Submitted:

27 July 2024

Posted:

30 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

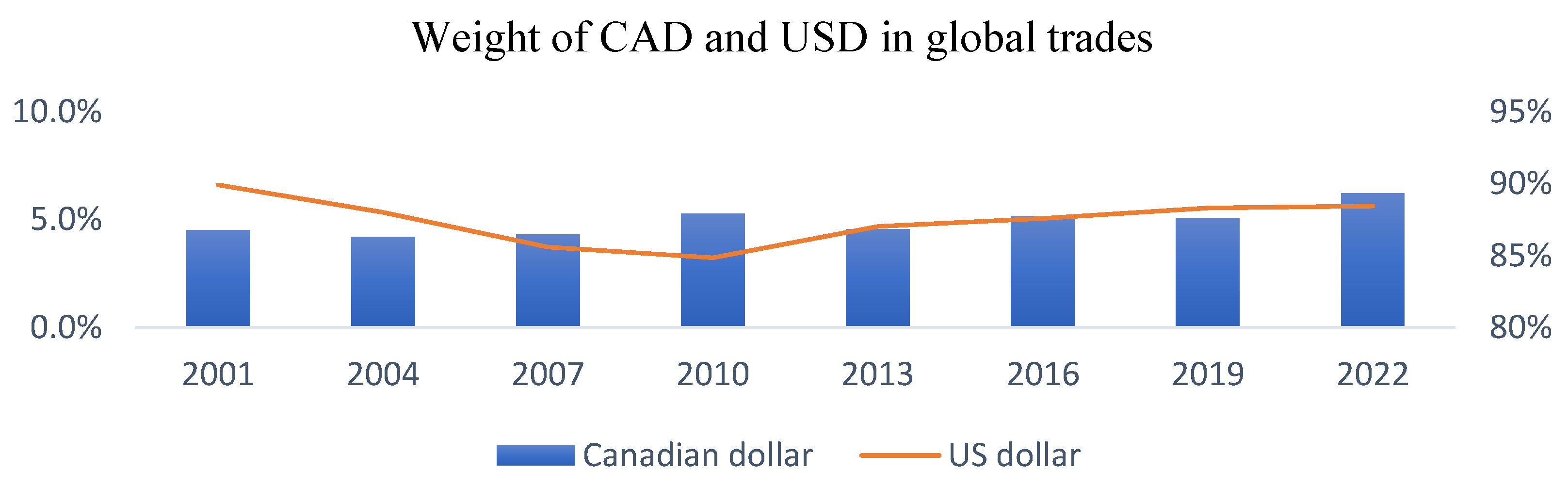

1. Background to Study

2. Literature Review

2.1. Exchange Rate Determination

2.2. Real and Nominal Shocks

2.3. Structural Vector Autoregressions

3. Methodology

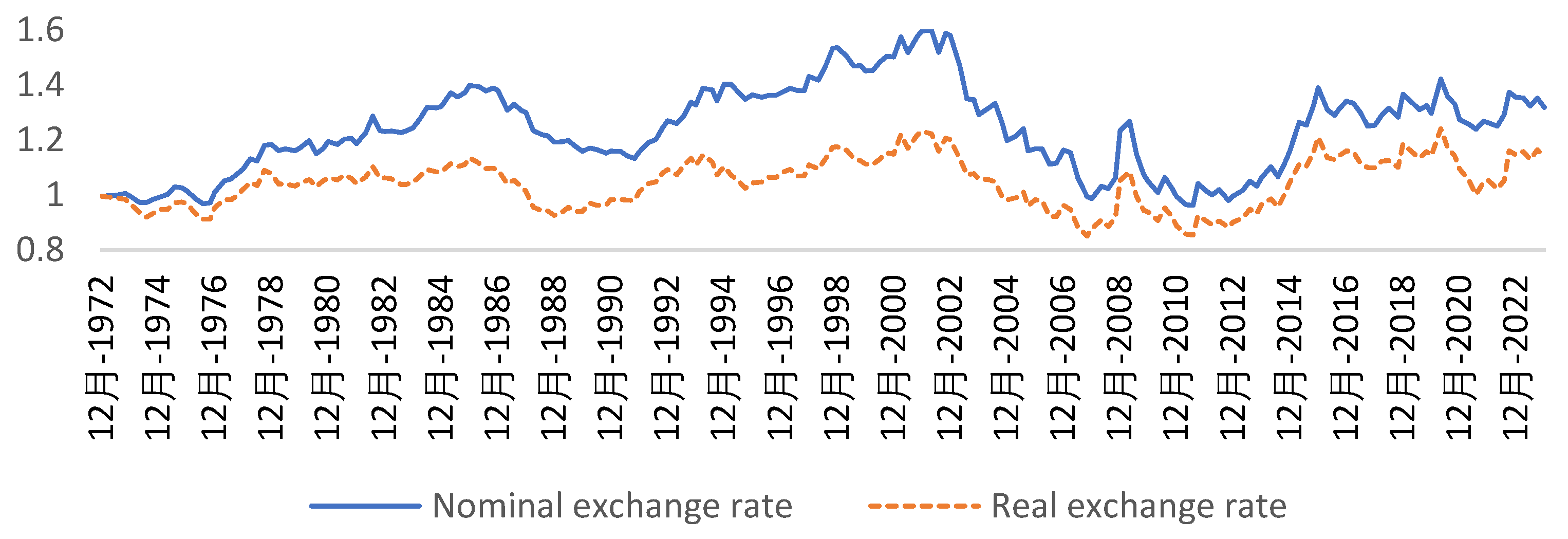

3.1. Nominal and Real Exchange Rate

3.2. Structural VAR Model

4. Data

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

| ρ(k) | k = 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Without first order differencing | |||||

