1. Introduction

Coffee shops are often portrayed as one of the world’s most successful retail food outlets, but this is not the case for the least developed country we now know as Myanmar, which was once named Burma (until 1989) in Southeast Asia

1. Instead,

lahpet-ye-hsain, known as a “tea shop” or teahouse, is the most successful retail food outlet.

Tea shops in Myanmar consist of various establishments that serve tea and food at different times of the day for other clients. They can be small snacks, large open-aired, or covered restaurants with extensive menus (Constant, Oosterhoff, Oo, Lay, and Aung 2020). Local patrons visit tea shops and sit around small square tables on footstools sipping tea and chatting about the latest English Premiere League Results. The conversation is not limited to business talks, information exchange, and news access for local and national politics. It has been known that a cup of tea is a call to socialize with one another (Myint 2020).

Tea shops are informal gathering places (Thein-Lemelson 2021) where people with different backgrounds regarding ethnicity and religious beliefs meet frequently and conduct dialogue activities (Lu 2000). Myanmar tea shops have historically been venues for dialogue, debate, and reconciliation (Myint 2020). Several studies included tea shops’ distribution across the country.

For example, Keeler (2017) describes tea shops as Burmese’s ubiquitous institutions that can be found everywhere in the country. Similarly, Myint and Aung (2021) introduce the idea that Myanmar tea shops have become a universal social space and institution throughout the country. Hilton, Maung, and Masson (2016) state that Myanmar’s abundant tea shops sprawl across urban and rural settings. Milko (2017) presents that tea shops have been a long-standing part of Myanmar’s cultural history, from the crowded sidewalks of Yangon to the small villages of the country’s northernmost Kachin State.

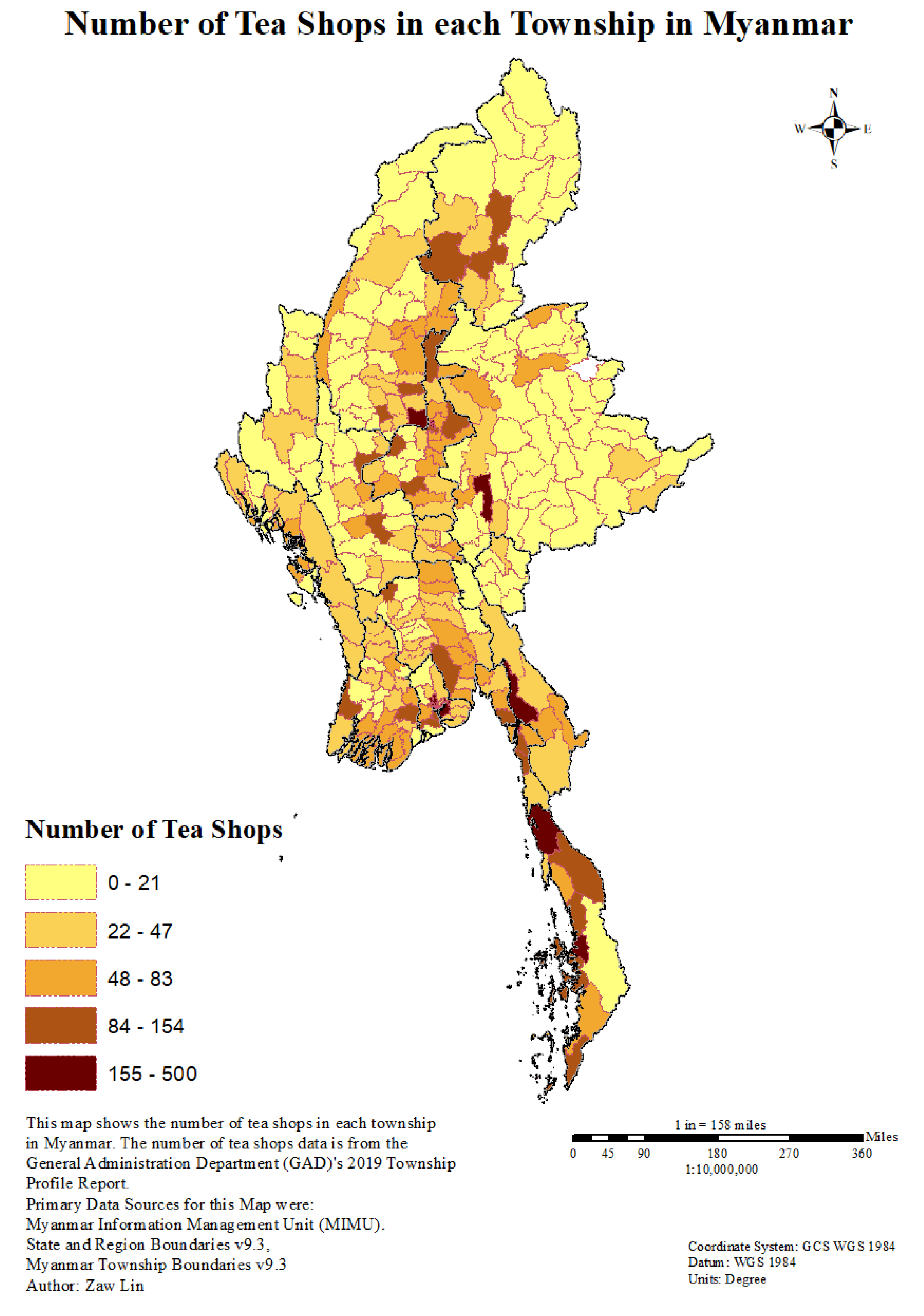

Figure 1 illustrates the number of tea shops in each township in Myanmar.

Despite its widespread distribution, little is understood about these microstructures’ full array of functions in community life. For example, much of the literature on micro institutions in Myanmar has focused on microfinance as an organized mechanism that provides financial services as an instrument in favor of people experiencing poverty, mainly in the rural community (Wun, Nusari, and Ameen 2019). Likewise, a search on Google Scholar using the keywords “micro institutions,” “Burma,” and “Myanmar” appears in the study of microfinance institutions.

1.1. Objective and Limitations

This paper examines the earlier critical studies that describe tea shops’ social, economic, and political role in Myanmar society by analyzing existing literature, journal, news articles, blog posts, and pictures. Before reviewing the functions of tea shops’ social, economic, and political position, the history of tea and the tea-drinking culture are provided. Next, Habermas’s (1997) “public sphere” and Oldenburg’s (1989) “third place” concepts are theorized, and the idea of micro-institution is defined to show the role of tea shops. Finally, the barriers to local women’s participation at tea shops and the progress made in some locales are examined.

The number of tea shops in each township in Myanmar data is collected from the General Administration Department’s (GAD) 2019 Township Profile. Some Micro, Small, and medium enterprises (MSME) were shut down due to the impacts of COVID-19 and the 2021 coup d’état (Inya Economic 2022). Therefore, 2019 might be different from today. Knowing that little information is provided on how GAD collects the data is essential. This is probably the limitation of this paper.

From these examinations and identifications, this paper will provide a discussion on the question of how the scholarship work in the field of Myanmar’s tea shop culture portrays the role of gender participation and child labor within the tea shop ecosystem. In addition, the paper justifies tea shops as an opportunity that enables locales to connect and access information to be informed and take part in community affairs.

With this question, this paper argues that empowering women to have equal opportunities as men to take part in such daily activities—taking part in tea-drinking meetups at tea shops and Myanmar’s traditional tea-drinking meetups, can change Myanmar’s perspective on women’s participation in political dialogue and other significant discussions. Additionally, where it is relevant, personal lived experience and discussion with scholars from Myanmar who have enjoyed sitting in the tea shops will also be provided.

One limitation of this study is the accessibility to data due to the extended turmoil in the country. On February 1, 2021, the military took control of the elected government and instituted a one-year state of emergency (Renshaw and Lidauer 2021; King 2022; Simion 2023), and it has now been extended with the proposed election to be taken in November 2023 despite the rejection from many local political groups. The recurrent coup d’état after years of militarization governing until 2010 and the end of the dream for a transition to democracy occurred with peaceful protests across the country.

However, the peaceful protest turned into nationwide armed conflicts in response to the military’s bloody crackdown, which caused 1046 killed, 7876 arrested, and 6230 detained (AAPP 2023) before the Myanmar Shadow Government, the National Unity Government (NUG) declared ‘National Uprising’ or ‘people’s defensive war’ against Military Junta on 7 September 2021 (Myanmar Now 2021; Regan and Olarn 2021; Strangio 2021). After declaring a ‘people’s defensive war,’ the number of killed, arrested, and detained is growing dramatically. According to Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) presents, there were 3220 killed, 21242 arrested, and 17375 detained as of April 6, 2023.

