Submitted:

06 June 2024

Posted:

07 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

- primary ingestion of spent lead ammunition (shot) and fishing tackle as gastroliths by waterfowl; ECHA estimates2 that at least 135 million birds are currently at risk of lead poisoning each year from primary ingestion of lead (including 7 million from the ingestion of lead fishing tackle);

- -

- secondary ingestion where predators eat animals that have been wounded with lead ammunition; ECHA estimates2 that 14 million birds are at risk of poisoning from secondary ingestion each year after inadvertently eating fragments of lead that are in the tissues of their food.

- -

- 1–12% in North America, with a maximum of 17,5% (the total number of birds — 171 697);

- -

- 2.5–12% in Europe, with a maximum of 23–31% (the total number of birds — 75 761).

- -

- determining the ratio of the concentration of contaminants (accessible for assimilation) dissolved in the gastric juice to their content in the solid phase (metal/soil) according to physiologically based tests of bioaccessibility[4]in vitro, imitating the conditions of the GI tract in laboratory conditions;

- -

- determining the ratio of the concentration of contaminants in blood to their concentration in the GI tract according to an assessment of bioavailability[5] in vivo, where the contaminants are introduced into the body of tested animals directly in natural form, as part of a liquid, or as part of a food matrix.

- -

- the bioaccessibility value which gives a general indication of the percentage of metal (Pb and Fe) that can be assimilated by a biological object (the recipient);

- -

- thresholds of the element concentration in the GI tract (according to the absence of toxic effects) obtained using the model calculations based on the bioaccessibility value and reference values for waterfowl.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Shot Collection

2.2. Soil

2.3. Bioaccessibility Tests

3. Results

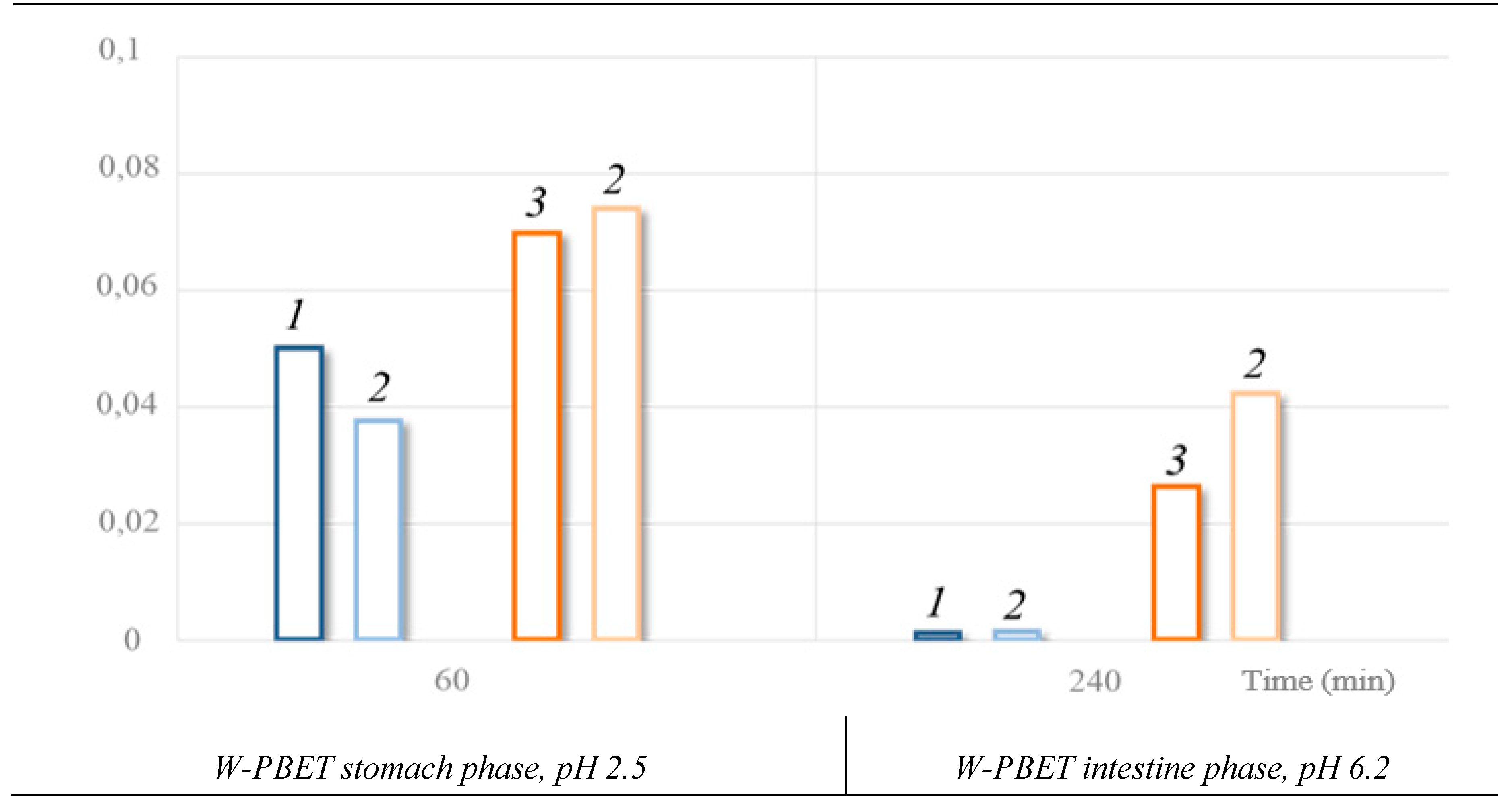

Pb bioaccessibility:

- -

- when lead shot is exposed alone the bioaccessible Pb in the stomach is 0.05% of the shot mass; in the intestine is 0.011 % of the shot mass, it is 5 times lower.

