Submitted:

29 July 2024

Posted:

30 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Plant Material

2.2.1. Pomegranate Polyphenols Extraction and Chemical Characterization

2.3. Human Aβ1-42 Preparation

2.4. Cell Culture

2.5. Cell Viability Measurement

2.6. Cell Apoptosis Assay

2.7. Measurement of Intracellular ROS

2.8. Lipid Peroxidation Assay

2.9. M1/M2 Polarization of Microglia Cells and Systemic Macrophages

2.10. The Assessment of Interleukin 1-Beta (IL-1β) and Interleukin-10 (IL-10) Proteins Expression

2.11. Tau-Phosphorylation at Threonine 181

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phytochemical Analysis

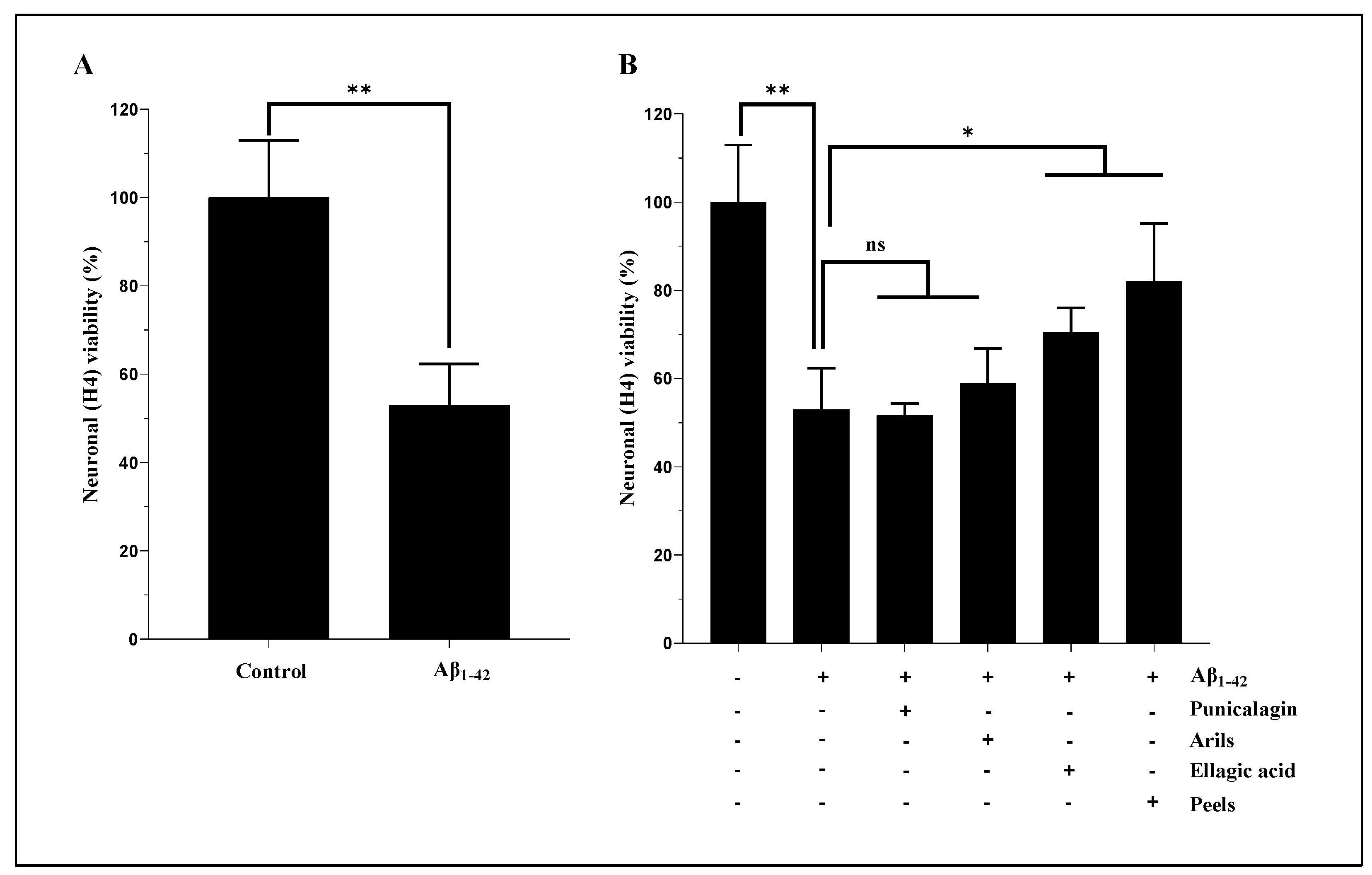

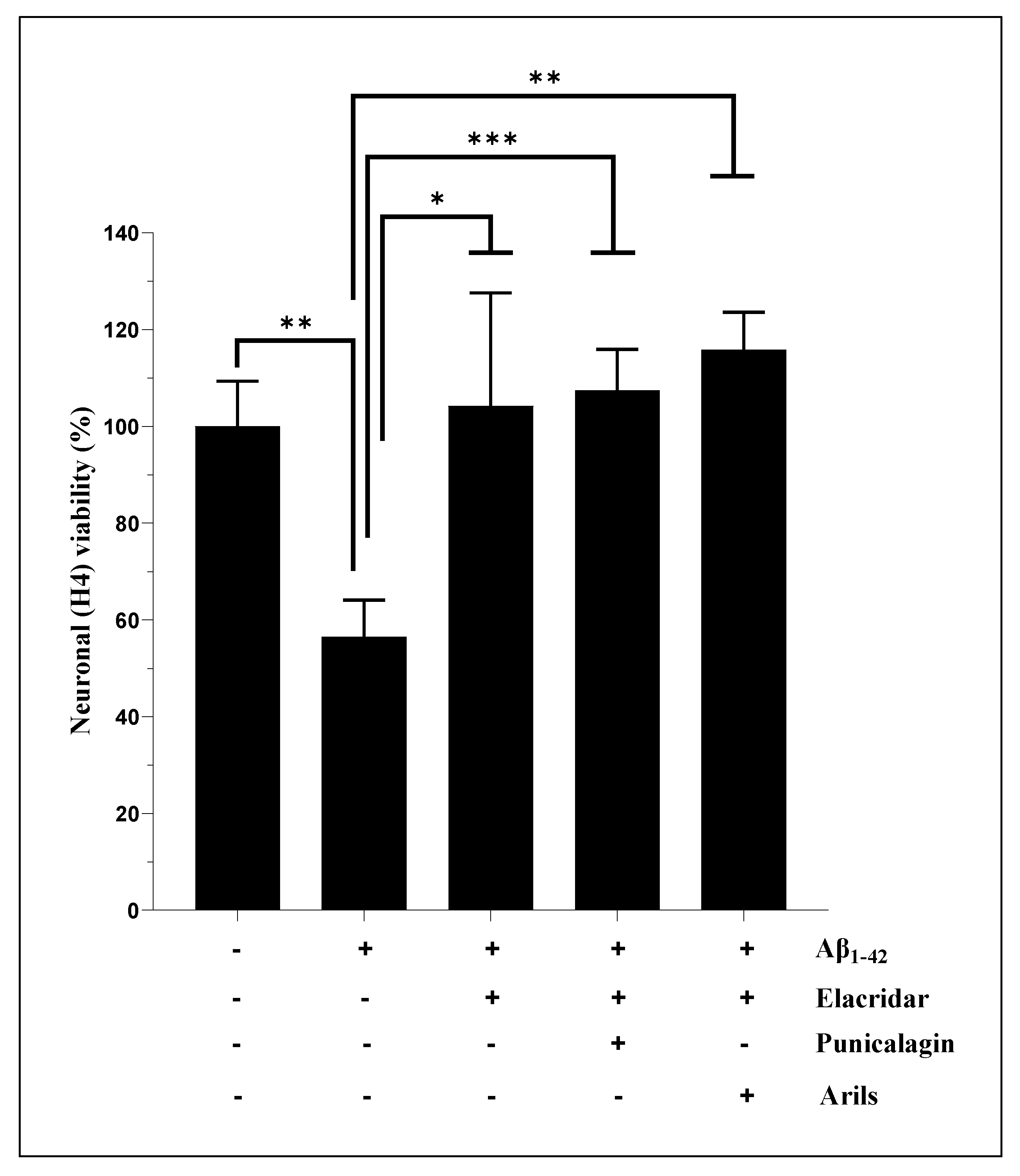

3.2. Cell Viability Measurement

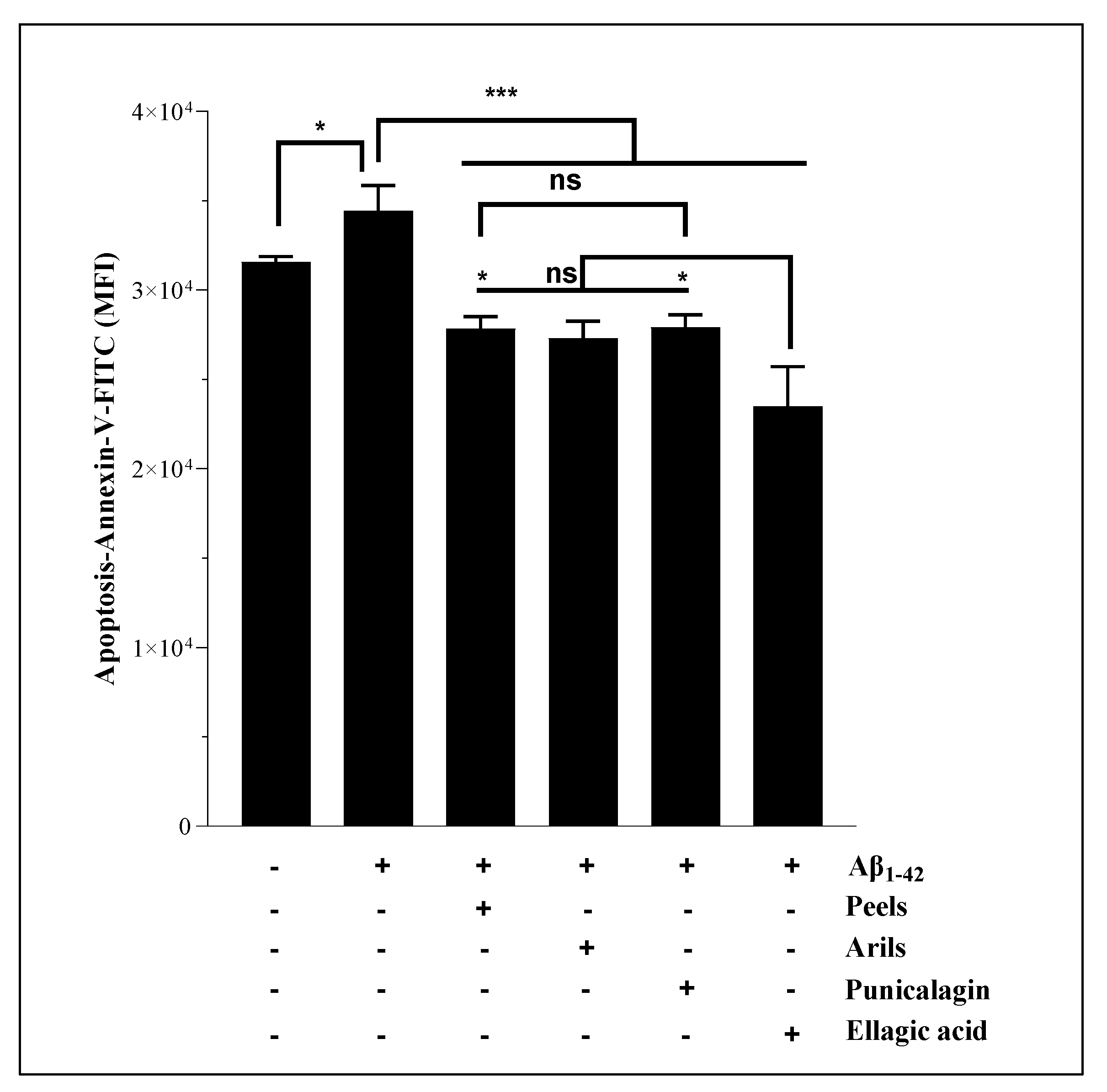

3.3. Human Aβ1-42 Induces Apoptosis of H4 Neurons

