1. Introduction

Echo-planar imaging (EPI) represents a very fast acquisition technique in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). It was first described by Mansfield in 1977 [

1] and has since been refined. In [

2] Poustchi-Amin et al. reviewed the main principles of EPI: to reduce the number of excitation pulses, thus reducing the number of repetition time (TR) periods by acquiring multiple k-space lines per shot, i.e., during a repetition period. It can be performed using only one shot (single-shot EPI), which means that k-space is filled completely following one excitation, or otherwise using multiple shots (multi-shot EPI), i.e., a particular fraction (obeying a regular sampling pattern along the phase-encoding direction) of k-space is filled with data within each TR period. This can be achieved by generating repetitive echo train signals. Apart from diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI), functional MRI (fMRI), and occasionally T2*-weighted (T2*w) imaging [

3], EPI has not been integrated in other routine brain MRI sequences such as fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) for the assessment of inflammatory lesions due to drawbacks in terms of image quality and artifacts.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory disorder of the central nervous system (CNS). Neuro-inflammation thereby results in demyelination and axonal damage with reactive gliosis and lesion formation leading to clinical disability progression [

4]. MS is the most frequent demyelinating disease worldwide, with the highest prevalence levels in Europe and North America (over 100/100,000 inhabitants) [

5]. Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) is the most frequent initial course of MS, and women are affected two to three times (or more) as often as men [

5]. According to the McDonald criteria and its later revisions, dissemination of CNS lesions in time and space needs to be fulfilled for diagnosis, thus inevitably requiring appropriate MRI examinations [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Again, the diagnosis of MS entails further scans for disease activity and treatment monitoring [

10]. For this purpose, a FLAIR sequence is an essential tool for cerebral imaging, and the availability of a fast imaging technique would be relevant in that context, given the high prevalence of this disease and the corresponding costs.

In 1999, Filippi et al. analyzed MS lesion detectability in ultrafast EPI-FLAIR images compared to conventional fast spin-echo FLAIR images. They observed similar lesion numbers for lesions that were greater than ten millimeters in long-axis diameter. Detection of smaller lesions proved inferior using EPI-FLAIR sequences [

11]. Owing to specificity reasons, there has been support for a size threshold of white matter lesions to allow the diagnosis of MS [

12,

13]. According to the McDonald criteria, hyperintense areas are referred to as lesions if they are greater than three millimeters in long axis [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Grahl et al. recently reviewed those stipulations about a lesion size threshold and confirmed three millimeters to be a reasonable threshold to account for diagnostic criteria in MS for three-dimensional (3D) MRI acquisitions at 3 tesla (T) [

14]. However, the effectiveness of EPI-FLAIR sequences has been far from meeting those targets and has therefore not been a suitable option for routine MRI scans.

In recent years, significant advancements in machine learning have gained great attention in the field of medical imaging [

15]. Applied to image reconstruction, these deep learning (DL) techniques provide an improved trade-off between speed, resolution and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and often enable significant reductions in scan times when combined with (highly) accelerated conventional techniques such as parallel imaging (PI) [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Alternative methods include compressed sensing (CS) [

20,

21,

22,

23], simultaneous multislice (SMS) imaging (also known as multiband imaging) [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], iterative denoising (ID) [

29,

30] and synthetic MRI [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

The acceleration provided by these techniques has redoubled interest in further investigations. Particularly, the integration of several of these methods with EPI-based imaging has led to the development of ultrafast multi-contrast protocols, providing all contrasts required in an emergency setting (T1, T2, T2*, T2-FLAIR, DWI) [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. There is also an approach to incorporate various contrasts in one sequence [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. So far, these methods have not been targeting clinical applications that rely to some extent on high resolution data. Also, current research that focuses on EPI-FLAIR in particular is limited and primarily addresses stroke patients and pediatric patients [

53,

54,

55,

56]. In-depth evaluations of MS patient brain images that were acquired using DL-enhanced EPI-FLAIR acquisition techniques have not been conducted to date to our knowledge. Although 3D-FLAIR is clearly given preference over 2D-FLAIR for diagnosis and monitoring of MS [

57,

58], the purpose of this part of our study was to evaluate whether a 2D ultrafast DL-enhanced EPI-FLAIR (FLAIR

UF) sequence of the brain could be an adequate alternative to conventional FLAIR scans.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This prospective, exploratory study was approved by the institutional review board (Project ID 031/2021BO2). We adhered to the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Inclusion criteria were adulthood (≥ 18 years), a routine MRI examination to be carried out on the 3 T MAGNETOM Vida (Siemens Healthineers AG, Forchheim, Germany) scanner, and at least three of the following five MRI contrasts to be conducted: T1-weighted (T1w), T2w, T2*w, DWI, or T2w FLAIR. Moreover, a criterion for allocation to the MS study group was having MS according to the McDonald criteria (2017) [

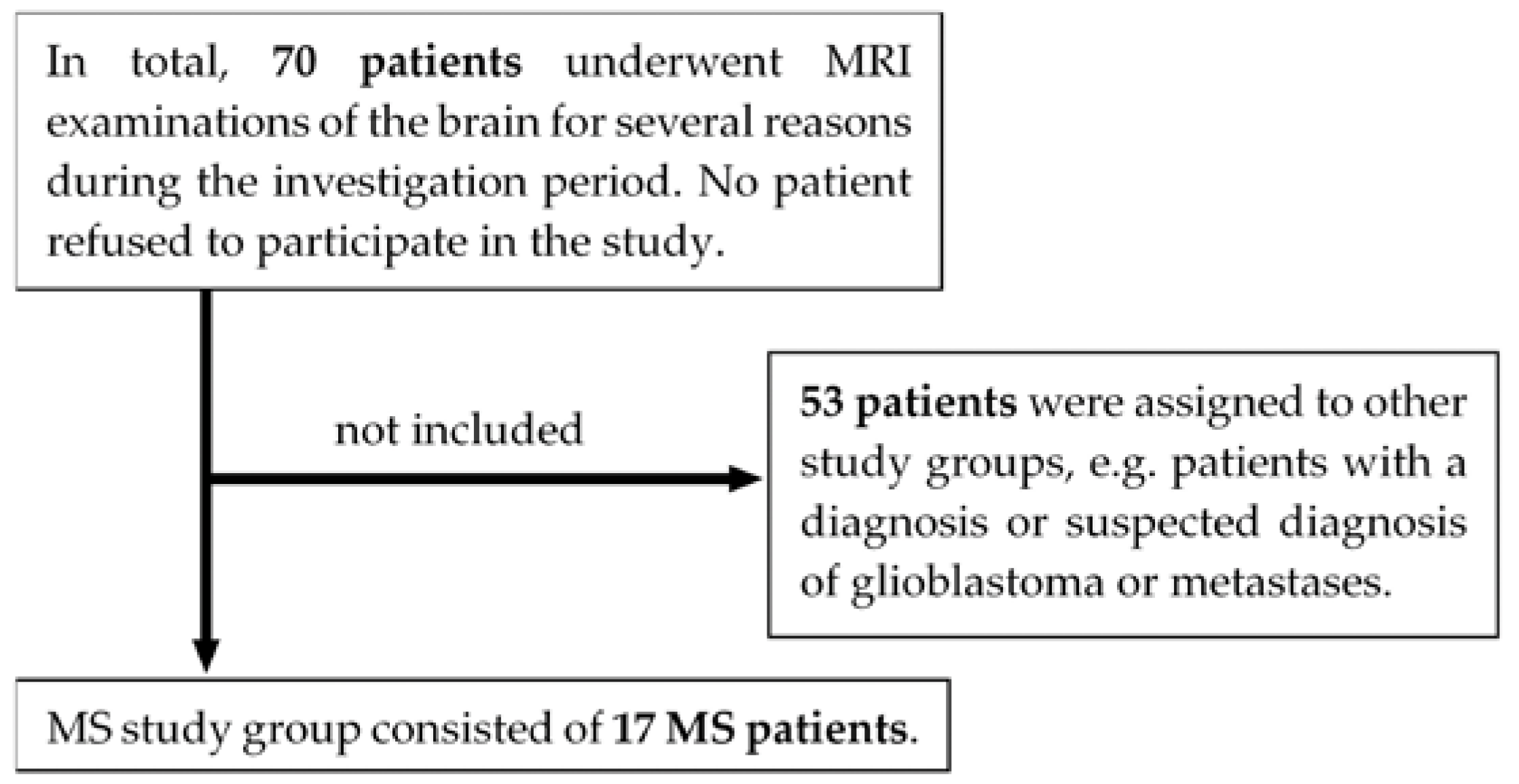

9]. Exclusion criteria were lack of capacity to consent, missing written informed consent, acute stroke in the lysis time window, or general MRI contraindications, such as non-MRI compliant implants or severe claustrophobia. As can be seen in

Figure 1, 17 MS patients underwent 3 T MRI scans of the brain between May 2021 and March 2022. For details on patient characteristics, see

Table 1. All eligible patients gave written informed consent to participate in this voluntary study.

2.2. Imaging Protocol and Image Acquisition

All examinations were conducted using a 3 T MRI scanner (see

Section 2.1). We used a 20-channel head and neck coil and applied our standard protocol for patients with MS, incorporating the following contrasts: 3D T1 magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE), contrast-enhanced 3D T1-MPRAGE, contrast-enhanced axial T1 turbo/fast spin echo (TSE), infratentorial axial T2-TSE, axial DWI, 3D double inversion recovery (DIR), and 3D-T2-FLAIR (FLAIR

3D). In three patients, an axial standard T2-TSE-FLAIR (FLAIR

TSE) sequence was added as well. Additionally, we acquired the ultrafast axial T2w FLAIR

UF research sequence in all patients, along with other ultrafast sequences that are not in the scope of this article (i.e., two native axial T1w contrasts, two contrast-enhanced axial T1w contrasts, axial DWI, and an axial sequence providing a T2*w and a T2w contrast). All native sequences were acquired prior to the contrast agent application, and the standard protocol sequences were acquired in advance of the ultrafast sequences. The acquisition parameters for all three T2w FLAIR sequences (i.e., FLAIR

UF, FLAIR

TSE, and FLAIR

3D) are given in

Table 2. By using the FLAIR

UF sequence, which takes 0:51 min, the acquisition time can be reduced to almost a sixth of the time required for the FLAIR

3D sequence (4:57 min) and nearly a third of the time required for the FLAIR

TSE sequence (2:22 min).

After acquisition of the data and extraction of relevant clinical data, imaging data were de-identified using RSNA Clinical Trial Processor (CTP) software (RSNA CTP Java Version 1.8, Radiological Society of North America, Oak Brook, IL, USA) for further evaluation within this trial.

2.3. FLAIRUF Sequence

The FLAIRUF sequence examined in this study was a T2w inversion-recovery double-shot spin-echo EPI sequence, i.e., k-space data for each image were acquired in two shots with interleaved phase-encoding patterns. Each shot consisted of a spin-echo inversion recovery excitation module followed by a 64-echo readout train. In all three FLAIR sequences (FLAIRUF, FLAIRTSE, and FLAIR3D), the PI acceleration factor was two.

In order to alleviate the deterioration in image quality caused by the above-mentioned acceleration techniques, the FLAIR

UF sequence has several novel features. One of them is a DL-enhanced processing technique that employs a machine-learning-based reconstruction to decrease image noise and residual aliasing [

43,

44,

45,

59]. It was trained on data acquired with a 20-channel head matrix coil at 3 T [

43,

44]. However, the clinical patient images included in our study were not part of the training data. The reconstruction method requires coil sensitivity maps based on the eigenvector-based iterative self-consistent parallel imaging reconstruction technique (ESPIRiT) [

60]. Those maps are calculated using fast low angle shot (FLASH)-based autocalibration scans acquired prior to the slice scans. Furthermore, geometric coil compression was utilized for improving reconstruction performance, reducing reconstruction times [

61]. Another novel feature implemented is magnetization transfer (MT) preparation to improve tissue contrast, as described in [

62]. In addition, the FLAIR

UF sequence utilizes the following techniques to improve image quality, amongst others: Field map based geometric distortion correction [

63,

64], phase correction scans to mitigate residual Nyquist ghosting, flow attenuation gradients to weaken signals from flowing or pulsating fluids, and automated interleaving of inversion and acquisition modules to further optimize the scan efficiency.

2.4. Image Evaluation

Inflammatory lesions and image quality were evaluated by one reader (M.S.), and all ratings were verified by an experienced neuroradiologist (B.B.) in a consensus reading with the first reader for a final decision.

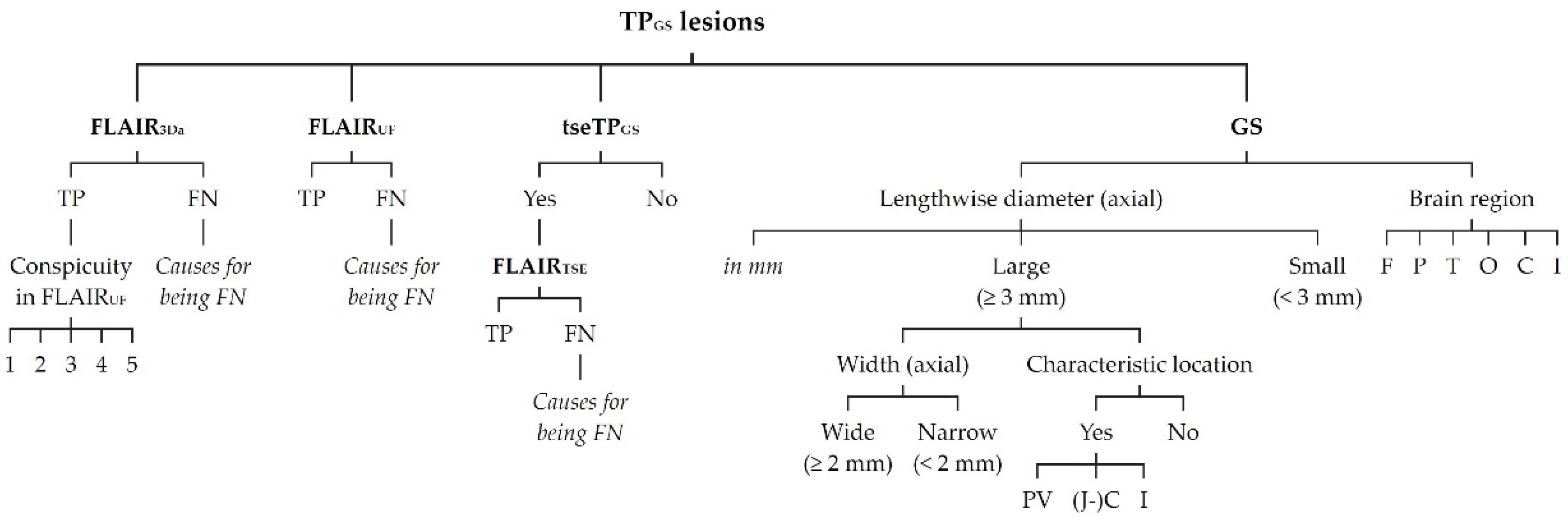

2.4.1. Lesion Assessment

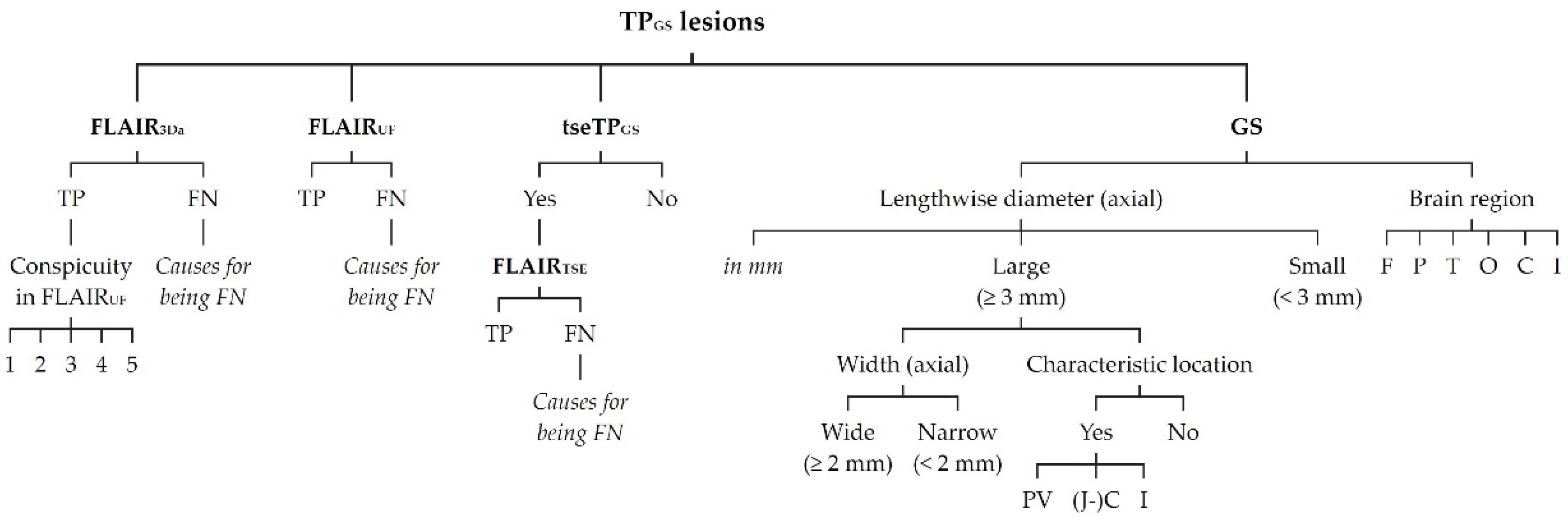

All inflammatory lesions recorded were documented and listed. Identifiers were assigned, using all sequence contrasts available, particularly axial reconstructions including 3D multiplanar reconstructions (MPRs) of FLAIR

3D, DIR, and T1-MPRAGE, plus an axial T2-TSE sequence contrast. Utilization of all these contrasts was referred to as gold standard (GS). Accordingly, the total amount of lesion counts was referred to as true positives using GS (TP

GS). To each TP

GS lesion, the following attributes were assigned (see

Figure 2): 1) clearly detectable as a lesion using only the axial reconstruction of FLAIR

3D (FLAIR

3Da), i.e., true positive in FLAIR

3Da (TP

3Da), or not clearly detectable as a lesion using only FLAIR

3Da, i.e., false negative in FLAIR

3Da (FN

3Da); 2) clearly detectable as a lesion using only the FLAIR

UF images (TP

UF), or not clearly detectable as a lesion using only the FLAIR

UF images (FN

UF); 3) lesion size, i.e., lengthwise axial diameter (mm, to the nearest tenth); 4) lesion size category, i.e., lengthwise axial diameter (large [≥ 3 mm] or small [< 3 mm]); 5) location, i.e., brain region (frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, central [insular lobe, corpus callosum, basal nuclei, diencephalon], or infratentorial [brainstem, cerebellum]).

