1. Introduction

The world’s population is aging and the prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases such as cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is increasing. There is growing evidence that age-related cognitive decline, an early marker for AD, is not inevitable. The identification of new interventions or new treatment targets becomes very important and efforts to reduce the prevalence of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease at the population level [

1].

As the main area of pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease lies in synaptic dysfunction rather than amyloidosis, a clinical focus on early physiopathological dementia events associated with synaptic damage is essential to avoid a belief in the sole therapeutic application of amyloidosis and anti-tau therapies [

2]. Interventions and studies exploring these levels have considered cognitive training and brain stimulation targeting brain plasticity and networks in subjects with MCI, as these interventions may be effective in preventing the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by the gradual accumulation of misfolded proteins, including amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, in the brain [

3,

4]. These pathological changes not only lead to cognitive impairment but also disrupt the intricate neuronal networks and synaptic plasticity that underlie various cognitive functions [

5]. The effects of Alzheimer’s disease go beyond the well-documented cognitive deficits and primarily affect memory processes. Memory deficits in particular are a central and debilitating feature of Alzheimer’s disease [

6,

7]. This cognitive decline is not only due to the well-known atrophy of the hippocampus but also to the widespread damage in large neuronal networks involved in memory functions [

8,

9]. One of the central neurophysiological mechanisms that are crucial for memory formation is

spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP). STDP is based on the precise timing of action potentials in pre- and postsynaptic neurons and represents a fundamental link between the precise synchronization of neuronal activity and the encoding of memories [

5,

10]. Neuroplasticity is associated with the progression of age-related cognitive decline and dementia, particularly AD, and can be targeted to (at least temporarily) counteract these age-related decline processes. However, the potential of combination therapies to enhance the positive neurophysiological and functional effects of neuron-modulating techniques in Alzheimer’s patients has not yet been sufficiently researched.

In our hypothesis, we investigate the consequences of disturbed STDP mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease. Using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), the study investigates the integrity of cortico-cortical spike-timing-dependent plasticity in Alzheimer’s patients [

11,

12,

13]. TMS is a non-invasive technique that allows researchers to selectively manipulate the activity of cortical regions [

