1. Introduction

Vestibular Neuritis (VN) is the main cause which induces Acute Vestibular Syndrome (AVS). It causes long-lasting, continuous, and spontaneous vertigo. It is assumed to be of viral origin [

1], in relation with possible reactivation of latent herpes virus simplex type 1. The main alternative cause is vascular ischemic origin. This is a theory based on the recurrent finding that vascular risk factors are more prominent in these patients [

2]. The viral hypothesis is supported by the fact that there is radiological evidence of inflammation in the acute phase of VN [

3,

4,

5,

6].

The acute symptom onset may in some circumstances make it difficult to distinguish VN from gastroenteritis, as neurovegetative symptoms are sometimes dominant. Thus, it must be differentiated from ischemic stroke [

7] in the territory of the superior cerebellar artery [

8]. The diagnosis of VN should be based on clinical history and physical examination, following the Head Impulse-Nystagmus-Test Skew (HINTS) protocol [

9] for distinguish central from peripheral syndromes. Even a lateral canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) can must be considered in the differential diagnosis, and it can be separated from VN by the Bow and Lean test [

10].

The lateral and anterior semicircular canals (SCCs) are most affected in VN (Superior VN). In some cases, there can be simultaneous involvement of all three SCCs on one side (Total VN) [

11]. However, in a minority of patients, a selective involvement of the posterior SCC takes place (Inferior VN) [

12]. Although a major vestibular dysfunction in VN is expected, recent studies report some cases with a final diagnosis of possible VN with mild or no objective deficit in vestibular function [

13], or selective impairment of the lateral SCC related to a partial localized labyrinthine damage [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Several recent papers have been published reporting the presence of normal caloric stimulation in the context of a VN [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] suggesting possible isolated “otolithic” forms of VN.

It is well known that after VN, the ipsilateral Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex (VOR) and its pathway are affected. This is documented by head shaking test (HST), bithermal caloric testing (BCT), rotatory testing, Video Head Impulse Test (VHIT), or Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials (VEMPs). More recently the Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus (SVIN), which analyses very high frequencies and constitutes a first line bedside global vestibular test exploring type I inner ear hair cells, shows an inhibitory nystagmus (Ny) in VN [

22,

23].

A vestibular lesion induces changes in the gain and time constant of the VOR pathway [

24]. The gain of the VOR is a sign of the intensity of vestibular response and, therefore, the vestibular compensation process. Some restoration and adaptation changes are usually described in these patients, a finding usually interpreted as a “compensatory mechanism” [

25].

Patients who suffer from VN tend to develop a persistent long-term disability in their daily activities. Some clinical variables such as the initial vestibular deficit, an enhanced visual dependency, or the level of anxiety may, to some level, predict outcomes in VN patients [

26]. Although previous evidence reported that neither caloric paresis nor VOR gain of VHIT predicted symptom course in VN [

27], other authors suggest that saccadic organization seems to participate in visual target retention and ocular compensation during head impulses in VHIT studies [

28,

29]. So far, measures of residual peripheral vestibular function are a poor measure of functional subjective outcome in VN [

30].

The aim of this study was to identify, in patients affected by VN, predictive factors of VN evolution:

(A) analysing and determining possible risk factors of the disease;

(B) evaluating the compensatory process through the changes in the perceived disability and in vestibular testing, from the onset of symptoms (T0) to 90±15 days after (T3);

(C) using these results to improve further the therapeutic management of VN.

Targeted care is extremely important for patients at risk of developing chronic unsteadiness, due to ineffective compensation, as chronic instability can have repercussions on many levels:

(1) emotional: because poor compensation can generate insecurity, emotional tensions and panic which intensify symptoms in a positive feedback loop;

(2) social: related to fear of leaving home and disrupting relationships with other people;

(3) professional: because it prevents the normal performance of daily work-related and recreational activities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

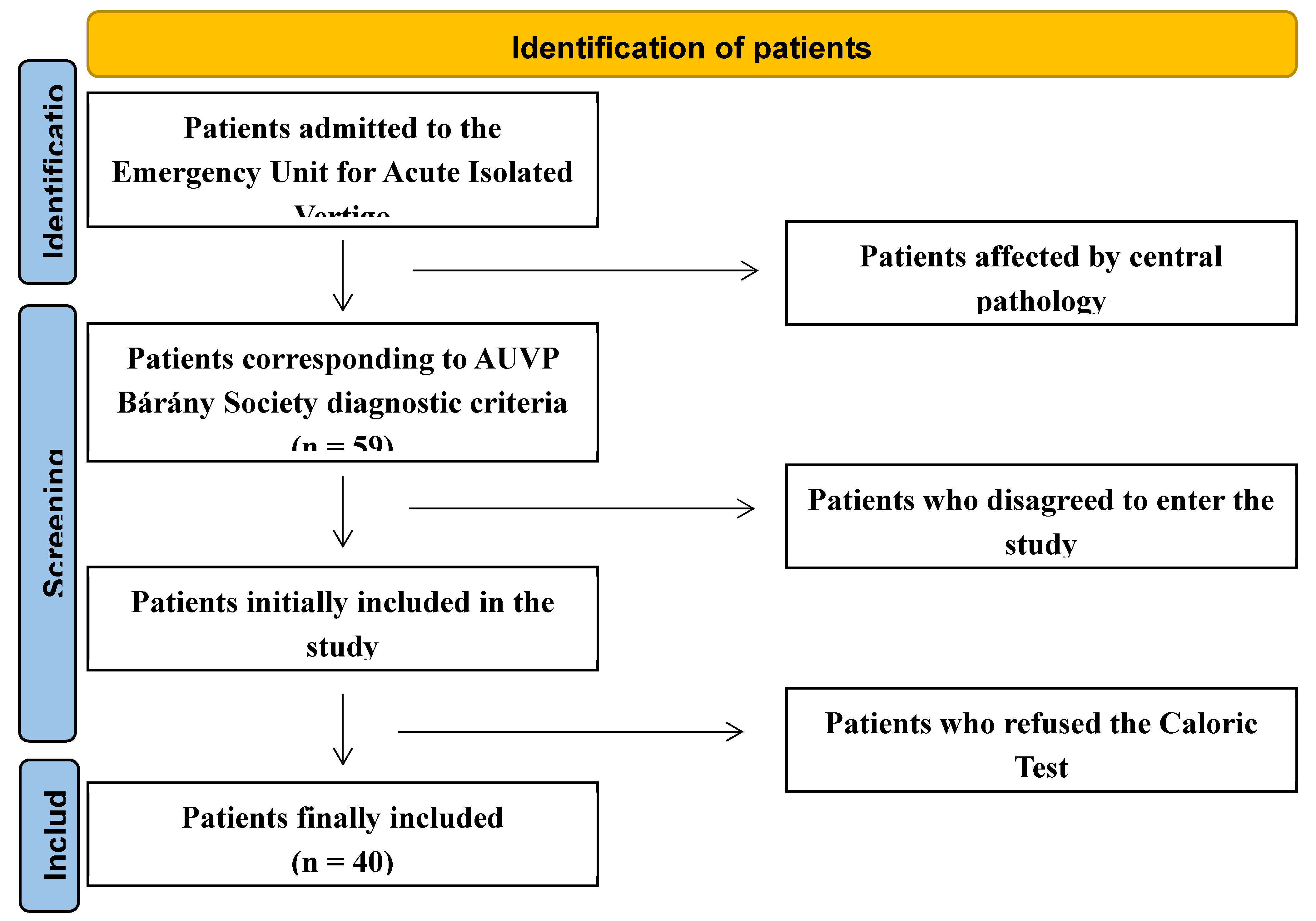

In this longitudinal and prospective study, 72 patients admitted to the Emergency Unit from November 2020 to October 2023 due to AVS were referred to the Department of Otorhinolaryngology in the Hospital of Mirano (Venice), Italy. Thirteen patients had documented central pathology confirmed on brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). The remaining 59 were diagnosed with VN. Seven patients did not consent to be included in the study; 12 patients did not consent to undergo caloric tests. The remaining 40 patients formed the basis of the study (

Figure 1).

Each patient was assigned a numeric ID and age, gender, and BMI were collected. Complete anamnesis, as well as neurotological and neurological examinations, were performed in all patients.

Once diagnosed with a peripheral lesion, all patients were encouraged to mobilization as early as possible to achieve a quick return to their daily activity. All patients were advised to perform active dynamic movement protocols at home, several times a day for at least a month.

The

inclusion criteria for VN, i.e. Acute Unilateral Vestibulopathy (AUVP), were the diagnostic criteria established from Bárány Society [

31]:

(1) acute or subacute onset of sustained spinning or non-spinning vertigo (i.e. an acute vestibular syndrome) of moderate to severe intensity with symptoms lasting for at least 24 hours;

(2) spontaneous peripheral vestibular nystagmus, i.e. nystagmus with a direction appropriate to the SCC afferents involved, usually horizontal-torsional, direction fixed, and enhanced by removal of visual fixation;

(3) definitive evidence of reduced VOR function on the side opposite the direction of the fast phase of the spontaneous nystagmus;

(4) no evidence of acute central neurological symptoms or acute audiological symptoms such as hearing loss or tinnitus or other otologic symptoms such as otalgia;

(5) no acute central neurological signs, i.e. no central ocular motor or central vestibular signs; particularly no skew deviation, no gaze-evoked nystagmus, and no acute audiological signs;

(6) not better accounted for by another disease or disorder.

The non-inclusion criteria concerning our study were:

(1) history of vestibular or neurotologic disorders;

(2) history of otologic disorders or surgery;

(3) symptoms leading to doubt about the initial Menière's attack or the first recurrent attack of vertigo;

(4) medical condition or malignancy that can cause immunocompromised status;

(5) regular intake of psychotropic drugs;

(6) MRI that revealed acute infarction or other acute/chronic brain lesions, including cerebellopontine angle tumours.

Patients received follow-up assessment three months after the onset of vertigo. All tests necessary to evaluate vestibular impairment and the process of recovery via healing or via compensation, were performed from the initial assessment until the end of the follow-up.

All the patients underwent routinely performed tests only, without invasive or experimental procedures. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of dell’AULSS 3 Serenissima Regione Veneto, Mirano -Venezia-, Italy (protocol code 157A/CESC, December 22nd, 2020). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Bedside Vestibular Testing

The bedside examination was performed at hospital admission. All the patients were treated during the acute phase with tapered doses of glucocorticoid (methylprednisolone starting from 32 mg daily) and antiemetic drugs. The differential diagnosis between peripheral and central vertigo episodes, in the Neurotology Department of the author, was performed clinically by using the HINTS plus [

32], along with the watchful monitoring of the symptomatology, with particular attention devoted to the severity of imbalance and the duration of acute vertigo. To rule out central lesions, patients who clinically mimicked a peripheral AVS syndrome also underwent cerebral MRI.

At the time of the first observation, all patients underwent a medical history. The anamnesis was general and specific for cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs), i.e. obesity, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, hypercholesterolemia. Eye movements evaluation, performed under Videonystagmography (VNG), was related to spontaneous Nystagmus and Nystagmus evoked by head shaking. Bedside exam was repeated 90±15 days after the first observation. We deliberately chose a “short term follow-up” to understand the recovery dynamics shortly after the appearance of NV.