The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project’s (ACLED) Conflict Watchlist 2023 reports on the splash of the armed conflict over the country. The intensified ongoing friction on a day-to-day basis, the frequent internet shutdown, and the security concerns arising have become the major limitation of this paper to reach the target participants, who are the tea shop owners, the young rural migrants who work at tea shops, patrons who often visit tea shops, and other key informants. Therefore, this paper relies on existing literature, journal, news articles, blog posts, and photos of tea shops and uses sociological perspectives to discuss the role of tea shops in Myanmar society. analyzing

1.2. Myanmar

Myanmar society is a highly diverse and divided nation (Kim, Alemi, Stempel, Siddiq 2022; Zan and Luaterjung 2022) with a population of 55 million (UNFPA; World Bank 2021; ILO 2022; IMF n.d.; ADB Bank 2021). The country’s diversity constitutes 135 ethnic groups with distinct histories, cultures, traditions, religions, and languages. Burma or Bamar is the majority ethnic group, and Buddhism is the state religion. Kramer (2010) notes that the data for Burma should be treated with great caution as there are no reliable population figures. Most of the population and ethnic people live in rural areas. According to the Census Atlas Myanmar 2014, more than 70 percent of the population lives in rural areas 2014.

A rural-dominated Myanmar heavily relies on agriculture, the country’s main economic activity. It shares 30 percent of the country’s GDP, 25 percent in exports, and 56 percent of the labor force (FAO and WFP 2021). The country occupies 676,600 square kilometers of land and 1,930 kilometers of coastline on the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. It shares a great land border with five neighboring countries: Bangladesh to the west; India to the northwest; China to the north and northeast; Lao PDR to the east; and Thailand to the east and southeast (Census Atlas Myanmar 2014). Than (2005) provided the distance of shared kilometers in

Table 1. The country is slightly larger than the country of Afghanistan and somewhat smaller than the U.S. state of Texas. However, after Indonesia, it is the second largest country in Southeast Asia.

Despite these significant shares in agriculture activities, geographical advantages, and abundant natural and human recourses, poverty is still widespread (Maizland 2022) due to political stasis and over 70 years of armed conflicts contributing to underachievement in social and economic development (Smith 2005; Kramer 2010). Than (2005) states that ethnic conflicts are associated with the national identity in a multi-ethnic and multi-religious society. Rural livelihoods are severely poor due to the low productivity of agriculture, lack of access to essential services, and inefficient public resources spending (Haggblade, Boughton, Cho, Denning, Kloeppinger-Todd, Oo, Sandar, Than, Wai, Wilson, Win, and Wong 2014; Myint, Badiani-Magnusson, Woodhouse, Zorya, Ramadan, Belete, and Jaffee 2016; Paudel 2022).

As a result, the country has been named as one of the least developing countries by the United Nations. The UNDP Human Development Reports 2022 also classified Myanmar’s Human Development Index (HDI) in the "medium human development category" with—145 out of 191 countries and territories. In addition, Kim et al. (2022) described the country as one of the poorest nations in Southeast Asia.

2. The History of Tea

In the developing country Myanmar, under its educational reform, there are limited resources and capacities for empirical research development. Therefore, the theoretical and conceptual studies on this particular interest, the tea history, and the tea-drinking and -eating are automatically limited. However, two accessible analyses of the history of tea by local scholars, such as Htay, Kawai M, MacNaughton L.E, Katsuda M, Juneja L.R (2000), and Myint and Aung (2021) describe the piece history of tea.

For instance, Htay et al. (2006) describes a Burmese legend poet “U Ponnya” (AD 1812-1897), saying that tea seeds were given to Phyu King Duttabaung (BC 443-372) as gifts. The seeds were received with one hand instead of two to show respect to the king. For this reason, tea in Myanmar was named “Lat-ta-phet,” which means “one hand” in the local Burmese language. However, this piece of legend story is unclear.

Similarly, Myint and Aung (2021) describe the beginning of tea in Myanmar can be found in an oral story that dates to the 5th or 6th century. This piece of oral story-history noted that Burman King Alaungsithu gave tea seeds to the Ta’ang people who lived poorly and struggled on the high mountain. The Ta’ang farmer received the tea seeds with one hand, “Lat-ta-phet,” from the King. Therefore, the name of the leave was given as “Lat-ta-phet,” and later, it gradually changed into “lat-phet.”

Contrasting these interpretations, Myint and Aung (2021) added that the

Ta’ang people, also known as “

Palaung” by other non-

Ta’ang communities, mostly live in the upland areas. They were known as the first tea cultivators in Myanmar. For generations, tea cultivation has been their livelihood, and tea products have been their primary source of income.

Ta’ang people are credited as the first tea cultivators in the country. A common saying translates, “If you want to eat good quality tea, slowly climb up the

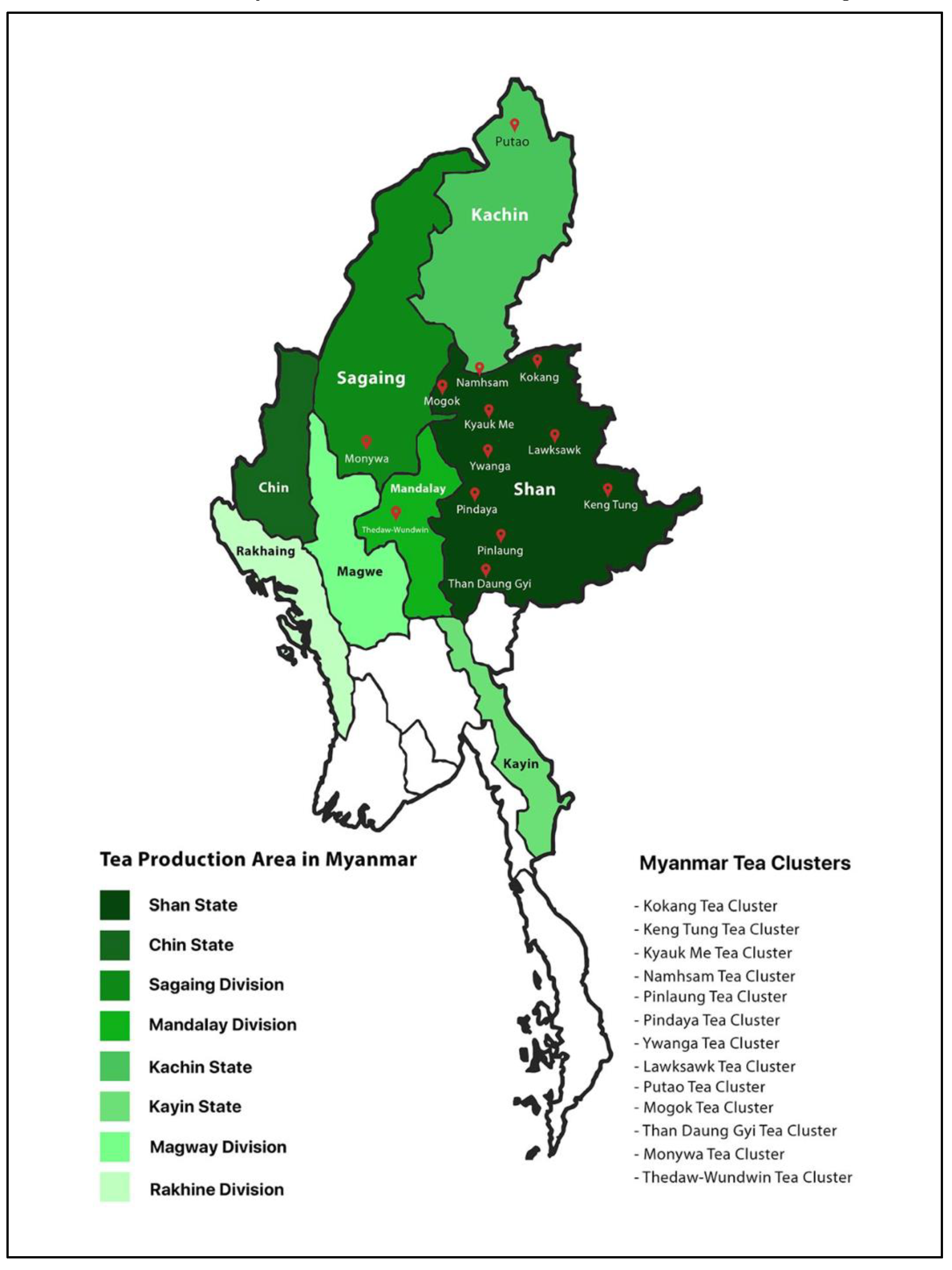

Palaung’s hill.” Today, other Indigenous people also grow tea. Tea cultivation is widespread across the country where the climate is suitable, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

It is vague whether the tea-drinking or the tea-eating culture began first. Regardless of the limitation of empirical research, the tea-drinking habits and tea-eating culture can be assumed to have followed one another. In this section, the tea-drinking culture is first reviewed, and then fermented tea (Laphet-So) or pickled tea leaf (Laphet-Nut) culture.

