1. Introduction

Insulin is a key hormone regulating energy homeostasis and metabolic processes within the human body, primarily affecting adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and the liver [

1]. Insulin resistance (IR), often accompanied by obesity, is a major public health problem worldwide. IR is a condition characterized by a reduced biological response of peripheral tissues to insulin. The mechanism of insulin signaling is multistep and precisely regulated at various levels. IR occurs in conjunction with numerous metabolic disorders as well as hormonal disorders such as Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and thyroid dysfunction [

2]. A common pathological feature in various forms of IR is the disruption of cellular insulin signal transmission at the molecular level, which is responsible for the development of IR. The main mechanism of insulin resistance induction is connected with impairments in insulin signal transduction, primarily through Akt and phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3) kinases, which mediate the appropriate effects in the aforementioned tissues. Furthermore, IR induces hepatic gluconeogenesis, which further increases glycemia [

3].

Numerous mechanisms have been shown to lead to the development of insulin resistance (IR). Disruption in lipid metabolism is the most common cause of IR development. However, other conditions such as obesity, chronic low-grade inflammation in various tissues, hormonal dysregulation, and other factors also impair proper signal transduction, ultimately leading to disturbances in the mechanisms of insulin action [

3].

Mitochondria play a crucial role in cell metabolism and are responsible for controlling numerous cellular processes that require ATP. It has also been shown that in humans and other organisms, IR is strongly connected with reduced mitochondrial function, manifested by a reduced mitochondrial copy number, reduced mitochondrial biogenesis, and disruption in oxidative phosphorylation. Moreover, IR leads to impaired energy production in the form of ATP, caused by reduced mitochondrial respiratory capacity observed in insulin-resistant patients, type 2 diabetic patients, and obese individuals [

4,

5]. The main consequence of reduced mitochondrial capacity is an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which is believed to be the root cause of IR development [

6].

Cinnamic acid belongs to the class of aromatic acids and is a member of the phenylpropanoid family of natural compounds. It occurs naturally in various plants and essential oils and is an important intermediate in the biosynthesis of many secondary metabolites. Cinnamic acid exhibits various biological activities, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and modulates glycogenesis and gluconeogenesis [

7,

8]. It has been observed that cinnamic acid exhibits antidiabetic effects by improving glucose tolerance and stimulating insulin secretion in rat islets and insulin action in mouse hepatocytes [

9,

10]. Moreover, our recent study evaluating the therapeutic effects of phenolic acids on insulin-resistant adipocytes (3T3-L1) showed that cinnamic acid (CA) and its derivative, 1,2-dicinnamoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (1,2-diCA-PC), restored proper insulin sensitivity in insulin-resistant adipocytes. We also noted that both CA and 1,2-diCA-PC increased the metabolic activity of mitochondria, as assessed by the MTT test [

11]. As described above, mitochondrial functionality directly translates into the functionality of the entire cell, including insulin signal transduction and thus insulin sensitivity. With the excessive supply of free fatty acids seen in obesity, there is an increase in the rate of mitochondrial metabolism, and prolonged exposure of cells to excess nutrients leads to mitochondrial overload. This mitochondrial dysfunction can contribute to chronic oxidative stress, which plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance in adipocytes [

12,

13,

14]. Restoring normal mitochondrial function can have a therapeutic effect.

In our previous paper, we reported the therapeutic effect of cinnamic acid and its derivatives on insulin-stimulated glucose uptake (ISGU) in insulin-resistant 3T3-L1 adipocytes [

11]. However, we were unable to demonstrate the possible mechanism of action through which these compounds increase insulin sensitivity, as assessed by insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. We did not observe any changes in the expression of insulin pathway genes in treated cells compared to untreated cells, suggesting that the mechanism of action does not involve the insulin pathway itself. For this reason, we further examined the possible mechanisms through which these compounds overcome insulin resistance. Considering the significant role of mitochondria in overall cell metabolism, we hypothesized that the mechanism might directly involve mitochondria. To verify this assumption, we investigated the number of mitochondria and the expression of genes encoded by mtDNA in insulin-resistant adipocytes treated with the examined substances to identify a potential mechanism underlying increased cellular sensitivity to insulin.

3. Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated the influence of cinnamic acid and its phospholipid derivative, 1,2-dicinnamoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, on mitochondrial function in insulin-resistant 3T3-L1 adipocytes by investigating the number of mitochondria and the expression of genes encoded by mtDNA.

