1. Introduction

In Bangladesh, the magnitude of anemia among children younger than five years is high, with a range that varies from 33% to 51%, according to two nationally representative surveys [

1,

2]. Iron deficiency was thought to be the primary cause of anemia in the Bangladesh population and thus, a national policy for its prevention recommended iron supplementation, i.e., micronutrient powder (MNP) containing iron, for children aged 6-23 months [

3,

4]. Consequently, the MNP supplementation (containing 12.5 mg of iron) programs have been operational for decades to prevent anemia in infants and children from 6 to 59 months old [

5]. Nevertheless, the coverage of the MNP program is suboptimum [

5], and compliance is poor because of iron-related side effects such as diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting [

6].

However, contrary to popular perception, the National Micronutrient Survey 2011–2012 reported that the prevalence of iron deficiency (ID) in children under-five was 10.7%, and iron deficiency anemia (IDA) was 7.2% [

7]. Recent studies attributed the low prevalence of ID and IDA in the Bangladesh population to drinking iron-containing groundwater from tube wells [

2, 8]. Of note, groundwater (extracted from hand-pumped tube-wells) is the principal source of drinking water for the large majority (97%) of the rural population in Bangladesh [

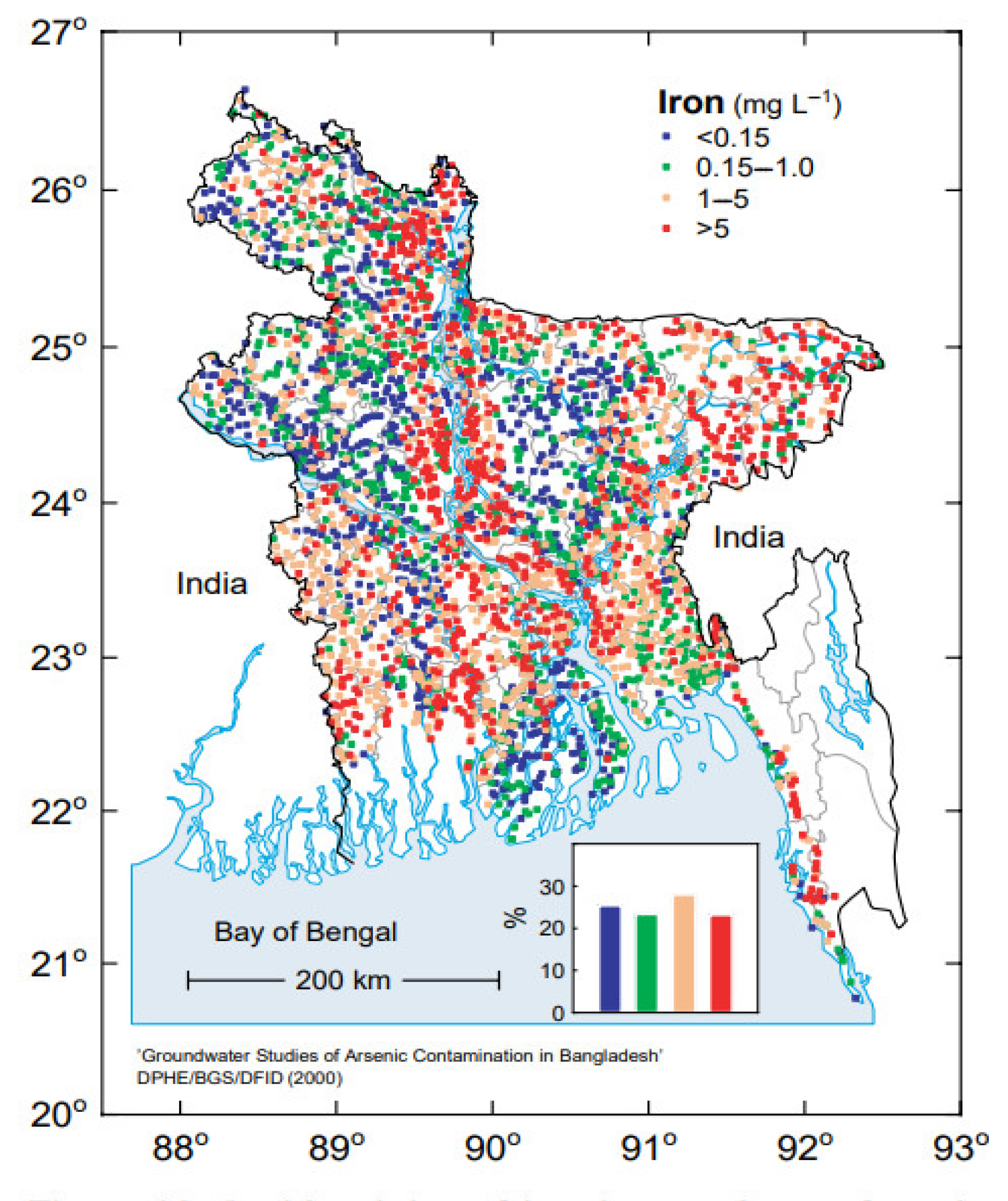

9]. Hydrochemistry of Bangladesh groundwater reveals that it contains varying concentrations of dissolved iron, with a predominantly high concentration in many parts of Bangladesh, but a largely low concentration in other parts of the country [2, 9]. Furthermore, a prominent feature of groundwater is that the iron concentrations vary considerably between tube-wells located near each other. Hence, even in predominantly high iron groundwater areas, some wells contain a low concentration of iron in the water.

Figure 1.

[M1] Variation of iron concentration in groundwater in different parts of Bangladesh [

9] with permission of the BGS and DPHE. 2001. Arsenic contamination of groundwater in Bangladesh. Kinniburgh, D G and Smedley, P L (Editors). British Geological Survey Technical Report WC/00/19. British Geological Survey: Keyworth.).

Figure 1.

[M1] Variation of iron concentration in groundwater in different parts of Bangladesh [

9] with permission of the BGS and DPHE. 2001. Arsenic contamination of groundwater in Bangladesh. Kinniburgh, D G and Smedley, P L (Editors). British Geological Survey Technical Report WC/00/19. British Geological Survey: Keyworth.).