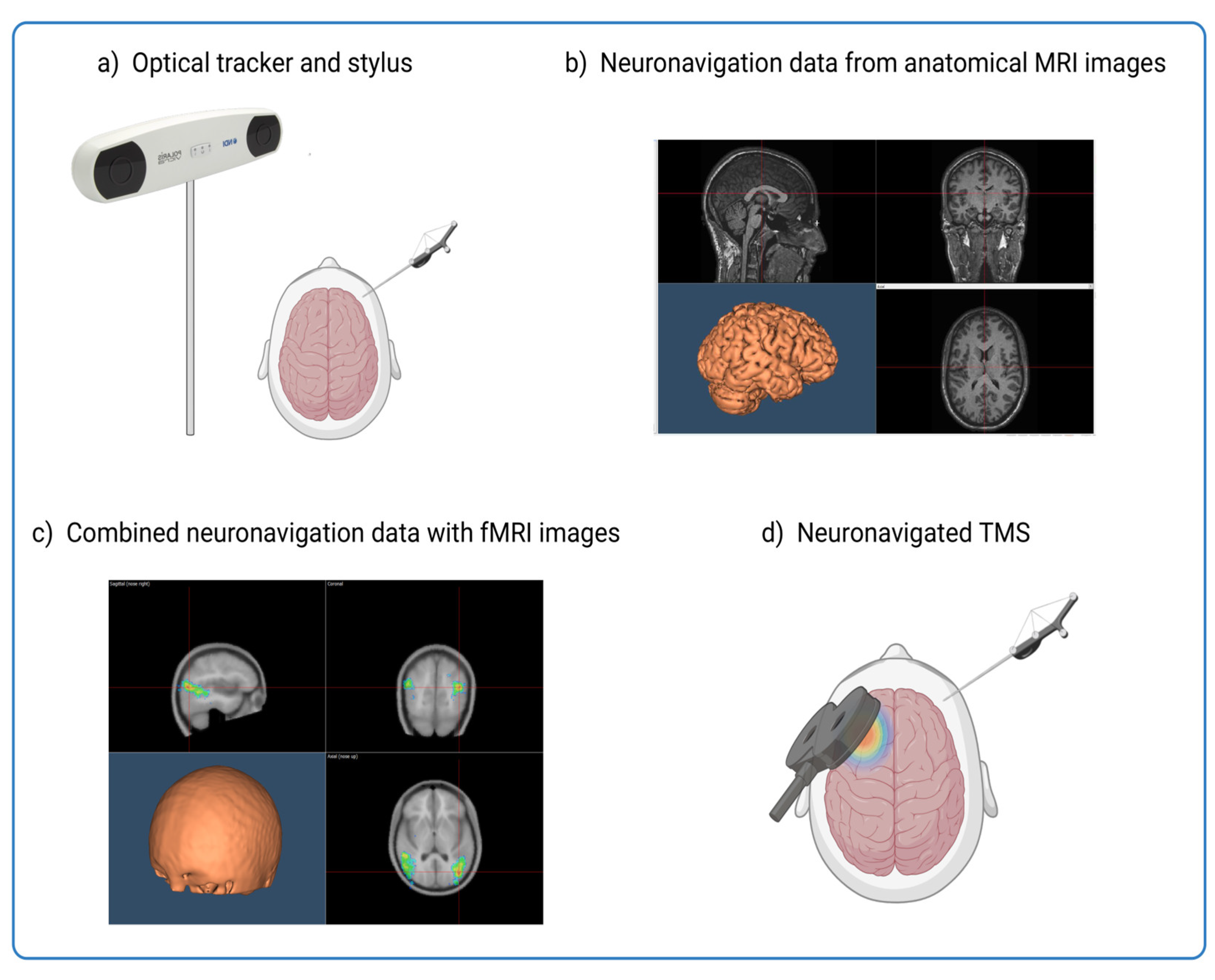

14]. By applying magnetic pulses to specific brain regions, we can assess causal relationships between brain regions with millisecond precision. In combination with neuronavigation, TMS can be precisely targeted to specific brain regions identified from imaging data such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [

14,

15]. Integrating resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) data into the neuronavigation process allows researchers to precisely identify and target the brain regions responsible for cognitive decline (see

Figure 1). This process is like a GPS, where the brain is the destination, and the fMRI data provides the map of the route.

As a mask for neuronavigation, imaging data improves not only the precision of stimulation in the study of perception and cognition, but also holds great promise in studying the effects of neurodegeneration on these critical brain regions. Furthermore, the integration of imaging data into the neuronavigation process allows researchers to study the changes in functional connectivity in the neural networks affected by neurodegenerative diseases. In addition to improving understanding of how neurodegeneration disrupts brain function, this approach also offers insights into potential therapeutic targets to mitigate its effects.

Recently, an innovative technique called “cortico-cortical associative stimulation” (ccPAS) has been used to generate patterns that can induce synaptic plasticity similar to Hebbian plasticity [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. In this cutting-edge stimulation protocol, specific brain regions are stimulated simultaneously to strengthen the connections between them. This in turn has the potential to improve cognitive and perceptual functions. Furthermore, when applied to specific motor and vestibular areas, ccPAS can also modulate the motor and somatosensory symptoms associated with Alzheimer’s disease. By incorporating individual fMRI data, neuronavigation systems can tailor ccPAS to specific cortical regions that are functionally relevant and optimal for inducing plasticity, maximizing the therapeutic potential in treating the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.

The resulting findings highlight the central role of synaptic remodeling in the pathophysiological processes of Alzheimer’s disease and shed light on the specific impairments that affect neuronal plasticity in this population. Beyond the study of Alzheimer’s disease, the hypothesis also aims to uncover broader implications by venturing into the field of rehabilitation for the elderly. Aging itself presents several challenges as progressive neuronal dysfunction reduces neuronal plasticity and contributes to functional decline [

22,

23]. Manual dexterity and speed are particularly affected, with changes in factors such as white matter volume and density and changes in brain connectivity influencing this decline.

2. A narrative Review Approach

Building on the findings from the studies on aging and Alzheimer’s disease, we propose that the application of ccPAS stimulation may improve cortical plasticity in the elderly, ultimately leading to an improvement in motor performance. As ccPAS counteracts the age-related decline in neuronal plasticity and neurodegeneration, it emerges as a promising avenue for rehabilitation and offers the potential to alleviate the motor deficits associated with aging.

This hypothesis bridges the gap between research on physiological brain aging and neurodegenerative processes. It suggests that ccPAS could be the key to improving cortical plasticity and thus motor performance in older people.