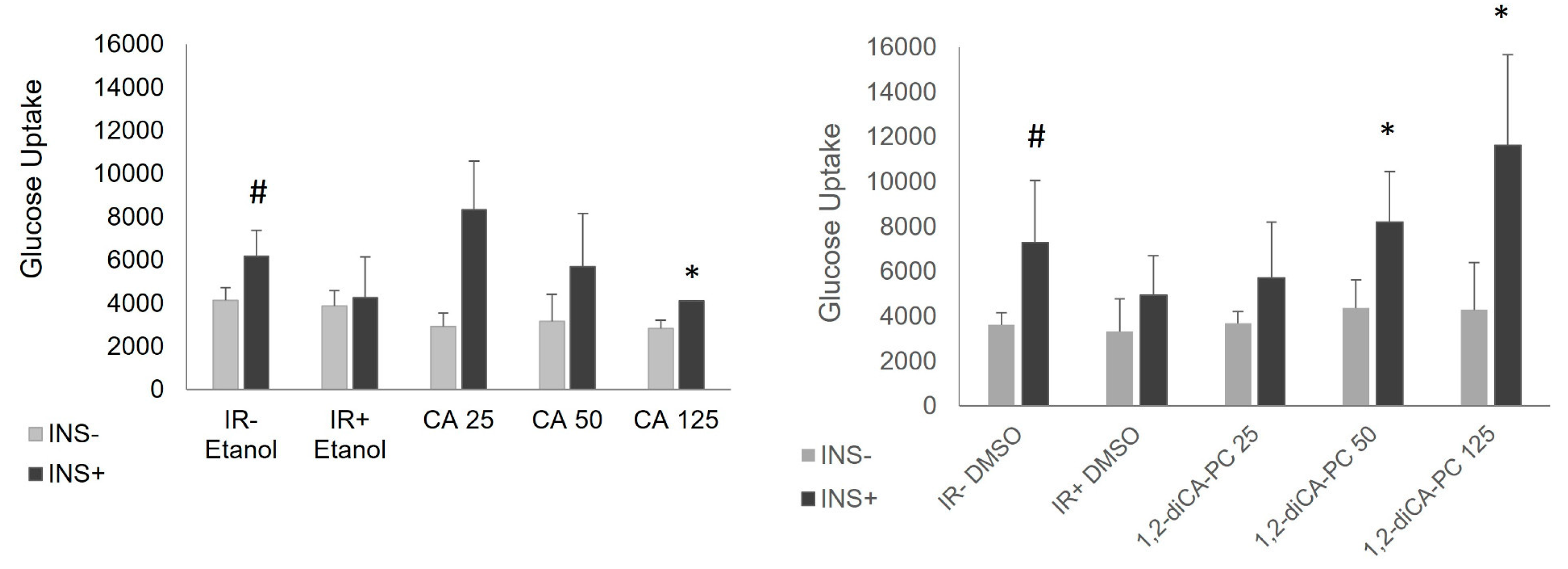

Firstly, we confirmed the successful development of insulin resistance in mature adipocytes using palmitic acid (16:0), as evidenced by measurements of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. We observed a lower glucose uptake rate in cells treated with palmitic acid in both types of insulin-resistant controls: those incubated with ethanol or DMSO, the solvents used for resuspending CA and 1,2-diCA-PC, respectively, compared to cells where insulin resistance was not induced.

Next, after incubation with the examined compounds, we performed insulin-stimulated glucose uptake measurements in insulin-resistant adipocytes. For both analyzed compounds, CA and 1,2-diCA-PC, we confirmed previous observations that CA and 1,2-diCA-PC increase insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in adipocytes with previously developed insulin resistance [

11]. It was previously reported that CA moderately increased glucose uptake in insulin-resistant adipocytes, while 1,2-diCA-PC significantly increased the glucose uptake rate, effectively doubling the level of glucose uptake in insulin-sensitive adipocytes [

11]. However, the possible mechanisms of action had not been previously revealed.

