1. Introduction

Colchicine is a toxic natural product isolated from the plant

Colchicum autumnale (autumn crocus or meadow saffron) and

Gloriosa superba (glory lily), plants of the

Colchiaceae family. It is a nitrogen-containing substance that is often misdescribed as an alkaloid, although its biosynthetic precursor, demecolcine, is such [

1].

Colchicine is one of the earliest drugs described. In an Egyptian medical papyrus of herbal knowledge from 1550 BC (the

Ebers Papyrus) it is described as a herbal remedy for joint pain/joint swelling [

2,

3].

Colchicine’s name may have come from its use as a poison in the district of Colchis of ancient Greece. Medea, the daughter of the king of Colchis and a sorceress, used it as one of her poisons, and it was referred to in Greek mythology as “the destructive fire of the Colchicon Medea.” [

4,

5].

In the first century CE, the Greek physician and pharmacologist Pedanius Dioscorides first described the use of colchicum extract for gout treatment in his pharmacopeia,

De Materia Medica [

5]. Colchicine has been described in various texts from Persia and Turkey, and it was listed in the London Pharmacopeia from 1618 [

5]. Colchicine is the main ingredient of a commercial remedy “Eau Medicinale” created in the 18th century by a French military officer, Nicolas Husson to treat gout. This product was used successfully by Benjamin Franklin to treat his own gout [

4].

Colchicine was first isolated in 1820 by the French chemist Pierre-Joseph Pelletier (1788-1842) and the French chemist and pharmacist Joseph-Bienaimé Caventou (1795-1877) [

6]. In 1833, the German chemist and pharmacist Philipp Lorenz Geiger (1785-1836) purified an active ingredient, named colchicine [

7,

8] which has ever since remained in use as a purified natural product. The full synthesis of colchicine was achieved by the Swiss organic chemist Albert Eschenmoser in 1959 [

9].

Colchicine was first registered in 1947 in France (

Colchicine capsule". DailyMed. Retrieved 27 March 2019). Although Benjamin Franklin credited the colchicine introduction to the USA as early as the 18th century [

4], it was not until July 2009 when the US Food and Drug Administration approved it as a monotherapy for the treatment of three different indications: familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), acute gout flares, and prophylaxis of gout flares under the Unapproved Drugs Initiative [[1

,10].

2. Other Uses of Colchicine

Colchicine is being used in rheumatology, dermatology, cardiology, and neurology. Beyond for treatment of gout and FMF, colchicine is also routinely used in other rheumatic diseases, such as acute flares in calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD) [

11] and osteoarthritis of the knee [

12].

Colchicine is also widely used to treat a variety of dermatological conditions as papulosquamous dermatoses, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, Sweet′s syndrome, bullous disease, linear IgA disease, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood, leucocytoclastic vasculitis, urticarial vasculitis and scleroderma, erythema nodosum leprosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, severe cystic acne, calcinosis cutis, keloids, sarcoid fibromatosis, condyloma acuminata, actinic keratosis, relapsing polychondritis, primary anetoderma, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, erythema nodosum, sclerodema, chronic urticaria, oral aphthosis, genital aphthosis, pseudo-alveolitis, Behçet’s syndrome and PFAPA syndrome (periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis). Although colchicine is not a first-line drug for any of the conditions mentioned, it is mostly used early in patients with leukocytoclastic vasculitis, Sweet's syndrome, and aphthous ulcers [

2,

12,

13,

14].

The cardioprotective effects of colchicine are well known and might be due at least to its ability to inhibit the pro-thrombotic activity of oxLDL [

15] and leukocyte-platelet aggregation [

16]. Low colchicine doses are recommended for pericarditis, post-pericardiotomy syndrome, postoperative atrial fibrillation, secondary cardiovascular prevention and in-stent restenosis, stroke prevention, vascular inflammation prevention, myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, coronary artery disease, as well as acute minor ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack and prevention of cerebrovascular ischemia in patients with extra- or intracranial atherosclerosis or arteriolosclerosis [

12,

17,

18]. In June 2023, the U.S. FDA approved colchicine (brand name

Lodoco), in a dose of 0.5mg per day, that targets residual inflammation, to reduce the risk of further disorders in elderly people with existing atherosclerotic

cardiovascular diseases [

19].

Colchicine exerts its antiproliferative effects through the inhibition of microtubule formation by blocking the cell cycle at the G2/M phase and triggering apoptosis. Interestingly, comparing cancer incidence in “ever-users” versus “never-users” of colchicine, significantly lower incidence of all types of cancers (especially prostate and colorectal) was demonstrated in the colchicine “ever-users” when compared to the “never-users” [

20]. Also, colchicine has a potential for the

palliative treatment of gastric cancer, of hepatocellular carcinoma and

cholangiocarcinoma at high (6ng/mL), but clinically acceptable colchicine concentration [

21]. Recent findings suggest as well that colchicine has a therapeutic potential in osteosarcoma [

22].

