Submitted:

26 September 2024

Posted:

27 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Literature

2. Data and Methods

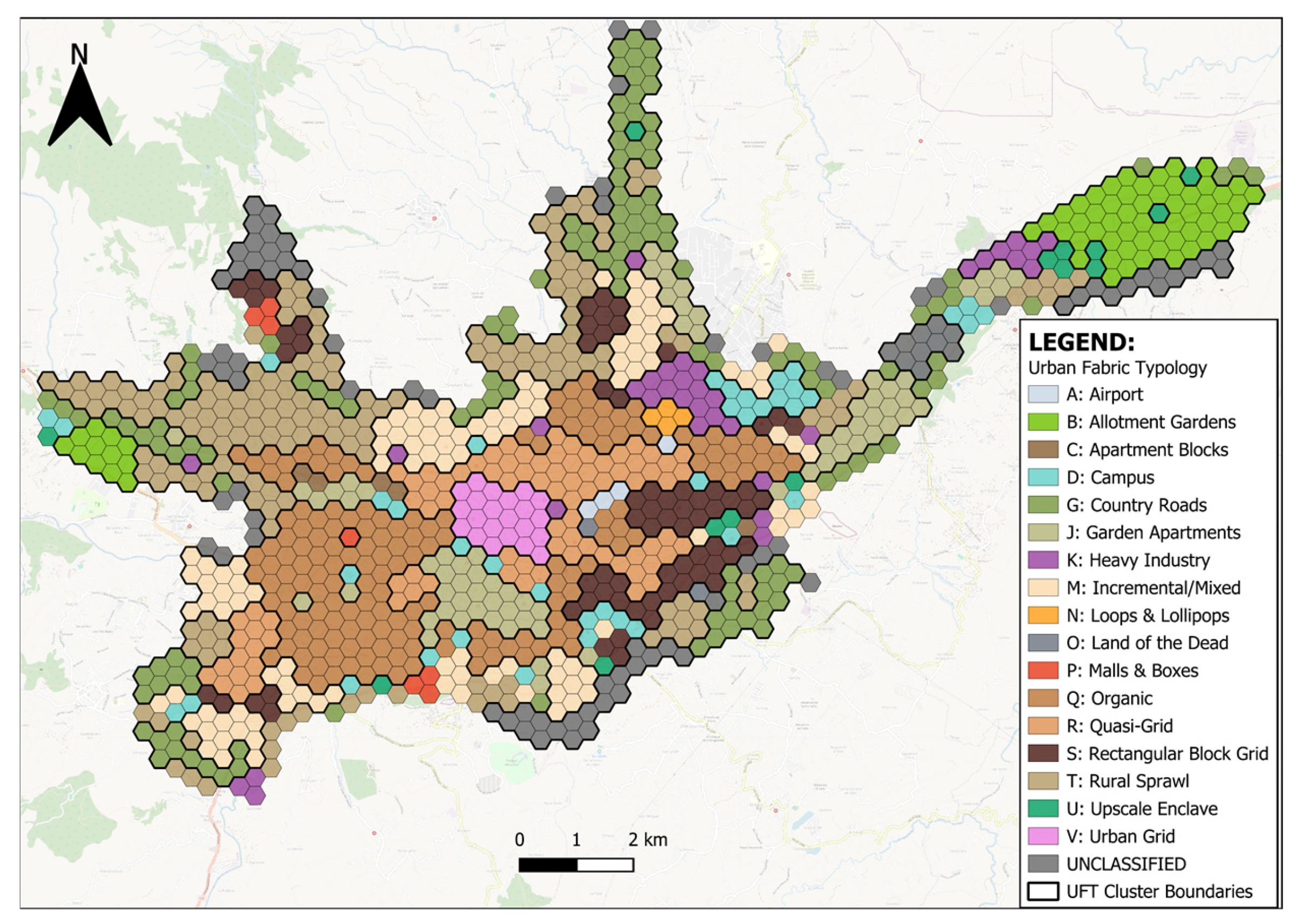

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.3. Methods

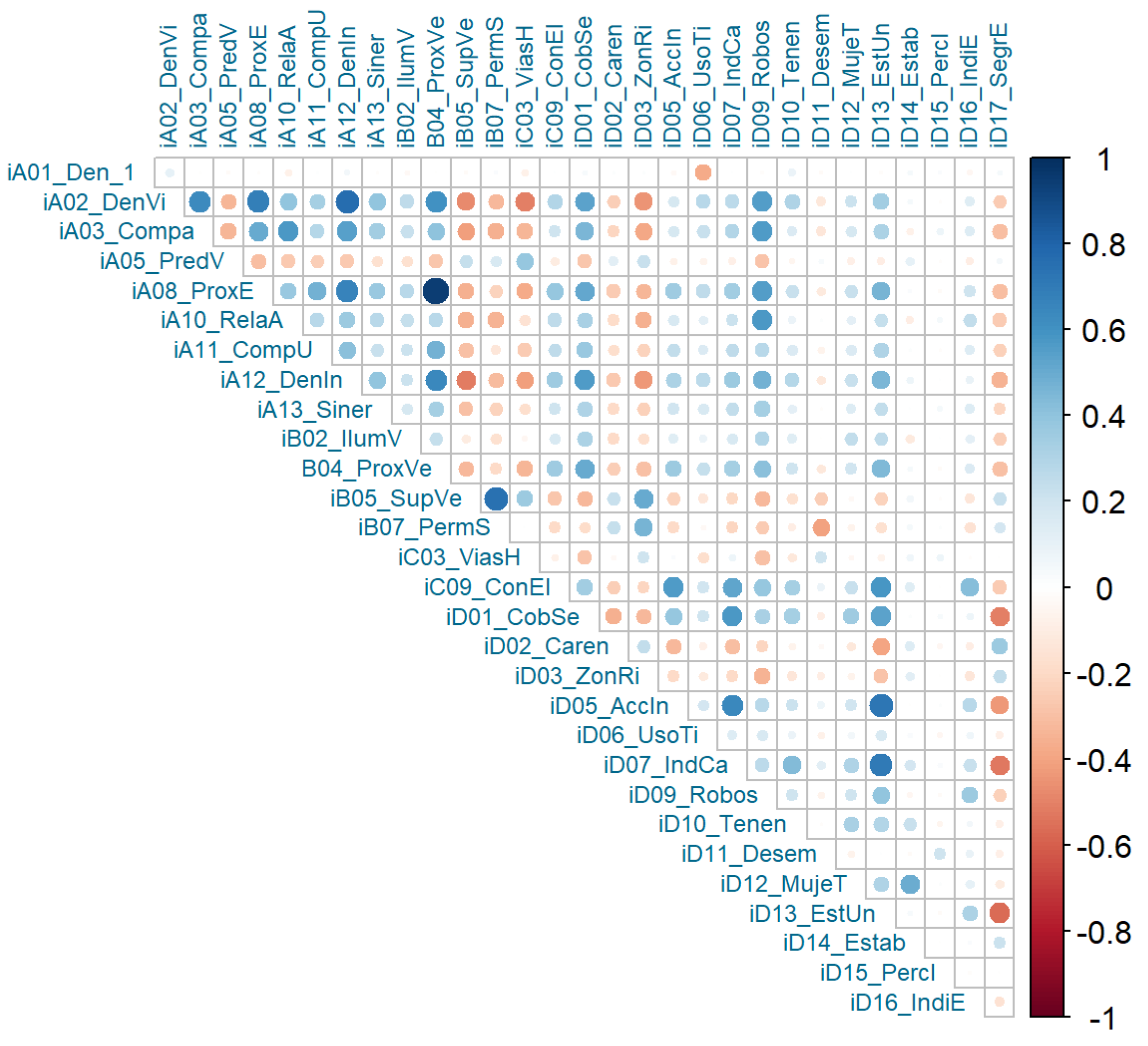

2.3.1. Initial Statistical Tests

2.3.2. Statistical and Geospatial Methods

- Outliers for each USI are statistically treated first, based on the following criteria:

- Then, each USI is normalised against its maximum value (upper limit, after truncation) in the [0, 1] domain. Note that this normalisation process is chosen instead of Z-scores, as centring values around zero would be inadequate for adding sustainability to all USIs.

-

The composite sustainability index consists of a linear combination (algebraic sum) of the 30 normalised USIs.

- o

- Note that some USIs are defined negatively regarding sustainability (e.g., unemployment). Hence, they enter the algebraic sum with a negative sign. The negative USIs are: A5, A10, D2, D3, D9, D11, D15, and D16. The logic is simple: Since they are negatively defined, the magnitude of a given negative USI (their ideal values being zero) reduces overall sustainability.

- o

- D17 is a particular case since its construction sets its optimal value as 1, and sustainability decreases both for values greater than 1 and lower than 1. Thus, the normalisation for this index consists of recentring it around zero (subtracting 1 from all values) and then converting negative values to absolute positive values. The normalised version of D17 measures a bidirectional distance from the optimal value.

