Submitted:

05 August 2024

Posted:

06 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

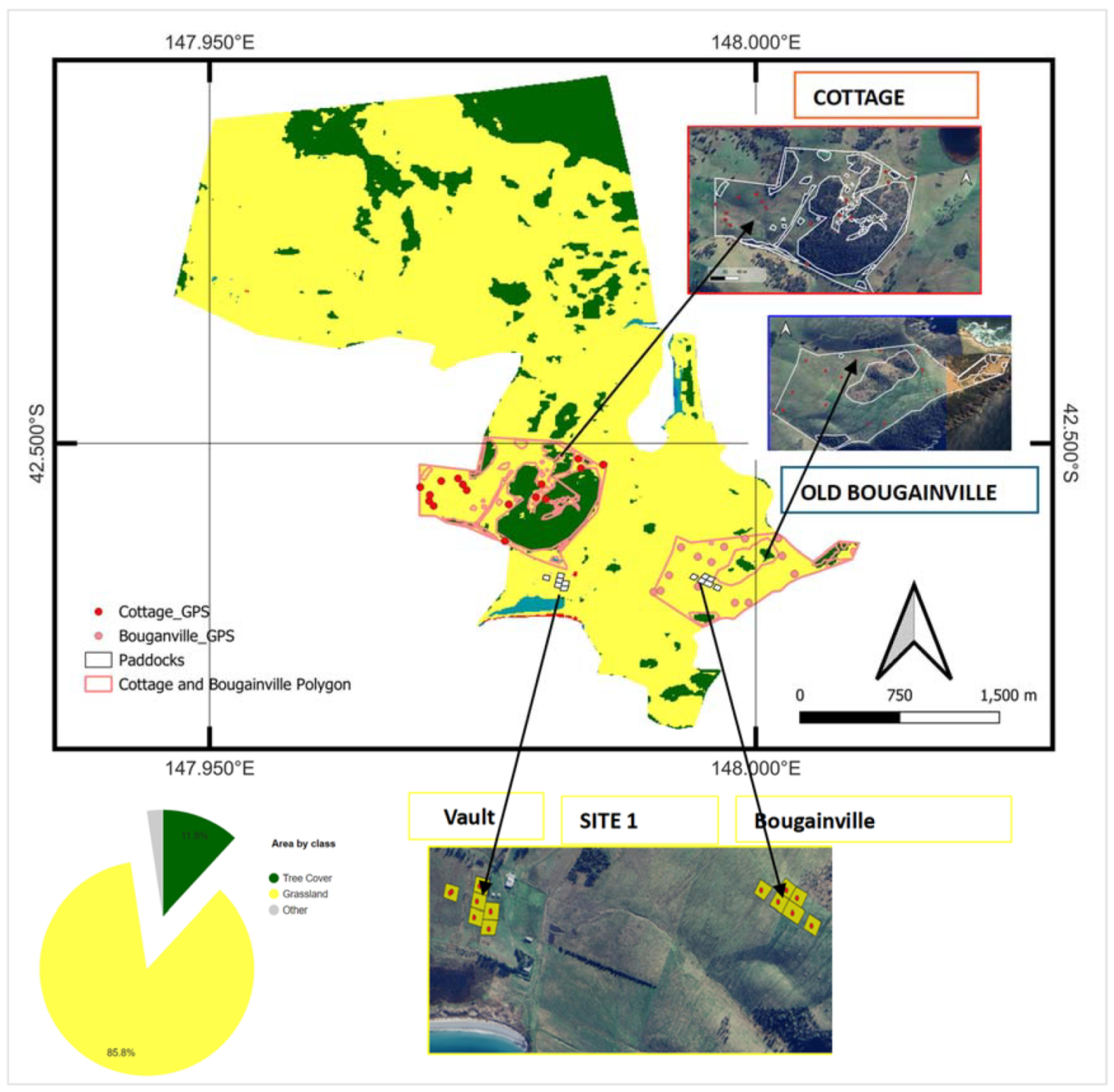

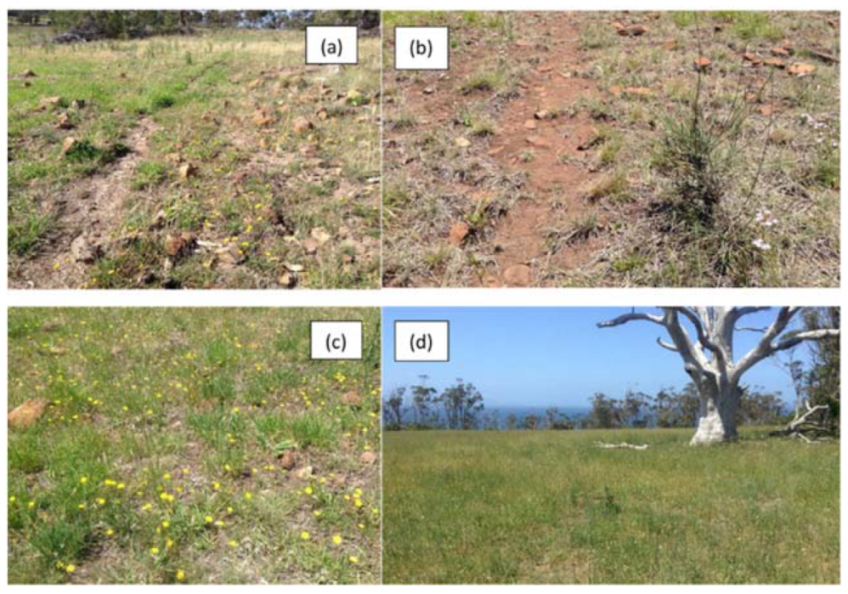

2.1. Study Area and Field Data Collection

