Submitted:

07 June 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

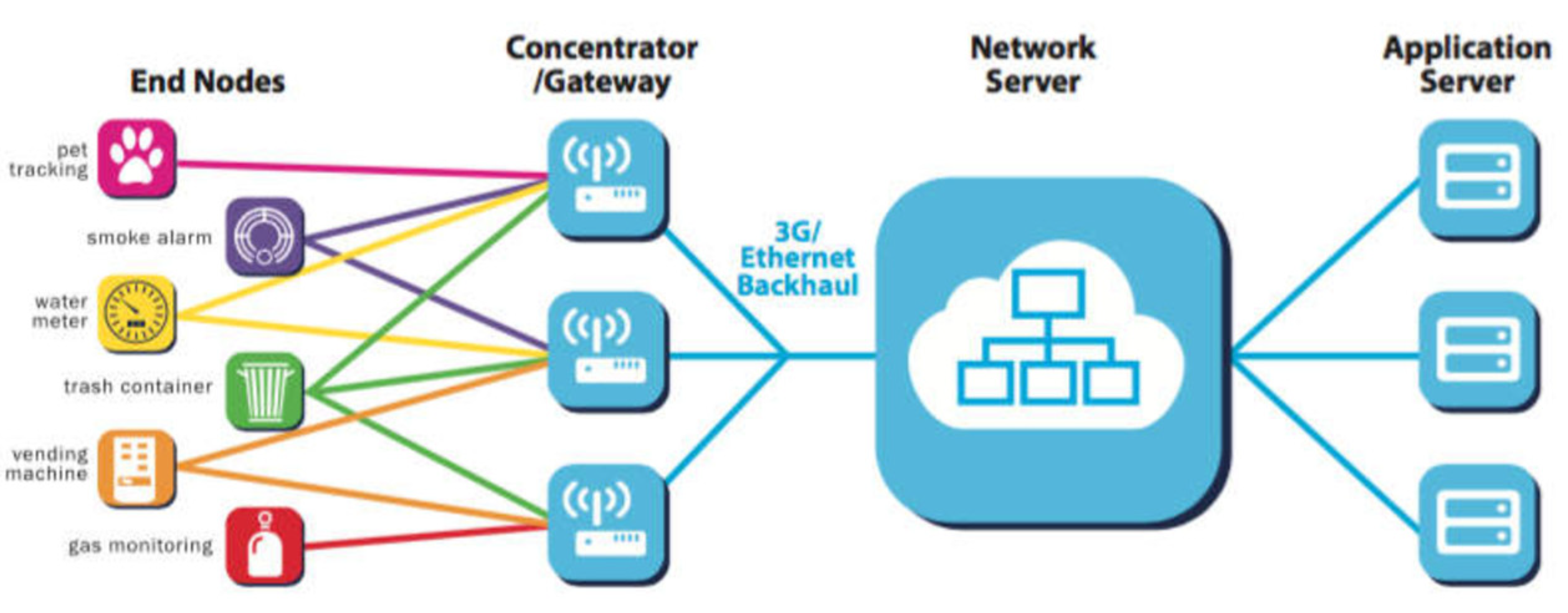

1. Introduction

2. State of the Art

3. LoRa Technology

3.1. LoRa Basics

-

Types:

- ▪

- Frequency Hopping Spread Spectrum (FHSS): Rapidly changes the carrier frequency according to a predefined pattern.

- ▪

- Direct-Sequence Spread Spectrum (DSSS): Spreads the signal using a pseudorandom code sequence.

