1.4.1. Land Use Land Cover and Carbon Change

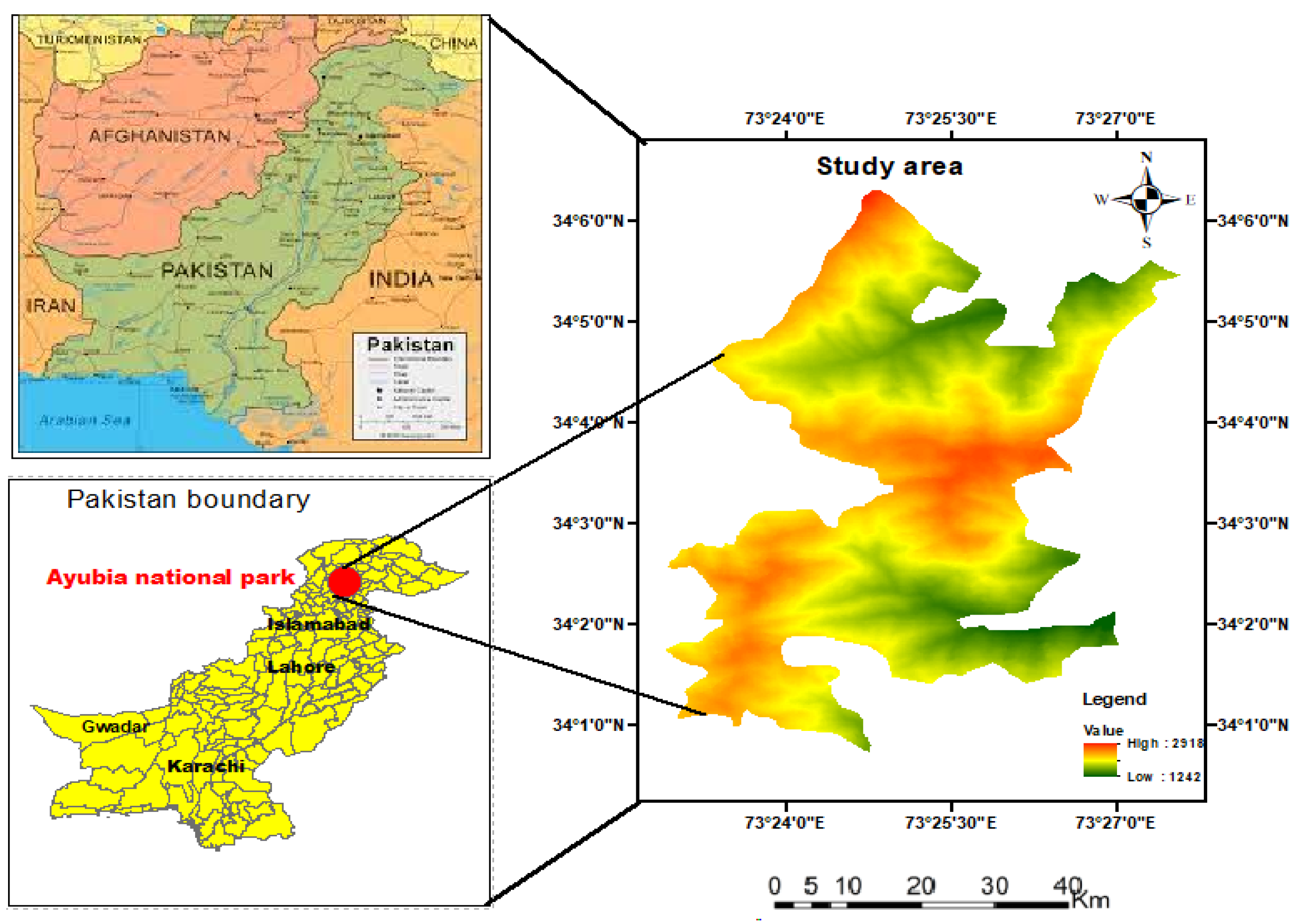

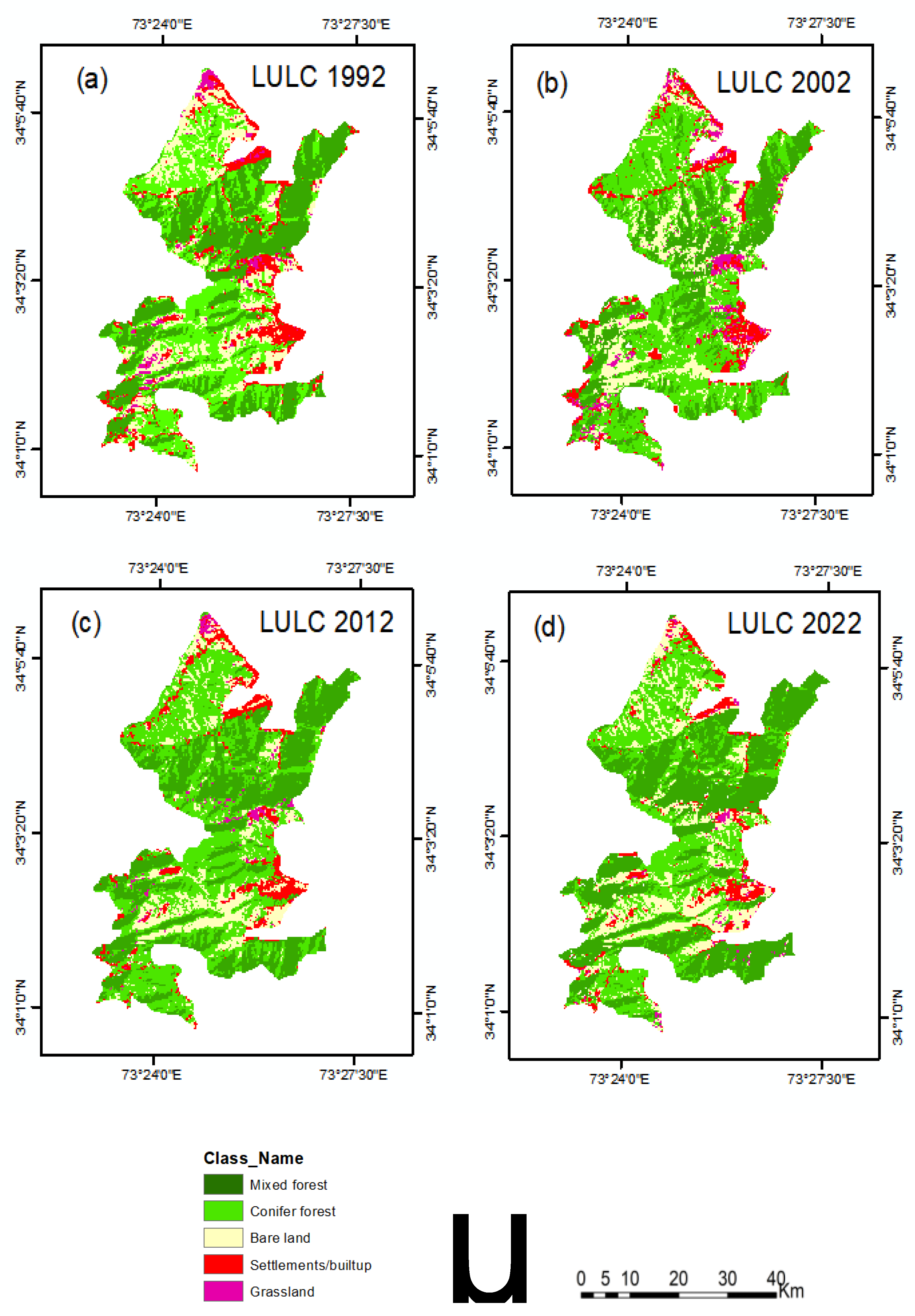

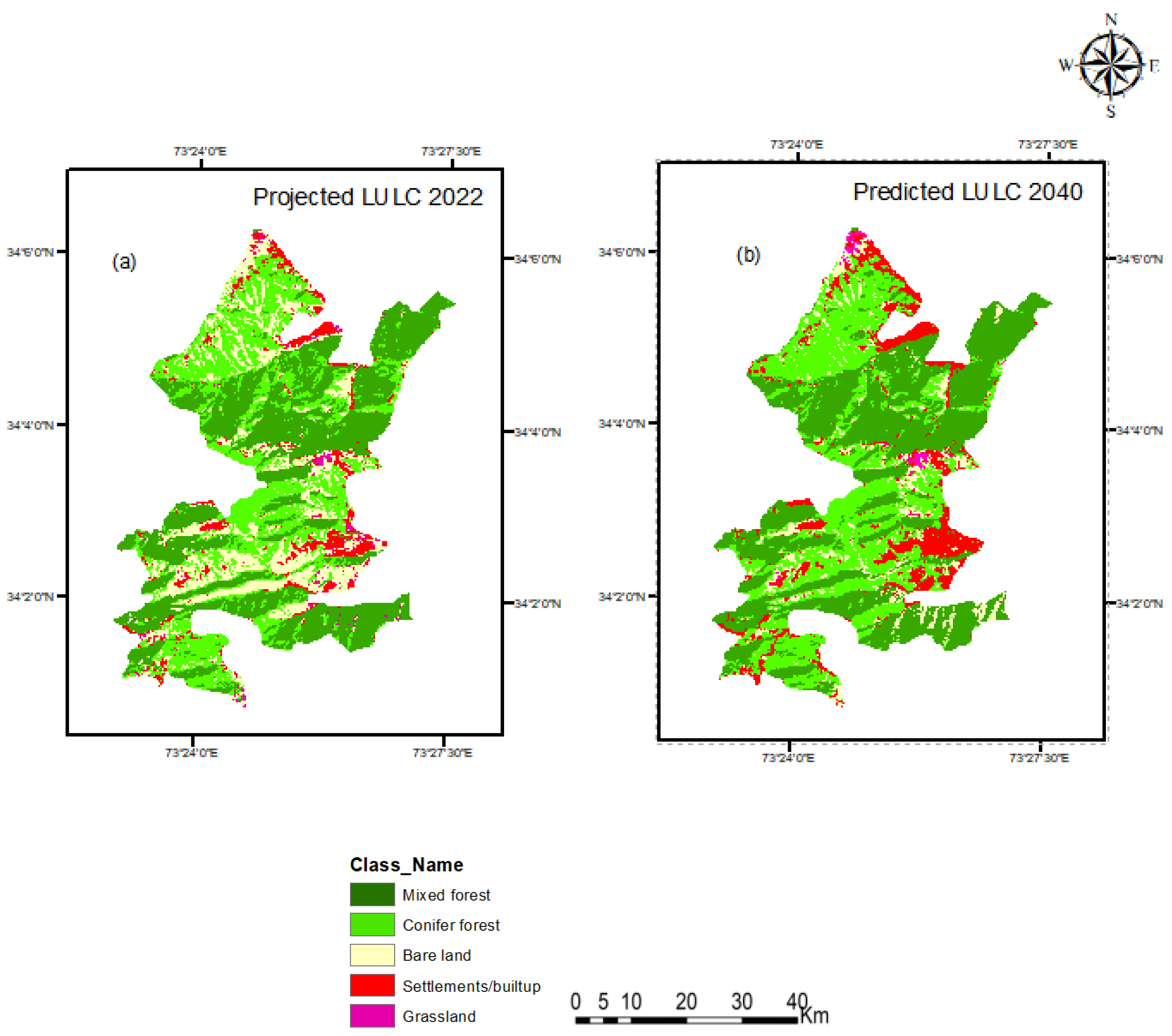

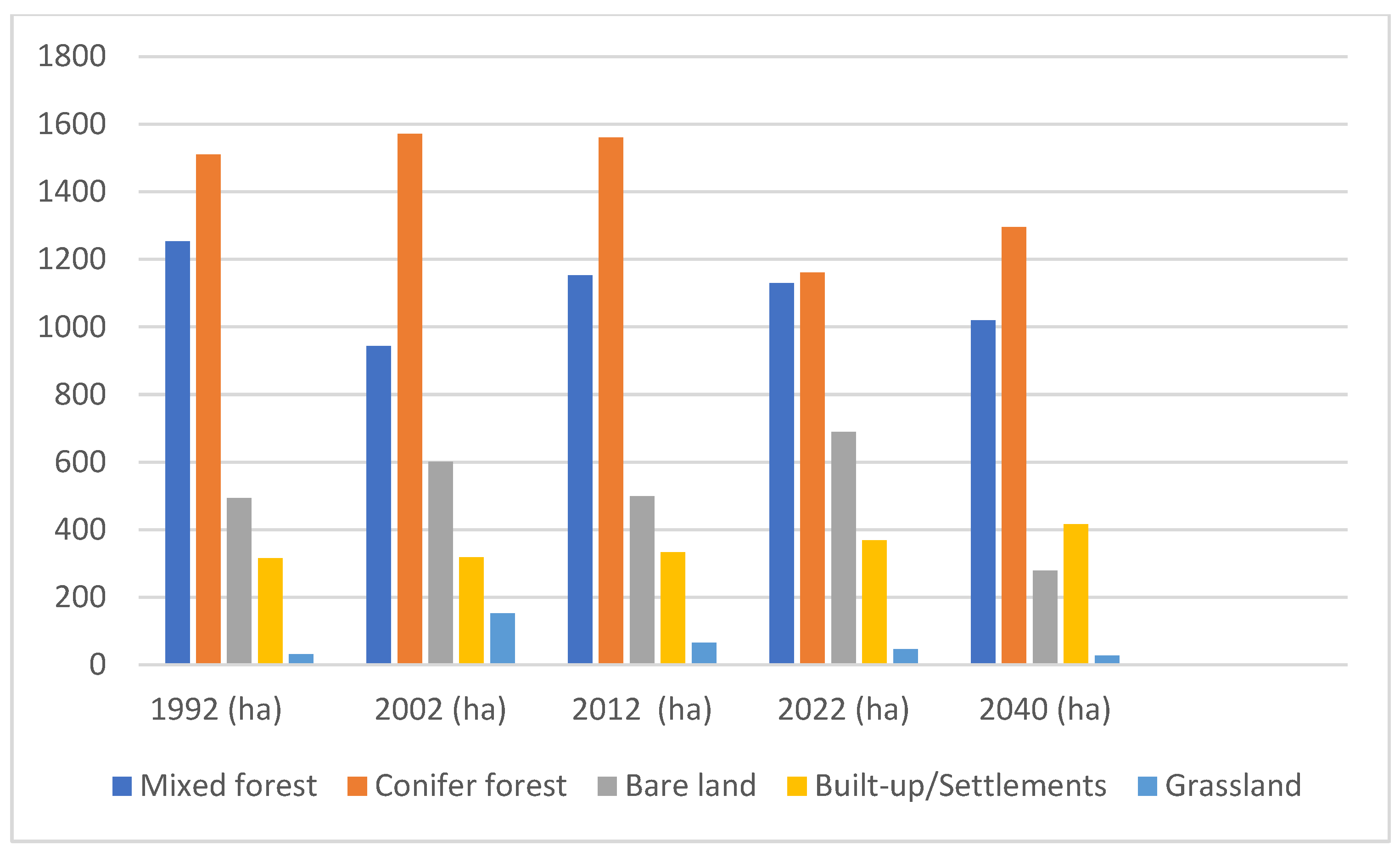

In Pakistan's temperate and subtropical areas, where LULC and deforestation are ongoing processes, natural forests are primarily found. The rise in SM and BL between 1992 and 2022 reveals the extent of LULC in the park. In comparison to our base year 1992, we discovered that SM has grown by 25.9% during the past 30 years. According to Figure 2-3, the SM for Ayubia increased from 315.06 to 368.23 between 1992 and 2022. Additionally, the number of SM in and around the park during 2022-2040 will increase more due to settlement growth(Waseem, Mohammad et al. 2005).

Figure 2-3.

LULC class changes.

Figure 2-3.

LULC class changes.

For instance, the CF decreased from 1510.2 hectares in the base year 1992 to 1161.09 ha in 2022. This downward trend in CF is comparable to that noted by Malik and Husain (2003; 48.4% in 1994, 54.8% in 2000). The uncontrolled and illegal logging by local villages for fuelwood, livestock grazing, and forest fires may be to blame for the transformation of CF into BL in and around the park. As is the case elsewhere in the world, forest fires frequently occur in ANP, particularly during the dry summer months(Ahmad and Javed 2007). These fires usually damage the CF more severely as compared to MF. The continuous reduction in the area under CF and increase in areas under BL and SM showed CF to have been mainly converted into BL, GL and SM.

