1. Introduction

Chikungunya (CHIKV) is an arbovirus of the family Togaviridae and the genus Alphavirus and is transmitted by Aedes. Children infected with chikungunya may exhibit distinct clinical and laboratory symptoms in comparison to adults. While both age groups may experience fever, headache, and muscle pain during the acute phase, adults are more likely to develop rheumatological symptoms [

1]. Neurological complications, however, are more frequent in pediatric patients, which represents a threat to this particular population [

2].

When diagnosing viral encephalitis, the accuracy of complementary tests is influenced by several factors. CHIKV genomic RNA is detectable at the time of symptom onset and then declines to undetectable levels within 7 days. Serological diagnosis using IgM antibodies is a more sensitive diagnostic technique in the later stages of illness (> 7 days) [

3]. Positive IgM results must be confirmed by a plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) to avoid false positives resulting from non-specific reactivity [

4]. Neuroimaging is usually necessary, but the findings in chikungunya cases are often diverse and nonspecific [

5].

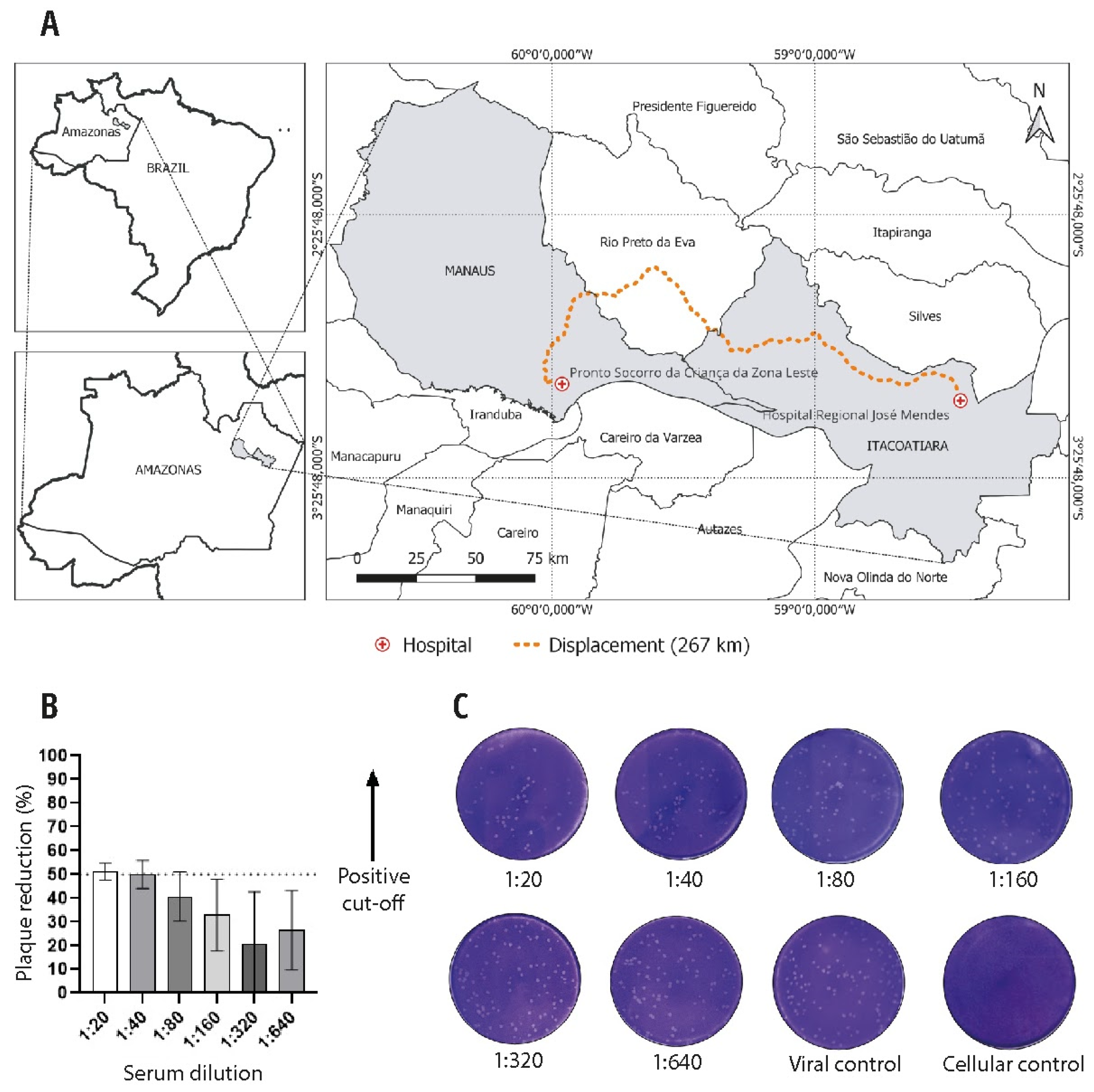

In an endemic zone for simultaneous transmission of arboviruses, we describe a neurological manifestation of a chikungunya infection in a 9-year-old male from Itacoatiara (3.1350° S, 58.4386° W), which is located in the central-eastern region of the Amazonas state, Brazil. He needed to be transferred to Manaus (3.1190° S, 60.0217° W), the state capital, for specialized medical care.

2. Case Report

A 9-year-old male, weighing 33 kg, presented with an acute headache and fever for two days, without flu symptoms, on May 28th, 2021. He is autistic suffers from epilepsy and uses phenobarbital daily. At time of admission, he had not had a seizure for more than eight years. On the 2nd day of the onset of symptoms (DOS), he presented generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS) without sphincter muscle relaxation in the postictal phase, but no medical care was provided. On the 10th DOS, he presented severe GTCS, dysarthria, loss of the nasolabial fold, and generalized weakness. The patient presented to the emergency room (ER) at the Hospital Regional José Mendes, Itacoatiara, Amazonas, and hematologic and urinalysis examinations did not show significant alterations. The pediatrician prescribed levetiracetam and other symptomatic drugs. However, for six days, no improvement in neurological symptoms was observed. On the 14th DOS, after traveling 267 kilometers to the Pronto Socorro da Criança da Zona Leste, Manaus, Amazonas (

