Submitted:

08 August 2024

Posted:

12 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Search Strategy

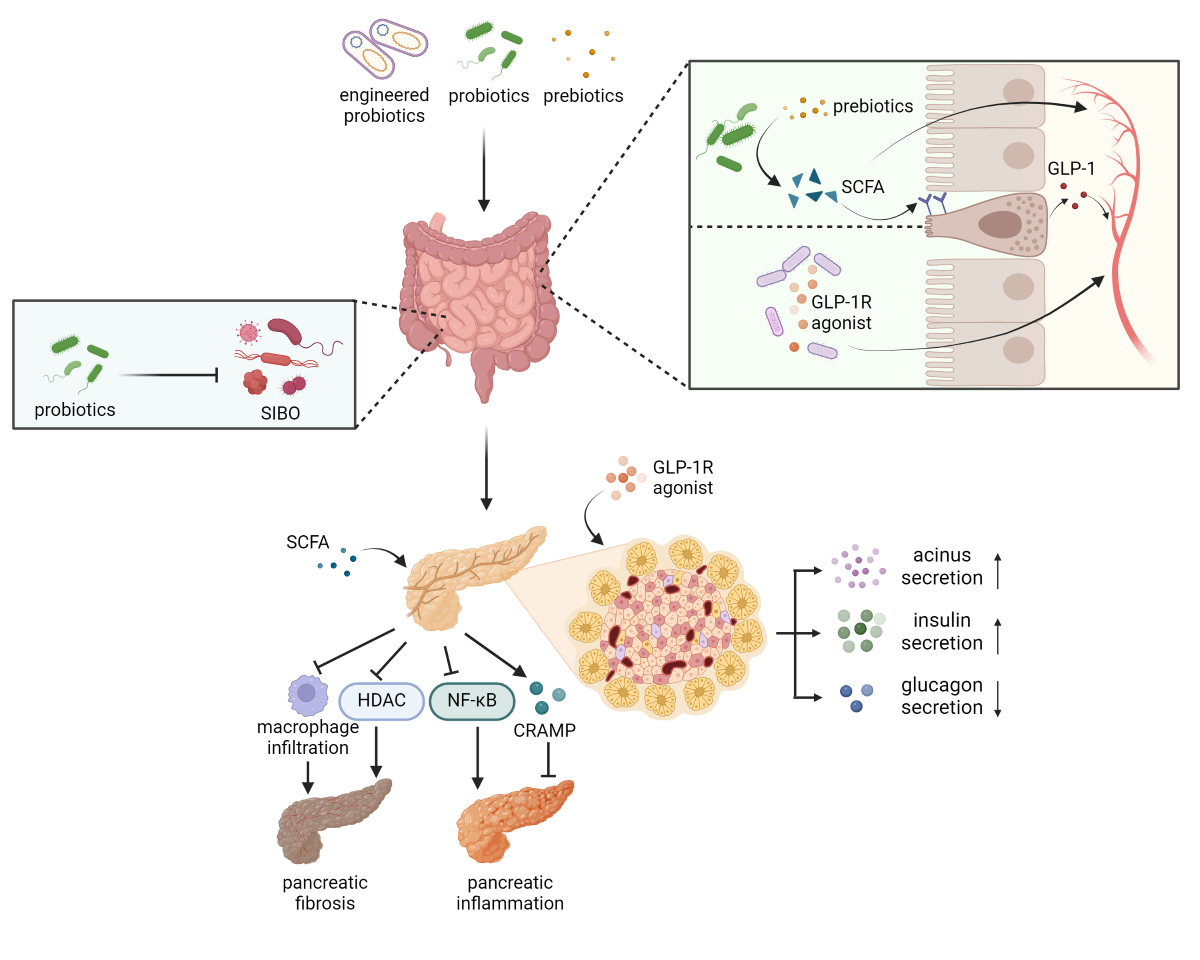

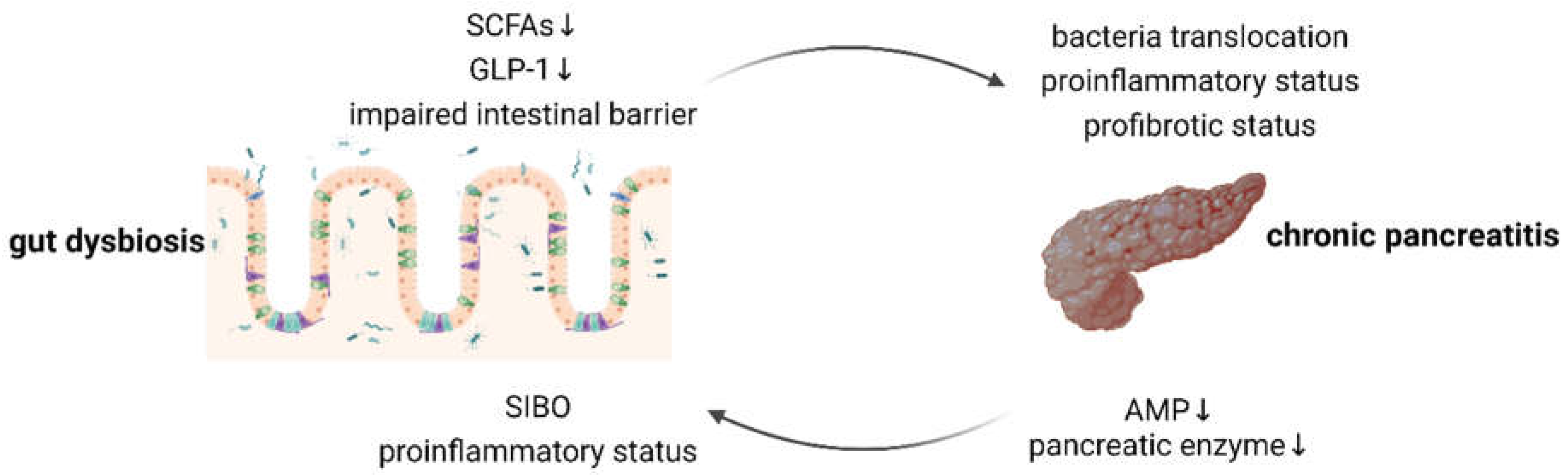

3. Alleviation of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth

4. Facilitation of Short-Chain Fatty Acids Production

5. Activation of Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptors in the Pancreas

| Genus | Species | Disease models | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus | L. casei CCFM419 | T2DM | [107] |

| L. plantarum MTCC5690 | [108] | ||

| L. fermentum MTCC5689 | [108] | ||

| Lactobacillus CGMCC No. 21661 | [109] | ||

| L. rhamnosus NCDC 17 | [110] | ||

| L. paracasei JY062 | Glycolipid metabolic disorders | [111] | |

| L. reuteri | Glucose metabolism disorder induced by acrylamide; glucose-tolerant humans | [112,113] | |

| L. paracasei subsp. paracasei L. casei W8 | isolated pig intestine | [114] | |

| Lacticaseibacillus | L. paracasei L-21 | STC-1 cell line | [115] |

| Bifidobacterium | selenium-enriched B. longum DD98 | T2DM | [116] |

| B. animalis subsp. lactis MN-Gup | [117] | ||

| B. animalis subsp. lactis NJ241 | Parkinson’s disease | [118] | |

| B. animalis subsp. lactis GCL2505 | Metabolic syndrome | [119] | |

| B. longum subsp. longum B-53 | STC-1 cell line | [115] | |

| Akkermansia | Pasteurized A. muciniphila | T2DM | [120] |

| Bacteroides | B. thetaiotaomicron | alcoholic fatty liver disease | [121] |