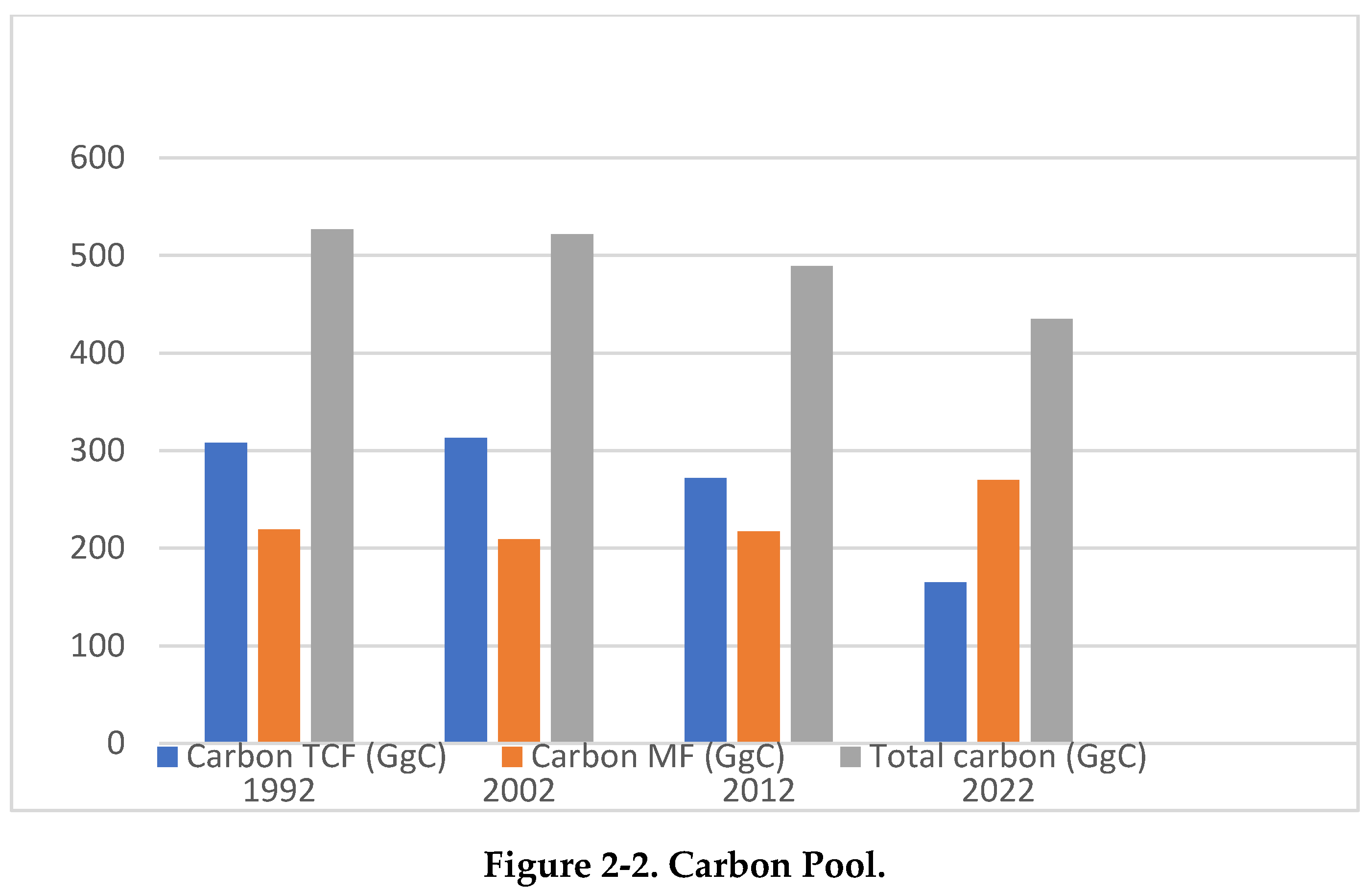

Carbon was computed with values ranging from 86.43 ± 8.25 in MF to 135.19 ± 9.74 in TCF. Similar findings were reported for the carbon store in the temperate woods of Nathiagali(Amir, Muhammad et al. 2022). Similarly, the stated figure by (Gandhi and Sundarapandian 2017) from the Indian Himalayan area conflicts with our current findings. The loss of carbon due to the conversion of forestland to other land uses decreased from 527 GgC in 1992 to 435 GgC in 2022. The same findings were previously published and demonstrated a loss of 32.7 PgC from Brazil's Amazonian protected areas in 2014(MohanRajan, Loganathan et al. 2020). Similar to this, more than 3 million km2 of US protected areas' forest, grassland, and shrubland were converted to agricultural land between 1700 and 2005, resulting in a 10,607 TgC loss(Núñez-Regueiro, Siddiqui et al. 2021) . This decrease in carbon corroborates the idea that forest land's capacity to store carbon is diminished as a result of conversion to other land uses. Forest conversion brought about by deforestation, agricultural development, and settlement growth linked to population increase led to a drop in carbon stock. Over these different periods, the highest rate of carbon losses was recorded for the period 2012-2022 as shown in Table 6-3. This period also coincided with the maximum of population growth and human migration within the study area. Although this LULC affects carbon loss, the intensity is much higher where CF is converted into SM, or BL (Ohler, Schreiner et al. 2023).

