Submitted:

12 June 2024

Posted:

13 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Group/subgroup 16 02: waste not otherwise specified in the catalog/waste from electrical and electronic equipment: of the 8 listed types of this kind of waste, as many as 6 are marked as hazardous waste, and

- Group/subgroup 20 01: municipal waste (domestic waste and similar comme0rcial industrial waste), including separately collected fractions (exception 15 01) - where 14 hazardous wastes are located with emphasis on discarded electronic and electrical equipment containing hazardous components.

- collection - carried out at the place of origin,

- sorting - involves sorting according to the categories of waste from electrical and electronic devices, and can be performed at the household level, at the local community level, at the landfill, or at recycling centers.

- separation - includes shredding, separation of recyclable from non-recyclable parts, and separation of useful components by one of the usual separation methods. The final quality of the recyclate depends on the efficiency of this step,

- final processing - involves the processing of previously separated recyclable materials by hydrometallurgical or pyrometallurgical process, and

- disposal of non-recyclable parts of e-waste.

- reducing the amount of waste,

- extending the exploitation life of the landfill,

- controlled management of hazardous waste, which is separated from nonhazardous waste in a timely manner by proper sorting,

- increasing the efficiency of recycling, and

- overall environmental protection.

- review the waste separation technologies using robots through a systematic review of current works,

- analyze the existing practice of e-waste management in the Republic of Serbia with reference to problems and potential solutions, and

- 3. examine the possibility of using robots in the e-waste separation process in Serbia on the specific example of the "E-Reciklaža" recycling center in Niš, Serbia.