- -

- when lead and steel shot are exposed together Pb bioaccessibility decreases by 1.3 times in the stomach, while the percentage of bioaccessible Pb in the intestine is negligible.

Fe bioaccessibility:

- -

- when steel shot is exposed alone the bioaccessible Fe in the stomach is 0.07% of the shot mass; in the intestine is 0.025% of the shot mass, it is 3 times lower;

- -

- when lead and steel shot are exposed together Fe bioaccessibility remains almost the same in the stomach, while in the intestine, it increases by 1.7 times.

- -

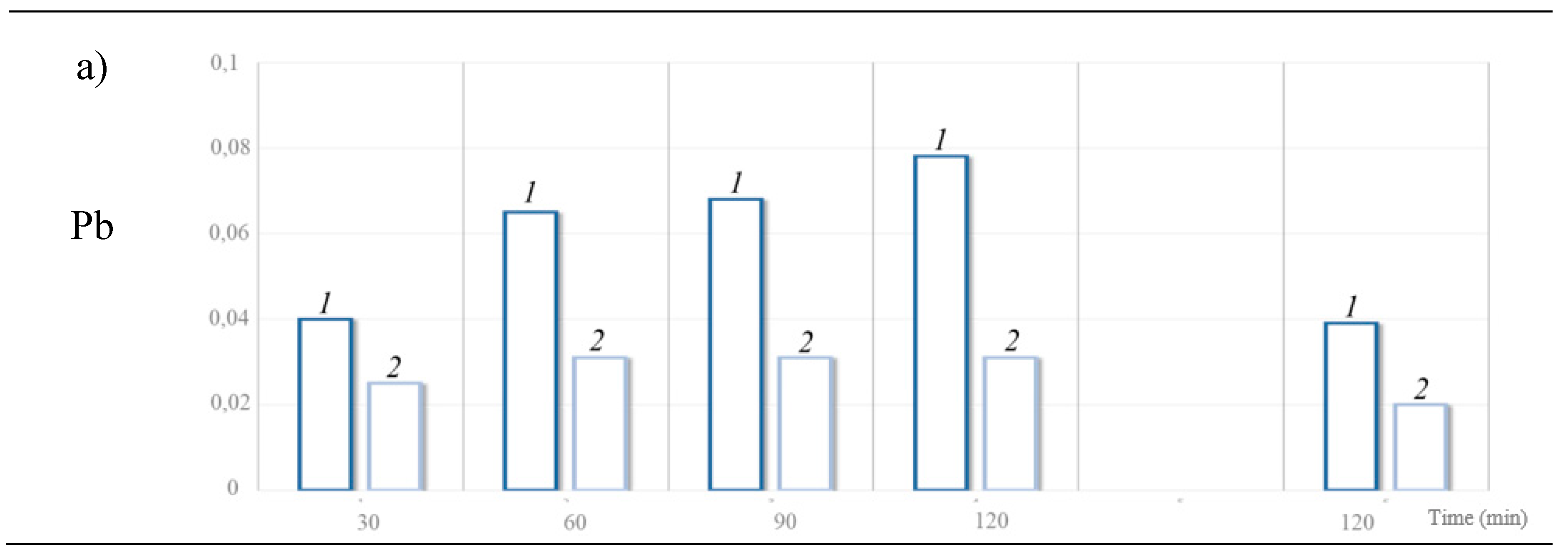

- when lead shot is exposed alone in the GI tract, Pb bioaccessibility reaches 0.08% of the mass of metal in the stomach and decreases to 0.04% of the metal mass in the intestine;

- -

- when lead and steel shot are exposed together in the stomach and intestine solutions, the percentage of bioaccessible Pb decreases and remains within 0.03% and 0.02% of the metal mass respectively.