3. Results

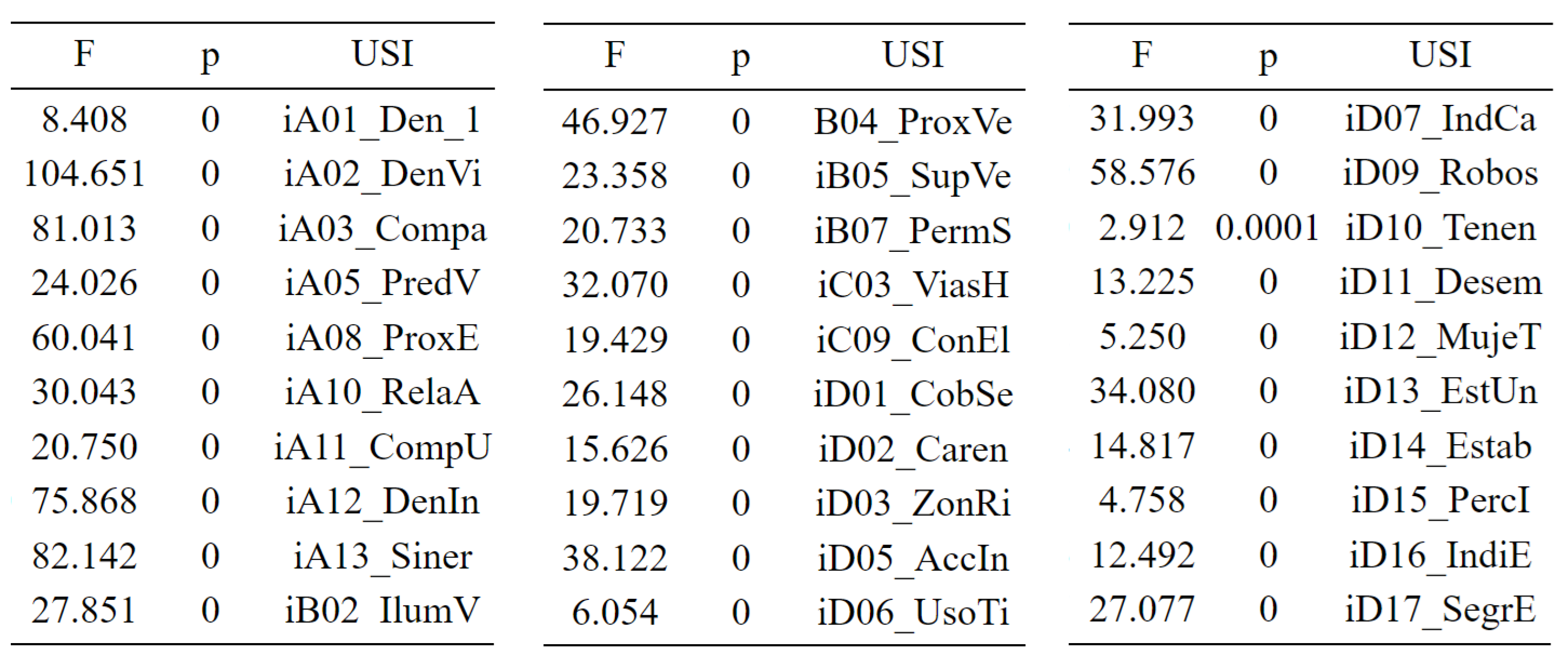

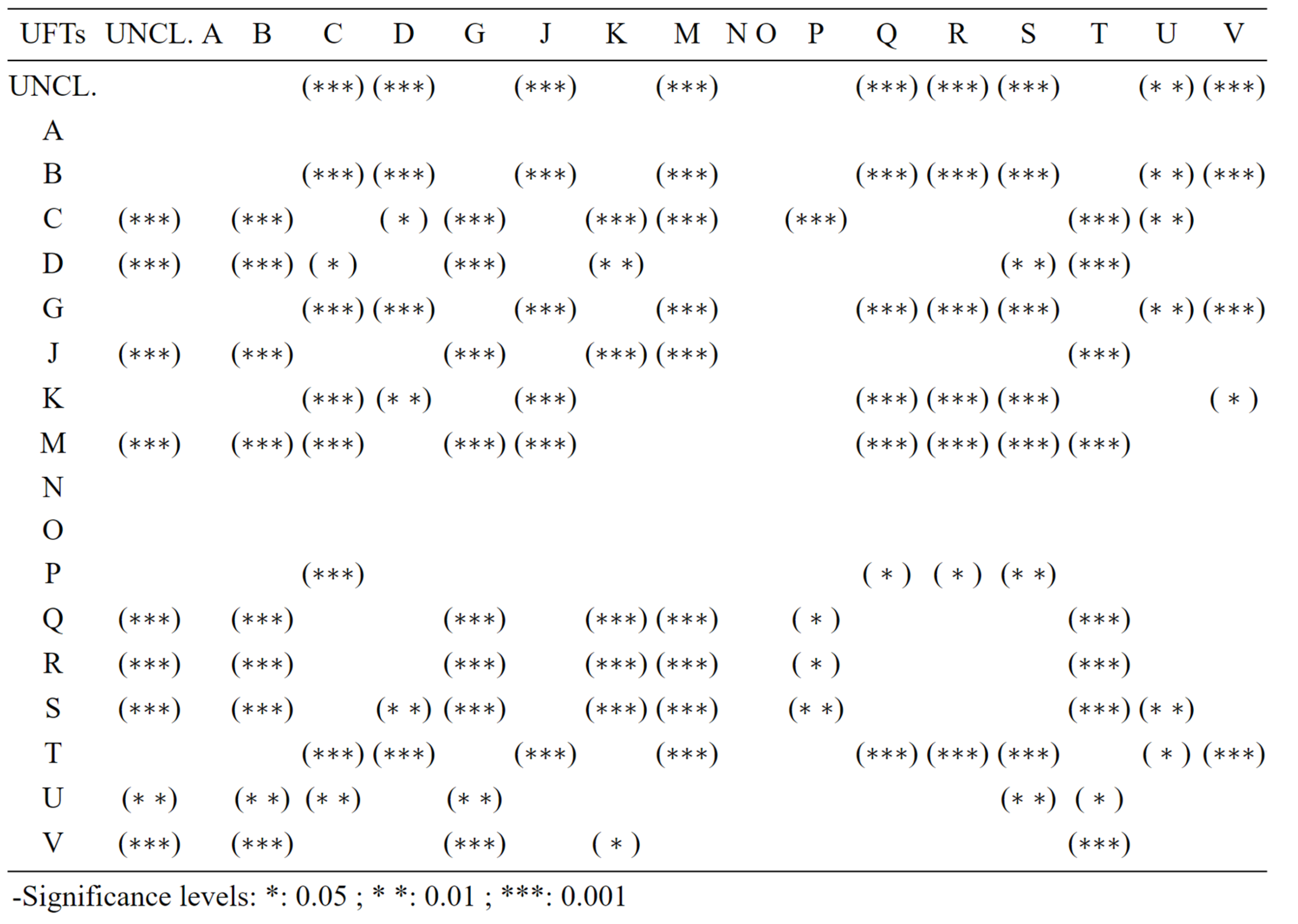

3.1. One-Way ANOVA Tests

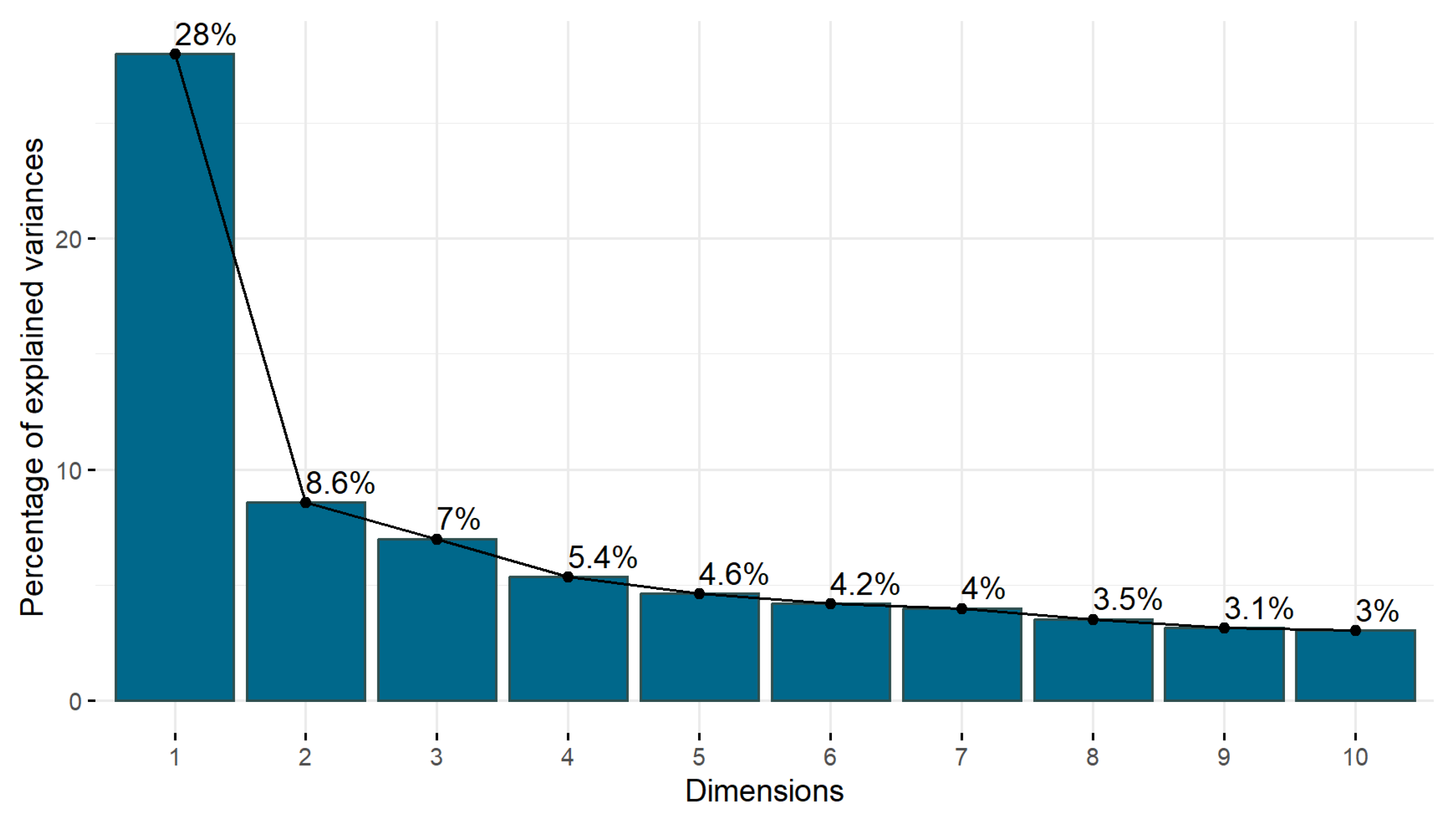

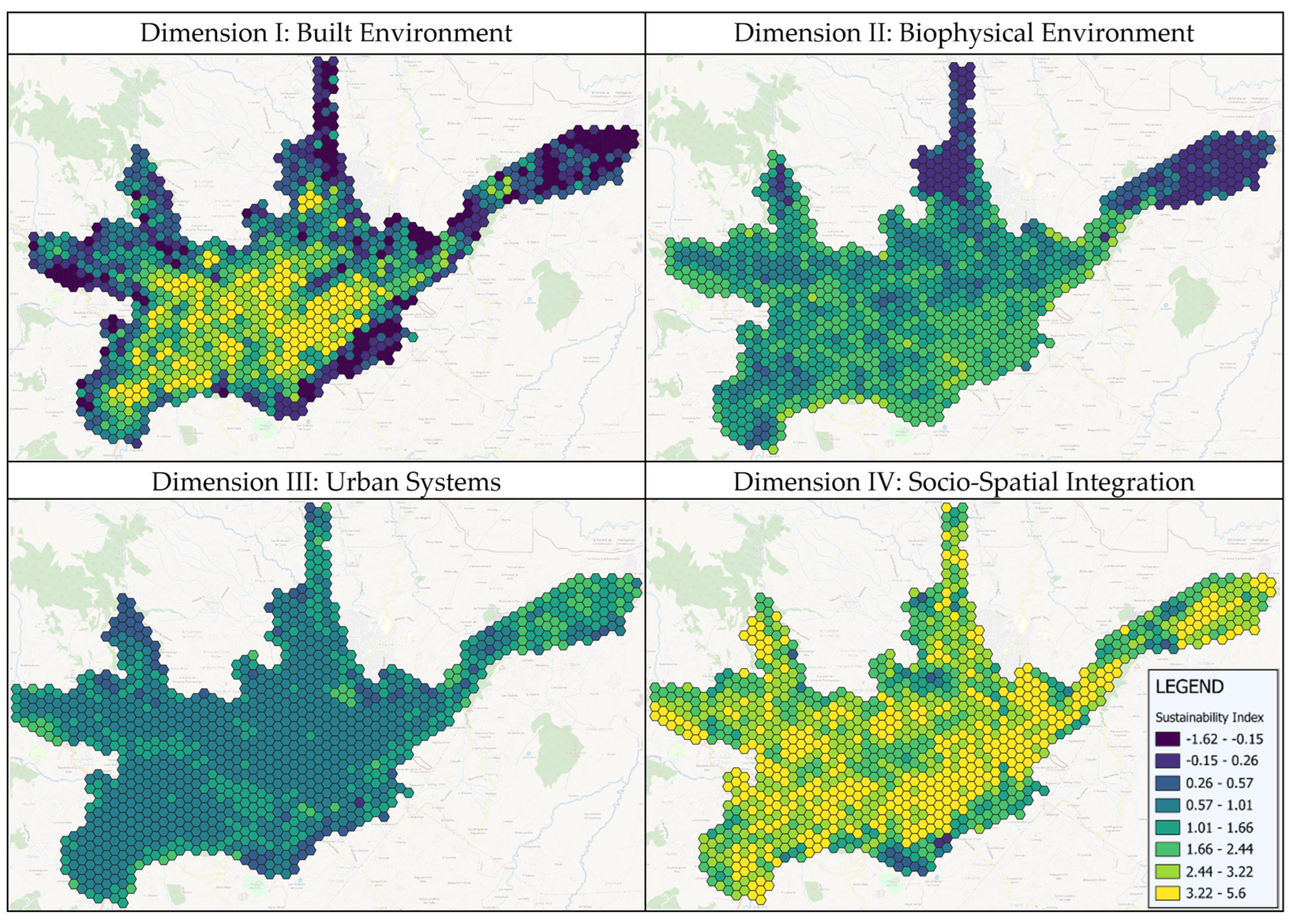

3.2. Principal Component Analysis

3.3. Composite Sustainability: Statistical Analyses

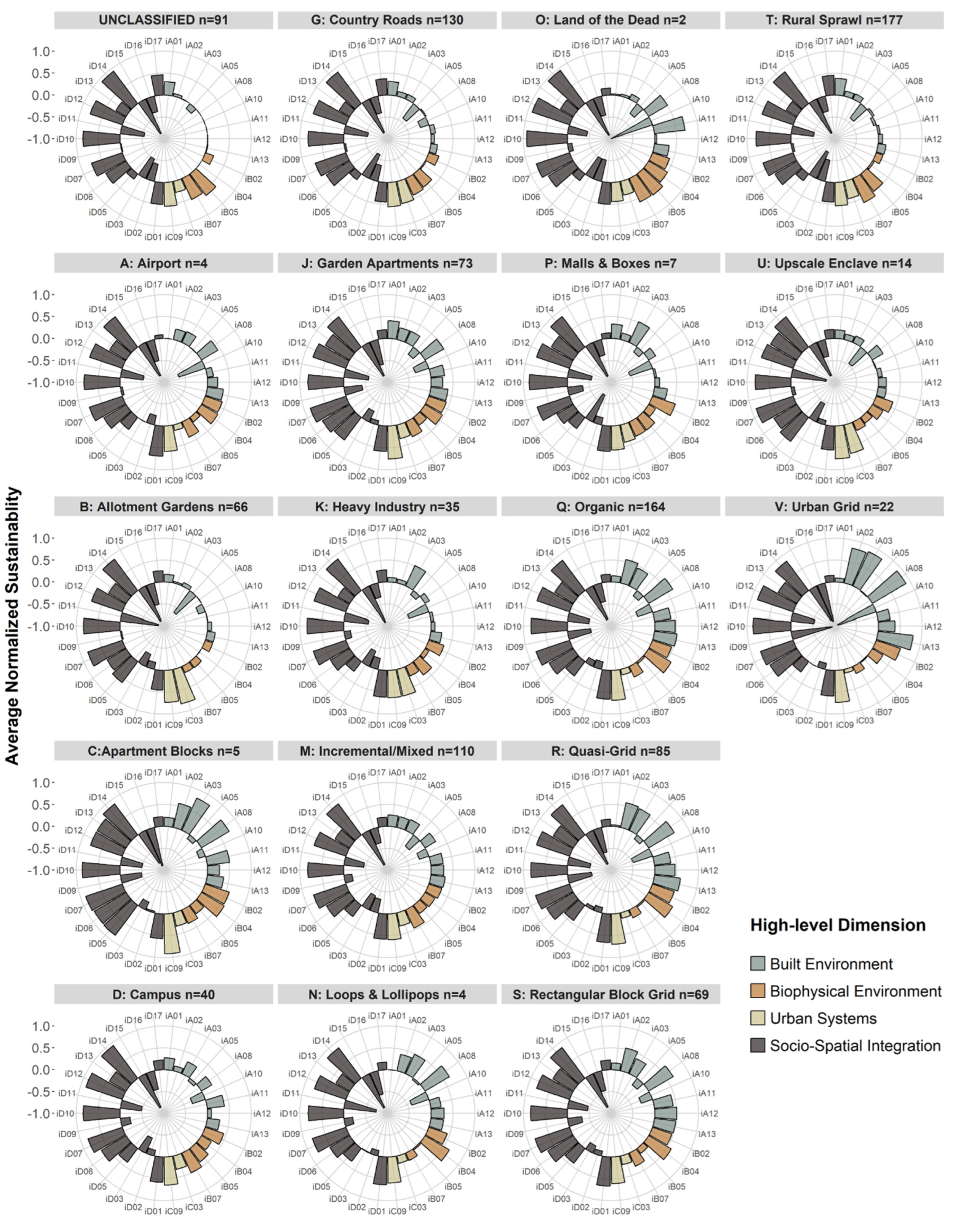

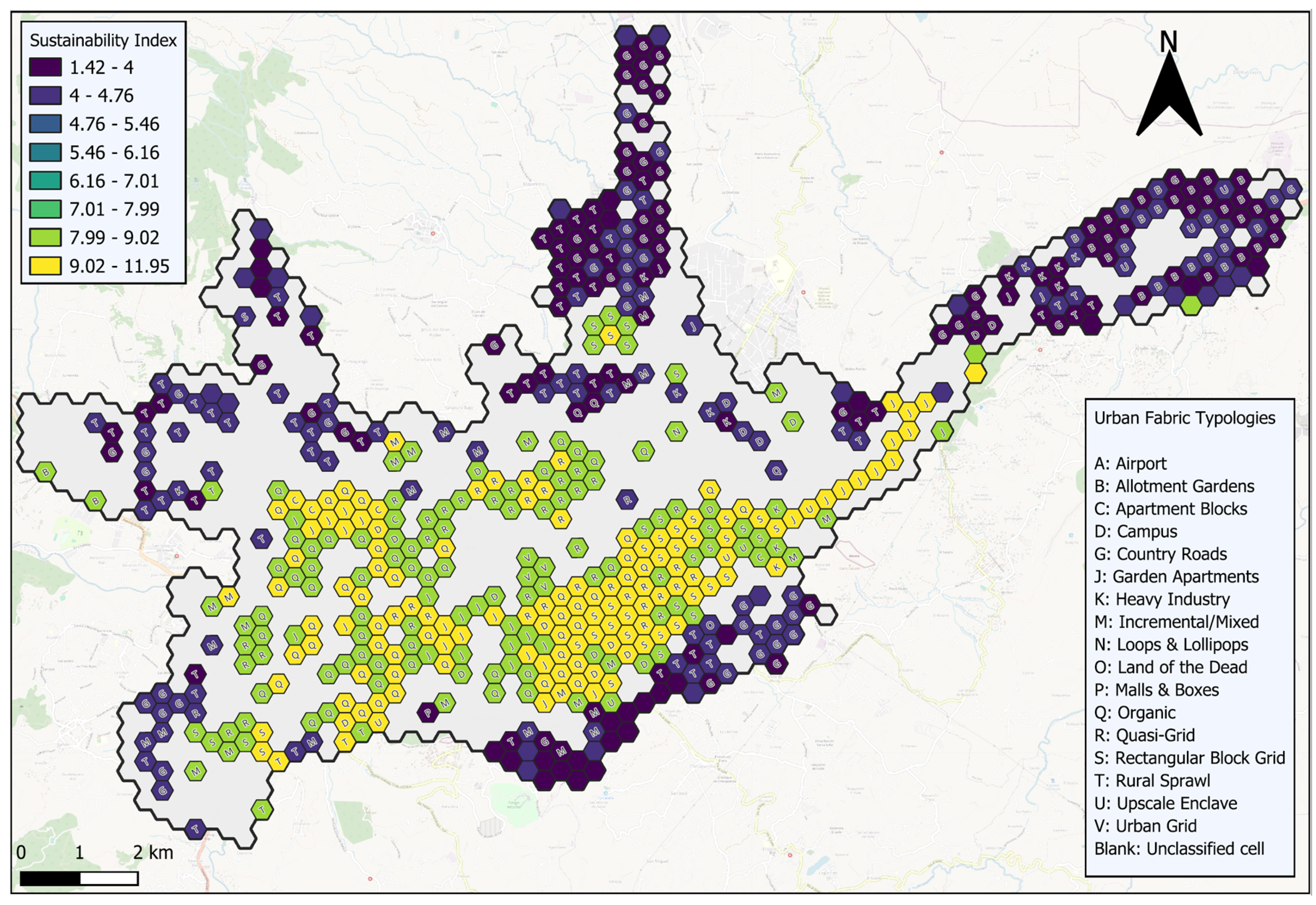

3.4. Composite Sustainability: Data Visualisation and Analysis

3.5. Spatial Analyses

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | ECUADOR NATIONAL CENSUS 2022: https://www.censoecuador.gob.ec/resultados-censo/. |

| 2 | GeoLlactaLAB: Geonode LlactaLAB; http://201.159.223.152/layers/geonode_data:geonode:CompletoIndicad. |

| 3 | GeoLlactaLAB: Geonode LlactaLAB; http://201.159.223.152/layers/geonode_data:geonode:CompletoIndicad. |

| 4 | QGIS: https://www.qgis.org/. |

| 5 |

ggradar R package: https://r-graph-gallery.com/web-radar-chart-with-R.html. |

| 6 | R Statistical Software: https://www.r-project.org/. |

| 7 |

factoextra R package: https://rpkgs.datanovia.com/factoextra/index.html. |