The public biomedical and scientific literature database Pubmed (

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) was used to find studies on the potential of ccPAS in age-related declines in neuronal plasticity and its impact on rehabilitation in the context of aging and Alzheimer’s disease. A systematic search strategy was used to identify relevant articles published between 2013 [

24] and 2023. To better narrow the topic, an introductory Boolean search term was created:

[(ccPAS OR “cortico-cortical associative stimulation”) AND (“aging” OR “Alzheimer’s disease” OR AD)]. Accordingly, only 5 articles with the selected search term were indexed in PubMed by 20 December 2023: 4 original research articles [

25,

26,

27,

28] and 1 systematic review [

29]. As Momi et al [

28] did not study the clinical population of interest, it was excluded from the analysis.

Due to the limited number of articles identified, we were forced to perform a narrative review. The scarcity of available literature necessitated this approach to comprehensively investigate the potential of ccPAS in managing age-related declines in neuronal plasticity and its impact on rehabilitation in the context of aging and Alzheimer’s disease. For each selected original study [

25,

26,

27], key information on the investigated ccPAS was extracted (see

Table 1).

3. Main Findings

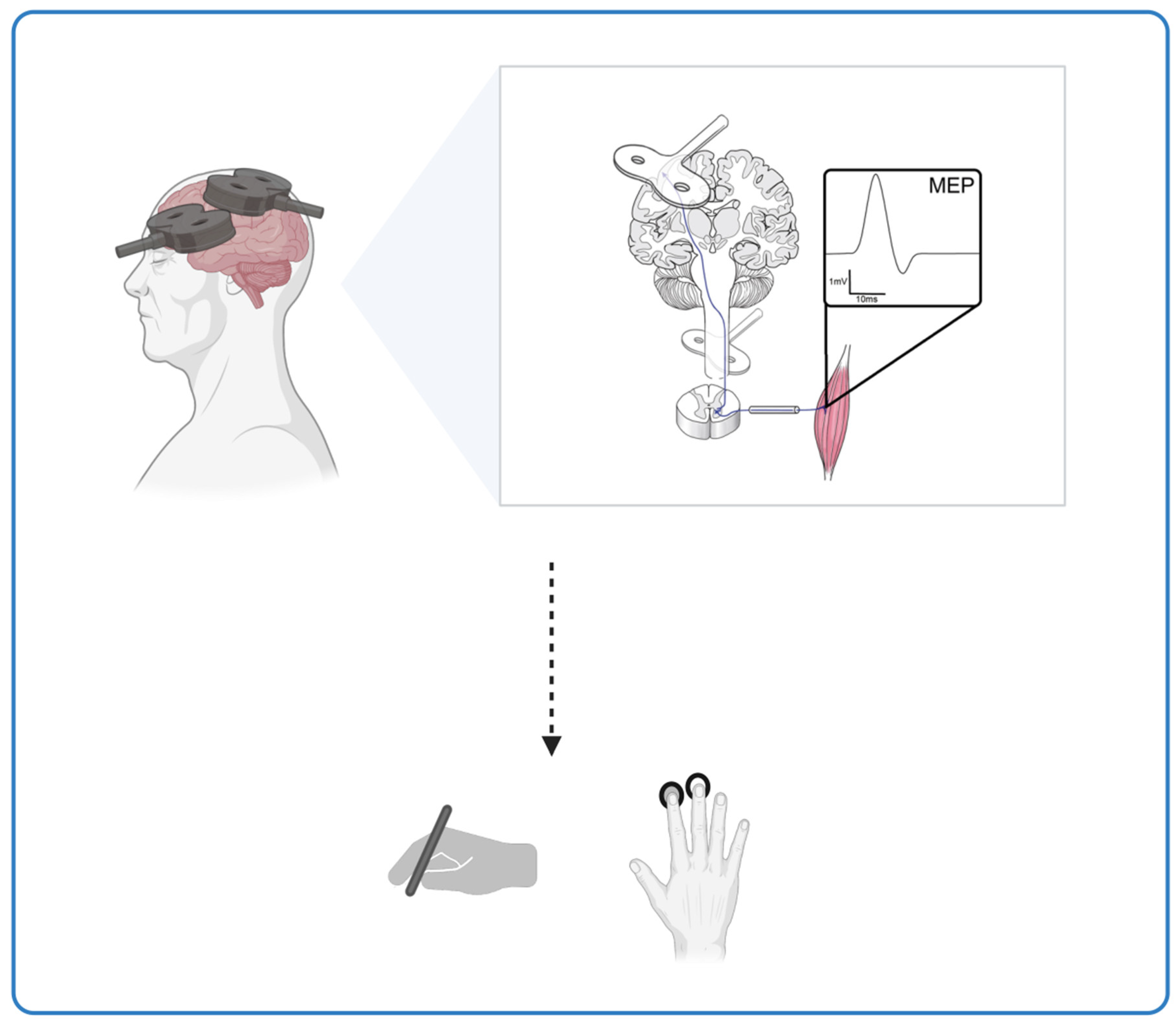

The results of these studies provide a comprehensive overview of cortical plasticity in healthy populations and clinical situations. The first study investigated in detail how cortical STDP is altered in Alzheimer’s patients; the second study assessed the age-specific effects of ccPAS on hand dexterity, while the third study investigated age-related differences in neuroplasticity and motor performance between young and elderly people.

The study by Di Lorenzo et al. [

25] investigated the mechanisms of cortico-cortical STDP in AD patients compared to healthy subjects. The AD patients underwent a full clinical examination, including medical history, neurological examination, Mini-Mental State Examination, blood testing, neuropsychological assessment, neuroimaging, and CSF analysis. TMS at two sites was used to repeatedly activate the connections between the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) and the primary motor cortex (M1) in the left dominant hemisphere. A ccPAS protocol was applied to investigate the aftereffects of STDP within the PPC-M1 connection. The authors found that the mechanisms of cortico-cortical STDP were altered in AD patients, with a marked impairment of long-term potentiation (LTP) and a relative sparing of long-term depression (LTD), which is similar to plasticity. The study also emphasizes the role of cortical network dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease and suggests impairment of the large networks underlying memory processes. The results suggest that the integrity of synaptic transmission is essential for functional communication in the brain and that its impairment can lead to cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. The results of the study are consistent with previous research and animal models of Alzheimer’s pathology. They suggest that the impairment of cortical plasticity mechanisms is an early event in the cascade of physiopathological processes that lead to neurodegeneration and dementia.

The study by Turrini et al. [

