1. Introduction

Software vulnerabilities refer to defects in programming codes or applications that could be exploited by attackers. These vulnerabilities allow attackers to gain access to or damage a computer system. It is apparent that they need to be addressed. The importance of this research is to evaluate and improve tools; specifically, AIBugHunter, as it is used to address attacks. AIBughunter is a tool that scans C / C++ programs, finds code that is vulnerable or susceptible to attack, identifies the CWE (Common Weakness Enumeration) type of vulnerability, estimates the CVSS (Common Vulnerability Scoring System) vulnerable severity score, explains the vulnerability, and suggests the proper repair. It was developed by the ASWM research group as reported by Fu et al., who stated that most vulnerabilities are found in C compared to other programming languages [

1]. Although there are many Integrated Development Environments (IDEs), the tool can be found and installed in Visual Studio Code as an extension.

Common Weakness Enumeration, or CWE, is a list of common software and hardware weaknesses that address security concerns. A weakness is a condition in a computer system that includes software, hardware, etc. that could cause a vulnerability and should not be used [

2]. As related to software weaknesses, developers cause them when writing programs in specific ways that could be exploited. When creating a CWE, a unique number is assigned to it, referred to as CWE-ID. A created CWE also has a Name that describes the weakness, Summary of the weakness, Extended Description, Modes of Introduction, Potential Mitigations, Common Consequences, Applicable Platforms, Demonstrative Examples, Observed Examples, Relationships, and References. CWE is a way software developers can use to become aware of and eliminate vulnerabilities or security flaws in their programs. In general, it describes the weakness and provides guidance on how it can be avoided. If a vulnerable function is found, AIBugHunter predicts the CWE-ID, the CWE-Type, and the severity of the vulnerable function via the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) severity score.

CVSS serves as an industry standard for assessing the impact of vulnerabilities in computer systems. It is beneficial as it offers insights and prompts the necessary responses. The scoring system extends from 0 to 10, where a score of 10 indicates extreme severity that requires urgent action. The scores are categorized. CVSS v3.x ratings have a severity score of 0 which means no severity score, 0.1 to 3.9 which means a low severity score, 4 to 6.9 -medium, 7 to 8.9 - high and 9 to 10 which is critical. More information is available at the National Vulnerabilities Database (NVD) website [

3].

On the back-end, AIBugHunter integrates LineVul and VulRepair to locate and repair vulnerabilities. LineVul is a transformer-based approach that predicts vulnerable functions and identifies vulnerable lines within programs written in C/C++ code. It addresses the limitations of Li et al. IVDetect [

4]. IVDetect is an AI vulnerability detector that uses an Intelligence Assistant and outperforms 2021 deep learning models [

5].

VulRepair, also integrated into AIBugHunter, relies on a T5 architecture. T5 is a natural language processing (NLP) model that was developed by Google in 2019 [

6]. T5 is short for Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer with layers that consists of an encoder and decoder neural network layers. The encoder is used for the input sequence while the decoder is used for the output sequence. VulRepair’s T5 makes use of both Natural and Programming Languages and Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) to outperform other existing models such as VRepair and CodeBERT. It is used to repair the vulnerability of the function, or as they say, to suggest repairs to vulnerable lines [

7].

Perfect Prediction refers to an outcome that is 100% accurate and not a random guess. Percent Perfect Prediction provides the percentage of correct outcomes. Regarding VulRepair, it is the percentage in which a correct repair is matched, or perfectly predicted, to a vulnerable function.

In their study, Fu et al. showed how VulRepair, with a 44% perfect prediction of fixing vulnerabilities, outperforms CodeBERT, at 31%, and VRepair, at 23%. They further demonstrate the importance of using pre-training, with natural and programming languages, and how a subword tokenizer is better than the word-level tokenizer in the VulRepair model.

Fu et al. used the Big-Vul dataset, which is a C/C++ code vulnerability dataset to evaluate vulnerable functions. The data set plays an important role in vulnerability research and was introduced by Fan et al. [

8]. It contains 3,754 code vulnerabilities and includes CVE Ids and CVE severity scores. Its use applies to file, function, and line fixes. More information is available on GitHub at [

9]. Fu et al. also used the CVEfixes dataset that is used in software security research as it is used for vulnerability prediction, classification, severity prediction, and automated vulnerability repair as provided by Bhandari et al. [

10]. The initial release of CVEfixes contains 5495 vulnerability-fixing commits. VulRepair is evaluated on both Big-Vul and CVEfixes, as they contain vulnerability repairs as described by the CWE types, or 8,482 vulnerability repairs with over 180 various CWE types.

Fu et al. report that VulRepair performs best when vulnerable functions have fewer than 500 tokens and fewer than 20 repair tokens. The T5 architecture is limited to 512 tokens, and anything more is truncated. VulRepair also performs best when vulnerable repairs have less than 10 tokens. Fu et al. offer settings to replicate their experiment and prompt researchers to find ways to handle larger functions as well as larger repair tokens. They also mention threats to their validity. A threat is hyperparameter optimization, that is, finding the best hyperparameters that provide the best results. Fu et al. note that finding the best hyperparameters is expensive. We also find that its process is time-consuming, since the models take hours to train and test. Furthermore, we claim that research continues to evolve and new developments are consistently made. Computer systems, including software, hardware, algorithms, etc., are constantly improving, and systems need to constantly be tested to determine if models can perform better. We exploit their threats to validity and use updated libraries to replicate their research. For a comparison of software versions 2022 and 2024, refer to

Table 1.