| NER | 0.961 | 0.916 | 0.879 | 0.838 | 0.796 |

| RER | 0.93 | 0.856 | 0.801 | 0.737 | 0.663 |

| With first order differencing | |||||

| NER | 0.081 | -0.101 | 0.036 | 0.016 | -0.057 |

| RER | 0.025 | -0.137 | 0.06 | 0.075 | -0.056 |

5. Research Findings

5.1. Lag Optimization

| Lag | LogL | LR | FPE | AIC | SC | HQ |

| 0 | 999.609 | NA | 1.300E-07 | -10.180 | -10.146 | -10.166 |

| 1 | 1010.102 | 20.663 | 1.220E-07 | -10.246 | -10.145 | -10.205 |

| 2 | 1012.760 | 5.181 | 1.230E-07 | -10.232 | -10.064 | -10.164 |

| 3 | 1015.074 | 4.462 | 1.260E-07 | -10.215 | -9.981 | -10.120 |

| 4 | 1019.371 | 8.201 | 1.250E-07 | -10.218 | -9.917 | -10.096 |

| 5 | 1021.178 | 3.411 | 1.280E-07 | -10.195 | -9.983 | -10.046 |

5.2. Structural VAR

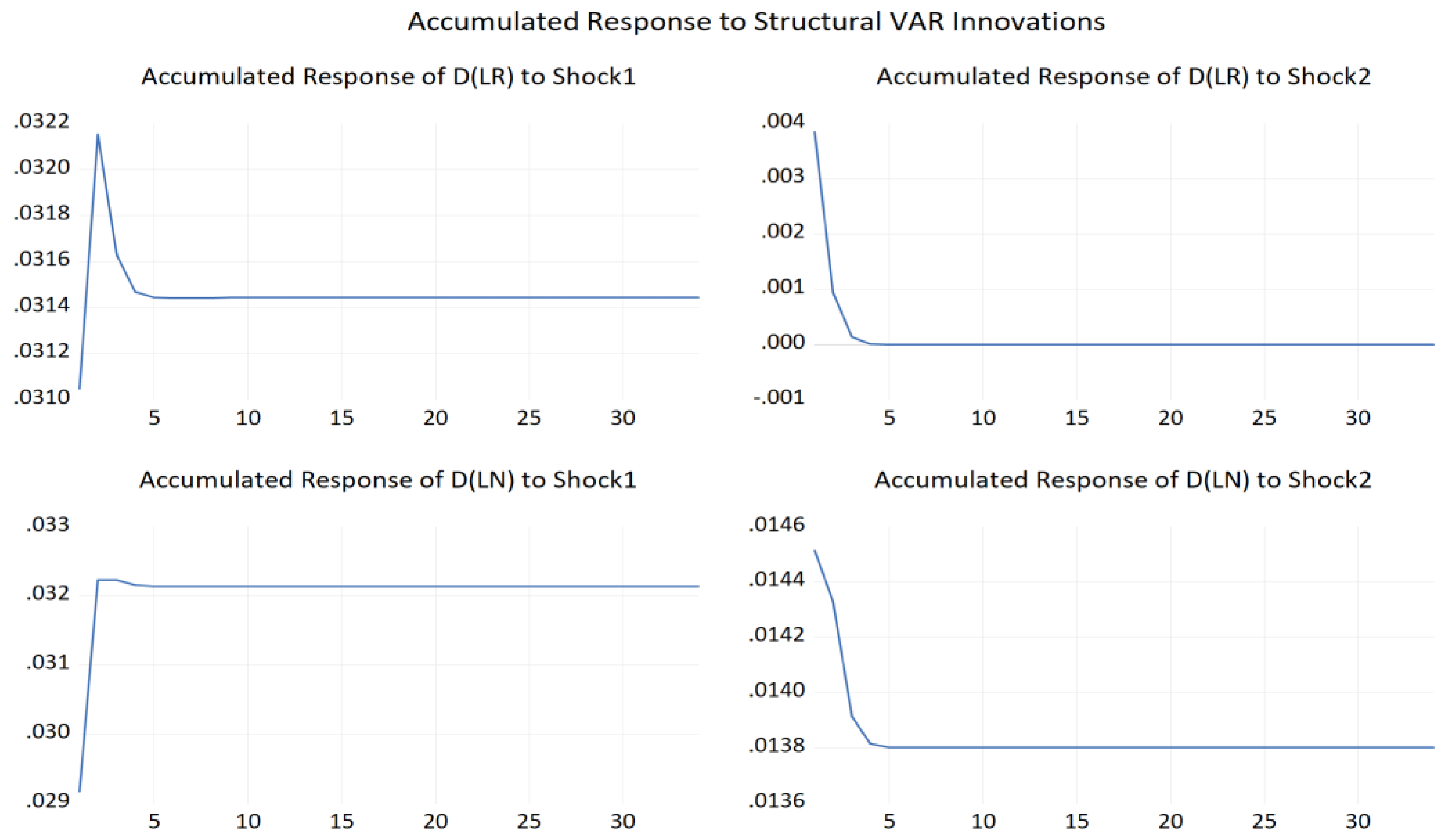