The following attributes were assigned to only a particular subset of the TP

GS lesions (see also

Figure 2): 1) lesion width (wide [≥ 2 mm] or narrow [< 2 mm]; axial) and lesion location, according to Barkhof et al. and the McDonald criteria [

6,

7,

8,

9,

13,

65] (characteristic [periventricular, juxta-/cortical, infratentorial] or not characteristic) were both assigned to large (≥ 3 mm) TP

GS lesions only; 2) lesion detectability in FLAIR

TSE (TP

TSE or FN

TSE) was assigned to the subset of TP

GS recorded with FLAIR

TSE (tseTP

GS); 3) lesion conspicuity in FLAIR

UF compared with FLAIR

3Da counterpart, using an ordinal five-point Likert scale (1 = better/larger in the FLAIR

UF images; 2 = equal; 3 = better in the FLAIR

3Da images, but classified as a lesion using only the FLAIR

UF images; 4 = better in the FLAIR

3Da images and classified as no lesion using only the FLAIR

UF images; 5 = FLAIR

3Da lesion that is not at all visible in the FLAIR

UF images), was only assigned to the TP

3Da lesions; 4) presumed causes for not being detected in FLAIR

UF were only assigned to the FN

UF lesions; 5) presumed causes for not being detected in FLAIR

3Da were only assigned to the FN

3Da lesions; 6) presumed causes for not being detected in FLAIR

TSE were only assigned to the FN

TSE lesions.

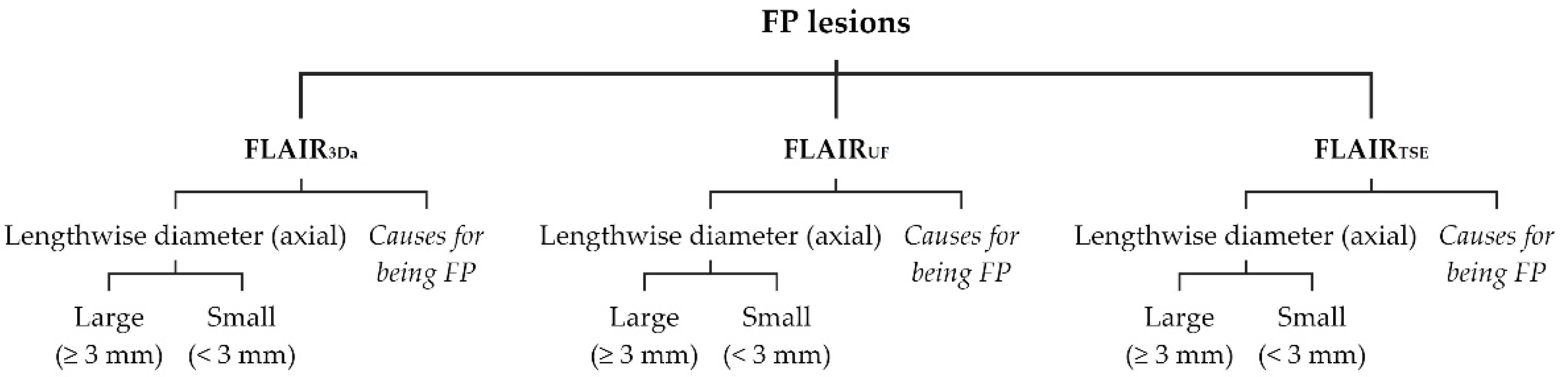

False positive (FP) lesions were recorded and listed separately for FLAIR

UF (FP

UF), FLAIR

3Da (FP

3Da), and FLAIR

TSE (FP

TSE). To each FP lesion, the following attributes were assigned (see

Figure 3): 1) size category, i.e., lengthwise axial diameter (large [≥ 3 mm] or small [< 3 mm]); 2) presumed causes for being mistaken for a lesion.

2.4.2. Image Quality Assessment

For the purpose of general image quality assessment, three parameters were employed: signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR), and artifacts. FLAIRUF, FLAIR3Da and FLAIRTSE slice series were each rated for SNR and CNR on an ordinal five-point Likert scale (1 = very good; 2 = good; 3 = acceptable; 4 = mediocre but diagnostic; 5 = poor and non-diagnostic). Besides, all artifacts in the FLAIRUF, FLAIR3Da, and FLAIRTSE images were assessed based on quantity and quality. To this end, FLAIRUF , FLAIR3Da, and FLAIRTSE sequences were classified as to their limitations of diagnostic information in the respective artifact region, using an ordinal five-point Likert scale (0 = No artifact; 1 = Artifact exists, but diagnostic information is not limited; 2 = Artifact exists, and diagnostic information is slightly limited in the artifact region; 3 = Artifact exists, and diagnostic information is limited in the artifact region; 4 = Artifact exists, and diagnostic information is severely limited in the artifact region).

To assess location-dependent SNR and CNR within the FLAIRUF images, the following attributes were assigned to each TPGS lesion (see previous section): 1) SNR in the vicinity of the lesion (standard or substandard; with reference to the average SNR in FLAIRUF); 2) CNR in the vicinity of the lesion (standard or substandard; with reference to the average CNR in FLAIRUF).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed post hoc using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics Version 29.0.0.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Excel (Microsoft Excel for Microsoft 365 MSO Version 2305, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA).

In order to compare lesion detection in FLAIRUF with lesion detection in FLAIR3Da, contingency tables were created, correlating TP and FN lesion counts. Also, the counts and presumed causes of FN and FP lesions were contrasted. The sensitivity values (TP/[TP+FN]) and positive predictive values (PPVs; TP/[TP+FP]) as to lesion detection were specified including their 95% Clopper-Pearson confidence intervals (CIs), and FN lesion counts were compared using McNemar’s test (Excel). The same analyses were performed to compare the lesion detection in FLAIRUF with the lesion detection in FLAIRTSE. To ascertain factors that affect the lesion conspicuity within the FLAIRUF images, conspicuity ratings were compared, grouped by lesion size and location, using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and the Kruskal-Wallis test (SPSS). With the aim to investigate whether conspicuity ratings might possibly have been biased by lesion size variations among the location groups, lengthwise diameters of the TP3Da lesions were reported for each location (mean/95% CI, standard deviation [SD], median) and compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test (SPSS). Moreover, large TP3Da lesions (≥ 3 mm) for each brain region were divided into wide (≥ 2 mm) and narrow (< 2 mm) lesions and were further differentiated by conspicuity ratings.

For the purpose of contrasting the ordinal SNR, CNR and artifact ratings in the FLAIRUF and FLAIR3Da image series, results were reported as median plus interquartile range (IQR) as well as mean ± SD; a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was also performed (SPSS). Similarly, results were reported for comparing FLAIRUF with FLAIRTSE image series. To ascertain positional factors that affect the SNR and CNR within the FLAIRUF images, the dichotomous SNR and CNR ratings were grouped by location; the proportions of the substandard ratings were determined for each group including 95% Clopper-Pearson CIs. Groups were compared using the chi-squared test (Excel).

In [

66] Bender et al. stated that multiple testing corrections are not necessarily required for exploratory trials generating (diverse) hypotheses. Accordingly, adjustment for multiple comparisons was waived for this study. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings of This Study

This study investigated an ultrafast axial DL-enhanced EPI-FLAIR (FLAIRUF) MRI sequence in RRMS patients. The FLAIRUF sequence reduced the acquisition time to almost a sixth of the time required for conventional three-dimensional FLAIR (FLAIR3D) acquisitions and nearly a third of the time required for axial standard TSE-FLAIR (FLAIRTSE) acquisitions. With regard to the detection of inflammatory brain lesions, we did not observe any significant differences between the FLAIRUF images and the FLAIR3Da images in either sensitivity for wide large lesions (≥ 3 mm × ≥ 2 mm) or PPV for all large lesions (≥ 3 mm total) despite high lesion numbers. The same applies to the sensitivity of large lesion detection (≥ 3 mm total) in the FLAIRUF images compared to the FLAIRTSE images. Lesion conspicuity did not differ significantly between brain regions in the FLAIRUF images, except for occipital large lesions (superior results) and central large lesions (inferior results). To our knowledge, this study represents the first in-depth quantitative and qualitative evaluation of inflammatory lesions using a DL-enhanced EPI-FLAIR sequence.

4.2. Significance of MRI and Ultrafast MRI

In MS patients, severity of the clinical course is influenced by the start and choice of disease-modifying therapy (DMT). Notably, early treatment start or treatment escalation delays disease progress of both clinically definite multiple sclerosis (CDMS) and clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) in particular [

67]. To decide on adequate therapeutic strategies depending on disease activity, MRI plays a major role [

10,

67,

68]. McDonald diagnostic criteria are based on number, location, and size of lesions as well as temporal changes of lesions [

6,

7,

8,

9]. A lesion size of over 3 millimeters is deemed to be appropriate to account for the diagnostic criteria [

14]. In order to adapt DMT without delay, specific monitoring intervals are recommended [

10]. Notably, CIS patients benefit from very tight follow-up MRI examinations, particularly during the first year [

10,

69]. Nonetheless, overall MRI scan capacity is far from enough to satisfy demand in numerous parts of the world, and waiting times usually exceed the maximum recommended time, thus worsening medical outcomes and increasing the economic costs [

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75]. Against this background, utilizing DL-enhanced EPI-FLAIR sequences may be a promising approach to ameliorate treatment quality while at the same time meeting diagnostic requirements.

4.3. Limitations of the FLAIRUF Images

Despite its remarkable capabilities, the FLAIRUF images still have three primary limitations. First, lesion size is a limiting factor for the FLAIRUF images, particularly in comparison with the FLAIR3Da images. Almost every second small lesion (< 3 mm) and more than every fifth narrow large lesion (≥ 3 mm × < 2 mm) could not be detected using the FLAIRUF images. Additionally, out of all presumed small lesions (< 3 mm), about a quarter detected using the ultrafast sequence variant were false-positives. There may be one main cause of those limitations: the relatively large slice thickness including slice gaps in this context. It should be noted that this parameter did even influence the detection of large lesions (≥ 3 mm).

Secondly, lesion location may represent another limiting factor in the FLAIRUF images. There are several location-dependent factors: 1) SNR deterioration towards the central regions of the images, and simultaneously, SNR enhancement towards marginal regions such as the occipital lobe (even though it appears similar compared with the FLAIRTSE images); 2) some limits of CNR, which primarily become apparent when depicting regions that require high spatial resolution and low slice thickness, particularly the cerebellum with its fine folium-sulcus texture (even though the overall CNR only seems marginally reduced compared with the FLAIRTSE images); 3) pulsatile flow artifacts, which mostly affect image quality by mimicking infratentorial lesions (even though infratentorial pulsation artifacts appear to limit image quality to a similar extent using FLAIR3Da or FLAIRTSE, mostly by masking potential lesions); 4) spatial distortion artifacts (frontal, frontobasal, temporopolar, and infratentorial), which may conceal potential lesions; 5) relatively large slice thickness including slice gaps, which may hinder the distinction between lesions and physiological brain structures at certain locations, particularly near the cortex.

Thirdly, there is an additional limitation apart from those associated with lesion assessment: most structures outside the parenchyma are insufficiently delineated in the FLAIRUF images, such as osseus structures, air-containing structures, or adipose tissue. Reasons for this may be susceptibility artifacts and fat suppression. However, the optic nerves, for example, are clearly distinguishable, and fat suppression might even be advantageous in terms of assessing optic neuritis. Though, this remains speculative and beyond the scope of our study.

4.4. Considerations on Ratings for Lesion Conspicuity in FLAIRUF

Ratings for lesion conspicuity in FLAIR

UF (

Section 3.2.3) were intended to compare results among the brain regions within the FLAIR

UF images. Since a kind of reference was required (FLAIR

3Da), the ratings appear to be biased by position-dependent lesion conspicuity in FLAIR

3Da. However, those potential position-dependent differences did not exist at all in the FLAIR

3Da images, and image quality was excellent across all regions. The only exception was infratentorial, where a few lesions were masked by pulsation artifacts (FN lesions); all the other infratentorial lesions were not affected in any way. In order to prevent FLAIR

3Da-biased (infratentorial) conspicuity ratings in FLAIR

UF, assessments were confined to TP

3Da lesions instead of TP

GS lesions.

As stated previously, the conspicuity ratings do not seem to be biased by lesion size variations among the brain regions, with one exception: ratings of infratentorial large lesions might have been biased towards falsely positive results, since the proportion of wide lesions to narrow lesions was greater compared to all the other regions, while at the same time, the conspicuity ratings appeared to be superior for wide lesions. That might be an explanation for why the conspicuity ratings do not reflect the substandard SNR and CNR ratings for this region. That discrepancy did not exist in other locations.

Finally, localization-dependent conspicuity results in FLAIRUF could only be demonstrated for large lesions, not for small lesions. The underlying cause could be slice thickness and slice gaps to be the limiting factors for small lesion conspicuity, which is independent of the position. SNR-related positional dependence appears to have a subordinate role in this context. For instance, large central lesions stood out with a comparatively high proportion of grade 3 ratings (conspicuity better in the FLAIR3Da images but classified as a lesion using only the FLAIRUF images), but for small central lesions, that proportion was relatively low in favor of grade 4 and 5 ratings (not classified as a lesion using FLAIRUF). In all the other brain regions, on the contrary, large lesions predominantly exhibited grade 1 and 2 ratings (conspicuity at least equal in the FLAIRUF images), i.e., comparatively small proportions of grade 3 ratings, while for small lesions, that proportion was considerably lower in favor of grade 4 and 5 ratings, comparable to the central small lesion group. However, for occipital and infratentorial small lesions, the counts were insufficient to draw further conclusions regarding position-dependent conspicuity of small lesions.

4.5. Outcomes Correlated with Technical Features

The above-mentioned characteristics of the FLAIRUF images arise from specific sequence properties. To begin with, there is a correlation between slice thickness (slice gap included) and visibility of small lesions: if the lesion size is smaller than the slice thickness, signal intensity will decrease and with it the lesion contrast due to the partial volume effect. At some point, the lesion signal will disappear completely if lesions are too small. Thus, there is a direct correlation between that threshold and slice thickness.

Apart from the partial volume effect, EPI-related CNR loss seems to be sufficiently counterbalanced by MT preparation [

62]. Here, MT pulses serve as saturation pulses selectively affecting macromolecular protons and adjacent water molecules to enhance image contrast [

76].

In EPI, the SNR is diminished due to substantial signal loss during its long echo train, and lack of refocusing pulses combined with rapid T2* signal decay. Nevertheless, aided by the DL reconstruction, the SNR in FLAIR

UF appeared similar compared to FLAIR

TSE. In both image variants, the SNR (and related lesion conspicuity) decreased similarly towards the center of the image, owing to coil dependency in PI [

77,

78,

79]. Accordingly, there is an inversely proportional relationship between SNR and the geometry (g)-factor [

77,

78,

79]. This factor is affected by coil sensitivity and voxel location, usually exhibiting the greatest values in the center of the image [

77,

78,

79]. Although the DL reconstruction method was designed to compensate for this specific factor, its SNR gains were eventually limited, especially in combination with stringent requirements for slice thickness. In contrast, the excellent SNR in FLAIR

3D can be attributed to the fact that in 3D acquisitions, the complete volume is excited with each shot.