Acknowledging the presence of a high concentration of iron in groundwater, the national anemia consultation of Bangladesh [

3] recommended examining the efficacy and side effects of MNP supplementation with a low dose of iron for children residing in areas with predominantly high groundwater iron. Consequently, a recent trial conducted among Bangladeshi children aged 2-5 years demonstrated that low-iron MNP (containing 5 mg iron) was equally efficacious in preventing anemia compared to the standard MNP containing 12.5 mg of iron [

10]. In addition, low-iron MNP was associated with significantly fewer incidences of key side effects, such as diarrhea, loose stools, nausea, and fever compared to the standard MNP [

10]. The study recommended low-iron MNP for the prevention of anemia in children under five years residing in high iron groundwater areas.

Given the geologically variable iron-content in groundwater in Bangladesh, it would be difficult to introduce low-iron MNP (containing 5 mg iron) for children drinking high-iron groundwater and standard MNP (containing 12.5 mg iron) for children drinking low-iron groundwater. Administratively it would be much more feasible and cost-effective to have a single composition (e.g., low-iron MNP) for the whole population. Therefore, the present cross-sectional study examines the potential of the low-iron MNP in preventing childhood anemia in predominantly low-iron groundwater areas or in children whose potable supply is groundwater with a low concentration of iron (0-<2 mg/L). The specific objectives are—

The assessment of the combined intake of iron from the key sources (diet, drinking groundwater, and low-iron MNP).

To compare the combined intake with the dietary reference intakes; and

The measurement of concentration of hemoglobin in the children.

The intake comparison to the reference intakes contributed to understanding the extent of iron intake in a low groundwater setting, and thus an assessment of the possible protection from anemia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants and Selection Process

The study participants are children aged 2-5 years residing in Belkuchi- a rural sub-district of north-west Bangladesh. The children were selected from a household if the groundwater iron concentration of the tube wells they drink from was low, i.e. 0-<2 mg/L. Low concentration (<2 mg/L) is defined as per the cut-off recommended by the joint technical committee of the Food and Agricultural Organization and World Health Organization FAO/WHO [

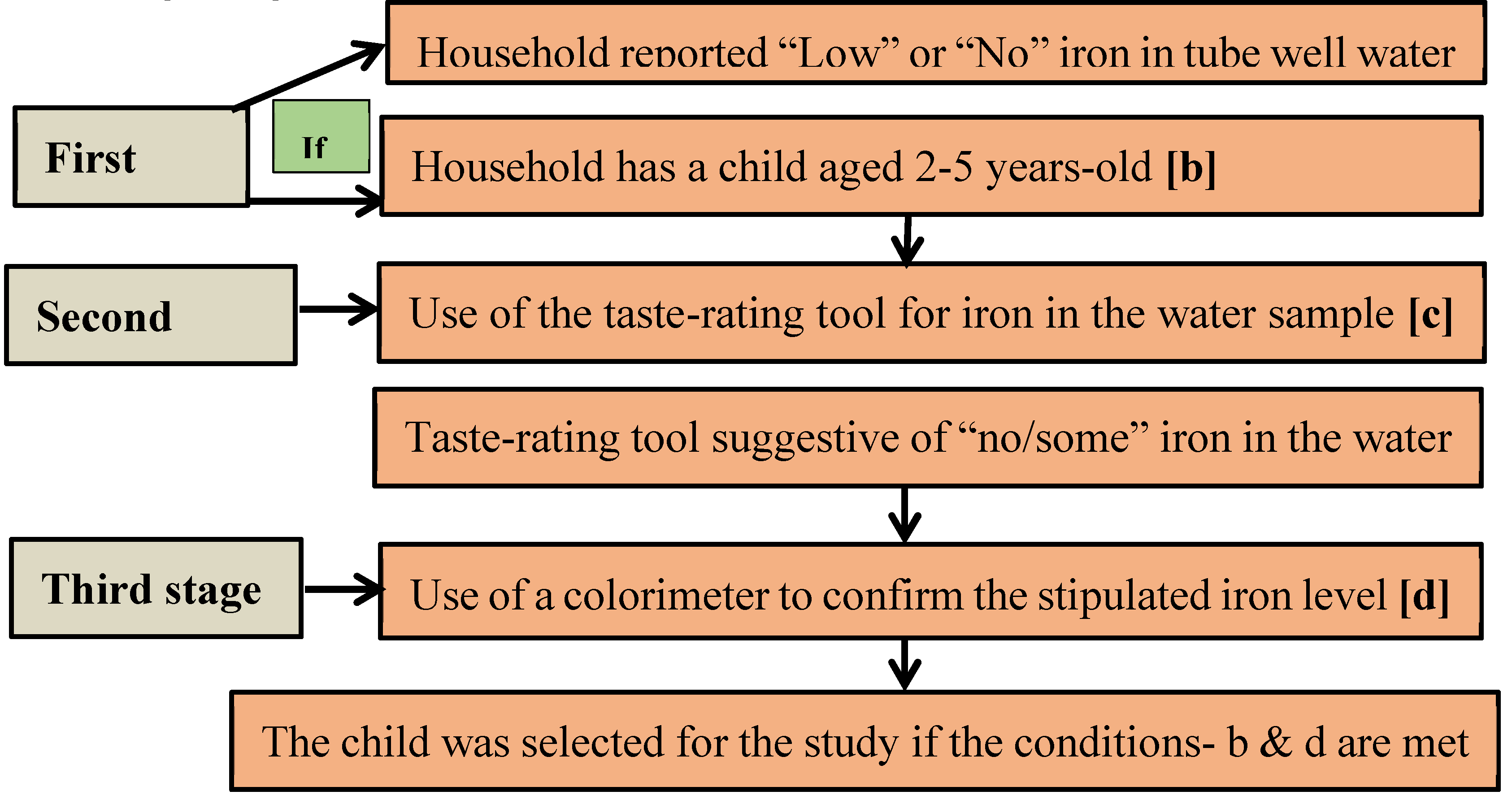

11]. The sampling was done over three stages (

Figure 2).