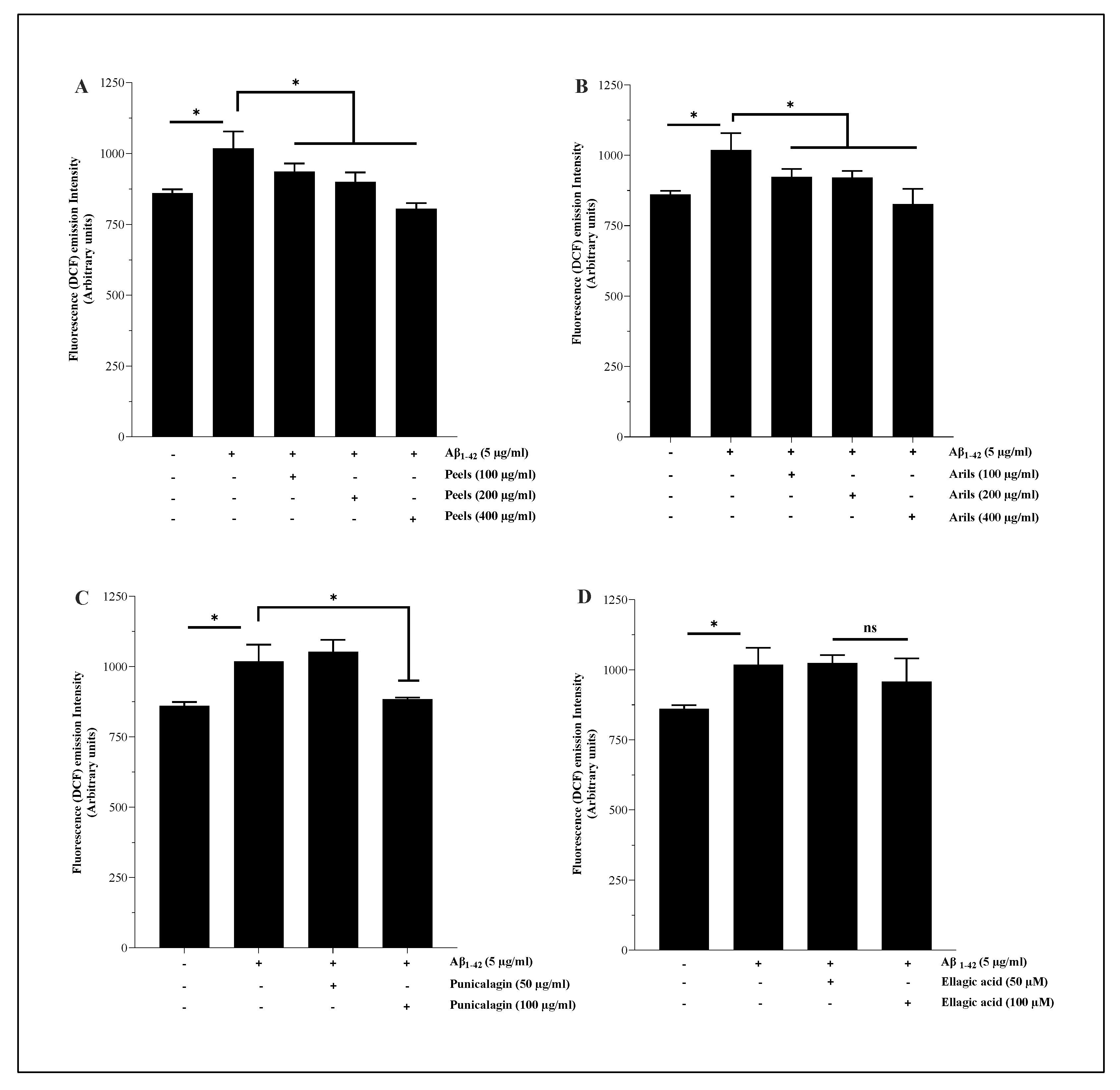

3.4. Measurement of intracellular ROS

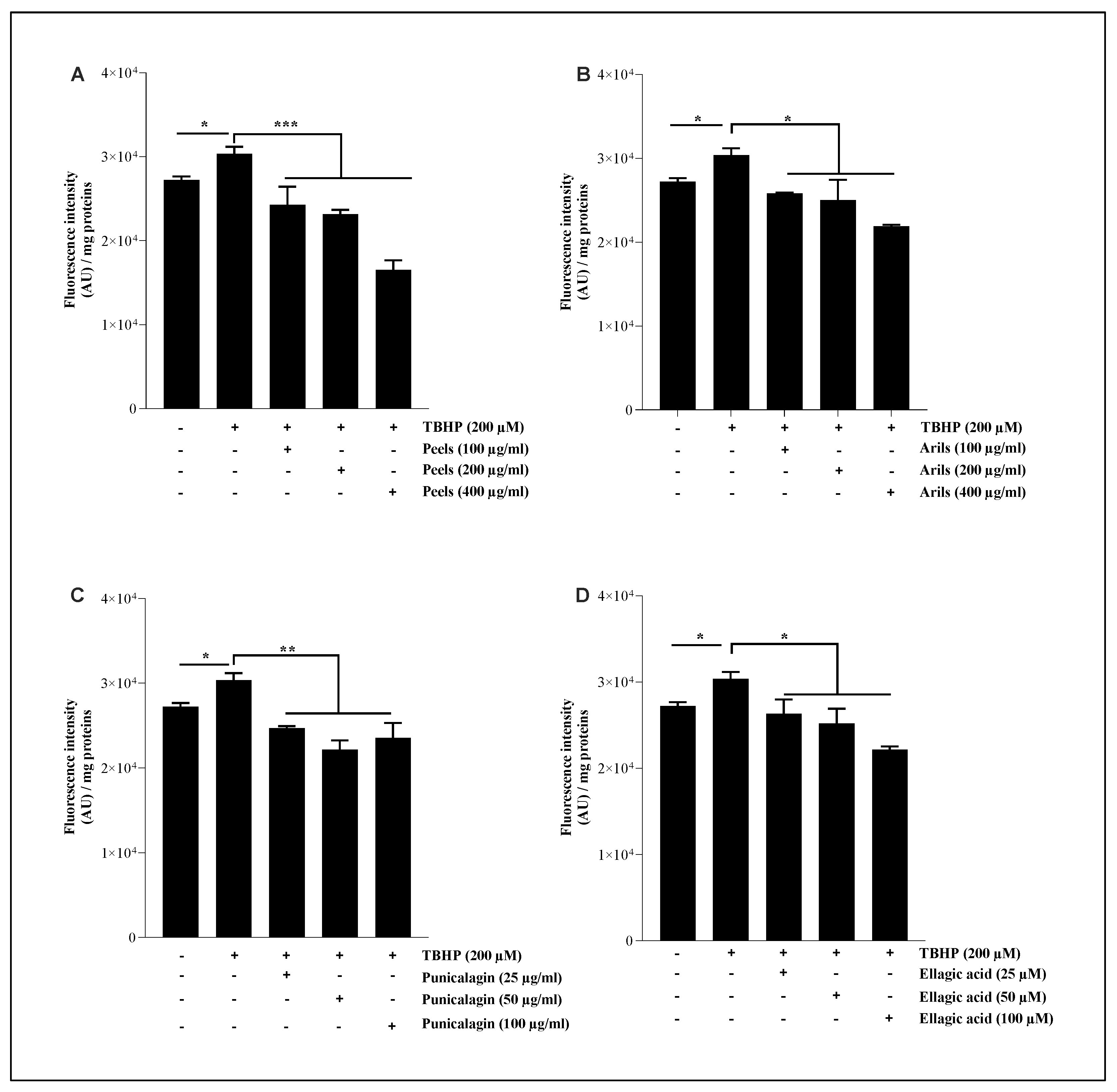

3.5. Lipid Peroxidation Assay

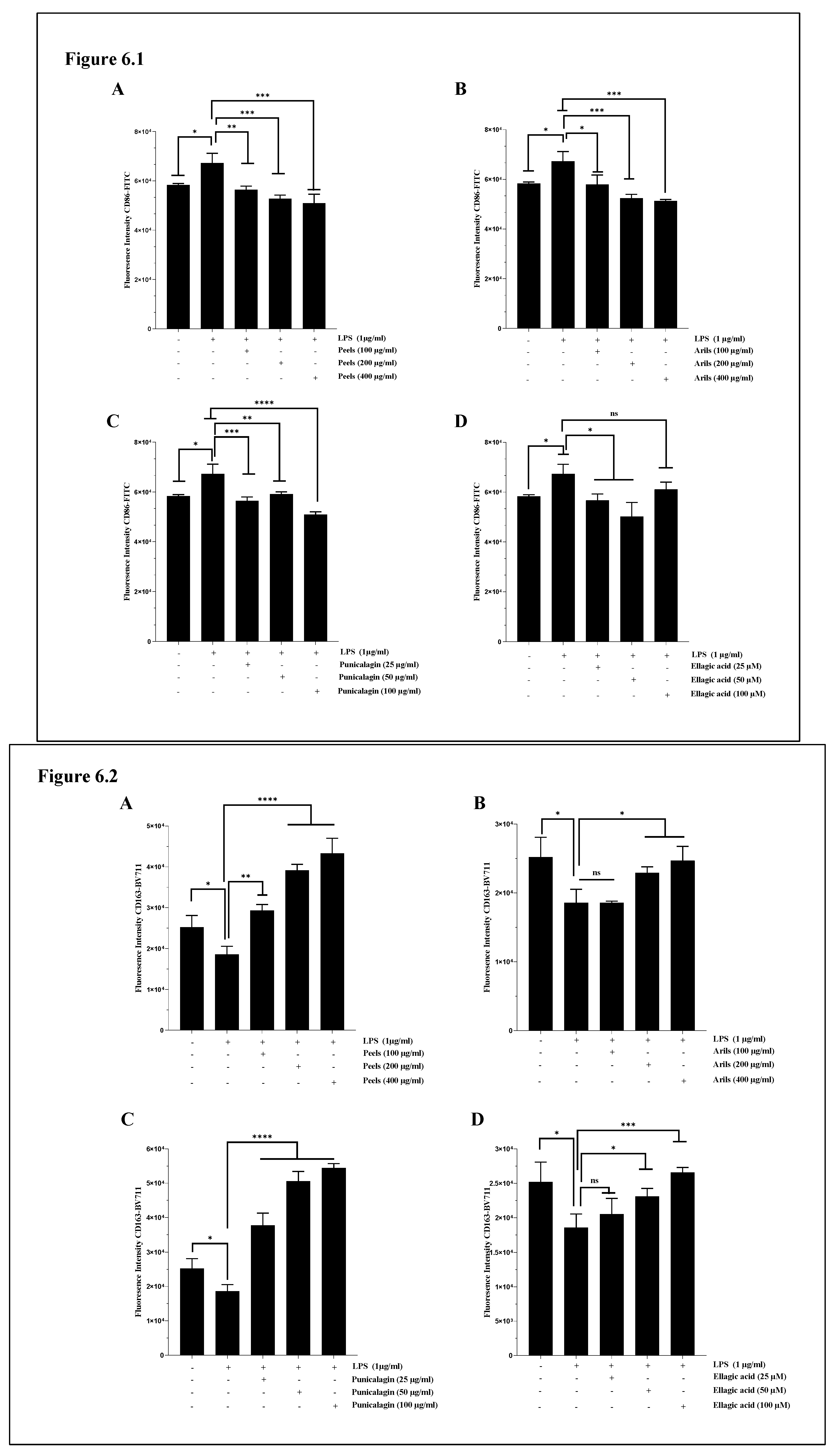

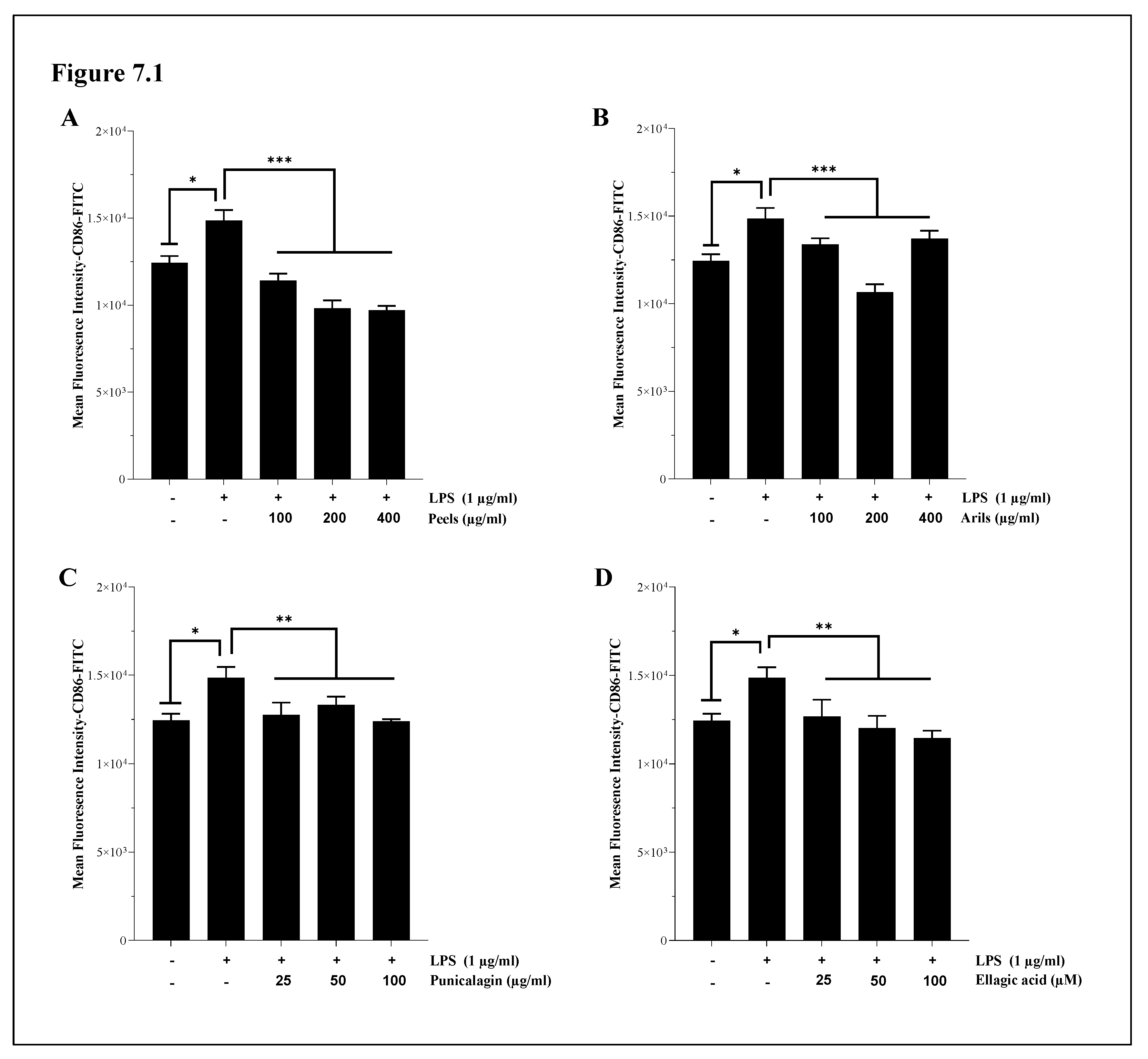

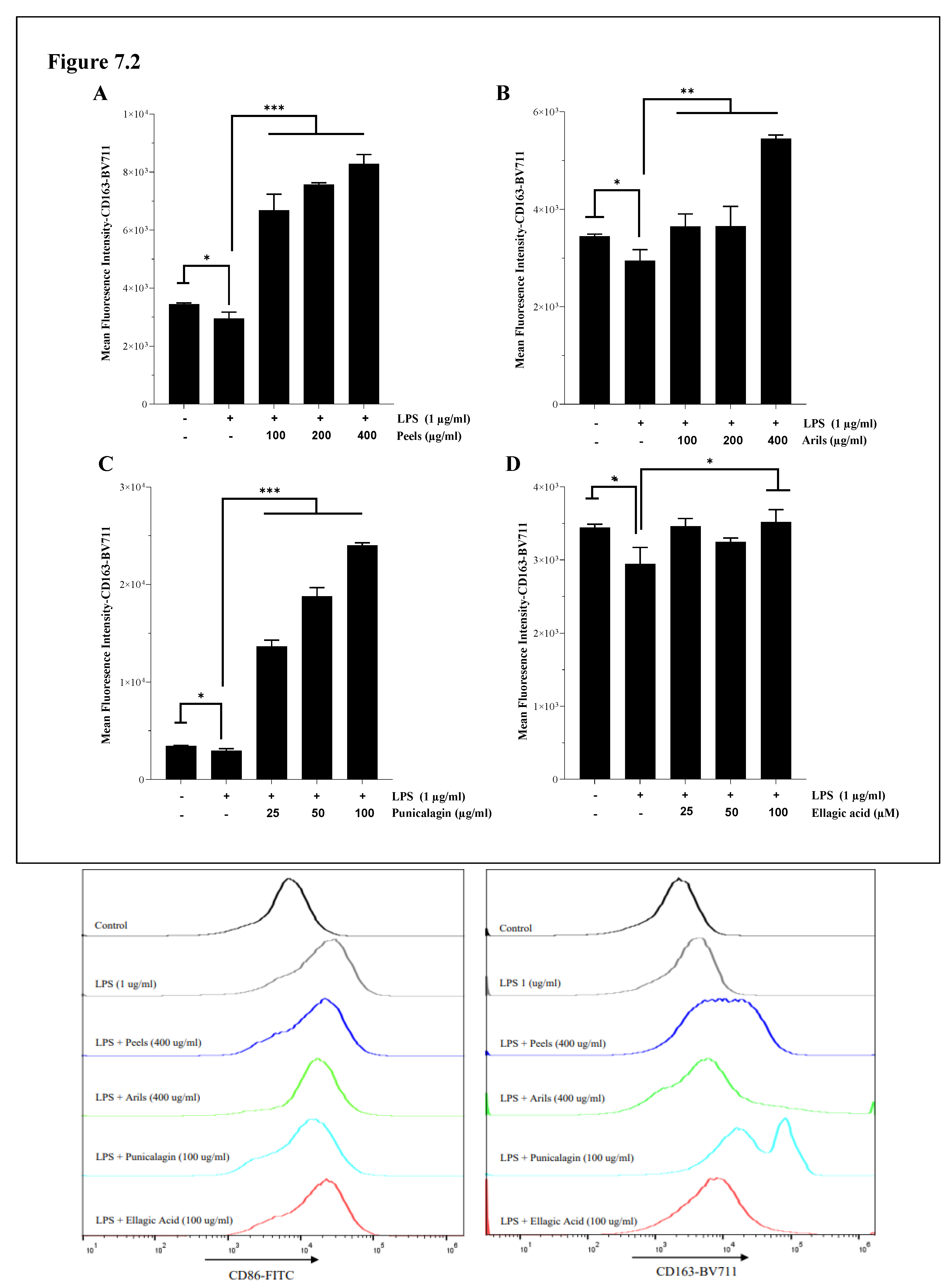

3.6. M1/M2 Polarization of Microglia and Systemic Macrophages

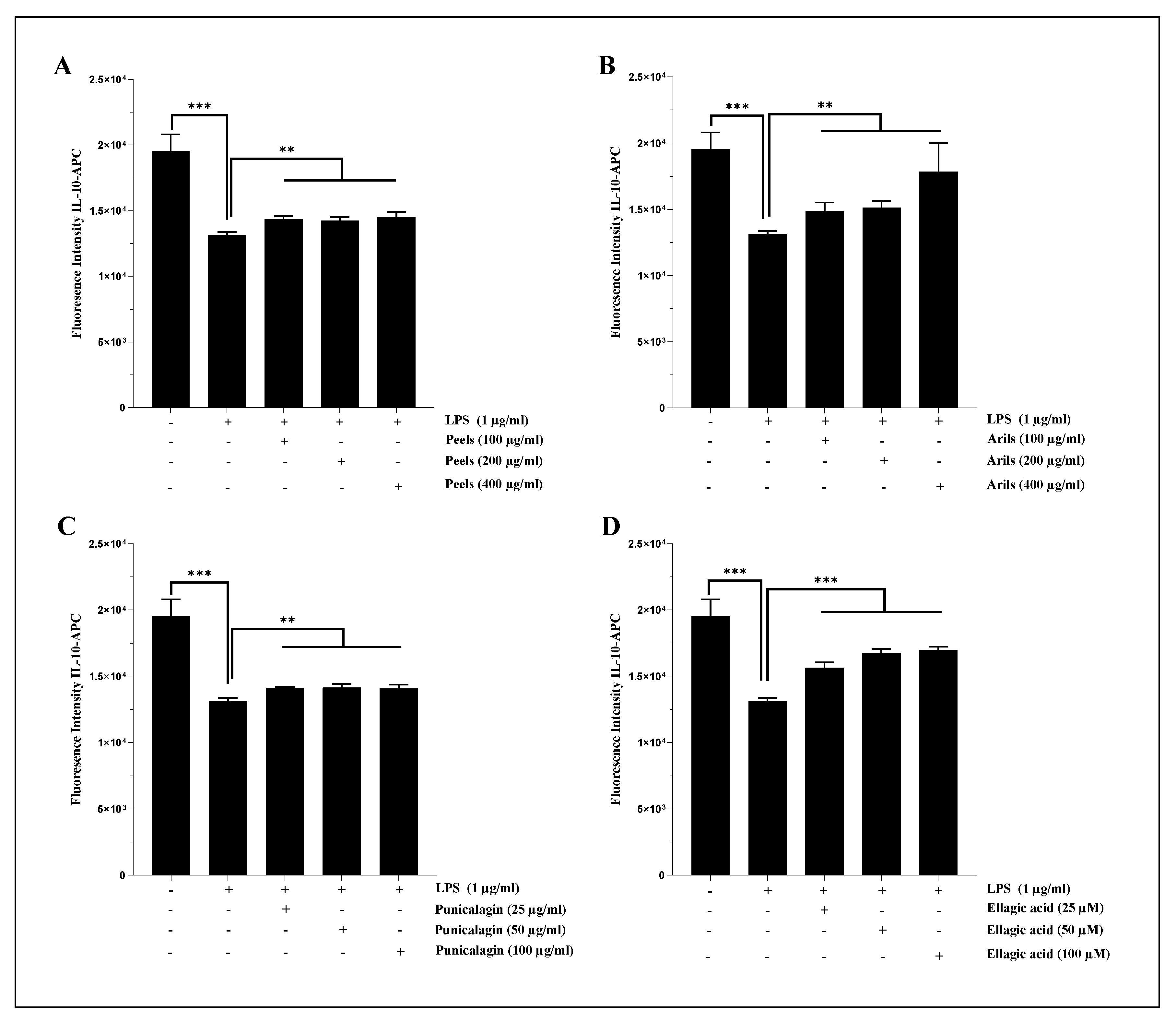

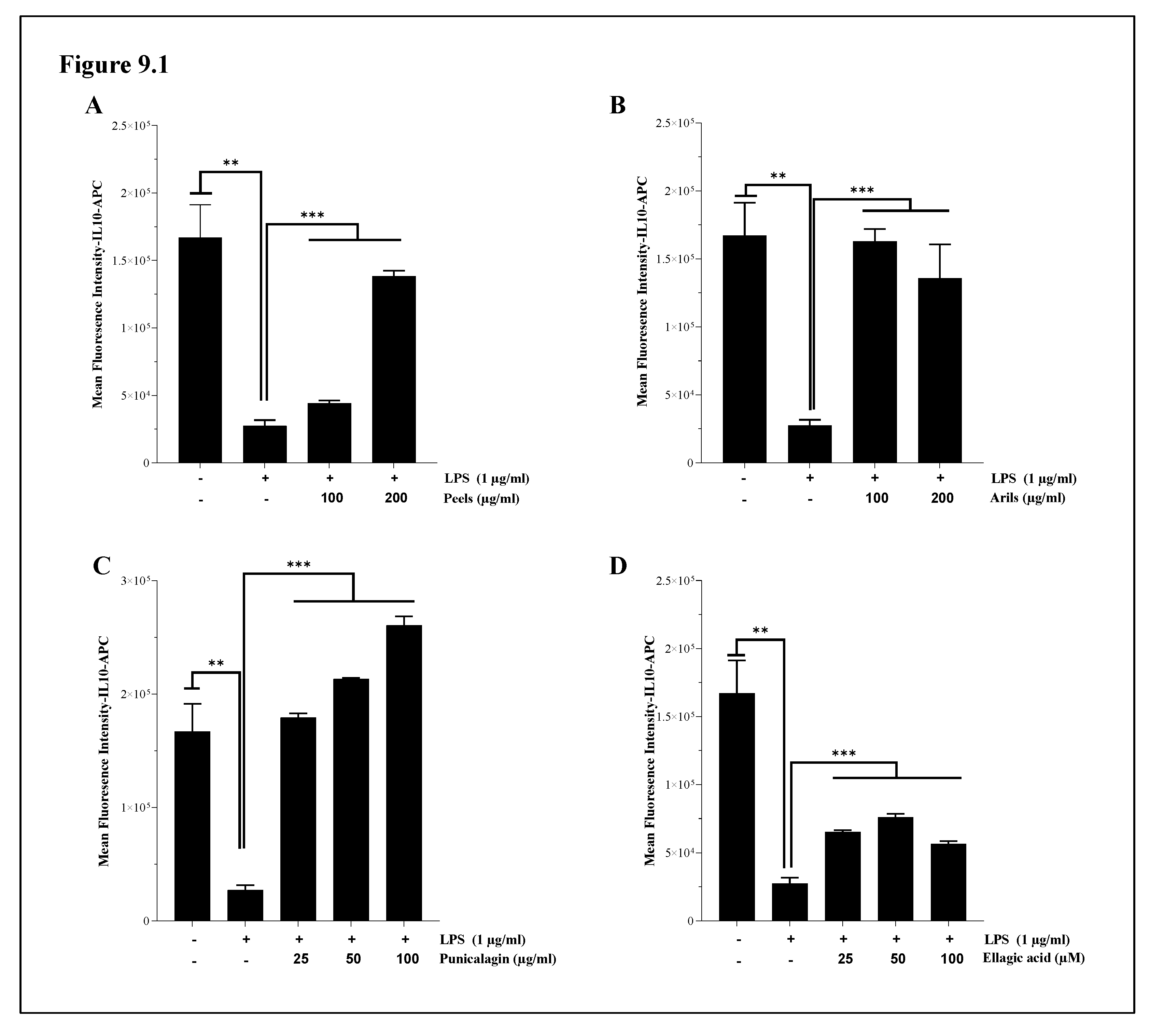

