Submitted:

09 July 2024

Posted:

11 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

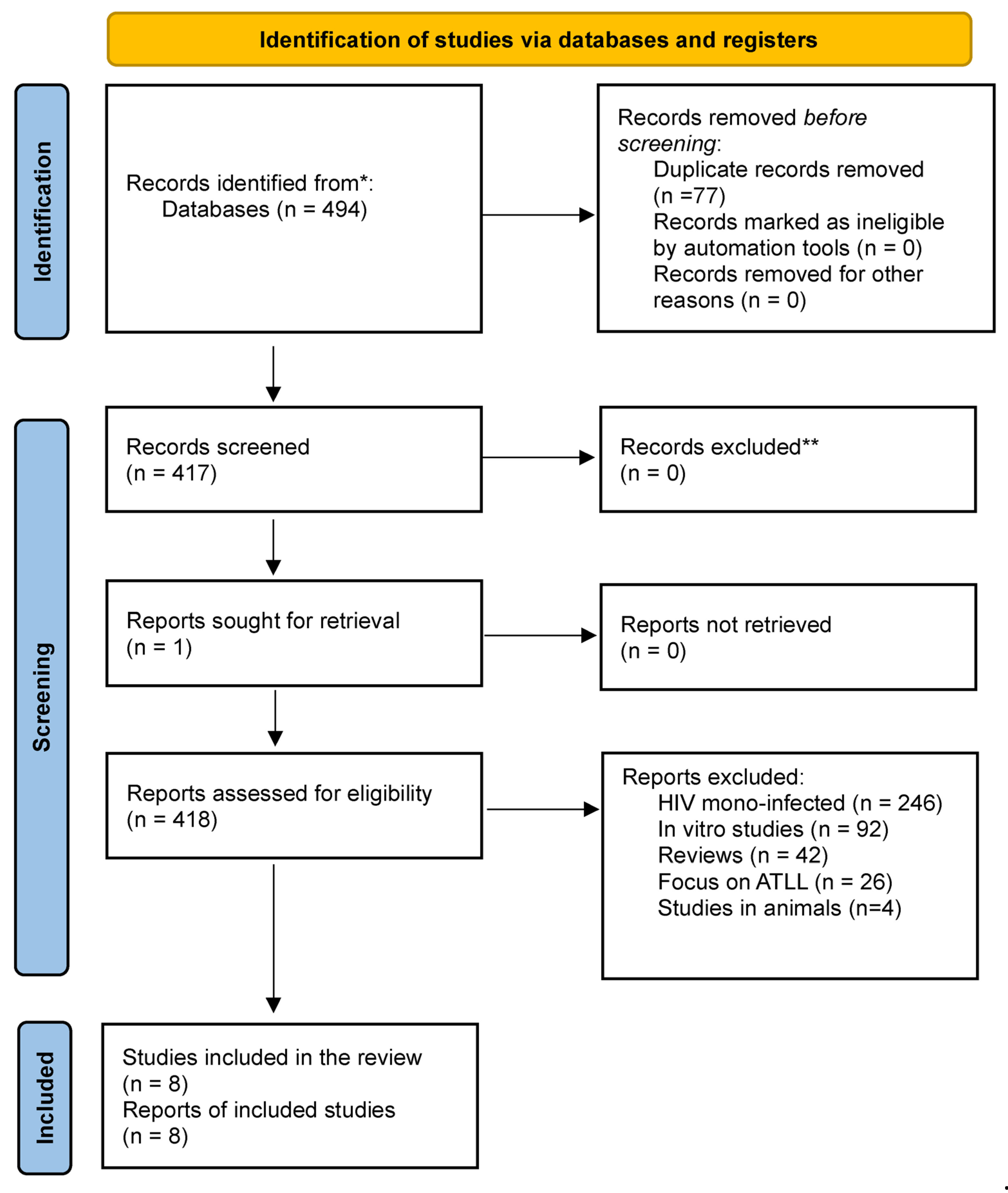

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Main Outcomes

2.5. Assessment of Risk of Bias in Included Studies

2.6. Selection of Studies

2.7. Data Extraction and Management

3. Results

3.1. Antiretroviral Therapy

3.2. Proviral Load

3.3. Immunological Outcomes

3.4. Clinical Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de-Mendoza C, Pérez L, Rando A, Reina G, Aguilera A, Benito R, et al. HTLV-1-associated myelopathy in Spain. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2023 Dec;169:105619. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gessain A, Cassar O. Epidemiological Aspects and World Distribution of HTLV-1 Infection. Front Microbiol. 2012;3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eusebio-Ponce E, Anguita E, Paulino-Ramirez R, Candel FJ. HTLV-1 infection: an emerging risk. Pathogenesis, epidemiology, diagnosis and associated diseases. Revista Española de Quimioterapia. 2019;32(6):485–95.

- Zane L, David Sibon, Franck Mortreux, Eric Wattel. Clonal expansion of HTLV-1 infected cells depends on the CD4 versus CD8 phenotype. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2009;Volume(14):3935.

- Beilke MA, Theall KP, Megan O, Clayton JL, Benjamin SM, Winsor EL, et al. Clinical Outcomes and Disease Progression among Patients Coinfected with HIV and Human T Lymphotropic Virus Types 1 and 2. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004 Jul 15;39(2):256–63. [CrossRef]

- Vandormael A, Rego F, Danaviah S, Carlos Junior Alcantara L, Boulware D, de Oliveira T. CD4+ T-cell Count may not be a Useful Strategy to Monitor Antiretroviral Therapy Response in HTLV-1/HIV Co-infected Patients. Curr HIV Res. 2017 Jul 3;15(3).

