1. Introduction

Despite significant advances in earthquake engineering in the last two decades, the seismic design codes are presently based on controlling the forces created in the structural components and displacements formed in two or more limit states for safety observation purposes. These codes do not consider the structural performance in its life-cycle in terms of cost and loss-of-life possibility; they are more based on setting some minimum values for the structure components' stiffness and strength and providing its overall safety [

1,

2,

3]. Therefore, these codes have moved towards reliability-based designs and present criteria for the performance-based design as guidelines. In performance-based earthquake engineering (PBEE), the structural performance after its construction is studied to provide appropriate performance in its life cycle [

4]. Accordingly, in such methods, more precise analyses with higher computations usually estimate the structure's nonlinear response under different intensity levels [

5,

6]. Performance-based design (PBD) starts with selecting design criteria articulated through one or more performance objectives. The first stage is how to choose the performance goals and develop an initial design accordingly. The structural design response will then be assessed and revised until the satisfactory criteria for all intended performance goals are met.

There are some performance-based optimum design (PBOD) algorithms used effectively to achieve optimal structural designs with acceptable performances, while their responses such as plastic hinge rotation and inter-story drifts are incorporated as constraints, and structural weight or cost is contemplated as the objective function [

7]. Among many researchers, Liu et al. [

8] applied a PBD method for multi-objective optimization using a genetic algorithm subject to uncertainties to provide a set of Pareto-optimal designs. Moreover, Pan et al. [

9] combined multiple design constraints into a multi-objective method using a new formulation based on the constraint approach.

These studies deal with the minimum cost while meeting the minimum requirements set out in the design regulations and constraints. However, they may not necessarily lead to an economical design with the lowest total cost over the lifetime of the structure. This highlights the need to improve the design approach to reduce economic losses to an acceptable level while protecting human lives. To this end, the Life Cycle Cost (LCC) based design approach has been developed to address economic concerns directly in the design process.

In recent years, LCC Analysis (LCCA) has been considered by many researchers. It measures a structure's efficiency over its whole life cycle in terms of cost. It has engaged much attention from decision-makers looking for the most cost-effective approach for constructing buildings in seismic zones [

10,

11]. Wen and Kang [

12] devised a long-term cost-benefit consideration for evaluating the expected life-cycle cost of an engineering system under multiple hazards in the early 2000s, as one of the motivating missions in this field. Later experiments were carried out to take advantage of the benefits of financial accounts in structural engineering. Takahashi et al. [

13], using a renewal model for the occurrence of earthquakes in a seismic source, formulated the estimated life-cycle cost of construction alternatives. As a decision issue, a temporal relationship between characteristic earthquakes and the methodology was extended to an actual office building.

The LCC analysis requires calculating the cost components related to the structural performance under different seismic intensity levels [

1,

14]. It is necessary to use time-history methodologies and precise numerical models to estimate the structure's seismic performance with acceptable accuracy. However, the high computational effort required in these methods and the complications that prevailed, make the optimization algorithms difficult. Therefore, to estimate the structure response, earlier researchers have used simplified methods such as pushover analysis which is known for its limitations and weaknesses in estimating the acceleration of the stories and reduced precision and reliability of the results. The importance of considering the life cycle cost as an additional objective for the primary structural cost objective function in the field of multi-objective optimization has been investigated by Fragiadakis et al. [

15]. They used pushover analysis to compare a single objective weight minimization with a performance-based two-objective design of a steel moment-resisting frame, yielding a basis for producing a Pareto front of the solutions.

To investigate the effectiveness of strengthening reinforced concrete buildings, Kappos and Dimitrakopoulos [

16] used cost-benefit and LCCA as decision-making tools. By determining initial and damage cost components for each design, Mitropoulou et al. [

1] studied the influence of the behavior factor in the final design of RC buildings under earthquake loading in terms of safety and economy. Also, they investigated multiple effects of the analysis method, the number of seismic records imposed, the performance criterion used, and the structural type on the LCC assessment of 3-D reinforced concrete structures. In addition, by using the Latin hypercube sampling method, they investigated the effect of uncertainties on the seismic response of structural systems and their impact on life-cycle cost assessments.

In recent years, the Endurance Time (ET) method, as a dynamic analysis approach that requires much less computational effort compared with other standard time-history methods, has been introduced and used in various cases [

17,

18,

19,

20].

Recently, Varaee et al. proposed an LCCA-based probabilistic optimization procedure for 3-D RC structures based on the FEMA-P-58 [

21]. Their proposed method leads to the proper distribution of materials in the structures, and also it can reduce the life cycle costs without increasing the initial costs of construction.

Asadi and Hajirasouliha [

22] developed a practical methodology for the optimum seismic design of RC frames to minimize damage and life-cycle cost based on uniform damage distribution (UDD). They demonstrate that the blind increase of the reinforcement ratio does not necessarily reduce the displacement demands and the damage costs. Mirfarhadi and Estekanchi [

23,

24] used value-based seismic design as a framework for optimal seismic design of structures considering a comprehensive set of performance indicators. In their work, design outcomes were compared to the conventional code-based design procedure minimizing the structural construction cost in terms of seismic response and consequences. Sarcheshmehpour et al. [

14] proposed a practical framework for the optimal seismic design of high-rise steel buildings in compliance with all the constraints in the design regulations. This framework was used to compare the seismic behavior of pipe-to-pipe and frame pipe systems in conventional 20 and 40-story 3-D buildings.