2.2.2. Instrumental Vestibular Testing

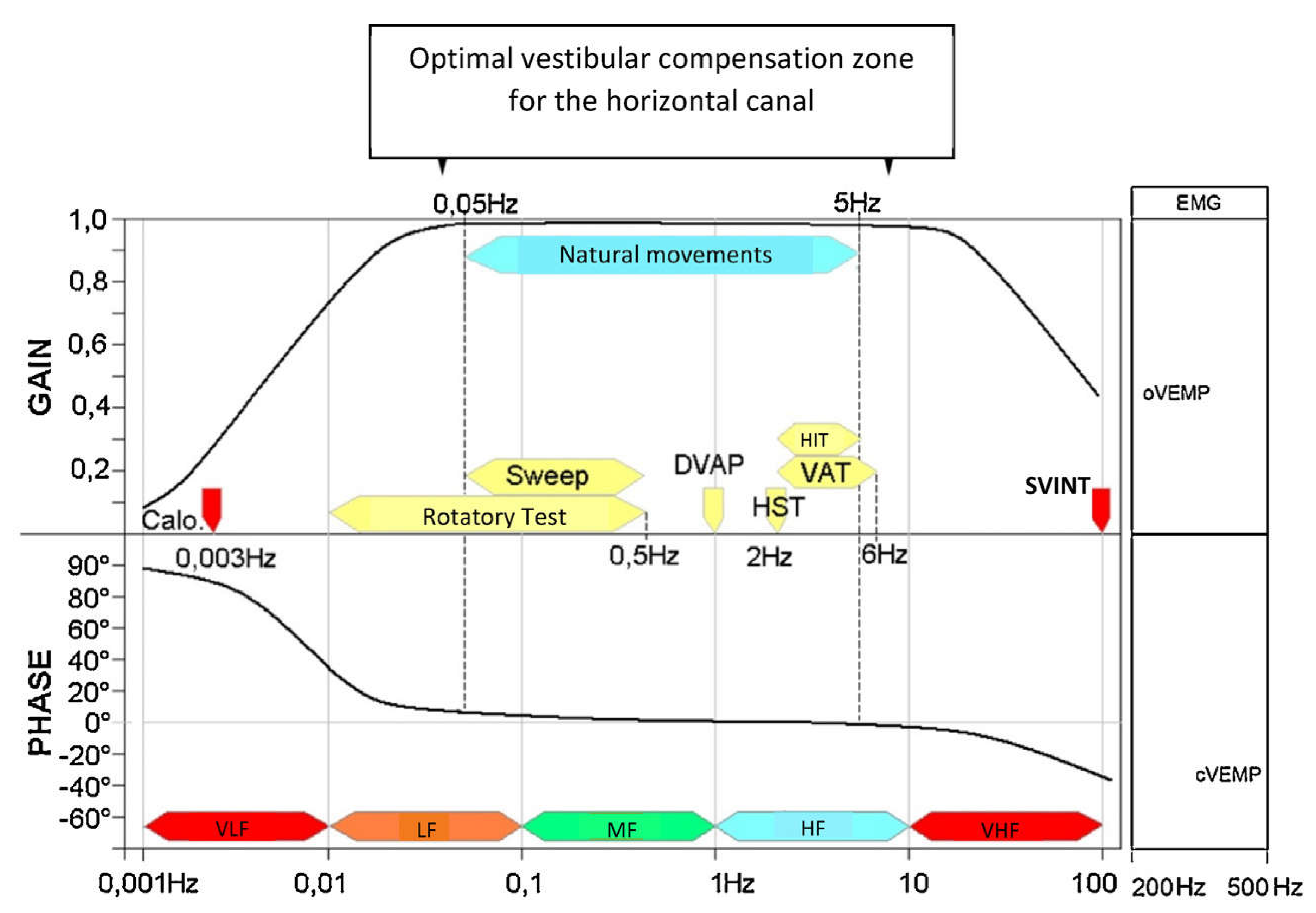

The vestibular instrumental examination was performed within 36-72 hours from the onset of the symptomatology and was repeated 90±15 days after the first observation. The vestibular system was evaluated at specific response frequencies based on different available diagnostic test, since receptors are frequency specific. [33,34]. Type II vestibular receptors or tonic cells have a regular firing rate in static conditions which is modulated by very low and low frequency head movement and assessed by BCT. Type I vestibular receptors (phasic cells) with irregular firing rate neurons are activated by high-frequency head movements and assessed by VHIT and SVINT.

(1) Very low vestibular frequencies were evaluated by conventional Fitzgerald-Hallpike protocol (volume: 250 ml; duration: 40 sec.; temperatures: 30°C and 44°C). A video-based system (Ulmer VNG 2D, ver. C4, Synapsys®, Marseille, France) was used for the acquisition and analysis of the eye movements. We measured the maximum slow phase velocity (SPV) of the of evoked nystagmus for the four irrigations and used the Phillipszoon-Jongkees formula to calculate unilateral weakness and directional preponderance. A unilateral canal paresis (CP) exceeding 20% indicated vestibular hypofunction [

35].

(2) High vestibular frequencies were evaluated by the VHIT. We used a VHIT Remote Camera System, (Inventis®, Italy). The patient was asked to stare at an earth-fixed target (1.5cm-diameter spot located 1.5m in front), according to HIMP procedure; then, 20 low-amplitude (10-15°) high- velocity head impulses (200-250°/sec. horizontal plane; 150-200°/sec. vertical planes) were randomly administered on each side for all SCCs. The software automatically calculated the average high- velocity VOR gain and the Asymmetry Index (AI) expressed as a percent. (not presented in this study). Normal values are within 15% between right and left sides. This value resulted from our own data collected on a group of 50 normal subjects age ranging 20 to 80. AI was calculated as GA = (GL−GR)/(GL+GR) × 100, where GA is gain asymmetry, GR is right sided mean gain and GL is left sided mean gain [

36]. The AI reveals differences between the sides in terms of high-velocity VOR [

37]. We did not report the AI measurements obtained with vertical plane stimulation, as in our experience there is a high level of artifact [

38]. Both covert (early) and overt (late) corrective saccades (CS) and the organization of their latencies, in terms of isochrony (gathered) and heterochrony (scattered) were taken into consideration [

39]. Both the CS and VHIT gain detect vestibular hypofunction [

31].

(3) Very high vestibular frequencies were evaluated by the SVINT or Dumas’ Test. VVIB 100 Hz vibrator (Synapsys®, Marseille, France) was applied during 5 to 10 sec. on the right/left mastoid and vertex site; the oculomotor response was recorded via VNG 2D (Synapsys®, Marseille, France). The test was considered negative if there was an absence of Ny, a SPV lower than 2.5°/sec. or a lack of concordance of the direction of Ny on the two mastoids [

40,

41].

Measuring vestibular alterations in VN usually requires separate explorations of SCCs or the otoliths but it has recently been shown that SVINT provides a more global vestibular test, as it assesses the SCCs but also the utricle. The horizontal component of the SVINT is capable of measuring both lateral SCC and utricular responses [

41,

42,

43] (

Figure 2).

2.2.3. Questionnaires

The questionnaire was the validated Italian version of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) [

48,

49]. It was performed at hospital admission and repeated 90±15 days after the first observation. Other questionnaires as Motion Sickness Susceptibility [

50] and Visual Vestibular Mismatch [

51] were also performed in same time but are not presented in this present study.

The DHI is a patient-reported outcome measure designed to measure the disability perceived by someone with complaints of dizziness, vertigo, or unsteadiness. The total score documents changes related to functional, emotional, and physical domains [

48].

In the literature there is no common criterion on the severity scale of the DHI. Many authors adopt the following: (a) mild handicap; score of 0-30; (b) moderate handicap; score of 31-60; (c) severe handicap; score of 61-100 [

48,

49,

50,

51]. Another method of reporting is the following: (a) asymptomatic, fully recovered (DHI= 0); (b) low symptoms (DHI 2-28); (c) high symptoms (DHI 36-80) [

52]. We followed the suggestion in the literature and established an arbitrary criterion of 32 points in the DHI to determine the state of general vestibular compensation of the patients. Those with a DHI total score < 32 were reported as “compensated” and those with a DHI total score ≥ 32 were reported as “non-compensated” [

53].

2.3. Clinical course of Vestibular Neuritis

The clinical course of VN can be:

(1) Healing: complete recovery of functional activity of the labyrinth sometimes occurs, due to resolution of the lesion and restoration of normal vestibular function through healing or cellular regeneration and disappearance of oedema [

54].

(2) Compensation: there is sometimes incomplete recovery of the functional activity of the labyrinth. In this case a process of recalibration of the activity of the vestibular nuclei must take place. This is enabled by a high degree of plasticity and occurs in the central nervous system in response to the sensory deficit [

55,

56]. The goal of the compensation process is to re-establish symmetrical neuronal activity at the level of the vestibular nuclei [

57].

To evaluate the compensation status of our patients, we utilized the work of Guajardo-Vergara et al. [

53] who refined the ideas of Eisenman et al. [

58]. There are slight differences in the cut-off values of objective tests and proposal of subjective scales. (For more details see: 4.1. Summary about vestibular compensation criteria in the literature).

One concern we had was that the proposed classification from Guajardo-Vergara et al. does not take into account the situation of patients with normalized vestibular assessments, but who have still persistent dizzy symptoms as evaluated by the Perez-Rey (PR) index. Patients with persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD) [

59] fall into in this category, which we propose to deal with as follows:

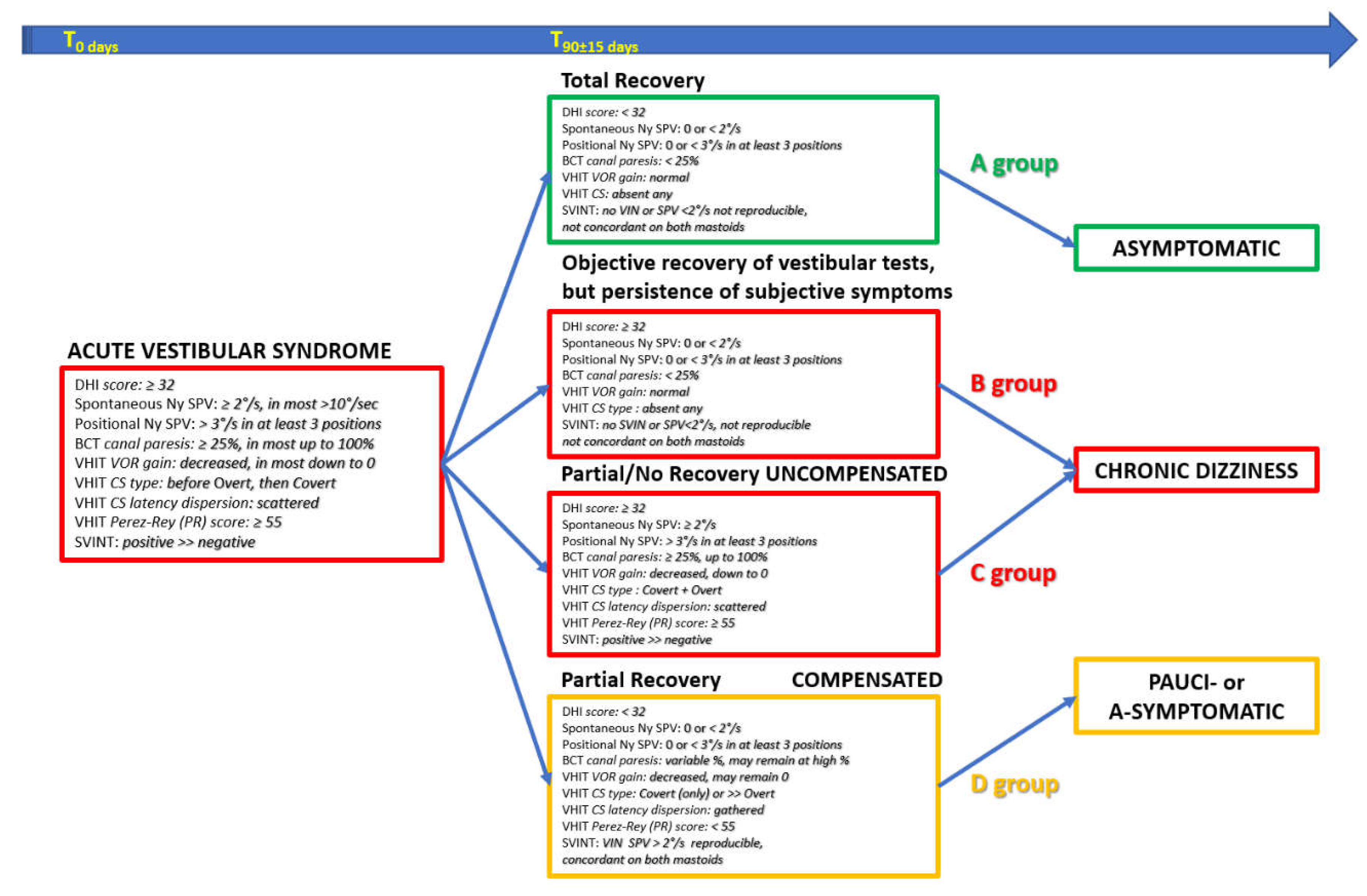

We utilized bedside and instrumental test results (measuring objective recovery and objective compensation) and combined them with DHI total score (measuring subjective symptoms) to define four groups of patients (Table 1):

The evolution via healing is a total recovery requiring a normalization of all clinical-instrumental tests but can be associated with different DHI total score.

(1) [A group]: DHI score < 32: a complete recovery as measured by objective tests and no subjective symptoms.

(2) [B Group]: DHI total score ≥ 32: a complete recovery as measured by objective tests, with some persistent subjective symptoms.

The evolution via compensation in patients with persisting abnormal vestibular objective tests must be divided two subgroups, depending on whether compensation has been ineffective (“uncompensated”) or effective (“well compensated”).

(3) [C group]: in the uncompensated group, the objective compensation criteria [

53] are not met and are associated with subjective symptoms, i.e. a DHI total score ≥ 32.

(4) [D group]: in the compensated group; the objective compensation criteria [

53] are met and are not associated with subjective symptoms, i.e. a DHI total score < 32.