| Limosilactobacillus | L. fermentum MG4295 | T2DM | [122] |

| Clostridium | C. butyricum | chronic unpredictable mild stress; T2DM | [123,124] |

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- YADAV D, TIMMONS L, BENSON J T, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and survival of chronic pancreatitis: a population-based study [J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2011, 106(12): 2192-9. [CrossRef]

- YADAV D, MUDDANA V, O'CONNELL M. Hospitalizations for chronic pancreatitis in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, USA [J]. Pancreatology, 2011, 11(6): 546-52.

- MACHICADO J D, DUDEKULA A, TANG G, et al. Period prevalence of chronic pancreatitis diagnosis from 2001-2013 in the commercially insured population of the United States [J]. Pancreatology, 2019, 19(6): 813-8.

- PETROV M S, OLESEN S S. Metabolic Sequelae: The Pancreatitis Zeitgeist of the 21st Century [J]. Gastroenterology, 2023, 165(5): 1122-35.

- SINGH V K, YADAV D, GARG P K. Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Pancreatitis: A Review [J]. JAMA, 2019, 322(24): 2422-34.

- THOMAS R M, JOBIN C. Microbiota in pancreatic health and disease: the next frontier in microbiome research [J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2020, 17(1): 53-64.

- LUPU V V, BRATU R M, TRANDAFIR L M, et al. Exploring the Microbial Landscape: Gut Dysbiosis and Therapeutic Strategies in Pancreatitis-A Narrative Review [J]. Biomedicines, 2024, 12(3).