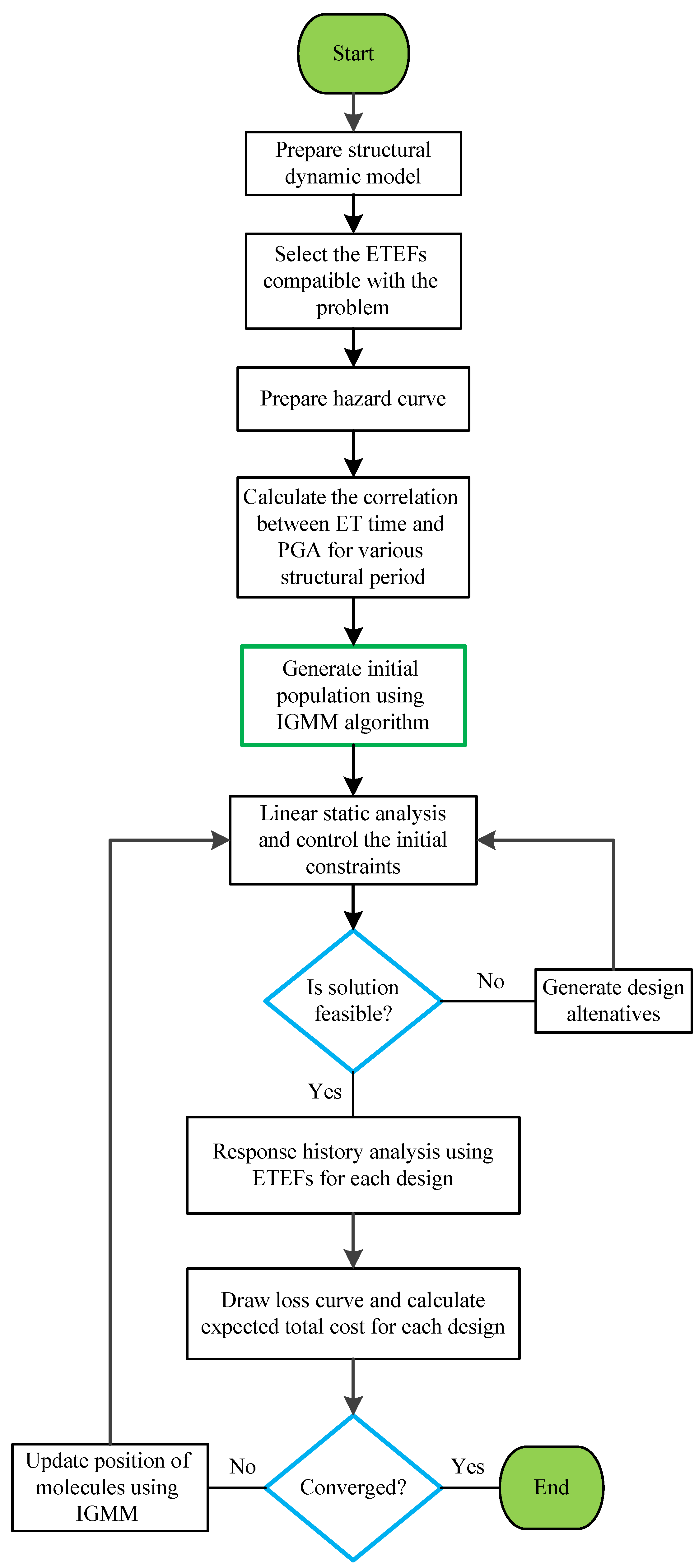

Recently, the IGMM algorithm has been used as a population-based technique based on ideal gas molecular motion, with high convergence speed and acceptable accuracy in providing a general optimal solution utilizing a relatively small number of analyses [

21,

25,

26,

27]. Therefore, the present research makes simultaneous use of the ET method and IGMM algorithm to let the seismic loss reduction criteria enter the trend of the optimum design directly. The proposed method here can help present more all-inclusive definitions of such effects as seismic damage, damage to the contents of the structure, downtime costs, and costs due to injuries and fatalities in the form of quantitative parameters.

It can be expected that the intended structure may have an acceptable performance during and after an earthquake.

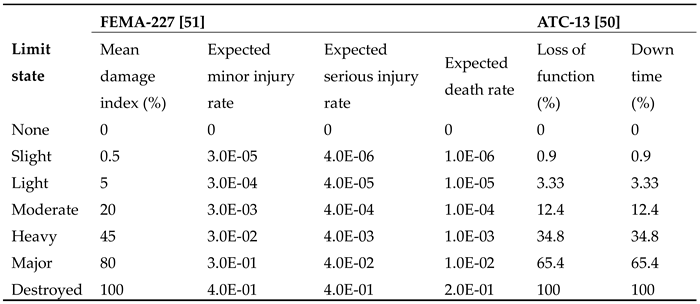

The optimization process of a 3-D four-story concrete structure is carried out in multiple steps to reduce the problem solution time. First, each response vector generated by the IGMM algorithm is controlled for the initial constraints, including the observance of the continuity of the sections' height and steel bar ratio for beams and columns. If the initial constraints are satisfied, linear analysis is allowed for the static loads. If the sections are found to respond well, a nonlinear analysis will be allowed then, and the optimization process will be continued until global convergence occurs.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: In

Section 2, the mono and multi-objective types of the IGMM algorithm are briefly described.

Section 3 explains the ET method as a dynamic time-history analysis.

Section 4 describes the methodology used for the LCCA design based on the ET method. In

Section 5, the mathematical modelling of the optimization problem is introduced. Finally, the mono and multi-objective optimization of a 3-D four-story RC building is conducted, presenting and discussing results..

3. Endurance Time Method

As a response history analysis, the Endurance Time (ET) method can measure the structural responses such as maximum displacements, inter-story drift ratios, and stresses in time steps while the intensity of the applied accelerograms is increasing. Excitation in these artificial acceleration functions begins at a low intensity and steadily increases until structural failure occurs. Moreover, this allows structural responses to be tracked through a wide range of intensities. [

4]. The ET method does, in fact, link analysis time to excitation intensity. The concept of acceleration reaction spectrum is helpful in ET for characterizing excitation intensity. ET excitation functions (ETEFs) are optimized while each time window, from zero to a particular time, generates a response spectrum that fits a template spectrum with a varying scale factor. [

39]. Many studies have shown that the currently available ETEFs provide accurate structural response estimates at various excitation intensities with minimal computational effort [

19,

40]. Various ET acceleration functions are now freely accessible on the ET method's website [

41]. In this investigation, “ETA40h” series acceleration functions are utilized as the basic accelerogram. The template spectrum of this series is the average response spectrum of seven ground motions recorded on soil type C. These motions are selected from a set of 20 earthquake records listed in FEMA440 [

42]. According to Estekanchi et al., three acceleration functions in this series, which have different starting points for optimization, can reduce the random scatter effects in the results [

17].