In the

first stage, an inquiry was made with local residents to know about-- 1) households with a drinking water source (tube well) containing “low” or “no” iron; and 2) if the designated household had a child who met the age criteria. In the

second stage, the initial verification of the iron content of groundwater was done in the designated households by using a novel sensorial tool—taste-rating of a groundwater sample for the level of iron [

12]. The tool with the standardized operational guidelines is used for providing “taste-rating” of the groundwater samples for an semi-quantitative assessment of iron content into three groups—“no iron”, “some iron” and “heavy iron”. The details of the method are provided in Rahman et al [

12]. In case the taste-rating suggested a “no” or “some” level of groundwater iron, in the

final stage, a colorimetric device was used to confirm stipulated concentration iron in the groundwater (0-<2 mg/L). A child was selected for the study if both conditions (age, level of drinking water iron) were met. Data were collected from 1 August to 16 August in 2018. Authors had no access to information that could identify individual participants during or after data collection.

2.2. Sample Size

There is a paucity of data on the intake of iron from drinking groundwater in children. The available study that estimated the intake of iron from groundwater reported a standard deviation (SD) of 6.5 [

10]. That study was conducted considering tube-wells with a high concentration of groundwater iron, and had a mean concentration of iron ~8 mg/L (max. 43.3 mg/L). So, the wide range of the values of iron intake yielded a relatively large SD. The present study considered children who drank from groundwater with a concentration of iron 0-<2 mg/L. So, assuming a reasonably lower SD for the mean intake of iron from water in this population, a SD of 3.25, which is equivalent to 50% of the SD of the referred study, was considered reasonable in the present study. Allowing for a margin of error of 0.7 mg, with a variance (SD

2) of 10.2 and a 95% confidence level, the required sample size was 80, as per online sample size estimation software [

13]. However, we measured the concentration of iron in groundwater of 122 tube-wells. Therefore, 122 children were interviewed and intake of iron from groundwater was assessed in the same number of children.

To estimate the mean hemoglobin, considering the variance (SD

2) of 0.608 (Rahman et al., 2019), and an error margin of 0.15 mg/dl at a 95% confidence level, the required sample size was 104 [

13]. The actual number of the children who were measured for hemoglobin was 105.

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Assessment of Dietary Iron Intake

The mother of the recruited child was asked about her child’s intake of food over the 24-hours preceding the interview. The intake was captured by a 24-hour recall over the six time prompts— breakfast, mid-morning, lunch, afternoon, dinner and bedtime. The amount of the reported food intake was assessed by using food albums and utensils—plates, bowls, spoons, and packets/brands of the food items (i.e., processed foods). An updated food composition table on Bangladeshi foods [

14] was used to calculate the intake of iron from the food items.

2.3.2. Assessment of iron Intake from Groundwater (Drinking Water)

The concentration of iron in the drinking water sample was measured by a colorimetric test kit device (Hanna 3831, Hanna Instruments, USA) by using the manufacturer’s provided manual. To calculate the intake of iron from drinking groundwater, the total amount of water intake was first assessed over the 24-hours preceding the interview using six time prompts following the methods described by Merrill et al [

8]. Intake of iron was calculated by multiplying the concentration of iron in the groundwater sample and the volume of intake of water over the 24-hours preceding the interview [

8, 10].

2.3.3. Intake of Iron from MNP Supplements

A hypothetical intake of the low-iron MNP was calculated. Since the compliance of MNP supplement consumption is generally suboptimum in the programmatic context of Bangladesh, the study considered the hypothetical intake of MNP representing two different compliance levels. Compliance of 85% and 50% was considered satisfactory [

15] and sub-optimum consumption, respectively. The intake of iron from the low-iron MNP was calculated by multiplying the dose (5 mg/day) by 0.85 (at 85% intake compliance) and 0.50 (at 50% intake compliance).

2.3.4. Assessing the Total Iron Intake from Different Sources

The children’s intake of iron from drinking groundwater (i.e., tube-wells) and their dietary intake of iron were estimated. Further, intake of iron from the low-iron MNPs was assessed hypothetically. The combined intake of iron from the sources was calculated and compared with the dietary reference intakes; i.e., Estimated Average Requirements (EAR) and the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for the stipulated age group of the children. The amount of bio-available iron was calculated and compared with the reference values.

2.3.5. Reference Standard for Comparison

The EAR and the RDA were used as references to assess the extent of iron intake from all sources. An EAR is the average daily dietary intake level; sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of half (50%) of the healthy individuals in a group. An RDA is the average daily dietary intake level; sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97-98%) of the healthy individuals in a group [

16]. For children aged 2-3 years and 4-5 years, the RDAs of iron were 7 mg/day and 10 mg/day [

16], while the EARs were 3 mg/day and 4.1 mg/day respectively [

17]. The intake of bio-available iron was compared to the median and the 95

th percentile of the joint FAO and WHO reference [

18]. The medians were 0.46 mg/day and 0.50 mg/day in the 2-3 year-old and 4-5 year-old groups respectively. The 95

th percentiles were 0.58 mg/day and 0.63 mg/day in the respective age groups.

2.3.6. Assessing the Total Intake of Bioavailable Iron

The children’s age varied between 2 to 5 years and therefore they had been exposed to iron from drinking water for different length of time. Additionally, the groundwater iron concentration of the tube-wells could have been any value of the 0-2 mg/L range. Hence, taking these factors into consideration, it was assumed that some children might have had a depleted status of body iron, particularly the children who drank from the wells with zero or close to zero concentration of iron. Conversely, some children, principally those who drank from the tube-wells with water iron concentration in the higher side of the 0-2 mg/L range, might have had replete body-iron reserves. Therefore, to calculate the bioavailable iron from groundwater and present both scenarios, we used 40% efficiency of absorption of iron from the water considering iron-deplete participants and 10% considering iron-replete participants as reported by Worwood et al [

19]. Average absorption efficiency (23%) [

19] was used in determining the amount of the bioavailable iron from the groundwater during the sub-group assessment (i.e. subgroups 0-<0.8 mg/L & >=8-2.0 mg/L). This is because the range of the iron concentration at the sub-group level would not have had a similar scale of water iron concentration to the overall (all samples) range (0-2 mg/L). Assuming 40% absorption in the iron-depleted children (consuming from wells at a near-zero concentration of iron) and 10% absorption in the iron-replete children (consuming from wells at near 2 mg/L iron concentration) is not applicable. Hence, the average absorption potential of 23% was considered at the sub-group level [

19].

