Submitted:

10 August 2024

Posted:

12 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Diphtheria and the DPT Vaccine

- Diphtheria:

- Te0tanus:

- Pertussis (Whooping Cough):

Factors Influencing Vaccine Effectiveness

Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy and Strengthening Immunization Programs

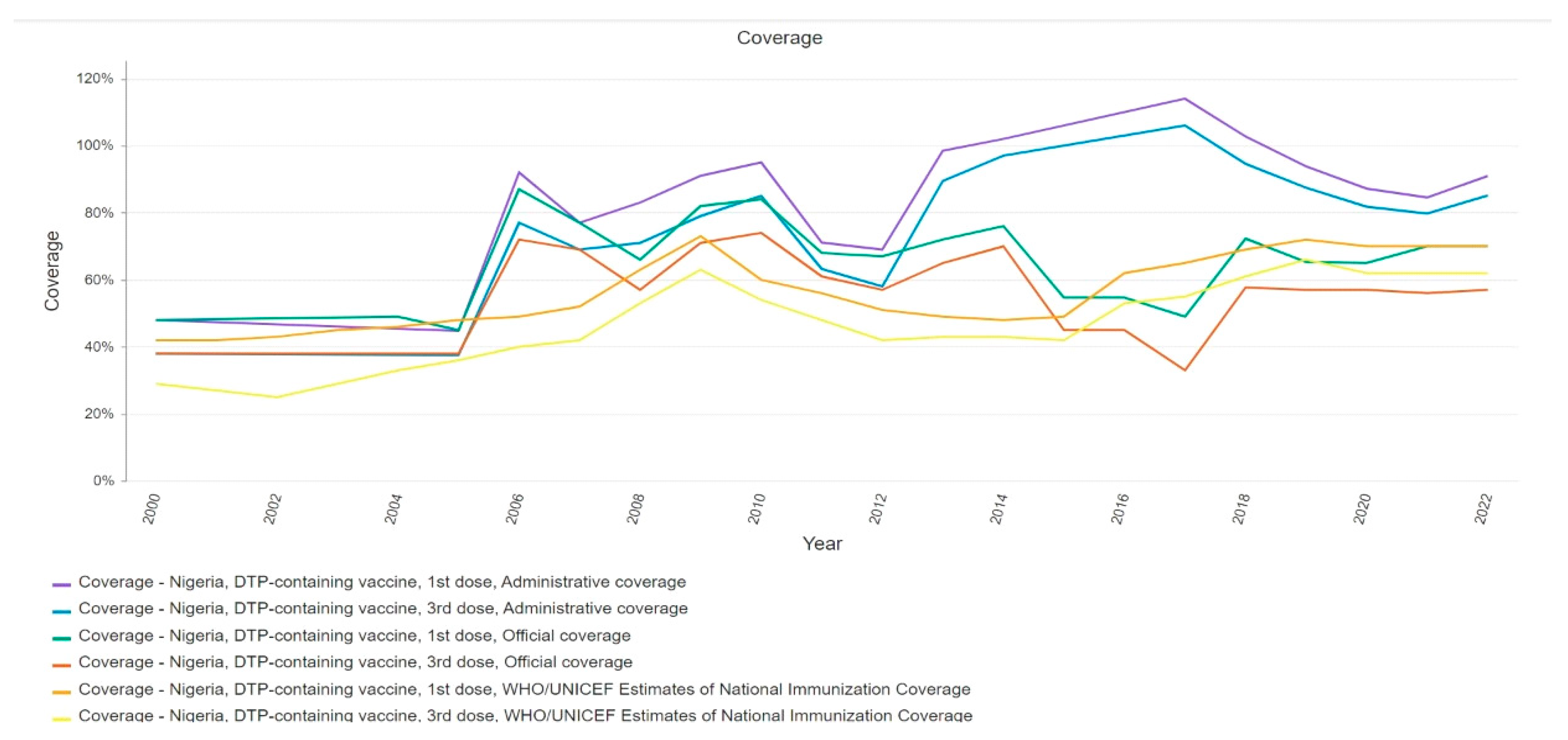

Health System Challenges in West Africa