26] investigated the age-specific effects of ccPAS on hand dexterity in young and older participants. The study aimed to determine whether older adults had lower manual dexterity, plastic potential, and responsiveness to ccPAS compared to young adults at baseline. The authors emphasized the importance of age-related changes in neuronal function and how these can lead to reduced plasticity, which may contribute to loss of function in older adults. The study used a sample of 28 healthy volunteers who were divided into two groups of 14 based on their chronological age to investigate the importance of PMv-M1 connectivity (ventral motor cortex to primary motor cortex) for manual dexterity. Participants performed the 9-Hole Peg Test (9HPT) and a choice reaction task (cRT) at four time points: two before ccPAS, one immediately after, and one 30 minutes after ccPAS. The study found that ccPAS improved 9HPT performance in young participants, but not in older participants, especially 30 minutes after the ccPAS protocol. The ccPAS manipulation did not affect cRT performance in either group. In addition, the study tested neurophysiological indices of Hebbian plasticity and found that only modulation of MEPs (motor-evoked potentials) predicted the magnitude of the speed increase in 9HPT at 0 and 30 minutes. The results suggest that ccPAS may have age-specific effects on hand dexterity and that the modulation of MEPs may be a predictor of the behavioral changes induced by ccPAS. These results raise the interesting question of how the available non-invasive brain stimulation devices can be adapted and personalized for the aging population. This suggests that the implementation of protocols adapted to the physiological changes in the motor system of older adults would be advisable.

Following their earlier work on the effects of ccPAS on corticomotor excitability, Turrini and colleagues [

27] wanted to determine how age-related differences in neuroplasticity correlate with differences in motor performance observed between young and older individuals. The ccPAS parameters were chosen to repeatedly activate and enhance a cortico–cortical excitatory pathway from the PMv to the M1. This protocol has been shown to produce a gradual increase in MEPs during ccPAS administration in the majority of healthy young participants. A total of 28 individuals participated, including 14 young adults and 14 older adults. Participants were assessed on two different motor tasks: the 9HPT, a measure of manual dexterity, and a cRT, which assessed the speed of visuomotor transformation. The ccPAS was administered to all participants, stimulating the left PMv-to-M1 circuit. The results of the study showed a significant dichotomy in baseline performance between age groups on both motor tasks. Younger participants showed better motor performance, as evidenced by faster execution times in the 9HPT and faster reaction times in the cRT task. In addition, corticospinal excitability, as measured by the resting motor threshold (rMT), was significantly higher in older individuals compared to their younger counterparts. Further investigation of the modulation of corticomotor excitability during ccPAS revealed different patterns in young and older adults. MEPs recorded during ccPAS stimulation showed a progressive increase in young participants, while inconsistent MEP modulation was observed in older participants. Importantly, the linear slope of ccPAS-induced MEP modulation was found to be a predictive measure of individual differences in motor performance (9HPT performance speed and cRTs). This study suggests that the ability of PMv-M1 ccPAS to increase corticomotor excitability is a valuable predictor of hand-motor dexterity and speed. This neurophysiological marker reflects the preserved plastic properties of the PMv-M1 circuit and provides insight into the maintenance of motor function at different ages.