3. Why Is Colchicine Being Tested for the Treatment of COVID-19?

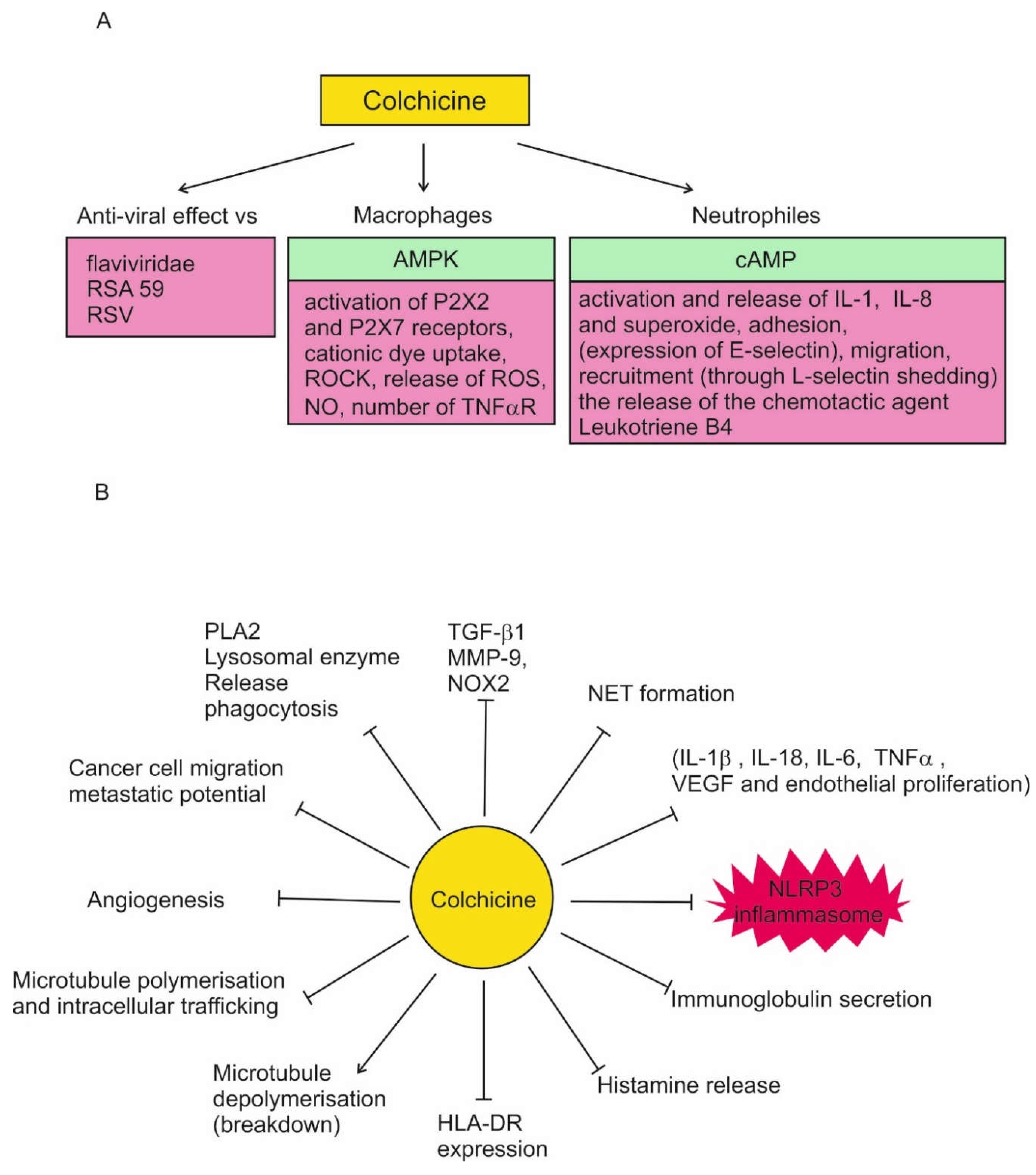

Colchicine has a number of effects that suggest it may be useful in the treatment of COVID-19. These effects are synthesized in

Figure 1. High colchicine concentrations suppress phagocytosis, PLA2 activation, and lysosomal enzyme release.

In leukocytes, colchicine inhibits microtubule polymerization, reducing their adhesion, recruitment and activation. This leads to inhibition of vesicle transport, cytokine secretion, phagocytosis, migration and division.

In neutrophils, nanomolar concentrations of colchicine alter the E-selectin distribution in vitro, thus reducing cell adhesion, chemotaxis, cell motility and lysosomal enzyme release during phagocytosis. At micromolar concentration it decreases L-selectin expression in vitro and in vivo which leads to neutrophil-endothelial adhesion inhibition. Colchicine modulates their deformability to suppress neutrophil extravasation, inhibits superoxide anion production and neutrophil infiltration in a dose dependent manner in vivo. The disruption of microtubule polymerization seems to explain all of these effects. Colchicine increases leukocyte cAMP, which suppress neutrophil function.

In macrophages colchicine inhibits activation of P2X2 and P2X7 receptors, NLRP3 inflammasome, the release of reactive oxygen (ROS) and nitrite oxide (NO). It can decrease the number of TNF-α receptors on the surface of macrophages (and endothelial cells). Colchicine activates the nutritional biosensor AMPK, transducing multiple anti-inflammatory effects of both colchicine and RhoA, which suppresses pyrin activity, that in turn inhibits the release of IL-1 & IL-1β, thus reducing the inflammatory process.

Colchicine has been found to inhibit significantly MMP-9, NOX2, and TGF-β1, which levels are increased in ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients

Regarding the effect of colchicine on COVID-19, the most important property is its inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome

in vitro at micromolar concentrations. It reduces leukocytes inflammation by inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1, and therefore leading to secondary reductions in cytokines such as 1L-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 [

14,

23,

24,

25].

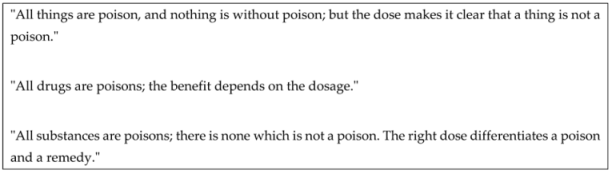

4. Game of Doses

The "Father of toxicology", Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim known as Paracelsus (1493-1541) was a German-Swiss homo universalis, physician, alchemist, lay theologian, astrologer and philosopher of the German Renaissance. His interests included medicine, chemistry and toxicology.

Sola dosis facit venenum [Paracelsus, dritte defensio, 1538]

"Only the dose makes the poison"

Paracelsus was the first to emphasize the importance of dosing in distinguishing between toxicity and treatment [

26]. Paracelsus presented the concept of dose response in his Third Defense in response to criticisms against his use of inorganic substances in medicine as too toxic to be used as therapeutic agents [

27]. His classic answer was “What is that there is not a poison? All things are poison, and nothing is without poison. Solely the dose determines that a thing is not a poison [

18,

28,

29].

Variants (F. Geerk, Paracelsus: Arzt unserer Zeit [Paracelsus: Doctor of Our Time] (1992)):