Besides, the long readout duration in EPI has another significant impact on image quality (together with the very low pixel bandwidth along the phase-encoding direction in EPI): increased sensitivity to susceptibility artifacts [

80]. If a substance is located in an external homogeneous magnetic field, the magnetic field lines will either be dispersed (e.g., bone tissue) or concentrated (e.g., air or metal) around that material, depending on its susceptibility properties [

81]. Consequently, the magnetic field is disturbed in areas where susceptibility differences are large (e.g., air-filled bones), leading to an accelerated phase coherence loss and T2* signal decay, on the one hand, and accumulation of phase errors along with positioning errors in the phase encoding direction, on the other [

2]. This explains the appearance of both distortion artifacts, particularly arising in the vicinity of air-tissue interfaces in the phase encoding direction, and signal decrease in tissues surrounding the brain parenchyma, caused by differences in magnetic susceptibility. In strong magnetic fields, susceptibility differences further increase, and phase incoherences accumulate to a greater extent over the duration of the echo train [

2,

82,

83]. In contrast, SNR, CNR, spatial resolution and scan time benefit from a strong magnetic field strength [

82,

83].

Apart from susceptibility effects, there is another reason for signal decrease in non-parenchymal tissues in FLAIR

UF: fat-suppression. It is essential for low-segmented EPI in order to avert chemical shift artifacts [

2]. Those artifacts derive from spatial signal misregistration owing to frequency differences between protons in fat and water. Without fat-suppression, however, the implicitly low pixel bandwidth along the phase-encoding direction in EPI would lead to accumulation of phase shifts between fat and water, resulting in chemical shift artifacts in the phase encoding direction [

80,

84]. With singular exceptions located close to the frontal air-tissue interfaces, we did not observe any chemical shift artifacts caused by incomplete fat suppression in the FLAIR

UF images.

In addition, we observed other artifacts caused by phase errors: pulsatile flow artifacts. They usually occur along the phase encoding direction [

85]. Accordingly, we were able to relate most artifacts to structures containing flowing blood or liquor in all three image variants (FLAIR

UF, FLAIR

TSE, and FLAIR

3Da), each of them revealing distinctive characteristics. Typically, the artifacts either occurred around blood vessels, particularly around infratentorial venous sinuses (FLAIR

UF), or they were aligned in positions shifted from blood vessels along the phase encoding direction (FLAIR

UF, FLAIR

3Da, and FLAIR

TSE). In the FLAIR

UF and FLAIR

3Da images, artifacts were shifted along the anterior-posterior axis, while in the FLAIR

TSE images, artifacts were shifted along the left-right axis (compare

Table 2). In the FLAIR

UF images, replicas were shifted at intervals of a quarter of the field of view (according to the PI acceleration factor of two and the two-segmented k-space). In the FLAIR

3Da and FLAIR

TSE images, artifacts manifested as grainy or streaky bands. However, in terms of limitations of diagnostic information caused by pulsation artifacts, the FLAIR

UF images were not inferior.

Finally, there were three more rare minor artifacts, two of which could be seen in the FLAIRUF images: residual aliasing and spike artifacts. The former is related to PI reconstruction, and the latter is related to the rapid switching of gradients in EPI. The third artifact type, minor motion artifacts caused by subject movement, could not be observed in the FLAIRUF images, but in one FLAIR3Da and one FLAIRTSE image series. It is related to the longer acquisition time in FLAIR3D and FLAIRTSE. In this regard, EPI is undeniably at an advantage.

4.6. Limitations of the Study

There are some limitations of this study that might have affected our results. To begin with, the methodological approach may be associated with some selection bias. Examinations were carried out using one specific scanner, and the patient sample may be biased by common appointment scheduling practices in terms of disease manifestation or severity (medium or low disease activity in an outpatient follow-up setting). Although no patient declined to participate in the study, there were a couple of patients that could not be included from the outset due to the associated additional expenditure of time. That probably led to further sampling bias (e.g., age, sex, clinical condition). In particular, the sex ratio in our study was atypical (compare

Section 1 and

Section 2.1). Aside from selection bias, there were more factors limiting the external validity, such as the single-center study design using only one single 3 T MRI scanner from one specific manufacturer.

Moreover, there might have been some observer bias inherent to this study, despite all efforts and critical appraisal. In this regard, implementing image blinding would not have had a positive effect due to the significantly different and easily distinguishable nature of the images, and the study was designed for subjective side-by-side comparisons. Generally, radiological readers’ assessments may also depend on their level of experience with the FLAIRUF image characteristics.

Even though the number of participants was modest, the lesion counts were substantial, providing high statistical power. Nevertheless, there is an important limitation from a statistical point of view: Statistically, several lesions within one subject are no independent observations, because they are bound to both the same individual and time of scan. Accordingly, lesion conspicuity could possibly have been influenced by parameters that might have varied among the individuals or scans, which may have induced statistical bias. Also, non-significant test results are indications, but not proof of equality. So, in large part, the results of the study are indicative, not conclusive. However, variances among the image data appeared to play a minor role, at most, and non-significant results are more meaningful when based on a large sample size. Methodologically, it would have been precise either to rate all lesions from one image series as a whole or to randomly select and analyze only one lesion from each image series after recording all existing lesions. However, the former procedure would have provided highly inaccurate outcomes, and the latter procedure would have provided relatively meaningless test results (if statistically non-significant), owing to the sample size. In this study, the small FLAIRTSE sample size only provides indicative findings: results were either statistically tested, accepting the possibility of an increased type II error, or statistical testing was omitted.

In the future, further prospective studies and confirmatory trials with larger numbers of participants and more diverse cohorts, various scanners, and modified reconstruction and acquisition methods need to be conducted. Further radiological reading should possibly include separate image assessments instead of side-by-side comparisons. Plus, other studies covering MS patients might consider additional contrasts (e.g., contrast enhanced T1w sequences), orientations (sagittal, coronal), or regions (such as the spine or the optic nerves).

4.7. Future Perspectives

All in all, our results suggest that FLAIRUF may be an appropriate approach for assessing cerebral inflammatory lesions. Diagnostic performance did not prove inferior compared to conventional FLAIR3D in terms of MS lesion detection (≥ 3 mm × ≥ 2 mm) in just about a sixth of the time. This demonstrates the tremendous progress made in the field of EPI. In the light of extensive waiting times for MR examinations and patient-dependent constraints to carry them out, for example claustrophobia or inability to remain motionless (i.e., children or disease- and age-related obstacles), ultrafast imaging seems an essential tool. However, there are still some challenges to overcome in refining this technique while aiming to combine high resolution with high SNR at high field strengths along with low artifacts.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study participants. Note. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; MS = multiple sclerosis.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study participants. Note. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; MS = multiple sclerosis.

Figure 2.

Classification of TPGS lesions. Note. TPGS lesions = total number of true positive lesions detected using all contrasts available (gold standard); FLAIR3Da = axial reconstruction of FLAIR3D; FLAIRUF = ultrafast axial FLAIR; tseTPGS = subset of TPGS recorded with FLAIRTSE; FLAIRTSE = axial standard TSE-FLAIR; GS = utilization of all contrasts available, particularly T2-FLAIR, T1, and T2; TP = true-positives; FN = false-negatives; 1 = better/larger in the FLAIRUF images compared to FLAIR3Da; 2 = equal compared to FLAIR3Da; 3 = better in the FLAIR3Da images, but classified as a lesion using only the FLAIRUF images; 4 = better in the FLAIR3Da images and classified as no lesion using only the FLAIRUF images; 5 = FLAIR3Da lesion that is not at all visible in the FLAIRUF images; PV = periventricular; (J-)C = (juxta-)cortical; I = infratentorial (brainstem, cerebellum); F = frontal; P = parietal; T = temporal; O = occipital; C = central (insular lobe, corpus callosum, basal nuclei, diencephalon).

Figure 2.

Classification of TPGS lesions. Note. TPGS lesions = total number of true positive lesions detected using all contrasts available (gold standard); FLAIR3Da = axial reconstruction of FLAIR3D; FLAIRUF = ultrafast axial FLAIR; tseTPGS = subset of TPGS recorded with FLAIRTSE; FLAIRTSE = axial standard TSE-FLAIR; GS = utilization of all contrasts available, particularly T2-FLAIR, T1, and T2; TP = true-positives; FN = false-negatives; 1 = better/larger in the FLAIRUF images compared to FLAIR3Da; 2 = equal compared to FLAIR3Da; 3 = better in the FLAIR3Da images, but classified as a lesion using only the FLAIRUF images; 4 = better in the FLAIR3Da images and classified as no lesion using only the FLAIRUF images; 5 = FLAIR3Da lesion that is not at all visible in the FLAIRUF images; PV = periventricular; (J-)C = (juxta-)cortical; I = infratentorial (brainstem, cerebellum); F = frontal; P = parietal; T = temporal; O = occipital; C = central (insular lobe, corpus callosum, basal nuclei, diencephalon).

Figure 3.

Classification of FP lesions. Note. FP = false positive; further abbreviations as in

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Classification of FP lesions. Note. FP = false positive; further abbreviations as in

Figure 2.

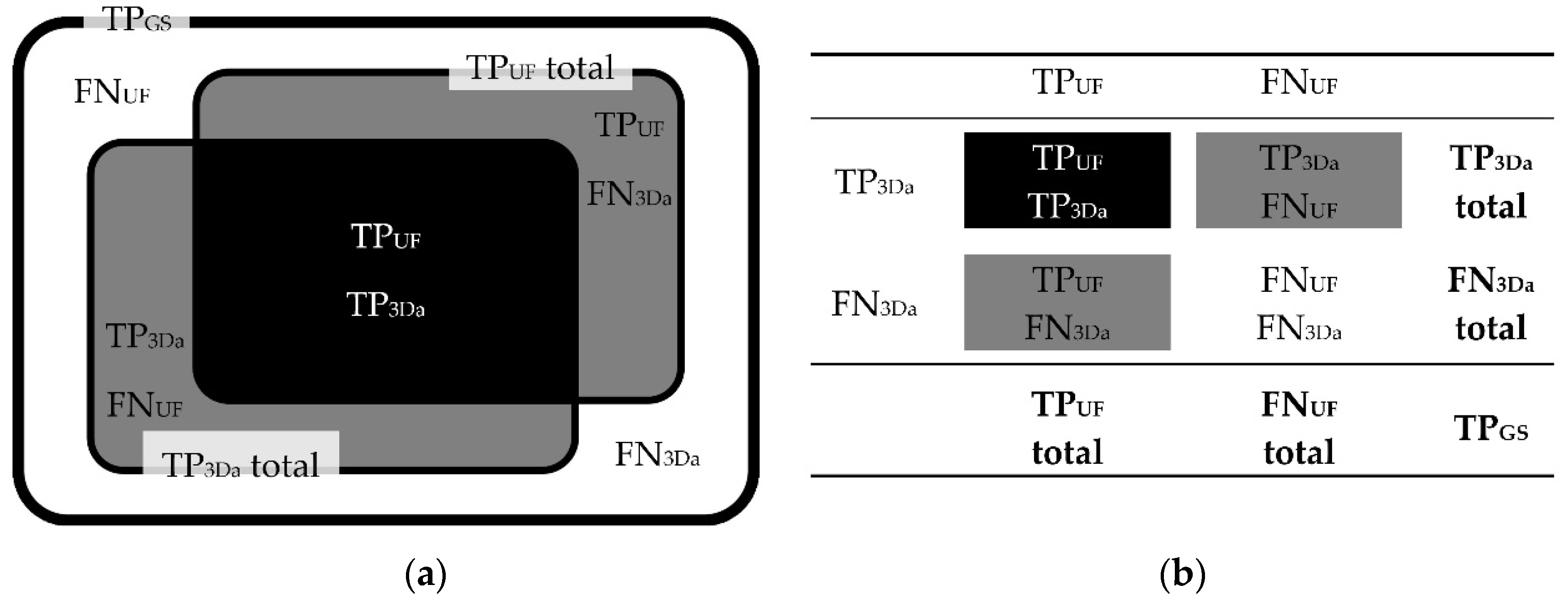

Figure 4.

Correlations between TPUF, FNUF, TP3Da, FN3Da, and TPGS lesion counts. Schematic illustration (a) and contingency table (b). Note. TPGS = number of true positive lesions detected using all contrasts available (gold standard); TPUF = true positive lesions detected in the FLAIRUF images; FNUF = false negative lesions using the FLAIRUF images; TP3Da = true positive lesions detected in the FLAIR3Da images; FN3Da = false negative lesions using the FLAIR3Da images.

Figure 4.

Correlations between TPUF, FNUF, TP3Da, FN3Da, and TPGS lesion counts. Schematic illustration (a) and contingency table (b). Note. TPGS = number of true positive lesions detected using all contrasts available (gold standard); TPUF = true positive lesions detected in the FLAIRUF images; FNUF = false negative lesions using the FLAIRUF images; TP3Da = true positive lesions detected in the FLAIR3Da images; FN3Da = false negative lesions using the FLAIR3Da images.

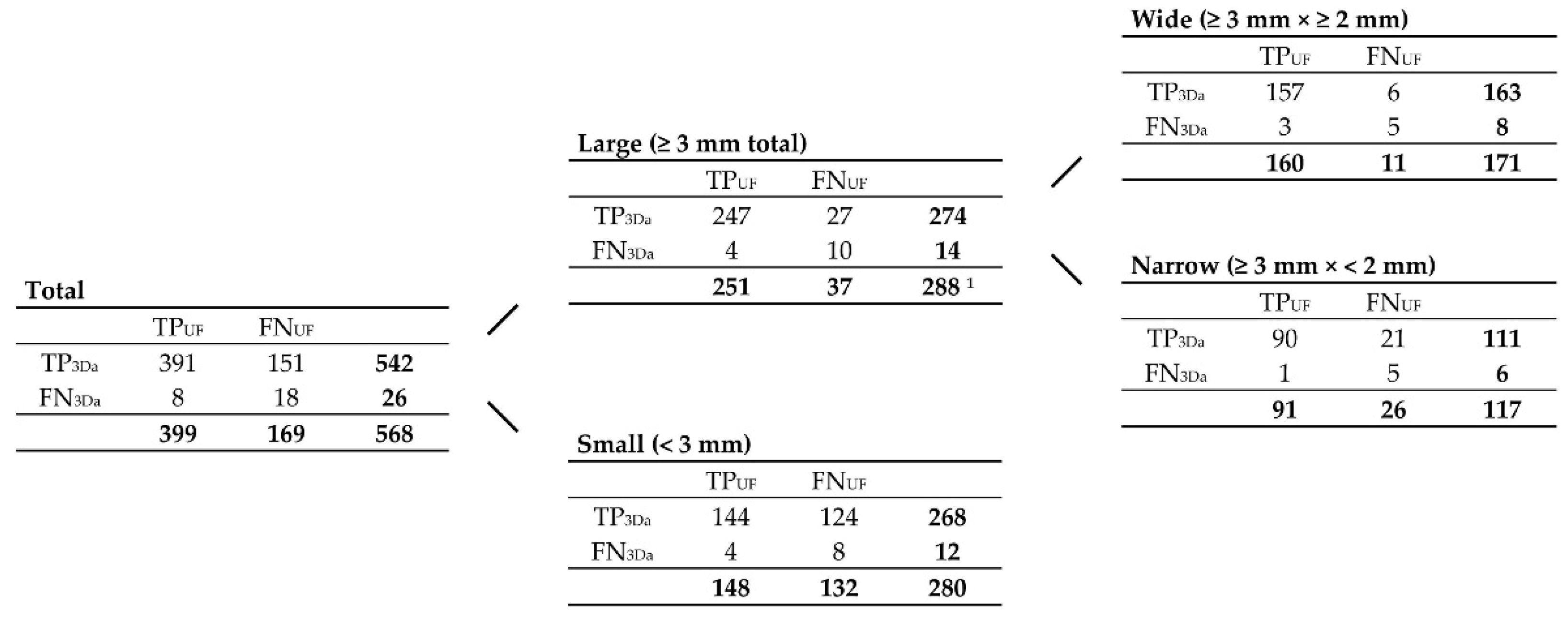

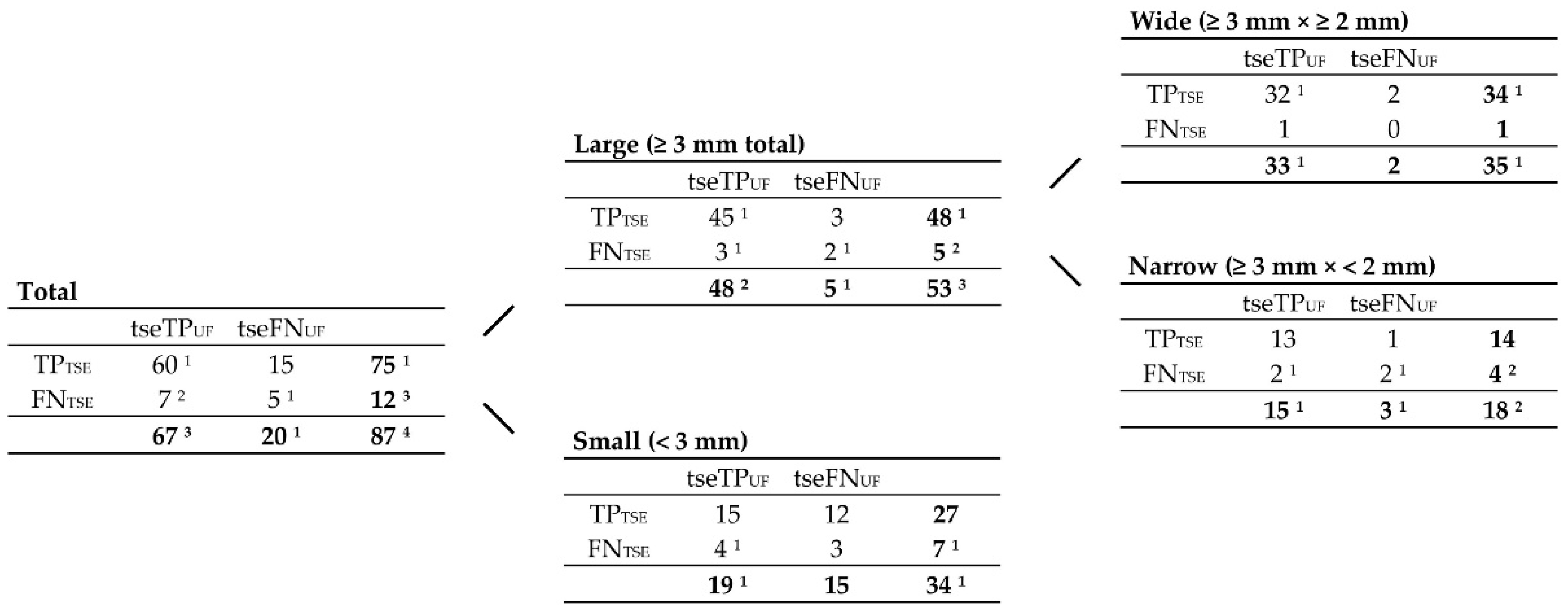

Figure 5.