2. Review of Works Dealing with the Application of Robots in Waste Separation

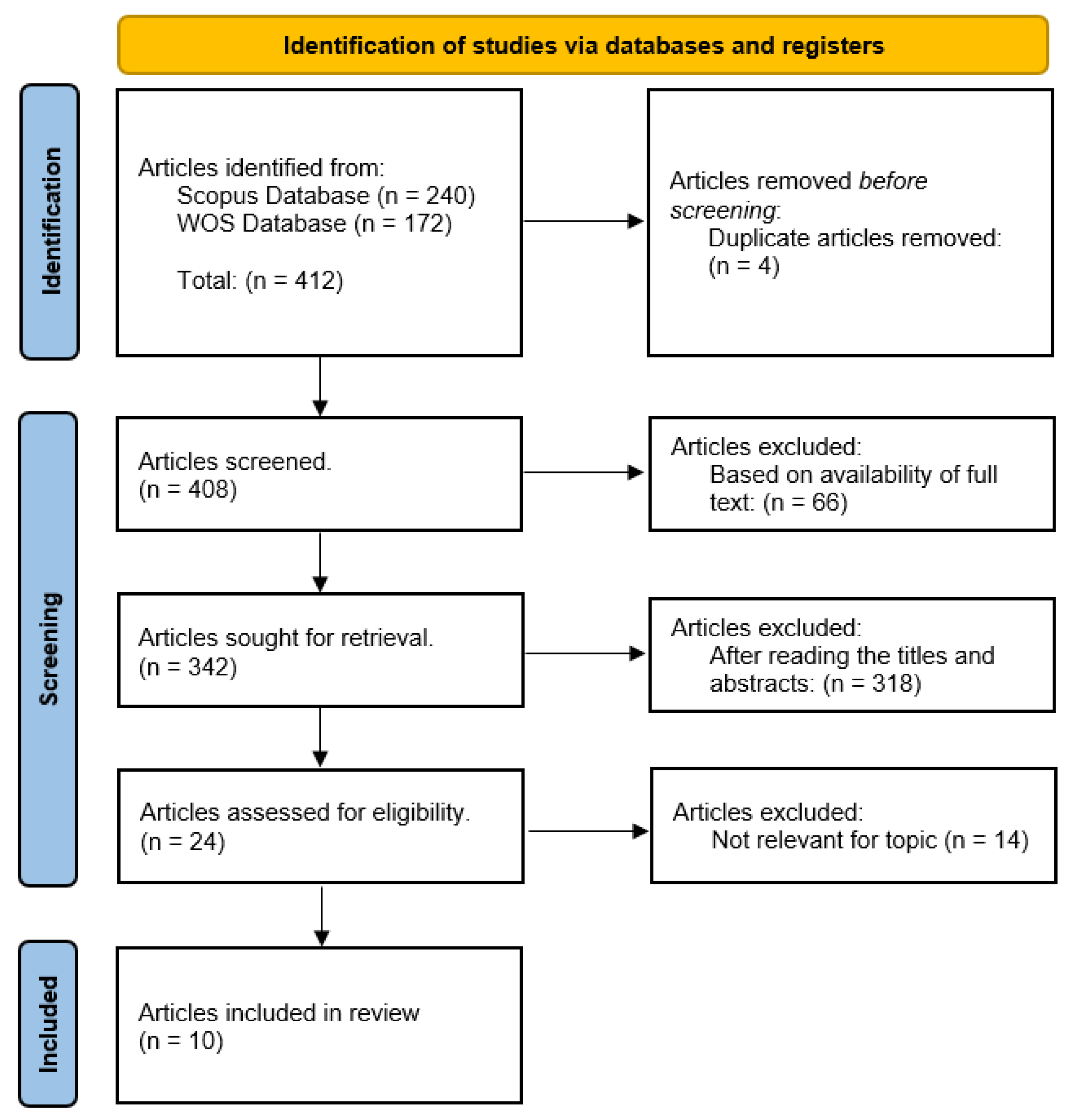

2.1. Selection of Papers

2.2. The Major Findings of the Selected Papers

- Level 1: Occlusion removal – removing objects that overlap other objects makes it easier for the vision system to recognize objects and capture them later.

- Level 2: Optimal distance – moving the object to allow enough space for the robot's gripper to grasp the object.

- Level 3: Optimum Grasping Position – placing the item to be sorted in a position that is ideal for grasping by the robot.