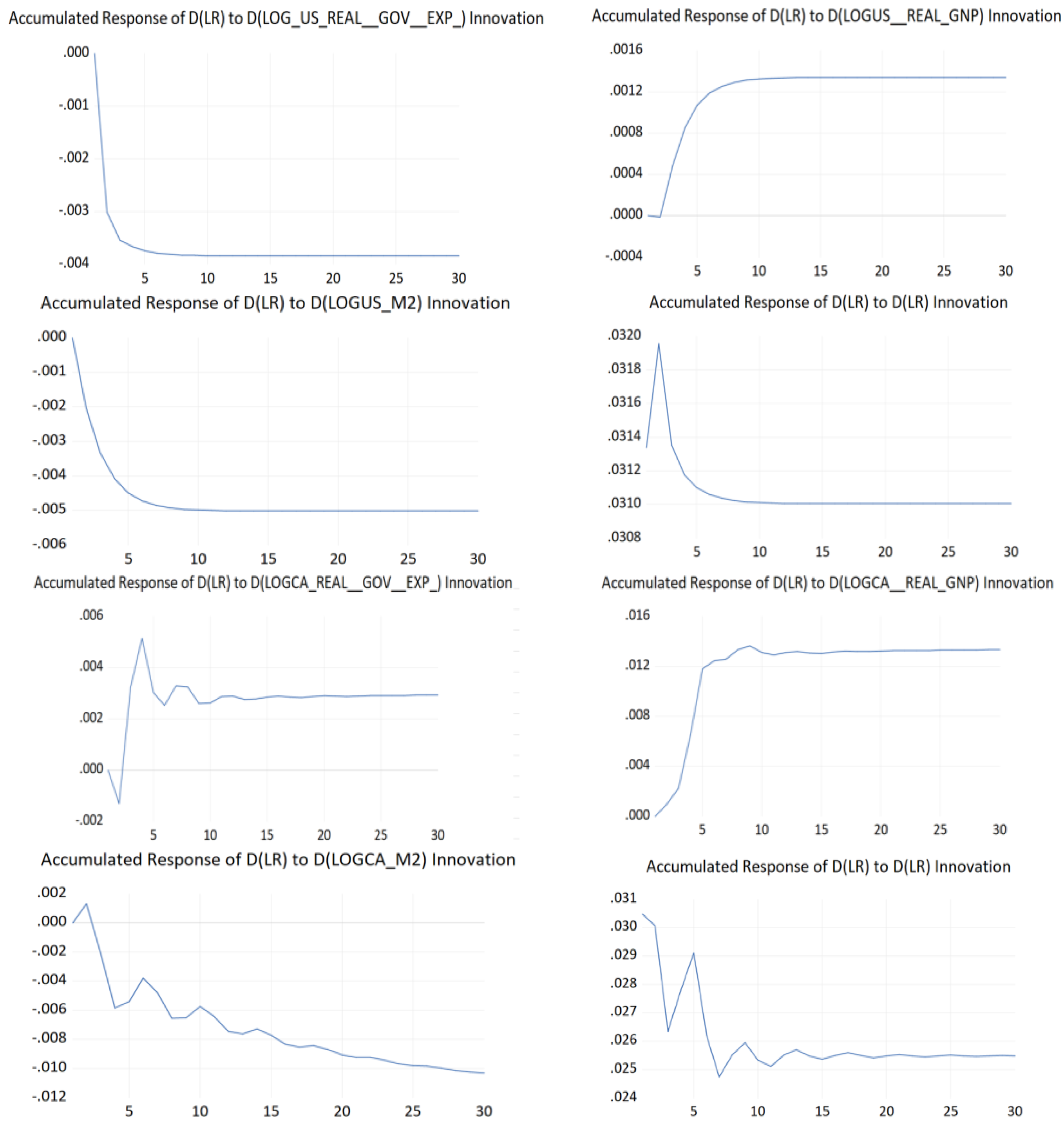

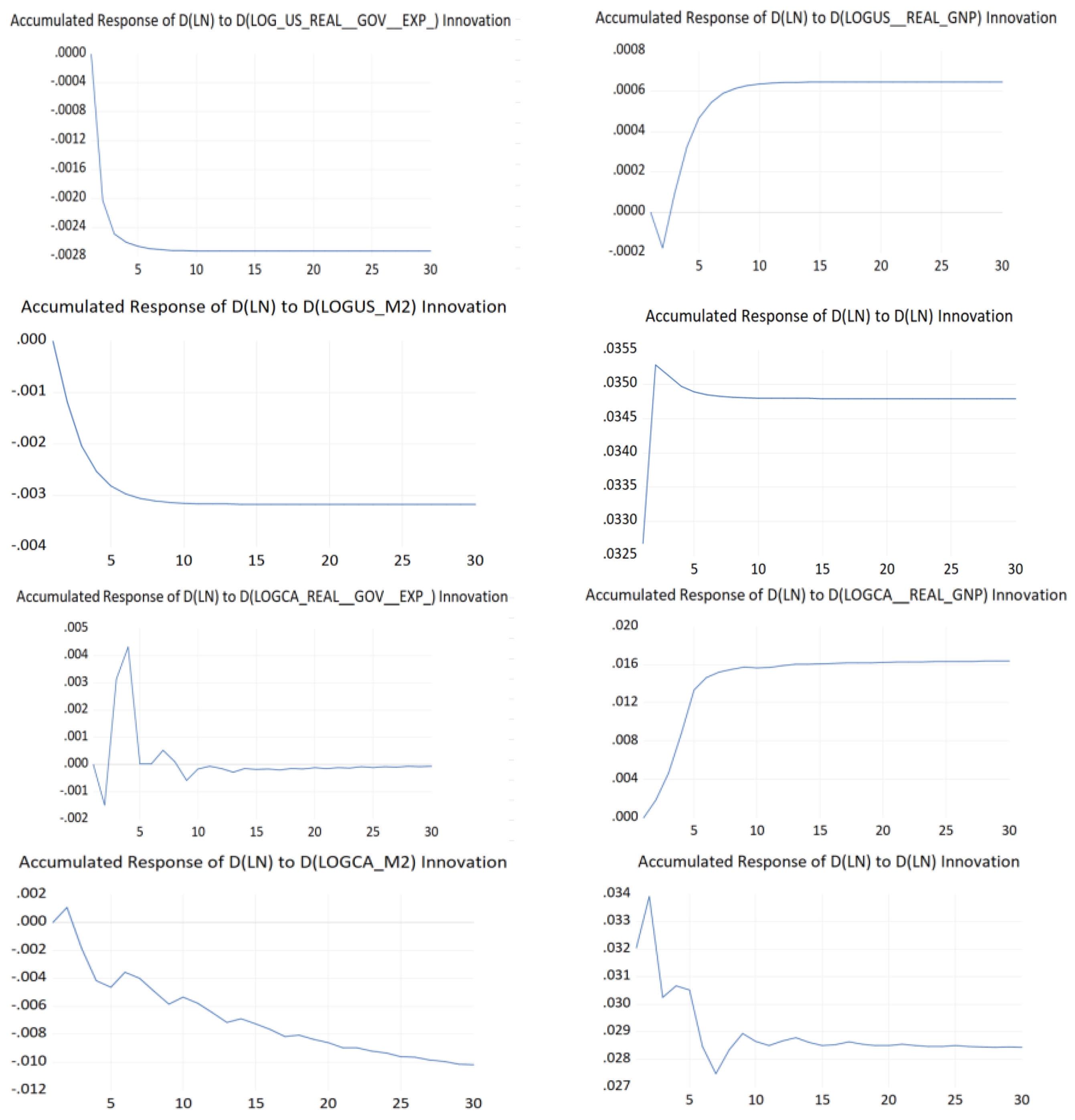

5.3. Impulse Responses

5.4. Real and Nominal Shocks

6. Conclusive Remarks

References

- Moulle-Berteaux, C. (2023). Global Multi-Asset Viewpoint: The Five Forces of Secular Inflation. Morgan Stanley Investment Management. https://www.morganstanley.com/im/publication/insights/articles/article_thefiveforcesofsecularinflation.pdf.