- -

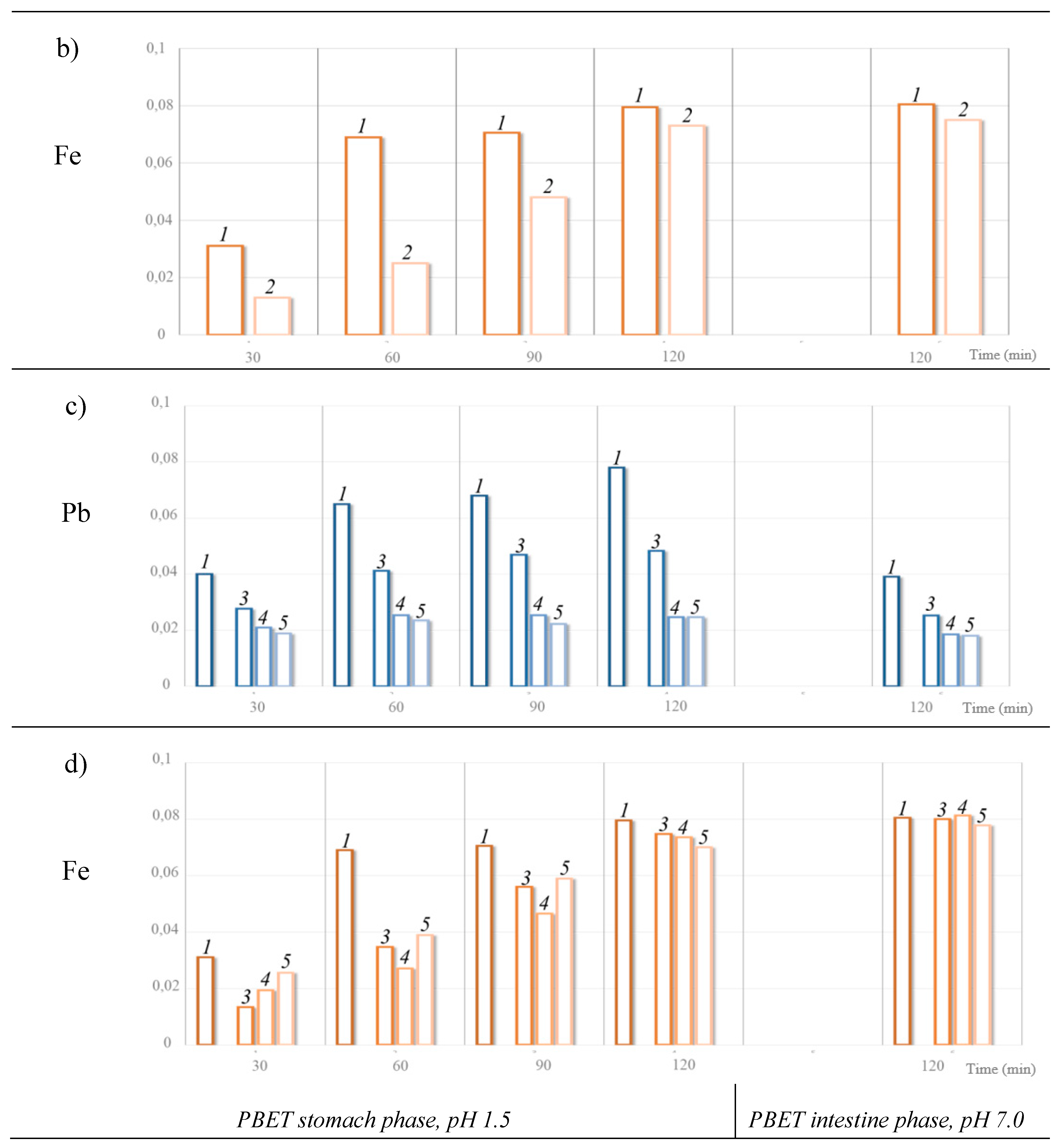

- for the variable mixtures of lead and steel shot in the GI tract (Figure 2c), regardless the ratio of shot mass, the Pb bioaccessibility is permanently and stably lower than when lead shot is exposed alone in the GI tract. As the percentage of steel shot in the mix increases, Pb bioaccessibility decreases by 2 or 3 times and is around 0.02% of the mass of metal in both the stomach and the intestine.

- -

- when steel shot is alone in the GI tract, the percentage of bioaccessible Fe is 0.08% of the mass of shot in all sections of the GI tract;

- -

- when lead and steel shot are together, the Fe bioaccessibility at the early stage of interaction with the gastric solution is two times lower, but by the end of the stomach stage bioaccessible Fe increases and stabilizes in the intestine at the 0.08% of the metal mass.

4. Discussion

- Blood Pb threshold (mg/l): for mammals (humans) – 0.05, for waterfowl – 0.2 (Franson and Pain, 2011) (1)

- Reference average duck mass (kg) – 1.3 (according to Finley et al., 1976; Rocke&Samuel, 1991; Plouzeau et al., 2011; Lewis et al., 2021) (2)

- Reference average blood volume (L) in humans – 5.012, in waterfowl – 0.13 (10% of duck mass (Portman et al., 1952)). (3)

- It is known that 3–10% of the ingested lead is absorbed in the GI tract; once absorbed, lead is initially bound to the blood erythrocytes (WHO, 2022). The authors of this paper have accepted the value of 10% for calculation. (4)