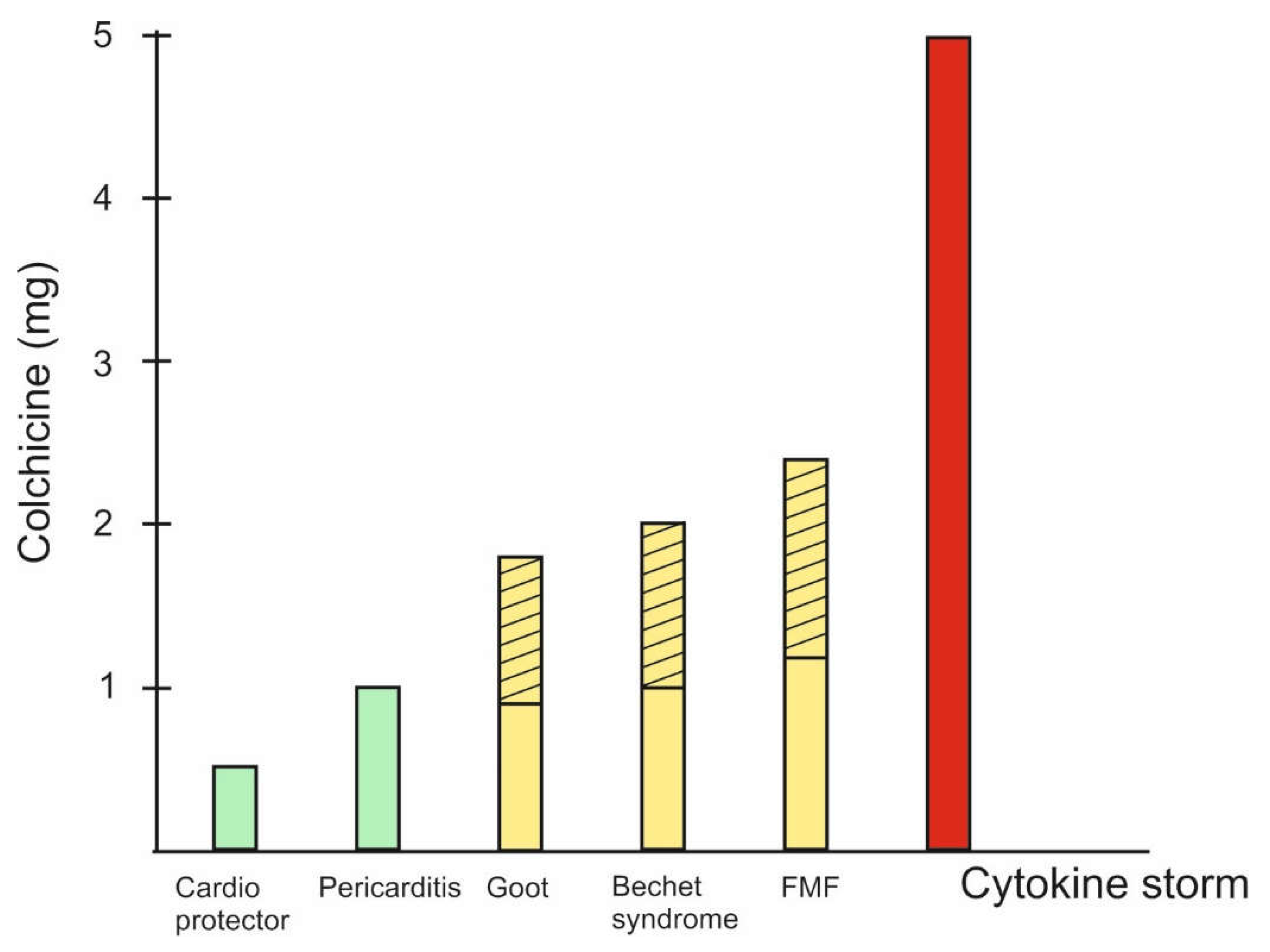

The natural product colchicine is a typical example of Paracelsus' classic rule that the difference between poison and medicine is the dose. Different doses of colchicine are optimal for different pathological conditions (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Doses of colchicine in different pathological situations. 1. For cardio protection are recommended colchicine doses of 0.5/0.6mg daily for 6 months [

19]; for stroke prevention 0.5-1mg once daily [

64] and vascular inflammation prevention 0.5mg once daily for 60 months [

65]. 2. Acute coronary syndrome, coronary artery disease, pericarditis, atrial fibrillation - 0.5mg twice daily for 1month to 1 year or 0.5mg once daily for a median of 3 years [

65]. 3. Behçet’s syndrome - 1-2mg daily for 3 months [

65]. 4. Acut Gout - 1.8mg total [

33]. 5. The highest recommended doses for FMF are up to 2.4mg. Interestingly, in cases where there is no effect, they are recommended “the maximum tolerated dose ” [

66]. 6. COVID-19 - up to 5mg loading dose [

24].

Figure 2.

Doses of colchicine in different pathological situations. 1. For cardio protection are recommended colchicine doses of 0.5/0.6mg daily for 6 months [

19]; for stroke prevention 0.5-1mg once daily [

64] and vascular inflammation prevention 0.5mg once daily for 60 months [

65]. 2. Acute coronary syndrome, coronary artery disease, pericarditis, atrial fibrillation - 0.5mg twice daily for 1month to 1 year or 0.5mg once daily for a median of 3 years [

65]. 3. Behçet’s syndrome - 1-2mg daily for 3 months [

65]. 4. Acut Gout - 1.8mg total [

33]. 5. The highest recommended doses for FMF are up to 2.4mg. Interestingly, in cases where there is no effect, they are recommended “the maximum tolerated dose ” [

66]. 6. COVID-19 - up to 5mg loading dose [

24].

