Submitted:

19 June 2024

Posted:

21 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

“I am worried about my superiors who, however, do not have the appropriate knowledge to deal with a problem that arises and while they should admit it, they give instructions to their subordinates, who are not sure that it is the right action that they are indicating to be performed”.

“As someone who generally struggles in labs, I would like more internships before going into the clinics (e.g. if the dental school had one more year of internships before going into the clinics, I think it would be much better)”

“The anxiety that next year we will enter the clinics and in some laboratories, half of the units may not work, as a result of which there is no proper simulation of a real clinical case. I'm getting anxious at the thought that next year I'll be dealing with a real patient that a mistake of mine could cost him dearly. It also worries me that if, for example, you are sick, it is very difficult to replace a laboratory. Also, if you miss a workshop, it means you are left behind in the next one. And obviously, the amount of reading is huge.”

“After my clinical practice, when I leave the hospital, without the clinic staff seeing me, I leave in tears. The conditions are very bad, I get tired both physically and psychologically, I can't study and I'm worried that I won't be able to get the material in the lessons.”

“Nurses experience extra stress in Greece because most people don't appreciate them. I know this is very hard to change. However, I saw that almost all the excellent nursing students continued their studies in another subject. None remained in the infirmary. There are these stereotypes in Greece that anyone who is a nurse is just someone who isn't good enough to be a doctor. If this doesn't stop most nurses will never feel fulfilled by their profession.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of Somatization Symptoms among Dental and Nursing Students

4.2. Difference of Perceived Stress Levels between Dental and Nursing Students

4.3. Somatic Manifestations of Stress

4.4. Demographic Factors Influencing the Experience of Stress-Induced Somatic Symptoms

4.5. Resilience Factors for Dentistry and Nursing Students

4.6. Variation of Coping Strategies in Response to Stress-Induced Somatic Symptoms

4.7. Perceptions of Dental and Nursing Students Regarding the Effectiveness of Existing Support Mechanisms in Addressing Somatization Symptoms

4.8. Importance of a Coach in Controlling the Phenomena

4.9. Developing Targeted Interventions and Support Mechanisms to Promote the Well-Being of Dental and Nursing Students

4.10. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Li, Z.-S.; Hasson, F. Resilience, stress, and psychological well-being in nursing students: a systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 90, 104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolana, A.; Loster, Z.; Loster, J. Assessment of stress burden among dental students: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of data. Dent Med Probl. 2022, 59, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocny-Pachońska, K.; Doniec, R.; Trzcionka, A.; Pachoński, M.; Piaseczna, N.; Sieciński, S.; Osadcha, O.; Łanowy, P.; Tanasiewicz, M. Evaluating the stress-response of dental students to the dental school environment. Peer J. 2020, 6, e8981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhila, J.G. , Sheelongo, F. An Exploration of Second-Year Student Nurse's Perceptions of Stress Towards Substandard Academic Performance at University, Windhoek, Khomas Region, Namibia. Int Internal Med J. 2023, 1, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Basudan, S.; Binanzan, N.; Alhassan, A. Depression, anxiety and stress in dental students. Int J Med Educ. 2017, 24, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.S.; Rong, J.R.; Huang, M.Z. Factors associated with perceived stress of clinical practice among associate degree nursing students in Taiwan. BMC Nurs. 2021, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta-Vergara, K.; Fortich-Mesa, N.; Tirado-Amador, L.; Simancas-Pallares, M. Common mental disorders and associated factors in dental students from Cartagena, Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría (English ed.), 2019, 48, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova Olivera, P.; Gasser Gordillo, P.; Naranjo Mejía, H.; La Fuente Taborga, I.; Grajeda Chacón, A.; Sanjinés Unzueta, A. Academic stress as a predictor of mental health in university students. Cogent Education, 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feussner, O.; Rehnisch, C.; Rabkow, N.; Watzke, S. Somatization symptoms-prevalence and risk, stress and resilience factors among medical and dental students at a mid-sized German university. Peer J. 2022, 19, e13803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, E.L.; Hulett, J.M.; Sherwin, L.B.; Thompson, S.; Bettencourt, B.A. Prevalence, characteristics and measurement of somatic symptoms related to mental health in medical students: a scoping review. Annals of Medicine 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara-Souza, M.B.; Carvalho, A.G.; Figueredo, O.M.C.; Bracci, A.; Manfredini, D.; Rodrigues Garcia, R.C.M. Awake Bruxism frequency and psychosocial factors in college preparatory students. Cranio 2020, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levartovsky, S.; Msarwa, S.; Reiter, S.; Eli, I.; Winocur, E.; Sarig, R. The Association between Emotional Stress, Sleep, and Awake Bruxism among Dental Students: A Sex Comparison. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, H.; Kanemura, K.; Tanabe, N.; Takebe, J. Clenching occurring during the day is influenced by psychological factors. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2011, 55, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winocur, E.; Uziel, N.; Lisha, T.; Goldsmith, C.; Eli, I. Self-reported bruxism associations with perceived stress, motivation for control, dental anxiety and gagging. J. Oral Rehabil. 2011, 38, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, D.; Winocur, E.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Paesani, D.; Lobbezoo, F. Epidemiology of bruxism in adults: A systematic review of the literature. J. Orofac. Pain 2013, 27, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smardz, J.; Martynowicz, H.; Wojakowska, A.; Michalek-Zrabkowska, M.; Mazur, G.; Wieckiewicz, M. Correlation between sleep bruxism, stress, and depression-a polysomnographic study. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elani, H.W.; Allison, P.J.; Kumar, R.A.; Mancini, L.; Lambrou, A.; Bedos, C. A systematic review of stress in dental students. J. Dent. Educ. 2014, 7, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahem, A.M.; van der Molen, H.T.; Alaujan, A.H.; Schmidt, H.G.; Zamakhshary, M.H. Stress amongst dental students: A systematic review. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2011, 15, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahem, A.M.; Van der Molen, H.T.; Alaujan, A.H.; De Boer, B.J. Stress management in dental students: A systematic review. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2014, 5, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, D.P. , Realo, A., Voracek, M., Allik, J. (2008). Why can’t a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big Five personality traits across 55 cultures. J Personality Social Psychol, 2008, 94, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, D.F. (2012). Sex Differences in Cognitive Abilities (4th ed.). Psychology Press.