WHO Strategies and Initiatives in the Control and Prevention of Diphtheria

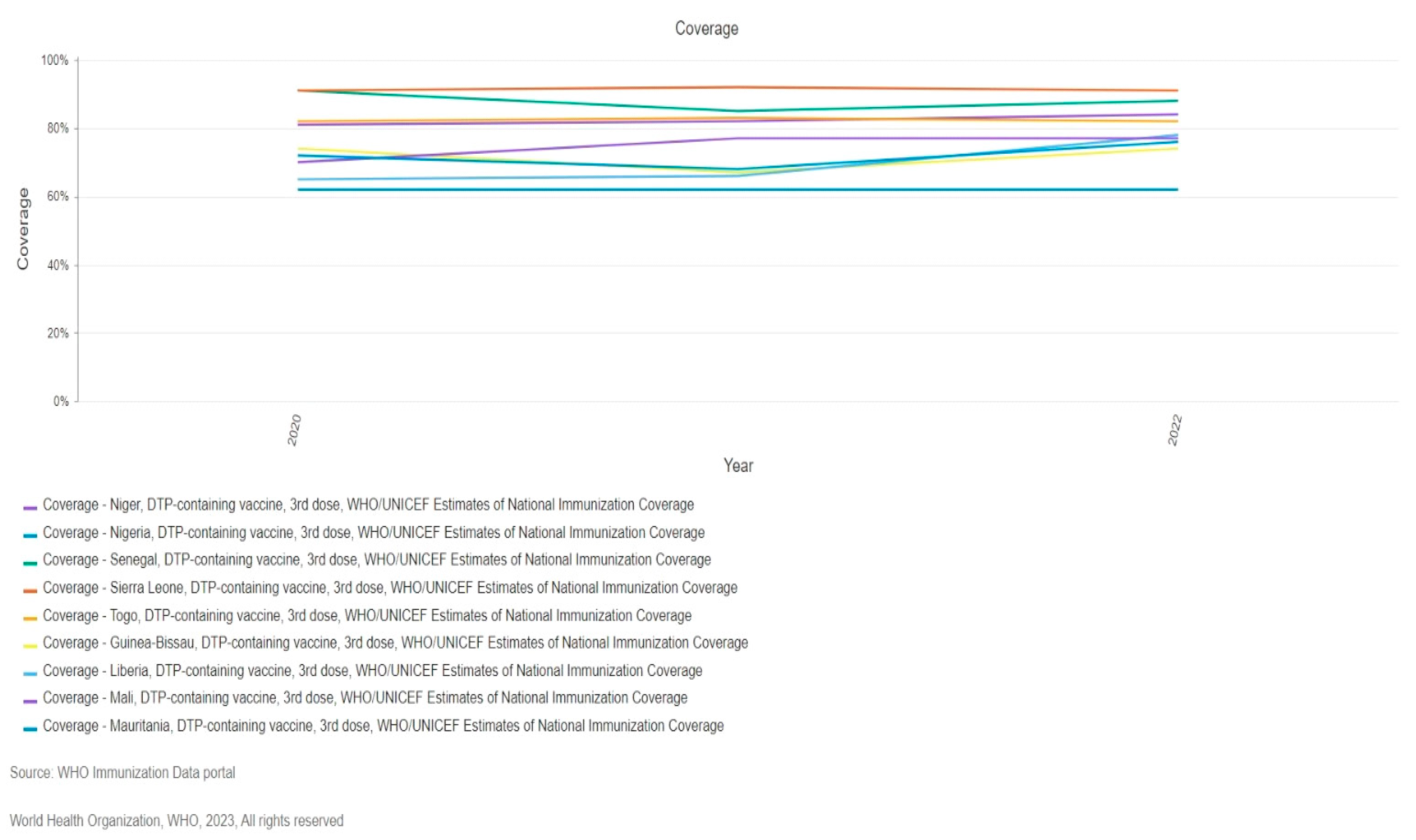

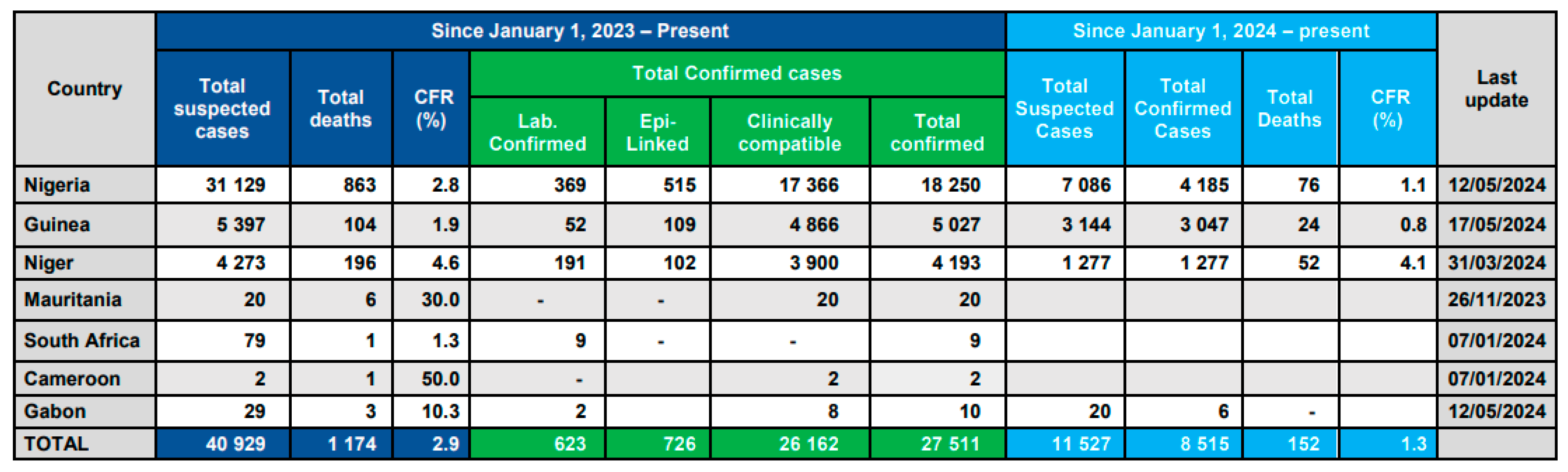