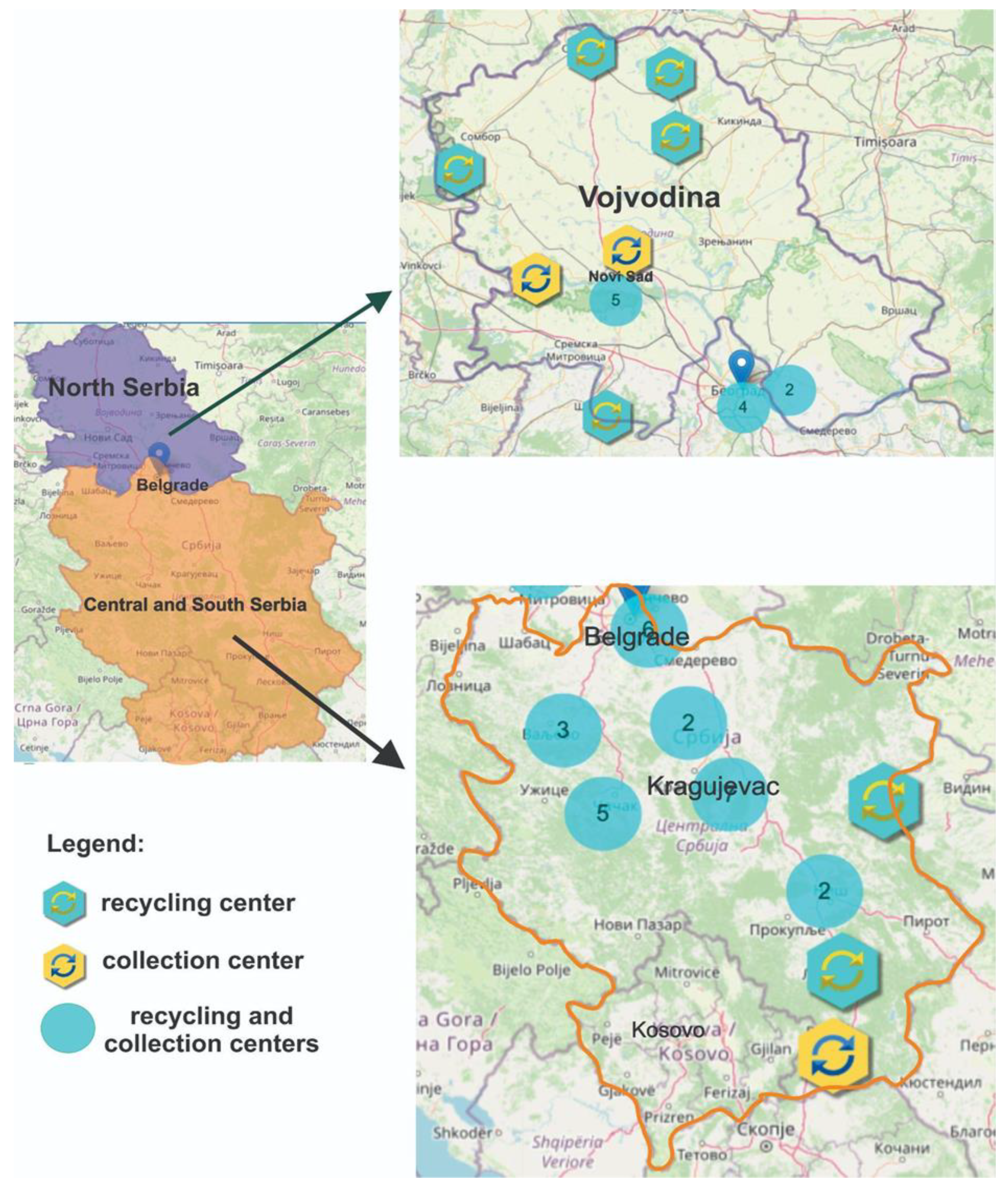

3. E-Waste Management in Serbia - Current Situation

3.1. Obstacles and Potential Solutions in the e-Waste Management System in Serbia

3.1.1. Legal Obstacles

- Absence of a legal framework for the establishment of collective and individual schemes according to the principle of waste management, "producer responsibility" in Serbian legal acts, as prescribed by Article 5 of Directive 2012/19/EU.

- Absence of a legal framework for establishing a National Register for manufacturers or importers of electrical and electronic equipment in Serbian legal acts, as prescribed by Article 16 of Directive 2012/19/EU.

- Absence of prescribed obligations of separate collection, treatment, reuse and disposal of e-waste in Serbian legal acts, as provided for in Articles 5, 12 and 13 of Directive 2012/19/EU.

- Absence of a prescribed financial guarantee by the manufacturer or importer of electrical and electronic equipment that they will finance the responsible management of e-waste in Serbian legal acts, as prescribed in Article 12 of Directive 2012/19/EU.

- Inconsistency of prescribed national goals for the collection and recycling of e-waste with European goals, prescribed by Article 7 of Directive 2012/19/EU. Moreover, Serbian legal acts do not define who is in charge of implementing the goals.

3.1.2. Organizational Obstacles

3.1.3. Sociological Obstacles

3.1.4. Potential Solutions to the Problem

- Improving and harmonizing legal acts with European ones, which would make e-waste management strictly controlled;

- Harmonizing e-waste recycling goals with European ones and intensive engagement in their fulfillment;

- Increasing environmental awareness among citizens of Serbia, through constant education and the implementation of a targeted campaign through the media;

- Incorporating the private sector into the e-waste management system, in order to influence the system from the production of electrical and electronic devices, by incorporating recyclable materials, building recycling facilities and financial motivation by the state;

- Supporting research activities in the field of development of innovative e-waste separation technologies, and

- Improving the infrastructure for e-waste management through the provision of all necessary facilities for the collection, transport, and recycling of e-waste.

