1. Introduction

Gaining access to mental health care remains a global challenge owing to key factors including a lack of trained providers, costs, and societal stigma [

1,

2]. College students experience unique stressors such as academic pressure, social strain, and the transition to adulthood, which can challenge their resilience and mental clarity [

3]. Thus, stakeholders believe that timely and impactful mental health support is particularly important [

4]. Artificial intelligence (AI) technology, especially conversational AI such as ChatGPT, could become a potential solution for increasing access to mental health care, thus highlighting a possible path to providing equitable mental health care to all youth [

5,

6].

The capabilities and potential of AI have been demonstrated in several fields, such as education, medicine, and psychology where ChatGPT has shown its potential to advance progress [

7,

8,

9]. In mental health care, innovative advancements in AI have demonstrated promising solutions [

5]. Models such as ChatGPT that use conversational AI can help make mental health care accessible, immediate, and affordable by simulating a human-sounding conversation that provides emotional support and practical advice and by being accessible on demand at all times, providing an attractive option for youth mental health [

10,

11]. Previous research has also highlighted AI’s strengths and potential in providing or aiding in mental health assessment, detection, diagnosis, operation support, treatment, and counseling [

5,

12,

13]. A range of chatbots have been developed and tested by renowned scholars in the field, and researchers and policymakers are expected to demonstrate the effectiveness of AI chatbots in providing mental health care so that an answer to a significant problem can be found [

14,

15,

16].

However, the use of AI in psychological counseling is still in the preliminary stages, and important details and risk factors must be considered. The potential harm caused by AI psychotherapy poses a high risk [

17,

18]. Users’ trust in the quality and reliability of the responses they receive must be considered because inaccurate or misleading mental health advice could have negative effects on clients [

19,

20,

21]. Thus, quality assurance could be a vital issue if the responses provided are inaccurate or insensitive and could thus potentially harm users [

18,

22,

23]. AI interpretations could miss complex emotional nuances; therefore, one major concern is that AI simply cannot replicate the relationships and human connections that people enjoy with a trained human counselor [

14,

16,

24].

As a new technology, AI has obvious advantages and risks. Thus, the core question is how can AI best be utilized to increase mental health care accessibility and avoid potential risks, and how gradually can AI applications be integrated into various care contexts and populations. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the effectiveness of ChatGPT in providing counseling sessions to evaluate the current state of AI applications in mental care.

This simulation study was conducted in a school counseling setting to evaluate the efficacy of ChatGPT as an assistant in providing psychological counseling. Specifically, 80 counseling questions frequently asked by college students were shared with ChatGPT, and the answers were analyzed to investigate its capability to provide supportive and efficient mental health interventions [

25]. The analysis concentrated on three main metrics derived from the American Psychological Association’s (APA) benchmarks for effective counseling responses: (1) warmth, (2) empathy, and (3) acceptance [

26]. Warmth examines whether AI can create a context that is welcoming and supportive of students, empathy assesses whether AI can understand and mirror students’ feelings and experiences, and acceptance investigates if AI can demonstrate unconditional positive regard and a nonjudgmental attitude toward students [

26].

Using several natural language processing (NLP) approaches, including sentiment detection and empathy metric tools, this study aimed to quantitatively indicate the extent to which ChatGPT can provide warmth, empathy, and acceptance. The results of this study can add to the evolving understanding of AI technology as an essential tool in mental health care, while also offering insights into the targeted and practical implementation of AI for preventative school counseling. The Discussion section explores the findings and their implications on a broader scale, drawing on their potential to enhance students’ mental health and outlining the steps that must be taken to mitigate risks and ensure this technology is implemented safely and ethically. As the demand for accessible mental health services continues to grow, innovative and effective methods such as conversational AI should be proactively explored to address the mental health needs of diverse populations.

2. Literature Review

A thorough literature review was conducted to clarify the current state of applying AI in mental health care, identifying the key findings, core research questions, and debates in this arena. The mental health care sector is facing rising service requirements combined with greater acknowledgment of the importance of innovative solutions [

22]. The benefits and risks of AI have been demonstrated by experts in this field. Researchers have recognized that adopting AI tools in mental health services is not only futuristic but also a current reality that challenges traditional care practices and provides innovative strategies for diagnosing, treating, and supporting patients [

27]. Currently, several AI technologies are significantly advancing mental health care by improving diagnostic accuracy, enhancing treatment personalization, offering insights and recommendations to clinicians, tailoring services to individual needs, and providing accessible and cost-effective mental health support to wide groups of people [

22,

28,

29,

30]. AI chatbots such as “Hailey,” “Kooth,” “MYLO,” and “Limbic Access” are utilizing sophisticated NLP algorithms to deeply understand human language and initiate, respond, and engage in meaningful conversations related to users' wellness, thereby effectively generating mental health support and offering computerized therapies [

5,

10,

19,

27,

31].

Chatbots can identify human emotions and sentiments and assess psychological conditions to generate individualized support. Studies have shown that chatbots can effectively interact with users and quickly respond to their queries, with approximately 99% accuracy in measuring users' psychological states [

30,

32]. In a study conducted with Tess, a well-known mental health support chatbot, the experimental group demonstrated a 13% decline in symptoms of depression and anxiety, whereas the control group reported a 9% increase, demonstrating significantly high engagement and satisfaction with the intervention among university students [

14]. Moreover, ChatGPT has displayed significantly higher emotional awareness than human norms and demonstrated the ability to provide useful intervention for low- and medium-risk conditions, ensuring safety [

11,

33]. This indicates that ChatGPT has the ability not only to generate supportive responses but also to accurately identify and describe emotional states, further reinforcing its potential utility in therapeutic contexts.

