Submitted:

10 July 2024

Posted:

11 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

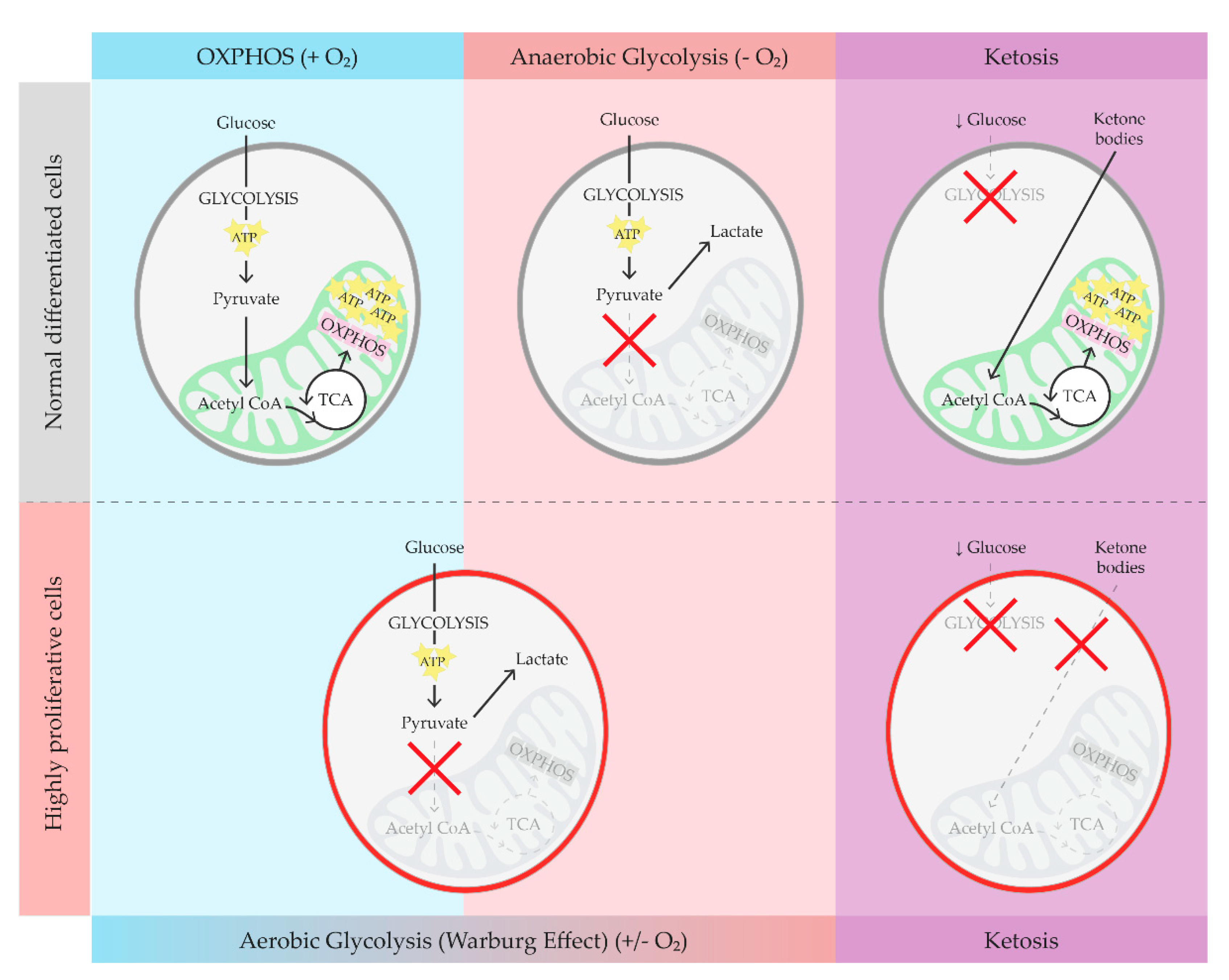

2. Brief Overview on Glucose Metabolism, Warburg Effect, and Ketosis

3. Ketosis in ADPKD Animal Models

4. Ketosis in ADPKD Patients

5. Ketosis in ADPKD Patients: RCTs

6. Kidney Disease, Ketosis, and Microbiota

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cordido A, Besada-Cerecedo L, García-González MA. The Genetic and Cellular Basis of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease—A Primer for Clinicians. Front Pediatr. 2017;5. doi:10.3389/fped.2017.00279. [CrossRef]

