1. Introduction

The modern civilization contributes to the development of a long-term and nearly permanent social stress that can be an independent risk factor of many somatic conditions including cardiovascular diseases. The acute mental stress and depressive illness are perhaps the best established triggers of psychogenic cardiovascular conditions. The acute mental stress can cause a unique form of a transient cardiomyopathy known as Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy or “Broken Heart Syndrome” – a transient left ventricular dysfunction [

1]. In patients with coronary diseases, major depression is an independent risk factor of mortality [

2]. Furthermore, the cardiovascular consequences of anxiety disorders including panic disorder (PD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) are also well known. In patients with anxiety disorders, recurrent cardiac events are common and associated with not only worse health-related quality of life, but also the unfavourable course of the primary disease and the worsening prognosis that may lead to higher mortality [

3].

The activation of various neurogenic pathways is an important mediator of the acute and chronic stress-induced heart diseases [

3,

4]. The anxiety disorders, especially PD, have been shown to be directly linked to the development of the cardiac arrhythmias, both supraventricular and ventricular ones. The dysfunction of autonomic nervous system is predominantly implicated in the pathophysiology of the two afore-mentioned diseases. The increased sympathetic activation is the most common cause of the stress-induced cardiac arrhythmias. On the other hand, the anxiety disorders can be complicated by autonomic disorders with the elevated sympathetic control as a result of decreased vagal tone [

3,

4,

5].

The psychiatric disorders are associated with a whole array of impairments including dysregulation of the autonomic or involuntary functions such as heart rate, blood pressure and respiration. The HRV is one of the most promising markers of autonomic function. It is thought that HRV may serve as a surrogate measure of balance between the brain and the cardiovascular system [

6]. Many authors suggest that there is an autonomic dysfunction and reduced heart rate variability in patients with panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorders [

7,

8,

9].

The magnitude of HRV reduction correlates with the severity of the psychiatric disorders. Many studies have shown a reduced HRV in patients with major depression, GAD and PD due to the elevated sympathetic control and reduced vagal control. The reduced HRV was found in schizophrenic patients, but only in the long term electrocardiogram recordings. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease also present with the reduction of HRV, which is limited to the low frequency component [

6,

10,

11,

12].

The aim of the present study was to evaluate anxiety reactions with regard to the disturbances of homeostatic processes within the circulatory system as well as assess the HRV profile depending on the type of anxiety disorder. In order to obtain the optimal assessment of various symptoms reported by the patients manifesting anxiety disorders, the verification process using the objective methods such as 24-hour continuous ECG Holter Monitoring with evaluation of HRV was performed. The HRV analysis and its integration with the assessment and monitoring of psychiatric patients during therapy may help to elucidate the role of autonomic disturbances in mental disorders and optimize the treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

Fifty consecutive outpatients suffering from anxiety and personality disorders who participated in the intensive group psychotherapy at the day ward of the Lower Silesian Center for Mental Health in Wrocław (Poland) were enrolled into this study. The patients diagnosed with anxiety disorders and personality disorders were referred to the psychotherapy day ward by psychiatrists, mainly due to the inefficacy of pharmacological treatment and individual psychotherapy. The short-term psychodynamic group psychotherapy with two sessions every working day lasted for 12 weeks. All the patients with the provisional diagnosis of PD and GAD were enrolled consecutively in the middle of psychotherapeutic process (between weeks 5 and 8).

The final psychiatric diagnoses were made using the Present State Examination (PSE-10) with application of DSM-IV-TR criteria and then verified by a psychotherapeutic team at the end of treatment. The PSE-10 questionnaire is a part of the Schedules for Clinical Assessment (SCAN) aimed at assessing, measuring and classifying psychopathology and behavior associated with major psychiatric disorders in the adults [

13]. The Polish adaptation of SCAN was a collateral result of the international EDEN (European Day Hospital Evaluation) project and as such was successfully tested in the clinical setting [

14,

15,

16]. The PSE-10 served as a diagnostic tool for panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria regarding the time of 24-hour continuous ECG recordings.