Contingency tables correlating TP

UF, FN

UF, TP

3Da, FN

3Da, and TP

GS lesion counts, grouped by size, according to

Figure 4. Note. Abbreviations as in

Figure 4.

1 191 of them were ‘characteristic MS lesions’, including 109 periventricular lesions, 44 infratentorial lesions, and 38 (juxta-)cortical lesions.

Figure 5.

Contingency tables correlating TP

UF, FN

UF, TP

3Da, FN

3Da, and TP

GS lesion counts, grouped by size, according to

Figure 4. Note. Abbreviations as in

Figure 4.

1 191 of them were ‘characteristic MS lesions’, including 109 periventricular lesions, 44 infratentorial lesions, and 38 (juxta-)cortical lesions.

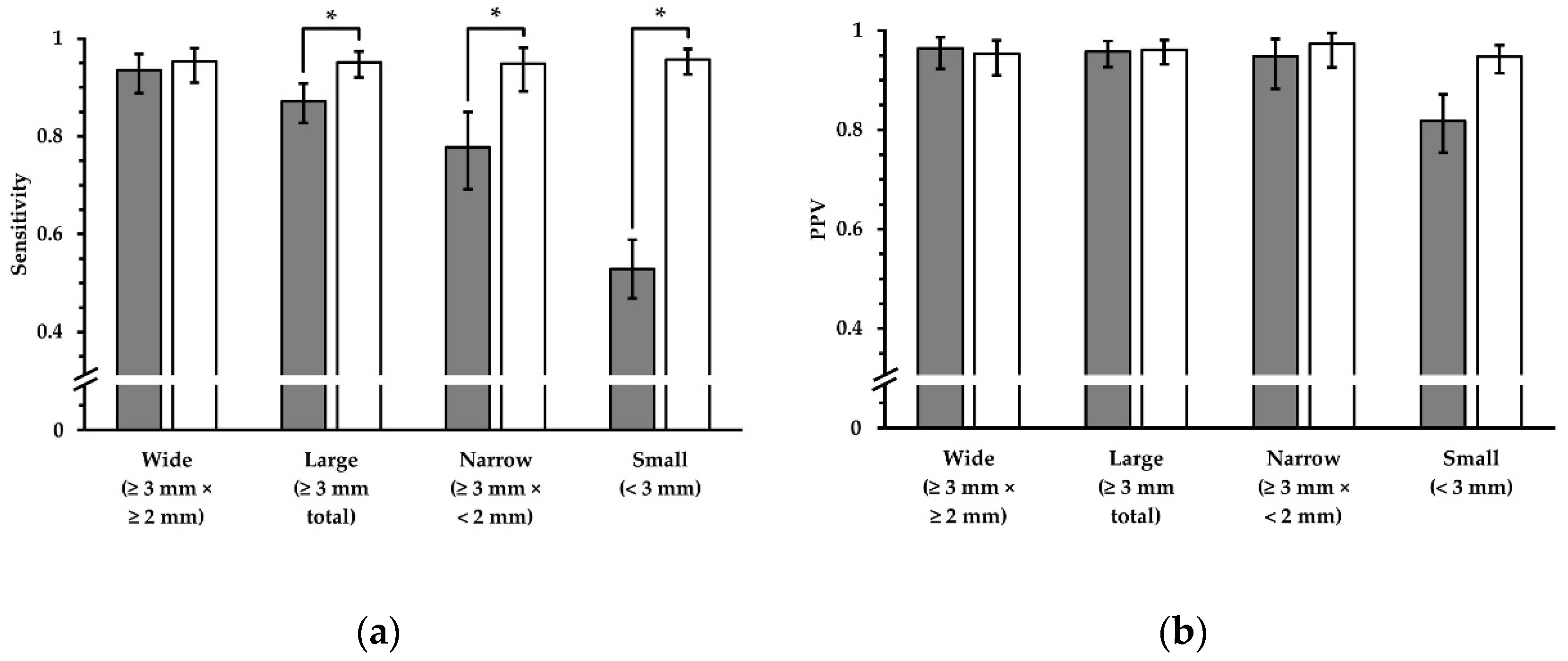

Figure 6.

Sensitivity and PPV in terms of lesion detection, using FLAIR

UF images (gray) and FLAIR

3Da images (white). Four groups, which represent different lesion diameters, are displayed, respectively. The additional error bars denote the 95% CIs. (

a) For wide lesions, no significant difference in sensitivity could be found. For the groups that comprise smaller lesions, however, the sensitivity was significantly inferior using the FLAIR

UF images, decreasing more and more as a function of lesion diameter. (

b) No significant differences in PPV were found for any of the large lesion groups (large, wide, and narrow). For small lesions, the PPV in the FLAIR

UF images was moderately lower compared to the FLAIR

3Da group (no overlap between confidence intervals). Note. Abbreviations as in

Table 3.* p < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity and PPV in terms of lesion detection, using FLAIR

UF images (gray) and FLAIR

3Da images (white). Four groups, which represent different lesion diameters, are displayed, respectively. The additional error bars denote the 95% CIs. (

a) For wide lesions, no significant difference in sensitivity could be found. For the groups that comprise smaller lesions, however, the sensitivity was significantly inferior using the FLAIR

UF images, decreasing more and more as a function of lesion diameter. (

b) No significant differences in PPV were found for any of the large lesion groups (large, wide, and narrow). For small lesions, the PPV in the FLAIR

UF images was moderately lower compared to the FLAIR

3Da group (no overlap between confidence intervals). Note. Abbreviations as in

Table 3.* p < 0.05.

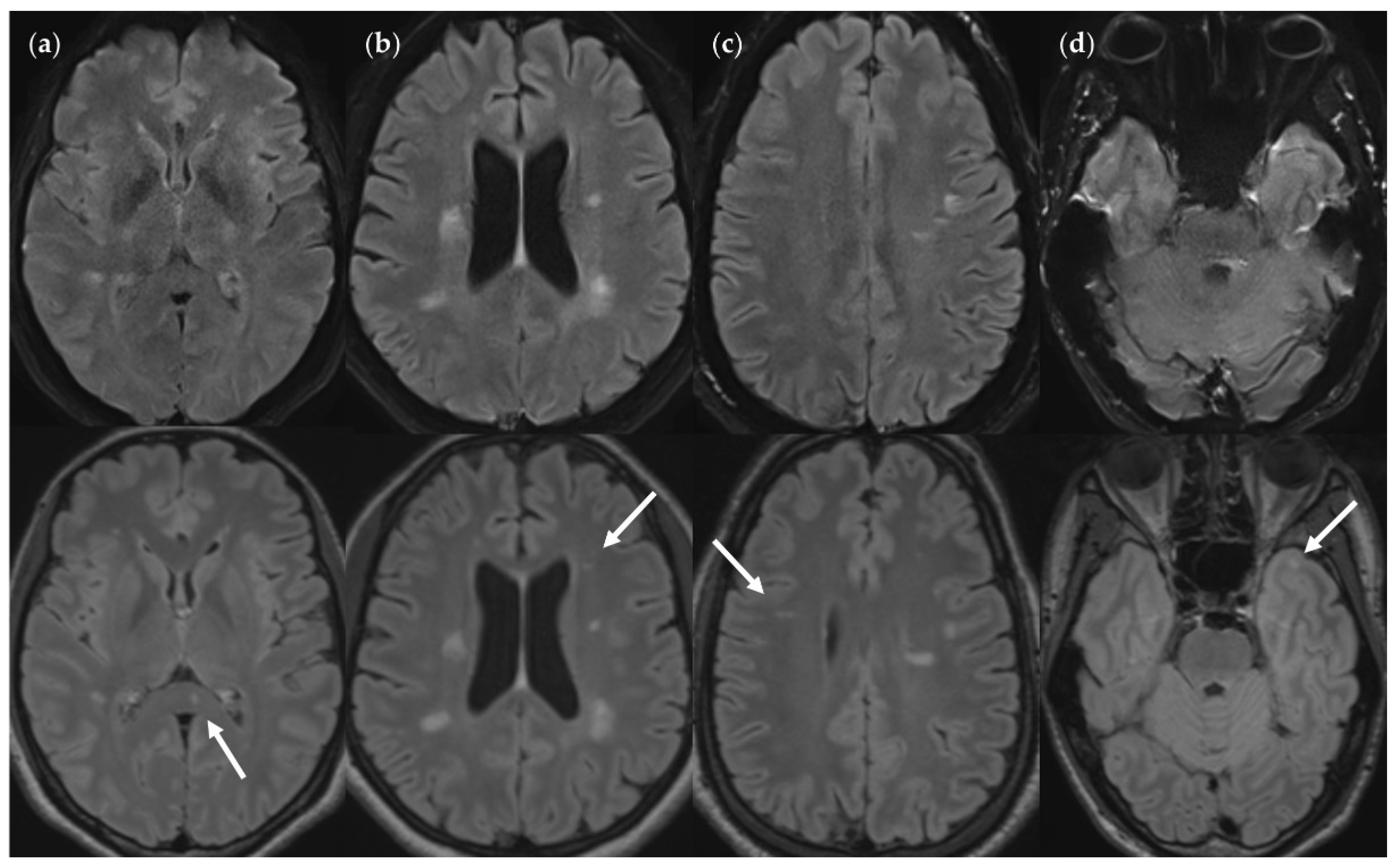

Figure 7.

FNUF lesions (top row) contrasted with their TP3Da counterparts (arrow, bottom row). The images also show several other lesions. (a) Lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum (approx. 3 mm × 2 mm). Causes for it not being detected may be image noise and slice thickness/slice gaps. (b) Left frontal lesion (approx. 3 mm × 1 mm). Causes may be associated with slice thickness/contrast as well as image noise. (c) Thin right frontal lesion (approx. 7 mm × 1 mm). It was mistaken for cortex in the FLAIRUF image. (d) Left temporopolar lesion (approx. 3 mm × 2 mm). It was not recognized as such in the FLAIRUF image owing to commonly occurring distortions within this region.Note. Corresponding slices could not be positioned exactly identically for two reasons: Different slice thicknesses including slice gaps (c) and non-parallel slice inclinations (d).

Figure 7.

FNUF lesions (top row) contrasted with their TP3Da counterparts (arrow, bottom row). The images also show several other lesions. (a) Lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum (approx. 3 mm × 2 mm). Causes for it not being detected may be image noise and slice thickness/slice gaps. (b) Left frontal lesion (approx. 3 mm × 1 mm). Causes may be associated with slice thickness/contrast as well as image noise. (c) Thin right frontal lesion (approx. 7 mm × 1 mm). It was mistaken for cortex in the FLAIRUF image. (d) Left temporopolar lesion (approx. 3 mm × 2 mm). It was not recognized as such in the FLAIRUF image owing to commonly occurring distortions within this region.Note. Corresponding slices could not be positioned exactly identically for two reasons: Different slice thicknesses including slice gaps (c) and non-parallel slice inclinations (d).

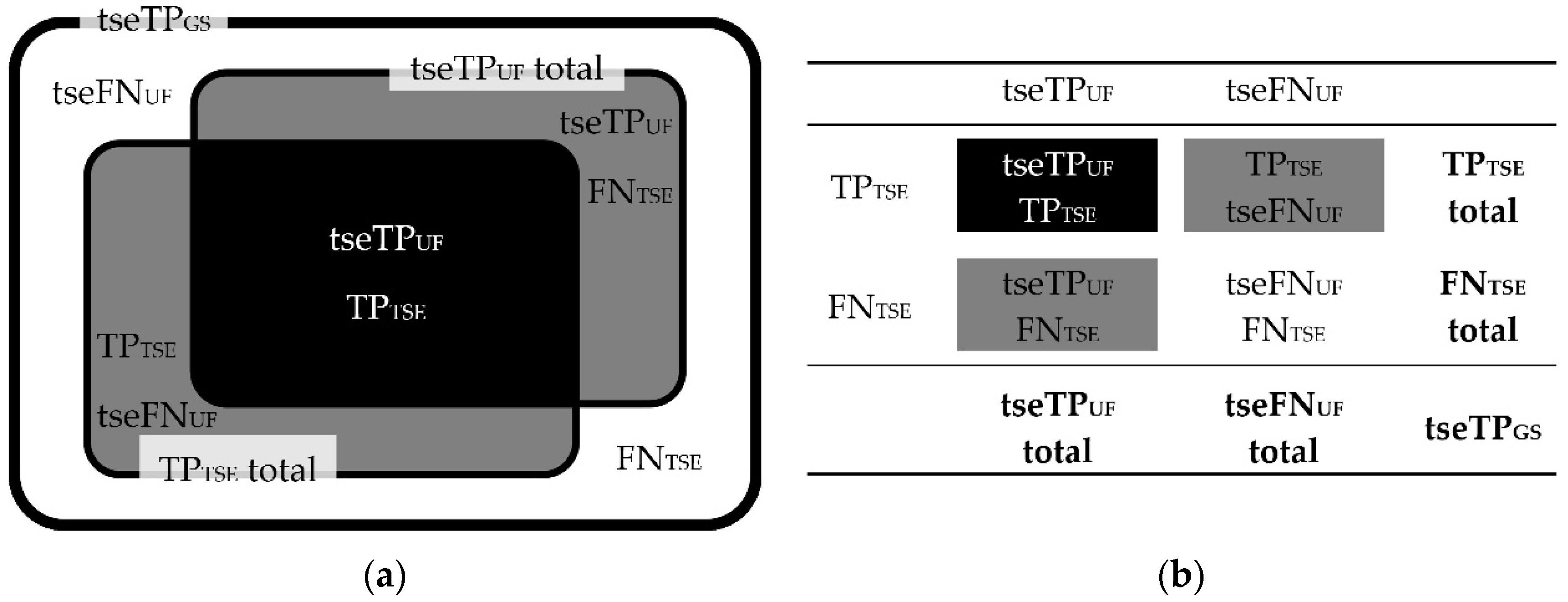

Figure 8.

Correlations between tseTP

UF, tseFN

UF, TP

TSE, FN

TSE, and tseTP

GS lesion counts. Schematic illustration (

a) and contingency table (

b). Note. TP

GS = number of true positive lesions detected using all contrasts available (gold standard); tseTP

GS = subset of TP

GS recorded with FLAIR

TSE; tseTP

UF = corresponding subset of TP

UF recorded with FLAIR

TSE; tseFN

UF = corresponding subset of FN

UF recorded with FLAIR

TSE; TP

TSE = true positive lesions detected in the FLAIR

TSE images; FN

TSE = false negative lesions using the FLAIR

TSE images; further abbreviations as in

Figure 4.

Figure 8.

Correlations between tseTP

UF, tseFN

UF, TP

TSE, FN

TSE, and tseTP

GS lesion counts. Schematic illustration (

a) and contingency table (

b). Note. TP

GS = number of true positive lesions detected using all contrasts available (gold standard); tseTP

GS = subset of TP

GS recorded with FLAIR

TSE; tseTP

UF = corresponding subset of TP

UF recorded with FLAIR

TSE; tseFN

UF = corresponding subset of FN

UF recorded with FLAIR

TSE; TP

TSE = true positive lesions detected in the FLAIR

TSE images; FN

TSE = false negative lesions using the FLAIR

TSE images; further abbreviations as in

Figure 4.

Figure 9.

Contingency tables including a subset of those TP

GS lesions covered by the FLAIR

TSE sequence (tseTP

GS). tseTP

UF, tseFN

UF, TP

TSE, FN

TSE, and tseTP

GS lesion counts are correlated, grouped by size, according to

Figure 8. Note. Abbreviations as in

Figure 8.

1 One was FN using FLAIR

3Da; the rest were TP in FLAIR

3Da.

2 Two were FN using FLAIR

3Da; the rest were TP in FLAIR

3Da.

3 Three were FN using FLAIR

3Da; the rest were TP in FLAIR

3Da.

4 Four were FN using FLAIR

3Da; the rest were TP in FLAIR

3Da. Lesion counts without superscripts were all TP in FLAIR

3Da.

Figure 9.

Contingency tables including a subset of those TP

GS lesions covered by the FLAIR

TSE sequence (tseTP

GS). tseTP

UF, tseFN

UF, TP

TSE, FN

TSE, and tseTP

GS lesion counts are correlated, grouped by size, according to

Figure 8. Note. Abbreviations as in

Figure 8.