In the ET method, the value of the required engineering demand parameter (EDP) (e.g., drift for each story) is found over time. Then, the maximum absolute value of the EDP in the time interval [0,t] is plotted against the analysis time t. The x-coordinate axis of an ET curve is analysis time, but it is not common and, occasionally, can be confusing to evaluate and express seismic performance with time. Therefore, substituting a standard parameter such as peak ground acceleration (PGA) or return period for a time in the evaluation and expression of the performance of the structures is essential. A correlation between ET analysis time and the stated standard parameter should be determined [

43]. In this research, the problem of correlation between time and the PGA has been used

4. Design Based on the Life-Cycle Cost

To optimally design the desired structure based on the life-cycle cost, the sum of the initial construction cost and those caused by probable earthquakes during the structure's useful period for a lifetime is considered as the total life-cycle cost.

We will show that the ET analysis provides a useful tool for performing acceptable-volume economic calculations on different design alternatives. The initial construction cost and the expected earthquake loss during the structure lifetime are usually two essential parameters for making decisions [

1]. A severe obstacle in evaluating the cost of the earthquake loss is to estimate the structure response against the ground motion under different intensity levels. Different researchers have proposed different simplified seismic analysis methods to overcome the immense computational effort required to evaluate a large number of different designs. However, the cost evaluation has been used so far for comparative studies among a limited number of design alternatives. Researchers have only recently considered the direct use of the life-cycle cost in the design process [

1,

44]. The total life-cycle cost of the structure C_LC can be written as the sum of the initial cost C_IN, which is a function of the design vector s and the present value of the lifetime cost C_L which is a function of the structure lifetime t and the design vector s as in Eq. (2) [

1]. The details of which will be explained next.

4.1. LCC Calculations Based on the ET Approach

The Life-Cycle Cost (LCC) assessment in the optimization process steps through the results found from the ET analysis requires a specific procedure, the steps of which are as follows:

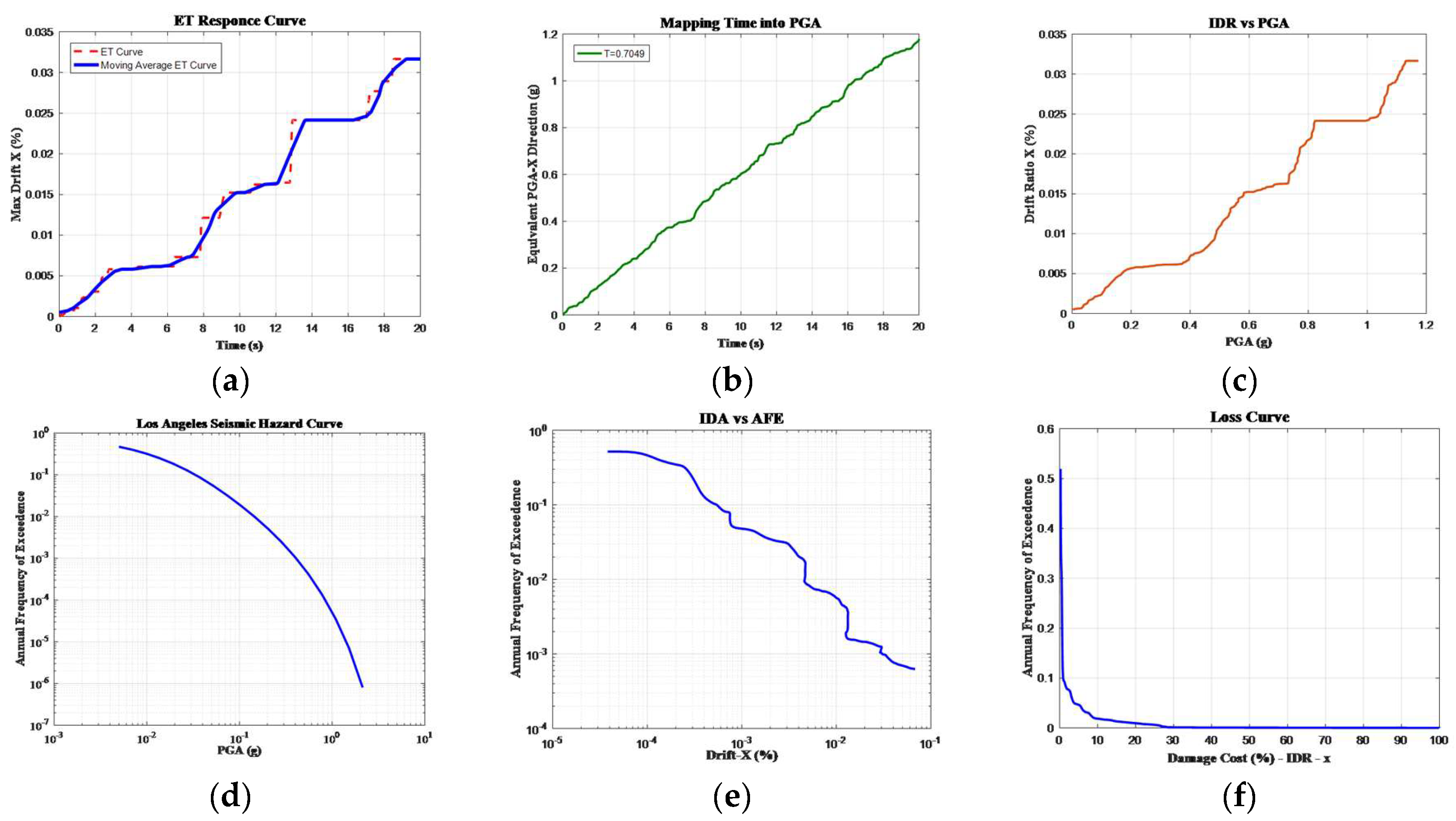

Step 1. In this step, the history of the engineering demand parameters, including the maximum inter-story drift and acceleration of the stories over time, are found through the ET analysis, presented in the form of an ET response curve, and smoothed by fitting a curve on it.

Figure 2(a). shows the ET response curve related to the history of the maximum inter-story drift for an assumed structure. It is worth mentioning that before drawing

Figure 2(a), the amounts of the responses are extracted for all the stories, and their maximum absolute values are determined.

This process is carried out for all the required demand parameters, including the maximum drift in the Y direction and the maximum acceleration in different directions.

Step 2. In this step, mapping time (in the ET curve) to PGA is done based on the procedure explained in [

38] and the curve of PGA versus time is drawn based on the fundamental period of the structure being studied (

Figure 2(b)).

Step 3. Here, the curve of the response values (e.g., the maximum drift) versus PGA is drawn, which will result in the elimination of the time factor from the relations, and PGA is substituted (

Figure 2(c)).