- ▪

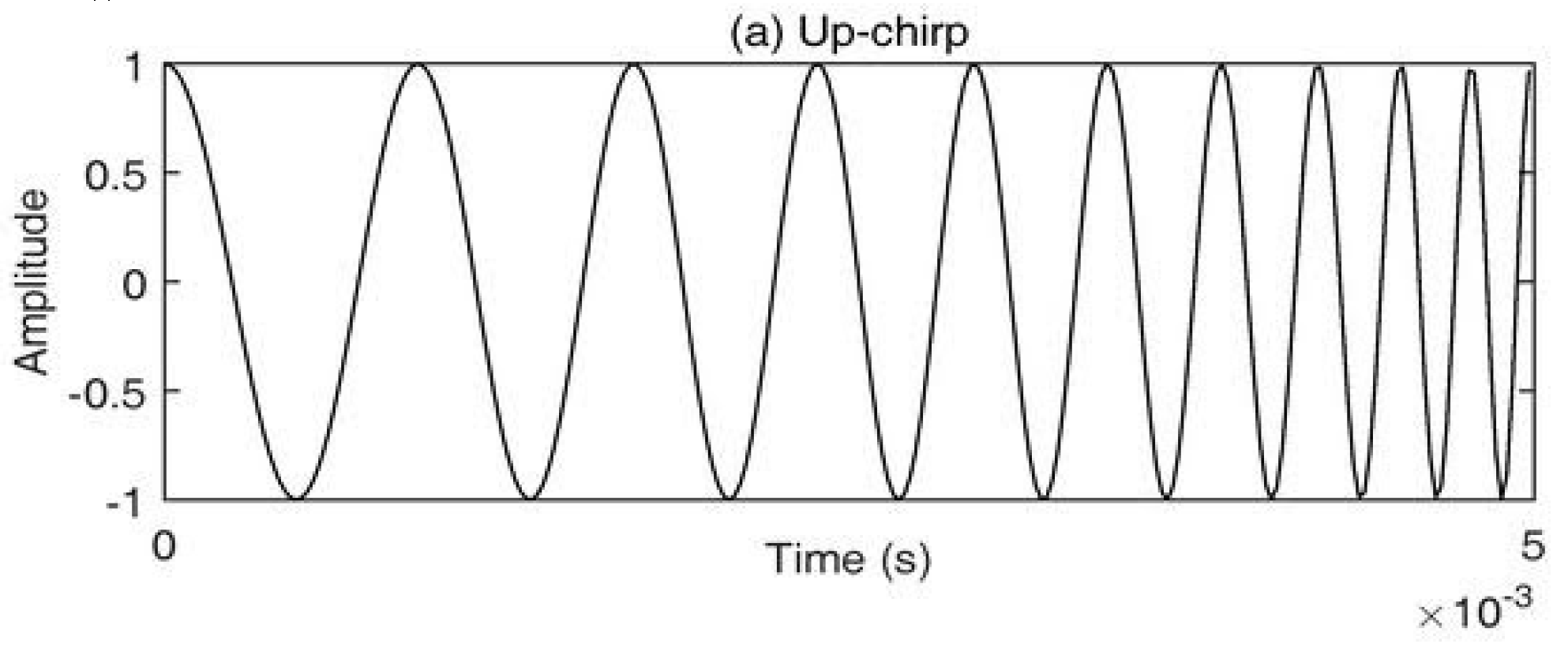

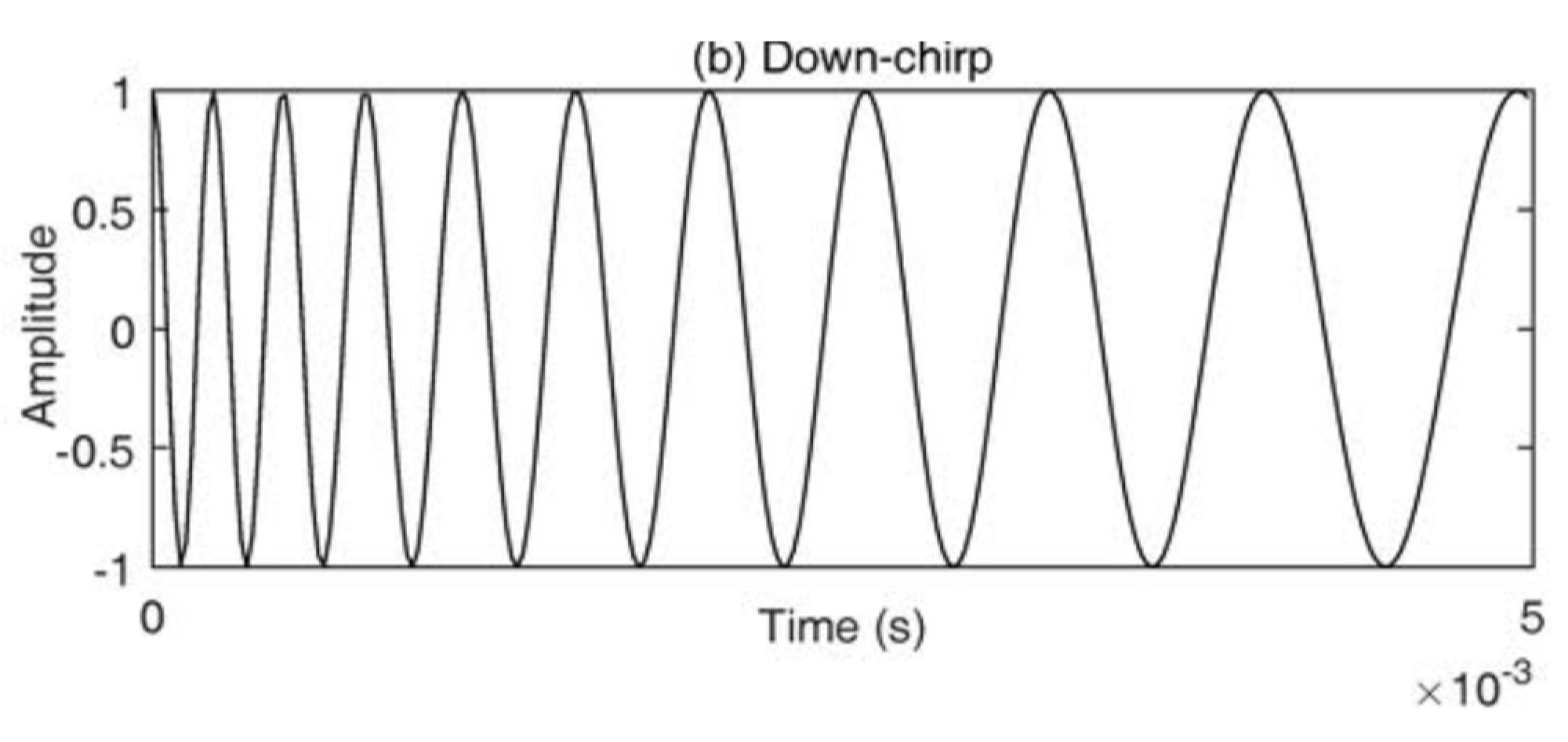

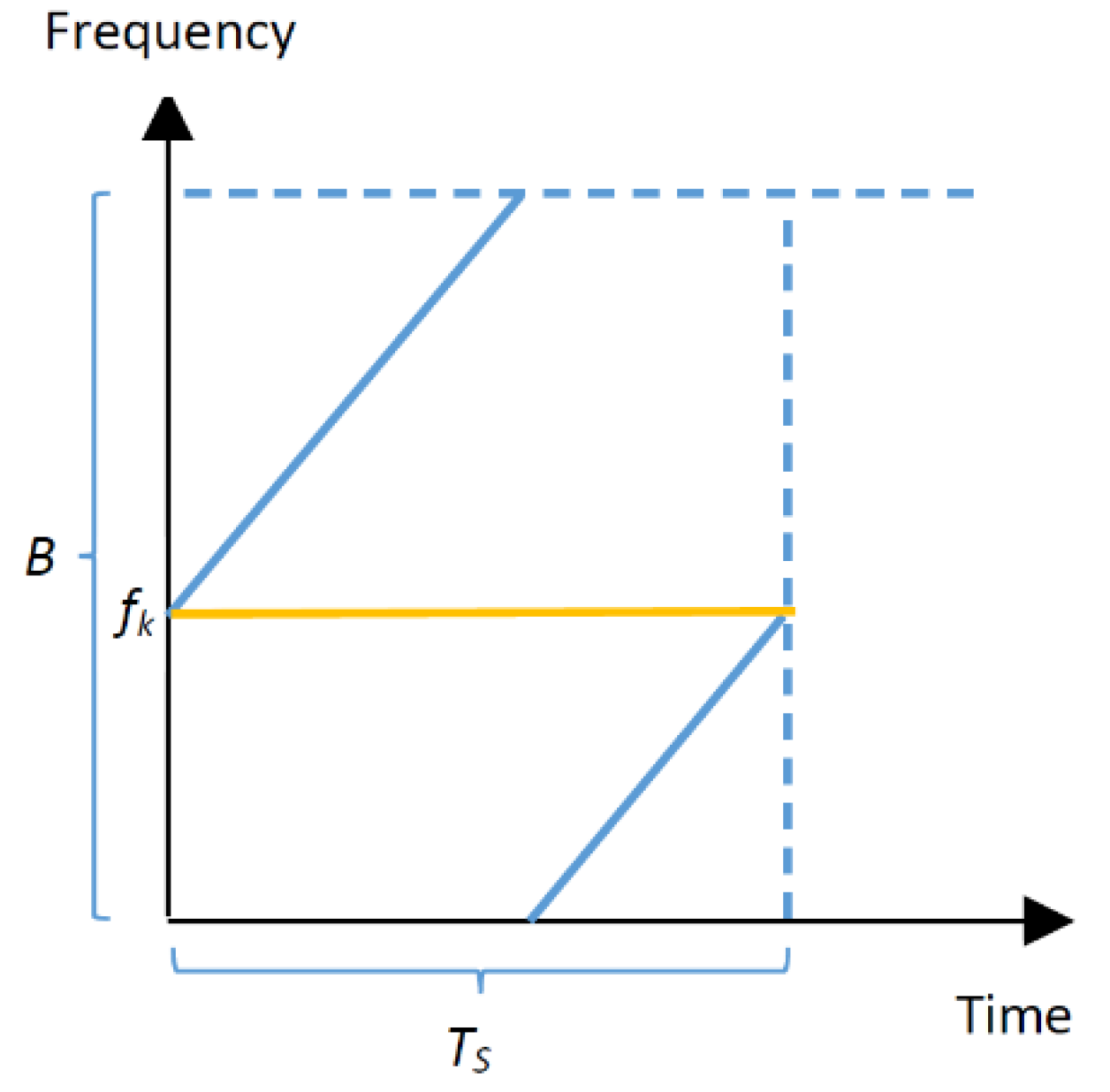

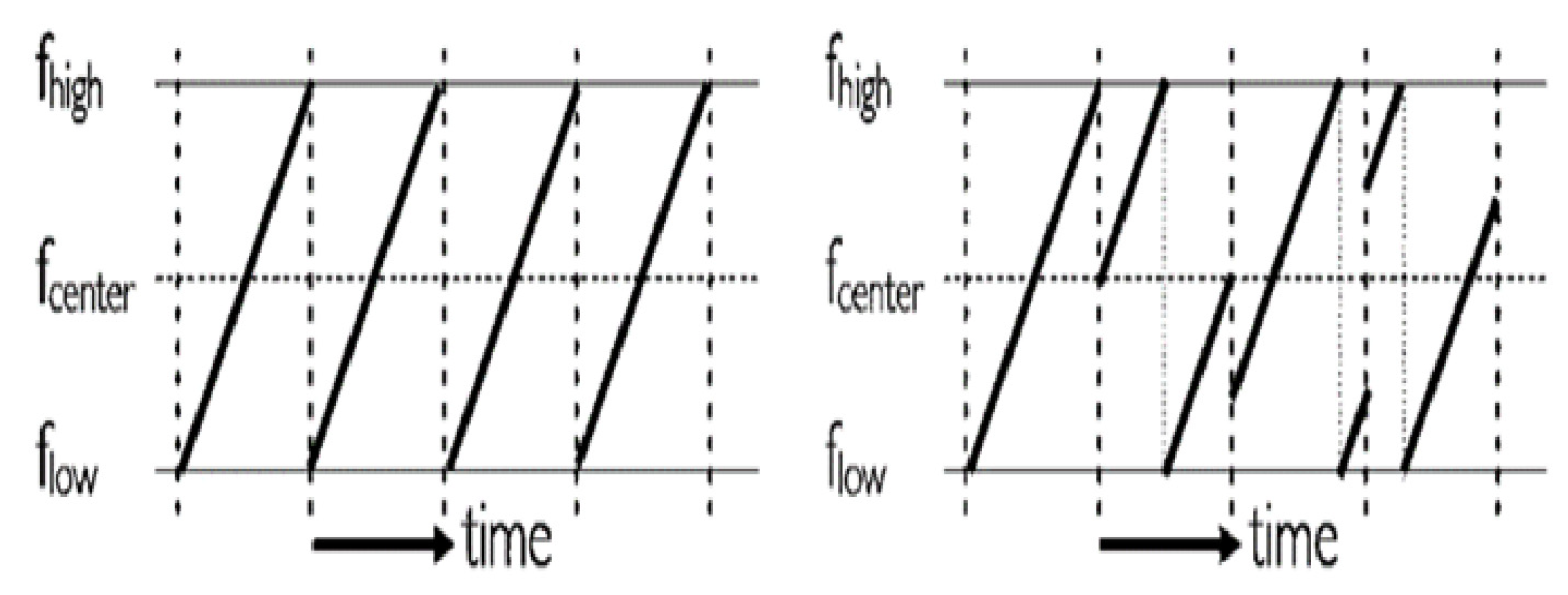

- Chirp Spread Spectrum (CSS): Utilizes linear frequency-modulated chirp pulses.

-

Advantages:

- ▪

- Robustness: They enhance resistance to interference, noise, and multipath fading.

- ▪

- Security: Spread spectrum signals are harder to intercept or jam.

- ▪

- Low Power: They allow low-power communication.

- ▪

- Robustness: DSSS is less sensitive to interference and noise, making it suitable for challenging environments.

- ▪

- Clock Independence: Unlike CSS, DSSS does not require a highly accurate reference clock, simplifying implementation.

- ▪

- Spectral Spreading: In DSSS, the signal’s spectrum spreads by directly encoding data bits across a wider bandwidth, enhancing robustness.

- ▪

- It is easily scalable in both frequency and bandwidth.

- ▪

- Resistant to multipath, fading, and Doppler phenomena.

- ▪

- Allows communication via multiple signals due to orthogonality between different Spreading Factor (SF).

- ▪

- , bit rate (or data rate) [bit/s]

- ▪

- , Bandwidth [Hz]

- ▪

- , Code rate (varies between 1 and 4)