- SANDERS M E, MERENSTEIN D J, REID G, et al. Author Correction: Probiotics and prebiotics in intestinal health and disease: from biology to the clinic [J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019, 16(10): 642.

- BURES J, CYRANY J, KOHOUTOVA D, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome [J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2010, 16(24): 2978-90.

- GRACE E, SHAW C, WHELAN K, et al. Review article: small intestinal bacterial overgrowth--prevalence, clinical features, current and developing diagnostic tests, and treatment [J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2013, 38(7): 674-88.

- PIMENTEL M, SAAD R J, LONG M D, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth [J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2020, 115(2): 165-78.

- ZAFAR H, JIMENEZ B, SCHNEIDER A. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: current update [J]. Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 2023, 39(6): 522-8.

- EL KURDI B, BABAR S, EL ISKANDARANI M, et al. Factors That Affect Prevalence of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Chronic Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression [J]. Clin Transl Gastroenterol, 2019, 10(9): e00072. [CrossRef]

- LEE A A, BAKER J R, WAMSTEKER E J, et al. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth Is Common in Chronic Pancreatitis and Associates With Diabetes, Chronic Pancreatitis Severity, Low Zinc Levels, and Opiate Use [J]. Am J Gastroenterol, 2019, 114(7): 1163-71.

- Ní CHONCHUBHAIR H M, BASHIR Y, DOBSON M, et al. The prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in non-surgical patients with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI) [J]. Pancreatology, 2018, 18(4): 379-85.

- CAPURSO G, SIGNORETTI M, ARCHIBUGI L, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in chronic pancreatitis [J]. United European Gastroenterol J, 2016, 4(5): 697-705.

- RAO S S C, BHAGATWALA J. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Clinical Features and Therapeutic Management [J]. Clin Transl Gastroenterol, 2019, 10(10): e00078.

- SHAH S C, DAY L W, SOMSOUK M, et al. Meta-analysis: antibiotic therapy for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth [J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2013, 38(8): 925-34.

- REDONDO-CUEVAS L, BELLOCH L, MARTíN-CARBONELL V, et al. Do Herbal Supplements and Probiotics Complement Antibiotics and Diet in the Management of SIBO? A Randomized Clinical Trial [J]. Nutrients, 2024, 16(7).

- ROSANIA R, GIORGIO F, PRINCIPI M, et al. Effect of probiotic or prebiotic supplementation on antibiotic therapy in the small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a comparative evaluation [J]. Curr Clin Pharmacol, 2013, 8(2): 169-72.

- KHALIGHI A R, KHALIGHI M R, BEHDANI R, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of probiotic on treatment in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)--a pilot study [J]. Indian J Med Res, 2014, 140(5): 604-8.

- SOIFER L O, PERALTA D, DIMA G, et al. [Comparative clinical efficacy of a probiotic vs. an antibiotic in the treatment of patients with intestinal bacterial overgrowth and chronic abdominal functional distension: a pilot study] [J]. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam, 2010, 40(4): 323-7.

- ZHONG C, QU C, WANG B, et al. Probiotics for Preventing and Treating Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Current Evidence [J]. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2017, 51(4): 300-11.

- ASLAN I, TARHAN CELEBI L, KAYHAN H, et al. Probiotic Formulations Containing Fixed and Essential Oils Ameliorates SIBO-Induced Gut Dysbiosis in Rats [J]. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2023, 16(7). [CrossRef]

- BARRETT J S, CANALE K E K, GEARRY R B, et al. Probiotic effects on intestinal fermentation patterns in patients with irritable bowel syndrome [J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2008, 14(32): 5020-4.

- YAO C K, BARRETT J S, PHILPOTT H, et al. Poor predictive value of breath hydrogen response for probiotic effects in IBS [J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2015, 30(12): 1731-9.

- LEE S-H, JOO N-S, KIM K-M, et al. The Therapeutic Effect of a Multistrain Probiotic on Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Pilot Study [J]. Gastroenterol Res Pract, 2018, 2018: 8791916.

- LUO M, LIU Q, XIAO L, et al. Golden bifid might improve diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome via microbiota modulation [J]. J Health Popul Nutr, 2022, 41(1): 21.

- BUSTOS FERNáNDEZ L M, MAN F, LASA J S. Impact of Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 on Bacterial Overgrowth and Composition of Intestinal Microbiota in Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients: Results of a Randomized Pilot Study [J]. Dig Dis, 2023, 41(5): 798-809.

