Submitted:

09 August 2024

Posted:

13 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

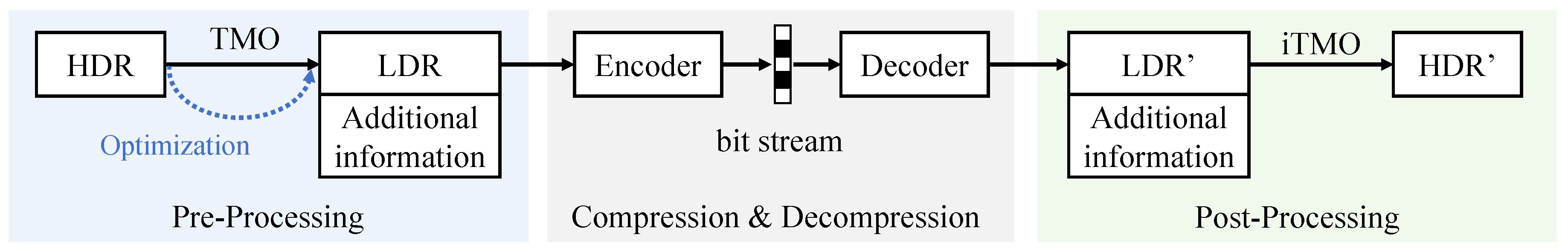

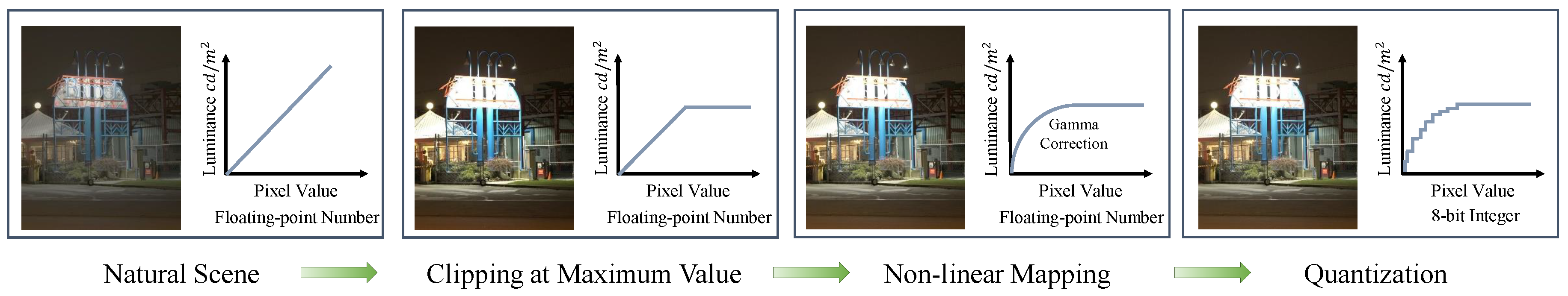

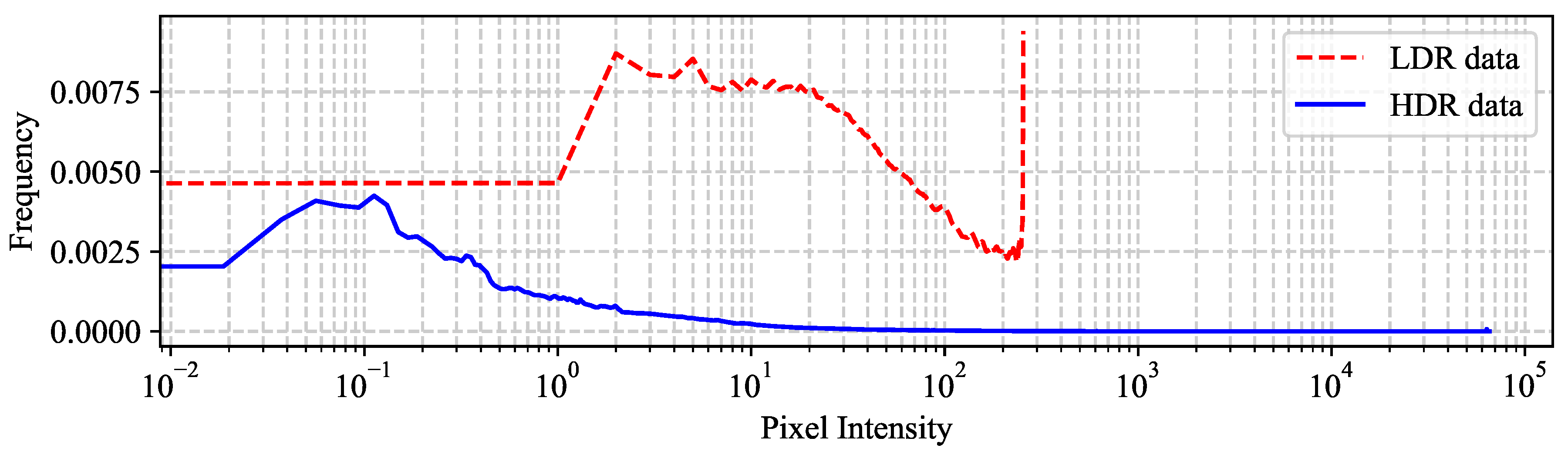

1. Introduction

2. Subjective HDR Image Quality Assessment Databases

| database | #Obs. | #Ref. | #Dis. | Dist. | TMO | Meth. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narwaria2013 [5] | 27 | 10 | 140 | JPEG | iCAM06 | ACR-HR |