Persons in the control group, with a negative history of anxiety disorders, came from the general population. They were selected on the occasion of research conducted in the Department of Pathophysiology of Wrocław Medical University and subjected to the same tests as patients with anxiety disorders.

None of the people included in any of the groups had a diagnosis of arterial hypertension or cardiovascular disease. Patients with a history of significant atrial or ventricular arrhythmia, other heart diseases, kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, sleep apnea syndrome, any neurological disease, psychotic disorders, addiction to psychoactive substances or cognitive impairment were excluded from the study. The significant differences between the examined groups in terms of sex and age (the group of 17 patients diagnosed with PD, the group of 21 patients with GAD and 40 subjects from the control group) were not found.

The heart rate variability (HRV) analysis based on 24-hour Holter ECG recordings is the non-invasive method for the assessment of cardiac sympathetic-parasympathetic balance. In the present study, the ambulatory Oxford Medilog MR-63 Holter ECG recorder was used. The HRV analysis was performed with use of the Oxford Medilog Suprima Holter System (a prospective edition of automatic analysis was applied). The HRV indices were calculated using time domain analysis (mRR, SDNN, pNN50 and rMSSD) and frequency domain analysis (LF, HF and LF/HF ratio). A decrease in HRV as observed in persons with anxiety disorders is a sign of heart autonomic dysregulation. The reduced HRV is a widely used marker of cardiac autonomic inflexibility, which is linked to panic disorder [

8].

The investigation was carried out in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and the written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects after the nature of the procedures had been fully explained. The local Bioethics Committee of Wroclaw Medical University approved this project.

The obtained values are presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and numbers (%) for categorical variables. In order to test the obtained data for normal distribution, Shapiro-Wilk test was used. The variables with non-normal distribution (pNN50, TP, VLF, LF, HF) were subjected to logarithmic transformation prior to the statistical analysis in order to obtain normal distribution. The Chi-square test was used for comparison of dichotomous variables. The statistical differences between more than two groups were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Tukey’s test was used for the post hoc analysis. The Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric tests together with post-hoc tests and Mann-Whitney U test were also applied.

The Statistica software version 13.3 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA) was used for the data analysis and the statistical significance was assumed at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Charakteristics of the Study Group

In the examined groups, 17 patients with panic disorder (PD) as a main diagnosis and 21 patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were enrolled. The personality disorders and somatoform disorders were the most common comorbidities in the patient groups.Two patients were diagnosed with co-occurring PD and GAD. They were included in the group with a diagnosis of PD, therefore the groups of patients differ as to the presence of panic disorder. None of the patients in the GAD group had panic attacks. Some of the patients in both groups took antidepressants. However, the differences in the frequency of use of medication groups, which were compared using chi-square test, were not statistically significant. The control group consisted of 40 healthy volunteers. Persons in the control group did not undergo pharmacological treatment. Characteristics of these groups were depicted in the

Table 1.

3.2. HRV Time and Frequency Parameters Obtained in PD, GAD and Control Group

3.2.1. HRV Time Domain Analysis during 24-Hour Holter ECG Monitoring

The analysis of the results included in the

Table 2 revealed the lowest values of time parameters in the PD group, which were significantly lower than the same parameters in the GAD and control group. The least statistically significant differences were noted between the GAD and control group, where a significant difference concerned only mRR (p=0.026).

3.2.2. HRV Frequency Domain Analysis during 24-Hour Holter ECG Monitoring

The comparison of frequency parameters in 24-hour ECG recordings (

Table 3) showed the most significant differences between the PD and control group, where the values of TP and its components were significantly lower in the former group. In turn, the significant differences between the GAD and control group were not found. The comparison between the PD and GAD group revealed significant differences in two components of the spectrum: LF (p=0.012) and HF (p=0.006). However, the LF/HF ratio was significantly higher in the PD group than in the GAD and control group (successively p=0.042 and p=0.036).