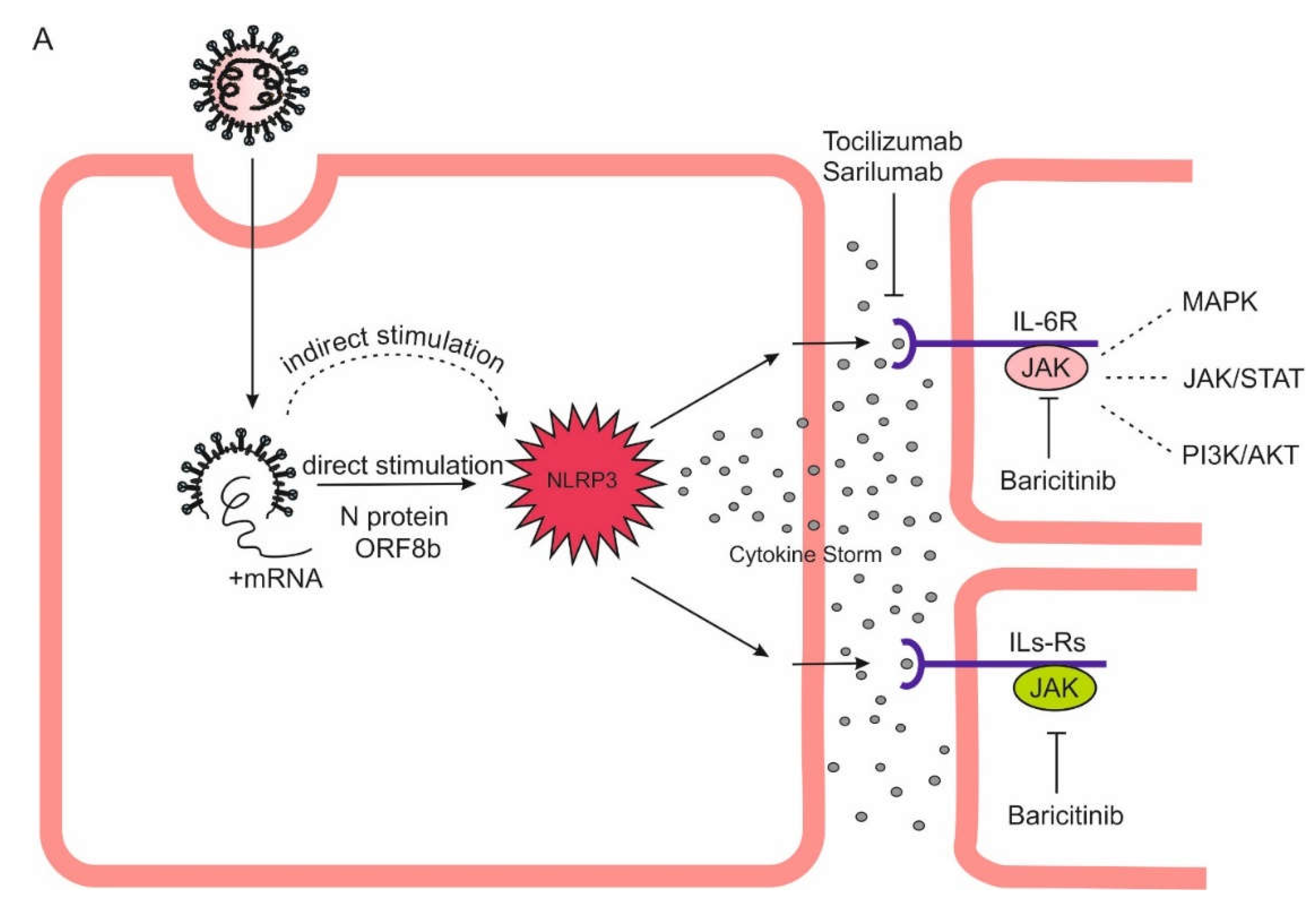

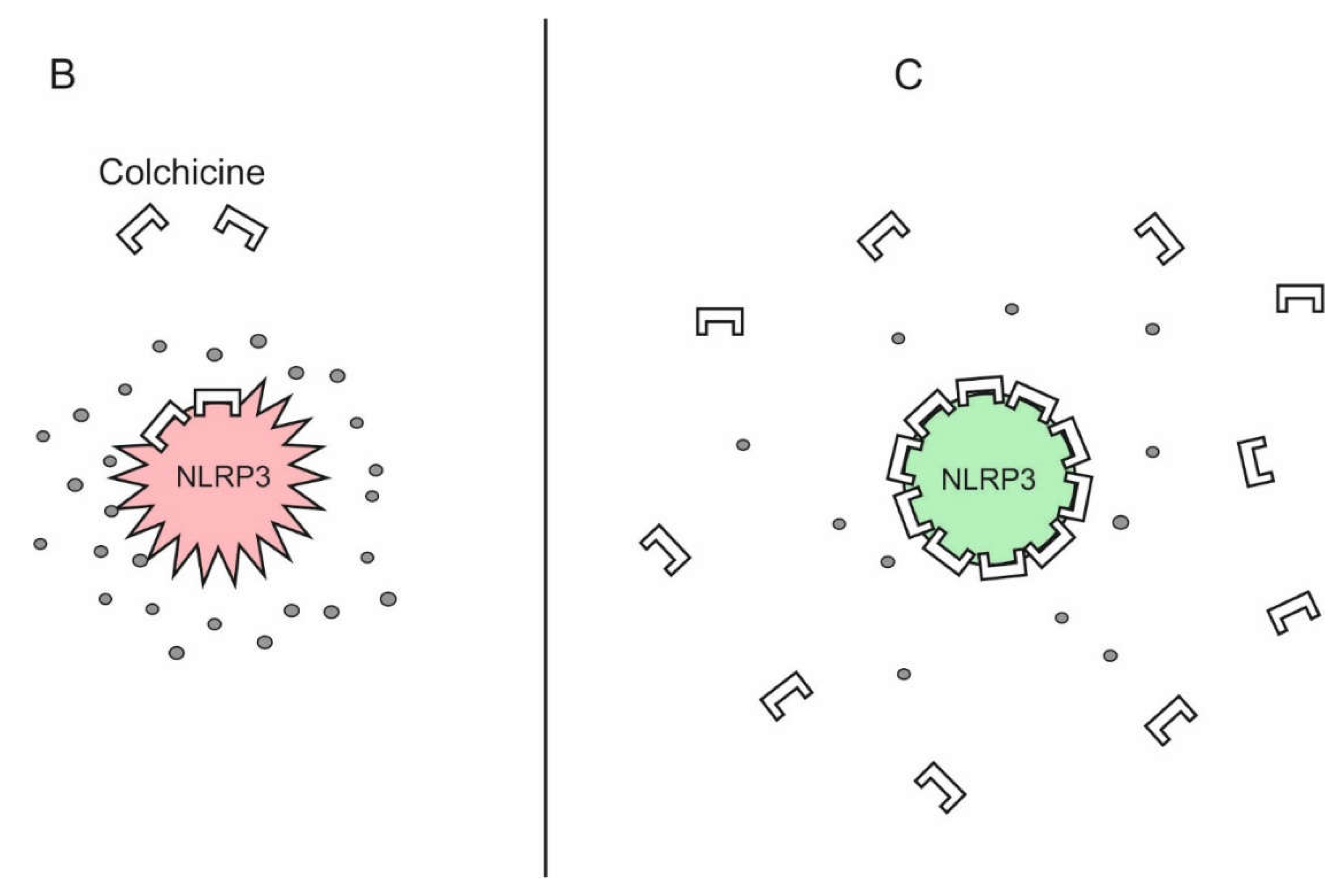

Figure 3.

Theoretical basis of high-dose colchicine treatment in COVID-19. Mortality in COVID-19 is due to a cytokine storm triggered directly and indirectly by SARS-CoV-2, which hyperactivates the NLRP3 inflammasome in myeloid cells. It is inhibited by micromolar concentrations of colchicine. As colchicine has remarkable ability to accumulate intensively in leukocytes, its increasing doses can lead to such an accumulation in macrophages, neutrophils and monocytes that is sufficient to inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome and, accordingly, the cytokine storm. A Direct and indirect stimulation of NLRP3 inflammasome by SARS-CoV-2 can leads to its hyperactivation, cytokine storm, multiorgan falure and death. B Low doses of colchicine are not sufficient for NLRP3 inflammasome/cytokine storm inhibition. C High doses of colchicine are capable to inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome interrupting the cytokine storm.

Figure 3.

Theoretical basis of high-dose colchicine treatment in COVID-19. Mortality in COVID-19 is due to a cytokine storm triggered directly and indirectly by SARS-CoV-2, which hyperactivates the NLRP3 inflammasome in myeloid cells. It is inhibited by micromolar concentrations of colchicine. As colchicine has remarkable ability to accumulate intensively in leukocytes, its increasing doses can lead to such an accumulation in macrophages, neutrophils and monocytes that is sufficient to inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome and, accordingly, the cytokine storm. A Direct and indirect stimulation of NLRP3 inflammasome by SARS-CoV-2 can leads to its hyperactivation, cytokine storm, multiorgan falure and death. B Low doses of colchicine are not sufficient for NLRP3 inflammasome/cytokine storm inhibition. C High doses of colchicine are capable to inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome interrupting the cytokine storm.