1 One was FN using FLAIR

3Da; the rest were TP in FLAIR

3Da.

2 Two were FN using FLAIR

3Da; the rest were TP in FLAIR

3Da.

3 Three were FN using FLAIR

3Da; the rest were TP in FLAIR

3Da.

4 Four were FN using FLAIR

3Da; the rest were TP in FLAIR

3Da. Lesion counts without superscripts were all TP in FLAIR

3Da.

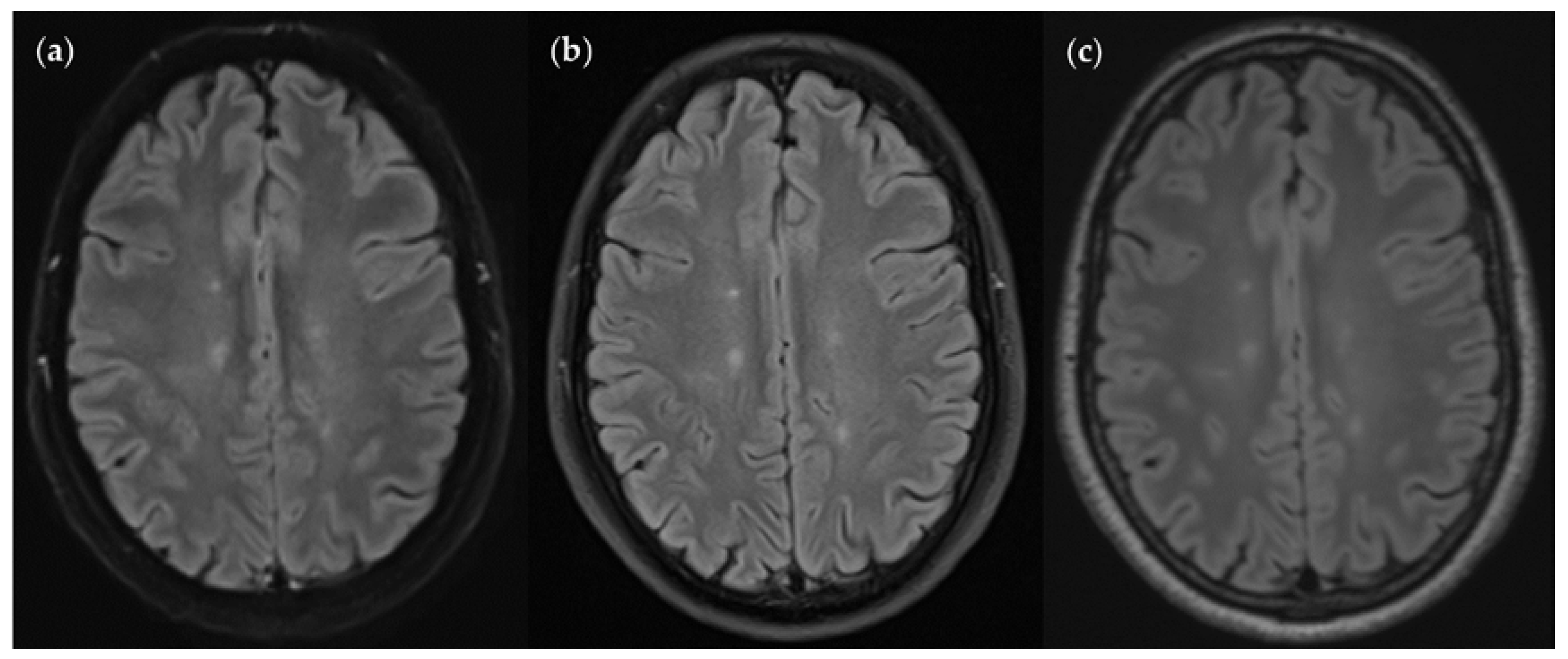

Figure 10.

An MS patient received an MRI scan including three T2w FLAIR sequences: FLAIRUF (a), FLAIRTSE (b) and FLAIR3D (c). Five lesions can be seen in each picture, situated in the frontoparietal region.

Figure 10.

An MS patient received an MRI scan including three T2w FLAIR sequences: FLAIRUF (a), FLAIRTSE (b) and FLAIR3D (c). Five lesions can be seen in each picture, situated in the frontoparietal region.

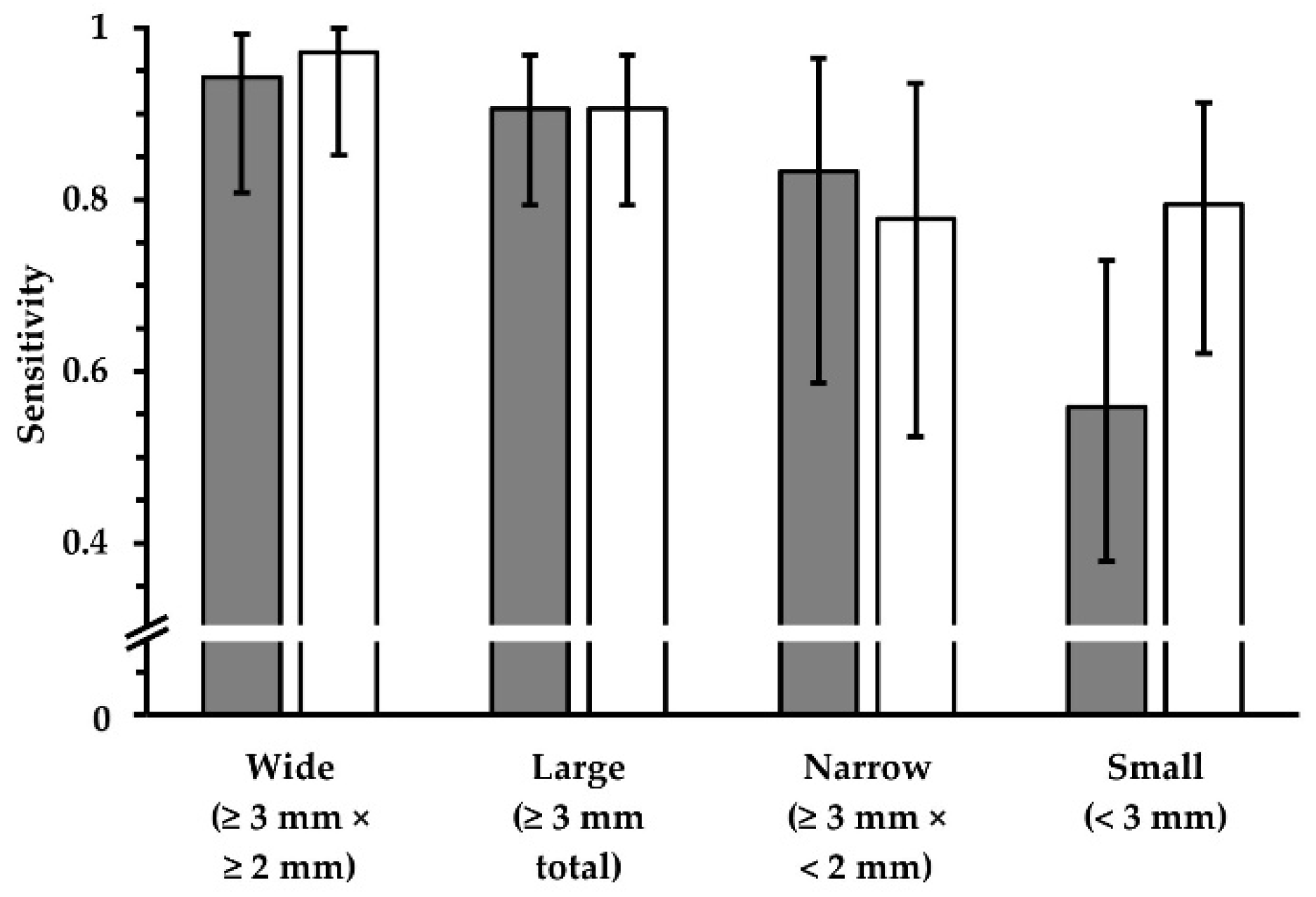

Figure 11.

Sensitivity in terms of lesion detection, using FLAIR

TSE images (white) and corresponding FLAIR

UF images (gray). Four groups, which represent different lesion diameters, are displayed, respectively. The additional error bars denote the 95% CIs. No significant differences in sensitivity could be detected for any of the lesion groups (p > 0.05). For small lesions, however, the data suggests a lower sensitivity using the FLAIR

UF images compared to the FLAIR

TSE images. Results imply that there is a correlation between lesion detectability and size in both cases, though.Note. Abbreviations as in

Table 7.

Figure 11.

Sensitivity in terms of lesion detection, using FLAIR

TSE images (white) and corresponding FLAIR

UF images (gray). Four groups, which represent different lesion diameters, are displayed, respectively. The additional error bars denote the 95% CIs. No significant differences in sensitivity could be detected for any of the lesion groups (p > 0.05). For small lesions, however, the data suggests a lower sensitivity using the FLAIR

UF images compared to the FLAIR

TSE images. Results imply that there is a correlation between lesion detectability and size in both cases, though.Note. Abbreviations as in

Table 7.

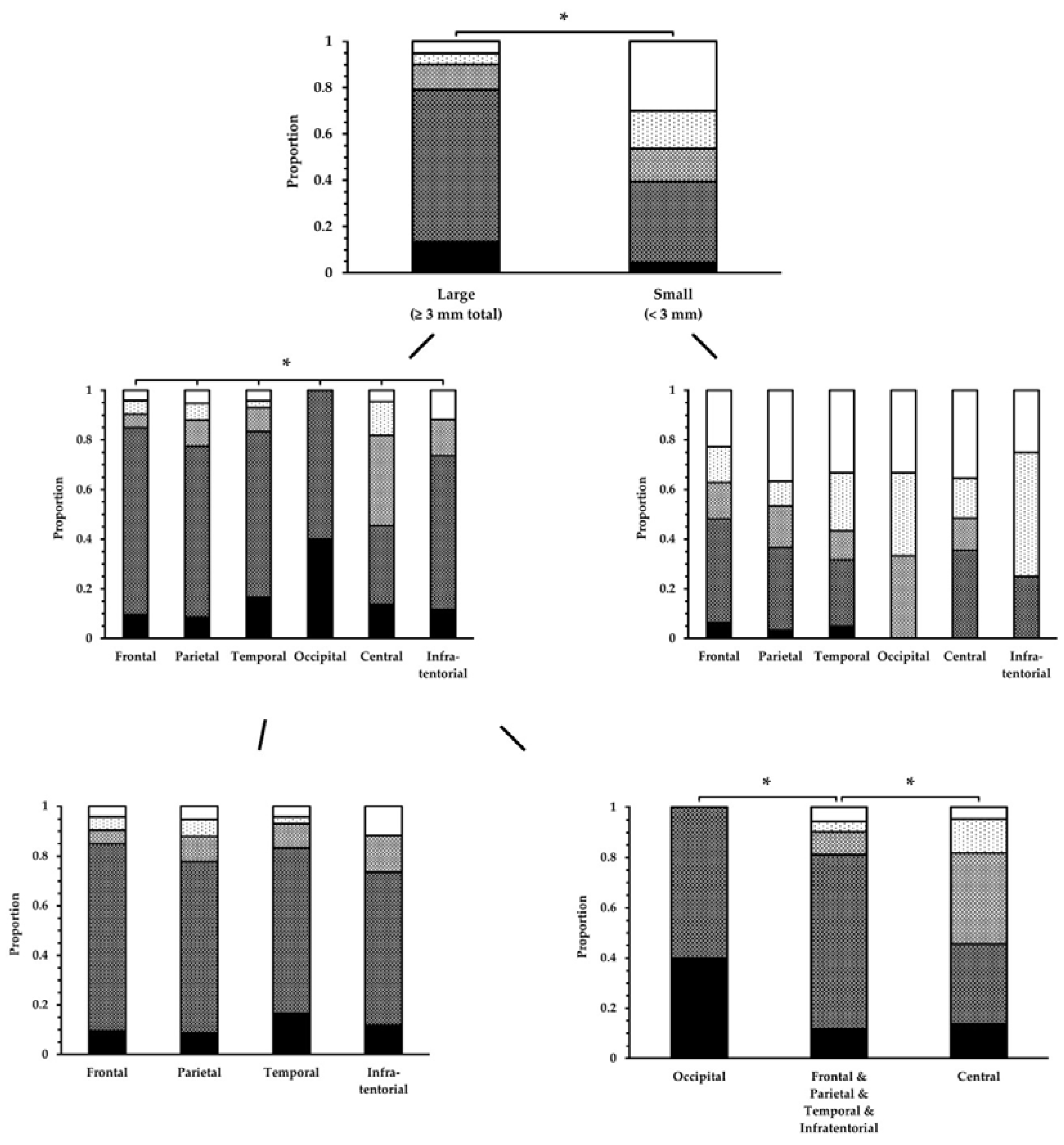

Figure 12.

Conspicuity ratings of lesions in the FLAIR

UF images, categorized by size and location. Lesion conspicuity was significantly superior for large lesions compared to small lesions. Unless for small lesions, there was a significant difference among some brain regions for large lesions. This could be attributed to occipital lesions (superior) and central lesions (inferior).Note. Black = 1; dark gray = 2; gray = 3; light gray = 4; white = 5. Abbreviations and brain regions as in

Table 11. * p < 0.05.

Figure 12.

Conspicuity ratings of lesions in the FLAIR

UF images, categorized by size and location. Lesion conspicuity was significantly superior for large lesions compared to small lesions. Unless for small lesions, there was a significant difference among some brain regions for large lesions. This could be attributed to occipital lesions (superior) and central lesions (inferior).Note. Black = 1; dark gray = 2; gray = 3; light gray = 4; white = 5. Abbreviations and brain regions as in

Table 11. * p < 0.05.

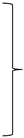

Figure 13.