Step 4. In this step, the hazard curve of the region of the structure under investigation (LA in this research) is drawn based on the information obtained from the USGS Site [

45].

Figure 2(d) shows the relation between PGA and Annual Frequency Exceedance (AFE).

Step 5. Here, the relation between the structure response (maximum inter-story drift) and the AFE is created, and the PGA is omitted from the relations (

Figure 2(e)).

Step 6. In this step, the damage model is made, and the relation between the damage and the AFE is drawn. This step is for different damage components, including the costs of repairs, losing contents due to inter-story drift, losing contents due to the acceleration of stories, losing rents, losing incomes, cost of injuries, and cost of fatalities, and different damage components are found based on the explanations presented at the beginning of this chapter.

Figure 2(f) shows the loss curve of the repair costs due to the drift in direction X.

The above process is repeated many times in different optimization steps until the algorithm convergence conditions are satisfied and the optimum solution is achieved. As mentioned before, step 4 depends on the region of the structure and does not necessarily be repeated in each iteration. Figure A.1 given in

Appendix A shows the flowchart of the optimization cycle.

Next, the optimization process is carried out once single-objectively using the IGMM algorithm and bi-objectively using the MOIGMM algorithm.

4.2. Initial Cost

The initial cost is usually the cost of constructing a new structure or retrofitting an existing one. In the design example of a new 3-D moment frame RC structure being investigated, the initial cost is related to the costs of land, building materials, and the labor force needed to construct the structure. Since the costs of land and other non-structural elements are the same for all the design alternatives, they can be omitted from the total cost calculations. Therefore, the initial cost can be calculated based on Eq. (3), taking into account the reinforcement steel, concrete, and framework costs.

where

,

, and

are the unit costs of concrete, steel reinforcement, and formwork, respectively, with the corresponding values of respectively 735

$/m3, 7.1

$/kg, and 54

$/m2 [

46].

is the section area of the steel reinforcement (for beams, it is equal to the sum of the section areas of the upper and lower bars),

,

, and

are the member section dimensions, breadth, height, and length, respectively.

4.3. Useful Period of the Lifetime Cost

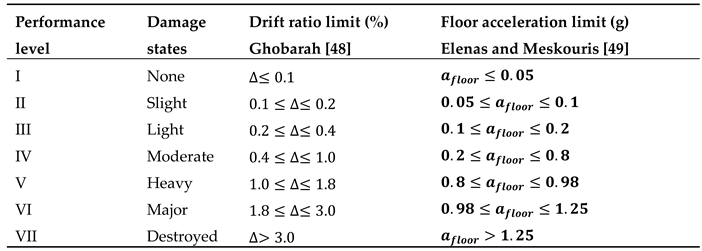

This part includes the structural costs sustained during the useful period of its lifetime. These costs are generally all-inclusive and include losses due to natural and unnatural disasters. However, in the present research, only the seismic losses caused by earthquakes have been considered lifetime costs. According to the existing technical literature, different limit states have been used considering the inter-story drift and the acceleration of the stories. These limit states (and the resulting loss) are due to the performance of the structural and non-structural elements.

The lifetime costs of a structure during its useful period may be due to many factors including natural and unnatural disasters such as seismic hazards. They may be characterized as the loss of contents itemized by the maximum inter-story drift and the floor acceleration, the damage repair cost, loss of rental cost, income cost, the cost of injuries, and the cost of human fatalities [

1,

12,

47]. As for an economic assessment of these losses, a correlation is used according to limit states suggested by Ghobarah [

48] for maximum inter-story drift ratios and a work by Elenas and Meskouris [

49] for the maximum floor accelerations, shown in Table A.1, recorded in

Appendix A. In general, the maximum inter-story drift ratio (∆) is used to calculate both structural and non-structural damages, and maximum floor acceleration (

) is used to justify the loss of contents [

47]. In order to create a continuous relationship between the damage states and costs, a piecewise linear relation is assumed. As mentioned earlier, the lifetime cost of the structure is a combination of different components. The limit state cost (

), for the i-th limit state, may be characterized as follows:

where

is the damage repair cost;

is the loss of contents cost due to the interstory-drift;

indicates the loss of contents cost due to the acceleration in each floor;

is the loss of rental cost;

signifies the cost of income loss;

is the injuries cost and

indicates the cost of human fatalities. Formulae to calculate each cost component are shown in Table A.2, noted in

Appendix A. The values of the mean damage index, loss of function, downtime, expected minor injury rate, expected serious injury rate, and expected death rate used in this study are based on ATC-13 [

50] restated in FEMA-227 [

51]. Table A.3 given in

Appendix A provides corresponding parameters for each damage state. The method, with no limitation, has the capability of incorporating detailed calculations on cost components. The expected LCC of the building is computed by summing up the present values of the annual damage costs throughout the lifetime. For convenience, the detailed procedure to calculate