- HAO Y, XU Y, BAN Y, et al. Efficacy evaluation of probiotics combined with prebiotics in patients with clinical hypothyroidism complicated with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth during the second trimester of pregnancy [J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2022, 12: 983027.

- ZHANG M, XU Y, SUN Z, et al. Evaluation of probiotics in the treatment of hypothyroidism in early pregnancy combined with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth [J]. Food Sci Nutr, 2024, 12(4): 2671-8.

- OUYANG Q, XU Y, BAN Y, et al. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Subclinical Hypothyroidism of Pregnancy with Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth [J]. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins, 2024, 16(2): 579-88.

- GARCíA-COLLINOT G, MADRIGAL-SANTILLáN E O, MARTíNEZ-BENCOMO M A, et al. Effectiveness of Saccharomyces boulardii and Metronidazole for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Systemic Sclerosis [J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2020, 65(4): 1134-43.

- EFREMOVA I, MASLENNIKOV R, ZHARKOVA M, et al. Efficacy and Safety of a Probiotic Containing Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 in the Treatment of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Decompensated Cirrhosis: Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study [J]. J Clin Med, 2024, 13(3).

- FEROLLA S M, COUTO C A, COSTA-SILVA L, et al. Beneficial Effect of Synbiotic Supplementation on Hepatic Steatosis and Anthropometric Parameters, But Not on Gut Permeability in a Population with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis [J]. Nutrients, 2016, 8(7).

- KWAK D S, JUN D W, SEO J G, et al. Short-term probiotic therapy alleviates small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, but does not improve intestinal permeability in chronic liver disease [J]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2014, 26(12): 1353-9.

- LIANG S, XU L, ZHANG D, et al. Effect of probiotics on small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with gastric and colorectal cancer [J]. Turk J Gastroenterol, 2016, 27(3): 227-32.

- KANIKA G, KHAN S, JENA G. Sodium Butyrate Ameliorates L-Arginine-Induced Pancreatitis and Associated Fibrosis in Wistar Rat: Role of Inflammation and Nitrosative Stress [J]. J Biochem Mol Toxicol, 2015, 29(8): 349-59. [CrossRef]

- PAN L-L, REN Z-N, YANG J, et al. Gut microbiota controls the development of chronic pancreatitis: A critical role of short-chain fatty acids-producing Gram-positive bacteria [J]. Acta Pharm Sin B, 2023, 13(10): 4202-16.

- SUN J, FURIO L, MECHERI R, et al. Pancreatic β-Cells Limit Autoimmune Diabetes via an Immunoregulatory Antimicrobial Peptide Expressed under the Influence of the Gut Microbiota [J]. Immunity, 2015, 43(2): 304-17.

- VINOLO M A R, RODRIGUES H G, HATANAKA E, et al. Suppressive effect of short-chain fatty acids on production of proinflammatory mediators by neutrophils [J]. J Nutr Biochem, 2011, 22(9): 849-55.

- PARK J-S, LEE E-J, LEE J-C, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of short chain fatty acids in IFN-gamma-stimulated RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cells: involvement of NF-kappaB and ERK signaling pathways [J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2007, 7(1): 70-7.

- USAMI M, KISHIMOTO K, OHATA A, et al. Butyrate and trichostatin A attenuate nuclear factor kappaB activation and tumor necrosis factor alpha secretion and increase prostaglandin E2 secretion in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells [J]. Nutr Res, 2008, 28(5): 321-8.

- PARK G Y, JOO M, PEDCHENKO T, et al. Regulation of macrophage cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression by modifications of histone H3 [J]. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 2004, 286(5): L956-L62.

- HARADA E, KATO S. Effect of short-chain fatty acids on the secretory response of the ovine exocrine pancreas [J]. Am J Physiol, 1983, 244(3): G284-G90.

- KATOH K, TSUDA T. Effects of secretagogues on membrane potential and input resistance of pancreatic acinar cells of sheep [J]. Res Vet Sci, 1985, 38(2): 250-1.

- KATOH K, TSUDA T. Effects of acetylcholine and short-chain fatty acids on acinar cells of the exocrine pancreas in sheep [J]. J Physiol, 1984, 356: 479-89.

- KATOH K, TSUDA T. Effects of intravenous injection of butyrate on the exocrine pancreatic secretion in guinea pigs [J]. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol, 1987, 87(3): 569-72.

- LU V B, GRIBBLE F M, REIMANN F. Free Fatty Acid Receptors in Enteroendocrine Cells [J]. Endocrinology, 2018, 159(7): 2826-35.