The number and size of mitochondria are crucial for the proper functioning of these organelles, and they are correlated with mitochondrial oxidative capacity and energy efficiency [

15]. A reduced content of mtDNA has been observed in blood cells of obese subjects. Studies have demonstrated a strong negative correlation between mtDNA content and BMI, as well as between mtDNA content and the amount of visceral fat [

16]. Furthermore, a reduced amount of mtDNA has also been observed in obese subjects with concomitant insulin resistance. The mtDNA/nDNA (nuclear DNA) ratio was inversely correlated with HOMA, glucose, and uric acid levels [

17,

18]. Additionally, in obese subjects with diagnosed T2D, a negative correlation was observed between mtDNA levels and BMI, fasting plasma glucose, fasting plasma insulin, LDL, and TG values in the blood [

19]. A reduction in electron transport chain activity, which correlated with a reduced number of mitochondria, was observed in the skeletal muscle of obese individuals [

20,

21].

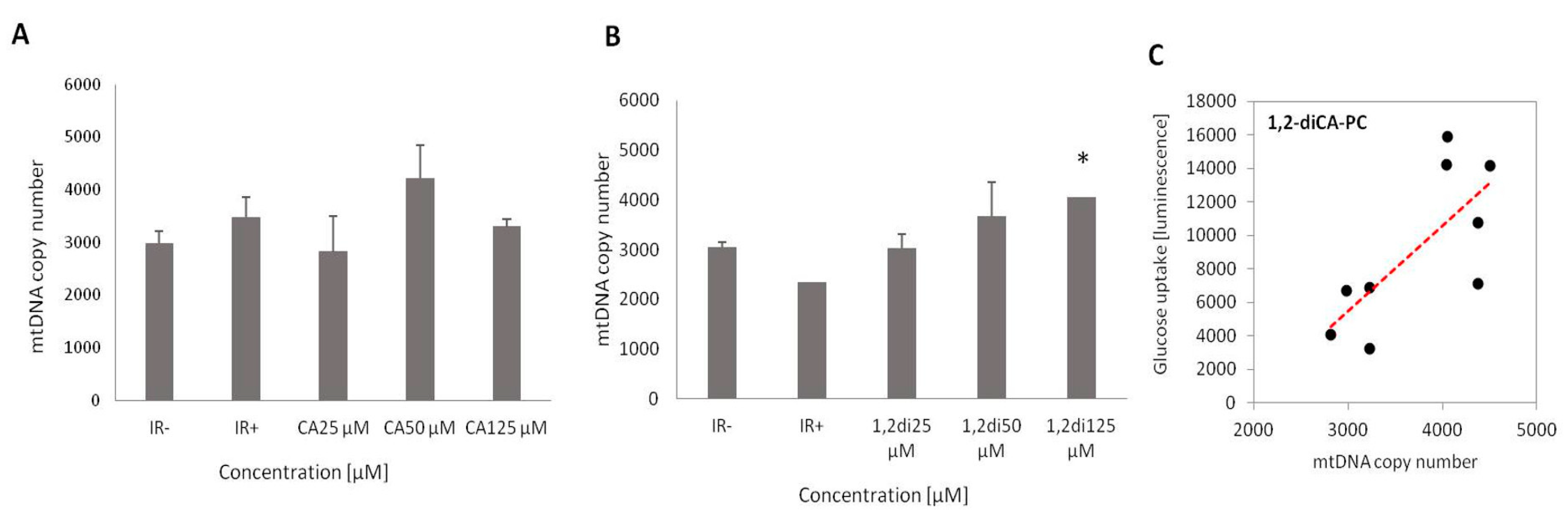

All these reports highlight the significant role of mitochondria not only in the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases but also in their interrelation. In our study, we observed a reduced number of mitochondria in insulin-resistant adipocytes compared to cells with proper insulin sensitivity. However, this decrease was observed only in cells cultured with DMSO and palmitic acid (used as the control for 1,2-diCA-PC). Slightly different results were obtained for adipocytes treated with palmitic acid and ethanol. In these cells, the number of mtDNA copies was even slightly higher in insulin-resistant adipocytes compared to adipocytes with proper insulin sensitivity.