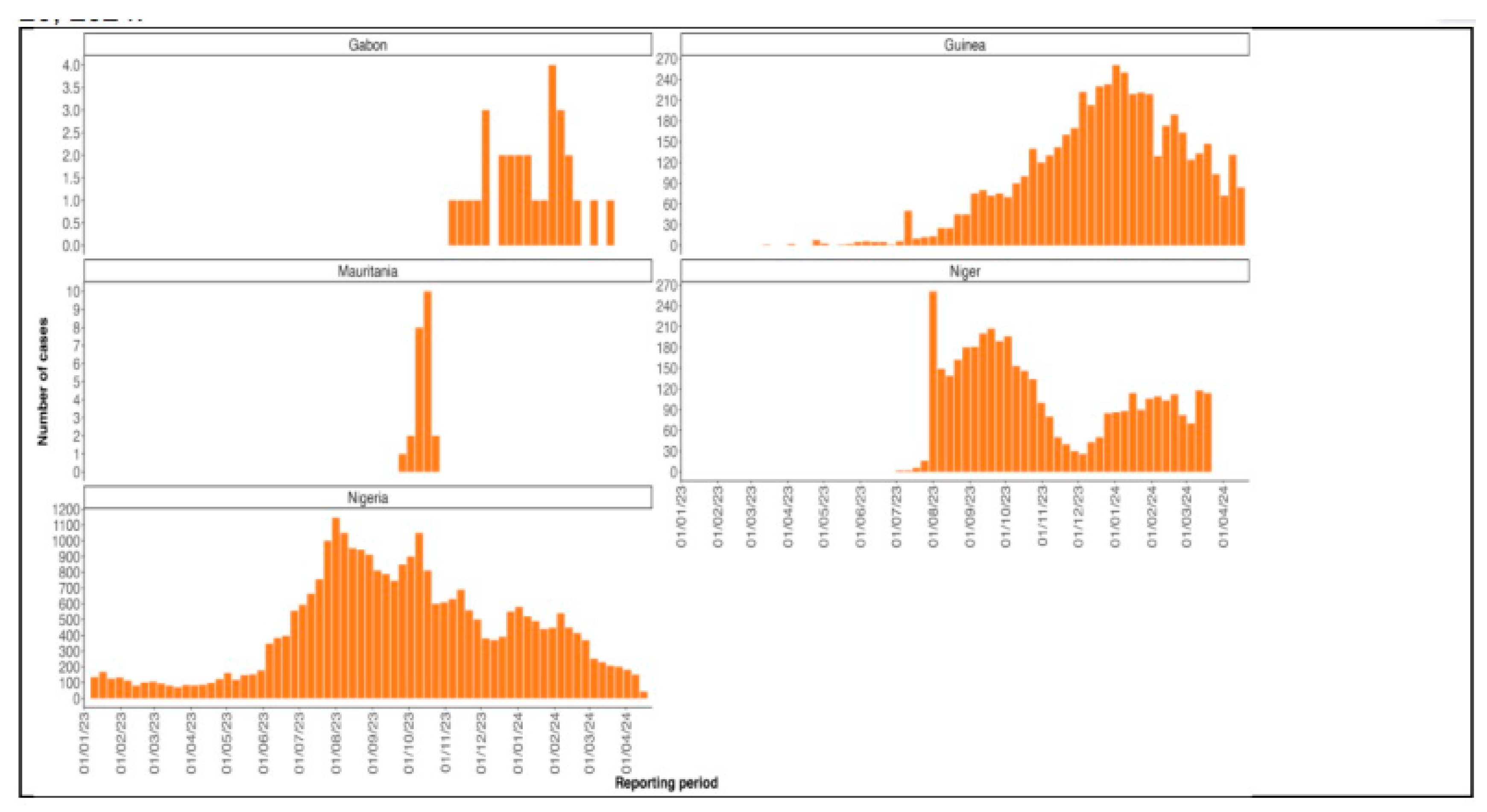

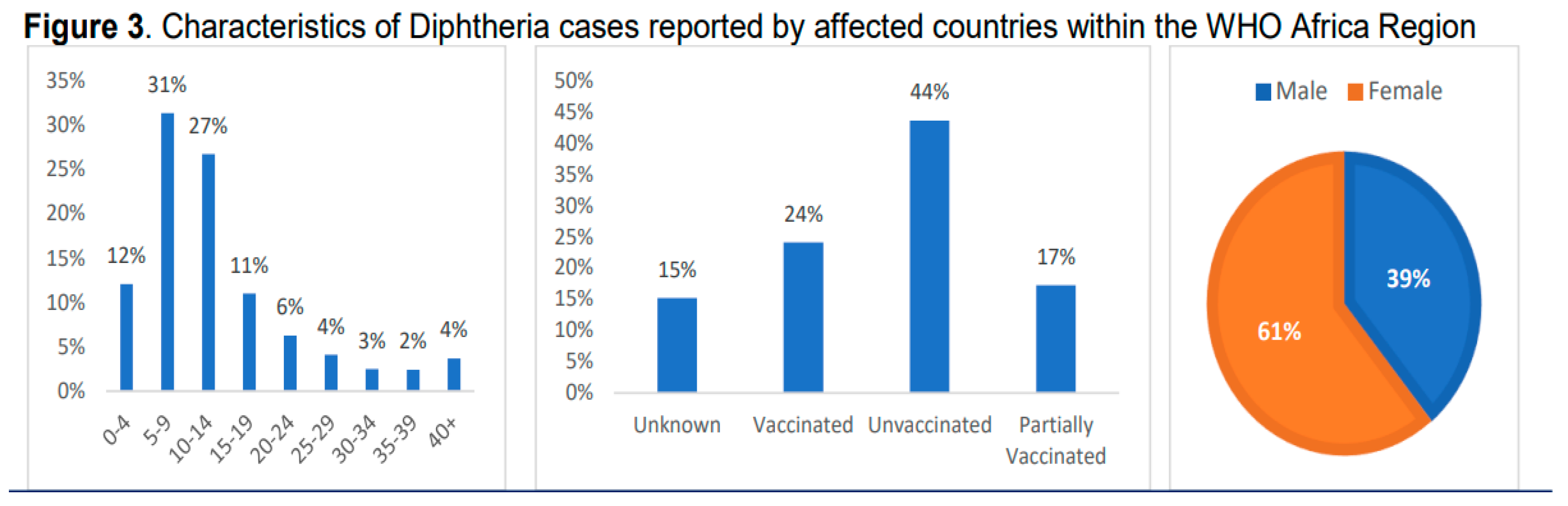

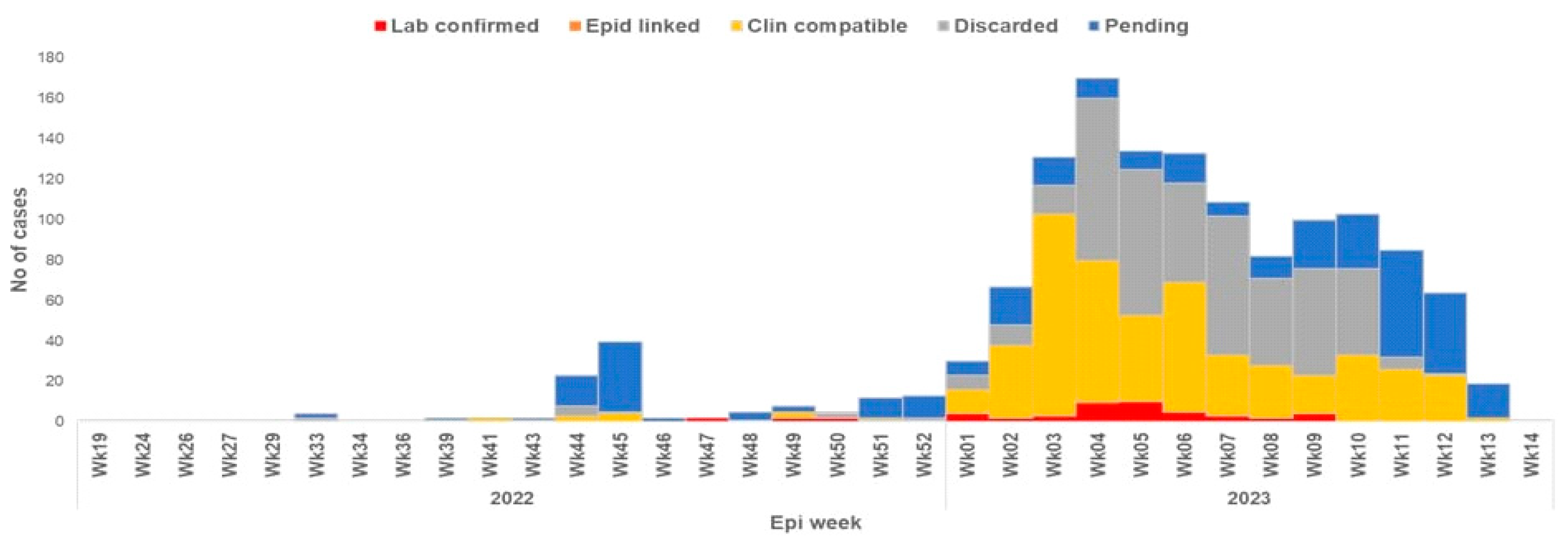

Recent Diphtheria Outbreak in West Africa

Factors Contributing to the Outbreak.