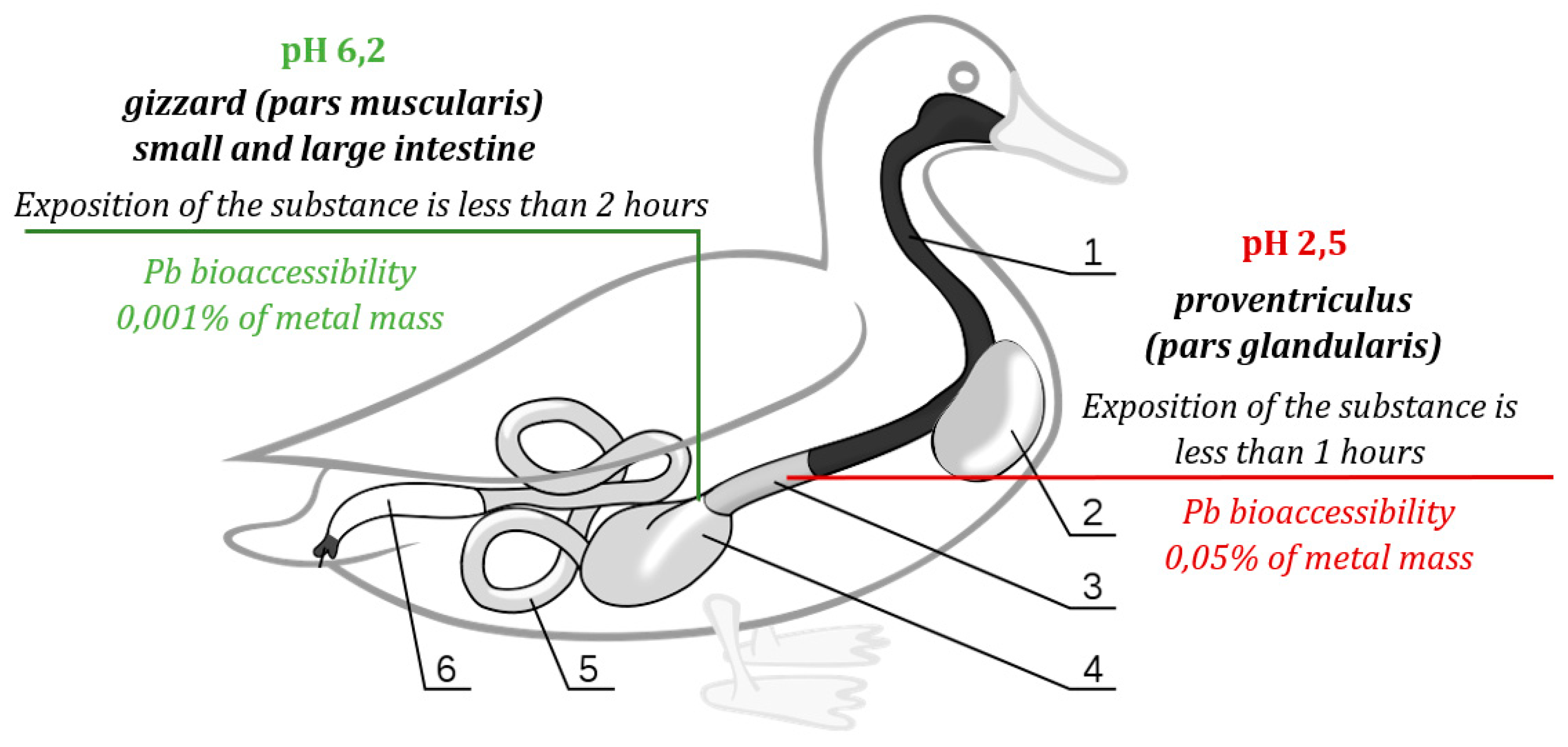

- Pb bioaccessibility in the stomach (hereinafter referred to as the maximum bioaccessibility) defines the maximum Pb amount soluble in the GI tract (Bosso and Enzweiler, 2007), while Pb bioaccessibility in the intestine (hereinafter referred to as the actual bioaccessibility) defines the lead amount that can be assimilated as it is known that the majority of GI content, including Pb, is absorbed by the small intestine (Denbow, 2000), after the food is processed in the stomach chambers (Figure 4). (5)

5. Conclusions

- -

- it is incorrect to equate the fact of metallic shot ingestion with toxic effects; the analysis of a considerable number of publications on the effects of lead on waterfowl over the past 20 years shows that birds can feel well at various blood lead concentrations, including high levels (up to 1 mg/l);

- -

- Pb as metal has been shown to have low bioaccessibility in the GI tract of waterfowl (and mammals) (even in the presence of metallic Fe);

- -

- using the model suggested by the authors, it has been shown that there is low probability of toxic effects on waterfowl due to the fact that is impossible for a bird to have around 300 shot in its stomach.

References

- Arnemo J.M., Andersen O., Stokke S.et al. (2016) Health and Environmental Risks from Lead-based Ammunition: Science Versus Socio-Politics. EcoHealth 13, 618–622. [CrossRef]

- Allen C., Andersen O., Andreotti A., et al (2023) European scientists’ open letter on the risks of lead ammunition. http://www.europeanscientists.eu/open-letter-2023/.

- Andersen O, Andreotti A, Arnemo JM et al (2018) European scientists’ open letter on the risks of lead ammunition. http://www.europeanscientists.eu/open-letter-2018/.

- Andersen O, Arnemo JM, Bellinger DC et al (2020) European scientists’ open letter on the risks of lead ammunition. http://www.europeanscientists.eu/open-letter-2020/.

- Anderson WL, Havera SP, Zercher BW (2000) Ingestion of lead and nontoxic shotgun pellets by ducks in the Mississippi flyway. J Wildl Manage 64, 848–857. [CrossRef]

- Bannon, D. I., Drexler, J. W., Fent, G. M., Casteel, S. W., Hunter, P. J., Brattin, W. J., & Major, M. a. (2009). Evaluation of Small Arms Range Soils for Metal Contamination and Lead Bioavailability. Environmental Science & Technology, 43(24), 9071–9076. [CrossRef]

- Beyer, W. Nelson; Basta, Nicholas T.; Chaney, Rufus L.; Henry, Paula F.P.; Mosby, David E.; Rattner, Barnett A.; Scheckel, Kirk G.;Sprague, Daniel T.; and Weber, John S., "Bioaccessibility Tests Accurately Estimate Bioavailability Of Lead To Quail" (2016). USGS/ Staff -- Published Research. 968.http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/968 [accessed September 16, 2023].

- Bhavna V. Mohite. Iron Determination - A Review of Analytical Methods. Asian J. Research Chem. 4(3): March 2011; Page 348-361.

- Bosso, S. T., & Enzweiler, J. (2007). Bioaccessible lead in soils, slag, and mine wastes from an abandoned mining district in Brazil. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 30(3), 219–229. [CrossRef]

- Brewer, L.; Fairbrother, A.; Clark, J.; Amick, D. Acute toxicity of lead, steel, and an iron-tungsten-nickel shot to mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos). Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2003, 39, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, S., Noller, B., Matanitobua, V., & Ng, J. (2007). In Vitro Physiologically Based Extraction Test (PBET) and Bioaccessibility of Arsenic and Lead from Various Mine Waste Materials. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A, 70(19), 1700–1711. [CrossRef]

- Denbow D.M. Chapter 12: Gastrointestinal Anatomy and Physiology. In: Whittow GC, editor. Sturkies Avian Physiology. 5th ed. San Diego, California: Academic Press; 2000. p. 299–325.

- ECHA (2021) Annex XVRestriction Report – Lead in outdoor shooting and fishing. https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/da9bf395-e6c3-b48e-396f-afc8dcef0b21.