We also use a 2023 optimizer to help us improve the accuracy of their results. Further- more, Fu et al. report that the goal of their research is not to find optimal hyperparameter settings, but to compare it to other models. They suggested that the model can be improved by optimizing the hyperparameters [

7]. We also note that the MickeyMike tokenizer is not working. We switch to SalesForce.

The results of our experiment will address the following research question.

2. Related Works

Recent reports indicate that computers and artificial intelligence are rapidly becoming an integral part of our society. They are widely found in various sectors and impact our daily lives. However, the concern with technological advancement is privacy and the potential for information theft. It seems that criminals or criminal groups may exploit computer systems and create chaos. It is not uncommon to hear that trillions of dollars per year are lost due to cybercrimes. Some of these crimes involve taking advantage of software vulnerabilities, which in turn becomes an issue for software engineers.

Artificial intelligence has permeated our everyday existence, extending to software engineering. With the continuous progress in Artificial Intelligence and Natural Language Processing, as well as advancements in Large Language Models and multimodal learning, software engineers are incorporating A I techniques throughout the software development cycle [

11]. In the context of identifying vulnerabilities in software code, deep learning methods can aid in detecting these flaws. Ongoing research explores the use of machine learning techniques to discover vulnerability patterns for automated detection, in contrast to rule-based methods, and more research is needed to improve it [

12].

Deep learning models have the ability to identify new and unseen vulnerabilities by training on similar vulnerabilities. There are limitations since not all vulnerabilities can be detected. Human testers are still needed, as there is still a gap between deep learning techniques and the specialized ability of human code inspectors [

13]. Research on automatic software repair to detect vulnerabilities is valuable and a challenging endeavor. The vulnerable code needs to be detected or predicted and a repair needs to be generated [

14].

Gupta et al. used deep learning to fix common errors in the C language as they arise, especially from inexperienced programmers [

15]. Feng et al. proposed CodeBERT that is a bimodal pre-trained in Natural Language (NL ) and Programming Language (PL), i.e., Python, Java, Ruby, Go, JavaScript, and PHP. CodeBERT learns the semantics between natural and programming languages and is effective in code searches and code documentation generation [

16]. Mashadi et al. describe debugging as a "time-consuming and labor-intensive task in software engineering" and proposed CodeBERT as an automated program repair to fix Java bugs [

17]. Marjanov et al. found several studies that involve Machine Learning techniques used in bug detection, such as Google’s Error Prone and Spot Bugs. Bug detection and bug correction are a growing field. Most studies target C / C + + and Java, while fewer target Python and other languages. Furthermore, most studies are directed towards semantic defects and vulnerabilities and less towards syntactic defects. Moreover, detection and correction studies usually use R N N along with long short-term memory. However, some will also use convolutional neural networks [

18]. Fu et al. state that Large Language Models, such as ChatGPT have advanced software engineering tasks related to code review and code generation. However, they found that other models, such as their AIBugHunter and CodeBERT, perform better [

19].

We recognize the extensive and intricate domains of security and artificial intelligence models. Our research is confined to static code analysis, which focuses on detecting vulnerabilities in software code before deployment. Unlike dynamic code analysis methods that depend on real-time evaluation or a simulated environment, static analysis does not necessitate the execution of the program. Consequently, the software code can be assessed instantly and does not need to be in a fully executable state towards the end of development.

Although advanced tools are used to uncover vulnerabilities, they are often insufficient as they cannot identify all potential issues. Consequently, static code analysis serves only as an aid in detection and cannot be used as a comprehensive solution to identify all vulnerabilities in a program [

20]. Finally, depending on the situation, a hybrid approach that combines both static and dynamic methods should be considered and may prove more effective [

21].

We specifically examined and reviewed the work of Mike Fu, as referenced earlier [

1,

4]. To find additional research related to VulRepair, we conducted searches on the Internet and Google Scholar, yielding over 100 articles. Regarding general coding and Deep Learning principles, besides the VulRepair code from the AWSM research group [

22], we also consulted various sources including [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Overall, static code analysis is vital as it addresses software vulnerabilities early, and we should continuously advance the software development field by improving the VulRepair model.

3. Methodology

The purpose of the study was to examine VulRepair and improve the model. We gained a perspective by reviewing AIBughunter at [

1], LineVul at [

4], and VulRepair at [

7]. In the VulRepair project, there are threats to their internal validity. VulRepair outperforms other models such as VRepair and CodeBERT. Although it outperforms the leading models, the goal was not to ensure the use of optimal hyperparameters. In fact, Fu et al. provided hyperparameter settings for replication, which can extend their study. In addition, Fu et al. point out a limitation of the T5 architecture such that the vulnerable function is limited to 512 tokens. So VulRepair is more accurate when vulnerable functions have less than 500 tokens. Performance also decreases with repairs that require more than 10 tokens. More research is needed to improve these limitations [

7].

After understanding the areas of VulRepair that needed improvement, we downloaded VulRepair from GitHub [

22]. This provided the code to replicate Fu’s experiment [

7]. We downloaded the code to Google Colab. We upgraded to Colab Pro+, which facilitates long training and testing sessions. Google Drive is attached to Colab. We increased the memory to 100 GB to ensure that we had ample memory to hold the VulRepair files. In addition, we used the Google Chrome browser. When using Colab, we used Google Colab V100 GPU, a high-performance graphics processing unit renowned for its suitability for deep learning and its ability to handle tasks that require substantial memory and processing power [

28].