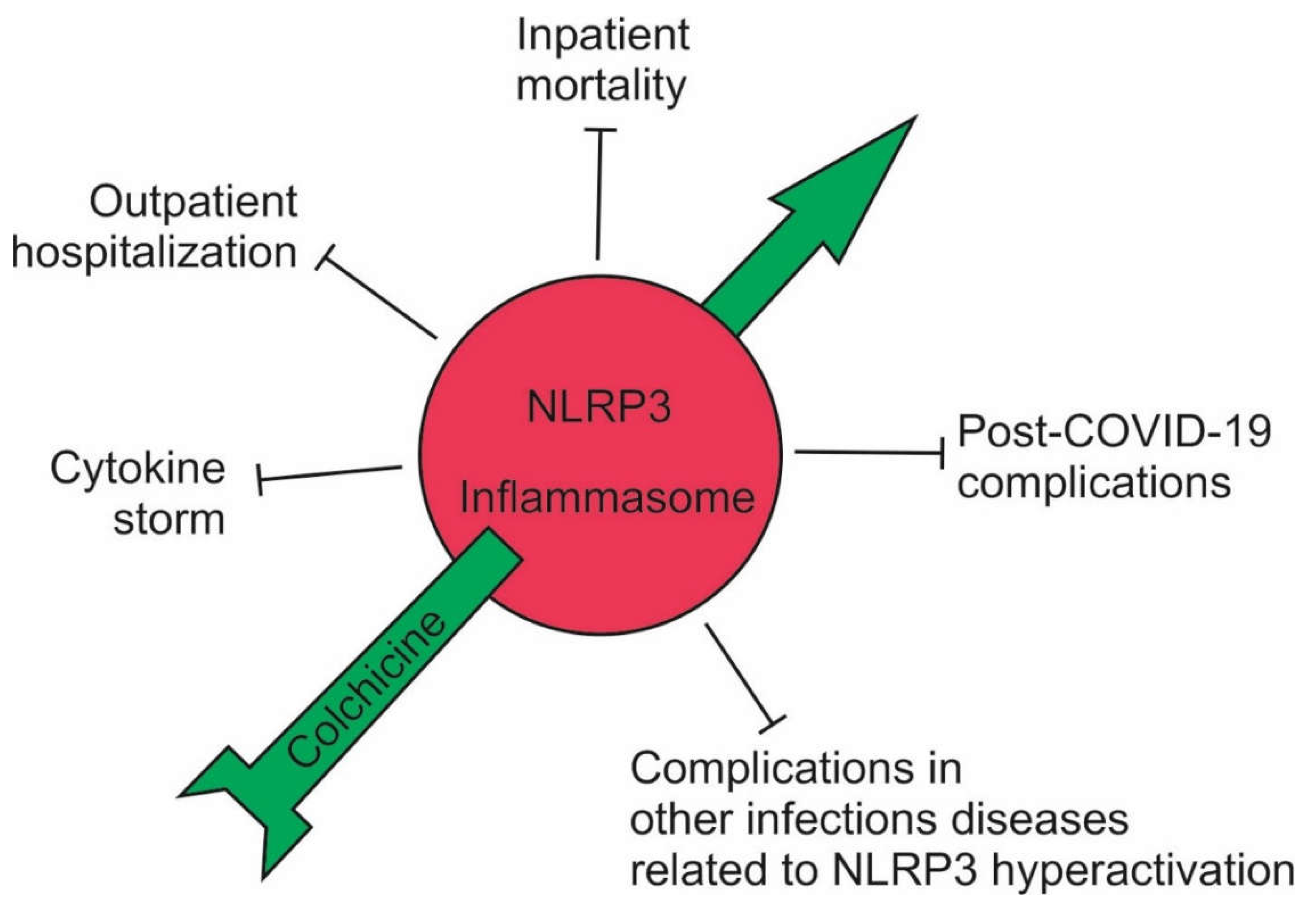

Figure 4.

Effect of high-dose colchicine on the course of COVID-19. High-dose of colchicine inhibited the NLRP3 inflammasome and, accordingly, the cytokine storm; outpatients did not develop complications and avoided hospitalization; the mortality of hospitalized patients decreased up to 7-fold; and post-COVID-19 symptoms decreased sharply. High-dose of colchicine should also be effective in other infectious conditions associated with hyperactivation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Figure 4.

Effect of high-dose colchicine on the course of COVID-19. High-dose of colchicine inhibited the NLRP3 inflammasome and, accordingly, the cytokine storm; outpatients did not develop complications and avoided hospitalization; the mortality of hospitalized patients decreased up to 7-fold; and post-COVID-19 symptoms decreased sharply. High-dose of colchicine should also be effective in other infectious conditions associated with hyperactivation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

5. Why Give Higher Doses of Colchicine to Treat Severe COVID-19?

Myeloid cells (granulocytes, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells) are a major source of dysregulated inflammation in COVID-19. The hyperactivation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and the subsequent cytokine storm take place precisely inside them. Expressed in myeloid cells, the NLRP3 inflammasome is a component of the innate immune system and is involved in the activation of many inflammatory processes [

30], including the generation of the COVID-19 cytokine storm. NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition has been assessed at colchicine concentrations 10- to 100-fold higher than those achieved in serum [

31].

God's gift of colchicine is its remarkable ability to accumulate intensively in leukocytes, where the cytokine storm is generated [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Colchicine reaches much higher concentrations within leukocytes than in plasma and persists there for several days after ingestion [

35]. Whereas the peak plasma concentration after single oral dosing of 0.6 colchicine is approximately 3 nmol/L, it has been shown to accumulate in a saturable manner in neutrophils 40 to 200 nmol/L [

36]. One possible explanation for this phenomenon in the neutrophils is their low expression of

ABCB1 (

ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily B Member 1) drug transporter gene [

32]. Colchicine concentrations in neutrophils are 3 fold higher that that in lymphocytes, probably due to the reduced expression of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) which function is to remove colchicine from cells [

37].

Thus, it is logical to expect that by raising the doses of colchicine within acceptable limits, a level of its concentration sufficient to inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome in leukocytes can be reached. Increasing doses of colchicine can lead to such an accumulation in macrophages, neutrophils and monocytes that is sufficient to inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome and, accordingly, the cytokine storm.

6. In Search of the Optimal Dose of Colchicine to Inhibit the NLRP3 Inflammasome

Colchicine Toxicity

Colchicine is well known for its narrow therapeutic index and no clear-cut line between non-toxic, toxic and lethal doses. Finkelstein et al. conducted a large-scale study spanning 44 years in search of the minimal lethal dose of colchicine and concluded that ‘the lowest reported lethal doses of oral colchicine have ranged from 7 to 26mg’ [

38]. This opinion has been accepted as dogma and is being quoted continuously [

39].

However, our analysis showed that the deaths reported in the literature with colchicine doses of 7–7.5mg are due to drug interactions and to a large extent, this also applies to the described lethal doses of colchicine of 15–18mg. We proposed that the classical sentence of Finkelstein et al., 2010 should be recast as ‘The lowest reported lethal doses of oral colchicine has ranged from 15 to 26 mg’ [

39]. We consider that doses of colchicine below 0.1 mg/kg are completely safe, and those between 0.1 and 0.2 mg/kg may lead to sertain toxicity side effects in some cases, but not to death [

39].

More recent examples can be cited as a confirmation of this. In the clinical reports published between 2001 and 2021 and assessing colchicine application and toxicity in adults, no cases can be found refuting our suggestion of a lowest lethal dose of colchicine [

40]. The deceased 56-year-old man after taking 12 mg (0.17 mg/kg) of colchicine had a medical history of gout and poor kidney function due to chronic kidney disease. Furthermore, he was late diagnosed and admitted to hospital after drinking alcohol [

41]. In another deadly case a 33-year-old woman was admitted after ingesting 20 mg (0.33mg/kg) colchicine combined with atorvastatin, ibuprofen, diclofenac, and furosemide [

42]. Statins are inhibitors of the cytochrome P-450 (CYP) 3A4 isozyme and P-glycoprotein so that taken together with colchicine, they represent a clinically significant interaction.

A number of cases of colchicine overdose in the range of 15-24 mg with complete recovery have been described: An 18-year-old female had ingested 18mg (~0.4 mg/kg) of colchicine in a suicide attempt [

43]; a 48-year-old Australian Caucasian male had ingested more than >10mg colchicine [

44]; a 51-year-old male with medical history of depression, high blood pressure, and gout treated with colchicine had ingested 17mg of

Colchimax [

45]; a 15-year-old girl after the ingestion of 24mg of colchicine [

46]; a 38-year-old male had ingested 15mg (0.2mg/kg) [

47]. All these patients showed varying degrees of toxicity, and our opinion that, within these limits, deaths occur only if drug interactions or renal and/or hepatic damage are present, is confirmed [

39]. Two recent retrospective studies confirm our observations [

48,

49]. In a series of 21 cases of colchicine poisoning, a retrospective cross sectional study demonstreted that lowest lethal dose was 20mg in an accidental intake in a 10-year-old boy with G6PD deficiency. The other two non-survivors had ingested 38, and 40mg of colchicine [

48].