However, serious concerns exist regarding the potential harm caused by technological malfunctions and misinterpretations [

13,

22,

34]. Without human intervention, malfunctions such as overdue or faulty responses caused by system errors, misdiagnosis, and faulty behavioral or treatment advice could potentially lead to serious clinical harm [

13,

18,

22,

33]. Moreover, owing to the standardized functions of AI, it has difficulties understanding and interpreting nuanced human expressions, emotions, health conditions, and demographic information, which makes the accuracy and precision of treatment and support less effective or potentially biased [

18,

35,

36].

Research on the benefits and risks associated with ChatGPT and other AI technology’ has underscored the call for further research to determine the strengths and limitations of applying this new technology in mental health care. Researchers have highlighted that altering and repeating prompts can result in different responses, some of which are even harmful responses [

37]. In addition, biases in AI algorithms may perpetuate or exacerbate existing societal biases, leading to certain patient groups receiving unequal or unfair treatment [

19,

20]. Another study concluded that an increase in context complexity can lead to worse results, making ChatGPT not yet suitable for use in mental health interventions [

38]. Thus, the current literature indicates promising outputs for this new intersecting area while also emphasizing the need to further evaluate ChatGPT’s capabilities and how it can best be utilized to maximize its social value.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design

Because this study aimed to measure the performance of ChatGPT and similar large language model (LLM)-based chatbots in the psychological counseling context, the data should come from real-life simulations. Therefore, we first identified a data source consisting of several authentic counseling questions. Then, we decided which LLM to use to obtain responses for our analyses. We ultimately selected ChatGPT-4 because it was the most universally recognized LLM at the time this study was conducted. Using ChatGPT’s online application, we collected three responses for each question [

39]. After we collected all the data from ChatGPT’s responses, our analysis focused on evaluating how well they conveyed warmth, empathy, and acceptance. Another vital aspect is determining the randomness level of the ChatGPT responses to the same question. In the analysis, we utilized NLP techniques for our evaluation.

3.2. Rationale of Methodology

A significant barrier to applying AI in mental health care is that AI cannot replace real human emotions and empathy disclosure, which are crucial in providing quality mental health interventions [

24,

40,

41]. Thus, this study aimed to quantify the basic performance of demonstrating the necessary emotions during the AI counseling process. According to the APA, effective therapists have a diverse set of interpersonal skills including verbal fluency, warmth, acceptance, empathy, and the ability to identify how a patient is feeling [

26]. Because verbal fluency is not an issue in the AI’s response and is not relevant to our evaluation of emotional nuances, we excluded verbal fluency as a metric [

42]. Furthermore, accuracy in identifying how a patient is feeling can be difficult to define [

43]. Therefore, we defined warmth, empathy, and acceptance as the three key metrics and used respective NLP algorithms to quantify the results. Besides, a serious concern is about AI’s accuracy and stability. Without human oversight, AI chatbots might cause severe harm to users [

19,

22,

44,

45]. Therefore, attention to randomness is necessary when considering the use of AI chatbots in a clinical context. These methodologies provide a comprehensive approach to evaluating ChatGPT’s performance in delivering emotionally supportive and stable responses, contributing to the understanding of its potential application in psychological counseling.

3.3. Data Collection

The secondary data come from research on ChatCounselor [

25], in which researchers use real-world counseling data to train an AI counselor, which is open-source for researching AI’s capabilities in personalized psychological counseling. Therefore, we believe that this data source was suitable for our evaluation. The dataset used in this study consists of a diverse set of queries related to adolescent psychological issues, originally collected in Chinese and translated into English. This set comprises queries from 80 different students and spans topics such as academic stress, family, and intimate relationships. The large variation in the topics, tones, and lengths of these queries makes our data meaningful for testing the stability of ChatGPT’s performance. The dataset includes the following columns: original query in Chinese, translated query in English, and three responses to the translated query generated by the AI.

To ensure the quality of ChatGPT’s responses, the following prompt was adopted to make GPT-4’s responses as close as possible to real counseling sessions: “Imagine you are a counselor, and you need to give a response just as in a counseling session. You need to give a response in the same format as a professional counselor. According to the APA, an effective therapist has abilities including verbal fluency, warmth, acceptance, empathy, and an ability to identify how a patient is feeling.” Then, a query from the dataset was added to the prompt to provide ChatGPT. The prompt-based design was to ensure that the key context and expectations were provided, thereby making the evaluation more objective.

3.4. Warmth (Emotion Detection)

To detect emotions in the GPT responses, we utilized the EmoRoBERTa model [

46], a pre-trained transformer-based model capable of identifying 28 distinct emotions: admiration, amusement, anger, annoyance, approval, caring, confusion, curiosity, desire, disappointment, disapproval, disgust, embarrassment, excitement, fear, gratitude, grief, joy, love, nervousness, optimism, pride, realization, relief, remorse, sadness, surprise, and neutrality. The EmoRoBERTa model was applied to each response to classify the primary emotion. We utilize the EmoRoBERTa model to identify whether the responses conveyed emotional warmth. This well-established model has been cited in several studies for its robustness in emotion detection [

47].

3.5. Empathy (Empathy Detection)

Given the focus on adolescent psychological issues, assessing the responses for the presence of empathy was crucial [

48]. Based on research on empathy in text-based mental health support, a neural network model was trained to detect empathy in text [

49]. The model was trained using a dataset of empathetic and non-empathetic text, allowing it to distinguish whether a response contains empathetic language. The model outputs a binary label: 1 for responses that contain empathy and 0 for those that do not. We adopted this model to measure the levels of empathy in ChatGPT’s responses. The code for training and applying this neural network model is available publicly [

49].