- ▪

- , Spreading factor

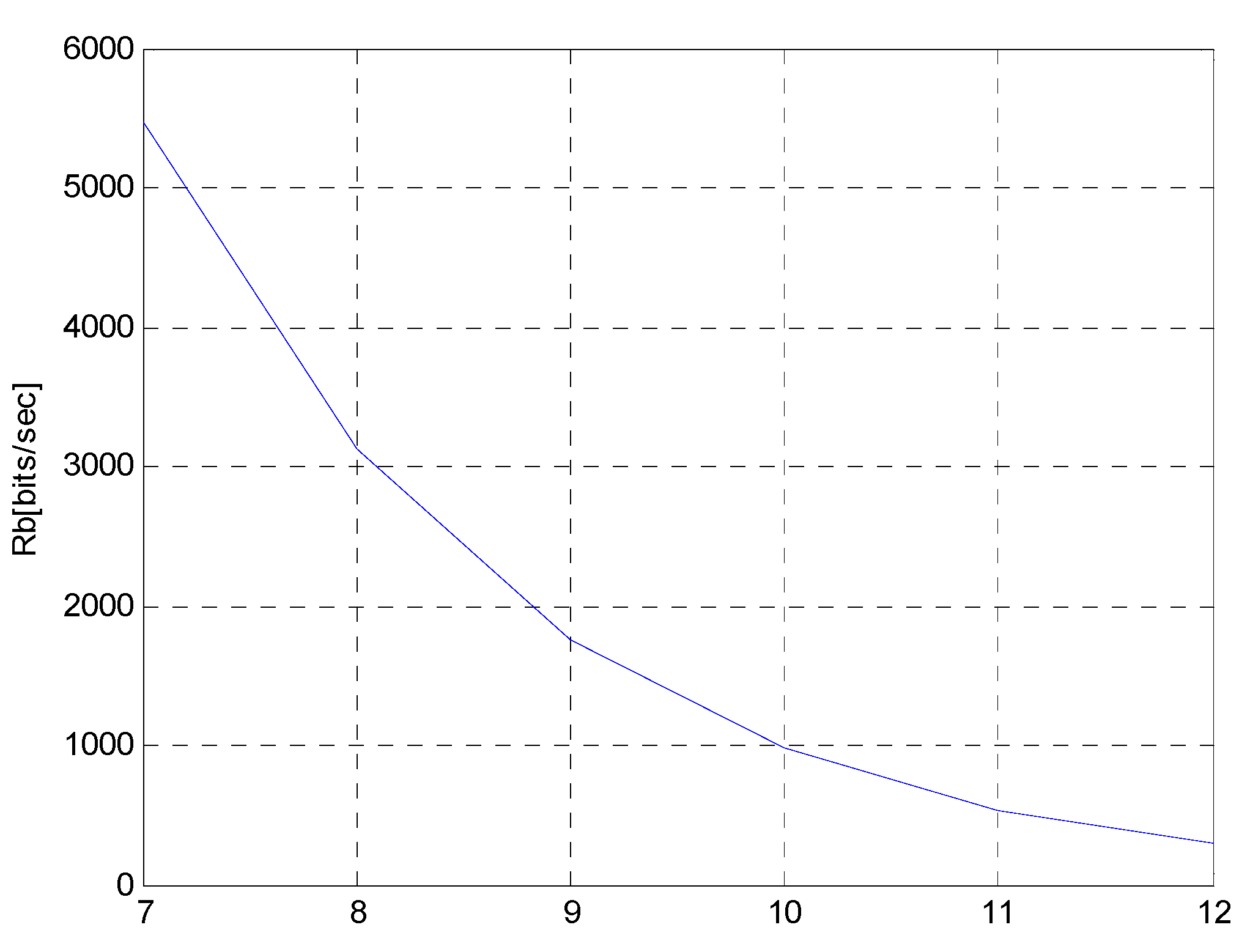

3.1.1. Spreading factor

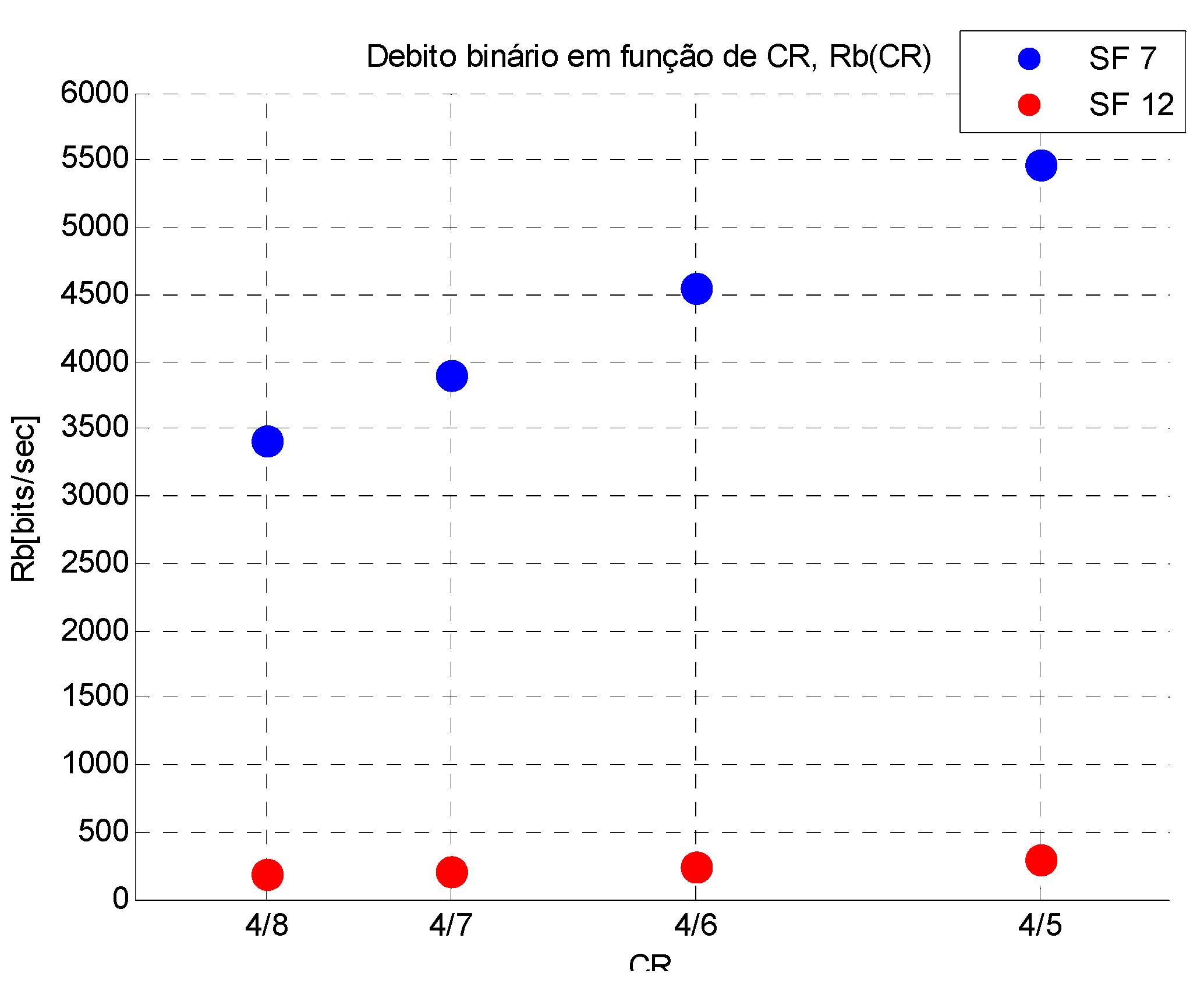

3.1.2. Code Rate

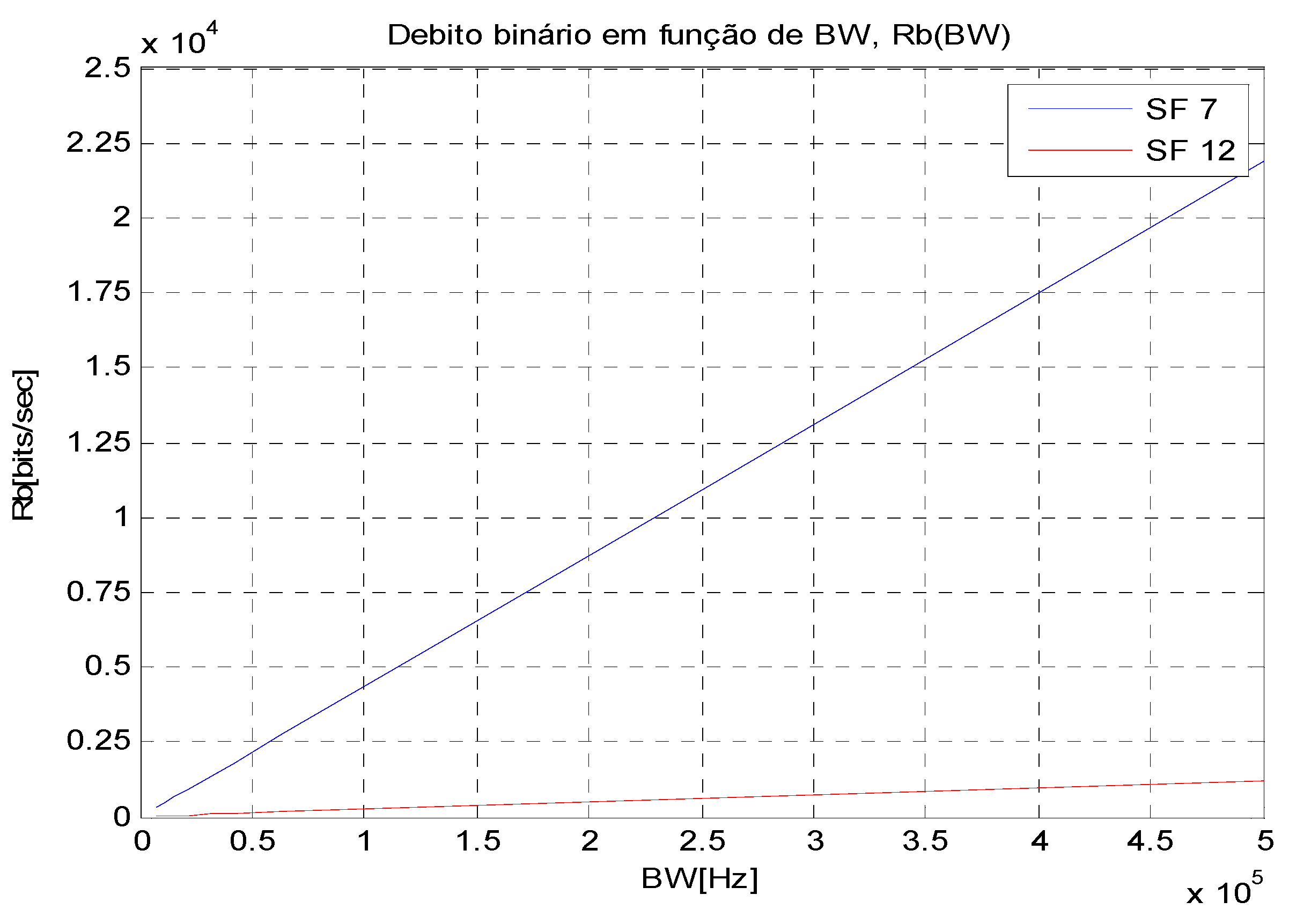

3.1.3. Bandwidth

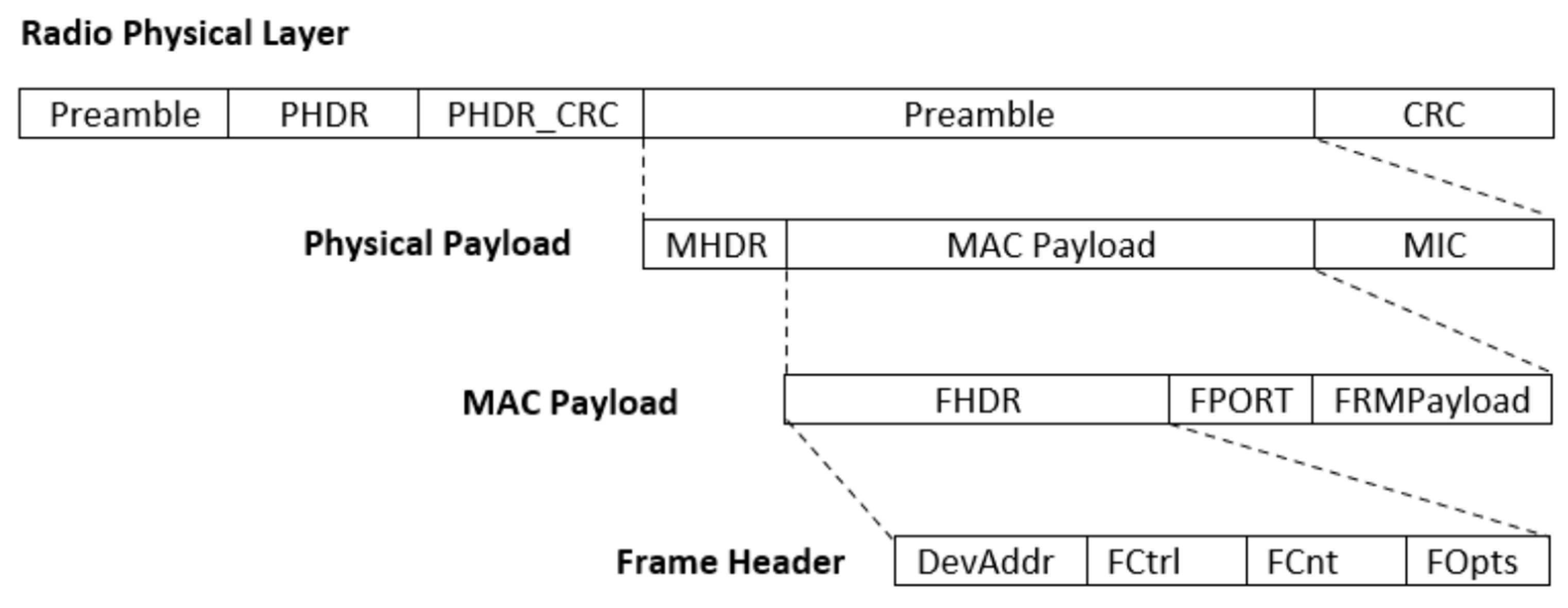

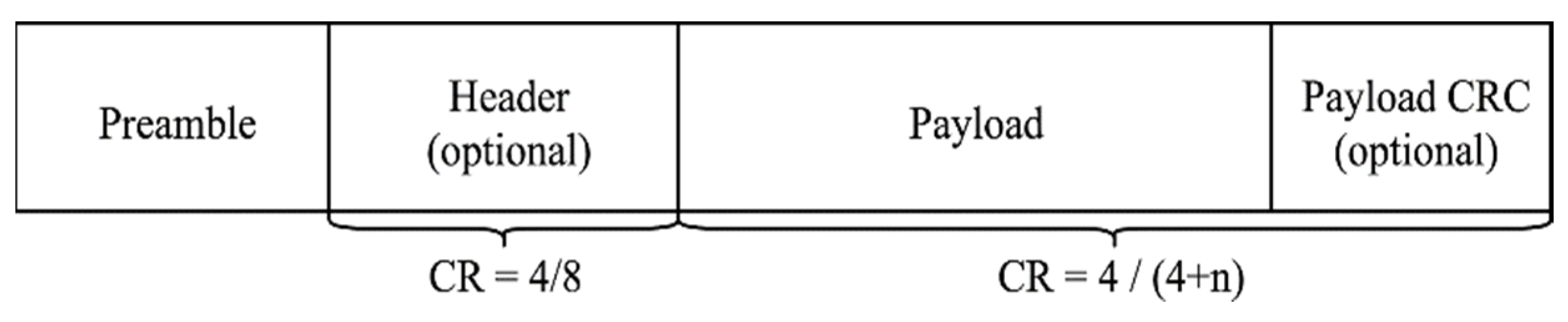

3.1.4. Frame Format and Duty Cycle

- ▪

- Preamble: Used to synchronize the receiver with the transmitter. It consists of 8 symbols for all regions, but the radio transmitter adds another 4.25 symbols, resulting in a final preamble length of 12.25 symbols.

- ▪

- PHDR (Physical Header): An (optional) field that contains information about payload size and CRC (Cyclic Redundancy Check). It’s only present in explicit mode.

- ▪

- PHDR_CRC (Header CRC): An (optional) field that contains an error detecting code for correcting errors in the header.

- ▪

- PHYPayload: Contains the complete frame generated by the MAC layer. The maximum payload size varies by Data Rate (DR) and is region-specific.

- ▪

- CRC: An (optional) field that contains an error detecting code for correcting errors in the payload of uplink messages.