2.1. Tea-Drinking Culture

Like the portion of tea history and the following tea-eating culture, this section cites Myint’s recent work with Ms. Sandar Aung and old work on the analysis of tea culture to explain the tea-drinking culture. These two available studies explicitly illustrate the unit of unique tea-drinking setups in Myanmar.

For example, Myint and Aung (2021) state that the tea-drinking traditions (Ah-Khar-Ye) can be traced back to the last 900 years, the Konbaung Era. During that time, “Laphet-Ye-Daw-Kine,” the King’s tea server, had a prestigious and influential role in serving tea to the King. Since then, green tea drinking has become a celebration of royal ceremonies at the palace. The decorated teacups, teapots, and bowls became exchanged gifts among the royal families and between the Kingdom. For example, Bwar (2014), King Shwe Htee (1530-1550) exalted the warlord King Bayaintnaung Kyaw Htin Naw Yatha (1550-181) after marching on Yodaya (Thailand). King Mindon also gifted a teapot to his younger brother, which was decorated with twelve mosaic mirrors and three rows of rubies.

Following this footprint, Myint (2020) states that the tea-drinking tradition, which transformed from an exclusive practice reserved for the upper class and monarchs, is now widespread nationwide. In this way, the tea-drinking tradition has become an everyday habit of Myanmar people. It also recognizes as a vital establishment in Myanmar’s daily cultural scene. Whether in the city or rural areas, the local families serve green tea drinks (Ah-Khar-Ye) or pickled tea leaf salad (Laphet-Thoke) when welcoming guests or visitors. Therefore, every household in the village, city, and monastery has teapots and teacups. Regardless of ethnicity and religion, the tea is drunk by almost everyone, from young to old.

In addition to the significant influence of tea-drinking habits across the country, Myint (2020) continue to elaborate on the role of traditional tea drinking-in social interaction. The elaboration describes the tea-drinking meetup as a sphere where the tough conversation about community issues, business, and children’s affairs, and casual chitchat happen. It is also a place where close friends are open to one another. Regarding this social interaction in tea-drinking meetups, Myint’s (2020) analysis of tea culture includes critical interaction, and it is described as

In Myanmar society, it is a place where people meet and establish mutual respect with each other while discussing personal matters such as children and business. As they are mostly close friends, tea meetups are a way of securely opening up on personal feelings as they mutually trust each other…. Myanmar laphet-ye-jan-wine helps create friendships among people and encourages knowledge sharing…. Tea drinking is one of the favorite pastimes of Myanmar people, regardless of location, occupation, and social status. It is a way in which people relax and establish collaboration, familiarity, and unity (Myint 2020:218).

However, Myint’s (2020) analysis of tea culture does not include the theoretical and conceptual framework on how the traditional tea-drinking meetup setting is constructed as a sphere where mutual respect, friendship, collaboration, familiarity, and unity are established. Regardless of this theoretical and conceptual absence, tea-drinking meetups still play an essential role in the daily life of Myanmar people, as exemplified in the findings and discussion.

2.2. Tea-Eating Culture

While there is not much literature that sufficiently describes the beginning of the tea-eating practice, two qualitative accessible studies by Han and Aye (2015) and Myint (2020) elucidate that Myanmar is a country that habitually eats and drinks tea for a long time. The tea becomes edible after the fermented process. The locals pickle the fermented tea to consume it. The edible pickled tea leaf salad is called Laphet-Thoke. In the study of the emergence and influence of fermented tea (Laphet-So) or pickled tea leaf (Laphet-Nut) culture and how everyone in the country has habitually eaten it, Han and Aye (2015) describe that,

Myanmar fermented tea leaves are a typical signature and ancient national food eaten by everyone in the country, regardless of race or religion, at a get-together in family homes, monasteries, and traditional celebrations (Han and Aye 2015:173).

In addition to the description, Han and Aye (2015) that the tradition of tea-eating habits makes fermented tea (Laphet-So) or pickled tea leaf (Laphet-Nut) available everywhere in the country. Ones can eventually buy at Myanmar’s stores or markets outside the country. Traditionally, the locals eat and drink hot green tea to catch up on their gossip. Furthermore, students and professional workers consume pickled tea leaf salad (Laphet-Thoke) when they have exams and deadlines to catch up.

As a result, fermented tea (Laphet-So) or pickled tea (Laphet-Nut) became an essential piece of Myanmar’s society. The product was once served after a meal at a local house, and traditional ceremonies, such as weddings, funerals, engagements, and other religious events, have now been portrayed as a national food and drink. For instance, the pickled tea leaf salad (Laphet-Thoke) and tea drink (Ah-Khar-Ye) are often served during local, state, and national official meetings. Therefore, Myint (2020) affirms that fermented tea (Laphet-So) or pickled tea (Laphet-Nut) has become an ancient national food.

3. Tea Shops

The studies on the origin of tea shop culture remain unclear. While Lu (2000) said that tea shops culture is not derived from foreign because there is a practice somewhat like sitting at a tea shop in Myanmar’s rural livelihood; for example, in rural areas, adults and older people sit on the oversized bamboo mat in front of houses and drink tea when the moon shines at night. In their conversation, they share community issues and talk about Vedanyatra, “astrology,” secular knowledge, and planetary systems while drinking green tea and tasting baked fish, fried peanuts, and palm sugar.

However, a recent qualitative study by Myint and Aung (2021) and including Myint’s earlier analysis of tea culture, also consists of the beginning of blacking tea-drinking culture in Myanmar. Unlike Lu (2000) shared, the culture of black tea drinking seems to be introduced in the early British colonial forays. For instance, Shar’s study (2011) presented the emergence of tea shop culture in lower Myanmar following the annexation of the then-called “Lower Burma.” The tea shops owned by Indian migrants introduced sweetened milk tea to the public, serving as a gateway for Indian influence in Myanmar’s food culture.

Before Shar’s study, Myint and Aung (2021) noted that the English Commissioner of India Division sent Arthur Pharyre as head of a delegation to the Myanmar palace during King Mindon’s regime (1853-1878); they presented a silver teapot and other silverware for drinking English tea (black tea). This historical exchange assumes to be the case at the beginning of the black tea-drinking culture in Myanmar.

Regarding this, Myint and Aung (2021) expressed that in these urban tea shops, the rural plain tea-drinking (tea drink with no blending with milk and sugar) culture, which referred to the green tea-drinking habit that had already increased throughout the state met its perfect match. In time, these two cultures merged, and black tea-drinking culture with milk and sugar has been widespread. It is served mainly in local tea shops.

Because of the relationship between the two cultures in the tea-drinking setups, it is typical for tea shops, whether rural or urban, to serve their patrons free-flow of plain tea drinks (tea without adding milk) sugar). For this, Myint (2020) describes that,

Traditionally, tea shops offer free plain tea refills whenever a table runs out of plain tea. It is a social norm in Myanmar society. Plain meetups are good because they do not present any health hazards or are costly (Myint 2020:218).

Therefore, the development and sustain of the tea-drinking meetups in tea shop culture is the combination of Myanmar’s traditional green tea drinking (Ah-Khar-Ye) culture and English’s black tea, as noted by Myint and Aung (2021) and presented by Shar (2011). These tea-drinking habits highlight the daily life of local people. One can explore the local’s everyday social and economic activities through tea-drinking practices—everyday resistance.

In this part, the paper mainly reviewed Myint’s (2020) analysis of tea culture in Myanmar society, Han and Aye’s (2015) analysis of fermented tea leaf, Myint and Aung’ (2021) tea culture and gender, and other subsidiary studies such as Htay et al. (2000), Lu (2000), and Bwar (2014). It explained the tea history, tea-drinking and -eating culture, and the development of tea shop culture locally.