Government and Healthcare Response to the Outbreak.

Global Efforts in Diphtheria Control and Prevention: International Collaborations and Support for West African Countries

| Country | Challenges |

| Nigeria | - Delays in reporting cases - Limited supplies of medical equipment and testing reagents - Security issues hindering response efforts in some regions - Limited capacity for diphtheria testing at sub-national laboratories |

| Niger | - Insufficient funding for vaccination campaigns and logistics - Security concerns restricting access to affected areas - Inadequate training of healthcare workers in diphtheria management - Challenges in monitoring diphtheria antitoxin usage |

| Gabon & Cameroon | - Lack of in-country infrastructure and resources for diphtheria testing, requiring samples to be shipped to South Africa for confirmation (delays diagnosis and response) |

| Guinea | - Incomplete vaccination coverage leaving the population vulnerable - Inadequate capacity in treatment centers to isolate and treat all patients - Ongoing challenges following MSF withdrawal (expertise and resources) - Funding delays hindering response efforts - Unmet performance indicators (delayed case isolation and investigation) |

Funding

Abbreviations

| DPT: Diphtheria Pertussis Tetanus |

| NCDC: Nigerian Centre for Disease Control |

| WHO: World Health Organization |

| CDC: Center for Disease Control and Prevention |

| EPI: Expanded Program on Immunization |

| GDSN: Global Diphtheria Surveillance Network |

| ACIP: Advisory Commission on Immunization Practices |

References

- Wichmann, O., & Ultsch, B. (2013). Effektivität, Populationseffekte und Gesundheitsökonomie der Impfungen gegen Masern und Röteln. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz, 56, 1260–1269. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2018). Diphtheria vaccine: WHO position paper, August 2017 – Recommendations. Vaccine, 36, 199–201. [CrossRef]

- Desai S, Scobie HM, Cherian T, Goodman T. Use of tetanus-diphtheria (Td) vaccine in children 4–7 years of age: World Health Organization consultation of experts. Vaccine. 2020 May;38:3800–7. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J. L., Tiwari, T., Moro, P., Messonnier, N. E., Reingold, A., Sawyer, M., & Clark, T. A. (2018). Prevention of pertussis, tetanus, and diphtheria with vaccines in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recommendations and Reports, 67, 1. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (1991). Pertussis vaccination: Use of acellular pertussis vaccines for all childhood immunization programs. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 40(RR-1), 1 (Editorial).

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (1991). Immunization practices committee. Pertussis immunization: Use of acellular pertussis vaccines for all childhood immunization programs. Pediatrics, 88(5), 1090-1096.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2005). Tdap vaccine for adolescents and adults. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 54(RR-7), 1-8.

- Tafreshi, S. Y. H. (2020). Efficacy, safety, and formulation issues of the combined vaccines. Expert Review of Vaccines, 19(10), 949-958. [CrossRef]

- Kretsinger, K., Broder, K. R., Cortese, M. M., Joyce, M. P., Ortega-Sanchez, I., Lee, G. M., Tiwari, T., Cohn, A. C., Slade, B. A., Iskander, J. K., Mijalski, C. M., Brown, K. H., Murphy, T. V., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, & Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2006). Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adults: Use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and recommendation of ACIP, supported by the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), for use of Tdap among health-care personnel. MMWR. Recommendations and Reports: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Recommendations and Reports, 55(RR-17), 1–37.

- Gattás, V. L., Luna, E. J. A., Sato, A. P. S., Fernandes, E. G., Vaz-de-Lima, L. R., Sato, H. K., & Castilho, E. A. D. (2020). Adverse event occurrence following use of tetanus, diphtheria and acellular pertussis adsorbed vaccine–Tdap–, São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 2015-2016. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 29, e2019280.

- Van Der Zee, A., Schellekens, J. F. P., & Mooi, F. R. (2015). Laboratory Diagnosis of Pertussis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 28(4), 1005–1026. [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, S. A., Offit, P. A., DeStefano, F., Larson, H. J., Arora, N. K., Zuber, P. L., ... & Glanz, J. (2020). The science of vaccine safety: summary of meeting at Wellcome Trust. Vaccine, 38(8), 1869-1880. [CrossRef]

- Nwinyi, O. C., & Ajani, O. O. (2010). Identification, and Clinical Relevance of Gram–Positive Spore Formers.