2.4. Patient categories according to clinical and vestibular results

First, we examined the group of 40-patients. Then, we created a first partition based on the DHI score, allowing the creation of two group pairs, i.e. DHI < 32 (A+D group) vs DHI ≥ 32 (B+C group). A second partition was created based on patients’ objective status, allowing the creation of two further group pairs, i.e. with normal instrumental tests (A+B group) vs patients with pathological vestibular examinations (C+D group) [For more references, paragraph 3.3.2. Results by comparison of the four couples of groups].

2.5. Statistical analysis.

The factors examined were age, gender, BMI, CVRFs (arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia), results of DHI, BCT, VHIT and SVINT.

All statistical analyses were performed using the Jamovi software v2.3.28 (Jamovi project (2022)). Age, gender, and BMI were analysed between A+D group and B+C group, as well as for A+B group and C+D group. We also performed a binomial logistic regression to identify the best contribution of each feature. We also looked at differences between T0 and T3 between the A+D group and the B+C group, as well as for the A+B group and the C+D group.

Categorical variable (gender) was compared using a Fisher exact test for the A+D group and the B+C group, and for the A+B group and the C+D group. For continuous variables (BMI and age), normal distribution was verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variances was verified with Levene's test. Both conditions were met, and we performed a Student's t-test. In each case, our hypothesis was that both groups were different.

We also carried out a binomial stepwise backward logistic regression analysis to determine the optimal combination of features that separates the two groups i.e. between patients with no symptom and patients with symptoms, or between patients with normal test results and patients with abnormal results. Hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, and physiotherapy treatment were used as input variables. BMI was used has a covariable. The variance indication factor (VIF) is a measure of the amount of multicollinearity in a set of multiple regression variables. A high VIF indicates that the variable is redundant or strongly related to other predictors. A combination of variables was chosen to yield the highest sensitivity and specificity. The outcome of the best classification matrix (i.e. with the highest sensitivity and specificity) should be equal to 1. A binomial logistic regression was performed to assess the influence of each parameter in the different groups (i.e. which parameters were contributing maximally). A sensitivity and specificity of 100% would be expected for a combination of features predicting a perfect classification.

A normal distribution was also verified for BCT, VHIT and SVINT data using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variances was verified with Levene's test. When both conditions were met, parametric tests were performed. In the case of non-compliance with the homogeneity of variances, a Welch's t-test was conducted. In the case of non-compliance with the normality of the distribution, non-parametric tests were used. For groups comparisons (A+D vs B+C or A+B vs C+D at T0 or T3), tests for independent samples were implemented (Student's t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test). For a before-and-after comparisons within the same group (A+D between T0 and T3, likewise for A+B, B+C, and C+D), paired samples tests were performed (Mann-Whitney U test or Welch's t-test). In each case, the hypothesis was that one group would be superior to another and not just different.

For all statistical analysis, level of significance was set at p = 0.05. Significance was expressed as follows *= p <0.05; **=p <0.01; ***= p <0.001; NS = p >0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and clinical features

The sample consisted of 40 patients, 21 (52.5%) male and 19 (47.5%) female, with an M/F ratio=1.10/1. The age was 55.91±13.9 and the BMI was 25.71±3.54 (normal values: 18.5÷25). The time between the onset of symptoms and the first evaluation was 3.25±1.62 days. The time interval between the first and second clinical-instrumental evaluation and the questionnaires was 96.65±6.61 days. The side affected by the VN was the right in 25 patients (62.5%) and the left in 15 patients (37.5%). At the onset of VN, 16 patients (40%) had affected by arterial hypertension treated by regular therapy, 6 patients (15%) had diabetes mellitus, 14 patients (35%) had hypercholesterolemia; and 8 patients (20%) were smokers. Nineteen patients (47.5%) did not perform the proposed vestibular rehabilitation exercises after diagnosis.

3.2. Definition of patient groups

Four groups were finalized and defined following clinical and vestibular exploration results (

Table 1).

3.3. Results for considered parameters and groups

3.3.1. Results for the 40-patient group

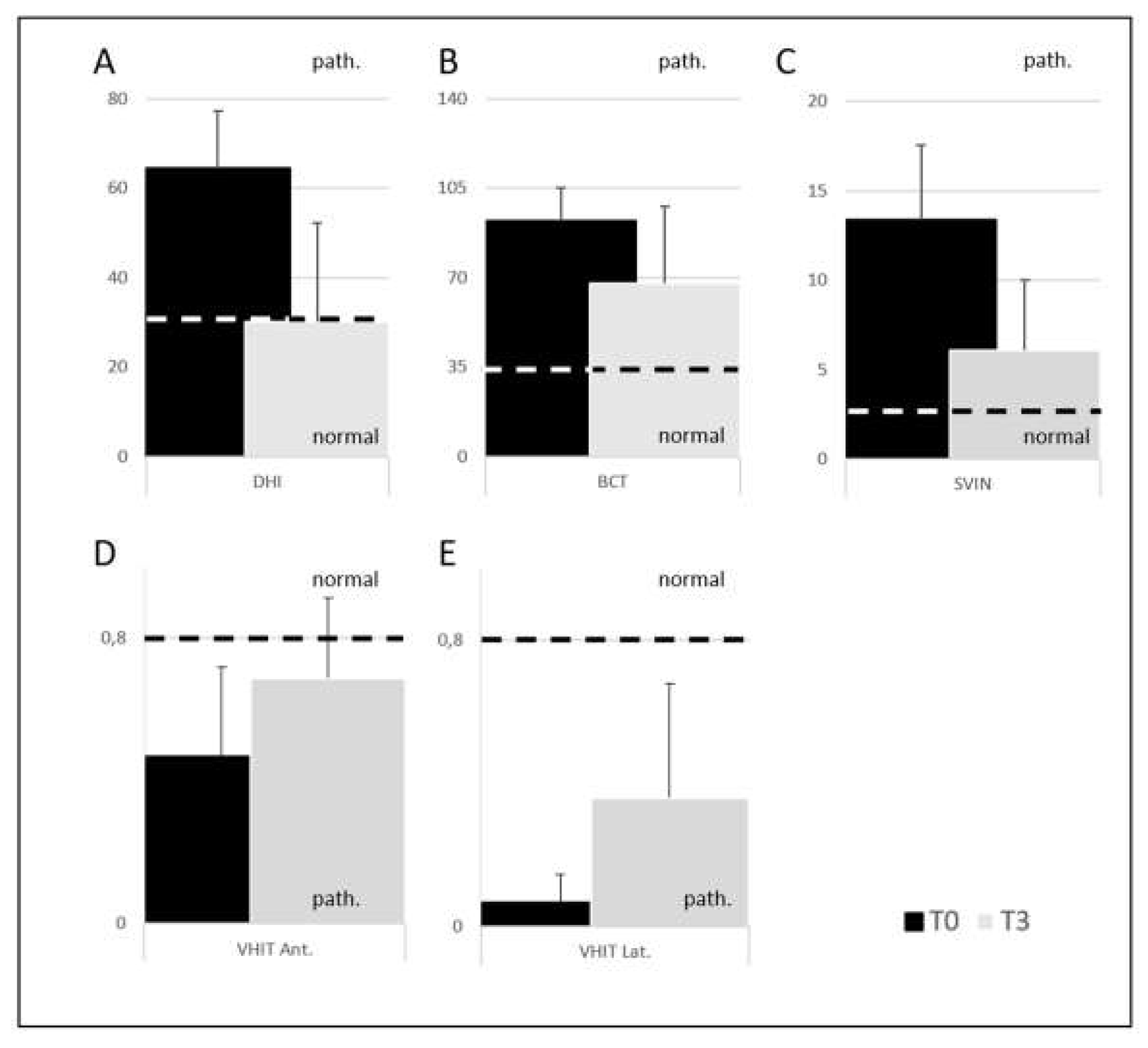

• The 40-patient group comes from the sum of A+B+C+D groups. By comparing the percentage of recovery between T0 and T3 for questionnaire and instrumental tests we found the following percentages: DHI 27.5%, BCT 20%, VHIT lateral SCC 20%, VHIT anterior SCC 55%, SVINT 26% (

Figure 3).

3.3.2. Results by comparison of the four couples of groups

• Age, Gender, BMI A+D group vs B+C group (DHI < 32 vs DHI ≥ 32)

No differences between the two couples of groups. These parameters do not contribute to distinguish groups of patients who complain or not of subjective symptoms (

Table 2).

• Age, Gender, BMI A+B group vs C+D group (normal Exams vs pathological Exams)

No differences between the two couple of groups have been observed. These parameters do not contribute to distinguish groups of patients who regularize or not their objective vestibular tests (

Table 2).

• Cardiovascular risk factors A+D group vs B+C group (DHI < 32 vs DHI ≥ 32)

Logistic regression analysis defined diabetes and hypercholesterolemia as indicators for less recovery with an 54.5% sensitivity and a 96.6% specificity from the classification matrix. VIF were equal to 1.02 for diabetes and hypercholesterolemia.

• Cardiovascular risk factors A+B group vs C+D group (normal Exams vs pathological Exams)

Logistic regression analysis defined hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia as indicators with an 96.9% sensitivity and a 62.5% specificity from the classification matrix. The recovery of vestibular objective function (vestibular tests) is less favourable for patients with a hypercholesterolemia. VIF were equal to 1.69 for diabetes and hypertension, and equal to 1.01 for hypercholesterolemia.

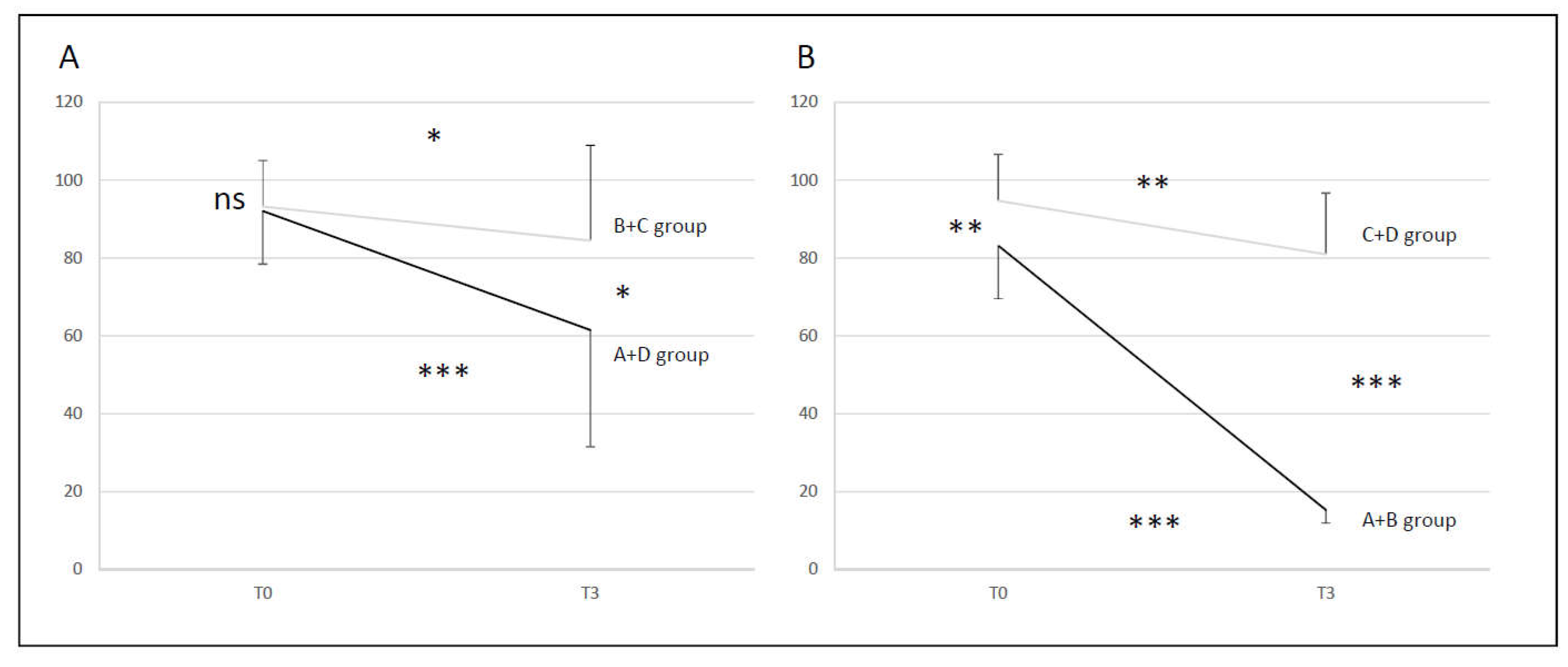

• BCT A+D group vs B+C group (DHI < 32 vs DHI ≥ 32)

At T0 there was no difference between the two couple of groups (NS), but there was at T3 (p < 0.05). The recovery of group B+C was not significant (p <0.05). Conversely, there was a significant recovery for A+D group (p < 0.001) however the recovery was still partial, incomplete with no complete return to normal. At T3 24% of the initial T0 abnormal values recovered normal function in the A+D group and 9% for B+C group (

Figure 4, A).