Stamp et al., 2023 demonstrated 48 cases of colchicine poising, some of which are commented above and in [

49]. Death rarely occurs at doses up to 25mg colchicine unless other aggravating factors are present, most commonly drug interactions and/or kidney or liver damage. A typical case is the death of a 39-year-old female with bipolar affective disorder, hypothyroidism, reflux disease, multiple suicide attempts involving multidrug overdose, and illicit drug use who ingested 25mg (0.28mg/kg) colchicine togheder with 50 tablets of indomethacin (1.25g), and 10 tablets of zopiclone (75mg) as well as topiramate, valproic acid, olanzapine, lorazepam, levothyroxine, oxycodone, furosemide, omeprazole (unknown timing and doses) prior to admission [

50].

Colchicine is a safe and well-tolerated drug which increases the rate of diarrhoea and gastrointestinal adverse events but does not increase the rate of liver, sensory, muscle, infectious or haematology adverse events or death [

51].

7. Our Experience in Treating COVID-19 with a High-Dose Colchicine

In March 2020 we started the administration of higher doses of colchicine due to the fact that we did not get satisfactory results with the low doses of the drug. Our assumption was that safe increase in colchicine doses to reach micromolar concentrations in leukocytes will result in NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition.

The inhibitory effect of colchicine on cytokine storm occurs at doses, such as [0.5mg per 10kg body weight]-0.5mg, but not more than 5mg loading dose. This makes 0.04–0.045mg/colchicine/kg [

52,

53,

54]. We consider that doses of colchicine below 0.1 mg/kg are completely safe, and those between 0.1 and 0.2mg/kg may lead to toxicity side effects in some cases, but not to death [

39].

8. Case Series of Severe or Critical COVID-19 Dramatically Affected by High-Dose Colchicine

We have published series of cases demonstrating the life-saving effect of colchicine. For exemple, a patient in whom the chest computed tomography demonstrated that only about 10% of the lung was not affected by severe bilateral pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome, recovered after treatment with a high-dose colchicine [

54].

Obese patients with a BMI over 40 represent perhaps the most at-risk group for COVID-19 complications. A 120 kg patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and gout was hospitalized on the third day of the COVID-19 diagnosis in relatively good general condition (oxygen saturation is 89%). Despite the started standard therapy, the patient continued to deteriorate (oxygen saturation is 74%) and on the eighth day colchicine was included at a dose of 6mg. The patient quickly recovered [

55]. Three high-risk patients with a BMI over 50 and 60 also responded dramatically to 5 mg of colchicine [

56]. These are typical cases of the life-saving effect of high doses of colchicine in high-risk COVID-19 patients.

It is interesting to note that accidentally taken single overdose of colchicine (15mg or 12.5mg) is sufficient for the complete recovery of patients, including the eradication of pericardial effusion [

57].

9. In 785 Inpatients Treated with Increasing Doses of Colchicine, Mortality Fell between 2 and 7 Times

In the already described 452 inpatients, higher colchicine doses reduced the mortality about 5 fold [

53]. In other 333 inpatients treated with different, but high colchicine doses, a clear reduction in the mortality between 2- and 7-fold has emerged with increasing doses of colchicine. Thus, colchicine loading doses of 4 mg are more effective than those with 2 mg [

58]. Despite higher than the so-called “standard doses” of colchicine, our doses are completely safe [

39].

Our data, including also a large number of COVID-19 outpatients, showed that nearly 100% of the patients treated with this therapeutic regimen escaped hospitalization. In addition, post-covid symptoms in those treated with colchicine were significantly less. These results have been announced in several national and international conferences and are being processed for publication [

24].

10. Discussion

How the Opportunity to Save Millions of Human Lives was Missed Because One Point Instead of a Comma Was Used

Given the multiple anti-inflammatory and anti-Covid-19 effects of colchicine

in vitro, over 50 observational studies and randomized clinical trials, small randomized non-controlled trials and retrospective cohort studies were initiated to test its healing effect

in vivo, leading to conflicting results [

24,

59,

60].

The Randomised Evaluation of COVid-19 thERapY (RECOVERY) trial, launched on 23 March 2020 is a large-scale, randomized, controlled trial, which claims to be the most credible study on the effect of various proposed drugs to treat COVID-19. The RECOVERY Trial is presented as “an exceptional study that is leading the global fight against COVID-19”, that “has saved hundreds of thousands – if not millions – of lives worldwide”. It encompasses 48941 participants and 187 active sites [

61]. WHO automatically complies with the conclusions of these clinical trials and gives ”

Strong recommendation against” the use of colchicine for COVID-19 treatment (

https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-2019-nCoV-therapeutics-2022.4/).

The analysis based on 2178 reported deaths among 11,162 randomised patients concluded that ”To date there has been no convincing evidence of the effect of colchicine on clinical outcomes in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19” [

62].

Very important - only low doses of colchicine were used!

The co-Chief Investigator sir

Peter Horby, said: ‘This is the largest ever trial of colchicine... Whilst we are disappointed that the overall result is negative…’ [

61]. Misleading! Correct: ‘This is the largest ever trial of colchicine

with low doses…

The other co-Chief Investigator for the RECOVERY Trial Sir

Martin Landray said: ‘So, it is disappointing that colchicine, which is widely used to treat gout and other inflammatory conditions, has no effect in these patients’ [

61].

This conclusion is misleading. The correct conclusion should sound like this: ‘So, it is disappointing that colchicine, which is widely used to treat gout and other inflammatory conditions, has no effect in these patients, at low doses’. Here's how one ”point” instead of ”comma” doomed the colchicine treatment of COVID-19 to failure.

11. Conclusions

A number of questions remain without answers. The RECOVERY Trial co-Chief Investigators, the Lancet reviewers, and the Lancet editors should answer the following questions: Why is the Paracelsus' rule not being followed and attempts to prove an effect at low doses of colchicine continue to this day? Why were only colchicine doses recommended for gout given? COVID-19 is not gout! Why the study of Terkeltaub et al, 2010 with low and high doses of colchicine has not been repeated? [

33]. Why do attempts to disprove Einstein that “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results” continue? Which is preferable - alive with diarrhea for a few days or dead without diarrhea?

Thus, the opportunity to save millions of human lives was missed!

12. Future Directions

A large number of viruses can overactivate the NLRP3 inflammasome [

63]. For exemple, according to World Health Organization (WHO) the seasonal influenza causes 3–5 million cases of severe illnesses and between 290,000 and 650,000 deaths per year globally, with 36% of these deaths taking place in low- and middle income countries (Influenza (Seasonal). World Health Organization. 3.10.2023.

https://www.who.int).

We are convinced that higher colchicine doses would be useful in these cases as well [

56]. We set out to test this hypothesis with success.