3.2.3. HRV Time Domain Analysis during 8 Hour Daytime and 4-Hour Nighttime Holter ECG Monitoring

The

Table 4 contains a comparison of HRV time parameters obtained from day and night recordings in each group. In the PD group, the least statistically significant differences were noted between day and night, which concerned only the SDNN (p=0.013) and SDANN (p=0.019) parameters. However, in the GAD group, similarly to the control group, almost all HRV time parameters (except SDNN-i) differed significantly when comparing both recordings.

3.2.4. HRV Frequency Domain Analysis during 8 Hour Daytime and 4-Hour Nighttime Holter ECG Monitoring

The

Table 5 presents a comparison of HRV frequency parameters obtained from day and night recordings in the study groups. In the PD group, significant differences between daytime and nighttime were noted in the HF component (p=0.023) and the LF/HF ratio (p=0.007). In turn, in the GAD group the statistically significant differences concerned only the LF/HF ratio (p=0.048). It should be noted that the LF/HF ratio was significantly higher in the nighttime recording only in the PD group. A similar comparison in the control group revealed significant differences in the TP value and its components except LF.

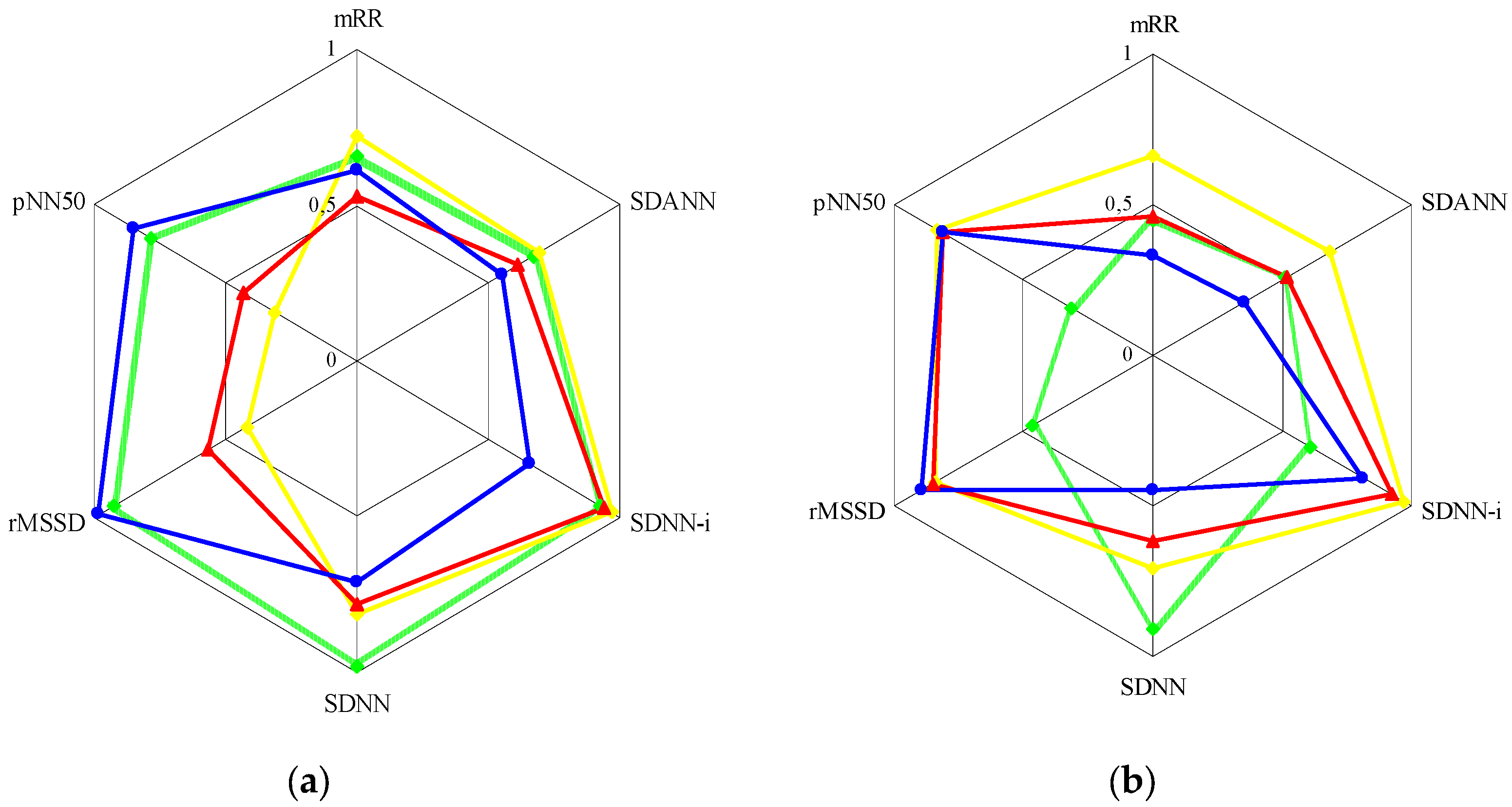

The

Figure 1 graphically presents the relationships between the parameters of HRV time and frequency analysis in the control group and the entire group with anxiety disorders (PD and GAD combined).

In the control group (a), the TP curve was distributed relatively evenly in the diagram, with a slight shift to the left, represented by the time parameters related to the parasympathetic system (rMSSD and pNN50). However, the strongest correlations were found between TP and SDNN (r=0.982; p<0.001). The HF curve was significantly shifted to the left side of the diagram, where it demonstrated the strongest correlations with rMSSD (r=0.949; p<0.001) and pNN50 (r=0.850; p<0.001). In turn, the LF curve was shifted to