When running the models, we looked for deprecated warnings and fixed them. For ex-ample, AdamW is deprecated. We looked up fixes from Hugging Face and Stack Overflow. They essentially recommended replacing AdamW with PyTorch AdamW, as explained later. We replicated experiments by Fu et al. and gained insight into their models. Next, we look at the optimizer. Although AdamW is a popular optimizer, we looked for recently developed optimizers that may fit the VulRepair platform. After finding the L I O N optimizer, we adjusted the hyperparameters around it. Our experiment allowed us to improve VulRepair.

3.1. VulRepair Replication

We replicated VulRepair at 44.9% Perfect Prediction. This is 1.15% higher than Fu et al. 43.75%. However, we did not use the "MickyMike" tokenizer or model as Fu et al. and found in [

29]. We used Salesforce/codet5-base found at [

30]. We also use current libraries rather than the recommended libraries used two years ago

We acknowledge that other studies, like ours, may refer to VulRepair with 44.9% PP, as in a research article from 2024 at [

31].

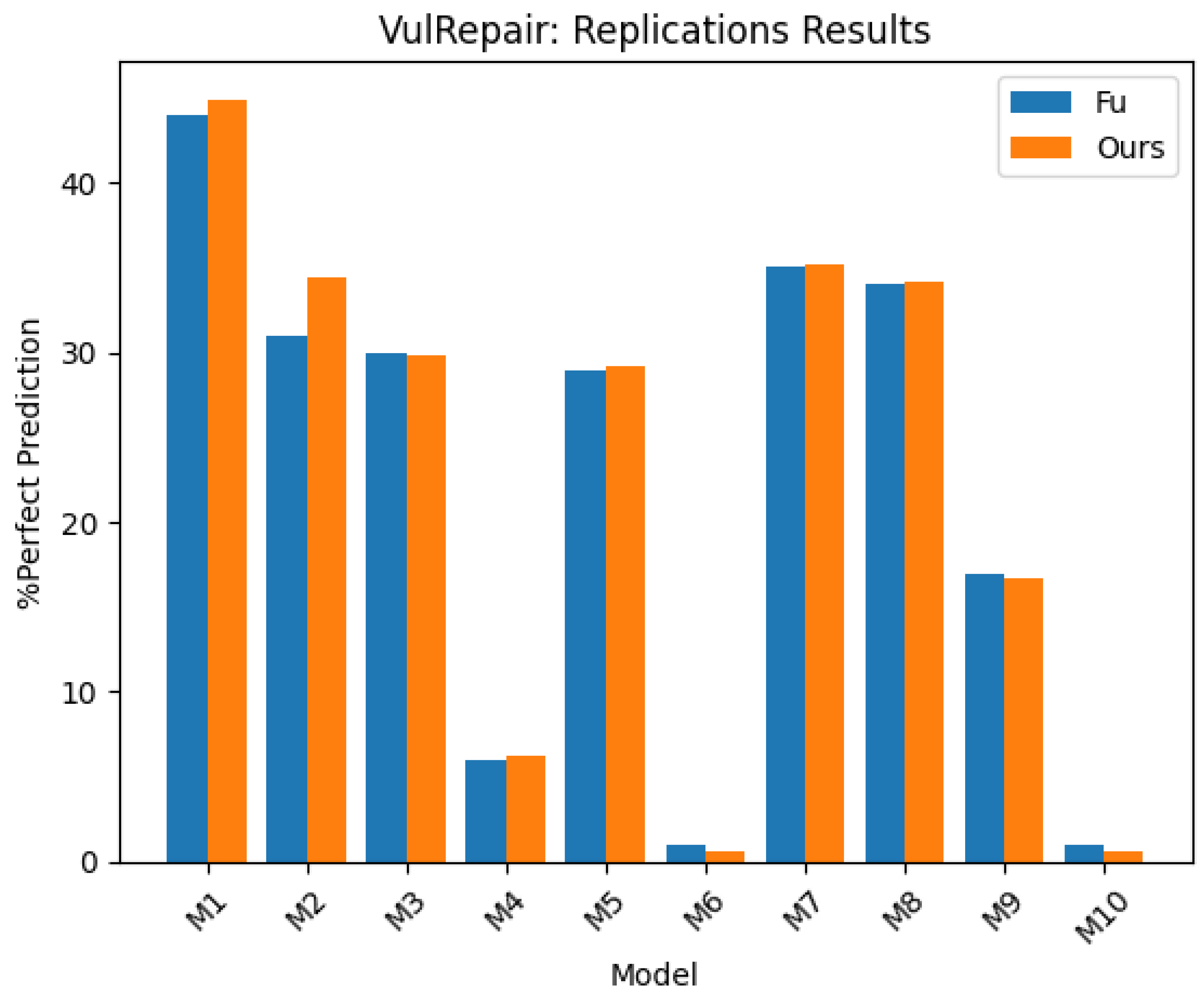

Model 1 (M1) is designated and referred to the VulRepair as we compare to the variation of VulRepair and other models, that is, CodeBERT and VRepair. M1 or the VulRepair components are examined: Byte Pair Encoding Tokenizer, Programming Language (PL) pretraining, Natural Language (NL) pretraining, and the T5 architecture.

In addition, the initial set parameters for VulRepair are the following:

Ten models were made available for testing, including VulRepair, VRepair, and Code-BERT, each undergoing various modifications. We duplicated each model to assess their %PP, as further described. Refer to

Figure 1.

3.2. Replication of Other Models

Following the replication of M1, we proceeded with the replication of the studies by Fu et al. For Models 1 and 2, the models were trained from scratch, allowing us to closely examine their training processes. For Models 3 to 10, we utilized the pretrained models supplied by Fu et al. The goal was not to train, enhance, or benchmark CodeBERT and VRepair, but rather to gain a comprehensive understanding of Fu et al.’s research.

