Submitted:

16 July 2024

Posted:

17 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

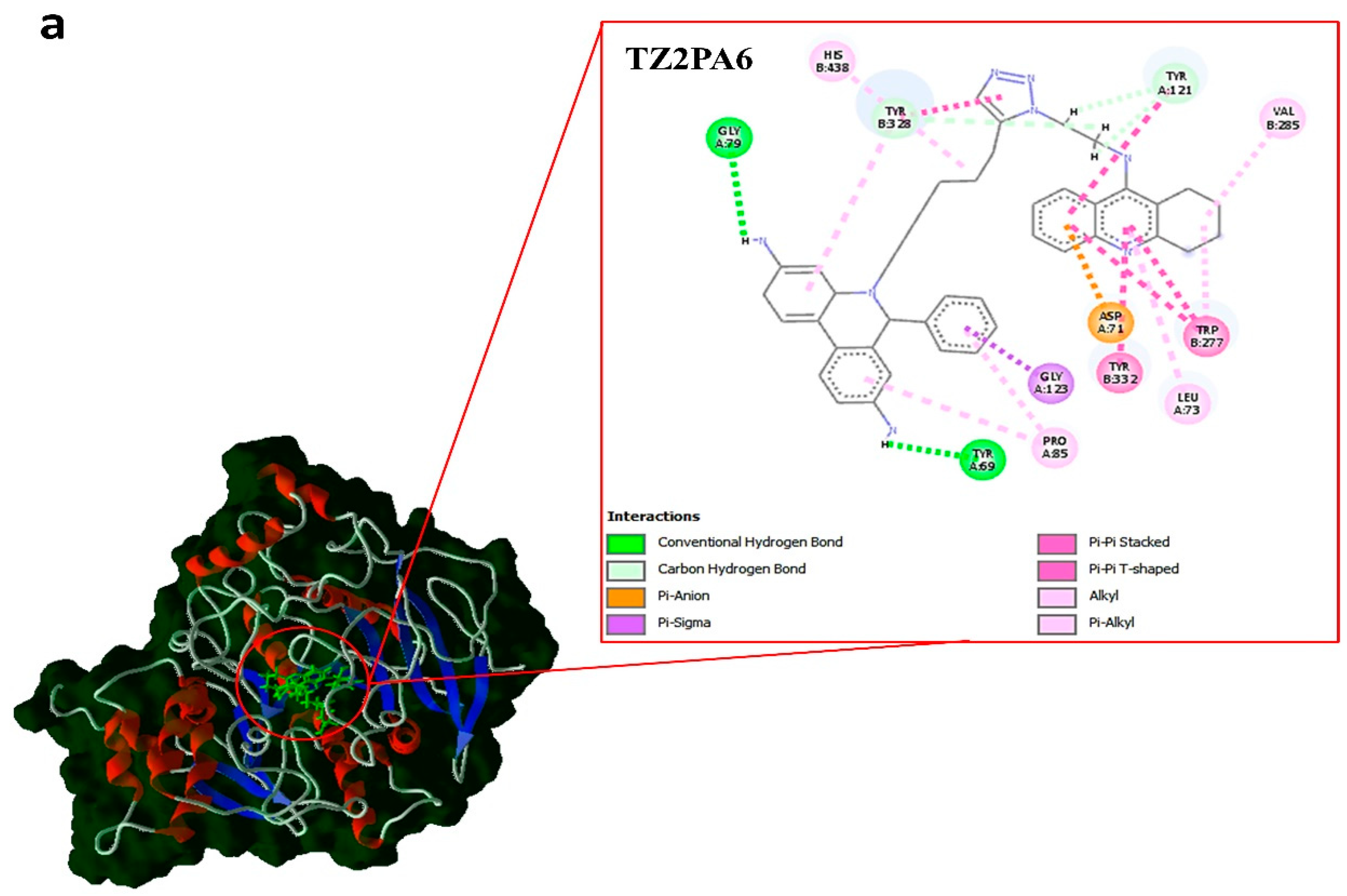

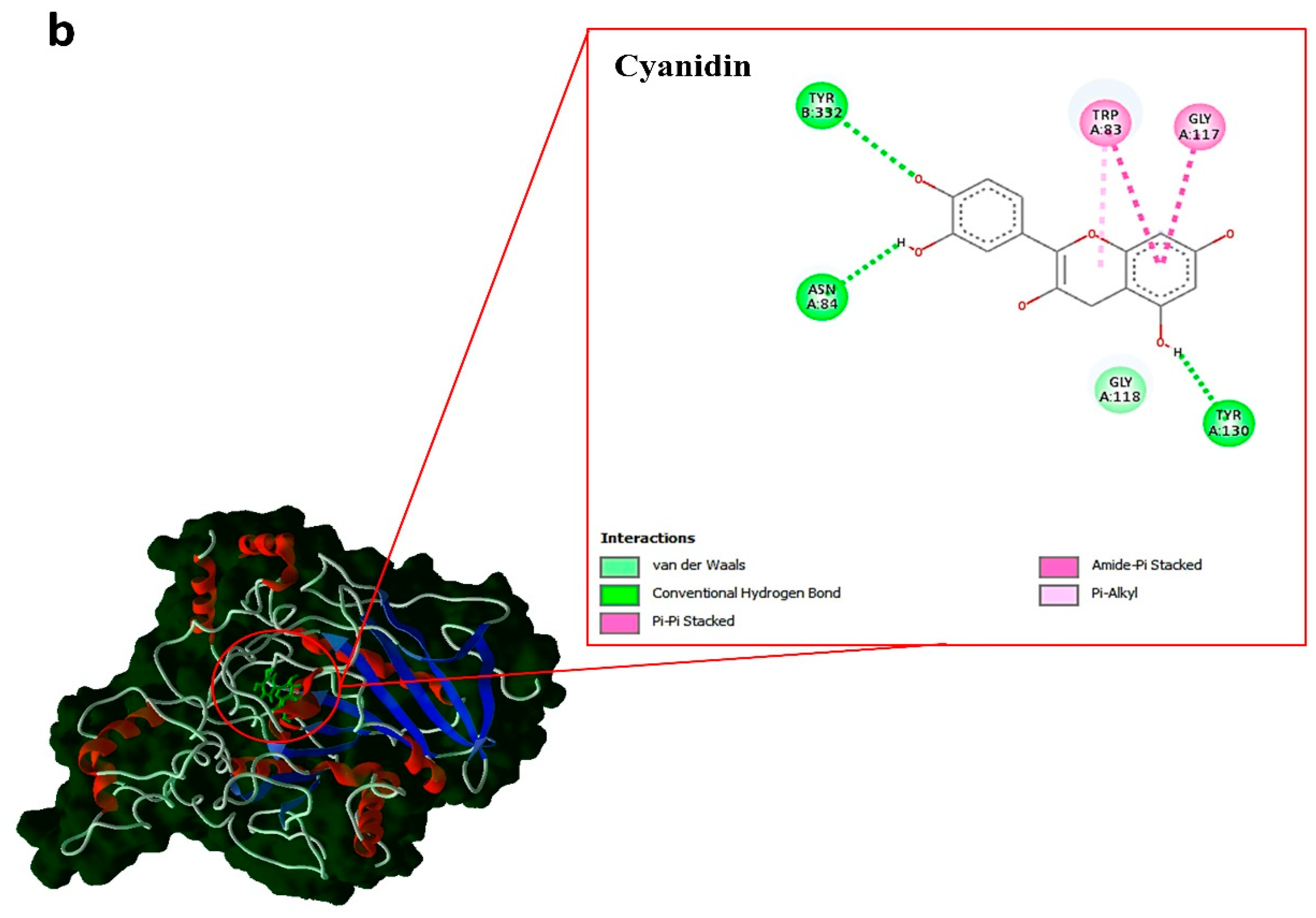

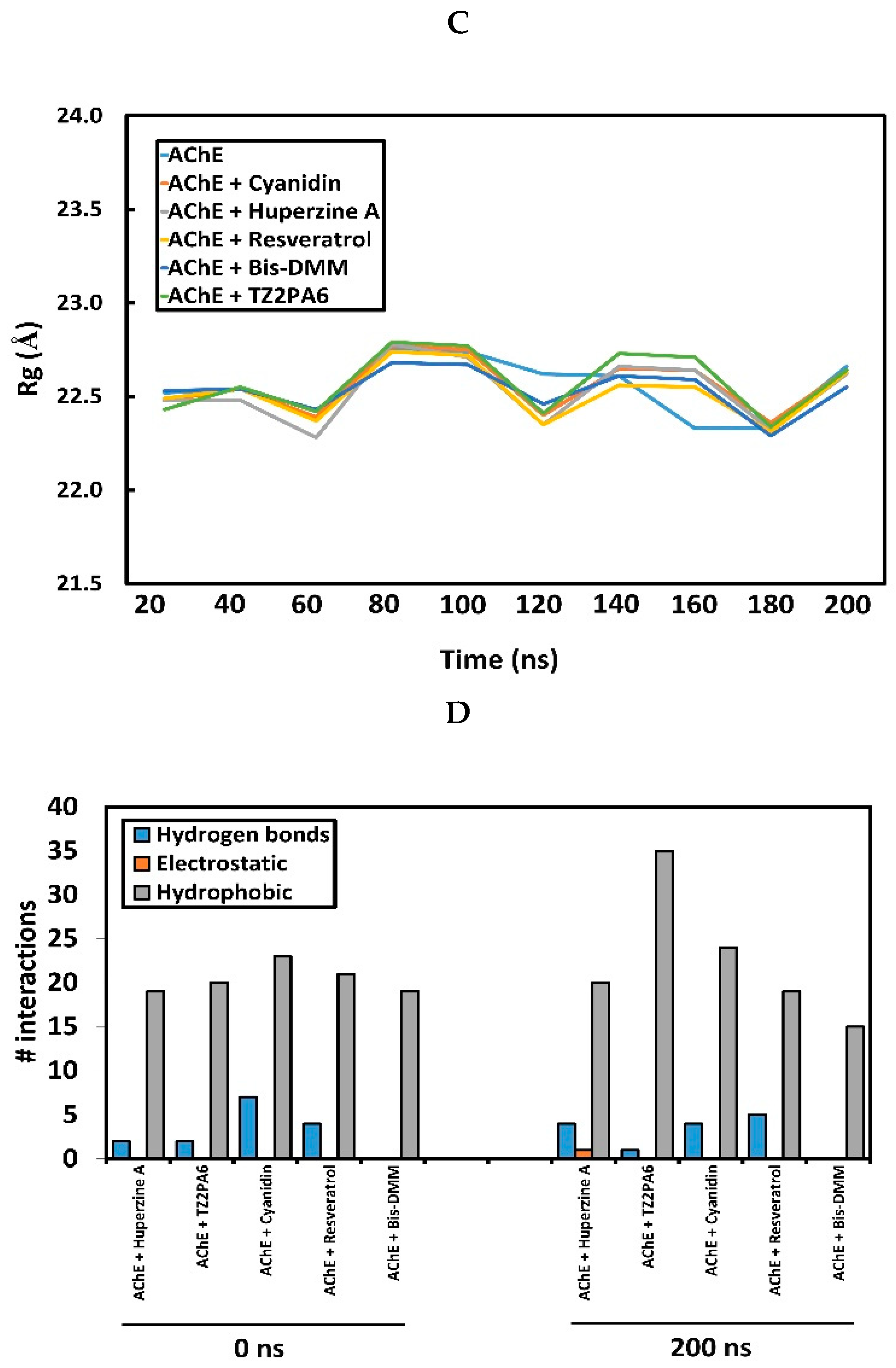

2.1. Docking, Inhibitory Potency and Molecular Dynamics (MD) Analysis

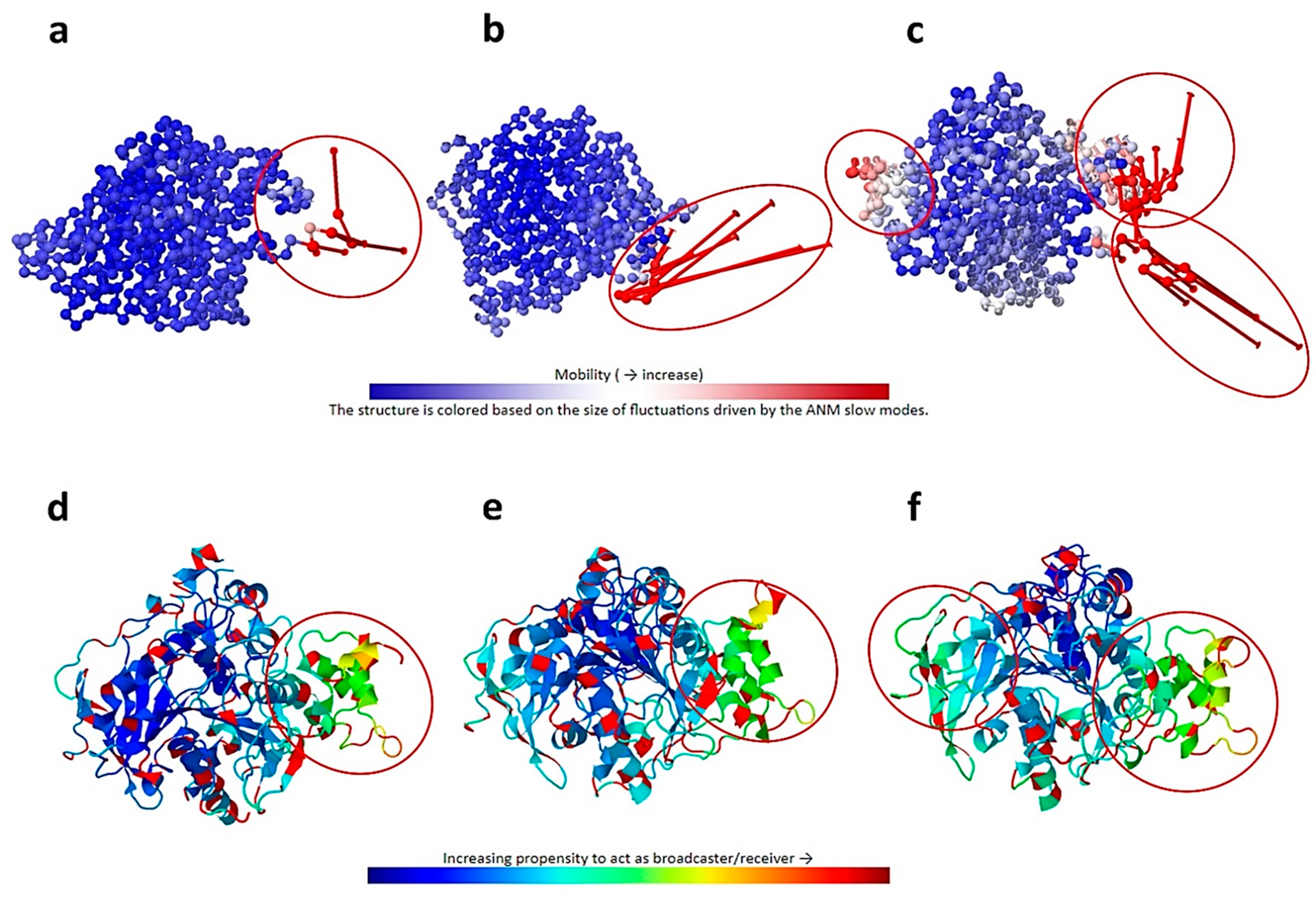

2.2. Analysis of Intrinsic Deformability Associated with AChE Conformational Changes

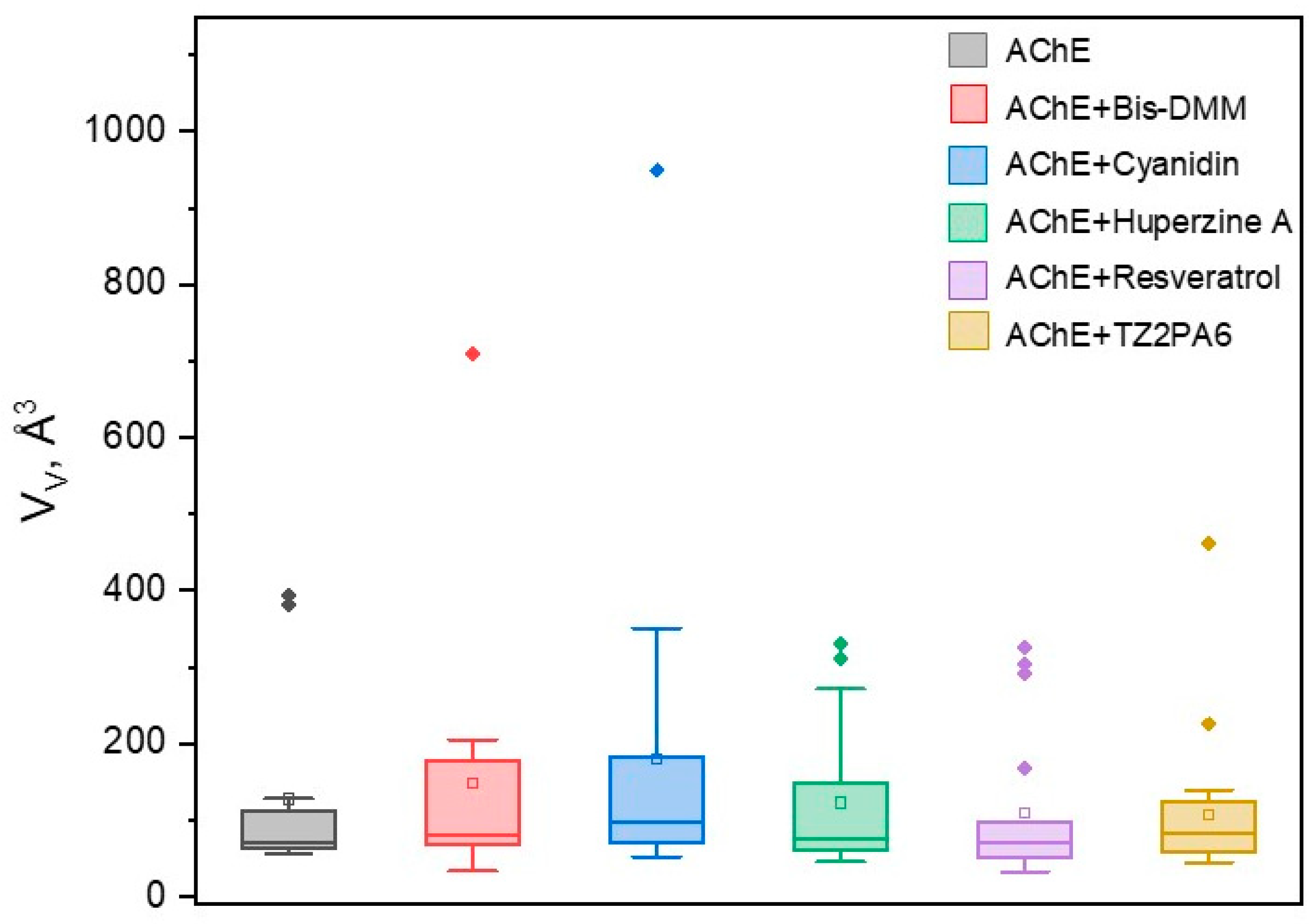

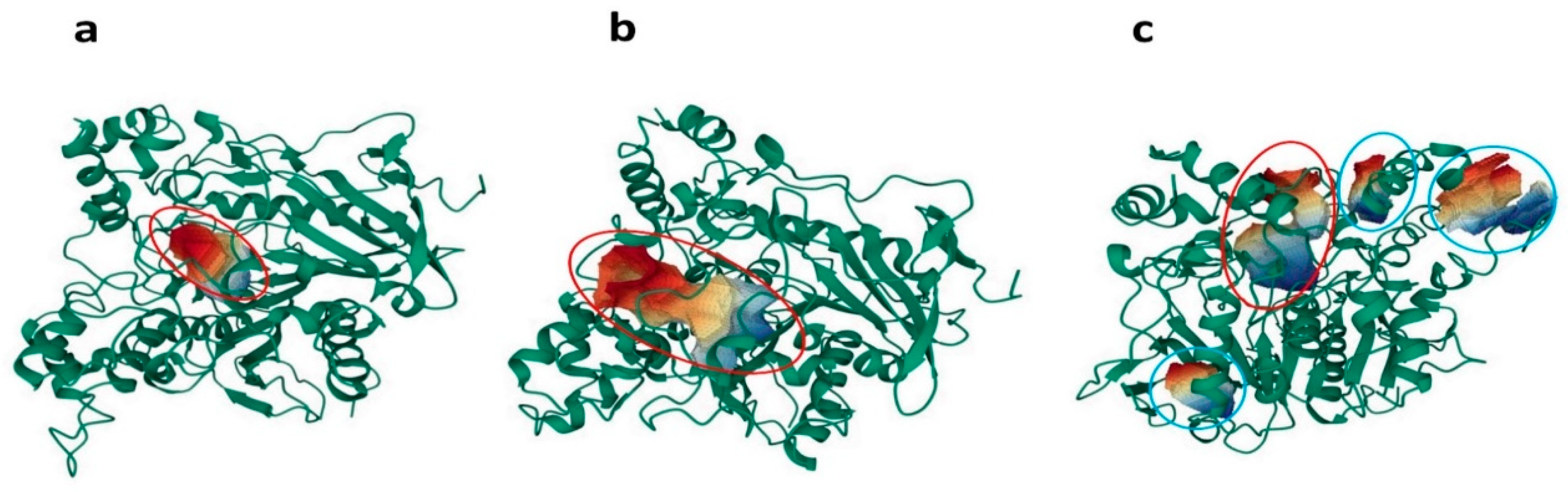

2.3. Volumetric Analysis of Internal Cavities

3. Materials and Methods

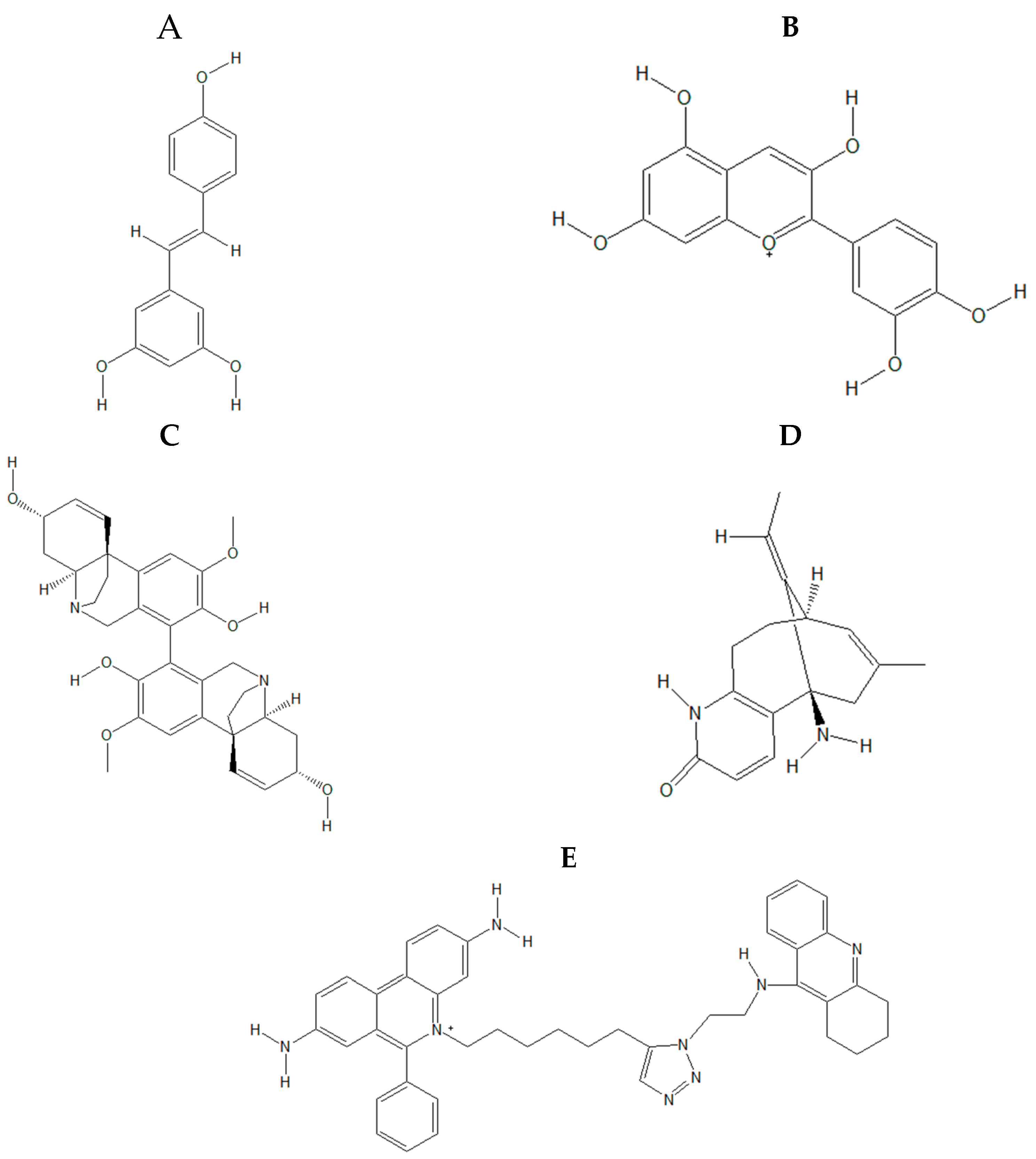

3.1. Selected Molecules and Preparation from Databases for Docking, Theoretical Inhibition, and Molecular Dynamics (MD)

3.2. Determination of Conformational Changes of Dynamized Complexes Using Statistical Potentials, Elastic Network Models, and Energy Frustration

3.2.1. Statistical Potentials of Complexes

3.2.2. Analysis of Intrinsic Deformability Associated with AChE Conformational Changes

3.2.3. Local Energy Frustration of Complexes