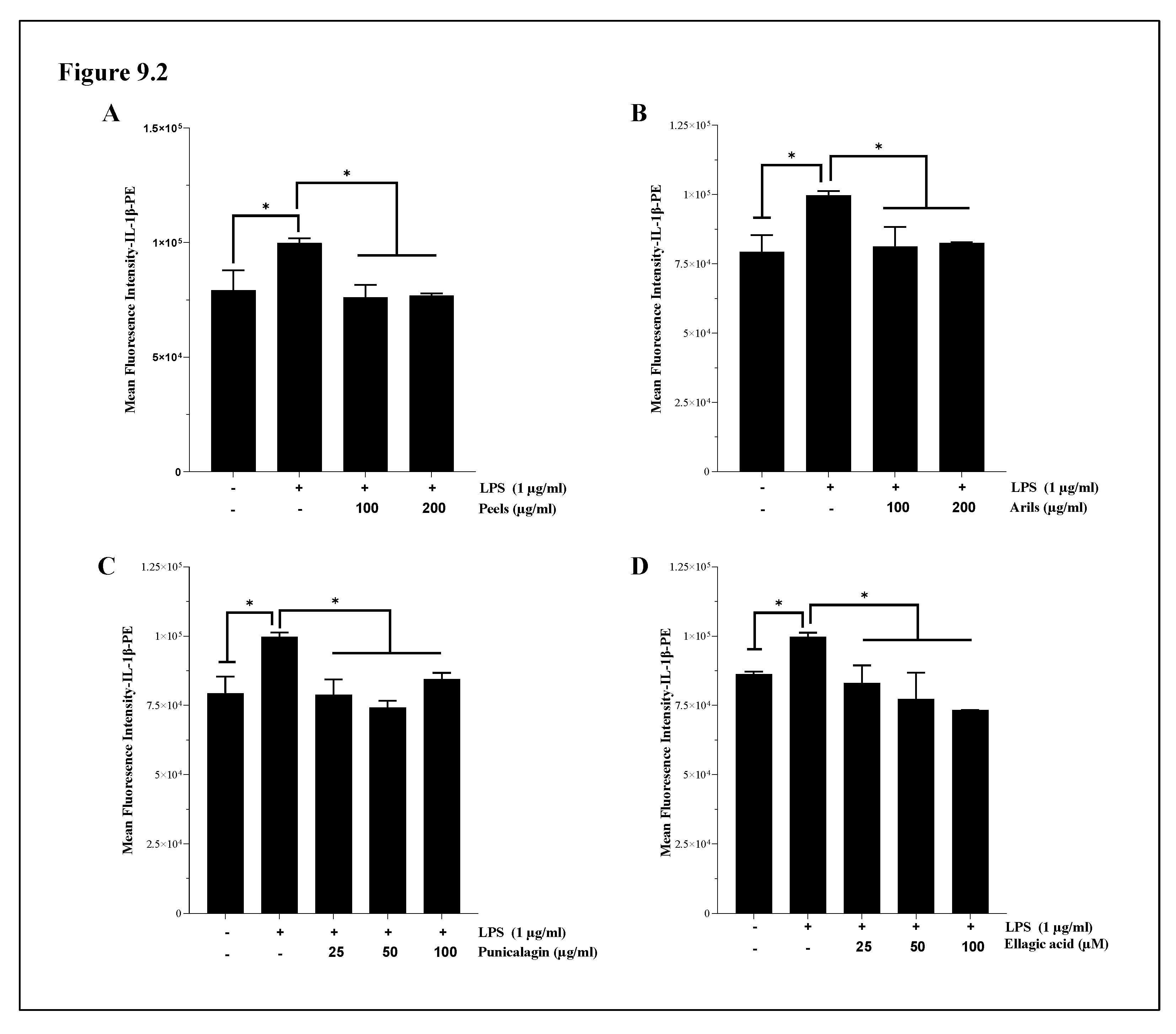

3.7. The Assessment of Interleukin 1-beta (IL-1β) and Interleukin-10 (IL-10) Cytokines Expression

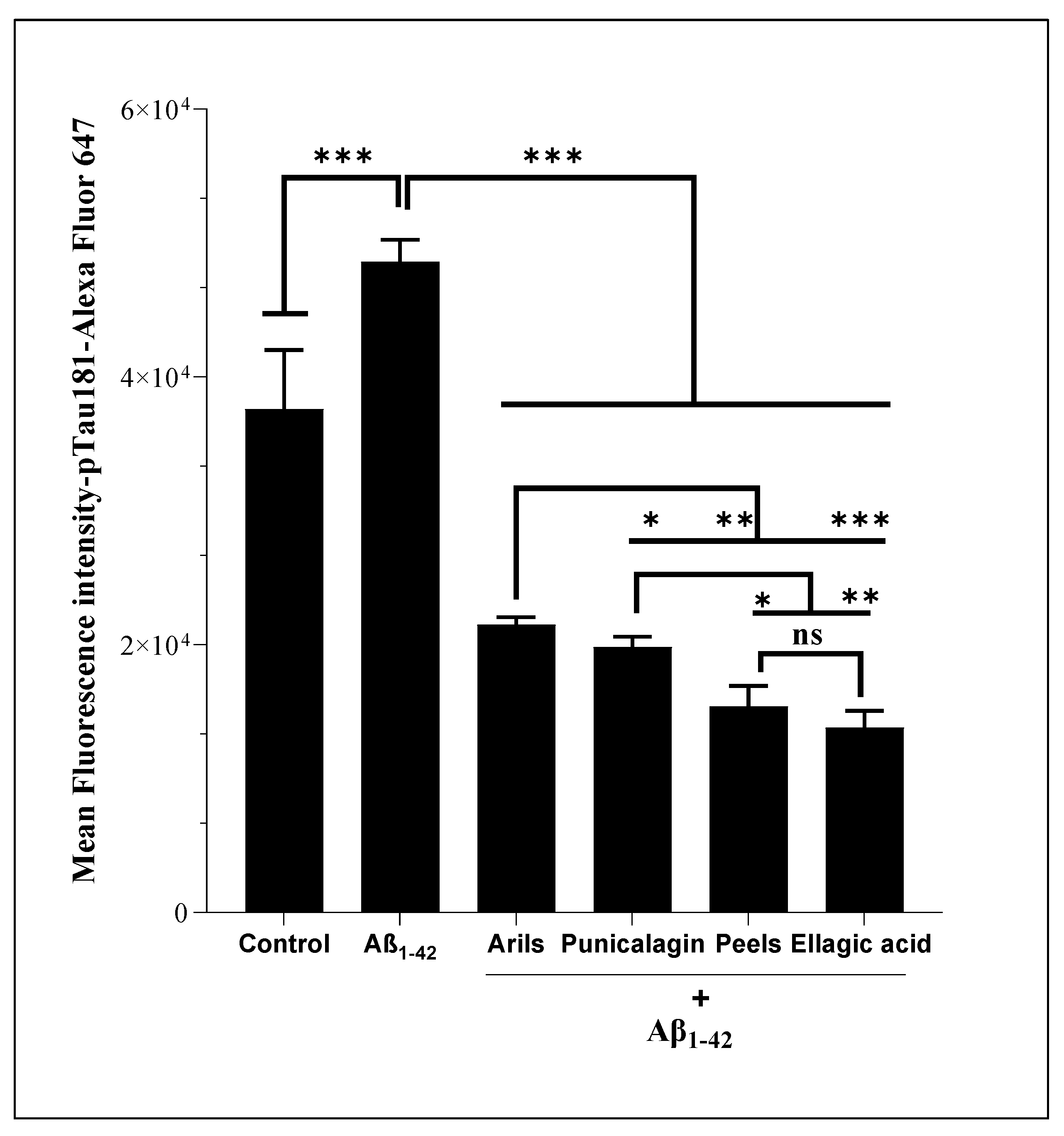

3.8. Tau-Phosphorylation at Threonine 181

4. Conclusion and perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rogers, J.; Luber-Narod, J.; Styren, S.D.; Civin, W.H. Expression of Immune System-Associated Antigens by Cells of the Human Central Nervous System: Relationship to the Pathology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 1988, 9, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiacco, T.A.; Carthy, K.E.N.D.M.C. Astrocyte Calcium Elevations : Properties , Propagation , and Effects on Brain Signaling. 2006, 690, 676–690. [CrossRef]

- Floyd, R.A.; Hensley, K. Nitrone Inhibition of Age-Associated. 222–237.

