1. Introduction

In this study, the characteristics of the epikarst, the role of these characteristics, the effect of its presence or lack on surface feature development and by this, its impact on the landscape of different karst types is investigated on different climatic karst types.

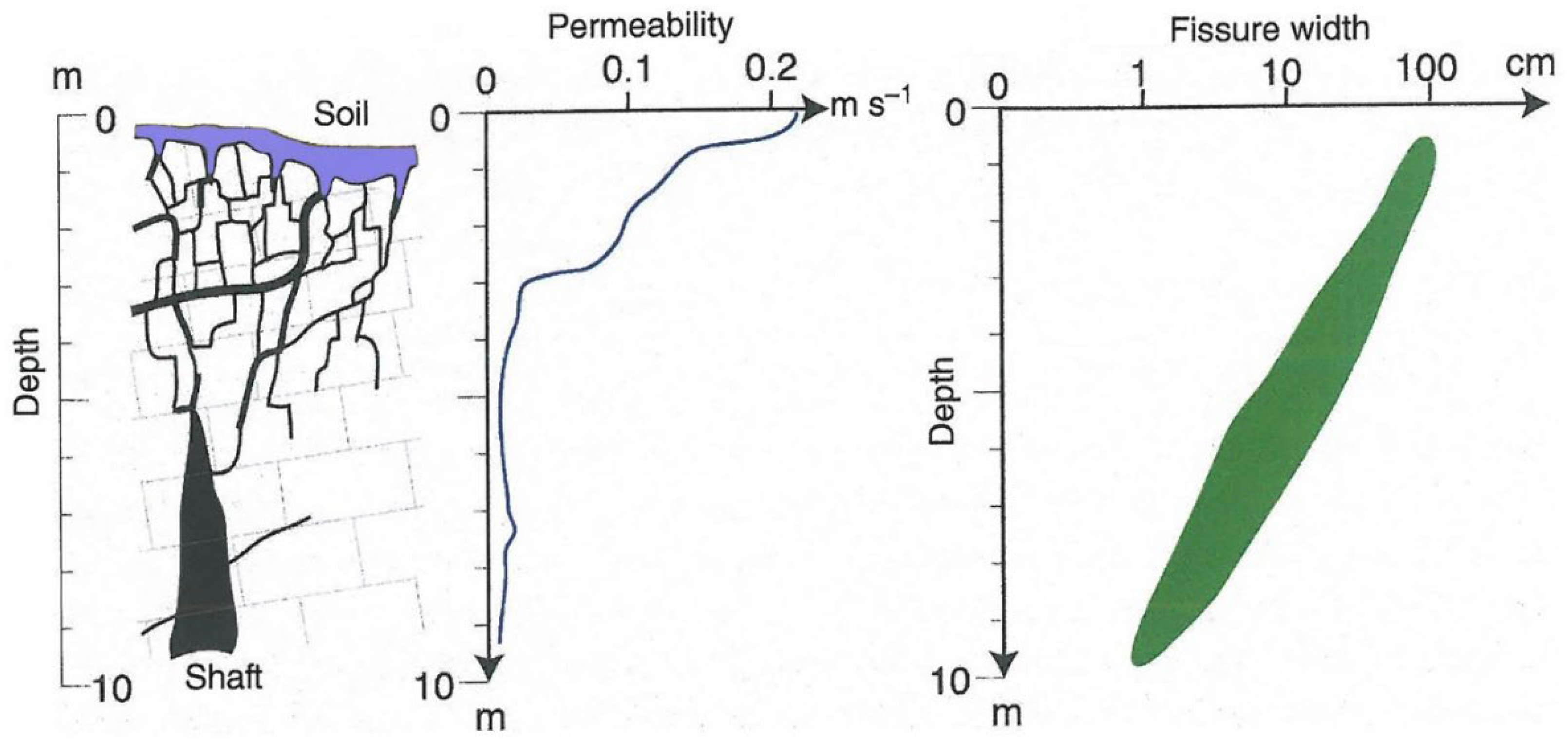

Epikarst is the upper, surface, karren, or subsurface part of the karst with cavities [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6], where secondary porosity may reach 10-20 % [

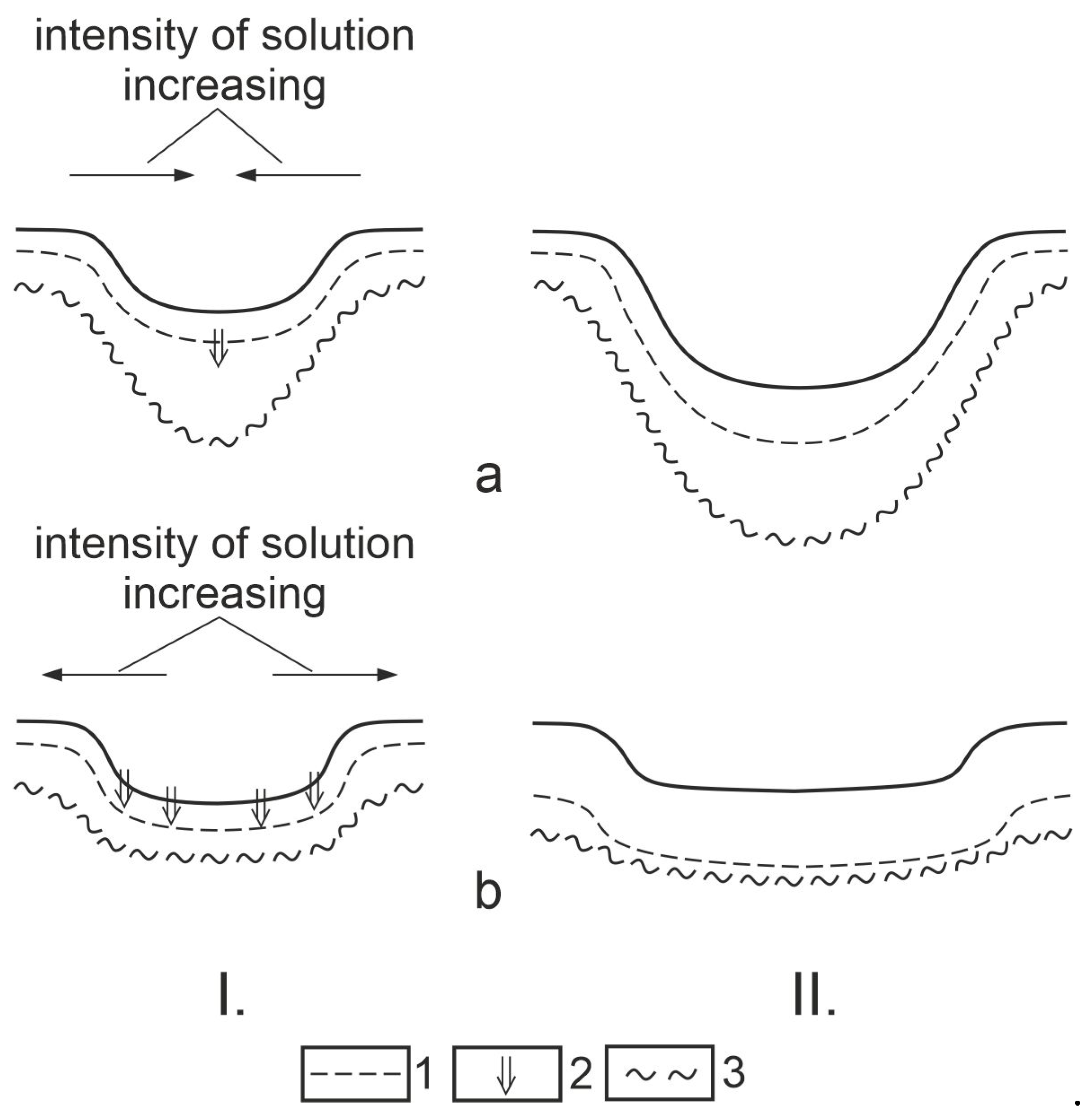

7]. Some of its characteristics are shown in

Figure 1. The infiltrating water is stored in the cavities (these develop along the bedding planes and fractures below karren) of the epikarst. At its saturation level, which is the lower surface of the epikarst, infiltration decreases because the cavity formation is of low degree below this level (1-2 %). The water swells back thus, it creates the piezometric surface [

1,

5], below which there is permanent water fill in the epikarst. The piezometric level may fluctuate depending on the degree of water supply or it may be permanently modified (for example due to the increase of the degree of cavity formation). Its thickness ranges from 10 m to 30 m [

6,

7,

8]. Recent epikarst, paleoepikarst [

7], and incipient epikarst [

9] are distinguished.

The karren-free part of the epikarst with cavities and the karstwater may develop variously relative to each other and to the surface. The wet part of the epikarst may occur close to the bedrock surface or at a deeper position [

10]. The karstwater, particularly if its level is increased significantly, may occupy the epikarst temporarily (katavotra), or permanently for example below glaciers [

11,

12,

13]. At other sites, the epikarst does not develop at all, in spite of the fact that the karstwater table is deep below the surface. According to Williams [

7], at sites where the rock is of high primary porosity (20-45 %) instead of horizontal water motion, the vertical is predominant. However, it also occurs that no epikarst develops in the case of lower primary porosity either. On the pseudotectonic grike walls, on the Eocene limestone of Mount Bocskor in the Bakony Region (Hungary), [

14] there are no solution cavities and karren are absent on the rock surface. The cavities of the epikarst may open up for example by glacial erosion [

7], or the epikarst may become inactive (because no water with dissolution capacity reaches it).

In our studied areas, the VES measurements penetrated into a depth of 3-20 m in the bedrock. Since the epikarst is at this depth, the resistivity values of this depth interval provide information on the characteristics of the epikarst such as on the degree of cavity formation in the epikarst, or the position and the pattern of the piezometric surface.

There is a strong relationship between the climate and the size, density and diversity of surface karst features: the above parameters of karst features are increasing towards the Equator since the duration of precipitation, the amount of precipitation (except the dry, desert areas) and the temperature are also increasing in this direction [

15]. In this study, the terms used for the studied climatic karst types are based on the nomenclature of Jakucs [

16], Ford and Williams [

17], Veress and Vetési-Foith [

15]: taiga karst, the karsts of areas of middle latitude (with cool summer, then with hot summers in eastern direction), Mediterranean and subtropical karst, tropical rainforest karst, tropical savanna karst, tropical monsoon karst and glaciokarst.