the right side of the diagram, which represented the time parameters related to the sympathetic nervous system. Here, the strongest correlations were found between LF and SDNN-i (r=0.919; p<0.001). The distribution of the VLF curve was similar. It was also noted that the mRR index showed similar correlation with the HF (r=0.609; p<0.001) and LF (r=0.536; p<0.001) components, with a slight predominance of the former.

The arrangement of the above curves was different in the group with anxiety disorders (b), and as before, the right side of the diagram was represented by the time parameters related to the sympathetic nervous system, and the left side – to the parasympathetic system. Here, the TP curve demonstrated significantly weaker correlations with the time parameters than in the control group (except SDNN: r=0.911; p<0.001), with a slight shift to the right side of the diagram. Attention was drawn to the distribution of the VLF and LF curves, which showed the strongest correlations with SDNN-i (successively r=0.966; p<0.001 and r=0.919; p<0.001), while the HF curve – with rMSSD (r=0.893; p<0.001) and pNN50. Contrary to the control group, the mRR parameter showed stronger correlations with the LF component (r=0.457; p=0.003) than the HF component (r=0.332; p=0.023).

4. Discussion

The autonomic nervous system (ANS), composed of two primary branches (sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system), plays an essential role in the regulation of the circulatory system. The sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves work together to balance the functions of the autonomic effector organs [

17].

The heart rate variability (HRV) is the physiological phenomenon of variation of the heart beats. The HRV examination is a non-invasive and easy-to-use tool for the assessment of sympathetic – parasympathetic balance within the circulatory system, albeit the interpretation of HRV components and, in particular, its spectral analysis is a subject of discussion [

18].