Figure 1A), he was admitted to the ER with a focal seizure (lips), dysarthria, and loss of overall muscle strength, without signs of meningeal irritation or fever. Diazepam and phenytoin were administered endovenously for stabilization. Urinalysis and hematologic and metabolic tests showed no anemia, uremia, electrolyte imbalance, or hypoglycemia (

Table S1). Blood smears were performed for Plasmodium sp., which were negative. An emergency computed tomography (CT) brain scan without contrast presented no abnormalities. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was carried out, with a negative PCR for tuberculosis, and no fungi were identified in the sample. The cytological and biochemical analysis of the CSF was regular. However, despite the pharmacological intervention, he presented with GTCS and fever within the first two days of admission. The administration of phenobarbital was initiated at a dose of 5.5 mg/kg/day and the dosage of phenytoin was increased to 7.5 mg/kg/day. The child responded well, there were no seizures or fever from that point on, and there was a slow recovery of overall muscle strength. The presence of arboviruses was checked in serum and liquor samples on the 1st day of hospital admission (DHA), specifically on the 14th DOS. Using qPCR, serum and liquor samples were tested for dengue, Zika, chikungunya, and West Nile virus, while only serum samples were tested for Mayaro and Oropouche. However, all qPCR tests were negative. Blood and CSF samples were also examined for the presence of dengue, Zika, and chikungunya. The results indicated that the patient was positive for chikungunya when tested using ELISA IgM and negative for IgG. The presence of IgM and IgG antibodies to chikungunya in CSF was detected, and the neutralizing antibodies (NAb) against chikungunya reached an adequate threshold (PRNT-50 positive in titers of 1:40) (

Figure 1B-C), thus indicating that it was a viral encephalitis caused by this pathogen. During hospitalization, he developed bacterial pneumonia and received broad-spectrum antibiotics. Cultures of blood showed growth of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, which was conducted under sedation, using sagittal T1-weighted, axial T2-weighted, FLAIR, diffusion, and T2-GRE sequences, revealed no abnormalities in the brain. On the day of his hospital discharge (10th DHA), he had no fever, focal parrhesia, or recent seizures, with improved general muscle strength. The pediatrician prescribed antibiotics, phenobarbital, and symptomatic medication. He was subsequently assisted by a team comprising neurologists, pediatricians and a physiotherapist, in order to achieve complete recovery from his weakness.