Some karst features occur on all climatic karst types (karren, dolines), while others only occur on some types (poljes, inselberg karst and its feature assemblages, tropical karren). Based on their size, karren may be microkarren, mesokarren, and megakarren [

18]. Mesokarren, particularly their karren of flow origin (rinnenkarren) may be significant water suppliers of the epikarst. Tropical karren consist of remnant features (pinnacles) and grikes with an expansion of several tens of meters. Its varieties are tsingy (Madagascar), stone forest (China), a pinnacle karst (Sarawak), and pinnacle-arête karst (New-Guinea) and in Australia, the tropical monsoon karst [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

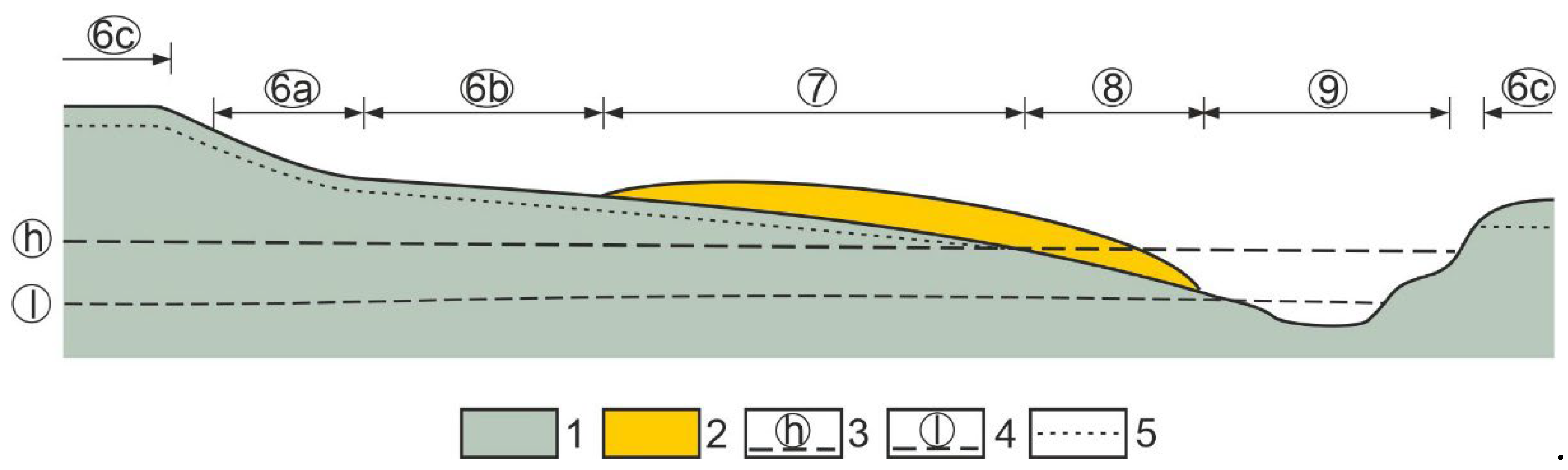

Solution dolines develop on soil-covered karst, subsidence dolines are formed on covered karst (thus, their development not only climate-dependent, but it also depends on the presence of the caprock). Among solution dolines, drawdown dolines develop at those sites of the epikarst where water drainage is increased (

Figure 2), point recharge dolines are formed at the increased infiltrations of valley floors and inception dolines develop at the impermeable beds intercalated into the rock [

7,

17,

26]. Subsidence dolines are formed by collapse (dropout doline), by suffosion (suffosion doline), by compaction (compaction doline) and by sagging of the cover, sagging sinkholes develop [

27,

28,

29,

30].

Poljes are widespread on Mediterranean and subtropical karsts, but they also occur on glaciokarsts [

31,

32,

33]. They can be classified based on their morphology, genetics and hydrology [

6,

17,

31,

32,

33].

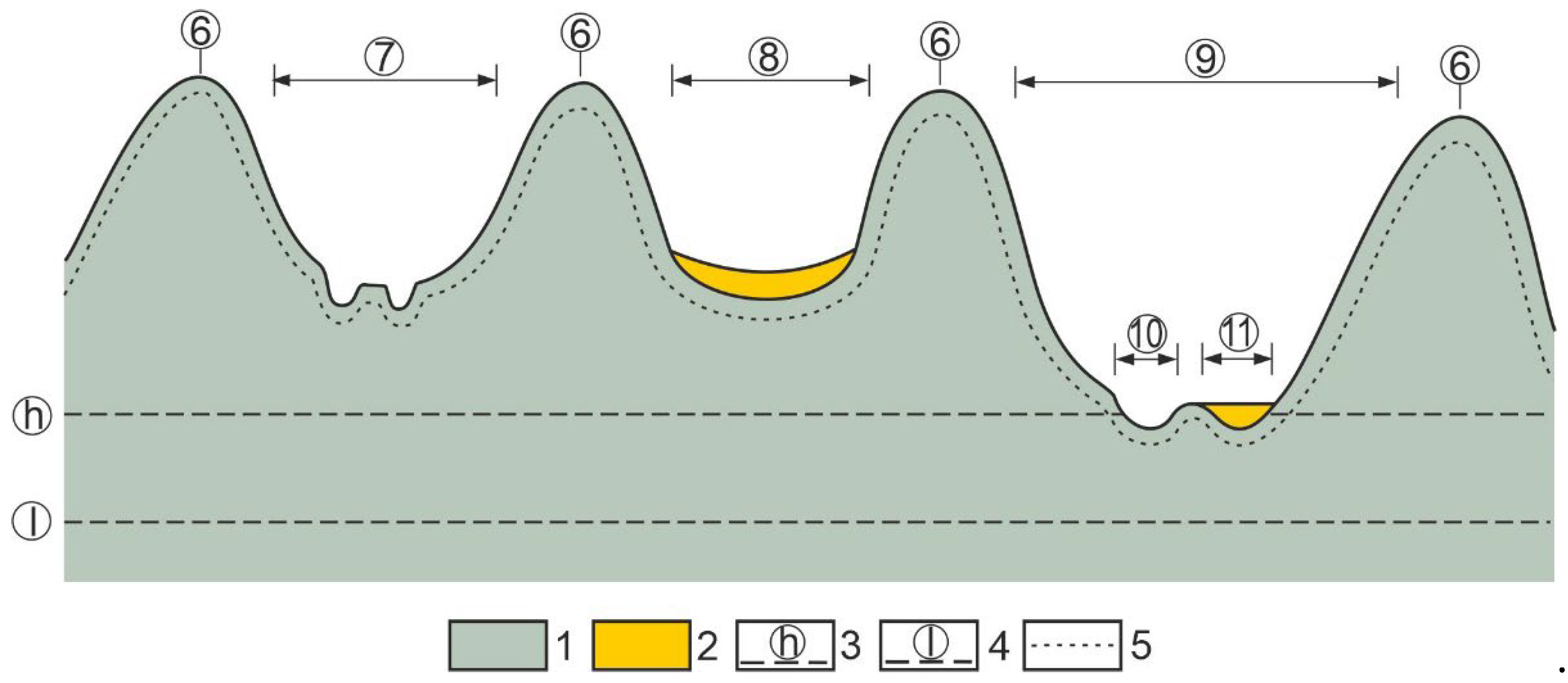

Inselberg karst develop in tropical areas (under tropical rainforest climate, tropical savanna climate and tropical monsoon climate). Its varieties are fengcong, where there are mountains with a common base, with depressions between the mounts and the fenglin, where the mounts are solitary surrounded by intermountain plains (with subsidence dolines on them) [

23,

31,

34,

35,

36,

37]. The varieties of fengcong are the polygonal karst, cockpit karst, but according to the altitudinal occurrence of fengcong, several varieties are also distinguished [

23,

36].

On glaciokarsts, the features of glacial erosion and the karstic landscape are mixed and develop partially on each other. Due to the vertical zonality of the climate, the appearance of the features is also zonal. At lower altitudes, active drawdown dolines occur, while at higher elevations, there are drawdown paleodolines and schachtdolines [

13]. Since the caprock is limestone debris, saturation may already take place in it [

31,

38] and thus, the epikarst is not active at such sites. Subsidence dolines, karren and shafts are widespread.

In the development of some karst features, only the epikarst plays a role for example in the case of drawdown dolines [

7,

28]), while in the development of other features the epikarst and the karstwater have a mutual effect (poljes). However, other karst features may also be formed, in the development of which, the karstwater has an important role for example in the case of Bemaraha Tsingy [

25], tropical monsoon karst [

20,

21], or fenglin [

37], and the role of the epikarst is subordinate or does not exist at all.