Acknowledgments

This study is financed by the European Union-NextGenerationEU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project № BG-RRP-2.004-0004-C01.

References

- Slobodnick, A.; Shah, B.; Pillinger, M.H.; Krasnokutsky, S. Colchicine: old and new. Am. J. Med. 2015, 128, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgeb, B.; Kornreich, D.; McGuinn, K.; Okon, L.; Brownell, I.; Sackett, D.L. Colchicine: an ancient drug with novel applications. BJD, 2018, 178, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, W.J. The Search for Human Chromosomes: A History of Discovery. Springer. 2015, p. 88. ISBN 978-3-319-26336-6.

- Nerlekar, N.; Beale, A.; Harper, R.W. Colchicine - a short history of an ancient drug. MJA. 2014, 201, 687–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartung, E.F. History of the use of colchicum and related medicaments in gout; with suggestions for further research. ARD, 1954, 13, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, P.S.; Caventou, J.B. . Examen chimique des plusieurs végétaux de la famille des colchicées, et du principe actif qu'ils renferment. (Cévadille (veratrum sabadilla); hellébore blanc (veratrum album); colchique commun (colchicum autumnale). Annal. Chim. Phys., 1820, 14, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, P.L. Ueber einige neue giftige organische Alkalien. Annalen der Pharmacie (in German). 1833, 7, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddy, E.; Mallen, C.D.; Doherty, M. Gout. BMJ, 2013, 347, f5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeman, J.I. Revolutions in Chemistry: Assessment of Six 20th Century Candidates (The Instrumental Revolution; Hückel Molecular Orbital Theory; Hückel's 4n+2 Rule; the Woodward-Hoffmann Rules; Quantum Chemistry; and Retrosynthetic Analysis). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 3, 2378–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roubille, F.; Kritikou, E.; Busseuil, D.; Barrere-Lemaire, S.; Tardif, J.C. Colchicine: An old wine in a new bottle? Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2013, 12, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.M. , Qadir, S., Aslam, H.M., Qadir, M.A., Updated Treatment for Calcium Pyrophosphate Deposition Disease. Cureus. 2019, 11, e3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surma, S.; Basiak, M.; Romańczyk, M.; Filipiak, K.J.; Okopień, B. Colchicine - From rheumatology to the new kid on the block: Coronary syndromes and COVID-19. Cardiol. J. 2023, 30, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konda, C.; Rao, A.G. Colchicine in dermatology. IJDVL 2010, 76, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardana, K.; Sinha, S.; Sachdeva, S. Colchicine in Dermatology: Rediscovering an Old Drug with Novel Uses. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2020, 11, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimmino, G.; Conte, S.; Morello, A.; Pellegrino, G.; Marra, L.; Calì, G.; Golino, P.; Cirillo, P. Colchicine inhibits the prothrombotic effects of oxLDL in human endothelial cells. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2021, 137, 106822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, B.; Allen, N.; Harchandani, B.; Pillinger, M.; Katz, Stuart. ; Sedlis, S. P.; Echagarruga, C.; Krasnokutsky Samuels, S.; Morina, P.; Singh. P.; Karotkin, L.; Berger, J.S. Effect of Colchicine on Platelet-Platelet and Platelet-Leukocyte Interactions: a Pilot Study in Healthy Subjects. Inflammationm 2016, 39, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, B.; Meng, X.; Wang, A. : Niu, S.: Xie, X.: Jing, J.: Li, H.: Chang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Effect of different doses of colchicine on high sensitivity C-reactive protein in patients with acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 178, 106288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsivgoulis, G.; Katsanos, A.H.; Giannopoulos, G.; Panagopoulou, V.; Jatuzis, D.; Lemmens, R.; Deftereos, S.; Kelly, P.J. The Role of Colchicine in the Prevention of Cerebrovascular Ischemia. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.; Fuster, V.; Ridker, P.M. Low-Dose Colchicine for Secondary Prevention of Coronary Artery Disease: JACC Review Topic of the Week. JACC. 2023, 82, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.C.; Chang, S.J.; Hsieh, M.C. Colchicine significantly reduces incident cancer in gout male patients: a 12-year cohort study. Medicine. 2015, 94, e1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z-Y. ; Kuo, C-H.; Wu, D-C.; Chuang, W-L. Anticancer effects of clinically acceptable colchicine concentrations on human gastric cancer cell lines. The Kaohsiung. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 32, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; An, H−J. ; Yeo, H.J.; Choi, S.; Oh, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.M.; Choi, J.; Lee, S. Colchicine as a novel drug for the treatment of osteosarcoma through drug repositioning based on an FDA drug library. Front. oncol. 2022, 12, 893951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryono, S.; Rohman, M.S.; Widjajanto, E.; Prayitnaningsih, S.; Wihastuti, T.A.; Oktaviono, Y.H. Effect of Colchicine in reducing MMP-9, NOX2, and TGF- β1 after myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitev, V. Comparison of treatment of Covid-19 with inhaled bromhexine, higher doses of colchicine and hymecromone with WHO-recommended paxlovide, mornupiravir, remdesivir, anti-IL-6 receptor antibodies and baricitinib. Pharmacia. 2023, 70, 1177–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, J. , Ryan, J., McCarthy, G., 2015. Colchicine: New Insights to an Old Drug. American Journal of Therapeutics. [CrossRef]

