Submitted:

03 June 2024

Posted:

04 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Assessments

2.2.1. Demographic and Clinical Assessment

2.2.2. Psychosocial Functioning

2.2.3. Cognitive Reserve (CR)

2.2.4. Assessment of Resilience

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

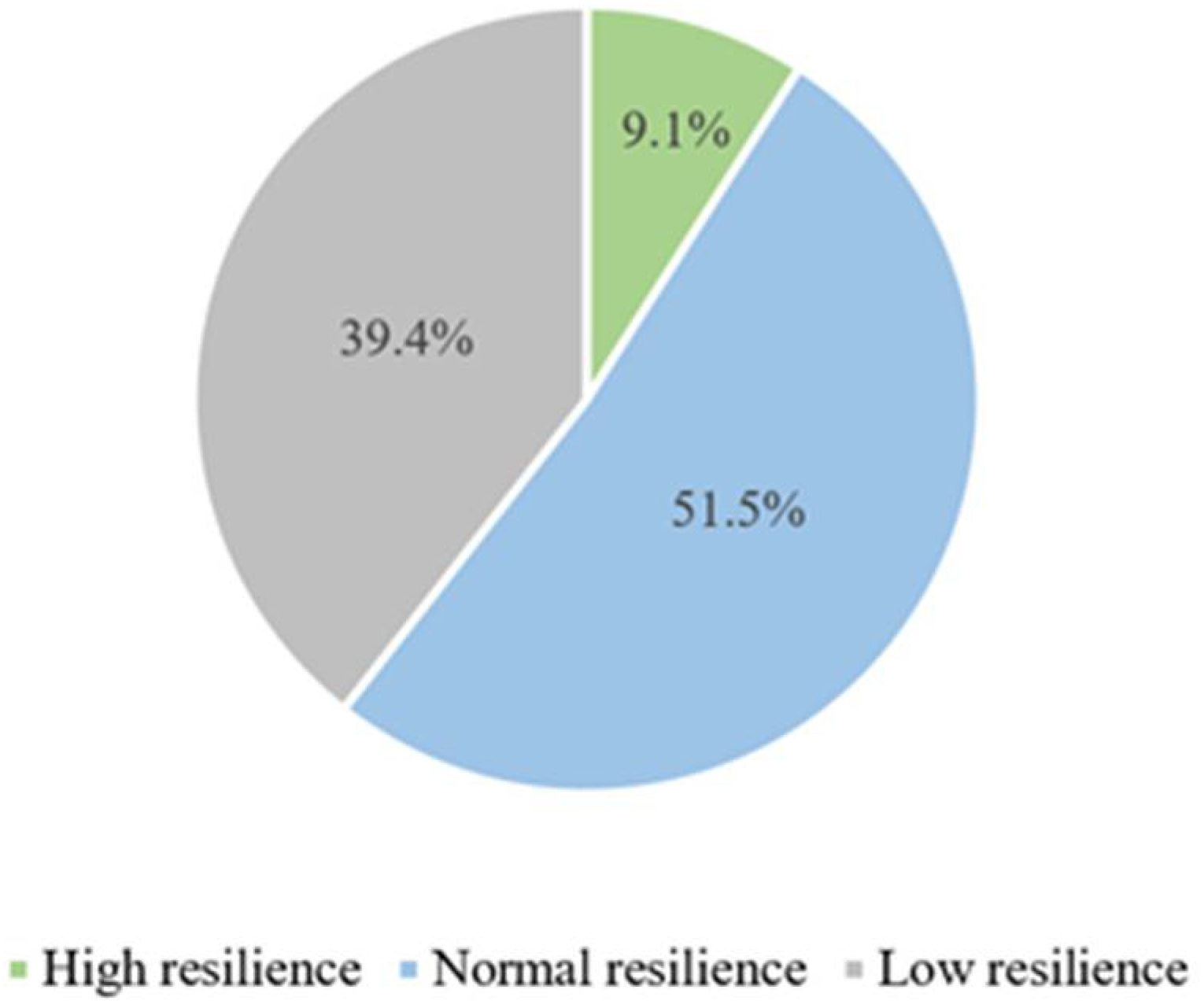

3.2. Evaluation of Resilience

3.2.1. Correlations of Resilience with Clinical and Psychosocial Variables

3.2.2. Group Analysis of Resilience

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carvalho, A.F.; Firth, J.; Vieta, E. Bipolar Disorder. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 383, 58–66. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Calabrese, J.R. Bipolar Depression: The Clinical Characteristics and Unmet Needs of a Complex Disorder. Curr Med Res Opin 2019, 35, 1993–2005. [CrossRef]