- Dedovic, K.; Wadiwalla, M.; Engert, V.; Pruessner, J.C. The role of sex and gender socialization in stress reactivity. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liutsko, L.; Muiños, R.; Tous Ral, J.M.; Contreras, M.J. Fine motor precision tasks: Sex differences in performance with and without visual guidance across different age groups. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, B.; Sarak, G.; Oral, K. Oral health-related quality of life and psychological states of dental students with temporomandibular disorders. J Dent Educ. 2022, 86, 1459–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, C.L.; Li, L.H.; Chen, Z.Q.; Liu, Y.; Lu, L. Association between stress and mental health among nursing students: A cross-sectional study. J Advanced Nursing, 2023, 79, 671–681. [Google Scholar]

- Hamaideh, S.H. Stress and coping strategies among nursing students during clinical training: A descriptive study. J Nursing Educ Practice, 2022, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hamaideh, S.H.; Abuhammad, S. Khait, A.A.; Al-Modallal, H.; Hamdan-Mansour, A.M.; Masa'deh, R.; Alrjoub, S. Levels and predictors of empathy, self-awareness, and perceived stress among nursing students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 20, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulu, B.M.; du Plessis, E.; Koen, M.P. Experiences of nursing students regarding clinical placement and support in primary healthcare clinics: Strengthening resilience. Health SA. 2021 Oct 29;26:1615. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.; Samanta, P.; Panigrahi, A.; Dash, K.; Behera, M.R.; Das, R. Mental Health Status, Coping Strategies During Covid-19 Pandemic Among Undergraduate Students of Healthcare Profession. Int J Ment Health Addict 202, 21, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumba, M.N.; Horton, A.G.; Cole, H.; Dickson, B.; Brown, W.; Parker, K.; Tice, J.; Key, B.; Castillo, R.; Compton, J.; Cooney, A.; Devers, S.; Shoemaker, I.; Bartlett, R. Development and implementation of a novel peer mentoring program for undergraduate nursing students. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2023, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.; Kim, J. Factors affecting academic burnout of nursing students according to clinical practice experience. BMC Med Educ 2022, 22, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, Y.; Akdemir, M.; Meydanlioglu, A.; Aktekin, M.R. Psychological Distress, Depression, and Anxiety in Nursing Students: A Longitudinal Study. Healthcare (Basel). 2023, 21, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J. Umbrella Review: Stress Levels, Sources of Stress, and Coping Mechanisms among Student Nurses. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuente, G.A. Relation between Burnout and Sleep Problems in Nurses: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Healthcare (Basel). 2022, 21, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, D.F. Sex Differences in Cognitive Abilities, 4th ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liutsko, L.; Muiños, R.; Tous-Ral, J.M. Age-related differences in proprioceptive and visuo-proprioceptive function in relation to fine motor behaviour. Eur. J. Ageing 2014, 11, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, D.P.; Realo, A.; Voracek, M.; Allik, J. Why can’t a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big Five personality traits across 55 cultures. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 94, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkonen, K.; Elo, S.; Tuomikoski, A.M.; Kääriäinen, M. Mentor experiences of international healthcare students' learning in a clinical environment: A systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2016, 40, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Xin Min, L.; Chan, C.J.W.; Dong, Y.; Mikkonen, K.; Zhou, W. Peer mentoring programs for nursing students: A mixed methods systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2022, 119, 105577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mínguez Moreno, I.; González de la Cuesta, D.; Barrado Narvión, M.J.; Arnaldos Esteban, M.; González Cantalejo, M. Nurse Mentoring: A Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2023, 15, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Mangoulia, P.; Myrianthefs, P. Quality of Life and Wellbeing Parameters of Academic Dental and Nursing Personnel vs. Quality of Services. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonelli-Muñoz, A.J.; Balanza, S.; Rivera-Caravaca, J.M.; Vera-Catalán, T.; Lorente, A.M.; Gallego-Gómez, J.I. Reliability and validity of the student stress inventory-stress manifestations questionnaire and its association with personal and academic factors in university students. Nurse Educ Today. 2018, 64, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, D. , Mallery, P. IBM SPSS Statistics 25 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference (15th ed.). New York: Routledge, 2019.

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics Ed. 5. SAGE Publications, 2017.

