Submitted:

11 July 2024

Posted:

12 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

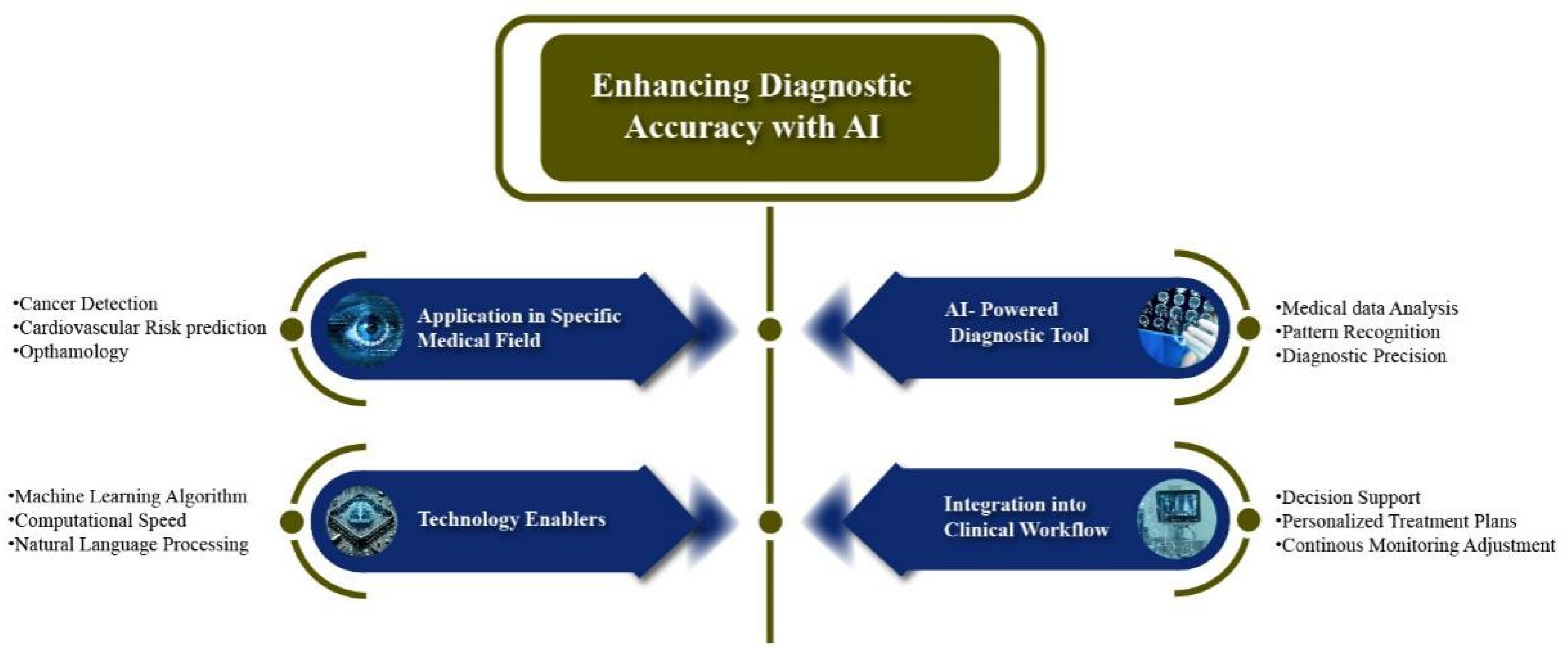

1.1. Enhancing Diagnostic Accuracy with AI:

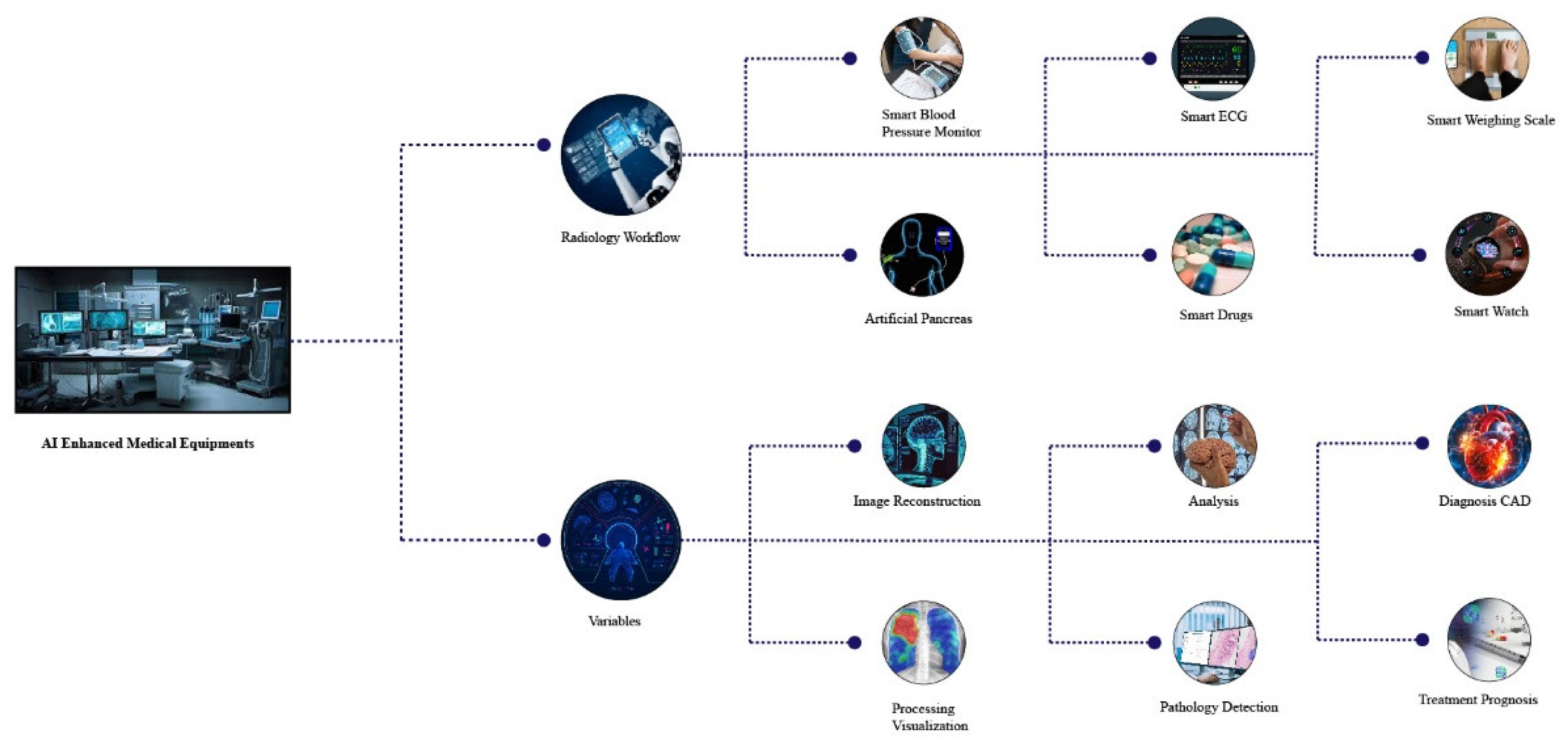

1.2. AI-Enabled Medical Equipment Innovations:

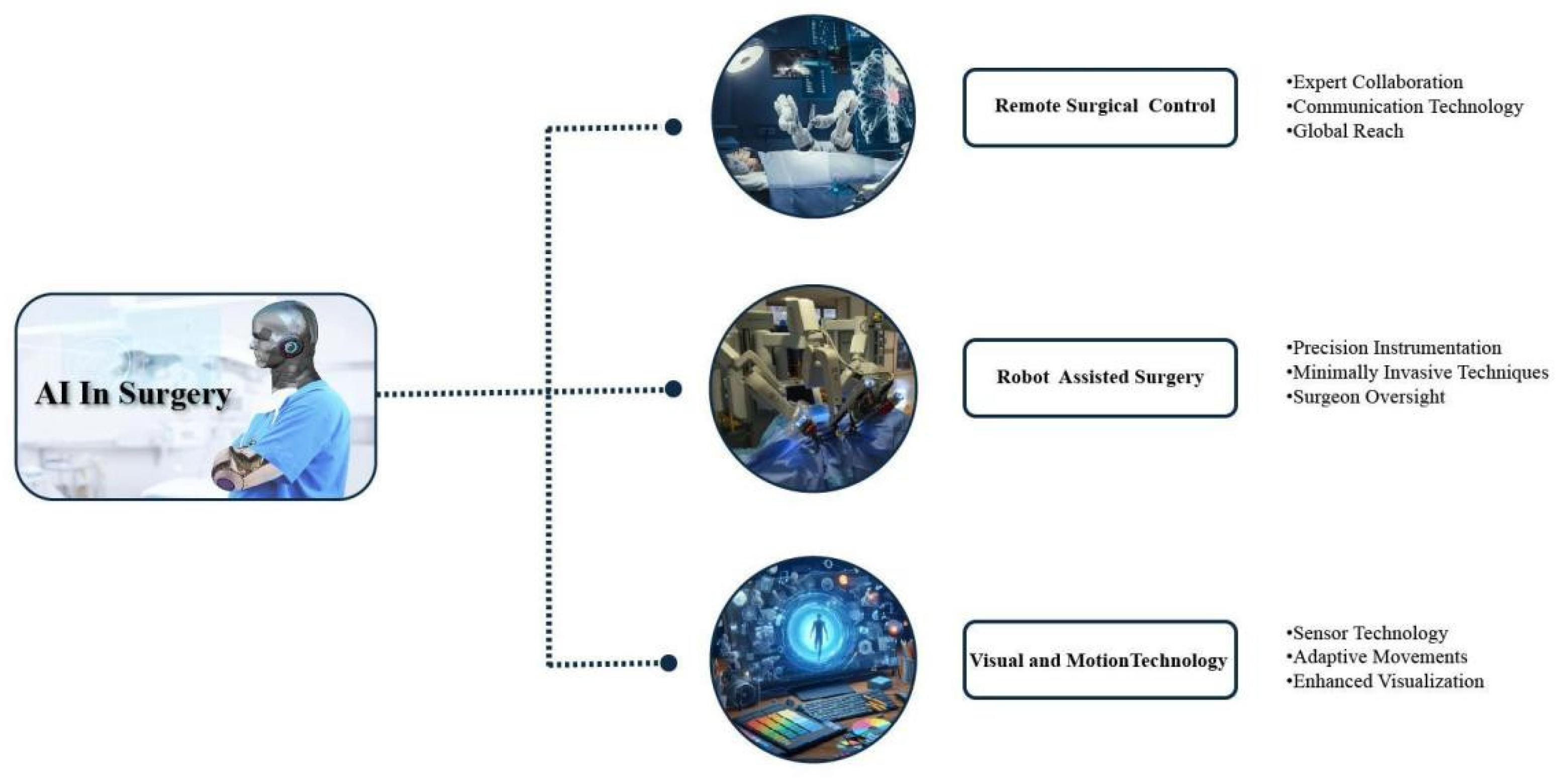

1.3. Al driven robotic Surgical Precision

| Sample | AI Tecniques | Stages | Phase of opration | Performance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 surgeons; 3 tasks (from 20 to 24 trials for each task); JIGSAWS (all 3 tasks) | CNN | Pre-operative | Knot tyationing, suturing, and needle passage on inanimate models | RMSE: 7.0 s for one task | [52] |

| JIGSAWS Data base for all 3 tasks(knot tying , suturing needle passage ) | 3D CNN + TSN | Pre-operative | Knot tying, suturing, and needle passage on inanimate models | Accuracy: 95.1%–100.0%; Sensitivity: 94.2%–100.0% | [53] |

| JIGSAWS all 3 tasks (knot tying , suturing needle passage ) | CNN | Pre-operative | Knot tying, suturing, and needle passage on inanimate models | Accuracy: 91.3%–95.4% | [54] |