Habermas’s (1997) “public sphere” and Oldenburg’s (1989) “third place” are the ideal concepts to elaborate the nature of Myanmar’s people’s daily tea-drinking meetups at tea shops. And then the idea of micro-institution and its importance.

3.1. Tea Shops in the Public Sphere

McKee (2005) defined the “public sphere” as where each of us finds out what’s happening in our community and what social, cultural, and political issues are facing us. The “public sphere” is where the public engages with issues and adds their voices to discussions. The public may participate in reaching a consensus or compromise about what they think about issues and what should be done. Habermas (1997) introduced the public sphere as where the citizens of a country exchange ideas and discuss issues to reach an agreement about “matters of general interest.” Dahlgren (1995) and Fraser (1995) stated that the “public sphere” is where information, ideas, and debate can circulate in society and where political opinion can be formed.

3.2. Third Place

In response to the absence of an informal life in today’s modern society, Oldenburg (1989) introduced the “third place” concept that forms neutral ground, i.e., where individuals may come and go as they please, in which none are needed to play host, and in which all feel at home and comfortable. The third must be a leveler, an inclusive place. It is accessible to the general public and does not set formal criteria for membership and exclusion. Individuals can select their associates, friends, and intimates from among the participants. The conversation is the main activity in the third place.

The places must be accessible, i.e., the timing and location, and accommodate the visitor’s need for sociability and relaxation. There must be regulars, the customers who come to the place regularly. These places are not necessarily look impressive for the most part. They are in low profile. The conversation and vibe of third place are playful and laughing. The conversation may be low-key or pronounced, but the playful spirit is essential to reign over anxiety and alienation. The third place must provide the feeling of home, where warmth emerges from friendliness, support, mutual concern, and a combination of cheerfulness and companionship. The traits of the third place seem to be fundamental and applicable across different cultures and are necessary for a thriving and informal public life (Oldenburg 1989).

3.3. Understanding Micro-Institutions

Joshi (2014, 21) cites Sherry Arnstein’s (1969) pivotal ‘ladder of participation.’ This framework addresses who has the power and how much power village organizations have. The typology has eight ‘rungs’ based on degrees or levels of participation, from manipulation at the bottom to citizen control at the top. Not presented as a hierarchy, it is a continuum of levels of power from non-participation (manipulation and therapy) through degrees of tokenism (in ascending order informing, consultation, and placation) to rungs of citizen power (partnership, delegated power, and citizen control) (Arnstein 1969). Arnstein’s theory shifts the argument away from power as a zero or positive-sum model. Instead, it emphasizes the potential for agency within village organizations rather than confining it as a project structure.

Tea shops are at regular times’ bottom rungs of the participation ladder. Nonetheless, as discussed below, tea shops take on essential social, economic, and political functions in times of conflict and instability.

4. Discussion

This section discusses the tea shop’s social, economic, and political role to describe the opportunities and limitations to women’s participation in Myanmar’s tea shop settings and rural migrants, including the child laborers migrating from rural, in the teashop.

4.1. Socializing in Tea Shops

Several scholars, such as Lu (2000), Milko (2017), Win (2017), Myint (2020), and Carr-Ellison (2021), describe and include the role of the teashop as a space for socializing. For example, Lu (2000) explains that tea shops are accessible to everyone. There is no social class discrimination at tea shops. All kinds of people, such as the jobless, wage workers, street vendors, tricycle drivers, taxi drivers, artists, employees, officials, lawyers, doctors, local teachers, businesspeople, and brokers, are found in tea shops. Those who drink specially blended tea share the same table and seat as those who drink regular tea.

Regarding the role of a tea shop in socializing, Milko (2017) shared a respondent’s opinion, and it is described,

"Tea shops are not just where people go to get good, cheap food," says artist Kaung Kyaw Khine, 35, who earlier this year was featured in an art show in Yangon focusing on tea shops. "It’s a part of our culture, history, and where people go for all matters in life."

In addition, Win (2017) asserts tea shops as social contact places. They are significant places in Myanmar’s society. For example, teenagers used tea shops to listen to popular music or watch sports/movies. Adult men used tea shops to meet and talk with their colleagues. In addition to, Win’s (2017) study of the geographical distribution of tea shops in the urban area found that people who live nearby tea shops have a more comprehensive social network by visiting tea shops and chatting with neighbors regularly.

Like Milko’s respondent’s opinion, Myint’s (2020) analysis of tea culture included another respondent’s perception of the tea shop. It is described as,

“Tea shop is not just a place which only intends to get good taste and cheap foods.” But, he continued, “We are spending time at the tea shop not because we don’t have anything to do. For us, a cup of tea is an opportunity to sit down and discuss: to share knowledge amongst old friends and new” (Myint 2020:217).

Finally, Carr-Ellison (2021) also describes that tea shops are the bedrock of social life in Myanmar. The local people spend hours in tea shops gossiping with friends, chatting, laughing, reading newspapers, and playing on their phones. In addition, artists spent time in teashops to create a masterpiece. Therefore, based on Lu’s (2000), Milko’s (2017), Win’s (2017), Myint’s (2020), and Carr-Ellison’s (2021) discussion, tea shops are a social space for the local community to communicate and interact daily.

4.2. Business Meetings in Tea Shops

The local people use tea shops to conduct everyday business activities. For example, Win (2017) describes tea shops as business offices, such as appointment centers and entertainment venues. Likewise, local auto and real estate brokers use tea shops for social networking and information exchange to conduct business activities. Similarly, Keeler (2017) describes local people coming to tea shops when a vital soccer match is broadcast live on satellite TV. Indeed, during the English Premier League sports season, the tea shop owner tries to broadcast soccer matches to attract patrons.

In contrast to the business meeting in tea shops, Carr-Ellison (2021) included those political activists who assembled in them at the tea shop and debated and pontificated about issues in the community. Regarding the political conversation in tea shops, both Nya (2016) and Carr-Ellison (2021) mentioned the former US. Ambassador said that “all-important words” start in tea shops in Myanmar.

4.3. Tea Shops in the Historical Political Movement

Smith (2002) describes the country’s independence in January 1948 as followed by armed conflict started by the Communist Party of Burma (CBP) in March 1948 and the KNU in January 1949. It rapidly escalated among other ethnic groups, including the Kareni, Mon, Pao, Rakhine, and Muslims of north Arakan (Shakoor 1991; Smith 2005). The armed conflict has continued through today, from the parliamentary democracy (1948-1962), military socialist (1962-1988), and transitional military rule (1988-2010) to the current democratic transition (2010-present). Peace and conflict resolution have long been underachievement. The resources are wasted. The armed conflicts are unresolved.

4.4. Social Cohesion and the Peace Process

Many peace and conflict resolution projects, such as training and workshops, were conducted in response to armed conflicts in 2014. However, the training and workshop time needed to build the necessary trust to allow for deeper sharing and, therefore, deeper learning among diverse groups of people was inadequate. The training and workshops would lead to greater understanding resulting from increased contact and, so, a higher likelihood of relational transformation (Zan and Lauterjung 2022). In addition, the lack of understanding and appreciation for diversity is limited. Many other groups are marginalized, such as people with disabilities and LGBTQ.

Zan and Luterjune (2022) state a challenge in promoting dialogue in Myanmar is finding ways to honor these cultural norms while offering an opportunity for people to learn about each other. The authors cited a well-established author Min Lu (2000), who mentioned that there is a traditional dialogue in Myanmar called laphet-ye-wine (“tea circle”) is commonly understood, regardless of religion or ethnicity, to refer to tea shops as places to gather and discuss the issues of the day.

4.5. The Origins of Myanmar’s Democracy Movement

The 1962 coup d’état led by General Ne Win isolated the country from the rest of the world. The isolation led the nation to poor socio-economic development and increased poverty. During the military regime, one common way local individuals found to one another was the regular gathering at tea shops. Steinberg (2013) describes tea shops as where open discussions happen. The frequent visits form a “bridging” tie between the local individuals. A music video released before 1988 by a famous local singer Khaing Zar encouraged local individuals to visit tea shops to connect to the world and exchange knowledge until a small incident changed the political culture in Myanmar.

Several scholars, such as Seekins (2017), Aung-Thwin (1989), Steinberg (2010), and Mullen (2016), describe a story of a fight that broke out at a tea shop between students nearby Rangoon (now known as Yangon) Institute of Technology and local youths over the choice of music to be played on the shop’s cassette player. When one of the youths was injured, a student was arrested and then released because he was a son of a member of the local People’s Council; the students then took part in a protest march for justice. However, the riot police (known as Lon Htein) murdered several students. The protest rapidly escalated, increasing tension between the riot police, Tatmadaw troops, and students. Many students were killed. The demonstration was later known as the “1988 Student Uprising”, often referred to as the origin of the democracy movement by students in the modern history of Myanmar.