- Ventura, R.; Harris, K.M. Three-Dimensional Relationships between Hippocampal Synapses and Astrocytes. 1999, 19, 6897–6906.

- Boyarsky, G.; Schlue, B.R.W.; Davis, M.B.E.; Boron, W.F. Intracellular PH Regulation in Single Cultured Astrocytes From Rat Forebrain. 1993, 248.

- Drukarch, B.; Schepens, E.; Stoof, J.C.; Langeveld, C.H.; Van Muiswinkel, F.L. Astrocyte-Enhanced Neuronal Survival Is Mediated by Scavenging of Extracellular Reactive Oxygen Species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1998, 25, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, J.; Mothes, T.; Kolahdouzan, M.; Eriksson, O.; Moslem, M.; Bergström, J.; Ingelsson, M.; O’Callaghan, P.; Healy, L.M.; Falk, A.; et al. Crosstalk between Astrocytes and Microglia Results in Increased Degradation of α-Synuclein and Amyloid-β Aggregates. J. Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilimoria, P.M.; Stevens, B. Microglia Function during Brain Development: New Insights from Animal Models. Brain Res. 2015, 1617, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, W.H.; Lee, D.Y.; Park, K.W.; Kim, S.U.; Yang, M.S.; Joe, E.H.; Jin, B.K. Microglia Expressing Interleukin-13 Undergo Cell Death and Contribute to Neuronal Survival in Vivo. Glia 2004, 46, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Aparicio, I.; Paris, I.; Sierra-Torre, V.; Plaza-Zabala, A.; Rodríguez-Iglesias, N.; Márquez-Ropero, M.; Beccari, S.; Huguet, P.; Abiega, O.; Alberdi, E.; et al. Microglia Actively Remodel Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis through the Phagocytosis Secretome. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 1453–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meda, L.; Cassatella, M.A.; Szendrei, G.I.; Otvos, L.; Baron, P.; Villalba, M.; Ferrari, D.; Rossi, F. Activation of Microglial Cells by β-Amyloid Protein and Interferon-γ. Nature 1995, 374, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Ding, M.; Xue, J.; Leng, W. The Role of TLR2/JNK/NF-ΚB Pathway in Amyloid β Peptide-Induced Inflammatory Response in Mouse NG108-15 Neural Cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2013, 17, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojan, E.; Tylek, K.; Schröder, N.; Kahl, I.; Brandenburg, L.O.; Mastromarino, M.; Leopoldo, M.; Basta-Kaim, A.; Lacivita, E. The N-Formyl Peptide Receptor 2 (FPR2) Agonist MR-39 Improves Ex Vivo and In Vivo Amyloid Beta (1–42)-Induced Neuroinflammation in Mouse Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 6203–6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Yeo, I.J.; Kim, K.C.; Choi, W.R.; Jung, J.K.; Han, S.B.; Hong, J.T. K284-6111 Prevents the Amyloid Beta-Induced Neuroinflammation and Impairment of Recognition Memory through Inhibition of NF-ΚB-Mediated CHI3L1 Expression. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, R.; Parbo, P.; Madsen, L.S.; Hansen, A.K.; Hansen, K. V.; Schaldemose, J.L.; Kjeldsen, P.L.; Stokholm, M.G.; Gottrup, H.; Eskildsen, S.F.; et al. The Relationships between Neuroinflammation, Beta-Amyloid and Tau Deposition in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Longitudinal PET Study. J. Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheignon, C.; Tomas, M.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Faller, P.; Hureau, C.; Collin, F. Oxidative Stress and the Amyloid Beta Peptide in Alzheimer’s Disease. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, I.G.; Czigner, A.; Farkas, E.; Dobó, E.; Soós, K.; Penke, B.; Endrész, V.; Mihály, A. Beta-Amyloid Peptide-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption Facilitates T-Cell Entry into the Rat Brain. Acta Histochem. 2003, 105, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selznick, L.A.; Zheng, T.S.; Flavell, R.A.; Rakic, P.; Roth, K.A. Amyloid Beta-Induced Neuronal Death Is Bax-Dependent but Caspase- Independent. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2000, 59, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Shepardson, N.; Yang, T.; Chen, G.; Walsh, D.; Selkoe, D.J. Soluble Amyloid β-Protein Dimers Isolated from Alzheimer Cortex Directly Induce Tau Hyperphosphorylation and Neuritic Degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 5819–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Akama, K.T.; Krafft, G.A.; Chromy, B.A.; Van Eldik, L.J. Amyloid-β Peptide Activates Cultured Astrocytes: Morphological Alterations, Cytokine Induction and Nitric Oxide Release. Brain Res. 1998, 785, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanji, M.B. Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Meta-Analysis Psychiatry Res. 2017, 327, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekely, C.A.; Zandi, P.P. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Alzheimers Disease: The Epidemiological Evidence. CNS Neurol. Disord. - Drug Targets 2012, 9, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szekely, C.A.; Thorne, J.E.; Zandi, P.P.; Ek, M.; Messias, E.; Breitner, J.C.S.; Goodman, S.N. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs for the Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Neuroepidemiology 2004, 23, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Babu-khan, S.; Vassar, R.; Biere, A.L.; Citron, M.; Landreth, G. Anti-Inflammatory Drug Therapy Alters  -Amyloid Processing and Deposition in an Animal Model of Alzheimer ’ s Disease. 2003, 23, 7504–7509.