- Willey CJ, Blais JD, Hall AK, Krasa HB, Makin AJ, Czerwiec FS. Prevalence of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in the European Union. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2017;32(8):1356-1363. [CrossRef]

- Solazzo A, Testa F, Giovanella S, et al. The prevalence of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): A meta-analysis of European literature and prevalence evaluation in the Italian province of Modena suggest that ADPKD is a rare and underdiagnosed condition. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190430. [CrossRef]

- Cornec-Le Gall E, Alam A, Perrone RD. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. The Lancet. 2019;393(10174):919-935. [CrossRef]

- Magistroni R, Boletta A. Defective glycolysis and the use of 2-deoxy-d-glucose in polycystic kidney disease: from animal models to humans. J Nephrol. 2017;30(4):511-519. [CrossRef]

- Astley ME, Boenink R, Abd ElHafeez S, et al. The ERA Registry Annual Report 2020: a summary. Clin Kidney J. 2023;16(8):1330-1354. [CrossRef]

- Torres Vicente E., Chapman Arlene B., Devuyst Olivier, et al. Tolvaptan in Patients with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(25):2407-2418. [CrossRef]

- Gansevoort RT, Arici M, Benzing T, et al. Recommendations for the use of tolvaptan in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a position statement on behalf of the ERA-EDTA Working Groups on Inherited Kidney Disorders and European Renal Best Practice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(3):337-348. [CrossRef]

- Padovano V, Podrini C, Boletta A, Caplan MJ. Metabolism and mitochondria in polycystic kidney disease research and therapy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(11):678-687. [CrossRef]

- Rowe I, Boletta A. Defective metabolism in polycystic kidney disease: potential for therapy and open questions. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2014;29(8):1480-1486. [CrossRef]

- Schiliro C, Firestein BL. Mechanisms of Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer Cells Supporting Enhanced Growth and Proliferation. Cells. 2021;10(5):1056. [CrossRef]

- Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg Effect: The Metabolic Requirements of Cell Proliferation. Science. 2009;324(5930):1029-1033. [CrossRef]

- 13. Kang M, Kang JH, Sim IA, et al. Glucose Deprivation Induces Cancer Cell Death through Failure of ROS Regulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023;24(15):11969. [CrossRef]

- Dhillon KK, Gupta S. Biochemistry, Ketogenesis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493179/ (accessed on 2 April, 2024).

- Judge A, Dodd MS. Metabolism. Essays in Biochemistry. 2020;64(4):607-647. [CrossRef]

- Masood W, Annamaraju P, Khan Suheb MZ, Uppaluri KR. Ketogenic Diet. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499830/ (accessed on 2 April, 2024).

- deCampo DM, Kossoff EH. Ketogenic dietary therapies for epilepsy and beyond. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care. 2019;22(4):264. [CrossRef]

- Galali Y, Zebari SMS, Aj. Jabbar A, Hashm Balaky H, Sadee BA, Hassanzadeh H. The impact of ketogenic diet on some metabolic and non-metabolic diseases: Evidence from human and animal model experiments. Food Sci Nutr. 2024;12(3):1444-1464. [CrossRef]

- Caprio M, Infante M, Moriconi E, et al. Very-low-calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD) in the management of metabolic diseases: systematic review and consensus statement from the Italian Society of Endocrinology (SIE). J Endocrinol Invest. 2019;42(11):1365-1386. [CrossRef]