- Behere, S.P.; Yadav, R.; Behere, P.B. A comparative study of stress among students of medicine, engineering, and nursing. Indian J Psychol Med. 2011, 33, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.N.; Chiu, H.-Y.; Chuang, Y.-H.; Huang, H.-C. Prevalence of stress and anxiety among nursing students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.; Fethney, J.; Kozlowski, D.; Fois, R.; Reza, F.; McCloughen, A. Emotional intelligence and perceived stress of Australian pre-registration healthcare students: A multi-disciplinary cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2018, 66, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersan, N.; Dölekoğlu, S.; Fişekçioğlu, E.; İlgüy, M.; Oktay, İ. Perceived sources and levels of stress, general self-efficacy and coping strategies in preclinical dental students. Psychol Health Med. 2018, 23, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myint, K.; See-Ziau, H.; Husain, R.; Ismail, R. Dental Students' Educational Environment and Perceived Stress: The University of Malaya Experience. Malays J Med Sci. 2016, 23, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Veeraboina, N.; Doshi, D.; Kulkarni, S.; Patanapu, S.K.; Danatala, S.N.; Srilatha, A. Perceived stress and coping strategies among undergraduate dental students - an institutional-based study. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2020, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onieva- Zafra, M.D.; Fernández-Muñoz, J.J.; Fernández-Martínez, E.; García-Sánchez, F.J.; Abreu-Sánchez, A.; Parra-Fernández, M.L. Anxiety, perceived stress and coping strategies in nursing students: a cross-sectional, correlational, descriptive study. BMC Med Educ. 2020, 19, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glise K, Ahlborg G Jr, Jonsdottir IH. Prevalence and course of somatic symptoms in patients with stress-related exhaustion: does sex or age matter. BMC Psychiatry. 2014, 23, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandha, R. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of headache in dental students of a tertiary care teaching dental hospital in Northern India. Inter J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.J.; Lin, M.; Wong, Y.T.; Yan, L.; Zhang, D.; Gao, Y. Migraine Attacks and Relevant Trigger Factors in Undergraduate Nursing Students in Hong Kong: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Pain Res. 2022, 10, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi A, Kumar Behera B, Nath Sarma N. Prevalence, pattern, and associated psychosocial factors of headache among undergraduate students of health profession. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 2020, 8, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashatah, A.S.; Syed, W.; Al-Rawi, M.B.A.; Al Arifi, M.N. Assessment of Headache Characteristics, Impact, and Managing Techniques among Pharmacy and Nursing Undergraduates—An Observational Study. Medicina 2023, 59, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamulevicius, N.; Save, R.; Gandhi, N.; Lubiak, S.; Sharma, S.; Aguado Loi, C.X.; Paneru, K.; Martinasek, M.P. Perceived Stress and Impact on Role Functioning in University Students with Migraine-Like Headaches during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero-Chillerón, M.J.; González-Chordá, V.M.; López-Peña, N.; Cervera-Gasch, Á.; Suárez-Alcázar, M.P.; Mena-Tudela, D. Burnout syndrome in nursing students: An observational study. Nurse Educ Today. 2019, 76, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, R.; Balhara, Y.P.; Gupta, C.S. Gender differences in stress response: Role of developmental and biological determinants. Ind Psychiatry J. 2011, 20, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Hong, K.; Bergquist, K.; Sinha, R. Gender differences in response to emotional stress: an assessment across subjective, behavioral, and physiological domains and relations to alcohol craving. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008, 32, 1242–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, S.B.; Sliwinski, M.J.; Blanchard-Fields, F. Age differences in emotional responses to daily stress: the role of timing, severity, and global perceived stress. Psychol Aging. 2013, 28, 1076–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birditt, K.S.; Turkelson, A.; Fingerman, K.L.; Polenick, C.A.; Oya, A. Age Differences in Stress, Life Changes, and Social Ties During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for Psychological Well-Being. Gerontologist. 2021, 23, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owczarek, J.E.; Lion, K.M.; Radwan-Oczko, M. Manifestation of stress and anxiety in the stomatognathic system of undergraduate dentistry students. J Int Med Res. 2020, 48, 300060519889487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahem, A.M.; Van der Molen, H.T.; De Boer, B.J. Effect of year of study on stress levels in male undergraduate dental students. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2013, 18, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocny-Pachońska, K.; Doniec, R.; Trzcionka, A.; Pachoński, M.; Piaseczna, N.; Sieciński, S.; Osadcha, O.; Łanowy, P.; Tanasiewicz, M. Evaluating the stress-response of dental students to the dental school environment. Peer J. 2020, 6, e8981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, E.L.; Hulett, J.M.; Sherwin, L.B.; Thompson, S.; Bettencourt, B.A. Prevalence, characteristics and measurement of somatic symptoms related to mental health in medical students: a scoping review. Ann Med. 2023, 55, 2242781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Ahn, S. Self-Reflection, Emotional Self Disclosure, and Posttraumatic Growth in Nursing Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in South Korea. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodeify, R.; Moghaddam Tabrizi, F. Nursing Students' Perceptions of Effective Factors on Mental Health: A Qualitative Content Analysis. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2020, 8, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, S.P.; Sundus, A.; Younas, A.; Fakhar, J.; Inayat, S. Development and Testing of a Measure of Self-awareness Among Nurses. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2021, 43, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karahan, M.; Kiziltan Eliacik, B.B.; Baydili, K.N. The interplay of spiritual health, resilience, and happiness: an evaluation among a group of dental students at a state university in Turkey. BMC Oral Health. 2024, 21, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafati, F.; Nouhi, E.; Sabzevari, S.; Dehghan-Nayeri, N. Coping strategies of nursing students for dealing with stress in clinical setting: A qualitative study. Electron Physician. 2017, 25, 6120–6128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Latif, R.; Mat Nor, M.Z. Stressors and Coping Strategies during Clinical Practice among Diploma Nursing Students. Malays J Med Sci. 2019, 26, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behan, C. The benefits of meditation and mindfulness practices during times of crisis such as COVID-19. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020, 37(4), 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocchiara, R.A.; Peruzzo, M.; Mannocci, A.; Ottolenghi, L.; Villari, P.; Polimeni, A.; Guerra, F.; La Torre, G. The Use of Yoga to Manage Stress and Burnout in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2019, 26, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.B.; Nezlek, J.B.; Thrash, T.M. The dynamics of prayer in daily life and implications for well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2023, 124, 1299–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalska-Wasyl, M.M.; Zarzycka, B. Internal Dialogue as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Prayer and Well-Being. J Relig Health. 2020, 59, 2045–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxon, L.; Makhashvili, N.; Chikovani, I.; Seguin, M.; McKee, M.; Patel, V.; Bisson, J.; Roberts, B. Coping strategies and mental health outcomes of conflict-affected persons in the Republic of Georgia. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2017, 2017. 26, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanvermez, Y.; Zhao, R.; Cuijpers, P.; de Wit, L.M.; Ebert, D.D.; Kessler, R.C.; Bruffaerts, R.; Karyotaki, E. Effects of self-guided stress management interventions in college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Internet Interv. 2022, 12, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnesen, C.T.; Jensen, M.P.; Madsen, K.R.; Toftager, M.; Rosing, J.A.; Krølner, R.F. Implementation of initiatives to prevent student stress: process evaluation findings from the Healthy High School study. Health Educ Res. 2020, 1, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguin, M.; Roberts, B. Coping strategies among conflict-affected adults in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic literature review. Global Public Health. 2017, 12, 811–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, W. The Role of Academic Resilience, Motivational Intensity and Their Relationship in EFL Learners' Academic Achievement. Front Psychol. 2022, 26, 12:823537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004, 86, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo clinic. Exercise and stress: Get moving to manage stress. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/exercise-and-stress/art-20044469#:~:text=Exercise%20increases%20your%20overall%20health,%2Dgood%20neurotransmitters%2C%20called%20endorphins. (accessed 15 June 2024).