- Factset (2024). Investment Research. https://www.factset.com/solutions/investment-research.

- Chicago Mercantile Exchange Group. (2024). Crude oil futures and options. CME Group. https://www.cmegroup.com/markets/energy/crude-oil/light-sweet-crude.html.

- Gurrib, I.; Kamalov, F.; Starkova, O.; Makki, A.; Mirchandani, A.; & Gupta, N. (2023). Performance of Equity Investments in Sustainable Environmental Markets. Sustainability, 15(9), 7453. [CrossRef]

- Plotnick, A.R. (1963). Oil Imports: Protectionism Vs. National Security, Challenge, 11(6), 28-32. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40718665.

- Sánchez, J.J.G. (2023, August 16). American Protectionism: Can It Work? Epicenter At the Heart of Research and Ideas, Harvard University. https://epicenter.wcfia.harvard.edu/blog/american-protectionism-can-it-work.

- Lee, C.C., & Hussain, J. (2023). An assessment of socioeconomic indicators and energy consumption by considering green financing, Resources Policy, 81, Article 103374. [CrossRef]

- Sokhanvar, A., & Lee, C.-C. (2023). How do energy price hikes affect exchange rates during the war in Ukraine?. Empirical economics, 64(5), 2151-2164. [CrossRef]

- Natural Resources Canada (2023). Energy Factbook 2023-2024. https://energy-information.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/energy-factbook-2023-2024.pdf.

- International Energy Agency. (2022). Canada 2022: Energy Policy Review. https://www.iea.org/reports/canada-2022.

- Global Affairs Canada (2020, February 26). The Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement: Economic impact assessment. https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/assets/pdfs/agreements-accords/cusma-aceum/cusma-impact-repercussion-eng.pdf.

- Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. (n.d.). Oil and Natural Gas in Canada. https://www.capp.ca/energy/canadas-energy-mix/.

- Government of Canada (2024). Coal facts. https://natural-resources.canada.ca/our-natural-resources/minerals-mining/mining-data-statistics-and-analysis/minerals-metals-facts/coal-facts/20071.

- Canada Nuclear Safety Commission (2023). Regulatory Action. https://www.cnsc-ccsn.gc.ca/eng/acts-and-regulations/regulatory-action/impala-canada-ltd/.

- Canada Action (2024). Environmental Leadership in Natural Resources. https://www.canadaaction.ca/climate_action.

- Kim, J. O. and Enders, W. (1991). Real and monetary causes of real exchange rate movements in the Pacific rim. Southern Economic Journal, 57, 1061-1070. [CrossRef]

- Baillie, R.T., & McMahon, P.C. (1989) The foreign exchange market: theory and econometric evidence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dibooglu, S. & Enders, W. (1995) Multiple cointegrating vectors and structural economic models: an application to the French Franc/US Dollar exchange rate. Southern Economic Journa, 61(4), 1098-1116. [CrossRef]

- Butt, S., Ramzan, M., Wong, W-K., Chohan, M. A., & Ramakrishnan, S. (2023). Unlocking the secrets of exchange rate determination in Malaysia: A Game-Changing hybrid model. Heliyon, 9, Article e19140. [CrossRef]

- Meese, R.A., & Rogoff, K. (1983). Empirical exchange rate models of the seventies: do they fit out of sample? Journal of International Economics, 14(1–2), 3–24. [CrossRef]

- Frankel, J.A., & Rose, A.K. (1995). Empirical research on nominal exchange rates, Handbook of International Economics, 3, 1689–1729. [CrossRef]

- Enders, W., & Lee, B.-S. (1997). Accounting for real and nominal exchange rate movements in the post-Bretton Woods period. Journal of International Money and Finance, 16(2), 233-254. [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, O.J., & Quah, D. (1988). The Dynamic Effects of Aggregate Demand and Supply Disturbances (Working paper No. 2737). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w2737/w2737.pdf.