- TEYANI R, MONIRI N H. Gut feelings in the islets: The role of the gut microbiome and the FFA2 and FFA3 receptors for short chain fatty acids on β-cell function and metabolic regulation [J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2023, 180(24): 3113-29.

- ROSLI N S A, ABD GANI S, KHAYAT M E, et al. Short-chain fatty acids: possible regulators of insulin secretion [J]. Mol Cell Biochem, 2023, 478(3): 517-30.

- FROST F, WEISS F U, SENDLER M, et al. The Gut Microbiome in Patients With Chronic Pancreatitis Is Characterized by Significant Dysbiosis and Overgrowth by Opportunistic Pathogens [J]. Clin Transl Gastroenterol, 2020, 11(9): e00232. [CrossRef]

- JANDHYALA S M, MADHULIKA A, DEEPIKA G, et al. Altered intestinal microbiota in patients with chronic pancreatitis: implications in diabetes and metabolic abnormalities [J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7: 43640.

- MOENS F, VAN DEN ABBEELE P, BASIT A W, et al. A four-strain probiotic exerts positive immunomodulatory effects by enhancing colonic butyrate production in vitro [J]. Int J Pharm, 2019, 555.

- KOH A, DE VADDER F, KOVATCHEVA-DATCHARY P, et al. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites [J]. Cell, 2016, 165(6): 1332-45.

- LEBLANC J G, CHAIN F, MARTíN R, et al. Beneficial effects on host energy metabolism of short-chain fatty acids and vitamins produced by commensal and probiotic bacteria [J]. Microb Cell Fact, 2017, 16(1): 79.

- MEIMANDIPOUR A, HAIR-BEJO M, SHUHAIMI M, et al. Gastrointestinal tract morphological alteration by unpleasant physical treatment and modulating role of Lactobacillus in broilers [J]. Br Poult Sci, 2010, 51(1): 52-9.

- SIVIERI K, MORALES M L V, ADORNO M A T, et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus CRL 1014 improved "gut health" in the SHIME reactor [J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2013, 13: 100.

- AMARETTI A, BERNARDI T, TAMBURINI E, et al. Kinetics and metabolism of Bifidobacterium adolescentis MB 239 growing on glucose, galactose, lactose, and galactooligosaccharides [J]. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2007, 73(11): 3637-44.

- ABDIN A A, SAEID E M. An experimental study on ulcerative colitis as a potential target for probiotic therapy by Lactobacillus acidophilus with or without "olsalazine" [J]. J Crohns Colitis, 2008, 2(4): 296-303.

- SALAZAR N, BINETTI A, GUEIMONDE M, et al. Safety and intestinal microbiota modulation by the exopolysaccharide-producing strains Bifidobacterium animalis IPLA R1 and Bifidobacterium longum IPLA E44 orally administered to Wistar rats [J]. Int J Food Microbiol, 2011, 144(3): 342-51.

- BYRNE C S, CHAMBERS E S, MORRISON D J, et al. The role of short chain fatty acids in appetite regulation and energy homeostasis [J]. Int J Obes (Lond), 2015, 39(9): 1331-8.

- MORRISON D J, PRESTON T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism [J]. Gut Microbes, 2016, 7(3): 189-200.

- PASCALE N, GU F, LARSEN N, et al. The Potential of Pectins to Modulate the Human Gut Microbiota Evaluated by In Vitro Fermentation: A Systematic Review [J]. Nutrients, 2022, 14(17).

- MACFARLANE S, MACFARLANE G T. Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production [J]. Proc Nutr Soc, 2003, 62(1): 67-72.

- BOETS E, DEROOVER L, HOUBEN E, et al. Quantification of in Vivo Colonic Short Chain Fatty Acid Production from Inulin [J]. Nutrients, 2015, 7(11): 8916-29.

- FRANçOIS I E J A, LESCROART O, VERAVERBEKE W S, et al. Effects of a wheat bran extract containing arabinoxylan oligosaccharides on gastrointestinal health parameters in healthy adult human volunteers: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial [J]. Br J Nutr, 2012, 108(12): 2229-42.

- GUIMARãES J B, RODRIGUES V F, PEREIRA Í S, et al. Inulin prebiotic ameliorates type 1 diabetes dictating regulatory T cell homing via CCR4 to pancreatic islets and butyrogenic gut microbiota in murine model [J]. J Leukoc Biol, 2024, 115(3): 483-96.

- FALONY G, VLACHOU A, VERBRUGGHE K, et al. Cross-feeding between Bifidobacterium longum BB536 and acetate-converting, butyrate-producing colon bacteria during growth on oligofructose [J]. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2006, 72(12): 7835-41. [CrossRef]

- MOENS F, WECKX S, DE VUYST L. Bifidobacterial inulin-type fructan degradation capacity determines cross-feeding interactions between bifidobacteria and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii [J]. Int J Food Microbiol, 2016, 231: 76-85.

