Submitted:

12 August 2024

Posted:

12 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background

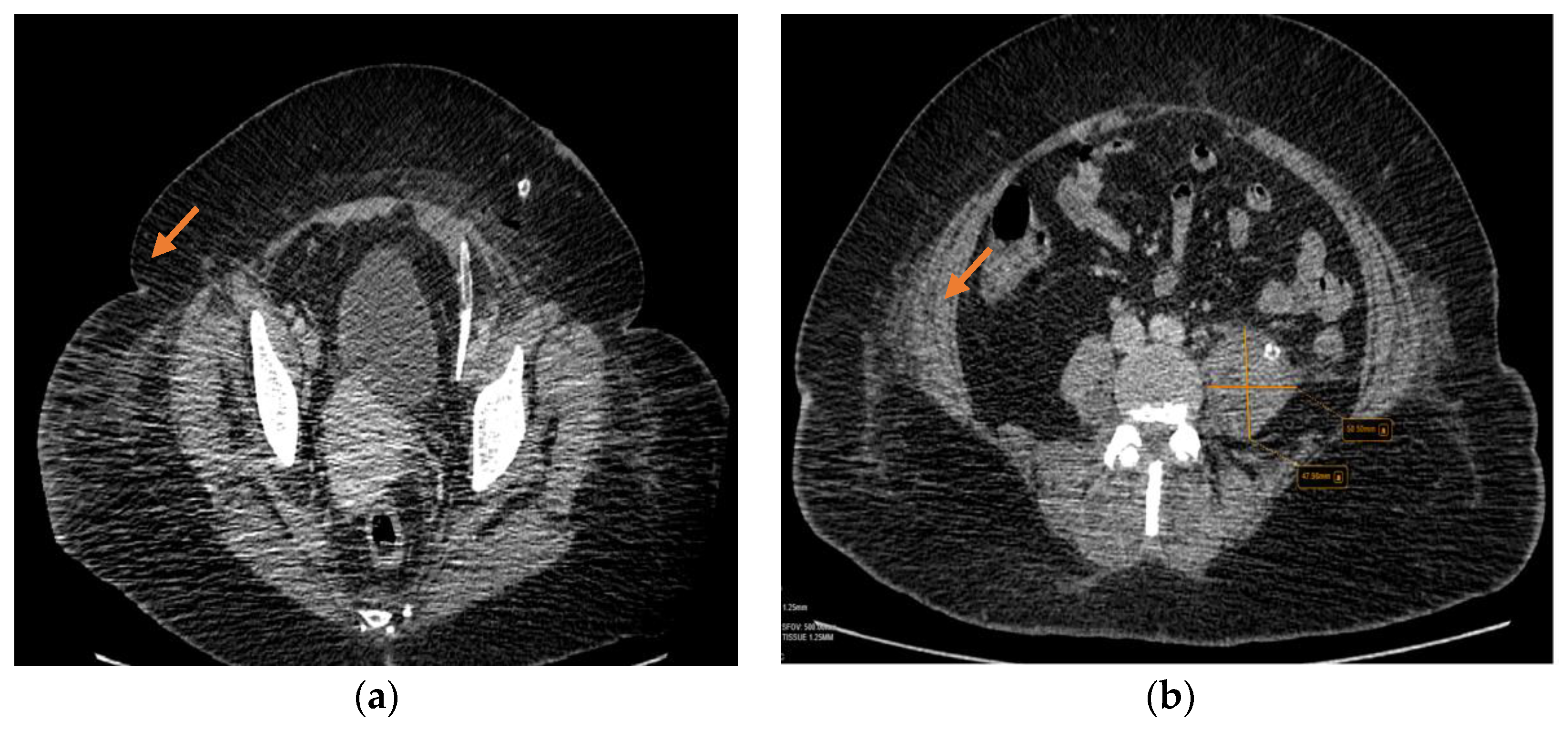

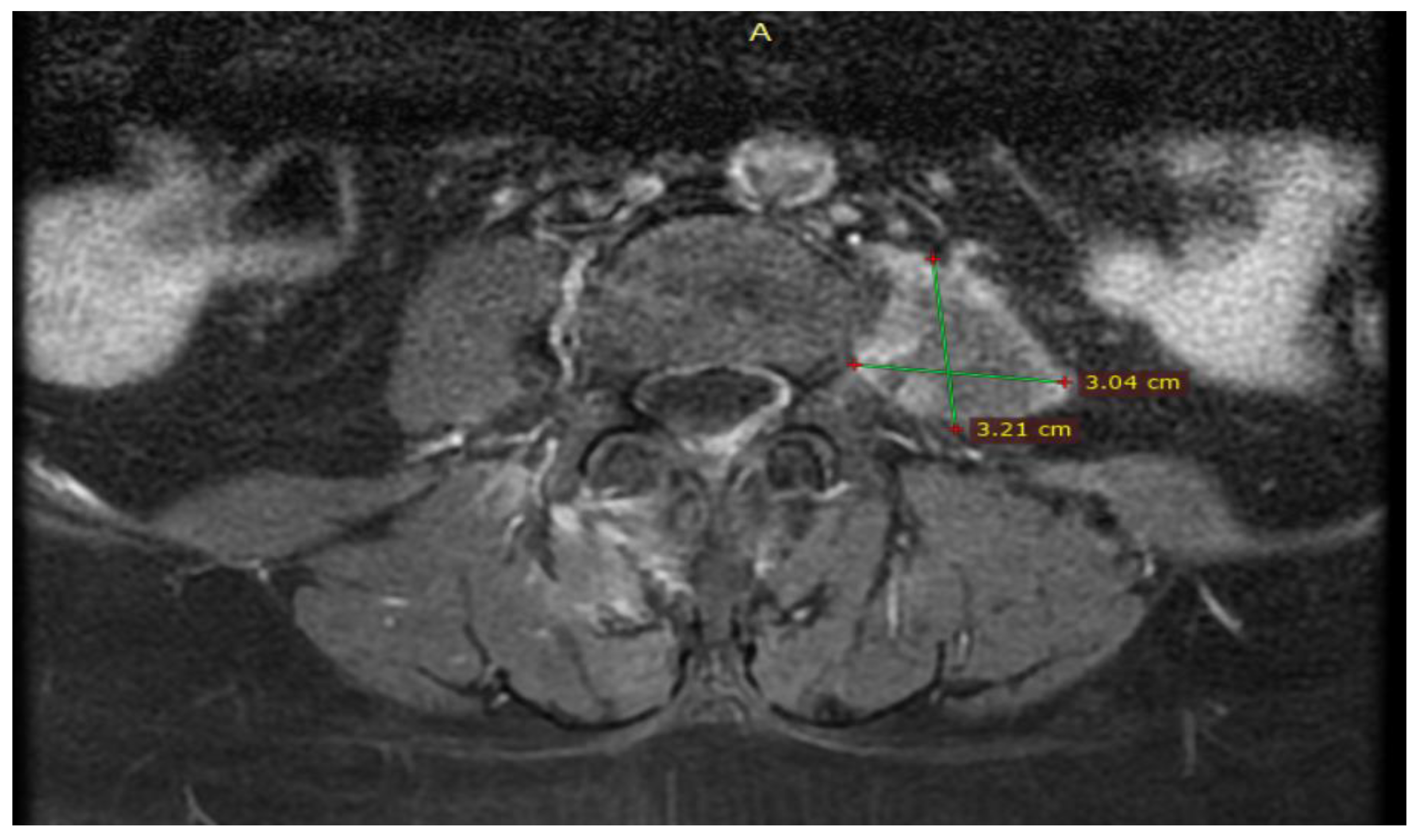

Case Report

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Mynter, H. , Acute Psoitis. Buffalo Med Surg J 1881, 21(5), 202–210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garner, J.; Meiring, P.; Ravi, K.; Gupta, R. , Psoas abscess–not as rare as we think? Colorectal Disease 2007, 9(3), 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, D.; Robinson, P.; Crowley, T. P. , Iliopsoas abscess – A review and update on the literature. International Journal of Surgery 2012, 10(9), 466–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chern, C.-H.; Hu, S.-C.; Kao, W.-F.; Tsai, J.; Yen, D.; Lee, C.-H. , Psoas abscess: Making an early diagnosis in the ED. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 1997, 15(1), 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moslemi, S.; Tahamtan, M.; Hosseini, S. V. , A Late-onset Psoas Abscess Formation Associated with Previous Appendectomy: A Case Report. Bull Emerg Trauma 2014, 2(1), 55–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Debes, J. D.; Lopez-Morra, H.; Dickstein, G. , A psoas abscess caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa due to diverticular perforation. Am J Gastroenterol 2006, 101(9), 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J. Y.; Lee, J. K.; Cha, S. M.; Joo, Y. B. , Psoas abscess caused by spontaneous rupture of colon cancer. Clin Orthop Surg 2011, 3(4), 342–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudinger, R.; Sharma, R.; Patel, S., Psoas Abscess: A Rare Initial Manifestation of Crohn's Disease: 682. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology | ACG 2015, 110, S301.