3.6. Acceptance (Sentiment Analysis)

To quantitatively assess whether ChatGPT demonstrates acceptance in each response, we conducted sentiment analysis using the valence-aware dictionary and sEntiment Reasoner (VADER) model [

50]. This pre-trained model outputs four scores: negative (

neg), neutral (

neu), positive (

pos), and a comprehensive sentiment score (

compound). These scores offer detailed insight into the sentiments expressed in each response, with the compound score specifically used to evaluate the overall emotional tone. The higher the positive score, the higher the level of acceptance in the response.

3.7. Stability and Consistency Evaluation

To evaluate the stability and consistency of ChatGPT’s responses, we used the Kappa score for empathy detection and analyzed the variance in compound sentiment scores across three responses per query. Additionally, we conducted a chi-square test for independence to determine if there were significant differences in emotion category distribution across the three responses. We also performed a one-way ANOVA to assess the differences in the average composite sentiment scores among the three responses.

3.8. Correlation Analysis

We examined the relationship between the word count of the queries and the word count of the responses. We calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient to determine the strength of the relationship between the question word count and the average answer word count [

51]. The correlation analysis aimed to identify if longer questions tend to elicit longer responses from GPT.

3.9. Ethical Considerations

This study did not involve any direct interactions with human or animal subjects. The data were anonymized and made publicly available to ensure compliance with ethical standards. Ethical approval was not required for this study.

All materials, data, computer codes, and protocols associated with this study are available to readers. For further details on the methodologies and protocols used, please refer to the Supplementary Materials.

4. Results

4.1. Warmth (Emotion Detection)

We employed the EmoRoBERTa model to analyze the emotional responses generated by the GPT system to address questions from adolescents. These responses were scrutinized for emotional content and subsequently categorized into four primary emotion types: approval, caring, confusion, and realization. The quantitative breakdown of these emotions across all responses is presented below.

Table 1.

Distribution of detected emotions.

Table 1.

Distribution of detected emotions.

| Emotion Category |

Answer1 |

Answer2 |

Answer3 |

Total |

Proportion |

Frequency |

| Approval |

14 |

21 |

18 |

53 |

22.08% |

Moderate |

| Caring |

64 |

57 |

60 |

181 |

75.42% |

Very High |

| Realization |

1 |

1 |

2 |

4 |

1.67% |

Very Low |

| Confusion |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0.83% |

Very Low |

Our findings indicate a predominance of supportive and empathetic emotions (approval and caring), suggesting that GPT-generated responses typically foster a nurturing dialogue environment. Conversely, emotions indicative of uncertainty or misapprehension (confusion and realization) were infrequent, underscoring the clarity and decisiveness of the responses. Combining the categories of approval and caring, 97.5% of GPT-generated responses demonstrated warmth.