4. Case Study: The possibility of Using Robots in e-Waste Separation in the "E-Reciklaža" Recycling Plant, Niš, Serbia

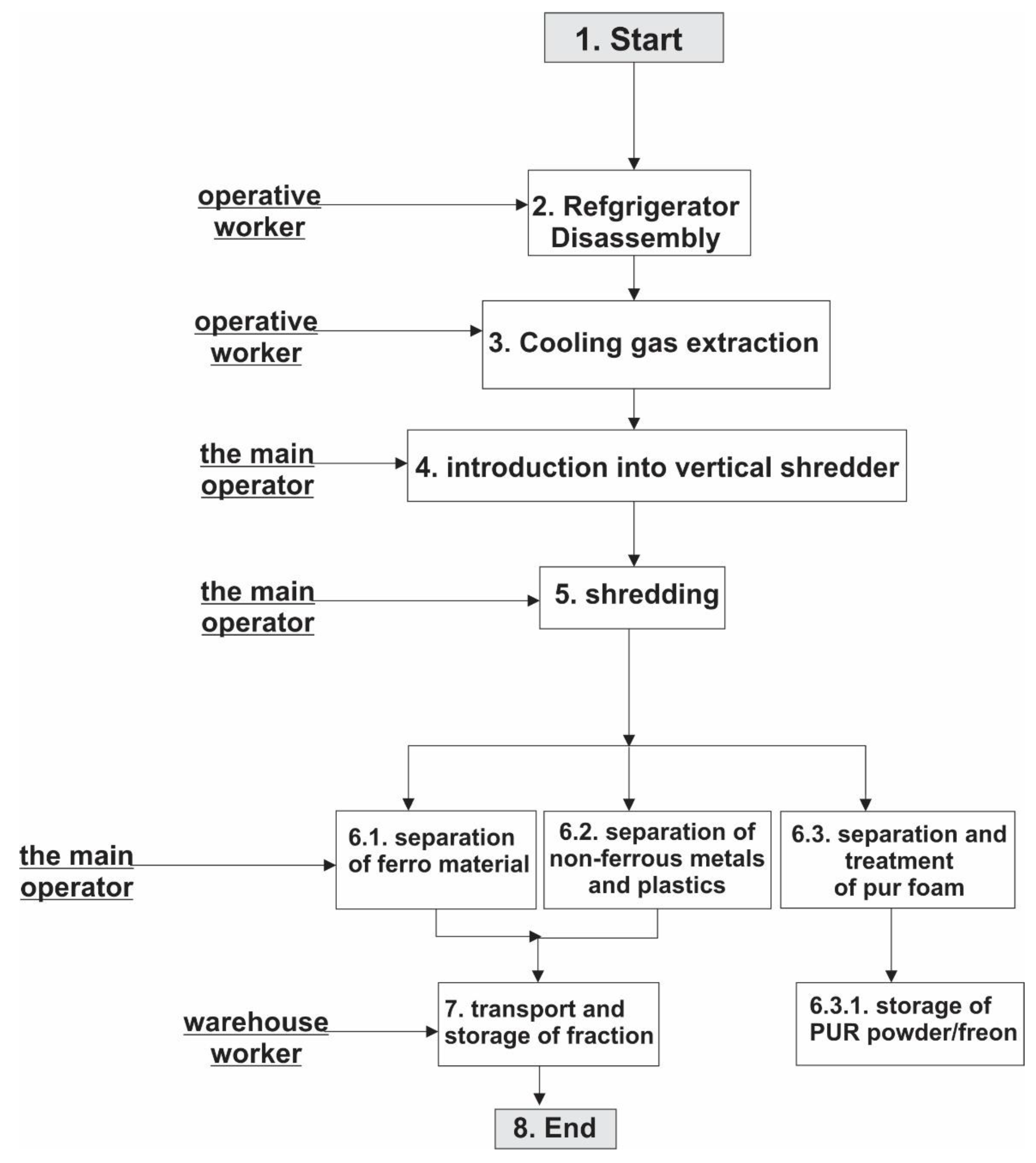

4.1. Description of the Refrigerator Recycling Procedure in the Recycling Facility "E-Reciklaža“

4.2. Identification of the Steps of the Recycling Process Suitable for Automation/Robotization

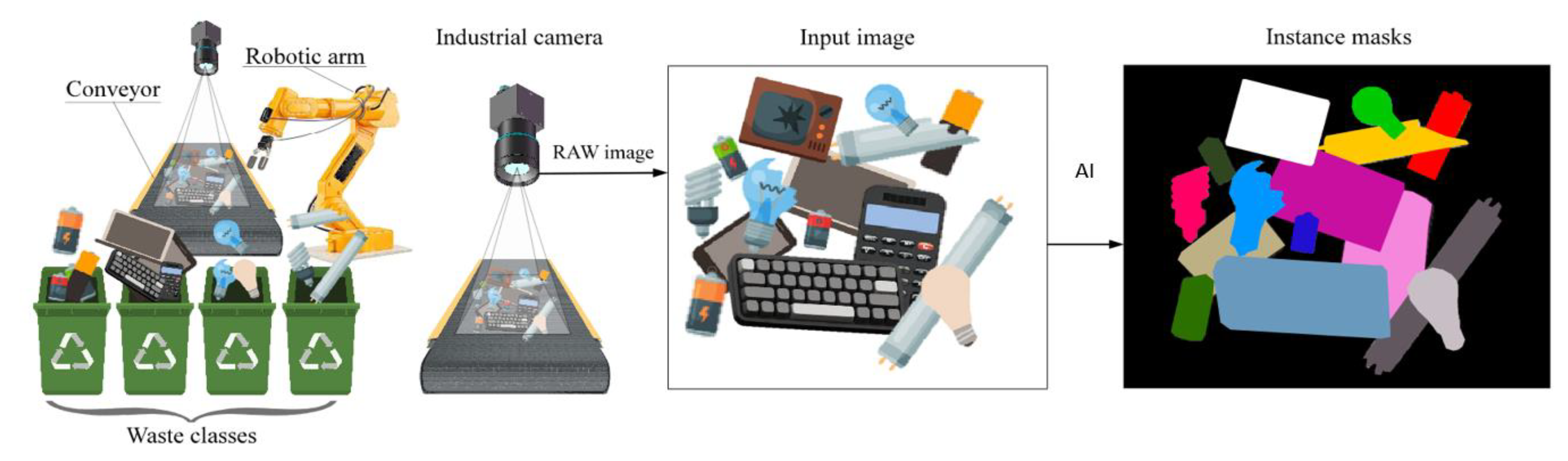

4.3. Technical Requirements Analysis and Proposed Solution

5. Conclusions

- Most often, automated processes or vision techniques, and collaborative robots assist humans in disassembling electrical devices during recycling. There aren't many examples that demonstrate the separation of shredded parts from e-waste. As it is not possible to create a universal e-waste recycling system due to the variety of types and forms of e-waste, the application of partial automation in the form of a flexible e-waste sorting station that would combine computer vision and collaborative robotic systems has great potential in recycling. This would make it possible to take advantage of the artificial intelligence, robotic systems, and the cognitive abilities of experienced workers that cannot be transferred to a robotic system, while the flexibility of the cell would be reflected in being easily adaptable for the separation of different types of e-waste that is recycled.

- The existing practice of e-waste management in Serbia is at a modest level, and the collection of this waste is done only sporadically through organized periodic collection actions by recyclers. We have not even come close to achieving the established national goals in terms of the e-waste recycling rate. The reason for this state of affairs is the inconsistency of domestic legislation with the European one, the lack of the necessary infrastructure for e-waste management at the local community and state level, as well as the insufficient environmental awareness of Serbian citizens.

- The possible use of robots in the e-waste separation process was looked at, using the recycling center "E-Reciklaža" as an example. It can be concluded that using robots in recycling would greatly improve workplaces that currently rely on manual labor and require workers to stand in awkward positions or deal with unhealthy materials like trash. The increased efficiency would have positive effects on wages, while the reduced workload would benefit the workers from sociological, ergonomic, and health perspectives. It would therefore have a positive impact on increasing Serbia's recycling rate.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kneževic, D.; Torbica S.; Rajkovic Z. and Nedic M. Industrial waste disposal. Faculty of Mining and Geology, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2014; pp. 1-7.

