Submitted:

09 July 2024

Posted:

10 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

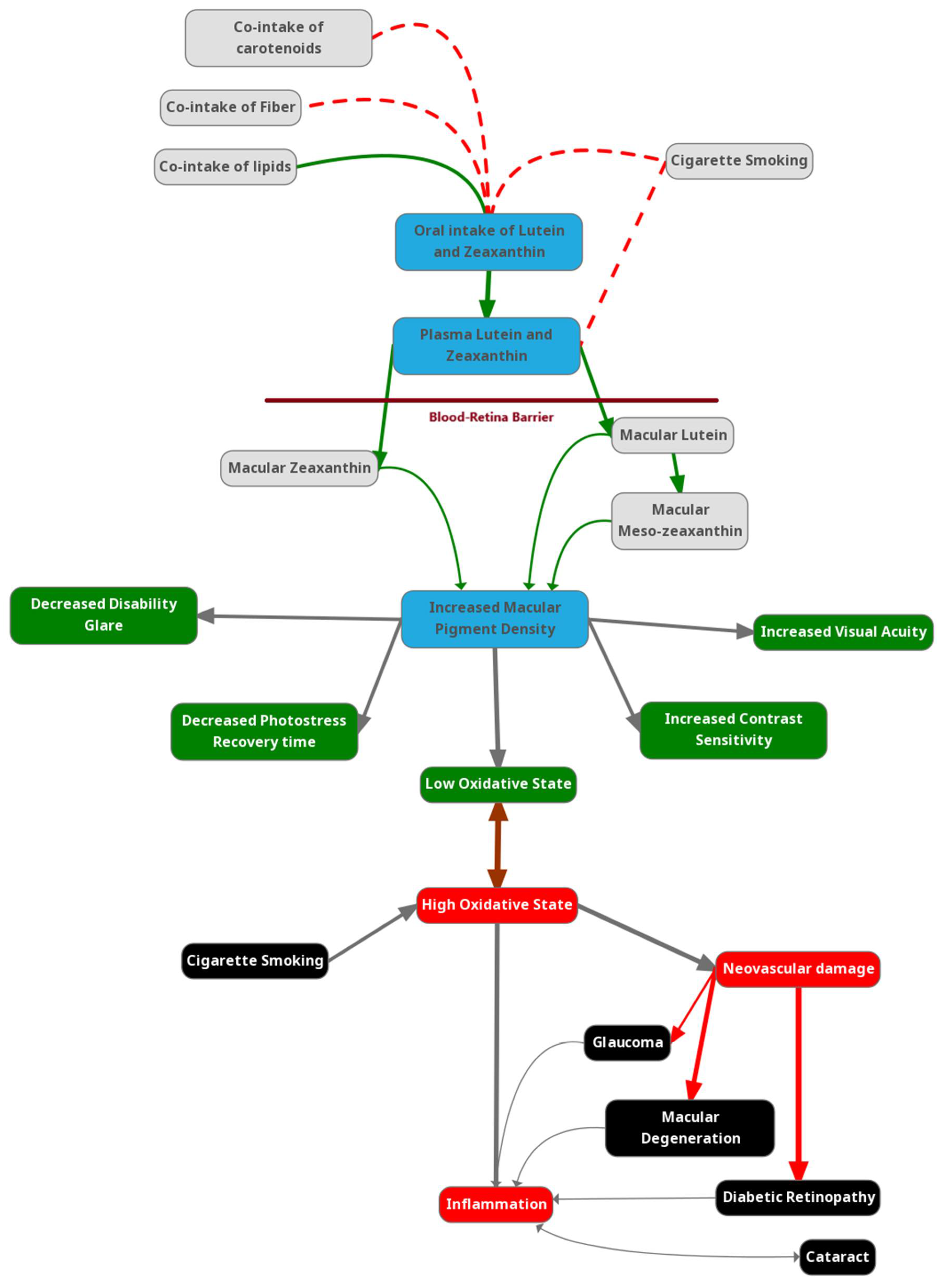

1. Introduction

1.1. Structure:

1.2. Nutrition:

2.1. Macular Pigment Optical Density (MPOD):

2.2. Measurement of MPOD:

3.1. MPOD in Ocular and Systemic Disease:

3.2. MPOD and Age-Related Macular Degeneration

3.3. Glaucoma

3.4. Systemic Disease

3.4.1. Diabetic Retinopathy

3.5. Visual Performance

3.7. MPOD and Cognitive Function

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bone, R.A., Landrum, J.T., Hime, G.W., Cains, A., Zamor, J. Stereochemistry of the human macular carotenoids. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34(6):2033-2040.

- Bone, R.A, Landrum, J.T., Tarsis, S.L. Preliminary identification of the human macular pigment. Vision Res. 1985;25(11):1531-1535. [CrossRef]

- Handelman, G. J., Dratz, E. A., Reay, C. C., & van Kuijk, J. G. Carotenoids in the human macula and whole retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988;29(6):850-855.

- Bone, R. A., Landrum, J. T., Friedes, L. M., Gomez, C. M., Kilburn, M. D., Menendez, E., Vidal, I., & Wang, W. Distribution of lutein and zeaxanthin stereoisomers in the human retina. Exp Eye Res. 1997;64(2):211-218.

- Dorey CK, Gierhart D, Fitch KA, Crandell I, Craft NE. Low Xanthophylls, Retinol, Lycopene, and Tocopherols in Grey and White Matter of Brains with Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2023;94(1):1-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krinsky, N.I. Carotenoid protection against oxidation. Pure Appl Chem, 1979;51:649-660.

- Brown, M. J., Ferruzzi, M. G., Nguyen, M. L., Cooper, D. A., Eldridge, A. L., Schwartz, S. J., & White, W. S. Carotenoid bioavailability is higher from salads ingested with full-fat than with fat-reduced salad dressings as measured with electrochemical detection. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(2):396-403.

- Reboul, E., Thap, S., Tourniaire, F., André, M., Juhel, C., Morange, S., Amiot, M. J., Lairon, D., & Borel, P. Differential effect of dietary antioxidant classes (carotenoids, polyphenols, vitamins C and E on lutein absorption. Br J Nutr. 2007;97(3):440-446.

- Hornero-Méndez, D., Mínguez-Mosquera, M.I. Bioaccessibility of carotenes from carrots: Effect of cooking and addition of oil. Innov Food Sci Emer Tech. 2007;8(3):407-412.

- Riedl, J., Linseisen, J., Hoffmann, J., Wolfram, G. Some dietary fibers reduce the absorption of carotenoids in women. J Nutr. 1999;129(12):2170-2176. [CrossRef]

- Perry, A., Rasmussen, H., Johnson, E. Xantophyll (lutein, zeaxanthin) content in fruits, vegetables and corn and egg products. J Food Composition Analysis. 2009;22:9-15.