Regarding absorption of iron from the MNP that contains ferrous fumarate as the iron-complex and ascorbic acid as the absorption enhancer, for the participants who were iron-replete, an absorption rate of 4.65% was considered [

20]. For the participants with iron-depleted status, the absorption rate of 4.48% was considered [

20]. The combined intake of bioavailable iron from all-sources (dietary +groundwater +MNPs) was calculated considering the hypothetical usage of the low-iron MNP at the satisfactory (85%) [

15] and suboptimum (50%) level of compliance. No children were consuming any iron supplements (including MNP) at the time of the study and in the preceding 6 months, and therefore such supplements were not considered for calculating the combined iron intakes. Regarding bioavailability of dietary iron, taking into consideration the predominantly cereal-based traditional diet, a 5% absorption was considered [

21].

Since the focus of the study was the assessment of the potential of the low-iron MNP on hemoglobin status in a low-iron groundwater setting, an appraisal of the intake of iron from the key sources in conjunction with the intake of low-iron MNP is provided in the results section. However, a similar assessment of the standard MNP, the existing MNP formulation in the country, is presented as supplementary data (Supplementary

Table 1, 2).

2.3.7. Measurement of Hemoglobin

The hemoglobin concentration of the children was measured on venous blood samples by a photometer (Hemocue 301, Hemocue AB, Angleholm Sweden). The blood was drawn from the median cubital vein with the participants seated on their mothers’ laps. Following proper asepsis of the puncture site with an alcohol pad, 0.5 ml of blood was drawn using a 3 ml disposable syringe. The blood sample was gently placed on a cover slip and sucked into a microcuvette of the photometer device. The measurement was performed observing the manufacturer’s supplied manual.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

General characteristics of the children were estimated as mean ±SD and median (interquartile range) for the quantitative variables, and proportion (%) for the categorical variables. The histogram visualization appeared nearly consistent with normality; however, the Shapiro-Wilk U coefficient, which is a stricter metric of normal distribution, was statistically significant. Such as children’s age (z=2.27, p=0.01, results not shown), intake of groundwater iron (z=4.65, p=0.000, results not shown), intake of dietary iron (z=5.35, p=0.000, results not shown). Hence the aggregated intake of iron from all foods consumed over the preceding 24 hours was presented as mean ±SD and median with interquartile ranges (IQRs). Intake of iron from the standard (12.5 mg iron) and low-iron (5 mg iron) MNPs was hypothetically deducted as the function of 85% (satisfactory compliance) [

15] and 50% consumption (suboptimum compliance). Children were sub-grouped by the median concentration (0.8 mg//L) of iron in their drinking water. Mann-Whitney test was performed for comparison of intakes of iron between the groups with p-values < 0.05 considered significant. However, since the hemoglobin concentrations were normally distributed (non-significant Shapiro-Wilk U coefficient; results not shown), a student’s t-test was performed to compare the groups. The prevalence of anemia between the groups was compared by a chi-square test. Linear regression was performed on the log-transformed data to assess the association of hemoglobin concentration vs. a) the groundwater iron concentration, b) intake of groundwater iron, and c) dietary iron. Additionally, linear models were depicted by graphs illustrating 95% confidence intervals around the fitted lines. Furthermore, linear regression was performed on the log-transformed data to assess the association of the intake of groundwater iron and dietary iron with children’s hemoglobin concentration after adjusting for the groundwater iron concentration. Geometric coefficients were presented along with SE on the back-transformed data. All analyses were done by the statistical software STATA 17 (STATA Inc. College Station, Texas, USA).

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was nested in a community-based trial examining the efficacy of a novel micronutrient powder formulation in children residing in areas with a high level of iron in groundwater. The trial received approval from the Research Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Biological Science, Dhaka University, Bangladesh (Ref# 46 /Biol. Scs. /2017-2018) and Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee, Australia (Ref# 2017/467). Written informed consent was obtained from the participant’s (2-5 years old) guardian before the interview and blood collection. Data are kept in a secure place with the lead investigators. The participants will remain anonymous during the presentation of the aggregated results.

3. Results

Table 1 depicts the general characteristics of the children in the study. The mean ±SD age of the children was 43±10.6 months. The proportion of female children was 44.3%. The common occupations of the household head were: unskilled labor (32.8%), skilled labor (14.8%), business (12.3%) and farmer (11.5%). The mean ± SD duration of institutional education of the mothers was 6.3±4.6 years. The mean ±SD weekly expense for purchasing basic food items was BDT. 1801.3 ±676.1 [USD 21.3±8.0]. The mean ± SD amount of cultivable land possessed by households was 23.6±43.5 decimals. The mean ± SD intake of water by the children over the preceding 24 hours was 885.5 ± 428.4 ml.

Table 1.

Selected Child and Household Characteristics.

Table 1.

Selected Child and Household Characteristics.

| Child and Household Characteristics |

Estimates (N=122) |

| Age (months) |

43.0±10.6 |

| Sex (Female), n (%) |

54(44.3) |

| Occupation of household head |

|

| Business, n (%) |

15(12.3) |

| Skilled labor, n (%) |

18(14.8) |

| Unskilled labor, n (%) |

40(32.8) |

| Farmer, n (%) |

14(11.5) |

| Mother’s education (years) |

6.3±4.6 |

| Weekly expenses on principal food items* (BDT.)** |

1801.3±676.1 |

| Amount of cultivable land (decimal unit) |

23.6±43.5 |

| Intake of water (ml) |

885.5±428.4 |

‡Combined intake was calculated by summation of intake of dietary iron and groundwater iron

Table 2 shows the mean ±SD intake of dietary iron, groundwater iron, and the combined intake from these sources by age groups of the children. Intake of dietary iron, groundwater iron and the combined dietary and groundwater iron in children aged 2-3 years was 2.62±1.84 mg/day, 0.64±0.51 mg/day and 3.3±2.0 mg/day, respectively. The respective intakes in children aged 4-5 years were 3.51±2.34 mg/day, 0.85±0.73 mg/day and 4.4±2.5 mg/day. The combined intakes of dietary iron and water iron comprised 47.1% and 44% of the RDA in the respective age groups. The aggregated intakes exceeded the EAR for both the subgroups at 110% and 107.3% respectively.

Table 2.

Intake of dietary iron, groundwater iron, and combined intake in children by the age group.

Table 2.