According to the current international protocol for HRV method, two critical frequency domain parameters obtained from spectral analysis are widely used: LF (low frequency power; 0.04–0.15 Hz) that represents both sympathetic and vagal influence; HF (high frequency power; 0.15–0.40 Hz) reflecting the modulation of vagal tone. In addition, LF/HF ratio indicates the balance between sympathetic and vagal tone [

19,

20]. In the time domain, RR intervals, SDNN, rMSSD and pNN50 were analysed. The rMSSD and pNN50 are associated with HF power and consequently the parasympathetic activity, whereas SDNN and especially SDNN-i are correlated with VLF and LF power. VLF (very low frequency; 0.003–0.04 Hz) partially reflects thermoregulatory mechanisms, fluctuation in the activity of the renin–angiotensin system and the function of peripheral chemoreceptors. TP, or total spectral power, is considered equivalent to the SDNN, which represents the combined tension of both parts of the autonomic nervous system [

21]. It seems obvious regarding the facts known from the literature on the numerous relationships between time and frequency analysis parameters, which can be largely treated in the alternative ways. This is also confirmed by the results of our research (

Figure 1).

The increased sympathetic activation is the most common cause of cardiac rhythm disturbances and can induce both the atrial and ventricular arrhythmias. It can also mitigate the protective antiarrhythmic drug effects [

22]. The heart rate variability (HRV) analysis based on 24-hour continuous Holter ECG recordings is the non-invasive method for the assessment of cardiac sympathetic-parasympathetic balance [

23]. In the present study, even a preliminary HRV analysis carried out in the PD (panic disorder) and GAD (generalized anxiety disorder) group showed the decreased value of mRR parameter which affected directly a decrement of the remaining HRV time parameters as well as heart rate values. The results of the time analysis of the 24-hour Holter ECG recordings (

Table 2) demonstrated statistically significant differences between the PD and the GAD group in terms of all tested parameters (the examined parameters were significantly lower in the patients with panic disorder as compared with generalized anxiety disorder group). The results of the frequency analysis of the 24-hour Holter ECG recording (

Table 3) also showed statistically significant differences between the examined groups in the range of the LF, HF values and LF/HF ratio. The LF and HF values in the PD group were significantly lower than in the GAD group. In turn, the LF/HF ratio was higher in the PD group as reported by other authors [

23,

24]. In contrast, Zhang et al. [

25] did not find significant association between LF and PD in the LF analysis.

It was noticeable that all parameters of both time (

Table 2) and frequency (

Table 3) HRV analysis were significantly lower in persons manifesting the symptoms of panic disorder (PD group) as compared with the control group. A decrease in SDNN value below 100 ms as observed only in these persons is a relevant predictor of serious cardiac events. However, none of the patients presented with a decrease in SDNN value below 50 ms (high risk of cardiac death) [

26]. In addition, the decreased SDNN value indicated a predominance of the sympathetic activity as a result of the reduced parasympathetic tone advocated by the decreased HRV parameters of the vagus nerve activity (rMSSD, pNN

50, HF) [

27]. In turn, no statistically significant differences were found between the GAD and control group as to the time (except mRR) and frequency parameters on the 24-hour Holter ECG recordings (

Table 2 and 3).

According to Paniccia et al. [

28], neurophysiological research on anxiety can be the first step to understanding how physiological flexibility (i.e., HRV) is related to psychological flexibility (i.e., adaptive or maladaptive responses to life events).

The innovative aspect of the present analysis was to find a distinct profile of the heart rate variability with regard to the types of anxiety disorder. The characteristic HRV profile was especially clear while comparing the ECG night and daytime recordings (

Table 4 and 5). Once again, the most unfavourable HRV alterations were observed in the persons with panic disorder. These abnormalities comprised a disappearance of day vs. night amplitude of the majority of HRV parameters with a simultaneous significant decrease in their values. In comparison with the control group, the largest decrease was noted in the ‘night’ parameters of the PD group reflecting the vagus nerve activity. These observations were indicative of serious dysfunction of the parasympathetic system resulting in a lack of diurnal rhythm of the sympathetic-parasympathetic regulation. Such considerable abnormalities were not found in the patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). As to the GAD group, the comparative analysis of the HRV parameters of the day and night recordings showed a decrease in the day vs. night amplitude resulting from attenuation of the parameters related with the sympathetic activity (SDNN, SDANN). However, it was noted only on the night recordings, with a simultaneous increase in the parameters related with the parasympathetic activity (rMSSD, pNN

50, HF). Such changes were not observed in the persons presenting with symptoms of panic disorder. On the contrary to the GAD and control group, instead of increase, a significant decrease in the HRV parameters related to the vagus nerve activity was found at nighttime.