| Narwaria2014 [23] | 29 | 6 | 210 | JPEG2000 | AL, Dur RG, RL Log |

ACR-HR |

| Korshunov2015 [6] | 24 | 20 | 240 | JPEG-XT | RG MT [24] |

DSIS |

| Valenzise2014 [7] | 15 | 5 | 50 | JPEG JPEG2000 JPEG-XT |

Mai | DSIS |

| Zerman2017 [25] | 15 | 5 | 50 | JPEG JPEG2000 |

Mai, PQ | DSIS |

| UPIQ [26] (HDR part) |

20 | 30 | 380 | JPEG JPEG-XT |

iCAM06 RG MT [24] |

- |

| HDRC [27] | 20 | 80 | 400 | JPEG-XT VVC |

RG PQ |

DSIS |

3. Objective HDR Image Quality Assessment Methods

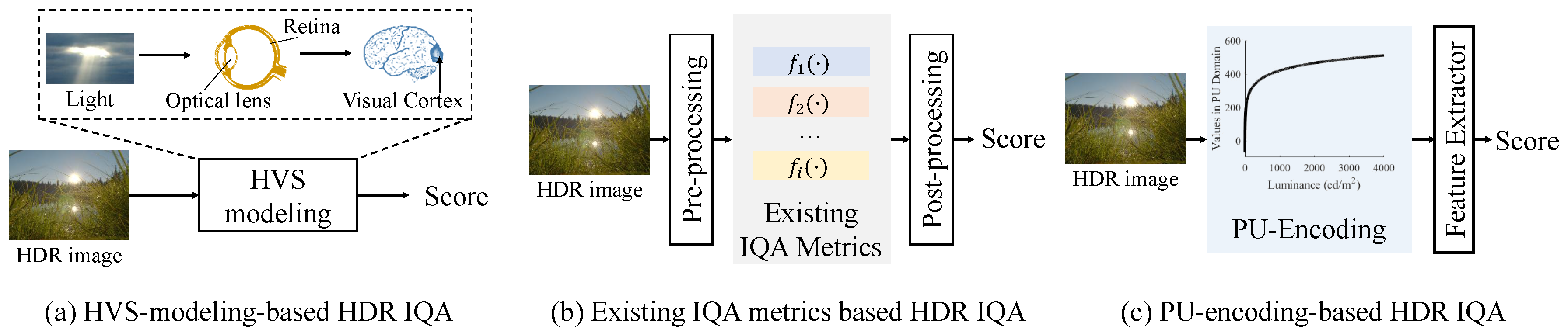

3.1. HVS-Modeling-Based HDR IQA Methods

3.2. PU-Encoding-Based HDR IQA Methods

3.3. Existing IQA Metrics Based HDR IQA Methods

| Method | Year | Classification | Major Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDR-VDP-1 [8] | 2005 | Full-Reference | HVS-modeling-based HDR IQA methods |

| DRIM [53] | 2008 | Full-Reference | HVS-modeling-based HDR IQA methods |

| HDR-VDP-2 [9] | 2011 | Full-Reference | HVS-modeling-based HDR IQA methods |

| HDR-VDP-2.2 [36] | 2015 | Full-Reference | HVS-modeling-based HDR IQA methods |

| HDR-VQM [11] | 2015 | Full-Reference | PU-encoding-based HDR IQA methods |

| Kottayil et al. [55] | 2017 | No-Reference | HVS-modeling-based HDR IQA methods |

| Jia et al. [58] | 2017 | No-Reference | PU-encoding-based HDR IQA methods |

| HDR-CQM [13] | 2018 | Full-Reference | Existing IQA metrics based HDR IQA methods |

| PU-PieAPP [26] | 2021 | Full-Reference | PU-encoding-based HDR IQA methods |

| HDR-VDP-3 [10] | 2023 | Full-Reference | HVS-modeling-based HDR IQA methods |

| LGFM [12] | 2023 | Full-Reference | PU-encoding-based HDR IQA methods |

| Cao et al. [14] | 2024 | Full-Reference | Existing IQA metrics based HDR IQA methods |

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HDR | High Dynamic Range |

| LDR | Low Dynamic Range |

| HVS | Human Visual System |

| IQA | Image Quality Assessment |

| TMO | Tone Mapping Operator |

| DSIS | Double-Stimulus Impairment Scale |