- Nišić, D.D., Cvjetić, A.S. and Knežević, D.N., Mine Waste. Tehnika 2019, 74(1), pp.47-55. [CrossRef]

- Nišić, D.D., Pantelić, U.R. and Nišić, N.D., Legal regulations of industrial solid waste management in Serbia: Challenges on the way of developing the circular economy. Tehnika 2024, 79(1), pp.47-54. [CrossRef]

- Waste management program of the Republic of Serbia for the period 2022-2031. Available online: https://www.ekologija.gov.rs/sites/default/files/2022-03/program_upravljanja_otpadom_eng_-_adopted_version.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Kirchherr, J., Reike, D. and Hekkert, M., Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, conservation and recycling 2017, 127, pp.221-232. [CrossRef]

- Rulebook on the list of electrical and electronic products, measures for prohibition and restriction of the use of electrical and electronic equipment containing hazardous substances, method and procedure for waste management of electrical and electronic products („Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia “, No. 99/2010). Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/pravilnik-listi-elektricnih-elektronskih-proizvoda-merama-zabrane-ogranicenja-koriscenja.html (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Rulebook on categories, testing and classification of waste, („Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia “, No. 56/2010, 93/2019 i 39/2021). Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/pravilnik-kategorijama-ispitivanju-klasifikaciji-otpada.html (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Tsydenova, O. and Bengtsson, M., Chemical hazards associated with treatment of waste electrical and electronic equipment. Waste management 2011, 31(1), pp.45-58. [CrossRef]

- The Law on Waste Management („Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia“, No. 36/2009, 88/2010, 14/2016, 95/2018 – other law and 35/2023), Available online:. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_upravljanju_otpadom.html (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Ramanayaka, S., Keerthanan, S. and Vithanage, M., Urban mining of E-waste: Treasure hunting for precious nanometals. Handbook of electronic waste management: 1st ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2020; Chapter: 2. pp. 19-54, ISBN: 978-0-12-817030-4.