- Childs, E.; de Wit, H. Regular exercise is associated with emotional resilience to acute stress in healthy adults. Front Physiol. 2014, 1, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nweke, G.E.; Jarrar, Y.; Horoub, I. Academic stress and cyberloafing among university students: the mediating role of fatigue and self-control. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 2024, 11, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, Y.C.; Yip, K.H.; Tsui, W.K. Exploring the Gender-Related Perceptions of Male Nursing Students in Clinical Placement in the Asian Context: A Qualitative Study. Nurs Rep. 2021, 1, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosen, M. Nursing students' perception of gender-defined roles in nursing: a qualitative descriptive study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 4, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegel, B.; Dunbar, S.; Fitzsimons, D.; Freedlande, K.; Leef, C.; Middletong, S.; Stromberg, A.; Vellonei, E.; Webber, D.; Jaarsma, T. Self-care research: Where are we now? Where are we going? Inter J Nursing Studies 2021, 16, 103402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.S.; Alaa, A.; Riboli Sasco, E.; Bagkeris, E.; El-Osta, A. How has COVID-19 changed healthcare professionals' attitudes to self-care? A mixed methods research study. PLoS One. 2023, 24, e0289067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunzler, A.M.; Helmreich, I.; König, J.; Chmitorz, A.; Wessa, M.; Binder, H.; Lieb, K. Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare students. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020, 20, CD013684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March-Amengual, J.M.; Cambra Badii, I.; Casas-Baroy, J.C.; Altarriba, C.; Comella Company, A.; Pujol-Farriols, R.; Baños, J.E.; Galbany-Estragués, P.; Comella Cayuela, A. Psychological Distress, Burnout, and Academic Performance in First Year College Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 12, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, J.E.; Colonio-Salazar, F.B.; White, S. Supporting dentists' health and wellbeing - a qualitative study of coping strategies in 'normal times'. Br Dent J. 2021, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl, E.; Paisi, M.; Plessas, A. An individual-level approach to stress management in dentistry. BDJ Team 2022, 9, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, M.H.; Sethi, M.R.; Shaheen, N.; Javed, K.; Qazi, I.A.; Osama, M. Effect of academic stress, educational environment on academic performance & quality of life of medical & dental students; gauging the understanding of health care professionals on factors affecting stress: A mixed method study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessas, A.; Paisi, M.; Bryce, M.; et al. Mental health and wellbeing interventions in the dental sector: a systematic review. Evid Based Dent 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarian-Amiri, S.R.; Zabihi, A.; Qalehsari, M.Q. The challenges of supporting nursing students in clinical education. J Educ Health Promot. 2020, 31, 9–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Simms-Ellis, R.; Janes, G.; Mills, T.; Budworth, L.; Atkinson, L.; Harrison, R. Can we prepare healthcare professionals and students for involvement in stressful healthcare events? A mixed-methods evaluation of a resilience training intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020, 20, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, P.; Štofková, Z.; Poliaková, A.; Biňasová, V.; Loučanová, E. Coaching Approach as a Sustainable Means of Improving the Skills of Management Students. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne , M.J. & Sealey, J.V. Academic Coaching in an Online Environment: Impact on Student Achievement. In M. Shelley & V. Akerson (Eds.), Proceedings of IConSES 2019-- International Conference on Social and Education Sciences 2019, 122-126. Monument, CO, USA: ISTES Organization.

- Martínez, K.G.; Jorge, J.C.; Noboa-Ramos, C.; Estapé, E.S. Coaching tailored by stages: A valua-ble educational strategy to achieve independence in research. J Clin Transl Sci. 2021, 5, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.E. Academic/Success Coaching: A Description of an Emerging Field in Higher Education. (Doctoral dissertation). 2015. Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3148 (accessed 15 June 2024).

- Callaghan, G. Introducing a Coaching Culture within an Academic Faculty. Inter J Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 2022, 20, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, D.J. Academic coaching in higher education exploring the experiences of academic coaches. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2019, 2829. https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/2829 (accessed 15 June 2024).

- Antoniadou, M. Leadership and Managerial Skills in Dentistry: Characteristics and Challenges Based on a Preliminary Case Study. Dent J (Basel). 2022, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chichirez, C.M.; Purcărea, V.L. Interpersonal communication in healthcare. J Med Life. 2018, 11, 119–122. [Google Scholar]

- Umoren, R.; Kim, S.; Gray, M.M. Interprofessional model on speaking up behaviour in healthcare professionals: a qualitative study. BMJ Leader 2022, 6, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeir, P. , Degroote, S., Vandijck, D., Mariman, A., Deveugele, M., Peleman, R., Verhaeghe, R., Cambré, B., & Vogelaers, D. Job Satisfaction in Relation to Communication in Health Care Among Nurses: A Narrative Review and Practical Recommendations. Sage Open, 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwitters, M.T.; Kiesewetter, J. Resilience status of dental students and derived training needs and interventions to promote resilience. GMS J Med Educ. 2023, 15, Doc67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenman, R.; Tennekoon, V.; Hill, L.G. Measuring bias in self-reported data. Int J Behav Healthc Res. 2011, 2, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latkin, C.A.; Edwards, C.; Davey-Rothwell, M.A.; Tobin, K.E. The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addict Behav. 2017, 73, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhawaldeh, A.; Al Omari, O.; Al Aldawi, S.; Al Hashmi, I.; Ann Ballad, C.; Ibrahim, A.; Al Sabei, S.; Alsaraireh, A.; Al Qadire, M.; ALBashtawy, M. Stress Factors, Stress Levels, and Coping Mechanisms among University Students. Scientific World Journal. 2023, 29, 2026971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.; Ferradás, M.d.M.; Regueiro, B.; Rodríguez, S.; Valle, A.; Núñez, J.C. Coping Strategies and Self-Efficacy in University Students: A Person-Centered Approach. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (N=271) |

Dental department (n=145, 53.5%) |

Nursing department (n=126, 46.5%) |

χ2 test results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Gender | Male | 85 | 31.40% | 54 | 37.30% | 31 | 24.60% | χ2(1)=5, p = .025 |

| Female | 186 | 68.60% | 91 | 62.80% | 95 | 75.40% | ||

| Educational level | Postgraduate studies/PhD | 54 | 19.90% | 3 | 2.10% | 51 | 40.50% | χ2(1)=62.33, p < .001 |

| Undergraduate studies | 217 | 80.10% | 142 | 97.90% | 75 | 59.50% | ||

| Year of studies | 1st year | 12 | 4.3% | 5 | 3.4% | 7 | 5.3% | χ2(1)=62.17, p < .001 |

| 2nd year | 18 | 6.5% | 7 | 4.8% | 11 | 8.3% | ||

| 3rd year | 64 | 23.1% | 43 | 29.7% | 21 | 15.9% | ||

| 4th year | 52 | 18.8% | 18 | 12.4% | 34 | 25.8% | ||

| 5th year | 71 | 25.6% | 69 | 47.6% | 2 | 1.5% | ||

| Postgraduate students | 60 | 21.7% | 3 | 2.1% | 57 | 41.7% | ||

| Family income | < €15,000 | 32 | 16.20% | 14 | 14.60% | 18 | 17.80% | χ2(1)=24.71, p < .001 |

| €15,001-25,000 | 71 | 36.00% | 24 | 25.00% | 47 | 46.50% | ||

| €25,001-35,000 | 37 | 18.80% | 15 | 15.60% | 22 | 21.80% | ||

| €35,001-50,000 | 34 | 17.30% | 24 | 25.00% | 10 | 9.90% | ||

| > €50,000 | 23 | 11.70% | 19 | 19.80% | 4 | 4.00% | ||

| Stress somatization* | Department | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=271) |