- Brietzke, E.; Cerqueira, R.O.; Soares, C.N.; Kapczinski, F. Is Bipolar Disorder Associated with Premature Aging? Trends Psychiatry Psychother 2019, 41, 315–317. [CrossRef]

- Sajatovic, M.; Strejilevich, S.A.; Gildengers, A.G.; Dols, A.; Al Jurdi, R.K.; Forester, B.P.; Kessing, L.V.; Beyer, J.; Manes, F.; Rej, S.; et al. A Report on Older-Age Bipolar Disorder from the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force. Bipolar Disord 2015, 17, 689–704.

- Dols, A.; Sajatovic, M. What Is Really Different about Older Age Bipolar Disorder? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2024, 82, 3–5. [CrossRef]

- Vasudev, A.; Thomas, A. “Bipolar Disorder” in the Elderly: What’s in a Name? Maturitas 2010, 66, 231–235. [CrossRef]

- Lavin, P.; Rej, S.; Olagunju, A.T.; Teixeira, A.L.; Dols, A.; Alda, M.; Almeida, O.P.; Altinbas, K.; Balanzá-Martínez, V.; Barbosa, I.G.; et al. Essential Data Dimensions for Prospective International Data Collection in Older Age Bipolar Disorder (OABD): Recommendations from the GAGE-BD Group. Bipolar Disord 2023, 25, 554–563. [CrossRef]

- Sajatovic, M.; Eyler, L.T.; Rej, S.; Almeida, O.P.; Blumberg, H.P.; Forester, B.P.; Forlenza, O. V.; Gildengers, A.; Mulsant, B.H.; Strejilevich, S.; et al. The Global Aging & Geriatric Experiments in Bipolar Disorder Database (GAGE-BD) Project: Understanding Older-Age Bipolar Disorder by Combining Multiple Datasets. Bipolar Disord 2019, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Beunders, A.J.M.; Orhan, M.; Dols, A. Older Age Bipolar Disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2023, 36, 397–404. [CrossRef]

- Sajatovic, M.; Rej, S.; Almeida, O.P.; Altinbas, K.; Balanzá-Martínez, V.; Barbosa, I.G.; Beunders, A.J.M.; Blumberg, H.P.; Briggs, F.B.S.; Dols, A.; et al. Bipolar Symptoms, Somatic Burden and Functioning in Older-Age Bipolar Disorder: A Replication Study from the Global Aging & Geriatric Experiments in Bipolar Disorder Database (GAGE-BD) Project. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2024, 39. [CrossRef]

- Eyler, L.T.; Briggs, F.B.S.; Dols, A.; Rej, S.; Almeida, O.P.; Beunders, A.J.M.; Blumberg, H.P.; Forester, B.P.; Patrick, R.E.; Forlenza, O. V; et al. Symptom Severity Mixity in Older-Age Bipolar Bisorder: Analyses From the Global Aging and Geriatric Experiments in Bipolar Disorder Database (GAGE-BD). Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2022. [CrossRef]

- Montejo, L.; Torrent, C.; Jiménez, E.; Martínez-Arán, A.; Blumberg, H.P.; Burdick, K.E.; Chen, P.; Dols, A.; Eyler, L.T.; Forester, B.P.; et al. Cognition in Older Adults with Bipolar Disorder: An ISBD Task Force Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Based on a Comprehensive Neuropsychological Assessment. Bipolar Disord 2022, 24, 115–136. [CrossRef]

- Orhan, M.; Huijser, J.; Korten, N.; Paans, N.; Regeer, E.; Sonnenberg, C.; van Oppen, P.; Stek, M.; Kupka, R.; Dols, A. The Influence of Social, Psychological, and Cognitive Factors on the Clinical Course in Older Patients with Bipolar Disorder. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2021, 36, 342–348. [CrossRef]

- Velosa, J.; Delgado, A.; Finger, E.; Berk, M.; Kapczinski, F.; de Azevedo Cardoso, T. Risk of Dementia in Bipolar Disorder and the Interplay of Lithium: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2020. [CrossRef]

- Dols, A.; Beekman, A. Older Age Bipolar Disorder. Clin Geriatr Med 2020, 36, 281–296.