| 8 | LlactaLAB: Ciudades Sustentables official website: https://llactalab.ucuenca.edu.ec/sisurbano/. |

| 9 | Modelo de Evaluación de Sustentabilidad Urbana Espacial – MESUE: https://github.com/llactalab/mesue. |

| 10 | LlactaLAB: Ciudades Sustentables official website – SISURBANO: https://llactalab.ucuenca.edu.ec/sisurbano/. |

References

- Aureli, P.; Turan, N. [Re]Form: New Investigations in Urban Form, Panel 1. Harvard GSD 2018. https://youtu.be/0L7Anlsu2A4.

- Doug Allen Institute. Streets Lecture—Part 1 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NA2jpARqS7A&feature=youtu.be.

- Park, K.; Ewing, R.; Sabouri, S.; & Larsen, J. Street life and the built environment in an auto-oriented US region. Cities 2019, 88, 243–251. [CrossRef]

- González, L.G.; Siavichay, E.; Espinoza, J.L. Impact of EV fast charging stations on the power distribution network of a Latin American intermediate city. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 107, 309–318. [CrossRef]

- Mackay, H. Mapping and characterising the urban agricultural landscape of two intermediate-sized Ghanaian cities. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 182–197. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The New Urban Agenda. United Nations: Quito, Ecuador 2017; ISBN 978-92-1-132731-1.