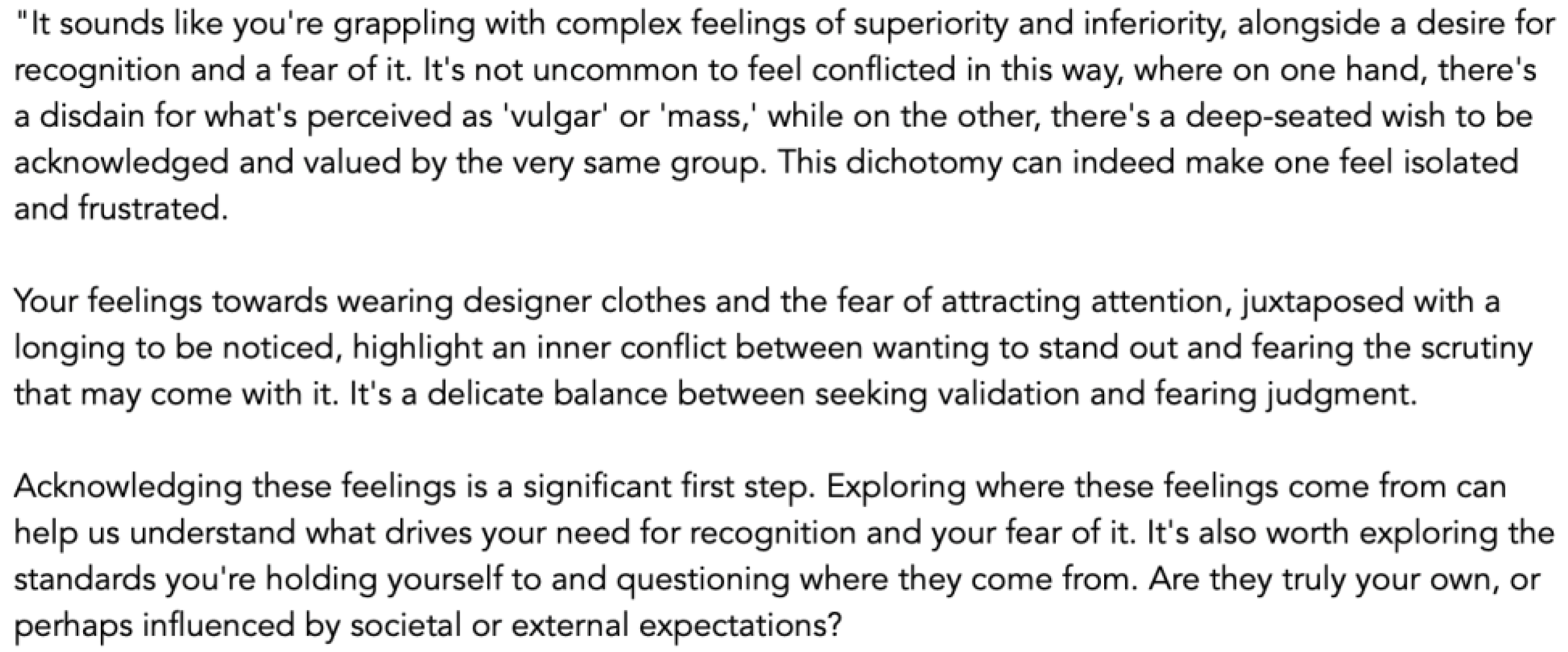

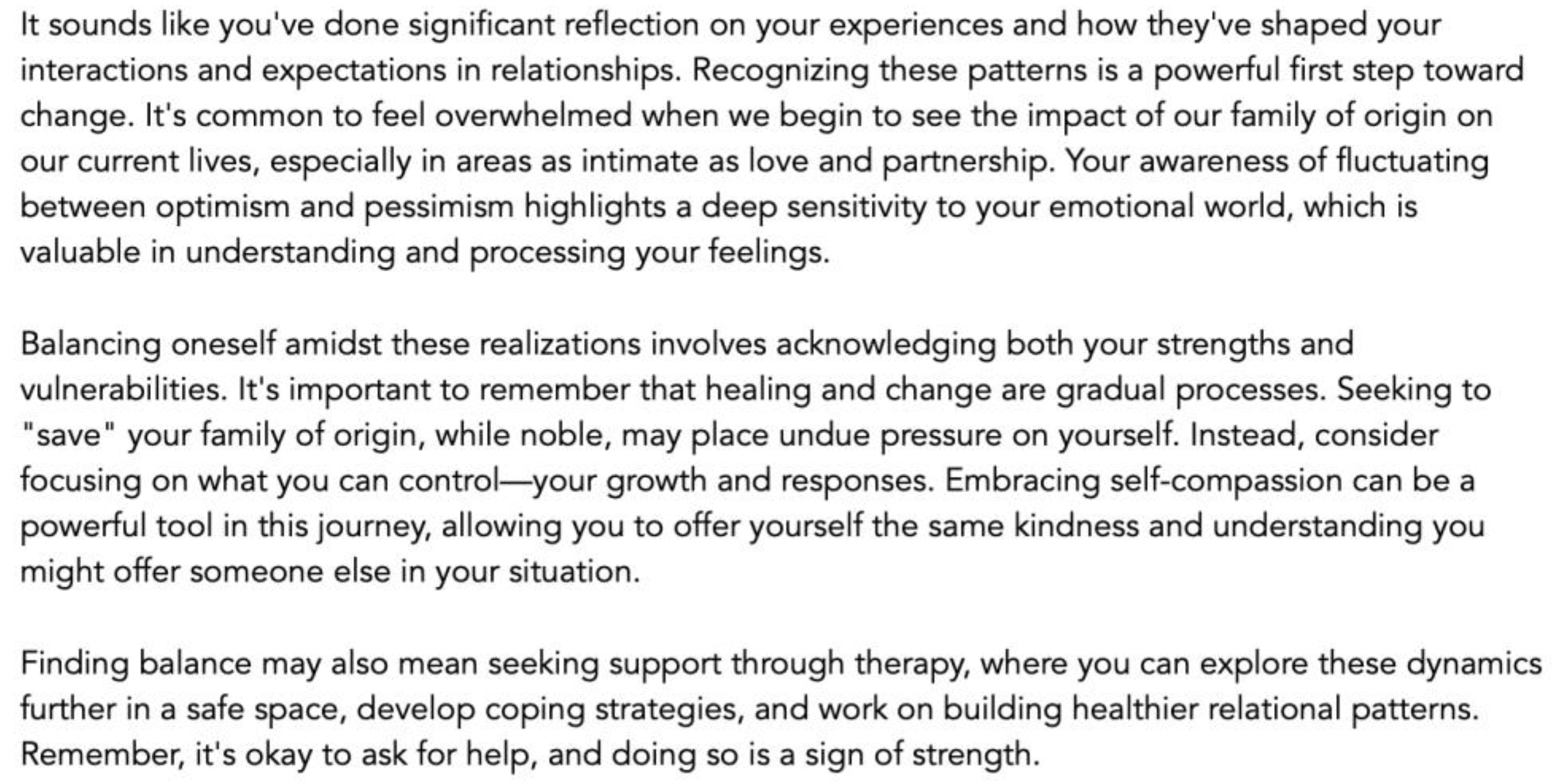

However, the low probability occurrence of confusing emotions (confusion and realization) is also notable because any mistake in psychological counseling can cause unforeseeable harm. The results indicate that obvious randomness remains present in the process, highlighting the need for caution in using AI chatbots in high-risk mental health interventions. Two abnormal responses are presented below.

Figure 1.

The GPT’s response identified as ‘Confusion’.

Figure 1.

The GPT’s response identified as ‘Confusion’.

Figure 2.

The GPT’s response identified as ‘Realization’.

Figure 2.

The GPT’s response identified as ‘Realization’.

4.2. Empathy (Empathy Detection)

We utilized a sophisticated neural network model trained explicitly to recognize empathetic expressions in text. This model classified each response based on whether it contained empathy. The classification results are as follows:

Table 2.

Distribution of detected empathy.

Table 2.

Distribution of detected empathy.

| Empathy Detection |

Answer1 |

Answer2 |

Answer3 |

Frequency |

Percentage |

| Empathy (1) |

76 |

75 |

75 |

226 |

94.17% |

| No Empathy (0) |

4 |

5 |

5 |

14 |

5.83% |

These results highlight the significant prevalence of empathy in the responses, demonstrating GPT's ability to effectively empathize with adolescent users in a psychologically astute manner.