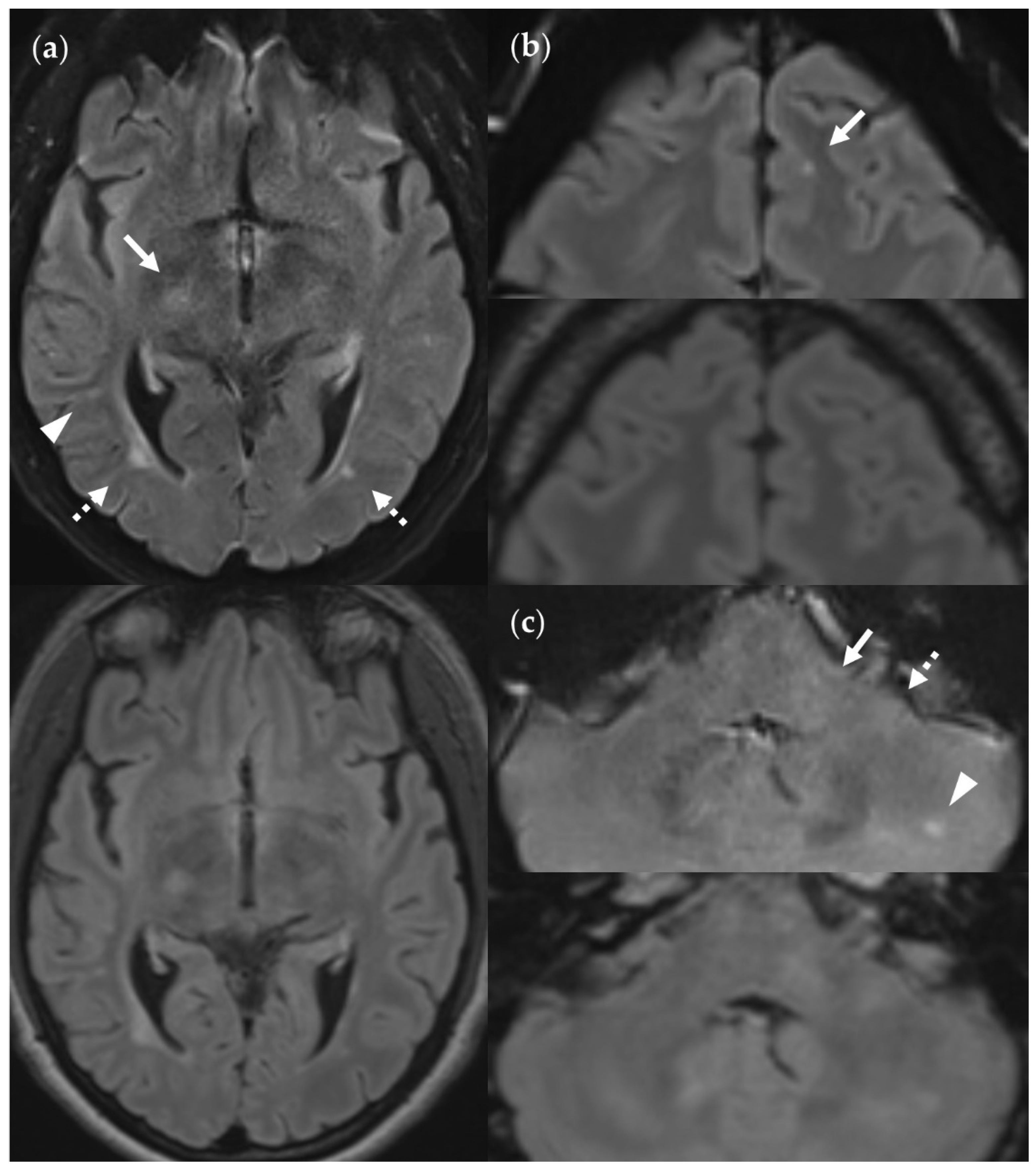

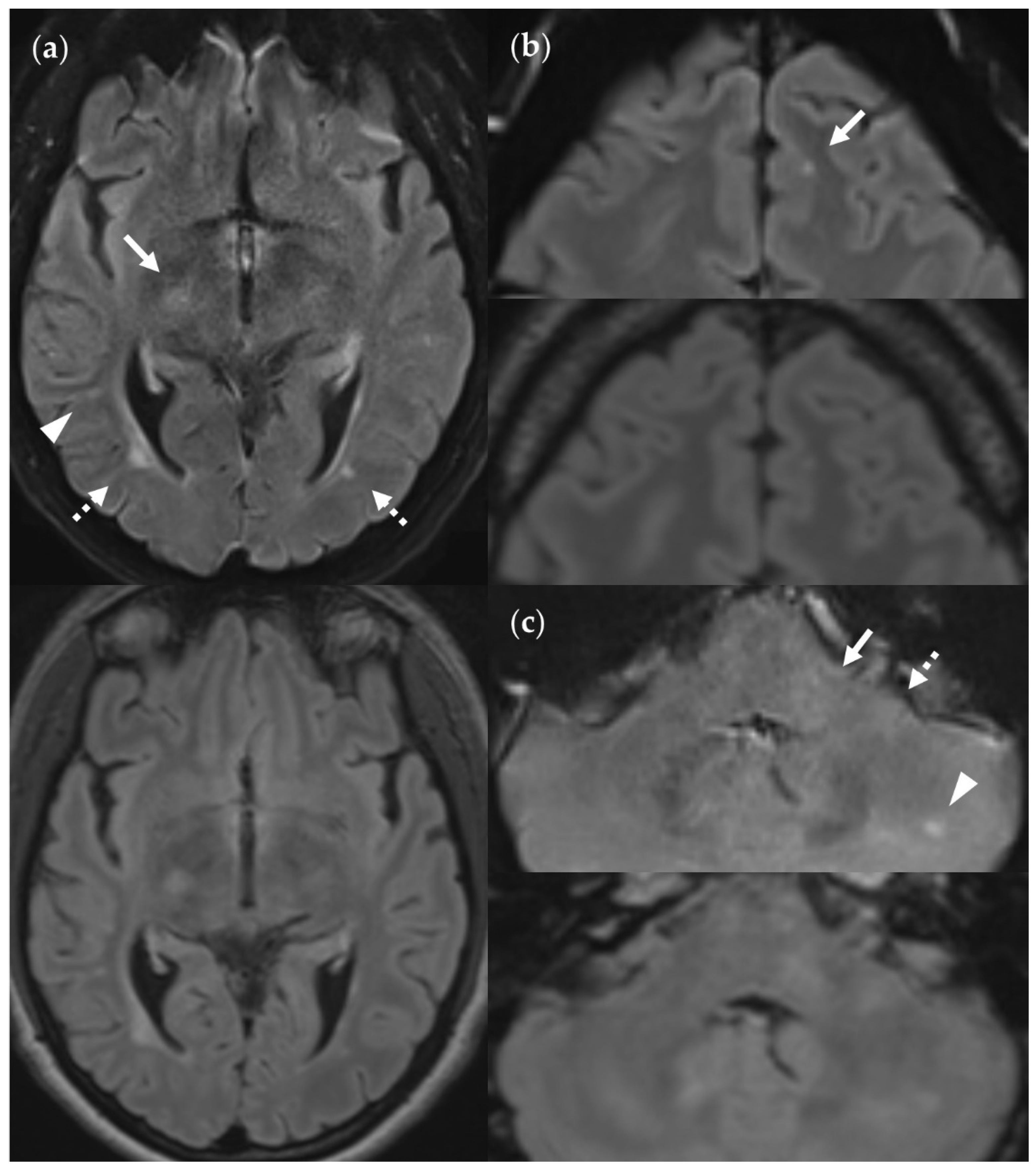

SNR and CNR in FLAIRUF images (top) and FLAIR3Da images (bottom). (a) Inflammatory lesions. Continuous arrow: Large lesion in the right mesencephalon (approx. 8 mm × 6 mm). The SNR appeared reduced in the center of the FLAIRUF image, thus decreasing the lesion conspicuity. Dotted arrows: Temporal lesions (right: approx. 5 mm × 4 mm; left: approx. 4mm × 3 mm). The SNR appeared significantly improved in posterior brain regions in the FLAIRUF images, thus equaling lesion conspicuity between the image variants. Note that in FLAIR3Da, the left lesion was better visible in the adjacent image slice (not depicted). Arrowhead: Partially imaged, right temporal lesion (approx. 3 mm × 1 mm in the slice image depicted). Comparison of adjacent slice images showed equal lesion conspicuity. (b) Arrow: Left frontal lesion (approx. 2 mm × 1 mm). Excellent lesion conspicuity in the FLAIRUF image due to very good SNR and CNR. (c) Infratentorial lesions. Continuous arrow: Large lesion (approx. 9 mm × 6 mm) that was not visible in the FLAIRUF image owing to low SNR and CNR. Dotted arrow: Large lesion (approx. 8 mm × 6 mm) that was less visible in the FLAIRUF image due to reduced SNR and CNR. Arrowhead: Large lesion (approx. 3 mm × 2 mm) that was better visible in the FLAIRUF image. Note that the SNR improves towards the outer regions of the FLAIRUF image.

Figure 13.

SNR and CNR in FLAIRUF images (top) and FLAIR3Da images (bottom). (a) Inflammatory lesions. Continuous arrow: Large lesion in the right mesencephalon (approx. 8 mm × 6 mm). The SNR appeared reduced in the center of the FLAIRUF image, thus decreasing the lesion conspicuity. Dotted arrows: Temporal lesions (right: approx. 5 mm × 4 mm; left: approx. 4mm × 3 mm). The SNR appeared significantly improved in posterior brain regions in the FLAIRUF images, thus equaling lesion conspicuity between the image variants. Note that in FLAIR3Da, the left lesion was better visible in the adjacent image slice (not depicted). Arrowhead: Partially imaged, right temporal lesion (approx. 3 mm × 1 mm in the slice image depicted). Comparison of adjacent slice images showed equal lesion conspicuity. (b) Arrow: Left frontal lesion (approx. 2 mm × 1 mm). Excellent lesion conspicuity in the FLAIRUF image due to very good SNR and CNR. (c) Infratentorial lesions. Continuous arrow: Large lesion (approx. 9 mm × 6 mm) that was not visible in the FLAIRUF image owing to low SNR and CNR. Dotted arrow: Large lesion (approx. 8 mm × 6 mm) that was less visible in the FLAIRUF image due to reduced SNR and CNR. Arrowhead: Large lesion (approx. 3 mm × 2 mm) that was better visible in the FLAIRUF image. Note that the SNR improves towards the outer regions of the FLAIRUF image.

Figure 14.

Spatial distortion artifacts in the FLAIRUF images. (a) Frontal distortion artifact limiting the diagnostic information in that region. (b) Frontobasal distortion artifacts resulting in limited diagnostic information from that region. (c) Temporopolar distortion artifacts limiting the diagnostic information in the vicinity. In contrast, the cerebellar and pontine distortion artifacts do not limit diagnostic information.

Figure 14.

Spatial distortion artifacts in the FLAIRUF images. (a) Frontal distortion artifact limiting the diagnostic information in that region. (b) Frontobasal distortion artifacts resulting in limited diagnostic information from that region. (c) Temporopolar distortion artifacts limiting the diagnostic information in the vicinity. In contrast, the cerebellar and pontine distortion artifacts do not limit diagnostic information.

Figure 15.

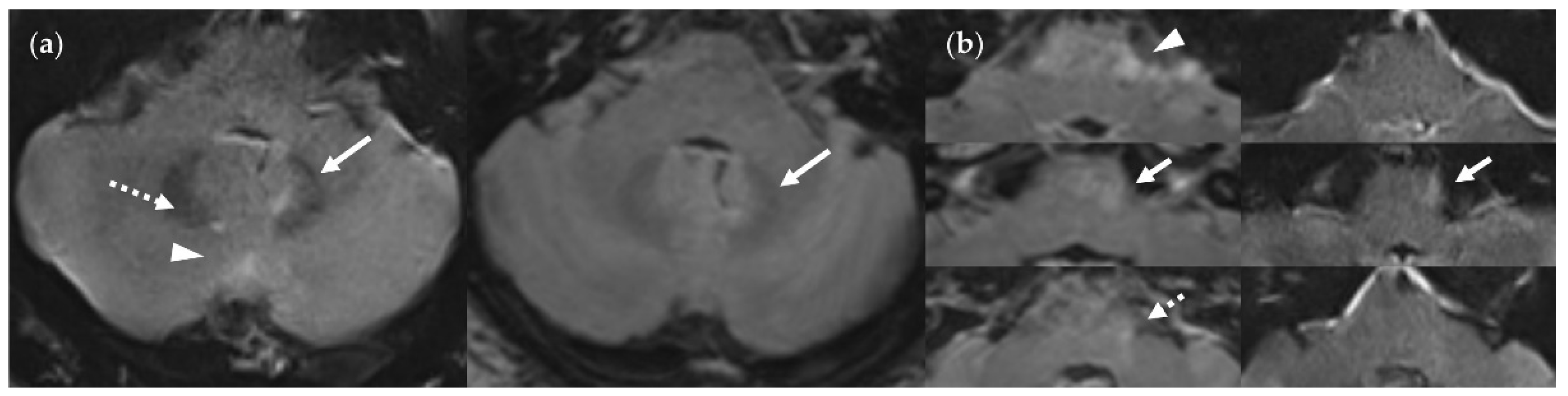

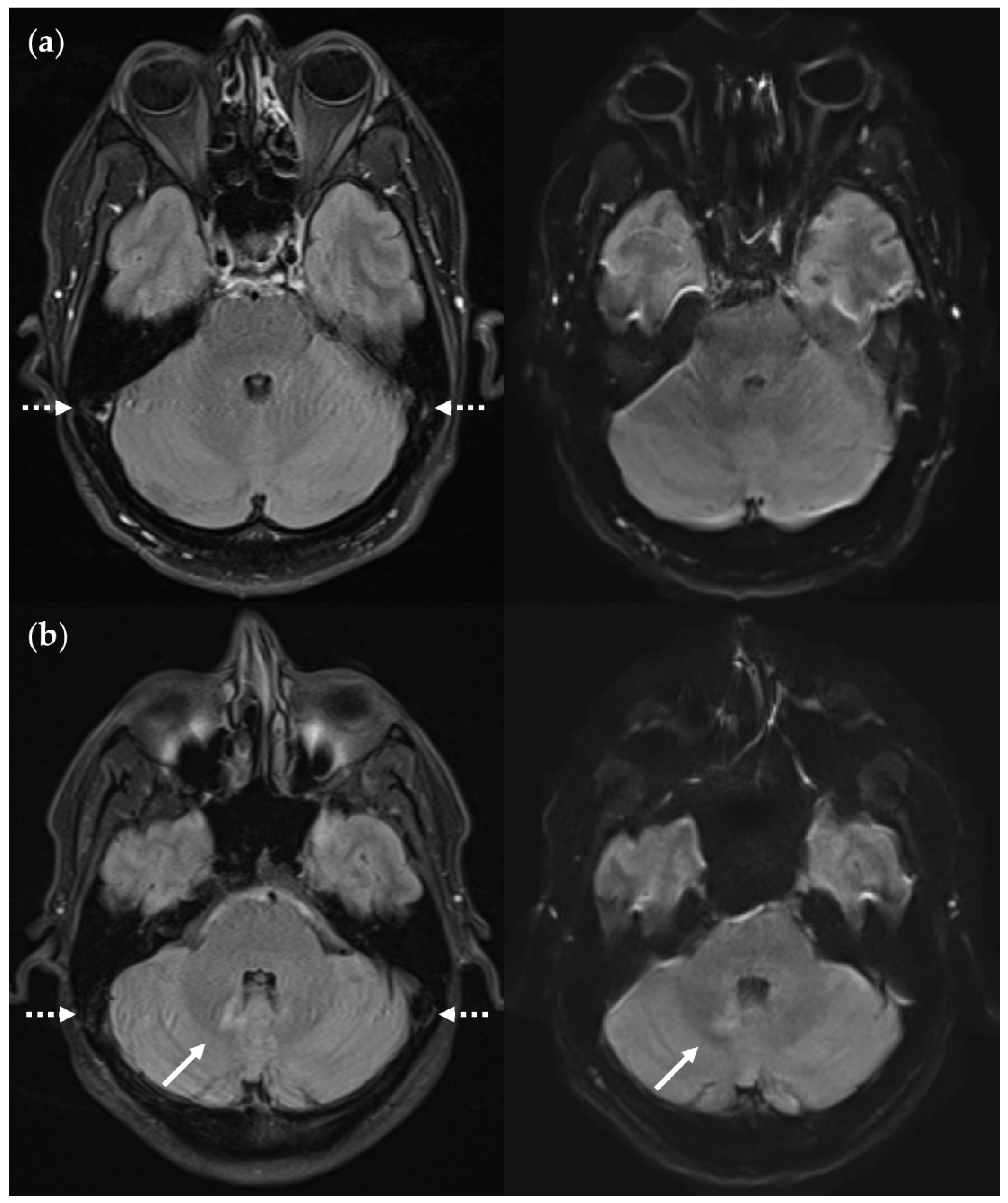

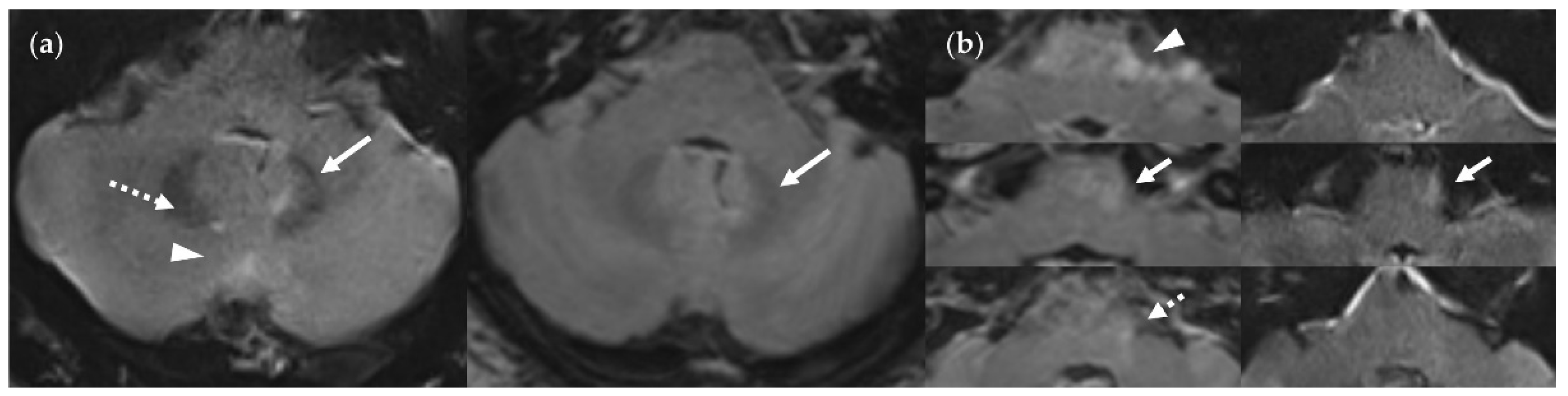

Infratentorial pulsatile flow artifacts that severely limit diagnostic information in the FLAIRUF images and the FLAIR3Da images. (a) FLAIRUF (left) and FLAIR3Da as a reference (right), cerebellum: The continuous arrows depict an inflammatory true positive lesion (approx. 4 mm × 3 mm). The dotted arrow indicates a pulsation artifact that is prone to being confused with a lesion. It was counted as a small, false positive lesion (approx. 2 mm × 1 mm). The arrowhead points to a pulsation artifact that is not likely to be confused with a lesion due to its typical location adjacent to the occipital sinus. (b) FLAIR3Da (left) and FLAIRUF as a reference (right), at the level of the pons: Top images: Typical hyperintense artifact band in the FLAIR3Da image; the arrowhead points to an intensely hyperintense spot within the artifact region that is part of the grainy texture of the artifact. Possible lesions within the artifact region would have been masked completely. Middle images: the continuous arrows show a large lesion (approx. 8 mm × 3 mm) that was misinterpreted as part of the pulsation artifact in the FLAIR3Da image. Bottom images: The dotted arrow denotes a small, false positive FLAIR3Da lesion (approx. 2 mm × 2 mm) that turned out to be part of the pulsation artifact.Note. Corresponding slices could not be positioned exactly identically owing to different slice thicknesses including slice gaps and non-parallel slice inclinations.

Figure 15.