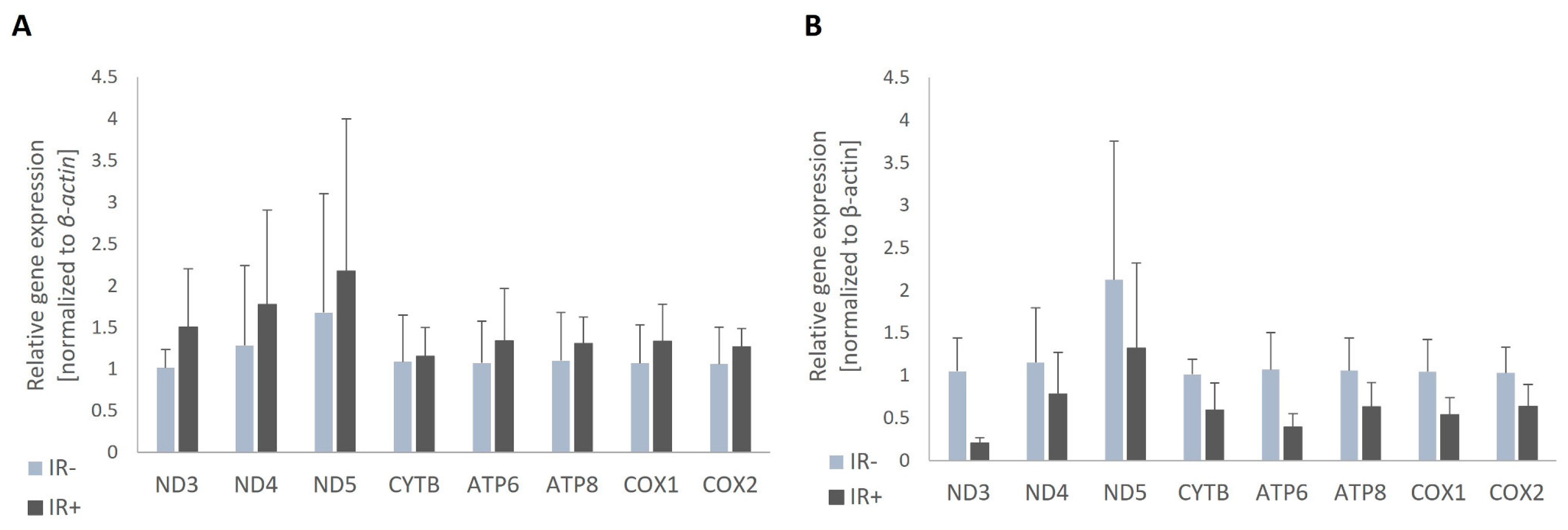

Similarly, when comparing the expression of mitochondrial-encoding genes between insulin-resistant adipocytes and adipocytes with proper insulin sensitivity, we noticed downregulation in insulin-resistant adipocytes treated with palmitic acid and DMSO. However, no changes in expression or even slightly increased expression of mitochondrial-encoding genes were observed in adipocytes co-treated with palmitic acid and ethanol, suggesting some influence of ethanol on mitochondrial biogenesis. Further research is needed to elucidate the effects of ethanol on mitochondrial biogenesis, especially given that some literature provides evidence of ethanol's negative impact on mitochondrial metabolism [

22]. It may be a matter of time, as most studies refer to chronic alcohol intake, whereas our ethanol stimulation lasted only 48 hours; thus, the early effects of ethanol might even promote mitochondrial metabolism.

Despite these observations, we can strongly conclude that our results support previous findings reported by others, confirming that mitochondrial numbers are decreased in insulin resistance, specifically in adipocytes treated with DMSO. The influence of ethanol on mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism certainly requires more in-depth research.

We observed a positive effect of the examined compounds on insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in insulin-resistant adipocytes. However, similar to previous reports, the glucose uptake stimulated by cinnamic acid (CA) was moderate across all studied concentrations [