- Sun, Y.; Koyama, Y.; Shimada, S. Inflammation From Peripheral Organs to the Brain : How Does Systemic Inflammation Cause Neuroinflammation ? 2022, 14, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Walker, K.A.; Page, L.M. Le; Terrando, N.; Duggan, M.R.; Heneka, M.T.; Bettcher, B.M. The Role of Peripheral Inflammatory Insults in Alzheimer ’ s Disease : A Review and Research Roadmap. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hussain, B.; Chang, J. Peripheral Inflammation and Blood–Brain Barrier Disruption: Effects and Mechanisms. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2021, 27, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tansey, M.G.; Goldberg, M.S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease: Its Role in Neuronal Death and Implications for Therapeutic Intervention. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 37, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mander, P.; Brown, G.C. Activation of Microglial NADPH Oxidase Is Synergistic with Glial INOS Expression in Inducing Neuronal Death: A Dual-Key Mechanism of Inflammatory Neurodegeneration. J. Neuroinflammation 2005, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danesi, F.; Ferguson, L.R. Could Pomegranate Juice Help in the Control of Inflammatory Diseases? Nutrients 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosillo, M.A.; Sánchez-Hidalgo, M.; Cárdeno, A.; Aparicio-Soto, M.; Sánchez-Fidalgo, S.; Villegas, I.; De La Lastra, C.A. Dietary Supplementation of an Ellagic Acid-Enriched Pomegranate Extract Attenuates Chronic Colonic Inflammation in Rats. Pharmacol. Res. 2012, 66, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doostkam, A.; Bassiri-Jahromi, S.; Iravani, K. Punica Granatum with Multiple Effects in Chronic Diseases. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 20, 471–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchagra, L.; Berrougui, H.; Islam, M.O.; Ramchoun, M.; Boulbaroud, S.; Hajjaji, A.; Fulop, T.; Ferretti, G.; Khalil, A. Antioxidant Effect of Moroccan Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L. Sefri Variety) Extracts Rich in Punicalagin against the Oxidative Stress Process. Foods 2021, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.E.; Hwang, C.J.; Lee, H.P.; Kim, C.S.; Son, D.J.; Ham, Y.W.; Hellström, M.; Han, S.B.; Kim, H.S.; Park, E.K.; et al. Inhibitory Effect of Punicalagin on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neuroinflammation, Oxidative Stress and Memory Impairment via Inhibition of Nuclear Factor-KappaB. Neuropharmacology 2017, 117, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velagapudi, R.; Baco, G.; Khela, S.; Okorji, U.; Olajide, O. Pomegranate Inhibits Neuroinflammation and Amyloidogenesis in IL-1β-Stimulated SK-N-SH Cells. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 1653–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojanathammanee, L.; Puig, K.L.; Combs, C.K. Pomegranate Polyphenols and Extract Inhibit Nuclear Factor of Activated T-Cell Activity and Microglial Activation Invitroand Inatransgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer Disease. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essa, M.M.; Subash, S.; Akbar, M.; Al-Adawi, S.; Guillemin, G.J. Long-Term Dietary Supplementation of Pomegranates, Figs and Dates Alleviate Neuroinflammation in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS One 2015, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidy, N.; Essa, M.M.; Poljak, A.; Selvaraju, S.; Al-Adawi, S.; Manivasagm, T.; Thenmozhi, A.J.; Ooi, L.; Sachdev, P.; Guillemin, G.J. Consumption of Pomegranates Improves Synaptic Function in a Transgenic Mice Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 64589–64604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaSilva, N.A.; Nahar, P.P.; Ma, H.; Eid, A.; Wei, Z.; Meschwitz, S.; Zawia, N.H.; Slitt, A.L.; Seeram, N.P. Pomegranate Ellagitannin-Gut Microbial-Derived Metabolites, Urolithins, Inhibit Neuroinflammation in Vitro. Nutr. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.J.; Su, C.J.; Peng, C.S.; Lin, T.E.; Fu, W.C.H.; Hsu, K.C.; Hwang, T.L.; Pan, S.L. Urolithin A Exhibits a Neuroprotective Effect against Alzheimer’s Disease by Inhibiting DYRK1A Activity. J. Food Drug Anal. 2023, 31, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olajide, O.J.; La Rue, C.; Bergdahl, A.; Chapman, C.A. Inhibiting Amyloid Beta (1–42) Peptide-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction Prevents the Degradation of Synaptic Proteins in the Entorhinal Cortex. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denizot, F.; Lang, R. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cell Growth and Survival. Modifications to the Tetrazolium Dye Procedure Giving Improved Sensitivity and Reliability. J. Immunol. Methods 1986, 89, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyeoncheol, K.; Xiang, X. Detection of Total Reactive Oxygen Species in Adherent Cells by 2’,7’-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein Diacetate Staining. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 160. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan, T.; Choi, Y.W.; Kim, Y.K. Effect of an Extraction Solvent on the Antioxidant Quality of Pinus Densiflora Needle Extract. J. Pharm. Anal. 2019, 9, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ÇINAR, İ.; YAYLA, M.; DEMİRBAĞ, Ç.; BİNNETOĞLU, D. Pomegranate Peel Extract Reduces Cisplatin-Induced Toxicity and Oxidative Stress in Primary Neuron Culture. Clin. Exp. Heal. Sci. 2021, 11, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthika, C.; Sureshkumar, R.; Zehravi, M.; Akter, R.; Ali, F.; Ramproshad, S.; Mondal, B.; Tagde, P.; Ahmed, Z.; Khan, F.S.; et al. Multidrug Resistance of Cancer Cells and the Vital Role of P-Glycoprotein. Life 2022, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkhathlan, Z.; Lavasanifar, A. P-Glycoprotein Inhibition as a Therapeutic Approach for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance in Cancer: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2013, 13, 326–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, R.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Jorge, J.; Almeida, A.M.; Sarmento-ribeiro, A.B. Combination of Elacridar with Imatinib Modulates Resistance Associated with Drug Efflux Transporters in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, H.; Siddig, S.; Uzu, M.; Suzuki, S.; Nomura, Y.; Kashiba, T.; Gushimiyagi, K.; Sekine, Y.; Uehara, T.; Arano, Y.; et al. Elacridar Enhances the Cytotoxic Effects of Sunitinib and Prevents Multidrug Resistance in Renal Carcinoma Cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 746, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouillette, J.; Caillierez, R.; Zommer, N.; Alves-Pires, C.; Benilova, I.; Blum, D.; de Strooper, B.; Buée, L. Neurotoxicity and Memory Deficits Induced by Soluble Low-Molecular-Weight Amyloid-β 1-42 Oligomers Are Revealed in Vivo by Using a Novel Animal Model. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 7852–7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cizas, P.; Budvytyte, R.; Morkuniene, R.; Moldovan, R.; Broccio, M.; Lösche, M.; Niaura, G.; Valincius, G.; Borutaite, V. Size-Dependent Neurotoxicity of β-Amyloid Oligomers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 496, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, D.; Song, H.J.; Garza, D.; Neufeld, T.P.; Salvaterra, P.M. Abeta42-Induced Neurodegeneration via an Age-Dependent Autophagic-Lysosomal Injury in Drosophila. PLoS One 2009, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, D.; Schuff, N.; Mathis, C.A.; Jagust, W.; Weiner, M.W. Spatial Patterns of Brain Amyloid-β Burden and Atrophy Rate Associations in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Brain 2011, 134, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemppainen, N.; Johansson, J.; Teuho, J.; Helin, S.; Liu, Y.; Helisalmi, S.; Soininen, H.; Parkkola, R.; Ngandu, T.; Kivipelto, X.M.; et al. Brain -Amyloid and Atrophy in Individuals at Increased Risk of Cognitive Decline. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2019, 40, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chételat, G.; Villemagne, V.L.; Bourgeat, P.; Pike, K.E.; Jones, G.; Ames, D.; Ellis, K.A.; Szoeke, C.; Martins, R.N.; O’Keefe, G.J.; et al. Relationship between Atrophy and β-Amyloid Deposition in Alzheimer Disease. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 67, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iflazoglu Mutlu, S.; Seven, I.; Arkali, G.; Birben, N.; Sur Arslan, A.; Aksakal, M.; Tatli Seven, P. Ellagic Acid Plays an Important Role in Enhancing Productive Performance and Alleviating Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis in Laying Quail Exposed to Lead Toxicity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, G.; Longpré, F.; Martinoli, M.G. Resveratrol and Quercetin, Two Natural Polyphenols, Reduce Apoptotic Neuronal Cell Death Induced by Neuroinflammation. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008, 86, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Missiry, M.A.; ElKomy, M.A.; Othman, A.I.; AbouEl-ezz, A.M. Punicalagin Ameliorates the Elevation of Plasma Homocysteine, Amyloid-β, TNF-α and Apoptosis by Advocating Antioxidants and Modulating Apoptotic Mediator Proteins in Brain. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 102, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolaños, J.P.; Moro, M.A.; Lizasoain, I.; Almeida, A. Mitochondria and Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species in Neurological Disorders and Stroke: Therapeutic Implications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabraoui, T.; Khider, T.; Nasser, B.; Eddoha, R.; Moujahid, A.; Benbachir, M.; Essamadi, A. Determination of Punicalagins Content, Metal Chelating, and Antioxidant Properties of Edible Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L) Peels and Seeds Grown in Morocco. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 2020, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and Biochemistry of Dietary Polyphenols. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert Cronin Yung Peng, Rose Khavari, N.D. 乳鼠心肌提取 HHS Public Access. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 176, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Shichiri, M. Oxidative Stress Biomaker and Its Application to Health Maintainance The Role of Lipid Peroxidation in Neurological Disorders. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr 2014, 54, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smaoui, S.; Hlima, H. Ben; Mtibaa, A.C.; Fourati, M.; Sellem, I.; Elhadef, K.; Ennouri, K.; Mellouli, L. Pomegranate Peel as Phenolic Compounds Source: Advanced Analytical Strategies and Practical Use in Meat Products. Meat Sci. 2019, 158, 107914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtaza, S.; Khan, J.A.; Aslam, B.; Faisal, M.N. Pomegranate Peel Extract and Quercetin Possess Antioxidant and Hepatoprotective Activity against Concanavalin A-Induced Liver Injury in Mice. Pak. Vet. J. 2021, 41, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morzelle, M.C.; Salgado, J.M.; Telles, M.; Mourelle, D.; Bachiega, P.; Buck, H.S.; Viel, T.A. Neuroprotective Effects of Pomegranate Peel Extract after Chronic Infusion with Amyloid-β Peptide in Mice. PLoS One 2016, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaidikar, L.; Byna, B.; Thakur, S.R. Neuroprotective Effect of Punicalagin against Cerebral Ischemia Reperfusion-Induced Oxidative Brain Injury in Rats. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2014, 23, 2869–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerdá, B.; Llorach, R.; Cerón, J.J.; Espín, J.C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Evaluation of the Bioavailability and Metabolism in the Rat of Punicalagin, an Antioxidant Polyphenol from Pomegranate Juice. Eur. J. Nutr. 2003, 42, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeram, N.P.; Lee, R.; Heber, D. Bioavailability of Ellagic Acid in Human Plasma after Consumption of Ellagitannins from Pomegranate (Punica Granatum L.) Juice. Clin. Chim. Acta 2004, 348, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdar, B.S.; Erkmen, T.; Koçtürk, S. Combinations of Polyphenols Disaggregate Aβ1-42 by Passing through in Vitro Blood-Brain Barrier Developed by Endothelium, Astrocyte, and Differentiated SH-SY5Y Cells. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. (Wars). 2021, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, L.; Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Wen, A.; Ding, Y. Aging-12-103270. 2020, 12, 10457–10472.