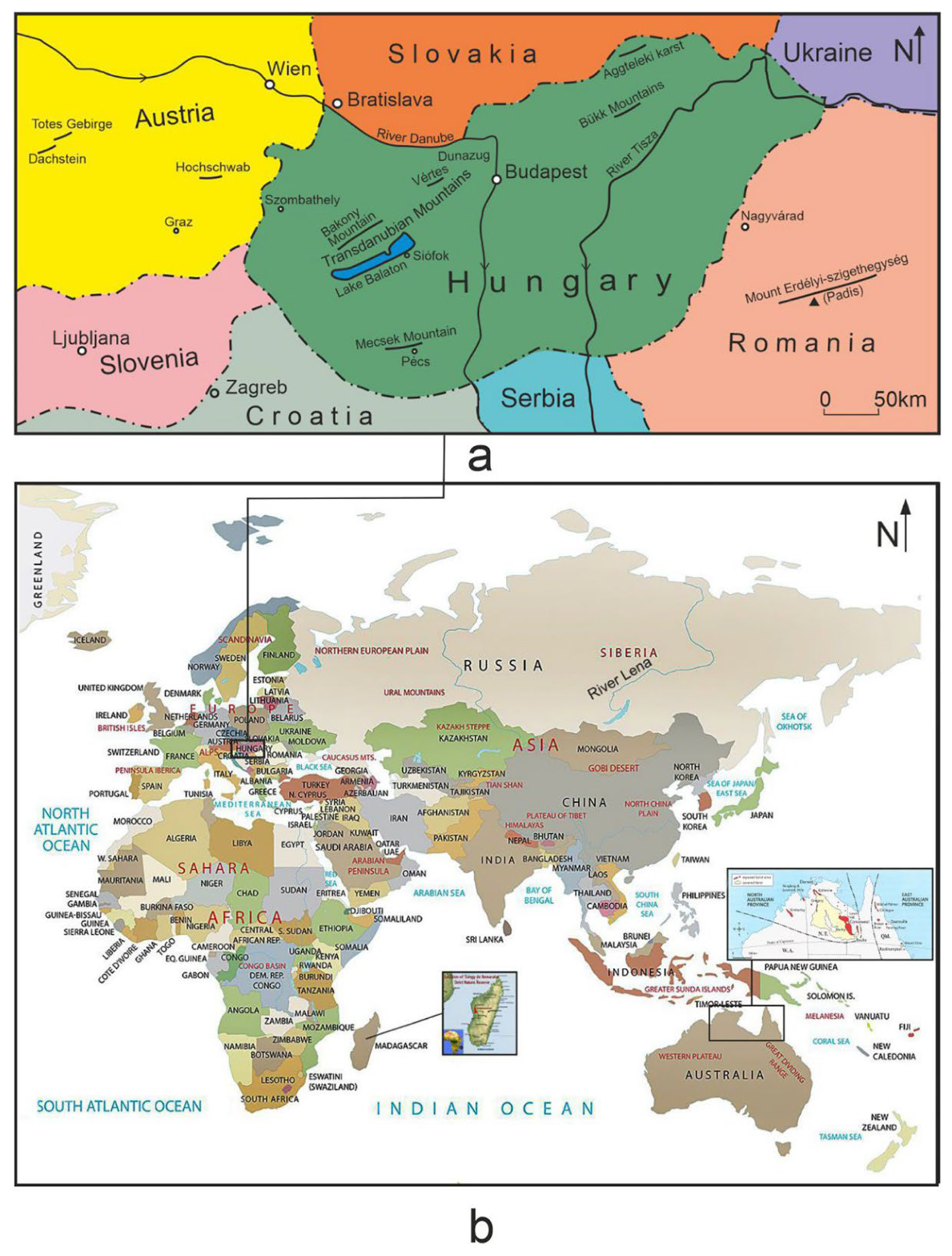

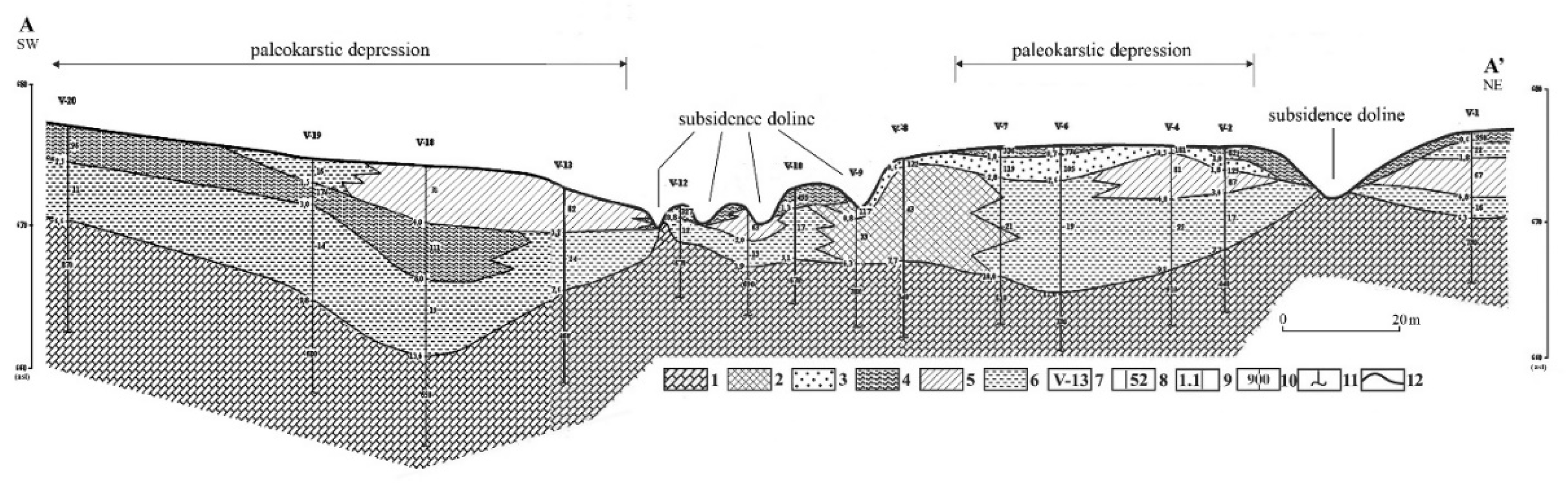

2. Measurement areas (Figure 3)

Aggtelek Karst (Hungary) is mantled mountains built up of Triassic gypsum-anhydrite and carbonate rocks [

39]. It is separated into plateaus by epigenetic valleys, in which, but also on the surfaces between the valleys, several drawdown dolines can be found [

40]. The profile of the VES measurement was made through two dolines of a drawdown doline row of an epigenetic valley.

The Bakony Region (Hungary) is a part of the Transdanubian Mountains, which is situated in a northern direction from Lake Balaton. The mountains are built up of blocks, which are mainly constituted by Triassic dolomite, on which Dachstein Jurassic, Cretaceous, and Eocene limestone patches occur in smaller expansion. Its surface is covered by clayey gravel and loess and their reworked, mixed varieties in widespread distribution [

39]. The drawdown dolines are paleo features, but subsidence dolines are widespread [

40]. The profiles, along which the measurements were made, went through subsidence dolines as well. Such measurements were made on an epigenetic valley floor on Tés Plateau, at the Eleven-Förtés doline group (which is borne by a larger, partly filled drawdown doline) in the area of Mester-Hajag North (here in an area between limestone mounds), at the margin of Fehérkő Valley (on a terrain between mounds) and a doline group of Homód Valley (floor of epigenetic valley).

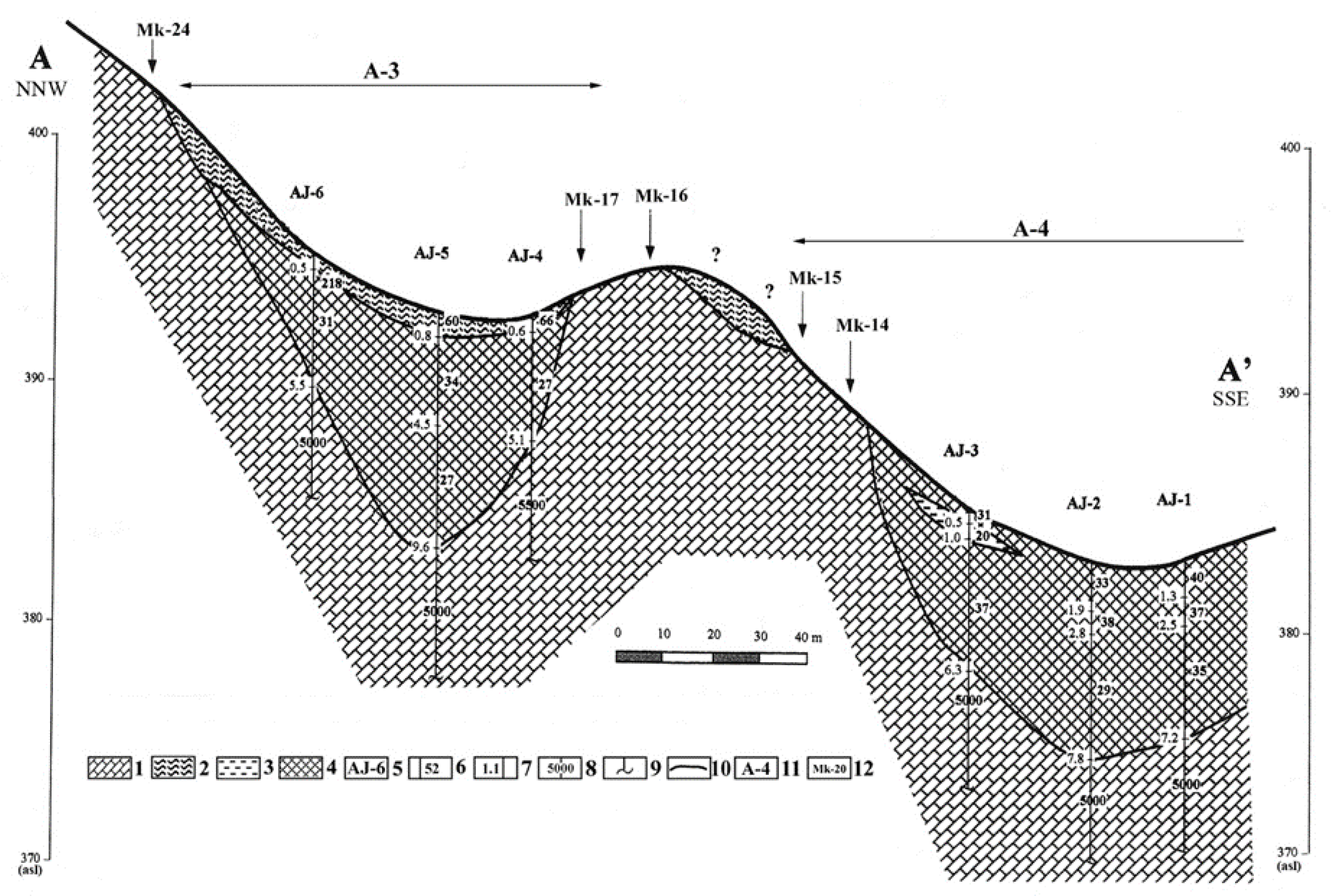

The central part of the Bükk Mountains (Hungary) is a plateau, which is mostly built up of Triassic mantles [

39]. Drawdown dolines are widespread on valley floors and on mounds too [

40]. The VES measurements were made in a doline with flat floor of Zsidó-rét (Great Plateau).

The Labija Valley is a tributary valley of River Lena (Yakutia, Russia) with intermittent stream. The environs of the Lena is built up of Cambrian and Silurian limestones and dolomites [

41], its environs are covered by sand and clay on the interfluves. On the cover, subsidence dolines also occur. The Labija Valley is wide, plate-shaped or of plain floor. Its eastern slope is dissected by pillars. Solution dolines (drawdown dolines) are aligned in the channel of the valley floor. The area is of subarctic climate thus, permafrost is widespread.