- ▪

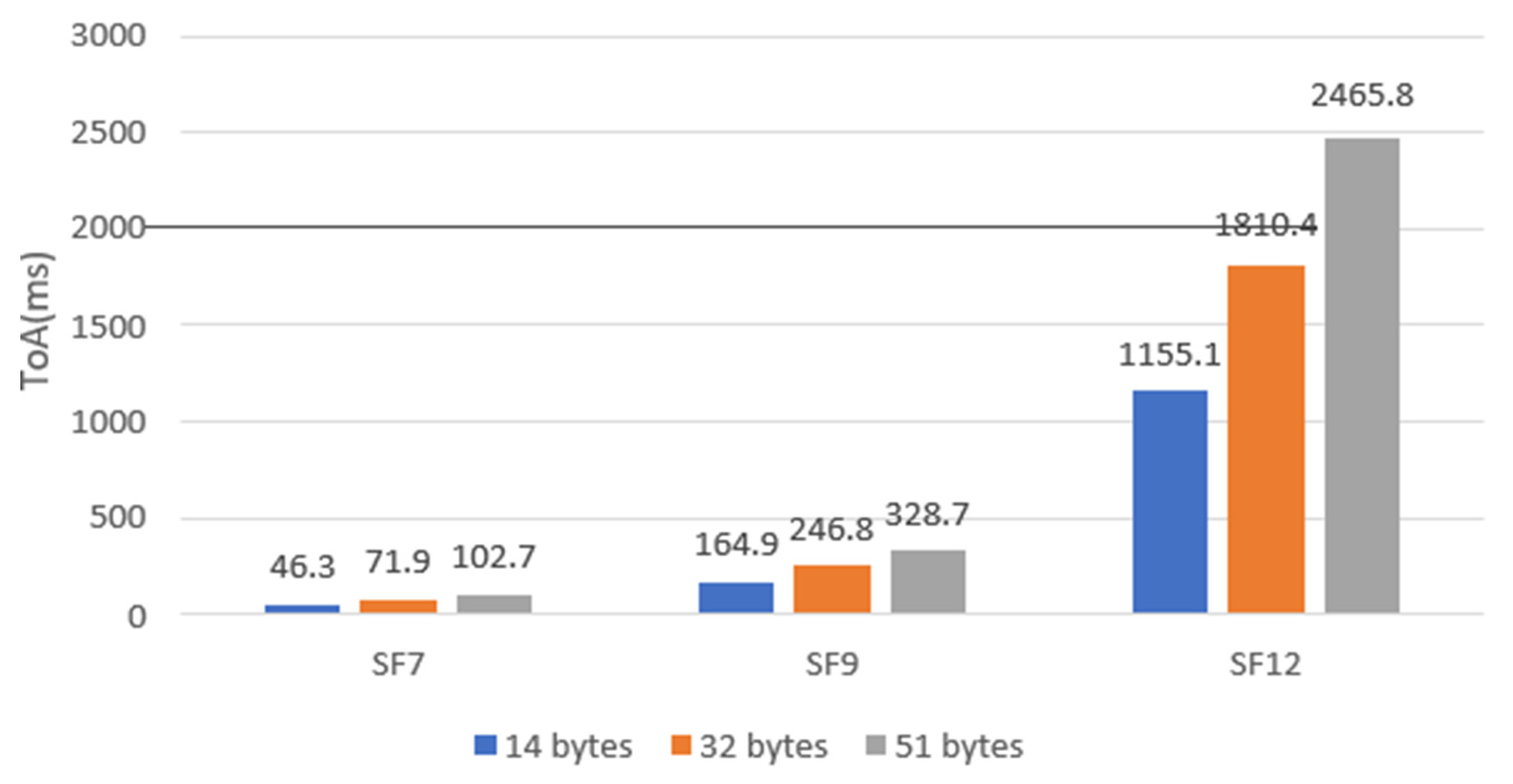

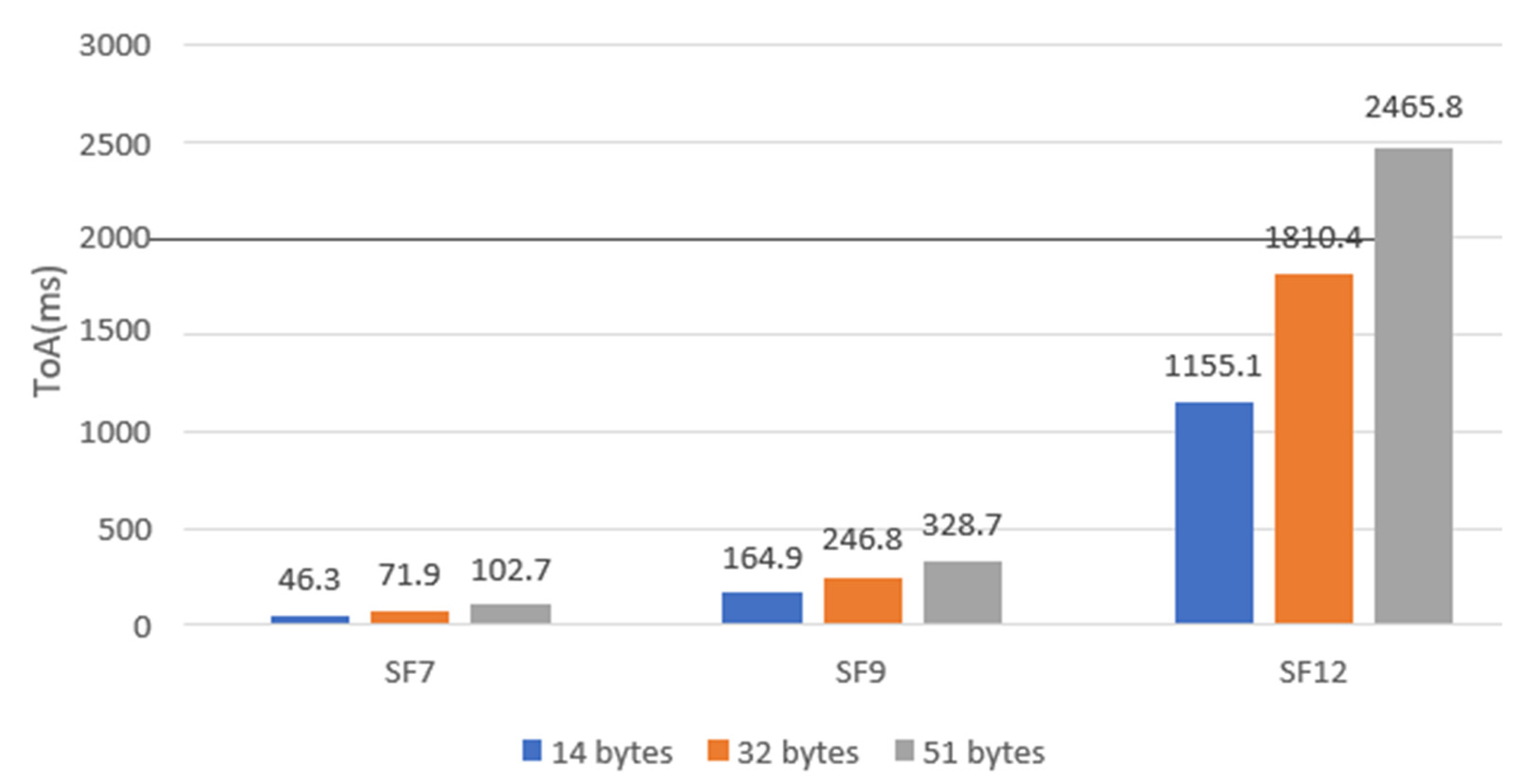

- Data Rate: The data rate in LoRa is determined by the bandwidth, coding rate, and spreading factor. A lower spreading factor provides a higher bit rate for a fixed bandwidth and coding rate. Therefore, for a fixed amount of data (payload), a higher spreading factor (lower data rate) needs a longer ToA.

- ▪

- Payload Size: The payload size directly affects the ToA. Sending a larger amount of data with a fixed bandwidth and spreading factor requires a longer ToA. This is because the data rate is fixed for a given bandwidth and spreading factor.

- ▪

- Network Traffic: In a network with high traffic, a longer ToA could increase the risk of packet collisions, leading to packet loss.

- ▪

- Interference: A longer ToA means the packet is in the air for a longer time, increasing the chance of interference from other signals.

3.2. RSSI-Received Signal Strength Indicator and SIR-Signal-to-Interference Ratio

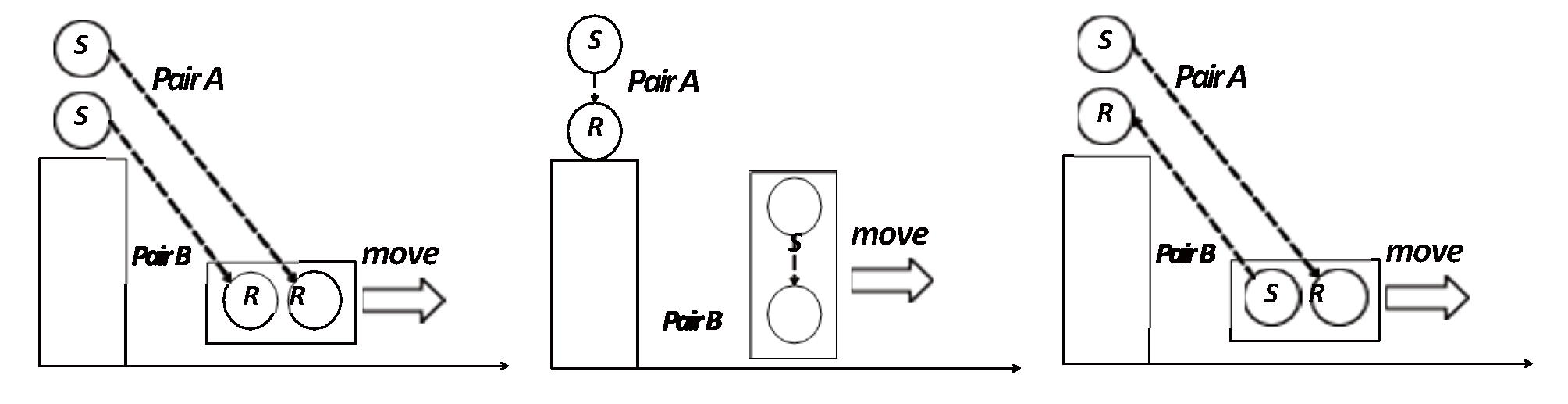

4. Collision Management and MAC Protocols in IoT Networks

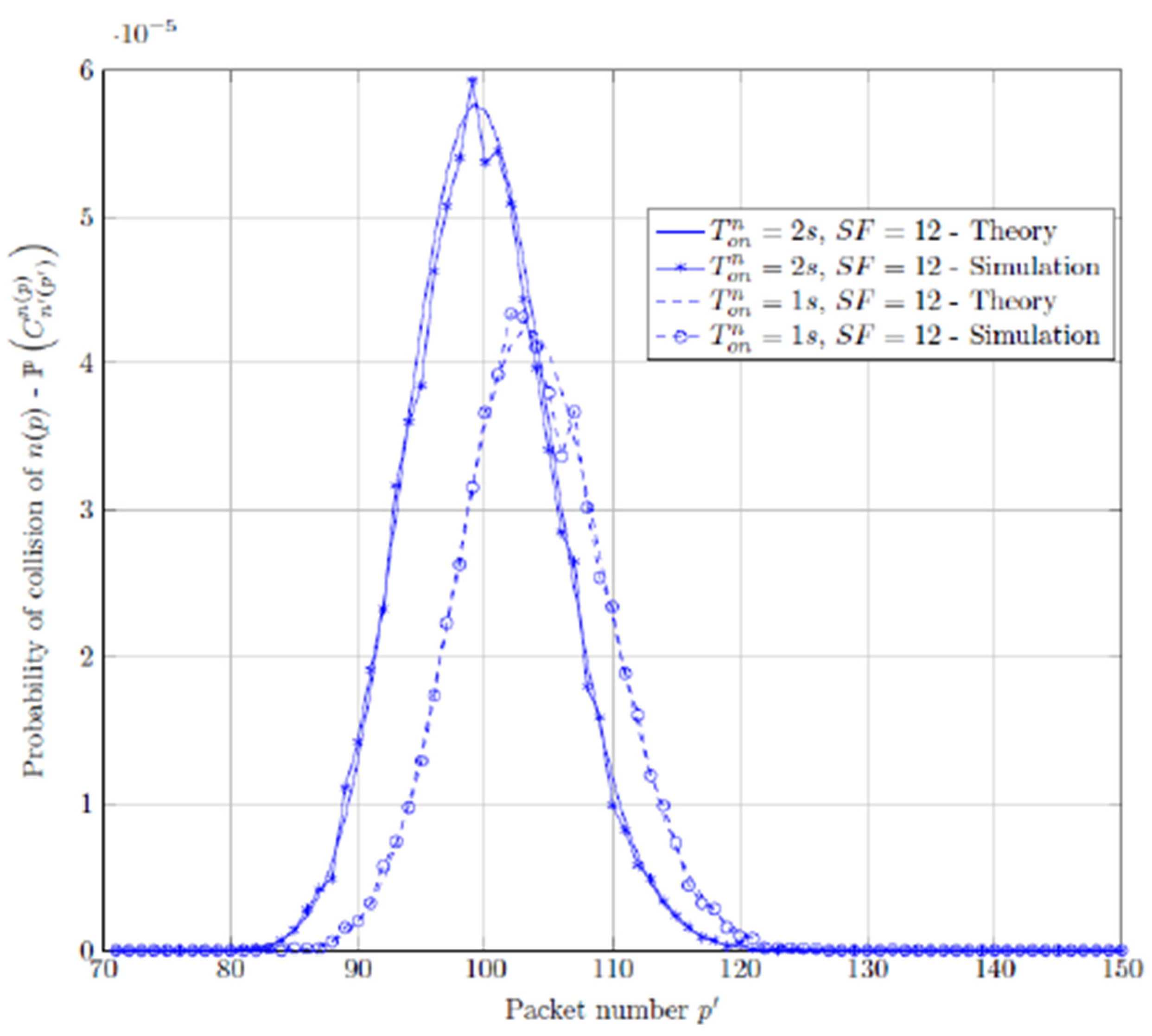

4.1. Collisions and Interference in LoRaWAN

- ▪

- Intra-SF interference may occur when more than one end-devices transmit with the same Spreading Factor (SF) on the same radio resource (bandwidth and channel frequency) and overlap in time and frequency. A received signal can be demodulated properly if the Capture effect happens [19].

- ▪

- Inter-SF interference may occur when transmissions using different Spreading Factors (SFs) overlap in time and frequency. The signals with a lower SF (higher data rate) can interfere with the signals with a higher SF (lower data rate), leading to packet loss [19].

- ▪

- Timing: If two packets with different SFs arrive at the receiver at the same time, they can interfere with each other and cause a collision.

- ▪

- Power: If a packet with a lower SF (which means it’s transmitted with higher power) is received at the same time as a packet with a higher SF (lower power), the stronger signal can drown out the weaker one, causing the packet with the higher SF to be lost (.

- ▪

- Doppler Effect: The Doppler effect can cause shifts in the frequency of the received signals, which can disrupt the orthogonality between different SFs and lead to packet collisions.

- ▪

- Data Integrity: Packet loss can lead to incomplete or incorrect data being received, which can affect the integrity of the data. This is particularly problematic in applications where accurate data is critical, such as health care applications.

- ▪

- Network Efficiency: Packet loss can reduce the efficiency of the network. When packets are lost, they often need to be retransmitted, which uses additional network resources and can lead to congestion.

- ▪

- Latency: Packet loss can increase latency, as lost packets need to be detected and retransmitted. This can be problematic in applications that require real-time data, such as control systems.

- ▪

- Application Performance: Depending on the application running on top of the LoRaWAN, packet loss can have varying degrees of impact. For example, in a temperature monitoring application, occasional packet loss might be tolerable, but in a fire alarm system, every packet is critical.

4.2. MAC Protocols

4.2.1. ALOHA Protocol

- ▪

- Allows any station to transmit data at any time without synchronization.

- ▪

- Collisions occur, and colliding frames are destroyed.

- ▪

- Feedback informs stations if their frames were successfully transmitted.

- ▪

- Maximum Efficiency: 18.4%

- ▪

- Divides time into discrete intervals called slots, each corresponding to a frame.

- ▪

- Stations synchronizes transmissions and transmit data only at the beginning of each slot.

- ▪

- This approach reduces collisions and improves overall efficiency compared to unslotted (Pure) Aloha.