Dental (n=145, 53.5%) |

Nursing (n=126, 46.5%) |

|||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

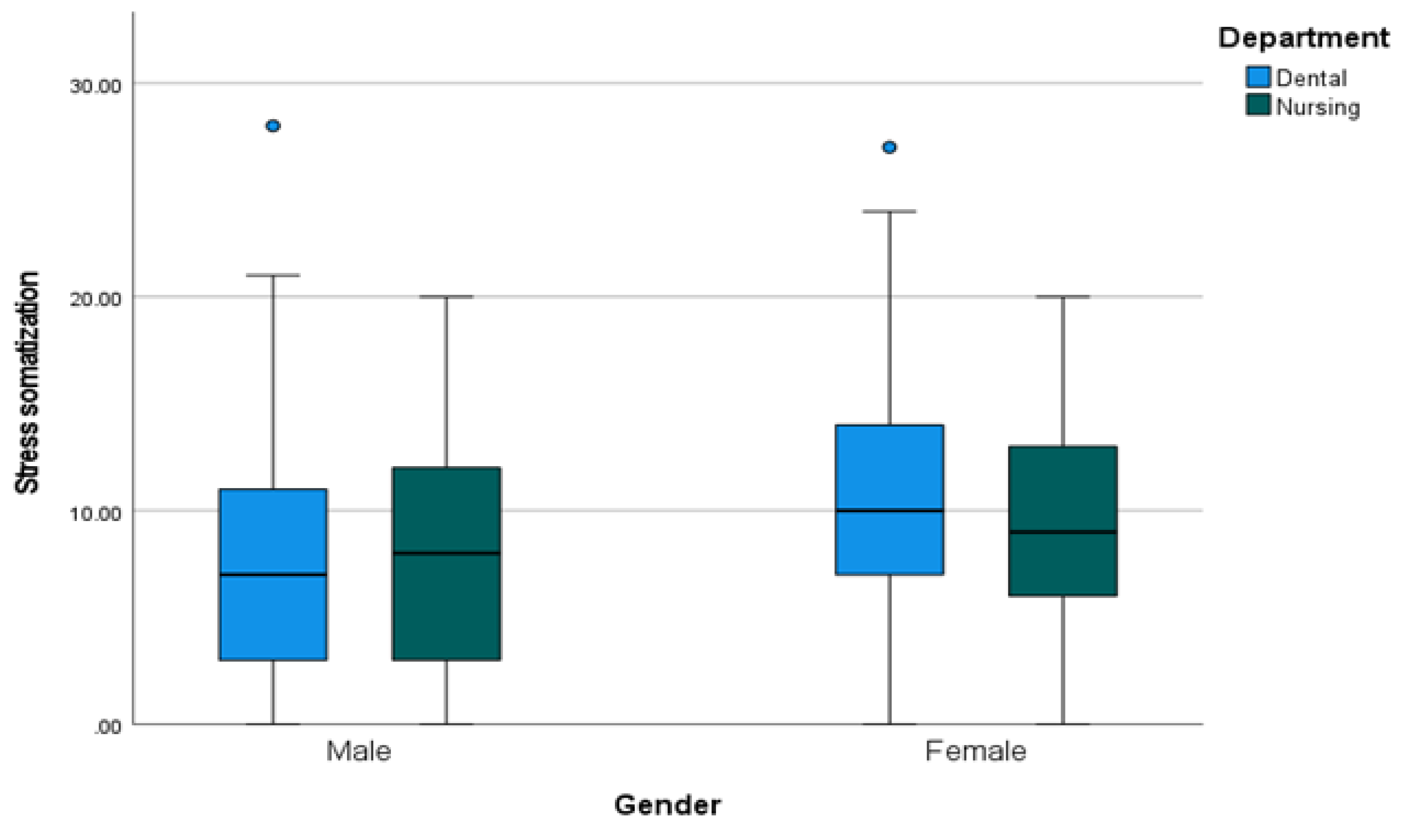

| Gender | Male (n=85, 31.4%) | 7.94A | 6.14 | 8.23a | 6.37 | 7.48a | 5.80 |

| Female (n=186, 68.6%) | 10.22B | 5.23 | 10.90a | 5.46 | 9.59a | 4.95 | |

| Total (Ν=271) | 9.51 | 5.62 | 9.92 | 5.93 | 9.06 | 5.23 | |

| Gender | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| 1.Do you experience pain in the facial area during the day and/or night? | Never, not applicable | 139 | 50.4% | 51a | 59.3% | 88a | 46.3% |

| Usually not applicable | 64 | 23.2% | 17a | 19.8% | 47a | 24.7% | |

| Not sure | 35 | 12.7% | 8a | 9.3% | 27a | 14.2% | |

| Very true | 31 | 11.2% | 7a | 8.1% | 24a | 12.6% | |

| Always applies | 7 | 2.5% | 3a | 3.5% | 4a | 2.1% | |

| 2.Do you hear a sound from the temporomandibular joint during movements of the mandible? | Never, not applicable | 131 | 47.5% | 49a | 57.0% | 82b | 43.2% |