- Ticona E, Huaman MA., Yanque O, Zunt JR. HIV and HTLV-1 Coinfection: The Need to Initiate Antiretroviral Therapy. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC). 2013 Nov 12;12(6):373–4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaño-Castellón I, Marconi C, Saffe C, Brites C. Clinical and Laboratory Outcomes in HIV-1 and HTLV-1/2 Coinfection: A Systematic Review. Front Public Health. 2022 Mar 7;10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda MV, Bouzas MB, Remesar M, Fridman A, Remondegui C, Mammana L, et al. Relevance of HTLV-1 proviral load in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients living in endemic and non-endemic areas of Argentina. PLoS One. 2019 Nov 22;14(11).

- Akbarin MM, Rahimi H, Hassannia T, Shoja Razavi G, Sabet F, Shirdel A. Comparison of HTLV-I Proviral Load in Adult T Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma (ATL), HTLV-I-Associated Myelopathy (HAM-TSP) and Healthy Carriers. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2013 Mar;16(3):208–12.

- Olindo S, Lézin A, Cabre P, Merle H, Saint-Vil M, Edimonana Kaptue M, et al. HTLV-1 proviral load in peripheral blood mononuclear cells quantified in 100 HAM/TSP patients: A marker of disease progression. J Neurol Sci. 2005 Oct;237(1–2):53–9. [CrossRef]

- Taylor GP, Hall SE, Navarrete S, Michie CA, Davis R, Witkover AD, et al. Effect of Lamivudine on Human T-Cell Leukemia Virus Type 1 (HTLV-1) DNA Copy Number, T-Cell Phenotype, and Anti-Tax Cytotoxic T-Cell Frequency in Patients with HTLV-1-Associated Myelopathy. J Virol. 1999 Dec;73(12):10289–95. [CrossRef]

- Zehender G, Colasante C, Santambrogio S, De Maddalena C, Massetto B, Cavalli B, et al. Increased Risk of Developing Peripheral Neuropathy in Patients Coinfected With HIV-1 and HTLV-2. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002 Dec;31(4):440–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor GP, Goon P, Furukawa Y, Green H, Barfield A, Mosley A, et al. Zidovudine plus lamivudine in Human T-Lymphotropic Virus type-I-associated myelopathy: a randomised trial. Retrovirology. 2006 Dec 19;3.