When having information first in hand was important during the 1988 uprising (Seekins 2017), military government informants (Military Intelligence, MI) were known to spend time in tea shops to crack down on student protests (Zan and Luaterjung 2022). The mistrust flourished. However, the slowly shifting to democracy in 2010 reboots the tea shops as hubs for lively conversation. These circumstances highlighted the tea shops as a symbol or an icon of where the democratic movement was started.

While the potential role of a tea shop in social, economic, and political activities needs further investigation and verification, the existing studies conducted by different scholars have assured the essential feature of tea shops in the daily of Myanmar people. Furthermore, this paper argues that empowering women to have equal opportunities as men to take part in such daily activities—taking part in tea-drinking meetups at tea shops and Myanmar’s traditional tea-drinking meetups, can change Myanmar’s perspective on women’s participation in political dialogue and other significant discussions. Therefore, women’s participation in tea shops must be explored and defined.

4.6. Teashop as Community Resistance

Thein-Lemelson (2021) describes tea shops as where the local community regularly gathers with one another. These establishments have the stable and characteristic features of informal gatherings. Mullen (2016), for example, describes tea shops as the local people’s everyday spaces and the community’s resistance techniques. The modern history of Myanmar is marked by repressive rule, clear human rights violations, and prolonged armed conflicts (civil war). The media censorship, the military’s oppression of freedom of speech, and access to information have shaped the tea shops’ role in connecting and unifying local people to resist political repression.

For example, Oak and Brooten (2019) included that tea shops were where local people sat every morning for 8 o’clock news and information before the military government opened to the world in 2010 and allowed social media to spread. Similarly, Asher (2021) reported that during the year of censorship, local people had to visit tea shops to be informed and stay current.

Recently, after the military junta took control of the country from the free and fair elected government

2, the military often shut down and restricted internet and mobile network access and cut off the electricity to control access to information and to disregard the violence by the military junta’s police, as reported by many international news agencies. For example, Januta and Funakoshi (2021), Ratcliffe (2021), and Nachemson (2021) say that the military junta imposed increased restrictions on internet access to suppress protests. In addition, news agencies based locally, such as Radio Free Asia (RFA)

3, Voice of American (VOA)

4, and Myanmar Now

5, also reported the frequent electricity cut in Myanmar. Under these circumstances, rural people, and those in towns, especially those without television or electricity, visit tea shops for news and information.

5. Gender Participation in Teashops

Followed by the traditional tea-drinking meetups, there is a vast disparity in gender participation in tea-drinking meetups in tea shops and elsewhere in Myanmar culture. For example,

Figure 3 vividly shows the exclusion of women in traditional tea-drinking meetups in rural settings. However, it is still unclear what the limitations are and how Myanmar’s society disregards women from being included in the tea-drinking meetup conversation.

A first discussion with a Kachin ethnic scholar

6 who has experience seeing tea shop culture in Myanmar commented that the “traditional labor division” is one barrier that blocks women from participating in tea shops. During teashop’s busy hours in the morning, women in Myanmar remain to do the household work and prepare food for the family. Men usually have no obligations to do the household work. It is culturally accepted. Therefore, men find out to meet friends at tea shops and build social capital.

A second discussion with a Shan ethnic scholar

7 provides a different perspective on women’s participation in tea shop culture and is worth considering the labor division within the shop. From the consumer’s side, the participation of women may be hardly visible. However, he mentioned the role of women in the tea shop’s labor force. Young girls usually work as waiters to provide services to patrons—some function as junior chefs to cook and prepare subsidiary food at the back of the tea shop. Some work as cashiers at the counter.

While these two contrasting discussions have this paper to consider for further research, Myint’s recent work with scholar Aung also elucidates the cultural dynamics of gender participation at tea shops and describes that-

Where the laphet yay gyan wine is considered a gender-neutral custom, the tea shop has historically tended to be regarded as a male-dominated space. No law has ever been written prohibiting women from tea shops, but they have been seen as less-frequented spaces for women and, instead, as a place for men to meet outside of the home away from their families. However, this culture appears to be changing, with many women now accompanying their male partners and friends and even sitting alone or in groups in tea shops. Yet even though everyone drinks tea in Myanmar society, whether young or old, male or female, tea shops are still generally set up to cater to a predominantly male clientele (Myint and Aung 2021:10).

In addition, Gora (2015) reported that men’s domination is the only downside of tea houses in Myanmar. Gora’s conversation with the co-owner of Rangoon Tea House mentioned that many women might be intimidated because there are a lot of men, and they don’t want to go in and be stared at. As a result, fewer women visit teashop unless with friends or partners.

Regardless of the change and growth of women’s participation in the tea shop, Milko (2017) also expresses both men and women own tea shops in Myanmar. However, the patrons are traditionally male-dominated. In the exact portrayal, Frank and Falzone (2021) said that tea shops are where a diverse range of characters come and mingle, interact, and chat. They have a reputation for welcoming people from all backgrounds and walks of life, yet the role of women is hardly visible. Regarding this, Hilton, Maung, and Masson (2016) response that,

For years, these have been no-go zones for women, where men congregate to ponder on news events and politics and access information, including on climate change. While tea shops have increasingly accepted female patrons in urban settings, these spots remain exclusively for men in rural areas. Women in these areas have few avenues to access information on the weather and rely primarily on radio programming (Hilton, Maung, Masson 2016:9).

When women do not have much like men’s opportunities to take part in such everyday life, they often struggle to secure participation in decision-making positions (Latt, Ninh, Myint, and Lee 2017). As a result, they are often excluded from public life (Alliance for Gender Inclusion in the Peace Process, n.d.). In contrast, men establish their social capital, essential for resilience across social levels, including communities, yet insights are scattered across disciplines (Carmen, Fazey, Ross, Bedinger, Smith, Prager, McClymont, and Morrison 2022).

Concerning the male’s spending time in tea shops, Keeler (2017) shares his experience of increasing tea shops in 1987 and 1988 by 2011. He elucidates that more, or at least more males, had nothing better to do with their time than sitting in tea shops, whiling away the hours in conversation, smoking, or watching TV. For this, Myint (2020) also describes that,

It is usual for Myanmar men to go to tea shops, gather around small square tables, sitting on footstools. Myanmar men can sit for long periods in this position, sipping tea and chatting about many topics. Tea drinking in Myanmar is one of the main ways people (especially men) socialize (Myint 2020:216).

According to the different scholars’ discussions, the role of women’s participation in tea shops is not fully encouraged due to the cultural norms and social structure, such as the “traditional labor division,” and neither supported by the opposite gender. Although a recent study by Myint and Aung (2021) includes a change in women’s participation, the number is still significantly low.

6. Child Labor and Rural Migrants in Myanmar

Constant et al. (2020), Win and Siriwato (2020), and Augustus (2022) described child labor at tea shops. For example, Win and Siriwato (2020) say that poverty and economic hardship are the main reasons for too many child laborers in most developing countries. However, child labor in Myanmar is unlike elsewhere; it is socially accepted and conducted widely and openly (Kennedy 2018; Win and Naing 2023.).

Domestic demand, familial poverty, cost of education, the social value placed on education, disregard of international policies, insufficient regulatory policies, insufficient enforcement of national policies, and culture: of filial piety are the factors that persist the child labor in Myanmar (Augustus 2022). In addition, the financial need, displacement, and school drop due to the impacts of COVID-19 and the 2021 coup d’état are also factors that contribute to increasing child labor in Myanmar (Aswan n.d.).

Lwin (2021) describes that according to the 2015 Labor Force Survey Report by the Ministry of Labor, Immigration and Population (MOLIP), 1.13 million children aged 5 to 17 engage in the workforce, 58.3% in the agriculture division, 17.5% in the industrial division, and 24.2% in the services occupation, mining, construction, and tourism (Augustus 2022). Furthermore, Augustus (2022) states that there are gender discrepancies in the type of work, with boys primarily working in tea shops while they are young and construction sites while they age.

These child laborers are from rural areas. They leave school to help the family’s income. Hong (2021) outlines how poverty and structural inequalities are the factors that force them to drop from going to school. Working at tea shops does not require complex labor skills; they have practical training to serve and communicate with patrons. The owners or managers teach them basic calculation skills. Therefore, young women carry out domestic tasks; boys work in tea shops as waiters and find other casual manual jobs in urban centers of Myanmar. There are legal, semi-legal, and under-aged workers at tea shops.