| ACR-HR | Absolute Category Rating with Hidden Reference |

| CSF | Contrast Sensitive Function |

| PU | Perceptual Uniform |

| PQ | Perceptual Quantizer |

| HLG | Hybrid-Log-Gamma |

| MOS | Mean Opinion Score |

| VDP | Visual Difference Predictor |

| OTF | Optical Transfer Function |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

References

- Metzler, C.A.; Ikoma, H.; Peng, Y.; Wetzstein, G. Deep optics for single-shot high-dynamic-range imaging. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2020, pp. 1375–1385.

- Shopovska, I.; Stojkovic, A.; Aelterman, J.; Van Hamme, D.; Philips, W. High-Dynamic-Range Tone Mapping in Intelligent Automotive Systems. Sensors 2023, 23, 5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, D.; Gómez, S.; Mauricio, J.; Freixas, L.; Sanuy, A.; Guixé, G.; López, A.; Manera, R.; Marín, J.; Pérez, J.M.; others. HRFlexToT: a high dynamic range ASIC for time-of-flight positron emission tomography. IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences 2021, 6, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, W.; Xing, J.; Zhang, X.; Tian, H.; Tang, H.; Bi, P.; Li, G.; Zhang, F. Extracting vegetation information from high dynamic range images with shadows: A comparison between deep learning and threshold methods. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2023, 208, 107805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narwaria, M.; Da Silva, M.P.; Le Callet, P.; Pepion, R. Tone mapping-based high-dynamic-range image compression: study of optimization criterion and perceptual quality. Optical Engineering 2013, 52, 102008–102008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korshunov, P.; Hanhart, P.; Richter, T.; Artusi, A.; Mantiuk, R.; Ebrahimi, T. Subjective quality assessment database of HDR images compressed with JPEG XT. 2015 seventh international workshop on quality of multimedia experience (QoMEX). IEEE, 2015, pp. 1–6.