3.2.4. Volumetric Analysis of Internal Cavities

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- G. Marucci, M. Buccioni, D. Dal Ben, C. Lambertucci, R. Volpini, F. Amenta. Efficacy of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology. 2021 190, 108352. [CrossRef]

- I. Vecchio, L. Sorrentino, A. Paoletti, R. Marra, M. Arbitrio, The state of the art on acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cent. Nerv. Sys. Dis. 2021, 13, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- H. Khan, Mayra, S. Amin, M.A. Kamal, S. Patel, Flavonoids as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: Current therapeutic standing and future prospects. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018, 101, 860-870. [CrossRef]

- V. Dwibedi, S. Jain, D. Singhal, A. Mittal, S.K. Rath, S. Saxena, Inhibitory activities of grape bioactive compounds against enzymes linked with human diseases. App. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 1399-1417. [CrossRef]

- B.Y. Chávez, J.L. Paz, L.A. Gonzalez-Paz, Y.J. Alvarado, J.S. Contreras, M.A. Loroño-González. Theoretical Study of Cyanidin-Resveratrol Copigmentation by the Functional Density Theory. Molecules. 2024, 29, 2064. [CrossRef]

- A. Ali, J.J. Cottrell, F.R. Dunshea. Identification and characterization of anthocyanins and non-anthocyanin phenolics from Australian native fruits and their antioxidant, antidiabetic, and anti-Alzheimer potential. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 111951. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhang, J. Xue, X. Chen, F.G. Elsaid, E.T. Salem, E.A. Ghanem, A.F. El-Kott, Z. Xu, Bioactivity of hamamelitannin, flavokawain A, and triacetyl resveratrol as natural compounds: Molecular docking study, anticolon cancer, and anti-Alzheimer potentials. Biotechnol. App. Biochem. 2023, 70, 730-745. [CrossRef]

- C. Dini, M.J. Zaro, S.Z. Viña, Bioactivity and functionality of anthocyanins: A review. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2019, 15, 507-523. [CrossRef]

