1. Introduction

The Collatz problem is one of the unsolved problems in number theory. Jeffrey also wrote and published a book on the famous Collatz conjecture as an unsolved problem [

2,

3], and Conway challenged this unsolved problem while using Fractran [

4,

5]. Subsequently, computer-based research continued, and numerous scholars tackled this difficult problem with interest [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The major difference between this paper and other papers on the Collatz conjecture is that the regularity is calculated by hand, without using any computer. Thus, we assume that the computational complexity can be drastically reduced. Also, it is impossible to show all numbers by computer. This is because numbers are not finite. Therefore, in this paper, we proved the Collatz conjecture by a very simple method using regularity and limits. The proof method described in this paper can be effectively used to provide clues to solving many unsolved problems.

2. Methods

In solving Collatz’s conjecture, we first took into consideration the importance of using the fact that all integers are represented by an+1, an+2...an+(a-1). If n is even, then n = 2m, and if n is odd, then n = 2m+1 (m ≥ 0).

First,

(1) N = 6n

(A) n= 2m (when n is even)

When N = 6n and n is even, since N = even, using 6n = 6 and 2m = 12m, we can express the next number as 12m/2, which is 6m. If we use the fact that m≥1, then when n is even (n=2m) and some positive integer is N=6n, the next number of N must satisfy N=6n’. (n≠n’)

(B) n = 2m+1 (when n is odd)

If N = 6n and n is odd, then the next number is N = even.

(6n = 6・(2m+1) =12m+6)

Thus, the following number is (12m+6)/2 = 6m+3, which always satisfies N=6n’+3. (n≠n’)

This can be summarized and written as

Table 1.

(2) N = 6n+1

(A) n= 2m (when n is even)

If N = 6n and n is even, then N is odd; using N’=3N+1, the next integer is 3・(6n+1)+1 = 3・(6(2m)+1)+1 and the next number can be expressed as 36m+4 = 6・(6m)+4. Here, using the fact that m≥1, if n is even (n=2m) and some positive integer is N=6n, the next number of N will always satisfy N=6・(6m)+4=6n’+4 (n≠n’).

(B) n = 2m+1 (when n is odd)

N = 6n where n is odd as in A when n is odd. Therefore,

Using N’=3N+1, the next integer can be expressed as 3・(6n+1)+1 = 3・(6(2m+1)+1)+1 and the next number can be expressed as 36m+22= 6・(6m+3)+4=6n’+4 (n≠n’).

This can be summarized and written as in

Table 2.

(3) N = 6n+2

(A) n= 2m (when n is even)

If N = 6n+2 and n is even, then N is even; using N’=N/2, the next integer is N’ = (6(2m)+2)/2 = 6m+1, and the next number N’ can be expressed by 6⋅m+1. If we use the fact that m≥1, then if n is even (n=2m) and some positive integer is N=6n+2, the next number N’ of N must satisfy N=6⋅m+1=6n’+1 (n≠n’).

(B) n = 2m+1 (when n is odd)

N = 6n+2=6(2m+1) +2 = 12m+8 where n is odd, as in (A).

Thus, using N’=N/2, the next integer is (12m+8)/2 = 6m+4, and the following number

N’= 6・(m)+4=6n’+4 (n≠n’).

This can be summarized and written as

Table 3.

3. Results

Calculating similarly for N = 6n+3, 6n+4, and 6n+5, the regularity is determined as shown in

Table 4.