In addition to the analysis by Hong (2021), he described the persistence of youth migrant workers in Myanmar as the impacts of poverty, the social choice of dropping out of school, and the militant culture of schooling. These persistent poverty and economic hardship have pushed young men and women from rural areas to move to large, overcrowded cities in search of employment. This increases the outmigration across the country when there are not many options to consider for the opportunities and resources to start their own small business. Moreover, this rapid outmigration reinforces the economic crisis in rural communities, potentially to re-increase young men and women leaving their home place for longer.

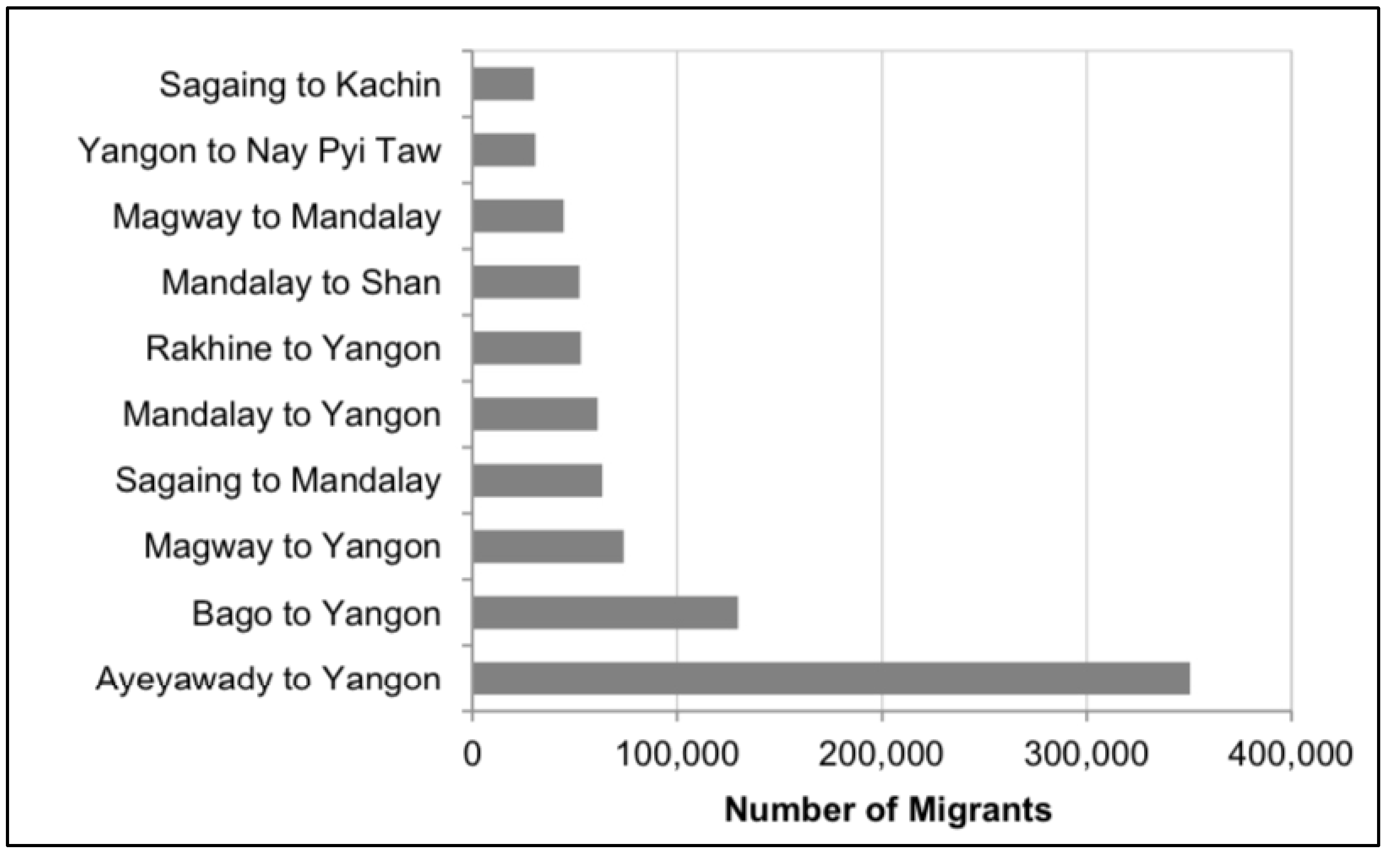

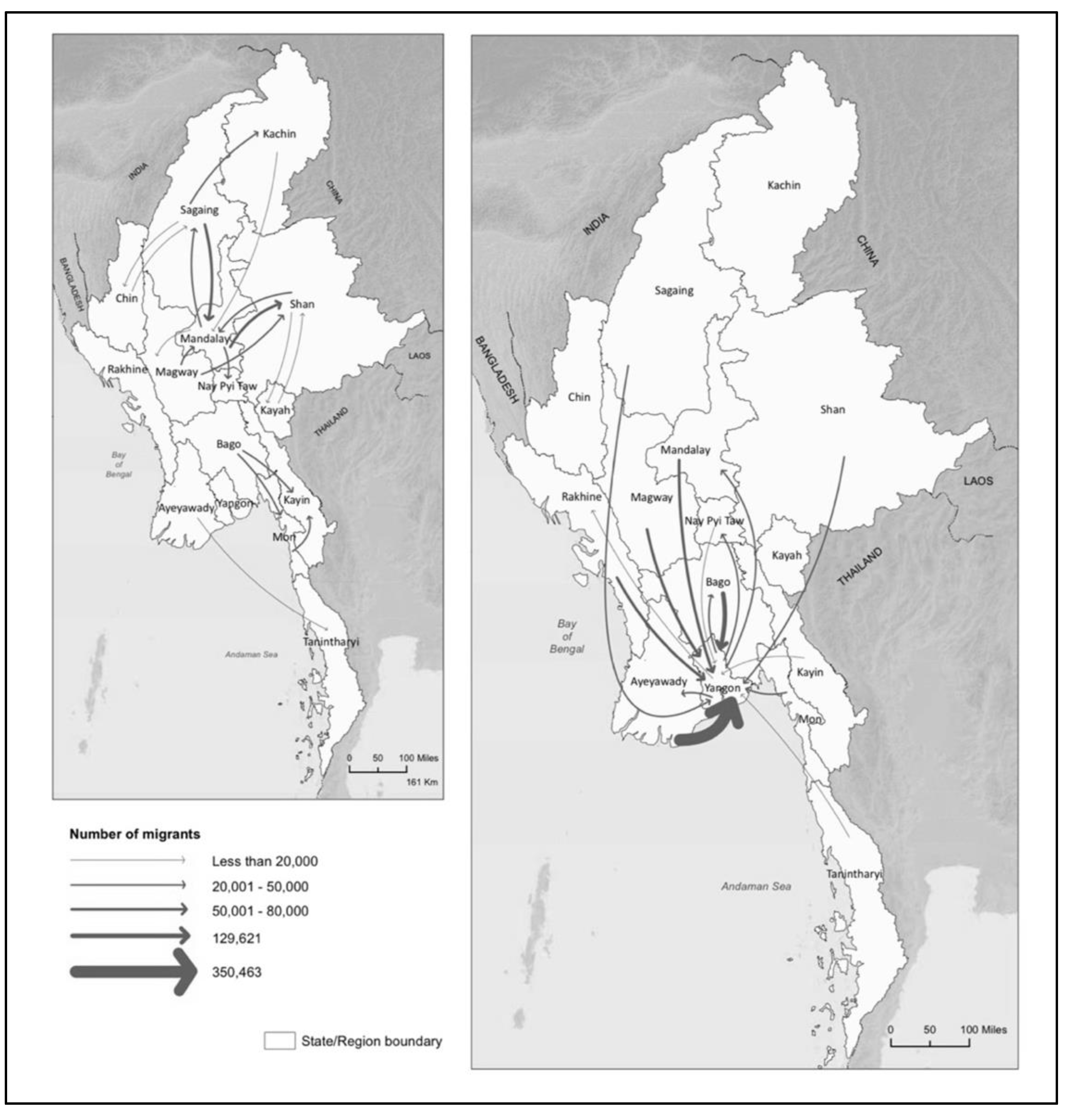

The Census Atlas Myanmar 2014 showed that Yangon, the commercial capital of Myanmar, was the major recipient of internal migrants. Those migrants were from Ayeyarwady, Bago, Magway, Mandalay, and Rakhine.