- Dowling Montalva, Á.; de Araujo Santana Junior, R. N.; Molina, M. , Full Endoscopic Treatment for a Fibrosis Complication after Psoas Abscess. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2023, 13(7), 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, D.; Neal, B.; Jacobs, A. , Iliopsoas Abscess Due to Nephrolithiasis and Pyelonephritis. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med 2018, 2(3), 264–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldamanhori, R.; Barakat, A.; Al-Madi, M.; Kamal, B. , Psoas Abscess Secondary to Urinary Tract Fungal Infection. Urol Case Rep 2015, 3(4), 106–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, M.-X.; Li, J.; Lyu, G.-H., Iliopsoas Abscess Due to Brenner Tumor Malignancy: A Case Report. Chinese Medical Journal 2015, 128 (3).

- Scherer, J.; Kotze, T.; Mdiza, Z.; Lawson, A.; Held, M.; Thienemann, F. , Tuberculous Spondylodiscitis with Psoas Abscess Descending into the Anterior Femoral Compartment Identified Using 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoroglucose Positron Emission Tomography Computed Tomography. Diagnostics 2024, 14(10), 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghantarchyan, H.; Philip, S.; Dunn, K.; Suh, J. S. , A Rare Case of Vertebral Osteomyelitis and Bilateral Psoas Abscess From an Unknown Source. J Med Cases 2020, 11(11), 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albouk, A. M.; Alhumaidi, I. M.; Alamri, A. J.; Alsaygh, E. F.; Alshahir, A. A.; Almuhammadi, H. H.; Jamal, R. S. , Primary Psoas Abscess Complicated by Septic Arthritis Due to Community-Acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Cureus 2022, 14(6), e26095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedes Saint Clair, J. P.; Cordeiro Rabelo Í, E.; Rios Rodriguez, J. E.; Lopes de Castro, G.; Moreira Printes, T. R.; Cabral Fraiji