| JIGSAWS Data base forall 3 tasks (knot tying , suturing needle passage ) | PCA, kNN, SVR | Pre-operative | Knot tying, suturing, and needle passage on inanimate models | Accuracy: 77.4%–100.0% | [55] |

| JIGSAWS Data base for 2 tasks(Knoting , suituning) | kNN, LR, SVM | Pre-operative | Knot tying, suturing, and needle passage on inanimate models | Accuracy: 77.9%–82.3% (knot tying); 79.8%–89.9% (suturing) | [56] |

| JIGSAWS Dtabase all 3 tasks (knot tying , suturing needle passage | FCN | Pre-operative | Knot tying, suturing, and needle passage on inanimate models | Accuracy: 92.1%–100.0% | [57] |

| JIGSAWS (all 3 tasks); 9 surgeons; 5 tasks | Clustering and PCA; Temporal clustering: HACA, ACA, SC, GMM | Pre-operative; Post-operative | Knot tying, suturing, and needle passage on inanimate models; Various surgical tasks on porcine model | Sensitivity: 71.2%–83.3%; Precision 72.6%–81.2%; Accuracy: 50.6%–88.0% (HACA) | [58],[59] |

| 3 tasks; 10 trials for circle cutting, 28 trials for needle passage, and 39 trials for suturing | GMM | Pre-operative | Circle cutting, needle passage, and suturing on inanimate model | Comparison of transition accuracy with JIGSAWS: 73.0%–83.0% | [60] |

| 2 urologists and 1 engineer; 2 tasks; Trajectories for drawing and peg transfer | kNN, SVM | Pre-operative | Drawing of ‘R’ letter and peg transfer on inanimate model | Accuracy for gesture classification: 97.4% (kNN), 96.2% (SVM) | [61] |

| 20,000 COCO images, endoscopic images and videos from MICCAI EndoVis 2017 | U-Net and conditional GAN | Post-operative | Tools segmentation in nephrectomies and laparoscopic surgeries | DSC: 65.0%–68.0% | [62] |

| 225 frame sequences from 8 surgeries of MICCAI EndoVis 2017 | GAN | Post-operative | Tools segmentation in operations on porcine model | DSC: 91.6% (binary segmentation); 73.8% (parts segmentation) | [63] |

| Atlas (86 videos by 10 surgeons); MICCAI EndoVis 2015 videos | CNN | Post-operative | Tool detection in surgical training and procedures | mAP: 98.5% (Atlas Dione), 100.0% (EndoVis) | [64] |

| 24 procedures | CNN | Post-operative | Surgical procedure recognition | Recognition metrics not detailed | [65] |