- Sanabria, J.C., Bass, J., Spors, F., Gierhart, D.L., Davey, P.G. Measurement of Carotenoids in Perifovea using the Macular Pigment Reflectometer. J Vis Exp. 2020 Jan 29;(155).

- Davey, P.G., Rosen, R.B., Gierhart, D.L. Macular Pigment Reflectometry: Developing Clinical Protocols, Comparison with Heterochromatic Flicker Photometry and Individual Carotenoid Levels. Nutrients. 2021 Jul 26;13(8):2553.

- Goodrow, E. F., Wilson, T. A., Houde, S. C., Vishwanathan, R., Scollin, P. A., Handelman, G., & Nicolosi, R. J. Consumption of one egg per day increases serum lutein and zeaxanthin concentrations in older adults without altering serum lipid and lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations. J Nutr. 2006;136(10):2519-2524.

- Müller, H. [Daily intake of carotenoids (carotenes and xanthophylls) from total diet and the carotenoid content of selected vegetables and fruit. Z Ernahrungswiss. 1996;35(1):45-50. [CrossRef]

- Bone, R,A, Landrum, J,T. Heterochromatic flicker photometry. Arch Biochem Biophys 2004; 430:137–142.

- Stringham, J. M., Hammond, B. R., Nolan, J. M., Wooten, B. R., Mammen, A., Smollon, W., & Snodderly, D. M. The utility of using customized heterochromatic flicker photometry (cHFP) to measure macular pigment in patients with AMD. Exp Eye Res. 2008; 87:445–453.

- van de Kraats, J., Berendschot, T. T., Valen, S., & van Norren, D. Fast assessment of the central macular pigment density with natural pupil using the macular pigment reflectometer. J Biomed Opt, 2006; 11:064031.

- Bone, R. A., Brener, B., & Gibert, J. C. Macular pigment, photopigments, and melanin: distributions in young subjects determined by four-wavelength reflectometry. Vision Res 2007; 47:3259–3268.

- Morita, H., Matsushita, I., Fujino, Y., Obana, A., & Kondo, H. Measuring MPOD using reflective images of confocal scanning laser system. Jpn J Ophthalmol, 2024; 68(1), 19–25.

- Wooten, B. R., & Hammond, B. R., Jr. Spectral absorbance and spatial distribution of macular pigment using heterochromatic flicker photometry. Optom Vis Sci 2005; 82:378–386.

- Bernstein, P. S., Yoshida, M. D., Katz, N. B., McClane, R. W., & Gellermann, W. Raman detection of macular carotenoid pigments in intact human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1998; 39:2003–2011.

- Delori F. C. Spectrophotometer for noninvasive measurement of intrinsic fluorescence and reflectance of the ocular fundus. Appl Opt 1994; 33:7439–7452.

- Davey, P. G., Alvarez, S. D., & Lee, J. Y. Macular pigment optical density: repeatability, intereye correlation, and effect of ocular dominance. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:1671-1678.

- National Society to Prevent Blindness Vision Problems in the US: Data Analyses. New York: National Society to Prevent Blindness, 1980;1–46.

- Klein, R., Klein, B. E., Tomany, S. C., Meuer, S. M., & Huang, G. H. Ten-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmol 2002; 109(10):1767–1779.

- Lem DW, Davey PG, Gierhart DL, Rosen RB. A Systematic Review of Carotenoids in the Management of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021 Aug 5;10(8):1255. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research Group. Lutein + Zeaxanthin and Omega-3 Fatty Acids for AMD: The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;309(19):2005–2015.

- Chew, E. Y., Clemons, T. E., Agrón, E., Domalpally, A., Keenan, T. D. L., Vitale, S., Weber, C., Smith, D. C., Christen, W., & AREDS2 Research Group. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022; Jul 1;140(7):692-698.

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) Research Group, Chew, E. Y., SanGiovanni, J. P., Ferris, F. L., Wong, W. T., Agron, E., Clemons, T. E., Sperduto, R., Danis, R., Chandra, S. R., Blodi, B. A., Domalpally, A., Elman, M. J., Antoszyk, A. N., Ruby, A. J., Orth, D., Bressler, S. B., Fish, G. E., Hubbard, G. B., Klein, M. L., Bernstein, P. Lutein/zeaxanthin for the treatment of age-related cataract: AREDS2 randomized trial report no. 4. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013; Jul;131(7):843-50.

- Beatty, S., Murray, I. J., Henson, D. B., Carden, D., Koh, H., & Boulton, M. E. Arch Ophthalmol 1999; 113:1518–1523.

- Tsika, C., Tsilimbaris, M. K., Makridaki, M., Kontadakis, G., Plainis, S., & Moschandreas, J. Assessment of MPOD (MPOD) in patients with unilateral wet AMD (AMD). Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(7):e573-e578.

- Bone, R. A., Landrum, J. T., Mayne, S. T., Gomez, C. M., Tibor, S. E., & Twaroska, E. E. Macular pigment in donor eyes with and without AMD: a case-control study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001; 42(1):235–240.

- Beatty, S., Chakravarthy, U., Nolan, J. M., Muldrew, K. A., Woodside, J. V., Denny, F., & Stevenson, M. R. Secondary outcomes in a clinical trial of carotenoids with coantioxidants versus placebo in early age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol. 2013;120(3):600-606.

- Dawczynski, J., Jentsch, S., Schweitzer, D., Hammer, M., Lang, G. E., & Strobel, J. Long term effects of lutein, zeaxanthin and omega-3-LCPUFAs supplementation on optical density of macular pigment in AMD patients: the LUTEGA study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(11):2711-2723.

- Murray, I. J., Makridaki, M., van der Veen, R. L., Carden, D., Parry, N. R., & Berendschot, T. T. Lutein supplementation over a one-year period in early AMD might have a mild beneficial effect on visual acuity: The CLEAR Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(3):1781-1788.

- Richer, S., Stiles, W., Statkute, L., Pulido, J., Frankowski, J., Rudy, D., Pei, K., Tsipursky, M., & Nyland, J. Double-masked, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of lutein and antioxidant supplementation in the intervention of atrophic age-related macular degeneration: the Veterans LAST study (Lutein Antioxidant Supplementation Trial). Optometry. 2004;75:216-230.

- Trieschmann, M., Beatty, S., Nolan, J. M., Hense, H. W., Heimes, B., Austermann, U., Fobker, M., & Pauleikhoff, D. Changes in macular pigment optical density and serum concentrations of its constituent carotenoids following supplemental lutein and zeaxanthin: the LUNA study. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84(4):718-728.

- Richer, S. P., Stiles, W., Graham-Hoffman, K., Levin, M., Ruskin, D., Wrobel, J., Park, D. W., & Thomas, C. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of zeaxanthin and visual function in patients with atrophic age-related macular degeneration: The Zeaxanthin and Visual Function Study (ZVF). Optometry. 2011;82(11):667-680.