• BCT A+B group vs C+D group (normal Exams vs pathological Exams)

Groups were different at T0 (p < 0.01). Groups were more different at T3 (p < 0.001) as the recovery of A+B group is significantly higher than for C+D group. The recovery of A+B group was significant (p < 0.001) with a return to the normal. On the contrary, there was a significant recovery for C+D group (p < 0.01) with no complete return to the normal. At T3 100% of the initial T0 abnormal values recovered normal function in the A+B group and 0% in the C+D group (

Figure 4, B).

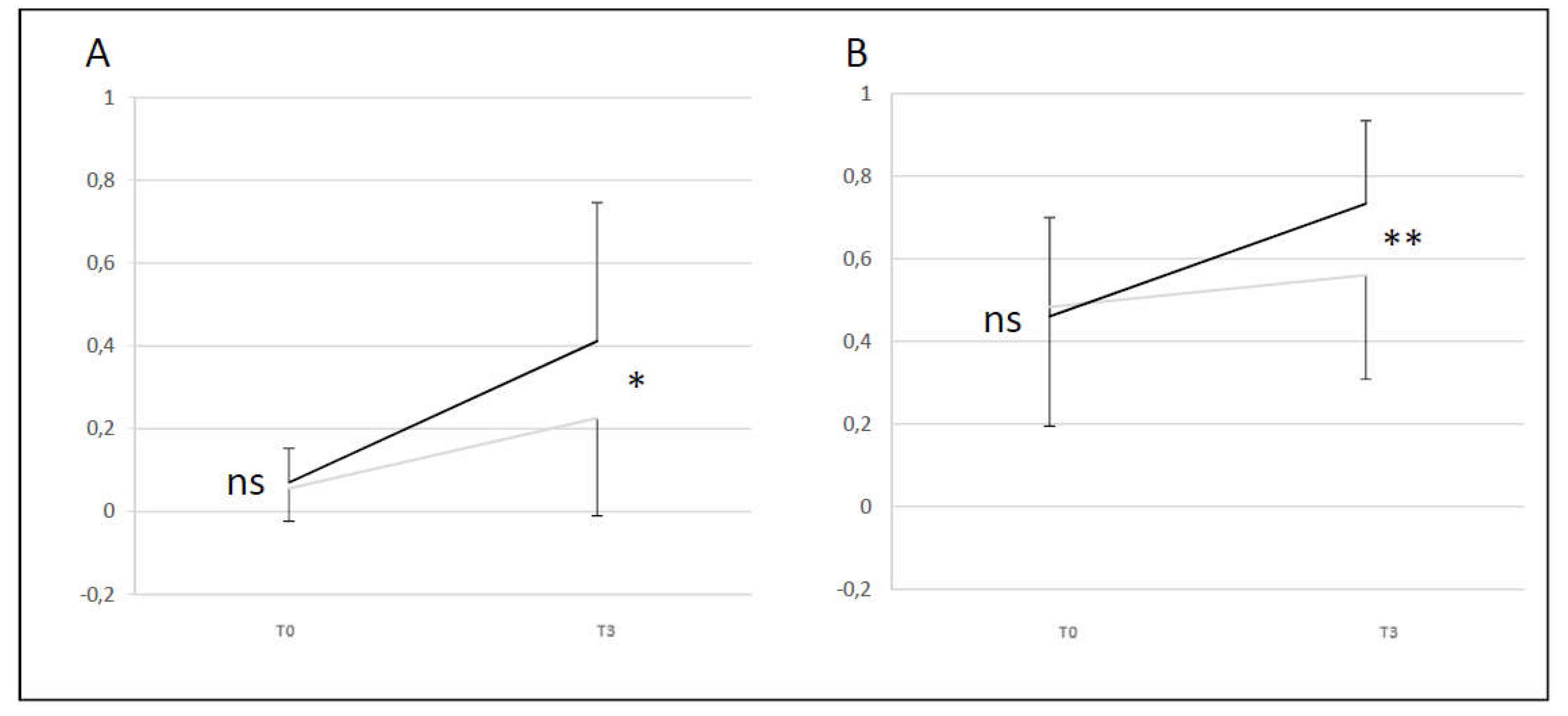

• VHIT A+D group vs B+C group (DHI < 32 vs DHI ≥3 2)

A+D group showed a difference compared to B+C group (difference T0 and T3) for lateral and anterior SCC (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01). A+D group had a better evolution of the VHIT gain level than B+C group between T0 and T3 for lateral and anterior SCC. For lateral SCC at T3 24% of the initial T0 abnormal values recovered normal function for A+D group and 9% for B+C group. For anterior SCC at T3 59% of the initial T0 abnormal values recovered normal function for A+D group and 36% for B+C group (

Figure 5).

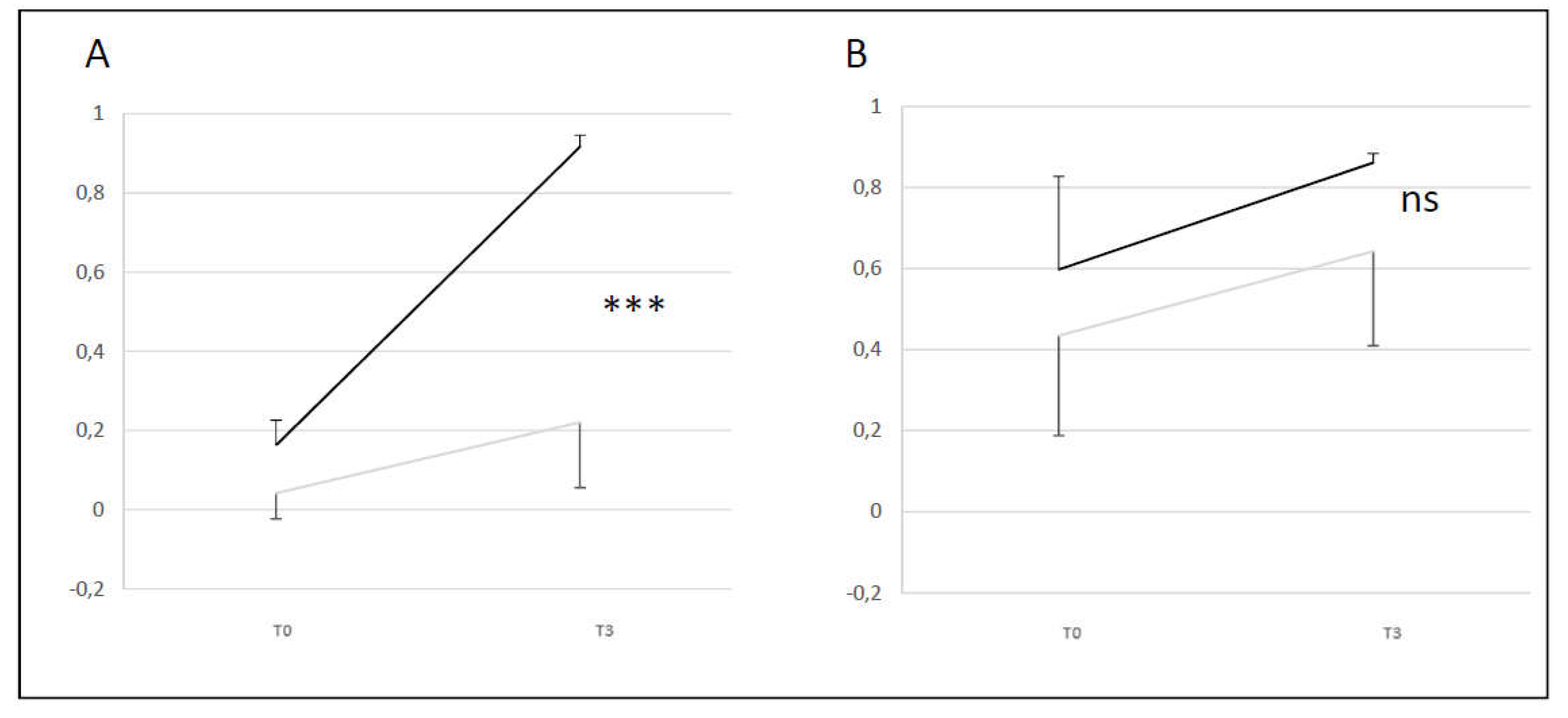

• VHIT A+B group vs C+D group (normal Exams vs pathological Exams)

A+B group showed a difference compared to C+D group (difference T0 and T3) only for the lateral SCC (p <0.001). These results showed that A+B group has a better change in level than C+D group between T0 and T3 for the lateral SCC. There was no change in A+B and C+D group for the anterior canal. For lateral SCC at T3 100% of the initial T0 abnormal values recover normal function for A+B group and 0% for C+D group. For anterior SCC at T3 100% of the initial T0 abnormal values recovered normal function for A+B group and 44% for C+D group (

Figure 6).

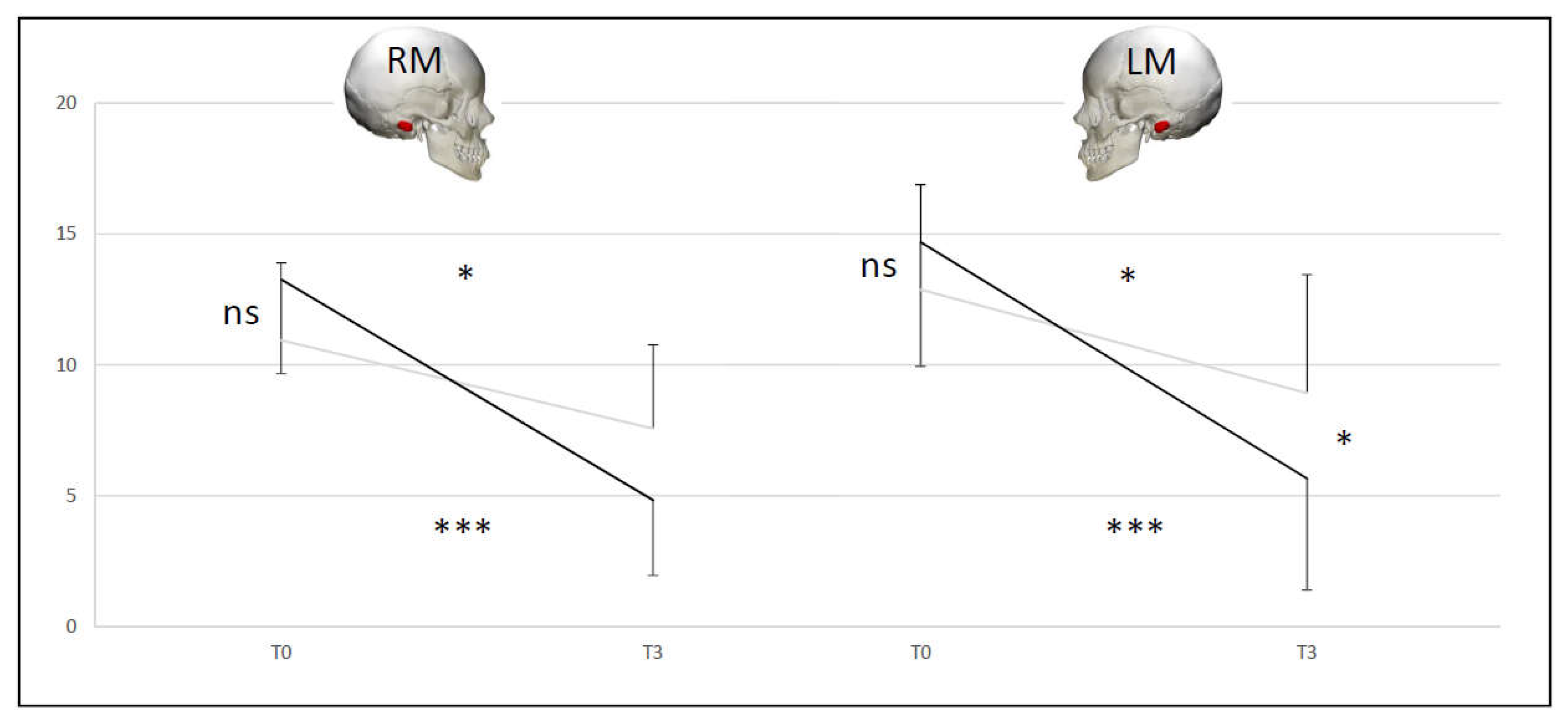

• SVINT A+D group vs B+C group (DHI < 32 vs DHI ≥ 32)

At T0 there was no difference between the two couple of groups (NS). The A+D (p < 0.001) and B+C (p < 0.05) groups were different at T3 compared to T0 for the SVINT on stimulating right and left mastoid. For the right mastoid stimulation at T3 34% of the initial T0 abnormal values recovered normal function for A+D group and 9% for B+C group. For the left mastoid stimulation at T3 34% of the initial T0 abnormal values recovered normal function for A+D group and 18% for B+C group. No significant differences between right and left mastoid (

Figure 7).