- Doley, R. M., Mahanta, B. N., & Kakati, S. (2016). Diphtheria–An Overview. Assam Journal of Internal Medicine, 6(1), 19.

- Martin, C. J., Donahue, A. S., & Meyer, J. D. (2016). Bacteria. Physical and Biological Hazards of the Workplace, 347-410.

- Greenwood, B. (2014). The contribution of vaccination to global health: past, present and future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1645), 20130433.

- Kour, I., Singhal, L., & Gupta, V. (2023). Diphtheria: A Paradigmatic Vaccine-Preventable Toxigenic Disease with Changing Epidemiology. In Recent Advances in Pharmaceutical Innovation and Research (pp. 749-759). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Amara, A. A. (2016). Vaccines against Pathogens: A Review and Food For Thought. SOJ Biochem 2 (2), 20. Vaccines against Pathogens: A Review and Food For Thought. [CrossRef]

- Kolybo, D. V., Labyntsev, A. A., Korotkevich, N. V., Komisarenko, S. V., Romaniuk, S. I., & Oliinyk, O. M. (2013). Immunobiology of diphtheria. Recent approaches for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease. Biotechnologia Acta, 6(4), 043-062.

- World Health Organisation. Diphtheria reported cases and incidence (Internet). WHO. 2023.

- Jain A, Samdani S, Meena V, Sharma MP. Diphtheria: It is still prevalent!!! International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2016 Jul;86:68–71.

- CDC. Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Pertussis Vaccine Recommendations (Internet). CDC. 2023. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/dtap-tdap-td/hcp/recommendations.html.

- Grasse M, Meryk A, Schirmer M, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Weinberger B. Booster vaccination against tetanus and diphtheria: insufficient protection against diphtheria in young and elderly adults. Immunity & ageing : I & A. 2016 Sep 5;13(1):26. [CrossRef]

- Desai S, Scobie HM, Cherian T, Goodman T. Use of tetanus-diphtheria (Td) vaccine in children 4–7 years of age: World Health Organization consultation of experts. Vaccine. 2020 May;38(21):3800–7. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, S. (2024, January 12). Why diphtheria is making a comeback. WUSF https://news.wgcu.org/2024-01-23/why-diphtheria-is-making-a-comeback.

- World Health Organization. (2024, February 25). WHO African Region Health Emergency Situation Report: Multi-country Outbreak of Diphtheria - Consolidated Regional Situation Report 006.

- ReliefWeb. (2024, January 11). Guinea: Diphtheria Outbreak Spreads to 33 Prefectures. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON492.

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (NCDC). (2023). Diphtheria Situation Report Serial Number 01 Data as of Epi-week 03 2023.

- Niger Ministry of Public Health. (2023). Epidemiological Weekly Report No. 47, 2023 (Report).

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2023, December 12). Diphtheria - Guinea (2023). (Online). Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/nigeria/who-african-region-health-emergency-situation-report-multi-country-outbreak-diphtheria-consolidated-regional-situation-report-006-january-14-2024.

- Yakum MN, Ateudjieu J, Walter EA, Watcho P. Vaccine storage and cold chain monitoring in the North West region of Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. BMC Research Notes. 2015 Apr 14;8(1). [CrossRef]

- Kartoglu U, Ames H. Ensuring quality and integrity of vaccines throughout the cold chain: the role of temperature monitoring. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2022 Apr 8;21(6):799–810. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, A. The development of a plan for a comprehensive review of the vaccine storage and handling practices in the general practice setting. Memorial University of Newfoundland; 2015.

- Das A, Ilango K. Challenges Of Storage And Transport Of Covid-19 Vaccines–A Review. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results. 2022;4164–72.

- Hunt, GD. Development of an Improved Backpack Container to Enhance Vaccine Distribution in the Cold Chain Systems of Rural Southeast Asia. LeTourneau University; 2019.

- Kartoglu U, Milstien J. Tools and approaches to ensure the quality of vaccines throughout the cold chain. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2014 May 28;13(7):843–54. [CrossRef]

- Swayne DE, Suarez DL, Spackman E, Jadhao S, Dauphin G, Kim-Torchetti M, et al. Antibody Titer Has Positive Predictive Value for Vaccine Protection against Challenge with Natural Antigenic-Drift Variants of H5N1 High-Pathogenicity Avian Influenza Viruses from Indonesia. Journal of Virology. 2015 Apr;89(7):3746–62. [CrossRef]

- Janani M, Venkatesh ND. Clinical evaluation of vaccines. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research. 2019;11(5):1775–80.