- Weigert, G., Kaya, S., Pemp, B., Sacu, S., Lasta, M., Werkmeister, R. M., Dragostinoff, N., Simader, C., Garhöfer, G., Schmidt-Erfurth, U., & Schmetterer, L. Effects of lutein supplementation on macular pigment optical density and visual acuity in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(11):8174-8178.

- Sabour-Pickett, S., Beatty, S., Connolly, E., Loughman, J., Stack, J., Howard, A., Klein, R., Klein, B. E., Meuer, S. M., Myers, C. E., Akuffo, K. O., & Nolan, J. M. Supplementation with three different macular carotenoid formulations in patients with early age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2014;34(10):1757-1766.

- Huang, Y. M., Dou, H. L., Huang, F. F., Xu, X. R., Zou, Z. Y., & Lin, X. M. Effect of supplemental lutein and zeaxanthin on serum, macular pigmentation, and visual performance in patients with early age-related macular degeneration. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:564738.

- Davey, P. G., Henderson, T., Lem, D. W., Weis, R., Amonoo-Monney, S., & Evans, D. W. Visual function and macular carotenoid changes in eyes with retinal drusen—An open label randomized controlled trial to compare a micronized lipid-based carotenoid liquid supplementation and AREDS-2 formula. Nutrients. 2020;12:3271.

- Ma, L., Yan, S. F., Huang, Y. M., Lu, X. R., Qian, F., Pang, H. L., Xu, X. R., Zou, Z. Y., Dong, P. C., Xiao, X., Wang, X., Sun, T. T., Dou, H. L., & Lin, X. M. Effect of lutein and zeaxanthin on macular pigment and visual function in patients with early age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol. 2012;119(11):2290-2297.

- Weinreb, R. N., Aung, T., & Medeiros, F. A. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: A review. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014; 311, 1901–1911.

- Kumar, D. M., & Agarwal, N. Oxidative Stress in Glaucoma: A Burden of Evidence. J Glaucoma, 2007; 16 (3), 334-343.

- Choi, J. S., Kim, D., Hong, Y. M., Mizuno, S., & Joo, C. K. Inhibition of nNOS and COX-2 expression by lutein in acute retinal ischemia. Nutrition 2006; 22, 668–671.

- Fung, F. K., Law, B. Y., & Lo, A. C. Lutein Attenuates Both Apoptosis and Autophagy upon Cobalt (II) Chloride-Induced Hypoxia in Rat Muller Cells. PLoS ONE 2016; 11, e0167828.

- Dilsiz, N., Sahaboglu, A., Yildiz, M. Z., & Reichenbach, A. Protective effects of various antioxidants during ischemia-reperfusion in the rat retina. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2006; 244, 627–633.

- Li, S. Y., Fu, Z. J., Ma, H., Jang, W. C., So, K. F., Wong, D., & Lo, A. C. Effect of lutein on retinal neurons and oxidative stress in a model of acute retinal ischemia/reperfusion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50, 836–843.

- Bignami A, Dahl D. The radial glia of Müller in the rat retina and their response to injury. An immunofluorescence study with antibodies to the glial fibrillary acidic (GFA) protein. Exp Eye Res. 1979 Jan;28(1):63-9.

- Bringmann A, Pannicke T, Grosche J, Francke M, Wiedemann P, Skatchkov SN, Osborne NN, Reichenbach A. Müller cells in the healthy and diseased retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2006 Jul;25(4):397-424.

- Siah, W. F., Loughman, J., & O'Brien, C. Lower macular pigment optical density in foveal-involved glaucoma. Ophthalmol. 2015;122(10):2029-2037.

- Lem DW, Gierhart DL, Davey PG. Carotenoids in the Management of Glaucoma: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Nutrients. 2021 Jun 6;13(6):1949.

- Fikret, C., & Ucgun, N. I.Macular pigment optical density change analysis in primary open-angle glaucoma and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. Int Ophthalmol. 2021;41(6):2235-2240.

- Bruns, Y., Junker, B., Boehringer, D., Framme, C., & Pielen, A. Comparison of macular pigment optical density in glaucoma patients and healthy subjects – a prospective diagnostic study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:1011-1017.

- Loughman, J., Loskutova, E., Butler, J. S., Siah, W. F., & O'Brien, C. Macular pigment response to lutein, zeaxanthin, and meso-zeaxanthin supplementation in open-angle glaucoma: a randomized controlled trial. Ophthalmol Sci. 2021;1(3):100039.

- Ji, Y., Zuo, C., Lin, M., Zhang, X., Li, M., Mi, L., Liu, B., & Wen, F. Macular pigment optical density in Chinese primary open angle glaucoma using the one-wavelength reflectometry method. J Ophthalmol. 2016;2016:2792103.

- Arnould, L., Seydou, A., Binquet, C., Gabrielle, P. H., Chamard, C., Bretillon, L., Bron, A. M., Acar, N., & Creuzot-Garcher, C. Macular pigment and open-angle glaucoma in the elderly: The Montrachet population-based study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(7):1830.

- Daga, F. B., Ogata, N. G., Medeiros, F. A., Moran, R., Morris, J., Zangwill, L. M., Weinreb, R. N., & Nolan, J. M. Macular pigment and visual function in patients with glaucoma: the San Diego Macular Pigment Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(11):4471-4476.

- Lawler, T., Mares, J. A., Liu, Z., Thuruthumaly, C., Etheridge, T., Vajaranant, T. S., Domalpally, A., Hammond, B. R., Wallace, R. B., Tinker, L. F., Nalbandyan, M., Klein, B. E. K., Liu, Y., Carotenoids in Age-Related Eye Disease Study Investigators, & Second Carotenoids in Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group Association of macular pigment optical density with retinal layer thicknesses in eyes with and without manifest primary open-angle glaucoma. BMJ Open Ophth. 2023;8(1):e001331.

- Igras, E., Loughman, J., Ratzlaff, M., O'Caoimh, R., & O'Brien, C.. Evidence of lower macular pigment optical density in chronic open angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(8):994-998.

- Siah, W. F., O'Brien, C., & Loughman, J. J. Macular pigment is associated with glare-affected visual function and central visual field loss in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102(7):929-935.

- Eraslan, N., Yilmaz, M., & Celikay, O. Assessment of macular pigment optical density of primary open-angle glaucoma patients under topical medication. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2023;42:103585.

- Lem, D. W., Gierhart, D. L., & Davey, P. G. A systematic review of carotenoids in the management of diabetic retinopathy. Nutrients, 2011; 13(7), 2441.

- Scanlon, G., Loughman, J., Farrell, D., & McCartney, D. A review of the putative causal mechanisms associated with lower macular pigment in diabetes mellitus. Nutrition research reviews, 2019; 32(2), 247-264.