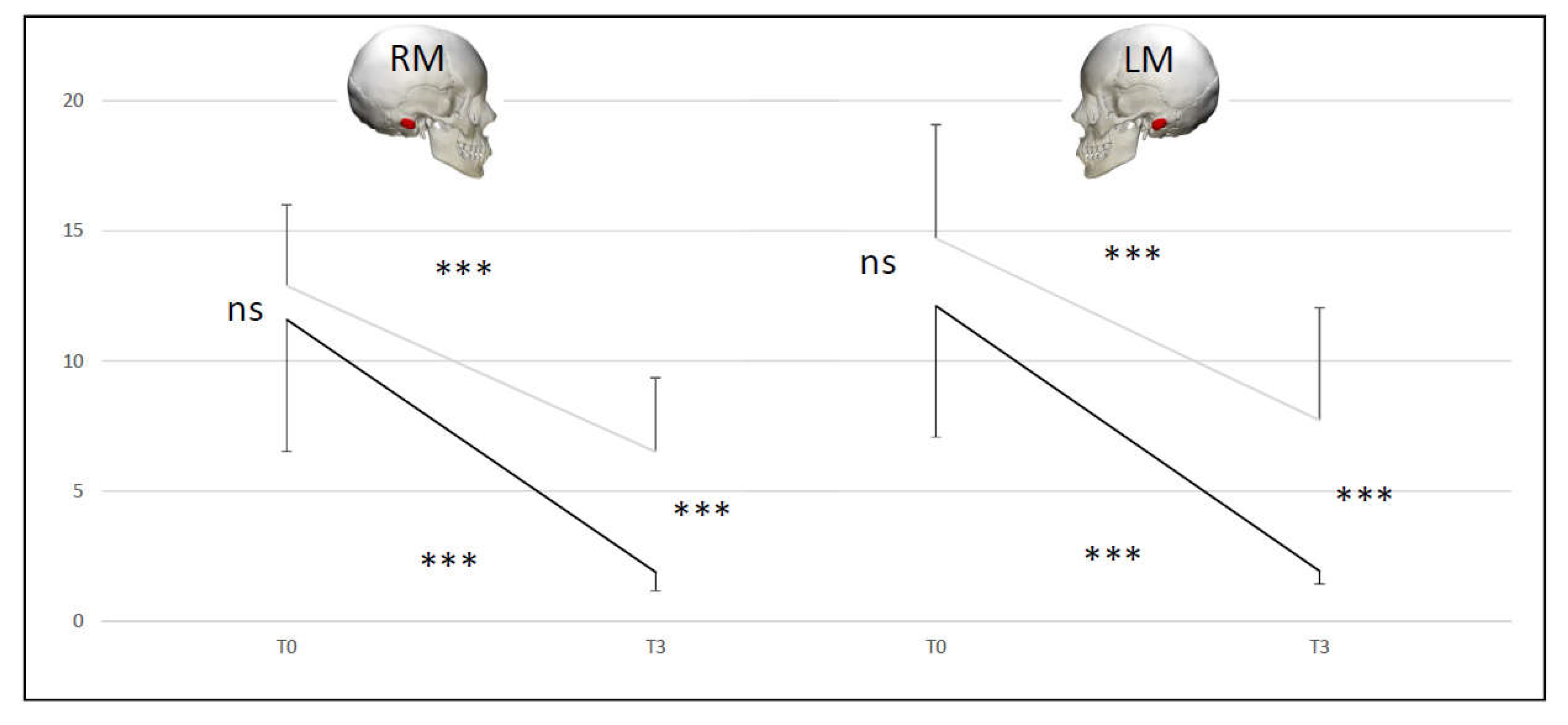

• SVINT A+B group vs C+D group (normal Exams vs pathological Exams)

At T0 there was no difference between the two couple of groups (NS), but there was at T3 (p < 0.001). The C+D and A+B groups were different at T3 compared to T0 (p < 0.001). For the right mastoid stimulation at T3 87.5% of the initial T0 abnormal values recovered normal function for A+B group and 12.5% for C+D group. For the left mastoid stimulation at T3 100% of the initial T0 abnormal values recovered normal function for A+B group and 12.5% for C+D group. No significant differences between right and left mastoid (

Figure 8).

In the

Table 3 are summarized the percentage of recovery to normal function at T3

vs T0, matching the four couples of patient groups with the instrumental tests (BCT, lateral SCC VHIT, anterior SCC VHIT, right mastoid SVINT and left mastoid SVINT).

A+D group (DHI < 32) showed low percentages of recovery, except for the anterior SCC VHIT gain.

B+C group (DHI ≥ 32) showed very low percentages of recovery for all the instrumental tests.

A+B group (normal exams) reached 100% of recovery in near all instrumental tests.

C+D group (pathological exams) remained to 0 or very low percentage values of recovery, except for the anterior SCC VHIT gain.

4. Discussion

Our study showed that CVRFs were associated with a poorer symptom recovery but not age or BMI. Vestibular tests specifically BCT (canal paresis %), VHIT (lateral SCC gain) and SVINT (nystagmus slow phase velocity) recovered to normal values in 20%, 20%, 26% of cases respectively at T3 for the 40-patient group.

To clarify these results, a group corresponding to VN patients with normal assessments and abnormal subjective results, was proposed (B group).

4.1. Vestibular compensation criteria in the literature

In 2001 Eisenman et al. [

58] stated that compensation can be considered incomplete when patients present any one of the four proposed criteria. In 2020 Guajardo-Vergara et al. [

53] partially modified these criteria.

In contrast to the original classification proposed by Eiseman et al, Guajardo-Vergara et al considered each criterion in isolation. They decided to add the DHI total score, and following previous data, they established an arbitrary criterion of 32 points in the DHI to determine the state of general vestibular compensation of the subjects. Those one with a DHI total score <32 were described as compensated and those with a DHI total score ≥32 non compensated (

Table 4).

Furthermore, Guajardo-Vergara et al. showed how the PR index, which can easily be obtained during the v-HIT could become an objective measure of the state of compensation [

53]. This score has been shown to be different when patients are classified according to their clinical setting, to their results in the DHI test, or to results obtained on the rotatory chair test. When these three criteria were combined to categorize the patients, this score was also significantly different between the two populations obtained in the cluster analysis; a PR cut off value of 55 clearly separates a compensated from a non-compensated patient. In addition to providing an objective evaluation, this measure also has the potential to serve as a criterion for use in the follow-up evaluation in patients suffering ongoing symptoms after an AVS.

The PR index diminishes in parallel (1) with the reduction in the DHI score in patients with chronic instability because of a long-standing unilateral vestibulopathy, and (2) after following a vestibular rehabilitation program [

60]. These findings indicate that saccades in different impulses tend to appear time-locked from the initiation of the head movement onward, whereas in non-compensated patients the PR index remains high [

28,

43].

When vestibular compensation takes place, overt CS progressively decrease in number and velocity and become gathered covert CS, although VOR gain remains unchanged [

60].

The CS type and the moment of appearance can provide valuable information on the level of VN compensation: the presence of covert saccades only is associated with a higher degree of compensation, while the simultaneous presence of covert and overt saccades is associated with a lower degree of compensation [

49].

We based our study on a questionnaire (DHI) for evaluating the subjective symptoms and on three instrumental tests (BCT, VHIT, SVINT), to cover the vestibular system bandwidth, for evaluating the objective level of healing and compensation. We adopted the Guajardo-Vergara et al compensation criteria, especially the cut off for the DHI total score (≥ 32 for pathologic patients).

An original diagram is proposed (

Figure 9). It summarizes the various parameters (DHI, spontaneous Ny, BCT, VHIT and SVINT) that characterize VN at its onset. Based on the evolution of the parameters considered, four evolutionary lines are considered, which correspond to the proposed groups: normalization of all tests with normal (A group) or pathological (B group) DHI, persistence of pathological tests with ineffective objective instrumental compensation parameters and pathological DHI (C group) and pathological tests with effective objective instrumental compensation parameters and normal DHI (D group). The symptom profile of the various evolutionary groups are: asymptomatic (A group); chronic dizziness (B and C groups); and pauci- or a-symptomatic (D group).

4.2. Cardiovascular risk factors among patients with VN

A significantly higher prevalence of CVRFs was found among patients presenting with VN in comparison to the general population. This finding may suggest a possible correlation between CVRFs and VN, which may be mediated through small blood vessel occlusion and labyrinthine ischemia [

61].

3D High-Resolution temporal bone histopathology has shown evidence that the anatomy of the labyrinth may make the superior vestibular artery more vulnerable to external compression if the adjacent superior vestibular nerve becomes oedematous in response to injury or inflammation or is affected by tumour. While the veins do not appear to be vulnerable to adjacent neural oedema, an arteriovenous crossing was found in both high-resolution ears where the inferior vestibular artery crosses the superior vestibular vein. In this way, viral damage to the nerve could also be mediated by a vascular mechanism [

62].

Another study did not observe a significant difference in the prevalence of arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, prior history of stroke, transitory ischemic attack, or active smoking between patients with idiopathic BPPV and BPPV secondary to peripheral AVS. It means that clinically, it is not possible to determine whether AUVP is due to ischemia of the anterior vestibular artery or inflammation of the superior vestibular nerve [

63].

A recent investigation has shown that patients with SVN did not present more CVRFs (age, gender, high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, smoking, documented cardiovascular disease, and atrial fibrillation) than the general population. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as LDL-cholesterol > 1.6 g/L or ongoing lipid-lowering treatment. This study argues for involvement of the superior vestibular nerve rather than the anterior vestibular artery in SVN [

64].

Finally, a retrospective cohort study stated that patients with VN and CVRFs are older on average than patients without CVRFs; however, there are no significant differences in the mean VOR gain at diagnosis or follow-up between the groups with and without CVRFs. Factors such as age and CVRFs did not significantly impact the VOR gain at diagnosis [

65].

In our study diabetes and hypercholesterolemia are factors associated with persistent subjective complaints (B+C group). In the same way hypercholesterolemia plays an important role in patients who do not recover instrumentally (C+D group).

In patients examined during the acute phase of VN, it may be useful to measure cholesterol. In case of increased level, a statin therapy should be administrated.

4.2. Evolution of instrumental testing in VN

Our results showed that all the vestibular tests including SCC explorations (BCT, VHIT) and more global tests including SCCs and utricle function (SVINT) improved similarly regardless of the frequency they assessed and that there was no strict relationship with subjective recovery.

4.2.1. Bithermal Caloric Test (BCT)

In the literature there is a debate whether (1) CP can improve over time and also if there is a relationship between its extent and the patient's outcome.

(1) With regard to the development of CP, lateral SCC impairment usually persists for more than a year in VN [

17,

19,

28,

66,

67,

68]. One other study showed a normalization of the CP in 35% of the patients one year after symptom onset [

69] and another one with a long-term follow-up showed a complete recovery of labyrinthine function, assessed by caloric irrigation, in 50 to 70% of cases [

70,

71]. The low-frequency function of the labyrinths often recovered its symmetry [

12,

72]. In summary, there are conflicting opinions regarding the incidence of improvement in CP.

(2) With regard to any correlation between symptoms and CP, authors have showed an absence of relationship between BCT and disappearance of symptoms since patients free of symptoms may have persistent reduced caloric responses [

27,

73,

74,

75]. In summary, there is no correlation between the degree of persistent CP and residual symptoms.

In our study, in our group of 40-patients, 20% recovered normal caloric function between T0 and T3. Both groups with persistent subjective complaints (B+C) and groups without symptoms (A+D) maintained an abnormal CP but with higher impairment in the first group at T3.

4.2.2. Video Head Impulse Test (VHIT)

In the literature there is debate whether (1) the VHIT gain improves after the acute phase, (2) if there is a correlation between the outcome and the VHIT gain, and (3) if there is a correlation between the outcome and the appearance and organization of VHIT CS.

(1) With regard to VHIT gain improvement, high-frequency response often remains impaired [

72]. Although a total recovery can take place, in some cases there is no improvement [12,38,49,76–79]. Peripheral recovery or central increase of VOR gain on the affected side may explain the improvement of VHIT gains [

28,

35,

53,

56,

67,

71,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84]. In summary, there are conflicting views regarding the incidence of improved VOR gain (no, partial or total improvement).