4.3. Acceptance (Sentiment Analysis)

To further examine the emotional landscape of the responses, we conducted a comprehensive sentiment analysis. This analysis categorized the sentiments expressed in each response into four groups: negative, neutral, positive, and compound (an aggregate measure of the overall sentiment tone). The average sentiment scores across all responses were computed as follows:

Table 3.

Distribution of acceptance level.

Table 3.

Distribution of acceptance level.

| Sentiment Type |

Answer1 Mean |

Answer2 Mean |

Answer3 Mean |

Total Mean |

| Negative (neg) |

0.056 |

0.055 |

0.061 |

0.057 |

| Neutral (neu) |

0.733 |

0.735 |

0.730 |

0.733 |

| Positive (pos) |

0.210 |

0.208 |

0.209 |

0.208 |

| Compound |

0.902 |

0.939 |

0.945 |

0.929 |

The results suggest an overwhelmingly positive emotional undertone in the GPT responses, with high compound scores reflecting an overall affirmative feedback strategy. This analysis indicates that GPT responses generally promote a supportive and reassuring interaction framework, highlighting a promising level of acceptance shown.

4.4. Stability of Responses

To assess the reliability and consistency of the emotional responses, we utilized the Kappa score for empathy detection and analyzed the variance in compound sentiment scores across three responses per query, as described below.

Empathy Detection Stability: A Kappa score of 0.59 indicates a substantial level of agreement and consistency in the empathetic quality of the responses.

Compound Score Stability: The minor mean difference (0.067) and low standard deviation (0.196) in the compound scores suggest that the emotional tone of GPT’s responses was remarkably stable, showing only minor fluctuations in positivity across different responses to the same query.

These detailed sentiment data provide profound insights into the consistency and reliability of emotional responses, demonstrating the general robustness of GPT's interactions with adolescent users. The agreement and consistency levels were clear; however, concerns still need to be addressed regarding whether this level is acceptable in clinical settings.

4.5. Chi-Square Test for Emotion Category Distribution

We conducted a chi-square test for independence to determine if there were significant differences in emotion category distribution across the three responses. The chi-square statistic was 3.3050661940998642, with a p-value of 0.7696977961905502, indicating no significant differences in emotion category distribution across the responses.

4.6. One-Way ANOVA for Composite Sentiment Scores

We performed a one-way ANOVA to assess the differences in the average composite sentiment scores among the three responses. The F statistic was 0.5761785169211049, with a p-value of 0.5628273973833389, suggesting no significant differences in the average composite sentiment scores among the three responses.

4.7. Correlation between Question and Answer Word Count

To explore the factor influencing the randomness of GPT’s output, we made an analysis of the word count consistency. We examined the relationship between the word count of the questions we provided and the answers provided by GPT, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient. The results indicated a moderate positive correlation between the question word count and the average answer word count, with a correlation coefficient of 0.60. This suggests that longer questions tend to elicit longer responses from GPT. This emphasizes the content of GPT’s output can be varied for various reasons, further research should be conducted to measure the factors contributing to the randomness of GPT’s output.

Table 4.

Detailed Sentiment Data.

Table 4.

Detailed Sentiment Data.

| Metric |

Response 1 |

Response 2 |

Response 3 |

| Count |

80 |

80 |

80 |

| Mean (neg) |

0.056163 |

0.055375 |

0.061113 |

| Std (neg) |

0.035743 |

0.036379 |

0.032554 |

| Min (neg) |

0.000000 |

0.000000 |

0.000000 |

| 25% (neg) |

0.032750 |

0.031750 |

0.042500 |

| 50% (neg) |

0.048000 |

0.046000 |

0.056500 |

| 75% (neg) |

0.071250 |

0.076250 |

0.078250 |

| Max (neg) |

0.205000 |

0.233000 |

0.152000 |

| Mean (neu) |

0.733113 |

0.735750 |

0.730000 |

| Std (neu) |

0.049358 |

0.049851 |

0.044393 |

| Min (neu) |

0.531000 |

0.556000 |

0.611000 |

| 25% (neu) |

0.709750 |

0.707500 |

0.703000 |

| 50% (neu) |

0.739000 |

0.735500 |

0.731000 |

| 75% (neu) |

0.767250 |

0.766500 |

0.763500 |

| Max (neu) |

0.822000 |

0.831000 |

0.820000 |

| Mean (pos) |

0.210800 |

0.208788 |

0.208800 |

| Std (pos) |

0.055452 |

0.053547 |

0.045764 |

| Min (pos) |

0.105000 |

0.086000 |

0.113000 |

| 25% (pos) |

0.174250 |

0.175000 |

0.181750 |

| 50% (pos) |

0.207500 |

0.208000 |

0.205500 |

| 75% (pos) |

0.233000 |

0.243000 |

0.232500 |

| Max (pos) |

0.446000 |

0.420000 |

0.345000 |

| Mean (compound) |

0.902072 |

0.939741 |

0.944774 |

| Std (compound) |

0.353252 |

0.228432 |

0.189757 |

| Min (compound) |

-0.947800 |

-0.992200 |

-0.648600 |

| 25% (compound) |

0.972950 |

0.969475 |

0.969875 |

| 50% (compound) |

0.988500 |

0.987000 |

0.987000 |

| 75% (compound) |

0.992650 |

0.992850 |

0.992150 |

| Max (compound) |

0.998200 |

0.998600 |

0.998200 |

4.8. Summary

The application of GPT in the field of psychological counseling shows significant promise, primarily because of the overwhelmingly positive nature of the responses generated. Most GPT outputs are empathetic and supportive, which are critical attributes in therapeutic settings. Positive interactions in therapy are known to enhance client engagement and satisfaction, thereby contributing to more effective therapeutic alliances and outcomes. However, it is important to acknowledge that GPT also produces non-positive and even confusing responses in certain instances, indicating some issues with the stability and reliability of its outputs.