- Lima, V. C., Rosen, R. B., Maia, M., Prata, T. S., Dorairaj, S., Farah, M. E., & Sallum, J. MPOD measured by dual-wavelength autofluorescence imaging in diabetic and nondiabetic patients: a comparative study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci., 2010; pp. 5840–5845.

- Dong, L. Y., Jin, J., Lu, G., & Kang, X. L. Astaxanthin attenuates the apoptosis of retinal ganglion cells in db/db mice by inhibition of oxidative stress. Marine Drugs, 2013; 11(3), 960-974.

- Lima, V. C., Rosen, R. B., & Farah, M. Macular pigment in retinal health and disease. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2016;2:19.

- Scanlon, G., McCartney, D., Butler, J. S., Loskutova, E., & Loughman, J. Identification of Surrogate Biomarkers for the Prediction of Patients at Risk of Low Macular Pigment in Type 2 Diabetes. Curr Eye Res. 2019;44(12):1369-1380.

- Bikbov, M.M., Fayzrakhmanov, R.R., Yarmukhametova, A.L., Zainullin, R.M. Structural and functional analysis of the central zone of the retina in patients with diabetic macular edema. Сахарный диабет. 2015;18(4):99-104.

- Scanlon, G., Connell, P., Ratzlaff, M., Foerg, B., McCartney, D., Murphy, A., OʼConnor, K., & Loughman, J. Macular pigment optical density is lower in type 2 diabetes, compared with type 1 diabetes and normal controls. Retina. 2015;35:1808–1816.

- She, C. Y., Gu, H., Xu, J., Yang, X. F., Ren, X. T., & Liu, N. P. Association of macular pigment optical density with early stage of non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Ophthalmol. 2016;9(10):1433-1438.

- Bikbov, M.M., Zainullin, R.M., Faizrakhmanov, R.R.. Macular pigment optical density alteration as an indicator of diabetic macular edema development. Sovremennye Tehnologii v Medicine. 2015;7(3):73-75. [CrossRef]

- Chous, A. P., Richer, S. P., Gerson, J. D., & Kowluru, R. A. The Diabetes Visual Function Supplement Study (DiVFuSS). Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:227–234.

- Zagers, N. P., Pot, M. C., & van Norren, D. Spectral and directional reflectance of the fovea in diabetes mellitus: photoreceptor integrity, macular pigment and lens. Vision Res. 2005;45(13):1745-1753.

- Varghese, M., & Antony, J. Assessment of macular pigment optical density using fundus reflectometry in diabetic patients. Middle East African J Ophthalmol. 2019;26(3):145-150.

- Cennamo, G, Montorio, D, Santoro, G, Cennamo, G. Evaluation of choroidal and retinal thickness changes measured by swept-source optical coherence tomography in patients with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. Retina. 2019;39(4):702-707.

- Ford, E. S., Will, J. C., Bowman, B. A., & Narayan, K. M. Diabetes mellitus and serum carotenoids: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol 1999; 149(2):168–176.

- Kowluru, R. A., Menon, B., & Gierhart, D. L. Beneficial effect of zeaxanthin on retinal metabolic abnormalities in diabetic rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; Apr;49(4):1645-51.

- Chous, A. P., Richer, S. P., Gerson, J. D., & Kowluru, R. A. The Diabetes Visual Function Supplement Study (DiVFuSS). Br J Ophthal. 2016;100:227-234.

- Hammond, B. R., Jr, Fletcher, L. M., & Elliott, J. G. Glare disability, photostress recovery, and chromatic contrast: relation to macular pigment and serum lutein and zeaxanthin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:476–81.

- Kvansakul, J., Rodriguez-Carmona, M., Edgar, D. F., Barker, F. M., Köpcke, W., Schalch, W., & Barbur, J. L. Supplementation with the carotenoids lutein or zeaxanthin improves human visual performance. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2006;26:362–71.

- Loughman, J., Akkali, M. C., Beatty, S., Scanlon, G., Davison, P. A., O'Dwyer, V., Cantwell, T., Major, P., Stack, J., & Nolan, J. M. The relationship between macular pigment and visual performance. Vis Res. 2010;50:1249–56.

- Stringham, J. M., O'Brien, K. J., & Stringham, N. T. Contrast sensitivity and lateral inhibition are enhanced with macular carotenoid supplementation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:2291–5.

- Stringham, J. M., Garcia, P. V., Smith, P. A., McLin, L. N., & Foutch, B. K. Macular pigment and visual performance in glare: benefits for photostress recovery, disability glare, and visual discomfort. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:7406–15.

- Bone R.A., Davey, P.G., Roman, B.O., Evans, D.W. Efficacy of Commercially Available Nutritional Supplements: Analysis of Serum Uptake, Macular Pigment Optical Density and Visual Functional Response. Nutrients. 2020 May 6;12(5):1321.

- Yao, Y., Qiu, Q. H., Wu, X. W., Cai, Z. Y., Xu, S., & Liang, X. Q. Lutein supplementation improves visual performance in Chinese drivers: 1-year randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Nutrition. 2013; Jul-Aug;29(7-8):958-64.

- Stringham, J. M., Stringham, N. T., & O'Brien, K. J. Macular Carotenoid Supplementation Improves Visual Performance, Sleep Quality, and Adverse Physical Symptoms in Those with High Screen Time Exposure. Foods. 2017;6(7):47.

- Richer, S., Novil, S., Gullett, T., Dervishi, A., Nassiri, S., Duong, C., Davis, R., & Davey, P. G. Night Vision and Carotenoids (NVC): A Randomized Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial on Effects of Carotenoid Supplementation on Night Vision in Older Adults. Nutrients. 2021;13(9):3191.

- Engles, M., Wooten, B., Hammond, B. Macular pigment: A test of the acuity hypothesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(6):2922-2931.

- Tudosescu, R., Alexandrescu, C. M., Istrate, S. L., Vrapciu, A. D., Ciuluvică, R. C., & Voinea, L. Correlations between internal and external ocular factors and macular pigment optical density. Romanian J Ophthalmol. 2018;62(1):42-47.

- Patryas, L., Parry, N. R., Carden, D., Aslam, T., & Murray, I. J. The association between dark adaptation and macular pigment optical density in healthy subjects. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252(4):657-663.

- Bovier, E. R., Renzi, L. M., & Hammond, B. R. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the effects of lutein and zeaxanthin on neural processing speed and efficiency. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e108178.

- Kvansakul, J., Rodriguez-Carmona, M., Edgar, D. F., Barker, F. M., Köpcke, W., Schalch, W., & Barbur, J. L. Supplementation with the carotenoids lutein or zeaxanthin improves human visual performance. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2006;26(4):362-371.

- Putnam, C. M., & Bassi, C. J. Macular pigment spatial distribution effects on glare disability. J. Optom. 2015;8(4):258-265.

- Stringham, J. M., & Hammond, B. R. Macular pigment and visual performance under glare conditions. Optom Vis Sci. 2008;85(2):82-88.