It should be noted that all groups showed significant differences in the LF/HF ratio (

Table 5) between day and night hours, but only in the PD group this difference was unfavorable due to a significantly higher value at night. This indicated the disturbed circadian rhythms within the cardiac sympathetic-parasympathetic regulation resulting from a decrease in nocturnal vagotonia which may subsequently lead to the weakening of antiarrhythmic effect of the vagus nerve. For this reason, the group of patients with panic anxiety were particularly prone to the occurrence of arrhythmic events, including serious ventricular arrhythmias.

5. Conclusions

The circadian rhythms of HRV as assessed with the Holter ECG monitoring are considerably flattened in patients with anxiety disorders. In the PD group, the largest decrease was noted in the ‘night’ parameters reflecting the vagus nerve activity, which resulted in a lack of diurnal rhythm of the sympathetic-parasympathetic regulation. Such considerable abnormalities were not found in the persons with GAD, where a small increase in nocturnal vagotonia was observed. The increase was smaller than in the control group, albeit it was significantly bigger as compared with the PD group. In addition , the significant differences in the day vs night LF/HF ratio were found in all groups, but only in the PD group the difference was unfavourably big. The assessment of the impact of anxiety disorders on the circadian HRV requires differentiating between PD and GAD because of the considerable differences related to the nature of the particular disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J. and M.S.; methodology, A.J., R.S., D.K., A.M. and M.S.; validation, A.J. and M.S.; formal analysis, A.J., R.S., D.K., A.M. and M.S.; investigation, A.J., R.S. and A.M.; resources, A.J.; data curation, A.J., R.S., D.K., A.M. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J. and M.S; writing—review and editing, R.S. and D.K.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Bioethics Committee at Wroclaw Medical University (KB 58/2011 dated on 10 March 2011).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dawson, D.K. Acute stress-induced (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy. Heart 2018, 104, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Headrick, J.P.; Peart, J.N.; Budiono, B.P.; Shum, D.H.K.; Neumann, D.L.; Stapelberg, N.J.C. The heartbreak of depression: ‘Psycho-cardiac’ coupling in myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017, 106, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hering, D.; Lachowska, K.; Schlaich, M. Role of the sympathetic nervous system in stress-mediated cardiovascular disease. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2015, 17, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esler, M. Mental stress and human cardiovascular disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017, 74, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.C.; Su, M.I.; Liu, C.W.; Huang, Y.C.; Huang, W.L. Heart rate variability in patients with anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022, 76, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramesh, A.; Nayak, T.; Beestrum, M.; Quer, G.; Pandit, J.A. Heart rate variability in psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2023, 19, 2217–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, B.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zou, Z. Heart rate variability changes in patients with panic disorder. J Affect Disord. 2020, 267, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zou, Y.; Xiao, J.; Min, W.; Yuan, C.; Ye, Y.; Li, M.; et al. Heart rate variability in generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder and panic disorder: A network meta-analysis and systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2023, 330, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrowski, K.; Wichmann, S.; Siepmann, T.; Wintermann, G.B.; Bornstein, S.R.; Siepmann, M. Effects of mental stress induction on heart rate variability in patients with panic disorder. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2017, 42, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Shinba, T.; Sun, G. The development of a novel high-precision major depressive disorder screening system using transient autonomic responses induced by dual mental tasks. J Med Eng Technol. 2018, 42, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, S.A.; Kara, S.; Latifoğlu, F.; Bilgiç, V. Analysis of heart rate variability during auditory stimulation periods in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Monit Comput. 2015, 29, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, V.P.; Ramalho Oliveira, B.R.; Tavares Mello, R.G.; Moraes, H.; Deslandes, A.C.; Laks, J. Heart rate variability indexes in dementia: a systematic review with a quantitative analysis. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2018, 15, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schützwohl, M.; Kallert, T.; Jurjanz, L. Using the schedules for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry (SCAN 2. 1) as a diagnostic interview providing dimensional measures: cross-national findings on the psychometric properties of psychopathology scales, Eur. Psychiatry 2007, 22, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Małyszczak, K.; Rymaszewska, J.; Hadryś, T.; Adamowski, T.; Kiejna, A. Porównanie diagnozy SCAN z diagnoza kliniczna [Comparison between a SCAN diagnosis and a clinical diagnosis]. Psychiatr Pol. 2002, 36, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adamowski, T.; Kiejna, A.; Hadryś, T. Badanie zgodności rozpoznań psychiatrycznych z kryteriami diagnostycznymi klasyfikacji ICD-10 za pomoca kwestionariusza SCAN [Study of compatibility of psychiatric diagnoses with ICD-10 diagnostic criteria using the SCAN questionnaire]. Psychiatr Pol. 2006, 40, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kallert, T.W.; Glöckner, M.; Priebe, S.; Briscoe, J.; Rymaszewska, J.; Adamowski, T.; Nawka, P.; Reguliova, H.; Raboch, J.; Howardova, A.; et al. A comparison of psychiatric day hospitals in five European countries: implications of their diversity for day hospital research. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004, 39, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Zhu, L. The crosstalk between autonomic nervous system and blood vessels. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2018, 10, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Rüdiger, H.; Ziemssen, T. Spectral analysis of heart rate variability: time window matters. Front Neurol. 2019, 10, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziemssen, T.; Siepmann, T. The investigation of the cardiovascular and sudomotor autonomic nervous system – a review. Front Neurol. 2019, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophisiology: Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Circulation 1996, 93, 1043–1065. [CrossRef]