4. Discussion

Neuroplasticity refers to neural mechanisms that allow the brain to change and adapt in response to experience, but aging can result in reduced plasticity and functional decline [

26]. Hence, behavioral interventions for improving brain function are increasingly in demand, particularly to sustain a healthy lifestyle in old age where cognition becomes limited. These interventions are expected to increase mental health and will subsequently contribute positively to the quality of life [

2]. In light of the aging demographics, the number of people suffering from neurodegenerative conditions such as AD is rapidly increasing. Whether caused by the process of brain aging or resulting from the pathological changes of AD, disturbing functionalities of neuronal networks contribute to the cognitive deficits of these patients.

Our article discusses the consequences of disrupted STDP in Alzheimer’s disease and investigates the potential of ccPAS stimulation to improve cortical plasticity in the elderly. Alzheimer’s disease is a common neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the gradual accumulation of misfolded proteins, leading to cognitive impairment and disruptions in neural networks and synaptic plasticity. The effects of Alzheimer’s disease also extend to memory processes, with deficits in memory being a central feature of the disease. STDP, a crucial neurophysiological mechanism for memory formation, relies on the precise timing of action potentials in pre- and postsynaptic neurons.

TMS has previously demonstrated its potential to modulate cortical excitability and to influence and entrain rhythmical brain activity [

30]. Thus, using TMS for a multi-site, network-based modulation of cortical excitability might be a relevant and advanced approach. The hypothesis is that the application of ccPAS stimulation can enhance cortical plasticity in the elderly, ultimately leading to improved motor performance by counteracting the age-related deterioration of neural plasticity. This hypothesis bridges the gap between research on neurodegenerative diseases and the challenges of aging and suggests that ccPAS may be the key to improving cortical plasticity and motor performance in the elderly. Despite the limited pool of literature, our narrative review serves to synthesize existing knowledge and shed light on the potential role of ccPAS in addressing age-related declines in neural plasticity, thereby informing future research directions and clinical applications in the field of aging and neurodegenerative disorders.

Three studies are presented to support the hypothesis. In the first study by Di Lorenzo et al [

25], the mechanisms of cortical STDP were found to be altered in AD patients, with marked impairment of LTP-like plasticity and a relative sparing of LTD-like plasticity. The second study by Turrini et al [

26] investigated the age-specific effects of ccPAS on hand dexterity in young and elderly participants and found that ccPAS improved hand dexterity in young participants but not in elderly participants, suggesting age-specific effects on hand dexterity. The third study by Turrini and colleagues [

27] aimed to extend the understanding of how age-related differences in neuroplasticity correlate with differences in motor performance between young and elderly people.

This raises key questions: what is the relationship between disrupted STDP and the targeted effects of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) techniques, particularly ccPAS, in AD? Could the changes observed in the cortico-cortical STDP pathways serve as potential markers for the efficacy of ccPAS interventions? Investigating the potential of NIBS interventions and their effects could explore the molecular and cellular interactions that could further unravel this relationship. How might age-related variations in response to ccPAS extend to other cognitive domains affected by aging or Alzheimer’s disease? Could this technique be tailored to specific cognitive deficits that might change with age beyond motor performance?

Considering the long-term prognosis, the idea of therapeutic applications in which advances in ccPAS revolutionize rehabilitation strategies not only for Alzheimer’s disease but also for other age-related neurological disorders is of paramount importance [

31,

32]. A multidisciplinary approach is central to the utilization of NIBS techniques. The integration of knowledge from neurology, neuroscience, engineering, and ethics could generate innovative strategies and refine the application of NIBS in neurological rehabilitation.