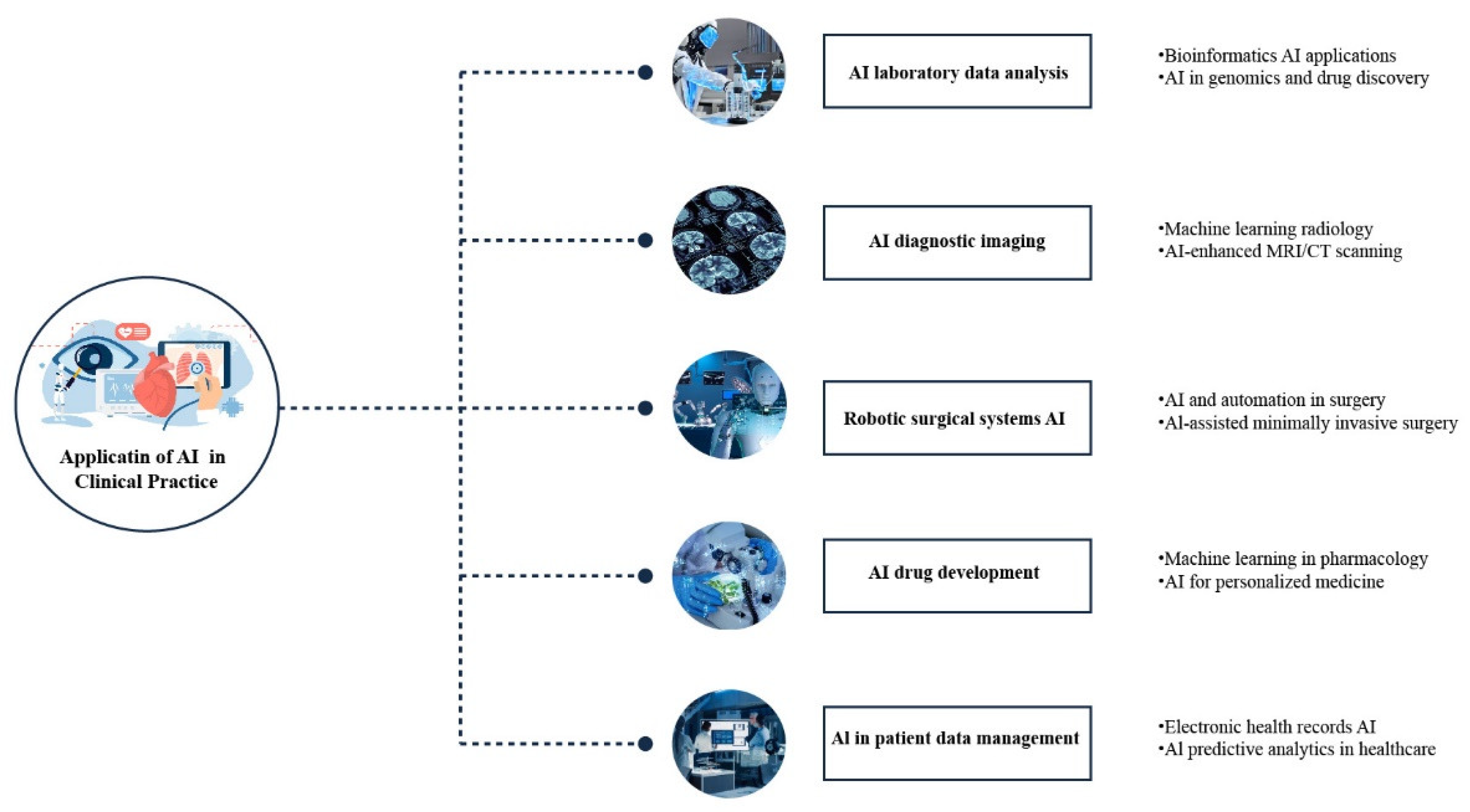

1.4. Elevating Patient Care with AI Technologies

2. Strategies for Effective AI Adoption

2.1. Standardizing AI Technologies for Better Medical Outcomes

2.2. Addressing the Skills Shortage in AI Development

2.3. Navigating Ethical and Privacy Challenges in AI Applications

2.4. AI Regulatory Challenges

3. Conclusion:

References

- Athanasopoulou, K.; Daneva, G.N.; Adamopoulos, P.G.; Scorilas, A. Artificial Intelligence: The Milestone in Modern Biomedical Research. BioMedInformatics 2022, 2, 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, G.; Mendez, A.; Assi, E.B.; Zhao, B.; Sawan, M. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Review and Prediction Case Studies. Engineering 2020, 6, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskinbora, K.H. Medical ethics considerations on artificial intelligence. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 64, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomonoff, R. The time scale of artificial intelligence: Reflections on social effects. Hum. Syst. Manag. 1985, 5, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Krupinski, E.A.; Cai, J. Artificial intelligence will soon change the landscape of medical physics research and practice. Med Phys. 2018, 45, 1791–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajpurkar, P.; Chen, E.; Banerjee, O.; Topol, E.J. AI in health and medicine. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiens, J.; Saria, S.; Sendak, M.; Ghassemi, M.; Liu, V.X.; Doshi-Velez, F.; Jung, K.; Heller, K.; Kale, D.; Saeed, M.; et al. Do no harm: a roadmap for responsible machine learning for health care. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1337–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanagasingam, Y.; Xiao, D.; Vignarajan, J.; Preetham, A.; Tay-Kearney, M.-L.; Mehrotra, A. Evaluation of Artificial Intelligence–Based Grading of Diabetic Retinopathy in Primary Care. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e182665–e182665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beede, E.; Baylor, E.; Hersch, F.; Iurchenko, A.; Wilcox, L.; Ruamviboonsuk, P.; Vardoulakis, L.M. “A human-centered evaluation of a deep learning system deployed in clinics for the detection of diabetic retinopathy,” in Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 2020, pp. 1-12.

- Kiani, A.; Uyumazturk, B.; Rajpurkar, P.; Wang, A.; Gao, R.; Jones, E.; Yu, Y.; Langlotz, C.P.; Ball, R.L.; Montine, T.J.; et al. Impact of a deep learning assistant on the histopathologic classification of liver cancer. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, M.L.; Costa, L.S.d.L.; Cunha, V.A.; Kreniski, V.; Filho, M.d.O.B.; da Cunha, N.B.; Costa, F.F. Artificial intelligence and the future of life sciences. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 2515–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Hamet and J. Tremblay, “Artificial intelligence in medicine,” Metabolism, vol. 69, pp. S36-S40, 2017.