- Valente, R.; Berry, B. Dissatisfaction with city life? Latin America revisited. Cities 2016, 50, 62-67. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ayllon, S. Rapid development as a factor of imbalance in urban growth of cities in Latin America: A perspective based on territorial indicators. Habitat International 2016, 58, 127–142. [CrossRef]

- Smets, P.; Salman, T. The multi-layered-ness of urban segregation. On the simultaneous inclusion and exclusion in Latin American cities. Habitat International 2016, 54, 80–87. [CrossRef]

- van Lindert, P. Rethinking urban development in Latin America: A review of changing paradigms and policies. Habitat International 2016, 54, pp. 253-264. [CrossRef]

- Thomson, G.; Newman, P. Urban fabrics and urban metabolism—from sustainable to regenerative cities. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2018, 132, 218–229. [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Neto, G.; Pinto, L.; Giannetti, A.; de Almeida, C. A framework of actions for strong sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 196, pp. 1629-1643. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. Urban sustainability assessment: An overview and bibliometric analysis. Ecological Indicators 2021, 121. [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Raghubanshi, A. Urban sustainability indicators: Challenges and opportunities. Ecological Indicators 2018, 93, pp. 282-291. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, F.; Borthagaray, A.; Marques, A.; Chong, J.; Strobel, J.; Bonilla, L.; Mondino, M.; Pineda, M.; Ellinger, P.; Carrasco, P.; Nemirovsky, Y. La ciudad como sistema: metabolismo, resiliencia y sustentabilidad. Ediciones Irradia. Disruptiva. 2023; 1ª ed, ISBN 978-987-48044-3-3.

- Wheeler, S. Built Landscapes of Metropolitan Regions: An International Typology. Journal of the American Planning Association 2015, 81, 167–190. [CrossRef]

- Hermida, M.; Calle, C.; Cabrera, N. La ciudad empieza aquí: metodología para la construcción de barrios compactos sustentables. Universidad de Cuenca: Cuenca, Ecuador 2015, ISBN 978-9978-14-318-6.