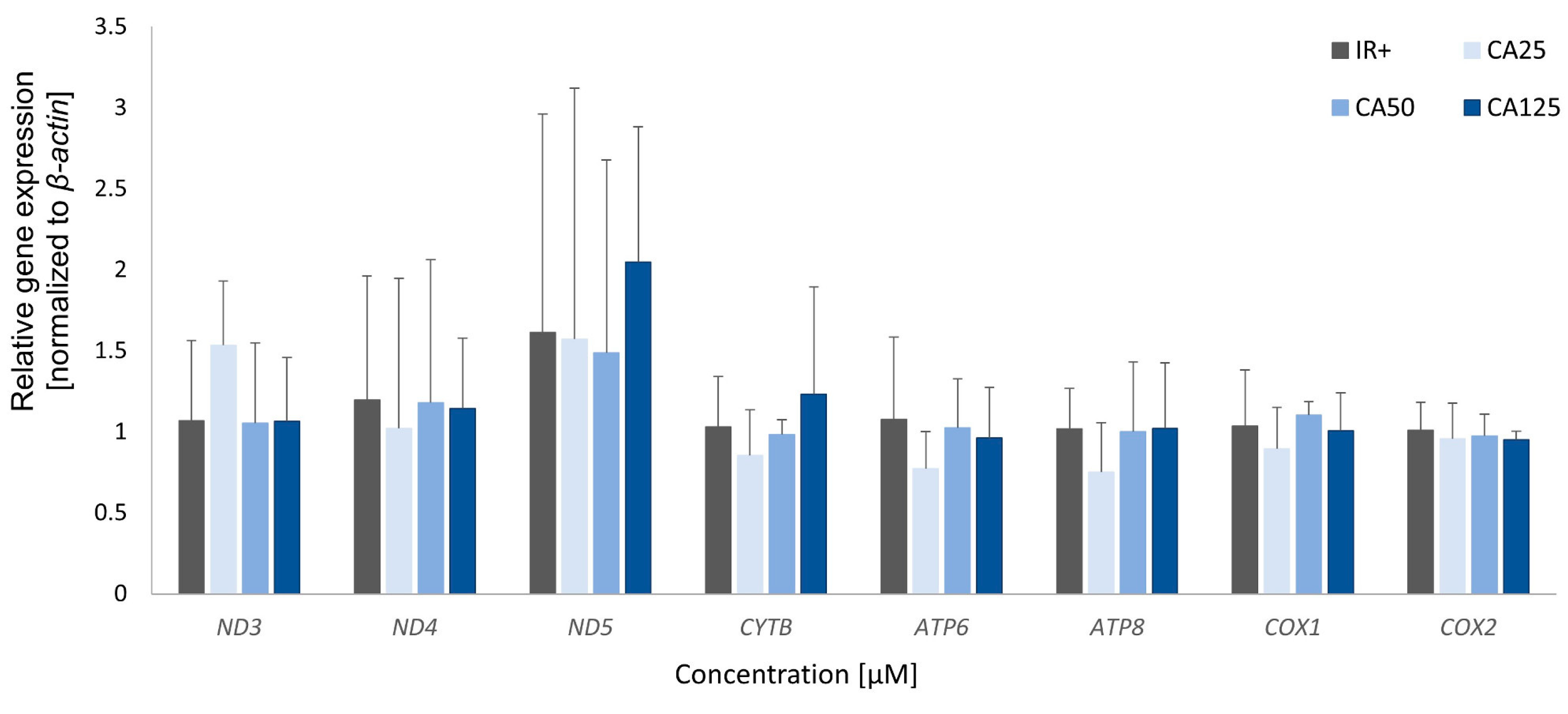

9]. In contrast, the results obtained for the derivative 1,2-dicinnamoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (1,2-diCA-PC) demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. At the highest tested concentration, 1,2-diCA-PC doubled the glucose uptake rate measured in adipocytes with proper insulin sensitivity. Similarly, we observed a dose-dependent increase in the number of mitochondria in insulin-resistant cells treated with 1,2-diCA-PC at all analyzed concentrations (25 μM, 50 μM, 125 μM) compared to control cells without 1,2-diCA-PC. Moreover, we observed a positive correlation between the number of mtDNA copies and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in adipocytes treated with 1,2-diCA-PC at the concentration of 125 μM, which supports the effect of increased mitochondrial copy number on enhancing cellular sensitivity to insulin.