Model 2 (M2) is the CodeBERT platform that utilizes a BPE tokenizer, programming (PL) pre-training, natural language (NL) pre-training, and a BERT architecture. In this case, we trained the model using current libraries, and used Salesforce/codet5-base as in M1, and Google Colab. We also used the deprecated AdamW optimizer as our intention was not to improve these models. We did not use the Fu et al. ’MikeyMike’ tokenizer. We obtained a 34.47% Perfect Prediction after training and testing. Fu et al. reported a 31% PP [

22]. Our results were better by 3.5% but we did not use the exact methods of Fu et al. We did not conduct further testing to pinpoint the improvements nor did we use their trained model.

Model 3 (M3) is VulRepair without PL pretraining compared to M1 with it. This model demonstrates the importance of PL pretraining. In this instance, we did not train the model but used the one provided by Fu et al. We tested the model and obtained 29.89% PP. We compared this to Fu et al. 30% PP.

Model 4 (M4) is VulRepair with no PL or N L pretraining. This model demonstrates that pretraining provides a better PP. We did not train this model from scratch but tested the model. We obtained a 6.21% PP as compared to 6% in the Fu et al. model [

22].

Model 5 (M5) is CodeBERT, or M2, without PL. This is used to make comparisons between VulRepair and CodeBERT, when no PL pretraining is used. We tested the model but did not train from scratch. We obtained 29.19% PP as compared to the Fu et al. reported results of 29% [

22].

Model 6 (M6) is CodeBERT without pretraining. Like M5, it is used as a comparison to VulRepair ’s results. Here, we test it and do not train it from scratch as this is not our primary focus. We obtain 0.64% PP as compared to Fu et al. reported results of 1%.

Model 7 (M7) is VulRepair with a Word-level tokenizer that replaces its subword tokenizer. This demonstrates the importance of its tokenizer. We replicated this by testing. Since it is not our main focus, we do not train it from scratch. We obtained a 35.17% PP as expected and consistent with the Fu et al. model of 35%.

Model 8 (M8) is VRepair, or the Vanilla Transformer with subword tokenization and not the word level tokenizer. This is a model that is compared to both VulRepair and CodeBERT. We tested this model, but did not train from scratch, and obtained a 34.17% PP as expected. It is consistent with Fu et al. results of 34% [

22].

Model 9 (M9) is CodeBERT with a word level tokenizer and not the subword tokenizer. This is compared to VulRepair’s results and also demonstrates the importance of tokenization. We tested the model and did not train it from scratch. We obtained a 16.65% PP as compared to 17% the Fu et al. model at [

22].

Model 10 (M10) is VulRepair with no pretraining, and a word level tokenization rather than subword tokenization. This shows that VulRepair requires N L and PL pretraining and subword tokenization to achieve superior results when compared to CodeBERT and VRepair. Without training from scratch, we tested the model at 0.64%. This is expected and compared to the Fu et al. model of 1%.

3.3. Improving VulRepair: ImpVulRepair

To improve VulRepair, we constructed ImpVulRepair by looking at the hyperparameters of VulRepair, which influence the learning process of a model, then adjusted the hyperparameters to improve its performance by searching for optimizers. During the choice of an optimizer, various options were explored, including the LION optimizer, as discussed in research articles such as [

32]. The decision was made based on the characteristics described for each optimizer, assessing their efficiency, and determining their compatibility with the T5 neural network.

When selecting values for other hyperparameters, we used a different approach. There are different methods when optimizing hyperparameters such as manual search, random search, grid search, halving search, automated tuning, artificial neural networks tuning, etc. [

33]. We used a half-random search to evaluate hyperparameter values as well as information on the optimization research paper by Chen et al. at [

32]. We use the evaluation loss from training as our guide when selecting or tuning hyperparameters, since testing takes more than 5 hours. We select the hyperparameter value on the basis of the lowest loss. Training also takes time. Although it may not be ideal, we use only one epoch to find the best hyperparameter. We use this method when reviewing the learning rate, weight decay, batch size, encoder/decoder block size, and betas. This is not an exhaustive grid search, and there could be other combinations that provide a better model.

3.3.1. Optimizer

Optimizers are algorithms that are used to minimize the loss function by changing the weights and learning rate of neural networks, thus reducing the loss between the true values and the predicted values [

34]. Stochastic Gradient Descent, Momentum Optimizer, RMSprop Optimizer, and Adam are several examples of optimizers. Google developed a PyTorch optimizer in 2023, as reported by [

32]. It is supposedly better for transformer architectures. It is also memory-efficient. It seems like a viable option that we can use for ImpVulRepair. To obtain information and understanding, we visit GitHub, which explains the optimizer and implementation [

35].

3.3.2. Learning Rate

The learning rate is a hyperparameter that determines the step size to update the model parameters. Larger learning rates lead to faster convergence towards optimal weights, while smaller rates result in slower convergence. If the learning rate is too high, it can cause instability during training. If the learning rate is too small, it will take longer to reach the

minimum loss. We tested several learning rates for our ImpVulRepair model. The learning rate is supposed to be lower for the L I ON optimizer. We tested learning rates at 2e-6, 1e-5, 2e-5, 2.25e-5, 2.75e-5, 3e-5. The lowest learning rate that showed the lowest evaluation loss with the L I O N optimizer is 2e-5.