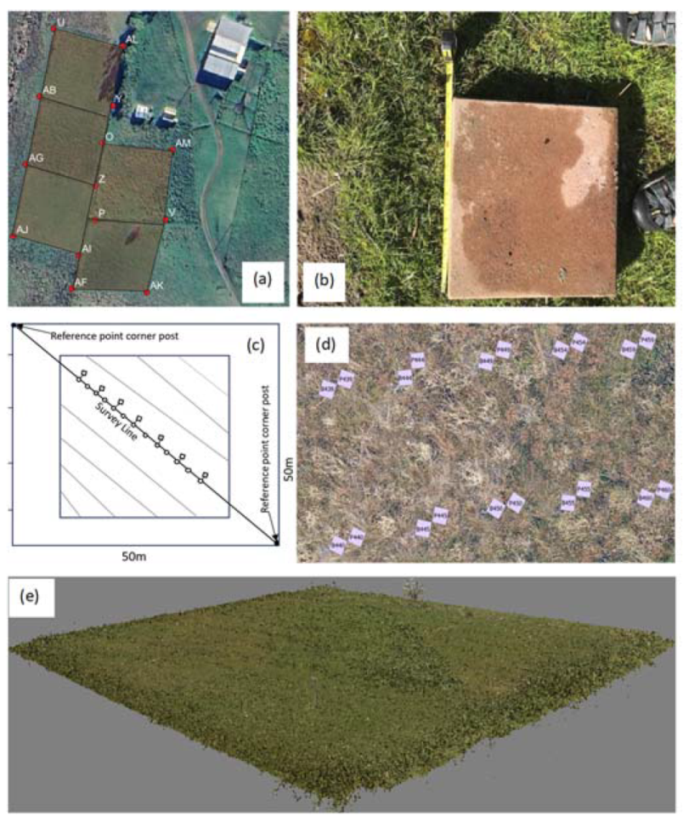

2.1.1. Bougainville and Vault Ground Sampling Protocol

2.1.2. Cottage and Old Bougainville Ground Sampling Protocol

2.5. UAS Data and Processing for Bougainville and Vault