3. Discussion

Neurological symptoms are the most frequent atypical presentation in cases of chikungunya virus [

2]. In our report, the child presented acute headache, fever, and GTCS, followed by generalized muscular weakness, dysarthria, and sleepiness. Strictly speaking, encephalitis is a pathological diagnosis; however, in a clinical routine, it can be diagnosed in an encephalopathic patient if there is surrogate evidence of brain inflammation, as detected by molecular biology, CSF serology, or even neuroimaging [

6]. In our case, indirect routes (serology, PRNT) were used to detect viral actions because it may not be detected in the first diagnostic approach, but it is not a definitive method for confirming the diagnosis [

7]. The IgM-ELISA antibodies and the positive titer of neutralizing antibodies in CSF may be enough to characterize viral encephalitis related to chikungunya in a subacute neurological patient.

Comorbidities do not necessarily determine the severity of chikungunya-associated encephalitis in young patients [

2]. However, in individuals with epilepsy, there may be abnormal patterns involving neurotransmitters [

8]. Our patient with epilepsy presented refractory seizures that necessitated the use of both phenytoin and barbituric drugs. Antiseizure medications could play a crucial role in preventing brain damage and aiding brain recovery during the acute phase. Further research into this interaction is essential for developing therapeutic agents that target the virus or early inflammatory mechanisms so as to potentially prevent progression of epileptogenesis.

The absence of suggestive findings in a laboratory and radiology approach must not rule out the hypothesis of encephalitis caused by an arbovirus. Electroencephalography is rarely helpful [

6] and was not performed. Brain MRI was not available and a CT brain scan without contrast enhancement in the ER showed no alterations. The regular CSF analysis was also used in two pediatric patients with acute seizures and poor feeding related to chikungunya [

9]. An extensive panel of viral investigation via qPCR in serum and CSF detected no presence of virus. Collecting samples for qPCR at <6 days after the onset of illness is widely recommended [

4,

7]; however, in the face of encephalitis, it is unclear how the viremia and its diffusion to the central nervous system behaves. An animal model showed that the viremia titer was age-dependent, being higher and more persistent in younger mice, and that viremia behaved differently in the CNS than in the blood [

10]. Therefore, given the logistical and access difficulties and these hypotheses, research using qPCR in both sites seems reasonable. Although negative, they lead to serological tests on a patient’s serum in the subacute clinical phase.

Chikungunya IgM serology was positive 14 days after the onset of symptoms. Persistence of the IgM molecule for up to 35 months after the primary infection has already been reported [

11], so its use in diagnosis should be cautious. The central nervous system is considered an immune privileged site, i.e., antibody access to these tissues is blocked by the barrier created by microvascular endothelial cells and other types of supporting cells [

12]. In humans, B cells and plasma cells are rarely found in parenchyma, they are more frequent in the choroid plexus, perivascular spaces and meninges [

13]. In an animal model, brain CHIKV infection spreads to the choroid plexus, ependymal walls and leptomeninges [

14]. Our hypothesis is that the antigenic stimulus in these sites, where there are naturally B lymphocytes, can explain the production of IgM antibodies in the central nervous system itself and their presence in the CSF, as confirmed by PRNT with strong titration. Therefore, these titers were essential to confirm chikungunya-associated encephalitis.

This case presented some limitations. Firstly, the absence of contrast enhancement in brain MRI scans may affect the global accuracy when defining inflammatory lesions of arbovirus-associated encephalitis. Gadolinium can enhance the visibility of lesions by increasing the contrast between normal and abnormal tissue. Furthermore, the search for arboviruses occurred during a subacute clinical period, which may affect the sensibility for the detection of arboviruses when using molecular biology. Serological methods can be a useful tool in a convalescent phase. As such, this report aims to inform the medical community that the diagnosis of encephalitis requires a particular set of techniques to reach the diagnosis.