Intake of dietary iron, groundwater iron, and combined intake in children by the age group.

| Age sub-group |

RDA

(mg/d) |

EAR

(mg/d) |

Intake of iron (dietary)*

(mg/d) |

Intake of iron (water)† (mg/d) |

Intake of iron (dietary +water) ‡ (mg/d) |

Combined intake % of reference intakes |

| |

|

Mean ±SD

(n) |

Median

(IQR)

(n) |

Mean

±SD

(n) |

Median

(IQR)

(n) |

Mean ±SD

(n) |

Median

(IQR)

(n) |

RDA (%) |

EAR (%) |

| 2-3 year-old |

7 |

3 |

2.62±1.84

(31) |

2.14

(1.48-3.22)

(31) |

0.64±0.51

(31) |

0.55

(0.26-1)

(31) |

3.3±2.0

(31) |

3.10

(1.84-4.26)

(31) |

47.1 |

110 |

| 4-5 year-old |

10 |

4.1 |

3.51±2.34

(91) |

2.87

(1.77-4.6)

(91) |

0.85±0.73

(91) |

0.71

(0.31-1.26)

(91) |

4.4±2.5

(91) |

3.67

(2.37-5.92)

(91) |

44.0 |

107.3 |

Table 3 depicts the intakes of actual and bioavailable iron from dietary and groundwater sources and the mean concentration of hemoglobin and the prevalence of anemia in children, stratified by the median concentration of iron in groundwater (0.8 mg/L). The children’s mean (SE) intake of iron from drinking groundwater was 1.11±0.07 mg/day and 0.24±0.04 mg/day in the sub-groups, defined as groundwater iron concentration (≥0.8-<2.0) mg/L and (0.0-<0.8) mg/L respectively; (p<0.001). The mean ±SE intake of the dietary iron between the sub-groups did not differ statistically; 3.32±0.38 mg/day vs. 3.26±0.23 mg/day, p=0.79. The combined mean ±SE intake of bioavailable iron from dietary and groundwater sources was 0.42±0.023 mg/day and 0.22±0.019 mg/day in the sub-groups (≥0.8-<2.0 mg/L) and (0.0-<0.8 mg/L) respectively; p<0.001. The mean± SE concentration of hemoglobin in children did not differ statistically; 11.91±0.91 mg/dl (0.0-<0.8 mg/L subgroup) vs. 12.17±0.94 mg/dl (≥0.8-<2.0 mg/L subgroup), p=0.30. The prevalence of anemia was 6.25% and 12.2% in the (≥0.8-<2.0 mg/L) and (0.0-<0.8 mg/L) subgroups respectively (p=0.29).

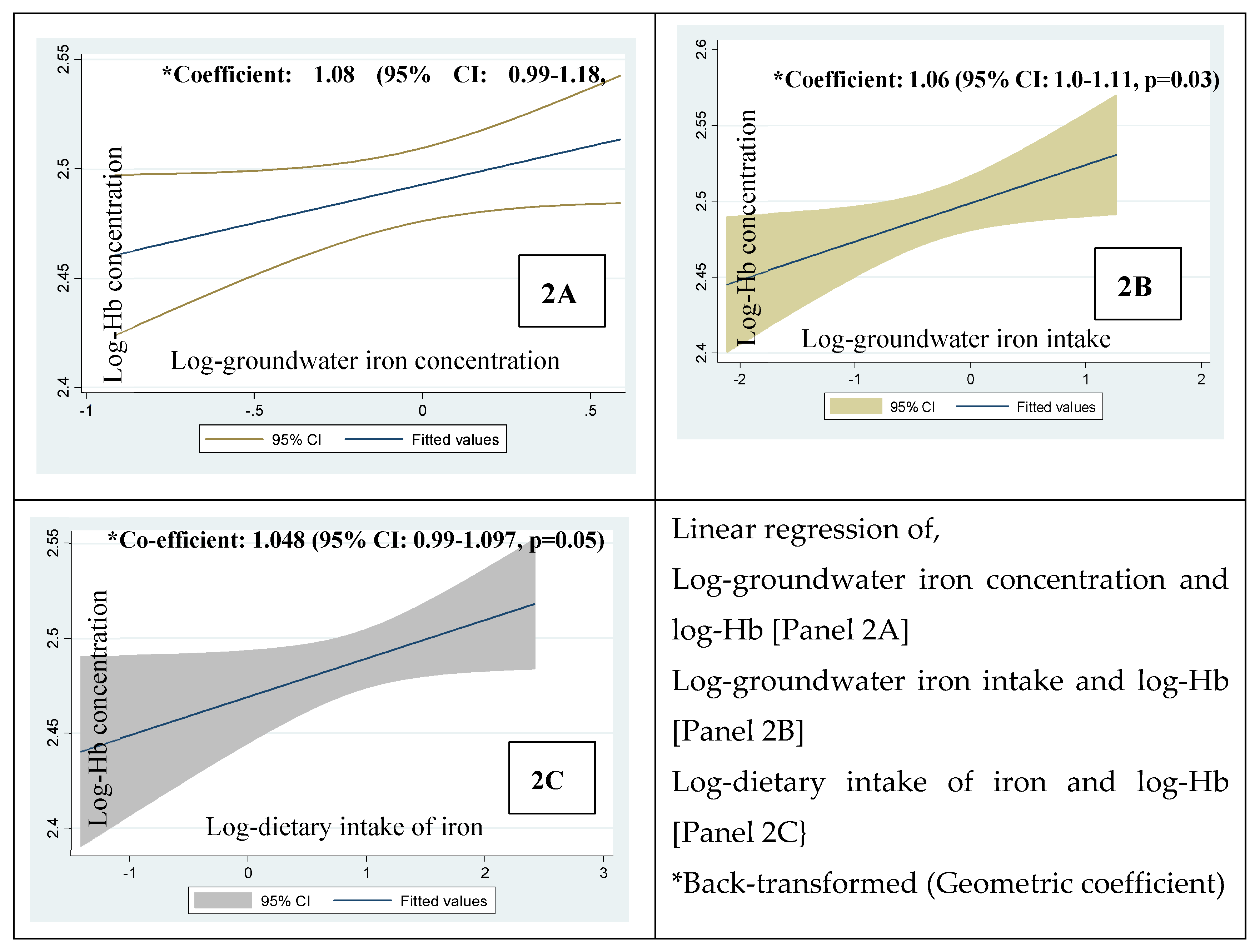

Figure 3 shows the linear regression of the log-hemoglobin concentrations in children vs. 2A) log-groundwater iron concentration, 2B) log-intake of groundwater iron and 2C) log-dietary intake of iron. The geometric mean of iron concentration of groundwater and the concentration of the children’s hemoglobin was positively associated at 6% level of statistical significance; coefficient:1.08; p=0.06, 2A). The geometric mean of the intake of groundwater iron and dietary iron vs. the hemoglobin concentrations were statistically significant (coefficient: 1.06, p=0.03, 2B) and just significant (coefficient: 1.048, p=0.05, 2C) respectively.