- Stringham, J. M., O'Brien, K. J., & Stringham, N. T. Contrast sensitivity and lateral inhibition are enhanced with macular carotenoid supplementation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(4):2291-2295.

- Nolan, J. M., Power, R., Stringham, J., Dennison, J., Stack, J., Kelly, D., Moran, R., Akuffo, K. O., Corcoran, L., & Beatty, S. Enrichment of macular pigment enhances contrast sensitivity in subjects free of retinal disease: central retinal enrichment supplementation trials – report 1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(7):3429-3439.

- Hammond, B. R., Fletcher, L. M., Roos, F., Wittwer, J., & Schalch, W.A double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the effects of lutein and zeaxanthin on photostress recovery, glare disability, and chromatic contrast. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(12):8583-8589.

- Hammond, B. R., Jr, Fletcher, L. M., & Elliott, J. G. Glare disability, photostress recovery, and chromatic contrast: Relation to macular pigment and serum lutein and zeaxanthin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(1):476.

- Stringham, J. M., O'Brien, K. J., & Stringham, N. T. Macular carotenoid supplementation improves disability glare performance and dynamics of Photostress Recovery. Eye and Vision. 2016;3(1).

- Hammond, B. R., Jr, Wooten, B. R., & Snodderly, D. M. Preservation of visual sensitivity of older subjects: association with macular pigment density. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39(2):397-406.

- Estévez-Santiago, R., Olmedilla-Alonso, B., & Beltrán-de-Miguel, B. Assessment of lutein and zeaxanthin status and dietary markers as predictors of the contrast threshold in 2 age groups of men and women. Nutr Res. 2016;36(7):719-730.

- Nolan, J. M., Loughman, J., Akkali, M. C., Stack, J., Scanlon, G., Davison, P., & Beatty, S. The impact of macular pigment augmentation on visual performance in normal subjects: COMPASS. Vision Res. 2011;51(5):459-469.

- Loughman, J., Akkali, M. C., Beatty, S., Scanlon, G., Davison, P. A., O'Dwyer, V., Cantwell, T., Major, P., Stack, J., & Nolan, J. M. The relationship between macular pigment and visual performance. Vision Res. 2010;50(13):1249-1256.

- Johnson, E. J., Vishwanathan, R., Johnson, M. A., Hausman, D. B., Davey, A., Scott, T. M., Green, R. C., Miller, L. S., Gearing, M., Woodard, J., Nelson, P. T., Chung, H. Y., Schalch, W., Wittwer, J., & Poon, L. W. Relationship between serum and brain carotenoids, α-tocopherol, and retinol concentrations and cognitive performance in the oldest old from the Georgia Centenarian Study. J. Aging Res. 2013;2013:951786.

- Feeney, J., O'Leary, N., Moran, R., O'Halloran, A. M., Nolan, J. M., Beatty, S., Young, I. S., & Kenny, R. A. Plasma lutein and zeaxanthin are associated with better cognitive function across multiple domains in a large population-based sample of older adults: Findings from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Aging. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017;72:1431–1436.

- Power, R., Coen, R. F., Beatty, S., Mulcahy, R., Moran, R., Stack, J., Howard, A. N., & Nolan, J. M. Supplemental retinal carotenoids enhance memory in healthy individuals with low levels of macular pigment in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018;61:947–961.

- Lindbergh, C. A., Mewborn, C. M., Hammond, B. R., Renzi-Hammond, L. M., Curran-Celentano, J. M., & Miller, L. S. Relationship of lutein and zeaxanthin levels to neurocognitive functioning: An fMRI study of older adults. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2017;23:11–22.

- Feeney, J., Finucane, C., Savva, G. M., Cronin, H., Beatty, S., Nolan, J. M., & Kenny, R. A. Low macular pigment optical density is associated with lower cognitive performance in a large, population-based sample of older adults. Neurobiology Aging. 2013;34(11):2449-2456.

- Khan, N. A., Walk, A. M., Edwards, C. G., Jones, A. R., Cannavale, C. N., Thompson, S. V., Reeser, G. E., & Holscher, H. D. Macular Xanthophylls Are Related to Intellectual Ability among Adults with Overweight and Obesity. Nutrients. 2018;10(4):396.

- Saint, S. E., Renzi-Hammond, L. M., Khan, N. A., Hillman, C. H., Frick, J. E., & Hammond, B. R.. The Macular Carotenoids are Associated with Cognitive Function in Preadolescent Children. Nutrients. 2018;10(2):193.

- Renzi-Hammond, L. M., Bovier, E. R., Fletcher, L. M., Miller, L. S., Mewborn, C. M., Lindbergh, C. A., Baxter, J. H., & Hammond, B. R. Effects of a Lutein and Zeaxanthin Intervention on Cognitive Function: A Randomized, Double-Masked, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Younger Healthy Adults. Nutrients. 2017;9(11):1246.

- Barnett, S. M., Khan, N. A., Walk, A. M., Raine, L. B., Moulton, C., Cohen, N. J., Kramer, A. F., Hammond, B. R., Jr, Renzi-Hammond, L., & Hillman, C. H. Macular pigment optical density is positively associated with academic performance among preadolescent children. Nutr Neurosci. 2018;21(9):632-640.

- Lindbergh, C. A., Renzi-Hammond, L. M., Hammond, B. R., Terry, D. P., Mewborn, C. M., Puente, A. N., & Miller, L. S. Lutein and Zeaxanthin Influence Brain Function in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018;24(1):77-90.

- Kelly, D., Coen, R. F., Akuffo, K. O., Beatty, S., Dennison, J., Moran, R., Stack, J., Howard, A. N., Mulcahy, R., & Nolan, J. M. Cognitive Function and Its Relationship with Macular Pigment Optical Density and Serum Concentrations of its Constituent Carotenoids. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(1):261-277.

- Power, R., Coen, R. F., Beatty, S., Mulcahy, R., Moran, R., Stack, J., Howard, A. N., & Nolan, J. M. Supplemental Retinal Carotenoids Enhance Memory in Healthy Individuals with Low Levels of Macular Pigment in A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61(3):947-961.

- Ajana, S., Weber, D., Helmer, C., Merle, B. M., Stuetz, W., Dartigues, J. F., Rougier, M. B., Korobelnik, J. F., Grune, T., Delcourt, C., & Féart, C. Plasma Concentrations of Lutein and Zeaxanthin, Macular Pigment Optical Density, and Their Associations With Cognitive Performances Among Older Adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(5):1828-1835.

- Vishwanathan, R., Iannaccone, A., Scott, T. M., Kritchevsky, S. B., Jennings, B. J., Carboni, G., Forma, G., Satterfield, S., Harris, T., Johnson, K. C., et al. Macular pigment optical density is related to cognitive function in older people. Age Ageing. 2014;43(2):271-275.