The randomness and occasional inconsistency highlight the need for further refinement. Enhancing the algorithm’s ability to maintain consistent emotional tones across multiple responses and ensuring the accuracy and reliability of its outputs is crucial for its application in high-risk mental health interventions.

5. Discussion

5.1. High Potential in Intervention

These results highlight the huge potential for ChatGPT as an intervention in mental health, especially in school counseling settings where these students have high-frequent mental needs. ChatGPT’s ability to provide responses rich with warmth, empathy, and acceptance strongly indicates its potential to provide a nurturing and supportive environment in which students can thrive. At a time when schools are demanding accessibility of mental healthcare services, harnessing ChatGPT could provide timely interventions with the potential to prevent critical mental health issues and improve students’ well-being. It is feasible that ChatGPT or similar applications can be used in emotional support chatbots, peer support, and social-emotional learning. Nevertheless, this continuous refinement should be carried out to maintain the degree of consistency and reliability to ensure the safety and efficacy of any psychological intervention. Future research should focus on refining these AI tools to better understand and respond to the nuanced emotional needs of students, ensuring that the integration of AI in mental health care is both safe and beneficial.

5.2. Randomness and Instability

Our research found obvious randomness and instability across responses. This could be due to variations in the query or the prompt used for GPT. In addition, the model itself showed inconsistencies when generating responses, with variations in tone and length. The presence of non-positive responses, although not predominant, raises concerns, especially when considering the application of GPT for clients with mental health vulnerabilities. Negative and non-empathetic feedback in therapeutic contexts, if not carefully managed, can exacerbate feelings of low self-esteem and anxiety, potentially leading clients to withdraw from therapy. Moreover, confusing responses are extremely dangerous from a clinical perspective and may intensify the client’s symptoms.

Therefore, while the potential for integrating GPT in therapeutic settings is high, owing to its capacity to deliver supportive and empathetic responses, there is a critical need to address instances of different types of problematic outputs. Ensuring that AI systems such as ChatGPT can reliably provide responses that align with therapeutic best practices is essential for their successful application in mental health services. Future developments should focus on enhancing the algorithm’s ability to discern and adapt to the clients’ nuanced emotional states, thereby ensuring stability and positivity in all interactions.

5.3. Technological Implications

Our study demonstrated that LLMs can have remarkable performance in delivering high-quality mental health support. However, randomness and instability in the responses also emphasized the immaturity in directly using ChatGPT in mental health interventions, particularly for users with clinical symptoms. Several technological approaches can prevent these risks to a certain extent. A multiagent model can be designed to bypass the limitations of each AI application, in which an AI agent can be designed to evaluate the performance of each response before the chatbot sends its response [

52]. This process is similar to that in our study, as we could evaluate whether a response satisfies our expectations of positivity and empathy. If the response fails to satisfy our predefined benchmark, it will ask the counseling AI agent to regenerate [

53,

54]. Another AI agent could also be designed to evaluate a client’s concurrent risk level. If it identified a client presenting a risk level higher than the benchmark, it could automatically refer the client’s information to human counselors for immediate clinical intervention. Along with the continuous advancement in technology and human-computer interactions, various approaches can be developed to further improve the real-life performance of AI in mental health care.

5.4. Utilization in General Support

Considering its current capabilities and limitations, ChatGPT and similar chatbots are best used for general mental health support and prevention rather than high-risk clinical interventions. For example, in the school context, it has been proposed that schools first make AI applications available for students without any diagnosed mental disorders, allowing them to largely contribute to students’ overall well-being. Effective early interventions could foreseeably prevent the occurrence of mental health disorders among students.

The combination of AI chatbots and mobile health applications with wearable devices could provide opportunities for continuous monitoring and real-time personalized feedback, thus improving preventive care [

55]. Utilizing these low-cost and widely applied AI applications, mental health prevention can be conducted at a large organizational or societal level and designed to adapt to a specific population's needs, such as customized AI chatbots for young people. If AI applications could reduce depression and anxiety symptoms, the number of patients requiring traditional mental health facilities could be reduced, thus contributing to global mental health care.