(2) With regard to any correlation between symptoms and VHIT gain, there is no relationship between the lateral SCC VOR gain and chronic symptoms following VN [

27,

49,

53,

68,

72,

74]. Another study did suggest that an increase of VOR gain can predict an improvement of symptoms [

79]. Patients with abnormal VHIT gain continue to be troubled by many chronic symptoms [

68,

77,

78,

85]. In summary, there are conflicting opinions regarding the correlation between VOR gain and residual symptoms.

(3) With regard to any correlation between symptoms and VHIT CS, patients with mixed covert and overt saccades continue to be troubled by many chronic symptoms. Covert saccades can play a very key role in compensation of inadequate VOR response and return to a normal lifestyle [

28,

49,

56,

68,

77,

78,

79]. In summary, the appearance of covert saccades only (with no overt saccades seen), with a similar latency (high PR index) may play a role in compensating for a functionally inadequate VOR.

In our study, in group of 40 patients, 20% recovered between T0 and T3 for the lateral SCC and 55% recovered between T0 and T3 for the anterior SCC.

For lateral SCC at T3 24% of the initial T0 abnormal values recovered normal function for A+D group and 9% for B+C group. For anterior SCC at T3 59% of the initial T0 abnormal values recovered normal function for A+D group and 36% for B+C group. There was no change in A+B and C+D groups for the anterior canal. The higher resistance to injury and the higher recovery possibilities of anterior SCC compared to the lateral one have been reported in the literature [

37].

4.2.3. Skull Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Test (SVINT)

In the literature there is agreement about SVIN not being modified by vestibular compensation in case of persistent lesions on type I inner ear hair cells and/or irregular discharging neurons. SVINT reveals in this condition a persistent asymmetry of activity after stimulation at the level of the vestibular nucleus [

40,

42,

57,

86].

There is a positive linear correlation between VOR gain asymmetry and the SVIN-SPV at 100 Hz. This finding adds more knowledge about SVIN: an asymmetry in vestibular function measured with VHIT leads to a positive SVIN test [

22].

The SVIN-SPV, VOR gain asymmetry, and PR index decrease over time after a UVL. In addition, there is a positive association between the SVIN-SPV and VOR gain difference, as well as between the SVIN-SPV and the PR index. Both tests are useful in the follow-up of VN, as they could reflect its clinical compensation, or more accurately its partial recovery for type I inner ear hair cells or fibres with irregular discharges [

23].

The SVIN was confirmed in our study to be a pertinent and sensitive test, since it was positive in all cases of VN.

In our study, 26% of our patients recovered between T0 and T3. The vibration induced Ny is slightly reduced at T3 in patients with persistent subjective complaints (B+C group).

4.3. Patients with increased DHI total score and normal instrumental tests

In our study a possible occurrence of PPPD during VN evolution was only observed in one case but in literature this situation is described more frequently. It was reported in 20/51 VN patients by Li et al [

87] and was also described by Kobaya et al [

88].

Other publications [

22,

27] showed that symptom evolution was not correlated with objective test results (e.g., BCT, VHIT,) but could be linked to acquiring a visual dependency [

74] or perhaps due to central dysfunction, as described by Jauregui-Renaud et al. [

89] and Staab et al. [

90].

4.4. Limitations of the study and future perspectives

There were fewer patients in our study complaining of persistent symptoms but having a normal set of vestibular tests (group B). However, the literature provides higher percentages of patients, with normalized instrumental tests but with persisting subjective symptoms [

87]. The interpretation of this finding could be that the time interval between the onset of VN and that of the second assessment (three months) was not long enough for the development of PPPD in B and C groups (of note is that first criteria for PPPD diagnosis is the persistence of symptoms for at least three months or longer [

91].

VEMPs were not assessed for logistical reasons and for maintaining the focus on the SCC portion of the vestibular apparatus. However, the SVINT is a global test which stimulates also the phasic receptors of SCCs and utricle. [

42,

92].

The VHIT device used in our department did not provide the PR index, and so the latency pattern evaluation (gathered and scattered CS) was not possible. The PR index was therefore replaced by a clinical assessment of the temporal dispersion of CS, which was not included in the study.

Further studies are scheduled to also analyse also the vertical component of eye movements in spontaneous Ny, Ny evoked by HST and SVINT. It is hoped that these studies will provide more information in evolution of VN. Similarly, the performed Motion Sickness Susceptibility and Visual Vestibular Mismatch questionnaires will also be taken in account, in order to get a better understanding of patients who have recovered by healing, versus those who have had to compensate for persisting pathology.

5. Conclusions

Understanding and quantifying vestibular compensation is essential to the correct classification of vestibular neuritis patients who are at risk of chronic dizziness. Even subjects with recovery of function, as documented by complete objective vestibular tests, can manifest chronic subjective symptoms of disequilibrium.

We propose a novel subdivision to four groups of patients that allows an easier classification and follow-up. Contemporary use of subjective evaluation (DHI) and objective evaluation, which explore the vestibular system at different frequencies (BCT, VHIT, SVINT), are useful to distinguish between low and high levels of compensation effectiveness when healing to normal function does not occur.

In our series we did not observe any significant difference in the evolution and recovery of high or low frequency vestibular tests in patients who did not complain of subjective symptoms. Some patients with objective recovery as documented by testing may still show persisting subjective symptoms.

Age, gender, and BMI have not showed any correlations with the extent to which symptoms have subsided. Vascular risk factors (hypercholesterolemia) were correlated with patients presenting persistent symptoms and who did not recover (as documented by objective vestibular testing).

We suggest that patients detected at the acute period with a hypercholesterolemia might be treated by institution of a statin therapy, after a cardiologic opinion and blood testing.

More information about the profiling of patients who recover by healing or compensation is expected from the complementary analysis of vertical component of eye movements and the Motion Sickness Susceptibility and Visual Vestibular Mismatch questionnaires.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, EA, GD, PP; methodology, EA, GD, PP; software, MC; validation, EA, GD, FP, MC, PP; formal analysis, GD, PP; resources, EA, FP.; data curation, EA, FP; writing—original draft preparation, EA, GD, MC, PP; writing—review and editing, EA, GD, MC, PP; supervision, GD, PP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of dell’AULSS 3 Serenissima Regione Veneto, Mirano -Venezia-, Italy (protocol code 157A/CESC, December 22nd, 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Requests may be directed to Dr Enrico Armato (MD).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Art Mallinson (Vancouver, British Columbia, CA) for his helpful advice in the final read-through of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

AI: asymmetry index, AVS: acute vestibular syndrome, AUVP: acute unilateral vestibulopathy, BCT: bithermal caloric test, BPPV: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, CP: canal paresis, CS: corrective saccades, CVRFs: cardiovascular risk factors, DHI: dizziness handicap inventory, HINTS: head impulse, nystagmus, test skew, HST: head shaking test, NS: not significant, Ny: nystagmus, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, PPPD: persistent postural-perceptual dizziness, PR: Perez-Rey, SCA: superior cerebellar artery, SCC: semicircular canal, SPV: slow phase velocity, SVIN: skull vibration – induced nystagmus, SVINT: skull vibration – induced nystagmus test, T0: first assessment at VN diagnosis time, T3: second assessment 90±15 days (3 months) from onset of VN symptoms, VEMPs: vestibular evoked myogenic potentials, VHIT: video head impulse test, VIF: variance inflation factor, VNG: videonystagmography, VN: vestibular neuritis, VOR: vestibulo-ocular reflex.

References

- Rujescu D, Hartmann AM, Giegling I, Konte B, Herrling M, Himmelein S, Strupp M. Genome-Wide Association Study in Vestibular Neuritis: Involvement of the Host Factor for HSV-1 Replication. Front Neurol. 2018, 9, 591. [CrossRef]

- Han W, Wang D, Wu Y, Fan Z, Guo X, Guan Q. Correlation between Vestibular Neuritis and cerebrovascular risk factors. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2018, 39, 751–753. [CrossRef]

- Kim KT, Park S, Lee S-U, Park E, Kim B, Kim B-J, Kim J-S. Four-hour-delayed 3D-FLAIR MRIs in patients with acute unilateral peripheral vestibulopathy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2024, Jun 14. [CrossRef]

- Byun H, Chung JH, Lee SH, Park CW, Park DW, Kim TY. Clinical value of 4-hour delayed gadolinium-Enhanced 3D FLAIR MR Images in Acute Vestibular Neuritis. Laryngoscope. 2018, 128, 1946–1951. [CrossRef]

- Zwergal A, Möhwald K, Salazar López E, Hadzhikolev H, Brandt T, Jahn K, Dieterich M. A Prospective Analysis of Lesion-Symptom Relationships in Acute Vestibular and Ocular Motor Stroke. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 822. [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Sanchez, J.; Martin-Sanz, E. Long-Term Evolution of Vestibular Compensation, Postural Control, and Perceived Disability in a Population of Patients with Vestibular Neuritis. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerber, K.A. Acute Vestibular Syndrome. Semin Neurol. 2020, 40, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi KD, H lee, Kim JS. Ischemic syndromes causing dizziness and vertigo. Handbook Clin Neurol. 2016; 137: 317-340. [CrossRef]

- Kattah, JC. Use of HINTS in the acute vestibular syndrome. An Overview. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2018, 3, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asprella-Libonati, G. Lateral canal BPPV with Pseudo-Spontaneous Nystagmus masquerading as vestibular neuritis in acute vertigo: a series of 273 cases. J Vestib Res. 2014, 24(5-6):343-9. [CrossRef]

- Himmelein S, Lindemann A, Sinicina I, Horn AK, Brandt T, Strupp M, Hüfner K. Differential Involvement during Latent Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Infection of the Superior and Inferior Divisions of the Vestibular Ganglia: Implications for Vestibular Neuritis. J Virol. 2017, 91, e00331-17. [CrossRef]

- Büki B, Hanschek M, Jünger H. Vestibular neuritis: Involvement and long-term recovery of individual semicircular canals. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2017 Jun;44(3):288-293. [CrossRef]

- Hwang K, Kim BG, Lee JD, Lee E-S, Lee TK, Sung KB. The extent of vestibular impairment is important in recovery of canal paresis of patients with Vestibular Neuritis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2019, 46, 24–26. [CrossRef]

- Aw ST, Fetter M, Cremer PD, Karlberg M, Halmagyi GM. Individual semicircular canal function in superior and inferior vestibular neuritis. Neurology. 2001 Sep 11;57(5):768-74. [CrossRef]

- Magliulo G, Gagliardi G, Ciniglio Appiani M, Iannella G, Re M. Vestibular neurolabyrinthitis: a follow-up study with cervical and ocular vestibular evoked myogenic potentials and the video head impulse test. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2014 Mar;123(3):162-73. [CrossRef]

- Navari E, Casani PA. Lesion Patterns and Possible Implications for Recovery in Acute Unilateral Vestibulopathy. Otol Neurotol. 2020 Feb;41(2): e250-e255. [CrossRef]

- Lee SU, Park SH, Kim HJ, Koo JW, Kim JS. Normal Caloric Responses during Acute Phase of Vestibular Neuritis. Normal Caloric Responses during Acute Phase of Vestibular Neuritis. J Clin Neurol. 2016 Jul;12(3):301-7. [CrossRef]

- Ahn SH, Shin JE, Kim CH. Final diagnosis of patients with clinically suspected vestibular neuritis showing normal caloric response. J Clin Neurosci. 2017 Jul:41:107-110. [CrossRef]

- Kim HJ, Kim DJ, Hwang JH, Kim KS. Vestibular Neuritis With Minimal Canal Paresis: Characteristics and Clinical Implication. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Jun;10(2):148-152. [CrossRef]

- Lee SA, Lee ES, Kim BG, Lee TK, Sung KB, Hwang K, Lee JD. Acute vestibular asymmetry disorder: a new disease entity in acute vestibular syndrome? Acta Otolaryngol. 2019 Jun;139(6):511-516. [CrossRef]

- Lee JY, Kwon E, Hyo Kim HJ, Choi JY, Oh HJ, Koo JW, Kim JS. Dissociated Results between Caloric and Video Head Impulse Tests in Dizziness: Prevalence, Pattern, Lesion Location, and Etiology. J Clin Neurol. 2020 Apr;16(2):277-284. [CrossRef]

- Batuecas-Caletrío A, Martínez-Carranza R, García Nuñez GM, Fernández Nava MJ, Sánchez Gómez H, Santacruz Ruiz S, Pérez Guillén V, Pérez-Fernández N. Skull vibration-induced nystagmus in vestibular neuritis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2020 Dec;140(12):995-1000. [CrossRef]