- ▪

- Maximum Efficiency: 36.8%

5. Results and Discussion

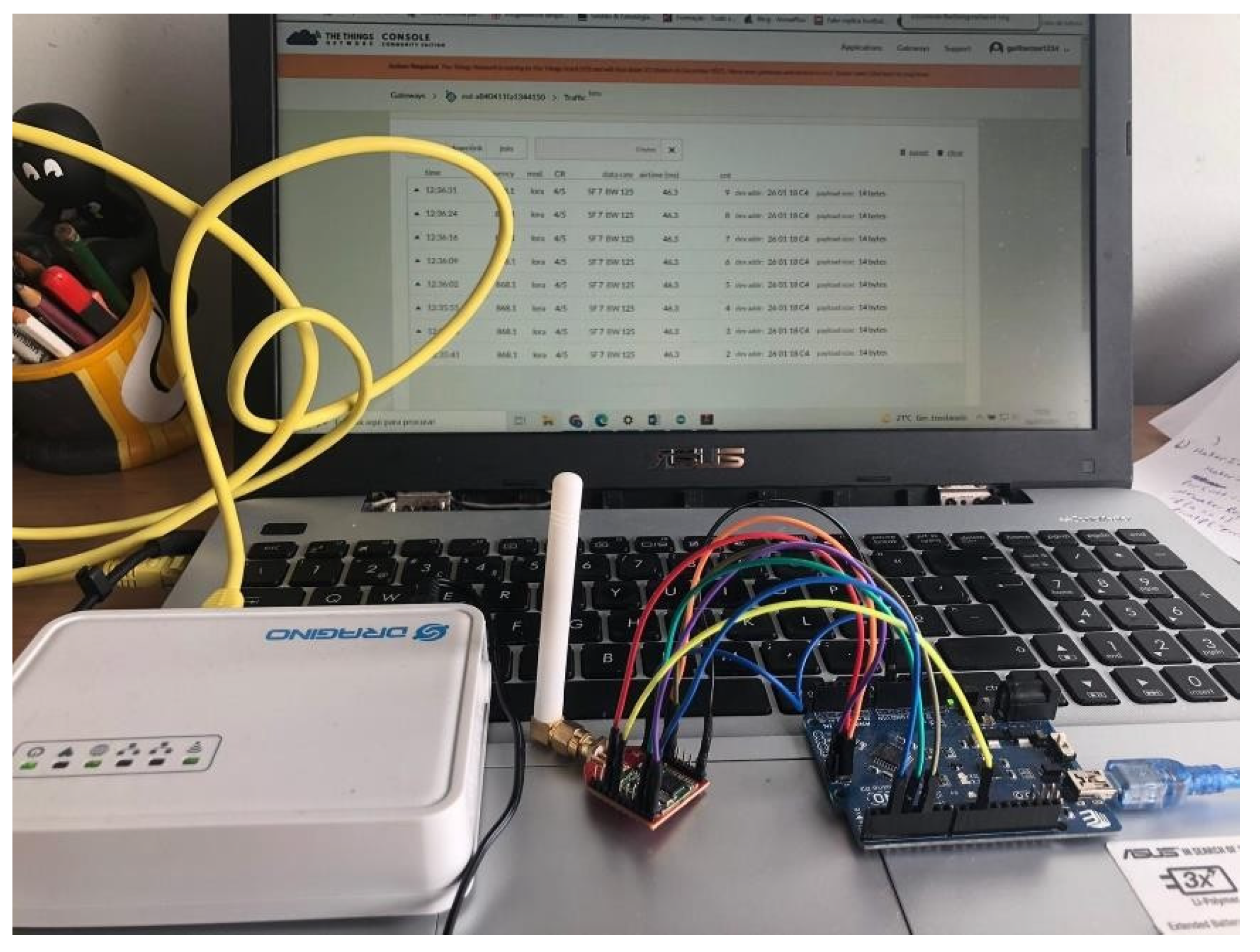

5.1. Hardware Used in this Experimental Study

- ▪

- Uplink Transmission: A Class A device can send an uplink message at any time. The uplink slot is scheduled by the end device itself based on its need.

- ▪

- Downlink Transmission: Once the uplink transmission is completed, the device opens two short receive windows for receiving downlink messages from the network. There is a delay between the end of the uplink transmission and the start of each receive window, known as RX1 Delay and RX2 Delay, respectively.

- ▪

- Low Power Consumption: Class A end devices have very low power consumption. Therefore, they can operate with battery power. They spend most of their time in sleep mode and usually have long intervals between uplinks.

- ▪

- High Downlink Latency: Class A devices have high downlink latency, as they require sending an uplink to receive a downlink.

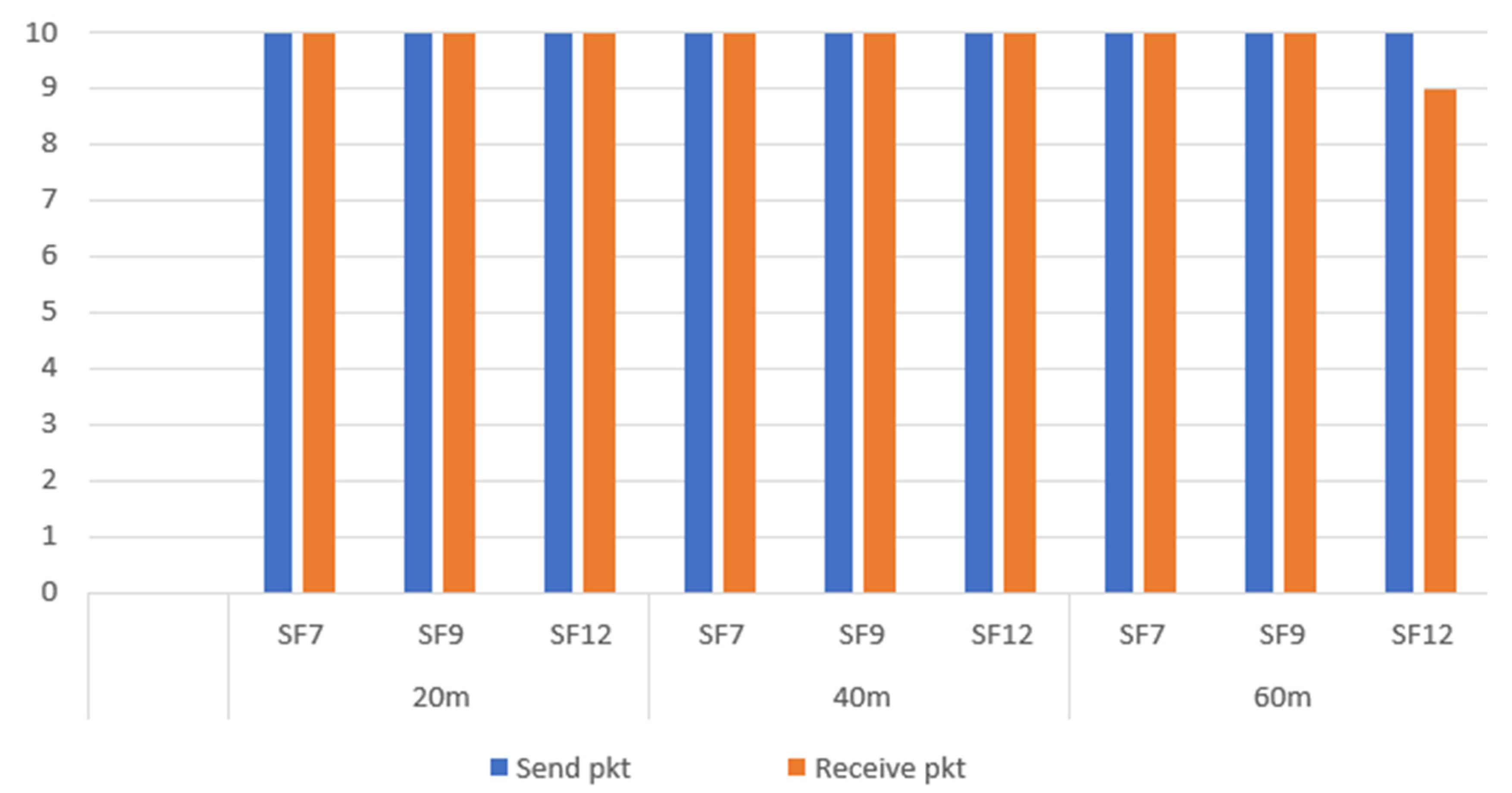

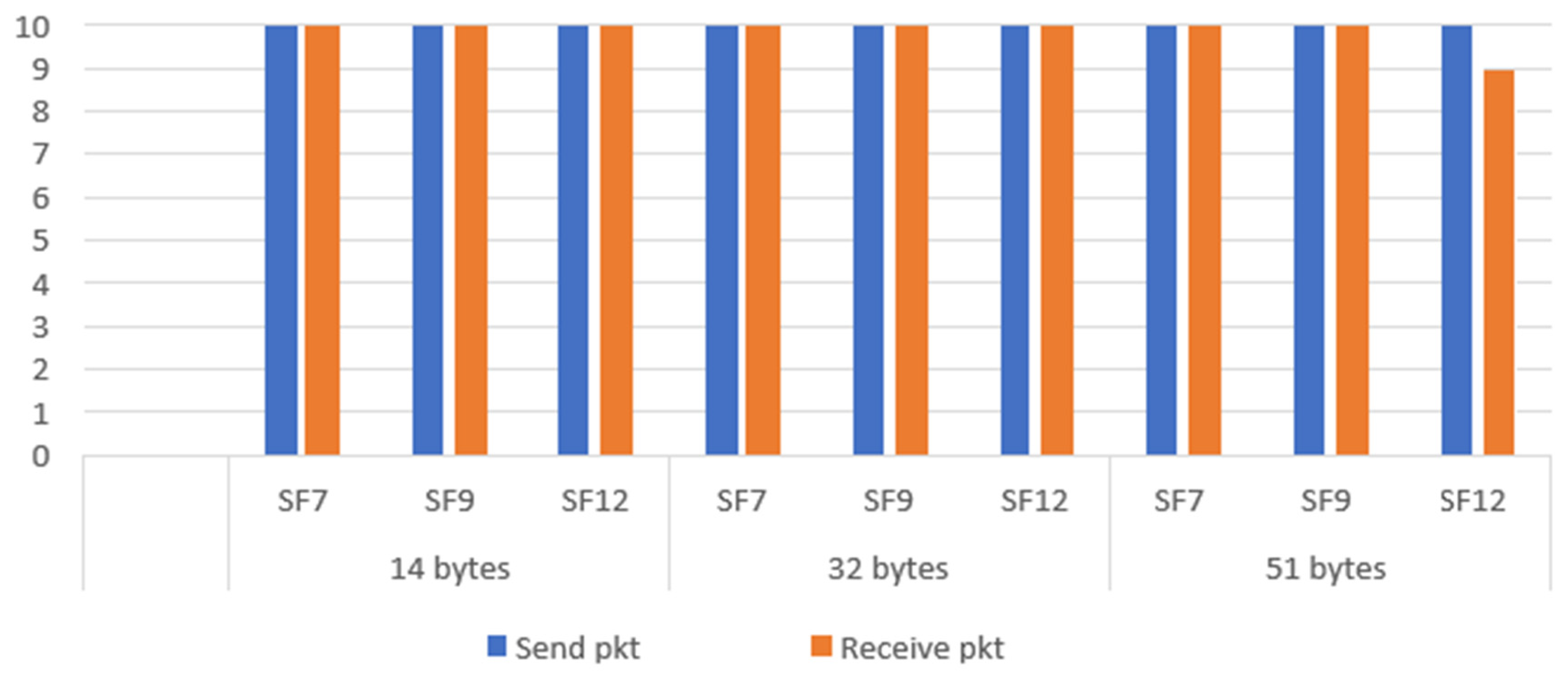

5.2. Experimental Test Scenarios

- ▪

- 20, 40 and 60 meters

- ▪

- 7, 9 and 12.

- ▪

- 14, 32 and 51 bytes.

- ▪

- Line of Sight (LOS).

- ▪

- Non-Line of Sight (NLOS), being vegetation the factor for signal absorption, scattering and attenuation.

- ▪

- Non-Line of Sight (NLOS), being a concrete wall the factor for fading and shadowing.