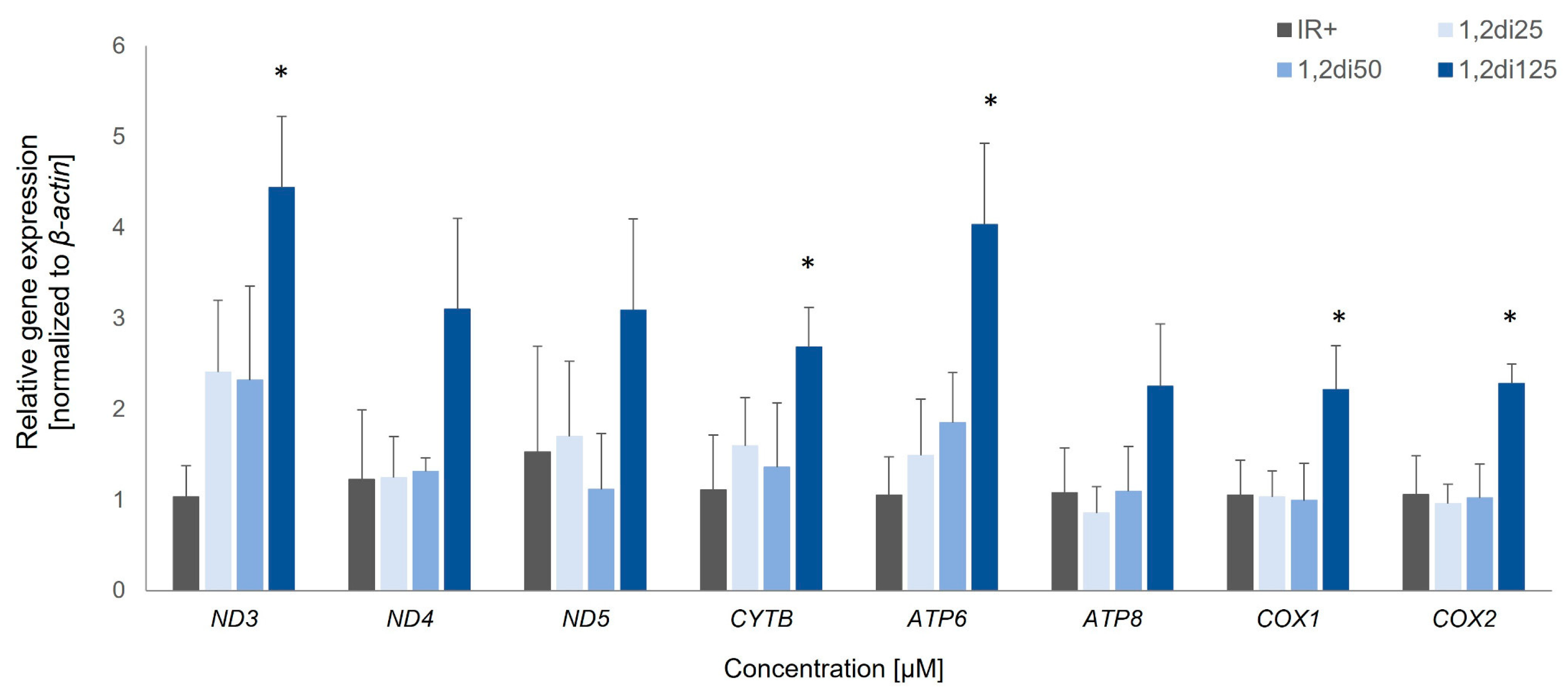

To further study the relationship between mitochondria and insulin sensitivity, we measured the expression rate of genes encoded by mtDNA in experimental cells. The mtDNA genes encode proteins that are crucial for the enzymatic activity of the electron transport chain; thus, the regulation of these genes is vital for the proper functioning of cellular metabolism. A decreased expression of Nd1 and Cox2 has been observed in cells from Zucker Diabetic Fatty (ZDF) rats, an animal model of type 2 diabetes, compared to lean animals. Moreover, the expression levels of these genes are inversely correlated with plasma glucose levels [

23]. A 50% decrease in the expression of Cox1, a subunit of mitochondrial complex IV, has been observed in insulin-resistant offspring of T2D parents [

24]. In our study, we observed a significant increase in the expression levels of all analyzed mtDNA-encoded genes in cells treated with 1,2-diCA-PC at a concentration of 125 μM, compared to control cells.

The results described above provide evidence for a potential mechanism by which 1,2-diCA-PC, at a concentration of 125 μM, reverses insulin resistance in adipocytes by enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis, as indicated by increased mtDNA copy numbers. A comprehensive understanding of 1,2-diCA-PC’s effect on reversing insulin resistance can be gained by considering the expression results, where the highest tested concentration significantly increased the expression of numerous mtDNA-encoded genes.

In 3T3-L1 adipocytes with developed insulin resistance, treatment with 1,2-diCA-PC at 125 μM led to increased glucose uptake, indicating improved cellular sensitivity to insulin. This effect was accompanied by a significant increase in the number of mitochondria and the expression levels of all analyzed mtDNA-encoded genes compared to control cells. Our studies demonstrate a strong relationship between improved cellular insulin sensitivity and an increase in both mitochondrial numbers and mtDNA gene expression. All analyzed mtDNA genes encode proteins that are components of the electron transport chain and are essential for oxidative phosphorylation. Furthermore, these results highlight the significant therapeutic potential of the cinnamic acid derivative 1,2-diCA-PC in enhancing the insulin sensitivity of adipocytes.