for the structure, using ET method, is depicted in

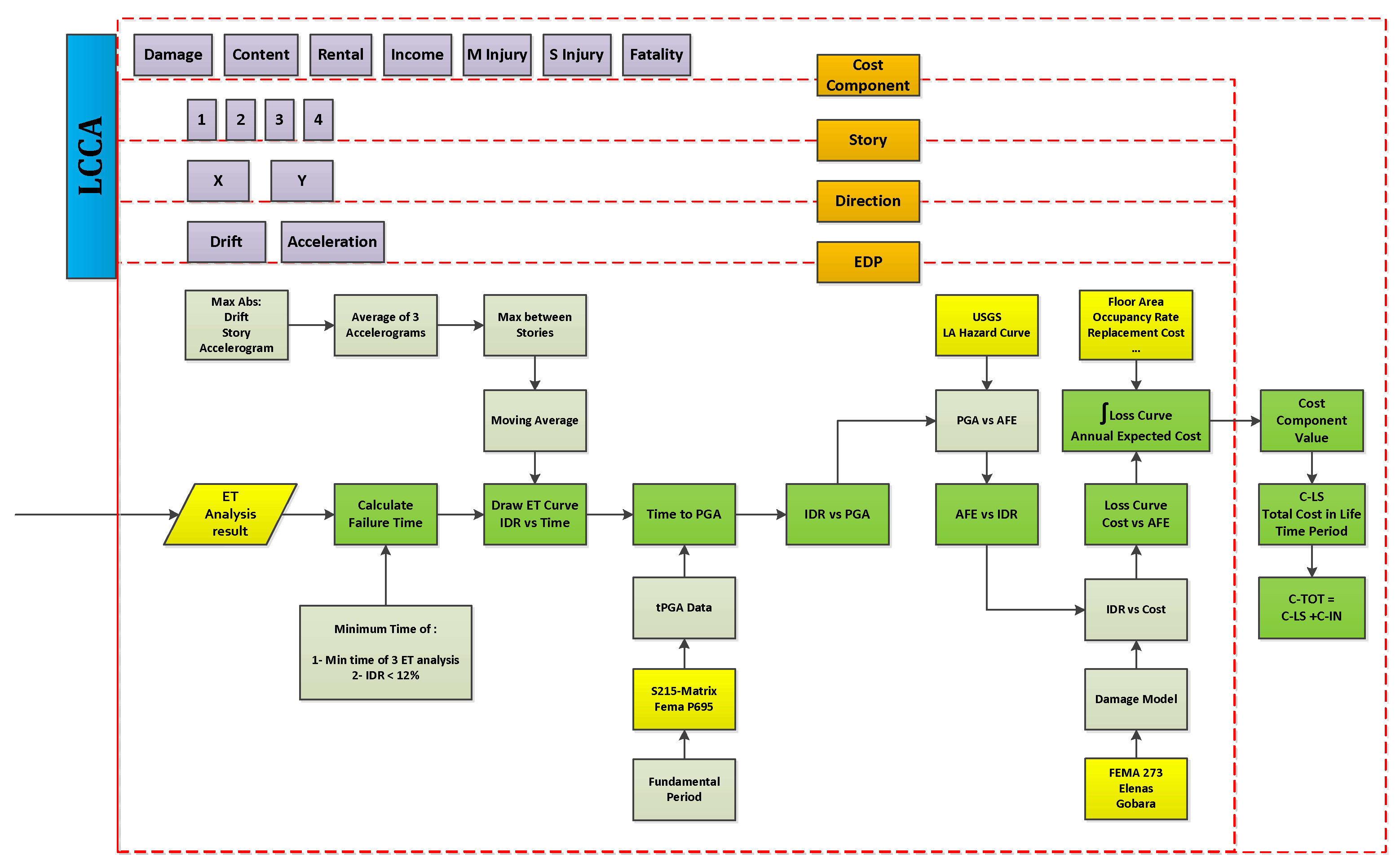

Figure 3.

If the useful structural lifetime period is assumed 50 years, Eq. (5) can be used, in the present time, to estimate the loss cost to different structural components along its useful lifetime period.

where

is the cost of the i-th damage component during the useful structural lifetime period t and ϑ is the annual discount rate (3% in this research [

4]). The structure's lifetime cost due to damage will be calculated by adding the computed present cost for each damage component. According to Eq. (2), the total life-cycle cost is equal to the total initial construction cost and the present annual cost of a useful structural lifetime period.

5. Numerical Example

5.1. Structural Model

In this research, a numerical structural model has been used, considering nonlinear material properties and deterioration. The structural analyses were carried out using the Performance-Based Earthquake Engineering (PBEE) toolbox [

52]. The Euro code 8 [

53] specifications together with the works by Fajfar and Eeri [

54] and Perus et al. [

55] were employed to define moment-rotation relations of the plastic hinges.

Some assumptions used in the nonlinear modeling process are as follows:

- –

the floor diaphragms are assumed to be rigid in their planes, and the masses and the moments of inertia are lumped at the center of gravity.

- –

The elastic elements connect all joints at the story level to the center of mass. They are used to model the rigid diaphragm at the story level, where the mass can be represented in one point. Columns contain the P-delta effect.

- –

One-component lumped plasticity elements, consisting of an elastic beam and two inelastic rotational hinges (defined by the moment–rotation relationship), are used to model beam and column flexural behaviors. The element's formulation is based on the concept of a point of inflection at the element's midpoint. The plastic hinge is only used for the main axis bending in beams. For columns, two independent plastic hinges for bending about the two principal axes are used [

56].

- –

In the present study, the elastic beam-column elements and zero-length-section elements are used to create the model. At each elevation, “rigid” elements linked all of the nodes. The TakedaDAsym uniaxial material, designed in the software OpenSees, is used for plastic hinges in beams and columns [

52].

- –

A bi-linear or tri-linear relationship is used to model the moment-rotation relationship. When determining the moment-rotation relationship for beams or columns, zero axial force and axial strain due to gravity loads are considered, respectively. After the maximum moment, a linear negative post-capping stiffness is assumed.

- –

The gravity load was modeled on beams as a uniformly distributed load and on columns as point loads. The self-weight of the slab and beams and the permanent load on the slab result in an evenly distributed load on the beams. Only the self-weight of columns is modeled using the point loads at the top of the columns.

- –

The structure can be subjected to earthquake excitations in X and/or in the Y direction. The Newmark integrator is used assuming γ=0.5 and β=0.25.

5.2. Defining the Optimization Problem

In single-objective optimization, the minimization of the total cost is considered as the objective function. Accordingly, it is required that the design alternatives satisfy certain initial constraints. Columns' strengths have a reducing trend in the building height, meaning that the dimensions of the upper columns should be equal to or smaller than those of the lower ones. Besides these constraints, all the other code-based constraints regarding the gravity loads should be satisfied too. After these are satisfied for a design alternative, the LCC analysis is done based on the ET analysis (explained in subsection 4.1). To achieve the optimum design, this algorithm generates new designs based on the initial population until the convergence criterion is reached.

The design variables are the details of the beams and columns. In a general state, include the relative section areas of the lower and upper bars ( and , respectively), beam breadth and height (b and h, respectively), and stirrups’ relative section area and spacing ( and s, respectively) among which the latter two are assumed constant in the optimization process. Their values are found based on the seismic design specifications specified in the related codes. To simplify the execution of the final design, the beams section breadth at each story level is limited to that of the columns below, and only the beams section height is defined as a discrete variable in the range 30-60 cm with 5 cm paces. Also, the relative section area of the beam's lower bars is assumed half that of the upper bars (more than the minimum permissible value specified in the related codes). Therefore, the design variables in the optimization problem include only the beam section heights and section areas of the upper bars. Also, the relative section areas of the beam reinforcement bars are defined discretely considering arrangements of 2, 3, and 4 bars 16-25 mm in diameter.