- A new circular vision for electronics: Time for a global reboot; World economic forum. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_A_New_Circular_Vision_for_Electronics.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Shagun, A.K. and Arora, A., Proposed solution of e-waste management. International Journal of Future Computer and Communication 2013, 2(5), pp.490-493. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-de-los-Mozos, E. and Renteria, A., Collaborative robots in e-waste management. Procedia Manufacturing 2017, 11, pp.55-62. [CrossRef]

- Forti V., Baldé C.P., Kuehr R., Bel G. The Global E-waste Monitor 2020: Quantities, flows and the circular economy potential. United Nations University (UNU)/United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) – co-hosted SCYCLE Programme, International Telecommunication Union (ITU) & International Solid Waste Association (ISWA), Bonn/Geneva/Rotterdam 2020, ISBN Digital: 978-92-808-9114-0.

- Available online: https://allgreenrecycling.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Namias_Thesis_07-08-1312.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Shirodkar N, Terkar R. Stepped recycling: the solution for E-waste management and sustainable manufacturing in India. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2017, 4(8), pp. 8911-7. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://mohua.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/Part2.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Lu, W. and Chen, J., Computer vision for solid waste sorting: A critical review of academic research. Waste Management 2022, 142, pp.29-43. [CrossRef]

- Wills, B.A. and Barley, R.W. eds., Mineral processing at a crossroads: problems and prospects, Vol. 117. Springer, Germany, 2012, pp. 206-2010.

- Knežević, D.; Mineral Processing. Faculty of Mining and Geology, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2012. pp. 157-167.

- Gundupalli, S.P., Hait, S. and Thakur, A., A review on automated sorting of source-separated municipal solid waste for recycling. Waste management 2017, 60, pp.56-74. [CrossRef]

- Trumić, M., Trumić, M. and Bogdanović, G., Methods of plastic waste recycling with emphasis on mechanical treatment, Recycling and Sustainable Development 2012, 5(1), pp. 39-52. UDK: 628.477.6.043.

- Dodampegama, S., Hou, L., Asadi, E., Zhang, G. and Setunge, S., Revolutionizing construction and demolition waste sorting: Insights from artificial intelligence and robotic applications. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2024, 202, p.107375. [CrossRef]

- Safronova, Natalya B., and Gulnaz I. Khaibrakhmanova. Innovative Design of Waste Processing Technologies. Serbian Journal of Management 16 2021, no. 2, pp.453-462. [CrossRef]

- Thien-An Tran Luu, Hong-Minh Le, Minh-Quyen Vu, Bich-Van Nguyen, AI application for solid waste sorting in Global South. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/A41%20-%20Thien-An%20Tran%20Luu%20-%20AI%20Application%20for%20Solid%20Waste%20in%20the%20global%20south.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Aki, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S.,...Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLOS Medicine 2021, 18(3). [CrossRef]

- Kiyokawa, Takuya, Jun Takamatsu, and Shigeki Koyanaka. Challenges for Future Robotic Sorters of Mixed Industrial Waste: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2022, No. 21, pp. 1023-1040.

- Merdan, M., Lepuschitz, W., Meurer, T. and Vincze, M. Towards ontology-based automated disassembly systems. In Proceedings of IECON 2010-36th Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics Society. Arizona, USA, 2010 Nov 7 (pp. 1392-1397). [CrossRef]

- Bogue R. Robots in Recycling and Disassembly. Industrial Robot - The International Journal of Robotics Research and Application 2019. Vol.46(4), pp.461-6. [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Sana, Mohd Anjum, and M. Sarosh Umar. Deep Learning Applications in Solid Waste Management: A deep literature review. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2022, Vol. 13 (2), pp.381-395. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Himanshu, Harish Kumar, and Sachin Kumar Mangla. Enablers to computer vision technology for sustainable E-waste management. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, Vol. 412 Article 137396. [CrossRef]

- Deng, W., Liu, Q., Pham, D.T., Hu, J., Lam, K.M., Wang, Y. and Zhou, Z. Predictive exposure control for vision-based robotic disassembly using deep learning and predictive learning. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2024, Vol. 85, Article 102619. [CrossRef]