- Testa F, Marchiò M, Belli M, et al. A pilot study to evaluate tolerability and safety of a modified Atkins diet in ADPKD patients. PharmaNutrition. 2019;9:100154. [CrossRef]

- Warner G, Hein KZ, Nin V, et al. Food Restriction Ameliorates the Development of Polycystic Kidney Disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2016;27(5):1437. [CrossRef]

- Kipp KR, Rezaei M, Lin L, Dewey EC, Weimbs T. A mild reduction of food intake slows disease progression in an orthologous mouse model of polycystic kidney disease. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2016;310(8):F726-F731. [CrossRef]

- Torres JA, Kruger SL, Broderick C, et al. Ketosis Ameliorates Renal Cyst Growth in Polycystic Kidney Disease. Cell Metabolism. 2019;30(6):1007-1023.e5. [CrossRef]

- Shillingford JM, Piontek KB, Germino GG, Weimbs T. Rapamycin ameliorates PKD resulting from conditional inactivation of Pkd1. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(3):489-497. [CrossRef]

- Weimbs T, Shillingford JM, Torres J, Kruger SL, Bourgeois BC. Emerging targeted strategies for the treatment of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J. 2018;11(Suppl 1):i27-i38. [CrossRef]

- Torres JA, Holznecht N, Asplund DA, et al. A combination of β-hydroxybutyrate and citrate ameliorates disease progression in a rat model of polycystic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2024;326(3):F352-F368. [CrossRef]

- Hopp K, Catenacci VA, Dwivedi N, et al. Weight loss and cystic disease progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. iScience. 2022;25(1):103697. [CrossRef]

- Strubl S, Oehm S, Torres JA, et al. Ketogenic dietary interventions in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease—a retrospective case series study: first insights into feasibility, safety and effects. Clinical Kidney Journal. 2022;15(6):1079-1092. [CrossRef]

- Nowak KL, You Z, Gitomer B, et al. Overweight and Obesity Are Predictors of Progression in Early Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(2):571-578. [CrossRef]

- Nowak KL, Moretti F, Bussola N, et al. Visceral Adiposity and Progression of ADPKD: A Cohort Study of Patients From the TEMPO 3:4 Trial. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. Published online April 10, 2024. 10 April. [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Comparison of High vs. Normal/Low Protein Diets on Renal Function in Subjects without Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97656. [CrossRef]

- Capelli I, Lerario S, Aiello V, et al. Diet and Physical Activity in Adult Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: A Review of the Literature. Nutrients. 2023;15(11):2621. [CrossRef]

- Ikizler TA, Burrowes JD, Byham-Gray LD, et al. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Nutrition in CKD: 2020 Update. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2020;76(3):S1-S107. [CrossRef]

- Acharya P, Acharya C, Thongprayoon C, et al. Incidence and Characteristics of Kidney Stones in Patients on Ketogenic Diet: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diseases. 2021;9(2):39. [CrossRef]

- Dyńka D, Kowalcze K, Charuta A, Paziewska A. The Ketogenic Diet and Cardiovascular Diseases. Nutrients. 2023;15(15):3368. [CrossRef]

- Nasser S, Vialichka V, Biesiekierska M, Balcerczyk A, Pirola L. Effects of ketogenic diet and ketone bodies on the cardiovascular system: Concentration matters. World J Diabetes. 2020;11(12):584-595. [CrossRef]

- Pirola L, Ciesielski O, Balcerczyk A. Fat not so bad? The role of ketone bodies and ketogenic diet in the treatment of endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2022;206:115346. [CrossRef]

- Popiolek-Kalisz J. Ketogenic diet and cardiovascular risk – state of the art review. Current Problems in Cardiology. 2024;49(3):102402. [CrossRef]

- Joo M, Moon S, Lee YS, Kim MG. Effects of very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diets on lipid profiles in normal-weight (body mass index <25 kg/m2) adults: a meta-analysis. Nutrition Reviews. 2023;81(11):1393-1401. [CrossRef]