The linear regression (

Table 4) showed that the log-intake of dietary iron is positively associated with log-hemoglobin concentration after adjusting for the log-groundwater iron concentration (Beta=0.25; p=0.023). After adjusting for the log-groundwater iron concentration, the log-intake of the water iron was associated with log-hemoglobin concentration at a 6% level of statistical significance (Beta 0.19, p=0.06).

Table 5 presents the total intake of iron from all sources—dietary, groundwater and the low-iron MNP by children using the different levels of compliance - satisfactory (85%) and suboptimum (50%). The all-sources mean ±SD intakes of iron in children aged 2-3 years were 7.5±2.0 mg/day and 5.8±2.0 mg/day at the 85% and 50% compliance level of MNP intakes, respectively. In the 4-5 year-old group, the respective intakes were 8.6±2.5 mg/day and 6.9±2.5 mg/day. At the satisfactory compliance of MNP (85%), all sources intakes were 250% and 210% of the average reference intake (EAR) in the 2–3 year-old and 4-5 year-old groups, respectively. At the suboptimum compliance of MNP (50%), all sources’ aggregated intakes were 193% and 169% of the EARs, respectively.

In the case of the intake of low-iron MNP at suboptimum compliance, the intake of iron from all sources was 83% and 69% of the RDAs in the respective age groups. In the case of satisfactory compliance, the RDAs exceeded at 107% and 86% respectively (

Table 5).

Table 6 presents the mean ±SD intake of bioavailable iron from all sources (dietary + groundwater + low-iron MNP) by the body iron status of the children, differential absorption potential of groundwater iron and differential MNP compliance. In the case of 85% intake of low-iron MNP, mean ±SD and median (IQR) intake of bioavailable iron from the combined sources (diet, groundwater, low iron MNP) are either on par, higher or lower than the reference intakes of bioavailable iron [

17] depending on the status of body iron. In 2-3 year-old iron-depleted children, the mean ± SD and median (IQR) intakes were 0.58±0.24 mg/d and 0.49 (0.40-0.78) mg/d respectively. In the case of the iron-replete children, the mean ± SD and median (IQR) intakes of bioavailable iron were 0.39 ± 0.11 mg/d and 0.37(0.31-0.45) mg/d respectively which are lower than the reference requirements-- median and the 95

th percentile. At 50% intake of low-iron MNP, the intake of bioavailable iron in children generally was lower than the reference requirement irrespective of the iron status of the children, except the mean intake in the iron depleted children which was higher than the median of the reference.

In children aged 4-5 years, at 85% compliance of low-iron MNP, the intake of the combined sources of bioavailable iron was higher than the reference requirement except for the median intake relative to the 95th percentile of the requirement in children depleted of iron. In iron replete children the intake was lower than reference requirements, i.e. median and the 95th percentile.3.1 An account of the iron intake in relation to the intake of the standard MNP

In the case of the standard MNP, the estimated intake of iron from all sources exceeded the EAR considerably in both the age groups; 365.8-463.3% (at the satisfactory compliance, 85%) and 258.5-316.6% (at the suboptimum compliance, 50%; Supplementary

Table 1). The intake of bio available iron from all sources with the satisfactory MNP compliance exceeded both the median and the 95

th percentile of the reference irrespective of the iron status of the children. In the case of the suboptimum MNP compliance, the intake of bio-available iron from all-sources exceeded the median regardless of the iron status of the children, and exceeded the 95

th percentile in the iron- depleted children (Supplementary

Table 2).

4. Discussion

The present study examined the intake of iron in 2-5 year-old rural Bangladeshi children from all the key sources, including the drinking of groundwater with a low concentration of iron (0-<2 mg/L), diet, and the hypothetically-consumed low-iron MNP (or the standard MNP) at different compliance of consumption. Hemoglobin concentration of the children was measured to appraise the potential scope of low-iron MNP to prevent anemia in children who drink groundwater with a low concentration of iron.

Our results revealed that the combined intake of iron from diet and groundwater marginally (107-110%) exceeded the EAR in both age groups. However, when low-iron MNP was hypothetically added to that of the diet and groundwater, the intake relative to the EAR was further increased- (210-250%) for satisfactory compliance and (168-193%) for suboptimum compliance of MNP. The prevalence of anemia (in absence of the hypothetical MNP intervention) was low (8.6%).

Furthermore, the comparative intakes of groundwater iron, dietary iron and hemoglobin concentrations in children sub-grouped by the median groundwater Fe concentration (0-<0.8 mg/L vs. ≥0.8 <2 mg/L) were examined. Statistically there was no difference in the concentrations of hemoglobin between the groups (p=0.30). The statistical parity in hemoglobin concentrations between the groups was observed along with --a) the statistical parity in the amount of the dietary iron and b) about 4.5 times lower intake of groundwater iron in the group with groundwater iron concentration below the median (0-0.8 mg/L). This demonstrated that even a very modest amount of daily consumption of iron from drinking water was associated with a fair concentration of hemoglobin at the non-anemic level. This is difficult to explain. Nonetheless, the observation compliments our finding that the intake of the groundwater iron and hemoglobin concentration of the children was positively associated (coefficient 1.06, p=0.03). Further, when the linear associations of --- 1. intake of groundwater iron and 2. intake of dietary iron vs. the hemoglobin concentration were assessed after adjusting for the groundwater iron concentration, we found that the geometric coefficient for the intake of groundwater iron for a favorable influence on the hemoglobin concentration was 1.08 with a SE 1.04 (p-value 0.06, standardized Beta 0.19). The geometric coefficient for the intake of dietary iron for a favorable influence on the hemoglobin concentration was 1.06 with a SE 1.02 (p-value 0.023, standardized Beta 0.25).