- Lu, Z.; Liu, S.; Lopes-Virella, M.F.; Wang, Z. LPS and Palmitic Acid Co-Upregulate Microglia Activation and Neuroinflammatory Response. Compr. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 6, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Y.; Ma, J.; Gao, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Zang, J. Pomegranate Peel as a Source of Bioactive Compounds: A Mini Review on Their Physiological Functions. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benchagra, L.; Berrougui, H.; Islam, M.O.; Ramchoun, M. Antioxidant Effect of Moroccan Pomegranate ( Punica Granatum L. Foods 2021, 10, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Aguirre, C.E.; García-Villalba, R.; Beltrán, D.; Frutos-Lisón, M.D.; Espín, J.C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Selma, M. V. Gut Bacteria Involved in Ellagic Acid Metabolism To Yield Human Urolithin Metabotypes Revealed. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 4029–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, R.; Jamieson, S.; Pandey, A.K.; Bishayee, A. Neuroprotective Potential of Ellagic Acid: A Critical Review. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1211–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjay; Shin, J.H.; Park, M.; Lee, H.J. Cyanidin-3-O-Glucoside Regulates the M1/M2 Polarization of Microglia via PPARγ and Aβ42 Phagocytosis Through TREM2 in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 5135–5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, R.H.; Schradin, C. Chronic Inflammatory Systemic Diseases – an Evolutionary Trade-off between Acutely Beneficial but Chronically Harmful Programs. Evol. Med. Public Heal. 2016, eow001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, D.W.; Fasano, A.; Miller, G.W.; et al. Across the Life Span. Nat. Med. 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennen, J.; Aeby, P.; Goebel, C.; Schettgen, T.; Oberli, A.; Kalmes, M.; Blömeke, B. Cross Talk between Keratinocytes and Dendritic Cells: Impact on the Prediction of Sensitization. Toxicol. Sci. 2011, 123, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.Y.; Han, B.; Deng, X.; Deng, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Shen, P.X.; Hui, T.; Chen, R.H.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Pomegranate Peel Extract Ameliorates the Severity of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis via Modulation of Gut Microbiota. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romier-Crouzet, B.; Van De Walle, J.; During, A.; Joly, A.; Rousseau, C.; Henry, O.; Larondelle, Y.; Schneider, Y.J. Inhibition of Inflammatory Mediators by Polyphenolic Plant Extracts in Human Intestinal Caco-2 Cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romier, B.; Schneider, Y.J.; Larondelle, Y.; During, A. Dietary Polyphenols Can Modulate the Intestinal Inflammatory Response. Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaidikar, L.; Thakur, S. Punicalagin Attenuated Cerebral Ischemia–Reperfusion Insult via Inhibition of Proinflammatory Cytokines, up-Regulation of Bcl-2, down-Regulation of Bax, and Caspase-3. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 402, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vezza, T.; Rodríguez-Nogales, A.; Algieri, F.; Utrilla, M.P.; Rodriguez-Cabezas, M.E.; Galvez, J. Flavonoids in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review. Nutrients 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viuda-Martos, M.; Fernández-Lóaez, J.; Pérez-álvarez, J.A. Pomegranate and Its Many Functional Components as Related to Human Health: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2010, 9, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Sahana, G.R.; Nagella, P.; Joseph, B. V.; Alessa, F.M.; Al-Mssallem, M.Q. Flavonoids as Potential Anti-Inflammatory Molecules: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, B.; Fu, W.; Reddivari, L. The Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Dietary Anthocyanins against Ulcerative Colitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, J.; He, S.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wang, N.; Liu, Q. Punicalagin, a PTP1B Inhibitor, Induces M2c Phenotype Polarization via up-Regulation of HO-1 in Murine Macrophages. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 110, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.L.; Huang, H.J.; Sheu, S.Y.; Liu, Y.C.; Lee, I.J.; Chiang, S.C.; Lin, A.M.Y. Oral Ellagic Acid Attenuated LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation in Rat Brain: MEK1 Interaction and M2 Microglial Polarization. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 248, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeram, N.P.; Aronson, W.J.; Zhang, Y.; Henning, S.M.; Moro, A.; Lee, R.P.; Sartippour, M.; Harris, D.M.; Rettig, M.; Suchard, M.A.; et al. Pomegranate Ellagitannin-Derived Metabolites Inhibit Prostate Cancer Growth and Localize to the Mouse Prostate Gland. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 7732–7737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharoni, S.; Lati, Y.; Aviram, M.; Fuhrman, B. Pomegranate Juice Polyphenols Induce a Phenotypic Switch in Macrophage Polarization Favoring a M2 Anti-Inflammatory State. BioFactors 2015, 41, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitz, C. Genetic Loci Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. Future Neurol. 2014, 9, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, S.C.; Rosenberg, R.N. Genome-Wide Association Studies in Alzheimer Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2008, 65, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F. NSAID Exposure and Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease: An Updated Meta-Analysis from Cohort Studies. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparini, L.; Ongini, E.; Wenk, G. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) in Alzheimer’s Disease: Old and New Mechanisms of Action. J. Neurochem. 2004, 91, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Huang, J.; Xu, B.; Ou, Z.; Zhang, L.; Lin, X.; Ye, X.; Kong, X.; Long, D.; Sun, X.; et al. Urolithin A Attenuates Memory Impairment and Neuroinflammation in APP/PS1 Mice. J. Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, J.; Ren, G.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, X.; Yang, L. Punicalagin Prevents Inflammation in Lps-Induced Raw264.7 Macrophages by Inhibiting Foxo3a/Autophagy Signaling Pathway. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Yang, M.; Hou, C. Pomegranate Peel Polyphenols Inhibits Inflammation in LPS-Induced RAW264.7 Macrophages via the Suppression of TLR4/NF-ΚB Pathway Activation. Food Nutr. Res. 2019, 63, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapias, V.; Cannon, J.R.; Greenamyre, J.T. Pomegranate Juice Exacerbates Oxidative Stress and Nigrostriatal Degeneration in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, 1162–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chachay, V.S.; Macdonald, G.A.; Martin, J.H.; Whitehead, J.P.; O’Moore-Sullivan, T.M.; Lee, P.; Franklin, M.; Klein, K.; Taylor, P.J.; Ferguson, M.; et al. Resveratrol Does Not Benefit Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 2092–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kujawska, M.; Jourdes, M.; Kurpik, M.; Szulc, M.; Szaefer, H.; Chmielarz, P.; Kreiner, G.; Krajka-ku, V. Neuroprotective Effects of Pomegranate Juice against Parkinson ’ s Disease and Presence of Ellagitannins- Derived Metabolite — Urolithin A — In the Brain. 2020.

- Fath, T.; Eidenmüller, J.; Brandt, R. Tau-Mediated Cytotoxicity in a Pseudohyperphosphorylation Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 9733–9741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Wood, J.G. Functional Studies of Alzheimer’s Disease Tau Protein. J. Neurosci. 1993, 13, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, K.; Johnson, G. The Role of Tau Phosphorylation in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimers Disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2006, 3, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Martín, T.; Cuchillo-Ibáñez, I.; Noble, W.; Nyenya, F.; Anderton, B.H.; Hanger, D.P. Tau Phosphorylation Affects Its Axonal Transport and Degradation. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 2146–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.W.A.; Lee, G.; Jay, D.G. Tau Is Required for Neurite Outgrowth and Growth Cone Motility of Chick Sensory Neurons. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 1999, 43, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.V.W.; Stoothoff, W.H. Tau Phosphorylation in Neuronal Cell Function and Dysfunction. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.L.; Kofler, J.K.; Klunk, W.E.; Oscar, L. With Psychosis. 2015, 39, 759–773. [CrossRef]

- Perotti, A.; Oliveira, M.H.; Portugal. Ministério da Educação Apologia Do Intercultural. Educ. Intercult. 1997, 7, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M.E.; Lowe, V.J.; Graff-Radford, N.R.; Liesinger, A.M.; Cannon, A.; Przybelski, S.A.; Rawal, B.; Parisi, J.E.; Petersen, R.C.; Kantarci, K.; et al. Clinicopathologic and 11C-Pittsburgh Compound B Implications of Thal Amyloid Phase across the Alzheimer’s Disease Spectrum. Brain 2015, 138, 1370–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, X.Y.; Koepp, M.; Duncan, J.S.; Fox, N.; Thompson, P.; Baxendale, S.; Liu, J.Y.W.; Reeves, C.; Michalak, Z.; Thom, M. Hyperphosphorylated Tau in Patients with Refractory Epilepsy Correlates with Cognitive Decline: A Study of Temporal Lobe Resections. Brain 2016, 139, 2441–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manassero, G.; Guglielmotto, M.; Zamfir, R.; Borghi, R.; Colombo, L.; Salmona, M.; Perry, G.; Odetti, P.; Arancio, O.; Tamagno, E.; et al. Beta-Amyloid 1-42 Monomers, but Not Oligomers, Produce PHF-like Conformation of Tau Protein. Aging Cell 2016, 15, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Jiang, B.; Fei, H.; Sun, Z. Ellagic Acid Ameliorates Learning and Memory Impairment in APP/PS1 Transgenic Mice via Inhibition of β-Amyloid Production and Tau Hyperphosphorylation. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 4951–4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, I.; Gomez-Isla, T.; Puig, B.; Freixes, M.; Ribe, E.; Dalfo, E.; Avila, J. Current Advances on Different Kinases Involved in Tau Phosphorylation, and Implications in Alzheimers Disease and Tauopathies. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2005, 2, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanbe, A.; Osinska, H.; Villa, C.; Gulick, J.; Klevitsky, R.; Glabe, C.G.; Kayed, R.; Robbins, J. Reversal of Amyloid-Induced Heart Disease in Desmin-Related Cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005, 102, 13592–13597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).