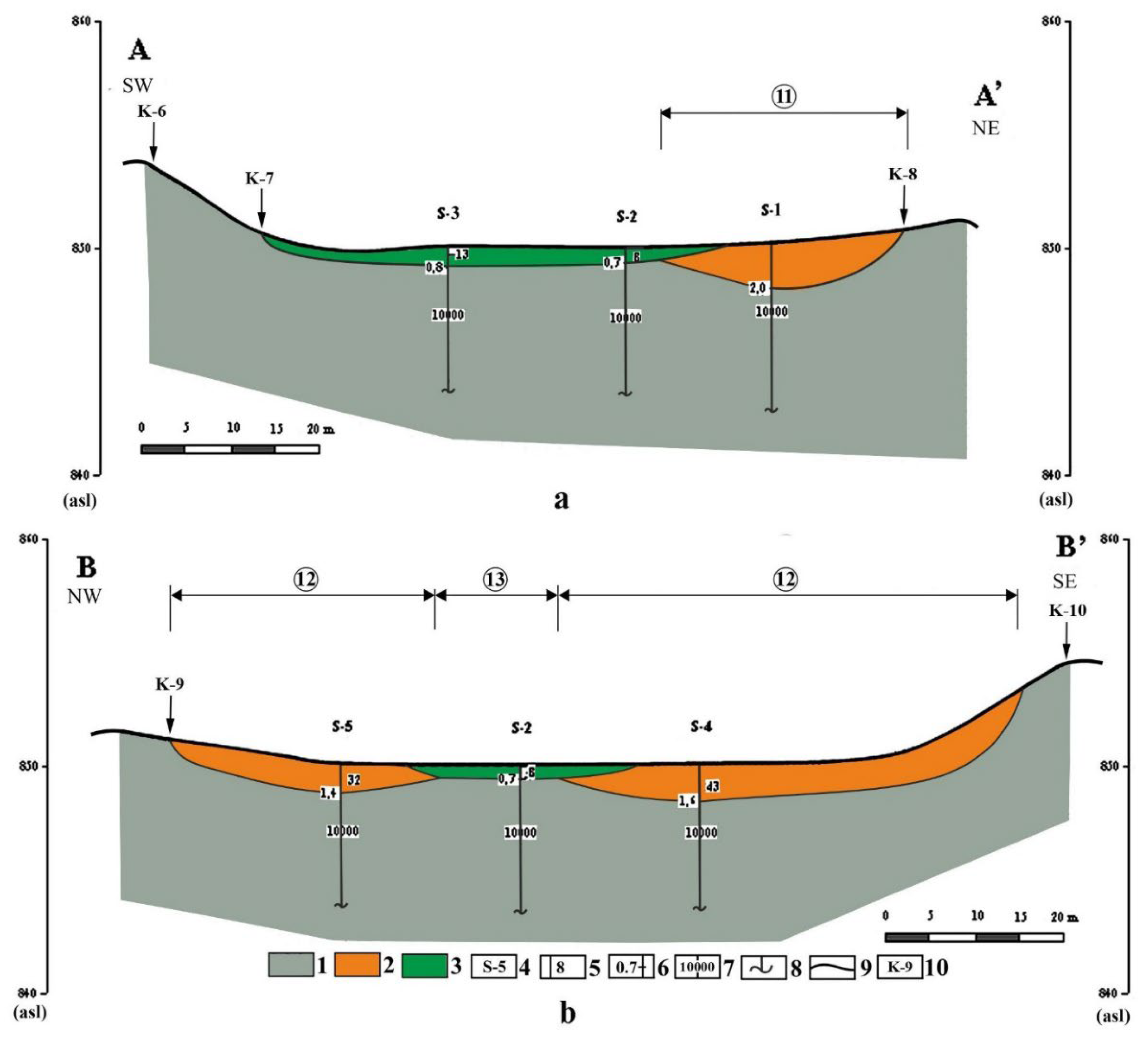

Padis Plateau is part of the Bihar Mountains (Romania). The plateau is built up of Triassic and Jurassic limestones [

42]. Here, large drawdown dolines are widespread, but on its covered karst patches (some of them are in drawdown dolines) several subsidence dolines also occur. The material of the cover is sandstone debris, which accumulated during fluvial transportation. The VES profiles were made in the area of a large (with a diameter of about 400 m), old depression with flat floor (Rǎchite) and on the floor of an epigenetic valley. On both measurements sites, there are many subsidence dolines, but in the area of Rǎchite, depressions are also widespread on the bedrock.

The Western Mecsek Karst (Hungary) is built up of Middle Triassic limestone, which is covered by loess in continuous development and its sandy, clayey varieties. Its karst features are the drawdown dolines which constitute rows and subsidence dolines. The subsidence dolines occur in drawdown dolines, but also outside them. On the karst, the doline density is high, it may also reach 80 dolines/km2 [

43]. Some VES profiles were made in drawdown dolines, while others outside them. The latter profiles crossed subsidence dolines.

Totes Gebirge, Dachstein and Hochschwab are parts of the Northern Limestone Alps and structurally the surviving parts of the Upper Austroalpine Nappe [

44,

45,

46]. The large depressions of glaciokarst areas are paleodolines [

13] in which moraine of limestone material and cover of frost weathering origin can be found. Several small subsidence dolines may have developed on this. The VES measurements were made in paleodolines, which also crossed subsidence dolines.

During the study of inselberg karst, the data of Chinese tropical karsts were taken into consideration based on literary data.

When studying tropical karren, the data of Bemaraha Tsingy, the Australian monsoon karst and one of the Tanzanian Karsts (Tanga Karst) were used [

20,

21,

25,

47].

Bemaraha Tsingy (Madagascar) is separated into Great Tsingy and Little Tsingy, the latter is cut through by River Manambolo. It developed on Jurassic limestones. Blocks, large grikes and pinnacles are predominant on the tsingy [

25]. According to Salomon [

48], the primary porosity of the bearing rock is 1-2 %.

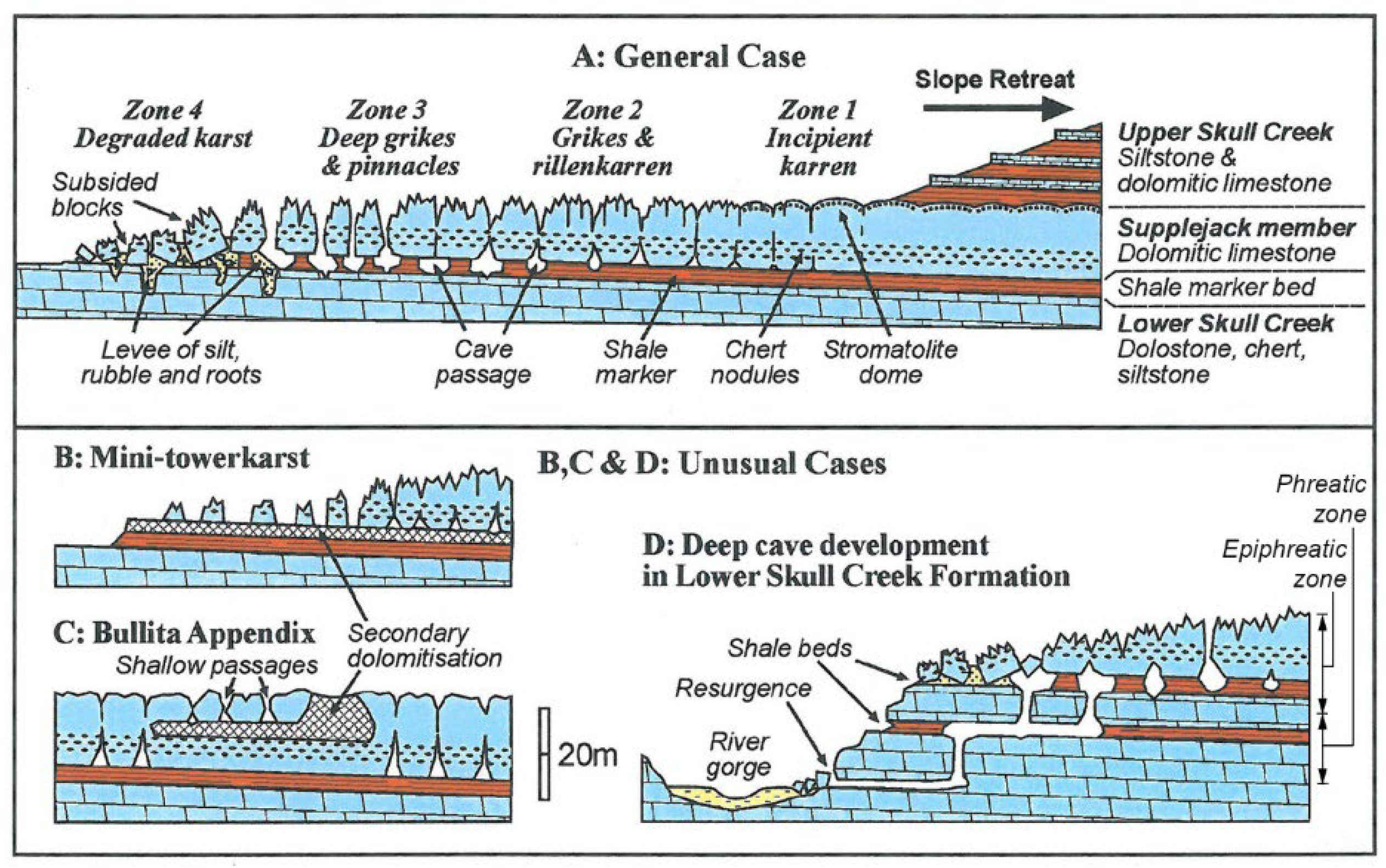

Grimes [

49] claims that North Australian tropical karren are characterized by the low altitude of their surface, low primary porosity, tropical monsoon climate and they are densely packed with fractures. These karsts are large grikes, where features of karstwater origin occur on the grike walls and the grikes are connected to caves that developed below the karstwater table.

Several grikes occur on Tanga Karst (Tanzania), which developed on Jurassic limestone (here, the rock is also of low porosity) and it is karst close to the coast. On the walls of grikes there are bedding-planes caves. The grikes were connected with karstwater caves by collapses [

47].

3. Methods

The distribution of drawdown dolines was mapped in a permafrost area in the valley of one of the tributary rivers of River Lena. The sites of VES measurements (see below) were also mapped.

VES measurements were carried out in active drawdown dolines on the karsts of Răchite, Aggtelek Karst, Bükk Mountains, and the Western Mecsek and in the paleodolines (inactive drawdown dolines) of glaciokarsts by the colleagues of the Terratest Ltd. VES measurements were also made along profiles crossing subsidence dolines on covered karsts (Bakony Region, Western Mecsek Karst, Pádis). However, since the subsidence dolines are of small size, mostly only some VES measurements were made and only some sites were suitable for more measurements (at most three). Geoelectric-geological profiles were prepared with the use of the measurement data. The theory of VES measurement can be read in the work by Veress [

50].

The average resistivity of the bedrock below the drawdown dolines of various karst areas was calculated. The pattern of resistivity was analysed below the drawdown dolines in horizontal and vertical directions. Thus, the average resistivity values were calculated in the centre and marginal parts of the dolines in Western Mecsek Karst.

Average resistivity values were calculated in the dolines and of their environs in the case of the subsidence dolines of five sample sites in the Bakony Region. The quantity of water getting into the karst in these areas was estimated and calculated. The average resistivity below thirty subsidence dolines was also compared with the average resistivity of the bearing profiles of the dolines, here. Taking into consideration the estimated water quantity of the studied areas and the relation between the resistivities below the dolines and the average resistivities of their environments, doline groups were made.

The average resistivity values being calculated at depressions with drawdown dolines were compared with the averages of the resistivity of covered karsts (with subsidence dolines). In the area of Răchite, Padis where the terrain with drawdown dolines was also covered, average resistivity values measured at the plain bedrock and at the bedrock with mounds were compared.

The relationship between the resistivity values of the cover and the bedrock below the small subsidence dolines of glaciokarsts was analysed.

The relationship between hydrology and karstification was studied in poljes and on inselberg karsts with the use of literary data.

On tropical karren with large grikes (Bemaraha Tsingy, Tanga karst, Australian monsoon karst), the position of the karstwater table relative to the karst surface, and the annual distribution of precipitation was also studied in this area.

4. Results

Based on the mapping of the Labija Valley, drawdown dolines are small and are aligned on the channel floor and in its environs (

Figure 4).