3.3.3. Weight Decay

Weight decay is a regularization technique that adds a penalty to the cost function and reduces overfitting. The default decay weight for AdamW is 0.01 while the L ION optimizer does not have one, and it is not set. The weight decay in L I ON is supposed to balance with the learning rate. The learning weights are supposed to be smaller, and the weight decays are supposed to be larger [

32]. I tested various weight decays that included .01, .1, .001, and .0001, and .00001. Since higher weight decays are preferable, and there were negligible differences between weight decays of 0.001 and smaller, we use 0.001 as weight decay. It showed a low loss with a set learning rate of 2e-5.

3.3.4. Batch Size

Batch size is the number of samples that will be used in the network model before the weights in the model are updated. VulRepair starts with a batch size of 4. L I O N reports that it performs better with larger batch sizes [

32]. We tested the batch size at 32 and 16. These were too large because we received out-of-memory messages. We looked at lower values that included 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. We used 2 as the batch size, as it showed the lowest loss.

3.3.5. Encoder & Decoder Block Size

The T5 transformer is an encoder decoder model or a text-to-text transfer transformer that is used in various N L P tasks by converting text input into text output. Encoders are used to understand and extract relevant information from text input and then convert the input sequence into a vector. The decoder inputs this vector and predicts an output sequence. A s noted by Fu et al., the T5 architecture is limited to 512 tokens, so anything larger is truncated. This means that the truncated portion is not processed by the machine learning model and its usefulness is lost. Similarly, VulRepair performs best if the patch to the vulnerability contains fewer than 20 tokens. Fu et al. state that researchers should explore techniques that handle these larger token sizes for the vulnerability function and for its repair [

7]. We note that the model itself is provided in binary form, so we will not try to adjust the neural network layers.

However, according to the GitHub site of Fu et al., the encoder block size is set at 512, the maximum source length, and the decoder block size is set at 256, the maximum target length [

22]. They are provided, and we adjust them and use them for training and testing. We treat them as hyperparameters and observe their performance behavior. We could double the block size to 1024 for the encoder and 512 for the decoder and produce stable results by adjusting other hyperparameters.

When we increase the size of the block, we note that the training time increases. For example, it took 17 hours to train 57 epochs when we set the encoder to 1024 and the decoder to 512. However, it took 9 hours to train the model at 75 epochs when the encoder was set at 512 and the decoder at 256. This is not surprising since padding can significantly slow training and should only be padded up to the longest example in a batch [

37]. In addition, as the block sizes doubled, the G PU and the Google drive disconnected at 57 epochs. In this case, we did not have stable results, but proceeded to test the model and returned with a 40% Perfect Prediction. This is lower than Fu’s VulRepair of 44%. We could adjust the hyperparameters to achieve stabilization, which we do in subsequent tests.

We also found that anything over 1536 for the encoder along with 512 for the decoder block sizes immediately produces an out-of-error response. We tried different combinations such as 1280/512 for the encoder/decoder, respectively, in training. Some combinations will allow the model to train, but will not test well. Memory errors, GPU and file disconnections, and screen freezing can occur.

We also tried to eliminate out-of-memory errors by reducing the beam size. For example, we increased the encoder block size to 1280 and the decoder block size to 512 for training. We decreased the beams from 50 to 40. ImpVulRepair achieved 52.7% Perfect Prediction.

Although we could further adjust different combinations of hyperparameters to increase the Perfect Prediction, we limited the training to 1024 for the encoder and 512 for the decoder. Although we tested the beam at 40, we did not perform an exhaustive search to determine the optimal relationship between the encoder, the decoder, and the beam sizes. We could achieve stable testing if we set the beams at 50 depending on other hyperparameter settings.

3.3.6. Betas

Momentum, in optimizers, refers to the loss function, as it accelerates the convergence towards the minimum. We want a loss function to move horizontally, using larger steps, towards the minimal loss while moving in smaller steps in the vertical direction. Momentum is a way that gradient descent does not oscillate as it moves towards the minimum. There are two betas in the L I O N optimizer as well as in AdamW. They determine the update direction of the momentum. β-1 is the decay rate of the gradient. L I ON and AdamW have a default value of 0.9. β-2 is the decay rate of the squared gradient. L I O N has a default value of 0.99 while AdamW has a default value of 0.999 [

32].

We trained the ImpVulRepair model with the L I O N optimizer and its default beta values, which produced 55.7% PP. In order to produce better accuracy, we tuned L I ON β-1 to 0.09, 0.6, 0.8, 0.9 (default for L I ON and AdamW), and 0.99. 0.8 produced the lowest loss. We tuned L I O N β-2 to 0.9, 0.96, 0.98, 0.99 ( L I O N default), 0.999 (AdamW default). 0.98 produced the lowest loss.

Thus, we trained the values 0.8 for β-1 and 0.98 for β-2. Although we were able to reduce the training from 9 epochs to 8 epochs, our training is unstable. In our first attempt, the training log saved only one of ten epochs. We define instability as saving fails, the GPU and files disconnect, and the screen freezes. In our second attempt, we received an OS error at the end of the testing. A file was not connected. However, ImpVulRepair produces the results of 51.93% PP. This is not our best result, and the testing is unstable. Therefore, it is best to use the default beta values, as they contribute to a higher prediction and stability.

4. Results

We conducted numerous training and tests that involved hundreds of hours. The longest training on a G PU took more than 17 hours. Our best results took approximately 3 hours to train and 6 hours to test. We found a stable solution by using Google Colab, Google Chrome, Google Drive, the L I O N optimizer developed by Google Brain, and by adjusting hyperparameters, to significantly improve VulRepair’s Perfect Prediction from 44% to 56%.