The results of these studies support the hypothesis that the application of ccPAS stimulation can enhance cortical plasticity in the elderly, ultimately leading to improved motor performance [

33]. The studies provide valuable insights into the potential of ccPAS in addressing age-related declines in neuronal plasticity and its impact on rehabilitation in the context of aging and Alzheimer’s disease. However, these studies also have limitations that should be considered. For example, the age-specific effects of ccPAS on hand dexterity raise questions about the generalisability of the results to other motor functions and age groups. In addition, the small sample sizes and the specific methods of the studies may limit the generalisability of the results. Future research should therefore aim to replicate and extend these findings with larger, more diverse samples and a range of motor tasks. Furthermore, the limitations related to the complexity of applying ccPAS to more complex domains and its effects on complicated cognitive functions are crucial considerations for the future of neurorehabilitation. They emphasize the need to continue research and proactively address the opportunities offered by different NIBS to improve the lives of older people with cognitive challenges. This path requires interdisciplinary collaboration and rigorous scientific investigation to effectively utilize and refine NIBS techniques.

Ultimately, the studies presented provide crucial insights into neuronal plasticity in aging and Alzheimer’s disease and serve as a starting point for deeper exploration of NIBS techniques. This journey involves not only further research but also a proactive exploration of the opportunities that various NIBS interventions offer to improve the lives of older people with cognitive problems. The future of neurorehabilitation depends on our ability to utilize and refine NIBS techniques through interdisciplinary collaboration and rigorous scientific investigation.

We hypothesize that ccPAS not only increases the efficacy of neuromodulation to complement the treatment of neurocognitive disorders but also utilizes the modern techniques of neuronavigation. Neuronavigation enables precise identification of target brain areas, minimizes scattering, and maximizes the effectiveness of stimulation. This precision is particularly important in the context of aging, where anatomical changes can obscure relevant cortical areas. In addition, neuronavigation enables personalized treatment tailored to the anatomical and functional characteristics of the brain. Furthermore, the integration of individualized rs-fMRI data allows clinicians to monitor long-term changes in brain activity and connectivity patterns during ccPAS treatment. This capability enables adaptive adjustments to the stimulation protocol, ensuring continuous optimization of therapy parameters and leading to sustainable improvements in neurological function. Such personalized adjustments enhance the overall efficacy of ccPAS in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

However, despite the potential of neuronavigation in guiding ccPAS interventions, there are notable challenges and limitations associated with its use. One of these limitations concerns the acquisition of imaging data required for accurate neuronavigation. Acquiring high-quality imaging data, such as structural MRI or functional MRI (fMRI), can be a resource-intensive and time-consuming process. In addition, access to advanced imaging facilities may be limited in certain healthcare settings, adding to the challenge of obtaining reliable imaging data for neuronavigation. And even when imaging data is available, it can be inherently variable and have limited reliability. Factors such as motion artifacts during scanning, anatomical variations in different individuals, and technical limitations in image processing algorithms can lead to inaccuracies in the registration and alignment of image data for neuronavigation. These limitations can compromise the precision and effectiveness of ccPAS targeting and undermine therapeutic outcomes.

Despite these challenges, our approach combining ccPAS with neuronavigation is proving to be groundbreaking in the field of neuromodulation for several compelling reasons. First, our approach provides a synergistic and personalized treatment strategy to combat neurocognitive disorders. In addition, neuronavigation reduces the risk of the spread of stimulation and optimizes treatment efficacy. This personalized approach makes it possible to monitor changes in brain activity and connectivity patterns in real-time, facilitating adaptive adjustment of the stimulation protocol and ensuring lasting therapeutic benefits.

This methodological innovation represents a significant advance in the field of neuromodulation and offers a transformative approach to overcoming the challenges of neurocognitive disorders.

5. Conclusions

Disruptions in synaptic plasticity and long-range structural and functional connectivity correlated with aberrant cortico-cortical neuronal networks, also known as functional disconnection syndromes, are involved in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease. People with early Alzheimer’s disease often show increased spontaneous brain oscillations and increased synchronization over long distances compared to controls. Non-invasive brain stimulation can selectively induce neuroplasticity within the stimulated brain area, resulting in focal and selective functional depression or excitation that is transmitted to other, distant, interconnected networks. Therefore, NIBS can be used to treat Alzheimer’s disease by inducing compensatory changes in the pathological neuronal circuits, thus supporting the restoration of the neuronal mechanisms responsible for these maladaptations. NIBS is thought to be effective and safe and may promote cognitive function while delaying the progression of Alzheimer’s disease with fewer side effects.