4. Conclusions

Our report is the first confirmed autochthonous case of chikungunya in Itacoatiara, Amazonas, Brazil. It reinforces the thinking that the arboviruses often present diffuse and misunderstood circulation in the Amazon. This atypical pediatric manifestation must lead health providers in this region to think about arbovirus-associated encephalitis when a patient presents with fever with some neurological symptoms. No confirmed reports in a community should not be enough to rule out arboviral-associated encephalitis. Our efforts could decrease long-term problems related to a late diagnosis. It could also be a subsidy to reinforce specific laboratory diagnostic actions aimed at reducing the delay or underdiagnosis of this arbovirus.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Laboratory exams and neuroimaging findings in a 9-year-old male with encephalitis caused by chikungunya.

Author Contributions

S.B.A.O. was responsible for Patient follow-up, Writing—original draft; B.A.C. was responsible for Methodology, Writing—review & editing; M.T.L., A.V.S.N, and J.S.M.C were responsible for Methodology & Writing; M.S.B and W.M.M. were responsible for Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review; V.S.S. was responsible for Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. The manuscript was reviewed by all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES); Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Amazonas, grants: PCTI-EMERGESAÚDE/AM – Call II – ÁREAS PRIORITÁRIAS Call No. 006/2020, Call No. 006/2019 - UNIVERSAL AMAZONAS, RESOLUÇÃO No. 002/2008, 007/2018 and 005/2019 - PRÓ-ESTADO and “VSS and WMM were funded by research productivity fellowships (PQ) from CNPq and from Call No. 003/2022 - PRODOC/FAPEAM.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Fundação de Medicina Tropical Dr. Heitor Vieira Dourado (protocol code 80866017.8.0000.0005 12/04/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the subject involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, (V.S.S.) upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Imad, H.A.; Phadungsombat, J.; Nakayama, E.E.; Suzuki, K.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Afaa, A.; et al. Clinical Features of Acute Chikungunya Virus Infection in Children and Adults during an Outbreak in the Maldives. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021, 105, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, R.; Gerardin, P.; de Brito, C.A.A.; Soares, C.N.; Ferreira, M.L.B.; Solomon, T. The neurological complications of Chikungunya virus: A systematic review. Rev Med Virol. 2018, 28, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, V.; Ravi, V.; Desai, A.; Parida, M.; Powers, A.M.; Johnson, B.W. Utility of IgM ELISA, TaqMan real-time PCR, reverse transcription PCR, and RT-LAMP assay for the diagnosis of Chikungunya fever. J Med Virol. 2012, 84, 1771–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, B.W.; Russell, B.J.; Goodman, C.H. Laboratory diagnosis of chikungunya virus infections and commercial sources for diagnostic assays. J Infect Dis. 2016, 214, S471–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramli, N.M.; Bae, Y.J. Structured Imaging Approach for Viral Encephalitis. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2023, 33, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunkel, A.R.; Glaser, C.A.; Bloch, K.C.; Sejvar, J.J.; Marra, C.M.; Roos, K.L.; et al. The management of encephalitis: Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008, 47, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piantadosi, A.; Kanjilal, S. Diagnostic approach for arboviral infections in the united states. J Clin Microbiol. 2020, 58, e01926–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, E.M.; Coulter, D.A. Mechanisms of epileptogenesis: a convergence on neural circuit dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013, 14, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, D.; Bose, A.; Rose, W. Acquired Neonatal Chikungunya Encephalopathy. Indian J Pediatr. 2015, 82, 1065–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, S.A.; Lu, L.; da Rosa, A.P.; Xiao, S.Y.; Tesh, R.B. An animal model for studying the pathogenesis of chikungunya virus infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008, 79, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, D.M.D.N.; Coêlho, M.R.C.D.; Gouveia, P.A.D.C.; Bezerra, L.A.; Marques, C.D.L.; Duarte, A.L.B.P. et al. Long-Term Persistence of Serum-Specific Anti-Chikungunya IgM Antibody - A Case Series of Brazilian Patients. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2021; 54, e0855-2020. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, A. Immune Regulation of Antibody Access to Neuronal Tissues. Trends Mol Med. 2017, 23, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.W.; Yong, V.W. B cells in central nervous system disease: diversity, locations and pathophysiology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022, 22, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couderc, T.; Chrétien, F.; Schilte, C.; Disson, O.; Brigitte, M.; Guivel-Benhassine, F.; et al. A Mouse Model for Chikungunya: Young Age and Inefficient Type-I Interferon Signaling Are Risk Factors for Severe Disease. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).