4.1. LION Optimization

We conducted training and then testing and ensured that our model provided stable results. The V100 G PU and Google Drive were not disconnected and the screen did not freeze. This took 2 hours and 52 minutes to train and 5 hours and 54 minutes to test. To see and compare the VulRepair and ImpVulRepair hyperparameters, refer to

Table 2.

Our results show a 55.7% Perfect Prediction.

4.2. Testing Deprecated AdamW

VulRepair uses AdamW as an optimizer. Using most of the hyperparameter settings from ImpVulRepair, we tested it by switching from the L ION optimizer back to the AdamW optimizer. Because the original VulRepair setting used 75 epochs, we also increased the training from 10 to 75. In our setup, we obtained 40% perfect prediction but the G PU and the files had disconnected. We stopped testing after 49 epochs. This performed worse than the Fu et al. model.

Figure 2.

ImpVulRepair shows a Perfect Prediction at 56%.

Figure 2.

ImpVulRepair shows a Perfect Prediction at 56%.

4.3. Testing PyTorch AdamW

Toward the end of the testing of VulRepair in Colab, we receive messages in Colab that AdamW is deprecated and will be replaced in the future. It should be replaced with the PyTorch AdamW. According to stack overflow, the problem could be solved by replacing "optimizer = AdamW..." with "optimizer = optim.AdamW..." [

38]. The Hugging Face forum says to use torch.optim.AdamW, which is the PyTorch implementation, or turn off the warning, that is, set the no_deprecation_warning=True [

39].

From the ImpVulRepair settings, we switch the L I O N optimizer to the PyTorch AdamW optimizer, that is, "torch.optim.AdamW." We avoid the deprecated warning. We also increase the epochs from 10 to 75 since the original VulRepair used 75 epochs. We achieved a perfect prediction of 50.4%. According to the training log, the best results occur after 14 epochs. We did not test after 55 epochs, since the files and the G PU eventually disconnected. Although the training was unstable, it performed better than the Fu et al. model, at 44%, but not better than the stable training of the L I O N optimizer, at 56%

5. Discussion

Using current libraries, a recently developed optimizer, i.e., L I O N over AdamW, and hyperparameter adjustment, we created ImpVulRepair. It not only relied on updated libraries and software, such as Python version 3.10.12 over version 3.9.7, but used Google Colab V100 over N V I D I A 3090 as the Graphics Processing Unit. Our ImpVulRepair repaired vulnerable functions with patches and achieved a perfect prediction of 56% while VulRepair, developed in 2022, repaired vulnerable C / C + + functions at 44% PP.

ImpVulRepair included Google Chrome browser, Google Colab, Google Drive, L I O N created by Google Brain, and even the T5 architecture was introduced by Google in 2019. Our intention was not to show that Google products are in tune with each other but to try and resolve the disconnection of the G PU and the disconnection from the attached files. However, at the end of this testing, Google Colab started offering new GPUs that may perform better. They also offer Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) version 2. These TPUs are developed by Google and are suitable for neural networks dealing with large datasets, and may outperform GPUs in some situations [

28]. The Colab T PU version 1, as well as the V100 GPU that we used, as of April 2024, are being deprecated. ImpVulRepair could attain consistent results in areas where previous tests failed. Exploring and evaluating newly available Colab GPUs and TPUs might reveal improvements in patching vulnerabilities.

With regard to best practices, data sets should be prepared for training in machine learning models. This includes cleaning the data by removing duplicates, that is, deduplication of data [

40]. If duplicates are not removed, the model may have an inflated efficiency [

41]. The data sets used in the training and testing of VulRepair contain duplicates. Although it may not be ideal, it should be documented and, at best, justified. We acknowledge it but do not justify it. According to [

42], 60% of the pairs are duplicates. If the data sets are deduplicated, the performance goes from 44.2% to 10.2%. Another study found that 40% of the data overlap between the training set and the test set [

43]. Their Mistral model uses 7 billion parameters and 5 epochs, while VulRepair uses 220 million parameters and 75 epochs. Both use the AdamW optimizer. If overlap is used, a 57% performance prediction, with a beam size of 5, can be achieved, but it reduces to 26% with deduplication. These studies indicate that our results will be lower with the deduplication of data.

Regarding performance, in one study, Yang et al. claim that their TSBPORT, or Type Sensitive patch BackPORTing, improved the success rate of VulRepair by 63.9% [

44]. Learning models need sufficient data to train. An external threat to VulRepair is that it may not generalize well to other CWEs and other datasets. Other datasets could be explored [

7]. In one study, Nong et al. assert that the lack of datasets for vulnerable programs prevents them from progressing. They use a new technique called V G X to generate "high-quality" vulnerability data sets and can improve VulRepair by 85% [

45]. Because our ImpVulRepair is an extension of VulRepair, we see that the datasets could also be used to improve the model training.

Like Fu et al., we did not conduct an exhaustive search to refine all hyperparameters, nor did we attempt to increase memory with different equipment. In addition, further testing to improve vulnerability patching performance could be conducted in a cloud environment such as Google Cloud Platform (GCP), Amazon Web Services (AWS), or Microsoft Azure. Our goal was to show that software evolves and that updated algorithms, such as using a 2023 optimizer, LION, should be tested for increased model performance.

6. Limitation

Our study acknowledges several constraints. The T5 model was neither developed nor trained by us. Adjustments to the deep learning layers, either horizontally or vertically, were not feasible as we were limited to using only the binary file. We depended on the models provided by Fu et al. Additionally, Colab was chosen as it offers a conducive environment for enhancing VulRepair, with its ease of setup and pre-installed libraries. Our experiments required an Internet connection to Colab. Although an updated N V I D I A 4090 G PU is available, we did not access one on a local machine for testing. Despite achieving stable results, local testing could potentially eliminate Internet connectivity issues and enhance stability. Moreover, while some studies have shown improvements in VulRepair using AdamW, we did not explore the potential enhancements from the L I ON optimizer due to time and cost constraints. Such investigations may be more appropriate for researchers who manage their models.