- Nafiz, Md Shahariar, Shuvra Smaran Das, Md Kishor Morol, Abdullah Al Juabir, and Dip Nandi., Convowaste: An automatic waste segregation machine using deep learning. In Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Robotics, Electrical and Signal Processing Techniques (ICREST), American International University-Bangladesh, January 7-9. 2023. pp. 181-186. [CrossRef]

- Ramadurai, Sruthi, and Heejin Jeong. Effect of human involvement on work performance and fluency in human-robot collaboration for recycling. In Proceedings of 17th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI). Sapporo, Japan, 7-10 March, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Luo, Y., Yerebakan, M.O., Xia, S., Behdad, S. and Hu, B. Human workload and ergonomics during human-robot collaborative electronic waste disassembly. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Human-Machine Systems (ICHMS). Orlando, Florida, USA, 17-19 November 2022. [CrossRef]

- Diedler, S., Hobohm, J., Batinic, B., Kalverkamp, M. and Kuchta, K., WEEE data management in Germany and Serbia. Global Nest Journal 2018 , 20, pp.751-757. [CrossRef]

- Report on special waste streams in the Republic of Serbia for 2022. Available online: http://www.sepa.gov.rs/download/Posebni_tokovi_2022.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Local waste management plan of the city of Belgrade 2021-2030. Available online: https://www.beograd.rs/images/file/b4b1aa1e6c2f3a2219a9c5e0f5f18a16_8185640472.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Where to recycle: interactive map. Available online: https://gdereciklirati.rs/# (accessed on 3 April 2014).

- Marinković, T., Batinić, B. and Stanisavljević, N., Analysis of the Current System of Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Management in the Republic of Serbia. Proceedings of the 47th Conference in the Field of Municipal and Industrial Wastewater, Municipal Solid Waste and Hazardous Waste, Pirot, Republic of Serbia, April 2017.

- Report on waste management in the Republic of Serbia for the period 2011-2022. Available online: http://www.sepa.gov.rs/download/Upravljanje_otpadom_2011-2022.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- European Parliament, 2024, E-waste in the EU: facts and figures (infographic). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20201208STO93325/e-waste-in-the-eu-facts-and-figures-infographic (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Directive 2012/19/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2012 on waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) (recast) Text with EEA relevance. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32012L0019 (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Obradović, L., Bugarin, M., Stevanović, Z., Mikić, M. and Lekovski, R., Overview of current domestic legislation in the field of waste management and disposal. Rudarski radovi 2, Mining and Metallurgy Institute Bor, pp.93-106. UDK: 340.134:628.4(045)=861.

- Negotiations with the EU/Negotiation Clusters/Chapter 27, Environment. Available online: https://www.mei.gov.rs/srp/obuka/e-obuke/vodic-kroz-pregovore-srbije-i-evropske-unije/klasteri/klaster-4/poglavlje-27-zivotna-sredina/ (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Mitić, L., Pavlović, M. and Vujanović, N., Management, regulation and reporting mechanisms on elеctronic waste recycling in Serbia. Ecologica 2023. 30(112), Scientific professional society for environmental protection of Serbia – ecologica, Belgrade, Serbia. pp.569-575. [CrossRef]

- Marinković, T., Berežni, I., Tošić, N., Stanisavljević, N. and Batinić, B., Challenges in applying extended producer responsibility policies in developing countries: A case study in e-waste management in Serbia. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Sustainable Solid Waste Management, Corfu, Greece, June 2022.

- Marinković, T., Berežni, I., Tošić, N., Stanisavljević, N. and Batinić, B., Optimization of WEEE collection system: Assessment of key influencing factors for different scenarios in Novi Sad, Serbia. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Sustainable solid waste management, Chania, Crete, Greece, 21-23 June 2023. poster section.

- Analysis of the Current System of Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Management in the Republic of Serbia. Available online: https://naled.rs/htdocs/Files/01854/Analiza-stanja-upravljanja-elektricnim-i-elektronskim-otpadom-u-Republici-Srbiji.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2014).

- Register of operators licensed to manage e-waste. Available online: http://www.sepa.gov.rs/index.php?menu=20174&id=20055&akcija=ShowExternal (accessed on 5 April 2014).

- Nedić B., Models of collecting e-waste, Proceedings of the 7th National Conference on the quality of the life, Kragujevac, Serbia, 7-9th June 2012.