- Valenzise, G.; De Simone, F.; Lauga, P.; Dufaux, F. Performance evaluation of objective quality metrics for HDR image compression. Applications of Digital Image Processing XXXVII. SPIE, 2014, Vol. 9217, pp. 78–87.

- Mantiuk, R.; Daly, S.J.; Myszkowski, K.; Seidel, H.P. Predicting visible differences in high dynamic range images: model and its calibration. Human Vision and Electronic Imaging X. SPIE, 2005, Vol. 5666, pp. 204–214.

- Mantiuk, R.; Kim, K.J.; Rempel, A.G.; Heidrich, W. HDR-VDP-2: A calibrated visual metric for visibility and quality predictions in all luminance conditions. ACM Transactions on graphics (TOG) 2011, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantiuk, R.K.; Hammou, D.; Hanji, P. HDR-VDP-3: A multi-metric for predicting image differences, quality and contrast distortions in high dynamic range and regular content. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.13625 2023.

- Narwaria, M.; Da Silva, M.P.; Le Callet, P. HDR-VQM: An objective quality measure for high dynamic range video. Signal Processing: Image Communication 2015, 35, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ni, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Kwong, S. High dynamic range image quality assessment based on frequency disparity. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2023.

- Choudhury, A.; Daly, S. HDR image quality assessment using machine-learning based combination of quality metrics. 2018 IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing (GlobalSIP). IEEE, 2018, pp. 91–95.

- Cao, P.; Mantiuk, R.K.; Ma, K. Perceptual Assessment and Optimization of HDR Image Rendering. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 22433–22443.

- Rousselot, M.; Le Meur, O.; Cozot, R.; Ducloux, X. Quality assessment of HDR/WCG images using HDR uniform color spaces. Journal of Imaging 2019, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, G.; Simmons, M. JPEG-HDR: A backwards-compatible, high dynamic range extension to JPEG. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2006 Courses; 2006; pp. 3–es.

- Sugiyama, N.; Kaida, H.; Xue, X.; Jinno, T.; Adami, N.; Okuda, M. HDR image compression using optimized tone mapping model. 2009 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing. IEEE, 2009, pp. 1001–1004.

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE transactions on image processing 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, J.; Johnson, G.M.; Fairchild, M.D. iCAM06: A refined image appearance model for HDR image rendering. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 2007, 18, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITU-T RECOMMENDATION, P. Subjective video quality assessment methods for multimedia applications 2008.

- https://hdr.sim2.it/.

- Narwaria, M.; Lin, W.; McLoughlin, I.V.; Emmanuel, S.; Chia, L.T. Fourier transform-based scalable image quality measure. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2012, 21, 3364–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narwaria, M.; Da Silva, M.P.; Le Callet, P.; Pépion, R. Impact of tone mapping in high dynamic range image compression. VPQM, 2014, pp. pp–1.

- Mantiuk, R.; Myszkowski, K.; Seidel, H.P. A perceptual framework for contrast processing of high dynamic range images. ACM Transactions on Applied Perception (TAP) 2006, 3, 286–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerman, E.; Valenzise, G.; Dufaux, F. An extensive performance evaluation of full-reference HDR image quality metrics. Quality and User Experience 2017, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailiuk, A.; Pérez-Ortiz, M.; Yue, D.; Suen, W.; Mantiuk, R.K. Consolidated dataset and metrics for high-dynamic-range image quality. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2021, 24, 2125–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ni, Z.; Chen, P.; Wang, S.; Kwong, S. HDRC: a subjective quality assessment database for compressed high dynamic range image. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics 2024, pp. 1–16.

- Reinhard, E.; Stark, M.; Shirley, P.; Ferwerda, J. Photographic tone reproduction for digital images. ACM Transactions on Graphics 2002, 21, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, F.; Dorsey, J. Fast bilateral filtering for the display of high-dynamic-range images. Proceedings of the 29th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques, 2002, pp. 257–266.