We hypothesized that impaired mechanisms of spike-timing-dependent plasticity may lead to cognitive impairment and memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease. We have reviewed the potential impact of disrupted STDP mechanisms on memory and cognitive function in AD and the therapeutic potential of restoring these mechanisms. In summary, the present studies provide valuable insights into neuronal plasticity in the context of aging and Alzheimer’s disease. The results support the hypothesis that the application of ccPAS can improve cortical plasticity in the elderly, potentially leading to improved motor performance. Future advances in this area could lead to the development of highly effective TMS-based recovery strategies specifically designed for aging populations.

The efficacy of such strategies could be greatly enhanced by the use of neuronavigation techniques that utilize the patient’s actual brain mask derived from structural MRI data and refined with resting-state fMRI localizers. The seamless integration of individualized imaging data with ccPAS targeting represents a paradigm shift in neuromodulation research, ushering in a new era of precision medicine tailored to the unique neuroanatomical and functional characteristics of each patient. By harnessing the power of ccPAS and neuronavigation, we can enhance treatment precision and efficacy and pave the way for personalized and targeted interventions that hold great promise for improving patient outcomes in the field of neurological rehabilitation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D.F., and S.P.; literature review, C.D.F., and S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.D.F., M.T., and S.P.; writing—review and editing, C.D.F., M.S., A.N., S.P.; visualization, M.T., and S.P.; supervision; all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mai, S. Mechanisms in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Role of Non-Pharmacological Interventions in Improving Neurodegeneration and Its Clinical Correlates: A Review. arXiv Prepr. 2023.

- Antonenko, D.; Thams, F.; Uhrich, J.; Dix, A.; Thurm, F.; Li, S.-C.; Grittner, U.; Flöel, A. Effects of a Multi-Session Cognitive Training Combined With Brain Stimulation (TrainStim-Cog) on Age-Associated Cognitive Decline - Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Phase IIb (Monocenter) Trial. Front. Aging Neurosci., 2019, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria Lopez, J.A.; González, H.M.; Léger, G.C. Alzheimer’s Disease. Handb. Clin. Neurol., 2019, 167, 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimers. Dement. 2023 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. 2023, 19, 1598–1695. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilberzwige-Tal, S.; Gazit, E. Go with the Flow-Microfluidics Approaches for Amyloid Research. Chem. Asian J., 2018, 13, 3437–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanzio, M.; Torta, D.M.E.; Sacco, K.; Cauda, F.; D’Agata, F.; Duca, S.; Leotta, D.; Palermo, S.; Geminiani, G.C. Unawareness of Deficits in Alzheimer’s Disease: Role of the Cingulate Cortex. Brain, 2011, 134 Pt 4, 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amanzio, M.; D’Agata, F.; Palermo, S.; Rubino, E.; Zucca, M.; Galati, A.; Pinessi, L.; Castellano, G.; Rainero, I. Neural Correlates of Reduced Awareness in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living in Frontotemporal Dementia. Exp. Gerontol., 2016, 83, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, L.; Theou, O.; Rockwood, K.; Andrew, M.K. Relationship between Frailty and Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers: A Scoping Review. Alzheimer’s Dement. (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2018, 10, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, M.; Wills, Z.; Chu, C.T. Excitatory Dendritic Mitochondrial Calcium Toxicity: Implications for Parkinson’s and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Neurosci., 2018, 12, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vik-Mo, A.O.; Bencze, J.; Ballard, C.; Hortobágyi, T.; Aarsland, D. Advanced Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy and Small Vessel Disease Are Associated with Psychosis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, England June 2019, pp 728–730. [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. A Theory of Cortical Responses. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. B, Biol. Sci., 2005, 360, 815–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, N.; Dan, Y. Spike Timing-Dependent Plasticity: A Hebbian Learning Rule. Annu. Rev. Neurosci., 2008, 31, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montague, P.R.; Dayan, P.; Sejnowski, T.J. A Framework for Mesencephalic Predictive Hebbian Learning. J. Neurosci., 1996, 76, 1936–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miniussi, C.; Harris, J.A.; Ruzzoli, M. Modelling Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation in Cognitive Neuroscience. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev., 2013, 37, 1702–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lioumis, P.; Rosanova, M. The Role of Neuronavigation in TMS-EEG Studies: Current Applications and Future Perspectives. J. Neurosci. Methods, 2022, 380, 109677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romei, V.; Chiappini, E.; Hibbard, P.B.; Avenanti, A. Empowering Reentrant Projections from V5 to V1 Boosts Sensitivity to Motion. Curr. Biol., 2016, 26, 2155–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiappini, E.; Silvanto, J.; Hibbard, P.B.; Avenanti, A.; Romei, V. Strengthening Functionally Specific Neural Pathways with Transcranial Brain Stimulation. Current biology : CB, England July 2018, pp R735–R736. [CrossRef]