- Subramaniam, H.; Dennis, M.S.; Byrne, E.J. The Role of Vascular Risk Factors in Late Onset Bipolar Disorder. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007, 22, 733–737. [CrossRef]

- Färber, F.; Rosendahl, J. Trait Resilience and Mental Health in Older Adults: A Meta-Analytic Review. Personal Ment Health 2020, 14, 361–375. [CrossRef]

- Laird, K.T.; Lavretsky, H.; Paholpak, P.; Vlasova, R.M.; Roman, M.; St Cyr, N.; Siddarth, P. Clinical Correlates of Resilience Factors in Geriatric Depression. Int Psychogeriatr 2019, 31, 193–202. [CrossRef]

- Verdolini, N.; Vieta, E. Resilience, Prevention and Positive Psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2021, 143, 281–283. [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R. What Is Resilience: An Affiliative Neuroscience Approach. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 132–150. [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.K.; Chew, Q.H.; Sim, K. Resilience in Bipolar Disorder and Interrelationships With Psychopathology, Clinical Features, Psychosocial Functioning, and Mediational Roles: A Systematic Review. J Clin Psychiatry 2023, 84. [CrossRef]

- Angeler, D.G.; Allen, C.R.; Persson, M.L. Resilience Concepts in Psychiatry Demonstrated with Bipolar Disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord 2018, 6. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Cha, B.; Jang, J.; Park, C.S.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, C.S.; Lee, S.J. Resilience and Impulsivity in Euthymic Patients with Bipolar Disorder. J Affect Disord 2015, 170, 172–177. [CrossRef]

- Şenormancı, G.; Güçlü, O.; Özben, İ.; Karakaya, F.N.; Şenormancı, Ö. Resilience and Insight in Euthymic Patients with Bipolar Disorder. J Affect Disord 2020, 266, 402–412. [CrossRef]

- Echezarraga, A.; Calvete, E.; Orue, I.; Las Hayas, C. Resilience Moderates the Associations between Bipolar Disorder Mood Episodes and Mental Health. https://journals.copmadrid.org/clysa 2022, 33, 83–90. [CrossRef]

- Friedberg, A.; Malefakis, D. Resilience, Trauma, and Coping. Psychodyn Psychiatry 2022, 50, 382–409. [CrossRef]

- Min, J.A.; Lee, C.U.; Chae, J.H. Resilience Moderates the Risk of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms on Suicidal Ideation in Patients with Depression and/or Anxiety Disorders. Compr Psychiatry 2015, 56, 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Marulanda, S.; Addington, J. Resilience in Individuals at Clinical High Risk for Psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry 2016, 10, 212–219. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Gooding, P.A.; Wood, A.M.; Tarrier, N. Resilience as Positive Coping Appraisals: Testing the Schematic Appraisals Model of Suicide (SAMS). Behaviour research and therapy 2010, 48, 179–186. [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.P.; Wu, J.Y.W.; Wang, C.S. Resilience and Quality of Life in People with Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2023, 19, 507–514. [CrossRef]

- Imran, A.; Tariq, S.; Kapczinski, F.; de Azevedo Cardoso, T. Psychological Resilience and Mood Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trends Psychiatry Psychother 2024, 46. [CrossRef]

- Sajatovic, M.; Dols, A.; Rej, S.; Almeida, O.P.; Beunders, A.J.M.; Blumberg, H.P.; Briggs, F.B.S.; Forester, B.P.; Patrick, R.E.; Forlenza, O. V.; et al. Bipolar Symptoms, Somatic Burden, and Functioning in Older-Age Bipolar Disorder: Analyses from the Global Aging & Geriatric Experiments in Bipolar Disorder Database Project. Bipolar Disord 2021, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- First, M.B.; Spitzer, R.L.; Gibbon, M.; Williams, J.B.W. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID I); Biometrics Research: New York, 1997.