- Bhardwaj, A.; Kishore, S.; Pandey, D.K. Artificial Intelligence in Biological Sciences. Life 2022, 12, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulsen, T.; Jamuar, S.S.; Moody, A.R.; Karnes, J.H.; Varga, O.; Hedensted, S.; Spreafico, R.; Hafler, D.A.; McKinney, E.F. From Big Data to Precision Medicine. Front. Med. 2019, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. Hulsen, “Literature analysis of artificial intelligence in biomedicine,” Annals of translational medicine, vol. 10, no. 23, 2022.

- Tolstikov, V.; Moser, A.J.; Sarangarajan, R.; Narain, N.R.; Kiebish, M.A. Current Status of Metabolomic Biomarker Discovery: Impact of Study Design and Demographic Characteristics. Metabolites 2020, 10, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, N. The race to the top among the world’s leaders in artificial intelligence. Nature 2020, 588, S102–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, V.; Enslin, S.; Gross, S.A. History of artificial intelligence in medicine. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 92, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haick, H.; Tang, N. Artificial Intelligence in Medical Sensors for Clinical Decisions. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 3557–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Y. R. Shrestha, V. Y. R. Shrestha, V. Krishna, and G. von Krogh, “Augmenting organizational decision-making with deep learning algorithms: Principles, promises, and challenges,” Journal of Business Research, vol. 123, pp. 588-603, 2021.

- Willemink, M.J.; Koszek, W.A.; Hardell, C.; Wu, J.; Fleischmann, D.; Harvey, H.; Folio, L.R.; Summers, R.M.; Rubin, D.L.; Lungren, M.P. Preparing Medical Imaging Data for Machine Learning. Radiology 2020, 295, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, S.; Lin, A.L.; Brajer, N.; Sperling, J.; Ratliff, W.; Bedoya, A.D.; Balu, S.; O'Brien, C.; Sendak, M.P. Integrating a Machine Learning System Into Clinical Workflows: Qualitative Study. J. Med Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, G.; Tavares, J.M.R.S. Versatile Convolutional Networks Applied to Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Image Segmentation. J. Med Syst. 2021, 45, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abnet, C.C.; Arnold, M.; Wei, W.-Q. Epidemiology of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Nguyen, H.; Smith, C.; Chen, T.; Byrne, M.; Archibald-Heeren, B.; Rijken, J.; Aland, T. Clinical assessment of a novel machine-learning automated contouring tool for radiotherapy planning. J. Appl. Clin. Med Phys. 2023, 24, e13949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeadally, S.; Bello, O. Harnessing the power of Internet of Things based connectivity to improve healthcare. Internet Things 2019, 14, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lado-Baleato, M. Matabuena, C. Díaz-Louzao, and F. A: Gude, “Optimal Cut-Point Estimation for functional digital biomarkers: Application to Continuous Glucose Monitoring; arXiv:2404.09716, 2024.

- Mansour, M.; Darweesh, M.S.; Soltan, A. Wearable devices for glucose monitoring: A review of state-of-the-art technologies and emerging trends. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 89, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yao, C.; Huang, S.; Zheng, S.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, H.-J.; Xie, X. Technological Advances of Wearable Device for Continuous Monitoring of In Vivo Glucose. ACS Sensors 2024, 9, 1065–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. F. Ahmed, M. S. B. S. F. Ahmed, M. S. B. Alam, S. Afrin, S. J. Rafa, N. Rafa, and A. H. Gandomi, “Insights into Internet of Medical Things (IoMT): Data fusion, security issues and potential solutions,” Information Fusion, vol. 102, p. 102060, 2024.

- Tang, X. The role of artificial intelligence in medical imaging research. BJR|Open 2020, 2, 20190031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manco, L.; Maffei, N.; Strolin, S.; Vichi, S.; Bottazzi, L.; Strigari, L. Basic of machine learning and deep learning in imaging for medical physicists. Phys. Medica 2021, 83, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Padhy, S.K.; Takkar, B.; Chawla, R. Artificial intelligence in diabetic retinopathy: A natural step to the future. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 67, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristou, I.; Bosanquet, N. Improving the prevention and diagnosis of melanoma on a national scale: A comparative study of performance in the United Kingdom and Australia. J. Public Heal. Policy 2019, 41, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, J.L.; Dong, L.T. Artificial Intelligence Tools for Refining Lung Cancer Screening. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, H.; She, C.; Feng, J.; Liu, X.; Hu, X.; Chen, L.; Tao, Y. Artificial intelligence promotes the diagnosis and screening of diabetic retinopathy. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 946915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, S.; Balaji, J.N.; Joshi, A.; Surapaneni, K.M. Ethical Conundrums in the Application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Healthcare—A Scoping Review of Reviews. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nia, N.G.; Kaplanoglu, E.; Nasab, A. Evaluation of artificial intelligence techniques in disease diagnosis and prediction. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2023, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Horwitz, M.M.; Zhou, L.; Toh, S. Using Machine Learning to Identify Health Outcomes from Electronic Health Record Data. Curr. Epidemiology Rep. 2018, 5, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Dash, S. K. S. Dash, S. K. Shakyawar, M. Sharma, and S. Kaushik, “Big data in healthcare: management, analysis and future prospects,” Journal of big data, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1-25, 2019.