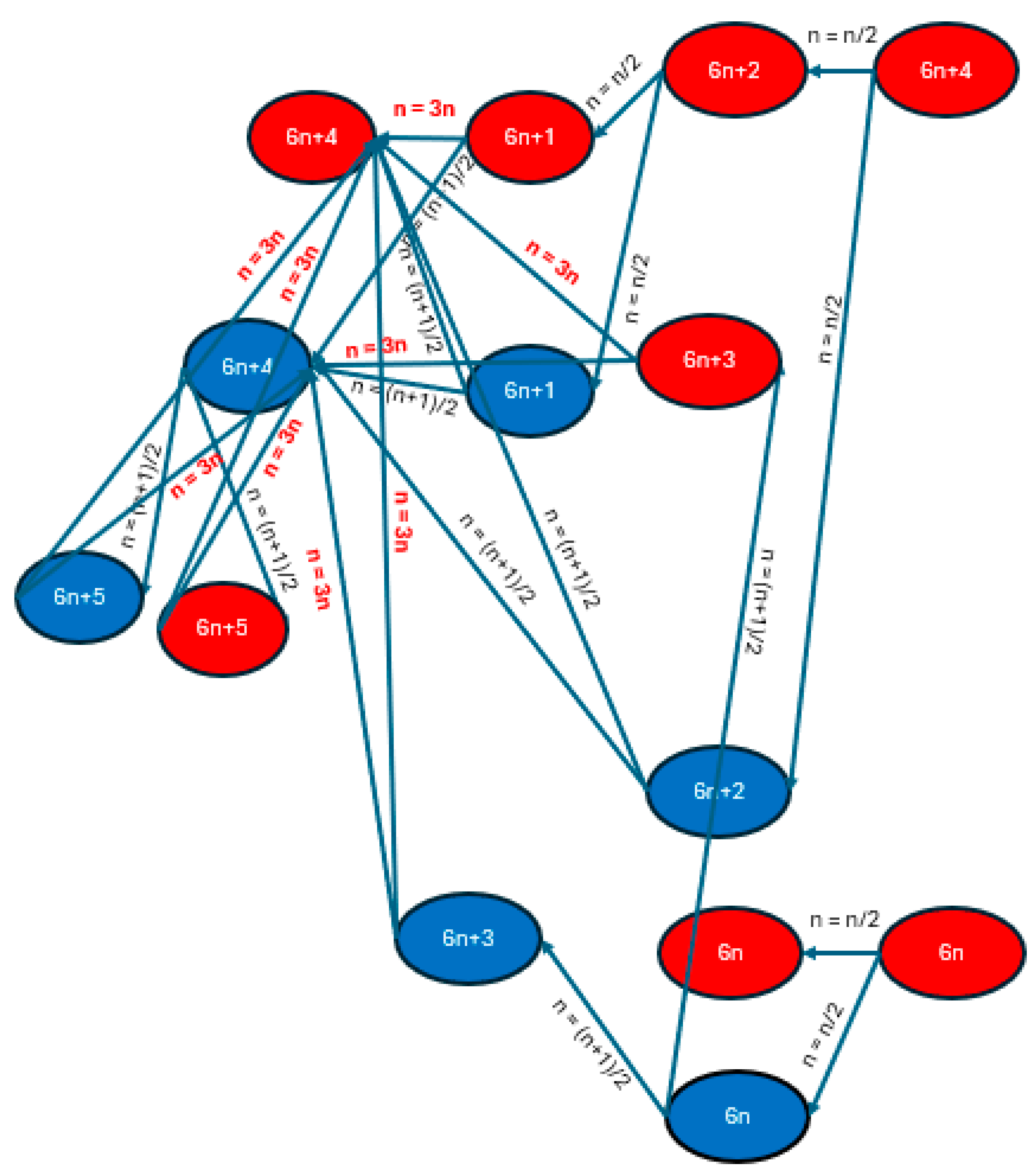

We can see the rules in

Table 4 are repeated. Now, when all the numbers are covered, we can depict them as in

Figure 1. From

Figure 1, it is obvious that n will eventually always be in the 1,4,2,1 loop.

Now, suppose N is a very large number, whether it converges to 1, 4, 2, 1,

From 6n + 4 to the next 6n + 4, if n is always smaller, the proof is possible according to the loop rule.

When in a loop,

Even with the smallest coefficient, n’ = 1/2x in the 6n+4→6n+4 step; n’ = 1/2x in the 6n+2→6n+1 step; and n’ = 1/2x in the 6n+2→6n+1 step. Thus, the convergence is at least 1/4 times faster. Note that when n=2m+1, the convergence speed is faster. On the other hand, when 6n+1 is an odd number, n’ = 3n+1 times. an is the initial value of the loop, Collatz’s expectation converges to n = 0 (n = 1,4,2,1...) as in equation (1).