- Alesci, A., Nicosia, N., Fumia, A., Giorgianni, F., Santini, A., & Cicero, N. Resveratrol and immune cells: a link to improve human health. Molecules. 2022, 27, 424. [CrossRef]

- T.J Narwani 1, C. Etchebest, P. Craveur, S.Léonard, J. Rebehmed, N. Srinivasan, A. Bornot, J-C. Gelly, A.G. de Brevern, In silico prediction of protein flexibility with local structure approach, Biochimie. 2019, 165, 150-155. [CrossRef]

- S.P Tiwari, E. Fuglebakk, S.M. Hollup, L. Skjærven, T. Cragnolini, S.H. Grindhaug, K.M. Tekle, N. Reuter, WEBnm@ v2. 0: Web server and services for comparing protein flexibility. BMC bioinformatics. 2014, 15, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- T. Hrabe, Z. Li, M. Sedova, P. Rotkiewicz, L. Jaroszewski, A.Godzik, PDBFlex: exploring flexibility in protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D423-D428. [CrossRef]

- M. Grimm, T. Zimniak, A. Kahraman, F. Herzog, xVis: a web server for the schematic visualization and interpretation of crosslink-derived spatial restraints. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W362-W369. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, P. Doruker, B. Kaynak, S. Zhang, J. Krieger, H. Li, I. Bahar, Intrinsic dynamics is evolutionarily optimized to enable allosteric behavior. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2020, 62, 14-21. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Bui, J.A. McCammon, Intrinsic conformational flexibility of acetylcholinesterase. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2008, 175, 303-304. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bourne, Z. Radić, H.C. Kolb, K.B. Sharpless, P. Taylor, P. Marchot, Structural insights into conformational flexibility at the peripheral site and within the active center gorge of AChE, Chem. Biol. Interact. 2005, 157, 159-165. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bourne, Z. Radić, P. Taylor, P. Marchot, Conformational remodeling of femtomolar inhibitor− acetylcholinesterase complexes in the crystalline state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 18292-18300. [CrossRef]