Figure 4 shows the number of recent internal migrants reported in 2014.

Figure 5 shows the recent internal migrant flows between the States/Regions other than Yangon Region and the To and From Yangon Region.

Although there is minimal empirical study on the demographics of those internal migrants, some studies mention young children, saying that these young children work in tea shops. Most are from Ayeyarwady. For example, Adikari and Dunford (2020) describe the teashop workforce as transient, and many workers come from villages or smaller towns (especially from Ayeyarwady Region).

In addition, Mahato, Paudel, and Baral (2022) expand on the factors driving rural youths to migrate. Those are social status, living standard, personal development, household capabilities, lack of awareness, and personal aspiration as social factors; family support, family pressure, and family decision as cultural factors; financial aid, economic security, job unavailability, a low incentive for educated manpower, better opportunity of earning as economic factors; pursue study, high investment, and low returning, quality of education, and invest in education for lifelong learning as educational factors; political instability and feeling conflict as political factors; lack of land to plough, the boredom of farming, natural environment as environmental factors; and finally nepotism, corruption, and harassment as miscellaneous factors.

7. Conclusion

This paper analyzed several existing literature, journal, and news articles, applied personal lived experience and discussion with scholars from Myanmar to discuss the question of how the scholarship work in the field of Myanmar’s tea shops culture portrays the role of gender participation and child labor within the tea shop ecosystem.

Before answering the question, the papers provided a perspective to understanding tea shops’ social, economic, and political roles. This paper has identified tea shops as a social space where local communities conduct their social activities, business meeting centers, community resistance, social cohesion, and the start of the democracy movement in Myanmar. Due to social, economic, and political integration, tea shops’ role remains significant in Myanmar’s society.

Despite changes in women’s participation in tea shops compared to the past, several scholars discussed the stereotypical cultural norms and social structures as persisting limitations for women to enjoy their freedom of involvement in public life. Additionally, “traditional labor division" is a factor to consider when encouraging women’s participation in public life and empowerment in decision-making. The role of tea shops has a less likely impact on rural migrants; however, if zooming the landscape of tea shops, child labor is still widespread. COVID-19 and the recent 2021 coup d’état eventually increased the outmigration and persisted child labor in tea shops and elsewhere.

Further research on tea shops should respond to the “labor division” in the tea shop. More specifically, answering where the people who work in the tea shop come from. In addition, the women’s patriation in earlier Myanmar’s traditional tea-drinking meetups should be identified in future research. Since the paper’s argument, which is empowering women to have equal opportunities as men to participate in such daily activities—participating in tea-drinking meetups at tea shops and Myanmar’s traditional tea-drinking meetups can change Myanmar’s perspective on women’s participation in political dialogue and other significant discussions, further research should specifically emphasize and consider all the aspect of the role of women within tea shop culture due to the limitation of data and resources.

Funding

Research supported by the USAID Lincoln Scholarship Program and the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station, Paul M. Patterson, Director.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 |

Several internal and external profound scholars, such as, Selth (2001), Steinberg (2001), Linter (2003), Keva (2008), Arendshorst (2009), Dittmer (2010), Kramer (2010), Steinberg (2013), Haque (2017), Seekins (2017), Thawnghmung (2017), and Kim et al. (2022) explained the political controversial name change. |

| 2 |

The election was held in November 2020. The National League for Democracy (NLD) won the election. The military claimed there were significant fraud in the election and demanded to re-hold the election. The objection entered the military to seize the state power on February 1, 2021. |

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

Awn Ja Lu, a Kachin ethnic woman from Myanmar, is a graduate student from M.Ed. (Educational Administration and Policy) at the University of Georgia. |

| 7 |

Kyaw MinOo, a Shan ethnic from Myanmar, is a graduate student at Ohio University and doing his Master of Arts in Southeast Asian Studies. |

References

- Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35(4):216-224. [CrossRef]

- Arendshorst, John. 2009. “The Dilemma of Non-Interference: Myanmar, Human Rights, and the ASEAN Charter.” Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights 8(102). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol8/iss1/5/.

- Asher, Saira. 2021. “Myanmar coup: How Facebook became the ‘digital tea shop.’” World, Asia, BBD News, April 12. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-55929654.

- Augustus, Alyssa. 2022. “Child Labor in Myanmar.” Ballard Brief 2022(1):2. https://ballardbrief.byu.edu/issue-briefs/child-labor-in-myanmar.

- ACLED (The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project). n.d. “Conflict Watchlist 2023 Myanmar: Continued Opposition to the Junta Amid Increasing Civilian Targeting by the Military.” Accessed April 3, 2023. https://acleddata.com/conflict-watchlist-2023/myanmar/.

- AAPP (Assistance Association for Political Prisoners). 2023. “What’s happening in Myanmar.” https://coup.aappb.

- Aswan, Assnisa Rezqui Nabilah. n.d. “ILO’s Contribution in Handling the Impacts of COVID-19 on Child Labor in Myanmar.” Jurnal Hukum dan Peradilan 9(2): 171.

- AGIPP (Alliance for Gender Inclusion in the Peace Process. n.d. “Gender Inequality in Myanmar.” Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.agipp.org/en/gender-inequality-myanmar#note1.

- Bwar, Aung Chein. 2014. The Significance of Tea Leaf (Nat Thit Ywet). Myanmar Sar Pay.

- Constant, Sendrine, Pauline Oosterhoff, Khaing Oo, Esther Lay, and Naing Aung. 2020. Social Norms and Supply Chains: A Focus on Child Labour and Waste Recycling in Hlaing Tharyar, Yangon, Myanmar. CLARISSA Emerging Evidence Report 2. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

- Carr-Ellison, Harry. 2021. “Tea Culture in Myanmar.” Conditionally Accepted (blog), Lost Tea. April 12, 2023. https://www.lostteacompany.com/post/tea-culture-in-myanmar.

- Department of Population, Ministry of Labor, Immigration and Population. 2014. Census Atlas Myanmar: The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census.

- Frank, Lauren B., and Paul Falzone. 2021. Entertainment-Education Behind the Scenes: Case Studies for Theory and Practice. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) and WFP (World Food Programme). 2021. Myanmar Agricultural Livelihood and Food Security in The Context of COVID-19 Monitoring Report May 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gora, Sasha. 2015. “Taking the Machismo and MSG Out of Myanmar’s Tea Shops.” Conditionally Accepted (blog), Vice Midea. April 12, 2023. https://www.vice.com/en/article/d759am/taking-the-machismo-and-msg-out-of-myanmars-tea-shops.

- Htay, Hla Hla, Kawai M, MacNaughton L.E, Katsuda M, and Juneja L.R. 2006. “Tea in Myanmar with Special Reference to Pickled Tea.” IJTS 5(3&4).

- Haggblade, Steven, Duncan Boughton, Khin Mar Cho, Glenn Denning, Renate Koeppinger-Todd, Zaw Oo, Tun Min Sandar, Ting Maung Than, Naw Ed Mwee Aye Wai, Shannon Wilson, Ngu Wah Win, and Larry C.Y. Wong. 2014. “Strategic Choice Shaping Agricultural Performance and Food Security in Myanmar.” Journal of International Affairs 67(2):55-71.

- Han, Thazin, and Kyaw Nyein Aye. 2015. “The Legend of Laphet: A Myanmar Fermented Tea Leaf.” Journal of Ethnic Foods 2(2015):173-178.

- Hilton, Melanie, Yee Mon Maung, and Virginie Le Masson. 2016. “Assessing gender in resilience programming: Myanmar.” BRACED Resilience Intel 2.

- Haque, Md. Mahbubul. 2017. “Rohingya Ethnic Muslim Minority and the 1982 Citizenship Law in Burma.” Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 37(4):545-469. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Moon Suk. 2021. “Being and becoming ‘dropouts’: Contextualizing dropout experiences of youth migrant workers in transitional Myanmar.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 34(1):1-18. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Sudip. 2014. “Helping Villages Help Themselves. Localizing development in Myanmar.” M.S. Thesis, International Development and Management, University of Lund. https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=4438708&fileOId=4438716.

- Januta, Andrea, Minami Funakoshi. 2021. “Myanmar’s Internet Suppression.” Reuters, April 11. https://www.reuters.com/graphics/MYANMAR-POLITICS/INTERNET-RESTRICTION/rlgpdbreepo/.