- Fayiga, A. O., Saha, U. K. (2016). Soil pollution at outdoor shooting ranges: Health effects, bioavailability and best management practices. Environmental Pollution, 216, 135–145. [CrossRef]

- Finley M.T., Dieter M.P., Locke L.N. (1976) δ-Aminolevulinic acid dehydratase: Inhibition in ducks dosed with lead shot, Environmental Research,Volume 12, Issue 2, рages 243-249. [CrossRef]

- Finley M.T., DieterM.P. Toxicity of experimental lead–iron shot versus commercial lead shot in mallards. Journal of Wildlife Management 42, 32–39. [CrossRef]

- Franson J.C., and Pain D.J. (2011). Lead in birds. In Environmental contaminants in biota: Interpreting tissue concentrations, ed. W.N. Beyer and J.P. Meador, 563–593. Boca Raton: Taylor and Francis Group.

- French, A. D., Shaw, K., Barnes, M., Cañas-Carrell, J. E., Conway, W. C., & Klein, D. M. (2020). Bioaccessibility of antimony and other trace elements from lead shot pellets in a simulated avian gizzard environment. PLOS ONE, 15(2), e0229037. [CrossRef]

- Furman, O., Strawn, D. G., Heinz, G. H., & Williams, B. (2006). Risk Assessment Test for Lead Bioaccessibility to Waterfowl in Mine-Impacted Soils. Journal of Environment Quality, 35(2), 450. [CrossRef]

- GOST 12536-2014. Soils. Methods of laboratory granulometric (grain-size) and microaggregate distribution.

- Green, R.E., Pain, D.J. (2019)Risks to human health from ammunition-derived lead in Europe. Ambio 48, 954–968. [CrossRef]

- Haig, S. M., D’Elia, J., Eagles-Smith, C., Fair, J. M., Gervais, J., Herring, G., Rivers J.M., Schulz, J. H. (2014). The persistent problem of lead poisoning in birds from ammunition and fishing tackle. The Condor, 116(3), 408–428. [CrossRef]

- ICD-10 Version:2019. The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en.

- ICD-10:E83.1 Disorders of iron metabolism. ICD-10 Version:2019 https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en#/E83.1.

- Krone O, Kenntner N, Ebner N, Szentiks CA, Dänicke S. Comparing erosion and organ accumulation rates of lead and alternative lead-free ammunition fed to captive domestic ducks. Ambio. 2019 Sep;48(9):1065-1071. [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw M.A.S., Filippelli G., Mielke H., Gulson B., BallА.S. (2017)Lead exposure at firing ranges—a review. Environ Health 16, 34. [CrossRef]

- Lewis N.L, Nichols T.C, Lilley C, Roscoe D.E, Lovy J. 2021. Blood lead declines in wintering American black ducksin New Jersey following the lead shot ban. Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management 12(1):174–182; e1944-687X. [CrossRef]

- Liljebäck, N., Sørensen, I.H., Sterup, J. et al. Prevalence of imbedded and ingested shot gun pellets in breeding sea ducks in the Baltic Sea—possible implications for future conservation efforts. Eur J Wildl Res 69, 73 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Lisin V., Chizhikova V., Lubkova T., Yablonskaya D. (2020) Management of Environmental Risks Related to the Use of Lead Ammunition at Outdoor Sports Facilities (Shooting Ranges) Guidelines on the Best Available Practices.

- Lisin V., Chizhikova V., Lubkova T., Yablonskaya D. Steel Shot as a Risk Factor for Soils at the Area of Shooting Activity. Preprints 2022, 202205.0309. [CrossRef]

- Lisin, V.,Chizhikova, V., Lubkova, T.,Yablonskaya, D. Experimental Study of Steel Shot and Lead Shot Transformation Under the Environmental Factors. Preprints 2022, 2022010077. [CrossRef]

- Marschner, B., Welge, P., Hack, A., Wittsiepe, J., & Wilhelm, M. (2006). Comparison of Soil Pb in Vitro Bioaccessibility and in Vivo Bioavailability with Pb Pools from a Sequential Soil Extraction. Environmental Science & Technology, 40(8), 2812–2818. [CrossRef]

- Mateo R., Kanstrup N. (2019) Regulations on lead ammunition adopted in Europe and evidence of compliance. Ambio 48(9): 989-998. [CrossRef]

- Oomen, A. G., Hack, A., Minekus, M., Zeijdner, E., Cornelis, C., Schoeters, G., … Van Wijnen, J. H. (2002). Comparison of Five In Vitro Digestion Models To Study the Bioaccessibility of Soil Contaminants. Environmental Science & Technology, 36(15), 3326–3334. [CrossRef]

- Oomen, A. G., Tolls, J., Sips, A. J. A. M., &Groten, J. P. (2003). In Vitro Intestinal Lead Uptake and Transport in Relation to Speciation. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 44(1), 116–124. [CrossRef]

- Pain DJ, Cromie R, Green RE (2015) Poisoning of birds and other wildlife from ammunition-derived lead in the UK. In: Proceedings of the Oxford Lead Symposium: Lead Ammunition: Understanding and Minimizing the Risks to Human and Environmental Health, Delahay RJ, Spray CJ (editors), Oxford University: Edward Grey Institute, pp 58-84.