- K. Hamacher, Efficient perturbation analysis of elastic network models–Application to acetylcholinesterase of T. californica. J. Computat. Phys. 2010, 229, 7309-7316. [CrossRef]

- C.H.M. Rodrigues, D.E.V. Pires, D.B. Ascher, DynaMut: predicting the impact of mutations on protein conformation, flexibility and stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W350-W355. [CrossRef]

- E. Eyal, G. Lum, I. Bahar, The anisotropic network model web server at 2015 (ANM 2.0). Bioinformatics. 2015, 31, 1487-1489. [CrossRef]

- A. Felline, M. Seeber, F. Fanelli, webPSN v2. 0: a webserver to infer fingerprints of structural communication in biomacromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W94-W103. [CrossRef]

- L. González-Paz, M.L. Hurtado-León, C. Lossada, F.V. Fernández-Materán, J. Vera-Villalobos, M. Loroño, J.L. Paz, L. Jeffreys, Y.J. Alvarado. Structural deformability induced in proteins of potential interest associated with COVID-19 by binding of homologues present in ivermectin: Comparative study based in elastic networks models. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 340, 117284. [CrossRef]

- A. Delgado, J. Vera-Villalobos, J.L. Paz, C. Lossada, M.L. Hurtado-León, Y. Marrero-Ponce, J. Toro-Mendoza, Y.J. Alvarado, L. González-Paz. Macromolecular crowding impact on anti-CRISPR AcrIIC3/NmeCas9 complex: Insights from scaled particle theory, molecular dynamics, and elastic networks models. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023, 244, 125113. [CrossRef]

- L. González-Paz, C. Lossada, M.L. Hurtado-León, J. Vera-Villalobos, J.L. Paz, Y. Marrero-Ponce, F. Martinez-Rios, Y.J. Alvarado, Biophysical Analysis of Potential Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Cell Recognition and Their Effect on Viral Dynamics in Different Cell Types: A Computational Prediction from In Vitro Experimental Data. ACS Omega. 2024, 9, 8923–8939. [CrossRef]

- A. Bakan, I. Bahar. The intrinsic dynamics of enzymes plays a dominant role in determining the structural changes induced upon inhibitor binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009, 106 14349-14354. [CrossRef]

- Q. Hou, F. Pucci, F. Ancien, J-M. Kwasigroch, R. Bourgeas, M. Rooman, SWOTein: a structure-based approach to predict stability strengths and weaknesses of prOTEINs. Bioinformatics. 2021, 37, 1963-1971. [CrossRef]

- V. Parthiban, M.M. Gromiha, M. Abhinandan, D. Schomburg. Computational modeling of protein mutant stability: analysis and optimization of statistical potentials and structural features reveal insights into prediction model development. BMC Struct. Biol. 2007, 7, 54. [CrossRef]

- R.G. Parra, N.P. Schafer, L.G. Radusky, M.Y. Tsai, A.B. Guzovsky, P.G. Wolynes, D.U. Ferreiro, Protein Frustratometer 2: a tool to localize energetic frustration in protein molecules, now with electrostatics, Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W356-W360. [CrossRef]

- M. Jenik, R.G. Parra, L.G. Radusky, A. Turjanski, P.G. Wolynes, D.U. Ferreiro, Protein frustratometer: a tool to localize energetic frustration in protein molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W348-W351. [CrossRef]

- A.O. Rausch, M.I. Freiberger, C.O. Leonetti, D.M. Luna, L.G. Radusky, P.G. Wolynes, D.U. Ferreiro, R. Gonzalo Parra, FrustratometeR: an R-package to compute local frustration in protein structures, point mutants and MD simulations. Bioinformatics. 2021, 37, 3038-3040. [CrossRef]

- Suwanhom, P., Nualnoi, T., Khongkow, P., Tipmanee, V., & Lomlim, L. Novel Lawsone–Quinoxaline Hybrids as New Dual Binding Site Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors. ACS omega. 2023, 8, 32498-32511. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, R. B., Barbosa, D. B., do Bomfim, M. R., Amparo, J. A., Andrade, B. S., Costa, S. L., ... & Botura, M. B. Identification of a novel dual inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase: in vitro and in silico studies. Pharmaceuticals. 2023, 16, 95. [CrossRef]

- I.A. Guedes, L.S.C. Costa, K.B Dos Santos, A.L M Karl, G.K. Rocha, I.M. Teixeira, M.M. Galheigo, V. Medeiros, E. Krempser, F.L. Custódio, H.J.C Barbosa, M.F. Nicolás, L.E. Dardenne. Drug design and repurposing with DockThor-VS web server focusing on SARS-CoV-2 therapeutic targets and their non-synonym variants. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5543. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, X. Wang, Y. Li, T. Lei, E. Wang, D. Li, Y. Kang, F. Zhu, T. Hou, farPPI: a webserver for accurate prediction of protein-ligand binding structures for small-molecule PPI inhibitors by MM/PB (GB) SA methods. Bioinformatics. 2019, 35, 1777-1779. [CrossRef]

- E.C. Dykeman, O.F. Sankey. Normal mode analysis and applications in biological physics, J. Phys. Condens. Mat. 2010, 22, 423202. http://iopscience.iop.org/0953-8984/22/42/423202.