- Ji, Q., Shahzad, S. J. H., Bouri, E., & Suleman, M. T. (2020). Dynamic structural impacts of oil shocks on exchange rates: lessons to learn. Journal of Economic Structures, 9(20), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Malik, F., & Umar, Z. (2019). Dynamic connectedness of oil price shocks and exchange rates. Energy Economics, 84, Article 104501. [CrossRef]

- Gurrib, I., & Kamalov, F. (2019). The implementation of an adjusted relative strength index model in foreign currency and energy markets of emerging and developed economies, Macroeconomics and Finance in Emerging Market Economies, 12(2), 105-123. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y., Dong, Z., & An, H. (2023). Study of the modal evolution of the causal relationship between crude oil, gold, and dollar price series. International Journal of Energy Research, 2023, Article 7947434. [CrossRef]

- Dogru, T., Isik, C., & Sirakaya-Turk, E. (2019). The balance of trade and exchange rates: Theory and contemporary evidence from tourism. Tourism Management, 74, 12-23. [CrossRef]

- Avdjiev, S., Du, W., Koch, C., & Shin, H. S. (2019). The dollar, bank leverage, and deviations from covered interest parity. American Economic Review: Insights, 1(2), 193-208. [CrossRef]

- Bussière, M., Gaulier, G., & Steingress, W. (2020). Global trade flows: Revisiting the exchange rate elasticities. Open Economies Review, 31, 25-78. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, V., & Shin, H. S. (2023). Dollar and exports. The Review of Financial Studies, 36(8), 2963-2996. [CrossRef]

- Eichenbaum, M. S., Johannsen, B. K., & Rebelo, S. T. (2021). Monetary policy and the predictability of nominal exchange rates. The Review of Economic Studies, 88(1), 192-228. [CrossRef]

- Gründler, D., Mayer, E., & Scharler, J. (2023). Monetary policy announcements, information shocks, and exchange rate dynamics. Open Economies Review, 34(2), 341-369. [CrossRef]

- Gürkaynak, R. S., Kara, A. H., Kısacıkoğlu, B., & Lee, S. S. (2021). Monetary policy surprises and exchange rate behavior. Journal of International Economics, 130, Article 103443. [CrossRef]

- Bénétrix, A. S., & Lane, P. R. (2013). Fiscal shocks and the real exchange rate. 32nd issue of the International Journal of Central Banking. 1-32. https://www.ijcb.org/journal/ijcb13q3a1.htm.

- Hanif, W., Mensi, W., Alomari, M., & Andraz, J. M. (2023). Downside and upside risk spillovers between precious metals and currency markets: Evidence from before and during the COVID-19 crisis. Resources Policy, 81, Article 103350. [CrossRef]

- Sokhanvar, A., Çiftçioglu, S., & Lee, C.-C. (2023). The effect of energy price shocks on commodity currencies during the war in Ukraine, Resources Policy, 82, Article 103571. [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R., Hanson, S.G., Stein, J. C., & Sunderam, A. (2023). A quantity-driven theory of term premia and exchange rates. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 138(4), 2327-2389. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, L. A., & Huh, H.-S. (2002). Real exchange rates, trade balances and nominal shocks: evidence for the G-7. Journal of International Money and Finance, 21(4), 497-518. [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, P. K., Chawla, M., Ghosh, P., Singh, S., & Singh, P. K. (2022). FOREX trend analysis using machine learning techniques: INR vs USD currency exchange rate using ANN-GA hybrid approach. Materials Today: Proceedings, 49, 3170-3176. [CrossRef]

- Youssef, M., & Mokni, K. (2020). Modeling the relationship between oil and USD exchange rates: Evidence from a regime-switching-quantile regression approach. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 55, Article 100625. [CrossRef]

- Adaramola, A. O., & Dada, O. (2020). Impact of inflation on economic growth: evidence from Nigeria. Investment Management & Financial Innovations, 17(2), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Mussa, M. (1976). Adaptive and regressive expectations in a rational model of the inflationary process. Journal of Monetary Economics, 1(4), 423-442. [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, J. A. (1976). Inflation and the Formation of Expectations. Journal of Monetary Economics, 1(4), 403-421. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S. (1995). The response of real exchange rates to various economic shocks. Southern Economic Journal, 936-954. [CrossRef]

- Sarno, L., & Taylor, M. P. (2001). Official intervention in the foreign exchange market: is it effective and, if so, how does it work?. Journal of Economic Literature, 39(3), 839-868. [CrossRef]

- Lane, P. R., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2007). The external wealth of nations mark II: Revised and extended estimates of foreign assets and liabilities, 1970–2004. Journal of international Economics, 73(2), 223-250. [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, M., & Seccareccia, M. (2006). The Bank of Canada and the modern view of central banking. International Journal of Political Economy, 35(1), 44-61. [CrossRef]