- Bruen DM, Kingaard JJ, Munits M, et al. Ren.Nu, a Dietary Program for Individuals with Autosomal-Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease Implementing a Sustainable, Plant-Focused, Kidney-Safe, Ketogenic Approach with Avoidance of Renal Stressors. Kidney and Dialysis. 2022;2(2):183-203. [CrossRef]

- Oehm S, Steinke K, Schmidt J, et al. RESET-PKD: a pilot trial on short-term ketogenic interventions in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2023;38(7):1623-1635. [CrossRef]

- University of Colorado, Denver. Time Restricted Feeding in Overweight and Obese Adults With Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. clinicaltrials.gov; 2023. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04534985 (accessed on 1 January, 2024).

- Cukoski S, Lindemann CH, Arjune S, et al. Feasibility and impact of ketogenic dietary interventions in polycystic kidney disease: KETO-ADPKD—a randomized controlled trial. Cell Reports Medicine. 2023;4(11):101283. [CrossRef]

- Testa F, Marchiò M, D’Amico R, et al. GREASE II. A phase II randomized, 12-month, parallel-group, superiority study to evaluate the efficacy of a Modified Atkins Diet in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease patients. PharmaNutrition. 2020;13:100206. [CrossRef]

- University of Colorado, Denver. Daily Caloric Restriction in Overweight and Obese Adults With ADPKD. clinicaltrials.gov; 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04907799 (accessed on 1 January, 2024).

- Ohio State University. Feasibility and Efficacy of a Well-Formulated Ketogenic Diet in Delaying Progression of Polycystic Kidney Disease in Patients at Risk for Rapid Progression. clinicaltrials.gov; 2024. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06325644 (accessed on 1 January, 2024).

- 8-hour time-restricted eating linked to a 91% higher risk of cardiovascular death. American Heart Association. Accessed May 20, 2024. Available online: http://newsroom.heart.org/news/8-hour-time-restricted-eating-linked-to-a-91-higher-risk-of-cardiovascular-death (accessed on 2 April, 2024).

- Mosterd CM, Kanbay M, Van Den Born BJH, Van Raalte DH, Rampanelli E. Intestinal microbiota and diabetic kidney diseases: the Role of microbiota and derived metabolites inmodulation of renal inflammation and disease progression. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2021;35(3):101484. [CrossRef]

- Ma L, Zhang L, Li J, et al. The potential mechanism of gut microbiota-microbial metabolites-mitochondrial axis in progression of diabetic kidney disease. Molecular Medicine. 2023;29(1):148. [CrossRef]

- David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559-563. [CrossRef]

- Vasileva VY, Sultanova RF, Sudarikova AV, Ilatovskaya DV. Insights Into the Molecular Mechanisms of Polycystic Kidney Diseases. Front Physiol. 2021;12:693130. [CrossRef]

- Cao C, Zhu H, Yao Y, Zeng R. Gut Dysbiosis and Kidney Diseases. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:829349. [CrossRef]

- Li N, Wang Y, Wei P, et al. Causal Effects of Specific Gut Microbiota on Chronic Kidney Diseases and Renal Function—A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Nutrients. 2023;15(2):360. [CrossRef]

- Rukavina Mikusic NL, Kouyoumdzian NM, Choi MR. Gut microbiota and chronic kidney disease: evidences and mechanisms that mediate a new communication in the gastrointestinal-renal axis. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2020;472(3):303-320. [CrossRef]

- Caldarelli M, Franza L, Rio P, Gasbarrini A, Gambassi G, Cianci R. Gut–Kidney–Heart: A Novel Trilogy. Biomedicines. 2023;11(11):3063. [CrossRef]

- Evenepoel P, Poesen R, Meijers B. The gut–kidney axis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32(11):2005-2014. [CrossRef]

- Hou K, Wu ZX, Chen XY, et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):1-28. [CrossRef]