Infratentorial pulsatile flow artifacts that severely limit diagnostic information in the FLAIRUF images and the FLAIR3Da images. (a) FLAIRUF (left) and FLAIR3Da as a reference (right), cerebellum: The continuous arrows depict an inflammatory true positive lesion (approx. 4 mm × 3 mm). The dotted arrow indicates a pulsation artifact that is prone to being confused with a lesion. It was counted as a small, false positive lesion (approx. 2 mm × 1 mm). The arrowhead points to a pulsation artifact that is not likely to be confused with a lesion due to its typical location adjacent to the occipital sinus. (b) FLAIR3Da (left) and FLAIRUF as a reference (right), at the level of the pons: Top images: Typical hyperintense artifact band in the FLAIR3Da image; the arrowhead points to an intensely hyperintense spot within the artifact region that is part of the grainy texture of the artifact. Possible lesions within the artifact region would have been masked completely. Middle images: the continuous arrows show a large lesion (approx. 8 mm × 3 mm) that was misinterpreted as part of the pulsation artifact in the FLAIR3Da image. Bottom images: The dotted arrow denotes a small, false positive FLAIR3Da lesion (approx. 2 mm × 2 mm) that turned out to be part of the pulsation artifact.Note. Corresponding slices could not be positioned exactly identically owing to different slice thicknesses including slice gaps and non-parallel slice inclinations.

Figure 16.

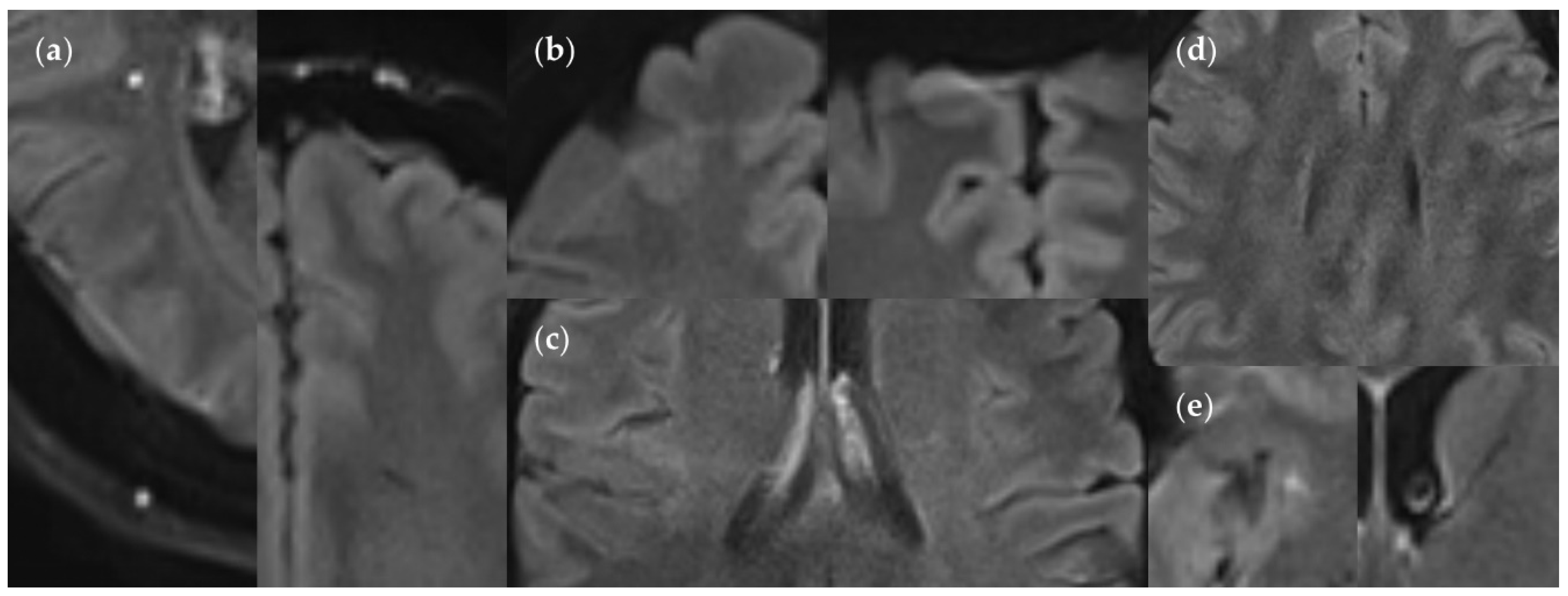

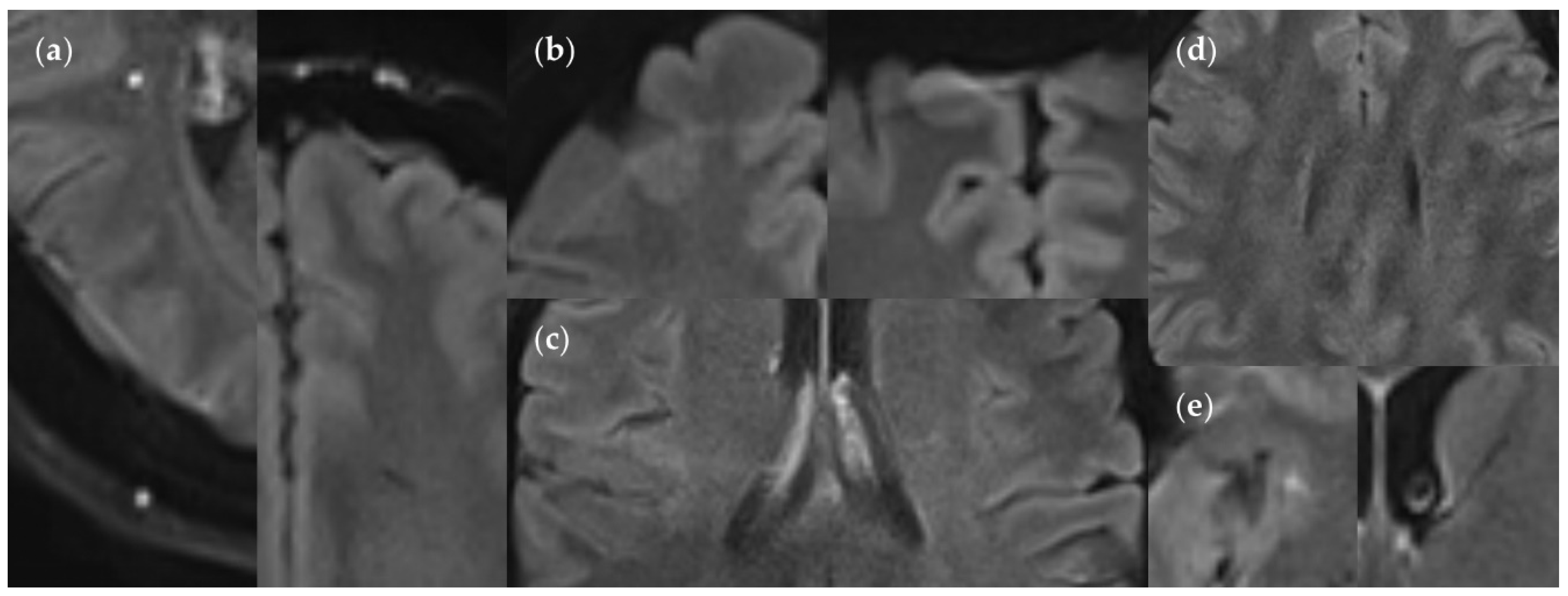

Minor artifacts in the FLAIRUF images. (a) Supratentorial pulsation artifacts, caused by extracerebral blood vessels: hyperintense (left image) or hypointense (right image). Hyperintense artifacts can usually be distinguished easily from a lesion, owing to its well-defined, sharply demarcated margin in relation to its size. Hyperintense and hypointense artifacts can usually be related to distant blood vessels, shifted along the phase encoding direction at fixed intervals corresponding to k-space sampling patterns (a quarter of the field of view for the protocol used in our study). Hyperintense artifacts are often located directly adjacent to hypointense artifacts in neighboring image slices. (b) Rare chemical shift artifacts due to incomplete fat suppression, in the shape of hyperintense (left image) or hypointense (right image) frontal streaks. (c) Rare residual aliasing, in the shape of a subtle hyperintense right central streak. (d) Rare spike artifacts, appearing in a herringbone pattern. (e) Supratentorial pulsation artifacts, caused by parenchymal blood vessels (singular findings): hyperintense (small FP lesion), insular cortex (left image) and hypointense, anterior limb of internal capsule (right image). They could not be distinguished using the FLAIR3D sequence, however, clearly correlated with contrast-enhanced images. Also, note the ventricular cerebrospinal fluid pulsation artifact in the right image.

Figure 16.

Minor artifacts in the FLAIRUF images. (a) Supratentorial pulsation artifacts, caused by extracerebral blood vessels: hyperintense (left image) or hypointense (right image). Hyperintense artifacts can usually be distinguished easily from a lesion, owing to its well-defined, sharply demarcated margin in relation to its size. Hyperintense and hypointense artifacts can usually be related to distant blood vessels, shifted along the phase encoding direction at fixed intervals corresponding to k-space sampling patterns (a quarter of the field of view for the protocol used in our study). Hyperintense artifacts are often located directly adjacent to hypointense artifacts in neighboring image slices. (b) Rare chemical shift artifacts due to incomplete fat suppression, in the shape of hyperintense (left image) or hypointense (right image) frontal streaks. (c) Rare residual aliasing, in the shape of a subtle hyperintense right central streak. (d) Rare spike artifacts, appearing in a herringbone pattern. (e) Supratentorial pulsation artifacts, caused by parenchymal blood vessels (singular findings): hyperintense (small FP lesion), insular cortex (left image) and hypointense, anterior limb of internal capsule (right image). They could not be distinguished using the FLAIR3D sequence, however, clearly correlated with contrast-enhanced images. Also, note the ventricular cerebrospinal fluid pulsation artifact in the right image.

Figure 17.

Infratentorial pulsatile flow artifacts in FLAIRTSE (left), contrasted with corresponding FLAIRUF slices (right). The artifact regions are marked with dotted arrows. They appear as irregular, streaky bands traversing the cerebellum from the right sigmoid sinus to the left sigmoid sinus. (a) Artifact-induced hyper- and hypointense dots across the cerebellum; the FLAIRUF image confirms that there is no actual lesion in this area. (b) Artifact-induced hyper- and hypointense streaks across the cerebellum; the FLAIRUF image confirms that there is one actual lesion (continuous arrow) in this area. Note. Corresponding slices could not be positioned exactly identically owing to different slice intervals and non-parallel slice inclinations.

Figure 17.

Infratentorial pulsatile flow artifacts in FLAIRTSE (left), contrasted with corresponding FLAIRUF slices (right). The artifact regions are marked with dotted arrows. They appear as irregular, streaky bands traversing the cerebellum from the right sigmoid sinus to the left sigmoid sinus. (a) Artifact-induced hyper- and hypointense dots across the cerebellum; the FLAIRUF image confirms that there is no actual lesion in this area. (b) Artifact-induced hyper- and hypointense streaks across the cerebellum; the FLAIRUF image confirms that there is one actual lesion (continuous arrow) in this area. Note. Corresponding slices could not be positioned exactly identically owing to different slice intervals and non-parallel slice inclinations.

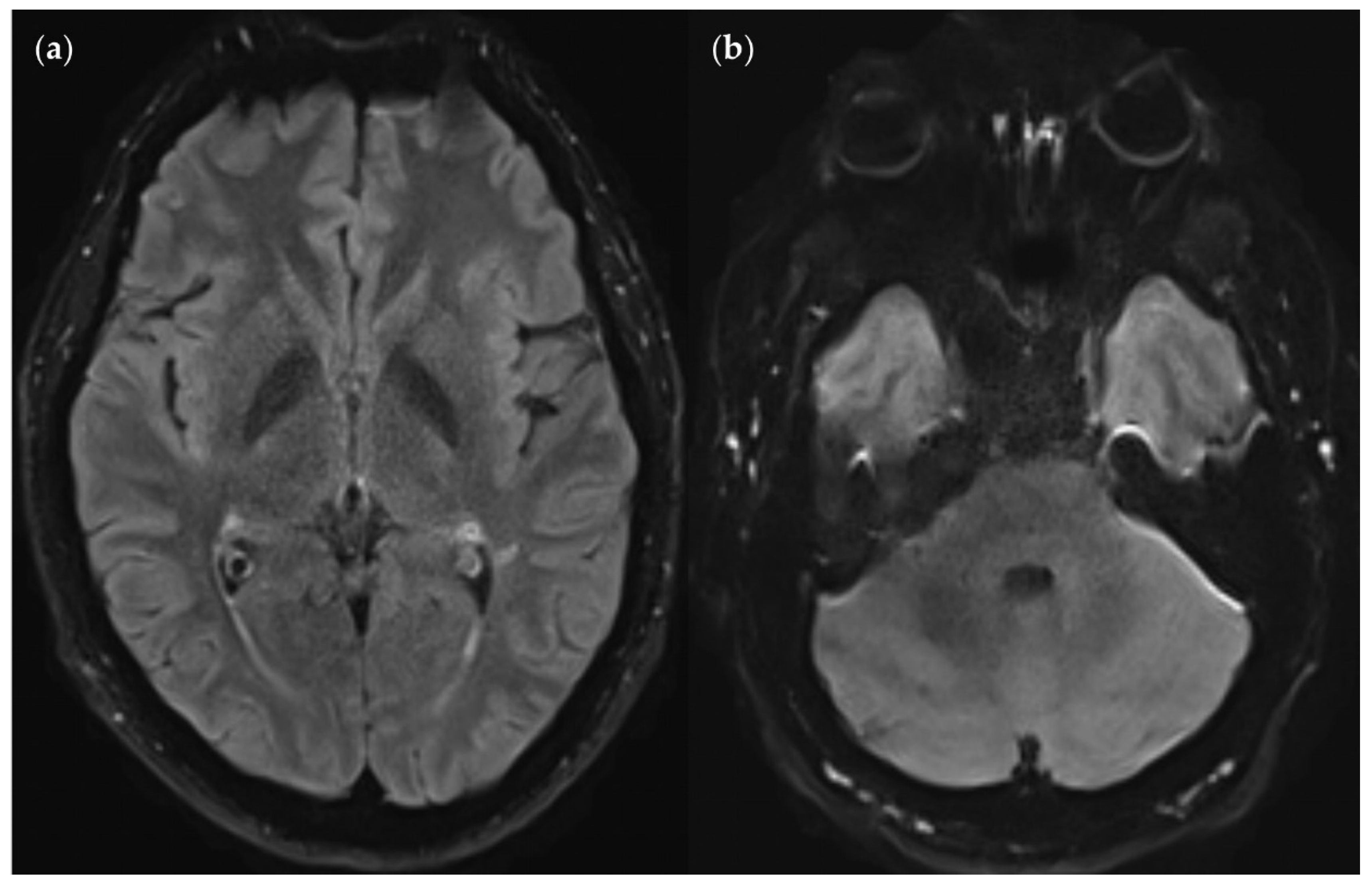

Figure 18.

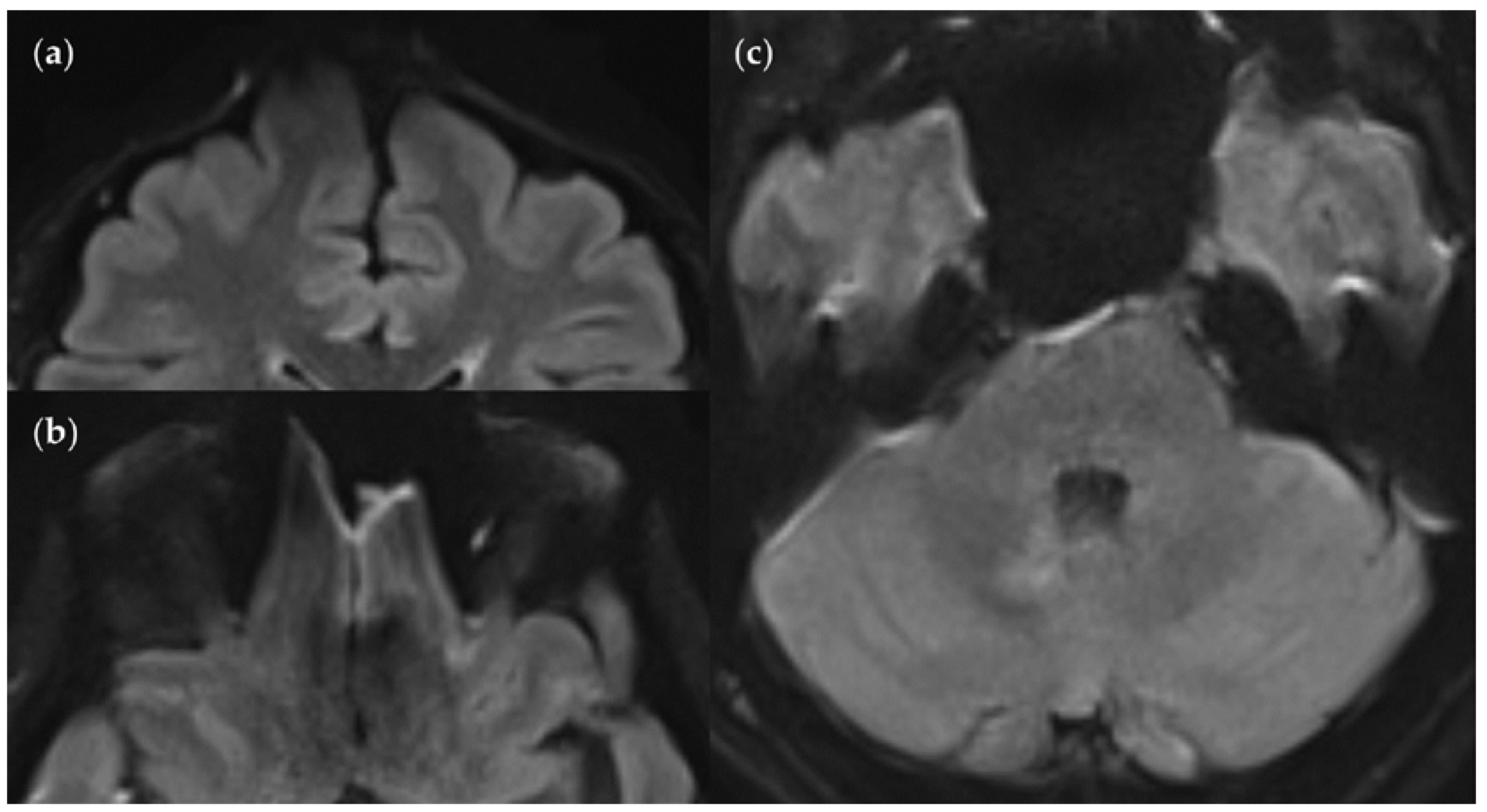

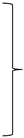

Positional dependence of SNR and CNR within the FLAIRUF images. (a) Image slice at the level of the basal nuclei. The SNR deteriorates towards the center of the image, whereas the CNR remains relatively good. Note that both the SNR and CNR are excellent in the marginal regions of the cerebral cortex, e.g., in the occipital lobe. (b) Image slice at the level of the pons and the cerebellum. The SNR is substandard around the pons and improves exceedingly towards the posterior lobe of the cerebellum to an excellent level. The CNR, however, seems generally slightly substandard in this area compared to other brain regions, even in the most posterior regions. This may be associated with the characteristic, fine folium-sulcus texture of the cerebellum (e.g., vermis or posterior lobe), which cannot be distinguished clearly.