| Usually not applicable | 41 | 14.9% | 7a | 8.1% | 34b | 17.9% | |

| Not sure | 44 | 15.9% | 17a | 19.8% | 27a | 14.2% | |

| Very true | 32 | 11.6% | 6a | 7.0% | 26a | 13.7% | |

| Always applies | 28 | 10.1% | 7a | 8.1% | 21a | 11.1% | |

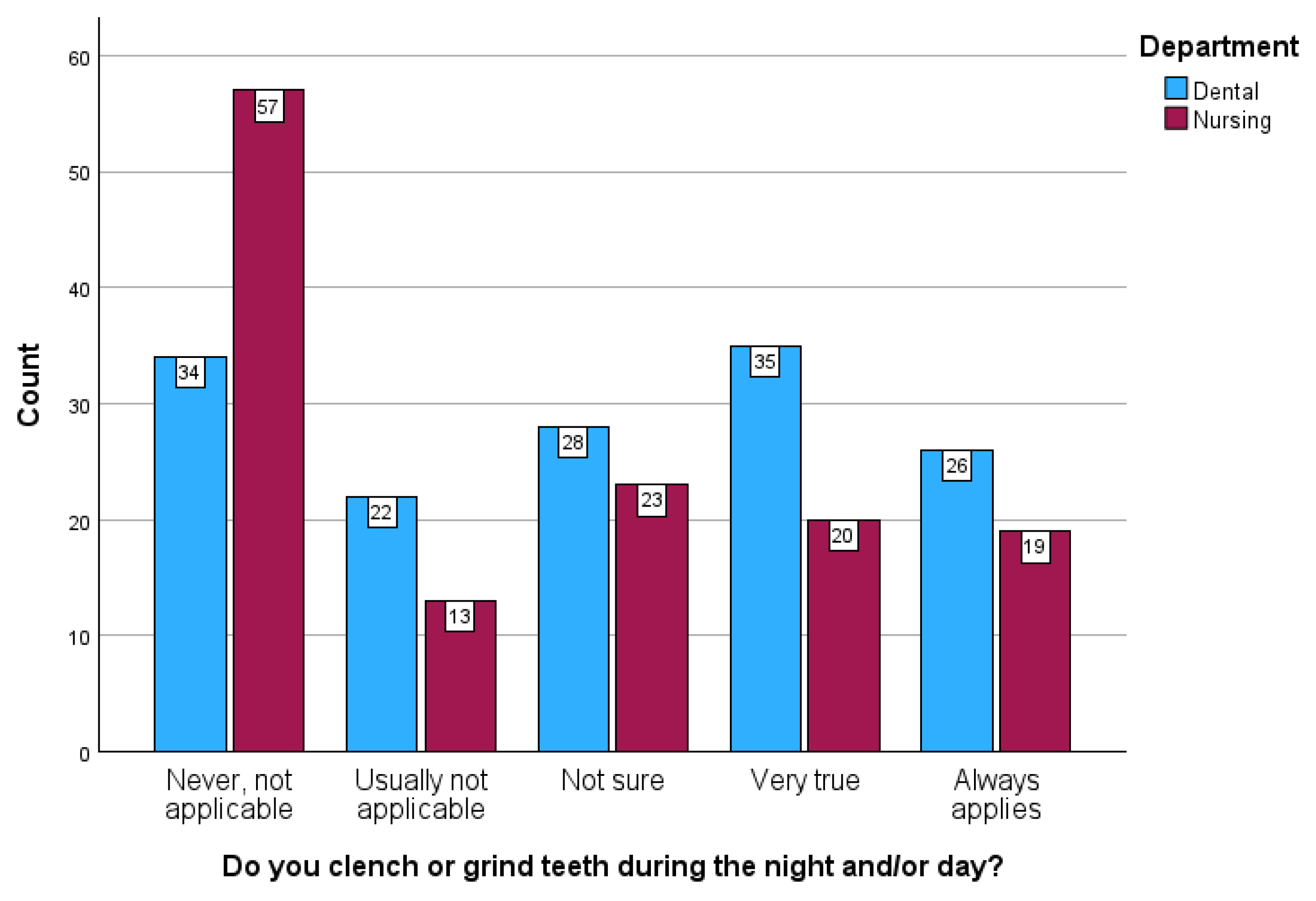

| 3.Do you clench or grind teeth during the night and/or day? | Never, not applicable | 91 | 33.0% | 33a | 38.4% | 58a | 30.5% |

| Usually not applicable | 35 | 12.7% | 11a | 12.8% | 24a | 12.6% | |

| Not sure | 51 | 18.5% | 14a | 16.3% | 37a | 19.5% | |

| Very true | 54 | 19.6% | 15a | 17.4% | 39a | 20.5% | |

| Always applies | 45 | 16.3% | 13a | 15.1% | 32a | 16.8% | |

| 4.Do you experience headaches? | Never, not applicable | 52 | 18.8% | 30a | 34.9% | 22b | 11.6% |

| Usually not applicable | 64 | 23.2% | 25a | 29.1% | 39a | 20.5% | |

| Not sure | 62 | 22.5% | 15a | 17.4% | 47a | 24.7% | |

| Very true | 57 | 20.7% | 7a | 8.1% | 50b | 26.3% | |

| Always applies | 41 | 14.9% | 9a | 10.5% | 32a | 16.8% | |

| 5.Is your sleep disturbed? | Never, not applicable | 63 | 22.8% | 26a | 30.2% | 37b | 19.5% |

| Usually not applicable | 74 | 26.8% | 20a | 23.3% | 54a | 28.4% | |

| Not sure | 61 | 22.1% | 15a | 17.4% | 46a | 24.2% | |

| Very true | 51 | 18.5% | 17a | 19.8% | 34a | 17.9% | |

| Always applies | 27 | 9.8% | 8a | 9.3% | 19a | 10.0% | |

| 6. Do you feel nervous-or/annoyed-at your relationships in the student/work environment? | Never, not applicable | 58 | 21.0% | 33a | 38.4% | 25b | 13.2% |

| Usually not applicable | 60 | 21.7% | 17a | 19.8% | 43a | 22.6% | |

| Not sure | 67 | 24.3% | 13a | 15.1% | 54b | 28.4% | |

| Very true | 65 | 23.6% | 18a | 20.9% | 47a | 24.7% | |

| Always applies | 26 | 9.4% | 5a | 5.8% | 21a | 11.1% | |

| 7. Are you taking medication to calm down from the responsibilities of everyday life? | Never, not applicable | 236 | 85.5% | 73a | 84.9% | 163a | 85.8% |

| Usually not applicable | 18 | 6.5% | 3a | 3.5% | 15a | 7.9% | |

| Not sure | 10 | 3.6% | 3a | 3.5% | 7a | 3.7% | |

| Very true | 6 | 2.2% | 5a | 5.8% | 1a | 0.5% | |

| Always applies | 6 | 2.2% | 2a | 2.3% | 4a | 2.1% | |

| Total sample | Dental/Total | Nursing/Total | Dental/Male | Dental/Female | Nursing/Male | Nursing/Female | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| What does "stress" mean to you? | ||||||||||||||

| Physical symptoms | 54 | 19.9% | 26 | 18.7% | 26 | 21.0% | 7 | 13.7% | 19 | 21.6% | 6 | 18.8% | 20 | 21.7% |

| Restlessness And Psychological Pressure | 93 | 34.3% | 57a | 41.0% | 35b | 28.2% | 23 | 45.1% | 34 | 38.6% | 9 | 28.1% | 26 | 28.3% |

| Difficulty Concentrating, Disorganization of thoughts and feelings, Numbness | 48 | 17.7% | 26 | 18.7% | 20 | 16.1% | 9 | 17.6% | 17 | 19.3% | 8 | 25.0% | 12 | 13.0% |

| Obsessive thoughts | 26 | 9.6% | 17 | 12.2% | 8 | 6.5% | 6 | 11.8% | 11 | 12.5% | 2 | 6.3% | 6 | 6.5% |

| Insecurity, Inability to handle unexpected or difficult situations, Panic | 104 | 38.4% | 48 | 34.5% | 52 | 41.9% | 17 | 33.3% | 31 | 35.2% | 15 | 46.9% | 37 | 40.2% |

| Fear of failure, lack of confidence | 18 | 6.6% | 10 | 7.2% | 8 | 6.5% | 4 | 7.8% | 6 | 6.8% | 2 | 6.3% | 6 | 6.5% |