- Beilke MA, Dorge VLT, Sirois M, Bhuiyan A, Murphy EL, Walls JM, et al. Relationship between Human T Lymphotropic Virus (HTLV) Type 1/2 Viral Burden and Clinical and Treatment Parameters among Patients with HIV Type 1 and HTLV-1/2 Coinfection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007 May 1;44(9):1229–34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macchi B, Balestrieri E, Ascolani A, Hilburn S, Martin F, Mastino A, et al. Susceptibility of Primary HTLV-1 Isolates from Patients with HTLV-1-Associated Myelopathy to Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors. Viruses. 2011 May 5;3(5):469–83. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevino A, Parra P, Bar-Magen T, Garrido C, de Mendoza C, Soriano V. Antiviral effect of raltegravir on HTLV-1 carriers. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2012 Jan 1;67(1):218–21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abad-Fernández M, Cabrera C, García E, Vallejo A. Transient increment of HTLV-2 proviral load in HIV-1-co-infected patients during treatment intensification with raltegravir. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2014;59(3):204–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enose-Akahata Y, Billioux BJ, Azodi S, Dwyer J, Vellucci A, Ngouth N, et al. Clinical trial of raltegravir, an integrase inhibitor, in HAM/TSP. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2021 Oct 25;8(10):1970–85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino-Merlo F, Balestrieri E, Matteucci C, Mastino A, Grelli S, Macchi B. Antiretroviral Therapy in HTLV-1 Infection: An Updated Overview. Pathogens. 2020 May 1;9(5):342. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan S, Amer S, Zervos M. Tropical spastic paraparesis treated with Combivir (lamivudine–zidovudine). Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2013 May;20(5):759–60. [CrossRef]

- Balestrieri E, Forte G, Matteucci C, Mastino A, Macchi B. Effect of Lamivudine on Transmission of Human T-Cell Lymphotropic Virus Type 1 to Adult Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells In Vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002 Sep;46(9):3080–3. [CrossRef]

- García-Lerma J, Nidtha S, Heneine W. Susceptibility of Human T Cell Leukemia Virus Type 1 to Reverse-Transcriptase Inhibitors: Evidence for Resistance to Lamivudine. J Infect Dis. 2001 Aug 15;184(4):507–10. [CrossRef]

- Hill SA, Lloyd PA, McDonald S, Wykoff J, Derse D. Susceptibility of Human T Cell Leukemia Virus Type I to Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors. J Infect Dis. 2003 Aug;188(3):424–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barski M, Minnell J, Maertens G. Inhibition of HTLV-1 Infection by HIV-1 First- and Second-Generation Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors. Front Microbiol. 2019 Aug 13;10.

- Seegulam M, Ratner L. Integrase Inhibitors Effective against Human T-Cell Leukemia Virus Type 1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011 May;55(5):2011–7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demontis M, Hilburn S, Taylor G. Human T Cell Lymphotropic Virus Type 1 Viral Load Variability and Long-Term Trends in Asymptomatic Carriers and in Patients with Human T Cell Lymphotropic Virus Type 1-Related Diseases. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013 Feb;29(2):359–64. [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki T, Nakagawa M, Nagai M, Usuku K, Higuchi I, Arimura K, et al. HTLV-I proviral load correlates with progression of motor disability in HAM/TSP: Analysis of 239 HAM/TSP patients including 64 patients followed up for 10 years. J Neurovirol. 2001 Jan;7(3):228–34. [CrossRef]

- Ferraz S, Costa G, Carneiro Neto J, Hebert T, de Oliveira C, Guerra M, et al. Neurologic, clinical, and immunologic features in a cohort of HTLV-1 carriers with high proviral loads. J Neurovirol. 2020 Aug;26(4):520–9. [CrossRef]

- Tarokhian H, Taghadosi M, Rafatpanah H, Rajaei T, Azarpazhooh MR, Valizadeh N, et al. The effect of HTLV-1 virulence factors (HBZ, Tax, proviral load), HLA class I and plasma neopterin on manifestation of HTLV-1 associated myelopathy tropical spastic paraparesis. Virus Res. 2017 Jan;228:1–6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saffari M, Rahimzada M, Mirhosseini A, Ghezaldasht SA, Valizadeh N, Moshfegh M, et al. Coevolution of HTLV-1-HBZ, Tax, and proviral load with host IRF-1 and CCNA-2 in HAM/TSP patients. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2022 Sep;103.