- Díaz MPG, Torres-García L, Zamora EG, Jiménez ABC, Pérez Guillén V. Is Skull Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Useful in Vestibular Neuritis Follow Up? Audiol Res. 2022 Feb 26;12(2):126-131. [CrossRef]

- Ranjbaran M, Katsarkas A, Galiana HL. Vestibular Compensation in Unilateral Patients Often Causes Both Gain and Time Constant Asymmetries in the VOR. 2016 Mar 29:10:26. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Sanz E, Diaz JY, Esteban-Sanchez J, Sanz-Fernández R, Perez-Fernandez N. Delayed Effect and Gain Restoration After Intratympanic Gentamicin for Menière’s Disease. Otol. Neurotol. 2019, 40, 79–87. [CrossRef]

- Cousins S, Kaski D, Cutfield N, Arshad Q, Ahmad H, Gresty MA, Seemungal BM, Golding J, Bronstein AM. Predictors of clinical recovery from Vestibular Neuritis: A prospective study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2017, 4, 340–346. [CrossRef]

- Patel M, Arshad Q, Roberts RE, Ahmad H, Bronstein AM. Chronic Symptoms After Vestibular Neuritis and the High-Velocity Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex. Otol Neurotol. 2016, 37, 179–184. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Sanz E, Rueda A, Esteban-Sanchez J, Yanes J, Rey-Martinez J, Sanz-Fernandez R. Vestibular Restoration and Adaptation in Vestibular Neuritis and Ramsay Hunt Syndrome with Vertigo. Otol Neurotol. 2017, 38, e203–e208. [CrossRef]

- Yang CJ, Cha EH, Park JW, Kang BC, Yoo MH, Kang WS, Ahn JH, Chung JW, Park HJ. Diagnostic Value of Gains and Corrective Saccades in Video Head Impulse Test in Vestibular Neuritis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018, 159, 347–353. [CrossRef]

- Arshad Q, Cousins S, Golding JF, Bronstein AM. Factors influencing clinical outcome in vestibular neuritis – A focused review and reanalysis of prospective data. J Neurol Sci. 2023 Mar 15:446:120579. [CrossRef]

- Strupp M, Bisdorff A, Furman J, Hornibrook J, Jahn K, Maire R, Newman-Toker D, Magnusson M. Acute unilateral vestibulopathy/vestibular neuritis: Diagnostic criteria. Consensus document of the committee for the classification of vestibular disorders of the Bárány Society. J Vestib Res. 2022; 32(5): 389–406. Published online 2022 Oct 20. Pre-published online 2022 Jun 11. [CrossRef]

- Newman-Toker DE, Kerber KA, Hsieh YH, Pula JH, Omron R, Saber Tehrani A, Mantokoudis G, Hanley DF, Zee DS, Kattah JC. HINTS outperforms ABCD2 to screen for stroke in acute continuous vertigo and dizziness. Acad Emerg Med. 2013,20, 986–996. [CrossRef]

- Cullen, KE. The vestibular system: multimodal integration and encoding of self-motion for motor control. Trends Neurosci. 2012 Mar;35(3):185-96. [CrossRef]

- Cullen, KE. Vestibular processing during natural self-motion: implications for perception and action. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019 Jun;20(6):346-363. [CrossRef]

- Zellhuber S, Mahringer A, Rambold HA. Relation of video-head-impulse test and caloric irrigation: a study on the recovery in unilateral Vestibular Neuritis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid-Priscoveanu A, Böhmer A, Obzina H, Straumann D. Caloric and search-coil head-impulse testing in patients after Vestibular Neuritis. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2001, 2, 72–78. [CrossRef]

- Halmagyi GM, Chen L, MacDougall HG, Weber KP, Mc Garvie LA, Curthoys IS. The Video Head Impulse Test. Front Neurol. 2017 8, 258. [CrossRef]

- McGarvie LA, MacDougall HG, Curthoys IS, Halmagyi GM. Spontaneous Recovery of the Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex After Vestibular Neuritis; Long-Term Monitoring With the Video Head Impulse Test in a Single Patient. Front Neurol. 2020 Jul 28;11:732. [CrossRef]

- Batuecas-Caletrio A, Rey-Martinez J, Trinidad-Ruiz G, Matiño-Soler E, Santa Cruz-Ruiz S, Muñoz-Herrera A, Perez-Fernandez N. Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex Stabilization after Vestibular Schwannoma Surgery: A Story Told by Saccades. Front Neurol. 2017 Jan 25:8:15. [CrossRef]

- Dumas G, Curthoys IS, Lion A, Perrin P, Schmerber S. The Skull Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Test of Vestibular Function-A Review. Front Neurol. 2017 Mar 9:8:41. [CrossRef]

- Dumas G, Perrin P, Ouedraogo E, Schmerber S. How to perform the skull vibration-induced nystagmus test (SVINT). Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2016 Nov;133(5):343-348. [CrossRef]

- Fabre C, Tan H, Dumas G, Giraud L, Perrin P, Schmerber S. Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus Test: Correlations with Semicircular Canal and Otolith Asymmetries. Audiol Res. 2021 Nov 15;11(4):618-628. [CrossRef]

- Chays A, Florant A, Ulmer E. Les Vertiges. Masson, Collection consulter prescrire. 2004, pag. 113.

- Jacobson GP, Newman CW. The development of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990 Apr;116(4):424-7. [CrossRef]

- Colnaghi S, Rezzani C, Gnesi M, Manfrin M, Quaglieri S, Nuti D, Mandalà M, Monti MC, Versino, M. Validation of the Italian Version of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory, the Situational Vertigo Questionnaire, and the Activity-Specific Balance Confidence Scale for Peripheral and Central Vestibular Symptoms. Front Neurol. 2017,8, 528. [CrossRef]

- Bosser G, Caillet G, Gauchard G, Marçon F, Perrin P. Relation between motion sickness susceptibility and vasovagal syncope susceptibility. Brain Res Bull. 2006 Jan 15;68(4):217-26. [CrossRef]

- Mallinson, A. Visual Vestibular Mismatch: a poorly understood presentation of balance system disease, Dissertation to obtain the degree of Doctor at the Maastricht University, 2011.

- Whitney SL, Wrisley DM, Brown KE, Furman JM. Is perception of handicap related to functional performance in persons with vestibular dysfunction? Otol Neurotol. 2004 Mar;25(2):139-43. [CrossRef]

- Kunel'skaya NL, Baibakova EV, Guseva AL, Nikitkina YY, Chugunova MA, Manaenkova EA. The compensation of the vestibulo-ocular reflex during rehabilitation of the patients presenting with Vestibular Neuritis. Vestn Otorinolaringol. 2018;83(1):27-31. [CrossRef]

- Verbecque E, Wuyts FL, Vanspauwen R, Van Rompaey V, Van de Heyning P, Vereeck L. The Antwerp Vestibular Compensation Index (AVeCI)- an index for vestibular compensation estimation, based on functional balance performance. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021 Jun;278(6):1755-1763. [CrossRef]

- Giray M, Kirazli Y, Karapolat H, Celebisoy H, Bilgen C, Kirazli T. Short-term effects of vestibular rehabilitation in patients with chronic unilateral vestibular dysfunction: a randomized controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009 Aug;90(8):1325-31. [CrossRef]

- Adamec I, Krbot Skorić M, Ozretić D, Habek M. Predictors of development of chronic vestibular insufficiency after vestibular neuritis. J Neurol Sci. 2014 Dec 15;347(1-2):224-8. [CrossRef]

- Guajardo-Vergara C, Perez-Fernandez N. A New and Faster Method to Assess Vestibular Compensation: A Cross-Sectional Study. 2020 Dec;130(12):E911-E917. [CrossRef]

- Manzari L, Burgess AM, MacDougall HG, Curthoys IS. Vestibular function after Vestibular Neuritis. Int J Audiol. 2013 Oct;52(10):713-8. [CrossRef]

- Curthoys, I.S.; Halmagyi, G.M. Vestibular compensation: a review of the oculomotor, neural, and clinical consequences of unilateral vestibular loss. J Vestib Res. 1995, 5, 67–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacour M, Helmchen C, Vidal PP. Vestibular compensation: the neuro-otologist's best friend. J Neurol. 2016 Apr;263 Suppl 1:S54-64. [CrossRef]

- Curthoys, IS. The Neural Basis of Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus (SVIN). Audiol Res. 2021 Oct 14;11(4):557-566. [CrossRef]

- Eisenman DJ, Spears R, Telian SA. Labyrinthectomy versus Vestibular Neurectomy: Long-term Physiologic and Clinical Outcomes. Otology & Neurotology. 2001, 22:539–548. [CrossRef]

- Yagi C, Kimura A, Horii A. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness: A functional neuro-otologic disorder. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2024 Jun;51(3):588-598. [CrossRef]

- Matiñó-Soler E, Rey-Martinez J, Trinidad-Ruiz G, Batuecas-Caletrio A, Perez Fernanndez N. A new method to improve the imbalance in chronic unilateral vestibular loss: the organization of refixation saccades. Acta Otolaryngol. 2016;136:894–900. [CrossRef]

- Oron Y, Shemesh S, Shushan S, Cinamon U, Goldfarb A, Dabby R, Ovnat Tamir S. Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Patients with Vestibular Neuritis. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 2017, Vol. 126(8) 597–601. [CrossRef]

- Büki B, Mair A, Pogson JM, Andresen NS, Ward BK. Three-Dimensional High-Resolution Temporal Bone Histopathology Identifies Areas of Vascular Vulnerability in the Inner Ear. Audiol Neurotol. 2022;27:249–259 -. [CrossRef]

- Waissbluth S, Becker J, Sepúlveda V, Iribarren J, García-Huidobro F. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo Secondary to Acute Unilateral Peripheral Vestibulopathy: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Risk Factors. J Int Adv Otol. 2023; 19(1): 28-32 -. [CrossRef]

- Pâris P, Charpiot A, Veillon F, Severac F, Djennaoui I. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in superior vestibular neuritis: A cross-sectional study following STROBE guidelines. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2022 Aug;139(4):194-197. [CrossRef]

- Coronel-Touma GS, Monopoli-Roca C, Almeida-Ayerve CN, Marcos-Alonso S, de la Torre-Morales DG, Serradilla-López J, Santa Cruz-Ruiz S, Batuecas-Caletrío Á, Sánchez-Gómez H. Influence of Age and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Vestibular Neuritis: Retrospective Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2023 Oct 16;12(20):6544. [CrossRef]

- Allum JHJ, Honegger F. Correlations Between Multi-plane vHIT Responses and Balance Control After Onset of an Acute Unilateral Peripheral Vestibular Deficit. Otol Neurotol. 2020 Aug;41(7):e952-e960. [CrossRef]

- Lee H-J, Kim S-H, Jung J. Long-Term Changes in Video Head Impulse and Caloric Tests in Patients with Unilateral Vestibular Neuritis. Korean J Otorhinolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2019;62(1):23-7. h ttps://doi.org/10.3342/kjorl-hns.2017.01081.