The results presented also have some limitations. The most significant limitation of this study is the lack of a detailed molecular mechanism explaining how 1,2-diCA-PC enhances mitochondrial biogenesis, improves insulin response, and reverses insulin resistance. Further research is needed to fully elucidate this mechanism. Additionally, it would be valuable to investigate whether similar effects are observed in other insulin-dependent cells, such as skeletal muscle or hepatocytes, and to explore if higher concentrations of 1,2-diCA-PC might produce stronger effects. Moreover, the expression of mtDNA-encoded genes could be further validated by quantifying protein levels using Western blot analysis. Despite these limitations, this study is the first to report that 1,2-diCA-PC can reverse insulin resistance by increasing mtDNA copy number and upregulating key genes involved in the enzymatic complexes of oxidative phosphorylation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Reagetns

Cinnamic acid (CA) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Saint Louis, MI, USA). The stock solution was prepared by dissolving it in ethanol and then diluting it in cell culture media.

1,2-Dicinnamoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (1,2-diCA-PC) was synthesized in the Department of Food Chemistry and Biocatalysis at Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences, following the previously reported procedure [

25,

26]. CA was esterified with the cadmium complex of sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine in the presence of 4-(N,N-dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP) as a catalyst and N,N'-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) as a coupling agent. After purification, the pure product stock solution was prepared by dissolving it in DMSO and then diluting it in cell culture media.

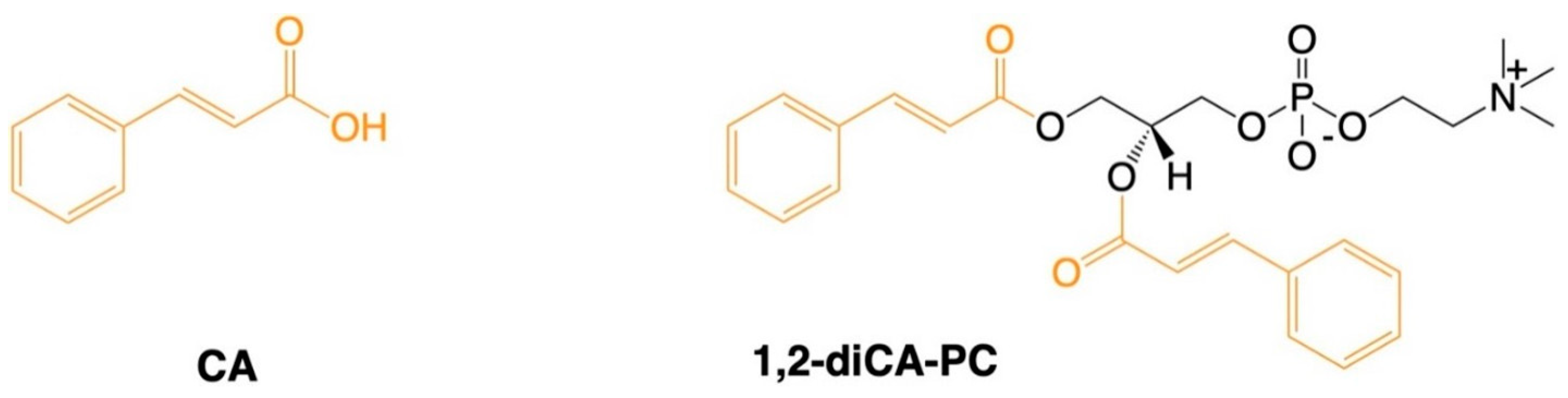

Figure 6 illustrates the chemical structures of the analyzed compounds.

4.2. The 3T3-L1 Cell Line Culturing and Differentiation

Mouse fibroblasts 3T3-L1 were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA, CL-173™). Cells were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium, Corning Incorporated, New York, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MI, USA) and antibiotics (penicillin, 50 U/mL; streptomycin, 50 µg/mL, Corning Incorporated, New York, NY, USA) in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO₂.

After achieving 100% confluence, differentiation into mature adipocytes was induced by changing the medium to DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Corning Incorporated, New York, NY, USA), antibiotics (penicillin, 50 U/mL; streptomycin, 50 µg/mL), 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (115 µg/mL), dexamethasone (390 ng/mL), and insulin (10 µg/mL). After three days, the medium was changed to DMEM with antibiotics, 10% FBS, and insulin (10 µg/mL). After an additional three days, the medium was changed to DMEM with antibiotics and 10% FBS, and the cells were further cultured for an additional two days. The cells reached maturity 8 days after the initiation of differentiation.