Figure 18.

Positional dependence of SNR and CNR within the FLAIRUF images. (a) Image slice at the level of the basal nuclei. The SNR deteriorates towards the center of the image, whereas the CNR remains relatively good. Note that both the SNR and CNR are excellent in the marginal regions of the cerebral cortex, e.g., in the occipital lobe. (b) Image slice at the level of the pons and the cerebellum. The SNR is substandard around the pons and improves exceedingly towards the posterior lobe of the cerebellum to an excellent level. The CNR, however, seems generally slightly substandard in this area compared to other brain regions, even in the most posterior regions. This may be associated with the characteristic, fine folium-sulcus texture of the cerebellum (e.g., vermis or posterior lobe), which cannot be distinguished clearly.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristics |

Values |

| Number of patients |

17 |

| Mean age ± standard deviation |

33 ± 10 years |

| Median age (range) |

29 (21 – 60) years |

| Distribution between sexes |

71% male (n = 12), 29% female (n = 5) |

Table 2.

MRI acquisition parameters.

Table 2.

MRI acquisition parameters.

| Parameter |

FLAIRUF

|

FLAIRTSE

|

FLAIR3D

|

| Orientation |

Axial |

Axial |

- |

| Sequence type |

Multi-shot EPI |

TSE |

SPACE |

| TR (ms) |

8000 |

8800 |

5000 |

| TE (ms) |

88 |

87 |

386 |

| TI (ms) |

2372 |

2480 |

1800 |

| Flip angle (°) |

180 |

150 |

120 (VFA) |

| Voxel size (mm) |

0.9 × 0.9 × 4 |

0.7 × 0.7 × 4 |

0.5 × 0.5 × 0.9 1

|

| Gap between slices (mm) |

0.8 |

0 |

- |

| Phase encoding direction |

P → A |

R → L |

A → P |

| Acceleration mode |

DL-based |

GRAPPA |

GRAPPA |

| Acceleration factor |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| In-plane FOV (read × phase; mm) |

230 × 230 |

230 × 187 |

256 × 256 1

|

| Number of slices |

32 |

36 |

192 |

| Time of acquisition (min:s) |

0:51 |

2:22 |

4:57 |

Table 3.

Lesion detection in FLAIRUF images and FLAIR3Da images.

Table 3.

Lesion detection in FLAIRUF images and FLAIR3Da images.

| |

|

Total |

|

|

|

Sensitivity |

PPV |

| Lesion size |

S |

TP |

FN |

TPGS

|

FP |

|

95% CI [LL, UL] |

p |

95% CI [LL, UL] |

| |

|

n |

n |

n |

n |

|

% |

|

% |

Large

(≥ 3 mm) |

UF |

251 |

37 |

288 |

11 |

|

87.2 [82.7, 90.8] |

< 0.001 |

95.8 [92.6, 97.9] |

| 3Da |

274 |

14 |

11 |

|

95.1 [92.0, 97.3] |

96.1 [93.2, 98.1] |

Wide

(× ≥ 2 mm) |

UF |

160 |

11 |

171 |

6 |

|

93.6 [88.8, 96.7] |

0.50 |

96.4 [92.3, 98.7] |

| 3Da |

163 |

8 |

8 |

|

95.3 [91.0, 98.0] |

95.3 [91.0, 98.0] |

Narrow

(× < 2 mm) |

UF |

91 |

26 |

117 |

5 |

|

77.8 [69.2, 84.9] |

< 0.001 |

94.8 [88.3, 98.3] |

| 3Da |

111 |

6 |

3 |

|

94.9 [89.2, 98.1] |

97.4 [92.5, 99.5] |

Small

(< 3 mm) |

UF |

148 |

132 |

280 |

33 |

|

52.9 [46.8, 58.8] |

< 0.001 |

81.8 [75.4, 87.1] |

| 3Da |

268 |

12 |

15 |

|

95.7 [92.6, 97.8] |

94.7 [91.4, 97.0] |

Table 4.

Presumed causes of FN large lesions (≥ 3 mm total) in FLAIRUF and FLAIR3Da images.

Table 4.

Presumed causes of FN large lesions (≥ 3 mm total) in FLAIRUF and FLAIR3Da images.

| |

FLAIRUF

|

|

FLAIR3Da

|

| Presumed type of cause |

FNUFtotal

|

FNUF &

TP3Da

|

FNUF & FN3Da

|

FN3Da &

TPUF

|

FN3Da

total

|

| |

n |

n |

n |

|

n |

n |

n |

| Not detectable |

SR/CNR/SNR 2

|

28 |

22 |

6 |

|

0 |

1 |

1 |

| Mistaken for natural structure 1

|

7 |

4 |

3 |

|

3 |

0 |

3 |

| Mistaken for/masked by pulsation artifact |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

7 3

|

3 3

|

10 3 |

| Masked by distortion artifact |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Total |

37 |

27 |

10 |

4 |

14 |

Table 5.

Presumed causes of FN small lesions (< 3 mm) in FLAIRUF and FLAIR3Da images.

Table 5.

Presumed causes of FN small lesions (< 3 mm) in FLAIRUF and FLAIR3Da images.

| |

FLAIRUF

|

|

FLAIR3Da

|

| Presumed type of cause |

FNUFtotal

|

FNUF &

TP3Da

|

FNUF & FN3Da

|

FN3Da &

TPUF

|

FN3Da

total

|

| |

n |

n |

n |

|

n |

n |

n |

| Not detectable |

SR/CNR/SNR 2

|

110 |

105 |

5 |

|

0 |

3 |

3 |

| Mistaken for natural structure 1

|

21 |

19 |

2 |

|

3 |

1 |

4 |

| Mistaken for/masked by pulsation artifact |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

5 3

|

0 |

5 3 |

| Masked by distortion artifact |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Total |

132 |

124 |

8 |

4 |

12 |

Table 6.

Presumed causes of FP lesions in FLAIRUF and FLAIR3Da images.

Table 6.

Presumed causes of FP lesions in FLAIRUF and FLAIR3Da images.

| |

FLAIRUF

|

|

FLAIR3Da

|

| Presumed causal phenomenon |

FPUF

Large

(≥ 3 mm) |

FPUF

Small

(< 3 mm) |

FPUF

total

|

|

FP3Da

Large

(≥ 3 mm) |

FP3Da

Small

(< 3 mm) |

FP3Da

total

|

| |

N |

n |

n |

|

n |

n |

n |

| Partially imaged natural structure 1

|

SR 2

|

9 |

24 |

33 |

|

6 |

7 |

13 |

| Partially imaged nearby large lesion |

0 |

2 |

2 |

|

0 |

1 |

1 |

| Pulsation artifact |

2 3

|

7 3

|

9 3 |

|

5 4

|

7 5

|

12 5 |

| Total |

11 |

33 |

44 |

|

11 |

15 |

26 |

Table 7.

Lesion detectability in FLAIRTSE images and FLAIRUF counterparts.

Table 7.

Lesion detectability in FLAIRTSE images and FLAIRUF counterparts.

| |

|

Total |

|

|

Sensitivity |

|

| Lesion size |

S |

tseTP |

tseFN |

tseTPGS

|

|

95% CI [LL, UL] |

p |

| |

|

n |

n |

n |

|

% |

|

Large

(≥ 3 mm) |

UF |

48 |

5 |

53 |

|

90.6 [79.3, 96.9] |

0.68 |

| TSE |

48 |

5 |

|

90.6 [79.3, 96.9] |

Wide

(× ≥ 2 mm) |

UF |

33 |

2 |

35 |

|

94.3 [80.8, 99.3] |

> 0.99 |

| TSE |

34 |

1 |

|

97.1 [85.1, 99.9] |

Narrow

(× < 2 mm) |

UF |

15 |

3 |

18 |

|

83.3 [58.6, 96.4] |

> 0.99 |

| TSE |

14 |

4 |

|

77.8 [52.4, 93.6] |

Small

(< 3 mm) |

UF |

19 |

15 |

34 |

|

55.9 [37.9, 72.8] |

0.08 |

| TSE |

27 |

7 |

|

79.4 [62.1, 91.3] |

Table 8.

Presumed causes of FN large lesions (≥ 3 mm total) in FLAIRTSE and corresponding FLAIRTSE images.

Table 8.

Presumed causes of FN large lesions (≥ 3 mm total) in FLAIRTSE and corresponding FLAIRTSE images.

| |

FLAIRUF

|

|

FLAIRTSE

|

| Presumed type of cause |

tseFNUF

total

|

tseFNUF &

TPTSE

|

tseFNUF & FNTSE

|

FNTSE &

tseTPUF

|

FNTSE

total

|

| |

n |

n |

n |

|

n |

n |

n |

| Not detectable |

SR/CNR/SNR 2

|

3 |

3 |

0 |

|

0 |

3 |

3 |

| Mistaken for natural structure 1

|

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

2 |

0 |

2 |

| Total |

5 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

Table 9.

Presumed causes of FN small lesions (< 3 mm) in FLAIRTSE and corresponding FLAIRTSE images.

Table 9.

Presumed causes of FN small lesions (< 3 mm) in FLAIRTSE and corresponding FLAIRTSE images.

| |

FLAIRUF

|

|

FLAIRTSE

|

| Presumed type of cause |

tseFNUFtotal

|

tseFNUF &TPTSE

|

tseFNUF & FNTSE

|

FNTSE &tseTPUF

|

FNTSEtotal

|

| |

n |

n |

n |

|

n |

n |

n |

| Not detectable |

SR/CNR/SNR 2

|

13 |

10 |

3 |

|

3 |

3 |

6 |

| Mistaken for natural structure 1

|

2 |

2 |

0 |

|

0 |

1 |

1 |

| Total |

15 |

12 |

3 |

4 |

7 |

Table 10.

Presumed causes of FP lesions in FLAIRUF and FLAIR3Da images.

Table 10.

Presumed causes of FP lesions in FLAIRUF and FLAIR3Da images.

| |

FLAIRUF

|

|

FLAIRTSE

|

| Presumed causal phenomenon |

tseFPUFLarge(≥ 3 mm) |

tseFPUFSmall(< 3 mm) |

tseFPUFtotal

|

|

FPTSELarge(≥ 3 mm) |

FPTSESmall(< 3 mm) |

FPTSEtotal

|

| |

n |

n |

n |

|

n |

n |

n |

| Partially imaged natural structure 1

|

SR 2

|

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

1 |

3 |

4 |

| Partially imaged nearby large lesion |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

0 |

1 |

1 |

| Total |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

1 |

4 |

5 |

Table 11.

Conspicuity ratings of lesions in the FLAIRUF images, categorized by size and location.

Table 11.

Conspicuity ratings of lesions in the FLAIRUF images, categorized by size and location.

| |

|

Conspicuity |

|

|

| Size |

Location |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

TP3Da

|

p |

| |

|

n |

n |

n |

n |

n |

n |

|

Large

(≥ 3 mm total) |

All |

37 |

180 |

30 |

13 |

14 |

274 |

< 0.001 3

|

Small

(< 3 mm) |

All |

12 |

94 |

38 |

44 |

80 |

268 |

Large

(≥ 3 mm total) |

Frontal |

7 |

55 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

73 |

0.002 4

|

| Parietal |

5 |

40 |

6 |

4 |

3 |

58 |

| Temporal |

12 |

48 |

7 |

2 |

3 |

72 |

| Occipital |

6 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

| Central 1

|

3 |

7 |

8 |

3 |

1 |

22 |

| Infratentorial 2

|

4 |

21 |

5 |

0 |

4 |

34 |

Small

(< 3 mm) |

Frontal |

7 |

46 |

16 |

16 |

25 |

110 |

0.15 4

|

| Parietal |

2 |

20 |

10 |

6 |

22 |

60 |

| Temporal |

3 |

16 |

7 |

14 |

20 |

60 |

| Occipital |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

| Central 1

|

0 |

11 |

4 |

5 |

11 |

31 |

| Infratentorial 2

|

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

Large

(≥ 3 mm total) |

Frontal |

7 |

55 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

73 |

0.42 4

|

| Parietal |

5 |

40 |

6 |

4 |

3 |

58 |

| Temporal |

12 |

48 |

7 |

2 |

3 |

72 |

| Infratentorial 2

|

4 |

21 |

5 |

0 |

4 |

34 |

Small

(≥ 3 mm total) |

Occipital |

6 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.002 3

|

Frontal & Parietal &

Temporal & Infratentorial 2

|

28 |

164 |

22 |

10 |

13 |

237 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.01 3

|

| Central 1

|

3 |

7 |

8 |

3 |

1 |

22 |

|

Table 12.

Average lesion diameters (lengthwise), grouped by size category and location.

Table 12.

Average lesion diameters (lengthwise), grouped by size category and location.

| Location |

Large (≥ 3 mm total) |

|

Small (< 3 mm) |

| TP3Da

|

M & 95% CI

[LL, UL] |

SD |

Mdn |

p |

|

TP3Da

|

M & 95% CI

[LL, UL] |

SD |

Mdn |

p |

| n |

mm |

mm |

mm |

|

n |

mm |

mm |

mm |

| Frontal |

73 |

5.1 [4.6, 5.6] |

1.9 |

4.6 |

0.26 |

|

110 |

2.1 [2.0, 2.2] |

0.5 |

2.3 |

0.06 |

| Parietal |

58 |

5.8 [5.0, 6.7] |

3.2 |

4.6 |

|

60 |

2.1 [1.9, 2.2] |

0.6 |

2.1 |

| Temporal |

72 |

5.3 [4.7, 5.9] |

2.5 |

4.6 |

|

60 |

2.0 [1.8, 2.1] |

0.6 |

2.1 |

| Occipital |

15 |

5.6 [4.6, 6.6] |

1.8 |

5.4 |

|

3 |

2.8 [2.6, 2.9] |

0.1 |

2.8 |

| Central |

22 |

5.5 [3.8, 7.2] |

3.8 |

4.5 |

|

31 |

2.2 [2.1, 2.4] |

0.5 |

2.4 |

| Infratentorial |

34 |

6.5 [5.4, 7.5] |

3.0 |

5.2 |

|

4 |

2.3 [1.9, 2.8] |

0.3 |

2.4 |

| Total |

274 |

5.5 [5.2, 5.9] |

2.7 |

4.7 |

|

|

268 |

2.1 [2.0, 2.2] |

0.6 |

2.2 |

|

Table 13.

Conspicuity ratings of large lesions (≥ 3 mm), grouped by width category and location.

Table 13.

Conspicuity ratings of large lesions (≥ 3 mm), grouped by width category and location.

| Location |

Wide

(≥ 3 mm × ≥ 2 mm)

|

|

Narrow

(≥ 3 mm × < 2 mm)

|

|

Large

(≥ 3 mm total)

|

| Conspicuity |

Total |

|

Conspicuity |

Total |

|

TP3Da |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

| n |

n |

n |

n |

n |

n |

|

n |

N |

n |

n |

n |

n |

|

n |

| Frontal |

7 |

35 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

43 |

|

0 |

20 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

30 |

|

73 |

| Parietal |

2 |

28 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

33 |

|

3 |

12 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

25 |

|

58 |

| Temporal |

5 |

30 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

40 |

|

7 |

18 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

32 |

|

72 |

| Occipital |

4 |

8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

|

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

15 |

| Central |

0 |

4 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

10 |

|

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

12 |

|

22 |

| Infratentorial |

3 |

17 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

25 |

|

1 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

9 |

|

34 |

| Total |

21 |

122 |

14 |

3 |