- Ozonoff, A.; E Milliren, C.; Fournier, K.; Welcher, J.; Landschaft, A.; Samnaliev, M.; Saluvan, M.; Waltzman, M.; A Kimia, A. Electronic surveillance of patient safety events using natural language processing. Heal. Informatics J. 2022, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Calster, B.; Wynants, L.; Timmerman, D.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Collins, G.S. Predictive analytics in health care: how can we know it works? J. Am. Med Informatics Assoc. 2019, 26, 1651–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidegger, T.; Speidel, S.; Stoyanov, D.; Satava, R.M. Robot-Assisted Minimally Invasive Surgery—Surgical Robotics in the Data Age. Proc. IEEE 2022, 110, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. S. Lee et al., “Robotic-Assisted Spine Surgery: Role in Training the Next Generation of Spine Surgeons,” Neurospine, vol. 21, no. 1, p. 116, 2024.

- Chen, Z.-L.; Du, Q.-L.; Zhu, Y.-B.; Wang, H.-F. A systematic review and meta-analysis of short-term outcomes comparing the efficacy of robotic versus laparoscopic colorectal surgery in obese patients. J. Robot. Surg. 2024, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, H.-C.; Marian, L.; Li, C.-C.; Juan, Y.-S.; Tung, M.-C.; Shih, H.-J.; Chang, C.-P.; Chen, J.-T.; Yang, C.-H.; Ou, Y.-C. Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy by the Hugo Robotic-Assisted Surgery (RAS) System and the da Vinci System: A Comparison between the Two Platforms. Cancers 2024, 16, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Z. Li et al., “Design and application of multi-dimensional force/torque sensors in surgical robots: A review,” IEEE Sensors Journal, 2023.

- Hou, C.; Wang, K.; Wang, F.; Li, H.; Lou, L.; Zhang, S.; Gu, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, T.; Sun, L. A Highly Integrated 3D MEMS Force Sensing Module With Variable Sensitivity for Robotic-Assisted Minimally Invasive Surgery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, H.; Beaman, C.; Morales, J.; Kimball, D.; Kaneko, N.; Tateshima, S. Full robotic endovascular treatment for various head and neck hemorrhagic lesions. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachan, S.; Swarnkar, P. Intelligent Fractional Order Sliding Mode Based Control for Surgical Robot Manipulator. Electronics 2023, 12, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wu, Z.; Chen, J.; Gao, A.; Chen, X.; Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Yang, G.; Lo, B.P.L.; Yang, G.-Z. Automatic Microsurgical Skill Assessment Based on Cross-Domain Transfer Learning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 4148–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funke, I.; Mees, S.T.; Weitz, J.; Speidel, S. Video-based surgical skill assessment using 3D convolutional neural networks. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2019, 14, 1217–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Fey, A.M. Deep learning with convolutional neural network for objective skill evaluation in robot-assisted surgery. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2018, 13, 1959–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zia and, I. Essa, “Automated surgical skill assessment in RMIS training,” International journal of computer assisted radiology and surgery, vol. 13, pp. 731-739, 2018.

- Fard, M.J.; Ameri, S.; Ellis, R.D.; Chinnam, R.B.; Pandya, A.K.; Klein, M.D. Automated robot-assisted surgical skill evaluation: Predictive analytics approach. Int. J. Med Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawaz, H.I.; Forestier, G.; Weber, J.; Idoumghar, L.; Muller, P.-A. Accurate and interpretable evaluation of surgical skills from kinematic data using fully convolutional neural networks. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2019, 14, 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fard, M.J.; Ameri, S.; Chinnam, R.B.; Ellis, R.D. Soft Boundary Approach for Unsupervised Gesture Segmentation in Robotic-Assisted Surgery. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2016, 2, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, A.; Zhang, C.; Xiong, X.; Jarc, A.M. Temporal clustering of surgical activities in robot-assisted surgery. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2017, 12, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Krishnan et al., “Transition state clustering: Unsupervised surgical trajectory segmentation for robot learning,” The International journal of robotics research, vol. 36, no. 13-14, pp. 1595-1618, 2017.

- Despinoy, F.; Bouget, D.; Forestier, G.; Penet, C.; Zemiti, N.; Poignet, P.; Jannin, P. Unsupervised Trajectory Segmentation for Surgical Gesture Recognition in Robotic Training. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 63, 1280–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, T.; Zimmerer, D.; Vemuri, A.; Isensee, F.; Wiesenfarth, M.; Bodenstedt, S.; Both, F.; Kessler, P.; Wagner, M.; Müller, B.; et al. Exploiting the potential of unlabeled endoscopic video data with self-supervised learning. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2018, 13, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.; Atputharuban, D.A.; Ramesh, R.; Ren, H. Real-Time Instrument Segmentation in Robotic Surgery Using Auxiliary Supervised Deep Adversarial Learning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 2188–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpani, A.; Lea, C.; Chen, C.C.G.; Hager, G.D. System events: readily accessible features for surgical phase detection. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2016, 11, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Waterman, R.S.; Urman, R.D.; Gabriel, R.A. A Machine Learning Approach to Predicting Case Duration for Robot-Assisted Surgery. J. Med Syst. 2019, 43, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. A. Younis et al., “A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Artificial Intelligence Tools in Medicine and Healthcare: Applications, Considerations, Limitations, Motivation and Challenges,” Diagnostics, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 109, 2024.