7. Conclusion

Software vulnerabilities are defects in programming codes that can be exploited, necessitating tools like AIBugHunter to detect and repair such vulnerabilities. Developed by the ASWM research group, AIBugHunter scans C / C + + programs, identifies vulnerabil

ities by C WE type, estimates severity using CVSS scores, and suggests repairs. The tool integrates with Visual Studio Code and utilizes LineVul and VulRepair technologies for enhanced detection and repair capabilities. LineVul, a transformer-based model, predicts and locates vulnerabilities, while VulRepair, based on the T5 architecture, effectively repairs them, showing a 44% perfect prediction rate. The research utilizes datasets like Big-Vul and CVEfixes to evaluate and improve the tool’s performance. The study highlights the importance of pre-training with natural and programming languages and the effectiveness of subword tokenization in improving repair predictions. Fu et al. significantly improved their model, illustrating superiority over competitors such as VRepair and CodeBERT. Their methodology was based on technologies from 2022. For example, they used Python 3.9.7, but now version 3.10.12 is available. They employed an N V I D I A GPU 3090, and now the more recent 4090 model is accessible - two years later.

Our study used Google Colab, Google Drive, and a Google V100 GPU to develop and evaluate ImpVulRepair rather than using the N V I D I A 4090. We carefully fine-tuned or adjusted the hyperparameters surrounding the ImpVulRepair model for training, and then integrated contemporary libraries. Moreover, unlike VulRepair which used the AdamW optimizer, our method adopted newer technologies including the L I ON optimizer, developed by Google Brain in 2023. This methodology allows us to better detect vulnerable functions and increase the Perfect Prediction as our model demonstrated a success rate of 56% in perfect predictions, exceeding their 44%. This means that we can provide more patches for vulnerabilities and prevent more cyber attacks.

Author Contributions

Al l authors contributed equally to this project. Writing – original draft, Brian Kishiyama; Writing – review & editing, Young Lee and Jeong Yang

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| T L A |

Three letter acronym |

| PL |

Programming Language |

| N L |

Natural Language |

| T5 |

Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer |

| L I ON |

Evolved Sign Momentum |

| CWE |

Common Weakness Enumeration |

| CWSS |

Common Vulnerability Scoring System |

References

- Michael Fu, Chakkrit Tantithamthavorn, Trung Le, Yuki Kume, Van Nguyen, Dinh Phung and John Grundy. AIBugHunter: A Practical tool for predicting, classifying and repairing software vulnerabilities. Empirical Software Engineering, 29(1):4, November 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mitre. CWE - About CWE, March 2024.

- NIST. N V D - Vulnerability Metrics, September 2022.

- Michael Fu and Chakkrit Tantithamthavorn. LineVul: A Transformer-based Line-Level Vulnerability Prediction. In 2022 IEEE/ACM 19th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR), pages 608–620, 2022.

- Yi Li, Shaohua Wang, and Tien N. Nguyen. Vulnerability detection with fine-grained interpreta-tions. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, ESEC/FSE 2021, pages 292–303, New York, NY, USA, 2021. Association for Computing Machinery. event-place: Athens, Greece.

- What is the T5-Model? | Data Basecamp, September 2023. Section: ML - Blog.

- Michael Fu, Chakkrit Tantithamthavorn, Trung Le, Van Nguyen, and Dinh Phung. VulRepair: a T5-based automated software vulnerability repair. In Proceedings of the 30th AC M Joint Euro- pean Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, E SE C / F SE 2022, pages 935–947, New York, N Y, USA, 2022. Association for Computing Ma- chinery. event-place: <conf-loc>, <city>Singapore</city>, <country>Singapore</country>, </conf-loc>.

- Jiahao Fan, Yi Li, Shaohua Wang, and Tien N. Nguyen. A C / C + + Code Vulnerability Dataset with Code Changes and C V E Summaries. In 2020 IEEE/ACM 17th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR), pages 508–512, 2020.

- ZeoVan. ZeoVan/MSR_20_code_vulnerability_csv_dataset, April 2024. original-date: 2020-06- 25T04:47:52Z. 547.

- Guru Prasad Bhandari, Amara Naseer, and Leon Moonen. CVEfixes: automated collection of vulnerabilities and their fixes from open source software. Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Predictive Models and Data Analytics in Software Engineering, 2021.

- Songhui Yue. A data-to-product multimodal conceptual framework to achieve automated software evolution for context-rich intelligent applications, 2024.

- Christoforos Seas, Glenn Fitzpatrick, John A. Hamilton, and Martin C. Carlisle. Automated Vulnerability Detection in Source Code Using Deep Representation Learning. In 2024 I E E E 14th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), pages 0484–0490, 2024.