From Equation (1), once in a loop, it always converges to n = 0. Therefore, it is considered to converge at loops of 4, 2, and 1.

4. Discussion

Conventionally, there was a section in which the Collatz conjecture attempted to make its mathematical sense by performing all the calculations. In the present paper, however, we have tried to classify the numbers very simply up to N = 6n, 6n+1...6n+5, and have concentrated on finding the regularities of these numbers. As a result, we were able to prove that every number always eventually enters a loop cycle and takes the form 6n+1, 6n+4, 6n+2, 6n+1. The final convergence of n to 0 was proved by using the limit to skip n to ∞, but a more rigorous proof is being considered in the future.

5. Conclusions

Regularities existed in Collatz ‘s conjecture. By extending the initial values of Collatz’s conjecture from 6n+1 to 6n+5, usually referred to as the 3n+1 problem, this paper shows that for all numbers, as expected by Collatz, it eventually falls into a loop and converges to 1, 4, 2, 1 with n = 0. Since this study uses a simplified method, it is possible to communicate the solution not only to experts but also to the public. The authors believe that if they can suggest that Collatz’s conjecture was correct, then Collatz’s hope will be fulfilled.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H. S.; methodology, H. S.; software, H. S..; validation, H.S.; project administration, H.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No ethical approval is required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Oliveira e Silva T (1999) Maximum excursion and stopping time record-holders for the 3x+1 problem: computational results. Math Comput 68(225):371 -384. [CrossRef]

- Lagarias JC (2003) The 3x+1 problem: an annotated bibliography (1963-1999) (sorted by author). arXiv:mathmath/0309224.

- Lagarias JC (2006) The 3x+1 problem: an annotated bibliography, II (2000-2009). arXiv:math/0608208.

- Conway JH (1972) Unpredictable iterations. Proceedings of the 1972 Number Theory Conference.

- Conway, J.H. (1987). FRACTRAN: A Simple Universal Programming Language for Arithmetic. in: Cover, T.M., Gopinath, B. (eds) Open Problems in Communication and Computation. Springer, New York, NY. Mol LD (2008) Tag systems and Collatz-like functions. Theor Comput Sci 390(1): 92-101. 92-101. 10.1016/j.tcs.2007.10.020. [CrossRef]

- Lagarias JC (1985) The 3x + 1 problem and its generalizations. Am Math Mon 92(1):3-23. [CrossRef]

- Honda T, Ito Y, Nakano K (2017) GPU-accelerated exhaustive verification of the Collatz conjecture. Int J Netw Comput 7(1):69-85.

- Oliveira e Silva T (2010) Empirical verification of the 3x+1 and related conjectures. In: Lagarias JC (ed) The ultimate challenge: The 3x+1 problem. American Mathematical Society, Providence, pp 189-207.

- Leavens GT, Vermeulen M (1992) 3x+1 search programs. Comput Math Appl 24(11):79-99. [CrossRef]

- Shalom Eliahou, The $3x+1$ problem: new lower bounds on nontrivial cycle lengths, Discrete Math. 118 (1993), no. 1-3, 45-56. MR 1230053. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Lagarias and A. Weiss, The $3x+1$ problem: two stochastic models, Ann. Appl. Probab. 2 (1992), no. 1, 229-261. MR 1143401. [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, C. Lagarias, The $3x+1$ problem and its generalizations, Amer. Math. Monthly 92 (1985), no. 1, 3-23. MR 777565. [CrossRef]

- Gary, T. Leavens and Mike Vermeulen, $3x+1$ search programs, Comput. Math. Appl. 24 (1992), no. 11, 79-99. MR 1186722. [CrossRef]

- American Mathematical Society - 201 Charles Street Providence, Rhode Island 02904-2213.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).