- Verch T, Trausch JJ, Shank-Retzlaff M. Principles of vaccine potency assays. Bioanalysis. 2018 Feb;10(3):163–80. [CrossRef]

- Sanyal G. Development of functionally relevant potency assays for monovalent and multivalent vaccines delivered by evolving technologies. npj Vaccines. 2022 May 5;7(1). [CrossRef]

- Peretti-Watel, P., Seror, V., Cortaredona, S., Launay, O., Raude, J., Verger, P., Fressard, L., Beck, F., Legleye, S., L’Haridon, O., Léger, D., & Ward, J. K. (2020). A future vaccination campaign against COVID-19 at risk of vaccine hesitancy and politicisation. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20(7), 769–770. [CrossRef]

- Dubé, E. (2017). Addressing vaccine hesitancy: The crucial role of healthcare providers. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 23(5), 279–280. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z., Tong, Y., Du, F., Lu, L., Zhao, S., Yu, K., Piatek, S. J., Larson, H. J., & Lin, L. (2021). Assessing COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy, Confidence, and Public Engagement: A Global Social Listening Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(6), e27632. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020). Diphtheria vaccine: WHO position paper, August 2017.

- MacDonald, N. E. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 33(34), 4161–4164. [CrossRef]

- Betsch, C., Schmid, P., Heinemeier, D., Korn, L., Holtmann, C., & Böhm, R. (2018). Beyond confidence: Development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLOS ONE, 13(12), e0208601. [CrossRef]

- Tetanus vaccines: WHO position paper, February 2017 – Recommendations. (2018). Vaccine, 36(25), 3573–3575. [CrossRef]

- Larson, H. J., Schulz, W. S., Tucker, J. D., & Smith, D. M. D. (2015). Measuring Vaccine Confidence: Introducing a Global Vaccine Confidence Index. PLoS Currents. [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, S., Clark, S., Portnoy, A., Grewal, S., Stack, M. L., Sinha, A., Mirelman, A., Franklin, H., Friberg, I. K., Tam, Y., Walker, N., Clark, A., Ferrari, M., Suraratdecha, C., Sweet, S., Goldie, S. J., Garske, T., Li, M., Hansen, P. M., … Walker, D. (2017). Estimated economic impact of vaccinations in 73 low- and middle-income countries, 2001–2020. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 95(9), 629–638. [CrossRef]

- Grassly, N. C. (2013). The final stages of the global eradication of poliomyelitis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368(1623), 20120140.

- Dubé, E., Laberge, C., Guay, M., Bramadat, P., Roy, R., & Bettinger, J. A. (2013). Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 9(8), 1763–1773. [CrossRef]

- Allison, M. A., Dunne, E. F., Markowitz, L. E., O’Leary, S. T., Crane, L. A., Hurley, L. P., Stokley, S., Babbel, C. I., Brtnikova, M., Beaty, B. L., & Kempe, A. (2013). HPV Vaccination of Boys in Primary Care Practices. Academic Pediatrics, 13(5), 466–474. [CrossRef]

- Opel, D. J., Heritage, J., Taylor, J. A., Mangione-Smith, R., Salas, H. S., DeVere, V., Zhou, C., & Robinson, J. D. (2013). The Architecture of Provider-Parent Vaccine Discussions at Health Supervision Visits. Paediatrics, 132(6), 1037–1046. [CrossRef]

- Brunson, E. K. (2013). How parents make decisions about their children’s vaccinations. Vaccine, 31(46), 5466–5470. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, R. M., Targonski, P. V., & Poland, G. A. (2007). A taxonomy of reasoning flaws in the anti-vaccine movement. Vaccine, 25(16), 3146–3152. [CrossRef]

- Ophori, Endurance A., Musa Y. Tula, Azuka V. Azih, Rachel Okojie, and Precious E. Ikpo. 2014. “Current Trends of Immunization in Nigeria: Prospect and Challenges.” Tropical Medicine and Health 42 (2): 67–75. [CrossRef]

- Oluwadare, Christopher. 2009. “The Social Determinants of Routine Immunisation in Ekiti State of Nigeria.” Studies on Ethno-Medicine 3 (1): 49–56. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2006). The world health report 2006: working together for health. World Health Organization.

- Rosana, Y., Lusiana, D. I. G., & Yasmon, A. (2022). Genetic characterization of diphtheria tox B to evaluate vaccine efficacy in Indonesia. Iranian Journal of Microbiology, 14(4), 606.

- Lee, Min Hye, Gyeoung Ah Lee, Seong Hyeon Lee, and Yeon-Hwan Park. 2020. “A Systematic Review on the Causes of the Transmission and Control Measures of Outbreaks in Long-Term Care Facilities: Back to Basics of Infection Control.” PLOS ONE 15 (3): e0229911. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Diphtheria vaccine: WHO position paper. Weekly Epidemiological Record, 96(49), 609-620.

- World Health Organization. “Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report: 2021.” (2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022). Diphtheria vaccine: WHO position paper, August 2017.

- Idris, I., Ibrahim, I. and Umar, B.A., 2023. Re-emergence of diphtheria in Kano State, Nigeria: Current effort and challenges. Tropical Doctor, 1, p.2.