- Guanjun Lin, Sheng Wen, Qing-Long Han, Jun Zhang, and Yang Xiang. Software Vulnerability Detection Using Deep Neural Networks: A Survey. Proceedings of the IEEE , 108(10):1825–1848, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Martin Monperrus. Automatic Software Repair: A Bibliography. AC M Comput. Surv., 51(1), January 2018. Place: New York, N Y, U SA Publisher: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Rahul Gupta, Soham Pal, Aditya Kanade, and Shirish K . Shevade. DeepFix: Fixing Common C Language Errors by Deep Learning. In A A A I Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Zhangyin Feng, Daya Guo, Duyu Tang, Nan Duan, Xiaocheng Feng, Ming Gong, Linjun Shou, Bing Qin, Ting Liu, Daxin Jiang, and Ming Zhou. CodeBERT: A pre-trained model for program- ming and natural languages. In Trevor Cohn, Yulan H e and Yang Liu, editors, Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, pages 1536–1547, Online, November 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Ehsan Mashhadi and Hadi Hemmati. Applying CodeBERT for Automated Program Repair of Java Simple Bugs. 2021 IEEE/ACM 18th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR), pages 505–509, 2021.

- Tina Marjanov, Ivan Pashchenko, and Fabio Massacci. Machine Learning for Source Code Vulnerability Detection: What Works and What Isn’t There Yet. I EEE Security & Privacy, 20(5):60– 76, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Fu, C. Tantithamthavorn, V. Nguyen, and T. Le. ChatGPT for Vulnerability Detection, Classification, and Repair: How Far Are We? In 2023 30th Asia-Pacific Software Engineering Conference (APSEC), pages 632–636, Los Alamitos, C A , USA, December 2023. I E E E Computer Society.

- Midya Alqaradaghi and Tamás Kozsik. Comprehensive Evaluation of Static Analysis Tools for Their Performance in Finding Vulnerabilities in Java Code. I E E E Access, 12:55824–55842, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Thomas Sutter, Timo Kehrer, Marc Rennhard, Bernhard Tellenbach, and Jacques Klein. Dynamic Security Analysis on Android: A Systematic Literature Review. I E E E Access, 12:57261–57287, 2024. [CrossRef]

- awsm-research/VulRepair, March 2024. original-date: 2022-07-19T01:29:56Z.

- Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville. Deep Learning. MIT Press, 2016. http: //www.deeplearningbook.org.

- Amita Kapoor, Antonio Gulli, and Sujit Pal. Deep Learning with TensorFlow and Keras. Packt, 3rd edition, 2022. 587.

- Aurelien Geron. Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques to Build Intelligent Systems. O’Reilly Media, Inc., 3rd edition, 2023.

- Chirag Shah. A Hands-On Introduction to Machine Learning. Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- A.C. Müller and S. Guido. Introduction to Machine Learning with Python: A Guide for Data Scientists. O’Reilly Media, 2016.

- Rommel Jay Gadil. Maximizing Computing Power: A Guide to Google Colab Hardware Options, October 2023.

- Michael Fu. MickyMike/VulRepair · Hugging Face, 2022.

- Yue Wang, Weishi Wang, Shafiq Joty, and Steven C. H . Hoi. Codet5: Identifier-aware unified pre-trained encoder-decoder models for code understanding and generation, 2021.

- Xin Zhou, Kisub Kim, Bowen Xu, DongGyun Han, and David Lo. Large Language Model as Synthesizer: Fusing Diverse Inputs for Better Automatic Vulnerability Repair, February 2024. arXiv:2401.15459 [cs].

- Xiangning Chen, Chen Liang, Da Huang, Esteban Real, Kaiyuan Wang, Yao Liu, Hieu Pham, Xuanyi Dong, Thang Luong, Cho-Jui Hsieh, Yifeng Lu, and Quoc V. Le. Symbolic Discovery of Optimization Algorithms, May 2023. arXiv:2302.06675 [cs].

- Shanthababu Pandian. A Comprehensive Guide on Hyperparameter Tuning and its Techniques, February 2022.

- Yash Bhaskar. Lion Optimizer, November 2023.

- Phil Wang. lucidrains/lion-pytorch, March 2024. original-date: 2023-02-15T04:24:19Z.

- Keras. keras L I ON optimizer, March 2024.

- Colin Raffel, Noam Shazeer, Adam Roberts, Katherine Lee, Sharan Narang, Michael Matena, Yanqi Zhou, Wei Li, and Peter J. Liu. Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer, September 2023. arXiv:1910.10683 [cs, stat].

- Darren Cook. Implementation of AdamW is deprecated and will be removed in a future version. Use the PyTorch implementation torch.optim.AdamW, February 2023.

- Panco. FutureWarning: This implementation of AdamW is deprecated and will be removed in a future version. Use the PyTorch implementation torch.optim.AdamW instead - Beginners, July 2023. Section: Beginners.

- Stuart Logan. Training A I in 2024: Steps & Best Practices, February 2024.

- Slater Victoroff. Should we remove duplicates from a data set while training a Machine Learning algorithm (shallow and/or deep methods)?, February 2019.

- Xin Zhou, Kisub Kim, Bowen Xu, Donggyun Han, and David Lo. Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Better Automatic Vulnerability Repair by Broadening Input Ranges and Sources. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 46th International Conference on Software Engineering, pages 1–13, Lisbon Portugal, April 2024. AC M.

- David de Fitero-Dominguez, Eva Garcia-Lopez, Antonio Garcia-Cabot, and Jose-Javier Martinez- Herraiz. Enhanced Automated Code Vulnerability Repair using Large Language Models, January 2024. arXiv:2401.03741 [cs].

- Su Yang, Yang Xiao, Zhengzi Xu, Chengyi Sun, Chen Ji, and Yuqing Zhang. Enhancing OSS Patch Backporting with Semantics. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, pages 2366–2380, Copenhagen Denmark, November 2023. AC M.

- Yu Nong, Richard Fang, Guangbei Yi, Kunsong Zhao, Xiapu Luo, Feng Chen, and Haipeng Cai. Vgx: Large-scale sample generation for boosting learning-based software vulnerability analyses, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).