- DRUCKER D, J. Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Application of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 [J]. Cell Metab, 2018, 27(4): 740-56.

- MüLLER T D, FINAN B, BLOOM S R, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) [J]. Mol Metab, 2019, 30.

- NOGUEIRAS R, NAUCK M A, TSCHöP M H. Gut hormone co-agonists for the treatment of obesity: from bench to bedside [J]. Nat Metab, 2023, 5(6): 933-44.

- DRUCKER D J, HABENER J F, HOLST J J. Discovery, characterization, and clinical development of the glucagon-like peptides [J]. J Clin Invest, 2017, 127(12): 4217-27.

- RICHARDS P, PARKER H E, ADRIAENSSENS A E, et al. Identification and characterization of GLP-1 receptor-expressing cells using a new transgenic mouse model [J]. Diabetes, 2014, 63(4): 1224-33.

- MURARO M J, DHARMADHIKARI G, GRüN D, et al. A Single-Cell Transcriptome Atlas of the Human Pancreas [J]. Cell Syst, 2016, 3(4).

- SEGERSTOLPE Å, PALASANTZA A, ELIASSON P, et al. Single-Cell Transcriptome Profiling of Human Pancreatic Islets in Health and Type 2 Diabetes [J]. Cell Metab, 2016, 24(4): 593-607.

- WASER B, BLANK A, KARAMITOPOULOU E, et al. Glucagon-like-peptide-1 receptor expression in normal and diseased human thyroid and pancreas [J]. Mod Pathol, 2015, 28(3): 391-402.

- DE HEER J, RASMUSSEN C, COY D H, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1, but not glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide, inhibits glucagon secretion via somatostatin (receptor subtype 2) in the perfused rat pancreas [J]. Diabetologia, 2008, 51(12): 2263-70.

- CAMPBELL J E, DRUCKER D J. Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of incretin hormone action [J]. Cell Metab, 2013, 17(6): 819-37.

- YUSTA B, BAGGIO L L, ESTALL J L, et al. GLP-1 receptor activation improves beta cell function and survival following induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress [J]. Cell Metab, 2006, 4(5): 391-406.

- LAMONT B J, ANDRIKOPOULOS S. Hope and fear for new classes of type 2 diabetes drugs: is there preclinical evidence that incretin-based therapies alter pancreatic morphology? [J]. J Endocrinol, 2014, 221(1): T43-T61.

- RANKIN M M, KUSHNER J A. Adaptive beta-cell proliferation is severely restricted with advanced age [J]. Diabetes, 2009, 58(6): 1365-72.

- TSCHEN S-I, GEORGIA S, DHAWAN S, et al. Skp2 is required for incretin hormone-mediated β-cell proliferation [J]. Mol Endocrinol, 2011, 25(12): 2134-43.

- FIORENTINO T V, OWSTON M, ABRAHAMIAN G, et al. Chronic continuous exenatide infusion does not cause pancreatic inflammation and ductal hyperplasia in non-human primates [J]. Am J Pathol, 2015, 185(1): 139-50.

- HOU Y, ERNST S A, HEIDENREICH K, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor is present in pancreatic acinar cells and regulates amylase secretion through cAMP [J]. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2016, 310(1): G26-G33.

- PYKE C, HELLER R S, KIRK R K, et al. GLP-1 receptor localization in monkey and human tissue: novel distribution revealed with extensively validated monoclonal antibody [J]. Endocrinology, 2014, 155(4): 1280-90.

- KIRK R K, PYKE C, VON HERRATH M G, et al. Immunohistochemical assessment of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1R) expression in the pancreas of patients with type 2 diabetes [J]. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2017, 19(5): 705-12.

- KOEHLER J A, BAGGIO L L, LAMONT B J, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor activation modulates pancreatitis-associated gene expression but does not modify the susceptibility to experimental pancreatitis in mice [J]. Diabetes, 2009, 58(9): 2148-61.

- KOEHLER J A, BAGGIO L L, CAO X, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists increase pancreatic mass by induction of protein synthesis [J]. Diabetes, 2015, 64(3): 1046-56.

- STEINBERG W M, ROSENSTOCK J, WADDEN T A, et al. Erratum. Impact of Liraglutide on Amylase, Lipase, and Acute Pancreatitis in Participants With Overweight/Obesity and Normoglycemia, Prediabetes, or Type 2 Diabetes: Secondary Analyses of Pooled Data From the SCALE Clinical Development Program. Diabetes Care 2017;40:839-848 [J]. Diabetes Care, 2018, 41(7): 1538.