- Renzi, L. M., Dengler, M. J., Puente, A., Miller, L. S., & Hammond, B. R., Jr. Relationships between macular pigment optical density and cognitive function in unimpaired and mildly cognitively impaired older adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(7):1695-1699.

- Feeney, J., Finucane, C., Savva, G. M., Cronin, H., Beatty, S., Nolan, J. M., & Kenny, R. A. Low macular pigment optical density is associated with lower cognitive performance in a large, population-based sample of older adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(11):2449-2456.

- Stringham, N. T., Holmes, P. V., & Stringham, J. M. Effects of macular xanthophyll supplementation on brain-derived neurotrophic factor, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and cognitive performance. Physiol Behav. 2019;211:112650.

- Hassevoort, K. M., Khazoum, S. E., Walker, J. A., Barnett, S. M., Raine, L. B., Hammond, B. R., Renzi-Hammond, L. M., Kramer, A. F., Khan, N. A., Hillman, C. H., & Cohen, N. J. Macular Carotenoids, Aerobic Fitness, and Central Adiposity Are Associated Differentially with Hippocampal-Dependent Relational Memory in Preadolescent Children. J Pediatr. 2017;183:108-114.e1.

- Edwards, C. G., Walk, A. M., Cannavale, C. N., Thompson, S. V., Reeser, G. E., Holscher, H. D., & Khan, N. A. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63(15):e1801059.

- Mewborn, C. M., Lindbergh, C. A., Robinson, T. L., Gogniat, M. A., Terry, D. P., Jean, K. R., Hammond, B. R., Renzi-Hammond, L. M., & Miller, L. S. Lutein and Zeaxanthin Are Positively Associated with Visual-Spatial Functioning in Older Adults: An fMRI Study. Nutrients. 2018;10(4):458.

- Davey, P.G., Lievens, C., Ammono-Monney, S. Differences in macular pigment optical density across four ethnicities: a comparative study. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2020 Jun 15;12:2515841420924167.

| Figure 100. | Trans-Lutein (ug per 100g) | Trans-Zeaxanthin (ug per 100g) | L/Z Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asparagus, cooked | 991 | 0 | - |

| Broccoli, cooked | 772 | 0 | - |

| Cucumber | 361 | 0 | - |

| Spinach, cooked | 12,640 | 0 | - |

| Spinach, raw | 6,603 | 0 | - |

| Tomato, raw | 32 | 0 | - |

| Lettuce, romaine | 3,824 | 0 | - |

| Lettuce, iceberg | 171 | 12 | 14.3 |

| Green beans, cooked from frozen | 306 | 0 | - |

| Kale, cooked | 8,884 | 0 | - |

| Pepper, orange | 208 | 1,665 | 0.1 |

| Pepper, green | 173 | 0 | - |

| Bread, white | 15 | 0 | - |

| Egg (yolk + white), cooked | 237 | 216 | 1.1 |

| Egg yolk, cooked | 645 | 587 | 1.1 |

| Pistachio, shelled | 1405 | 0 | - |

| Grapes, green | 53 | 6 | 8.8 |

| Cilantro | 7703 | 0 | - |

| Lima beans, cooked | 155 | 0 | - |

| Olive, green | 79 | 0 | - |

| Parsley, raw | 4326 | 0 | - |

| Squash, yellow, cooked | 150 | 0 | - |

| Zucchini, cooked with skin | 1355 | 0 | - |

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Inclusion Criteria | Sample Size | Interventions | Duration | Relation between MPOD & AMD | MPOD Technique | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beatty study (2013) [34] | RCT | Adults ≥55 years with early or late-stage AMD. | 433 | Group 1: L and Z, Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Copper, Zinc.Group 2: Placebo. | Minimum 12 months, up to 36 months | Supplementation with L, Z, and antioxidants showed functional and morphologic benefits in early AMD. MPOD increased in the active group and decreased in the placebo group. | RS | |

| LUTEGA study (2013) [35] | RCT | Adults 60-80 years with non-exudative AMD. | 172 | Group 1: L, Z, Omega-3, antioxidants. Group 2: Placebo |

12 months | Supplementation resulted in a considerable increase in MPOD and improvement/stabilization in BCVA. No difference in MPOD accumulation between dosages. | FA | |

| CLEAR study (2013) [36] | RCT | Adults 50-80 years with early AMD. | 72 | Group 1: L (10 mg) Group 2: Placebo | 12 months | Lutein supplementation increased MPOD and may have a mild beneficial effect on visual acuity. No change in MPOD found in the placebo group. | HFP | |

| LAST study (2004) [37] | RCT | Adults 55-80 years with atrophic AMD. | 90 | Group 1: L (10 mg) Group 2: L (10 mg) with antioxidants Group 3: Placebo |

12 months | Lutein alone or with antioxidants improved MPOD, glare recovery, and contrast sensitivity. No significant change in placebo group. | HFP | |

| LUNA study (2007) [38] | RCT | Adults ≥55 years with or without AMD. | 120 | Group 1: L (6 mg) Group 2: Placebo |

6 months | Lutein supplementation increased MPOD and improved visual function. No change in placebo group. | FA | |

| ZVF study (2011) [39] | RCT | Early and moderate AMD retinopathy, symptoms of visual deficits. | 60 | Group 1: Z (8 mg) Group 2: Z (8 mg) + L (9 mg), Group 3: Placebo |

12 months | MPOD increased in the intervention groups compared to the placebo group | HFP | |

| Weigert (2011) [40] | RCT | Adults 50-90 years with AREDS stages 2, 3, and 4. | 126 | Group 1: L (20 mg for first 3 months, then 10 mg) Group 2: Placebo |

6 months | Lutein significantly increased MPOD by 27.9%. No significant effect on macular function or visual acuity. | HFP | |

| Sabour-Pickett (2014) [41] | RCT | Adults 50-79 years with early AMD. | 52 | Group 1: L (20 mg) and Z (2 mg) Group 2: MZ (10 mg), L (10 mg), Z (2 mg) Group 3: MZ (17 mg), L (3 mg), Z (2 mg) |

12 months | Statistically significant increase in MPOD was observed in Group 2 and Group 3. Improvements in letter contrast sensitivity were seen in all groups, with the best results in Group 3. | HFP | |

| Huang (2015) [42] | RCT | Adults 50-79 years with early AMD. | 112 | Group 1: L (10 mg) Group 2: L (20 mg) Group 3: L (10 mg) and Z (10 mg) |

2 years | All active treatment groups showed a significant increase in MPOD. The 20 mg lutein group was the most effective in increasing MPOD and contrast sensitivity at 3 cycles/degree for the first 48 weeks. | FA | |

| Davey (2020) [43] | RCT | Adults 50-79 years with retinal drusen. | 56 | Group 1: Lumega-Z softgel Group 2: PreserVision AREDS2 softgel |