- First, M.; Gibbon, M.; Spitzer, R.; Benjamin, L. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV® Axis II Personality Disorders SCID-II; American Psychiatric Association.: Washington, DC, 1997.

- Young, R.C.; Biggs, J.T.; Ziegler, V.E.; Meyer, D.A. A Rating Scale for Mania: Reliability, Validity and Sensitivity. British Journal of Psychiatry 1978, 133, 429–435. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M. A RATING SCALE FOR DEPRESSION. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960, 23, 56. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.R.; Sánchez-Moreno, J.; Martínez-Aran, A.; Salamero, M.; Torrent, C.; Reinares, M.; Comes, M.; Colom, F.; Van Riel, W.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; et al. Validity and Reliability of the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) in Bipolar Disorder. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2007, 3, 5. [CrossRef]

- Amoretti, S.; Cabrera, B.; Torrent, C.; Bonnín, C.D.M.; Mezquida, G.; Garriga, M.; Jiménez, E.; Martínez-Arán, A.; Solé, B.; Reinares, M.; et al. Cognitive Reserve Assessment Scale in Health (CRASH): Its Validity and Reliability. J Clin Med 2019, 8, 586. [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Sills, L.; Stein, M.B. Psychometric Analysis and Refinement of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-Item Measure of Resilience. J Trauma Stress 2007, 20, 1019–1028. [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a New Resilience Scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [CrossRef]

- Notario-Pacheco, B.; Solera-Martínez, M.; Serrano-Parra, M.D.; Bartolomé-Gutiérrez, R.; García-Campayo, J.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Reliability and Validity of the Spanish Version of the 10-Item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (10-Item CD-RISC) in Young Adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011, 9, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Dolores Serrano-Parra, M.; Garrido-Abejar, M.; Notario-Pacheco, B.; Bartolomé-Gutiérrez, R.; Solera-Martínez, M.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Validez de La Escala de Resiliencia de Connor-Davidson(10 Ítems) En Una Población de Mayores No Institucionalizados. Enferm Clin 2013, 23, 14–21. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, D.; Wu, M.; Yang, Y.; Xie, H.; Li, Y.; Jia, J.; Su, Y. Loneliness and Depression Symptoms among the Elderly in Nursing Homes: A Moderated Mediation Model of Resilience and Social Support. Psychiatry Res 2018, 268, 143–151. [CrossRef]

- Han, M.H.; Nestler, E.J. Neural Substrates of Depression and Resilience. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 677–686. [CrossRef]

- Denckla, C.A.; Cicchetti, D.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Seedat, S.; Teicher, M.H.; Williams, D.R.; Koenen, K.C. Psychological Resilience: An Update on Definitions, a Critical Appraisal, and Research Recommendations. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Torres, A.M.; Amoretti, S.; Enguita-Germán, M.; Mezquida, G.; Moreno-Izco, L.; Panadero-Gómez, R.; Rementería, L.; Toll, A.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, R.; Roldán, A.; et al. Relapse, Cognitive Reserve, and Their Relationship with Cognition in First Episode Schizophrenia: A 3-Year Follow-up Study. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 67, 53–65. [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y. Cognitive Reserve☆. Neuropsychologia 2009, 47, 2015–2028. [CrossRef]

- Amoretti, S.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A. Cognitive Reserve in Mental Disorders. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 49, 113–115.