4.3. Insulin Resistance Induction and the Effect of Phospholipid Derivatives

Insulin resistance was induced in mature adipocytes by culturing the cells in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, antibiotics (penicillin, 50 U/mL; streptomycin, 50 µg/mL), and palmitic acid 16:0 (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MI, USA) at a concentration of 0.5 mM for 48 hours [

9].

After inducing insulin resistance, cinnamic acid (CA) and 1,2-dicinnamoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (1,2-diCA-PC) at examined concentrations (25 μM, 50 μM, 125 μM) were added to DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, antibiotics (penicillin, 50 U/mL; streptomycin, 50 µg/mL), and palmitic acid (0.5 mM). The adipocytes were then further cultured for an additional 48 hours. Palmitic acid was included in the medium to maintain insulin resistance in the adipocytes. After incubation with the specific compounds, the cells were evaluated for insulin responses using a glucose uptake test, measuring both basal glucose uptake and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. Insulin resistance in the adipocytes was assessed using the Glucose Uptake Test.

4.4. Glucose Uptake Test

The Glucose Uptake-Glo Assay (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) was performed after two and three days of incubation with cinnamic acid (CA) and 1,2-dicinnamoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (1,2-diCA-PC). The day before the glucose uptake test, cells were starved in serum-free culture medium overnight. Just before starting the experiment, the culture medium was discarded, and the cells were washed twice with PBS to remove any residual glucose. Next, a portion of the experimental cells was stimulated with 1 µM insulin in PBS for 10 minutes (INS+), while the remaining adipocytes were left unstimulated (INS-). After insulin stimulation, 10 mM of 2-deoxyglucose (2DG6P) was added to all cells, and they were further incubated for an additional 10 minutes to assess both basal glucose uptake (BGU) and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake (ISGU). The cells were then processed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Luminescence was measured using the Victor3, 1420 Multilabel Plate Reader from PerkinElmer.

4.5. DNA and RNA Extraction from Experimental and Control Cells

DNA from the cells was isolated using the phenol:chloroform method (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Total RNA from the cells was isolated using the trizol method (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). DNA and RNA concentration was measured using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA, USA).

RNA samples were treated with DNase before Reverse Transcription Reaction using RNase-Free DNase (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

4.6. Mitochindrial DNA Copy Number Quantification

Mitochondrial DNA copy number was measured using the Absolute Mouse Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number Quantification qPCR Assay Kit (ScienCell™ Research Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Procedures and calculations were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Real-Time PCR was used to quantify mtDNA and gDNA. The mtDNA copy number was calculated using the ∆∆Cq formula in reference to gDNA based on the Cq values.

4.7. cDNA Synthesis and Quantification of Gene Expression

Reverse transcription was performed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). A total of 200 ng of isolated RNA was used for cDNA synthesis. Gene expression analysis was conducted by Real-Time PCR using a SYBR Green assay (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). Primers for mtDNA-encoded genes—Nd3 (NADH dehydrogenase subunit 3), Nd4 (NADH dehydrogenase subunit 4), Nd5 (NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5), Cytb (cytochrome b), Atp6 (ATP synthase 6), Atp8 (ATP synthase 8), Cox1 (cytochrome c oxidase 1), and Cox2 (cytochrome c oxidase 2)—as well as for the nuclear DNA (nDNA)-encoded reference gene Actb (beta-actin) were manually designed (

Table 1).

The specificity of the primers was checked using Primer-BLAST (NCBI), and secondary structures were analyzed using OligoAnalyzer (Integrated DNA Technology). Prior to Real-Time PCR, the efficiency of the primers was assessed using the standard curve method. Specificity was further confirmed based on the melting curve. Only primers with efficiency values higher than R² ≥ 0.95 and confirmed specificity through the melting curve were used for gene expression studies. Relative gene expression levels, normalized to the housekeeping gene β-actin, were calculated using the delta-delta Ct (ΔΔCt) method. The fold change was determined using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) algorithm.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Office Excel 2007 and Statistica 13.1 (StatSoft). The normality of the distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Based on the results, parametric tests (Student’s t-test) were used for statistical calculations and analysis of differences between the studied groups. To assess the correlation between numerical characteristics, the correlation coefficient was used. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.