1. drawdown doline, 2. intermittent stream of channel

The resistivity values of the bedrock are varied and different at the places of VES measurements. Below the drawdown doline floors of the temperate belt, either covered by soil or superficial deposit, the resistivity values are high (they exceed 5000 Ohmm). Below the paleodolines of glaciokarsts, resistivity values above 5000 Ohmm, but below this value also occur (

Table 1). At the subsidence dolines of covered karsts and in their environs, the resistivity values are lower (they are below 5000 Ohmm,

Table 2). Extremely low resistivity values occur at the subsidence dolines of the Bakony Region [

10], or at the subsidence dolines of the paleodolines of glaciokarsts, but the resistivity values are higher at the subsidence dolines of the covered karst of Padis. Based on the resistivity values of the Bakony Region, the sample sites can be put into two groups. A group involves those with extremely low resistivity (the average resistivity is some 100 Ohmm, such as at the subsidence dolines of Tés Plateau, the Eleven-Förtés doline group and Homód-valley), their epikarst receives more water, and the surface is more karstified, here. The average resistivity exceeds 1000 Ohmm at those belonging to the other group (Mester-Hajag North, the margin of Fehérkő Valley). The epikarst of these areas receives less water and their surface is less karstified [

10],

Table 2).

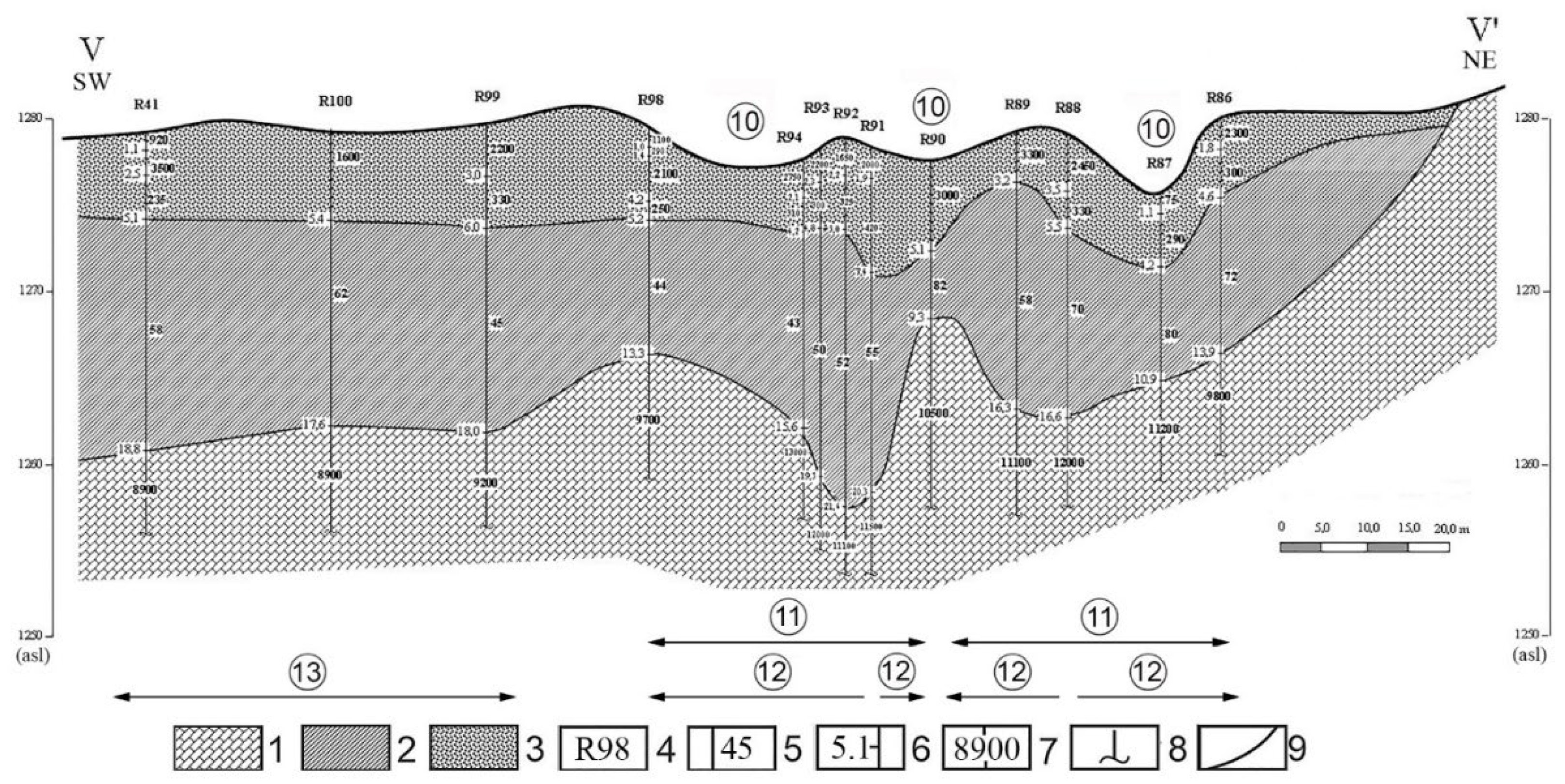

The resistivity values below drawdown dolines may be decreasing, the same, or irregularly changing from the doline centre towards the margins. The decrease is particularly well represented by the inner and marginal average resistivity values of dolines in the area of the Western Mecsek Karst (

Figure 5,

Table 1). (However, it may occur in some cases when resistivity is lower below the doline centre which can probably be explained by the fact that the cavities above the piezometric level are filled.) The resistivity values may decrease towards the margins even if the doline is infilled and covered (Padis,

Figure 6). However, subordinately in some cases the resistivity is lower below the centre of the doline, which may presumably be explained by the fill of the cavities above the piezometric level. On glaciokarsts (Dachstein), the resistivity of the bedrock may also change vertically. Here, the resistivity values of the cover between the dolines exceed the resistivity values of the cover below the small subsidence dolines of glaciokarsts. Below subsidence dolines and in the bedrock of their environment, the resistivity values are not only low, but the resistivity values below the dolines in the bedrock and the differences of the resistivity values of their environment are also low. The resistivity values are low in the bedrock below the dolines in absolute sense as well (

Figure 7). However, on glaciokarsts, in the area of the main depression of the bedrock or at a smaller bedrock depression within this, the decrease of the resistivity towards the margins cannot be experienced, their distribution is irregular (

Figure 8).

In the area of the larger depression bearing the Eleven-Förtés doline group, where there are infilled and buried depressions on the bedrock, the resistivity values are not decreasing towards to margins (

Figure 9,

Figure 10).

Drawdown dolines, the bedrock of which is flat-floored (

Figure 11) [

51], or of uvala-like pattern (

Figure 12) also occur, but at them, the resistivity values are the same or if they are not, they slightly change.

In the Bakony Region, the resistivity values below subsidence dolines (there is no depression on the bedrock at these features) were compared with the resistivity values of the bearing profile. The average resistivity below 12 dolines out of 30 studied dolines was higher, and in 11 cases it was lower than the average of the resistivity values measured along the bearing profiles. There was a shaft on the floor of seven dolines, where no VES measurements were possible to be made (

Table 3,

Table 4). Both among dolines with bedrock resistivity values higher or lower than their environment, there are dolines which are in areas richer in water and poorer in water (

Table 4). While the superficial deposit was of suffosion structure in the case of the above dolines, the subsidence dolines above the infilled drawdown dolines of Padis developed by the deflection of the cover beds.

The katavotra of Cirknitz polje were studied in a detailed way. It can be established that here, the high karstwater table reaches some part of the polje floor. (There is a depression on the cover, but there is no depression on the bedrock.) Katavotra constitute a passage group, around them various karren occur (

Figure 13), but there are also subsidence dolines here. Farther, the polje floor has permanently drier parts (dry polje part), and at other parts there is a lake (permanently wet polje part).

There is dissected epikarst in the area of fengcong karst. The drawdown dolines with different depth approach the karstwater table to a different degree. In some dolines, even low karstwater table may appear [

23], while the floor of other dolines is above the high karstwater table [

17,

34,

35,

52]. The appearance of the karstwater in the depressions indicates that the epikarst is not everywhere and not always present at poljes and at the drawdown dolines of fengcong. At sites, where it is present, it is of different elevation. It is of higher elevation on plateaus and on inselbergs (fengcong), and of lower elevation in the poljes and drawdown dolines.

Subsidence dolines develop in large numbers on weathering residue and fluvial stream load, on the intermountain plains of fenglin karst [

29,

53]. The karstwater table is at the bedrock of the intermountain plain [

34,

37]. Since due to water pumping, the frequency of subsidence doline development increases [

53,

54,

55], there is a close relationship between the natural or artificial subsidence of the karstwater table and doline development. This refers to at least a temporary lack of the epikarst in the area of intermountain plains.

Some tropical karren areas were selected where features that developed below the former karstwater table in the side of grikes can be found [

20,

21,

25,

47]. At these karren, the karswater table was above the grike floors for a shorter and longer duration. The closeness of the karstwater table to the grike floors is indicated by the fact that a basin with permanent water occurs on Bemaraha Little Tsingy, the level of which fluctuates during the flood events of River Manambolo [

25]. The former or current presence of the karstwater also refer to the temporary presence of the epikarst.

In the studied karren areas, the elevation difference between the karst surface and the karstwater table never exceeds 100 m and the minimum difference is larger than 50 m only in two cases (

Table 4). The elevation differences would be even lower than the values included in the table if we regarded the elevation difference between the grike floors and the karstwater table. The features of the grike walls that developed below the karstwater table refer to the former or current more elevated level of the karstwater table [

25].

On these tropical karren, the amount of precipitation is varied, but its annual distribution is extremely uneven (

Table 5,

Table 4). The precipitation amount of the wettest months only makes up 20-30 % of the annual amount of precipitation with the exception of one case (this is Tanga Karst, where the values of precipitation amounts are high in every month). Grimes [

20] emphasizes that in the case of the North Australian tropical karren, the majority of precipitation falls during intensive, short thunderstorms or during rains with a duration of several days. However, based on the data of Wikipedia, 1141 mm precipitation fell in January close to Broken River karsts (in the town of Townsville). Thus, in wet months there is a high chance of intensive rainfall. According to our calculations, at a grike with a width of 0.1 m, which may receive the water running down a surface part with a 5-5 m width, if the fractures occur in every 10 m, a water column with a height of 10.1 m develops in the grike in the case of 100 mm precipitation. Thus, the karstwater table may also become elevated at the grike floor in such a degree to the effect of the accumulated rainwater.