- Pain, D.J., Mateo, R. & Green, R.E. Effects of lead from ammunition on birds and other wildlife: A review and update. Ambio 48, 935–953 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Pain, D.J., Green, R.E., Taggart, M.A. et al. How contaminated with ammunition-derived lead is meat from European small game animals? Assessing and reducing risks to human health. Ambio 51, 1772–1785 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Pelfrêne, A., Waterlot, C., Mazzuca, M., Nisse, C., Bidar, G., & Douay, F. (2010). Assessing Cd, Pb, Zn human bioaccessibility in smelter-contaminated agricultural topsoils (northern France). Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 33(5), 477–493. [CrossRef]

- Plouzeau E, Guillard O, Pineau A, Billiald P, Berny P. Will leaded young mallards take wing? Effects of a single lead shot ingestion on growth of juvenile game-farm Mallard ducks Anas platyrhynchos. Sci Total Environ. 2011 May 15;409(12):2379-83. [CrossRef]

- Portman, O. W., Mcconnell, K. P., & Rigdon, R. H. (1952). Blood Volumes of Ducks Using Human Serum Albumin Labeled with Radioiodine. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 81(3), 599–601. [CrossRef]

- Rocke T. E., & Samuel M. D. (1991). Effects of lead shot ingestion on selected cells of the mallard immune system. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 27(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Ruby, M.V.; Davis, A.; Link, T.E.; Schoof, R.; Chaney, R.L.; Freeman, G.B.; Bergstrom, P. Ruby, M.V.; Davis, A.; Link, T.E.; Schoof, R.; Chaney, R.L.; Freeman, G.B.; Bergstrom, P. Development of an in vitro screening test to evaluate the in vivo bioaccessibility of ingested mine-waste lead. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1993, 27, 2870–2877.

- Ruby, M. V., Davis, A., Schoof, R., Eberle, S., &Sellstone, C. M. (1996). Estimation of Lead and Arsenic Bioavailability Using a Physiologically Based Extraction Test. Environmental Science & Technology, 30(2), 422–430. [CrossRef]

- Treu, G., Drost, W. & Stock, F. An evaluation of the proposal to regulate lead in hunting ammunition through the European Union’s REACH regulation. Environ Sci Eur 32, 68 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.G., Kanstrup, N. & Fox, A.D. The transition to non-lead sporting ammunition and fishing weights: Review of progress and barriers to implementation. Ambio 48, 925–934 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Walraven, N., Bakker, M., van Os, B. J. H., Klaver, G. T., Middelburg, J. J., & Davies, G. R. (2015). Factors controlling the oral bioaccessibility of anthropogenic Pb in polluted soils. Science of The Total Environment, 506-507, 149–163. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2022) Guideline for the clinical management of exposure to lead.World Health Organization. Geneva. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Wragg J. and Cave M.R. (2003) In-vitro Methods for the Measurement of the Oral Bioaccessibility of Selected Metals and Metalloids in Soils: A Critical Review https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7c379340f0b674ed20f9c5/sp5-062-tr-1-e-e.pdf [accessed August 10, 2023].

- Zia, M. H., Codling, E. E., Scheckel, K. G., & Chaney, R. L. (2011). In vitro and in vivo approaches for the measurement of oral bioavailability of lead (Pb) in contaminated soils: A review. Environmental Pollution, 159(10), 2320–2327. [CrossRef]

- Zingaretti, D.; Baciocchi, R. Different Approaches for Incorporating Bioaccessibility of Inorganics in Human Health Risk Assessment of Contaminated Soils. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3005. [CrossRef]

| 1 | The relevant documents are available at echa.europa.eu (https://echa.europa.eu/hot-topics/lead-in-shot-bullets-and-fishing-weights) |

| 2 |

https://echa.europa.eu/hot-topics/lead-in-shot-bullets-and-fishing-weights, accessed on September 4, 2023 |

| 3 | EFSA. Scientific opinion on lead in food. http://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/scientific_output/files/main_documents/1570.pdf [accessed September 27, 2023] |

| 4 | the percentage of metal that enters the gastrointestinal tract when the substrate dissolved in gastrointestinal solutions. |

| 5 | the percentage of metal that enters the blood circulatory system from the gastrointestinal tract. |

| 6 | indicated for the bioaccessibility levels of elements obtained by the authors of this paper. |

| 7 |

https://echa.europa.eu/environmental-quality-standards/-/legislationlist/details/EU-EQS_WATER-ANX_I-100.239.187-VSK-G076O8; https://echa.europa.eu/environmental-quality-standards/-/legislationlist/details/EU-EQS_WATER-ANX_I-100.239.187-VSK-G076O8 [accessed December 11, 2023] |

| 8 | |

| 9 | WHO. Lead Poisoning and Health. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs379/en/ [accessed September 15, 2023] |

| 10 | EFSA. Scientific opinion on lead in food. [accessed September 27, 2023] |

| 11 | anaemia, weight loss, muscular incoordination, green diarrhoea, anorexia, microscopic lesions in tissues. |

| Soil | Total metal, mg/kg | pH | EC | The main phases, % (identified by the XRD) | Soil texture (%) | Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Fe | >250 μm | <250 μm | |||||

| 1 | 4500 | 15000 | 7.9 | 140 | Quartz (64), albite (13), microcline (10), carbonate (7), clay minerals (6) |

65 | 35 | Sandy loam |

| 2 | 3300 | 26300 | 7.8 | 190 | 64 | 36 | Sandy loam | |

| 3 | 3200 | 25000 | 7.6 | 200 | Quartz (69), albite (10), microcline (10), clay minerals (8) carbonate (3) | 56 | 44 | Sandy loam |

| Shot | GI tract | Time, min | Pb, mg/l | Pb, mg/g | Fe, mg/l | Fe, mg/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mean ± SE) | (mean ± SE) | |||||

| The gastrointestinal tract of waterfowl | ||||||

| Lead | Stomach, рН 2.5 | 60 | 5.84 ± 0.14 | 0.50 | ||

| Intestine, рН 6.2 | 240 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.01 | |||

| Steel | Stomach, рН 2.5 | 60 | 8.27 ± 0.85 | 0.70 | ||

| Intestine, рН 6.2 | 240 | 3.10 ± 0.47 | 0.26 | |||

| Lead:steel 1:1 |

Stomach, рН 2.5 | 60 | 2.25 ± 0.33 | 0.38 | 4.52 ± 0.49 | 0.74 |

| Intestine, рН 6.2 | 240 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | 2.58 ± 0.38 | 0.42 | |