The columns details, in a general state, include the relative section area of all the column reinforcement bars (

), column section breadth and height (b and h, respectively), and stirrups’ relative section area and spacing (

and s, respectively). Similar to beams, the latter two are found based on the seismic design specifications specified in the related codes. To define the problem discretely and consider construction limitations, column section dimensions and numbers and diameters of the steel bars are shown in

Table 1, from which the optimization algorithm chooses the required values. Column sections have been assumed squares with discrete dimensions that vary with 5 cm paces. The reinforcement bars have 8, 12, and 16 setting arrangements with appropriate clear spacing between the steel bars. In defining the sections, use has been made of 16, 18, 20, 22, and 25 mm diameter bars so that the column section bar ratio lies within the permissible range specified in the related codes.

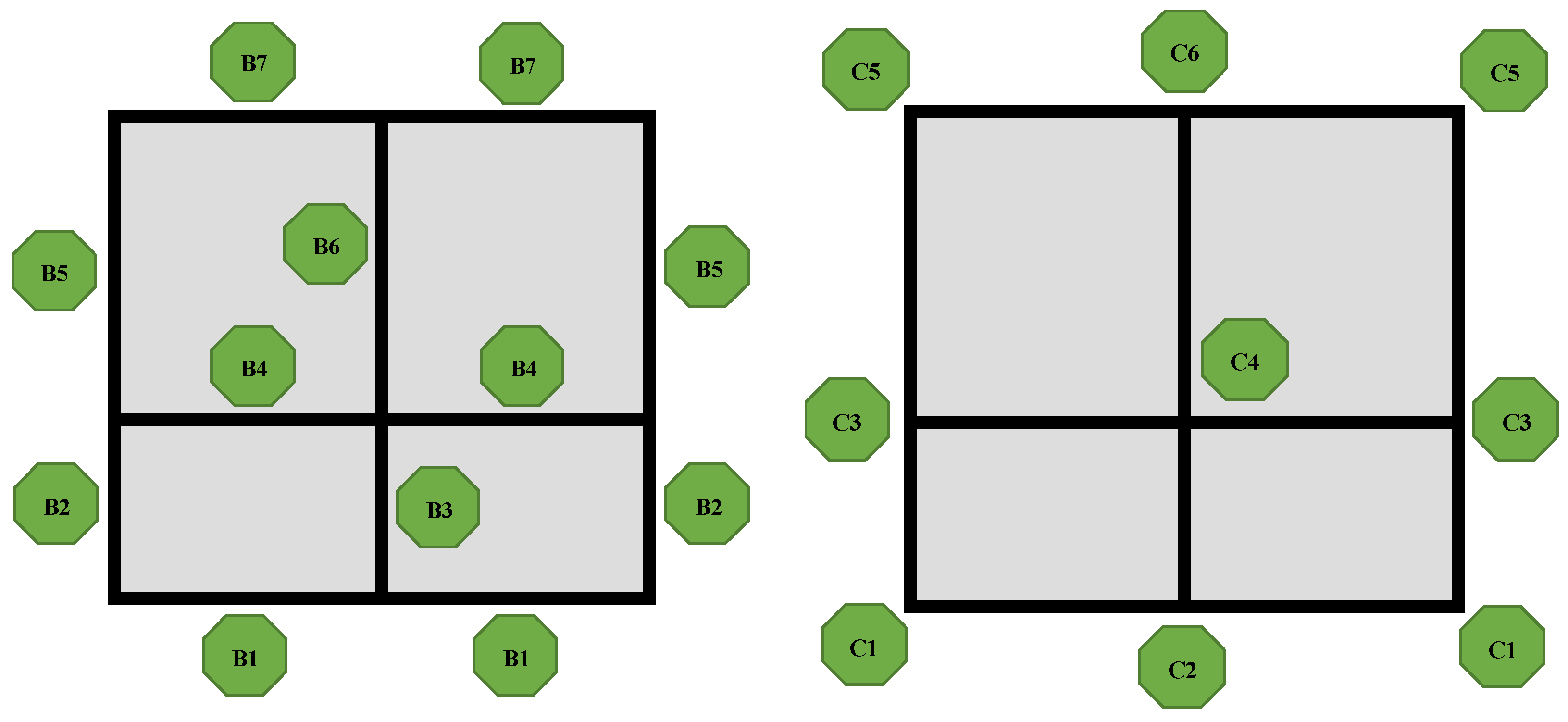

The studied case is a 3D 4-story RC structure with two spans in each direction; in direction X, the span dimensions are both equal to 5 m, and in direction Y, they are 4 and 6 m. The height of the bottom story is 3.5 m, and the height of the other stories is 3.0 m. Twelve column types (6 for stories 1 and 2 and 6 for stories 3 and 4) and 28 beam types (3 for direction X and 4 for direction Y in all different stories) have been considered due to the existing symmetry in the structure. So, there are 72 design variables for the problem, including 12 for the column sections, 4 for the beam heights, and 56 for the beam's upper steel bars (one independent variable for each end of a beam). As mentioned before, these variables can assume only predefined values. Locations of each beam (B1-B7) or column (C1-C6) section on the plan are shown in

Figure 4.

5.3. Mono-Objective Optimization

To achieve a design with the slightest variations in the initial cost, first, the structure was designed according to the ACI 318-14 [

57] provisions and observing all the existing constraints. Secondly, the range of variations of every design variable in the optimization process was determined based on the life-cycle costs. Accordingly, the permissible values the design variables can assume are provided in

Table 2. A non-stationary multi-stage assignment penalty function method is applied similar to that of [

58,

59,

60] to handle constraints

In this example, the IGMM algorithm was able to find the optimum structure with an initial population of 20 after 20 cycles which is nearly 1200 time-history analyses (three analyses for each ET response curve based on the combinations of the three pairs of accelerograms).