6. Conclusions

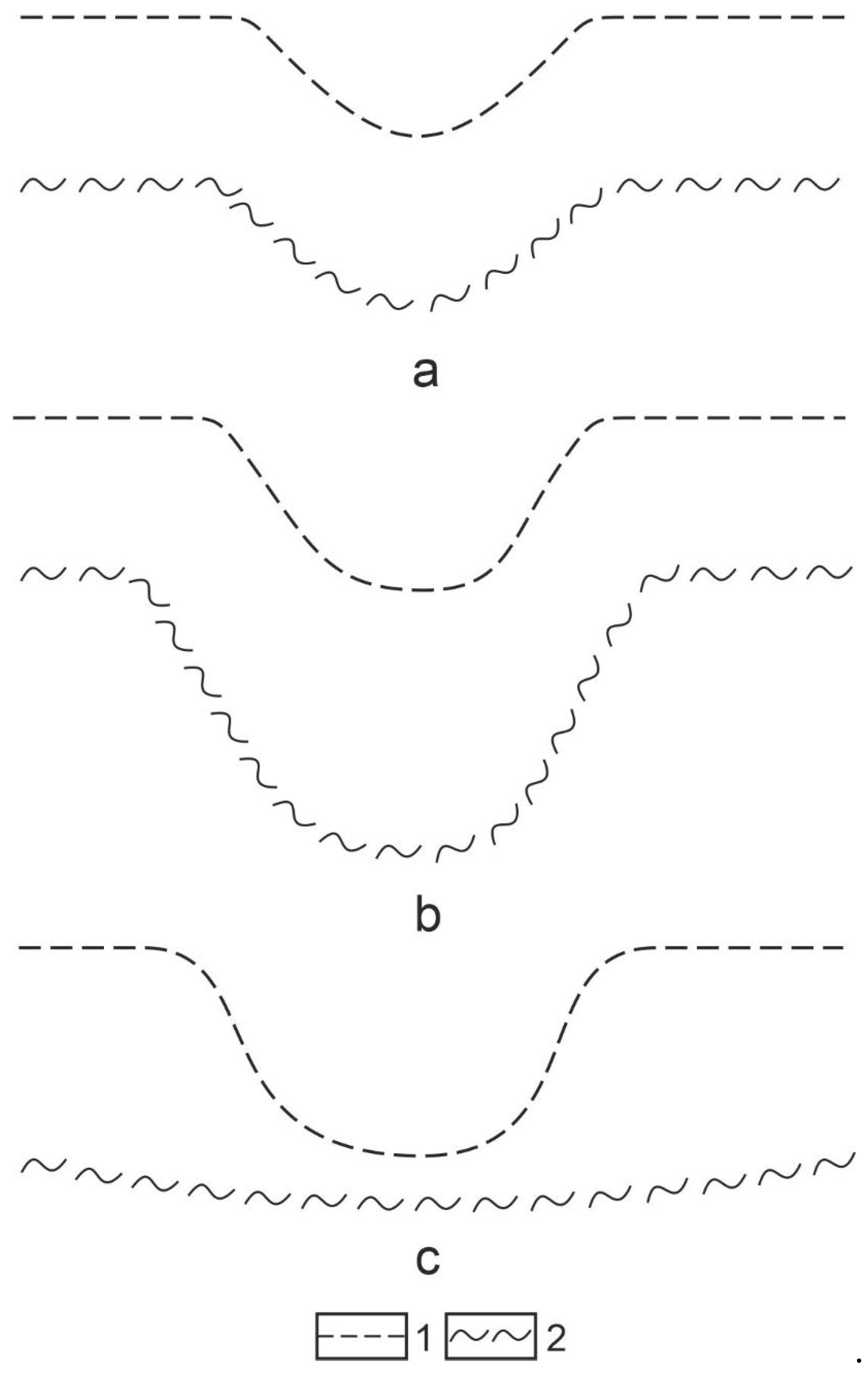

In addition to the primary porosity of the rock, the quantity and distribution of precipitation and the water supply of the cover (if there is any) determines the cavity index of the epikarst and its horizontal heterogeneity.

The piezometric surface may be subsurface or of a deeper position relative to that. In the case of an epikarst with more cavities, it is of deeper position. In the latter case, the resistivity is high. The degree of the cavity formation in the epikarst may be homogeneous and heterogeneous. The homogeneous degree of cavity formation retards and restricts surface feature development and feature diversity, while the heterogeneous degree of cavity formation intensifies it. The heterogeneous degree of cavity formation may be horizontally or vertically developed. The heterogeneous degree of cavity formation develops from the homogeneous degree of cavity formation, during which mostly drawdown dolines are formed, the heterogenous degree of cavity formation may develop into homogeneous degree of cavity formation when the development of drawdown dolines stops.

The piezometric surface may be separating into parts, uniform, dissected by subsidences, parallel with the surface or non-parallel with it. It may be parallel with the saturation level or it may not (in the latter case, the distance between them may be smaller or larger than in their environment).

The epikarst may be of limited expansion (tundra karst, on epigenetic valley floor), expanded, truncated, temporary and double (lower inactive). Bands and patches with or without epikarst (or only temporarily epikarst-free) may alternative next to each other. Thus, areas with drawdown dolines may alternate, in the case of superficial deposit, with bands and patches of subsidence dolines, with subsidence dolines of katavotra, and with permanent water cover in the area of poljes or in the dolines of fengcong. On glaciokarsts, the recent epikarst of terrains being exempt from limestone debris alternates with terrains of paleokarst and paleodolines covered with limestone debris, where below the latter there is epikarst being denuded to a different degree, which is not active.

On fenglin karst, since the epikarst is replaced by karstwater, covered karst may develop, while on the studied tropical karren, the epikarst occupied the area of grikes and this state ceases when the grikes are connected with cavities.

Figure 1.

Theoretical pattern of the epikarst and some of its characteristics in the function of depth [

6].

Figure 1.

Theoretical pattern of the epikarst and some of its characteristics in the function of depth [

6].

Figure 2.

Drawdown doline and epikarst development [

7].

Figure 2.

Drawdown doline and epikarst development [

7].

Figure 3.

sites of VES measurements (a) areas studied by mapping and by literary data (b).

Figure 3.

sites of VES measurements (a) areas studied by mapping and by literary data (b).

Figure 4.

Drawdown dolines of the channel of Labija Valley.

Figure 4.

Drawdown dolines of the channel of Labija Valley.

Figure 5.

Resistivity values along a profile with a drawdown doline from the Western Mecsek Karst area. Legend: 1. boundary of the mountains, 2. contour line, 3. outcrop, 4. trace of profile location, 5. limestone, 6. limestone debris (sandy?), 7. sand, sandy silt, 8. clay (with limestone debris, clayey), 9. sand-loess (with limestone debris), 10. site and number of VES measurement, 11. geoelectric resistivity of beds (Ohmm), 12. base depth of geoelectric series, 13. geoelectric resistivity of bedrock (Ohmm), 14. approximate penetration of VES measurement, 15. geoelectric series boundary, 16. road, 17. subsidence doline, 18. drawdown doline, 19. resistivity decreases.

Figure 5.

Resistivity values along a profile with a drawdown doline from the Western Mecsek Karst area. Legend: 1. boundary of the mountains, 2. contour line, 3. outcrop, 4. trace of profile location, 5. limestone, 6. limestone debris (sandy?), 7. sand, sandy silt, 8. clay (with limestone debris, clayey), 9. sand-loess (with limestone debris), 10. site and number of VES measurement, 11. geoelectric resistivity of beds (Ohmm), 12. base depth of geoelectric series, 13. geoelectric resistivity of bedrock (Ohmm), 14. approximate penetration of VES measurement, 15. geoelectric series boundary, 16. road, 17. subsidence doline, 18. drawdown doline, 19. resistivity decreases.

Figure 6.

Drawdown dolines on the bedrock of Răchite (Padis [

12]). Legend: 1, limestone, 2, clayey silt, 3, mixed rock debris (sand, sandstone and limestone debris), 4. VES measurement site, 5, geoelectric resistivity of the series (Ohmm), 6, basal depth of geoelectric series (m), 7, geoelectric resistivity of the bedrock (Ohmm), 8, approximate penetration of the VES measurement, 9. boundary of geoelectric series, 10, subsidence doline, 11. drawdown doline, 12. resistivity decreases, 13. plain bedrock.

Figure 6.

Drawdown dolines on the bedrock of Răchite (Padis [

12]). Legend: 1, limestone, 2, clayey silt, 3, mixed rock debris (sand, sandstone and limestone debris), 4. VES measurement site, 5, geoelectric resistivity of the series (Ohmm), 6, basal depth of geoelectric series (m), 7, geoelectric resistivity of the bedrock (Ohmm), 8, approximate penetration of the VES measurement, 9. boundary of geoelectric series, 10, subsidence doline, 11. drawdown doline, 12. resistivity decreases, 13. plain bedrock.

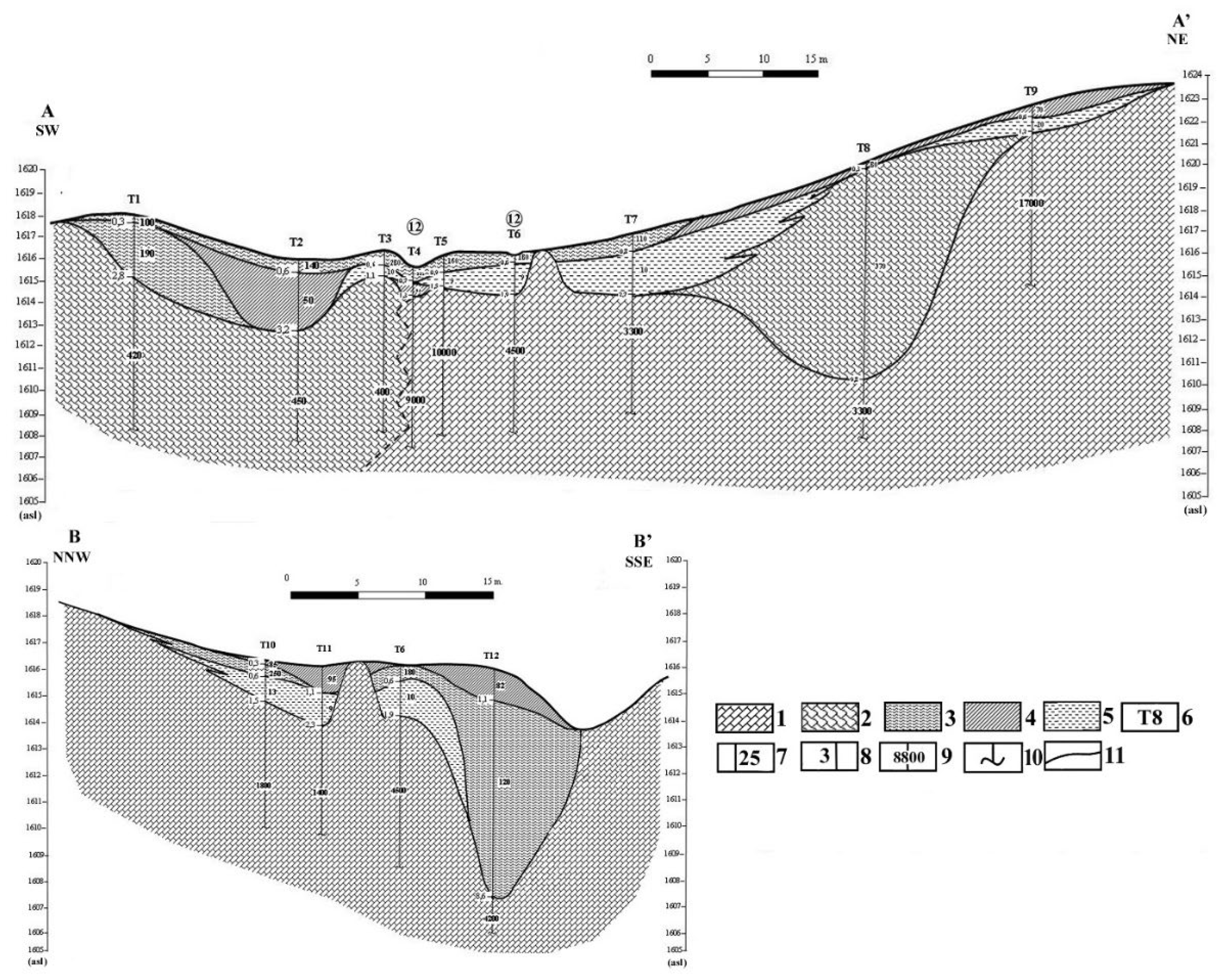

Figure 7.