6 months | Both groups demonstrated statistically significant improvements in contrast sensitivity function (CSF) in both eyes at six months. | HFP | |

| Ma (2012) [44] |

RCT | Ages 50-79, Early AMD. | 108 | Group 1: L (10 mg) Group 2: L (20 mg) Group 3: L (10 mg) plus Z (10 mg) |

48 weeks | Significant increase in MPOD in the high-dose lutein and lutein plus zeaxanthin groups, with improvements in contrast sensitivity at certain spatial frequencies. | FA | |

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Inclusion Criteria | Sample Size | Intervention(s) | Duration | Relation between MPOD and Glaucoma | MPOD Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fikret (2021) [55] |

CS | Age not mentioned. Patients with POAG, PEX and controls. | 79 | None | N/A | Higher MPOD values in patients with PEX glaucoma; no significant differences in POAG compared to controls. There was no correlation between MPOD values and RNFL or GCL. | FR |

| Bruns (2020) [56] |

CS | Adults 34-87 years; Patients with POAG and controls. | 86 | None | N/A | No significant difference in MPOD values between POAG patients and controls. | DWA |

| Loughman (2021) [57] | RCT | Adults >18 years. Patients with POAG and controls. | 62 | Group 1: L (10mg) + Z (2mg) + MZ (10mg). Group 2: Placebo. |

18 months | Supplementation led to a significant increase in MPOD volume. No clinically meaningful changes were noted in glaucoma parameters. | DWA |

| Siah (2015) [53] |

CS | Adults 36-84 years. Patients with POAG and controls. | 88 | None | N/A | Lower MPOD was observed in glaucomatous eyes compared to control. Worse glaucomatous parameters were observed in patients with lower MPOD. | HFP |

| Ji (2016) [58] |

CS | Adults 20-76 years. Patients with POAG and controls. | 82 | None | N/A | MPOD was significantly lower in POAG patients compared to controls, and correlated positively with GCC thickness. | FR |

| Arnould (2022) [59] | CS | Adults >75 years. Patients with POAG and controls. | 1153 | None | N/A | No significant differences in MPOD were found between the POAG group and the control group. | DWA |

| Daga (2018) [60] |

CS | Adults 20-76 years. Patients with POAG and controls. | 107 | None | N/A | No significant association was found between MPOD volume and glaucoma status. | DWA |

| Lawler (2023) [61] | CS | Adults 55-81 years. Patients with POAG and controls. | 379 | None | N/A | MPOD was positively associated with GCC, GCL, among POAG and controls. | HFP |

| Igras (2013) [62] |

CS | Adults 58-80 years. Patients with POAG and controls. | 40 | None | N/A | MPOD was significantly lower in POAG patients compared to controls. | HFP |

| Siah (2018) [63] |

CS | Adults 36-84 years. Patients with POAG and controls. | 88 | None | N/A | MPOD was associated with improved glare-affected visual function and less central visual field loss in POAG patients. | HFP |

| Eraslan (2023) [64] | CS | Adults >55 years. Patients with POAG currently receiving topical medication and controls. |

52 | None | N/A | MPOD levels were higher in POAG patients compared to controls, suggesting a possible protective effect of topical therapies. | FR |

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Inclusion Criteria | Sample Size | Intervention(s) | Duration | Relation between MPOD and DR | MPOD Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lima (2010) [69] | CS | Adults 56-63; BCVA ≤20/40. | 43 | None | N/A | MPOD was lower in diabetic patients, with significant inverse correlation with HbA1C levels. | DWA |

| Scanlon (2019) [70] | CS | Adults 50+; BCVA ≤20/40. | 2782 | None | N/A | MPOD was found to be lower in individuals with T2D compared to healthy controls. | HFP |

| Bikbov (2015) [71] | CS | Adults 55-71; BCVA ≤20/40. | 52 | None | N/A | Significant reduction of MPOD in patients with diabetic macular edema compared to controls. | FR |

| Scanlon (2015) [72] | CS | Adults 36-73; BCVA ≤20/25. | 150 | None | N/A | MPOD was significantly lower in T2D compared to T1D and controls. Diabetes control was not associated with MPOD. | HFP |

| She (2016) [73] | CS | Adults over 55-71; BCVA ≤20/25. | 401 | None | N/A | No significant difference in MPOD levels among groups with or without early-stage non-proliferative DR | HFP |

| Bikbov (2015) [74] | CS | Adults 54-69; BCVA ≤20/25. | 31 | None | N/A | Significant reduction of MPOD in DME patients, strong inverse correlation between retinal thickness and MPOD | FR |

| Chous (2016) [75] | RCT | Adults 43-69; BCVA ≥20/30; no or mild to moderate DR. | 67 | Group 1: Carotenoid supplement Group 2: placebo | 6 months | Supplemented group showed significant improvements in visual functions which correlated with increased MPOD compared to placebo | HFP |

| Zagers (2005) [76] | CS | Adults 23-61; BCVA ≤20/32. | 14 | None | N/A | No significant difference in MPOD density between diabetic patients and healthy controls. | FR |

| Varghese (2019) [77] | CS | Adults 49-54 years. | 150 | None | N/A | MPOD was similar across diabetic patients with and without DR, suggesting no significant difference due to DR. | FR |

| Cennamo (2019) [78] | CS | Adults 31-38 years; T1D and controls. | 59 | None | N/A | MPOD and vessel density were both significantly lower in diabetic patients compared to controls. Moderate correlation between vessel density and MPOD. | FR |

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Demographic | Sample Size | Interventions | Duration | Relation between MPOD and Visual Function | MPOD Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stringham (2011) [86] | CS | Adults 23-50; BCVA ≤20/25. | 26 | None | N/A | MPOD was associated with faster photo stress recovery, lower disability glare thresholds, and reduced visual discomfort. | HFP |

| Engles (2007) [91] | CS | Adults 18-40; BCVA ≤20/40. | 80 | None | N/A | No significant correlation found between MPOD and measures of visual acuity. | HFP |

| Tudosescu (2018) [92] | CS | Adults 18-65 years; BCVA ≤20/125. | 83 | None | N/A | No significant correlation between MPOD and blue-light exposure from computers, iris color, refractive errors, or glare sensibility was found. | HFP |

| Patryas (2014) [93] | CS | Adults 18-68 years; BCVA ≤20/32. | 33 | None | N/A | MPOD was weakly associated with rod-mediated recovery, not with cone-mediated recovery. | HFP |

| Bovier (2014) [94] | RCT | Adults 18-32 years; BCVA ≤20/60. | 92 | Group 1: Z - 20mg Group 2: Mixed (Z - 26mg, L - 8mg, Omega-3 - 190mg) Group 3: Placebo |

4 months | MPOD increased with supplementation and led to significant improvements in visual processing speed and motor reaction time. | HFP |

| Kvansakul – (2006) [95] | RCT | Adults 18-40 years; BCVA ≤20/60. | 92 | Group 1: L - 10mg Group 2: Z - 10mg Group 3: Combination (L - 10mg, Z - 10mg) Group 4: Placebo |

