Corticosteroids and occurrence of and mortality from infections in severe alcoholic hepatitis: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Liver Int 2016, 36, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, C.; Ventura-Cots, M.; Sala, M.; Calafat, M.; Garcia-Retortillo, M.; Cirera, I.; Cañete, N.; Soriano, G.; Poca, M.; Simón-Talero, M.; et al. Effect of rifaximin on infections, acute-on-chronic liver failure and mortality in alcoholic hepatitis: A pilot study (RIFA-AH). Liver Int 2022, 42, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sersté, T.; Cornillie, A.; Njimi, H.; Pavesi, M.; Arroyo, V.; Putignano, A.; Weichselbaum, L.; Deltenre, P.; Degré, D.; Trépo, E.; et al. The prognostic value of acute-on-chronic liver failure during the course of severe alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol 2018, 69, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabb, D.W.; Bataller, R.; Chalasani, N.P.; Kamath, P.S.; Lucey, M.; Mathurin, P.; McClain, C.; McCullough, A.; Mitchell, M.C.; Morgan, T.R.; et al. Standard definitions and common data elements for clinical trials in patients with alcoholic hepatitis: Recommendation from the NIAAA alcoholic hepatitis consortia. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeli, P.; Bernardi, M.; Villanueva, C.; Francoz, C.; Mookerjee, R.P.; Trebicka, J.; Krag, A.; Laleman, W.; Gines, P. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for management of patients with decompensated cirrosis. J Hepatol 2018, 69, 406–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo, V.; Moreau, R.; Jalan, R.; Ginès, P.; EASL-CLIF Consortium CANONIC Study. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: A new syndrome that will re-classify cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2015, 62, S131–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, R.C.; Balk, R.A.; Cerra, F.B.; Dellinger, R.P.; Fein, A.M.; Knaus, W.A.; Schein, R.M.; Sibbald, W.J. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 1992, 101, 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanda, A.D.; Sinha, A.; Hunt, V.; Saleem, S.; Cramp, M.E.; Collins, P. L Infection does not increase long-term mortality in patients with acute severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with CS. World J Gastroenterol 2017, 23, 2052–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beisel, C.; Blessin, U.; Schulze Zur Wiesch, J.; Wehmeyer, M.H.; Lohse, A.W.; Benten, D.; Kluwe, J. Infections complicating severe alcoholic hepatitis: Enterococcus species represent the most frequently identified pathogen. Scand J Gastroenterol 2016, 51, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piano, S.; Singh, V.; Caraceni, P.; Maiwall, R.; Alessandria, C.; Fernandez, J.; Soares, E.C.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, S.E.; Marino, M.; et al. Epidemiology and effects of bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis worldwide. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 1368–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, A.; Carmeli, Y.; Omrani, A.S.; Moore, L.S.P.; Tawadrous, M.; Irani, P. Ceftazidime-avibactam for the treatment of serious Gram-negative infections with limited treatment options: A systematic literature review. Infect Dis Ther 2021, 10, 1989–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sipeki, N.; Antal-Szalmas, P.; Lakatos, P.L.; Papp, M. Immune dysfunction in cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20, 2564–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.; Levitsky, J. Infection and alcoholic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 2016, 20, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, G.; Saha, B. Alcohol’s effect on host defense. Alcohol Res 2015, 37, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karakike, E.; Moreno, C.; Gustot, T. Infections in severe alcoholic hepatitis. Ann Gastroenterol 2017, 30, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Kamath, P.S.; Reddy, K.R. The evolving challenge of infections in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 2317–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo, V.; Moreau, R.; Jalan, R. Acute-on-chronic liver failure. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 2137–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trebicka, J.; Fernandez, J.; Papp, M.; Caraceni, P.; Laleman, W.; Gambino, C.; Giovo, I.; Uschner, F.E.; Jimenez, C.; Mookerjee, R.; et al. The PREDICT study uncovers three clinical courses of acutely decompensated cirrhosis that have distinct pathophysiology. J Hepatol 2020, 73, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trebicka, J.; Fernandez, J.; Papp, M.; Caraceni, P.; Laleman, W.; Gambino, C.; Giovo, I.; Uschner, F.E.; Jansen, C.; Jimenez, C.; et al. PREDICT identifies precipitating events associated with the clinical course of acutely decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2021, 74, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrest, E.; Bernal, W. The role of prophylactic antibiotics for patients with severe alcohol-related hepatitis. JAMA 2023, 329, 1552–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, Z.; Badal, J.; Nawras, M.; Battepati, D.; Farooq, U.; Arif, S.F.; Lee-Smith, W.; Aziz, M.; Iqbal, U.; Nawaz, A.; et al. Role of rifaximin in the management of alcohol-associated hepatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 38, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n=115 | |