| The gastrointestinal tract of mammals and humans | ||||||

| Lead | Stomach рН 1.5 |

30 | 4.00 ± 0.57 | 0.40 | ||

| 60 | 6.53 ± 1.00 | 0.65 | ||||

| 90 | 6.80 ± 0.42 | 0.68 | ||||

| 120 | 7.80 ± 0.42 | 0.78 | ||||

| Intestine, рН 7 | 120 | 3.89 ± 0.57 | 0.39 | |||

| Steel | Stomach рН 1.5 |

30 | 3.10 ± 0.42 | 0.31 | ||

| 60 | 7.13 ± 0.81 | 0.71 | ||||

| 90 | 7.05 ± 0.21 | 0.71 | ||||

| 120 | 7.95 ± 0.21 | 0.80 | ||||

| Intestine, рН 7 | 120 | 8.05 ± 0.07 | 0.81 | |||

| Lead:steel 1:1 |

Stomach, рН 1.5 |

30 | 2.51 ± 0.04 | 0.25 | 1.31 ± 0.20 | 0.13 |

| 60 | 3.06 ± 0.11 | 0.31 | 2.50 ± 0.05 | 0.25 | ||

| 90 | 3.11 ± 0.21 | 0.31 | 4.79 ± 0.10 | 0.48 | ||

| 120 | 3.07 ± 0.10 | 0.31 | 7.30 ± 0.31 | 0.73 | ||

| Intestine, рН 7 | 120 | 2.04 ± 0.19 | 0.20 | 7.47 ± 0.47 | 0.75 | |

| Lead:steel 2:1 |

Stomach рН 1.5 |

30 | 1.91 ± 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.49 ± 0.04 | 0.13 |

| 60 | 2.71 ± 0.17 | 0.41 | 1.30 ± 0.03 | 0.35 | ||

| 90 | 3.14 ± 0.28 | 0.47 | 2.11 ± 0.31 | 0.56 | ||

| 120 | 3.28 ± 0.05 | 0.48 | 2.81 ± 0.07 | 0.75 | ||

| Intestine, рН 7 | 120 | 1.73 ± 0.15 | 0.25 | 3.01 ± 0.09 | 0.80 | |

| Lead:steel 1:2 |

Stomach рН 1.5 |

30 | 0.68 ± 0.06 | 0.21 | 1.50 ± 0.08 | 0.19 |

| 60 | 0.82 ± 0.10 | 0.25 | 2.08 ± 0.06 | 0.27 | ||

| 90 | 0.82 ± 0.02 | 0.25 | 3.62 ± 0.23 | 0.46 | ||

| 120 | 0.80 ± 0.10 | 0.25 | 5.67 ± 0.12 | 0.74 | ||

| Intestine, рН 7 | 120 | 0.60 ± 0.06 | 0.18 | 6.31 ± 0.02 | 0.81 | |

| Lead:steel 1:6 |

Stomach рН 1.5 |

30 | 0.31 ± 0.05 | 0.20 | 2.56± 0.06 | 0.26 |

| 60 | 0.42 ± 0.06 | 0.25 | 3.50 ± 0.13 | 0.39 | ||

| 90 | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 0.24 | 5.27 ± 0.30 | 0.59 | ||

| 120 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 0.26 | 6.34 ± 0.36 | 0.70 | ||

| Intestine, рН 7 | 120 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.20 | 7.34± 0.49 | 0.76 | |