- Lambert K, Rinninella E, Biruete A, et al. Targeting the Gut Microbiota in Kidney Disease: The Future in Renal Nutrition and Metabolism. Journal of Renal Nutrition. 2023;33(6):S30-S39. [CrossRef]

- Yacoub R, Nadkarni GN, McSkimming DI, et al. Fecal microbiota analysis of polycystic kidney disease patients according to renal function: A pilot study. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2019;244(6):505-513. [CrossRef]

- Wang F, Jiang H, Shi K, Ren Y, Zhang P, Cheng S. Gut bacterial translocation is associated with microinflammation in end-stage renal disease patients. Nephrology (Carlton). 2012;17(8):733-738. [CrossRef]

- Wong J, Piceno YM, DeSantis TZ, Pahl M, Andersen GL, Vaziri ND. Expansion of urease- and uricase-containing, indole- and p-cresol-forming and contraction of short chain fatty acid-producing intestinal microbiota in ESRD. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39(3):230-237. [CrossRef]

- Strubl S, Woestmann F, Todorova P, et al. #395 Gut dysbiosis in ADPKD patients: a controlled pilot study. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2024;39(Supplement_1):gfae069-0255-0395. [CrossRef]

- Rinninella E, Cintoni M, Raoul P, et al. Food Components and Dietary Habits: Keys for a Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2393. [CrossRef]

- Walker AW, Ince J, Duncan SH, et al. Dominant and diet-responsive groups of bacteria within the human colonic microbiota. The ISME Journal. 2011;5(2):220-230. [CrossRef]

- Kern L, Kviatcovsky D, He Y, Elinav E. Impact of caloric restriction on the gut microbiota. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2023;73:102287. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Chen X, Loh YJ, Yang X, Zhang C. The effect of calorie intake, fasting, and dietary composition on metabolic health and gut microbiota in mice. BMC Biology. 2021;19(1):51. [CrossRef]

- Popa AD, Niță O, Gherasim A, et al. A Scoping Review of the Relationship between Intermittent Fasting and the Human Gut Microbiota: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Nutrients. 2023;15(9):2095. [CrossRef]

- Tagliabue A, Ferraris C, Uggeri F, et al. Short-term impact of a classical ketogenic diet on gut microbiota in GLUT1 Deficiency Syndrome: A 3-month prospective observational study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2017;17:33-37. [CrossRef]

- Lindefeldt M, Eng A, Darban H, et al. The ketogenic diet influences taxonomic and functional composition of the gut microbiota in children with severe epilepsy. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2019;5(1):5. [CrossRef]

- Xie G, Zhou Q, Qiu CZ, et al. Ketogenic diet poses a significant effect on imbalanced gut microbiota in infants with refractory epilepsy. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(33):6164-6171. [CrossRef]

- Linsalata M, Russo F, Riezzo G, et al. The Effects of a Very-Low-Calorie Ketogenic Diet on the Intestinal Barrier Integrity and Function in Patients with Obesity: A Pilot Study. Nutrients. 2023;15(11):2561. [CrossRef]

- Attaye I, van Oppenraaij S, Warmbrunn MV, Nieuwdorp M. The Role of the Gut Microbiota on the Beneficial Effects of Ketogenic Diets. Nutrients. 2021;14(1):191. [CrossRef]

| KDI | DESCRIPTION | MAIN COMPOSITION | RESEARCH FOCUS | NOTE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCR | Reducing energy intake through DCR while maintaining nutritional adequacy. | Reduced overall calorie intake, balanced macronutrients. | Weight loss, metabolic health. | Requires consistent daily caloric reduction, can be challenging to maintain long-term. |

| IMF | Alternating periods of fasting and eating, aimed at inducing ketosis during fasting periods. | Varied depending on fasting schedule, generally low carbohydrate during eating periods. | Weight loss, metabolic health, improved insulin sensitivity. | Different fasting schedules (e.g., 16/8, 5:2) can be used. |