- Ashikhmin, M. A tone mapping algorithm for high contrast images. Proceedings of the 13th Eurographics workshop on Rendering, 2002, pp. 145–156.

- Richter, T. On the standardization of the JPEG XT image compression. 2013 Picture Coding Symposium (PCS). IEEE, 2013, pp. 37–40.

- Series, B. Methodology for the subjective assessment of the quality of television pictures. Recommendation ITU-R BT 2012, 500. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, Z.; Mansour, H.; Mantiuk, R.; Nasiopoulos, P.; Ward, R.; Heidrich, W. Optimizing a Tone Curve for Backward-Compatible High Dynamic Range Image and Video Compression. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2011, 20, 1558–1571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aydın, T.O.; Mantiuk, R.; Seidel, H.P. Extending quality metrics to full luminance range images. Human vision and electronic imaging xiii. SPIE, 2008, Vol. 6806, pp. 109–118.

- Miller, S.; Nezamabadi, M.; Daly, S. Perceptual signal coding for more efficient usage of bit codes. SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal 2013, 122, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narwaria, M.; Mantiuk, R.K.; Da Silva, M.P.; Le Callet, P. HDR-VDP-2.2: a calibrated method for objective quality prediction of high-dynamic range and standard images. Journal of Electronic Imaging 2015, 24, 010501–010501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Ortiz, M.; Mikhailiuk, A.; Zerman, E.; Hulusic, V.; Valenzise, G.; Mantiuk, R.K. From pairwise comparisons and rating to a unified quality scale. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2019, 29, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Yuan, F.; Lei, J.; Fang, Y.; Shao, X.; Kwong, S. VCRNet: Visual compensation restoration network for no-reference image quality assessment. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2022, 31, 1613–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, K.; Ma, K.; Wang, S.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: Unifying structure and texture similarity. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2020, 44, 2567–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, B.; Kwong, S. Causal Representation Learning for GAN-Generated Face Image Quality Assessment. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ding, K.; Yang, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, S. Opinion-Unaware Blind Image Quality Assessment using Multi-Scale Deep Feature Statistics. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, L.; Wang, S.; Kwong, S. Deep Feature Statistics Mapping for Generalized Screen Content Image Quality Assessment. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chen, B.; Chen, B.; Wang, M.; Wang, S.; Lin, W. Perceptual quality assessment of face video compression: A benchmark and an effective method. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhu, L.; Fang, Y.; Zhai, G.; Lin, W.; Wang, S. Adaptive Image Quality Assessment via Teaching Large Multimodal Model to Compare. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.19298 2024.

- Tian, Y.; Chen, B.; Wang, S.; Kwong, S. Towards Thousands to One Reference: Can We Trust the Reference Image for Quality Assessment? IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Li, D.; Pan, Z.; Sun, Z.; Kwong, S.; Hou, C. Fast intra prediction based on content property analysis for low complexity HEVC-based screen content coding. IEEE Transactions on Broadcasting 2016, 63, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Kwong, S.; Chang, Y.; Ren, Q. Consensus unsupervised feature ranking from multiple views. Pattern Recognition Letters 2008, 29, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanji, P.; Mantiuk, R.; Eilertsen, G.; Hajisharif, S.; Unger, J. Comparison of single image HDR reconstruction methodsâthe caveats of quality assessment. ACM SIGGRAPH 2022 conference proceedings, 2022, pp. 1–8.

- Daly, S.J. Visible differences predictor: an algorithm for the assessment of image fidelity. Human Vision, Visual Processing, and Digital Display III. SPIE, 1992, Vol. 1666, pp. 2–15.