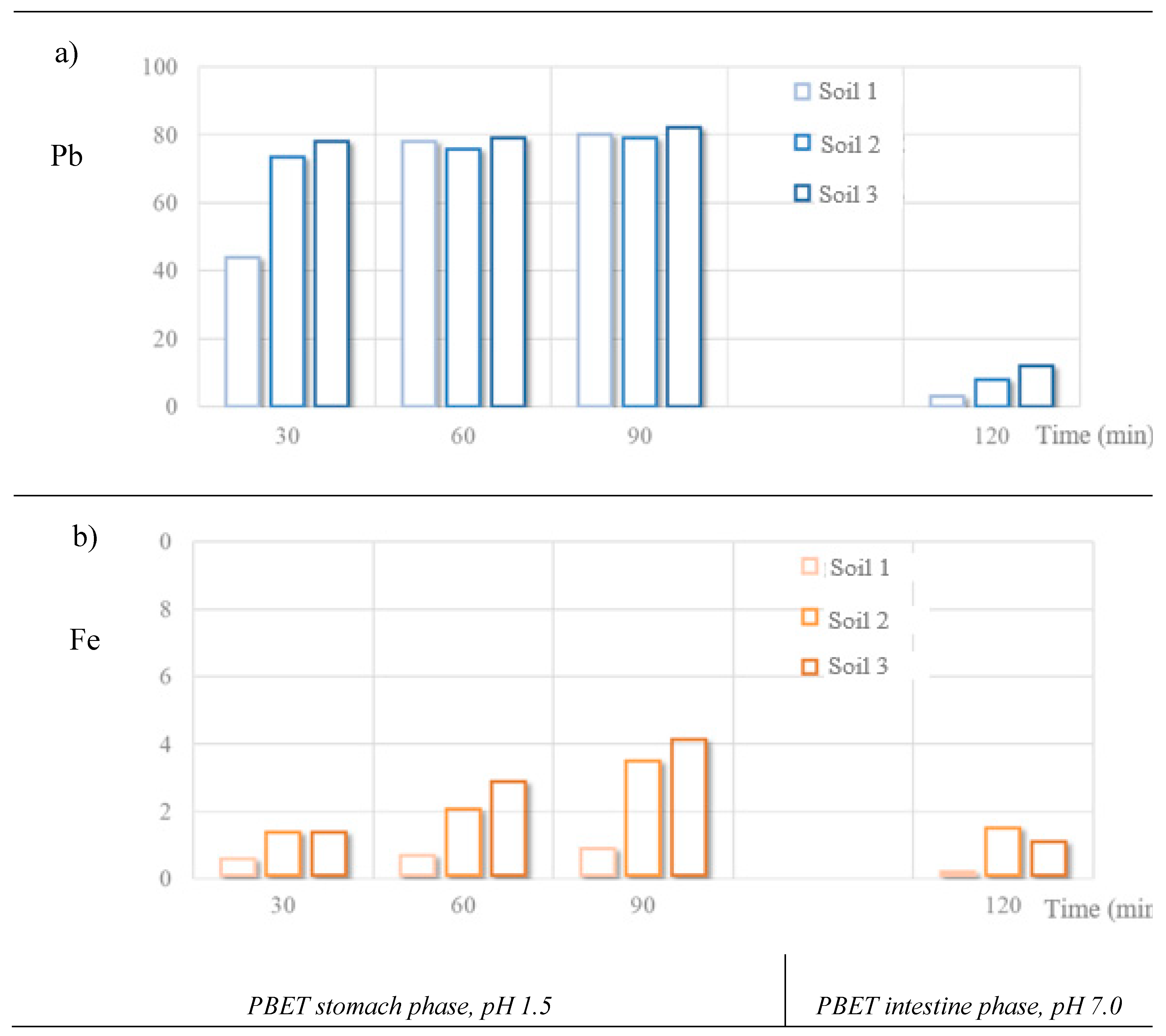

| Soil | GI tract | Time, min | Pb, mg/l | Pb, mg/g | Fe, mg/l | Fe, mg/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mean ± SE) | (mean ± SE) | |||||

| 1 | Stomach, рН 1.5 | 30 | 20.4 ± 3 | 2.0 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 0.1 |

| 60 | 35.0 ± 3 | 3.5 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.1 | ||

| 90 | 36.0 ± 5 | 3.6 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 0.2 | ||

| Intestine, рН 7 | 120 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 0.14 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.03 | |

| 2 | Stomach, рН 1.5 | 30 | 25.2 ± 1.4 | 2.5 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 60 | 26.1 ± 1.2 | 2.6 | 5.4 ± 1.7 | 0.5 | ||

| 90 | 27.1 ± 1.2 | 2.7 | 9.2 ± 4.8 | 0.9 | ||

| Intestine, рН 7 | 120 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 0.3 | 2.9 ± 1.3 | 0.3 | |

| 3 | Stomach, рН 1.5 | 30 | 25.1 ± 2.1 | 2.5 | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 0.3 |

| 60 | 25.3 ± 0.7 | 2.5 | 7.2 ± 2.4 | 0.7 | ||

| 90 | 26.3 ± 1.9 | 2.6 | 10.3 ± 4.9 | 1.0 | ||

| Intestine, рН 7 | 120 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 0.3 | 2.9 ± 1.5 | 0.4 |

| Site | Pb threshold level in the GI tract, mg | GI tract organ | Pb bioaccessibility | Pb mass threshold (mg) in the substance entering the GI tract | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| shot, % of metal mass | soil, % of total | shot* | soil | |||

| Human | 2.5 | stomach | 0.08 | 82 | 2,500 | 3.0 |

| intestine | 0.04 | 3/12** | 6300 | 83/21 | ||

| Waterfowl | 0.25 | stomach | 0.05 | - | 500 | - |

| intestine | 0.001 | - | 25,000 | - | ||

| Blood lead concentration at the end of the experiment, mg/l | Calculated amount of shot based on the model, pcs | Note | |

| Control group | Test group | ||

| 0.69–0.71 | 1.64–3.08 | 59–110* (21–40)** |

12 ducks were intubated with one #4 lead shot (0.193 g) by gavage; at the end of one week, no signs of poisoning were observed (Finley et al., 1976). |

| 0.5–0.78 | 18–28* (6–10)** |

12 ducks were intubated with one #4 lead shot (0.193 g) by gavage; at the end of four weeks, no signs of poisoning were observed, the ducks had put on weight (Finley et al., 1976). | |

| 0.05–0.17 | 0.15–8.01 | 5–286* | 55 mallards placed in a 4-acre enclosure on a hunting wetland (with a lead shot density of 931±67 pellets per acre in the top 10 cm of sediment); at the end of 80 days, no clinical signs of lead poisoning were observed (Rocke&Samuel, 1991) |

| 0.65–8.71 | 23–311 *(8–109)** |

16 mallards were intubated with two #4 lead shot (0.2 g each) by gavage; by the end of 80 days, three of the birds had died while the others exhibited clinical signs of lead poisoning (Rocke&Samuel, 1991) | |

| 0.11–0.29 | 1.05 | 37 *(8)** |

14 ducks were intubated with one #2 lead shot (0.325 g) by gavage; at the end of 30 days, no signs of poisoning were observed (Plouzeau et al., 2011) |

| 0.67 | 24 *(9)** |

14 ducks were intubated with one #4 lead shot (0.177 g) by gavage; at the end of 30 days, no signs of poisoning were observed (Plouzeau et al., 2011) | |

| 0.90 | 33 *(19)** |

13 ducks were intubated with one #6 lead shot (0.125 g) by gavage; at the end of 30 days, no signs of poisoning were observed (Plouzeau et al., 2011) | |

| - | 0.03 | 1* | 277 ducks, minimum blood lead concentration in the natural habitat in shooting areas (New Jersey), no signs of poisoning were observed (Lewis et al., 2021) |

| 0.98 | 35* | 277 ducks, maximum blood lead concentration in the natural habitat in shooting areas (New Jersey), no signs of poisoning were observed (Lewis et al., 2021) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).