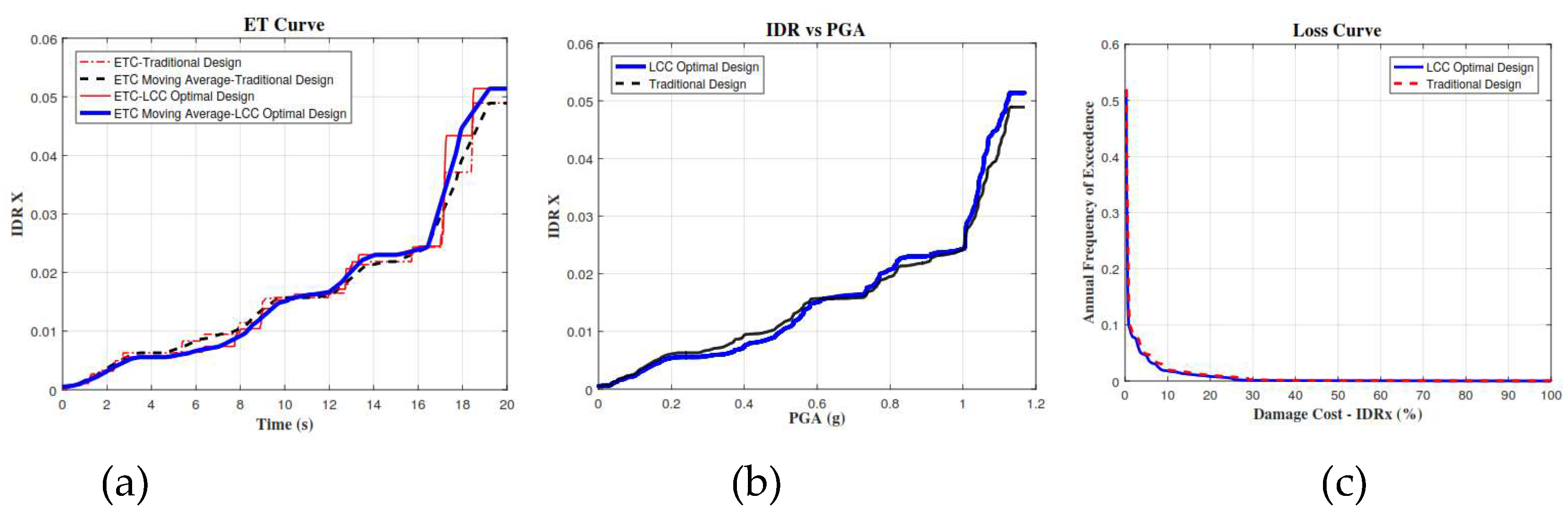

Figure 5(a) compares the response curves of the maximum inter-story drift of the ET analysis of a structure designed based on the ACI318-14 and the optimum structure designed based on the life-cycle cost, and

Figure 5(b) compares the smoothed curves of the drift versus PGA for both structures. In these curves, the drift values in lower accelerations (that have more occurrence probabilities) are less in the structure optimized based on the life-cycle cost than in the one designed based on codes.

Since drift values directly correlate with the structure damages and the related losses, this parameter can reduce the life-cycle cost.

Figure 5(c) shows the loss curve due to the drift in direction X of the two structures, one designed based on the ACI318-14 and the other optimized based on the life-cycle cost.

As shown in Figure5(c), the solid blue curve related to the latter shows smaller values. Although the difference may be negligible, considering that it shows the probable annual loss and the area under it is calculated and extended to a 50-year useful period of the lifetime, the slight reduction of this curve can considerably reduce the expected total loss.

As shown in

Table 3, the initial cost has increased from 125004

$ in the design based on conventional codes to 126302

$ in the design based on the life-cycle cost. And, as shown in

Table 4 the costs of the useful lifetime have reduced from 397192

$ in the code-based design to 345865

$ in the life-cycle cost-based design. Therefore, in general, only a 1% increase in the initial cost will result in a 13% reduction in the useful period of lifetime costs and a total 10% reduction in the total life-cycle cost of the structure being studied.

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 present the comparative information regarding the details of the lifetime period and initial costs; the percent variation of each cost parameter due to optimization is also shown in each table. Comparative three first periods and mode shapes of the code-based and LCCA based optimum design are also provided in

Table 6.

In

Table 3, the initial cost of the structure has been recorded for the two cases of LCC-based optimal design and Traditional design. As mentioned in

Section 4, the initial cost of the structural components includes the cost of reinforcement, concrete and formwork, which is shown in

Table 3. The breakdown for structural components including beams and columns has been specified. Due to the reduction of column sections and the increase of beam sections in the optimal design, the initial costs related to columns for reinforcement, concrete and formwork are reduced by 4, 9 and 2 percent, respectively, whereas for beams there is an increase by 10, 2 and 2 percent, respectively. In total, LCC based optimal design will cause a cost increase by 1% compared to Traditional design.

The comparison of the life cycle costs of the structure can be seen in

Table 4. The important point is the positive effect of LCC based optimal design in reducing life cycle costs compared to traditional design. The greatest impact on reducing the costs of the life cycle of the structure is on

with 22%, followed by

,

and

with 20, 16 and 16%, respectively. The comparison of the total initial costs and the life cycle costs of the structure for LCC based optimal design and traditional design in

Table 5 shows that with only 1 percent increase in the initial costs for the structure, the life cycle costs of the structure can be reduced by 13 percent and with a reduced total life cycle costs of 10 percent. Thus, the cost of the entire life cycle of the structure shows a decrease from 5.22E+05 dollars to 4.71E+05 dollars.