- Bouakez, H., & Eyquem, A. (2015). Government spending, monetary policy, and the real exchange rate. Journal of International Money and Finance, 56, 178-201. Get rights and content. [CrossRef]

- Gurrib, I., & Kamalov, F. (2022). Predicting bitcoin price movements using sentiment analysis: a machine learning approach. Studies in Economics and Finance, 39(3), 347-364. [CrossRef]

- Kamalov, F., Gurrib, I., & Rajab, K. (2021). Financial forecasting with machine learning: price vs return. Journal of Computer Science, 17(3), 251-264. [CrossRef]

- Kamalov, F., & Gurrib, I. (2022). Machine learning-based forecasting of significant daily returns in foreign exchange markets. International Journal of Business Intelligence and Data Mining, 21(4), 465-483. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y., Chen, Z., Liu, S., & Li, Y. (2024). Unveiling the potential: Exploring the predictability of complex exchange rate trends. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 133, Article 108112. [CrossRef]

- Arias, J. E., Rubio-Ramírez, J. F., & Waggoner, D. F. (2018). Inference based on structural vector autoregressions identified with sign and zero restrictions: Theory and applications. Econometrica, 86(2), 685-720. [CrossRef]

- Carriero, A., Clark, T. E., & Marcellino, M. (2019). Large Bayesian vector autoregressions with stochastic volatility and non-conjugate priors. Journal of Econometrics, 212(1), 137-154. [CrossRef]

- Kilian, L. (2013). Structural vector autoregressions. In N. Hashimzade & M. A. Thornton (Eds.),.

- Handbook of research methods and applications in empirical macroeconomics (pp. 515-554). Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, C., & Hamilton, J. D. (2019). Structural interpretation of vector autoregressions with incomplete identification: Revisiting the role of oil supply and demand shocks. American Economic Review, 109(5), 1873-1910. [CrossRef]

- Charfeddine, L., & Barkat, K. (2020). Short-and long-run asymmetric effect of oil prices and oil and gas revenues on the real GDP and economic diversification in oil-dependent economy. Energy Economics, 86, Article 104680. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Meng, L., & Wang, Y. (2020). Oil price shocks and Chinese economy revisited: New evidence from SVAR model with sign restrictions. International Review of Economics & Finance, 69, 20-32. [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, B. F., Hesami, S., Rjoub, H., & Wong, W. K. (2021). Interpretation of oil price shocks on macroeconomic Aggregates of South Africa: Evidence from SVAR. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government, 27(1), 279-287. https://cibgp.com/au/index.php/1323-6903/article/view/558/526.

- Suhendra, I., & Anwar, C. J. (2022). The response of asset prices to monetary policy shock in Indonesia: A structural VAR approach. Banks and Bank Systems, 17(1), 104-114. [CrossRef]

- Yilmazkuday, H. (2023). COVID-19 effects on the S&P 500 index. Applied Economics Letters, 30(1), 7-13. [CrossRef]

- Carrière-Swallow, Y., Magud, N.E., & Yépez, J.F. (2021). Exchange rate flexibility, the real exchange rate, and adjustment to terms-of-trade shocks. Review of International Economics; 29 (2): 439–483. [CrossRef]

- Kelesbayev, D., Myrzabekkyzy, K., Bolganbayev, A., & Baimaganbetov, S. (2022). The impact of oil prices on the stock market and real exchange rate: The case of Kazakhstan. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 12(1), 163-168. https://www.econjournals.com/index.php/ijeep/article/view/11880/6201. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A. H., Pentecost, E. J., & Stack, M.M. (2023). Foreign aid, debt interest repayments and Dutch disease effects in a real exchange rate model for African countries. Economic Modelling, 126, Article 106434. [CrossRef]

- Demir, F., & Razmi, A. (2022). The real exchange rate and development theory, evidence, issues and challenges. Journal of Economic Surveys, 36(2), 386-428. [CrossRef]

- Gurrib, I. & F. Kamalov (2019). The implementation of an adjusted relative strength index model in foreign currency and energy markets of emerging and developed economies, Macroeconomics and Finance in Emerging Market Economies, 12:2, 105-123. [CrossRef]

- Bank for International Settlements (2022). Triennial Central Bank Survey. Bank of International Settlements. https://www.bis.org/statistics/rpfx22.htm.