Section of the geoelectric-geological profile marked A-A’ from the area of a paleodoline [

12]) Legend: 1. limestone, 2. limestone debris, 3. clay with limestone debris, 4. identification code of VES measurement, 5. geoelectric resistivity of series (Ohmm), 6. base depth of geoelectric series (m), 7. geoelectric resistivity of the bedrock (Ohmm), 8. approximate penetration depth of VES measurement, 9. boundary of geoelectric series, 10. series of higher resistivity relative to its environment, 11. subsidence doline.

Figure 7.

Section of the geoelectric-geological profile marked A-A’ from the area of a paleodoline [

12]) Legend: 1. limestone, 2. limestone debris, 3. clay with limestone debris, 4. identification code of VES measurement, 5. geoelectric resistivity of series (Ohmm), 6. base depth of geoelectric series (m), 7. geoelectric resistivity of the bedrock (Ohmm), 8. approximate penetration depth of VES measurement, 9. boundary of geoelectric series, 10. series of higher resistivity relative to its environment, 11. subsidence doline.

Figure 8.

Geological profiles of a paleodoline (Totes Gebirge, Tauplitz alm [

12]). Legend: 1. limestone, 2. limestone debris (fragmented limestone), 3. limestone debris (clayey), 4. clay with limestone debris, 5. clay, 6. identification code of VES measurement, 7. geoelectric resistivity of the series (Ohmm), 8. base depth of geoelectric series (m), 9. geoelectric resistivity of bedrock (Ohmm), 10. approximate penetration of measurement, 11. geoelectric series boundary, 12. subsidence doline.

Figure 8.

Geological profiles of a paleodoline (Totes Gebirge, Tauplitz alm [

12]). Legend: 1. limestone, 2. limestone debris (fragmented limestone), 3. limestone debris (clayey), 4. clay with limestone debris, 5. clay, 6. identification code of VES measurement, 7. geoelectric resistivity of the series (Ohmm), 8. base depth of geoelectric series (m), 9. geoelectric resistivity of bedrock (Ohmm), 10. approximate penetration of measurement, 11. geoelectric series boundary, 12. subsidence doline.

Figure 9.

The VES profile going through the Eleven-Förtés doline group. Legend: 1. contour line, 2. profile, 3. wet area, 4. site of VES measurement, 5. rock outcrop and its mark, 6. shaft, 7. excavated shaft, 8. direction of water flow.

Figure 9.

The VES profile going through the Eleven-Förtés doline group. Legend: 1. contour line, 2. profile, 3. wet area, 4. site of VES measurement, 5. rock outcrop and its mark, 6. shaft, 7. excavated shaft, 8. direction of water flow.

Figure 10.

A-A’ profile of Eleven-Förtés doline group. Legend: 1. limestone, 2. clay (with loess and with limestone detritus), 3. loess (with sand or with limestone detritus), 4. limestone detritus (with clay), 5. loess (with clay and mud) or clay with limestone detritus, 6. clay, 7. number and place of the VES measurement, 8. geoelectric resistivity of beds (Ohmm), 9. depth of bottom of geoelectric beds (m), 10. geoelectric resistivity of bedrock (Ohmm), 11. approximate penetration of VES measurement, 12.boundary of the geoelectric beds.

Figure 10.

A-A’ profile of Eleven-Förtés doline group. Legend: 1. limestone, 2. clay (with loess and with limestone detritus), 3. loess (with sand or with limestone detritus), 4. limestone detritus (with clay), 5. loess (with clay and mud) or clay with limestone detritus, 6. clay, 7. number and place of the VES measurement, 8. geoelectric resistivity of beds (Ohmm), 9. depth of bottom of geoelectric beds (m), 10. geoelectric resistivity of bedrock (Ohmm), 11. approximate penetration of VES measurement, 12.boundary of the geoelectric beds.

Figure 11.

Geoelectric–geological profiles marked a. A–A’ and b. B–B’ of the plate-shaped doline marked Fs1 (Zsidó-rét, Bükk Mountains) [

51]. Legend: 1. limestone, 2. loess (clayey-muddy) or clay with limestone debris, 3. clay, 4. site and identification code of the VES measurement, 5. geoelectric resistivity of the series (Ohmm), 6. base depth of the geoelectric series (m), 7. geoelectric resistivity of the bedrock (Ohmm), 8. approximate penetration of the VES measurement, 9. geoelectric series boundary, 10. identification code of the rock outcrop, 11. bedrock depression, 12. partial doline 13. dividing wall between partial depressions.

Figure 11.

Geoelectric–geological profiles marked a. A–A’ and b. B–B’ of the plate-shaped doline marked Fs1 (Zsidó-rét, Bükk Mountains) [

51]. Legend: 1. limestone, 2. loess (clayey-muddy) or clay with limestone debris, 3. clay, 4. site and identification code of the VES measurement, 5. geoelectric resistivity of the series (Ohmm), 6. base depth of the geoelectric series (m), 7. geoelectric resistivity of the bedrock (Ohmm), 8. approximate penetration of the VES measurement, 9. geoelectric series boundary, 10. identification code of the rock outcrop, 11. bedrock depression, 12. partial doline 13. dividing wall between partial depressions.

Figure 12.

Drawdown dolines of valley floor position (uvala, Aggtelek Karst). Legend: 1. limestone, 2. limestone debris (clayey), 3. clay, 4. clay (with limestone debris, sandy), 5. site and code of VES measurement, 6. geolecetric resistivity of series (Ohmm), 7. base depth of geoelectric series, 8. geoelectric resistivity of bedrock, 9. approximate penetration of VES measurement, 10. geoelectric series boundary, 11. mark of karstic depression, 12. bedrock outcrop with identification code.

Figure 12.

Drawdown dolines of valley floor position (uvala, Aggtelek Karst). Legend: 1. limestone, 2. limestone debris (clayey), 3. clay, 4. clay (with limestone debris, sandy), 5. site and code of VES measurement, 6. geolecetric resistivity of series (Ohmm), 7. base depth of geoelectric series, 8. geoelectric resistivity of bedrock, 9. approximate penetration of VES measurement, 10. geoelectric series boundary, 11. mark of karstic depression, 12. bedrock outcrop with identification code.

Figure 13.

Katavotra of Cirknitz polje (Slovenia).

Figure 13.

Katavotra of Cirknitz polje (Slovenia).

Figure 14.

Drawdown dolines in areal development from the Bravsko-polje (Bosnia-Hercegovina) [

51].

Figure 14.

Drawdown dolines in areal development from the Bravsko-polje (Bosnia-Hercegovina) [

51].

Figure 15.

The position of the piezometric level and the saturation level relative to each other Legend: 1. piezometric level, 2. saturation level, a. the two surfaces are parallel with each other, b. the distance between the two surfaces increases towards the centre of the doline because the saturation level subsides faster since a larger quantity of water with better dissolution capacity arrives at the epikarst, c. the distance between the two surfaces decreases towards the centre of the doline because the piezometric surface subsides faster than the saturation level since water with better dissolution capacity but in less quantity arrives at the epikarst.

Figure 15.

The position of the piezometric level and the saturation level relative to each other Legend: 1. piezometric level, 2. saturation level, a. the two surfaces are parallel with each other, b. the distance between the two surfaces increases towards the centre of the doline because the saturation level subsides faster since a larger quantity of water with better dissolution capacity arrives at the epikarst, c. the distance between the two surfaces decreases towards the centre of the doline because the piezometric surface subsides faster than the saturation level since water with better dissolution capacity but in less quantity arrives at the epikarst.

Figure 16.

The relationship among dissolution intensity, the shape, and size of drawdown doline and the piezometric level. Legend: a. the saturation level subsides faster than the piezometric level, the subsidence of the latter enables the significant subsidence of the piezometric level later therefore, the doline deepens, b. the saturation level subsides more slowly, the wet part of the epikarst is thinning, the doline is deepening to a lesser degree, if it is widening, 1. piezometric level, 2. transportation of dissolved material and the denudation of doline floor, 3. saturation level, I. initial state, II. mature state.

Figure 16.

The relationship among dissolution intensity, the shape, and size of drawdown doline and the piezometric level. Legend: a. the saturation level subsides faster than the piezometric level, the subsidence of the latter enables the significant subsidence of the piezometric level later therefore, the doline deepens, b. the saturation level subsides more slowly, the wet part of the epikarst is thinning, the doline is deepening to a lesser degree, if it is widening, 1. piezometric level, 2. transportation of dissolved material and the denudation of doline floor, 3. saturation level, I. initial state, II. mature state.

Figure 17.

The presumed position of the karstwater and the piezometric level relative to each other in a polje and its effect on the distribution of surface features. Legend: 1. karstic rock, 2. cover, 3. high karstwater table, 4. low karstwater table, 5. piezometric level, 6a. drawdown doline development with higher intensity, 6b. drawdown doline development with less intensity, 6c. plateau drawdown dolines, 7. subsidence dolines, 8. subsidence dolines with katavotra, 9. polje part permanently filled with water.

Figure 17.

The presumed position of the karstwater and the piezometric level relative to each other in a polje and its effect on the distribution of surface features. Legend: 1. karstic rock, 2. cover, 3. high karstwater table, 4. low karstwater table, 5. piezometric level, 6a. drawdown doline development with higher intensity, 6b. drawdown doline development with less intensity, 6c. plateau drawdown dolines, 7. subsidence dolines, 8. subsidence dolines with katavotra, 9. polje part permanently filled with water.

Figure 18.

The presumed position of the karstwater table and the piezometric level relative to each other at the drawdown dolines of fengcong karst, and its effect on the doline hydrology. Legend: 1. limestone, 2. caprock, 3. high karstwater level, 4. low karstwater level, 5. piezometric level, 6. karst mountain, 7. drawdown doline, 8. drawdown doline with subsidence dolines on its floor, 9. large drawdown doline 10. smaller drawdown dolines on the floor of the large drawdown doline, 11. subsidence dolines with katavotra on the floor of the large drawdown doline.

Figure 18.

The presumed position of the karstwater table and the piezometric level relative to each other at the drawdown dolines of fengcong karst, and its effect on the doline hydrology. Legend: 1. limestone, 2. caprock, 3. high karstwater level, 4. low karstwater level, 5. piezometric level, 6. karst mountain, 7. drawdown doline, 8. drawdown doline with subsidence dolines on its floor, 9. large drawdown doline 10. smaller drawdown dolines on the floor of the large drawdown doline, 11. subsidence dolines with katavotra on the floor of the large drawdown doline.