Sposina, L. B.; Alcântara Barbosa, D.; Macedo de Souza, G. , Pott's disease associated with psoas abscess: Case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022, 74, 103239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussa, O.; Sreedharan, L.; Poels, J.; Ojimba, T. , Psoas abscess complicating endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Surg Case Rep 2012, 2012(10), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routier, E.; Bularca, S.; Sbidian, E.; Roujeau, J. C.; Bagot, M. , [Two cases of psoas abscesses caused by group A beta-haemolytic streptococcal infection with a cutaneous portal of entry]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2010, 137(5), 369–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsadery, H. A.; Alzaher, M. Z.; Osman, A. G. E.; Nabri, M.; Bukhamseen, A. H.; Alblowi, A.; Aldossery, I. , Iliopsoas Hematoma and Abscess Formation as a Complication of an Anterior Abdominal Penetrating Injury: a Case Report and Review of Literature. Med Arch 2022, 76(4), 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sah, J. K.; Adhikari, S.; Sah, G.; Ghimire, B.; Singh, Y. P. , Presentation, management and outcomes of iliopsoas abscess at a University Teaching Hospital in Nepal. Innovative Surgical Sciences 2023, 8(1), 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Li, J.-J.; Hsiao, C.-H.; Yen, C.-C. , Clinical Characteristics and In-Hospital Outcomes in Patients with Iliopsoas Abscess: A Multicenter Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12(8), 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, S.; Ren, W.; Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Zheng, W.; Yin, Q.; Pan, H. , Psoas abscess: an uncommon disorder. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2024, 100(1185), 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).