- KNAPEN L M, DE JONG R G P J, DRIESSEN J H M, et al. Use of incretin agents and risk of acute and chronic pancreatitis: A population-based cohort study [J]. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2017, 19(3): 401-11.

- JENSEN T M, SAHA K, STEINBERG W M. Erratum. Is There a Link Between Liraglutide and Pancreatitis? A Post Hoc Review of Pooled and Patient-Level Data From Completed Liraglutide Type 2 Diabetes Clinical Trials. Diabetes Care 2015;38:1058-1066 [J]. Diabetes Care, 2015, 38(8): 1622.

- NAKAMURA T, ITO T, UCHIDA M, et al. PSCs and GLP-1R: occurrence in normal pancreas, acute/chronic pancreatitis and effect of their activation by a GLP-1R agonist [J]. Lab Invest, 2014, 94(1): 63-78.

- YANG Y, YU X, HUANG L, et al. GLP-1R agonist may activate pancreatic stellate cells to induce rat pancreatic tissue lesion [J]. Pancreatology, 2013, 13(5): 498-501.

- ZENG Z, YU R, ZUO F, et al. Heterologous Expression and Delivery of Biologically Active Exendin-4 by Lactobacillus paracasei L14 [J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(10): e0165130.

- HEDIN K A, ZHANG H, KRUSE V, et al. Cold Exposure and Oral Delivery of GLP-1R Agonists by an Engineered Probiotic Yeast Strain Have Antiobesity Effects in Mice [J]. ACS Synth Biol, 2023, 12(11): 3433-42.

- WANG Q, GUO H, MAO W, et al. The Oral Delivery System of Modified GLP-1 by Probiotics for T2DM [J]. Pharmaceutics, 2023, 15(4).

- WANG X-L, CHEN W-J, JIN R, et al. Engineered probiotics Clostridium butyricum-pMTL007-GLP-1 improves blood pressure via producing GLP-1 and modulating gut microbiota in spontaneous hypertension rat models [J]. Microb Biotechnol, 2023, 16(4): 799-812. [CrossRef]

- WANG Y, SHI Y, PENG X, et al. Biochemotaxis-Oriented Engineering Bacteria Expressing GLP-1 Enhance Diabetes Therapy by Regulating the Balance of Immune [J]. Adv Healthc Mater, 2024, 13(11): e2303958.

- ZHOU J, MARTIN R J, TULLEY R T, et al. Dietary resistant starch upregulates total GLP-1 and PYY in a sustained day-long manner through fermentation in rodents [J]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2008, 295(5): E1160-E6.

- SHEN L, KEENAN M J, RAGGIO A, et al. Dietary-resistant starch improves maternal glycemic control in Goto-Kakizaki rat [J]. Mol Nutr Food Res, 2011, 55(10): 1499-508.

- HIRA T, SUTO R, KISHIMOTO Y, et al. Resistant maltodextrin or fructooligosaccharides promotes GLP-1 production in male rats fed a high-fat and high-sucrose diet, and partially reduces energy intake and adiposity [J]. Eur J Nutr, 2018, 57(3): 965-79.

- WONGKRASANT P, PONGKORPSAKOL P, CHITWATTANANONT S, et al. Fructo-oligosaccharides alleviate inflammation-associated apoptosis of GLP-1 secreting L cells via inhibition of iNOS and cleaved caspase-3 expression [J]. J Pharmacol Sci, 2020, 143(2): 65-73.

- PICHETTE J, FYNN-SACKEY N, GAGNON J. Hydrogen Sulfide and Sulfate Prebiotic Stimulates the Secretion of GLP-1 and Improves Glycemia in Male Mice [J]. Endocrinology, 2017, 158(10): 3416-25.

- LIU H, XING Y, WANG Y, et al. Dendrobium officinale Polysaccharide Prevents Diabetes via the Regulation of Gut Microbiota in Prediabetic Mice [J]. Foods, 2023, 12(12).

- WANG G, LI X, ZHAO J, et al. Lactobacillus casei CCFM419 attenuates type 2 diabetes via a gut microbiota dependent mechanism [J]. Food Funct, 2017, 8(9): 3155-64.

- BALAKUMAR M, PRABHU D, SATHISHKUMAR C, et al. Improvement in glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity by probiotic strains of Indian gut origin in high-fat diet-fed C57BL/6J mice [J]. Eur J Nutr, 2018, 57(1): 279-95.