- Anaya, C.; Torrent, C.; Caballero, F.F.; Vieta, E.; Bonnin, C.D.M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; CIBERSAM Functional Remediation Group Cognitive Reserve in Bipolar Disorder: Relation to Cognition, Psychosocial Functioning and Quality of Life. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2016, 133, 386–398. [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y.; Albert, M.; Barnes, C.A.; Cabeza, R.; Pascual-Leone, A.; Rapp, P.R. A Framework for Concepts of Reserve and Resilience in Aging. Neurobiol Aging 2023, 124, 100–103. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, I.; Dehning, J.; Grunze, A.; Hausmann, A. Old Age Bipolar Disorder—Epidemiology, Aetiology and Treatment. Medicina 2021, Vol. 57, Page 587 2021, 57, 587. [CrossRef]

- Lavin, P.; Buck, G.; Almeida, O.P.; Su, C.-L.; Eyler, L.T.; Dols, A.; Blumberg, H.P.; Forester, B.P.; Forlenza, O. V.; Gildengers, A.; et al. Clinical Correlates of Late-Onset versus Early-Onset Bipolar Disorder in a Global Sample of Older Adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2022, 37. [CrossRef]

- De Prisco, M.; Vieta, E. The Never-Ending Problem: Sample Size Matters. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2024, 79, 17–18. [CrossRef]

- Ilzarbe, L.; Vieta, E. The Elephant in the Room: Medication as Confounder. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 71, 6–8. [CrossRef]

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 65.67 | 6.55 | 54 | 79 |

| Years of education | 15.21 | 2.88 | 8 | 19 |

| Number of psychiatric admissions | 1.61 | 2.82 | 0 | 15 |

| Total number of episodes | 16.40 | 16.24 | 1 | 81 |

| Number of manic episodes | 1.33 | 2.25 | 0 | 11 |

| Number of hypomanic episodes | 6.86 | 8.97 | 0 | 41 |

| Number of depressive episodes | 9.63 | 9.73 | 2 | 40 |

| Number of suicide attempts | 1.06 | 1.47 | 0 | 5 |

| Duration of illness (years) | 31.81 | 14.69 | 2 | 53 |

| Total YMRS | 1.17 | 1.94 | 0 | 7 |

| Total HDRS | 5.17 | 3.07 | 0 | 11 |

| Total FAST | 22.8 | 12.12 | 2 | 42 |

| Total CRASH | 44.23 | 10.61 | 19.08 | 72.92 |

| Frequency | % | |||

| Sex (female) | 19 | 57.6 | ||

| Diagnosis | BD-I | 19 | 57.6 | |

| BD-II | 11 | 33.3 | ||

| Unspecified BD | 3 | 9.1 | ||

| Type of onset (early onset) | 28 | 84.8 | ||

| Type of first episode | Depression | 27 | 84.4 | |

| Hypomania | 2 | 6.3 | ||

| Mania | 3 | 9.4 | ||

| Employment status | Temporary sick leave | 4 | 12.9 | |

| Permanent sick leave | 12 | 38.7 | ||

| Retired | 12 | 38.7 | ||

| Active | 3 | 9.7 | ||

| Family history of psychiatric disorders | 20 | 62.5 | ||

| Suicidal ideation | 18 | 58.1 | ||

| Suicide attempts | 9 | 29.0 | ||

| Pharmacological treatment | ||||

| Mood stabilizers | 30 | 93.8 | ||

| Antipsychotics | 21 | 65.6 | ||

| Antidepressants | 14 | 43.8 | ||

| Benzodiazepines | 10 | 32.3 | ||

| YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; FAST, Functioning Assessment Short Test; CRASH, Cognitive Reserve Assessment Scale in Health; BD, Bipolar Disorder | ||||

| CD-RISC 10 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s correlation | p-value | |||