5.5. Organizational Oversight

ChatGPT and AI models’ high potential in mental health intervention of young people is obvious. Therefore, how the organizations can maximize its benefits at the application level and successfully improve the students’ well-being would be the key consideration. The goal can be simply defined as ‘maximize the benefits and minimize the risks.’ Besides concentrating on using AI in mental health support and intervention, organizations such as schools and colleges can focus on overseeing the service procedure and quality assurance during the process to improve the effectiveness of mental health intervention and the utilization efficiency of AI. By using protocols for continuous review and assessment of AI responses, human supervisors can timely correct any inaccuracies or inconsistencies that might arise. In this way, the AI can remain built to standards of empathy, warmth, and acceptance. In sum, human oversight can facilitate the integration of AI tools with traditional counseling services, creating a hybrid model that leverages the strengths of both. If organizations would like to utilize AI in mental health intervention, it is crucial to understand its limitations and create a product roadmap, financial budgeting, and human resources training, to make the AI services blend into the traditional psychological services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.N.; methodology, Y.N., Y.C.; software, Y.C.; validation, Y.N.; formal analysis, Y.C., Y.N..; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.N., Y.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.N.; visualization, Y.C., Y.N.; project administration, Y.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hidaka, B. H. Depression as a Disease of Modernity: Explanations for Increasing Prevalence. Journal of Affective Disorders 2012, 140, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombs, N. C.; Meriwether, W. E.; Caringi, J.; Newcomer, S. R. Barriers to Healthcare Access among U.S. Adults with Mental Health Challenges: A Population-Based Study. SSM Popul Health 2021, 15, 100847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoe, M. C.; Hetrick, S. E.; Parker, A. G. The Impact of Stress on Students in Secondary School and Higher Education. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Hunt, J.; Speer, N. Mental Health in American Colleges and Universities: Variation across Student Subgroups and across Campuses. J Nerv Ment Dis 2013, 201, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollwage, M.; Habicht, J.; Juechems, K.; Carrington, B.; Stylianou, M.; Hauser, T. U.; Harper, R. Using Conversational AI to Facilitate Mental Health Assessments and Improve Clinical Efficiency Within Psychotherapy Services: Real-World Observational Study. JMIR AI 2023, 2, e44358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alfonso, S. AI in Mental Health. Current Opinion in Psychology 2020, 36, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeshola, I.; Adepoju, A. P. The Opportunities and Challenges of ChatGPT in Education. Interactive Learning Environments 2023, 0, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S. S. Role of Chat GPT in Public Health. Ann Biomed Eng 2023, 51, 868–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, W.; Gao, R.; Wu, Y.; Tao, J.; Su, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Jia, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Huang, J.; Qiu, J.; Xu, Y. Efficacy of Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Psychotherapy in Patients With Anxiety Disorders: A Prospective, National Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2022, 12, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levkovich, I.; Elyoseph, Z. Identifying Depression and Its Determinants upon Initiating Treatment: ChatGPT versus Primary Care Physicians. Fam Med Com Health 2023, 11, e002391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elyoseph, Z.; Hadar-Shoval, D.; Asraf, K.; Lvovsky, M. ChatGPT Outperforms Humans in Emotional Awareness Evaluations. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1199058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danieli, M.; Ciulli, T.; Mousavi, S. M.; Silvestri, G.; Barbato, S.; Natale, L. D.; Riccardi, G. Assessing the Impact of Conversational Artificial Intelligence in the Treatment of Stress and Anxiety in Aging Adults: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mental Health 2022, 9, e38067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trappey, A. J. C.; Lin, A. P. C.; Hsu, K. Y. K.; Trappey, C. V.; Tu, K. L. K. Development of an Empathy-Centric Counseling Chatbot System Capable of Sentimental Dialogue Analysis. Processes 2022, 10, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulmer, R.; Joerin, A.; Gentile, B.; Lakerink, L.; Rauws, M. Using Psychological Artificial Intelligence (Tess) to Relieve Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Ment Health 2018, 5, e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, K. AI Mental Health Therapist Chatbot. International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology 2023, null, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichele, E.; Lavorgna, A.; Middleton, S. Identifying Key Challenges and Needs in Digital Mental Health Moderation Practices Supporting Users Exhibiting Risk Behaviours to Develop Responsible AI Tools: The Case Study of Kooth. Sn Social Sciences 2022, 2, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdoun, S.; Monteleone, R.; Bookman, T.; Michael, K. AI-Based and Digital Mental Health Apps: Balancing Need and Risk. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 2023, 42, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, T.; Tao, X.; Higgins, N.; Xie, H.; Gururajan, R.; Zhou, X. AI Enabled RPM for Mental Health Facility. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM Workshop on Mobile and Wireless Sensing for Smart Healthcare; 2022; pp. 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Lin, I. W.; Miner, A. S.; Atkins, D. C.; Althoff, T. Human-AI Collaboration Enables More Empathic Conversations in Text-Based Peer-to-Peer Mental Health Support. arXiv March 28, 2022. http://arxiv.org/abs/2203.15144 (accessed 2024-02-12).

- Tutun, S.; Johnson, M. E.; Ahmed, A.; Albizri, A.; Irgil, S.; Yesilkaya, I.; Ucar, E. N.; Sengun, T.; Harfouche, A. An AI-Based Decision Support System for Predicting Mental Health Disorders. Inf Syst Front 2023, 25, 1261–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Shen, K.; Wang, R.; Miao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Hwang, K.; Hao, Y.; Tao, G.; Hu, L.; Liu, Z. Negative Information Measurement at AI Edge: A New Perspective for Mental Health Monitoring. ACM Transactions on Internet Technology (TOIT) 2022, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Goel, S. Applications of Coversational AI in Mental Health: A Survey. In 2022 6th International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI); IEEE: Tirunelveli, India, 2022; pp 1013–1016. [CrossRef]

- Trappey, A.; Lin, A. P. C.; Hsu, K. K.; Trappey, C.; Tu, K. L. K. Development of an Empathy-Centric Counseling Chatbot System Capable of Sentimental Dialogue Analysis. Processes 2022, null, null. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, R. An Empathetic AI for Mental Health Intervention: Conceptualizing and Examining Artificial Empathy. In Proceedings of the 2nd Empathy-Centric Design Workshop; ACM; 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. M.; Li, D.; Cao, H.; Ren, T.; Liao, Z.; Wu, J. ChatCounselor: A Large Language Models for Mental Health Support. ArXiv 2023, abs/2309.15461, null. [CrossRef]

- The therapist effect. https://www.apa.org. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/02/therapist (accessed 2024-07-02).

- Rollwage, M.; Juchems, K.; Habicht, J.; Carrington, B.; Hauser, T.; Harper, R. Conversational AI Facilitates Mental Health Assessments and Is Associated with Improved Recovery Rates.