| Pressure to meet daily obligations/long-term goals | 26 | 9.6% | 11 | 7.9% | 15 | 12.1% | 5 | 9.8% | 6 | 6.8% | 2 | 6.3% | 13 | 14.1% |

| How and where in the body do you experience stress? | ||||||||||||||

| Heart or chest discomfort | 107 | 41.8% | 54 | 41.2% | 50 | 42.7% | 22 | 46.8% | 32 | 38.1% | 10 | 34.5% | 40 | 45.5% |

| Digestive Disorders, Anorexia | 106 | 41.4% | 48 | 36.6% | 53 | 45.3% | 17 | 36.2% | 31 | 36.9% | 14 | 48.3% | 39 | 44.3% |

| Breathing Difficulties, Cough | 30 | 11.7% | 14 | 10.7% | 15 | 12.8% | 4 | 8.5% | 10 | 11.9% | 3 | 10.3% | 12 | 13.6% |

| Headaches, Nausea | 93 | 36.3% | 44 | 33.6% | 48 | 41.0% | 18 | 38.3% | 26 | 31.0% | 11 | 37.9% | 37 | 42.0% |

| General Muscle Tension and Discomfort | 28 | 10.9% | 13 | 9.9% | 13 | 11.1% | 7 | 14.9% | 6 | 7.1% | 4 | 13.8% | 9 | 10.2% |

| Dental Symptoms | 19 | 7.4% | 12 | 9.2% | 7 | 6.0% | 3 | 6.4% | 9 | 10.7% | 3 | 10.3% | 4 | 4.5% |

| Sweating, itching and skin diseases | 27 | 10.5% | 14 | 10.7% | 11 | 9.4% | 5 | 10.6% | 9 | 10.7% | 5 | 17.2% | 6 | 6.8% |

| How do you feel you can improve your resilience? | ||||||||||||||

| Dedication to work or study | 11 | 4.1% | 4 | 2.9% | 7 | 5.7% | 1 | 2.0% | 3 | 3.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 7 | 7.5% |

| Psychotherapy and Psychological Support | 47 | 17.4% | 23 | 16.5% | 20 | 16.3% | 7 | 14.0% | 16 | 18.0% | 4 | 13.3% | 16 | 17.2% |

| Managing Stressors | 70 | 25.9% | 31 | 22.3% | 39 | 31.7% | 14 | 28.0% | 17 | 19.1% | 14 | 46.7% | 25 | 26.9% |

| Planning - Time Management | 25 | 9.3% | 9 | 6.5% | 16 | 13.0% | 2 | 4.0% | 7 | 7.9% | 3 | 10.0% | 13 | 14.0% |

| Improving Physical Condition, Nutrition and Sleep | 29 | 10.7% | 21a | 15.1% | 8b | 6.5% | 7 | 14.0% | 14 | 15.7% | 2 | 6.7% | 6 | 6.5% |

| Emotional Balance and Self-Awareness | 93 | 34.4% | 47 | 33.8% | 43 | 35.0% | 15 | 30.0% | 32 | 36.0% | 12 | 40.0% | 31 | 33.3% |

| Social Support and Socialization | 20 | 7.4% | 10 | 7.2% | 8 | 6.5% | 2 | 4.0% | 8 | 9.0% | 1 | 3.3% | 7 | 7.5% |

| I don’t know | 22 | 8.1% | 14 | 10.1% | 8 | 6.5% | 7 | 14.0% | 7 | 7.9% | 1 | 3.3% | 7 | 7.5% |

| What strategy do you follow to immediately (at the same time) deal with stressful situations? | ||||||||||||||

| Breathing and Relaxation Techniques | 86 | 33.0% | 45 | 33.3% | 40 | 33.6% | 15 | 30.0% | 30 | 35.3% | 8 | 28.6% | 32 | 35.2% |

| Distraction and thought management | 42 | 16.1% | 19 | 14.1% | 21 | 17.6% | 6 | 12.0% | 13 | 15.3% | 3 | 10.7% | 18 | 19.8% |

| Analysis of the situation, staying cool, self-regulation | 101 | 38.7% | 53 | 39.3% | 47 | 39.5% | 21 | 42.0% | 32 | 37.6% | 11 | 39.3% | 36 | 39.6% |

| Organization and methodicality | 6 | 2.3% | 5 | 3.7% | 1 | 0.8% | 1 | 2.0% | 4 | 4.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.1% |

| Physical activity | 21 | 8.0% | 9 | 6.7% | 11 | 9.2% | 2 | 4.0% | 7 | 8.2% | 4 | 14.3% | 7 | 7.7% |

| Talking with Others and Social/Psychological Support | 38 | 14.6% | 20 | 14.8% | 16 | 13.4% | 3a | 6.0% | 17b | 20.0% | 4 | 14.3% | 12 | 13.2% |

| Hobbies, Entertainment and Leisure | 32 | 12.3% | 13 | 9.6% | 18 | 15.1% | 7 | 14.0% | 6 | 7.1% | 6 | 21.4% | 12 | 13.2% |

| What do you usually do when you are stressed for a long period (e.g. during an exam) | ||||||||||||||

| Patience / Nothing | 38 | 15.1% | 18 | 13.8% | 20 | 17.7% | 4 | 8.7% | 14 | 16.7% | 4 | 14.3% | 16 | 18.8% |

| Distraction and Entertainment | 80 | 31.9% | 39 | 30.0% | 38 | 33.6% | 13 | 28.3% | 26 | 31.0% | 9 | 32.1% | 29 | 34.1% |

| Analysis of the situation, Staying cool, Positive thoughts | 31 | 12.4% | 17 | 13.1% | 12 | 10.6% | 9 | 19.6% | 8 | 9.5% | 3 | 10.7% | 9 | 10.6% |

| Physical Exercise and Sports | 42 | 16.7% | 25 | 19.2% | 16 | 14.2% | 6 | 13.0% | 19 | 22.6% | 7 | 25.0% | 9 | 10.6% |

| Communication, Psychological/Social Support | 27 | 10.8% | 14 | 10.8% | 13 | 11.5% | 5 | 10.9% | 9 | 10.7% | 3 | 10.7% | 10 | 11.8% |

| Personal time and Personal Care | 33 | 13.1% | 16 | 12.3% | 15 | 13.3% | 6 | 13.0% | 10 | 11.9% | 8a | 28.6% | 7b | 8.2% |

| Strategic Thinking and Organization | 28 | 11.2% | 18 | 13.8% | 9 | 8.0% | 7 | 15.2% | 11 | 13.1% | 1 | 3.6% | 8 | 9.4% |