- Hermida, M.; Cobo, D.; Neira, C. Challenges and Opportunities of Urban Fabrics for Sustainable Planning In Cuenca (Ecuador). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2019, 290. [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M.; Benayas, J.; Justel, A.; Sisto, R.; Montes, C.; Sanz-Casado, E. A holistic index-based framework to assess urban resilience: Application to the Madrid Region, Spain. Ecological Indicators 2024, 166. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang; X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, L. Identification of 71 factors influencing urban vitality and examination of their spatial dependence: A comprehensive validation applying multiple machine-learning models. Sustainable Cities and Society 2024, 108. [CrossRef]

- Higgs, C.; Alderton, A.; Rozek, J.; Adlakha, D.; Badland, H.; Boeing, G.; … Giles-Corti, B. Policy-Relevant Spatial Indicators of Urban Liveability And Sustainability: Scaling From Local to Global. Urban Policy and Research 2022, 40(4), 321–334. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Quan, Y.; Li, X.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Song, W.; Lu, J.; Wu, G. Characterizing and analyzing the sustainability and potential of China’s cities over the past three decades. Ecological Indicators 2022, 136. [CrossRef]

- Lo-Iacono-Ferreira, V.; Garcia-Bernabeu, A.; Hilario-Caballero, A.; & Torregrosa-López, J. Measuring urban sustainability performance through composite indicators for Spanish cities. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 359. [CrossRef]

- Halla, P.; Merino-Saum, A. Conceptual frameworks in indicator-based assessments of urban sustainability—An analysis based on 67 initiatives. Sustainable Development, 30(5), 1056–1071. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Espada, M.; García, F.M.M.; González-Escobar, R. Urban Equity as a Challenge for the Southern Europe Historic Cities: Sustainability-Urban Morphology Interrelation through GIS Tools. Land 2022, 11, 1929. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Espada, M.; Martínez García, F.M.; González-Escobar, R. Sustainability Indicators and GIS as Land-Use Planning Instrument Tools for Urban Model Assessment. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2023, 12, 42. [CrossRef]

- Jorge-Ortiz, A.; Braulio-Gonzalo, M.; Bovea, M.D. Assessing urban sustainability: a proposal for indicators, metrics and scoring—a case study in Colombia. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2023, 25, 11789–11822. [CrossRef]

- Mobaraki, A.; Oktay Vehbi, B. A Conceptual Model for Assessing the Relationship between Urban Morphology and Sustainable Urban Form. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2884. [CrossRef]

- Programa de las Naciones Unidas para los Asentamientos Humanos. Construcción de Ciudades más Equitativas, Políticas públicas para la inclusión en América Latina. United Nations: Nairobi, Kenia 2014, ISBN 978-92-1-132605-5.

- United Nations Cuenca Declaration for Habitat III “Intermediate Cities: Urban Growth and Renewal”. Available online: http://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/Declaration-Cuenca.pdf (accessed on Oct 17, 2019).

- Cabrera, N.; Hermida, M., Orellana, D., Osorio, P. Assessing the sustainability of urban density. Indicators in the case of Cuenca (Ecuador). Bitácora Urbano Territorial 2015, 25(2). [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C; Weaver, W. The mathematical theory of communication. The University of Illinois Press—Urbana 1964, 14, pp. 306–317. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9230594.

- Openshaw, Stan. The modifiable areal unit problem. Norwick: Geo Books 1983. ISBN 0860941345. OCLC 12052482.

- Burch, M.; Weiskopf, D. On the Benefits and Drawbacks of Radial Diagrams. Handbook of Human Centric Visualization 2014, pp.429-451. 1st ed. Springer; New York, NY, USA. ISBN 978-3-540-30750-1.

- Shawly, H. Evaluating Compact City Model Implementation as a Sustainable Urban Development Tool to Control Urban Sprawl in the City of Jeddah. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13218. [CrossRef]

| Study Area: Cuenca (as of 2022, the latest national census)1 | |

| Area | 7248.23 ha |

| Inhabitants | 361524 |

| Households | 115477 |

| Population Density | 49.87 inh/ha |

| Household Density | 15.93 households/ha |

| No. | Name | Description |

| Dimension I: Built Environment | ||

| A01 | Net population density | Number of Inhabitants per hectare. |

| A02 | Net housing density | Number of houses per hectare. It evidences the consumption of residential land. |

| A03 | Absolute compactness | Building intensity equivalent to building volume on a given surface. |

| A05 | Empty lot areas | Percentage of unused land or buildings on the block. |

| A07 | Proximity to basic urban facilities | Percentage of households with simultaneous access within 500m to all types of basic urban facilities. |

| A08 | Proximity to open public space | The percentage of households within a 5-minute walk of at least one type of open public space (park, plaza, sports field, riverbank, open market). |

| A09 | Accessibility to purchasing basic daily supplies. | Percentage of households with simultaneous coverage within a 300m radius of different basic supplies necessary for daily life. |

| A10 | Relation between activity and residence | Urban variety and equilibrium are measured by the proportion of non-residential economic activities (commerce, services, offices) and the number of households. This indicator reflects a territory’s capacity to be self-contained in terms of mobility. |

| A11 | Urban complexity | Diversity and frequency of land uses. It relies on Shannon´s formula of entropy [32] to evidence the mixture of activities. |

| A12 | Pedestrian crossings density | Pedestrian connectivity of a territory, as the proportion of street pedestrian crossings to the whole study area. |

| A13 | Synergy | Degree to which the internal structure of an observational unit relates to a higher scale at the system level, according to spatial syntax theory. |

| Dimension II: Biophysical Environment | ||

| B01 | Air quality index | Amount of population not exposed to emission levels beyond the maximum permitted by Ecuadorian normative. Contaminants considered simultaneously (NO2, CO, SO2, O3, MP2.5, and MP10). |

| B02 | Nocturnal illumination of public streets | Proportion of the number of illumination devices to the lineal kilometres of public streets. Measures the perception of safety associated with illumination. |

| B03 | Acoustic comfort | Amount of population not exposed to noise levels beyond the maximum permitted by Ecuadorian normative. Max noise levels are 70dB at day and 65dB at night. |

| B04 | Proximity to green spaces | Closeness of the population to the nearest green space. |

| B05 | Green area per inhabitant | Ratio of public green space and the number of inhabitants. |

| B07 | Soil permeability | Area of permeable soil with respect to total area. It relates to loss of permeability caused by urban expansion, in terms of buildings and pavement. |