Figure 19.

Different phases of the coalescence of grikes and the Bullita cave in Judbarra Karst [

66].

Figure 19.

Different phases of the coalescence of grikes and the Bullita cave in Judbarra Karst [

66].

Table 1.

Resistivity values in the bedrock below drawdown dolines.

Table 1.

Resistivity values in the bedrock below drawdown dolines.

| area |

number of profiles taken into consideration

(profile) |

number of VES measurements

(measurement) |

average penetration of measurement into the bedrock relative to the bedrock surface (m) |

average resistivity1 (Ohmm) |

site of profile |

| Apuseni Mountains, Padis Răchite (Romania) |

3 |

46 |

4.55-8.58 |

11385.44 |

closed area enclosed by mounds with buried recent depressions on the bedrock, with subsidence dolines at its surface |

| Apuseni Mountains, Padis Răchite (Romania) |

5 |

34 |

4.76-6.96 |

10335.83 |

closed area enclosed by mounds, plain bedrock with subsidence dolines at its surface |

| sum and average at Răchite |

8 |

80 |

- |

10860.63 |

|

| Hideg Valley Aggtelek Karst, |

1 |

6 |

4.4-5.4 |

5220 |

solution dolines (soil-covered karst), recent |

| Czigány-földek, Mecsek Karst inner part of drawdown dolines |

4 |

25 |

5.16-6.56 |

4730.78 |

in drawdown doline subsidence dolines |

| Czigány-földek Mecsek Karst margin of drawdown dolines |

4 |

19 |

5.61-7.12 |

3818.45 |

in drawdown doline subsidence dolines |

| Czigány-földek sum and average |

4 |

44 |

- |

4274.61 |

|

| Hochschwab |

3 |

19 |

5.39-11.54 |

5258.98 |

large paleodepression, with covered karst, subsidence dolines |

| Totes Gebirge |

2 |

13 |

0.5-5 |

4176.4 |

paleodoline, with covered karst, subsidence dolines |

| Zsidó-Rét, Bükk Mountains |

2 |

6 |

4.65-5.81 |

10000 |

floor of plate-shaped doline |

| sum and average |

20 |

168 |

- |

6274.43 |

drawdown dolines (recent and paleokarstic) |

Table 2.

Resistivity values in the bedrock when there are only subsidence dolines.

Table 2.

Resistivity values in the bedrock when there are only subsidence dolines.

| area |

number of profiles taken into consideration

(profile) |

number of VES measurements

(measurement) |

average penetration of measurement into the bedrock relative to the bedrock surface (m) |

average resistivity1 (Ohmm) |

site of profile |

| Bakony Mountains, eastern part of Tés Plateau |

14 |

104 |

3-10 |

315 |

mostly on valley floor |

| Bakony Mountains, Eleven-Förtés |

10 |

68 |

5-7 |

611 |

inactive depression, with subsidence dolines in its area |

| Bakony Mountains, northern part of Mester-Hajag |

18 |

137 |

3-8 |

1273 |

area enclosed by mounds with subsidence dolines |

| sum and average |

42 |

309 |

- |

733 |

|

| Cigány-földek Mecsek karst outside solution dolines |

2 |

11 |

4.7-6.2 |

3785.50 |

subsidence dolines |

| area next to Răchite |

2 |

8 |

2.49-6.37 |

8443.33 |

valley-floor covered karst with subsidence dolines |

| Dachstein2

|

1 |

7 |

10-15 |

868.56 (453.86) |

paleodoline |

| sum and average |

47 |

328 |

- |

2885.57 |

- |

Table 3.

Bedrock resistivity data at bearing profiles at the subsidence dolines of the Bakony Region.

Table 3.

Bedrock resistivity data at bearing profiles at the subsidence dolines of the Bakony Region.

| mark of doline |

area |

resistivity [Ohmm] |

profile length (m) |

measurement number |

| below the doline |

average along profile |

largest difference |

| I-16 |

Tés 3 |

- |

346.4 |

92.00 |

100 |

5 |

| I-23 |

Tés 2 |

- |

350.00 |

0.00 |

30 |

2 |

| I-24 |

Tés 2 |

- |

275.00 |

120.00 |

200 |

4 |

| I-32 |

Tés 1 |

- |

252.62 |

170.00 |

200 |

8 |

| I-33 |

Tés 1 |

- |

301.28 |

186.00 |

260 |

7 |

| H-1 |

Homód Valley |

- |

307.00 |

390.00 |

144 |

8 |

| E-6 |

Eleven-Förtés |

- |

758.57 |

660 |

105 |

7 |

| I-25 |

Tés 2 |

230 |

306.67 |

90.00 |

10.8 |

5 |

| I-27 |

Tés 2 |

360 |

400.67 |

178.00 |

60 |

3 |

| H-2 |

Homód Valley |

200 |

252.5 |

140 |

126 |

5 |

| H-6 |

Homód Valley |

170 |

278.75 |

180 |

300 |

8 |

| E-1 |

Eleven-Förtés |

360 |

688 |

650 |

180 |

10 |

| E-2 |

Eleven-Förtés |

650 |

840 |

690 |

87 |

6 |

| E-5 |

Eleven-Förtés |

560 |

645 |

10 |

26 |

2 |

| I-17 |

Tés 2 |

310 |

251.63 |

80 |

75 |

8 |

| I-18 |

Tés 3 |

370 |

248.2 |

83 |

60 |

5 |

| I-26 |

Tés 2 |

340 |

275.00 |

200 |

12 |

7 |

| I-311

|

Tés 1 |

430 |

272.28 |

125 |

213.33 |

7 |

| H-8 |

Homód Valley |

390 |

303.33 |

220 |

300 |

9 |

| E-3 |

Eleven-Förtés |

670 |

550 |

780 |

118.33 |

5 |

| MH18 |

Mester-Hajag |

1500 |

1700 |

1000 |

67.5 |

5 |

| MH22 |

Mester-Hajag |

1600 |

1660 |

900 |

52.5 |

5 |

| MB-50 |

Mester-Hajag |

335,0 |

493,89 |

160 |

100.67 |

9 |

| F-21

|

Fehérkő Valley |

1390 |

1420 |

1330 |

118.00 |

7 |

| MH10 |

Mester-Hajag |

1800 |

1271.67 |

1000 |

80.00 |

6 |

| MH411

|

Mester-Hajag |

2000 |

1862.5 |

1000 |

92.5 |

8 |

| MH52 |

Mester-Hajag |

1400 |

1262.5 |

900 |

80.00 |

8 |

| MB411

|

Mester-Hajag |

510 |

505.6 |

156 |

196.67 |

10 |

| F1 |

Fehérkő Valley |

2500 |

1987.14 |

2720 |

65.78 |

7 |

| E-82

|

Eleven-Förtés |

1100 |

646 |

740 |

72.5 |

5 |

Table 4.

Average resistivity values of the profiles bearing the dolines by doline groups.

Table 4.

Average resistivity values of the profiles bearing the dolines by doline groups.

mark of doline

mark of group

|

area |

resistivity [Ohmm] |

shaft (total)

[shaft] |

doline case number

[doline] |

potential water supply into the karst |

| average resistivity of the bedrock at the dolines of the doline group |

average resistivity of profile sections that bear the dolines of doline groups |

largest resistivity difference of doline groups |

| E |

Tés, Homód Valley, Eleven-Förtés |

- |

370.13 |

229.71 |

7 |

n=7 |

a lot of |

| B |

Tés, Homód Valley, Eleven-Förtés |

367.14 |

487.37 |

276.86 |

1 |

n=7 |

a lot of |

| A |

Tés, Homód Valley, Eleven-Förtés |

418.33 |

323.41 |

248.0 |

1++ |

n=6 |

little |

| D |

Mester-Hajag, Fehérkő valley |

1206.25 |

1318.47 |

847.5 |

0 |

n=4 |

little |

| C |

Mester-Hajag, Fehérkő Valley |

1551.67 |

1255.90 |

1086.2 |

0 |

n=6 |

little |

Table 5.

The position of karstwater table relative to the surface in some tropical karren of Bemaraha type.

Table 5.

The position of karstwater table relative to the surface in some tropical karren of Bemaraha type.

| Karst area |

place |

elevation difference between karst surface and karstwater table |

source |

relative to |

features proving coalescence by dissolution |

source |

distance from sea (km) |

| Bemaraha Great Tsingy |

Madagascar |

50-90 |

[25] |

sea level |

interrupted by a cave going through a grike |

[25] |

30 |

| Bemaraha Little Tsingy |

Madagascar |

0-25 |

[25] |

River Manambolo |

notch, arch |

[25] |

MR |

| Broken River |

Australia |

38-43 |

[57] |

base level of erosion |

A |

[20] |

180 |

| Chillagoe |

Australia |

90-14 |

[57] |

spring cave |

A, B |

[20] |

100 |

| near Coles Creek (Barkly Karst) |

Australia |

16-22 |

[57] |

spring cave |

A, B |

[20] |

180 |

| Fanning River |

Australia |

75-79 |

[57] |

spring cave |

A |

[20] |

80 |

| Judbarra Karst |

Australia |

40-60 |

[21] |

East Baines River |

A, B |

[20,21] |

EBR |

| Mount Etna |

Australia |

15-23 |

[57] |

spring cave |

A |

[20] |

37 |

| West Kimberly region |

Australia |

78-65 |

[57] |

spring cave |

B (?) |

[20] |

260 |

| Tanga Karst |

Tanzania |

32-41 |

[47] |

se level |

A, B |

[47] |

0 |

| west from Coles Creek |

Australia |

16-22 |

[56] |

to spring cave |

A, B |

[20] |

320 |

| Bau Region |

Borneo (Sarawak) |

23-35 |

[56] |

spring cave |

A |

[57] |

JR |

Table 6.

Distribution of precipitation data on the studied tropical karren.

Table 6.

Distribution of precipitation data on the studied tropical karren.

| karst area |

site of precipitation data |

annual precipitation (mm) |

the wettest month |

percentage (%) of the wettest month relative to the annual |

source |

| Judbarra Karst |

Timber Creek |

926 |

207 (January) |

22.3 |

[21] |

| Bemaraha Tsingy (Great Tsingy, Little Tsingy) |

Morondava |

780 |

257.16 (January) |

32.96 |

[59] |

| Kimberley Karst |

Fitzroy Crossing |

541 |

150 (January) |

27.73 |

[21] |

| Barkly Karst |

Cam Do Weal |

387 |

90 (January) |

23.25 |

[21] |

| Chillagoe |

Chillagoe |

856 |

220 (February) |

25.73 |

[21] |

| Barkly Karst |

Boulia |

242 |

50 (February) |

20.66 |

[21] |

| Mount Etna |

Rockhampton |

943 |

2190 (February) |

20.02 |

[21] |

| Tanga Karst |

Tanzania |

2874 |

418 monthly (December, January, February) |

15.24 |

[58] |

| Broken River |

Townsville |

1096 |

338 (February) |

30.83 |

[58] |

| Fanning River |

Townsville |

1096 |

338 (February) |

30.83 |

[58] |