- Abad-Fernández M, Hernández-Walias FJ, Ruiz de León MJ, Vivancos MJ, Pérez-Elías MJ, Moreno A, et al. HTLV-2 Enhances CD8+ T Cell-Mediated HIV-1 Inhibition and Reduces HIV-1 Integrated Proviral Load in People Living with HIV-1. Viruses. 2022 Nov 9;14(11).

- Matavele Chissumba R, Silva-Barbosa SD, Augusto Â, Maueia C, Mabunda N, Gudo ES, et al. CD4+CD25High Treg cells in HIV/HTLV Co-infected patients with neuropathy: high expression of Alpha4 integrin and lower expression of Foxp3 transcription factor. BMC Immunol. 2015 Sep 2;16.

- Yamano Y, Takenouchi N, Li H, Tomaru U, Yao K, Grant CW, et al. Virus-induced dysfunction of CD4+CD25+ T cells in patients with HTLV-I–associated neuroimmunological disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005 May 2;115(5):1361–8. [CrossRef]

- Wouk J, Rechenchoski DZ, Rodrigues BCD, Ribelato EV, Faccin-Galhardi LC. Viral infections and their relationship to neurological disorders. Arch Virol. 2021 Mar 27;166(3):733–53. [CrossRef]

- Paruk HF, Bhigjee AI. Review of the neurological aspects of HIV infection. J Neurol Sci. 2021 Jun;425. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database (company) | Keywords (MeSH) term and text word search | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medline (PubMed) | ("Human T-lymphotropic virus 1"[Mesh] OR "HTLV-I Infections"[Mesh] OR "HTLV-II Infections"[Mesh] OR "HTLV-1"[tiab] OR "HTLV-2"[tiab] OR "HTLV-I"[tiab] OR "HTLV-II"[tiab] OR "HTLV"[tiab]) AND ("Anti-Retroviral Agents" OR "dolutegravir" OR "raltegravir" OR "Isentress" OR "elvitegravir" OR "bictegravir" OR "zidovudine" OR "efavirenz") NOT ("ATL") |

| 2 | Cochrane Library | ( "HTLV" OR " Human T-lymphotropic virus 1" OR "HTLV-I Infections" OR "HTLV-II Infections" OR "HTLV-1" OR "HTLV-2" OR "HTLV-I" OR "HTLV-II" ) AND (“Anti-HIV Agents” OR ‘HIV Protease inhibitors” OR “HIV Integrase Inhibitors” OR “Anti-Retroviral Agents” OR “HIV/drug effects” OR “”Drug Ressistance”) NOT ("ATL") |

| 3 | Scopus (Elsevier) | ( ( ALL ( "HTLV" OR " Human T-lymphotropic virus 1" OR "HTLV-I Infections" OR "HTLV-II Infections" OR "HTLV-1" OR "HTLV-2" OR "HTLV-I" OR "HTLV-II" ) ) AND ( ALL ("Paraparesis, Tropical Spastic" OR "HAM/TSP" OR "Paraparesis, Tropical Spastic/therapy" ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "Paraparesis, Tropical Spastic" OR "HAM/TSP" ) ) ) AND ( ALL ( "Anti-HIV Agents" OR "dolutegravir" OR "raltegravir" OR "Anti-Retroviral Agents" OR "elvitegravir" OR "bictegravir" OR "zidovudine" OR "efavirenz" ) NOT ALL("ATL") ) |

| 4 | Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics) | ALL=("HTLV" OR " Human T-lymphotropic virus 1" OR "HTLV-I Infections" OR "HTLV-II Infections" OR "HTLV-1" OR "HTLV-2" OR "HTLV-I" OR "HTLV-II") AND ALL=("Anti-Retroviral Agents" OR "dolutegravir" OR "raltegravir" OR "Isentress" OR "elvitegravir" OR "bictegravir" OR "zidovudine" OR "efavirenz") NOT ALL=("ATL") |