| Age | -0.14 | 0.486 | ||

| Years of education | 0.18 | 0.331 | ||

| Number of psychiatric admissions | 0.07 | 0.721 | ||

| Total number of episodes | -0.39 | 0.034* | ||

| Number of manic episodes | 0.07 | 0.721 | ||

| Number of hypomanic episodes | -0.33 | 0.148 | ||

| Number of depressive episodes | -0.62 | 0.001* | ||

| Number of suicide attempts | -0.16 | 0.532 | ||

| Duration of illness (years) | -0.08 | 0.706 | ||

| Total YMRS | -0.14 | 0.477 | ||

| Total HDRS | -0.34 | 0.070 | ||

| Total FAST | -0.61 | <0.001* | ||

| Total CRASH | 0.28 | 0.164 | ||

| Mann-Whitney U test | p-value | |||

| Sex (female) | 113.50 | 0.477 | ||

| Diagnosis | 90.50 | 0.546 | ||

| Type of onset | 66.50 | 0.860 | ||

| Family history of psychiatric disorders | 108.00 | 0.640 | ||

| Suicidal ideation | 94.50 | 0.367 | ||

| Suicide attempts | 86.50 | 0.586 | ||

| Pharmacological treatment | ||||

| Mood stabilizers | 26.00 | 0.755 | ||

| Antipsychotics | 110.00 | 0.827 | ||

| Antidepressants | 111.00 | 0.568 | ||

| Benzodiazepines | 88.50 | 0.485 | ||

| CD-RISC-10, 10 Item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; FAST, Functioning Assessment Short Test; CRASH, Cognitive Reserve Assessment Scale in Health | ||||

| Low resilience M (SD) |

Normal resilience M (SD) |

Mann-Whitney U test | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 67.62 (6.95) | 63.82 (6.45) | 73.5 | 0.121 |

| Years of education | 14.77 (3.09) | 15.71 (6.45) | 89.0 | 0.362 |

| Number of psychiatric hospital admissions | 1.17 (1.40) | 2.06 (3.70) | 87.0 | 0.663 |

| Total number of episodes | 20.42 (21.76) | 15.53 (11.40) | 84.0 | 0.769 |

| Number of manic episodes | 1.00 (1.49) | 1.64 (2.82) | 58.5 | 0.462 |

| Number of hypomanic episodes | 9.86 (14.25) | 6.36 (4.95) | 38.0 | 0.964 |

| Number of depressive episodes | 14.36 (12.71) | 7.38 (5.49) | 48.0 | 0.169 |

| Number of suicide attempts | 0.83 (0.98) | 1.30 (1.77) | 27.5 | 0.771 |

| Duration of illness (years) | 29.55 (15.99) | 27.62 (10.48) | 49.0 | 0.192 |

| Total YMRS | 1.33 (2.19) | 1.29 (1.94) | 81.0 | 0.866 |

| Total HDRS | 5.92 (3.23) | 4.80 (2.93) | 69.5 | 0.315 |

| Total FAST | 27.54 (8.49) | 19 (13.47) | 58 | 0.044* |

| Total CRASH | 39.63 (10.45) | 49.62 (9.66) | 33.5 | 0.026* |

|

Low resilience N (%) |

Normal resilience N (%) |

Chi-squared test | p-value | |

| Sex (female) | 8 (61.5) | 10 (58.8) | 0.02 | 0.880 |

| Diagnosis BD I BD II Unspecified BD |

6 (46.2) 5 (38.5) 2 (15.4) |

12 (70.6) 5 (29.4) 0 (0.0) |

3.53 |

0.171 |

| Onset type (early onset) | 10 (76.9) | 17 (100.0) | 4.36 | 0.037* |

| First episode type Depression 10 (76.9) Hypomania 2 (15.4) Mania 1 (7.7) |

14 (87.5) 0 (0.0) 2 (12.5) |

2.72 |

0.257 |

|

| Employment status Temporary sick leave 2 (16.7) Permanent sick leave 5 (41.7) Retired 5 (41.7) Active 0 (0.0) |

2 (12.5) 6 (37.5) 5 (31.3) 3 (18.8) |

2.57 |

0.462 |

|

| Family history of psychiatric disorders 6 (50.0) | 13 (76.5) | 2.18 | 0.140 | |

| Suicidal ideation | 8 (61.5) | 9 (60.0) | 0.01 | 0.934 |

| Suicide attempts | 4 (30.8) | 5 (33.3) | 0.02 | 0.885 |

| Mood stabilizers | 12 (92.3) | 15 (93.8) | 0.02 | 0.879 |

| Antipsychotics | 9 (69.2) | 10 (62.5) | 0.14 | 0.705 |

| Antidepressants | 6 (46.2) | 8 (50.0) | 0.04 | 0.837 |

| Benzodiazepines | 4 (30.8) | 5 (33.3) | 0.02 | 0.885 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).