Table 6-3.

Forest carbon loss.

Table 6-3.

Forest carbon loss.

| |

Total carbon loss/gain (MgC) |

Net carbon loss (MgC) |

Net annual carbon loss (MgC∙yr-1) |

| TCF |

MF |

| 1992-2002 |

435.12 |

-140 |

295.12 |

29.5 |

| 2002-2012 |

410 |

+120 |

530 |

53.0 |

| 2012-2022 |

325 |

270 |

595 |

59.5 |

Between 1992 and 2022, Ayubia's population grew from 18,000 to nearly 55000,000. In addition to other environmental and socioeconomic issues, these demographic characteristics are the main causes of LUC in and around ANP (PKS 2019). Additionally, it was predicted that 16,000 people lived in nearby villages in 1992, but by 2022, this number had grown to almost 55,000, spread across 12 communities (Iqbal and Khan 2014). The viability of these natural environments is also seriously threatened by this demographic strain (Li, Yang et al. 2018, Ohler, Schreiner et al. 2023). The growth of built-up regions and the extraction of wood (fuel wood, artisanal, and commercial logging) are also influenced by this demographic pressure and contribute to the alteration of the forest cover and the deterioration of natural ecosystems(Jiyuan, Mingliang et al. 2002, Justice, Gutman et al. 2015). Anthropogenic activities pose serious hazards to the world's forest cover, according to several research (Rokityanskiy, Benítez et al. 2007, Sasmito, Taillardat et al. 2019). Historically, this increase in population and other underlying factors particularly in developing countries have been observed to be the most important driving force of LULC (Rosero-Bixby and Palloni 1998). According to (Tan, Ge et al. 2023), these underlying drivers of LULC are poverty, population growth, and socio-economic situation. Increased population often results in the migration of people in search of farmlands and forests are easier to convert to agricultural land(Luo, Hu et al. 2022). Rural areas around the ANP have experienced unchecked urban growth, which has forced these areas' rural areas into the region's wooded areas. Because National Parks feature high-quality limestone and sandstone needed for cement manufacture, stone mining for this purpose also contributes to carbon loss (Avtar, Tsusaka et al. 2020). Around the ANP, there are over 300 stone quarries, which have a negative impact on the flora, fauna, and 58 kinds of animals and over 900 plant species (The News, july 13, 2014). In a related research,(Khan, Khan et al. 2021) found that the primary causes of deforestation in the ANP region were uncontrolled harvesting, forest disease, and the removal of wood for commercial and domestic use.

Due to falling dry needles from conifer forests throughout the summer and dry season around May, forest fires frequently happen in the ANP. According to (de Groot, et al. 2009), the amount of carbon lost each year as a result of forest fires ranges from 50.2% to 57.6%, depending on the intensity of the fire. The majority of forest fires that started in Pakistan's temperate woods were unintentional as a result of carelessness and leisure activities. In Pakistan's temperate woods, surface fires have been seen to be trending upward(Amir, Muhammad et al. 2022). According to (Kauffman, Hughes et al. 2009), forest fires are known to decrease soil carbon, soil erosion, understory vegetation, and soil bareness. Livestock grazing and trampling have a negative impact on plant regeneration and contribute to LULC(Ahmad and Nizami 2015).

The research also covered the main causes of land use change and carbon loss in ANP, such as the exploitation of fuel wood for commercial purposes, population pressure and SM growth, which have a negative impact on the park's environment. Additionally, decreased forest area is a result of the construction of new infrastructure. These elements, when combined with lack governmental regulations and poor land use management strategies, encourage a decline in the amount of carbon stored in the ANP's forest biomass. This deforestation process may be slowed down, stopped, and even reversed by better forest management, sensible forest conservation laws, the creation of land use management plans, and urbanization controls.