- Hadar-Shoval, D.; Elyoseph, Z.; Lvovsky, M. The Plasticity of ChatGPT’s Mentalizing Abilities: Personalization for Personality Structures. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1234397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moilanen, J.; Visuri, A.; Suryanarayana, S. A.; Alorwu, A.; Yatani, K.; Hosio, S. Measuring the Effect of Mental Health Chatbot Personality on User Engagement. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia; ACM: Lisbon Portugal, 2022; pp. 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulya, S.; Pragathi, T. R. Mental Health Assist and Diagnosis Conversational Interface Using Logistic Regression Model for Emotion and Sentiment Analysis. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2022, 2161, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrightson-Hester, A.-R.; Anderson, G.; Dunstan, J.; McEvoy, P. M.; Sutton, C. J.; Myers, B.; Egan, S.; Tai, S.; Johnston-Hollitt, M.; Chen, W.; Gedeon, T.; Mansell, W. An Artificial Therapist (Manage Your Life Online) to Support the Mental Health of Youth: Co-Design and Case Series. JMIR Hum Factors 2023, 10, e46849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, F.; Singh, R. P.; Satish, D. A Keras Functional Conversational AI Agent for Psychological Condition Analysis. IJRASET 2023, 11, 1171–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heston, T. F. Safety of Large Language Models in Addressing Depression. Cureus 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heston, T. F. Safety of Large Language Models in Addressing Depression. Cureus 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollwage, M.; Juchems, K.; Habicht, J.; Carrington, B.; Hauser, T.; Harper, R. Conversational AI Facilitates Mental Health Assessments and Is Associated with Improved Recovery Rates; preprint; Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rathnayaka, P.; Mills, N.; Burnett, D.; De Silva, D.; Alahakoon, D.; Gray, R. A Mental Health Chatbot with Cognitive Skills for Personalised Behavioural Activation and Remote Health Monitoring. Sensors 2022, 22, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhat, F. ChatGPT as a Complementary Mental Health Resource: A Boon or a Bane. Ann Biomed Eng 2024, 52, 1111–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dergaa, I.; Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Hallit, S.; Loch, A. A.; Glenn, J. M.; Fessi, M. S.; Ben Aissa, M.; Souissi, N.; Guelmami, N.; Swed, S.; El Omri, A.; Bragazzi, N. L.; Ben Saad, H. ChatGPT Is Not Ready yet for Use in Providing Mental Health Assessment and Interventions. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T. B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Agarwal, S.; Herbert-Voss, A.; Krueger, G.; Henighan, T.; Child, R.; Ramesh, A.; Ziegler, D. M.; Wu, J.; Winter, C.; Hesse, C.; Chen, M.; Sigler, E.; Litwin, M.; Gray, S.; Chess, B.; Clark, J.; Berner, C.; McCandlish, S.; Radford, A.; Sutskever, I.; Amodei, D. Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners. arXiv July 22, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Maurya, R. K. A Qualitative Content Analysis of ChatGPT’s Client Simulation Role-Play for Practising Counselling Skills. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research n/a (n/a). [CrossRef]

- Morris, R. R.; Kouddous, K.; Kshirsagar, R.; Schueller, S. M. Towards an Artificially Empathic Conversational Agent for Mental Health Applications: System Design and User Perceptions. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2018, 20, e10148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sass, K.; Fetz, K.; Oetken, S.; Habel, U.; Heim, S. Emotional Verbal Fluency: A New Task on Emotion and Executive Function Interaction. Behavioral Sciences 2013, 3, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalçın, Ö. N.; DiPaola, S. Modeling Empathy: Building a Link between Affective and Cognitive Processes. Artif Intell Rev 2020, 53, 2983–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secinaro, S.; Calandra, D.; Secinaro, A.; Muthurangu, V.; Biancone, P. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare: A Structured Literature Review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2021, 21, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thieme, A.; Hanratty, M.; Lyons, M.; Palacios, J.; Marques, R. F.; Morrison, C.; Doherty, G. Designing Human-Centered AI for Mental Health: Developing Clinically Relevant Applications for Online CBT Treatment. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2023, 30, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, R.; Ghoshal, A.; Eswaran, S.; Honnavalli, P. An Enhanced Context-Based Emotion Detection Model Using RoBERTa; 2022; p 6. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Vossen, P. EmoBERTa: Speaker-Aware Emotion Recognition in Conversation with RoBERTa. arXiv August 26, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Portt, E.; Person, S.; Person, B.; Rawana, E.; Brownlee, K. Empathy and Positive Aspects of Adolescent Peer Relationships: A Scoping Review. J Child Fam Stud 2020, 29, 2416–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Miner, A. S.; Atkins, D. C.; Althoff, T. A Computational Approach to Understanding Empathy Expressed in Text-Based Mental Health Support. arXiv September 17, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hutto, C.; Gilbert, E. VADER: A Parsimonious Rule-Based Model for Sentiment Analysis of Social Media Text. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 2014, 8, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient. Encyclopedia of Public Health; Kirch, W., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2008; pp. 1090–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Chang, R.; Pei, S.; Chawla, N. V.; Wiest, O.; Zhang, X. Large Language Model Based Multi-Agents: A Survey of Progress and Challenges. arXiv April 18, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gronauer, S.; Diepold, K. Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. Artif Intell Rev 2022, 55, 895–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mökander, J.; Schuett, J.; Kirk, H. R.; Floridi, L. Auditing Large Language Models: A Three-Layered Approach. AI Ethics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.; Bidargaddi, N. Commonly Available Activity Tracker Apps and Wearables as a Mental Health Outcome Indicator: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study among Young Adults with Psychological Distress. Journal of Affective Disorders 2018, 236, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).