- Bertolaccini, L.; Casiraghi, M.; Uslenghi, C.; Maiorca, S.; Spaggiari, L. Recent advances in lung cancer research: unravelling the future of treatment. Updat. Surg. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor, M.Z.M.; Said, A.H.; Man, M.C.; Yusof, M.Z. Patient's satisfaction towards healthcare services and its associated factors at the highest patient loads government primary care clinic in Pahang. . 2024, 79, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, J.; Allen, K.; Zucker, K.; Adusumilli, P.; Scarsbrook, A.; Hall, G.; Orsi, N.M.; Ravikumar, N. Artificial intelligence in ovarian cancer histopathology: a systematic review. npj Precis. Oncol. 2023, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, B.; Cossy-Gantner, A.; Germann, S.; Schwalbe, N.R. Artificial intelligence (AI) and global health: how can AI contribute to health in resource-poor settings? BMJ Glob. Heal. 2018, 3, e000798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noah, B.; Keller, M.S.; Mosadeghi, S.; Stein, L.; Johl, S.; Delshad, S.; Tashjian, V.C.; Lew, D.; Kwan, J.T.; Jusufagic, A.; et al. Impact of remote patient monitoring on clinical outcomes: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. npj Digit. Med. 2018, 1, 20172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffery, L.A.; Muurlink, O.T.; Taylor-Robinson, A.W. Survival of rural telehealth services post-pandemic in Australia: A call to retain the gains in the ‘new normal’. Aust. J. Rural. Heal. 2022, 30, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, G.; Guizani, N.; Du, X. Efficient and Traceable Patient Health Data Search System for Hospital Management in Smart Cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 6425–6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattamisra, S.K.; Banerjee, P.; Gupta, P.; Mayuren, J.; Patra, S.; Candasamy, M. Artificial Intelligence in Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Research. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2023, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, L.; Shukla, T.; Huang, X.; Ussery, D.W.; Wang, S. Machine Learning Methods in Drug Discovery. Molecules 2020, 25, 5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, W.P.; Barzilay, R. Critical assessment of AI in drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2021, 16, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hessler, G.; Baringhaus, K.-H. Artificial Intelligence in Drug Design. Molecules 2018, 23, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.K.J.; Teo, C.B.; Tadeo, X.; Peng, S.; Soh, H.P.L.; Du, S.D.X.; Luo, V.W.Y.; Bandla, A.; Sundar, R.; Ho, D.; et al. Personalised, Rational, Efficacy-Driven Cancer Drug Dosing via an Artificial Intelligence SystEm (PRECISE): A Protocol for the PRECISE CURATE.AI Pilot Clinical Trial. Front. Digit. Heal. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, S. Artificial intelligence for drug discovery: Resources, methods, and applications. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2023, 31, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirajudeen, F.; Malhab, L.J.B.; Bustanji, Y.; Shahwan, M.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Semreen, M.H.; Taneera, J.; El-Huneidi, W.; Abu-Gharbieh, E. Exploring the Potential of Rosemary Derived Compounds (Rosmarinic and Carnosic Acids) as Cancer Therapeutics: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. Biomol. Ther. 2024, 32, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, F.; Klavon, E.; Liu, Z.; Lopez, R.P.; Zhao, X. A Systematic Review of Robotic Rehabilitation for Cognitive Training. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Asada et al., “Cognitive developmental robotics: A survey,” IEEE transactions on autonomous mental development, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 12-34, 2009.

- Kachouie, R.; Sedighadeli, S.; Khosla, R.; Chu, M.-T. Socially Assistive Robots in Elderly Care: A Mixed-Method Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2014, 30, 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denecke, K.; Baudoin, C.R. A Review of Artificial Intelligence and Robotics in Transformed Health Ecosystems. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 795957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyrkou, C.; Kolios, P.; Theocharides, T.; Polycarpou, M. Machine Learning for Emergency Management: A Survey and Future Outlook. Proc. IEEE 2022, 111, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, N.; Anjankar, A. Artificial Intelligence With Robotics in Healthcare: A Narrative Review of Its Viability in India. Cureus 2023, 15, e39416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. Ho et al., “Robot-assisted surgery compared with open surgery and laparoscopic surgery: clinical effectiveness and economic analyses,” 2013.

- C. R. Piccininni, “Cost-Effectiveness of Robotics and Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: Focus on Robot-Assisted Prostatectomy,” University of Western Ontario Medical Journal, vol. 87, no. 2, pp. 49-51, 2018.