5.4. Multi-Objective Optimization

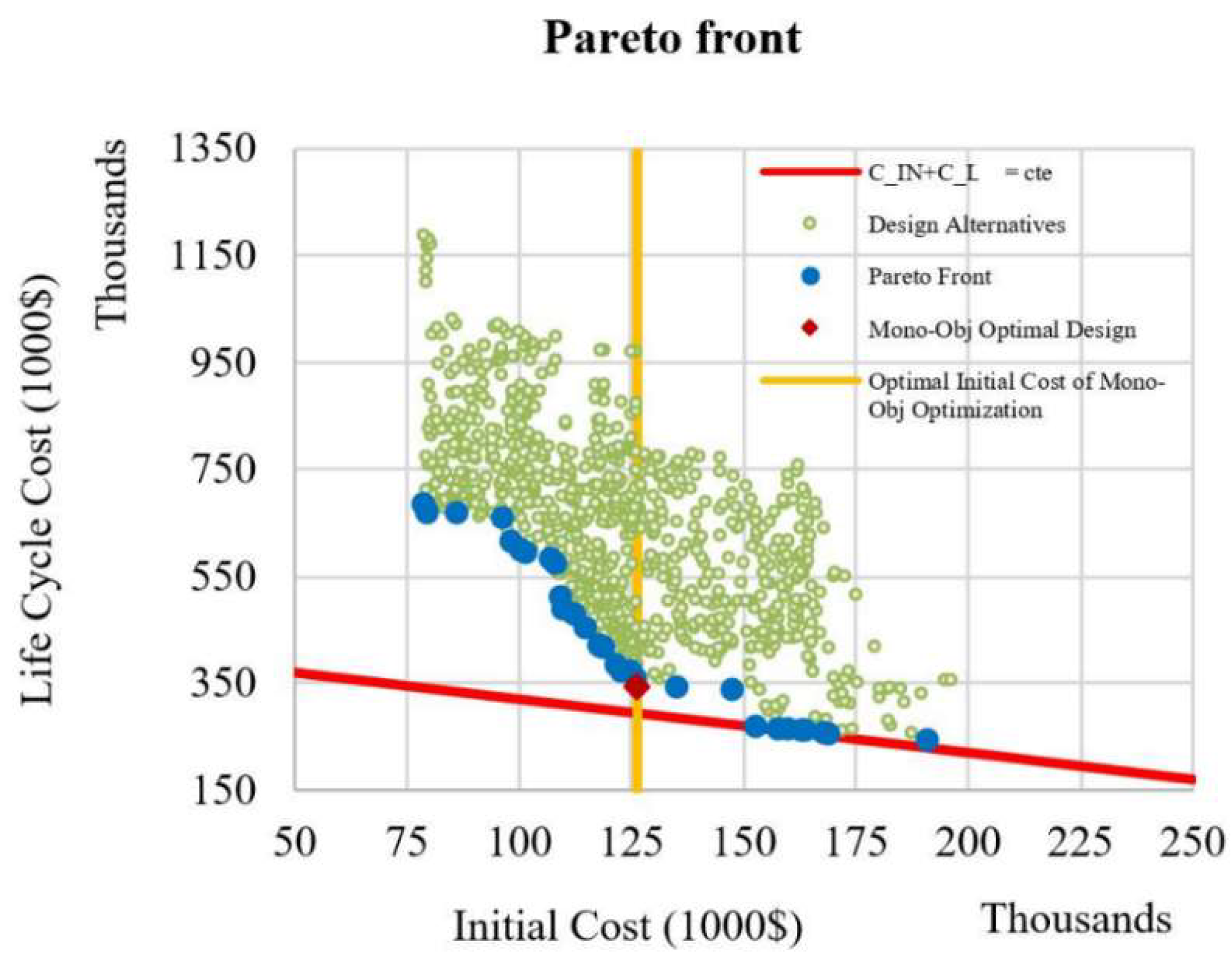

The initial or total cost of a structure alone may not prepare comprehensive data on the structure's performance in a real-life design problem. Many contradictory and often inconsistent requirements should be considered concurrently to arrive at a rational design in practical decision-making issues. As a result, a consistent decision-making process necessitates detailed knowledge about design options from which a designer chooses the one that best balances conflicting goals. This knowledge can be better demonstrated in a Pareto front of design alternatives with optimized initial costs and life-cycle costs concurrently. The two most critical metrics for decision-making are generally the initial construction cost and the expected cost over the structure's lifetime Multi-objective optimization procedures can solve the optimization problem and achieve specific Pareto optimal designs. The multi-objective algorithm generates a collection of optimal designs for a wide range of alternatives. The key feature of the Pareto optimal set is that no change in one objective is possible without deterioration in other objectives.

The structure's initial cost and lifetime cost are the two different objectives in this multi-objective optimization problem. The discrete optimization problem is solved using the multi-objective ideal gas molecular movement (MOIGMM) algorithm. The algorithm's ability to solve multi-objective optimization problems in a computationally capable manner has been demonstrated by its use in engineering problems [

36]. The initial cost

and the expected lifetime cost

of the structure are the first and second objectives, respectively, and thus, the optimization problem can be set as:

where s is the design vector, F is the feasible design space, and k is the number of constraint functions. There are totally 72 design variables for the problem, including 12 for the column sections, 4 for the beam heights, and 56 for the relative section areas of the beam's upper steel bars, one independent variable for each end of a beam.

denotes the constraints that candidate design alternatives should meet. One of the constraints is that the selected sections for columns in each story cannot be weaker than those in the upper story. In addition, all code-based limitations imposed by ACI318-14 design recommendations must be met. Moreover, this means that according to prescriptive design requirements, all Pareto optimal designs would be acceptable. Inter-story drift ratio limits are also set at both operation and ultimate levels. These are controlled using a linear elastic analysis by OpenSees software [

61]. Once the expressed constraints have been met, a nonlinear time-history analysis using the ET method is carried out. The expected lifetime cost due to future seismic hazards is measured using life-cycle cost assessment.

Now, each design variable’s variations interval is increased according to

Table 7, and the MOIGMM algorithm is allowed to search a broader range to eventually yield a complete Pareto Front. After 25 cycles, with an initial population of 20, archive size of 25 and number of sub-cubes equal to 30, this algorithm performed the Pareto Front shown in

Figure 6.

It is worth noting that each design on a Pareto Front that meets a vertical line with a specified distance from the origin (initial cost) is the one with the best performance possible to be built with its initial cost. For instance,

Figure 6 shows the optimum design based on a mono-objective optimization and its related initial cost. It reveals that this design has the lowest total cost among those with similar initial costs. As expected, an increase in the range of variations of the design variables will yield points with lower total costs than the solution found in the mono-objective optimization. Besides, this figure can be studied as a guide for decision-making to see the reduction trend of the lifetime cost with an increase in the initial cost. This information can assist the decision-makers to choose a design that can create a relative balance between two objective functions. It also shows that in design alternatives with an initial cost of about 147000

$, a slight increase in the initial investment can considerably enhance the structure performance and reduce the future costs. It is worth mentioning that the problem space is discrete because the design variables are discrete, and this has created some discontinuities in the obtained Pareto Front. It is possible to consider the sum of the initial and lifetime costs as a criterion for choosing a point from among different Pareto Front points. This criterion is shown in

Figure 6 by drawing the line

. Points lying on this line are responses that will have the minimum total life-cycle cost.