- Deeley, R.J.; Drasdo, N.; Charman, W.N. A simple parametric model of the human ocular modulation transfer function. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics 1991, 11, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockman, A.; Sharpe, L.T. The spectral sensitivities of the middle-and long-wavelength-sensitive cones derived from measurements in observers of known genotype. Vision research 2000, 40, 1711–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, H.R.; Sabir, M.F.; Bovik, A.C. A statistical evaluation of recent full reference image quality assessment algorithms. IEEE Transactions on image processing 2006, 15, 3440–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, T.O.; Mantiuk, R.; Myszkowski, K.; Seidel, H.P. Dynamic range independent image quality assessment. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 2008, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WATSON, A.; others. The cortex transform- Rapid computation of simulated neural images. Computer vision, graphics, and image processing 1987, 39, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottayil, N.K.; Valenzise, G.; Dufaux, F.; Cheng, I. Blind quality estimation by disentangling perceptual and noisy features in high dynamic range images. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2017, 27, 1512–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinson, M.H.; Wolf, S. An objective method for combining multiple subjective data sets. Visual Communications and Image Processing 2003. SPIE, 2003, Vol. 5150, pp. 583–592.

- Field, D.J. Relations between the statistics of natural images and the response properties of cortical cells. Josa a 1987, 4, 2379–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, S.; Zhang, Y.; Agrafiotis, D.; Bull, D. Blind high dynamic range image quality assessment using deep learning. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). IEEE, 2017, pp. 765–769.

- Prashnani, E.; Cai, H.; Mostofi, Y.; Sen, P. Pieapp: Perceptual image-error assessment through pairwise preference. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018, pp. 1808–1817.

- Azimi, M. ; others. PU21: A novel perceptually uniform encoding for adapting existing quality metrics for HDR. 2021 Picture Coding Symposium (PCS). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–5.

- Mantiuk, R.K.; Kim, M.; Ashraf, M.; Xu, Q.; Luo, M.R.; Martinovic, J.; Wuerger, S. Practical Color Contrast Sensitivity Functions for Luminance Levels up to 10000 cd/m 2. Color and Imaging Conference. Society for Imaging Science & Technology, 2020, Vol. 28, pp. 1–6.

- Borer, T.; Cotton, A. A display-independent high dynamic range television system. SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal 2016, 125, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q. Hdr-nerf: High dynamic range neural radiance fields. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 18398–18408.

- Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Dong, C. Hdrunet: Single image hdr reconstruction with denoising and dequantization. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021, pp. 354–363.

- Catley-Chandar, S.; Tanay, T.; Vandroux, L.; Leonardis, A.; Slabaugh, G.; Pérez-Pellitero, E. Flexhdr: Modeling alignment and exposure uncertainties for flexible hdr imaging. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2022, 31, 5923–5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S.S. On the psychophysical law. Psychological review 1957, 64, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.S.; Tsang, R.; Khademi Kalantari, N. Single Image HDR Reconstruction Using a CNN with Masked Features and Perceptual Loss. ACM Transactions on Graphics 2020, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Chan, T.N.; Li, H.; Hou, J.; Chau, L.P. Attention-guided progressive neural texture fusion for high dynamic range image restoration. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2022, 31, 2661–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanhart, P.; Bernardo, M.V.; Pereira, M.; G. Pinheiro, A.M.; Ebrahimi, T. Benchmarking of objective quality metrics for HDR image quality assessment. EURASIP Journal on Image and Video Processing 2015, 2015, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudil, P.; Novovičová, J.; Kittler, J. Floating search methods in feature selection. Pattern recognition letters 1994, 15, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.J.; Ohm, J.R.; Han, W.J.; Wiegand, T. Overview of the high efficiency video coding (HEVC) standard. IEEE Transactions on circuits and systems for video technology 2012, 22, 1649–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugito, Y.; Vazquez-Corral, J.; Canham, T.; Bertalmío, M. Image quality evaluation in professional HDR/WCG production questions the need for HDR metrics. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2022, 31, 5163–5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).