- Ahmed, K.; Ibrahim, A.; Wang, T.T.; Khan, N.; Challacombe, B.; Khan, M.S.; Dasgupta, P. Assessing the cost effectiveness of robotics in urological surgery – a systematic review. BJU Int. 2012, 110, 1544–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, M.; Wu, P.; Wu, S.; Lee, T.-Y.; Bai, C. Application of Computational Biology and Artificial Intelligence in Drug Design. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carracedo-Reboredo, P.; Liñares-Blanco, J.; Rodríguez-Fernández, N.; Cedrón, F.; Novoa, F.J.; Carballal, A.; Maojo, V.; Pazos, A.; Fernandez-Lozano, C. A review on machine learning approaches and trends in drug discovery. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 4538–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Batool, B. M. Batool, B. Ahmad, and S. Choi, “A structure-based drug discovery paradigm,” International journal of molecular sciences, vol. 20, no. 11, p. 2783, 2019.

- Basile, A.O.; Yahi, A.; Tatonetti, N.P. Artificial Intelligence for Drug Toxicity and Safety. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 40, 624–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, S.; Mao, H.; Al-Nima, R.R.O.; Woo, W.L. Explainable AI Evaluation: A Top-Down Approach for Selecting Optimal Explanations for Black Box Models. Information 2023, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isgut, M.; Gloster, L.; Choi, K.; Venugopalan, J.; Wang, M.D. Systematic Review of Advanced AI Methods for Improving Healthcare Data Quality in Post COVID-19 Era. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 16, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.C.; Islam, S.U.; Noor, A.; Khan, S.; Afsar, W.; Nazir, S. Influential Usage of Big Data and Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, R.; Bustin, S.; Huggett, J.; Mason, D. Improving the standardization of mRNA measurement by RT-qPCR. Biomol. Detect. Quantif. 2018, 15, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Rahman, M.; Taher, A.; Quaosar, G.M.A.A.; Uddin, A. Using artificial intelligence for hiring talents in a moderated mechanism. Futur. Bus. J. 2024, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya, J.; Holweg, M. Using algorithms to improve knowledge work. J. Oper. Manag. 2024, 70, 482–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bužančić, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Clinical decision-making in benzodiazepine deprescribing by healthcare providers vs. AI-assisted approach,” British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 90, no. 3, pp. 662-674, 2024.

- Pruski, M. AI-Enhanced Healthcare: Not a new Paradigm for Informed Consent. J. Bioethical Inq. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Huang, S.; Tang, W. AI triage or manual triage? Exploring medical staffs’ preference for AI triage in China. Patient Educ. Couns. 2024, 119, 108076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. 10 2317, 2024.

- Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Ma, R.; Zhang, M. Justice at the Forefront: Cultivating felt accountability towards Artificial Intelligence among healthcare professionals. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 347, 116717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkimsetti, M.; Devella, S.G.; Patel, K.B.; Dhandibhotla, S.; Kaur, J.; Mathew, M.; Kataria, J.; Nallani, M.; E Farwa, U.; Patel, T.; et al. Optimizing the Clinical Direction of Artificial Intelligence With Health Policy: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Cureus 2024, 16, e58400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Pesapane and P. Summers, “Ethics and regulations for AI in radiology,” in Artificial Intelligence for Medicine: Elsevier, 2024, pp. 179-192.

- N. Ferruz et al., “Anniversary AI reflections,” Nature Machine Intelligence, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 6-12, 2024.

- M. M. Soliman, E. M. M. Soliman, E. Ahmed, A. Darwish, and A. E. Hassanien, “Artificial intelligence powered Metaverse: analysis, challenges and future perspectives,” Artificial Intelligence Review, vol. 57, no. 2, p. 36, 2024.

- N. Singh, M. N. Singh, M. Jain, M. M. Kamal, R. Bodhi, and B. Gupta, “Technological paradoxes and artificial intelligence implementation in healthcare. An application of paradox theory,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 198, p. 122967, 2024.

- Palaniappan, K.; Lin, E.Y.T.; Vogel, S. Global Regulatory Frameworks for the Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the Healthcare Services Sector. Healthcare 2024, 12, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habbal, A.; Ali, M.K.; Abuzaraida, M.A. Artificial Intelligence Trust, Risk and Security Management (AI TRiSM): Frameworks, applications, challenges and future research directions. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, G.B.; Dutta, P.K. Evaluating if Ghana's Health Institutions and Facilities Act 2011 (Act 829) Sufficiently Addresses Medical Negligence Risks from Integration of Artificial Intelligence Systems. Mesopotamian J. Artif. Intell. Heal. 2024, 2024, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Esmaeilzadeh, P. Generative AI in Medical Practice: In-Depth Exploration of Privacy and Security Challenges. J. Med Internet Res. 2024, 26, e53008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malgieri, G.; Pasquale, F. Licensing high-risk artificial intelligence: Toward ex ante justification for a disruptive technology. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2024, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. House, Blueprint for an ai bill of rights: Making automated systems work for the american people. Nimble Books, 2022.

- Beccia, F.; Di Marcantonio, M.; Causio, F.A.; Schleicher, L.; Wang, L.; Cadeddu, C.; Ricciardi, W.; Boccia, S. Integrating China in the International Consortium for Personalised Medicine: a position paper on innovation and digitalization in Personalized Medicine. BMC Public Heal. 2024, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Du, H. Research on the identification and evolution of health industry policy instruments in China. Front. Public Heal. 2024, 12, 1264827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Jevnikar, A.M.; Desjardins, E. Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, and Regulation of Immunity: Challenges and Opportunities. Arch. Immunol. et Ther. Exp. 2024, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).