- Kramer, Tom. 2010. “Ethnic Conflict in Burma: The Challenge of Unity in a Divided Country.” Pp. 51-82 in Burma or Myanmar? The Struggle for National Identity, edited by L. Dittmer. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing.

- Kennedy, Ashely Graham. 2012. “Understanding child labor in Myanmar.” Journal of Global Ethics, 15(3):202-212.

- Keeler, Ward. 2017. The Traffic in Hierarchy: Masculinity and Its Others in Buddhist Burma. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Kim, Eunice E., Qais Alemi, Carl Stempel, and Hafifa Siddiq. 2022. “Health disparities among Burmese diaspora: An integrative review.” The Lancet Regional Health-Southeast Asia 2023 8:100083. [CrossRef]

- King, Anna S. 2022. “Myanmar’s Coup d’état and the Struggle for Federal Democracy and Inclusive Government.” Religions 13(7): 594. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Min. 2000. “May I Sit,” September 7 2020Sein Yong Lwin Magazine.

- Laurence, James. 2011. “The Effect of Ethnic Diversity and Community Disadvantage on Social Cohesion: A Multi-Level Analysis of Social Capital and Interethnic Relations in UK Communities.” European Sociological Review 27(1):70-89. [CrossRef]

- Latt, Shwe Shwe Sein, Kim N.B. Ninh, Mi Ki Kyaw Myint, and Susan Lee. 2017. Women’s Political Participation in Myanmar: Experiences of Women Parliamentarians 2011-2016. The Asia Foundation and Phan Tee Eain.

- Lwin, Hnin Phyu Pyar. 2021. “Persistence of Child Labor in Myanmar.” Pp. 216-236 in 3rd International Conference on Burma/Myanmar Studies: Myanmar/ Burma in the Changing Southeast Asian Context Thailand: Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development (RCSD).

- Mckee, Alan. 2005. The Public Sphere: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Myint, Nikolas, Reena Badiani-Magnusson, Andrea Woodhouse, Sergiy Zorya, Bassam Ramadan, Nathan Belete, and Steven Jaffee. 2016. Growing Together: Reducing rural poverty in Myanmar. Yangon: World Bank.

- Mullen, Matthew. 2016. Pathways That Changed Myanmar. London: Zed Books.

- Milko, Victoria. 2017. “The Politics of Myanmar’s Changing Tea Culture.

- Myint, Lei Shwe Sin. 2020. "Analysis of Tea Culture in Myanmar Society: Practices of Tea Consumption in Upper Myanmar." University of Mandalay Research Journal 11:212-224.

- Myint, Lei Shwe Sin, Sandar Aung. 2021. “Traditional and Modernity in Ta’ang Tea Cultivation: Gendered Forms of Knowledge, Ecology, Migration and Practice in Kyushaw Village.” Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development (RCSD) Research Report 26.

- ______. 2021. “Myanmar’s shadow government declares ‘resistance war’ against the military junta.” News, Myanmar Now, April 6. https://myanmar-now.org/en/news/myanmars-shadow-government-declares-resistance-war-against-military-junta/.

- Maizland, Lindsay. 2022. “Myanmar’s Troubled History: Coups, Military Rule and Ethnic Conflict.” Council on Foreign Relations. January 31, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/myanmar-history-coup-military-rule-ethnic-conflict-rohingya?gclid=CjwKCAiAwomeBhBWEiwAM43YIKuc1fuPJSiiMK5e9pLfeKJwowHNzylKUELpZojz5XRvvYXLe4bEWBoC44UQAvD_BwE.

- Mahato, Santosh K., Devi Prasad Paudel, Om Prasad Baral. 2022. “Motivating Factors of Youth Selecting Labor Migration Rather Than Higher Education: A Systematic Review.” Interdisciplinary Research in Education 7(1):115-128. [CrossRef]

- Nya, Maung Nya. 2016. “Mandalay’s Changing Tea Shop Culture.” The Irrawaddy News, April 12. https://www.irrawaddy.com/photo-essay/mandalays-changing-tea-shop-culture.html.

- Nachemson, Andrew. 2021. “Why is Myanmar’s military blocking the internet?” News: Censorship, Aljazeera, April 11. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/4/myanmar-internet-blackouts.

- Oldenburg, Ray. 1989. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community. New York: Marlowe and Compan.

- Oak, Yan Naung, and Lisa Brooten. 2019. “The Tea Shop Meets the 8 O’clock News: Facebook, Convergence and Online Public Spaces.” Pp. 327-365 in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change, edited by L. Brooten, J. M. McElhone, and G. Venkiteswaran. Singapore: Yusof Ishak Institute.

- Paudel, Susan. 2022. “Income Diversification and the Non-Farm Sector in Rural Myanmar: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Survey.” Master of Science Thesis, Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia. ProQuest, 29063177.

- Renshaw, Catherine, and Michael Lidauer. 2021. “The Union Election Commission of Myanmar 2010-2020.” Abstract. Asian Journal of Comparative Law 16(S1): S136-S155. [CrossRef]

- Regan, Helen, and Kocha Olarn. 2021. “Myanmar’s shadow government launches ‘people’s defensive war’ against the military junta.” CNN, April 6. https://www.cnn.com/2021/09/07/asia/myanmar-nug-peoples-war-intl-hnk/index.html.

- Ratcliffe, Rebecca. 2021. “Myanmar coup: Military expands internet shutdown.” The Guardian, April 11. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/02/myanmar-coup-military-expands-internet-shutdown.

- Shakoor, Farzana. 1991. “Burma: An Overview.” Pakistan Horizon 44(2):55-73.

- Smith, Martin. 2002. Myanmar: The Time for Change. Minority Rights Group International.

- Smith, Martin T. 2005. “Ethnic Politics and Regional Development in Myanmar. The Need for New Approaches.” Pp. 56-85 in Myanmar Beyond Politics to Societal Imperatives, edited by K. Y. Hlaing, R. H. Taylor, and T. M.M. Than. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Shar, Ohnmar. 2011. Bamar Traditional Snacks. Yangon: Home Industry Literature Press.

- Steinberg, David I. 2013. Burma/Myanmar: What Everyone Needs to Know. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Seekins, Donald M., eds. 2017. Historical Dictionary of Myanmar. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Strangio, Sebastian. 2021. “Myanmar Shadow Government Declares ‘National Uprising’ Against Military Rule.” Politics: Southeast Asia, The Diplomat, April 6. https://thediplomat.com/2021/09/myanmar-shadow-government-declares-national-uprising-against-military-rule/.

- Simion, Kristina. 2023. Myanmar’s civilian constitution process: challenges, opportunities, and international support for the domestic transition. The Swedish Institute of International Affairs.

- Than, Tin Maung Maung. 2005. “Dreams and Nightmares: State Building and Ethnic Conflict in Myanmar (Burma).” Pp. 65-108 in Ethnic Conflicts in Southeast Asia edited by D. Snitwangse and W.S. Thompson. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Thein-Lemelson, Seinenu M. 2021. “Politicide and the Myanmar coup.” Anthropology Today, 37(2).

- UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund). n.d. “World Population Dashboard Myanmar.” Accessed March 25, 2023. https://www.unfpa.org/data/world-population/MM .

- UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). 2022. “UN list of least developed countries.” https://unctad.org/topic/least-developed-countries/list.

- Win, Kyi. 2017. “A Geographical Analysis on the Distribution Pattern of Tea Shops in Thakayta Township.” Thanlyin Research Journal, Co-operative University 2(1):187-208.

- Wun, Nan Su La Phyi, Mohammed Nusari, and Ali Ameen. 2019. “Effect of Microfinance on Socio-Economic Development of Rural Community in Myanmar.” International Journal of Management and Human Science (IJMHS) 3(3):26-31. https://ejournal.lucp.net/index.php/ijmhs/article/view/807.

- Win, Kya Khaing, and Sasiphattra Siriwato. 2020. “The Role of NGOs in Promoting the Rights to Education of Child Laborers in Mandalay, Myanmar: A Case Study of MyMe Project.” Institute of Diplomacy and International Studies. RSU International Research Conference 2020:1709-1719.

- Win, N. N., and A. Naing. 2023. “Tolerant Tea Shops: The Social Construction of Forbearance in Child Labor.” Journal of Burma Studies, 27(2), 261-289.

- Zan, Kaung, and Joanne Lauterjung. 2022. “Lessons Learned Facilitating Dialogue to Bridge Divides Within and Between Diverse Communities in Myanmar.” Pp. 53-68 in Teaching for Peace and Social Justice in Myanmar: Identity, Agency, and Critical Pedagogy, edited by M. S. Wong. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).