- Lee J-H, Kim M-B. Importance of Video Head Impulse Test Parameters for Recovery of Symptoms in Acute Vestibular Neuritis. Otol Neurotol. 2020 Aug;41(7):964-971. [CrossRef]

- Choi K-D, Oh S-Y, Kim H-J, Koo J-W, Cho BM, Kim JS. Recovery of vestibular imbalances after vestibular neuritis. Laringoscope. 2007 Jul;117(7):1307-12. [CrossRef]

- Strupp M, Brandt T. Vestibular Neuritis. Semin Neurol. 2009 Nov;29(5):509-19. [CrossRef]

- Reinhard, A.; Maire, R. Névrite vestibulaire: traitment et prognostic. Rev Med Suisse. 2013, 9, 1775–1779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palla A, Straumann D, Bronstein AM. Vestibular neuritis: vertigo and the high-acceleration vestibulo-ocular reflex. J Neurol. 2008 Oct;255(10):1479-82. [CrossRef]

- Nadol JB, Jr. Vestibular neuritis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995 Jan;112(1):162-72. [CrossRef]

- Cousins S, Cutfield NJ, Kaski D, Palla A, Seemungal BM, Golding JF, Staab JP, Bronstein AM. Visual Dependency and Dizziness after Vestibular Neuritis. PLoS One. 2014 Sep 18;9(9):e105426. [CrossRef]

- Bronstein AM, Dieterich M. Long-term clinical outcome in vestibular neuritis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019 Feb;32(1):174-180. [CrossRef]

- Allum JHJ, Scheltinga A, Honegger F. The Effect of Peripheral Vestibular Recovery on Improvements in Vestibulo-ocular Reflexes and Balance Control After Acute Unilateral Peripheral Vestibular Loss. Otol Neurol. 2017 Dec;38(10):e531-e538. [CrossRef]

- Cerchiai N, Navari E, Sellari-Franceschini S, Re C, Casani AP. Predicting the Outcome after Acute Unilateral Vestibulopathy Analysis of VOR Gain and Catch-up Saccades. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018 Mar;158(3):527-533. [CrossRef]

- Fu W, He F, Wei D, Bai Y, Shi Y, Wang X, Han J. Recovery Pattern of High-Frequency Acceleration Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex in Unilateral Vestibular Neuritis: A Preliminary Study. Front Neurol. 2019 Mar 7:10:85. [CrossRef]

- Manzari L, Tramontano M. Suppression Head Impulse Paradigm (SHIMP) in evaluating the vestibulo-saccadic interaction in patients with vestibular neuritis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 Nov;277(11):3205-3212. [CrossRef]

- Manzari L, Burgess AM, MacDougall HG, Curthoys IS. Objective verification of full recovery of dynamic vestibular function after superior vestibular neuritis. Laringoscope. 2011 Nov;121(11):2496-500. [CrossRef]

- Yang CJ, Cha E-H, Park JW, Kang BC, Yoo MH, Kang WS, Ahn JH, Chung JW, Park HJ. Diagnostic Value of Gains and Corrective Saccades in VHIT in Vestibular Neuritis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018 Aug;159(2):347-353. [CrossRef]

- Tighilet B, Bordiga P, Cassel R, Chabbert C. Peripheral vestibular plasticity vs central compensation: evidence and questions. J Neurol. 2019 Sep;266(Suppl 1):27-32. [CrossRef]

- Allum JHJ, Honegger F. Correlations Between Multi-plane vHIT Responses and Balance Control After Onset of an Acute Unilateral Peripheral Vestibular Deficit. Otol Neurotol. 2020 Aug;41(7):e952-e960. [CrossRef]

- Allum JHJ, Honegger F. Improvement of Asymmetric Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex Responses Following Onset of Vestibular Neuritis Is Similar Across Canal Planes. Front Neurol. 2020 Oct 6:11:565125. [CrossRef]

- Jeong S-H, Kim H-J, KimJ-S. Vestibular neuritis. Semin Neurol. 2013 Jul;33(3):185-94. [CrossRef]

- Matos R, Navarro M, Pérez-Guillén V, Pérez-Garrigues H. The role of vertical semicircular canal function in the vertical component of skull vibration-induced nystagmus. Acta Otolaryngol. 2020 Aug;140(8):639-645. [CrossRef]

- Li F, Xu J, Liu D, Wang J, Lu L, Gao R, Zhou X, Zhuang J, Zhang S. Optimizing vestibular neuritis management with modular strategies. Front Neurol. 2023 Sep 14;14:1243034. [CrossRef]

- Kabaya K, Tamai H, Okajima A, Minakata T, Kondo M, Nakayama M, Iwasaki S. Presence of exacerbating factors of persistent perceptual-postural dizziness in patients with vestibular symptoms at initial presentation. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2022 Jan 25;7(2):499-505. doi: 10.1002/lio2.735. Erratum in: Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2023 Nov 30;8(6):1692. doi: 10.1002/lio2.1179. PMID: 35434346; PMCID: PMC9008156.

- Jauregui-Renaud K, Sang FY, Gresty MA. Depersonalisation/derealisation symptoms and updating orientation in patients with vestibular disease. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2008; 79:276–83. [CrossRef]

- Staab, JP. Chronic subjective dizziness. Continuum. 2012; 18:1118–41. PubMed: 23042063. [CrossRef]

- Staab J, Eckhardt-Henn A, Horii A, Jacob R, Strupp M, Brandt T. Diagnostic criteria for persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): consensus document of the committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society. J Vestib Res. 2017 27(4):191–208. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Soper J3, Lohse CM, Eggers SDZ, Kaufman KR, McCaslin DL. Agreement between the Skull Vibration-Induced Nystagmus Test and Semicircular Canal and Otolith Asymmetry. J Am Acad Audiol. 2021 May;32(5):283-289. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Flow chart diagram according PRISMA 2020 guidelines.

Figure 1.

Flow chart diagram according PRISMA 2020 guidelines.

Figure 2.

The currently known frequency spectrum of the vestibular system. Graph summarizing the complementarity of vestibular tests, sorted by stimulation frequency (VLF: very low frequencies; LF: low frequencies; MF: middle frequencies; HF: high frequencies; VHF: very high frequencies) [

45,

47].

Figure 2.

The currently known frequency spectrum of the vestibular system. Graph summarizing the complementarity of vestibular tests, sorted by stimulation frequency (VLF: very low frequencies; LF: low frequencies; MF: middle frequencies; HF: high frequencies; VHF: very high frequencies) [

45,

47].

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of means and standard deviations for the 40-patients group at T0 (black) and T3 - after 3 months (grey) for A: Dizziness Handicap Inventory; B: Bithermal Caloric Test; C: Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus Test; D: Video Head Impulse Test anterior semicircular canal and E: Video Head Impulse Test lateral semicircular canal. The dotted line represents the boundary between normal and pathological (path.) values.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of means and standard deviations for the 40-patients group at T0 (black) and T3 - after 3 months (grey) for A: Dizziness Handicap Inventory; B: Bithermal Caloric Test; C: Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus Test; D: Video Head Impulse Test anterior semicircular canal and E: Video Head Impulse Test lateral semicircular canal. The dotted line represents the boundary between normal and pathological (path.) values.

Figure 4.

Comparison of Bithermal Caloric Test score averages at two times (T0 and T3) - lateral semicircular canal paresis percentage. A: A+D (black line) and B+C (grey line) groups; B: A+B (black line) and C+D groups (grey line).

Figure 4.

Comparison of Bithermal Caloric Test score averages at two times (T0 and T3) - lateral semicircular canal paresis percentage. A: A+D (black line) and B+C (grey line) groups; B: A+B (black line) and C+D groups (grey line).

Figure 5.

Comparison of Video Head Impulse Test gain averages for left and right VN at two times (T0 and T3) for A+D (black line) and B+C (grey line) groups. A: lateral semicircular canal; B: anterior semicircular canal.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Video Head Impulse Test gain averages for left and right VN at two times (T0 and T3) for A+D (black line) and B+C (grey line) groups. A: lateral semicircular canal; B: anterior semicircular canal.

Figure 6.

Comparison of Video Head Impulse Test gain averages for left and right VN at two times (T0 and T3) for A+B (black line) and C+D (grey line) groups. A: lateral semicircular canal; B: anterior semicircular canal.

Figure 6.

Comparison of Video Head Impulse Test gain averages for left and right VN at two times (T0 and T3) for A+B (black line) and C+D (grey line) groups. A: lateral semicircular canal; B: anterior semicircular canal.

Figure 7.

Comparison of Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus slow phase velocity averages for right mastoid (RM) and for left mastoid (LM) at two times (T0 and T3) for A+D (black line) and B+C (grey line) groups.

Figure 7.

Comparison of Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus slow phase velocity averages for right mastoid (RM) and for left mastoid (LM) at two times (T0 and T3) for A+D (black line) and B+C (grey line) groups.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus slow phase velocity averages for right mastoid (RM) and for left mastoid (LM) at two times (T0 and T3) for A+B (black line) and C+D (grey line) groups.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus slow phase velocity averages for right mastoid (RM) and for left mastoid (LM) at two times (T0 and T3) for A+B (black line) and C+D (grey line) groups.

Figure 9.

On the left: onset of NV is parameterized through DHI, spontaneous Ny, BCT, VHIT and SVINT (tests are ordered by labyrinthine analysis frequency from lowest to highest). In the centre: Evolutions of NV from the normalization of all tests with normal (A group) or pathological (B group) DHI to the persistence of pathological tests with ineffective objective instrumental compensation parameters and pathological DHI (C group) or pathological tests with effective objective instrumental compensation parameters and normal DHI (D group). On the right: Symptom profile of the various evolutionary groups, i.e. asymptomatic (A group), chronic dizziness (B and C groups) and pauci- or a-symptomatic (D group).

Figure 9.

On the left: onset of NV is parameterized through DHI, spontaneous Ny, BCT, VHIT and SVINT (tests are ordered by labyrinthine analysis frequency from lowest to highest). In the centre: Evolutions of NV from the normalization of all tests with normal (A group) or pathological (B group) DHI to the persistence of pathological tests with ineffective objective instrumental compensation parameters and pathological DHI (C group) or pathological tests with effective objective instrumental compensation parameters and normal DHI (D group). On the right: Symptom profile of the various evolutionary groups, i.e. asymptomatic (A group), chronic dizziness (B and C groups) and pauci- or a-symptomatic (D group).

Table 1.

Classification of patients based on the presence of normal or pathological instrumental tests, measured by Bithermal Caloric Test, Video Head Impulse Test, Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus Test, and the presence or absence of subjective symptoms, measured by Dizziness Handicap Inventory. For each of the four groups (A, B, C, D), the sample size is indicated. DHI: dizziness handicap inventory.

Table 1.

Classification of patients based on the presence of normal or pathological instrumental tests, measured by Bithermal Caloric Test, Video Head Impulse Test, Skull Vibration Induced Nystagmus Test, and the presence or absence of subjective symptoms, measured by Dizziness Handicap Inventory. For each of the four groups (A, B, C, D), the sample size is indicated. DHI: dizziness handicap inventory.

| |

There are no symptoms

DHI < 32 |

There are symptoms

DHI ≥ 32 |

| Normal Exams |

Recovery

→ 7 patients (17.5%) |

Chronic dizziness

→ 1 patient (2.5%) |

| |

A group |

B group |

| Pathological Exams |

Subjective compensation

but not objective recovery

→ 22 patients (55%) |

Neither subjective compensation

nor objective recovery

→ 10 patients (25%) |

| |

D group |

C group |

Table 2.

Homogeneity of Gender, Age and BMI factors for the four couples of groups.

Table 2.

Homogeneity of Gender, Age and BMI factors for the four couples of groups.

| Groups |

Gender |

Age |

BMI |

| A+D |

15M/14F |

65.10±15.17 |

25.43±3.42 |

| B+C |

6M/4F |

70.37±9.99 |

26.46±4.05 |

| A+B |

4M/4F |

63.89±18.84 |

25.12±3.54 |

| C+D |

17M/15F |

67.22±13.72 |

25.86±3.64 |

Table 3.

Comparison between the percentages of recovery of normal function at T3 vs T0 in the performed instrumental tests (BCT, VHIT, SVINT), according to for the four couples of groups. SCC: semicircular canal; BCT: bithermal caloric test; VHIT: video head impulse test; SVINT: skull vibration induced nystagmus test.

Table 3.

Comparison between the percentages of recovery of normal function at T3 vs T0 in the performed instrumental tests (BCT, VHIT, SVINT), according to for the four couples of groups. SCC: semicircular canal; BCT: bithermal caloric test; VHIT: video head impulse test; SVINT: skull vibration induced nystagmus test.

| Groups |

BCT |

VHIT

lateral SCC |

VHIT

anterior SCC |

SVINT

right mastoid |

SVINT

left mastoid |

|

A+D (DHI < 32) |

24% |

24% |

59% |

34% |

34% |

|

B+C (DHI ≥ 32) |

9% |

9% |

36% |

9% |

18% |

|

A+B (normal exams) |

100% |

100% |

100% |

87.5% |

100% |

|

C+D (pathological exams) |

0% |

0% |

44% |

12.5% |

12.5% |

Table 4.

Comparison between Eisenman et al. and Guajardo-Vergara et al. compensation criteria. It is necessary to consider the time interval between the proposals of these authors, since in twenty years vestibular instrumental diagnostic has significantly evolved.

Table 4.

Comparison between Eisenman et al. and Guajardo-Vergara et al. compensation criteria. It is necessary to consider the time interval between the proposals of these authors, since in twenty years vestibular instrumental diagnostic has significantly evolved.

| Eisenman et al. (2001) |

Guajardo-Vergara et al. (2020) |

| Spontaneous Ny ≥ 2°/sec. |

Videonystagmography: spontaneous Ny ≥ 3°/sec.; direction fixed positional Ny ≥ 4°/sec. in at least three of the four positions evaluated |

| Positional Ny persistent ≥ 3°/sec. in more than half of the 11 positions assessed, sporadic in nearly all positions, or ≥ 6°/sec. in any one position |

Caloric test: Directional preponderance ≥ 25% |

| Directional preponderance ≥ 25% |

Rotatory chair test: Sinusoidal Harmonic Acceleration Test: the asymmetry of the SPV ≥ 5°/sec. on at least three frequencies; Impulsive test: Time Constant asymmetry < 20% |

| Asymmetry of slow-component eye velocity responses, outside of established normal ranges, at two or more of the six frequencies evaluated on rotatory chair testing |

Clinical situation: Instability |

| |

Dizziness Handicap Inventory: ≥ 32 total score |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).