12 months | Supplementation with L or Z increases MPOD improved contrast acuity thresholds at high mesopic levels, thus enhancing visual performance at low illumination. | HFP |

| Putnam (2015) [96] | CS | Adults 18-35 years; BCVA ≤20/25. | 33 | None | N/A | Increased MPOD correlates with reduced glare disability, significantly at higher spatial frequencies. | HFP |

| Stringham (2008) [97] | RCT | Adults 17-41 years. | 40 | Group 1: L - 10mg, Z - 2mg Group 2: Placebo |

6 months | Supplementation led to increased MPOD, which significantly improved performance in glare disability and photostress recovery tasks. | HFP |

| Stringham (2017) [98] | RCT | Adults 18–25 years. | 59 | Group 1: L - 6mg and Z - 6mg Group 2: L - 12mg and Z - 12mg Group 3: Placebo |

12 months | Increases in MPOD led to improved contrast sensitivity | HFP |

| Nolan (2016) [99] | RCT | Adults with mean age of 21.5 years. | 105 | Group 1: L - 10 mg, Z - 2mg, and MZ - 10 mg Group 2: Placebo |

12 months | MPOD increased with supplementation and was significantly correlated with improvements in contrast sensitivity in the active group compared to placebo. | DWA |

| Hammond (2014) [100] | RCT | Adults 20-40 years. | 115 | Group 1: L - 10mg, Z - 2mg. Group 2: Placebo |

12 months | Supplementation increased MPOD significantly, improving chromatic contrast and photostress recovery time, but glare disability improvements were not statistically significant. | HFP |

| Hammond Jr (2013) [101] | CS | Adults 20-40 years. | 150 | None | N/A | MPOD density significantly correlated with positive outcomes in glare disability, photostress recovery time, and chromatic contrast thresholds. | HFP |

| Stringham (2016) [102] | RCT | Adults 18-25 years, BCVA ≤20/20. | 59 | Group 1: L - 10mg + Z - 2mg. Group 2: L - 20mg + Z - 4mg. Group 3: Placebo |

12 months | Supplementation led to significant increases in MPOD, which in turn resulted in improvements in photostress recovery, and disability glare. | HFP |

| Hammond Jr. (1998) [103] | CS | Adults 60-84 years; ≤20/32 visual acuity. | 37 | None | N/A | Higher MPOD was associated with preserved visual sensitivity in older ages. | HFP |

| Estévez-Santiago (2016) [104] | CS | Adults 20-35 and 45-65 years; BCVA ≤20/20. | 108 | None | N/A | Contrast threshold inversely correlated with MPOD, particularly in the older group. | HFP |

| Nolan (2011) [105] | RCT | Adults 18-41 years; BCVA ≤20/20. | 121 | Group 1: L - 12mg + Z - 1mg. Group 2: Placebo. |

12 months | Statistically significant increase in MPOD in the active group was not generally associated with improvement in visual performance. | HFP |

| Loughman (2010) [106] | CS | Adults 18-41 years; BCVA ≤20/20. | 142 | None | N/A | MPOD was positively associated with BCVA and contrast sensitivity, while photostress recovery and glare sensitivity were unrelated to MPOD. | HFP |

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Inclusion Criteria | Sample Size | Intervention(s) | Duration | Relation between MPOD and Cognitive Function | MPOD Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khan (2018) [112] | CS | Adults 25-45 years with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m². | 114 | None | N/A | MPOD positively associated with IQ and fluid intelligence, but not with crystallized intelligence | HFP |

| Saint (2018) [113] | CS | Children 7-13 years. | 51 | None | N/A | MPOD positively associated with reasoning skills and executive mental processes | HFP |

| Renzi-Hammond (2017) [114] | RCT | Adults 18-30 years. | 51 | Group 1: L (10mg) + MZ (2mg). Group 2: Placebo |

1 year | MPOD positively associated with improvements in spatial memory, reasoning ability, and complex attention tasks | HFP |

| Barnett (2018) [115] | CS | Preadolescent children 8-9 years. | 56 | None | N/A | MPOD positively associated with overall academic achievement, mathematics, and written language | HFP |

| Lindbergh (2018) [116] | RCT | Adults 64-86 years. | 44 | Group 1: L (10mg) + MZ (2mg). Group 2: Placebo |

1 year | L and Z supplementation increased MPOD and was associated with enhanced signals in prefrontal regions, suggesting a potential mechanism for improved cognitive performance | HFP |

| Kelly (2015) [117] | CS | Group 1: Adults 35-74 years with low MPOD, Group 2: Adults 35-74 years with early AMD. | 226 | None | N/A | MPOD positively associated with phonemic fluency, attention switching, visual and verbal memory, and learning | HFP and DWA |

| Power (2018) [118] | RCT | Adults 33-57 years with low MPOD. | 91 | Group 1: L (10mg) + MZ (10mg) + Z (2mg). Group 2: Placebo |

12 months | Supplementation improved MPOD which positively associated with episodic memory and overall cognitive function | DWA |

| Ajana (2018) [119] | CS | Adults 75-93 years with low MPOD. | 184 | None | N/A | Higher MPOD significantly associated with better global cognitive performance, visual memory, and verbal fluency | DWA |

| Vishwanathan (2014) [120] | CS | Adults 75-80 years. | 108 | None | N/A | MPOD levels significantly positively associated with better global cognition, verbal learning and fluency, recall, processing speed, and perceptual speed | HFP |

| Renzi (2014) [121] | CS | Adults 65-83 years with mild cognitive impairment. | 53 | None | N/A | In unimpaired adults, higher MPOD was associated with better visuospatial and constructional abilities. In mildly impaired adults, higher MPOD was associated with better performance in multiple cognitive domains including memory, language, and attention | HFP |

| Feeney (2013) [122] | CS | Adults 50+ years. | 4453 | None | N/A | Lower MPOD was associated with poorer performance on the MMSE and MoCA, prospective memory, and executive function | HFP |

| Stringham (2019) [123] | RCT | Adults 18-25 years. | 59 | Group 1: MZ (13 mg), Group 2: MZ (27 mg), Group 3: Placebo. |

6 months | Supplementation improved cognitive performance in composite memory, verbal memory, sustained attention, psychomotor speed, and processing speed | HFP |

| Hassevoort (2017) [124] | CS | Children 7-10 years. | 40 | None | N/A | MPOD negatively associated with relational memory errors | HFP |

| Edwards (2019) [125] | CS | Adults 25-45 years with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m². | 101 | None | N/A | MPOD positively associated with improvements attentional resource allocation and information processing speed | HFP |

| Mewborn (2018) [126] | CS | Adults 64-77 years. | 51 | None | N/A | Higher MPOD positively associated with better neural efficiency in visual–spatial processing | HFP |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).