- Chiappini, E.; Borgomaneri, S.; Marangon, M.; Turrini, S.; Romei, V.; Avenanti, A. Driving Associative Plasticity in Premotor-Motor Connections through a Novel Paired Associative Stimulation Based on Long-Latency Cortico-Cortical Interactions. Brain stimulation, United States 2020, pp 1461–1463. [CrossRef]

- Borgomaneri, S.; Zanon, M.; Di Luzio, P.; Romei, V.; Tamietto, M.; Avenanti, A. Driving Associative Plasticity in Temporo-Occipital Back-Projections Improves Visual Recognition of Emotional Expressions. Nat. Commun. 2022; Under review. [Google Scholar]

- Veniero, D.; Bortoletto, M.; Miniussi, C. Cortical Modulation of Short-Latency TMS-Evoked Potentials. Front. Hum. Neurosci., 2012, 6, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buch, E.R.; Johnen, V.M.; Nelissen, N.; O’Shea, J.; Rushworth, M.F.S. Noninvasive Associative Plasticity Induction in a Corticocortical Pathway of the Human Brain. J. Neurosci., 2011, 31, 17669–17679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauwels, L.; Chalavi, S.; Swinnen, S.P. Aging and Brain Plasticity. Aging (Albany. NY)., 2018, 10, 1789–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, S.N.; Barnes, C.A. Neural Plasticity in the Ageing Brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci., 2006, 7, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, G.; Ponzo, V.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Caltagirone, C.; Veniero, D. Hebbian and Anti-Hebbian Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity of Human Cortico-Cortical Connections. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci., 2013, 33, 9725–9733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, F.; Ponzo, V.; Motta, C.; Bonnì, S.; Picazio, S.; Caltagirone, C.; Bozzali, M.; Martorana, A.; Koch, G. Impaired Spike Timing Dependent Cortico-Cortical Plasticity in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. J. Alzheimer’s Dis., 2018, 66, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrini, S.; Bevacqua, N.; Cataneo, A.; Chiappini, E.; Fiori, F.; Candidi, M.; Avenanti, A. Transcranial Cortico-Cortical Paired Associative Stimulation (CcPAS) over Ventral Premotor-Motor Pathways Enhances Action Performance and Corticomotor Excitability in Young Adults More than in Elderly Adults. Front. Aging Neurosci., 2023, 15, 1119508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrini, S.; Bevacqua, N.; Cataneo, A.; Chiappini, E.; Fiori, F.; Battaglia, S.; Romei, V.; Avenanti, A. Neurophysiological Markers of Premotor-Motor Network Plasticity Predict Motor Performance in Young and Older Adults. Biomedicines, 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momi, D.; Neri, F.; Coiro, G.; Smeralda, C.; Veniero, D.; G, S.; A, R.; A, P.-L.; S, R.; E, S. Cognitive Enhancement via Network-Targeted Cortico-Cortical Associative Brain Stimulation. Cereb. Cortex, 2020, 30, 1516–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Pavon, J.C.; San Agustín, A.; Wang, M.C.; Veniero, D.; Pons, J.L. Can We Manipulate Brain Connectivity? A Systematic Review of Cortico-Cortical Paired Associative Stimulation Effects. Clin. Neurophysiol. Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol., 2023, 154, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidarpanah, A. A Review of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation and Alzheimer’s Disease. arXiv Prepr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menardi, A.; Rossi, S.; Koch, G.; Hampel, H.; Vergallo, A.; Nitsche, M.A.; Stern, Y.; Borroni, B.; Cappa, S.F.; Cotelli, M.; et al. Toward Noninvasive Brain Stimulation 2.0 in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ageing Res. Rev., 2022, 75, 101555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buss, S.S.; Fried, P.J.; Pascual-Leone, A. Therapeutic Noninvasive Brain Stimulation in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. Curr. Opin. Neurol., 2019, 32, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teselink, J.; Bawa, K.K.; Koo, G.K.; Sankhe, K.; Liu, C.S.; Rapoport, M.; Oh, P.; Marzolini, S.; Gallagher, D.; Swardfager, W.; et al. Efficacy of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation on Global Cognition and Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Ageing Res. Rev., 2021, 72, 101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).