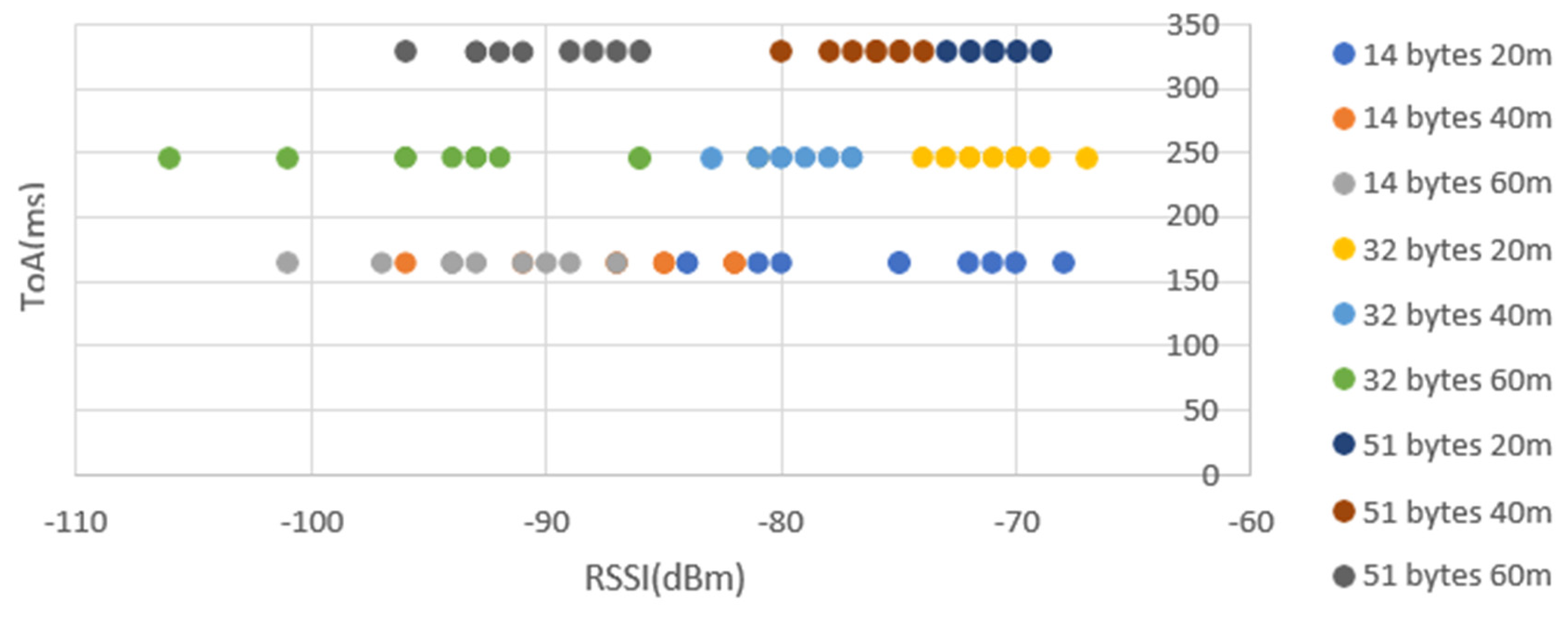

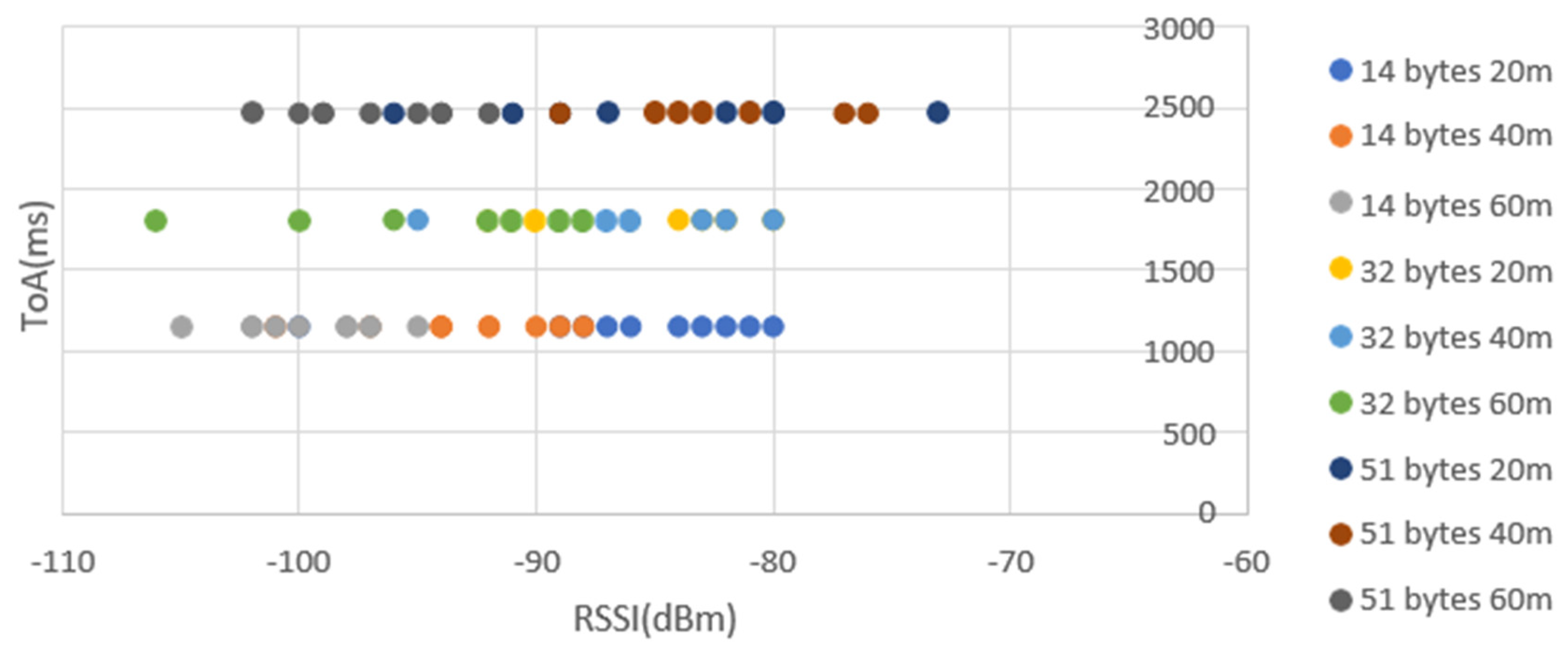

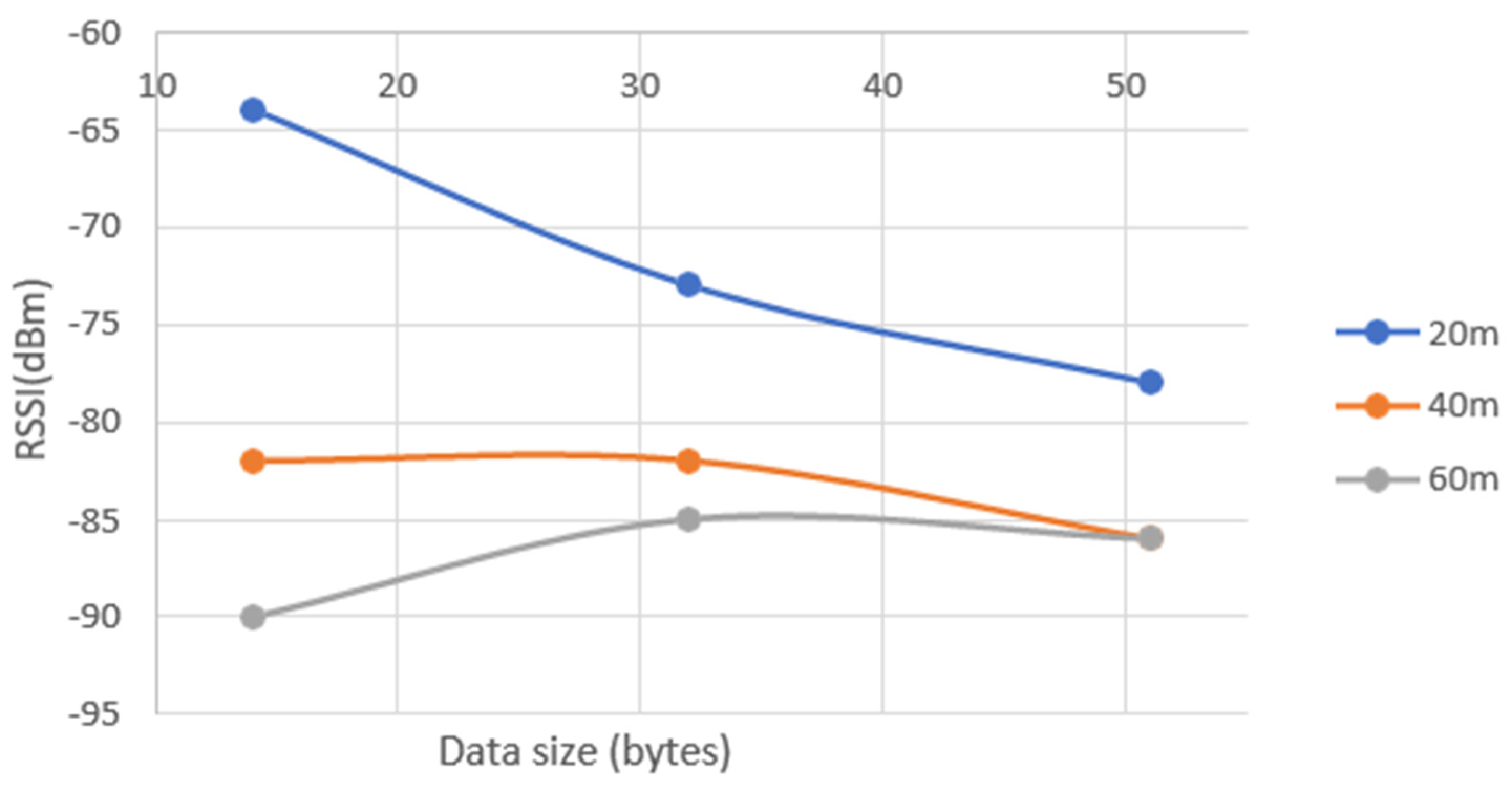

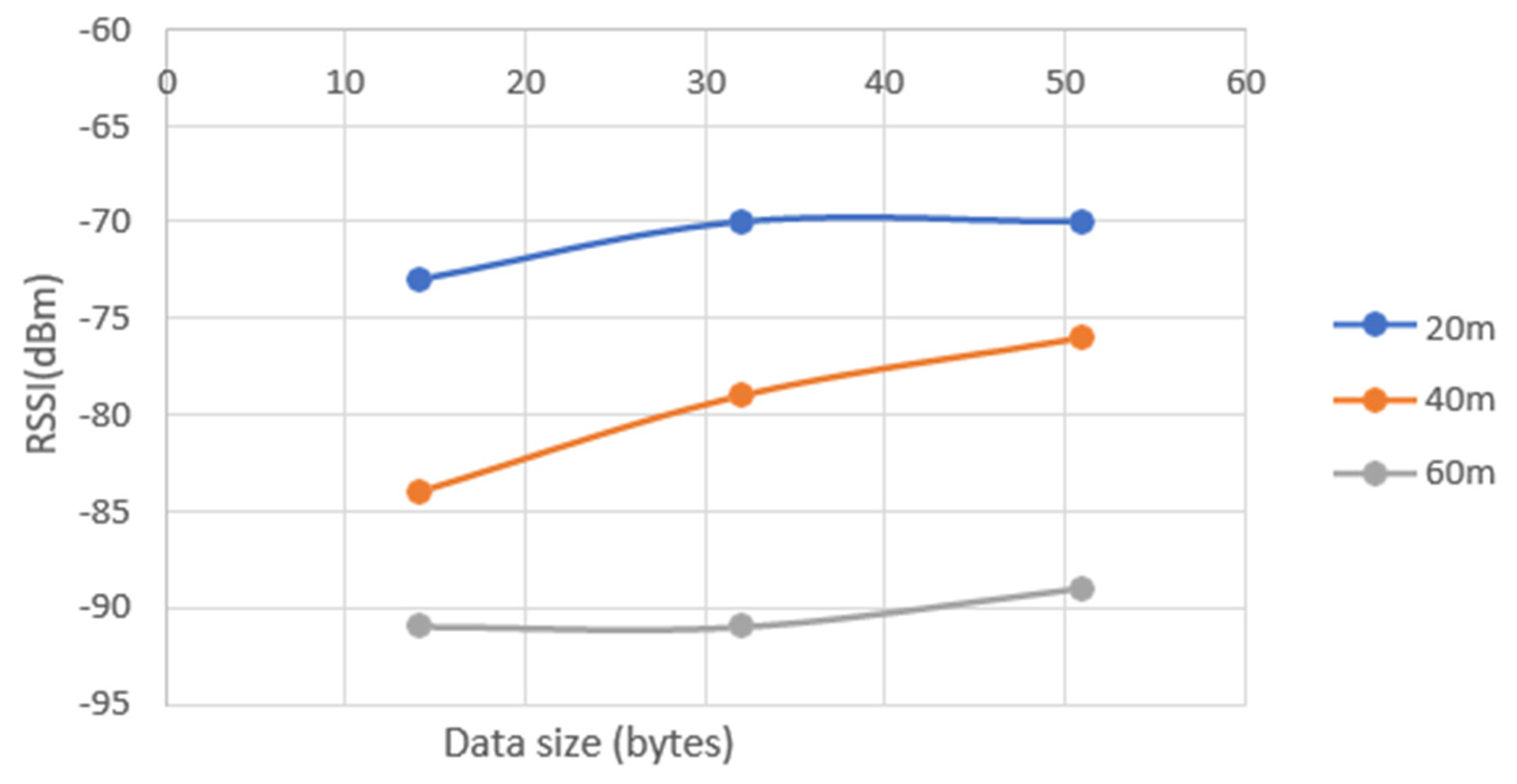

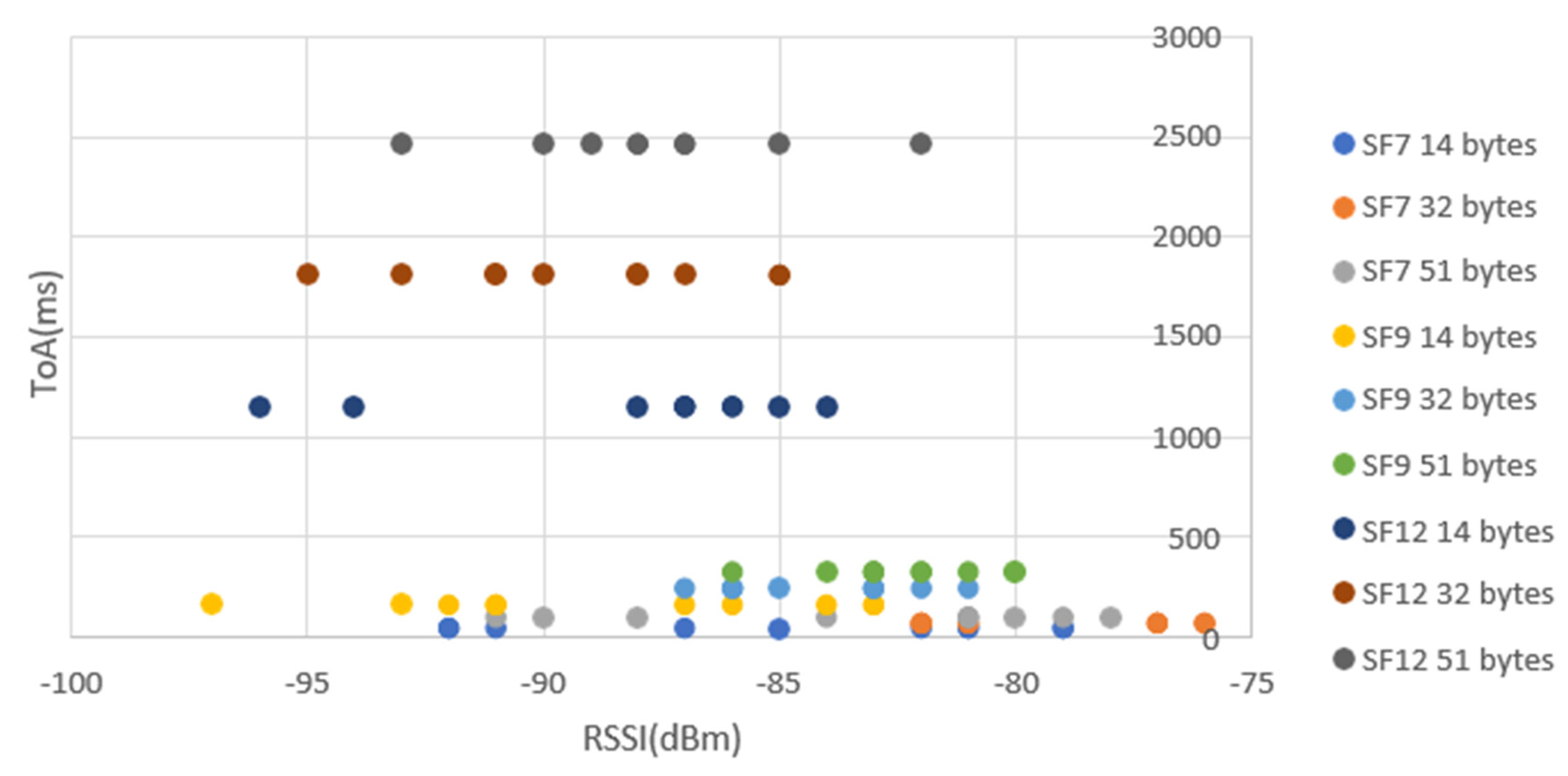

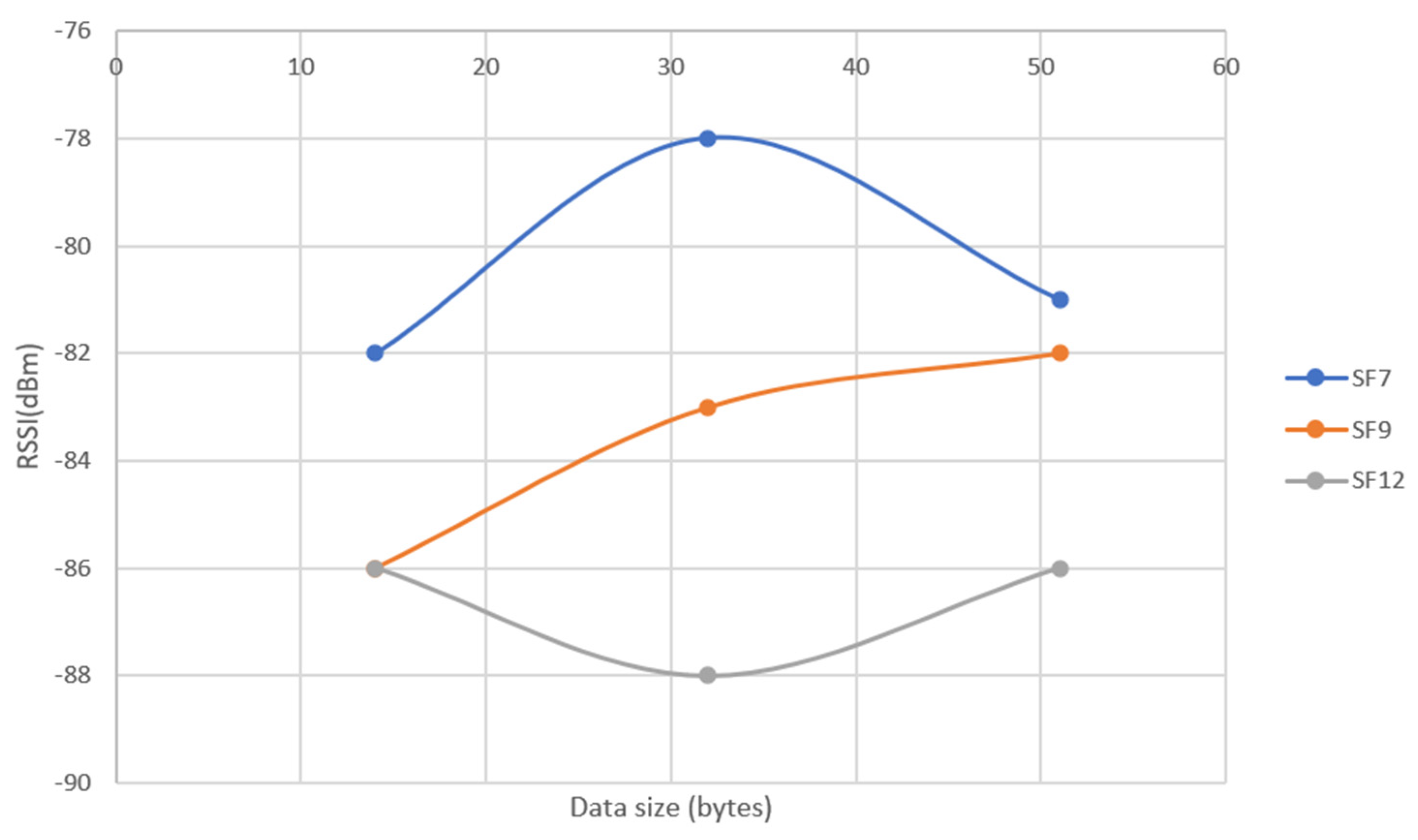

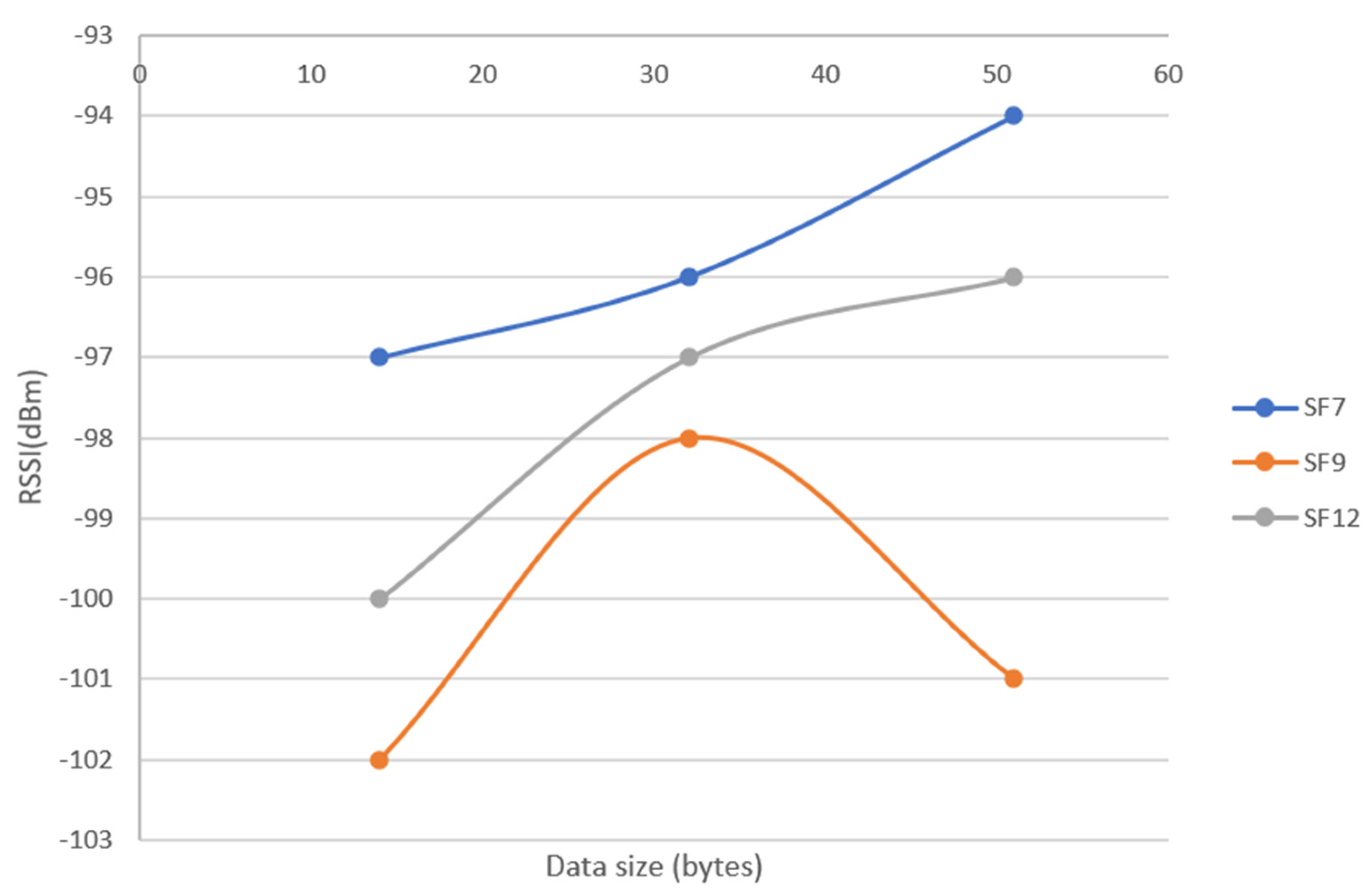

5.3. LOS Results

- ▪

- 20m: Highest value for Sf=7 with 14 Bytes (-63 dBm). Lowest for (also) SF=7 and 51 Bytes (-91 dBm).

- ▪

- 40m: Highest value for SF=9 with 51 Bytes (-74 dBm). SF=12 with 51 bytes also achieves a good result at this distance (-76 dBm). Lowest for SF=7 with 51 Bytes (-106 dBm). Yet this value it’s just for one packet. In all the other 9 the worst value was -89 dBm.

- ▪

- 60m: Highest value for SF=7 with 32 Bytes (-82 dBm). Lowest for both SF=9 with 12 and 32 Bytes (-106 dBm).

- ▪

- SF7 has the best result of RSSI for 14 bytes at 20m (-63 dBm) and the worst for 51 bytes at 60m (-95 dBm).

- ▪

- SF9 has the best result for 32 bytes at 20m (-67 dBm) and the worst for 32 bytes at 60m (-106 dBm). Yet this value it’s just for one packet while the worst of the other 9 packets was -96 dBm.

- ▪

- SF12 has the best result for 20m (-73 dBm) and payload of 51 bytes and the worst for 14 bytes at 60m (-106 dBm). Yet, 8 of the 10 packets were higher than -102 dBm.