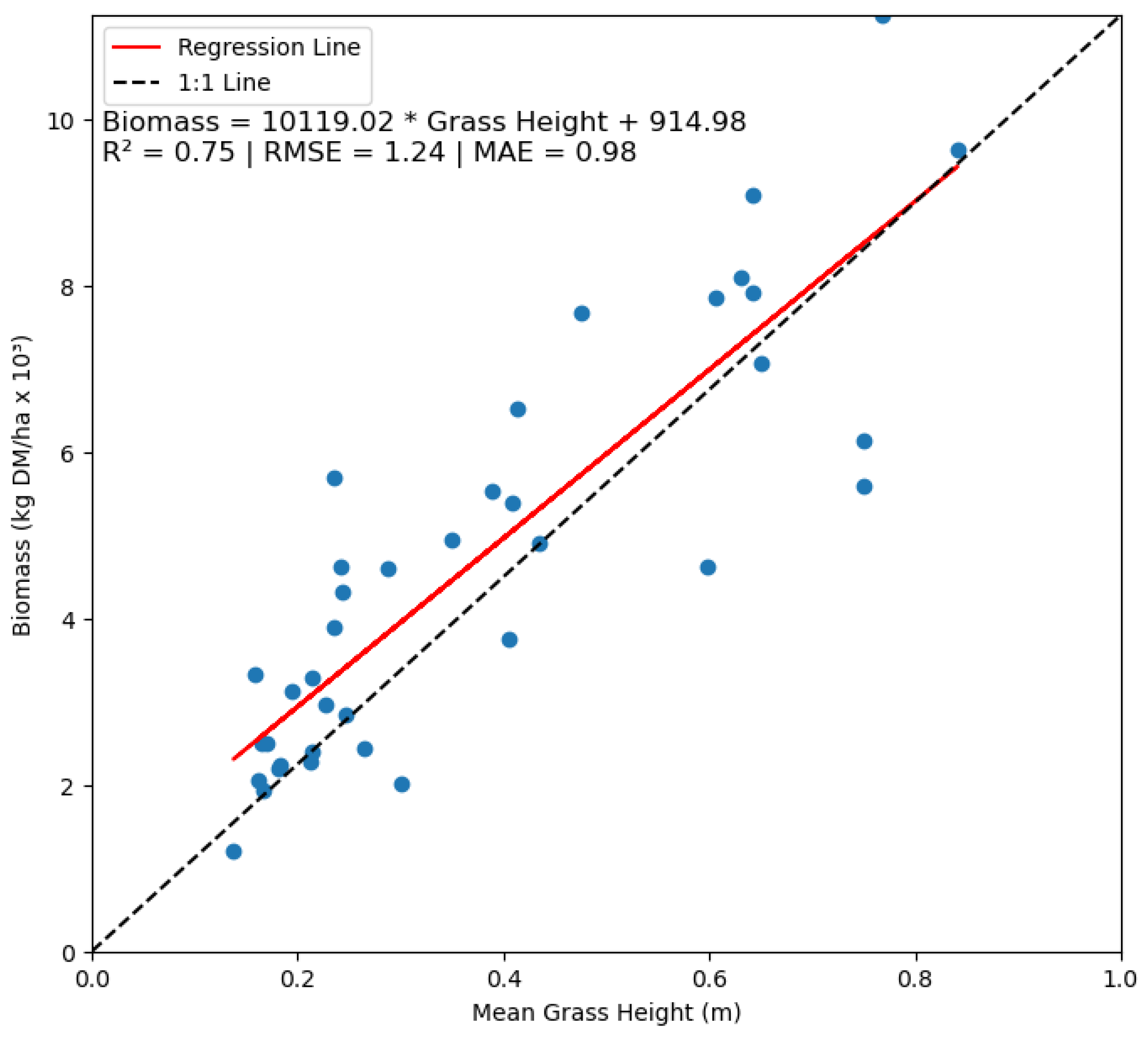

2.6. Calibration of UAS Pasture Height Changes into Biomass Using Sample Field Biomass

2.7. Sentinel-2 Data for Modelling Bougainville and Vault Biomass Using Random Forest Algorithm