The possible reason for the statistically significant p-value for the dietary iron predicting the hemoglobin concentration after adjusting for the groundwater iron concentration was perhaps the lower SE for the geometric coefficient. It suggests that the dietary intake of iron is relatively homogeneous across the study children and less variable than the intake of iron from groundwater. The intake of groundwater iron would be more variable over a wide range of iron concentrations (0-2 mg/L). Thus, the association of the intake of groundwater iron on hemoglobin concentration following the adjustment for groundwater iron concentration, despite with a larger effect size (geometric coefficient) was constrained by a higher SE with a slight loss of precision resulting in the p-value marginally outside 0.05. However, the judgement on the importance of a result needs to be based on the size of the effect seen and not the p-value only [22, 23]. The thorough appraisal of the association of the groundwater iron intake and hemoglobin concentration through the linear regression with and without the adjustment for groundwater iron concentration provides some explanation that even a low intake of groundwater iron was compatible with the maintenance of hemoglobin concentration at the non-anemic level.

Further, the amount of the combined bioavailable iron from dietary and drinking water sources (0.22 mg/day) in children consuming very low amount of iron from drinking water (iron concentration 0-<0.8 mg/L) was lower than the FAO/WHO recommended median of the daily requirement (0.46 mg/d) [

17]. Despite the low amount of bioavailable iron, the mean concentration of hemoglobin in the group was 11.93 mg/dl (median 12 mg/dl), which is well-above the cut-off for defining anemia (<11 mg/dl), and most of the children (87.8%) were non-anemic. This is hard to explain on the back of low absorption (5%) of dietary iron due to their predominantly cereal-based food intake. We assume that despite being in small amounts, a constant daily dose of highly bioavailable (23% assumed in the present study) iron from drinking water over the years might have replenished and developed the body’s iron reserve in the children to support hemoglobin synthesis.

We observed (results not shown) that the association of groundwater iron concentration and the concentration of hemoglobin is further strengthened when cases with zero value of iron concentration in the drinking water are omitted. The zero values of the groundwater iron concentration were excluded to measure the association of the non-zero values with hemoglobin concentration. We assume that the non-zero concentration of iron in the drinking groundwater is likely to have a greater effect on hemoglobin than the zero-iron concentrations taking into consideration that the dietary intake of iron remains roughly similar. The linear regression of non-zero values of groundwater iron concentration vs. hemoglobin concentration was analyzed in the lower group (iron concentration (0-<0.8 mg group), which revealed that the regression coefficient was 12 (p= 0.037, results not shown). A small sample size with n=21, the effect size is large and established the association.

We observed that the linear regression of the combined intake of iron from dietary and groundwater sources was positively associated with hemoglobin concentration with a statistical significance (results not shown). When, the low iron MNP was hypothetically added to the dietary and the water iron at either level of the compliance, the association maintained the same magnitude of the coefficient with the same level of statistical significance (results not shown). The reason is that the inclusion of the intake of the low iron MNP was hypothetical; as such a fixed mean amount of iron from MNP was added which did not influence the coefficient from a statistical point of view.

However, this does not preclude the prospect of the low iron MNP for preventing childhood anemia in the setting. The salient findings of the study were-- dietary iron and water iron combined exceeded the EARs marginally (107-110%). When the hypothetical iron from the low iron MNP was added, the EAR exceeded considerably (168-193%). Despite exceeding the EAR from the combined dietary and groundwater iron intake, about 9% of the children were anemic. Taking into consideration of the bio-availability of iron, the combined amount of bio-available iron just exceeded the median of the requirement if the low iron MNP is added (at a sub optimum compliance) to the dietary and groundwater iron. The usage of the standard MNP at either level of compliance (satisfactory or suboptimum) might result in an even higher amount of bioavailable iron with a potentially higher likelihood of side effects. Furthermore, the groundwater iron concentrations vary considerably and very low level or “zero iron” (e.g. 16.4% in the present samples) exist in groundwater of many areas of the country where dietary and water iron combined may not satisfactorily address anemia. Complementing this, the median intake of iron in children aged 2-3 years-old decreased by 45% (from 5.6 mg/day to 3.1 mg/day,

Table 5, 2) when the low iron MNP at the suboptimum compliance is omitted from the combined all sources iron (diet, groundwater and low iron MNP). Similarly, the median intake of iron in children aged 4-5 years-old decreased by 41% (from 6.2 mg/day to 3.67 mg/day,

Table 5, 2) when the low iron MNP at the suboptimum compliance is taken off from the all-sources iron. Thus, the observation further highlights the need for the low iron MNP for the children to maximize the protection from anemia in this setting, particularly to the anemic children exposed to a very low concentration of water iron (i.e. closer to the zero iron values and/or very low intake of groundwater iron). Further study is required for the confirmation.

The strength of this study is that we used venous blood which has a higher accuracy for measurement of hemoglobin [24, 25, 26]; hence the hemoglobin measured in the study better reflects the actual status. The study has some limitations. First, we did not consider the real-life consumption of MNP to account for its actual contribution to the intake of iron; instead, we modeled to show hypothetical intake levels of MNPs for determination of the combined intakes of iron from the multiple sources. Second, consumed iron from multiple channels might have inter-source interactions in the gastro-intestinal tract which might influence the absorption in the intestines. Studying such interactions was beyond the scope of the study. Third, an iron status biomarker, e.g., ferritin, was not included in the study. This could have been used to explain better, the satisfactory level of hemoglobin in children, despite being exposed to a low amount of iron from groundwater. As per the British Geological Survey 2001 raw data, the very low iron (<0.8 mg/L) containing groundwater represents around 40% of the tube-wells in Bangladesh. The present study sample may not be representative of the wider population from which they were drawn and thus, the results should be interpreted with caution.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the study suggests that in low-iron groundwater settings in Bangladesh, the combined intake of iron from dietary and groundwater sources was associated with the maintenance of hemoglobin concentration at the non-anemic level in the majority of the 2-5 year-old children. The small proportion of the anemic children exposed to a very low level of iron from drinking groundwater might plausibly benefit from a low-dose iron supplement. A randomized controlled trial is required to confirm the findings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R., F.A., P.L. and M.R.K.; Methodology, S.R., F.A.; Staff training and supervision, M.R.K.; Statistical analysis; S.R., P.L.; Writing and formatting of manuscript, S.R., N.U.B.; Intellectual input and edits, F.A. and P.L.; All authors read and approved the final version for submission and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the article.