| TRF | Eating all daily calories within a specific time window each day to promote ketosis during fasting periods. | Low carbohydrate during eating window, balanced macronutrients. | Weight loss, metabolic health, improved circadian rhythm. | Typical windows are 8-12 hours; requires consistency in eating times. |

| cKD | Traditional ketogenic diet with a strict ratio (typically 4:1) of fats to combined carbohydrates and proteins. | High fat (about 90%), low carbohydrate, moderate protein. | Refractory epilepsy, some metabolic disorders. | Requires the use of specifically calculated recipes measured in grams to meet the patient’s needs. |

| MCT | Uses medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) to enhance ketosis with greater carbohydrate tolerance. | Moderate fat including MCTs, more carbohydrates than cKD. | Refractory epilepsy, some metabolic disorders. | As cKD, requires the use of specifically calculated recipes measured in grams. Allows for greater food variety compared to cKD. |

| MAD | Low carbohydrate, high fat diet, less restrictive than cKD and MCT. | High fat, limited carbohydrates (about 20g per day), moderate protein. | Refractory epilepsy, migraine, weight loss (if low calorie). | Food can be measured using standard household measurements. |

| LGIT | Limits carbohydrates to those with a low glycaemic index to maintain stable blood glucose levels. | Low glycaemic index carbohydrates, moderate protein, moderate fats. | Refractory epilepsy, migraine, weight loss (if low calorie), blood glucose management. | Food can be measured using standard household measurements. |

| VLCKD | Very low-calorie diet primarily designed for weight loss while maintaining ketosis. | Very low in calories, low to moderate fat, low carbohydrate, moderate protein. | Weight loss, obesity. | Used under medical supervision, can have rapid weight loss effects but requires monitoring to avoid nutritional deficiencies. |

| Study name | Intervention | Study design | Duration (months) | Patients (n) | Bmi (kg/m^2) | Weight loss | Kidney outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Daily Caloric Restriction and Intermittent Fasting in Overweight and Obese Adults With Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease NCT03342742 (completed) |

DCR and IMF both with similar (~34%) targeted weekly energy deficit | Randomized, parallel assignment, 2 experimental arms, masked (Inv, OA) | 12 | 29 | 25 - 45 | Changes in BW | TKV (MRI) |

|

Time Restricted Feeding in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease NCT04534985 (completed) |

TRF (8-hr window) and normal healthy eating recommendations | Randomized, parallel assignment, 1 experimental arm, 1 control arm (healthy eating), masked (Inv, OA) | 12 | 29 | 25 - 45 | Changes in BW, abdominal adiposity (MRI), body composition (DEXA) | TKV (MRI) |

|

Ketogenic Dietary Interventions in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD) NCT04680780 (completed) |

KD (carbohydrate < 30 g/day, 0.8 g/kg BW protein intake) and 3-days WF | Randomized, parallel assignment, 2 experimental arms, 1 control arm (AL diet), no masking | 3 | 63 | 18.6 - 34.9 | Changes in BMI | TKV (MRI), serum creatinine, cystatin C |

|

Daily Caloric Restriction in Overweight and Obese Adults With ADPKD NCT04907799 (recruiting) |

DCR (30%) and increased physical activity | Randomized, parallel assignment, 1 experimental arm, 1 control arm (a single nutrition consultation), masked (Inv, OA) | 24 | 126 | 25 - 45 | Changes in BW, subcutaneous/visceral/total abdominal fat (MRI), % body fat in a sub-set of patients (DEXA) | TKV (MRI) |

|

GREASE II. A phase II randomized, 24-month, parallel-group, superiority study to evaluate the activity of a Modified Atkins Diet in ADPKD patients (recruiting) |

KD (MAD: < 20 g/day of carbohydrates) | Randomized, parallel assignment, 1 experimental arm, 1 control arm (balanced normocaloric diet), masked (Inv, OA) | 24 | 92 | 20 - 30 | BW stability, waist circumference, body composition (BIA), subcutaneous/visceral/total abdominal fat (MRI) | TKV (MRI), serum creatinine, cystatin C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).