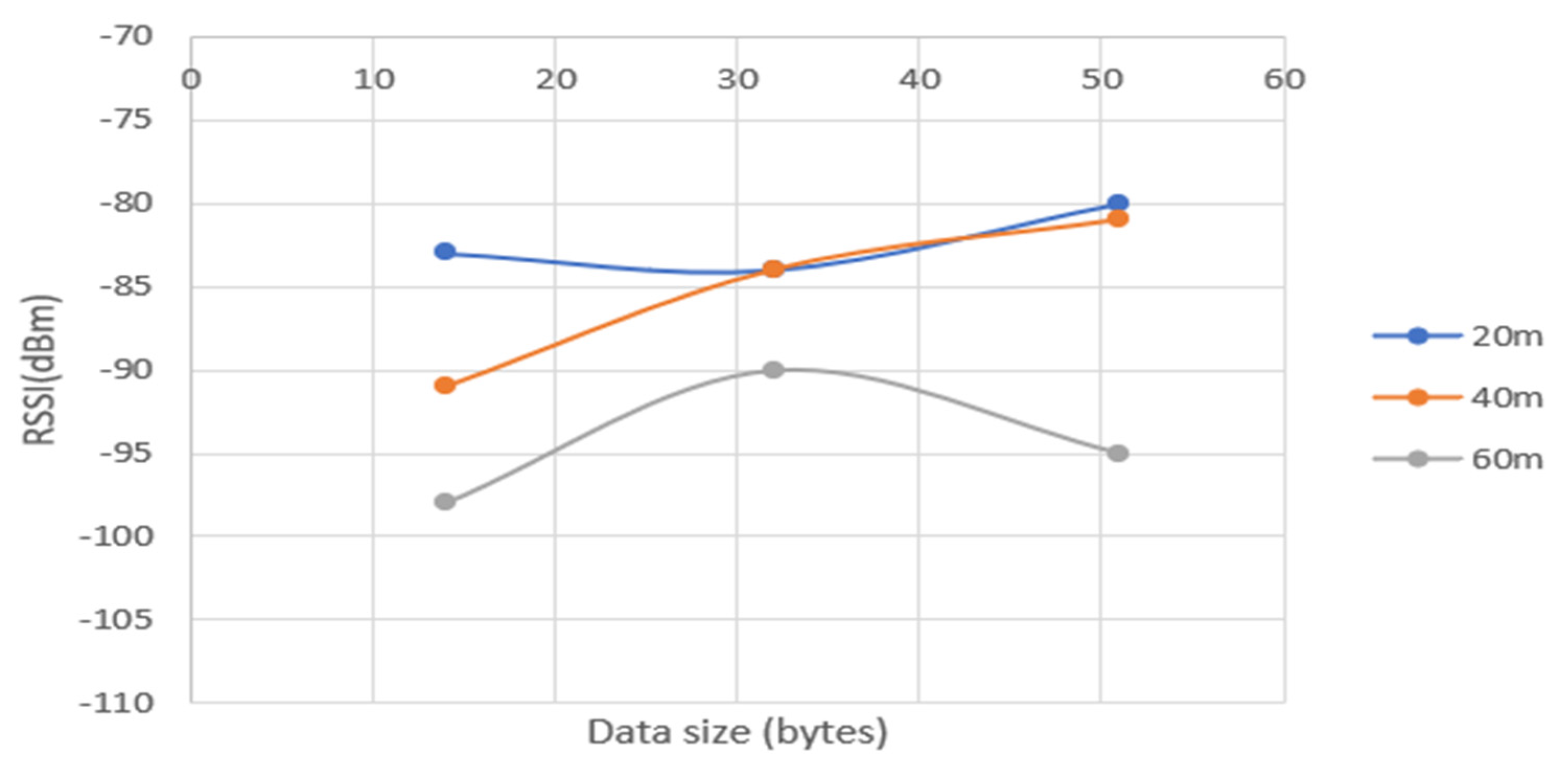

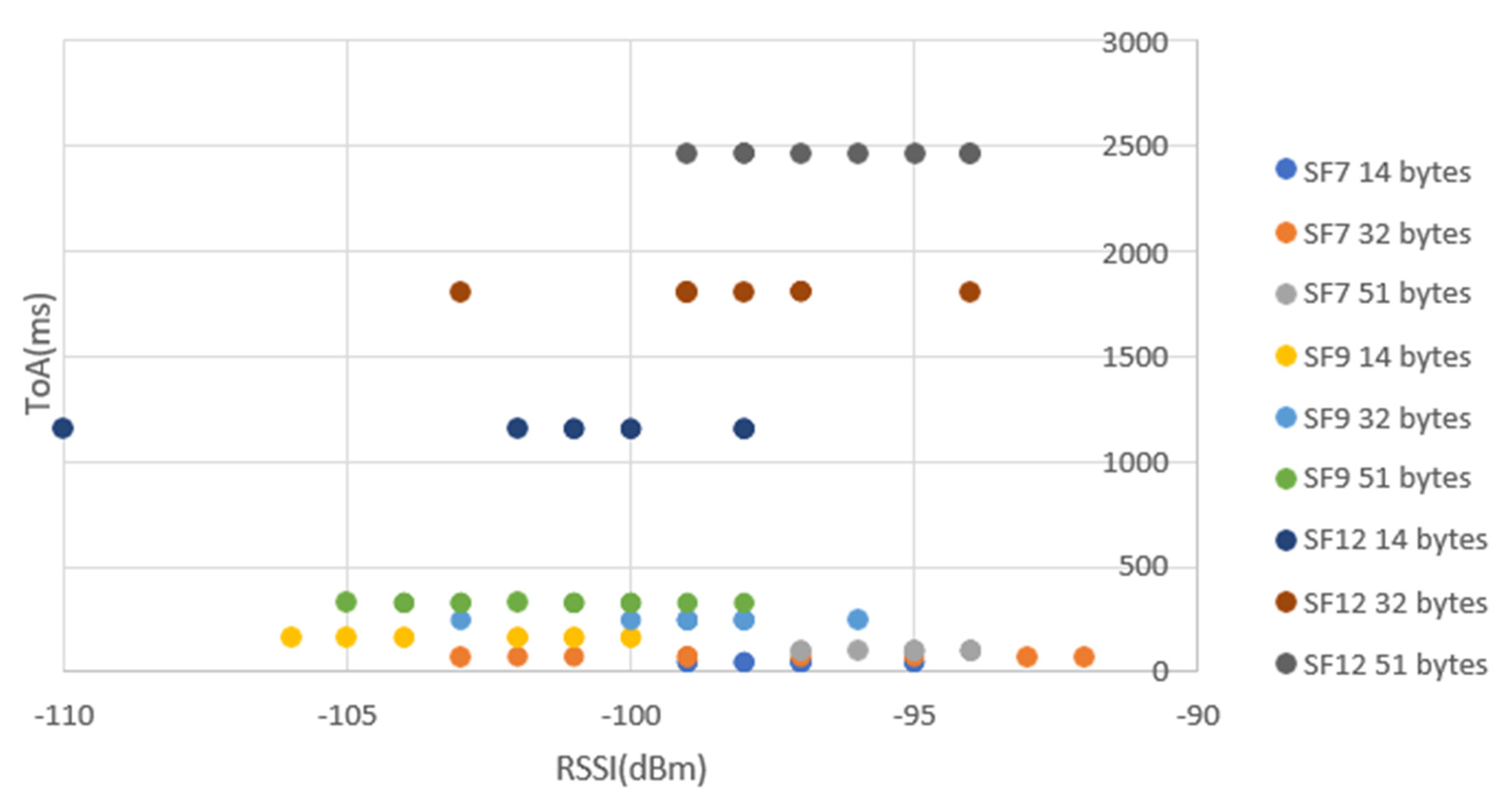

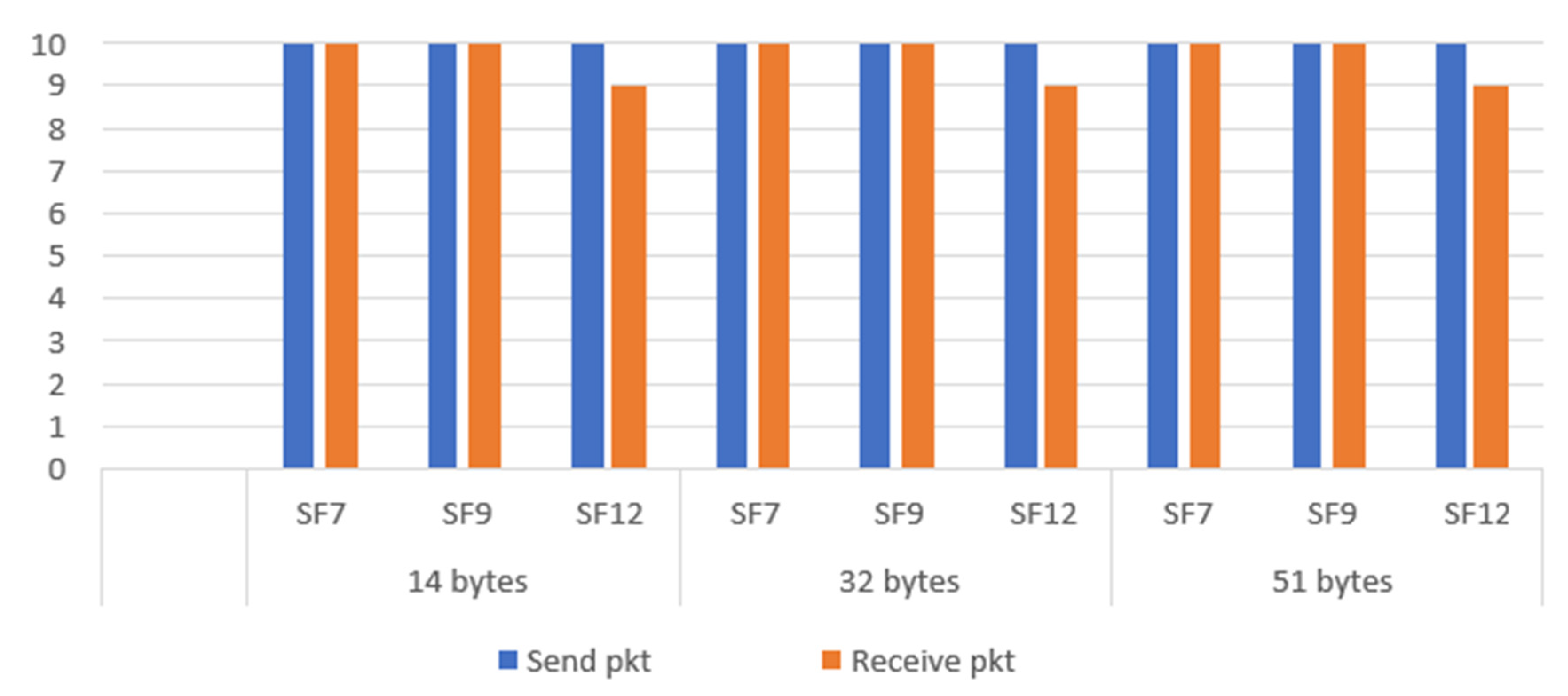

5.4. NLOS Results

6. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andri Rahmadhani and Fernando Kuipers (Del. University of Technology), “Understanding collisions on LoRaWAN”, Conference: the 12th International Workshop, pag.1, 2018.

- Daniele Croce, Michele Gucciardo, Stefano Mangione, Giuseppe Santaromita, Ilenia Tinnirello, “Impact of LoRa Imperfect Orthogonality:Analysis of Link-level Performance”. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319486965_Impact_of_Spreading_Factor_Imperfect_Orthogonality_in_LoRa_Communications, (accessed 17/05/2024).

- Oracle - “What is IoT?”. Available online: https://www.oracle.com/internet-of-things/what-is-iot/ (accessed on 21/03/2024).

- Yuya Ishida, Daiki Nobayashi, Takeshi Ikenaga, “Experimental Performance Evaluation of the Collisions in LoRa Communications”, 2018 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI).

- G. Ferré. Collision and packet loss analysis in a LoRaWAN network. 25th Eur. Signal Process. Conf. EUSIPCO 2017, vol. 2017-January, pp. 2586–2590, 2017.

- Semtech Corporation, “AN1200.22 LoRa™ Modulation Basics”, May 2015.

- LoRa Alliance. Available online: https://lora-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/what-is-lorawan.pdf, (accessed 9/4/2024).

- Semtech. Available online: https://Semtech Blog: LoRa Delivers Internet of Things Capabilities Worldwide, (accessed on 17/05/2024).

- Rakwireless. Available online: https://news.rakwireless.com/lora-css-vs-lora-fhss/, (accessed on 17/05/2024).

- Semtech Corporation, “LoRa® and LoRaWAN®: A Technical Overview”, December 2019 (accessed 17/05/2024).

- 11. K. Olsson and S. Finnsson, Exploring LoRa and LoRaWAN: A suitable protocol for IoT weather stations?, Master’s Thesis, Department of Electrical Engineering, Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, 2017.

- T. Elshabrawy e J. Robert, “Evaluation of the BER Performance of LoRa Communication using BICM Decoding”, 2019 IEEE 9th International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE-Berlin), p.162-167, 2019.

- LoRa. Available online: https://lora.readthedocs.io/en/latest/, (accessed 18/5/2024).

- The Things Network. Available online: LoRa Physical Layer Packet Format | The Things Network, (accessed 17/5/2024).

- The Things Network. Available online: https://www.thethingsnetwork.org/docs/lorawan/spreading-factors/, (accessed 17/5/2024).

- Courjault, J.; Vrigenau, B.; Berder, O.; Bhatnagar, M. A Computable Form for LoRa Performance Estimation: Application to Ricean and Nakagami Fading. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 81601–81611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.F.; Lima, E.R.D.; Fraidenraich, G. Bit error rate closed-form expressions for LoRa systems under Nakagami and Rice fading channels. Sensors 2019, 19, 4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claire Goursaud, Jean-Marie Gorce, “Dedicated networks for IoT: PHY / MAC state of the art and challenges”. Available online https://hal.science/hal-01231221, (accessed 18/05/2024).

- Poonam Maurya, Aatmjeet Singh and Arzad Alam Kherani “A review: spreading factor allocation schemes for LoRaWAN”, May 2022, available online. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11235-022-00903-4, (accessed on 17/05/2024).

- N. Abramson and F.F. Kuo, Eds., Computer-Communication Networks, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Chapter 13, 1973.

- R. Metcalfe, Steady state analysis of a slotted and controlled ALOHA system with blocking, Proc. 6th Hawaii Int. Conf. Sys. Sci., January, 1973.

- Dragino. Available online: https://www.dragino.com/ (accessed on 9/4/2024).

- Arduino. Available online: https://www.arduino.cc/ (accessed on 11/3/2024).

- Semtech Corporation. Available online: https://www.semtech.com/products/wireless-rf/lora-connect/sx1276#features, (accessed 09/04/2024).

- The Things Network. Available online: https://www.thethingsnetwork.org/ (accessed on 23/2/2024).

| SF | Chips per chirp | ||

| 7 | 976,56 | 128 | 125000 |

| 8 | 488,28 | 256 | 125000 |

| 9 | 244,14 | 512 | 125000 |

| 10 | 122,07 | 1024 | 125000 |

| 11 | 61,04 | 2048 | 125000 |

| 12 | 30,52 | 4096 | 125000 |

| Interferer SF | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Desired SF | ||||||

| 7 | -6 | 16 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 20 |

| 8 | 24 | -6 | 20 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| 9 | 27 | 27 | -6 | 23 | 25 | 25 |

| 10 | 30 | 30 | 30 | -6 | 26 | 28 |

| 11 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | -6 | 29 |

| 12 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | -6 |

| SF | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| BW | ||||||

| 125 kHz | −123 | −126 | −129 | −132 | −133 | −136 |

| 250 kHz | −120 | −123 | −125 | −128 | −130 | −133 |

| 500 kHz | −116 | −119 | −122 | −125 | −128 | −130 |

| SF | 7,9,12 |

| Distance | 20, 40, 60 m |

| Emitting Power | 8 dBm |

| Frequency | 868.2 MHz |

| Data size | 14, 32, 51 bytes |

| Code Rate | 4/5 |

| Bandwidth | 125 kHz |

| Duty Cycle | 1% |

| Time between messages | 1 s |

| SF | 7,9,12 |

| Distance | 60 m |

| Emitting Power | 8 dBm |

| Frequency | 868.2 MHz |

| Data size | 14, 32, 51 bytes |

| Code Rate | 4/5 |

| Bandwidth | 125 kHz |

| Duty Cycle | 1% |

| Time between messages | 1 s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).