| Dedication to study | 17 | 6.8% | 6 | 4.6% | 11 | 9.7% | 3 | 6.5% | 3 | 3.6% | 2 | 7.1% | 9 | 10.6% |

| Spirituality | 5 | 2.0% | 4 | 3.1% | 1 | 0.9% | 2 | 4.3% | 2 | 2.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.2% |

| What would you suggest to your school administration to reduce the level of stress you and your fellow students experience? | ||||||||||||||

| Reduction of Curriculum Requirements and Hours, Flexibility in studies | 47 | 18.9% | 26 | 20.5% | 21 | 18.3% | 4a | 9.3% | 22b | 26.2% | 4 | 12.9% | 17 | 20.2% |

| Introduction of Psychological Support Programs | 46 | 18.5% | 15a | 11.8% | 28b | 24.3% | 4 | 9.3% | 11 | 13.1% | 4 | 12.9% | 24 | 28.6% |

| Revision of the educational Program, Better Organization, Staff evaluation | 112 | 45.0% | 65a | 51.2% | 43b | 37.4% | 21 | 48.8% | 44 | 52.4% | 13 | 41.9% | 30 | 35.7% |

| Better and more timely information about the curriculum/labs/exams and the resulting changes | 8 | 3.2% | 4 | 3.1% | 3 | 2.6% | 1 | 2.3% | 3 | 3.6% | 1 | 3.2% | 2 | 2.4% |

| More practice, better preparation | 14 | 5.6% | 11a | 8.7% | 3b | 2.6% | 3 | 7.0% | 8 | 9.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 3.6% |

| Improvement of physical spaces, infrastructure and working conditions | 15 | 6.0% | 13a | 10.2% | 2b | 1.7% | 6 | 14.0% | 7 | 8.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 2.4% |

| Improved communication and support, Better treatment by teachers and supervisors | 68 | 27.3% | 40 | 31.5% | 26 | 22.6% | 16 | 37.2% | 24 | 28.6% | 6 | 19.4% | 20 | 23.8% |

| Would you use the help of a coach to help you manage your anxiety? | ||||||||||||||

| Positive about support from a coach | 141 | 53.8% | 70 | 52.2% | 68 | 56.7% | 22 | 45.8% | 48 | 55.8% | 15 | 48.4% | 53 | 59.6% |

| Negative about support from a coach | 106 | 40.5% | 57 | 42.5% | 44 | 36.7% | 24 | 50.0% | 33 | 38.4% | 15 | 48.4% | 29 | 32.6% |

| Preference for support from mental health counselors | 18 | 6.9% | 9 | 6.7% | 9 | 7.5% | 3 | 6.3% | 6 | 7.0% | 1 | 3.2% | 8 | 9.0% |

| Stress Somatization | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dental | Nursing | |

| What does "stress" mean to you? | ||

| Physical symptoms | -0.099 | -0.093 |

| Restlessness And Psychological Pressure | -0.055 | 0.03 |

| Difficulty Concentrating, Disorganization of thoughts and feelings, Numbness | -0.029 | 0.066 |

| Obsessive thoughts | 0.037 | 0.01 |

| Insecurity, Inability to handle unexpected or difficult situations, Panic | 0.032 | .276* |

| Fear of failure, lack of confidence | -0.114 | -0.074 |

| Pressure to meet daily obligations/long-term goals | .187* | -0.152 |

| How and where in the body do you experience stress? | ||

| Heart or chest discomfort | -0.089 | 0.036 |

| Digestive Disorders, Anorexia | -0.011 | 0.002 |

| Breathing Difficulties, Cough | -0.035 | 0.054 |

| Headaches, Nausea | -0.005 | -0.103 |

| General Muscle Tension and Discomfort | -0.06 | -0.016 |

| Dental Symptoms | 0.106 | 0.059 |

| Sweating, itching and skin diseases | -0.073 | 0.027 |

| Stress Somatization | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dental | Nursing | |

| How do you feel you can improve your resilience? | ||

| Dedication to work or study | 0.109 | -0.038 |

| Psychotherapy and Psychological Support | 0.127 | 0.059 |

| Managing Stressors | 0.006 | -0.065 |

| Planning - Time Management | 0.090 | -0.038 |

| Improving Physical Condition, Nutrition and Sleep | -0.112 | -0.060 |

| Emotional Balance and Self-Awareness | -0.059 | 0.061 |

| Social Support and Socialization | -0.111 | -0.080 |

| I don’t know | -0.091 | -0.013 |

| What strategy do you follow to immediately (at the same time) deal with stressful situations? | ||

| Breathing and Relaxation Techniques | 0.037 | -0.051 |

| Distraction and thought management | -0.001 | 0.008 |

| Analysis of the situation, staying cool, self-regulation | -0.154 | -0.075 |

| Organization and methodicality | 0.120 | -0.083 |

| Physical activity | 0.018 | -0.054 |

| Social/Psychological Support | 0.134 | -0.074 |

| Hobbies and Recreational Activities | -0.046 | 0.046 |

| What do you usually do when you are stressed for a long period? | ||

| Patience / Nothing | .204* | 0.058 |

| Distraction and Entertainment | 0.138 | -0.08 |

| Analysis of the situation, staying cool, Positive thoughts | -.199* | 0.153 |

| Physical Activity and Sports | 0.06 | -.186* |

| Communication, Psychological/Social Support | -0.023 | 0.000 |

| Personal time and Personal Care | -0.112 | -0.015 |

| Strategic Thinking and Organization | -0.166 | -0.025 |

| Dedication to study | -0.028 | -0.029 |

| Spirituality | -0.005 | -0.087 |

| What would you suggest to your school administration to reduce the level of stress you and your fellow students experience? | Stress Somatization | |

|---|---|---|

| Dental | Nursing | |

| Reduction of Curriculum Requirements and Hours, Flexibility in studies | 0.130 | 0.005 |

| Introduction of Psychological Support Programs | 0.101 | -0.183 |

| Revision of the educational Program, Better Organization, Staff evaluation | 0.086 | 0.012 |

| Better and more timely information about the curriculum/labs/exams and the resulting changes | -0.038 | 0.097 |

| More practice, better preparation | 0.030 | 0.049 |

| Improvement of physical spaces, infrastructure, and working conditions | -0.081 | -0.008 |

| Improved communication and support, better treatment by teachers and supervisors | 0.050 | 0.073 |

| Stress somatization | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dental | Nursing | |

| Positive about support from a coach | .243** | -0.077 |

| Negative about support from a coach | -.238** | 0.067 |

| Preference for support from mental health counselors | 0.059 | 0.026 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).