| Study | design, Country | Population Characteristic | Infection | ART use | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taylor et al., 1999[12] | Cohort, United Kingdon | N=5; female: 4(80%); mean age: 46,6 | HTLV-1 with HAM/TSP: 5 (100%) | 3TC* *A patient who had a recent diagnosis of HAM/TSP received AZT for 3 months and then switched to 3TC |

HTLV- PVL reduced in all patients. Clinical improvement was only observed in one patient with recent onset HAM/TSP during the period in which lamivudine reduced PVL. |

| Zehender et al, 2002 [13] | Retrospective cohort, Italy | N = 90; male: 80%; mean age HIV group: 32 (26-50) mean age HIV/HTLV-2 group: 33 (23-55). |

HIV/HTLV-2: 30 (33,3%) HIV: 60 (66,6%). |

It was not controlled by the study protocol | There was no difference between the monoinfected and coinfected groups for mortality and CD4+ cells count. HLTV-2 infection was an independent predictor for developing PN, during ART PN incidence considerably decreased |

| Taylor et al., 2006 [14] | RCT, United Kingdon | N=16, male: 5 (31%); mean age: 57,4 | HTLV-1 with HAM/TSP: 16 (100%) | AZT + 3TC | There was a tendency for to decreasing CD8+ cells count with the use of ART. There was no significant change in PVL and CD4+ cells count. No significant changes in pain score, urinary frequency or nocturia. A patient with recent-onset HAM/TSP, had an improvement which persisted only during the period of ART use. |

| Beilke et al., 2007 [15] | Cross-section, USA | N=72, male: 59 (76%) Age: >45 years (72%) | HIV/HTLV-1: 20 (27,7%) HIV/HTLV-2: 52 (72,3%) |

Any triple ART | Participants' PVL were higher in HIV/HTLV-1 than in HIV/HTLV-2 and in cases with positive PBMC cultures. |

| Macchi et al., 2011 [16] | Cohort, United Kingdon | N=5 Female: 4(80%); mean age: 44.8 (±15) | HTLV-1 with HAM/TSP: 5 (100%) | TDF | There was an increase in CD4 and CD8+ cells count. No significant clinical improvement was seen, except in those who received TDF for a longer period of time and experienced improvement in pain and gait. There was no significant change in PVL |

| Treviño et al., 2012[17] | Pilot study, Spain | N=5; Female: 3 (60%); median age: 52 | HTLV-1 without HAM/TSP: 2(40%) HTLV-1 with HAM/TSP: 2 (40%) HIV/HTLV-1: 1(20%) |

RAL | There was a transient reduction in PVL in the two symptomatic patients. No clinical improvements were observed. |

| Abad-Fernandez et al., 2014 [18] | Cohort, Spain | RAL group: N=4; male:4(26,6%); median age: 51(48-54). Control group: N=11(73,4), median age: 50 (46-56) |

HIV/HTLV-2: 15 (100%) | Intervention: ART with RAL Control: ART whitout RAL |

There was an initial increase followed by a reduction in PVL in the RAL group. This was not observed in the control group. There were no changes in CD4 and CD8+ cells count in both groups |

| Enose-Akahata et al., 2021 [19] | Clinical trail, USA? | RAL group: N=16 (28,6%); famale: 10(62,5%); mean age: 53,5 Control group: HAM/TSP: N=13(23,2%) People without infection: N=27(48,2) age and gender not described |

HTLV-1 with HAM/TSP:29 (51,8%) People without infection: 27 (48,2%) |

Intervention:ART with RAL Control group: without ART |

There was a subjective improvement in symptoms with the use of RAL, but not in objective clinical measurements. PVL in CSF and PBMC remained stable throughout the study. There was a reduction in CD4 and CD8 in peripheral blood after using RAL. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).