- King, R.G., & Watson, M.W. (1992). Testing Long Run Neutrality., (Working paper No. 4156). National Bureau of Economic Research. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. (2020, November, 20-22). Research on the linkage relationship between different levels of money supply and economic growth based on VAR model. 2020 2nd International Conference on Economic Management and Model Engineering (ICEMME), Chongqing, China. [CrossRef]

- Tan, E. C., Tang, C. F., & Palaniandi, R. D. (2022). What could cause a country’s GNP to be greater than its GDP?. The Singapore Economic Review, 67(02), 557-566. [CrossRef]

- Dornbusch, R. (1976). Expectations and exchange rate dynamics. Journal of political Economy, 84(6), 1161-1176. [CrossRef]

| WPI_CA | WPI_US | Nominal USDCAD | Real USDCAD |

WPI-US/ WPI-CA |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 391.678 | 330.030 | 1.237 | 1.043 | 0.849 | |

| Median | 401.115 | 310.709 | 1.244 | 1.052 | 0.856 | |

| Standard deviation | 142.439 | 121.213 | 0.158 | 0.088 | 0.057 | |

| Kurtosis | -0.331 | -0.602 | -0.650 | -0.783 | -0.549 | |

| Skewness | -0.049 | 0.190 | 0.083 | -0.075 | 0.250 | |

| Jarque-Bera | 1.019 | 4.319 | 3.843 | 5.427 | 4.713 | |

| p-value | 0.601 | 0.115 | 0.146 | 0.066 | 0.095 | |

| ADF | -0.358 | 0.244 | -0.1250 | -2.5970 | -2.6080 | |

| p-value | 0.9124 | 0.9747 | 0.2350 | 0.0953 | 0.0930 | |

| Observations | 205 | 205 | 205 | 205 | 205 | |

| US Real Gov. Exp. | CA Real Gov. Exp. | US Real GNP | CA Real GNP | US Money Supply |

CA Money Supply |

|

| Mean | 2,752 | 336 | 13.230 | 1.120 | 6,483.614 | 706.313 |

| Median | 2,709 | 313 | 12 | 0.905 | 4,184.100 | 449.658 |

| Standard deviation | 669 | 84 | 5 | 0.750 | 5,543.982 | 639.924 |

| Kurtosis | -1.267 | -0.864 | -1.265 | -0.766 | 0.765 | 0.639 |

| Skewness | -0.199 | 0.353 | 0.186 | 0.546 | 1.258 | 1.229 |

| Jarque-Bera | 15.068 | 10.634 | 14.853 | 15.187 | 59.052 | 55.070 |

| p-value | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| ADF | -0.4620 | 1.5730 | 1.4430 | 2.9980 | 2.7830 | 3.7530 |

| p-value | 0.8946 | 0.9995 | 0.9991 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Observations | 205 | 205 | 205 | 205 | 205 | 205 |

| WPI_CA | WPI_US | Nominal USDCAD | Real USDCAD | WPI-US/WPI-CA | US Real Gov. Exp. | CA Real Gov. Exp. | US Real GNP | CA Real GNP | US Money supply | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WPI_US | 0.988 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| Nominal USDCAD | 0.301 | 0.183 | 1.000 | |||||||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||

| Real USDCAD | 0.238 | 0.174 | 0.881 | 1.000 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.012 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||||

| WPI-US/WPI-CA | (0.328) | (0.187) | (0.795) | (0.421) | 1.000 | |||||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||

| US Real Gov. Exp. | 0.957 | 0.955 | 0.196 | 0.130 | (0.256) | 1.000 | ||||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.063 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| CA Real Gov. Exp. | 0.968 | 0.988 | 0.135 | 0.155 | (0.118) | 0.961 | 1.000 | |||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.026 | 0.092 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| US Real GNP | 0.965 | 0.975 | 0.184 | 0.187 | (0.159) | 0.973 | 0.982 | 1.000 | ||

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| CA Real GNP | 0.962 | 0.982 | 0.133 | 0.169 | (0.089) | 0.945 | 0.991 | 0.988 | 1.000 | |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.058 | 0.016 | 0.206 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| US Money supply | 0.905 | 0.930 | 0.123 | 0.216 | (0.013) | 0.857 | 0.952 | 0.928 | 0.966 | 1.000 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.078 | 0.000 | 0.855 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| CA Money supply | 0.906 | 0.934 | 0.117 | 0.215 | (0.002) | 0.858 | 0.955 | 0.927 | 0.967 | 0.998 |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.096 | 0.000 | 0.978 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Variable | ∆RER | ∆RER | ∆NER | ∆NER |

| Shock | ||||

| 1-quarter | 98.489 | 1.511 | 80.153 | 19.847 |

| 3-quarters | 97.589 | 2.411 | 80.311 | 19.689 |

| 5-quarters | 97.588 | 2.412 | 80.311 | 19.689 |

| 7-quarters | 97.588 | 2.412 | 80.311 | 19.689 |

| 9-quarters | 97.588 | 2.412 | 80.311 | 19.689 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).