- L.A. González-Paz, C.A. Lossada, L.S. Moncayo, F. Romero, J.L. Paz, J. Vera-Villalobos, A.E. Pérez, E. Portillo, E. San-Blas, Y.J. Alvarado. A Bioinformatics Study of Structural Perturbation of 3CL-Protease and the HR2-Domain of SARS-CoV-2 Induced by Synergistic Interaction with Ivermectins. BRIAC. 2021, 11, 9813. [CrossRef]

- C. Chennubhotla, I. Bahar. Signal Propagation in Proteins and Relation to Equilibrium Fluctuations. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2007, 3, e172. [CrossRef]

- J. Cheung, M.J. Rudolph, F. Burshteyn, M.S. Cassidy, E.N. Gary, J. Love, M.C. Franklin, J.J. Height, Structures of human acetylcholinesterase in complex with pharmacologically important ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 10282-10286. [CrossRef]

- N.V. Duc, V.T. Trang, H.L.T. Anh, L.B. Vinh, N.V. Phong, T.Q. Thuan, N.V. Hieu, N.T. Dat, L.V. Nhan, D.T. Tuan, L.T. Anh, D.T. Thao, B.H. Tai, N.C. Cuong, L.Q. Lien, S.Y. Yang, Acetylcholinesterase inhibition studies of alkaloid components from Crinum asiaticum var. sinicum: in vitro assessments by molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2023, 26, 652-662. [CrossRef]

- L. Ponzoni, G. Polles, V. Carnevale, C. Micheletti, SPECTRUS: A dimensionality reduction approach for identifying dynamical domains in protein complexes from limited structural datasets. Structure. 2015, 23, 1516-1525. [CrossRef]

- A. Felline, M. Seeber, F. Fanelli, webPSN v2. 0: a webserver to infer fingerprints of structural communication in biomacromolecules, Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2020, 48, W94-W103. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, Y-Y Chang, J.Y. Lee, I. Bahar, L-W. Yang. DynOmics: dynamics of structural proteome and beyond. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W374-W380. [CrossRef]

- L. González-Paz, C. Lossada, M.L. Hurtado-León, F.V. Fernández-Materán, J.L. Paz, S. Parvizi, R.E. Cardenas-Castillo, F. Romero, Y.J Alvarado, Intrinsic Dynamics of the ClpXP Proteolytic Machine Using Elastic Network Models. ACS omega. 2023, 8, 7302-7318. [CrossRef]

- L. Alzyoud, R.A. Bryce, M. Al Sorkhy, N. Atatreh, M.A. Ghattas. Structure-based assessment and druggability classification of protein–protein interaction sites. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7975. [CrossRef]

- H.A. Hussein, A. Borrel, C. Geneix, M. Petitjean, L. Regad, A-C. Camproux, PockDrug-Server: a new web server for predicting pocket druggability on holo and apo proteins. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2015, 43, W436-W442. [CrossRef]

- K. Singh, R.B. Patil, V. Patel, J. Remenyik, T. Hegedűs, K. Goda. Synergistic Inhibitory Effect of Quercetin and Cyanidin-3O-Sophoroside on ABCB1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11341. [CrossRef]

- H. Abi Hussein, C. Geneix, M. Petitjean, A. Borrel, D. Flatters, A-C. Camproux, Global vision of druggability issues: applications and perspectives. Drug. Discov. Today. 2017, 22, 404-415. [CrossRef]

- Y.J. Alvarado, Y. Olivarez, C. Lossada, J. Vera-Villalobos, J.L. Paz, E. Vera, M. Loroño, A. Vivas, F.J. Torres, L.N. Jeffreys, M.L. Hurtado-León, L. González-Paz. Interaction of the new inhibitor paxlovid (PF-07321332) and ivermectin with the monomer of the main protease SARS-CoV-2: A volumetric study based on molecular dynamics, elastic networks, classical thermodynamics and SPT. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2022, 99, 107692. [CrossRef]

- G. Bitencourt-Ferreira, W. Filgueira de Azevedo Jr, Molegro virtual docker for docking, Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 2053, 149-167. [CrossRef]

- U. Baroroh, M. Biotek, Z.S. Muscifa, W. Destiarani, F.G. Rohmatullah, M. Yusuf, Molecular interaction analysis and visualization of protein-ligand docking using Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer, Ind. J. Comput. Biol. 2023, 2, 22-30. [CrossRef]

- I.A. Guedes, M.M. Pereira da Silva, M. Galheigo, E. Krempser, C. Silva de Magalhães, H.J. Correa Barbosa, L.E. Dardenne. DockThor-VS: A Free Platform for Receptor-Ligand Virtual Screening. J. Mol. Biol. 2024, 168548. [CrossRef]

- L.A. González-Paz, C.A. Lossada, F.V. Fernández-Materán, J.L. Paz, J. Vera-Villalobos, Y.J. Alvarado. Can Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs Affect the Interaction Between Receptor Binding Domain of SARS-COV-2 Spike and the Human ACE2 Receptor? A Computational Biophysical Study. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 587606. [CrossRef]

- Nour, H., Hashmi, M. A., Belaidi, S., Errougui, A., El Kouali, M., Talbi, M., & Chtita, S. Design of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors as Promising Anti-Alzheimer’s Agents Based on QSAR, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Studies of Liquiritigenin Derivatives. ChemistrySelect. 2023, 8, e202301466. [CrossRef]

- Lan, N. T., Vu, K. B., Ngoc, M. K. D., Tran, P. T., Hiep, D. M., Tung, N. T., & Ngo, S. T. Prediction of AChE-ligand affinity using the umbrella sampling simulation. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2019, 93, 107441. [CrossRef]

- Sirin, G. S., & Zhang, Y. How is acetylcholinesterase phosphonylated by soman? An ab initio QM/MM molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2014, 118, 9132-9139. [CrossRef]

- Sirin, G. S., Zhou, Y., Lior-Hoffmann, L., Wang, S., & Zhang, Y. Aging mechanism of soman inhibited acetylcholinesterase. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012, 116, 12199-12207. [CrossRef]

- K. Kasahara, H. Terazawa, H. Itaya, S. Goto, H. Nakamura, T. Takahashi, J. Higo, myPresto/omegagene 2020: a molecular dynamics simulation engine for virtual-system coupled sampling. Biophys. Physicobiol. 2020, 17, 140–146. [CrossRef]

- P. Coghi, L.J. Yang, J.P.L. Ng, R.K. Haynes, M. Memo, A. Gianoncelli, V.K. Wai Wong, G. Ribaudo. A drug repurposing approach for antimalarials interfering with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor binding domain (RBD) and human angiotensin - converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Pharmaceuticals. 2021, 14, 954. [CrossRef]

- R. Kumari, V. Kumar, P. Dhankhar, V. Dalal, Promising antivirals for PLpro of SARS-CoV-2 using virtual screening, molecular docking, dynamics, and MMPBSA. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 4, 4650-4666. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, H. Pan, H. Sun, Y. Kang, H. Liu, D. Cao, T. Hou. fastDRH: a webserver to predict and analyze protein–ligand complexes based on molecular docking and MM/PB (GB) SA computation. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac201. [CrossRef]