2.8. Sentinel-2 Derived NDVI for Cottage and Old Bougainville

3. Results

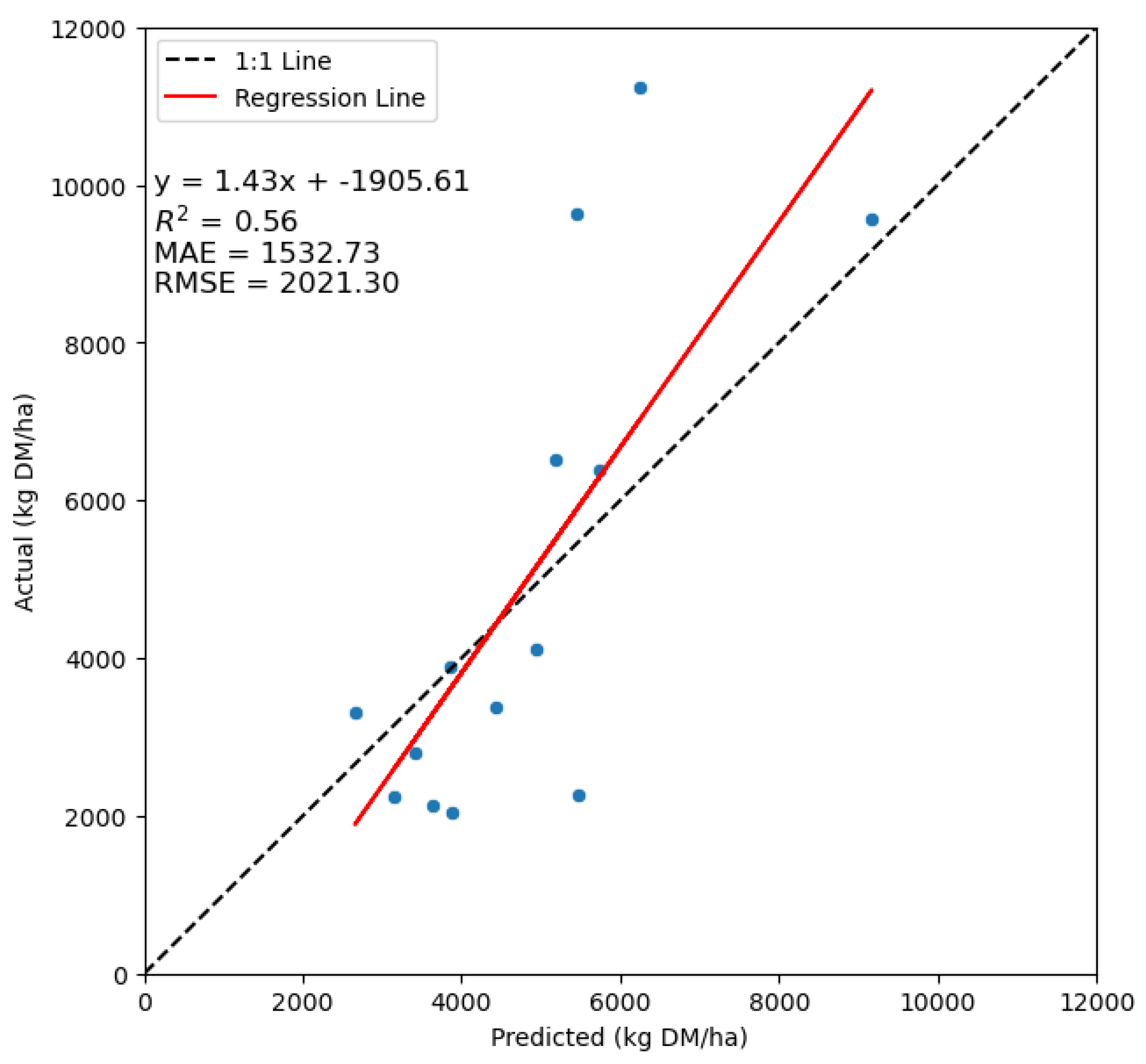

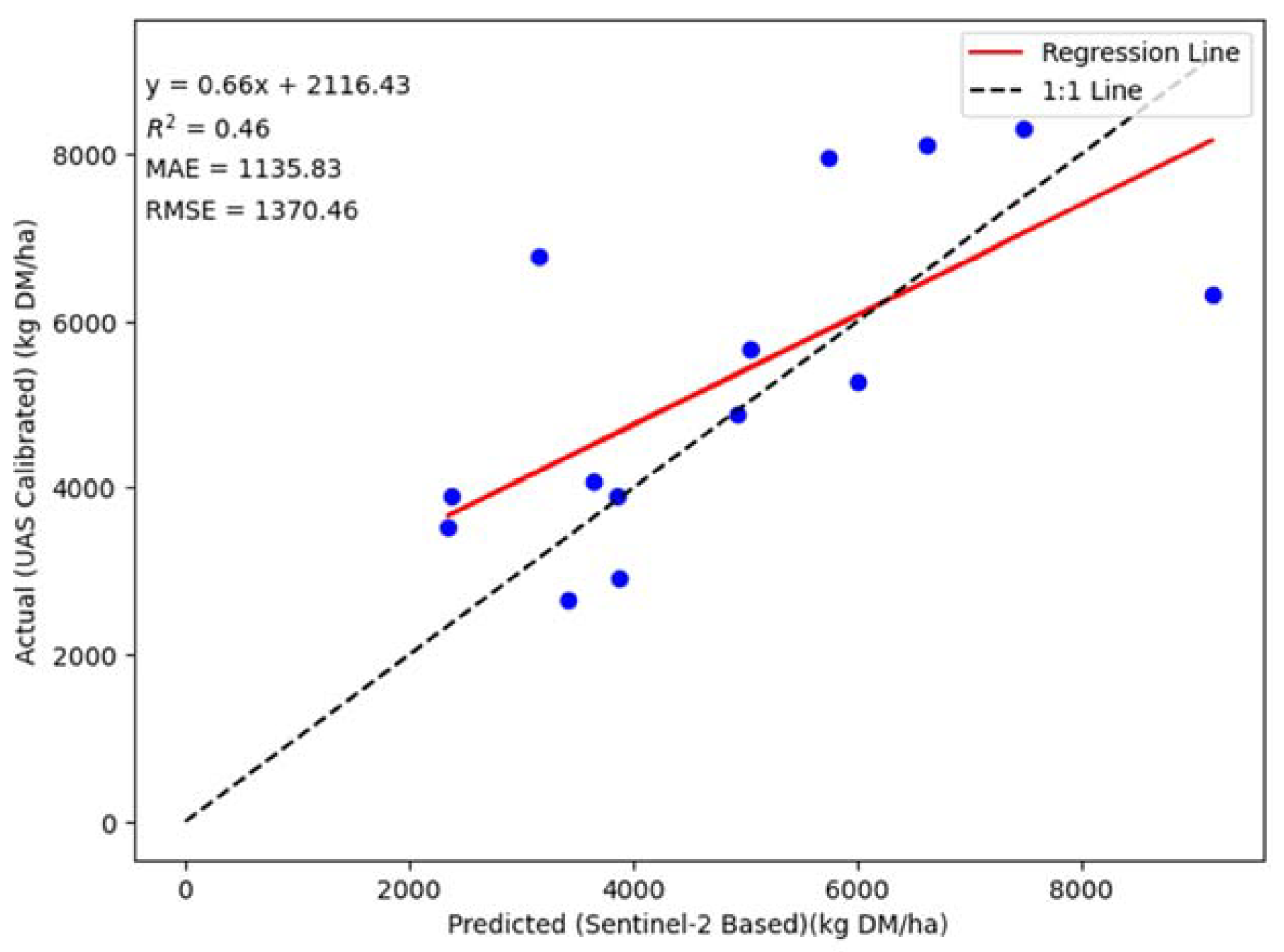

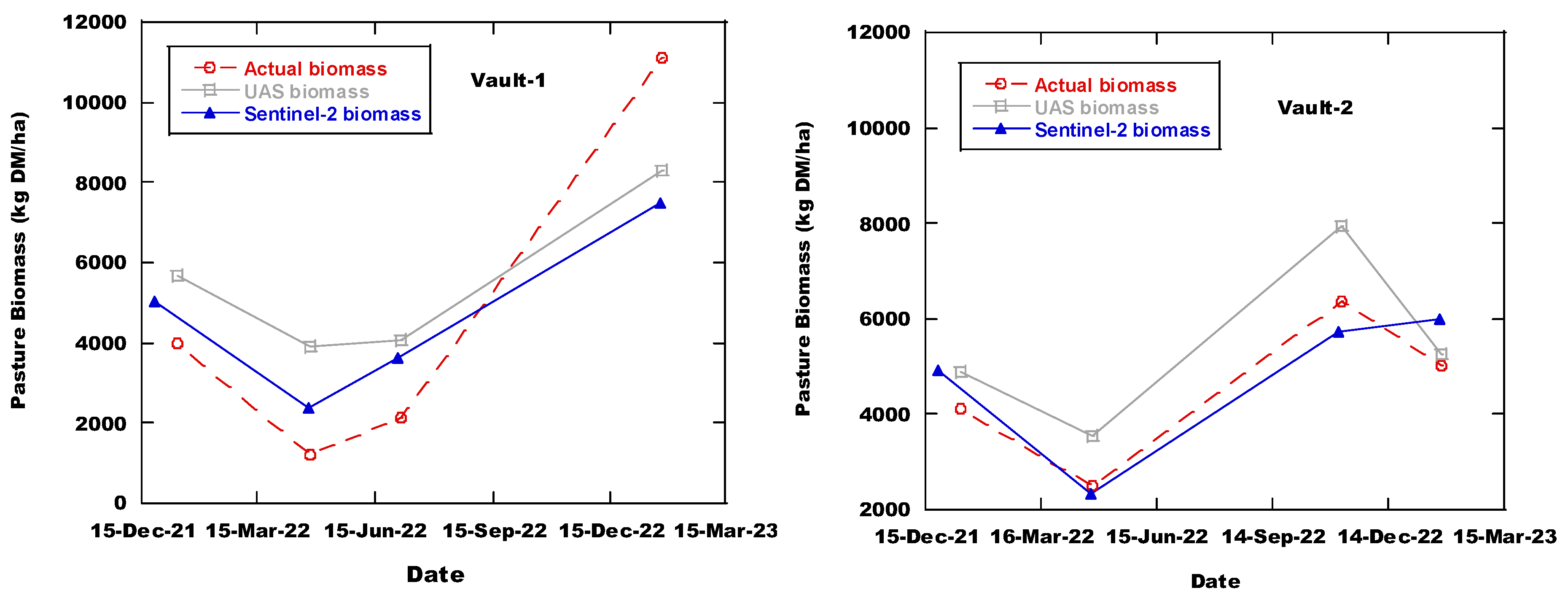

3.1. Assessment of Biomass Calibration