- WANG Y, WANG X, XIAO X, et al. A Single Strain of Lactobacillus (CGMCC 21661) Exhibits Stable Glucose- and Lipid-Lowering Effects by Regulating Gut Microbiota [J]. Nutrients, 2023, 15(3).

- SINGH S, SHARMA R K, MALHOTRA S, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus NCDC17 ameliorates type-2 diabetes by improving gut function, oxidative stress and inflammation in high-fat-diet fed and streptozotocintreated rats [J]. Benef Microbes, 2017, 8(2): 243-55.

- SU Y, REN J, ZHANG J, et al. Lactobacillus paracasei JY062 Alleviates Glucolipid Metabolism Disorders via the Adipoinsular Axis and Gut Microbiota [J]. Nutrients, 2024, 16(2).

- YUE Z, ZHAO F, GUO Y, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri JCM 1112 ameliorates chronic acrylamide-induced glucose metabolism disorder via the bile acid-TGR5-GLP-1 axis and modulates intestinal oxidative stress in mice [J]. Food Funct, 2024, 15(12): 6450-8.

- SIMON M-C, STRASSBURGER K, NOWOTNY B, et al. Intake of Lactobacillus reuteri improves incretin and insulin secretion in glucose-tolerant humans: a proof of concept [J]. Diabetes Care, 2015, 38(10): 1827-34.

- BJERG A T, KRISTENSEN M, RITZ C, et al. Lactobacillus paracasei subsp paracasei L. casei W8 suppresses energy intake acutely [J]. Appetite, 2014, 82: 111-8.

- CHENG Z, CHEN J, ZHANG Y, et al. In Vitro Hypoglycemic Activities of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacterium Strains from Healthy Children's Sources and Their Effect on Stimulating GLP-1 Secretion in STC-1 Cells [J]. Foods, 2024, 13(4). [CrossRef]

- ZHAO D, ZHU H, GAO F, et al. Antidiabetic effects of selenium-enriched Bifidobacterium longum DD98 in type 2 diabetes model of mice [J]. Food Funct, 2020, 11(7): 6528-41.

- ZHANG C, FANG B, ZHANG N, et al. The Effect of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis MN-Gup on Glucose Metabolism, Gut Microbiota, and Their Metabolites in Type 2 Diabetic Mice [J]. Nutrients, 2024, 16(11).

- DONG Y, QI Y, CHEN J, et al. Neuroprotective Effects of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis NJ241 in a Mouse Model of Parkinson's Disease: Implications for Gut Microbiota and PGC-1α [J]. Mol Neurobiol, 2024.

- AOKI R, KAMIKADO K, SUDA W, et al. A proliferative probiotic Bifidobacterium strain in the gut ameliorates progression of metabolic disorders via microbiota modulation and acetate elevation [J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7: 43522.

- NIU H, ZHOU M, JI A, et al. Molecular Mechanism of Pasteurized Akkermansia muciniphila in Alleviating Type 2 Diabetes Symptoms [J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2024, 72(23): 13083-98.

- SANGINETO M, GRANDER C, GRABHERR F, et al. Recovery of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron ameliorates hepatic steatosis in experimental alcohol-related liver disease [J]. Gut Microbes, 2022, 14(1): 2089006.

- KIM J E, LEE J Y, KANG C-H. Limosilactobacillus fermentum MG4295 Improves Hyperglycemia in High-Fat Diet-Induced Mice [J]. Foods, 2022, 11(2).

- SUN J, WANG F, HU X, et al. Clostridium butyricum Attenuates Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress-Induced Depressive-Like Behavior in Mice via the Gut-Brain Axis [J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2018, 66(31): 8415-21.

- JIA L, LI D, FENG N, et al. Anti-diabetic Effects of Clostridium butyricum CGMCC0313.1 through Promoting the Growth of Gut Butyrate-producing Bacteria in Type 2 Diabetic Mice [J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7(1): 7046. [CrossRef]

| Probiotics | Products | References |

|---|---|---|

| Bifidobacterium spp. | acetate, butyrate | [55] |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | propionate | [56] |

| Lactobacillus gasseri PA 16/8 | ||

| Bifidobacterium longum SP 07/3 | acetate, propionate | |

| Bifidobacterium bifidum MF 20/5 | ||

| Lactobacillus salivarius spp salcinius JCM 1230 | propionate, butyrate | [57] |

| Lactobacillus agilis JCM 1048 | ||

| Lactobacillus acidophilus CRL 1014 | acetate, propionate, butyrate | [58,59,60,61] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).