- Adepoju, V.A. , 2023. An Epidemic in the Making: The Urgent Need to Address the Diphtheria Outbreak in Nigeria: An Outbreak of Diphtheria in Nigeria. Nigerian Medical Journal, 64(1), pp.1-3.

- Africa CDC, 2023. https://africacdc.org/news-item/diphtheria-outbreak-in-africa-strengthening-response-capacities/.

- Cooper, S. and Wiysonge, C.S., 2023. Towards a More Critical Public Health Understanding of Vaccine Hesitancy: Key Insights from a Decade of Research. Vaccines, 11(7), p.1155.

- da Cunha, O.M.G. , 2020. Ruth’s Books: Creating Additional Lives. In The Things of Others: Ethnographies, Histories, and Other Artefacts (pp. 467-535). Brill.

- Medugu, N., Musa-Booth, T.O., Adegboro, B., Onipede, A.O., Babazhitsu, M. and Amaza, R., 2023. A review of the current diphtheria outbreaks. African Journal of Clinical and Experimental Microbiology, 24(2), pp.120-129.

- Oduoye, M.O., Musa, Z.M., Tunde, A.M., Nazir, A., Cakwira, H., Abdulkareem, L., Biamba, C., Akilimali, A., Kibukilza, F. and Nyakio, O., 2023. The recent outbreak of diphtheria in Nigeria is a public health concern for all. IJS Global Health, 6(5), p.e0274.

- Abubakar, M.Y., Lawal, J., Dadi, H. and Grema, U.S., 2020. Diphtheria: a re-emerging public health challenge. International Journal of Otorhinolaryngology and Health and Neck Surgery, 6(1), pp.191-193.

- Pan American Health Organization. (2020). Diphtheria in the Americas.

- Liu, J., Ng, T., Islam, M. A., Mahmud, S. M., Faruque, A. S. G., & Mahmud, S. M. (2021). Diphtheria outbreak in Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, 2020. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 72(12), e832-e834. [CrossRef]

- Ranaivo, A., Randrianasolo, L., Rakotonirina, L. P., Ramanantsoa, A., Herindrainy, P., & Andriantsitohaina, R. (2021). Diphtheria outbreak in Madagascar, 2019-2020: Lessons learned. Vaccine, 39(10), 1422-1427. [CrossRef]

- Diphtheria in asylum workers: forgotten but not gone!. International Journal of Surgery, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Martina, Esposito., Francesca, Minnai., M., Copetti., Giuseppe, Miscio., Rita, Perna., Ada, Piepoli., G., De, Vincentis., Mario, Benvenuto., Paola, D’Addetta., Susanna, Croci., Margherita, Baldassarri., Mirella, Bruttini., Chiara, Fallerini., Raffaella, Brugnoni., Paola, Cavalcante., Fulvio, Baggi., E., Corsini., Emilio, Ciusani., Francesca, Andreetta., Tommaso, A, Dragani., Maddalena, Fratelli., Massimo, Carella., Renato, E, Mantegazza., Alessandra, Renieri., Francesca, Colombo. Human leukocyte antigen variants associate with BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine response. Communications medicine, (2024). [CrossRef]

| Vaccine Type | Description | Age Group | Primary Series Schedule | Booster Dose Schedule | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTP (Whole-cell) | Contains inactivated whole cells of Bordetella pertussis, along with diphtheria and tetanus toxoids | Infants and young children | 2, 4, 6 months | 15-18 months, 4-6 years | Cherry M, et al. J Infect Dis. 1980;142(6):563-572. Greco P, et al. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(6):341-348. |

| DTaP (Acellular) | Contains purified antigens of Bordetella pertussis, diphtheria, and tetanus toxoids | Infants and young children | 2, 4, 6 months | 15-18 months, 4-6 years | Klein ES, et al. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):1-9. Schmitt B, et al. Pediatrics. 1998;101(1):1-7. |

| DT (Pediatric) | Contains diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, used when pertussis component is contraindicated | Children with contraindications to pertussis vaccine | 2, 4, 6 months | 15-18 months, 4-6 years | Healy JC, et al. Pediatrics Rev. 1998;19(2):70-77. |

| Td (Adult) | Contains lower doses of diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, used as a booster for adults | Adolescents and adults | - | Every 10 years after the initial Tdap dose | Zeigler PE, et al. JAMA. 2002;288(6):665-670. Plotkin LC, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;35(2):246-252. |

| Tdap (Adult/Pediatric) | Contains lower doses of diphtheria, tetanus toxoids, and acellular pertussis, used as a booster for older children, adolescents, and adults | Adolescents (11-12 years) and adults | - | 11-12 years (single dose), then Td every 10 years | Quinn MJR, et al. Vaccine. 2006;24(33-34):5686-5694. Cohn SP, et al. J Infect Dis. 2015;212(3):S10-S17. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).