- Michaleas, S.N.; Laios, K.; Tsoucalas, G.; Androutsos, G. Theophrastus Bombastus Von Hohenheim (Paracelsus) (1493-1541): The eminent physician and pioneer of toxicology. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borzelleca, J.F. Paracelsus: Herald of Modern Toxicology. Toxicol. Sci. 2000, 53, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsatsakis, A.M.; Vassilopoulou, L.; Kovatsi, L.; Tsitsimpikou, C.; Karamanou, M.; Leon, G.; Liesivuori, J.; Hayes, A.W.; Spandidos, D.A. The dose response principle from philosophy to modern toxicology: the impact of ancient philosophy and medicine in modern toxicology science. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deichmann, W.B.; Henschler, D.; Holmstedt, B.; Keil, G. What is there that is not poison? A study of the Third Defense by Paracelsus. Arch. Toxicol. 1986, 58, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariathasan, S.; Newton, K.; Monack, D. M.; Vucic, D.; French, D. M.; Lee, W.P.; Roose-Girma, M.; Erickson, S.; Dixit V., M. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature. 2004, 430, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronstein, B.N.; Sunkureddi, P. Practical reports on rheumatic & musculoskeletal diseases: Mechanistic aspects of inflammation and clinical management of inflammation in acute gouty arthritis. JCR. 2013, 19, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.Y.; Hui, L.L.Y.; Kraus, V.B. Colchicine—update on mechanisms of action and therapeutic uses. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015, 45, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkeltaub, R.A.; Furst, D.E.; Bennett, K.; Kook. K.A.; Crockett, R.S.; Davis, M.W. High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early acute gout flare: Twenty-four-hour outcome of the first multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-comparison colchicine study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortmann, R. L.; MacDonald, P. A.; Hunt, B.; Jackson, R. L. Effect of prophylaxis on gout flares after the initiation of urate-lowering therapy: analysis of data from three phase III trials. Clin. Ther. 2010, 32, 2386–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, J.; Sirois, M.G. , Rhéaume, E.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Clavet-Lanthier, M-É.; Brand, G.; Mihalache-Avram, T.; Théberge-Julien, G.; Charpentier, D.; Rhainds, D.; Neagoe, P.E.; Tardif, J.C. Colchicine reduces lung injury in experimental acute respiratory distress syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2020, 15, e0242318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappey, O.; Niel, E.; Dervichian, M.; Wautier, J.L.; Scherrmann, J.M.; Cattan, D. Colchicine concentration in leukocytes of patients with familial Mediterranean fever. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1994, 38, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Chetrit, E.; Levy, M. Does the lack of the P-glycoprotein efflux pump in neutrophils explain the efficacy of colchicine in familial Mediterranean fever and other inflammatory diseases? Med. Hypotheses 1998, 51, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, Y.; Aks, S.E.; Hutson, J.R.; Juurlink, D. N.; Nguyen, P.; Dubnov-Raz, G.; Pollak, U.; Koren, G.; Bentur, Y. Colchicine poisoning: the dark side of an ancient drug. Clin. Toxicol., 2010, 48, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitev, V. What is the lowest lethal dose of colchicine? Biotechnol. Equip. 2023, 37, 2288240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Z. Progress in the management of acute colchicine poisoning in adults. IEM. 2022, 17, 2069–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Zhao, J., Li. Z.; Zhao, H.; Lu, A. Clinical outcomes after colchicine overdose: A case report. Medicine. 2019, 98, e16580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, V.; Huberlant, V.; Vincent, M. F.; Bonbled, F.; Hantson, P. Multiple organ failure after an overdose of less than 0.4 mg/kg of colchicine: role of coingestants and drugs during intensive care management. Clin. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, S.; Snyder, D.; Azran, C.; Zolotarsky, V.; Dahan, A. Severe hypertriglyceridemia and colchicine intoxication following suicide attempt. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017, 11, 3321–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang,W-H. ; Hsu, C-W.; Yu, C-C. Colchicine Overdose-Induced Acute Renal Failure and Electrolyte Imbalance. Ren. Fail. 2007, 29, 367–370. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouffroy, R.; Lamhaut, L.; Petre Soldan, M.; Vivien, B.; Philippe, P.; An, K.; Carli, P. A new approach for early onset cardiogenic shock in acute colchicine overdose: place of early extracorporeal life support (ECLS)? Intensive Care Med. 2013, 39, 1163–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, S. S.; Kramlinger, K. G.; McMichan, J. C.; Mohr, D. N. Acute toxicity after excessive ingestion of colchicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 1983, 58, 528–532. [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki, A.; Iranami, H.; Nishikawa, K. Severe colchicine intoxication after self-administration of colchicine concomitantly with loxoprofen. J. Anesth. 2013, 27, 483–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, M.; Alizadeh, R.; Hassanian-Moghaddam, H.; Zamani, N.; Kargar, A.; Shadnia, S. Clinical Manifestations and Outcomes of Colchicine Poisoning Cases; a Cross Sectional Study. AAE. 2020, 8:e53.

- Stamp, L.; Horsley, C.; Te Karu, L.; Dalbeth, N.; Barclay, M. Colchicine: the good, the bad, the ugly and how to minimize the risks. Rheumatology 2023, 63, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, A.; Tung, D.; Truong, C.; Lapinsky, S.; Burry, L. Colchicine overdose with coingestion of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. CJEM. 2014, 16, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S.; Yang, K.C.K.; Atkins, K.; Dalbeth, N.; Robinson, P.C. Adverse events during oral colchicine use: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther, 2020, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitev, V.; Mondeshki, T. Treatment of COVID-19 with colchicine and inhaled bromhexine. Medizina i Sport, -2.

- Mitev, V.; Mondeshki, T.; Marinov, K.; Bilukov, R. Colchicine, bromhexine, and hymecromone as part of COVID19 treatment - cold, warm, hot. Current Overview on Disease and Health Research. Khan BA (ed): BP International, London, UK, 2023, 10, 106–113. [CrossRef]

- Mondeshki, T.; Bilyukov, R.; Tomov, T.; Mihaylov, M.; Mitev, V. Complete, rapid resolution of severe bilateral pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome in a COVID-19 patient: role for a unique therapeutic combination of inhalations with bromhexine, higher doses of colchicine, and hymecromone. Cureus. 2022, 14, e30269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilov, A.; Palaveev, K.; Mitev, V. High Doses of Colchicine Act As “Silver Bullets” Against Severe COVID-19. Cureus. 2024, 16, e54441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondeshki, T.; Mitev, V. High-Dose Colchicine: Key Factor in the Treatment of Morbidly Obese COVID-19 Patients. Cureus. 2024, 16, e58164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondeshki, T.; Bilyukov, R.; Mitev, V. Effect of an Accidental Colchicine Overdose in a COVID-19 Inpatient With Bilateral Pneumonia and Pericardial Effusion. Cureus. 2023, 15, e35909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiholov, R.; Lilov, A.; Georgieva, G.; Palaveev, K.; Tashkov, K.; Mitev, V. 2024. Effect of increasing doses of colchicine on the treatment of 333 COVID-19 inpatients. Immun Inflamm Disease, 2024; e1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajewska, A.; Fischer, A-L. ; Piechotta, V.; Mueller, A.; Metzendorf, M-I.; Becker, M.; Dorando, E.; Pacheco, R.L.; Martimbianco, A.L.C.; Riera, R.; Skoetz, N.; Stegemann, M. Colchicine for the treatment of COVID-19. CDSR 2021, 10, CD015045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheema, H.A.; Jafar, U.; Shahid, A.; Masood, W.; Usman, M.; Hermis, A. H.; Naseem, M. A.; Sahra, S.; Sah, R.; Lee, K. Y. Colchicine for the treatment of patients with COVID-19: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ open. 2024, 14, e074373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RECOVERY trial closes recruitment to colchicine treatment for patients hospitalised with COVID-19. 2021. https://www.recoverytrial.

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Colchicine in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021, 9, 1419–1426. [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Jin, M.; Chen, H.; Wu, Z.; Yuan, L.; Liang, S.; Wang, X.; Memon, F.U.; Eldemery, F.; Si, H.; Ou, C. Inflammasome activation by viral infection: mechanisms of activation and regulation. Front Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1247377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, W.; Lobo, M.; Molinero, G.; Masson, G.; Lavalle-Cobo, A. Role of Colchicine in Stroke Prevention: An Updated Meta-Analysis. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis.. 2020, 29, 104756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatza, E.; Ismailos, G.; Karalis, V. Colchicine for the treatment of COVID-19 patients: efficacy, safety, and model informed dosage regimens. Xenobiotica. 2021, 51, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozen, S.; Demirkaya, E.; Erer, B.; Livneh, A.; Ben-Chetrit, E.; Giancane, G.; Ozdogan, H.; Abu, I.; Gattorno, M.; Hawkins, P.N.; Yuce, S.; Kallinich, T.; Bilginer, Y.; Kastner, D.; Carmona, L. Eular recommendations for the management of familial Mediterranean fever. ARD, 2016, 75, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).