Using Sward Height Changes and Sentinel-2 Random Forest Models

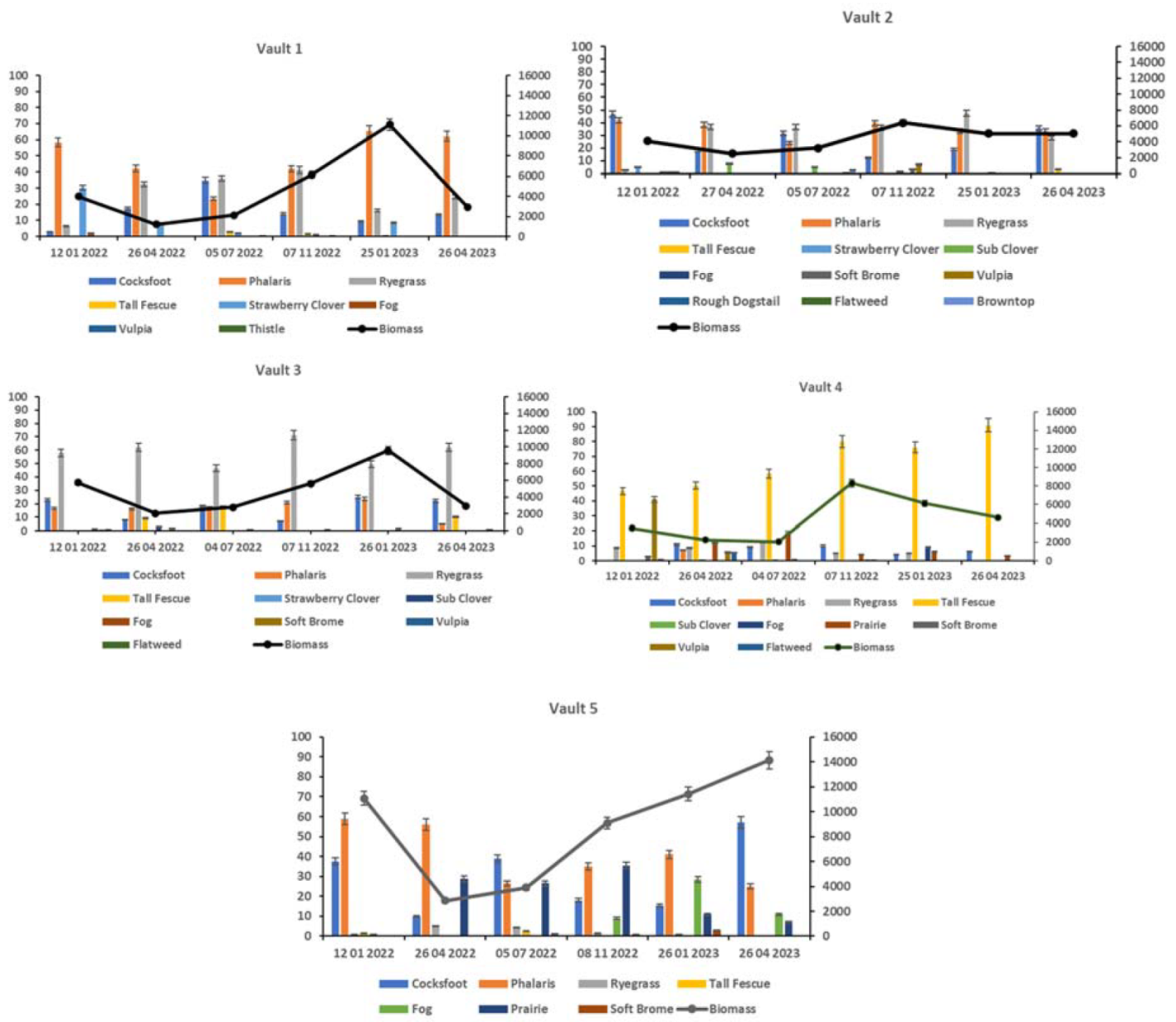

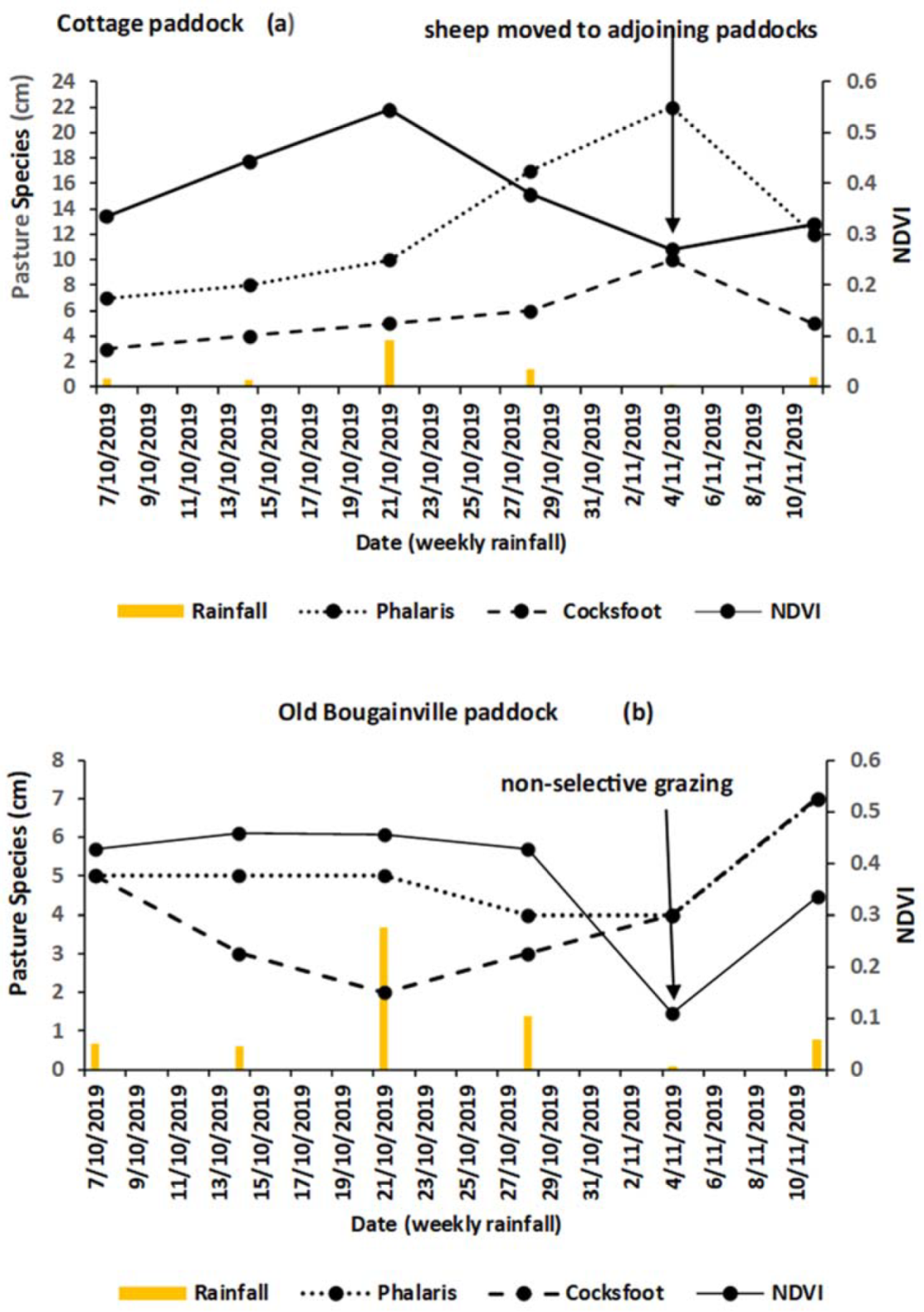

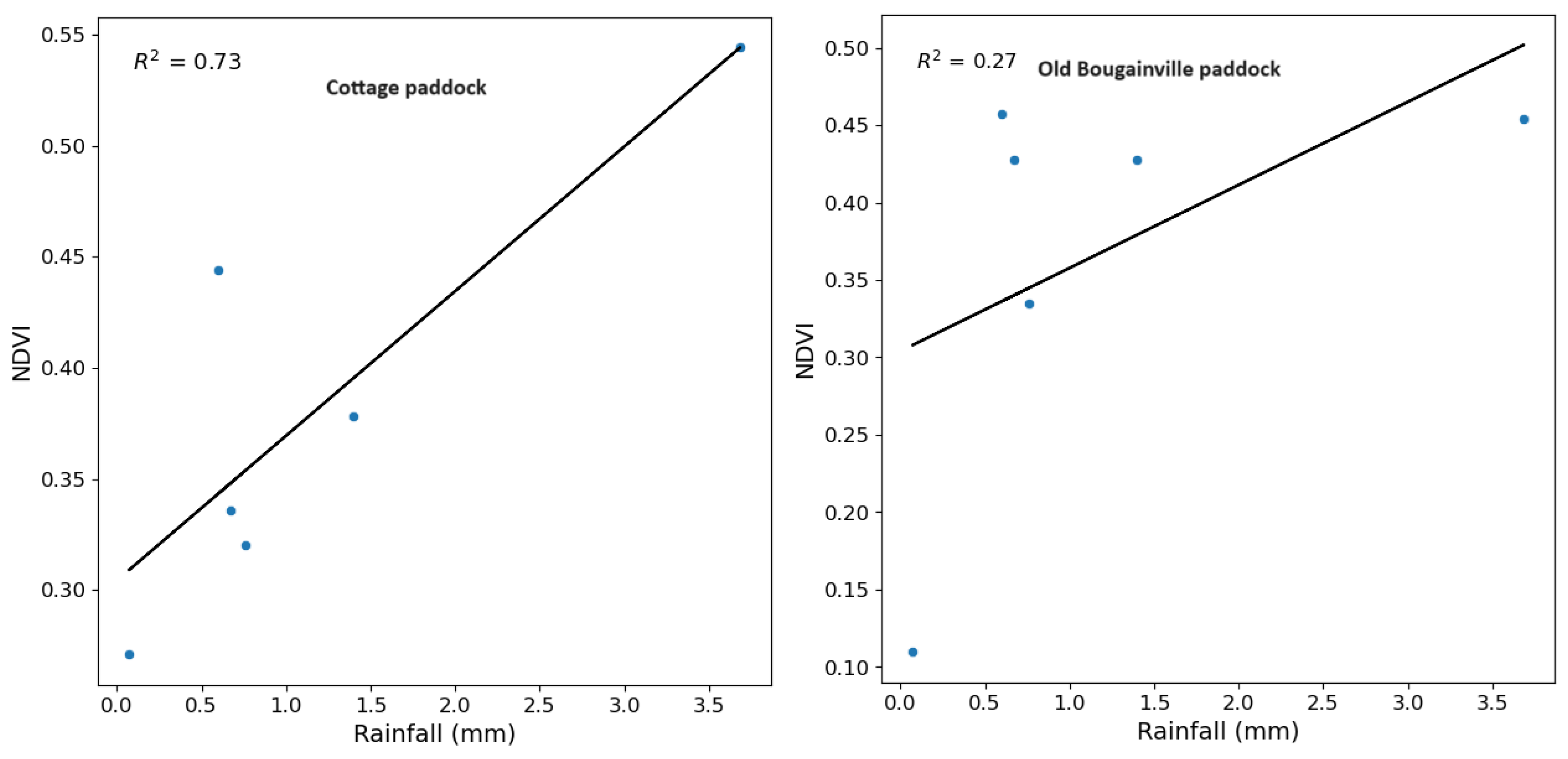

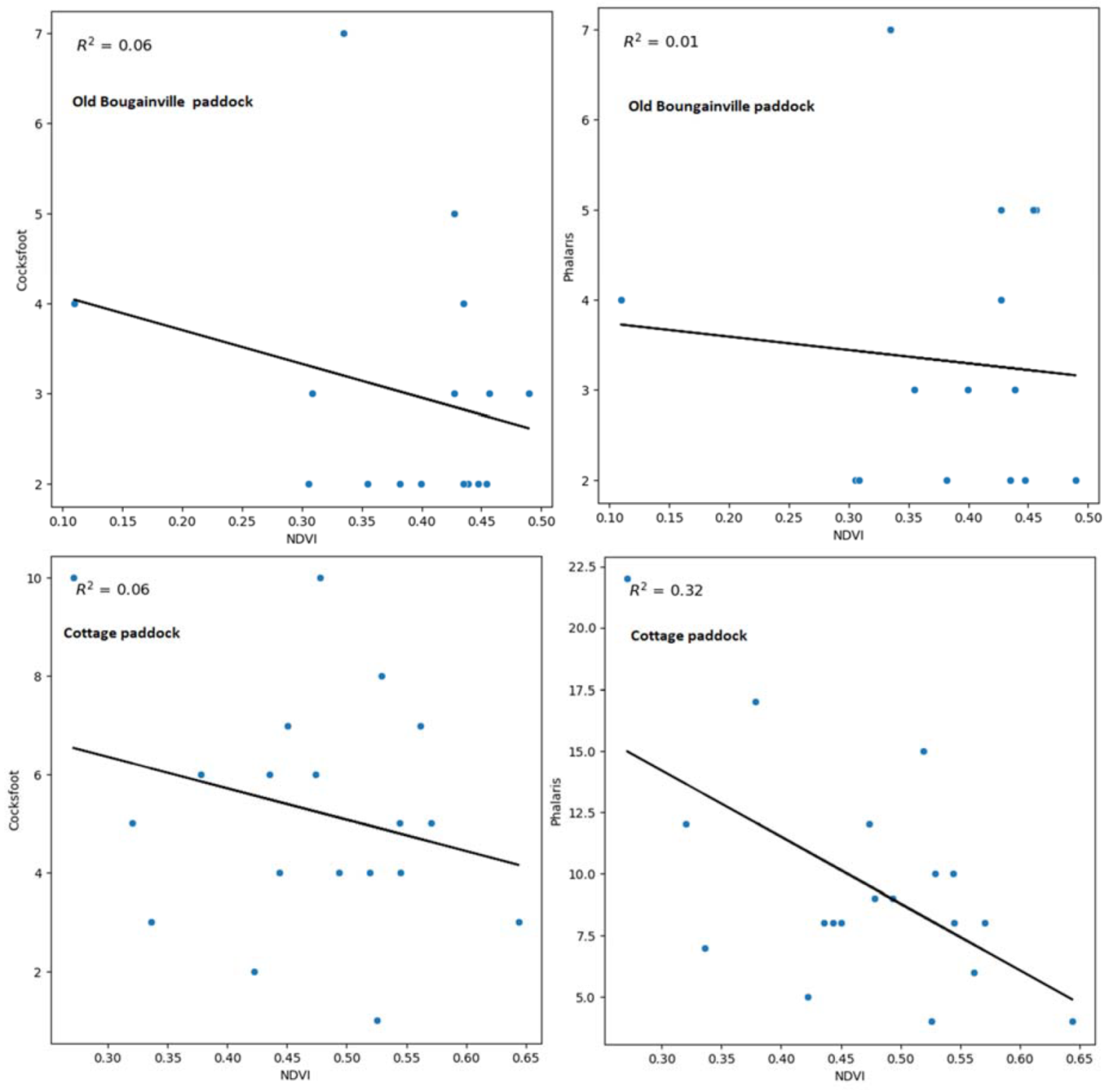

3.2. Sentinel-2 Derived NDVI for Modelling Grazing Intensity

4. Discussion

4.1. Grassland Biomass Modelling from a Change in Grass Heights Using 3D Photogrammetry and Sentinel-2 imagery with Random Forest Algorithm