| Dimension III: Urban Systems | ||

| C03 | Public roads per inhabitant | Ratio of public road lanes (lineal metres) and population. |

| C04 | Proximity to alternative transport networks | Percentage of the population with simultaneous access to at least three alternative transport networks within 300m (bus, public bike share, bike paths, pedestrian paths; 500m for tram). |

| C09 | Electricity consumption of the household | Ratio of electricity consumption of the household by the number of residents in the household. |

| C13 | Wastewater coverage | Percentage of households connected to the public wastewater system. |

| Dimension IV: Socio-Spatial Integration | ||

| D01 | Households fully covered by basic services | Percentage of households with simultaneous access to drinkable water, electricity, wastewater and solid waste disposal. |

| D02 | Households with critical construction defects | Percentage of households with critical construction defects (that can endanger residents). |

| D03 | Dwellings located at risk zones | Percentage of households located at risk zones (landslide, flooding, topographically compromised, geologically compromised, agricultural zones, forestry zones, natural protection zones). |

| D05 | Internet access | Percentage of households that can connect to internet services by computer or mobile. |

| D06 | Use of time | Average time spent on personal activities within a working week (Mon-Fri), for the population aged 12 years and older. |

| D07 | Life conditions index | Level of scarcity or abundance of the following household variables: a) physical characteristics; b) basic services; c) education of residents aged 6 years and older ; d) access to health insurance. |

| D08 | Closeness and access to food | Spatial distribution of the city in terms of food purchasing locations (understood as: within 10 minutes from a public market). |

| D09 | Thefts per year | Ratio of thefts to people, households, institutions, retail and vehicles in the study area, to the total thefts in the city. |

| D10 | Housing security | Percentage of households with secured access to a dwelling (owned or rented). |

| D11 | Unemployment rate | Percentage of the economically active population (aged 15 and older) that is unemployed. |

| D12 | Women at paid workforce | Percentage of paid women in the workforce with respect to total employment (excluding agriculture). |

| D13 | Economically active population with a university degree | Percentage of the economically active population (aged 15 and older) with a completed university degree. |

| D14 | Stability of community | Percentage of the population living in the same place (parish) for 5 or more years. |

| D15 | Unsafety perception | Percentage of citizens that feel unsafe in their neighbourhoods. |

| D16 | Population ageing index | Quantitative ratio of older-adult population (aged 65 and more) to infant-young population (aged 0 to 15). |

| D17 | Spatial segregation | Level of exclusion, cohesion or segregation of the population with greater shortcomings (who fall within the first quartile of the Life Quality Index). |

| UFT | Code | Description |

| Airports | A | Large access roads, landing strips or parking spaces for transport buses. Land use is commercial, with large-scale terminal buildings and parking. Few green spaces. |

| Allotment gardens | B | Lane access is generally narrow and not paved. Housing units have ample green or recreational spaces; they may also have small agriculture fields. Parking is usually external to the garden area. |

| Apartment blocks | C | Medium and large blocks with moderate connectivity. Multifamily residences with shops or offices on the ground floor. Buildings are relatively tall (at least three stories). Parking lots and scarce green spaces. |

| Campus | D | Internal circulation routes. Single-use large plot (institutional, corporate or recreational). Buildings are scattered on the site, with parking lots and green areas. |

| Country roads | G | Develops linearly following rural paths. Connectivity is deficient, intersections are infrequent and there is no formal block pattern. Long and narrow plots. Single-family homes, small multi-family buildings and some shops. Agricultural fields and open spaces. |

| Garden apartments | J | Access roads to the apartment buildings; however, connectivity is deficient. Large plots of multifamily residences, with parking spaces, and many green and recreational areas. |

| Heavy industry | K | Access roads are irregular, and blocks are large. Land use is intended for heavy manufacturing. Large-scale buildings, warehouse spaces and parking. Vegetation is minimal. |

| Incremental/mixed | M | Generally rectilinear streets with disordered patterns and bad connectivity. Block’s size and shape vary. Single family homes, some multifamily buildings and shops. Density varies between low and moderate. There may be plantations and random green spaces. |

| Loops & lollipops | N | Curvilinear and irregular streets. Land use is mainly single-family residential, there may be multifamily buildings and shops. Plots are homogeneous, and dwellings are usually row houses. Parking is on the street or at the entrance. There may be neighbourhood parks. |

| Land of the dead | O | Usually fenced to restrict access from the outside. Single-use large plot (burial). Small services and parking buildings. Abundant green area and trees. |

| Malls & boxes | P | Usually connected to main streets, avenues or highways. Large plot of commercial use with typically low but large buildings. Parking lots and minimal vegetation. |

| Organic | Q | Street patterns are irregular and according to the topography with moderate connectivity. Land use is mixed, and density varies from moderate to high. Buildings are diverse in form and scale. Parking lots can be on the street, and there are occasional parks. |

| Quasi-grid | R | Street patterns are rectilinear but irregular, with high connectivity. Block’s size and shape vary, and plots are small to medium size. Building’s shape is diverse and present small retreats. Green spaces and occasional parking lots. |

| Rectangular block grid | S | Streets form a regular grid of rectangular blocks, with high connectivity. Homogeneous plots of residential and commercial use. Row houses, and some multifamily or duplex buildings may exist. Parking lots are in the street or at the entrances. Occasional small parks. |

| Rural sprawl | T | Few discernible blocks and low connectivity, it is located near urban access roads. Land use is mostly residential, there may be small shops, offices and multifamily residences. Buildings size vary and retreats are present. Lot of vegetation and original ecosystem remnants. |

| Upscale enclave | U | Usually a closed set, with varied street patterns and bad connectivity. Low density. Plots are generally large with exclusive single-family homes. Parking lots are located in adjacent garages or at the houses’ entrance. Gardens and communal recreational areas. |

| Urban grid | V | Well-connected rectilinear streets that form a grid pattern. Blocks are small and have a mixed land use. Buildings’ size and scale vary and may have interior patios. There are lots and parking buildings. Formal parks and plazas (civic squares). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).