|---|---|

| Medical History | |

| Sex (male), n(%) | 88 (76.5%) |

| Age, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 50 (44-58) |

| Race, n(%) | Caucasian 98 (85%) |

| BMI, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 27 (24-31) |

| Arterial hypertension, n(%) | 35 (30.4%) |

| Diabetes, n(%) | 15 (13%) |

| Dyslipidemia, n(%) | 23 (20%) |

| Metabolic syndrome, n(%) | 16 (14%) |

| Obesity, n(%) | 28 (24%) |

| Chronic renal failure, n(%) | 0 (0%) |

| Ischemic heart disease, n(%) | 4 (3.4%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n(%) | 7 (6%) |

| Hepatic cirrhosis, n(%) | 68 (59%) |

| History of hepatic decompensation, n(%) | 28 (24%) |

| Previous alcohol-related hepatitis, n(%) | 23 (20%) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma, n(%) | 0 (0%) |

| Prophylactic antibiotics, n(%) | 2 (1.7%) |

| Hospital admission (BASELINE) | |

| Hepatic cirrhosis, n(%) | 81 (70%) |

| Hepatic decompensation, n(%) | 64 (56%) |

| Infection, n(%) | 18 (16%) |

| Ascites, n(%) | 59 (51%) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy, n (%) | 15 (13%) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding, n (%) | 7 (6%) |

| Acute kidney injury, n(%) | 13 (11%) |

| Acute on chronic liver failure, n(%) | 7 (6%) |

| Maddrey score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 40 (20-50) |

| MELD score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 19 (16-22) |

| MELD Na score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 22 (19-22) |

| MELD 3.0 score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 23 (20-26) |

| Child-Pugh score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 10 (9-11) |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 7.4 (4.8-12) |

| INR, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) |

| Albumin (g/dL), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 2.7 (2.4-3.1) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 0.7 (0,5-0.9) |

| AST (UI/L), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 147 (102-264) |

| ALT (UI/L), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 61 (35-89) |

| GGT (UI/L), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 593 (223-1461) |

| ALP (UI/L), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 204 (150-328) |

| CRP (mg/dL), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 2.5 (1-5.5) |

| Leucocytes (10^9/L), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 8.2 (6.1-11.6) |

| Platelets 10^9/L | 104 (64-153) |

| Site | Number of infections, (%) | Positive cultures | Bacteria, (n) | Gram positive or gram negative, (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest | 24 (35%) | 3 | Streptoccocus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Clamydia pneumoniae | Gram positive (2) Gram negative (1) |

| Skin | 14 (20%) | 3 | Staphylococcus aureus (2) Staphylococcus aureus* | Gram positive (3) |

| Blood | 11 (16%) | 11 | Acinetobacter baumannii Staphylococcus hemolyticus (2) Staphylococcus hemolyticus* Staphylococcus epidermidis (4) Enterococcus faecalis*, Klebsiella oxytoca, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecium | Gram-positive (10) Gram-negative (4) |

| Abdominal (Ascites) | 11 (16%) | 10 | Staphylococcus aureus (2) Acinetobacter baumannii Staphylococcus hemolyticus Escherichia coli, Enterobacter cloacae, Klebsiella pneumoniae* Enterococcus faecium, Serratia marcenses, Acinetobacter pittii | Gram-positive (4) Gram-negative (6) |

| Urinary tract | 9 (13%) | 9 | Escherichia coli (5), Klebsiella pneumoniae (2), Klebsiella pneumoniae* Enterococcus faecalis, Klebsiella aerogenes | Gram-positive (1) Gram-negative (9) |

| TOTAL | 69 | 36 | 40 | Gram-positive (20) Gram-negative (20) |

| * Multidrug-resistant bacteria | ||||

| ID-Episode | Infection | Bacteria | SIRS | ACLF | Resolution infection | Antibiotics | MRB |

| P4- 1 | SBP | Staphylococcus aureus | Yes | No | Yes | Cefazolin | |

| P6- 2 | Cellulitis | Non-isolated bacteria | Yes | No | Yes | Levofloxacin + Clindamycin | |