4.2. Modelling Grazing Intensity and Ground Cover Productivity Using Sentinel-2 derived NDVI

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgment

Conflict of Interest

References

- Luscier, J.D.; Thompson, W.L.; Wilson, J.M.; Gorham, B.E.; Dragut, L.D. Using digital photographs and object-based image analysis to estimate percent ground cover in vegetation plots. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2006, 4, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogungbuyi, M.G.; Mohammed, C.; Ara, I.; Fischer, A.M.; Harrison, M.T. Advancing Skyborne Technologies and High-Resolution Satellites for Pasture Monitoring and Improved Management: A Review. Remote Sens. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.T.; Cullen, B.R.; Mayberry, D.E.; Cowie, A.L.; Bilotto, F.; Badgery, W.B.; Liu, K.; Davison, T.; Christie, K.M.; Muleke, A.; et al. Carbon myopia: The urgent need for integrated social, economic and environmental action in the livestock sector. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 5726–5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, E.A.; Thorburn, P.J.; Bell, L.W.; Harrison, M.T.; Biggs, J.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions From Cropping and Grazed Pastures Are Similar: A Simulation Analysis in Australia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, J.K.; Karl, J.W.; Duniway, M.; Elaksher, A. Modeling vegetation heights from high resolution stereo aerial photography: An application for broad-scale rangeland monitoring. J. Environ. Manage. 2014, 144, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunliffe, A.M.; Brazier, R.E.; Anderson, K. Ultra-fine grain landscape-scale quantification of dryland vegetation structure with drone-acquired structure-from-motion photogrammetry. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 183, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.T. Climate change benefits negated by extreme heat. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 855–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.; O’Grady, A.P.; Stitzlein, C.; Ogilvy, S.; Mendham, D.; Harrison, M.T. Improving acceptance of natural capital accounting in land use decision making: Barriers and opportunities. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 200, 107510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang-Fung-Martel, J.; Harrison, M.T.; Brown, J.N.; Rawnsley, R.; Smith, A.P.; Meinke, H. Negative relationship between dry matter intake and the temperature-humidity index with increasing heat stress in cattle: a global meta-analysis. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2021, 65, 2099–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Guo, Z.Y.; Wu, J.P.; Ye, S.F. Constructing an assessment indices system to analyze integrated regional carrying capacity in the coastal zones - A case in Nantong. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 93, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.W.; Harrison, M.T.; Kirkegaard, J.A. Dual-purpose cropping – capitalising on potential grain crop grazing to enhance mixed-farming profitability. Crop Pasture Sci. 2015, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogungbuyi, M.G.; Guerschman, J.P.; Fischer, A.M.; Crabbe, R.A.; Mohammed, C.; Scarth, P.; Tickle, P.; Whitehead, J.; Harrison, M.T. Enabling Regenerative Agriculture Using Remote Sensing and Machine Learning. Land 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahpari, S.; Allison, J.; Harrison, M.T.; Stanley, R. An Integrated Economic, Environmental and Social Approach to Agricultural Land-Use Planning. Land 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.G.; Dent, D.L.; Olsson, L.; Schaepman, M.E. Global Assessment of Land Degradation and Improvement 1 . Identification by remote sensing; Wageningen. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Kovacs, J.M. The application of small unmanned aerial systems for precision agriculture: a review. Precis. Agric. 2012, 13, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, J.K.; McClaran, M.P.; Swetnam, T.L.; Heilman, P. Estimating forage utilization with drone-based photogrammetric point clouds. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 72, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, J.K.; Karl, J.W.; van Leeuwen, W.J.D. Integrating drone imagery with existing rangeland monitoring programs. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlinszky, A.; Schroiff, A.; Kania, A.; Deák, B.; Mücke, W.; Vári, Á.; Székely, B.; Pfeifer, N. Categorizing grassland vegetation with full-waveform airborne laser scanning: A feasibility study for detecting natura 2000 habitat types. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 8056–8087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, B.; Treier, U.A.; Zlinszky, A.; Lucieer, A.; Normand, S. Detecting shrub encroachment in seminatural grasslands using UAS LiDAR. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 4876–4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.L.R.; Mathews, A.J. Assessment of Image-Based Point Cloud Products to Generate a Bare Earth Surface and Estimate Canopy Heights in a Woodland Ecosystem. Remote Sens. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsoy, P.J.; Shipley, L.A.; Rachlow, J.L.; Forbey, J.S.; Glenn, N.F.; Burgess, M.A.; Thornton, D.H. Unmanned aerial systems measure structural habitat features for wildlife across multiple scales. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetnam, T.L.; Gillan, J.K.; Sankey, T.T.; McClaran, M.P.; Nichols, M.H.; Heilman, P.; McVay, J. Considerations for Achieving Cross-Platform Point Cloud Data Fusion across Different Dryland Ecosystem Structural States. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rosa, D.; Basso, B.; Fasiolo, M.; Friedl, J.; Fulkerson, B.; Grace, P.R.; Rowlings, D.W. Predicting pasture biomass using a statistical model and machine learning algorithm implemented with remotely sensed imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, J.; Luo, J.; Zhang, X. Monitoring grazing intensity: An experiment with canopy spectra applied to satellite remote sensing. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Hess, P.S.; Thomson, A.L.; Karunaratne, S.B.; Douglas, M.L.; Wright, M.M.; Heard, J.W.; Jacobs, J.L.; Morse-McNabb, E.M.; Wales, W.J.; Auldist, M.J. Using multispectral data from an unmanned aerial system to estimate pasture depletion during grazing. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2021, 275, 114880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guerschman, J.; Shendryk, Y.; Henry, D.; Harrison, M.T. Estimating pasture biomass using sentinel-2 imagery and machine learning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macquarie Franklin Okehampton-optimising management of production and biodiversity assets, Devonport TAS. 2019.

- Ara, I.; Harrison, M.T.; Whitehead, J.; Waldner, F.; Bridle, K.; Gilfedder, L.; Marques Da Silva, J.; Marques, F.; Rawnsley, R. Modelling seasonal pasture growth and botanical composition at the paddock scale with satellite imagery. In Silico Plants 2021, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, R.; Barnes, M. Grazing management that regenerates ecosystem function and grazingland livelihoods. African J. Range \& Forage Sci. 2017, 34, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, R.; Kreuter, U. Managing Grazing to Restore Soil Health, Ecosystem Function, and Ecosystem Services. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Meteorology Climate statistics for Australian locations. Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_092027.shtml (accessed on Oct 25, 2022).

- Whalley, R.D.B.; Hardy, M.B. Measuring botanical composition of grasslands. In Field and laboratory methods for grassland and animal production research; CABI Publishing Wallingford UK, 2000; pp. 67–102.