- Benichou, T.; Pereira, B.; Mermillod, M.; Tauveron, I.; Pfabigan, D.; Maqdasy, S.; Dutheil, F. Heart rate variability in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta–analysis. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0195166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manolis, A.A.; Manolis, T.A.; Apostolopoulos, E.J.; Apostolaki, N.E.; Melita, H.; Manolis, A.S. The role of the autonomic nervous system in cardiac arrhythmias: The neuro-cardiac axis, more foe than friend? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2021, 31, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durdu, G.Ş.; Kayikcioğlu, M.; Pirildar, Ş.; Köse, T. Evaluation of heart rate variability in drug free panic disorder patients. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2018, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumm, J.L.M.; Pyrkosch, L.; Plag, J.; Nagel, P.; Petzold, M.B.; Bischoff, S.; Fehm, L.; Fydrich, T.; Ströhle, A. Heart rate variability in patients with agoraphobia with or without panic disorder remains stable during CBT but increases following in-vivo exposure. J Anxiety Disord. 2019, 64, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, B.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zou, Z. Heart rate variability changes in patients with panic disorder. J Affect Disord. 2020, 267, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosnowski, M.; Skrzypek-Wańha, J.; Tendera, M. Wiek badanego a wykrycie patologicznej zmienności rytmu zatokowego. Folia Cardiol. 2002, 9, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, C.; Wilhelm, M.; Salzmann, S.; Rief, W.; Euteneuer, F. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability in major depression. Psychol Med. 2019, 49, 1948–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniccia, M.; Paniccia, D.; Thomas, S.; Taha, T.; Reed, N. Clinical and non-clinical depression and anxiety in young people: A scoping review on heart rate variability. Auton Neurosci. 2017, 208, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).