| P8- 3 | Aspiration Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | Yes | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | |

| P17- 4 | Cellulitis | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | |

| P19- 5 | Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | Yes | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | |

| P33- 6 | Bacteremia | Acinetobacter baumannii + Staphylococcus haemolyticus | Yes | No | Yes | Ciprofloxacin | |

| SBP | |||||||

| P62- 7 | Cellulitis | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | |

| P69- 8 | Cellulitis | Non-isolated bacteria | Yes | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | |

| P74- 9 | UTI | Escherichia coli | No | No | Yes | Ceftriaxone | |

| P76- 10 | Pneumonia | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cefotaxime + Azithromycin | |

| P79- 11 | Pneumonia | Chlamydia pneumoniae | No | No | Yes | Levofloxacin | |

| P82- 12 | UTI | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Yes | Yes | Yes | Meropenem | |

| P86- 13 | Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | |

| P26- 14 | Aspiration Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | |

| P27- 15 | Cellulitis | Staphylococcus aureus | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | |

| P89- 16 | Aspiration Pneumonia | Non-isolated bacteria | Yes | Yes | Yes | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | |

| Cellulitis | Non-isolated bacteria | ||||||

| P99- 17 | Cellulitis | Non-isolated bacteria | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | |

| P107- 18 | UTI | Escherichia coli + Enterococcus faecalis | No | No | Yes | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate |

| Infected patients n=18 |

No infected patients N=97 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male), n(%) | 12 (66.6%) | 75 (77,3%) | 0.28 |

| Age, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 45 (41.7- 55.7) | 51 (44–58) | 0.43 |

| Clinical History | |||

| BMI, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 27.3 (23-31.2) | 27.2 (24-31.7) | 0.86 |

| Arterial hypertension, n(%) | 5 (28%) | 30 (31%) | 0.79 |

| Diabetes, n(%) | 2 (11%) | 13 (13.4%) | 0.80 |

| Metabolic syndrome, n(%) | 2 (11%) | 14 (14.4%) | 0.70 |

| Obesity, n(%) | 7 (39%) | 21 (22%) | 0.11 |

| Chronic renal failure, n(%) | 0 | 4 (4%) | 0.91 |

| History of HD, n(%) | 6 (33.3%) | 22(22.6%) | 0.33 |

| Previous AH, n(%) | 5 (28%) | 18 (18.5%) | 0.36 |

| Prophylactic antibiotics, n(%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 0.17 |

| BASELINE | |||

| HC diagnosis, n(%) | 16 (88%) | 65 (67%) | 0.062 |

| HD, n(%) | 16 (88%) | 48 (49.5%) | 0.005 |

| Ascites, n(%) | 14 (78%) | 45 (46,4%) | 0.029 |

| HE, n (%) | 9 (50%) | 6 (6.2%) | 0.001 |

| GIB, n (%) | 0 | 7 (7.2%) | 0.25 |

| AKI, n(%) | 3 (16.6%) | 10 (10.3%) | 0.43 |

| ACLF, n(%) | 3 (16.6%) | 4 (4.1%) | 0.041 |

| Maddrey score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 48 (32–68.5) | 38 (18–51) | 0.022 |

| MELD score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 22 (19-25) | 19 (15-21) | 0.012 |

| MELD Na score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 24 (22-29) | 22 (19-26) | 0.037 |

| MELD 3.0 score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 25 (25-28) | 23 (20-25) | 0.013 |

| Child-Pugh score, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 11 (11–12) | 10 (9–11) | 0.011 |

| Bilirubin serum (mg/dL), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 9.89 (6.96–16.31) | 7.16 (4.53–11.62) | 0.084 |

| INR, median (IQR) P 25-75 | 1.8 (1.4–1.95) | 1.5 (1.15–1.8) | 0.027 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 0.63 (0.55–0.87) | 0.67 (0.54–0.88) | 0.81 |

| Albumin (g/dl), median (IQR) P25–P75 | 2.5 (2.3–2.7) | 2.8 (2.4–3.2) | 0.038 |

| CRP (mg/dL), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 3 (1.5-9.5) | 2.4 (0.9-5.2) | 0.31 |

| Leucocytes (10^9/L), median (IQR) P 25-75 | 8.2 (5.8–10.7) | 10.3 (6.6–13.2) | 0.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).