- V. Parthiban, M.M. Gromiha, D. Schomburg, CUPSAT: prediction of protein stability upon point mutations, Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W239-W242. [CrossRef]

- Q. Hou, F. Pucci, F. Ancien, J.M. Kwasigroch, R. Bourgeas, M. Rooman, SWOTein: a structure-based approach to predict stability strengths and weaknesses of prOTEINs. Bioinformatics. 2021, 37, 1963-1971. [CrossRef]

- A. Ahmed, F. Rippmann, G. Barnickel, H. Gohlke, A normal mode-based geometric simulation approach for exploring biologically relevant conformational transitions in proteins, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011, 51, 1604-1622. [CrossRef]

- J.R, López-Blanco, J.I. Aliaga, E.S. Quintana-Ortí, P. Chacón, iMODS: internal coordinates normal mode analysis server, Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2014, 42, W271-W276. [CrossRef]

- L. Skjaerven, S.M. Hollup, N. Reuter. Normal mode analysis for proteins, J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM. 2009, 898, 42-48. [CrossRef]

- P. Doruker, A.R. Atilgan, I. Bahar, Dynamics of proteins predicted by molecular dynamics simulations and analytical approaches: Application to α-amylase inhibitor, Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 2000, 40, 512-524. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Atilgan, S. R. Durell, R. L. Jernigan, M. C. Demirel, O. Keskin, I. Bahar, Anisotropy of fluctuation dynamics of proteins with an elastic network model, Biophys. J. 2001, 80, 505-515. [CrossRef]

- M. Seeber, A. Felline, F. Raimondi, S. Muff, R. Friedman, F. Rao, F. Fanelli, Wordom: a user-friendly program for the analysis of molecular structures, trajectories, and free energy surfaces, J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1183-1194. [CrossRef]

- U. Emekli, D. Schneidman-Duhovny, H.J. Wolfson, R. Nussinov, T. Haliloglu, HingeProt: automated prediction of hinges in protein structures, Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 2008, 70, 1219-1227. [CrossRef]

- L. Pravda, D. Sehnal, D. Toušek, V. Navrátilová, V. Bazgier, K. Berka, R.S. Vareková, J. Koca, M. Otyepka, MOLEonline: a web-based tool for analyzing channels, tunnels and pores. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2018, 46, W368-W373. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, J. Xie, J. Pei, L. Lai. CavityPlus 2022 update: an integrated platform for comprehensive protein cavity detection and property analyses with user-friendly tools and cavity databases. J. Mol. Biol. 2023, 435, 168141. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, S. Wang, Q. Hu, S. Gao, X. Ma, W. Zhang, Y. Shen, F. Chen, L. Lai, J. Pei. CavityPlus: a web server for protein cavity detection with pharmacophore modelling, allosteric site identification and covalent ligand binding ability prediction. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2018, 46, W374-W379. [CrossRef]

| Compounds | type | kcal.mol–1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DockTScore | MM/PBSAa | MM/PBSAb | ||

| TZ2PA6 | chemistry click | -12.03 | -9.14 | -38.78 |

| Cyanidin | flavonoid | -9.50 | -5.51 | -17.21 |

| Bis-DMM | alkaloid | -8.97 | -1.37 | -16.06 |

| Resveratrol | polyphenol | -8.95 | -3.48 | -10.6 |

| Huperzine A | alkaloid | -8.95 | -9.64 | -22.74 |

| Compounds | µM | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki | IC50 | pIC50 | ||

| TZ2PA6 | 4.0a* | - | 9.7 | [17] |

| Cyanidin | 2.9b | 5.7b | 12.2 | This work |

| Bis-DMM | - | 80.7* | 4.1 | [39] |

| Resveratrol | 0.02 | 0.04 | 7.4 | This work |

| Huperzine A | - | 0.02* | 7.7 | [38] |

| Complex | Distance | ASA | ϕ | Ψ | Q | QS | #Nodes | #Links | Collectivity | Receiver | C | f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AChE | -206.53 | -50.23 | -76.26 | 39.83 | 19 | 3.12 | 104 | 103 | 0.501 | 0.033 | 986.87 | 0.76 |

| AChE + Huperzine A | -156.44 | -37.90 | -76.76 | 35.42 | 11 | 3.68 | 96 | 95 | 0.563 | 0.027 | 985.04 | 0.75 |

| AChE + TZ2PA6 | -153.51 | -33.02 | -77.55 | 37.79 | 4 | 3.29 | 101 | 100 | 0.564 | 0.031 | 972.16 | 0.83 |

| AChE + Cyanidin | -156.22 | -24.35 | -75.77 | 37.93 | 21 | 3.38 | 129 | 128 | 0.584 | 0.035 | 991.64 | 0.86 |

| AChE + Resveratrol | -152.85 | -30.07 | -75.82 | 34.81 | 17 | 3.02 | 126 | 125 | 0.532 | 0.028 | 975.85 | 0.85 |

| AChE + Bis-DMM | -158.18 | -27.63 | -76.63 | 39.08 | 6 | 3.31 | 89 | 88 | 0.505 | 0.030 | 971.18 | 0.75 |

| complex | (Å3) | Drugg. Prob. |

Pockets Drugg Prob. = 1.0 |

Nb. Res. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | min | max | (Å3) | (%) | (%) | mean | |

| AChE | 127.33 | 56 | 393 | 117.64 | 94 | 17 | 19 |

| AChE + Huperzine A | 122.50 | 45 | 331 | 88.87 | 91 | 20 | 19 |

| AChE + TZ2PA6 | 107.48 | 44 | 461 | 82.43 | 74 | 40 | 21 |

| AChE + Cyanidin | 180.07 | 52 | 949 | 222.85 | 95 | 75 | 24 |

| AChE + Resveratrol | 108.77 | 32 | 325 | 93.46 | 82 | 17 | 22 |

| AChE + Bis-DMM | 147.31 | 33 | 709 | 155.35 | 61 | 20 | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).