- Sovilj-Nikić, S., Savković, T.R., Kovač, P.P. and Sovilj, B., Recycling of electronic and electrical equipment and introduction in national legislation of Serbia. Proceedings of the 13th International Research/Expert Conference” Trends in the Development of Machinery and Associated Technology”, Hammamet, Tunisia, 16-21 October 2009.

- L. Mitić, “Monitoring of E-Waste Recycling Data,” in Sinteza 2021 - International Scientific Conference on Information Technology and Data Related Research, Belgrade, Singidunum University, Serbia, 2021, pp. 296-300. [CrossRef]

- V. L. Minić and M. M. Jovanović, Environmental education and education in younger grades of primary school (in Serbian), Proceedings of the Faculty of Philosophy in Priština, Vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 125-144, 2019. [CrossRef]

- UpPet project, This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 953214. Available online: https://uppet.eu/ (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Nisic, D., Knezevic, D., Petkovic, A., Ignjatovic, M. and Kostadinovic, J., Study of general environmental awareness of the urban population. Proceedings of the 4th Human and Social Sciences at the Common Conference. University of Zilina, Zilina, Slovakia, November 2016.

- Dimić, V., Milošević, M. and Milošević, A., Developing awareness about e-waste management in information technology. Proceedings of 4th International Scientific Conference Agribusiness MAK-2017 „EUROPEAN ROAD“ IPARD 2015-2020, Kopaonik, Serbia, 27-28 January 2017. pp. 321-329.

- Vučković D. A Model for Sustainable Electrical and Electronic Waste Management in Serbia (in Serbian). Faculty of Economics and Engineering Management in Novi Sad, University Business Academy in Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia, 2019.

- Decision on Establishing the National Environmental Protection Program. Available online: https://www.ekologija.gov.rs/sites/default/files/2021-01/nacionalni-program-zastite-zivotne-sredine-r.srbija.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Gundupalli Paulraj, S., Hait, S. and Thakur, Automated Municipal Solid Waste Sorting for Recycling Using a Mobile Manipulator. Proceedings of the International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Vol. 5A. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Charlotte, North Carolina, USA, August 2016. [CrossRef]

- Brazier, J.P. and Prasetyo, J., Robotic Solution for the Automation of E-waste Recycling. Journal of Applied Science and Advanced Engineering 2023, 1(1), pp.11-17. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-de-los-Mozos, E., Rentería-Bilbao, A. and Díaz-Martín, F., WEEE recycling and circular economy assisted by collaborative robots. Applied Sciences 202, 10(14), p.4800. [CrossRef]

- E-reciklaža, About us. Available online: https://www.ereciklaza.com/ (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- E-reciklaža 2010 d.o.o., Machine Recycling of Refrigerators and E-waste, Unpublished internal company document, Niš, Sebia, 2010.

- Lu W, Chen J. Computer vision for solid waste sorting: A critical review of academic research. Waste Management. 2022, Vol. 142, pp- 29-43.

- Sterkens W, Diaz-Romero D, Goedemé T, Dewulf W, Peeters JR. Detection and recognition of batteries on X-Ray images of waste electrical and electronic equipment using deep learning. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2021, Vol. 168, No.105246. [CrossRef]

- Neelakandan S, Prakash M, Geetha BT, Nanda AK, Metwally AM, Santhamoorthy M, Gupta MS. Metaheuristics with Deep Transfer Learning Enabled Detection and classification model for industrial waste management. Chemosphere. 2022, Vol. 308, No. 136046. [CrossRef]

- NACHI-FUJIKOSHI CORP, Standard cycle time explanation. Available online: https://www.nachi-fujikoshi.co.jp/eng/mz07/fastest02.html (accessed on 3 June 2024).

| Reference | Country of the first author | Insights |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Kiyokawa et al., 2022 [27] | Japan |

|

| 2. Merdan et al., 2010 [28] | Austria |

|

| 3. Bogue, 2019 [29] | United Kingdom |

|

| 4. Alvarez-de-los-Mozos and Renteria, 2017 [13] | Spain |

|

| 5. Shahab et al., 2022 [30] | Saudi Arabia |

|

| 6. Sharma et al., 2023 [31] | India |

|

| 7. Deng et al., 2024 [32] | China |

|

| 8. Nafiz et al., 2023 [33] | Bangladesh |

|

| 9. Ramadurai et al., 2022 [34] | Chicago, USA |

|

| 10. Chen et al., 2022 [35] | Florida, USA |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).