- White, D.H.; Bowman, P.J. Dry sheep equivalents for comparing different classes of stock. Paper 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.M.; Thompson, A.N.; Curnow, M.; Oldham, C.M. Whole-farm profit and the optimum maternal liveweight profile of Merino ewe flocks lambing in winter and spring are influenced by the effects of ewe nutrition on the progeny’s survival and lifetime wool production. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2011, 51, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Wang, W.; Fawcett, R. High-quality spatial climate data-sets for Australia. Aust. Meteorol. Oceanogr. J. 58 2009, 58, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, M.R.; Robson, S.; d’Oleire-Oltmanns, S.; Niethammer, U. Optimising UAV topographic surveys processed with structure-from-motion: Ground control quality, quantity and bundle adjustment. Geomorphology 2017, 280, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.T. Whitehead, J. Ogungbuyi, M.G. Ball, P. Guerschman, J, P. Tickle, P. Leverton, C. Turner, D. Operationalising satellite and drone imagery to improve decision-making: a case study with regenerative grazing 2023, 218.

- Gillan, J.K.; Karl, J.W.; Elaksher, A.; Duniway, M.C. Fine-resolution repeat topographic surveying of dryland landscapes using UAS-based structure-from-motion photogrammetry: Assessing accuracy and precision against traditional ground-based erosion measurements. Remote Sens. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foga, S.C.; Scaramuzza, P.; Guo, S.; Zhu, Z.; Dilley, R.; Beckmann, T.; Schmidt, G.L.; Dwyer, J.L.; Hughes, M.J.; Laue, B. Cloud detection algorithm comparison and validation for operational Landsat data products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 194, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langworthy, A.D.; Rawnsley, R.P.; Freeman, M.J.; Pembleton, K.G.; Corkrey, R.; Harrison, M.T.; Lane, P.A.; Henry, D.A. Potential of summer-active temperate (C3) perennial forages to mitigate the detrimental effects of supraoptimal temperatures on summer home-grown feed production in south-eastern Australian dairying regions. Crop Pasture Sci. 2018, 69, 808–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.T.; Christie, K.M.; Rawnsley, R.P.; Eckard, R.J. Modelling pasture management and livestock genotype interventions to improve whole-farm productivity and reduce greenhouse gas emissions intensities. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2014, 54, 2018–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz de Otálora, X.; Epelde, L.; Arranz, J.; Garbisu, C.; Ruiz, R.; Mandaluniz, N. Regenerative rotational grazing management of dairy sheep increases springtime grass production and topsoil carbon storage. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punalekar, S.M.; Verhoef, A.; Quaife, T.L.; Humphries, D.; Bermingham, L.; Reynolds, C.K. Application of Sentinel-2A data for pasture biomass monitoring using a physically based radiative transfer model. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 218, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, D.C.; Harrison, M.T.; Kemmerer, E.P.; Parsons, D. Management opportunities for boosting productivity of cool-temperate dairy farms under climate change. Agric. Syst. 2015, 138, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawnsley, R.P.; Smith, A.P.; Christie, K.M.; Harrison, M.T.; Eckard, R.J. Current and future direction of nitrogen fertiliser use in Australian grazing systems. Crop Pasture Sci. 2019, 70, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Harrison, M.T.; Meinke, H.; Zhou, M. Examining the yield potential of barley near-isogenic lines using a genotype by environment by management analysis. Eur. J. Agron. 2019, 105, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.A.; Harrison, M.T.; Telfer, M.; Eckard, R. Modelled greenhouse gas emissions from beef cattle grazing irrigated leucaena in northern Australia. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2016, 56, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, B.; Dalal, R.; Harrison, M.T.; Keating, B. Creating frameworks to foster soil carbon sequestration. 2022.

- Dorrough, J.; Ash, J.; McIntyre, S. Plant responses to livestock grazing frequency in an Australian temperate grassland. Ecography (Cop.). 2004, 27, 798–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmadov, K.M.; Breckle, S.W.; Breckle, U. Effects of grazing on biodiversity, productivity, and soil erosion of alpine pastures in Tajik Mountains. In Land use change and mountain biodiversity; CRC Press, 2006; pp. 239–248.

- Blackburn, W.H. Impacts of grazing intensity and specialized grazing systems on watershed characteristics and responses. In Developing strategies for rangeland management; CRC Press, 2021; pp. 927–984.

- Allworth, M.B.; Wrigley, H.A.; Cowling, A. Fetal and lamb losses from pregnancy scanning to lamb marking in commercial sheep flocks in southern New South Wales. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2016, 57, 2060–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, D.L.; Gilbert, K.D.; Saunders, K.L. The performance of short scrotum and wether lambs born in winter or spring and run at pasture in Northern Tasmania. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1990, 30, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumhálová, J.; Kumhála, F.; Kroulík, M.; Matějková, Š. The impact of topography on soil properties and yield and the effects of weather conditions. Precis. Agric. 2011, 12, 813–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.J.; Donald, G.E.; Hyder, M.W.; Smith, R.C.G. Estimation of pasture growth rate in the south west of Western Australia from AVHRR NDVI and climate data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 93, 528–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, D.; Schaepman-Strub, G.; Ecker, K. Predicting habitat quality of protected dry grasslands using Landsat NDVI phenology. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 91, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, I.; Turner, L.; Harrison, M.T.; Monjardino, M.; deVoil, P.; Rodriguez, D. Application, adoption and opportunities for improving decision support systems in irrigated agriculture: A review. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 257, 107161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilotto, F.; Harrison, M.T.; Migliorati, M.D.A.; Christie, K.M.; Rowlings, D.W.; Grace, P.R.; Smith, A.P.; Rawnsley, R.P.; Thorburn, P.J.; Eckard, R.J. Can seasonal soil N mineralisation trends be leveraged to enhance pasture growth? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 772, 145031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.K.M.; Jackson, T.; Harrison, M.T.; Eckard, R.J. Increasing ewe genetic fecundity improves whole-farm production and reduces greenhouse gas emissions intensities: 2. Economic performance. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2014, 54, 1248–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, D.C.; Harrison, M.T.; McLean, G.; Cox, H.; Pembleton, K.G.; Dean, G.J.; Parsons, D.; do Amaral Richter, M.E.; Pengilley, G.; Hinton, S.J.; et al. Advancing a farmer decision support tool for agronomic decisions on rainfed and irrigated wheat cropping in Tasmania. Agric. Syst. 2018, 167, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).