Funding

Funding was granted by the Nestle Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board. The study was nested in the trial, which received approval from the Research Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Biological Science, Dhaka University, Bangladesh (Ref# 46 /Biol. Scs. /2017-2018) and Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee, Australia (Ref# 2017/467). .

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding support of the Nestle Foundation for conduction of this research. We are grateful to the participants in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no competing interests.

References

- National Institute of Population Research and Training, Mitra and Associates, & ICF International (2013) Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Dhaka and Calverton, MD: NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and ICF International.

- Rahman, S.; Ahmed, T.; Rahman, A.S.; Alam, N.; Ahmed, A.M.S.; Ireen, S.; et al. Determinants of iron status and Hb in the Bangladesh population: The role of groundwater iron. Public Health Nutr. Access 2016, 19, 1862–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Anemia Consultation, Final Report, 24-25 July 2016, Dhaka, Bangladesh: Institute of Public Health Nutrition and United Nation Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

- National Strategy on Prevention and Control of Micronutrient Deficiency (2015-2024); http://iphn.dghs.gov.bd/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/NMDCS-.

- Sarma, H.; Mbuya, M.N.; Tariqujjaman; Rahman, M.; Askari, S.; Khondker, R.; Sultana, S.; Shahin, S.A.; Bossert, T.J.; Banwell, C.; et al. Role of home visits by volunteer community health workers: to improve the coverage of micronutrient powders in rural Bangladesh. Public Health Nutr 2021, 24, s48–s58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, S.K.; Akter, F.; Mukta, U.S.; Rahman, M. Exploration of Multiple Micronutrient Powder (MNP) Usage among Children of 6–59 Months in Bangladesh MIYCN Home Fortification Program (MIYCN Phase II areas); Working Paper; Research and Evaluation Division, BRAC: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2015 [CrossRef].

- Institute of Public Health Nutrition, UNICEF Bangladesh, icddr, b et al. (2013) National Micronutrient Survey, 2011–12, Final Report. Dhaka: Institute of Public Health Nutrition, United Nations Children’s Fund, Bangladesh, icddr,b and GAIN.

- Merrill, R.D.; Shamim, A.A.; Ali, H.; Jahan, N.; Labrique, A.B.; Schulze, K.; Christian, P.; West, K.P. Iron Status of Women Is Associated with the Iron Concentration of Potable Groundwater in Rural Bangladesh1–3. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British Geological Survey & Department for Public Health Engineering, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Arsenic Contamination of Groundwater in Bangladesh; BGS Technical Report, WC/00/19, Kinniburgh, D.G., Smedley, P.L., Eds.; BGS: Keyworth, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, S.; Lee, P.; Raqib, R.; Roy, A.K.; Khan, M.R.; Ahmed, F. Effect of Micronutrient Powder (MNP) with a Low-Dose of Iron on Hemoglobin and Iron Biomarkers, and Its Effect on Morbidities in Rural Bangladeshi Children Drinking Groundwater with a High-Level of Iron: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 3rd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, S. , Khan M.R., Lee P., Ahmed F. Development and standardization of taste-rating of the water sample as a semi-quantitative assessment of iron content in groundwater, Groundwater for Sustainable Development, Volume 11,2020, 100455, ISSN 2352-801X.

- Select Statistical Services Limited. https://select-statistics.co.uk/calculators/sample-size-calculator-population-mean/. Accessed on 30 August, 2020.

- Shaheen, N.; Rahim, A.T.; Mohiduzzaman, M.; Parvin Banu, C.; Bari, M.L.; Tukun, A.B. Food Composition Table for Bangladesh; Institute of Nutrition and Food Science Centre for Advanced Research in Sciences University of Dhaka: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2014.

- Mahfuz, M. , Alam, M.A., Islam, M.M., Mondal D., Hossain M.I., Ahmed A.M.S. et al. Effect of micronutrient powder supplementation for two and four months on hemoglobin level of children 6–23 months old in a slum in Dhaka: a community based observational study. BMC Nutr 2, 21 (2016).

- Institute of Medicine (2002) Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Human Vitamin and Mineral Requirements. Report of a joint FAO/WHO expert consultation Bangkok, Thailand. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization, Food and Nutrition Division FAO Rome 2001.

- Guidelines on food fortification with micronutrients/edited by Lindsay Allen et al. World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2006.

- Worwood, M.; Evans, W.; Villis, R.; Burnett, A. Iron absorption from a natural mineral water (Spatone Iron-Plus). Clin. Lab. Haematol. 1996, 18, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tondeur, M.C.; Schauer, C.S.; Christofides, A.L.; Asante, K.P.; Newton, S.; Serfass, R.E.; et al. Determination of iron absorption from intrinsically labeled microencapsulated ferrous fumarate (sprinkles) in infants with different iron and hematologic status by using a dual-stable-isotope method. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004, 80, 1436–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurrell, R.; Egli, I. Iron bioavailability and dietary reference values. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1461S–1467S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J. Understanding statistical analysis in the surgical literature: some key concepts. ANZ J. Surg. 2009, 79, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Prel, J.-B.; Hommel, G.; Röhrig, B.; Blettner, M. Confidence Interval or P-Value? Part 4 of a Series on Evaluation of Scientific Publications. Dtsch. Aerzteblatt Online 2009, 106, 335–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neufeld, L.M.; Larson, L.M.; Kurpad, A.; Mburu, S.; Martorell, R.; Brown, K.H. Hemoglobin concentration and anemia diagnosis in venous and capillary blood: biological basis and policy implications. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2019, 1450, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, S.; Ireen, S. Groundwater iron has the ground: Low prevalence of anemia and iron deficiency anemia in Bangladesh. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019, 110, 519–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boghani, S.; Mei, Z.; Perry, G.S.; Brittenham, G.M.; Cogswell, M.E. Accuracy of Capillary Hemoglobin Measurements for the Detection of Anemia among U.S. Low-Income Toddlers and Pregnant Women. Nutrients 2017, 9, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).